Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

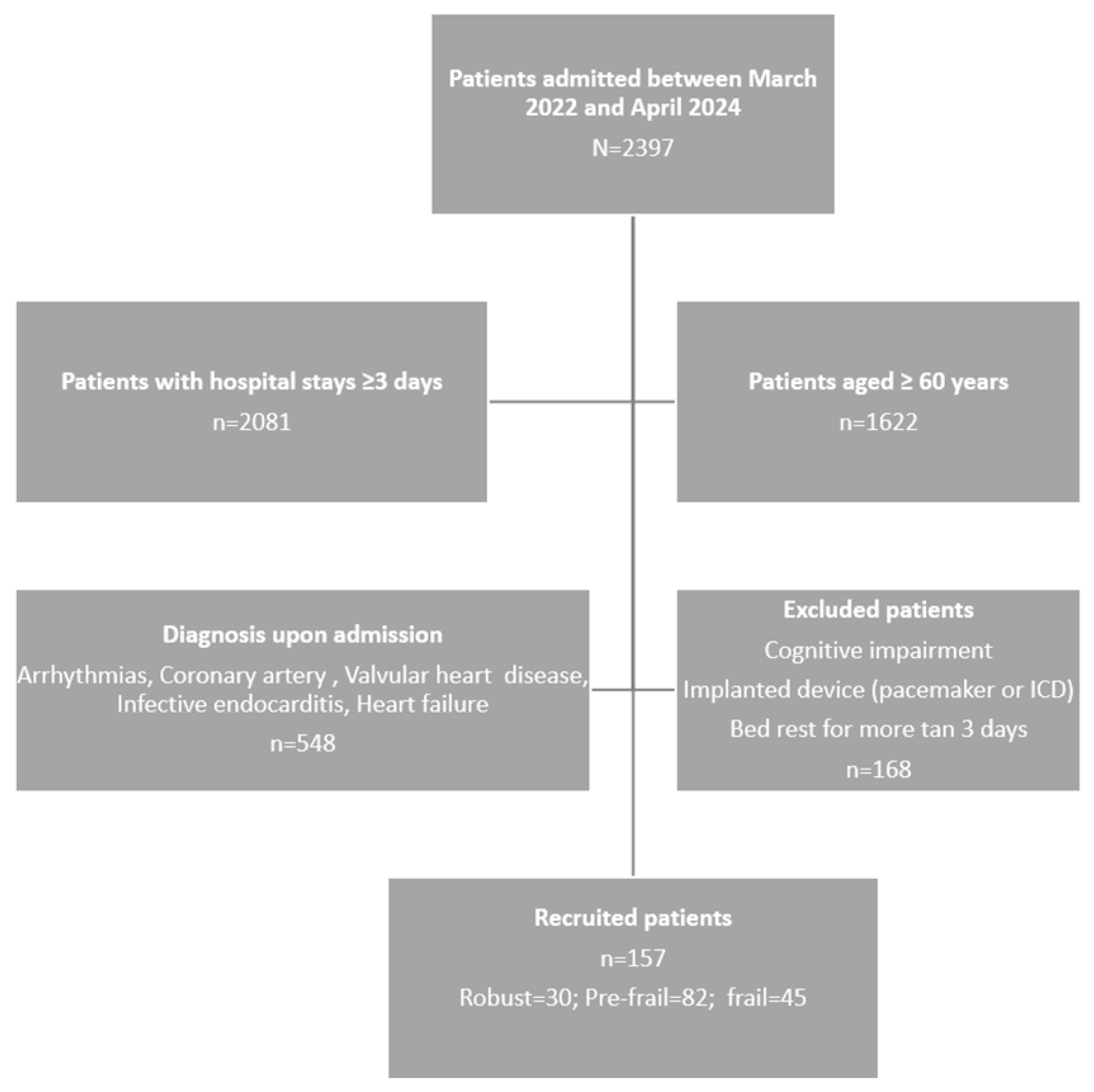

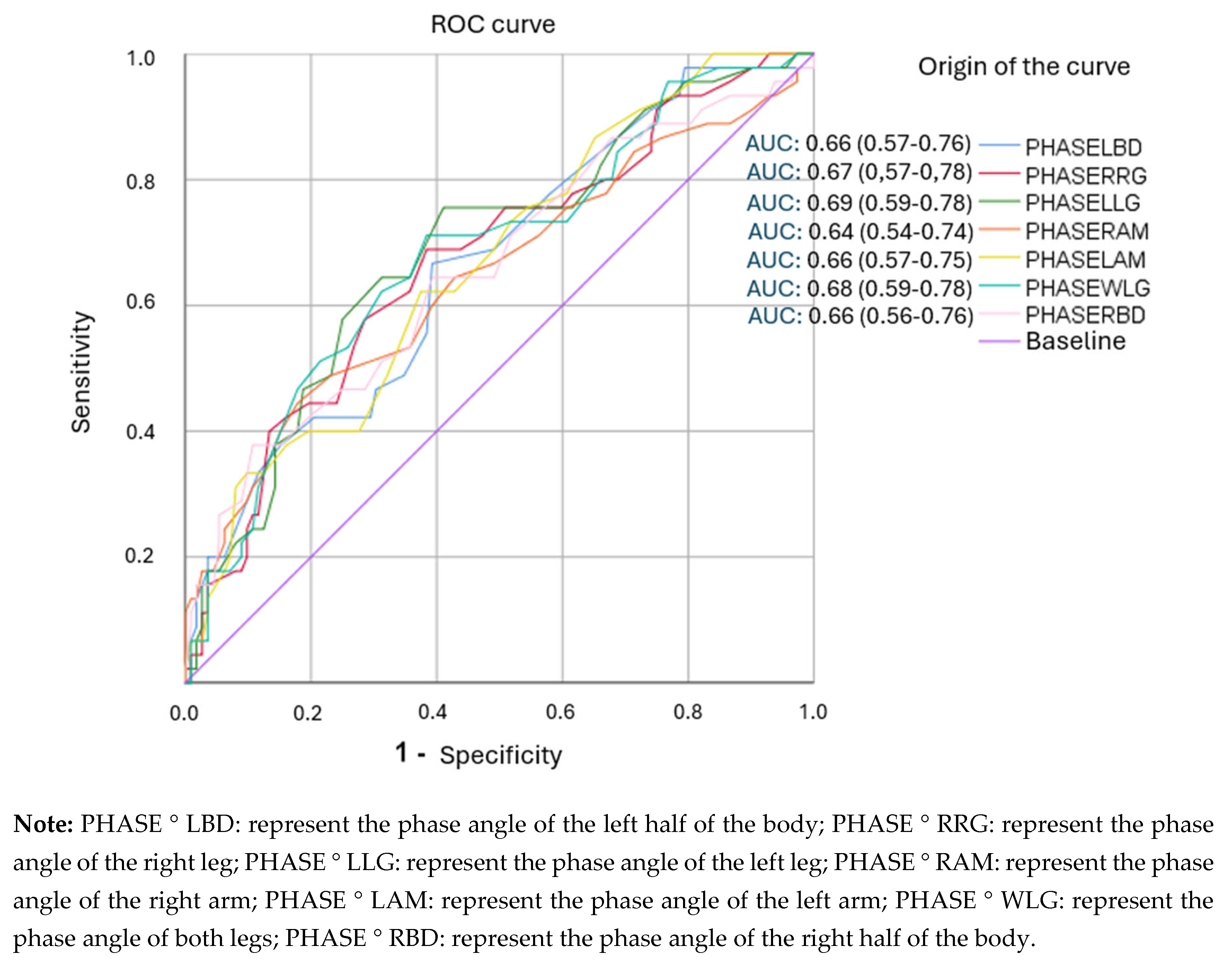

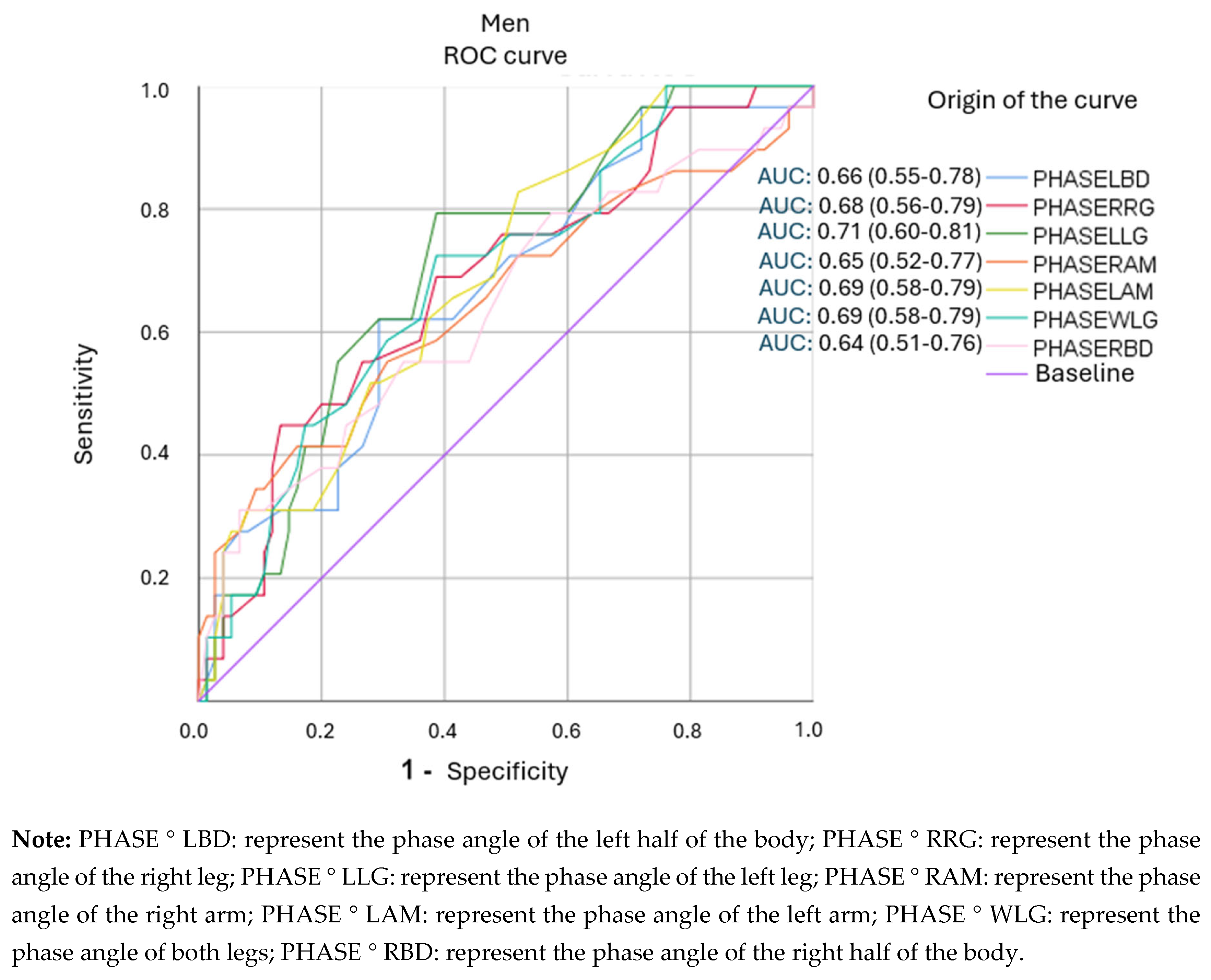

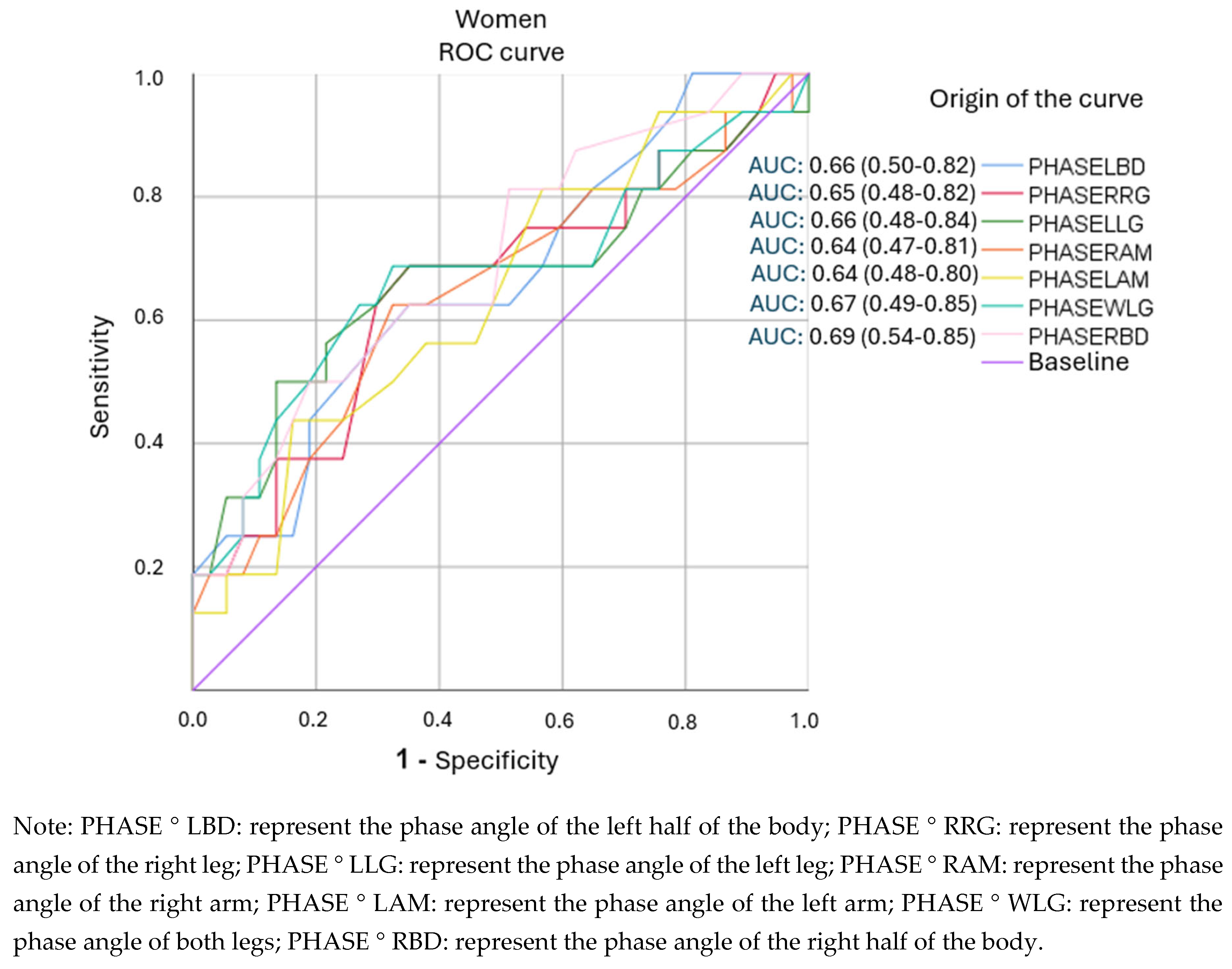

Background/Objectives: Whole-body phase angle has been associated with in-hospital morbidity and mortality, although cut-off points vary. Studies on the relationship between segmental phase angles and frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease are limited. Therefore, we aimed to assess the prognostic value of segmental phase angles in detecting frailty in older adults hospitalized with cardiovascular disease. Methods: A cross-sectional observational study was conducted on hospitalized patients aged ≥60 years with cardiovascular disease. Frailty was identified using Fried's five criteria. Biomarkers (CRP, albumin, hemoglobin), anthropometric parameters, and body composition using segmental electrical bioimpedance (phase angles, body fat, body water, and sarcopenia index) were collected. Associations with frailty were analyzed using logistic regression and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive likelihood ratio (LR+) were calculated (95% CI; p<0.05). Results: A total of 157 patients (men: 64.24%; women: 33.76%) were included, with a mean age of 73.23 years (SD=7.91). The prevalence of frailty was 28.66%. In men, the phase angles of the left hemisphere (5.15°) and left leg (4.25°) showed good discriminatory capacity (AUC: 0.66–0.71; LR+: >2). In women, the segments with significance did not exceed an LR+ of 2. Frailty was associated with lower phase angle values in all segments and with biomarkers such as hemoglobin <12 g/dL (p=0.011) and CRP >5 mg/L (p=0.030). Conclusions: Segmental phase angles are moderately useful for identifying frailty in hospitalized older men with cardiovascular disease. Further studies are needed to establish clinically useful cutoffs, especially in women.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Body Composition, Frailty and CVD

