1. Introduction

Today, the digital transformation of healthcare systems has accelerated through the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, reducing the workload of physicians and laboratory technicians and enabling more effective, faster, and accurate healthcare services. Artificial intelligence (AI) is a field of computer science that enables the simulation of human-like abilities such as thinking, learning, decision-making, and problem-solving. The potential offered by AI in healthcare becomes particularly evident in laboratories, where data intensity is increasing and rapid decision-making processes are critical. The most fundamental and workload-intensive laboratories in hospitals—biochemistry and microbiology—are indispensable parts of diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment processes. Biochemistry laboratories analyze biochemical parameters in patients’ blood and body fluids, while microbiology laboratories detect and identify infectious agents. These laboratories serve as decision-support centers of healthcare systems, and when integrated with AI, they can reduce error rates, shorten processing times, and increase clinical accuracy, providing significant advantages [1]. Furthermore, various studies have demonstrated that AI-supported systems optimize routine processes in laboratory automation and minimize human error [2].

1.1. Artificial Intelligence and Health Systems Technologies

Healthcare systems have entered a radical transformation process with the rapid development of digital technologies. Electronic health records, big data analytics, and the proliferation of remote healthcare services constitute the fundamental building blocks of digitalization in healthcare, while artificial intelligence stands out as one of the most dynamic elements of this transformation. The use of AI technologies is increasing in many clinical processes, such as diagnosis, treatment planning, risk assessment, and disease prediction, enabling the delivery of broader, faster, and more personalized healthcare services [3].

This study examines current applications of AI technologies in biochemistry and microbiology laboratories. Through these two core units, the integration of AI into laboratory processes, its benefits, and the challenges encountered are analyzed. Furthermore, it evaluates how the digital transformation in healthcare is taking shape through these laboratories and what roadmap might be followed in the future [4].

2. Artificial Intelligence in Biochemistry Laboratories

2.1. What is Biochemistry?

Biochemistry investigates how thousands of different biomolecules interact to create the magnificent properties of living things. It examines how the inanimate groups of molecules that make up living organisms interact to ensure the continuity and immortality of life, which is achieved solely by the chemical rules that govern the inanimate universe [5].

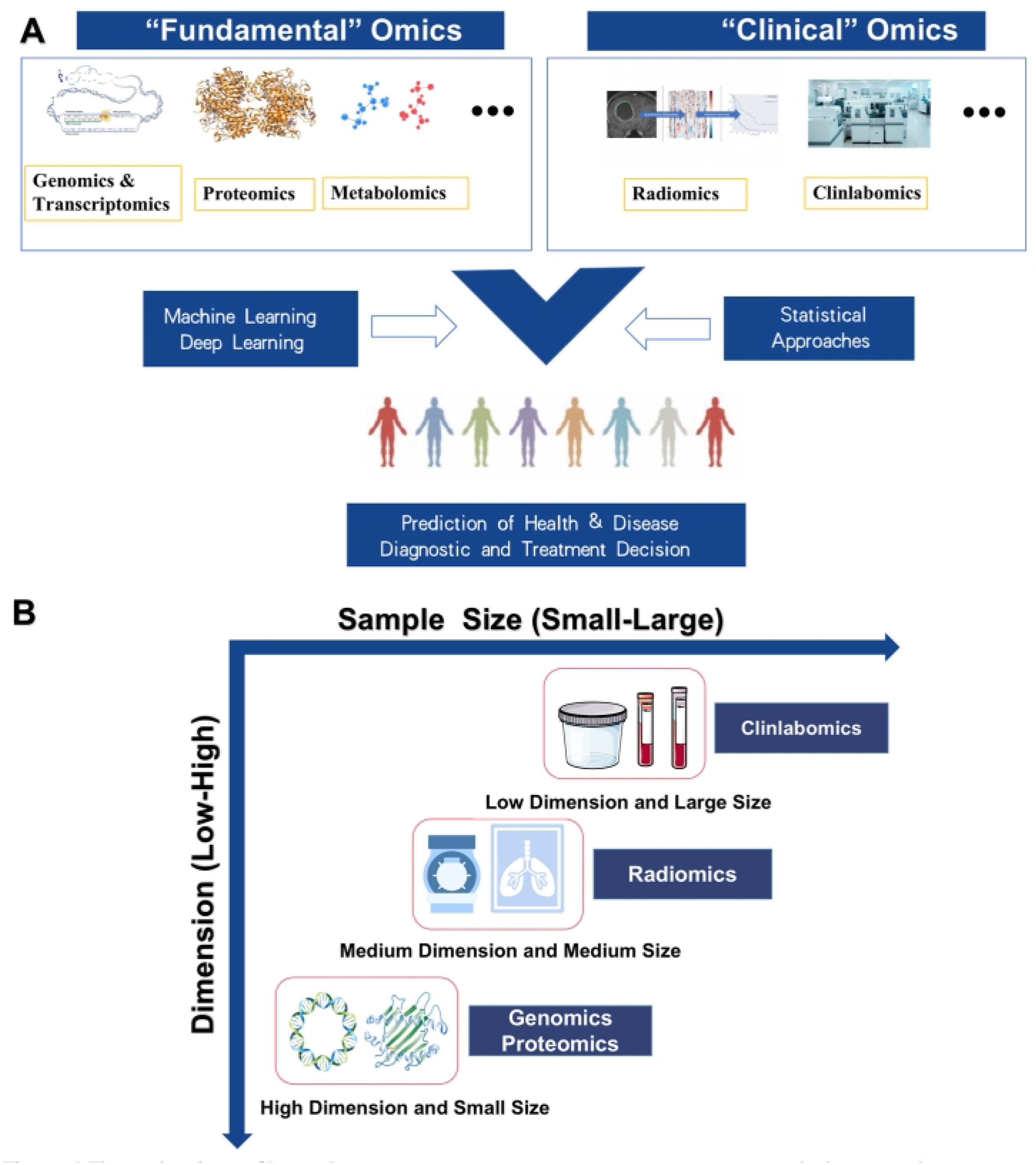

Figure 1.

A “Omics” technology, such as genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, radiomics, etc., can be used by machine learning and statistical approaches to more accurately predict and understand disease risks and adapt treatment formulations to more specific and homogeneous populations. B Differences in data structure between different omics types. [6].

Figure 1.

A “Omics” technology, such as genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, radiomics, etc., can be used by machine learning and statistical approaches to more accurately predict and understand disease risks and adapt treatment formulations to more specific and homogeneous populations. B Differences in data structure between different omics types. [6].

2.2. Biochemistry and Clinlabomics

What is Clinlabomics? Scientifically, the term can be summarized as "clinical laboratory omics." This concept refers to the conversion of daily laboratory tests into big data and their analysis using artificial intelligence and data mining techniques. This can lead to faster, more accurate, and more personalized treatment plans.

How is artificial intelligence used in laboratories? AI can be used for early disease diagnosis, risk estimation (e.g., risk of developing diabetes or cancer), and prognosis. Some of the techniques used include: machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms, decision trees, support vector machines (SVM), logistic regression, and artificial neural networks (ANNs), including deep neural networks (DNNs).

