Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

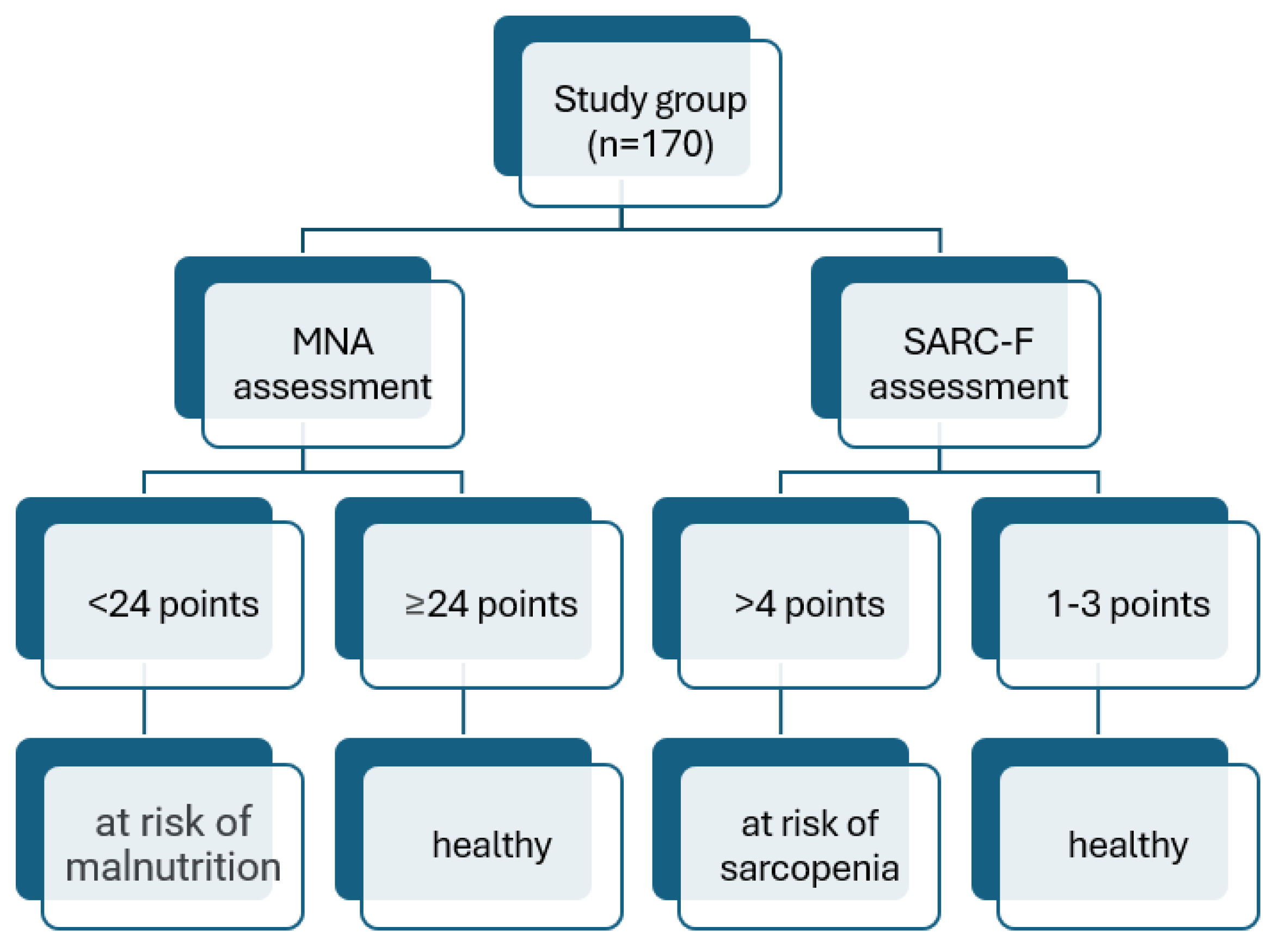

2. Materials and Methods

- Slowness—reduced gait speed at a distance of 5m at usual pace. The patient must repeat 3 times, and the results are averaged. If a patient walks for >6 seconds, the criterion is positive.

