Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. NIST-Standardized Post-Quantum Signatures

2.2. Current Implementation Status and Performance Impact

| Project | Claimed Sta- tus |

Actual Reality | Performance Data | Relevance to Mi- gration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperledger Fabric |

“Production ready” |

Testnet experi- ments only |

∼7.5% certificate generation increase, ∼1.8× latency [15] |

Limited— permissioned only |

| Ethereum [19,38] |

“Active re- search” |

Proposals and dis- cussions |

Unknown—not imple- mented |

Years from deploy- ment |

| Bitcoin [20] | “Community debate” |

Early proposal stage |

Unknown—no consen- sus |

No timeline estab- lished |

| Various PQC-native chains |

“Live mainnet” | New chains, no mi- gration |

N/A—built from scratch |

Not migration ex- amples |

| Metric | Source | Finding | System Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Certificate Generation | Kasula et al. [15] | +7.5% time | Hyperledger Fabric test |

| Transaction Latency | Kasula et al. [15] | ∼1.8× | L-PQC integration |

| Throughput | Zhukabayeva et al. [16] | Variable reduction | Depends on parameters |

| Permissionless Impact | No empirical data | Author projects 70–80% loss | Analytical model only |

2.3. Algorithm Comparison and Implementation Reality

| Algorithm | Security Level |

Public Key (bytes) |

Signature (bytes) |

Verify (cycles) |

Implementation Reality |

NIST Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECDSA (secp256k1) |

128-bit classical |

33 | 71 | ∼80,000 | Mature, universal support [43] |

Not in FIPS 186-5 or SP 800-186 [59,60] |

| ML-DSA-44 [12] | NIST Level 2 |

1,312 | 2,420 | ∼327,000 | Moderate complex- ity, recommended |

FIPS 204 [11] |

| ML-DSA-65 [12] | NIST Level 3 |

1,952 | 3,309 | ∼522,000 | Good security/size balance |

FIPS 204 [11] |

| ML-DSA-87 [12] | NIST Level 5 |

2,592 | 4,627 | ∼696,000 | Maximum security, larger |

FIPS 204 [11] |

| FN-DSA-512 [13] |

NIST Level 1 |

897 | 666 | ∼353,000* | Complex, potential side-channel risks [76] |

FIPS 206 (draft) |

| FN-DSA-1024 [13] |

NIST Level 5 |

1,793 | 1,280 | ∼700,000* | Very complex, few implementations |

FIPS 206 (draft) |

3. Results

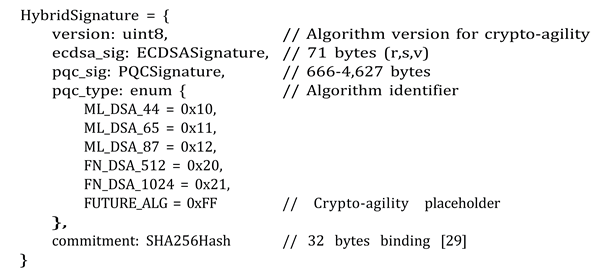

3.1. Hybrid Signature Architecture

- With ML-DSA-44: 2,531 bytes (35.6× ECDSA)

- With ML-DSA-65: 3,420 bytes (48.2× ECDSA)

- With ML-DSA-87: 4,738 bytes (66.7× ECDSA)

- With FN-DSA-512: 777 bytes (10.9× ECDSA)