1.2. Phase Angle as a Prognostic Value

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Population and Sample

2.1.1. Sample Size

2.2. Variables and Measurements

2.2.1. Blood Biomarkers

2.2.2. Frailty

- Unintentional weight loss of more than 4.5 kg or more than 5.0% in less than one year.

- Feeling of general exhaustion (low energy and resistance according to the CES-D depression scale) [33].

- Weakness (measured using a Digital Hand Dynamometer).

- Slow walking speed (time to cover 4.57m adjusted for gender and height).

- Weekly physical activity level (Determined using the Minnesota Leisure Time Activity Questionnaire (MLTAQ) stratified by gender; men: 383 kcal/week and women: 270 kcal/week) [34].

- Frail patients: Three or more of the above criteria were met.

- Patients with pre-frailty: they met one or two of the above criteria.

- Patients without frailty: They did not present any of the previous criteria.

2.2.3. Cardiovascular Risk

2.2.4. Body Composition and Phase Angles

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Participants

| Variable | Total (n = 157) |

Men (n = 104) |

Women (n = 53) |

Frail (n = 45) |

Pre-frail (n = 82) |

Non-frail (n = 30) |

p-value (frailty) | p-value (sex) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 73.23 (7.91) | 73.42 (7.84) | 72.92 (8.10) | 77.98 (7.98) | 71.32 (7.29) | 71.47 (6.54) | <0.001 | 0.691 |

| Fragility (%) | 28.66 | 27.88 | 30.19 | — | — | — | — | 0.741 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 61.15 | 62.50 | 58.49 | — | — | — | — | 0.651 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 35.03 | 37.50 | 30.19 | — | — | — | — | 0.355 |

| Cardiovascular risk ≥20% (%) | 19.75 | 25.00 | 9.43 | 8.00 | 16.00 | 7.00 | 0.256 | 0.021 |

| Hospital stays (days), mean (SD) | 8.72 (5.44) | 9.43 (5.99) | 7.30 (3.82) | 11.35 (6.82) | 7.81 (4.30) | 7.30 (4.82) | <0.01 | 0.043 |

| BMI >27 kg/m2 (%) | 56.05 | 58.65 | 50.94 | 60.00 | 56.10 | 50.00 | 0.568 | 0.341 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 160.59 (44.19) | 150.89 (43.21) | 179.62 (40.03) | 156.53 (45.70) | 162.76 (44.34) | 160.77 (42.48) | 0.608 | <0.001 |

| HDL (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 45.34 (13.69) | 42.53 (11.75) | 50.85 (15.57) | 42.40 (9.78) | 46.49 (15.66) | 46.60 (12.64) | 0.224 | <0.001 |

| LDL (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 91.59 (36.51) | 85.73 (36.76) | 103.08 (33.46) | 91.40 (36.85) | 91.94 (36.72) | 90.90 (36.67) | 0.964 | <0.01 |

| Hb <12 g/dL (%) | 16.56 | 16.65 | 16.98 | 28.89 | 10.98 | 13.33 | 0.032 | 0.968 |

| Albumin <3.2 g/dL (%) | 8.92 | 11.54 | 3.77 | 13.33 | 7.32 | 6.67 | 0.231 | 0.112 |

| PCR >5 mg/L (%) | 48.41 | 49.04 | 47.17 | 62.22 | 43.90 | 40.00 | 0.060 | 0.833 |

3.2. Body Composition and Frailty

3.3. Relationship Between Segmental Phase Angles and Frailty Status

| Frailty status (Fried) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segmental phase angles | Frail (a) |

