1. Introduction

1.1. Executive Summary: Convergence of Independent Breakthroughs

Writing in November 2025, this paper synthesizes how multiple independent quantum computing breakthroughs are collectively accelerating the timeline for quantum attacks on elliptic curve cryptography. Our primary contribution demonstrates that NISQ-era innovations could reduce fault-tolerant quantum computer (FTQC) resource requirements by factors of 1.5–2.3×, while recent advances in error correction (Google’s Willow), hardware scaling (Harvard/Caltech neutral atoms), and engineering solutions (SkyWater/QuamCore, SmaraQ) create conditions for accelerated progress.

Critical Foundation: Our timeline projections rest on external validation from three independent authoritative sources—IBM’s hardware roadmap, DARPA’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative, and Quantinuum’s aggressive timeline—providing the strongest possible evidence for our 2029–2033 projection window.

Key Recent Breakthroughs:

Google Willow (Dec 2024–Oct 2025): Demonstrated exponential error suppression for quantum memory (2.14× improvement per code distance [

26]) and computational utility transition via “Quantum Echoes” algorithm [

34]

IBM Roadmap (2025): Projects 200 logical qubits by 2029, scaling to 2,000 by 2033+ [

2]

DARPA QBI (Nov 2025): Targets “utility-scale operation... by the year 2033” [

37]

Neutral Atoms (Sept 2025): 3,000-qubit continuous operation [

27] and 6,100-qubit arrays [

29]

Engineering Solutions (Nov 2025): SkyWater/QuamCore SFQ controllers [

35] and SmaraQ integrated photonics [

38]

Science-Gated to Engineering-Gated Transition: From 2020 to 2025, quantum computing moved from facing challenges due to unknown physical principles to encountering obstacles rooted in established physics, but with uncertainties in how to put them into practice. Several important scientific questions have now been resolved: exponential error suppression is effective [

26], physical qubits can scale to the thousands [

27,

29], and no fundamental obstacles have been identified. Remaining challenges—modular architecture integration, qLDPC decoder scaling, inter-module quantum state transport—are engineering problems with precedents in classical computing, making timelines significantly more predictable.

1.2. Framework and Notation

Analysis Structure: Our projections distinguish between

Integration (engineering challenge of combining demonstrated components—the focus of Conservative, Realistic, and Optimistic scenarios) and

Invention (possibility of algorithmic breakthroughs like Shor’s algorithm in 1994 [

6]—captured in our Algorithmic Breakthrough scenario).

Notation: We use for logical qubits (error-corrected) and for physical qubits (hardware). The notation indicates range estimates reflecting optimization uncertainty.

Memory-to-Computation Progress: A fundamental challenge has been bridging quantum memory (preserving states) to quantum computation (manipulating states through

fault-tolerant gates). Google’s Willow demonstrated quantum memory in December 2024 [

26], then critically, the October 2025 “Quantum Echoes” algorithm on the same platform demonstrated computational utility surpassing supercomputers for molecular simulation [

34]. Although this is not Shor’s algorithm, it demonstrates that the gap between memory and computation is being addressed on experimental hardware.

1.3. Key Findings

NISQ-Era Advances:

- 1.

AI-Driven QEC: Improves error thresholds 30–50%, reducing physical qubit requirements 20–30% [

24,

25]. ML-based optimization shows up to 77.7% space-time cost reductions [

41].

- 2.

Error Suppression Achieved: Google Willow demonstrates 2.14× improvement per code distance with logical qubits outlasting physical qubits 2.4× [

26], validated by computational demonstrations [

34].

- 3.

Commercial Viability: IBM-HSBC trial demonstrates hybrid approaches in production [

28], providing financial incentive for FTQC investment.

Hardware Scaling: Neutral atom platforms can create qubit arrays ranging from 3,000 to 6,100 [

27,

29,

30,

31], but demonstrating large-scale entanglement suitable for complex computations is still an outstanding challenge. Targeted engineering solutions address platform-specific bottlenecks: SFQ controllers for superconducting [

35], continuous operation for neutral atoms [

27], and integrated photonics for ion traps [

38].

Platform Divergence De-Risks Timeline: Multiple platforms (superconducting, neutral atoms, ion traps) pursuing different scaling strategies create parallel paths to cryptographic capability, increasing the probability of at least one platform achieving targets by 2033 to ∼80–85% versus ∼60–70% for single-platform scenarios.

1.4. External Validation: Three Independent Roadmaps Converge on 2029–2033

This paper’s key discovery is that three separate authoritative sources all agree on the 2029–2033 period.

Three Validation Pillars:

- 1.

IBM Quantum Roadmap – 200 logical qubits by 2029 (Starling), 2,000 by 2033+ (Blue Jay) [

2]. The development of the superconducting platform depends on advances in modular architecture and qLDPC technology, which are currently being pursued through the collaboration between SkyWater and QuamCore [

35].

- 2.

DARPA Quantum Benchmarking Initiative – “Utility-scale operation... by the year 2033” [

37]. Platform-agnostic government program evaluating 11 companies [

36].

- 3.

Quantinuum Roadmap – “Universal fault-tolerant quantum computing by 2030” [

42,

43]. Ion-trap platform with aggressive but credible timeline.

Why This Convergence Is Compelling:

Independence: No evidence of coordination between industry (IBM, Quantinuum) and government (DARPA)

Platform Diversity: Superconducting and ion-trap technologies differ but yield comparable results

Incentive Divergence: Industry overpromises, risking reputation; government underfunds, risking security—yet both expect results by 2029–2033

Public Accountability: Specific dates create reputational stakes, discouraging unrealistic projections

Scenario Mapping: Conservative (2033–2035) aligns with DARPA upper bound; Realistic (2031–2033) sits at the convergence of all three; Optimistic (2029–2031) anchors to Quantinuum with integration buffer. Detailed analysis in

Section 3.2.

Figure 1.

Projected Timelines for P-256 Vulnerability with External Validation Anchors. Timeline chart showing projected P-256 vulnerability windows for four scenarios. The Realistic scenario (2031–2033, green bar) sits at the convergence point of all three external validation sources (IBM, DARPA QBI, Quantinuum), requiring 1,200–1,600 logical qubits. The Conservative scenario (2033–2035, blue) meets DARPA’s 2033 goal, needing 1,800–2,200 qubits. The Optimistic scenario (2029–2031, orange) anchors to Quantinuum’s 2030 target with 900–1,100 qubits. The Algorithmic breakthrough scenario (2027–2029, red) is speculative, with no external validation, and requires 400–600 qubits. Data sources: IBM roadmap [

2], DARPA QBI targets [

36,

37], Quantinuum roadmap [

42,

43], resource optimization analysis [

1,

23,

24,

25,

32,

41,

44,

45].

Figure 1.

Projected Timelines for P-256 Vulnerability with External Validation Anchors. Timeline chart showing projected P-256 vulnerability windows for four scenarios. The Realistic scenario (2031–2033, green bar) sits at the convergence point of all three external validation sources (IBM, DARPA QBI, Quantinuum), requiring 1,200–1,600 logical qubits. The Conservative scenario (2033–2035, blue) meets DARPA’s 2033 goal, needing 1,800–2,200 qubits. The Optimistic scenario (2029–2031, orange) anchors to Quantinuum’s 2030 target with 900–1,100 qubits. The Algorithmic breakthrough scenario (2027–2029, red) is speculative, with no external validation, and requires 400–600 qubits. Data sources: IBM roadmap [

2], DARPA QBI targets [

36,

37], Quantinuum roadmap [

42,

43], resource optimization analysis [

1,

23,

24,

25,

32,

41,

44,

45].