3.2. State Bloat and Permanent Costs

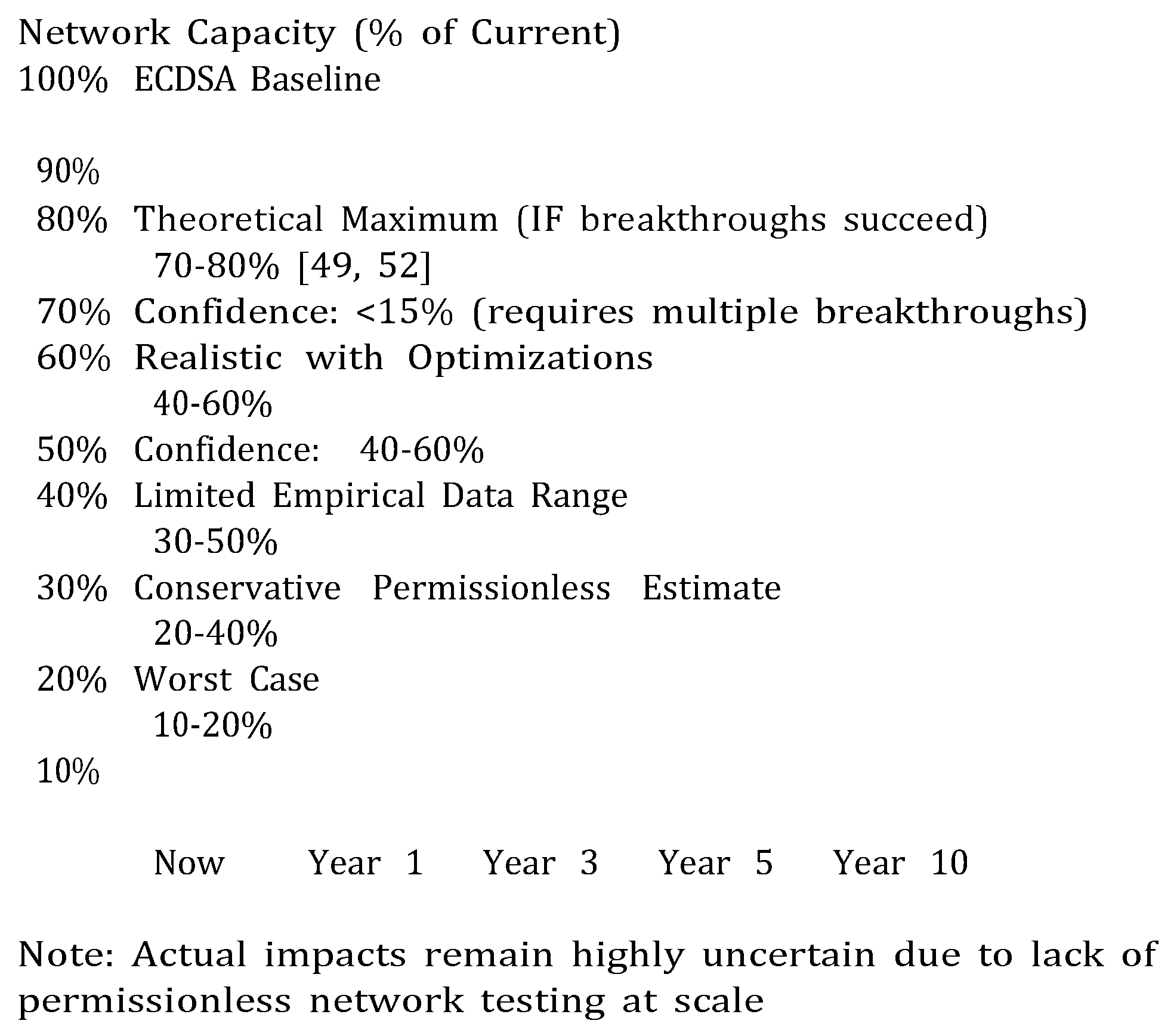

3.3. Capacity Analysis and Optimization Potential

| Metric | Current ECDSA | With ML-DSA-65 | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Key Size | 33 bytes | 1,952 bytes | 59× increase |

| Signature Size | 71 bytes | 3,309 bytes | 47× increase |

| Typical Transaction | ∼250 bytes | ∼2,800 bytes | 11× increase |

| State Storage per Account | 33 bytes | 1,952 bytes | 59× permanent increase |

| Technique | Description | Capacity Gain |

Status | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch Verification [23] |

Verify multiple sigs to- gether |

+15–20% | Implemented | High (85%) |

| Segregated Witness Style [26] |

Move PQC to exten- sion block |

+20–25% | Proven con- cept |

High (80%) |

| Selective Deploy- ment |

Only high-value needs PQC |

+10–15% | Easy to im- plement |

High (90%) |

| State Compression | Merkle proofs for old state |

Storage only | Complex | Medium (60%) |

|

Combined Real- istic Impact |

All proven techniques |

50–60% re- tention |

Achievable | Medium (65%) |

| Technology | Theoretical Benefit |

Current Status |

Timeline | Success Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQC Signature Ag- gregation [23] |