Non-frail (b) |

Pre-frail (c) |

Frail (a) |

Non-frail (b) |

Pre-frail (c) |

||

|

(SD) |

(SD) p-value |

(SD) p-value |

(SD) p-value |

Sex |

(SD) p-value |

(SD) p-value |

(SD) p-value |

|

| PHASE°LBD | 5.15 (0.87) |

4.82 (0.98) c (0.009) |

5.23 (0.74) |

5.30 (0.80) |

Male |

5.00 (1.06) c (0.045) |

5.34 (0.76) |

5.51 (0.82) |

| Female | 4.49 (0.75) |

4.80 (0.43) |

4.95 (0.65) |

|||||

| PHASE°RRG | 4.58 (1.09) |

4.13 (1.05) c (0.002) |

4.65 (0.76) |

4.81 (1.14) |

Male |

4.09 (1.08) c (0.018) |

4.73 (0.77) |

4.82 (1.25) |

| Female | 4.20 (1.03) |

4.32 (0.65) |

4.79 (0.96) |

|||||

| PHASE°LLG | 4.53 (1.04) |

4.05 (1.00) c (0.000) |

4.56 (0.84) |

4.78 (1.06) |

Male |

4.03 (0.90) c (0.004) |

4.64 (0.88) |

4.83 (1.15) |

| Female | 4.09 (1.18) |

4.23 (0.58) |

4.69 (0.91) |

|||||

| PHASE°RAM | 5.71 (0.84) |

5.46 (1,12) c (0.044) |

5.77 (0.59) |

5.84 (0.72) |

Male |

5.63 (1.25) c (0.004) |

5.80 (0.61) |

6.07 (0.65) |

| Female | 5.14 (0.77) |

5.62 (0.50) |

5.46 (0.66) |

|||||

| PHASE°LAM | 5.57 (0.82) |

5.21 (0.76) b (0.011) c (0.003) |

5.76 (0.80) |

5.70 (0.81) |

Male | 5.38 (0.75) |

5.87 (0.82) |

5.98 (0.80) |

| Female | 4.91 (0.69) |

5.32 (0.53) |

5.23 (0.59) |

|||||

| PHASE°WLG | 4.65 (1.03) |

4.20 (1.00) c (0.001) |

4.77 (0.76) |

4.89 (1.07) |

Male |

4.17 (0.96) c (0.008) |

4.74 (0.79) |

4.91 (1.16) |

| Female | 4.24 (1,11) |

4.37 (0.60) |

4.85 (0.91) |

|||||

| PHASE°RBD | 5.22 (0.94) |

4.96 (1.27) |

5.29 (0.63) |

5.34 (0.78) |

Male | 5.17 (1.46) |

5.37 (0.66) |

5.49 (0.81) |

| Female |

4.56 (0.71) c (0.045) |

4.98 (0.44) |

5.08 (0.67) |

|||||

3.4. Relationship of Segmental Phase Angles and Cachexia Biomarkers with Frailty Status

3.4. Analysis of ROC Curves and Cut-Off Points for Segmental Phase Angles.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Abbreviations

| ASM | Appendicular skeletal mass |

| BIA | Bioelectrical impedance |

| BMI | Body muscular index |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DXA | Bone densitometry |

| EWGSOP2 | European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (2nd definition) |

| IWGS | International Working Group on Sarcopenia |

| NT-ProBNP | N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide |

| PhA | Phase angle |

| PHASE ° LBD | Phase angle of the left half of the body |

| PHASE ° RRG | Phase angle of the right leg |

| PHASE ° LLG | Phase angle of the left leg |

| PHASE ° RAM | Phase angle of the right arm |

| PHASE ° LAM | Phase angle of the left arm |

| PHASE ° WLG | Phase angle of both legs |

| PHASE ° RBD | Phase angle of the right half of the body |

References

- Cederholm, T.; Barazzoni, R.; Austin, P.; Ballmer, P.; Biolo, G.; Bischoff, S.C.; Compher, C.; Correia, I.; Higashiguchi, T.; Holst, M.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2017, 36, 49-64. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.N.; Stauber, P.M.; Koehler, K.M.; Romero, L.; Garry, P.J. Associations of fat and muscle masses with bone mineral in elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996, 63, 365-72. [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.L.; Wannamathee, S.G. Sarcopenic obesity in ageing: cardiovascular outcomes and mortality. Br J Nutr. 2020, 124, 1102-1113. [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022, 29, 5-115. [CrossRef]

- Ni Lochlainn, M.; Cox, N.J.; Wilson, T.; Hayhoe, R.P.G.; Ramsay, S.E.; Granic, A.; Isanejad, M.; Roberts, H.C.; Wilson, D.; Welch, C.; et al. Nutrition and Frailty: Opportunities for Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2349. [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Cohen, A.A.; Xue, Q.L.; Walston, J.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Varadhan, R. The physical frailty syndrome as a transition from homeostatic symphony to cacophony. Nat Aging. 2021, 1,36-46. Epub 2021 Jan 14. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.J.; Racette, S.B. The Utility of Body Composition Assessment in Nutrition and Clinical Practice: An Overview of Current Methodology. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2493. [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.C. Electrical Bioimpedance: From the Past to the Future. J Electr Bioimpedance. 2021, 12, 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Iglesias, A.; Fernández-Lucas, M.; Teruel, J.L. The electrical basis of bioimpedance. Nefrologia 2012, 32, 133-5. English, Spanish. [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001, 56, M146-56. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, A. Application of the Clinical Frailty Score and body composition and upper arm strength in haemodialysis patients. Clin Kidney J. 2021, 15, 553-559. [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.O.; Park, S.Y.; Choi, B.G.; Na, J.O.; Choi, C.U.; Kim, E.J.; Rha, S.W.; Park, C.G.; Hong, S.J.; Seo, H.S. Prognostic Impact of Low Skeletal Muscle Mass on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Coronary Artery Disease: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis of a Single Center All-Comer Cohort. J Clin Med. 2019, 8, 712. [CrossRef]

- von Haehling, S.; Garfias Macedo, T.; Valentova, M.; Anker, M.S.; Ebner, N.; Bekfani, T.; Haarmann, H.; Schefold, J.C.; Lainscak, M.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Doehner, W.; et al. Muscle wasting as an independent predictor of survival in patients with chronic heart failure. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020, 11, 1242-1249. Epub 2020 Aug 6. [CrossRef]

- Korzonek-Szlacheta, I.; Hudzik, B.; Zubelewicz-Szkodzińska, B.; Czuba, Z.P.; Szlacheta, P.; Tomasik, A. The Association between Circulating Cytokines and Body Composition in Frail Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1227. [CrossRef]