- Weakness is assessed with a maximal handgrip strength test. It is carried out in the dominant arm. We use the electronic hand dynamometer EH101 (VETEK AB, Sweden). A patient must repeat the test three times, and the maximal value is recorded. The test is positive for frailty when strength is lower than 20 kg for women and 30 kg for men.

- The Minnesota Leisure Time Activity questionnaire assesses low physical activity. The result is positive when calorie expenditure per week is lower than 270 kcal/week in women and <383 kcal/week in men. We have prepared a Microsoft Excel-based template for rapid questioning and easy calculation of all activities and respective calorie expenditure. We are assessing physical activity over the past 12 months.

- Exhaustion self-reported by a patient. It is evaluated by answering two questions from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R) scale. The patient must answer the following questions: “How often did you feel like everything you did was an effort in the past week? How often did you feel you could not get going in the past week?” The possible answers are often (≥3 days) or not, when the feeling is present in 0 to 2 days. A positive answer is when the patient says “often.”

- Weight loss exceeding 10 pounds (approximately 4.5 kg) unintentionally in the past year.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Medical Data

3.2. Potential Biomarkers Concentration

3.3. Components of Linda’s Fried Frailty Definition

3.4. Skale oceny Stanu Odżywienia, Ryzyka Sarkopenii i Stanu Funkcjonalnego Pacjentów

3.5. Stratification Analysis According to Frailty Stage, MNA, and SARC-F Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| MNA | Mini Nutritional Assessment |

| MNA-SF | Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form |

| FRAPICA | Frailty Syndrome in Daily Practice of Interventional Cardiology Ward |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| FFBM | Fat-free body mass |

| PEF | Peak expiratory flow |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory volume- one second |

| IADL | Instrumental Activites of Daily Living |

| CFS | Clinical Frailty Scale |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| PCI | Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| CABG | Coronary artery bypass grafting |