2.3. AI in Clinical Applications: Case Examples

Let’s examine some application examples:

Smoking and Aging: Models have been developed that predict smoking status and the rate of aging from blood tests.

COVID-19: The presence of COVID-19 disease and the risk of death were predicted with high success using blood tests alone.

Cancer Diagnosis: Powerful prediction models for brain, lung and colorectal cancers were created using simple blood values.

Laboratory Management: It has been shown that many processes such as detection of mislabeled samples, separation of clotted sera, and automatic determination of reference ranges can be performed with AI.

The clinlabomics approach enables biochemistry laboratories to transcend the role of simply producing numerical results and become diagnostic and predictive centers. The ability of AI techniques to extract high-level clinical significance from even simple blood tests demonstrates that routine tests are not invaluable but rather strategic sources of information. However, it’s crucial to overcome ethical, technical, and educational hurdles for these technologies to become widespread. Ultimately, thanks to clinlabomics, classical biochemistry data will become a cornerstone of AI-enabled healthcare systems in the future. [6]

2.4. Challenges and Future Perspectives of AI in Clinical Biochemistry

While AI has significantly advanced clinical biochemistry, integration and adoption challenges remain. These challenges are critical factors affecting the widespread applicability of AI. Key Challenges:

Data Privacy Concerns: Protecting sensitive patient biochemical data from breaches is vital. Because AI systems work with large datasets, ensuring the privacy and security of this data is essential to earn patient trust and comply with regulatory requirements.

Regulatory Compliance: Ensuring that AI-based diagnostics meet regulatory standards like the FDA and EU is a complex process. This requires rigorous protocols for validating, clinically proving, and continuously monitoring AI models.

AI Interpretability: Understanding how AI models derive their conclusions from biochemical data is a significant challenge, often referred to as the "black box" problem. It is critical for clinicians and researchers to understand why AI reaches a particular conclusion so they can confidently use it in clinical decision-making.

Integration with Healthcare Systems: Adapting AI solutions to existing, often complex, hospital and laboratory workflows presents a significant hurdle. This includes not only technological compatibility but also staff training, management of organizational change, and interoperability with legacy systems [7].

These challenges represent not so much the technical limitations of AI algorithms as the critical need for AI technology to evolve alongside robust ethical frameworks and governance policies. Unchecked technical progress without parallel development in these non-technical areas could seriously hinder widespread adoption and erode public trust. Successful AI integration requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes not only engineers and biochemists but also legal experts, ethicists, and policymakers. This is crucial to ensuring responsible and equitable distribution. [7] The challenge of integrating AI into healthcare systems highlights the "last mile problem" often encountered in technology adoption. This means that even highly effective AI solutions cannot reach their full potential if they cannot seamlessly fit into the complex, embedded human and infrastructure ecosystems of healthcare. This suggests that future efforts should move beyond algorithm development to focus on user-friendly design, interoperability standards, and effective change management strategies in clinical settings. This means that successful AI implementation requires a holistic approach that considers organizational dynamics and human factors as well as computational power. [7] Despite these challenges, AI-powered innovations continue to transform clinical biochemistry, paving the way for more accurate diagnoses, efficient laboratory operations, and personalized patient care. Ongoing research and technological innovations will further advance AI applications, making diagnoses more precise, laboratory processes more efficient, and personalized medicine more effective.[7]

2.5. Biochemistry and AI Conclusion

Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing clinical biochemistry by improving diagnostic accuracy, optimizing laboratory workflows, and enabling personalized medicine. AI-enabled technologies such as machine learning, deep learning, and big data analysis have significantly improved biochemical analysis, reducing human errors and increasing efficiency. The integration of AI into predictive analytics, biomarker discovery, laboratory automation, and non-invasive diagnostics has enabled more accurate disease detection, personalized treatment plans, and improved patient care.

AI-based models have demonstrated remarkable potential in analyzing large biochemical datasets, identifying complex disease patterns, and predicting disease progression. Case studies from various countries demonstrate the global impact of AI in clinical biochemistry, demonstrating its effectiveness in diagnosing conditions such as diabetes, cancer, kidney disorders, and metabolic diseases. Additionally, AI-enabled laboratory information systems (LIS) and robotic process automation (RPA) have streamlined biochemical testing, enabling better quality control and faster turnaround times. Despite these advancements, challenges such as data privacy concerns, regulatory compliance, and AI model interpretability remain significant barriers to widespread adoption. Seamless integration of AI technologies into existing healthcare and laboratory infrastructure is critical to maximizing their benefits. Going forward, ongoing research and technological innovations will further refine AI applications in clinical biochemistry, making diagnoses more precise, laboratory processes more efficient, and personalized medicine more effective. As AI continues to evolve, its role in biochemical analysis will undoubtedly shape the future of healthcare, improving both patient outcomes and the overall efficiency of medical diagnoses.

3. Artificial Intelligence in Microbiology Laboratories

Microbiology is the branch of science that studies microorganisms. Microorganisms such as bacteria, archaea, viruses, protists (protozoa, primitive algae, and primitive fungi), yeasts, and molds constitute the subject matter of microbiology. The fields of application in which microbiology is actively used are medicine, agriculture, and industry (industrial microbiology and bioengineering). Medical microbiology, or clinical microbiology, is the branch of microbiology that studies microorganisms and includes their applications in human health and medicine. It focuses particularly on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infectious diseases. It also encompasses many applications aimed at using microorganisms to improve human health. Microorganisms that cause disease in humans and fall within the scope of medical microbiology are: bacteria, fungi (yeasts and molds), protists, and viruses. Also included in the scope of medical microbiology are prions, which are infectious proteins, and plant and animal species that are parasitic on humans, although they are not microorganisms themselves.

3.1. What Does Artificial Intelligence Mean in Microbiology?

Rapid diagnosis, accurate classification, and effective treatment approaches are crucial in microbiology. While traditional analysis methods are time-consuming and prone to human error, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in this field has led to remarkable advances. In microbiology, AI has accelerated and increased the accuracy of data-based decision-making processes in microscopic image interpretation, microbiome analysis, and many other fields. In this section, we will discuss the meaning of AI in microbiology, how it is applied, and its contributions with concrete examples.

In one study, urine samples were examined by inoculating them on chromogenic agar, and AI technology was used to count and identify bacterial colonies formed in these samples. Over 1,500 urine cultures were evaluated in the study, and based on the obtained data, Faron et al. reported that the AI system demonstrated 99.8% sensitivity in colony detection compared to manual methods. Additionally, it was observed that the time to result for negative samples was reduced by 4 hours and 42 minutes, and for positive samples by 3 hours and 28 minutes. This time saving was made possible by the instant analysis of images by artificial intelligence, eliminating the need for human interpretation[8].

One of the important concepts that comes to mind when discussing bacterial studies is the microbiota. The microbiota refers to all microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi, that inhabit a specific region of the human body, while the microbiome describes the genetic material of these organisms. The genetic content of the microbiome is approximately 100 times greater than the human genome. This large dataset is being analyzed using artificial intelligence methods to develop new approaches to disease diagnosis and treatment. In recent years, machine learning, in particular, has been widely used in the analysis of microbiome data. With this method, data obtained from the microbiome is divided into operational taxonomic units (OTUs), and sequences representing each specific bacterium are classified. The resulting classification allows machine learning to make fast and accurate predictions in subsequent analyses. An example of this method is the Enbiosis project[9].