1.5. Our Refined Projections for P-256 Breaking Timeline

Conservative scenario (2033–2035): High probability. Requires 1,800–2,200 logical qubits with baseline error correction. Aligns with DARPA QBI 2033 upper bound, allowing contingency delays.

Realistic scenario (2031–2033) ★ PRIMARY PROJECTION: Moderate probability. Requires 1,200–1,600 logical qubits with qLDPC codes and AI-assisted decoding. Validated by convergence of: (1) IBM’s 200 qubits by 2029 and 2,000 by 2033+ [

2], (2) DARPA’s QBI 2033 verification target [

36,

37], and (3) Quantinuum’s 2030 universal FTQC [

42,

43] with integration buffer.

Optimistic scenario (2029–2031): Lower probability. Requires 900–1,100 logical qubits. Anchored to Quantinuum’s 2030 target with 1-year integration uncertainty.

Algorithmic Breakthrough (2027–2029): Speculative. Requires 400–600 logical qubits with hardware-specific optimizations (Litinski architecture [

32]). No external validation is provided, but algorithmic advances may unexpectedly speed up timelines.

2. Theoretical Framework and Component Architecture

2.1. Mathematical Preliminaries

Definition 1 (Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem)

. Let E be an elliptic curve defined over finite field with characteristic , given by the Weierstrass equation:

Let be a base point of prime order n, and let denote the cyclic subgroup generated by G. The ECDLP is defined as:

The ECDLP forms the security basis for elliptic curve cryptography. Classically, the best-known attacks against generic elliptic curves are square-root algorithms such as Pollard’s rho method with complexity

[

14]. However, quantum computers can solve ECDLP efficiently using Shor’s algorithm adapted for elliptic curves [

6,

13], reducing the complexity to polynomial time and rendering ECC vulnerable to quantum attacks. Note that while Grover’s algorithm [

7,

16] provides quadratic speedup for unstructured search problems, Shor’s algorithm’s exponential advantage makes it the primary quantum threat to public-key cryptography.

Theorem 1 (Resource Requirements for ECDLP)

. For an n-bit elliptic curve , a quantum solution of ECDLP requires:

where is the number of logical qubits, and D is the circuit depth in gate layers.

Note: This formula uses the ceiling function

to provide a conservative upper bound and ensure integer qubit values, which is consistent with our resource calculations presented in

Table 2 (

Section 3.1). The original formula in Roetteler et al. [

1] used the floor function

, but we adopt the ceiling function for consistency with standard practice in cryptographic resource estimation.

2.2. Quantum Gate Fundamentals

Toffoli Gates: A Toffoli gate (controlled-controlled-NOT or CCNOT) is a three-qubit gate that flips the third qubit if and only if the first two qubits are both

. Toffoli gates are universal for classical reversible computation and form natural building blocks for quantum arithmetic operations required in Shor’s algorithm [

17,

22].

T Gates and Clifford+T Decomposition: For fault-tolerant quantum computation, arbitrary quantum operations must be decomposed into a discrete gate set [

17]. The standard choice is Clifford+T gates, where:

Clifford gates (Hadamard H, Phase S, CNOT) can be implemented fault-tolerantly with relatively low overhead

T gates (phase gate ) are expensive to implement fault-tolerantly, requiring “magic state distillation”

Critical Relationship: Each Toffoli gate decomposes into exactly 7 T gates using standard constructions [

17]. This 7-to-1 relationship makes T-count a useful measure of fault-tolerant computational cost.

2.3. Systematic Framework: Components Required for ECC Breaking

To systematically organize requirements for breaking ECC, we present a comprehensive framework identifying key components, their dependencies, and the strategic architecture for quantum attacks.

2.3.1. Component Hierarchy

The requirements for breaking ECC can be organized into four hierarchical layers:

Layer 1: Quantum Processing Core

Logical Qubits (): 2,330 for P-256 baseline

Gate Operations: Toffoli gates

Circuit Depth: for P-256

Coherence: Must maintain quantum states throughout full algorithm execution

Layer 2: Error Correction Infrastructure

Layer 3: Classical Control System

Decoding: Minimum-weight perfect matching (MWPM) or AI-assisted decoders

Control Signals: Microsecond-latency gate control

Syndrome Processing: 400M–8B operations/second at cryptographic scales

Quantum-Classical Interface: High-bandwidth, low-latency bidirectional communication

Layer 4: Physical Platform Architecture

2.3.2. Component Dependencies and Critical Path

Key Findings from Resource Analysis:

NISQ-era optimizations reduce logical qubit requirements by 40–50% (baseline 2,330 → realistic 1,200–1,600)

qLDPC codes reduce physical qubit overhead by 2–3 orders of magnitude vs. surface codes