References

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogendijk, E.O.; Afilalo, J.; Ensrud, K.E.; Kowal, P.; Onder, G.; Fried, L.P. Frailty: Implications for Clinical Practice and Public Health. The Lancet 2019, 394, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Cohen, A.A.; Xue, Q.-L.; Walston, J.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Varadhan, R. The Physical Frailty Syndrome as a Transition from Homeostatic Symphony to Cacophony. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Chang, S.; Ho, H. Adverse Health Effects of Frailty: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Middle-Aged and Older Adults With Implications for Evidence-Based Practice. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2021, 18, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Calvani, R.; Marzetti, E.; Vetrano, D.L. Biomarkers Shared by Frailty and Sarcopenia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 73, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailliez, A.; Guilbaud, A.; Puisieux, F.; Dauchet, L.; Boulanger, É. Circulating Biomarkers Characterizing Physical Frailty: CRP, Hemoglobin, Albumin, 25OHD and Free Testosterone as Best Biomarkers. Results of a Meta-Analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 139, 111014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Collins, P.; Rattray, M. Identifying and Managing Malnutrition, Frailty and Sarcopenia in the Community: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gingrich, A.; Volkert, D.; Kiesswetter, E.; Thomanek, M.; Bach, S.; Sieber, C.C.; Zopf, Y. Prevalence and Overlap of Sarcopenia, Frailty, Cachexia and Malnutrition in Older Medical Inpatients. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faxén-Irving, G.; Luiking, Y.; Grönstedt, H.; Franzén, E.; Seiger, Å.; Vikström, S.; Wimo, A.; Boström, A.-M.; Cederholm, T. Do Malnutrition, Sarcopenia and Frailty Overlap in Nursing-Home Residents? J. Frailty Aging 2021, 10, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Xia, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Yin, S.; Yang, J.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, W.; Wang, S.; et al. Pathophysiological Mechanisms Underlying Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Biomarker Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasene, M.; Besga, A.; Medrano, M.; Urquiza, M.; Rodriguez-Larrad, A.; Tobalina, I.; Barroso, J.; Irazusta, J.; Labayen, I. Nutritional Status and Physical Performance Using Handgrip and SPPB Tests in Hospitalized Older Adults. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5547–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amasene, M.; Medrano, M.; Echeverria, I.; Urquiza, M.; Rodriguez-Larrad, A.; Diez, A.; Labayen, I.; Ariadna, B.-B. Malnutrition and Poor Physical Function Are Associated With Higher Comorbidity Index in Hospitalized Older Adults. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 920485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.M.; Kaiser, M.J.; Anthony, P.; Guigoz, Y.; Sieber, C.C. The Mini Nutritional Assessment®—Its History, Today’s Practice, and Future Perspectives. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2008, 23, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Morley, J.E. SARC-F: A Simple Questionnaire to Rapidly Diagnose Sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Ruan, L.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, L. Physical Frailty, Genetic Predisposition, and Incident Arrhythmias. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Huang, J.; Wan, J.; Zhong, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Tan, X.; Yu, B.; Lu, Y.; et al. Physical Frailty, Genetic Predisposition, and Incident Heart Failure. JACC Asia 2024, 4, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qayyum, S.; Rossington, J.A.; Chelliah, R.; John, J.; Davidson, B.J.; Oliver, R.M.; Ngaage, D.; Loubani, M.; Johnson, M.J.; Hoye, A. Prospective Cohort Study of Elderly Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: Impact of Frailty on Quality of Life and Outcome. Open Heart 2020, 7, e001314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołoszyn-Horák, E.; Salamon, R.; Chojnacka, K.; Brzosko, A.; Bieda, Ł.; Standera, J.; Płoszaj, K.; Stępień, E.; Nowalany-Kozielska, E.; Tomasik, A. Frailty Syndrome in Daily Practice of Interventional Cardiology Ward—Rationale and Design of the FRAPICA Trial: A STROBE-Compliant Prospective Observational Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e18935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetkin, N.A.; Akın, S.; Kocaslan, D.; Baran, B.; Rabahoglu, B.; Oymak, F.S.; Tutar, N.; Gulmez, İ. The Role of Diaphragmatic Ultrasound in Identifying Sarcopenia in COPD Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2025, Volume 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Adachi, H.; Enomoto, M.; Fukami, A.; Nakamura, S.; Nohara, Y.; Sakaue, A.; Morikawa, N.; Hamamura, H.; Toyomasu, K.; et al. Lower Albumin Levels Are Associated with Frailty Measures, Trace Elements, and an Inflammation Marker in a Cross-Sectional Study in Tanushimaru. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapuru, B.; Ershler, W.B. Inflammation, Coagulation, and the Pathway to Frailty. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Yang, J.; Fang, Y. Longitudinal Analysis on Inflammatory Markers and Frailty Progression: Based on the English Longitudinal Study of Aging. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024, 15, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilektasli, A.G.; Öztürk, N.A.A.; Kerimoğlu, D.; Odabaş, A.; Yaman, M.T.; Dogan, A.; Demirdogen, E.; Guclu, O.A.; Coşkun, F.; Ursavas, A.; et al. Slow Gait Speed Is Associated with Frailty, Activities of Daily Living and Nutritional Status in in-Patient Pulmonology Patients. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shang, N.; Gao, Q.; Guo, S.; Yang, T. Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Its Association with Frailty and Malnutrition among Older Patients with Sepsis-a Cross-Sectional Study in the Emergency Department. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lengelé, L.; Bruyère, O.; Beaudart, C.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Locquet, M. Malnutrition, Assessed by the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) Criteria but Not by the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), Predicts the Incidence of Sarcopenia over a 5-Year Period in the SarcoPhAge Cohort. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, C.; Nouvenne, A.; Cerundolo, N.; Meschi, T.; Ticinesi, A. ; on behalf of the Parma Post-Graduate Specialization School in Emergency-Urgency Medicine Interest Group on Thoracic Ultrasound Diaphragm Ultrasound in Different Clinical Scenarios: A Review with a Focus on Older Patients. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S.; Miyazaki, S.; Tamaki, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Arai, H.; Fujiwara, D.; Katsura, H.; Kawagoshi, A.; Kozu, R.; Maeda, K.; et al. Respiratory Sarcopenia: A Position Paper by Four Professional Organizations. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2023, 23, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Mao, H. The Relationship between Lung Function and Cognitive Impairment among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Depressive Symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 2025, 193, 112148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y. Association between Pulmonary Function and Rapid Kidney Function Decline: A Longitudinal Cohort Study from CHARLS. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2024, 11, e002107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Nyunt, M.-S.-Z.; Gao, Q.; Wee, S.-L.; Yap, K.-B.; Ng, T.-P. Association of Frailty and Malnutrition With Long-Term Functional and Mortality Outcomes Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Results From the Singapore Longitudinal Aging Study 1. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e180650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlaan, S.; Ligthart-Melis, G.C.; Wijers, S.L.J.; Cederholm, T.; Maier, A.B.; De Van Der Schueren, M.A.E. High Prevalence of Physical Frailty Among Community-Dwelling Malnourished Older Adults–A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atay, K.; Aydin, S.; Canbakan, B. Sarcopenia and Frailty in Cirrhotic Patients: Evaluation of Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Single-Centre Cohort Study. Medicina (Mex.) 2025, 61, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joaquín, C.; Alonso, N.; Lupón, J.; De Antonio, M.; Domingo, M.; Moliner, P.; Zamora, E.; Codina, P.; Ramos, A.; González, B.; et al. Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form Is a Morbi-Mortality Predictor in Outpatients with Heart Failure and Mid-Range Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3395–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moellmann, H.L.; Alhammadi, E.; Boulghoudan, S.; Kuhlmann, J.; Mevissen, A.; Olbrich, P.; Rahm, L.; Frohnhofen, H. Risk of Sarcopenia, Frailty and Malnutrition as Predictors of Postoperative Delirium in Surgery. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, P.; Ward, L.; Zazzetta, S.; Broggini, V.; Anzuini, A.; Valcarcel, B.; Brathwaite, J.S.; Pasinetti, G.M.; Bellelli, G.; Annoni, G. Association Between Preoperative Malnutrition and Postoperative Delirium After Hip Fracture Surgery in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, E.; Beckwée, D.; Delaere, A.; De Breucker, S.; Vandewoude, M.; Bautmans, I.; the Sarcopenia Guidelines Development Group of the Belgian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (BSGG); Bautmans, I.; Beaudart, C.; Beckwée, D.; et al. Nutritional Interventions to Improve Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength, and Physical Performance in Older People: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- the Sarcopenia Guidelines Development group of the Belgian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (BSGG); De Spiegeleer, A.; Beckwée, D.; Bautmans, I.; Petrovic, M. Pharmacological Interventions to Improve Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength and Physical Performance in Older People: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Drugs Aging 2018, 35, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıcı, H.; Tor, Y.B.; Altınkaynak, M.; Erten, N.; Saka, B.; Bayramlar, O.F.; Karakuş, Z.N.; Akpınar, T.S. Personalized Diet With or Without Physical Exercise Improves Nutritional Status, Muscle Strength, Physical Performance, and Quality of Life in Malnourished Older Adults: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Calvani, R.; Tosato, M.; Landi, F.; Picca, A.; Marzetti, E. Protein Intake and Physical Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 81, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Calvani, R.; Picca, A.; Tosato, M.; Landi, F.; Marzetti, E. Protein Intake and Frailty in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakabi, A.; Ishizaka, M.; Watanabe, M.; Matsumoto, C.; Ito, A.; Endo, Y.; Hara, T.; Igawa, T.; Kubo, A.; Itokazu, M. A Longitudinal Study of Frailty Reversibility through a Multi-Component Dementia Prevention Program.