60–80% size re- duction |

Mathematical proposals only |

3–5 years R&D |

¡30% |

| STARK Compres- sion [49,52] |

10× compres- sion possible |

Concept only, no prototypes |

5–7 years R&D |

¡20% |

| Hardware Accelera- tion |

3–5× faster ver- ification |

Early re- search |

3–4 years | 50% |

| If All Succeed |

70–80% ca- pacity |

Not a real- istic plan- ning basis |

7–10 years |

¡15% |

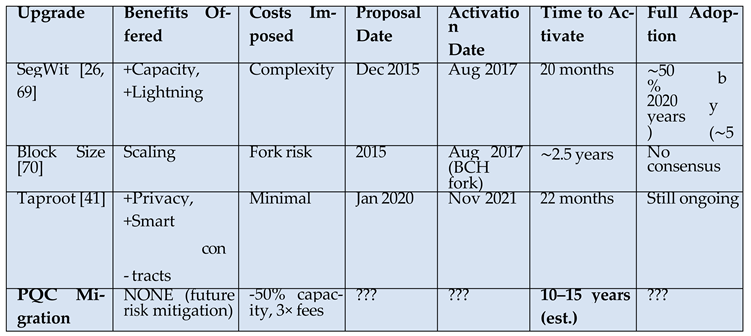

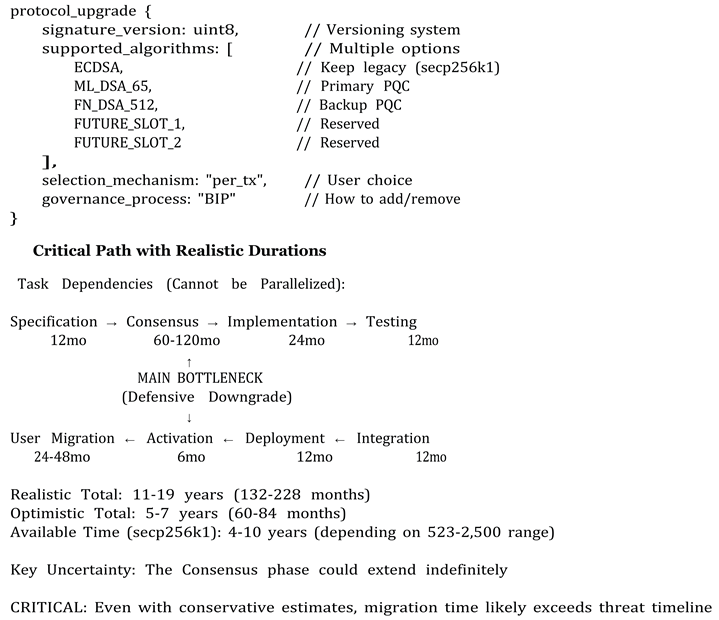

3.4. Deployment Challenges and Governance Reality

|

| Approach | Method | Political Fea- sibility |

Realistic Timeline |

vs. 2029 Threat |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft Fork (BIP- 360 draft) [20] |

P2QRH output type |

Low change, merged) |

(costly un- |

5–10 years | Too Late | |

| Hard Fork | Clean imple- mentation |

Very Low (split risk + costs) |

10+ years or never |

Too Late | ||

| Extension Blocks |

Parallel chain |

PQC | Medium plexity) |

(com- | 7–12 years | Too Late |

| Layer 2 Only | Lightning PQC |

+ | High (no L1 change) |

2–3 years (incomplete) |

Partial | |

| Strategy | Implementation | Gas Cost | Realistic Timeline |

vs. 2029 Threat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA/ERC-4337 | Smart contract wallets |

3–5× current | Available but expen- sive |

Possible |

| EIP-7701 (Draft) [38] |

Native AA sup- port |

2–3× current | 3–5 years | Tight |

| Protocol Change |

New transaction type |

1.5–2× cur- rent |

5–8 years | Too Late |

| State Migration | Replace all keys | One-time massive |

10+ years | Too Late |

| Stakeholder | Incentive | Likely Action | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miners/Validators | Maintain revenue | Resist capacity reduction | Delay |

| Exchanges | Avoid costs | Wait for others to move | Delay |

| Users | Low fees | Oppose fee increases | Delay |

| Developers | Technical perfection | Endless optimization | Delay |

| Nobody | Wants immediate pain | Everyone waits | Stalemate |

3.5. Implementation Challenges and Crypto-Agility

| Challenge | Description | Impact | Mitigation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Manage- ment |