- Nishio, R.; Dohi, T.; Fukase, T.; Takeuchi, M.; Takahashi, N.; Endo, H.; Doi, S.; Okai, I.; Iwata, H.; Okazaki, S.; et al. Impact of simple equation for estimating appendicular skeletal muscle mass in patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2022, 44, 101163. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Y. Association between bone mineral density and cardiovascular disease in older adults. Front Public Health. 2023, 11, 1103403. [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.J.; Cho, J.; Choi, S.M.; Park, Y.S.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, S.M.; Yoo, C.G.; Kim, Y.W.; Lee, J. Phase Angle and Frailty Are Important Prognostic Factors in Critically Ill Medical Patients: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021, 25, 218-223. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Ando, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Seki, T.; Hamada, T.; Machino, M.; Ota, K.; Morozumi, M.; Kanbara, S.; Ito, S.; et al. Low Bioelectrical Impedance Phase Angle Is a Significant Risk Factor for Frailty. Biomed Res Int. 2019, 2019:6283153. [CrossRef]

- Zanforlini, B.M.; Trevisan, C.; Bertocco, A.; Piovesan, F.; Dianin, M.; Mazzochin, M.; Alessi, A.; Zoccarato, F.; Manzato, E.; Sergi, G. Phase angle and metabolic equivalents as predictors of frailty transitions in advanced age. Exp Gerontol. 2019, 122, 47-52. [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Herpich, C.; Müller-Werdan, U. Role of phase angle in older adults with focus on the geriatric syndromes sarcopenia and frailty. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2023, 24, 429-437. Epub 2022 Dec 2. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, R.; Dalla-Rovere, L.; García-Olivares, M.; Abuín-Fernández, J.; Sánchez-Torralvo, F.J.; Doulatram-Gamgaram, V.K.; Hernández-Sanchez, A.M.; García-Almeida, J.M. Phase Angle and Handgrip Strength as a Predictor of Disease-Related Malnutrition in Admitted Patients: 12-Month Mortality. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1851. [CrossRef]

- Stellingwerf, F.; Beumeler, L.F.E.; Rijnhart-de Jong, H.; Boerma, E.C.; Buter, H. The predictive value of phase angle on long-term outcome after ICU admission. Clin Nutr. 2022, 41, 1256-1259. Epub 2022 Apr 6. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ling, S.; Liu, Z.; Luo, D.; Qi, A.; Zeng, Y. The ability of phase angle and body composition to predict risk of death in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2024, 56, 731-737. Epub 2023 Aug 5. [CrossRef]

- de Borba, E.L.; Ceolin, J.; Ziegelmann, P.K.; Bodanese, L.C.; Gonçalves, M.R.; Cañon-Montañez, W.; Mattiello, R. Phase angle of bioimpedance at 50 kHz is associated with cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022, 76, 1366-137. Epub 2022 Apr 12. [CrossRef]

- Langer, R.D.; Larsen, S.C.; Ward, L.C.; Heitmann, B.L. Phase angle measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis and the risk of cardiovascular disease among adult Danes. Nutrition 2021, 89, 111280. Epub 2021 Apr 18. [CrossRef]

- Scicchitano, P.; Ciccone, M.M.; Iacoviello, M.; Guida, P.; De Palo, M.; Potenza, A.; Basile, M.; Sasanelli, P.; Trotta, F.; Sanasi, M; et al. Respiratory failure and bioelectrical phase angle are independent predictors for long-term survival in acute heart failure. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2022, 56, 28-34. [CrossRef]

- Mullie, L.; Obrand, A.; Bendayan, M.; Trnkus, A.; Ouimet, M.C.; Moss, E.; Chen-Tournoux, A.; Rudski, L.G.; Afilalo, J. Phase Angle as a Biomarker for Frailty and Postoperative Mortality: The BICS Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008721. [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.C. Editorial Comment: Phase angle from bioimpedance measurements as a surrogate of cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022, 76, 1364-1365. Epub 2022 Jul 8. [CrossRef]

- Richter, D.; Guasti, L.; Walker, D.; Lambrinou, E.; Lionis, C.; Abreu, A.; Savelieva, I.; Fumagalli, S.; Bo, M.; Rocca, B.; et al. Frailty in cardiology: definition, assessment and clinical implications for general cardiology. A consensus document of the Council for Cardiology Practice (CCP), Association for Acute Cardio Vascular Care (ACVC), Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP), European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Council on Valvular Heart Diseases (VHD), Council on Hypertension (CHT), Council of Cardio-Oncology (CCO), Working Group (WG) Aorta and Peripheral Vascular Diseases, WG e-Cardiology, WG Thrombosis, of the European Society of Cardiology, European Primary Care Cardiology Society (EPCCS). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022, 29, 216-227. [CrossRef]

- James, K.; Jamil, Y.; Kumar, M.; Kwak, M.J.; Nanna, M.G.; Qazi, S.; Troy, A.L.; Butt, J.H.; Damluji, A.A.; Forman, D.E.; et al. Frailty and Cardiovascular Health. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e031736. Epub 2024 Jul 26. [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, M.; de Groot, J.A.; Moons, K.G.; Collins, G.S.; Altman, D.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Reitsma, J.B. No rationale for 1 variable per 10 events criterion for binary logistic regression analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016, 16,163. [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 867-72. [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. TheCES-DScale:ASelf-ReportDepressionScaleforResearchintheGeneralPopulation. Appl Psychol Meas 1977, 1, 385–401.

- Ruiz Comellas, A.; Pera, G.; Baena Diez, J.M.; et al. [Validation of a Spanish Short Version of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (VREM)]. Rev Esp Public Health 2012, 86, 495–508.