- Faller, J.W.; Pereira, D.D.N.; De Souza, S.; Nampo, F.K.; Orlandi, F.D.S.; Matumoto, S. Instruments for the Detection of Frailty Syndrome in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0216166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| General n=170 | Robust n=53 | Prefrail n=96 | Frail n=21 | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 73,8 ± 5,6 | 72,8 ± 5,2 | 73,8 ± 5,5 | 76,3 ± 6,7 | NS |

| Men/women, n/n | 113/57 | 42/11 | 59/37 | 12/9 | NS |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 82,6 ± 13,4 | 82,8 ± 11,0 | 82,7 ± 14,6 | 81,8 ± 13,1 | NS |

| Height (cm), mean ± SD | 168,6 ± 7,9 | 170,6 ± 6,5 | 168,3 ± 8,0 | 165,3 ± 9,2 | <0,05 |

| BMI(kg/cm2), mean ± SD | 29,1 ± 4,7 | 28,5 ± 3,7 | 29,1 ± 4,6 | 30,5 ± 6,7 | NS |

| FFBM (kg), mean ± SD | 56,2 ± 9,2 | 57,3 ± 8,9 | 55,8 ± 9,7 | 55,1 ± 7,2 | NS |

| Diaphragm thickness (cm), mean ± SD | 3,7 ± 0,9 | 3,7 ± 0,8 | 3,7 ± 0,9 | 3,5 ± 0,93 | NS |

| PEF (L/min), mean ± SD |

316,3 ± 130,1 | 345,2 ± 135,7 | 311,9 ± 128,1 | 266,0 ± 117,0 | <0,05 |

| FEV1 (L), mean ± SD |

1,95 ± 0,7 | 2,1 ± 0,7 | 1,9 ± 0,7 | 1,5 ± 0,6 | <0,05 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 139 (82%) | 46 (87%) | 76 (79%) | 17 (81%) | NS |

| Hipercholesterolemia, n (%) | 126 (74%) | 41 (77%) | 75 (78%) | 10 (48%) | <0,05 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 74 (44%) | 21 (40%) | 44 (46%) | 9 (43%) | NS |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) |

40 (24%) | 8 (15%) | 24 (25%) | 8 (38%) | NS |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 15 (9%) | 4 (8%) | 7 (7%) | 4 (19%) | NS |

| COPD/asthma, n (%) | 25 (15%) | 7 (13%) | 16 (17%) | 2 (1%) | NS |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 19 (11%) | 10 (19%) | 7 (7%) | 2 (10%) | NS |

| History of MI, n (%) | 45 (27%) | 16 (30%) | 24 (25%) | 5 (24%) | NS |

| History of PCI, n (%) | 67 (39%) | 23 (43%) | 38 (40%) | 6 (29%) | NS |

| History of CABG, n (%) |

18 (11%) | 7 (13%) | 9 (9%) | 2 (10%) | NS |

| General n=170 | Robust n=53 | Prefrail n=96 | Frail n=21 | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