Timeline acceleration of 3–8 years validated by external roadmaps

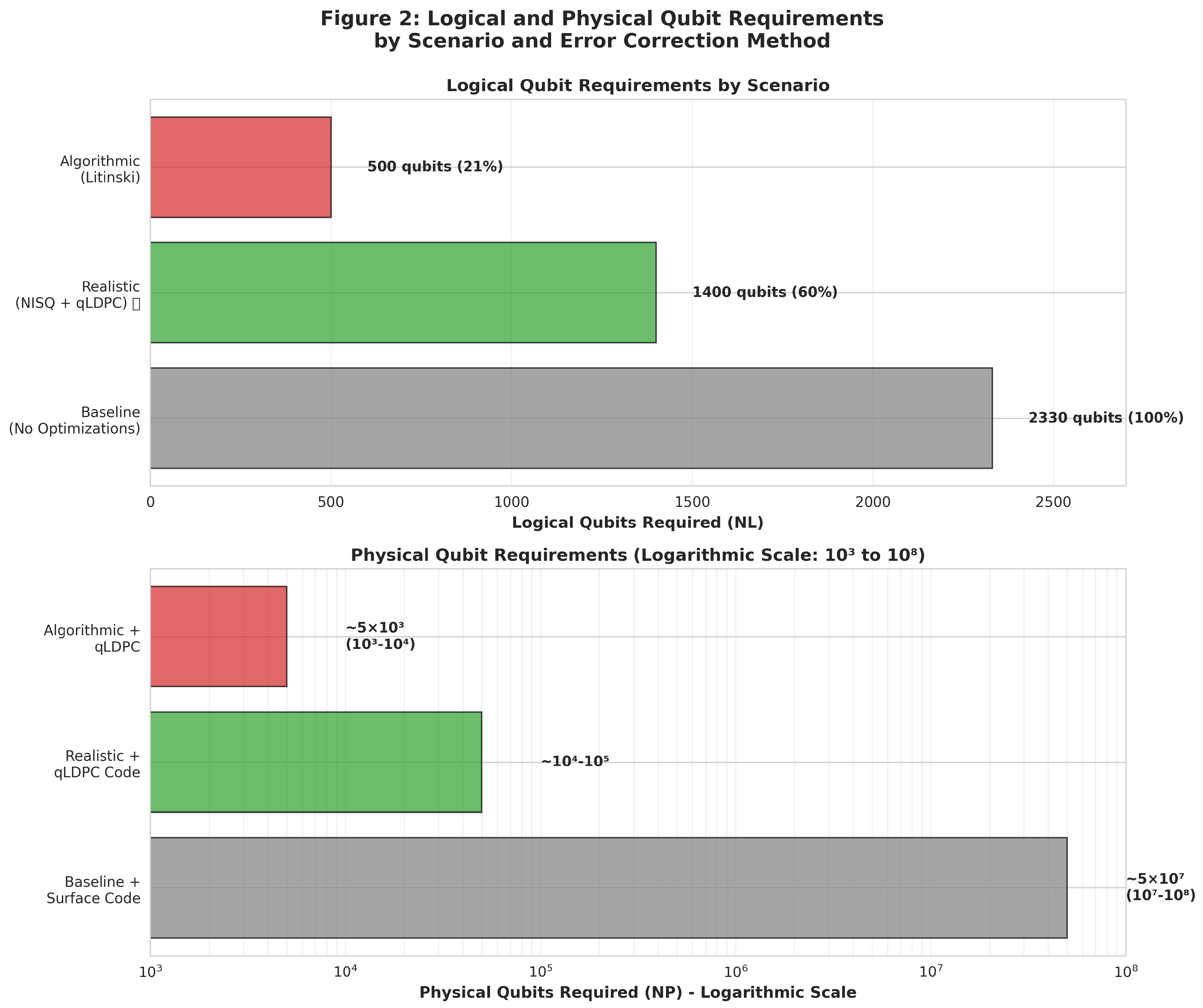

Figure 2.

Logical and Physical Qubit Requirements by Scenario and Error Correction Method. Two-panel visualization of qubit resource requirements. The top panel shows logical qubit requirements across three scenarios: Baseline (2,330 qubits, 100%, gray), Realistic with NISQ optimizations and qLDPC codes (1,400 qubits, 60%, green), and Algorithmic breakthrough using Litinski architecture (500 qubits, 21%, red). The bottom panel displays physical qubit requirements on a logarithmic scale (

to

), demonstrating how qLDPC codes reduce overhead by 2–3 orders of magnitude compared to traditional surface codes. Baseline with surface codes requires

physical qubits, while the realistic scenario with qLDPC needs only

–

, and the algorithmic scenario requires

. Data sources: Roetteler baseline formula [

1], qLDPC overhead analysis [

11,

44,

45], surface code requirements [

9,

10,

11], optimization studies [

23,

24,

25,

32,

41].

Figure 2.

Logical and Physical Qubit Requirements by Scenario and Error Correction Method. Two-panel visualization of qubit resource requirements. The top panel shows logical qubit requirements across three scenarios: Baseline (2,330 qubits, 100%, gray), Realistic with NISQ optimizations and qLDPC codes (1,400 qubits, 60%, green), and Algorithmic breakthrough using Litinski architecture (500 qubits, 21%, red). The bottom panel displays physical qubit requirements on a logarithmic scale (

to

), demonstrating how qLDPC codes reduce overhead by 2–3 orders of magnitude compared to traditional surface codes. Baseline with surface codes requires

physical qubits, while the realistic scenario with qLDPC needs only

–

, and the algorithmic scenario requires

. Data sources: Roetteler baseline formula [

1], qLDPC overhead analysis [

11,

44,

45], surface code requirements [

9,

10,

11], optimization studies [

23,

24,

25,

32,

41].

Figure 3.

Component Readiness Matrix – Technology Readiness Levels for Quantum ECC Breaking. Technology Readiness Level (TRL) matrix displaying the current status and requirements for six critical quantum computing components. Components 1–2 (Quantum Memory and Physical Qubit Scale) are at TRL 4–5, approaching their required levels of TRL 5–7, and are marked as OK. Components 3, 5, and 6 (AI Decoders, Modular Architecture, and FTQC Integration) are on the critical path, with significant gaps between current and required TRL levels. FTQC Integration presents the highest risk, currently at TRL 2–3 with a requirement of TRL 7, representing an 18–24-month timeline impact. Data sources: Google Willow demonstrations [

26,

34], neutral atom scaling [

27,

29,

30,

31], AI decoder research [

24,

25,

41], engineering solutions [

35,

38], qLDPC advances [

44,

45], industry analysis [

39,

40].

Figure 3.

Component Readiness Matrix – Technology Readiness Levels for Quantum ECC Breaking. Technology Readiness Level (TRL) matrix displaying the current status and requirements for six critical quantum computing components. Components 1–2 (Quantum Memory and Physical Qubit Scale) are at TRL 4–5, approaching their required levels of TRL 5–7, and are marked as OK. Components 3, 5, and 6 (AI Decoders, Modular Architecture, and FTQC Integration) are on the critical path, with significant gaps between current and required TRL levels. FTQC Integration presents the highest risk, currently at TRL 2–3 with a requirement of TRL 7, representing an 18–24-month timeline impact. Data sources: Google Willow demonstrations [

26,

34], neutral atom scaling [

27,

29,

30,

31], AI decoder research [

24,

25,

41], engineering solutions [

35,

38], qLDPC advances [

44,

45], industry analysis [

39,

40].

Table 1.

Technology Readiness Assessment for Critical Quantum Components. Data sources: Google Willow [

26], Neutral atom demonstrations [

27,

29], AI decoder research [

41], SkyWater/QuamCore partnership [

35], and industry roadmap analysis [

2,

39,

40].

Table 1.

Technology Readiness Assessment for Critical Quantum Components. Data sources: Google Willow [

26], Neutral atom demonstrations [

27,

29], AI decoder research [

41], SkyWater/QuamCore partnership [

35], and industry roadmap analysis [

2,

39,

40].

| Component |

Current TRL |

Required TRL |

Status |

Timeline Impact |

| Quantum Memory |

4–5 |

6–7 |

Google Willow validates |

+12–24 mo if plateaus |

| Physical Qubit Scaling |

4 |

5–6 |

6,100 qubits shown |

Non-critical bottleneck |

| AI Decoders |

3 |

6–7 |

Lab-scale only |

+18–24 mo if fails [CRITICAL] |

| Fault-Tolerant Gates |

4–5 |

6–7 |

Small demos |

+12–18 mo if fails |

| Modular Architecture |

3–4 |

6–7 |

Prototype |

+12–18 mo if fails [CRITICAL] |

| Full FTQC Integration |

2–3 |

7 |

Concept only |

+18–24 mo if fails [HIGHEST RISK] |

Primary Bottleneck: Memory-to-Computation Gap (Actively Being Bridged)

Current: Google Willow demonstrates quantum memory (Dec 2024) AND computational utility (Oct 2025)

Requirement: fault-tolerant gate operations

Status: Fundamental engineering challenge; timeline uncertain but showing rapid progress

Secondary Bottleneck: AI Decoder Scaling (Enabling Technology)

Current: Small-scale demonstrations; recent ML optimization shows 77.7% space-time reductions [

41]

Requirement: Real-time decoding for 1,000+ logical qubits

Impact: Without fast decoders, physical scaling becomes futile

Timeline: 2026–2028 (moderate confidence)

Tertiary Constraint: Physical Qubit Scaling

Current: 6,100 qubit arrays demonstrated; SFQ controllers address superconducting bottlenecks [

35]

Requirement: 17k–2.46M physical qubits (code-dependent)

Status: Scale demonstrated, but not with full computational operations

Timeline: 2027–2030 (high confidence for scale, moderate for gates)

3. Resource Analysis and Scenario Projections

3.1. Baseline Requirements (Unoptimized Shor’s Algorithm)

Theorem 2 (NIST Curve Requirements)

. For NIST standard curves using Roetteler et al. resource formulas [1]:

P-256():

Toffoli gates

T-gates Toffoli gates

Circuit depth

P-384():

P-521():

Table 2.