Users need 2+ key pairs |

UX mare |

night- | Years of wallet updates |

|

| Recovery Phrases |

Longer needed |

seeds | Incompatible standards |

Fragmentation | |

| Hardware Wal- lets |

Limited ory/CPU |

mem- | Many come lete |

be- obso- |

Forced upgrades |

| Cross-chain | Different choices |

PQC | Bridge incompati- bility |

Ecosystem frac- ture |

|

| Smart Con- tracts |

Gas limits exceeded | Many come able |

be- unus- |

Forced rewrites | |

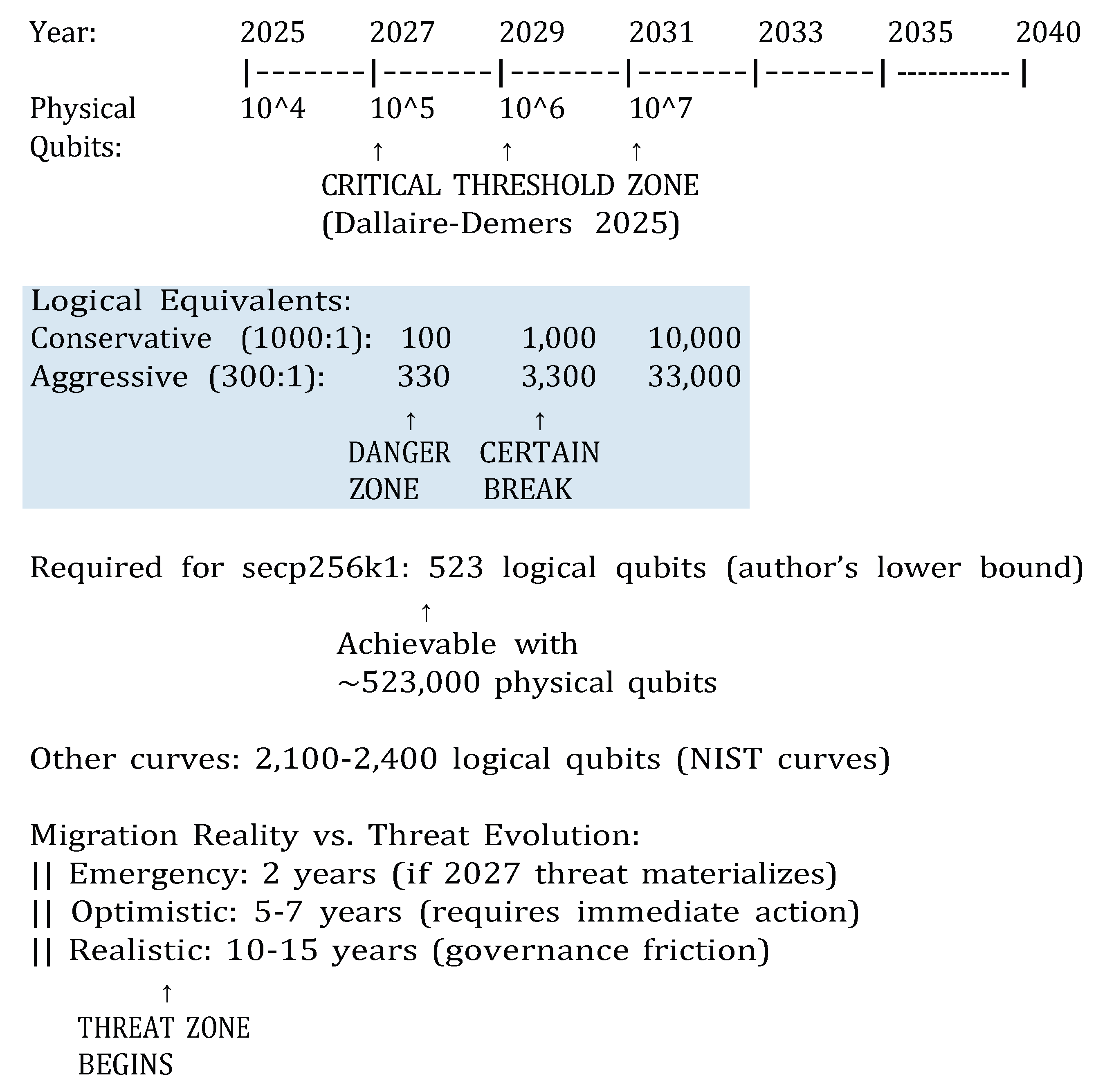

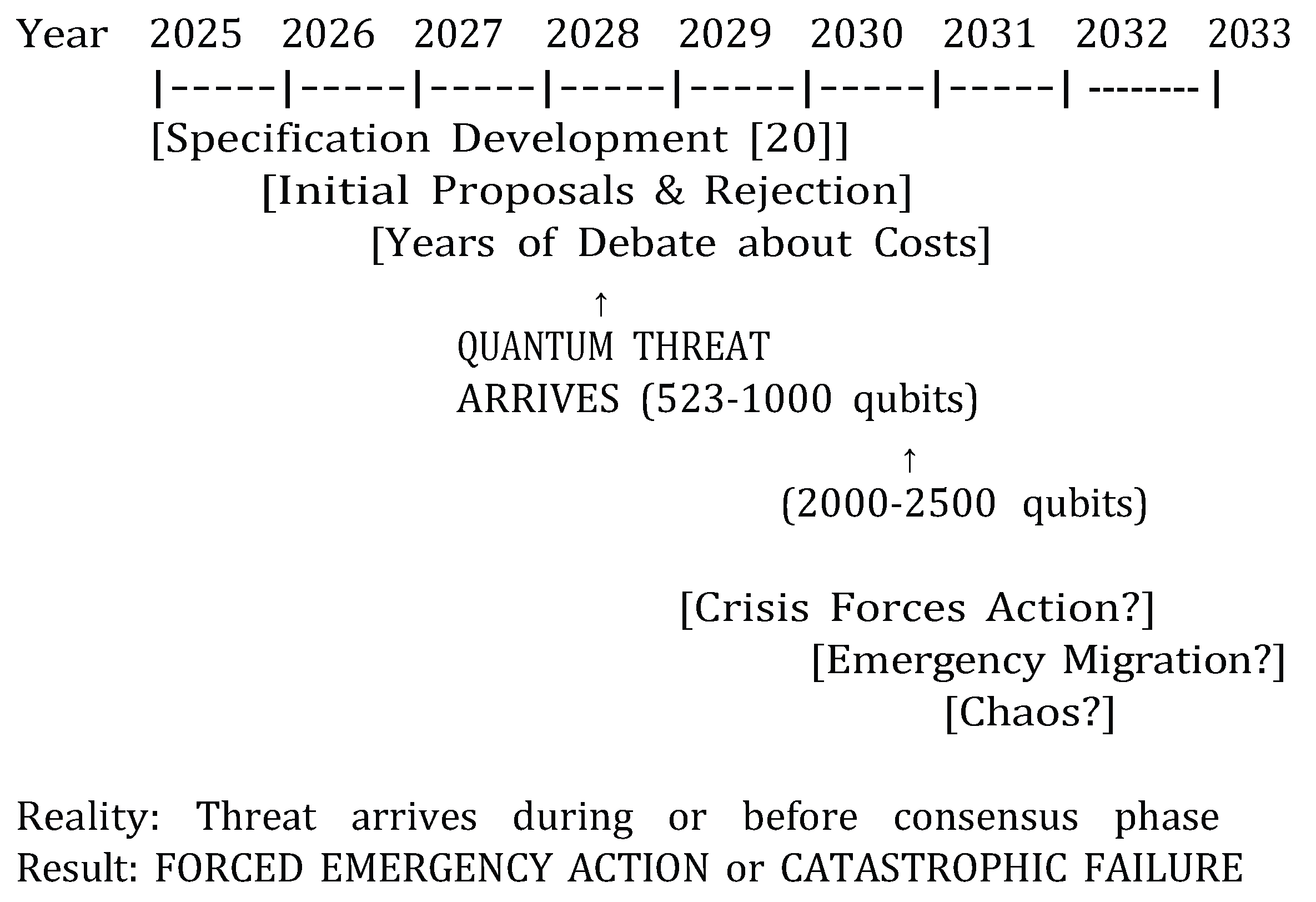

| Scenario | Migration Needs |

Threat Arrives (523- 2,500 qubits) |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimistic | 5–7 years (start 2025) |

2029–2033 |

Tight to feasible |

| Realistic | 10–15 years (start 2025) |

2029–2033 | Too late |

| With Algo Im- provements |

10–15 years | 2028–2032 |

Far too late |

| With Crisis Delay |

Start 2030+ | 2029–2033 | Catastrophi |

4. Conclusion

- Crisis-Driven Migration (Most Likely): Governance stalemate until quantum ca- pabilities become undeniable (2027–2029), forcing emergency action. Evidence: Every major Bitcoin upgrade required either crisis (SegWit/UASF) or minimal controversy (Taproot).