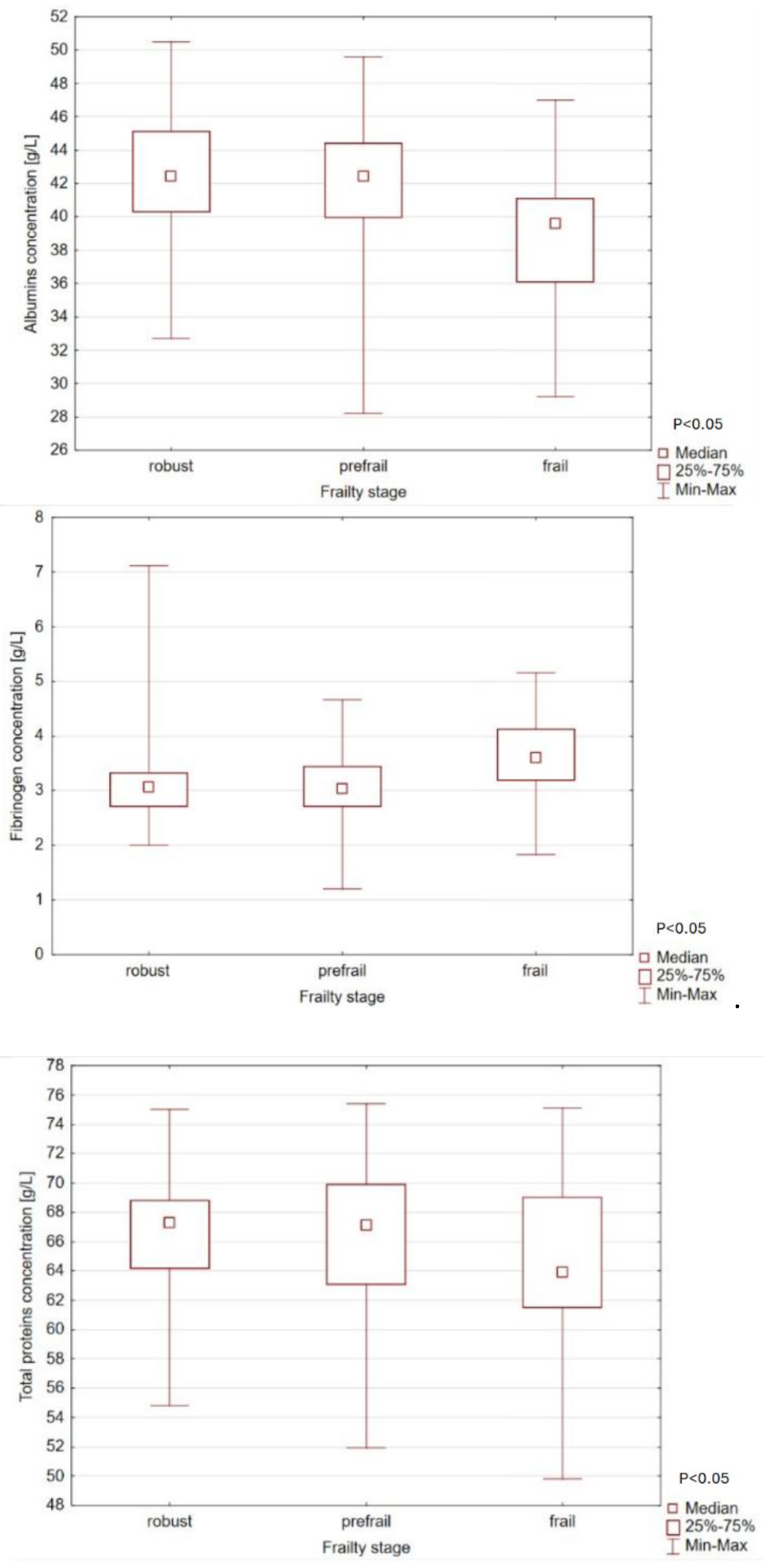

| Whole protein (g/L) | 66,2 ± 5,0 | 66,4 ± 4,45 | 66,4 ± 5,0 | 64,6 ± 6,4 | NS |

| Albumins (g/L) | 41,8 ± 3,8 | 42,5 ± 3,5 | 42,0 ± 3,7 | 39,3 ± 4,2 | <0,05 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 3,1 ± 0,7 | 3,1 ± 0,8 | 3,1 ± 0,6 | 3,6 ± 0,7 | <0,05 |

| General n=170 | Robust n=53 | Prefrail n=96 | Frail n=21 | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand strength (kg) | 30,4 ± 9,8 | 35,2 ± 8,2 | 29,3 ± 9,9 | 23,2 ± 7,0 | <0,001 |

|

Level of physical activity, (kcal/week) |

1159 (585-2050) | 1453 (830-2738) | 1229 (645-1881) | 464 (242-909) | <0,001 |

|

Slowness, (s/5meters) |

4,14 (3,4-5,27) | 3,66 (2,99- 4,31) | 4,3 (3,73- 5,26) | 6,13 (5,0-8,27) | <0,001 |

|

Exhaustion, n (%) |

65 (38%) | 0 (0%) | 48 (50%) | 17 (81%) | <0,001 |

|

Weight loss, n (%) |

33 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 20 (21%) | 13 (62%) | <0,001 |

| General n=170 | Robust n=53 | Prefrail n=96 | Frail n=21 | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARC-F | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 3 (2-4) | <0,001 |

| MNA | 26,5 (24,5-27,5) | 27 (26-28) | 26 (24,5- 27,5) | 23,5 (20-27,2) | <0,001 |

| CFS | 3 (2-3) | 3 (2-3) | 3 (2-3) | 4 (3-5) | <0,001 |

| IADL | 24 (24-24) | 24 (24-24) | 24 (24-24) | 23 (21-24) | <0,001 |

| Robust | Pre-frail | Frail | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total protein, g/L (X ± SEM) |

SARC-F 0-3 | 66.7 ± 0.7 (n=49) | 66.7 ± 0.5 (n=86) | 65.9 ± 1.4 (n=13) | P= 0.72 (frailty) P<0.01 (SARC-F) NS (both) |

| SARC-F 4-10 | 64.3 ± 2.2 (n=5) | 62.5 ± 1.6 (n=10) | 62.6 ± 1.7 (n=8) | ||

| MNA >24 | 66.5 ± 0.7 (n=48) | 66.6 ± 0.6 (n-75) | 65.7 ± 1.6 (n=10) | P=0.23 (frailty) P=0.25 (MNA) NS (both) |

|

| MNA<24 | 66.3 ± 2.1 (n=6) | 64.9 ± 1.1 (n=20) | 63.7 ± 1.5 (n=11) | ||

|

Albumin, g/L (X ± SEM) |

SARC-F 0-3 | 42.9 ± 0.5 (n=49) | 42.1 ± 0.4 (n=85) | 40.6 ± 1.0 (n=13) | P= 0.16 (frailty) P<0.01 (SARC-F) NS (both) |