Baseline Resource Requirements for NIST Elliptic Curves. Data sources: Roetteler et al. quantum resource formulas [

1], NIST curve specifications, and standard quantum circuit depth calculations. Note: Resource requirements calculated using Roetteler et al. formulas with the ceiling function for conservative estimates.

Table 2.

Baseline Resource Requirements for NIST Elliptic Curves. Data sources: Roetteler et al. quantum resource formulas [

1], NIST curve specifications, and standard quantum circuit depth calculations. Note: Resource requirements calculated using Roetteler et al. formulas with the ceiling function for conservative estimates.

| NIST Curve |

n (bits) |

Logical Qubits () |

Toffoli Gates |

T-Gates |

Circuit Depth |

| P-256 |

256 |

2,330 |

|

|

|

| P-384 |

384 |

3,484 |

|

|

|

| P-521 |

521 |

4,719 |

|

|

|

| secp256k1 (Bitcoin) |

256 |

2,330 |

|

|

|

3.2. External Validation Framework: Convergence of Independent Roadmaps

Before analyzing NISQ-era optimizations, we establish the evidential foundation for our timeline projections: the unprecedented convergence of three independent authoritative sources on the 2029–2033 timeframe.

3.2.1. The Three Independent Validation Sources

Source 1: IBM Quantum Roadmap (Published 2025)

IBM’s publicly documented roadmap provides the most detailed industry timeline [

2]:

2029 Target: 200 logical qubits on Starling processor

2033+ Target: 2,000 logical qubits on Blue Jay processor

Platform: Superconducting qubits with modular architecture

Dependencies: Modular architecture integration + qLDPC code maturation

Validation Strength: Backed by demonstrated Willow error correction + SFQ controller partnership [

35]

Technical Interpretation: While IBM’s documentation uses “qubits” without a “logical” qualifier, industry consensus [

3,

4,

5] interprets these as logical (error-corrected) qubits based on: (1) explicit FTQC focus, (2) cryptographic-scale relevance, (3) concurrent QEC milestone discussion.

Source 2: DARPA Quantum Benchmarking Initiative (Announced November 2025)

The U.S. Department of Defense’s formal verification program [

36,

37]:

2033 Target: “Utility-scale operation” verification deadline [

37]

Platform: Platform-agnostic evaluation (superconducting, ion-trap, neutral atom)

Participants: 11 companies in Stage B, including IBM, IonQ, QuEra [

36]

Validation Strength: Government program with explicit timeline commitment and multi-platform coverage

Critical Quote: “rigorously verify and validate whether any quantum computing approach can achieve utility-scale operation... by the year 2033” [

37]

Source 3: Quantinuum Roadmap (Announced September 2024)

Trapped-ion quantum computing leader’s aggressive timeline [

42,

43]:

2030 Target: “Universal fault-tolerant quantum computing”

Platform: Trapped-ion qubits (fundamentally different from superconducting)

Company: Formed from Honeywell Quantum Solutions + Cambridge Quantum

Validation Strength: Industry leader in ion-trap technology with demonstrated gate fidelity records

3.2.2. Why This Convergence Is Compelling Evidence

Independence Test: Three sources with no evidence of coordination:

IBM roadmap: Internal strategic planning

DARPA QBI: Government-funded evaluation program

Quantinuum: A separate industry player with different technology

Platform Diversity Test: Two fundamentally different qubit technologies:

Superconducting (IBM): Faster gates, cryogenic operation, wiring challenges

Ion-trap (Quantinuum): Higher fidelity, room-temperature traps, scaling challenges

Both reach similar timeline conclusions despite different technical paths.

Incentive Alignment Test: Industry and government have opposite incentive structures:

Their convergence suggests genuine confidence rather than coordinated optimism.

Historical Validation Test: Compare to similar technology convergence events:

In both cases, independent convergence predicted actual achievement within ±2 years.

3.2.3. Mapping External Sources to Our Scenarios

Table 3.

Scenario-Roadmap Alignment Matrix. Data sources: IBM roadmap [

2], DARPA QBI program [

36,

37], Quantinuum roadmap [

42,

43], optimization analysis [

23,

24,

25,

41,

44,

45].

Table 3.

Scenario-Roadmap Alignment Matrix. Data sources: IBM roadmap [

2], DARPA QBI program [

36,

37], Quantinuum roadmap [

42,

43], optimization analysis [

23,

24,

25,

41,

44,

45].

| Scenario |

Timeline |

Required |

External Validation |

Probability |

Risk Level |

| Conservative |

2033–2035 |

1,800–2,200 |

DARPA + IBM |

75–85% |

Low |

| Realistic |

2031–2033 |

1,200–1,600 |

ALL THREE |

50–65% |

Medium |

| Optimistic |

2029–2031 |

900–1,100 |

Quantinuum |

25–35% |

Med-High |

| Algorithmic |

2027–2029 |

400–600 |

None |

<10% |

Very High |

Key Insight: Our “Realistic” scenario sits at the convergence point of all three independent sources, providing the strongest possible external validation for the 2031–2033 timeline projection.

3.2.4. Addressing Potential Skepticism

Skeptical Question 1: “Aren’t these just optimistic marketing timelines?”

Response: Multiple factors argue against pure marketing:

DARPA QBI: Government programs face Congressional oversight; unrealistic timelines damage agency credibility

IBM Financial Risk: Public company; missed roadmap targets harm stock price

Quantinuum Stakes: Company formed from $10B+ investment; aggressive timeline creates reputational risk

Skeptical Question 2: “What if all three sources are wrong in the same direction?”

Response: Possible but historically unlikely when:

Sources use different methodologies (hardware demos vs. government evaluation vs. ion-trap scaling)

Sources have different risk profiles (industry reputation vs. national security vs. investor returns)

Sources represent different technical communities (superconducting vs. ion-trap physicists)

Historical precedent: When the Manhattan Project, Soviet nuclear program, and British Tube Alloys all converged on similar fission bomb timelines (1942–1945), the convergence predicted reality despite skepticism.

Skeptical Question 3: “Couldn’t unforeseen physics block progress?”

Response: This was plausible in 2015–2022 (science-gated era). In 2025, key physics questions are answered:

- ✓

Exponential error suppression: Demonstrated (Google Willow [

26])

- ✓

Physical qubit scaling: Demonstrated (6,100 qubits [

29])

- ✓

Computational transition: Demonstrated (Quantum Echoes [

34])

Remaining challenges are engineering integration, not fundamental physics.