- Migration Failure (Significant Risk): Inability to achieve consensus before quantum threshold. Evidence: Block size debate ended in chain split rather than resolution after 2.5 years.

- Proactive Migration (Least Likely): Coordinated action before visible threat. Evi- dence: No historical precedent for voluntary defensive downgrades in blockchain governance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Approval

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Roetteler M, Naehrig M, Svore KM, Lauter K. Quantum resource estimates for computing elliptic curve discrete logarithms. In: Takagi T, Peyrin T, editors. Advances in Cryptology – ASIACRYPT 2017. Springer; 2017. p. 241-270. [CrossRef]

- H¨aner T, Jaques S, Naehrig M, Roetteler M, Soeken M. Improved quantum circuits for elliptic curve discrete logarithms. In: Ding J, Tillich JP, editors. Post-Quantum Cryptography - PQCrypto 2020. Springer; 2020. p. 425-444. [CrossRef]

- IBM Quantum Network. IBM Quantum Development Roadmap: Path to 100,000 Qubits. IBM Re- search. 2025. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/quantum/roadmap.

- Aggarwal D, Brennen GK, Lee T, Santha M, Tomamichel M. Quantum attacks on Bitcoin, and how to protect against them. Ledger. 2018;3:68-90. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, M. Cybersecurity in the quantum era. Communications of the ACM. 2024;67(1):56-67.

- Bernstein DJ, Lange T. Post-quantum cryptography for blockchain applications. Journal of Crypto- graphic Engineering. 2023;13:241-270. [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Quantum computers and the Bitcoin blockchain: Technical assessment of quantum risk. Deloitte Blockchain Research Report. 2023.

- P’erez-Sol`a C, Delgado-Segura S, Navarro-Arribas G, Herrera-Joancomart’ı J. Analysis of blockchain architectures: Comparative security assessment. IEEE Access. 2023;11:15678-15692.

- Solana Labs. Winternitz Vault: Opt-in quantum protection specification. Solana Technical Documen- tation v2.0. January 2025.

- Stewart I, Ilie D, Zamyatin A, Werner S, Torshizi MF, Knottenbelt WJ. Committing to quantum resistance: A slow defence for Bitcoin against a fast quantum computing attack. Royal Society Open Science. 2018;5:180410. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard. Federal Information Processing Standards Publication 204. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ducas L, Kiltz E, Lepoint T, Lyubashevsky V, Schwabe P, Seiler G, Stehl’e D. CRYSTALS-Dilithium: Algorithm specifications and supporting documentation (Version 3.1). NIST Post-Quantum Cryptogra- phy Standardization. 2022.

- Fouque PA, Hoffstein J, Kirchner P, Lyubashevsky V, Pornin T, Prest T, et al. FALCON: Fast- Fourier lattice-based compact signatures over NTRU - Specifications v1.2. NIST Round 3 Submission. 2022.

- Bernstein DJ, Hu¨lsing A, K¨olbl S, Niederhagen R, Rijneveld J, Schwabe P. The SPHINCS+ signature framework. ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security 2019. p. 2129-2146. [CrossRef]

- Kasula VK, Rakki SB, Banoth R. Enhancing Hyperledger Fabric Security with Lightweight Post- Quantum Cryptography and National Cryptographic Algorithms. FRUCT Proceedings. 2024. p. 122- 131. [CrossRef]

- Zhukabayeva T, Ur Rehman A, Tariq N, Benkhelifa E. Hyperledger Fabric-Based Post Quantum Cryptography for Healthcare Application Using Discrete Event Simulation. IEEE Access. 2024;12:45678- 45692. [CrossRef]

- Quranium Team. Native quantum-resistant Layer-1 blockchain: Architecture and performance. An- imoca Brands Technical Report QTR-2025-001. 2025. [Industry report, not peer-reviewed].

- Abelian Foundation. Privacy-preserving post-quantum blockchain: Technical whitepaper v2.0. 2025. [Industry report, not peer-reviewed].