| SARC-F 4-10 | 39.5 ± 1.7 (n=5) | 39.5 ± 1.2 (n=10) | 37.6 ± (n=8) | ||

| MNA >24 | 42.6 ± 0.5 (n=48) | 42.5 ± 0.4 (n=74) | 42.2 ± 1.2 (n=10) | P<0.05 (frailty) P<0.01 (MNA) NS (both) |

|

| MNA<24 | 42.5 ± 1.5 (n=6) | 39.5 ± 0.8 (n=20) | 37.8 ± 1.1 (n=11) | ||

|

Fibrynogen,g/L (X ± SEM) |

SARC-F 0-3 | 3.1 ± 0.1 (n=49) | 3.1 ± 0.1 (n=85) | 3.4 ± 0.2 (n=13) | P<0.05 (frailty) P=0.11 (SARC-F) NS (both) |

| SARC-F 4-10 | 3.3 ± 0.3 (n=5) | 3.1 ± 0.2 (n=10) | 3.8 ± 0.2 (n=8) | ||

| MNA >24 | 3.1 ± 0.1 (n=48) | 3.1 ± 0.1 (n=74) | 3.7 ± 0.2 (n=10) | P<0.05 (frailty) P=0.97 (MNA) NS (both) |

|

| MNA<24 | 3.2 ± 0.3 (n=6) | 3.1 ± 0.2 (n=20) | 3.5 ± 0.2 (n=11) |

| Robust | Pre-frail | Frail | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, kg (X±SEM) | SARC-F 0-3 | 85.0±2.1 (n=49) | 82.2±0.5 (n=86) | 81.6±4.2 (n=13) | P=0.67 (frailty) P=0.78 (SARC-F) NS (both) |

| SARC-F 4-10 | 77.0±6.7 (n=5) | 86.8±4.7 (n=10) | 82.0±5.3 (n=8) | ||

| MNA ≥24 | 82.7±2.1 (n=48) | 83.4±1.7 (n=75) | 85.8±4.7 (n=10) | P=0.09 (frailty) P=0.80 (MNA) P<0.05 (both) |

|

| MNA <24 | 96.7±6.1 (n=6) | 79.7±3.3 (n=20) | 78.1±4.5 (n=11) | ||

| Fat-free body mass, kg (X±SEM) | SARC 0-3 | 57.9±1.3 (n=49) | 55.3±1.0 (n=85) | 55.1±2.5 (n=13) | P=0.38 (frailty) P=0.71 (SARC-F) NS (both) |

| SARC 4-10 | 50.8±4.1 (n=5) | 60.0±2.9 (n=10) | 55.1±3.2 (n=8) | ||

| MNA ≥24 | 57.4±1.3 (n=48) | 56.1±1.1 (n=75) | 56.9±2.9 (n=10) | P=0.83 (frailty) P=0.29 (MNA) NS (both) |

|

| MNA <24 | 55.9±3.8 (n=6) | 54.6±2.1 (n=20) | 53.5±2.8 (n=11) | ||

| Diaphragm thickness, mm (X±SEM) | SARC 0-3 | 3.7±0.1 (n=49) | 3.8±0.1 (n=85) | 3.6±0.2 (n=13) | P=0.11 (frailty) P=0.24 (SARC-F) P=0.05 (both) |

| SARC 4-10 | 4.1±0.4 (n=5) | 3.0±0.3 (n=10) | 3.2±0.3 (n=8) | ||

| MNA ≥24 | 3.7±0.1 (n=48) | 3.7±0.1 (n=73) | 3.2±0.3 (n=10) | P=0.48 (frailty) P=0.32 (MNA) NS (both) |

|

| MNA <24 | 3.8±0.3 (n=6) | 3.6±0.2 (n=20) | 3.7±0.3 (n=11) | ||

| Gait speed, sec/5 m (X±SEM) | SARC-F 0-3 | 3.7±0.6 (n=49) | 4.4±0.5 (n=49) | 10.9±1.2 (n=49) | P<0.01 (frailty) P=0.78 (SARC-F) P<0.01 (both) |