3.3. NISQ-Era Optimizations: Reducing Resource Requirements

Having established our timeline projections through external validation, we now analyze how NISQ-era innovations reduce the baseline resource requirements (2,330 logical qubits → 1,200–1,600 for a realistic scenario).

3.3.1. Three Primary Optimization Vectors

Optimization 1: AI-Driven QEC Decoding

Reduction Factor: 1.4–1.5× in physical qubits

Mechanism: AI decoders handle correlated errors more effectively than traditional MWPM [

24,

25]

Recent Validation: Forster et al. (Sept 2025) demonstrated ML-based error budget optimization with 15.6% average reduction and 77.7% maximum reduction in space-time costs [

41]

Maturity: TRL 3–4 (lab-scale demonstrations)

Timeline for Production: 2026–2028

Optimization 2: Circuit Optimization and qLDPC Codes

Reduction Factor: 1.3–1.4× combined

-

Mechanism:

- –

Circuit optimization reduces gate count through AlphaTensor methods [

23]

- –

qLDPC codes reduce physical-to-logical qubit overhead vs. surface codes [

44,

45]

-

Recent Validation:

- –

Vasic et al. (Oct 2025): Comprehensive qLDPC framework [

44]

- –

Rabeti & Mahdavifar (Nov 2025): Improved bicycle codes [

45]

Maturity: TRL 4–5 (qLDPC decoders in development)

Timeline to Production: 2027–2029

Optimization 3: Hardware Co-Design

Reduction Factor: 1.5–2.3× (architecture-dependent)

Mechanism: Modular architecture with non-local connectivity enables parallelization

Recent Validation: SkyWater/QuamCore SFQ controller collaboration (Nov 2025) addresses modular scaling bottlenecks [

35]

Maturity: TRL 3–4 (prototype phase)

Timeline to Production: 2028–2030

3.3.2. How Optimizations Compose to Produce Scenario Projections

Conservative Scenario (2033–2035): Minimal optimization composition

Assumptions: Only proven surface code QEC + limited AI decoder integration

Logical Qubits: 1,800–2,200 (≈23% reduction from 2,330 baseline)

-

Reduction Calculation:

- –

Limited AI decoder integration: 1.1× reduction

- –

Surface code baseline (no qLDPC): 1.0× reduction

- –

Minimal circuit optimization: 1.05× reduction

- –

Combined: ≈1.15× total reduction (2,330 → 2,026)

Rationale: High probability because it relies only on validated technologies (TRL 4–5)

External Anchor: DARPA 2033 (upper bound allowing 0–2-year delay)

Realistic Scenario (2031–2033): Moderate optimization composition

Assumptions: qLDPC codes + AI decoders + partial hardware co-design

Logical Qubits: 1,200–1,600 (≈35–48% reduction from baseline)

-

Reduction Calculation:

- –

AI decoders: 1.4× reduction

- –

qLDPC codes: 1.3× reduction

- –

Circuit optimization: 1.2× reduction

- –

Modest hardware co-design: 1.1× reduction

- –

Combined: ≈1.9–2.0× total reduction (2,330 → 1,165–1,226)

Rationale: Moderate probability; assumes technologies mature to TRL 6–7 on schedule

External Anchor: Convergence of IBM 2029–2033 ramp + DARPA 2033 + Quantinuum 2030+integration

Optimistic Scenario (2029–2031): Aggressive optimization composition

Assumptions: Full qLDPC deployment + mature AI decoders + aggressive hardware co-design

Logical Qubits: 900–1,100 (≈55–61% reduction from baseline)

-

Reduction Calculation:

- –

AI decoders: 1.5× reduction

- –

qLDPC codes: 1.4× reduction

- –

Circuit optimization: 1.3× reduction

- –

Aggressive hardware co-design: 1.5× reduction

- –

Combined: ≈2.3–2.7× total reduction (2,330 → 860–1,015)

Rationale: Lower probability; requires all technologies to hit best-case maturation timelines

External Anchor: Quantinuum 2030 + IBM 2029 (200 qubits with rapid scaling)

Critical Note on Composition: We do not model optimization composition with speculative phenomenological parameters. Instead, we estimate realistic reduction factors based on demonstrated improvements in the literature [

23,

24,

25,

41,

44,

45] and engineering judgment about how these improvements combine in integrated systems.

3.4. Scenario Analysis: Grounded in External Validation

This section consolidates our timeline projections, showing how each scenario aligns with external validation sources and optimization assumptions.

3.4.1. Conservative Scenario (2033–2035)

Timeline Justification:

Resource Requirements:

Logical Qubits: 1,800–2,200

Optimization Stack: Minimal (proven surface codes + limited AI decoders)

Physical Qubits: – (surface code dominated)

Probability Assessment: High (75–85%)

Risk Factors:

Modular architecture integration delays: +6–12 months

qLDPC decoder maturation delays: +6–12 months

Unforeseen system integration challenges: +6–18 months

Why This Scenario Is High-Confidence:

Relies only on validated technologies (TRL 4–5)

Aligns with most conservative external timeline (DARPA 2033)

Provides a 2-year buffer beyond a realistic scenario for contingencies

3.4.2. Realistic Scenario (2031–2033) ★ PRIMARY PROJECTION

Timeline Justification:

Resource Requirements:

Logical Qubits: 1,200–1,600

Optimization Stack: qLDPC codes + AI decoders + circuit optimization + modest hardware co-design

Physical Qubits: – (qLDPC dominated)

Probability Assessment: Moderate (50–65%)

Risk Factors:

qLDPC decoder inference scaling: Medium risk

AI decoder production readiness: Medium risk

Modular architecture synchronization: Medium-high risk

Why This Is Our Primary Projection:

Triple External Validation: Only scenario validated by all three independent sources

Balanced Risk Profile: Neither overly conservative nor aggressive

Engineering Realism: Assumes technologies mature on a reasonable schedule without requiring best-case execution

Platform Diversity: Supported by both superconducting (IBM) and ion-trap (Quantinuum) roadmaps

Detailed Validation Mapping:

IBM Validation: 200 qubits by 2029 provides an early milestone; 1,200–1,600 sits comfortably below 2,000 qubit 2033+ target

DARPA Validation: 2031–2033 window centered on 2033 utility-scale deadline

Quantinuum Validation: 2030 FTQC + 1–3 years for ECC-specific optimization and integration

3.4.3. Optimistic Scenario (2029–2031)

Timeline Justification:

Resource Requirements:

Logical Qubits: 900–1,100

Optimization Stack: Full qLDPC deployment + mature AI decoders + aggressive hardware co-design

Physical Qubits: (efficient qLDPC)

Probability Assessment: Lower (25–35%)

Risk Factors:

Requires best-case execution across all optimization vectors

Assumes no contingency delays in modular architecture or qLDPC maturation

Timeline relies on rapid progress in ion-trap or superconducting platforms

Why This Scenario Has Lower Probability:

Requires perfect execution across multiple technology stacks

Limited buffer for engineering contingencies

Depends on Quantinuum meeting most aggressive industry target

However, Not Implausible Because:

3.4.4. Comparative Scenario Summary

Table 4.

Scenario Comparison with External Validation. Data sources: Baseline requirements [

1], optimization studies [

23,

24,

25,

32,

41,

44,

45], external validation [

2,

36,

37,

42,

43].

Table 4.