3.2. Examples of AI Applied in Medical and Clinical Microbiology

3.2.1. Bacteria/Virus Diagnosis and Microbiome/Pathogen Analysis

- a)

-

Bacterial diagnosis system with coherent imaging and DL

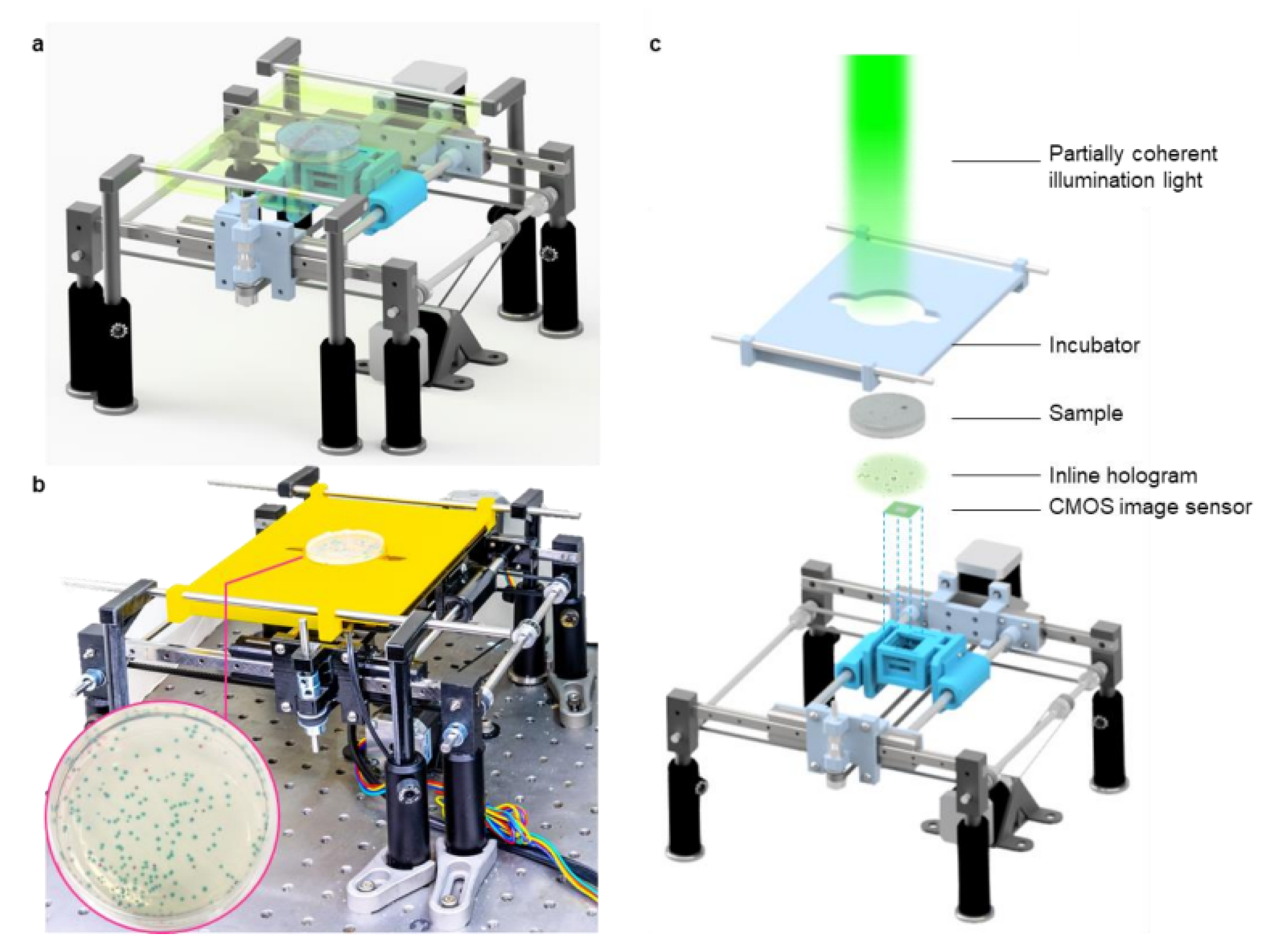

Waterborne diseases, which affect more than 2 billion people worldwide each year, are a significant economic burden and public health problem. Rapid and accurate detection of pathogens such as E. coli and coliform bacteria in drinking water is crucial. Traditional bacterial detection methods typically rely on counting colonies in petri dishes. However, this process can take 24 to 48 hours for colonies to reach visible size, and interpreting the results requires expertise. In addition to being slow, these methods can struggle to process large sample volumes.