| SARC-F 4-10 | 5.2±1.9 (n=5) | 7.1±1.4 (n=5) | 7.6±1.5 (n=5) | ||

| MNA ≥24 | 3.8±0.6 (n=48) | 4.3±0.5 (n=75) | 13.1±1.3 (n=10) | P<0.001 (frailty) P=0.09 (MNA) P<0.001 (both) |

|

| MNA <24 | 4.0±1.7 (n=6) | 6.0±0.9 (n=20) | 6.5±1.3 (n=11) | ||

| Hand-grip strength, kg (X±SEM) | SARC-F 0-3 | 36.3±1.3 (n=49) | 29.1±1.0 (n=86) | 23.7±2.5 (n=13) | P<0.05 (frailty) P<0.05 (SARC-F) NS (both) |

| SARC-F 4-10 | 26.2±4.0 (n=5) | 27.2±2.9 (n=10) | 22.3±3.2 (n=8) | ||

| MNA ≥24 | 35.8±1.3 (n=48) | 29.3±1.1 (n=75) | 22.2±2.9 (n=10) | P<0.001 (frailty) P=0.58 (MNA) NS (both) |

|

| MNA <24 | 32.0±3.7 (n=6) | 27.9±2.1 (n=20) | 24.0±2.8 (n=11) | ||

| PEF, L/min (X±SEM) | SARC-F 0-3 | 355.0±18.9 (n=46) | 311.1±14.2 (n=82) | 301.0±35.6 (n=13) | P=0.20 (frailty) P=0.09 (SARC-F) NS (both) |

| SARC-F 4-10 | 261.0±57.4 (n=5) | 331.5±45.4 (n=8) | 209.0±45.4 (n=8) | ||

| MNA ≥24 | 348.6±19.0 (n=45) | 326.3±15.1 (n=71) | 206.6±40.2 (n=10) | P=0.17 (frailty) P=0.70 (MNA) P<0.05 (both) |

|

| MNA <24 | 324.8±52.0 (n=6) | 270.0±30.0 (n=18) | 319.9±38.4 (n=11) | ||

| FEV1, L/sec (X±SEM) | SARC-F 0-3 | 2.1±0.1 (n=46) | 1.9±0.1 (n=82) | 1.7±0.2 (n=13) | P<0.01 (frailty) P=0.62 (SARC-F) NS (both) |

| SARC-F 4-10 | 1.9±0.3 (n=5) | 2.3±0.2 (n=8) | 1.3±0.3 (n=8) | ||

| MNA ≥24 | 2.1±0.1 (n=45) | 2.0±0.1 (n=71) | 1.3±0.2 (n=10) | P<0.05 (frailty) P=0.76 (MNA) P=0.06 (both) |

|

| MNA <24 | 1.6±0.3 (n=6) | 1.9±0.2 (n=18) | 1.8±0.2 (n=11) |

| Weight (kg) | Total protein (g/L) | Albumine (g/L) |

Fibrinogen (g/L) |

Fat-free body mass (kg) | Gait speed (s/5m) |

Hand-grip strength (kg) |

PEF (L/min) | FEV1 (L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 1,000000 | ||||||||

| Total protein (g/L) | 0,191716 | 1,000000 | |||||||

|

Albumine (g/L) |

0,246710 | 0,660288 | 1,000000 | ||||||

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | -0,023185 | -0,059822 | -0,189781 | 1,000000 | |||||

| Fat-free body mass (kg) | 0,664106 | 0,117959 | 0,092637 | -0,077040 | 1,000000 | ||||

| Gait speed (s/5m) | 0,048854 | 0,070348 | 0,012195 | 0,181632 | 0,013272 | 1,000000 | |||

| Hand-grip strength (kg) | 0,269100 | 0,167254 | 0,190060 | -0,146748 | 0,604307 | -0,134229 | 1,000000 | ||

| PEF (L/min) | 0,213588 | 0,070256 | 0,050982 | -0,184499 | 0,401548 | -0,127684 | 0,527768 | 1,000000 | |

| FEV1 (L) | 0,148817 | 0,064965 | 0,106164 | -0,228724 | 0,404278 | -0,110982 | 0,549269 | 0,748768 | 1,000000 |

| Diaphragm thickness (mm) | 0,115202 | 0,236871 | 0,207127 | -0,074889 | 0,049726 | -0,128065 | 0,152133 | 0,157801 | 0,132104 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).