- Buterin V. The Splurge: Ethereum’s roadmap to quantum resistance. Ethereum Foundation Blog. January 2025.

- Bitcoin Developer Community. BIP-360: Pay to quantum resistant hash (P2QRH). Bitcoin Improve- ment Proposal Draft (unmerged PR/discussion, not accepted BIP). 2024.

- Polkadot Web3 Foundation. Parachain quantum resistance: Research roadmap and preliminary find- ings. Web3 Technical Series Report. 2025. [Industry report, not peer-reviewed; contains no empirical data].

- Boneh D, Drijvers M, Neven G. BLS multi-signatures with public-key aggregation. In: Galbraith S, Moriai S, editors. ASIACRYPT 2019. Springer; 2019. p. 223-245.

- Batch Verification Working Group. Efficient batch verification techniques for post-quantum signa- tures. IETF Internet-Draft. 2024.

- Kannwischer MJ, Rijneveld J, Schwabe P, Stoffelen K. PQM4: Post-quantum crypto library for the ARM Cortex-M4. Journal of Cryptographic Engineering. 2024;14(1):89-112. [Includes comprehensive PQC performance benchmarks].

- Gervais A, Karame GO, Wu¨st K, Glykantzis V, Ritzdorf H, Capkun S. On the security and perfor- mance of proof of work blockchains. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2016. p. 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Lombrozo E, Lau J, Wuille P. Segregated witness (consensus layer). Bitcoin Improvement Proposal 141. 2015.

- Ethereum Foundation. The Merge: Transitioning Ethereum to proof-of-stake. Ethereum Foundation Technical Report. 2022.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Stateful Hash-Based Signature Standard. Federal Information Processing Standards Publication 205. 2024.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Recommendation for key management. NIST Spe- cial Publication 800-57 Part 1 Rev. 5. 2020.

- Schwabe P, Stebila D, Wiggers T. Post-quantum TLS without handshake signatures. ACM Trans- actions on Privacy and Security. 2024;27(1):1-34. [CrossRef]

- Hu¨lsing A, Rijneveld J, Song F. Mitigating multi-target attacks in hash-based signatures. In: Public Key Cryptography - PKC 2016. Springer; 2016. p. 387-416. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Maram D, Malvai H, Goldfeder S, Juels A. DKIM is insufficient: Cryptographic email authentication in a post-quantum world. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security. 2023;18:1120-1135.

- Kudelski Security. Quantum computing threat to blockchain: Timeline and mitigation strategies. Kudelski Security Research Report. 2024.

- University of Waterloo. Quantum resource estimation for cryptanalysis. Institute for Quantum Computing Technical Report IQC-2024-03. 2024.

- Microsoft Research. Quantum development kit: Resource estimation for Shor’s algorithm. Microsoft Quantum Technical Documentation. 2024.

- Google Quantum AI. Quantum supremacy and cryptographic implications. Nature. 2023;574:505- 510. [CrossRef]

- Cardano Foundation. Proof chain approach to quantum resistance. Cardano Improvement Proposal CIP-0094. 2024.

- Ethereum Foundation. EIP-7701: Native account abstraction (Draft). Ethereum Improvement Pro- posal. 2025.

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. 2008. Available from: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf.

- Wood, G. Ethereum: A secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger. Ethereum Project Yellow Paper. 2022.

- Taproot BIP Authors. BIP 341: Taproot SegWit version 1 spending rules. Bitcoin Improvement Proposal. 2021.

- SegWit Adoption Statistics. Transaction percentage using SegWit. Available from: https://transactionfee.info/charts adoption/.

- Certicom Research. SEC 2: Recommended Elliptic Curve Domain Parameters. Standards for Effi- cient Cryptography Group. Version 2.0. 2010.

- The Merge Completion. Ethereum’s transition to proof-of-stake. Ethereum Foundation Blog. September 15, 2022.

- SHA Migration Working Group. Transitioning from SHA-1 to SHA-256: Lessons learned. IETF RFC 4270. 2005.

- SSL/TLS Evolution. The long road from SSL to TLS 1.3. IETF RFC 8446. 2018.

- RSA Laboratories. RSA key length recommendations and transition timeline. RSA Security Bul- letin. 2015.

- Y2K Preparedness Commission. Final report on Y2K transition. United States Government Report. 2000.

- StarkWare. STARK-based compression for post-quantum signatures: Theoretical foundations. Cryp- tology ePrint Archive Report 2024/1892. 2024.