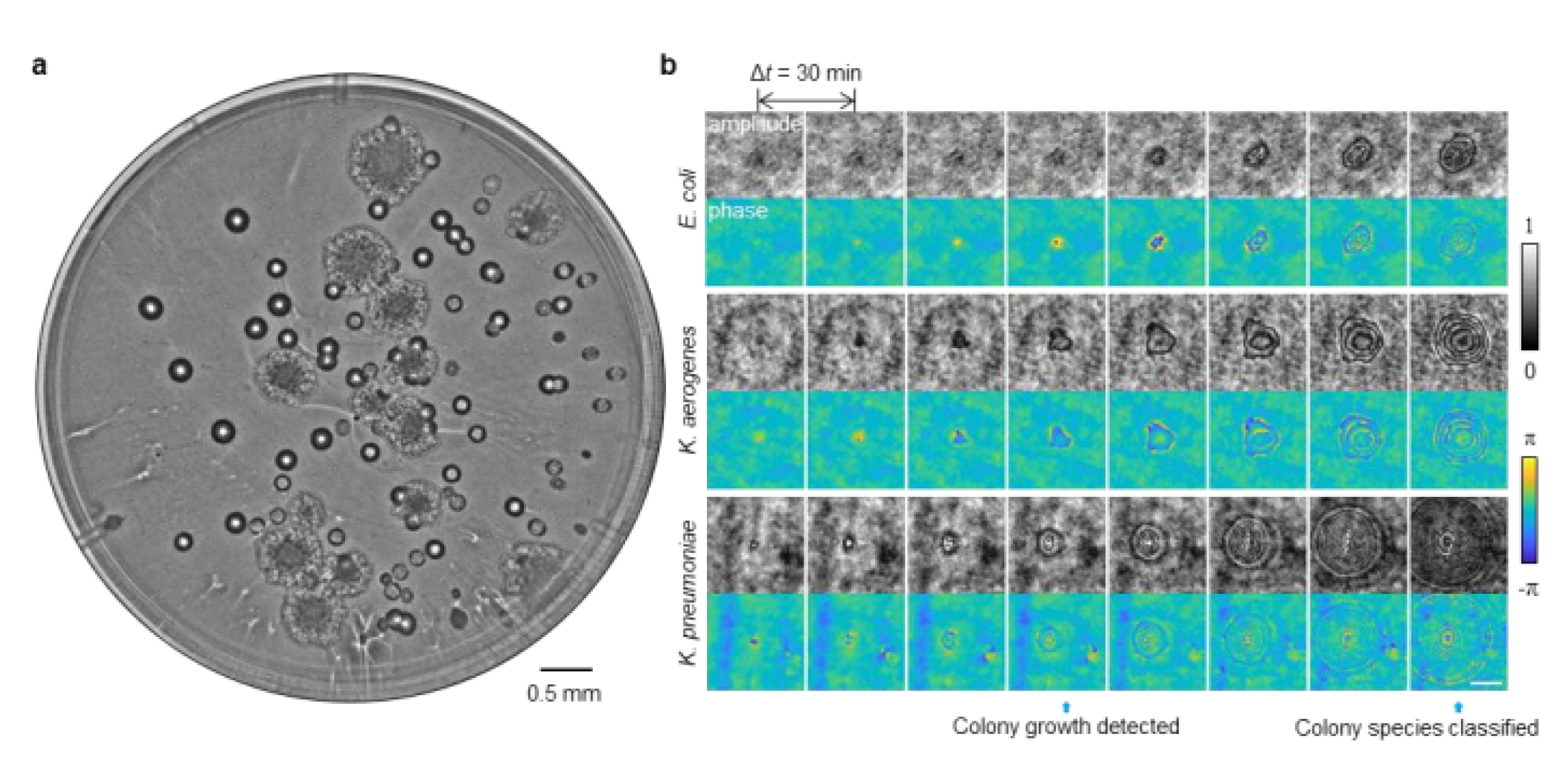

To overcome these challenges, Hongda Wang and his team developed a novel system that combines time-lapse coherent imaging and deep learning technologies. This computational system uses a lensless holographic microscopy platform to periodically image bacterial growth within a 60 mm diameter agar plate. The system’s core is two distinct deep neural networks (DNNs) that analyze the spatiotemporal properties of bacteria during their growth phase.

Step 1: Detection Network: The first network is used to detect bacterial growth at the earliest possible stage. In this stage, images of the agar plate taken over time are compared and changing objects (bacterial colonies) are identified. Step 2: Classification Network: The second network classifies the species of detected colonies (e.g., E. coli, Klebsiella aerogenes, and Klebsiella pneumoniae). By capturing the unique growth characteristics of bacteria at the microscale, this network can successfully distinguish even species that cannot be distinguished by traditional methods. This developed platform offers significant advantages over traditional methods. Test results showed that the system could detect bacteria in less than 12 hours compared to EPA-approved methods. It achieved a sensitivity of approximately 1 colony-forming unit per liter (CFU/L) in just 9 hours of total testing time. The system also maintains a high precision rate of 99.2%-100% after just 7 hours of incubation, detecting over 95% of all tested bacteria within 12 hours. Its classification capability is also impressive, reaching 97.2% accuracy for E. coli, 98.5% for K. pneumoniae, and 84% for K. aerogenes after 12 hours of incubation. The platform is extremely cost-effective, costing just 0.6 per dollar test, including all testing steps. It also boasts a high-capacity system capable of scanning the entire plate surface at a speed of 24 cm² per minute. A conventional microscope with a lens would take approximately 128 minutes to scan a plate of the same diameter. In conclusion, this automated and cost-effective deep learning-powered live bacteria detection platform has the potential to be a game-changer in microbiology. It not only significantly reduces testing time but also automates the colony identification process, eliminating the need for expert guidance.

- b)

-

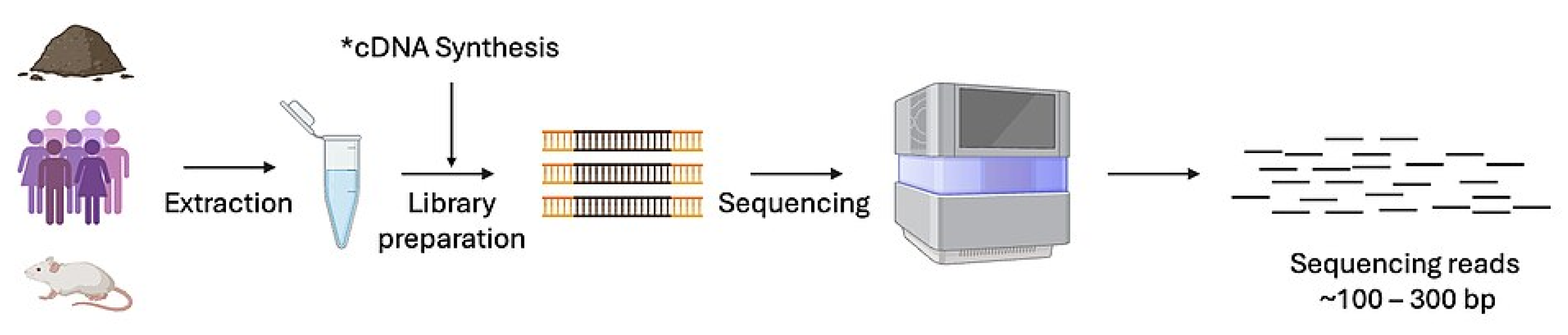

Clinical Viral Metagenomic Studies and Virome Analysis In recent years, the human microbiome—the community of trillions of microbes living within our bodies—has become one of the most exciting topics in science. However, this microscopic ecosystem also has an overlooked, even more complex component: the virome. Defined as the collection of all viruses found in an organism or the environment, the virome has a profound impact on many areas, from human health to ocean ecosystems. So, how do we analyze this invisible world? Virome analysis is a combination of molecular biology and computational techniques that aims to understand the identity, diversity, and functions of viruses by examining their genetic material (DNA or RNA). Studies in this field typically begin with a method called metagenomics, which is the bulk analysis of all genetic material in an environmental sample (e.g., soil, water, or human intestines). The basic steps are: 1. Isolation of Virus Particles: Before sampling, virus-like particles are separated from cellular components such as bacteria. This is typically accomplished through techniques such as filtration, density gradient centrifugation, and enzyme treatments. 2. Obtaining and Sequencing Genetic Material: The nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) of the isolated viruses are extracted. The genetic codes of this material are then read using next-generation sequencing technologies.

3. Bioinformatics Analysis: The resulting sequencing data is analyzed using bioinformatics tools and machine learning algorithms. In this phase, unknown viral genes are identified, viral species are classified, and genetic diversity maps are created.

Virome analysis not only detects the presence of viruses but also reveals their complex interactions with their hosts. Research on the human virome helps us understand the role of viruses in the immune system, metabolism, and even some chronic diseases (such as diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease). For example, viruses called bacteriophages, which infect only bacteria, play a critical role in maintaining the balance of the gut microbiome.

In the context of ecosystems, virome analysis is used to understand viral diversity in seawater, soil, or other environmental niches. Projects such as the Global Ocean Viromes (GOV), published in 2017, have revealed the incredible diversity of virus populations in the world’s oceans and the impact these viruses have on our planet’s biochemical cycles.

In conclusion, virome analysis is a rapidly developing field that is ushering in a new era in microbiology and ecology. Rather than viewing viruses solely as pathogens, it allows us to understand them as integral components of ecosystems and organisms. Thanks to developing technology, the discovery of this mysterious world of viruses will pave the way for groundbreaking innovations in fields such as personalized medicine and environmental management in the future.[11]

Figure 2.

a Schematic of the device. b Photograph of the lensless imaging system. c Detailed drawing of the various components of the system.