- Wilson, P.W.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Levy, D.; Belanger, A.M.; Silbershatz, H.; Kannel, W.B. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998, 97, 1837-47. [CrossRef]

- Meeuwsen, S.; Horgan, G.W.; Elia, M. The relationship between BMI and percent body fat, measured by bioelectrical impedance, in a large adult sample is curvilinear and influenced by age and sex. Clin Nutr. 2010, 29,560-6. Epub 2010 Mar 31. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 601. Erratum for: Age Ageing. 2019, 48, 16-31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169. [CrossRef]

- Fielding, R.A.; Vellas, B.; Evans, W.J.; Bhasin, S.; Morley, J.E.; Newman, A.B.; Abellan van Kan, G.; Andrieu, S.; Bauer, J.; Breuille, D.; et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011, 12, 249-56. Epub 2011 Mar 4. [CrossRef]

- Benz, E.; Pinel, A.; Guillet, C.; Capel, F.; Pereira, B.; De Antonio, M.; Pouget, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Eglseer, D.; Topinkova, E.; et al. Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity and Mortality Among Older People. JAMA Netw Open. 2024, 7,e243604. [CrossRef]

- Fagan, T.J. Letter: Nomogram for Bayes’s theorem. N Engl J Med. 1975, 293, 257. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ros, P.; Vila-Candel, R.; López-Hernández, L.; Martínez-Arnau, F.M. Nutritional Status and Risk Factors for Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older People: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12,1041. [CrossRef]

- Elguezabal-Rodelo, R.; Ochoa-Précoma, R.; Vazquez-Marroquin, G.; Porchia, L.M.; Montes-Arana, I.; Torres-Rasgado, E.; Méndez-Fernández, E.; Pérez-Fuentes, R.; Gonzalez-Mejia, M.E. Metabolic age correlates better than chronological age with waist-to-height ratio, a cardiovascular risk index. Med Clin (Barc). 2021, 157, 409-417. English, Spanish. Epub 2020 Oct 13. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm-Leen, E.R.; Hall, Y.N.; Horwitz, R.I.; Chertow, G.M. Phase angle, frailty and mortality in older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2014, 29, 147-54. [CrossRef]

- Crow, R.S.; Lohman, M.C.; Titus, A.J.; Cook, S.B.; Bruce, M.L.; Mackenzie, T.A.; Bartels, S.J.; Batsis, J.A. Association of Obesity and Frailty in Older Adults: NHANES 1999-2004. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019, 23, 138-144. [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou, P; Chaloulakou, S.; Karayiannis D.; Almperti A.; Poupouzas, G.; Vrettou, C.S.; Issaris, V.; Jahaj, E.; Vassiliou, A.G., Dimopoulou, I. Phase Angle Trajectory Among Critical Care Patients: Longitudinal Decline Predicts Mortality Independent of Clinical Severity Scores. Healthcare (Basel). 2025, 13(12):1463. [CrossRef]

- Ryz, S.; Nixdorf, L.; Puchinger, J.; Lassnigg, A.; Wiedemann, D.; Bernardi, M.H. Preoperative Phase Angle as a Risk Indicator in Cardiac Surgery-A Prospective Observational Study. Nutrients. 2022, 14(12):2491. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n = 157) |

Male (n = 104) |

Female (n = 53) |

Frail (n = 45) |

Pre-frail (n = 82) |

Non-frail (n = 30) |

p-value (frailty) | p-value (sex) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic age (years), mean (SD) |

63.76 (11.14) | 62.91 (11.59) | 65.45 (10.16) | 69.42 (9.44) | 62.15 (10.56) | 59.66 (8.96) | 0.001 | 0.102 |

| % Body fat, mean (SD) | 27.20 (7.66) | 25.72 (6.63) | 30.28 (8.73) | 29.81 (6.98) | 26.89 (8.01) | 25.27 (6.93) | 0.068 | <0.01 |

| Abdominal perimeter (cm), mean (SD) | 102.64 (13.33) | 104.83 (13.27) | 98.49 (12.36) | 106.52 (12.91) | 103.12 (13.31) | 96.90 (11.12) | 0.027 | 0.003 |

| % Total Body Water, mean (SD) |

51.78 (5.79) | 52.84 (5.43) | 49.67 (5.96) | 49.74 (6.21) | 52.12 (5.38) | 53.04 (5.36) | 0.062 | <0.01 |

| Fat-free mass (kg), mean (SD) |

54.04 (11.40) | 59.80 (8.74) | 42.17 (7.19) | 50.94 (10.73) | 54.46 (11.35) | 57.13 (10.63) | 0.075 | <0.001 |

| Muscle mass (kg), mean (SD) |

51.32 (10.86) | 56.79 (8.32) | 39.75 (6.79) | 48.25 (10.12) | 51.79 (10.89) | 54.56 (10.02) | 0.082 | <0.001 |

| ASM/height2 (kg/m2), mean (SD) |

8.17 (1.23) | 8.61 (1.09) | 7.33 (1.00) | 8.31 (1.17) | 8.10 (1.27) | 8.17 (1.18) | 0.404 | <0.001 |

| % ASM/body weight, mean (SD) |

17.13 (2.80) | 17.56 (2.41) | 16.24 (3.36) | 16.85 (2.75) | 17.13 (2.87) | 17.66 (2.64) | 0.339 | <0.05 |

| % Right arm fat, mean (SD) | 31.42 (7.84) | 29.84 (6.90) | 34.63 (8.45) | 33.91 (7.45) | 31.03 (7.96) | 29.63 (7.31) | 0.018 | <0.01 |

| Grip strength (kg), mean (SD) |

25.34 (9.72) | 29.04 (8.45) | 17.70 (6.20) | 20.05 (8.09) | 26.25 (9.70) | 31.53 (7.59) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sarcopenic obesity (%) | 4.46 | 6.63 | 0.00 | 8.89 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 0.047 | 0.041 |

| Phase angle | Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmias n=16 (a) |