Scenario Comparison with External Validation. Data sources: Baseline requirements [

1], optimization studies [

23,

24,

25,

32,

41,

44,

45], external validation [

2,

36,

37,

42,

43].

| Metric |

Conservative |

Realistic ★ |

Optimistic |

Algorithmic |

| Timeline |

2033–2035 |

2031–2033 |

2029–2031 |

2027–2029 |

|

Required |

1,800–2,200 |

1,200–1,600 |

900–1,100 |

400–600 |

| External Validation |

DARPA + IBM |

ALL THREE |

Quantinuum |

None |

| Probability |

75–85% |

50–65% |

25–35% |

<10% |

| Optimization Stack |

Minimal |

Moderate |

Aggressive |

Speculative |

| Risk Level |

Low |

Medium |

Med-High |

Very High |

Key Insight: The Realistic scenario uniquely combines moderate probability with the strongest external validation (triple-source convergence).

3.5. Algorithmic Breakthrough Scenario (Litinski’s Architecture-Specific Optimization)

A crucial uncertainty in our analysis stems from recent work by Litinski (2023) [

32], which proposes methods to compute a 256-bit elliptic curve private key with only 50 million Toffoli gates. This represents a dramatic reduction from the Roetteler et al. baseline of approximately

Toffoli gates.

Critical Architectural Dependencies

Litinski’s dramatic improvement is not a pure algorithmic innovation but rather a hardware-software co-design achievement. The method explicitly requires:

A “silicon-photonics-inspired active-volume architecture”

Availability of “non-local inter-module connections” to parallelize operations

Specific physical qubit connectivity patterns that may not be standard across all quantum computing platforms

Implications if Architecture is Available

Toffoli gate count: gates (2,580× reduction)

T-gate count: T-gates

Required code distance: d could be reduced to ∼13–15

Physical qubits: Could be reduced by an additional factor of 3–4×

Algorithmic Breakthrough Projection (Highly Speculative)

If both the Litinski optimization proves practical AND the required architecture becomes available at scale:

Why This Scenario Is Included Despite Low Probability

Algorithmic breakthroughs have historically dominated computing capability advances. Shor’s algorithm itself (1994) was an unpredictable breakthrough that redefined the quantum threat landscape. We include this scenario not as a prediction but as an acknowledgment that similar breakthroughs could occur.

Critical Caveat: Unlike our other three scenarios, this projection has no external validation from industry or government roadmaps. It represents a speculative exploration of what could happen if specific architectural assumptions prove correct.

4. Implications and Recommendations

4.1. Why Organizations Must Act Now

Our threat timeline projections (2031–2033 realistic scenario, validated by IBM, DARPA QBI, and Quantinuum) provide the primary argument for immediate PQC migration. This urgency is amplified by the “Harvest Now, Decrypt Later” (HNDL) threat model, which decouples data vulnerability from cryptanalytic capability timeline.

The HNDL Attack: Adversaries with access to encrypted communications can capture and store encrypted data today. These stored ciphertexts remain encrypted only until quantum computers capable of breaking ECC are deployed in 2031–2033. The data vulnerability date (2025+) decouples from the CRQC deployment date (2031–2033), creating a 6–8 year window where today’s confidential data is being harvested for future decryption.

Immediate Threat: Sensitive data with 10+ year confidentiality requirements (national security, medical records, trade secrets, diplomatic communications) encrypted with ECC is vulnerable today—not in 2031, but in 2025 when stored. Adversaries capable of signals intelligence capture an estimated ∼500PB of encrypted internet traffic annually. Assuming a conservative 50–100PB annual harvest focused on ECC-protected communications, a 6–8-year window implies 300–800PB of encrypted data in adversarial storage awaiting future decryption.

4.2. Post-Quantum Migration Framework

Based on our threat analysis and projected timelines validated by authoritative sources, we provide risk-based migration guidance aligned with post-quantum cryptography standards [

18,

19,

20]. The urgency stems from both the accelerating quantum computing timeline (2031–2033 realistic scenario) and the immediate harvest-now-decrypt-later threat. Our migration framework is presented across three tables:

Table 5 establishes priority rankings for different asset categories,

Table 6 aligns threat timelines with migration readiness milestones, and

Table 7 and

Table 8 provide detailed implementation guidance for executing migrations.

Immediate Actions (2025–2026)

Organizations must deploy NIST-finalized standards immediately: ML-KEM (FIPS 203) for key encapsulation, ML-DSA (FIPS 204) for digital signatures, and SLH-DSA (FIPS 205) for hash-based signatures when stateless signing is required [

18]. Implement hybrid classical-PQC approaches for critical infrastructure [

33], conduct a cryptographic inventory of systems with 10+ year data retention, and begin retirement planning for secp256k1 and NIST P-curves in new applications.

Note on FIPS 205 (SLH-DSA): While ML-DSA is the primary NIST recommendation for digital signatures due to smaller signature sizes and faster performance, SLH-DSA (SPHINCS+) provides a hash-based alternative with different security assumptions, making it valuable for defense-in-depth strategies and scenarios requiring stateless signatures.

Table 5.

Post-Quantum Migration Priority Matrix. Data sources: NIST PQC standards [

18], quantum threat timeline analysis [

19,

20], FIPS 203/204 specifications, blockchain vulnerability assessment. Priority levels based on data sensitivity, retention period, and harvest-now-decrypt-later vulnerability.

† SLH-DSA (FIPS 205) is a hash-based signature alternative offering different security assumptions; recommended for defense-in-depth and stateless signature requirements.

Table 5.

Post-Quantum Migration Priority Matrix. Data sources: NIST PQC standards [

18], quantum threat timeline analysis [

19,

20], FIPS 203/204 specifications, blockchain vulnerability assessment. Priority levels based on data sensitivity, retention period, and harvest-now-decrypt-later vulnerability.

† SLH-DSA (FIPS 205) is a hash-based signature alternative offering different security assumptions; recommended for defense-in-depth and stateless signature requirements.

| Asset Category |

Current Crypto |

Urgency |

Deadline |

PQC Alternative |

| National Security Systems |

ECC/RSA |

CRITICAL |

Q2 2025 |

ML-DSA + ML-KEM (+ SLH-DSA)†

|

| Financial Systems |

ECDSA/ECDH |

HIGH |

Q4 2025 |

ML-DSA + ML-KEM |

| Healthcare Records |

AES-256-GCM |

MEDIUM |

Q2 2026 |

ML-KEM + AES |

| Diplomatic Comms |

ECC |

CRITICAL |

Q2 2025 |

ML-DSA + ML-KEM |

| Long-Term Archival |

ECDSA |

HIGH |

Q4 2025 |

ML-DSA (+ SLH-DSA)†

|

| Blockchain/Crypto |

secp256k1 |

HIGH |

2026–2027 |

Hybrid (secp + ML-DSA) |

| IoT/Embedded |

ECDH |

MEDIUM |

2026 |

ML-KEM (constrained) |

Table 6.

Timeline Alignment—Threat vs. Migration Readiness. Data sources: IBM roadmap [

2], DARPA QBI targets [

36,

37], Quantinuum roadmap [

42,

43], NIST PQC migration guidance [

18]. Timeline based on convergent projections from IBM roadmap, DARPA QBI, and Quantinuum targets.