Figure 2.

a Schematic of the device. b Photograph of the lensless imaging system. c Detailed drawing of the various components of the system.

Figure 3.

a Whole agar plate image of mixed E. coli and K. aerogenes colonies after 23.5 h of incubation. b Example images (i.e., amplitude and phase) of growing colonies detected by a trained deep neural network. The detection and classification time points of growing colonies are indicated by blue arrows. The scale bar is 100 µm.

Figure 3.

a Whole agar plate image of mixed E. coli and K. aerogenes colonies after 23.5 h of incubation. b Example images (i.e., amplitude and phase) of growing colonies detected by a trained deep neural network. The detection and classification time points of growing colonies are indicated by blue arrows. The scale bar is 100 µm.

Figure 4.

Virome Metagenomic Sequencing.

Figure 4.

Virome Metagenomic Sequencing.

3.2.2. Clinical Diagnosis, AST - Clinical Decision

- a)

-

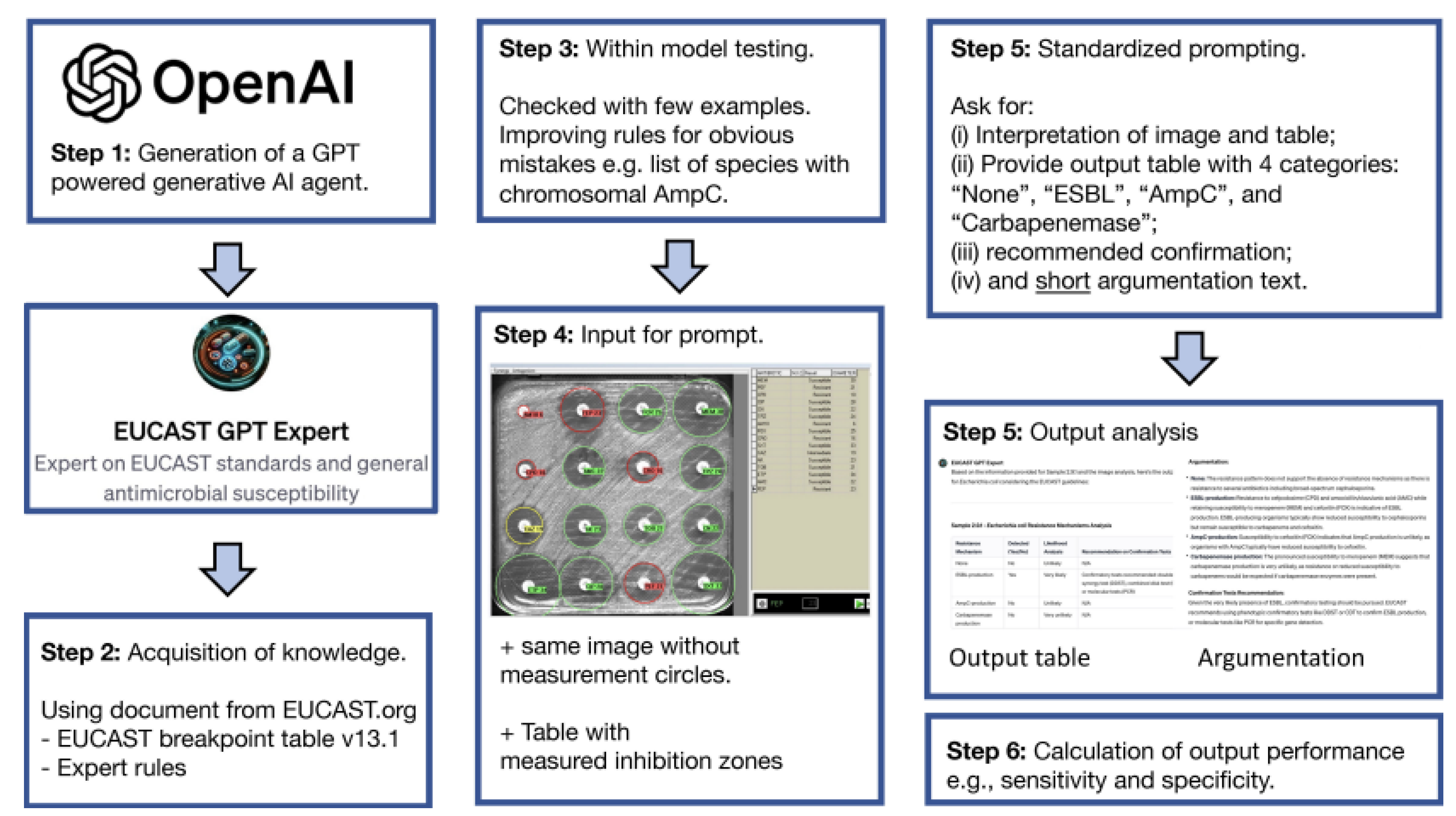

GPT-4 based EUCAST-GPT-expert

Today, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become one of the biggest threats to public health. Rapid and accurate detection of beta-lactamase-producing Gram-negative bacteria, in particular, is vital for patients to access the right treatment. Because traditional diagnostic methods are time-consuming and require expertise, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies stand out as a promising new solution in this area.

A study on this topic evaluated the ability of "EUCAST-GPT-expert," a ChatGPT-4-based AI agent, to detect potential beta-lactamase mechanisms in clinical diagnostic processes. The study highlights the strengths and current limitations of this new technology.

The researchers examined 225 laboratory-collected Gram-negative bacterial isolates. Their antibiotic resistance profiles were determined using standard methods, such as the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion test. The test results (images and measured inhibition zone diameters) were then presented in three different groups:

1-EUCAST-GPT-expert: A GPT-agent specially trained in the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines and rules

2-Microbiologists: Three expert microbiologists with at least five years of experience.

3-Uncustomized ChatGPT-4: A standard version of GPT-4 that has not undergone any special training.

All groups were asked to determine one of four resistance categories (none, ESBL, AmpC, or carbapenemase) for each isolate and to explain their decision with a brief rationale. The study compared the performance of the groups in detecting resistance mechanisms.

Figure 5.

Working principle of Chatgpt-4 Model.

Figure 5.

Working principle of Chatgpt-4 Model.

Sensitivity and Specificity: EUCAST GPT expert performed comparable to human experts in terms of sensitivity for correctly identifying resistant strains. However, the specificity rates for correctly identifying non-resistant strains as absent were lower, particularly for ESBL and AmpC. This suggests that the AI agent tends to over-flag potential resistance.

Justification: While human experts used concise, average eight words, to explain their decisions, the EUCAST-GPT-expert provided much more detailed justifications, averaging 158 words. While these detailed explanations are useful for educational purposes, they may not be practical in a routine laboratory setting.

Decision Consistency: Three human microbiologists showed a high agreement of 94.4% on phenomenological categories, while the agreement rate between three different query outputs of EUCAST-GPT-expert was at 81.9%, indicating that the human experts’ decisions were more consistent.