Infective endocarditis n=2 (b) |

Heart failure n=34 (c) |

Coronary artery disease n=96 (d) |

Valvopathies n=9 (e) |

|

|

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

(SD) |

|

| PHASE°LBD |

5.13 b (0.82) |

7.10 (2.55) |

4.81 b,d (0.83) |

5.32 b (0.73) |

4.21 a,b,c,d (0.78) |

| PHASE°RRG |

4.30 d (1,10) |

4.00 (0.57) |

4.13 d (1.23) |

4.88 (0.97) |

3.78 d (0.60) |

| PHASE°LLG | 4.38 (1.19) |

4.00 (0.14) |

4.11 d (1.20) |

4.80 (0.90) |

3.62 d (0.65) |

| PHASE°RAM |

5.54 b (0.84) |

8.10 (2.97) |

5.34 b,d (0.69) |

5.88 b (0.71) |

5.17 b,d (0.91) |

| PHASE°LAM | -5.63 (0.98) |

6.25 (0.07) |

5.34 d (0.91) |

5.71 (0.71) |

4.74 a,b,c,d (0.80) |

| PHASE°WLG | 4.44 (1,10) |

4.30 (0.00) |

4.20 d (1.19) |

4.93 (0.90) |

3.76 d (0.62) |

| PHASE°RBD |

4.99 b (0.79) |

8.30 (4,10) |

4.82 b,d (0.81) |

5.40 b (0.73) |

4.49 b,d (0.77) |

| Standard error |

df | p-value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Superior | |||||

| PHASE ° LBD | 0.24 | 1 | 0.003 | 2.00 | 1.26 | 3.16 |

| PHASE ° RRG | 0.18 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.78 | 1.25 | 2.54 |

| PHASE ° LLG | 0.19 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.95 | 1.34 | 2.83 |

| PHASE ° RAM | 0.23 | 1 | 0.015 | 1.76 | 1.12 | 2.78 |

| PHASE ° LAM | 0.25 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.30 | 1.42 | 3.78 |

| PHASE ° WLG | 0.19 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.90 | 1.30 | 2.76 |

| PHASE ° RBD | 0.22 | 1 | 0.025 | 1.65 | 1.07 | 2.56 |

| CRP>5mg/L | 0.36 | 1 | 0.030 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.93 |

| Albumin<3.2 g/dL | 0.57 | 1 | 0.232 | 0.51 | 0.17 | 1.55 |

| Hemoglobin <12g/dL | 0.44 | 1 | 0.011 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.77 |

| Segmental phase angle (Cut-off point) ° |

Sensitivity | Specificity | LR+ (95%CI) | Post-test probability % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHASE°LBD (5.15) | 0.667 | 0.607 | 1.70 (1.25-2.31) | 41 (33-48) |

| PHASE°RRG (4.45) | 0.689 | 0.616 | 1.79 (1.32-2.44) | 42(35-50) |

| PHASE°LLG (4.25) | 0.644 | 0.688 | 2.06 (1.45-2.93) | 45(37-54) |

| PHASE°RAM (5.75) | 0.644 | 0.571 | 1.50(1.11-2.04) | 38(31-45) |

| PHASE°LAM (5.65) | 0.689 | 0.509 | 1.40 (1.07-1.84) | 36(30-43) |

| PHASE°WLG (4.45) | 0.694 | 0.536 | 1.39 (1.03-1.86) | 36(29-43) |

| PHASE°RBD (5.25) | 0.644 | 0.536 | 1.39(1.03-1.86) | 36(29-43) |

| Segmental phase angle (Cut-off point) ° Male |

Sensitivity | Specificity | LR + (95%CI) | Post-test probability % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHASE°LBD (5.15) | 0.621 | 0.707 | 2,12(1,35-3,33) | 45(34-56) |

| PHASE°RRG (4.45) | 0.690 | 0.573 | 1.62(1.13-2.31) | 39(30-47) |

| PHASE°LLG (4.45) | 0.793 | 0.613 | 2.05(1.46-2.88) | 44(36-53) |

| PHASE°RAM (5.95) | 0.655 | 0.533 | 1.40 (0.98-2.01) | 35(27-44) |

| PHASE°LAM (6.05) | 0.828 | 0.480 | 1.59(1.21-2.09) | 38(32-45) |

| PHASE°WLG (4.55) | 0.724 | 0.613 | 1.87 (1.30-2.69) | 42(33-51) |

| PHASE°RBD (5.65) | 0.793 | 0.427 | 1.38 (1.06-1.81) | 35(29-41) |

| Segmental phase angle (Cut-off point) ° Female |

Sensitivity | Specificity | LR + (95%CI) | Post-test probability % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHASE°LBD (4.65) | 0.625 | 0.649 | 1.78 (1.00-3.18) | 43(30-58) |

| PHASE°WLG (4.55) | 0.668 | 0.622 | 1.82 (1.07-3.08) | 44(32-57) |

| PHASE°RBD (5.15) | 0.812 | 0.486 | 1.58 (1.07-2.34) | 41(32-50) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).