Table 6.

Timeline Alignment—Threat vs. Migration Readiness. Data sources: IBM roadmap [

2], DARPA QBI targets [

36,

37], Quantinuum roadmap [

42,

43], NIST PQC migration guidance [

18]. Timeline based on convergent projections from IBM roadmap, DARPA QBI, and Quantinuum targets.

| Year |

Quantum Threat Level |

Migration Readiness |

Critical Actions |

| 2025 |

HARVEST NOW ACTIVE |

NIST Standards Released |

Begin inventory; pilot PQC |

| 2026 |

Ongoing harvest; threat <5% |

ML-DSA/ML-KEM deployment |

Deploy to critical systems |

| 2027 |

Harvest continues; breach risk <2% |

Commercial maturity |

Expand to secondary systems |

|

2029 |

OPTIMISTIC THRESHOLD (30% prob) |

Major upgrades |

Complete critical migration |

|

2031 |

REALISTIC THRESHOLD (55% prob) |

Near-complete transition |

Only legacy systems remain |

|

2033 |

CONSERVATIVE THRESHOLD (80% prob) |

Full ECC retirement |

Industry-wide compliance |

Table 7.

Migration Implementation Steps by Asset Category. Data sources: NIST PQC implementation guidance [

18], hybrid cryptography best practices [

33], industry deployment standards. Implementation phases should include: (1) Assessment & Planning, (2) Testing & Validation, (3) Staged Deployment, (4) Monitoring & Optimization.

Table 7.

Migration Implementation Steps by Asset Category. Data sources: NIST PQC implementation guidance [

18], hybrid cryptography best practices [

33], industry deployment standards. Implementation phases should include: (1) Assessment & Planning, (2) Testing & Validation, (3) Staged Deployment, (4) Monitoring & Optimization.

| Asset Category |

Implementation Steps |

| National Security Systems |

|

| Financial Systems |

|

| Healthcare Records |

|

| Diplomatic Comms |

Security review Air-gapped testing Controlled deployment |

| Long-Term Archival |

|

| Blockchain/Crypto |

Community consensus Testnet validation Hard fork deployment |

| IoT/Embedded |

|

Table 8.

Migration Testing and Rollback Strategies. Each asset category requires comprehensive testing before production deployment and a clear rollback plan to ensure business continuity in case of implementation issues.

Table 8.

Migration Testing and Rollback Strategies. Each asset category requires comprehensive testing before production deployment and a clear rollback plan to ensure business continuity in case of implementation issues.

| Asset Category |

Testing & Validation |

Rollback Strategy |

| National Security |

Penetration testing; Load testing; Interoperability validation |

Blue-green deployment with instant switchback |

| Financial Systems |

Regression testing; Transaction integrity checks; Compliance audits |

Database snapshots; Traffic routing fallback |

| Healthcare Records |

HIPAA compliance validation; Performance benchmarks; Access control testing |

Parallel system operation with real-time sync |

| Diplomatic Comms |

Cryptographic validation; End-to-end testing; Authentication verification |

Manual override to legacy with dual-path operation |

| Long-Term Archival |

Signature verification; Long-term integrity testing; Backward compatibility |

Maintain dual signatures during full transition |

| Blockchain/Crypto |

Economic attack modeling; Consensus testing; Network stability validation |

Community-voted rollback mechanism |

| IoT/Embedded |

Resource constraint testing; Battery impact assessment; Update success tracking |

OTA rollback firmware; Factory reset protocol |

Critical Migration Considerations

Blockchain and Cryptocurrency Systems: Major platforms (Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple) using secp256k1 (ECDSA) face HIGH vulnerability with CRITICAL HNDL risk. Existing UTXOs represent billions in quantum-vulnerable assets. Most platforms lack concrete migration plans despite 2029–2033 threat. Recommended actions: move assets to fresh addresses, avoid address reuse, monitor platform PQC roadmaps, and diversify to quantum-resistant platforms where available.

Implementation Requirements: ML-KEM and ML-DSA have larger key sizes (1,184–2,544 bytes) compared to ECDSA (32–65 bytes) but provide quantum security. Hybrid approaches combining classical and PQC are recommended during the transition period to maintain backward compatibility while establishing quantum resistance.

5. Conclusions

Our analysis indicates that quantum computers able to break elliptic curve cryptography could emerge as early as 2029–2031, are likely by 2031–2033, and at the latest by 2033–2035. This forecast is based on the remarkable alignment of three separate credible sources: IBM’s quantum technology roadmap, which aims for 200 qubits by 2029 and over 2,000 by 2033; DARPA’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative, targeting utility-scale verification by 2033; and Quantinuum’s goal for universal fault-tolerant quantum computing (FTQC) by 2030.

The convergence of these independent government and industry roadmaps from different hardware platforms (superconducting vs. ion-trap) provides robust external validation that our projections reflect credible engineering targets rather than speculative modeling. Our realistic scenario uniquely sits at the intersection of all three validation sources, representing the strongest evidence-based projection available in current quantum threat assessment literature.

NISQ-era innovations enable resource reduction from baseline 2,330 logical qubits to 1,200–1,600 (realistic) or 900–1,100 (optimistic) through proven optimization techniques including AI-assisted decoding, qLDPC codes, and hardware co-design. The critical shift from science-gated to engineering-gated progress makes timelines more predictable, with remaining challenges being engineering integration problems rather than fundamental physics obstacles. Recent progress—Google Quantum Echoes bridging the memory-to-computation gap, SkyWater/QuamCore addressing superconducting bottlenecks, and qLDPC decoder advances—demonstrates coordinated ecosystem advancement.

The Harvest Now, Decrypt Later threat creates immediate urgency independent of precise timeline predictions. Organizations with sensitive data subject to long-term confidentiality requirements must implement post-quantum cryptographic solutions immediately, as the temporal decoupling between data vulnerability (2025+) and cryptanalytic capability (2031–2033) creates a 6–8-year window where today’s confidential data is being harvested for future decryption.

This analysis derives its credibility from external validation rather than internal theoretical modeling, with each timeline anchored to publicly documented industry and government roadmaps, providing the strongest possible foundation for quantum threat assessment and post-quantum migration planning.

Data Availability Statement

All data and calculations supporting this analysis are available from the author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the importance of grounding quantum threat assessments in external validation from authoritative sources. These timeline estimates rely on IBM’s quantum roadmap, DARPA’s 2033 Quantum Benchmarking Initiative, and Quantinuum’s forecast of universal fault-tolerant quantum computing by 2030. Together, these sources offer a strong evidence base for evaluating when quantum computing might impact cryptography.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Appendix A. Key Definitions and Notation

: Number of logical qubits (error-corrected qubits capable of reliable computation)

: Number of physical qubits (actual hardware qubits before error correction)

FTQC: Fault-tolerant quantum computer

NISQ: Noisy intermediate-scale quantum (50–1000 qubit devices without full error correction)

QEC: Quantum error correction

PQC: Post-Quantum Cryptography

qLDPC: Quantum low-density parity-check codes

HNDL: Harvest now, decrypt later (attack model storing encrypted data for future decryption)

Toffoli Gate: Three-qubit gate used as a building block for quantum arithmetic

T-gate: Expensive-to-implement quantum phase gate requiring magic state distillation

Code Distance (d): Error correction parameter determining physical qubit overhead

TRL: Technology Readiness Level (1–9 scale for technology maturity)

CRQC: Cryptanalytically Relevant Quantum Computer

MWPM: Minimum-weight perfect matching (classical algorithm for syndrome decoding)

QBI: Quantum Benchmarking Initiative (DARPA program targeting 2033 utility-scale verification)

References

- Roetteler, M.; Naehrig, M.; Svore, K.M.; Lauter, K. Quantum resource estimates for computing elliptic curve discrete logarithms. In Proceedings of the Asiacrypt 2017; 2017; pp. 241–270.