Importance of Customization: The study found that EUCAST-GPT-expert performed significantly better than uncustomized GPT-4. Standard GPT-4 was only able to interpret 19.6% of cases.

3.2.3. Antibiotic Discovery - Resistance Detection

- a)

-

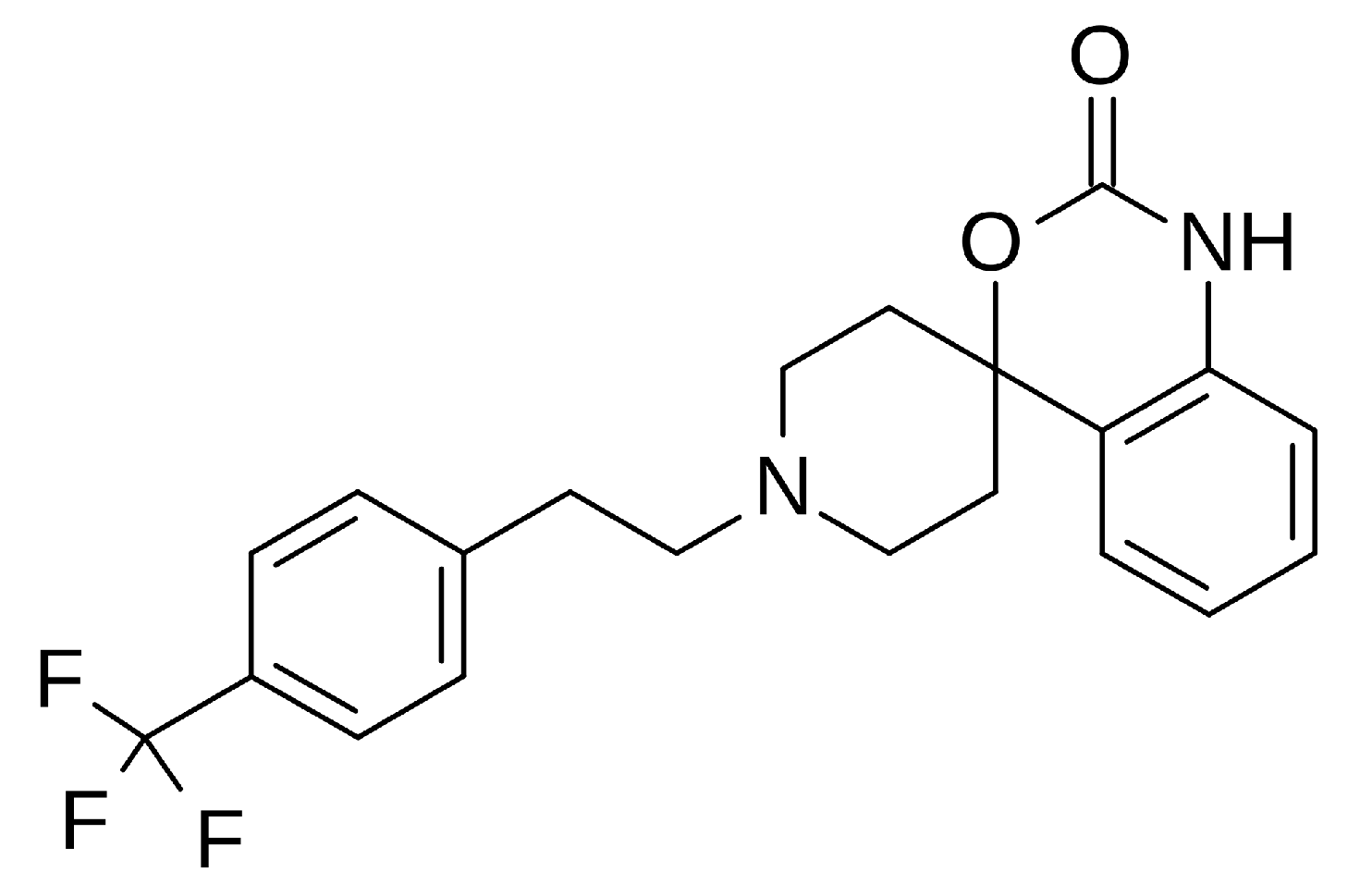

Abaucin – against Acinetobacter baumannii subspecies

Abaucin (RS-102895, MLJS-21001) is a spirocyclic phenethylamine derivative that exhibits potent activity as a narrow-spectrum antibiotic. It is particularly effective against Acinetobacter baumannii, which the World Health Organization has identified as a "critical threat." Its AI-assisted discovery was carried out by researchers from MIT and McMaster University. Its mechanism of action is based on inhibiting bacterial lipoprotein transport. Interestingly, although the molecule was previously known as a CCR2 chemokine receptor antagonist, its antibiotic property was discovered in 2023. Abaucin was screened among thousands of compounds using graph neural networks (GNN) and machine learning models. Its narrow spectrum (targeting only A. baumannii) carries the potential to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance. Its efficacy has been confirmed in skin infections and sepsis in mouse models. This discovery is a prime example of how AI can revolutionize antibiotic development [13].

- b)

-

PROSPECT / A. baumannii sample One of the most serious problems threatening public health worldwide is the development of drug resistance by microorganisms, particularly bacteria. This phenomenon, known as Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), renders previously effective treatments ineffective, prolongs illnesses, increases mortality rates, and escalates healthcare costs. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1.27 million deaths were directly attributed to bacterial AMR in 2019 alone. It is estimated that this number could reach 10 million per year by 2050. The discovery and development of new antibiotics to address this emergency is both time-consuming and costly using traditional methods. At this point, artificial intelligence (AI) technology emerges as the greatest beacon of hope in the face of this global crisis by accelerating drug discovery processes and offering new solutions.[14]

Artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms, analyze massive amounts of biological data to develop systems that mimic human intelligence. These technologies are being integrated into drug development processes, accelerating the discovery of new antibiotics. Traditionally, discovering a new drug involved lengthy and laborious steps, such as synthesizing thousands of chemicals derived from existing drugs and testing them for activity and toxicity. AI is transforming this process with multi-dimensional approaches:

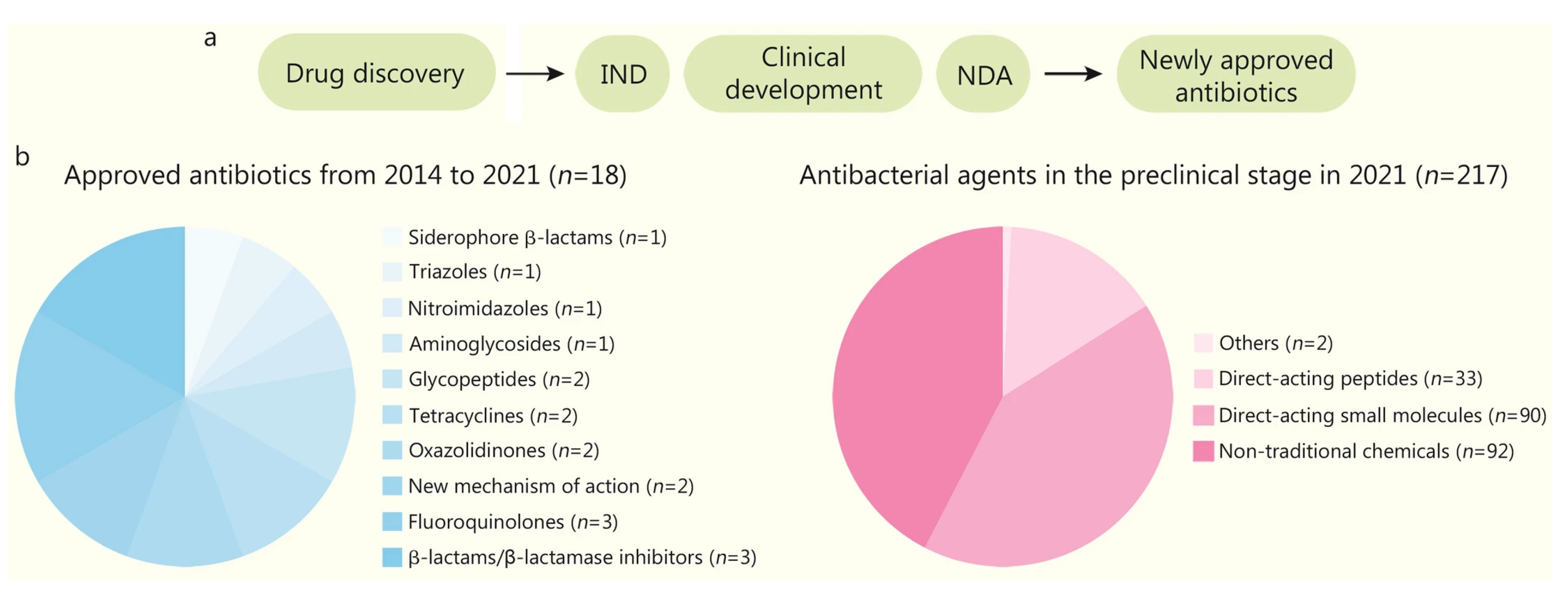

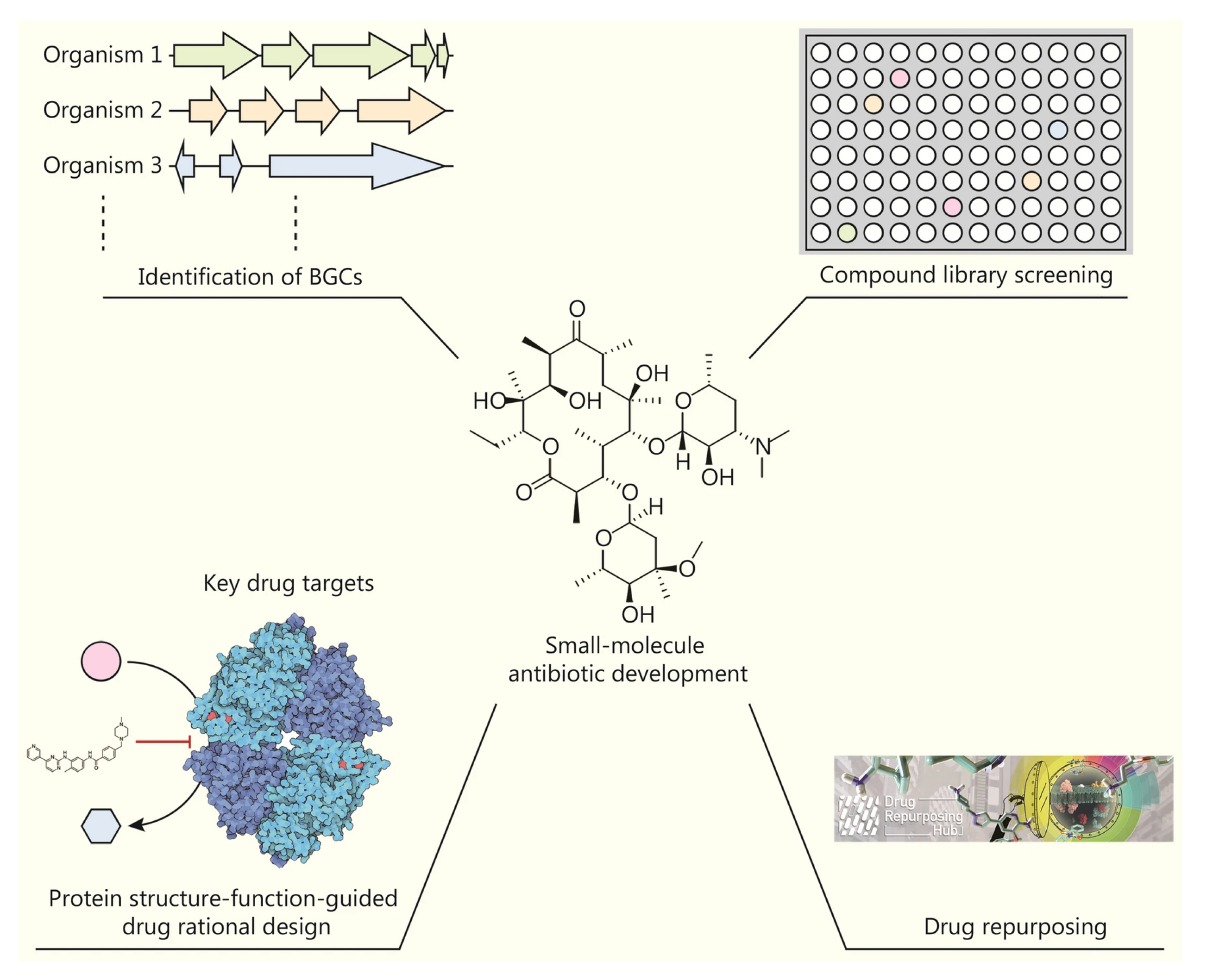

1-Development of Small Molecule Antibiotics:

Discovery of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs): In nature, many microorganisms harbor BGCs, which encode secondary metabolites with the potential to be developed into new antibiotics. However, most of these genes belong to organisms that cannot be cultured in vitro. To address this challenge, AI uses deep learning algorithms such as DeepBGC and DeepRiPP to predict new BGC classes and the chemical activity of their products from genetic data. Screening of Compound Libraries: Unlike traditional screening methods, machine learning-based screening can explore broad chemical spaces in silico. This significantly increases the likelihood of discovering structurally and functionally novel compounds with potent antibacterial properties. For example, a message-passing deep neural network trained on growth inhibition data from over 7,500 FDA-approved compounds discovered aubacin, a narrow-spectrum antibiotic that targets lipoprotein trafficking and has a novel mechanism of action (MOA).[14]

2-Protein Structure Prediction and Rational Drug Design: AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold: Understanding the three-dimensional structure of a drug’s target protein is fundamental to rational drug design. Traditional methods are slow and technically challenging. AlphaFold2, developed by DeepMind, has revolutionized this field by predicting protein structure with near-experimental accuracy. RoseTTAFold, on the other hand, can predict protein-protein interactions directly from protein sequences.

Problems and Solutions: Despite these powerful tools, accurately predicting how drug candidates bind to their targets remains challenging.