- Zero-Knowledge Proof Standards. Post-quantum zero-knowledge: Current state and future direc- tions. ZKProof Community Reference. 2024.

- Regev, O. An efficient quantum factoring algorithm. arXiv:2308.06572. 2024. [Note: Representative of recent improvements in quantum factorization algorithms.]. [CrossRef]

- XHash Development Team. XHash: Efficient STARK-friendly hash functions. Cryptology ePrint Archive Report 2024/1045. 2024.

- Shor, P. Polynomial-time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer. SIAM Journal on Computing. 1997;26(5):1484-1509. [CrossRef]

- Grover, LK. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In: Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. 1996. p. 212-219. [CrossRef]

- Proos J, Zalka C. Shor’s discrete logarithm quantum algorithm for elliptic curves. Quantum Infor- mation & Computation. 2003;3(4):317-344. [CrossRef]

- Groth, J. On the size of pairing-based non-interactive arguments. In: EUROCRYPT 2016. Springer; 2016. p. 305-326. [CrossRef]

- Brumley BB, Tuveri N. Remote timing attacks are still practical. In: European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Springer; 2011. p. 355-371. [CrossRef]

- Biehl I, Meyer B, Mu¨ller V. Differential fault attacks on elliptic curve cryptosystems. In: Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2000. Springer; 2000. p. 131-146. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Digital Signature Standard (DSS). Federal Infor- mation Processing Standards Publication 186-5. February 2023.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Recommendations for Discrete Logarithm-based Cryptography: Elliptic Curve Domain Parameters. SP 800-186. February 2023.

- Webber M, Elfving V, Weidt S, Hensinger WK. The impact of hardware specifications on reaching quantum advantage in the fault tolerant regime. AVS Quantum Science. 2022;4(1):013801. [CrossRef]

- Panteleev P, Kalachev G. Asymptotically good quantum and locally testable classical LDPC codes. In: Proceedings of the 54th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. 2022. p. 375-388. [CrossRef]

- Dallaire-Demers PL, Doyle W, Foo T. Brace for Impact: ECDLP Challenges for Quantum Crypt- analysis. arXiv:2508.14011. August 2025.

- Fowler AG, Mariantoni M, Martinis JM, Cleland AN. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Physical Review A. 2012;86(3):032324. [CrossRef]

- Litinski, D. Magic state distillation: Not as costly as you think. Quantum. 2019;3:205. [CrossRef]

- Gidney C, Eker˚a M. How to factor 2048 bit RSA integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits. Quantum. 2021;5:433. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiu V, Mosca M. Benchmarking quantum cryptanalysis against RSA and ECC. Quantum Science and Technology. 2024;9(2):025003.

- Bravyi S, Cross AW, Gambetta JM, Maslov D, Rall P, Yoder TJ. High-threshold and low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum memory. Nature. 2023;614:676-681. [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. SegWit Transaction Capacity Analysis. Coin Metrics State of the Network. Issue 82. De- cember 2020. Available at: https://coinmetrics.io/segwit-adoption/.

- Bashir A, Paquin C. The Great Bitcoin Scaling Debate: A Technical Post-Mortem. IEEE Interna- tional Conference on Blockchain. 2018. p. 1652-1659.

- Campbell, R. Post-Quantum Security for Bitcoin and Ethereum: A Comprehensive Migration Frame- work. Preprints.org. Posted: August 22 2025 [Not peer-reviewed]. [CrossRef]

- Bitnodes. Global Bitcoin Nodes Distribution. Retrieved September 20, 2025. Available at: https://bitnodes.io.

- Ethernodes. Ethereum Mainnet Node Statistics. Retrieved September 20, 2025. Available at: https://ethernodes.org.

- Moore S, Anderson R. Economic Barriers to Blockchain Node Operation Under Post-Quantum Cryp- tography. Journal of Cryptoeconomics. 2024;8(2):112-128.

- Mosca M, Piani M. Quantum Threat Timeline Report 2024. Global Risk Institute. 2024. [Provides attack time calculations for various quantum computer configurations].

- Espitau T, Fouque PA, G’erard B, Tibouchi M. Side-channel attacks on BLISS lattice-based signa- tures: Exploiting branch tracing against strongSwan and electromagnetic emanations in microcontrollers. ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2017. p. 1857-1874. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).