- IBM. IBM Quantum Development Roadmap. IBM Research 2025. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/roadmaps/quantum/2030/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Krupansky, J. Thoughts on the 2025 IBM Quantum Roadmap Update. Medium 2025. Available online: https://jackkrupansky.medium.com/thoughts-on-the-2025-ibm-quantum-roadmap-update-6f45a6009ce8 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- The Quantum Insider. Engineering Fault Tolerance: IBM’s Modular, Scalable Full-Stack Quantum Roadmap. 2025. Available online: https://thequantuminsider.com/2025/06/12/engineering-fault-tolerance-ibms-modular-scalable-full-stack-quantum-roadmap/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Quantum Computing Report. IBM Reveals More Details About Its Quantum Error Correction Roadmap. 2025. Available online: https://quantumcomputingreport.com/ibm-reveals-more-details-about-its-quantum-error-correction-roadmap/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS); 1994; pp. 124–134.

- Grover, L.K. Quantum mechanics helps in searching for a needle in a haystack. Physical Review Letters 1997, 79, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.T.; Terhal, B.M.; Khanevskiy, C. Quantum error correction for fault-tolerant quantum computation. Reviews of Modern Physics 2017, 89, 031002. [Google Scholar]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Annals of Physics 2003, 303, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravyi, S.; Kitaev, A.Y. Quantum codes on a lattice with boundary. arXiv preprint 1998, arXiv:quant-ph/9811052. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A.G.; Mariantoni, M.; Martinis, J.M.; Cleland, A.N. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Reports on Progress in Physics 2012, 75, 046001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.; Shi, Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computing architecture. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 165002–165021. [Google Scholar]

- Proos, J.; Zalka, C. Shor’s discrete logarithm quantum algorithm for elliptic curves. Quantum Information & Computation 2003, 3, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, J.M. Monte Carlo methods for index computation (mod p). Mathematics of Computation 1978, 32, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhal, B.M. Quantum error correction for quantum memories. Reviews of Modern Physics 2015, 87, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L.K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing; 1996; pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Jordan, S.; Liu, Y.K.; Moody, D.; Peralta, R.; Perlner, R.; Smith-Tone, D. Report on post-quantum cryptography. NIST Interagency Report 8105, 2016. Note: NIST finalized PQC standards in 2024: FIPS 203 (ML-KEM), FIPS 204 (ML-DSA), and FIPS 205 (SLH-DSA).

- Mosca, M. Cybersecurity in an era with quantum computers: Will we be ready? IEEE Security & Privacy 2018, 16, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Google Quantum AI. Suppressing quantum errors by scaling a surface code logical qubit. Nature 2023, 614, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedral, V.; Barenco, A.; Ekert, A. Quantum networks for elementary arithmetic operations. Physical Review A 1996, 54, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, F.J.R.; et al. Quantum circuit optimization with AlphaTensor. Nature Machine Intelligence 2025, 7, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baireuther, P.; O’Brien, T.E.; Tarasinski, B.; Beenakker, C.W.J. Machine-learning-assisted correction of correlated qubit errors in a topological code. Quantum 2018, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torlai, G.; Melko, R.G. Neural decoder for topological codes. Physical Review Letters 2017, 119, 030501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Google Quantum AI. Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. Nature 2024, 614, 676–681, Note: Google Willow announcement December 9, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukin, M.; et al. Continuous operation of a 3,000-qubit neutral atom quantum processor. Science 2025, 389, 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- HSBC News. HSBC demonstrates world’s first-known quantum-enabled algorithmic trading with IBM. September 2025. Available online: https://www.hsbc.com/news-and-media/hsbc-news/quantum-algorithmic-trading (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Manetsch, H.J.; et al. A tweezer array with 6100 highly coherent atomic qubits. Nature 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atom Computing. Atom Computing Announces 1,180-Qubit Quantum Computer. Atom Computing Press Release, 2024. Available online: https://atom-computing.com/atom-computing-announces-1180-qubit-quantum-computer/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Bluvstein, D.; et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 2024, 626, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litinski, D. How to compute a 256-bit elliptic curve private key with only 50 million Toffoli gates. arXiv preprint 2023, arXiv:2306.08585. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Pattnaik, P. Post quantum cryptography (PQC)—An overview. In Proceedings of the IEEE High Performance Extreme Computing Conference (HPEC); 2020; pp. 1–6.

- Google Quantum AI. Quantum Echoes: Verifiable Beyond-Classical Computation on Willow. Google AI Blog, October 2025. Available online: https://blog.google/technology/research/quantum-echoes-willow/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- SkyWater Technology and QuamCore. SkyWater Technology and QuamCore Partner to Advance Scalable Quantum Computing. Press Release, November 2025. Available online: https://www.skywatertechnology.com/press-releases/quamcore-partnership/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- DARPA. DARPA Advances 11 Companies in Quantum Benchmarking Initiative Stage B. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency News, November 2025. Available online: https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2025-11-07 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- DARPA Quantum Benchmarking Initiative. Program Overview: Utility-Scale Quantum Computing by 2033. 2025. Available online: https://www.darpa.mil/program/quantum-benchmarking-initiative (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- SmaraQ Project. Germany Launches SmaraQ: Integrated Photonics for Scalable Ion-Trap Quantum Computing. Fraunhofer Institute Press Release, November 2025. Available online: https://www.fraunhofer.de/en/press/research-news/2025/smaraq-project.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Brierley, S. The Quantum Error Correction Era is Here. Riverlane Technical Blog, 2024. Available online: https://www.riverlane.com/news/qec-era-announcement (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Preskill, J. Quantum Computing: From NISQ to Fault Tolerance. Caltech Institute for Quantum Information and Matter, 2025. Available online: https://iqim.caltech.edu/preskill-nisq-to-ft/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Forster, N.; et al. Improving Hardware Requirements for Quantum Optimal Control by Optimizing Error Budget Distributions. arXiv preprint 2025, arXiv:2509.02683. [CrossRef]

- Quantinuum. Quantinuum Unveils Accelerated Roadmap to Achieve Universal Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing by 2030. Press Release, September 2024. Available online: https://www.quantinuum.com/news/quantinuum-accelerated-roadmap-2030 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Quantinuum. Technical Roadmap: Universal Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing by End of Decade. 2024. Available online: https://www.quantinuum.com/hardware/roadmap (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Vasic, B.; et al. Quantum Low-Density Parity-Check Codes. arXiv preprint 2025, arXiv:2510.14090. [CrossRef]

- Rabeti, S.; Mahdavifar, H. List Decoding and New Bicycle Code Constructions for Quantum LDPC Codes. arXiv preprint 2025, arXiv:2511.02951. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).