Despite the high quality of AlphaFold2 predictions, the performance of docking methods is limited. Therefore, improving docking calculations using machine learning-based scoring functions is critical to overcoming these hurdles.[14]

3-Design of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMP):

Unique Mechanisms of Action: AMPs are short peptides, generally consisting of 2-50 amino acids, produced by multicellular organisms against pathogens. They act by directly interacting with the bacterial membrane, disrupting physiological processes such as cell wall synthesis, cell division, and membrane permeability. They can also prevent the formation of biofilms resistant to conventional antibiotics. AI-Assisted Design: AI plays a key role in the design and modification of new AMPs. According to the WHO’s 2021 report, 15.2% of 217 preclinical chemicals are direct-acting peptides. This demonstrates the growing interest in biologic drugs.[14]

4-Development of Bacteriophage (Phage) Therapy: Phage Discovery and Classification: Phages, viruses that infect bacteria, are a promising alternative to the AMR crisis. AI has become an important tool for studying phages from natural sources. AI-powered tools such as PHACTS and BACPHLIP can classify phages as virulent (non-lysogenic) or temperate (lysogenic), facilitating the selection of the most suitable phages for treatment. These tools have achieved impressive accuracy rates of 99% and 98%, respectively.[14]

Figure 6.

Chemical structure of Abaucin, RS-102895, an antibiotic.

Figure 6.

Chemical structure of Abaucin, RS-102895, an antibiotic.

Figure 7.

The process of developing new antibiotics (a) and the current status (b). New drugs discovered in laboratories must undergo various stages before approval, including Investigational New Drug (IND) applications, clinical development, and New Drug Applications (NDAs). Unconventional chemicals include bacteriophage/phage products (n=28), indirect-acting small molecules (n=23), large molecules (n=19), biologics (antibodies or others, n=8), immunomodulators (n=7), nucleic acid-based products (n=4), indirect-acting peptides (n=2), and microbiome-modifying agents (n=1).[14]

Figure 7.

The process of developing new antibiotics (a) and the current status (b). New drugs discovered in laboratories must undergo various stages before approval, including Investigational New Drug (IND) applications, clinical development, and New Drug Applications (NDAs). Unconventional chemicals include bacteriophage/phage products (n=28), indirect-acting small molecules (n=23), large molecules (n=19), biologics (antibodies or others, n=8), immunomodulators (n=7), nucleic acid-based products (n=4), indirect-acting peptides (n=2), and microbiome-modifying agents (n=1).[14]

Figure 8.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in small molecule antibiotic development is enabling the extraction of secondary metabolites from biosynthetic gene clusters, screening of existing compounds, and repurposing of FDA-approved drugs.[14]

Figure 8.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in small molecule antibiotic development is enabling the extraction of secondary metabolites from biosynthetic gene clusters, screening of existing compounds, and repurposing of FDA-approved drugs.[14]

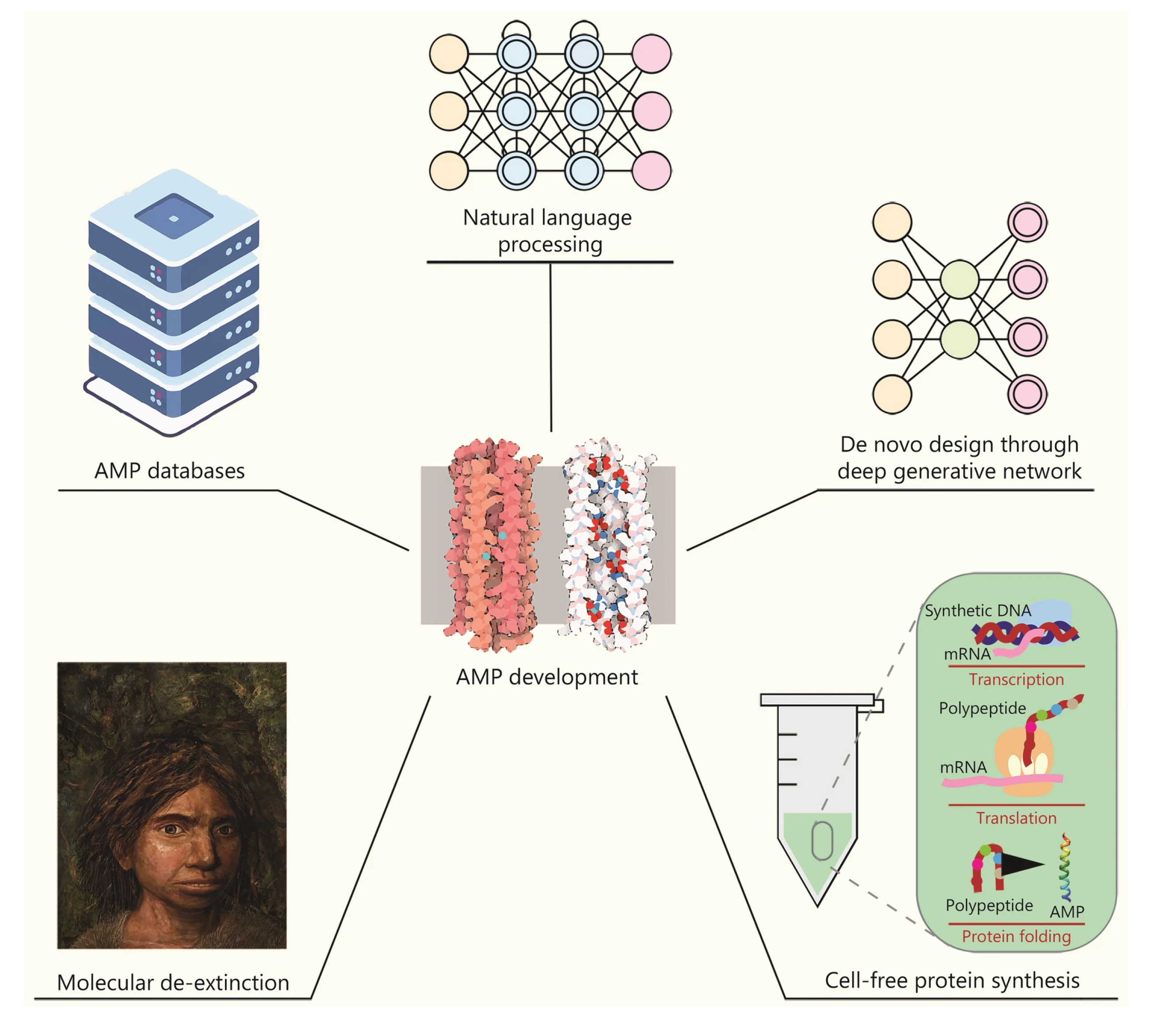

Figure 9.

Artificial intelligence plays a significant role in antimicrobial peptide (AMP) development. AMP databases allow AI models (e.g., NLP, generative networks) to scan a wide range of protein sequences. High-throughput methods such as cell-free synthesis also accelerate the validation of candidate AMPs.[14]

Figure 9.

Artificial intelligence plays a significant role in antimicrobial peptide (AMP) development. AMP databases allow AI models (e.g., NLP, generative networks) to scan a wide range of protein sequences. High-throughput methods such as cell-free synthesis also accelerate the validation of candidate AMPs.[14]

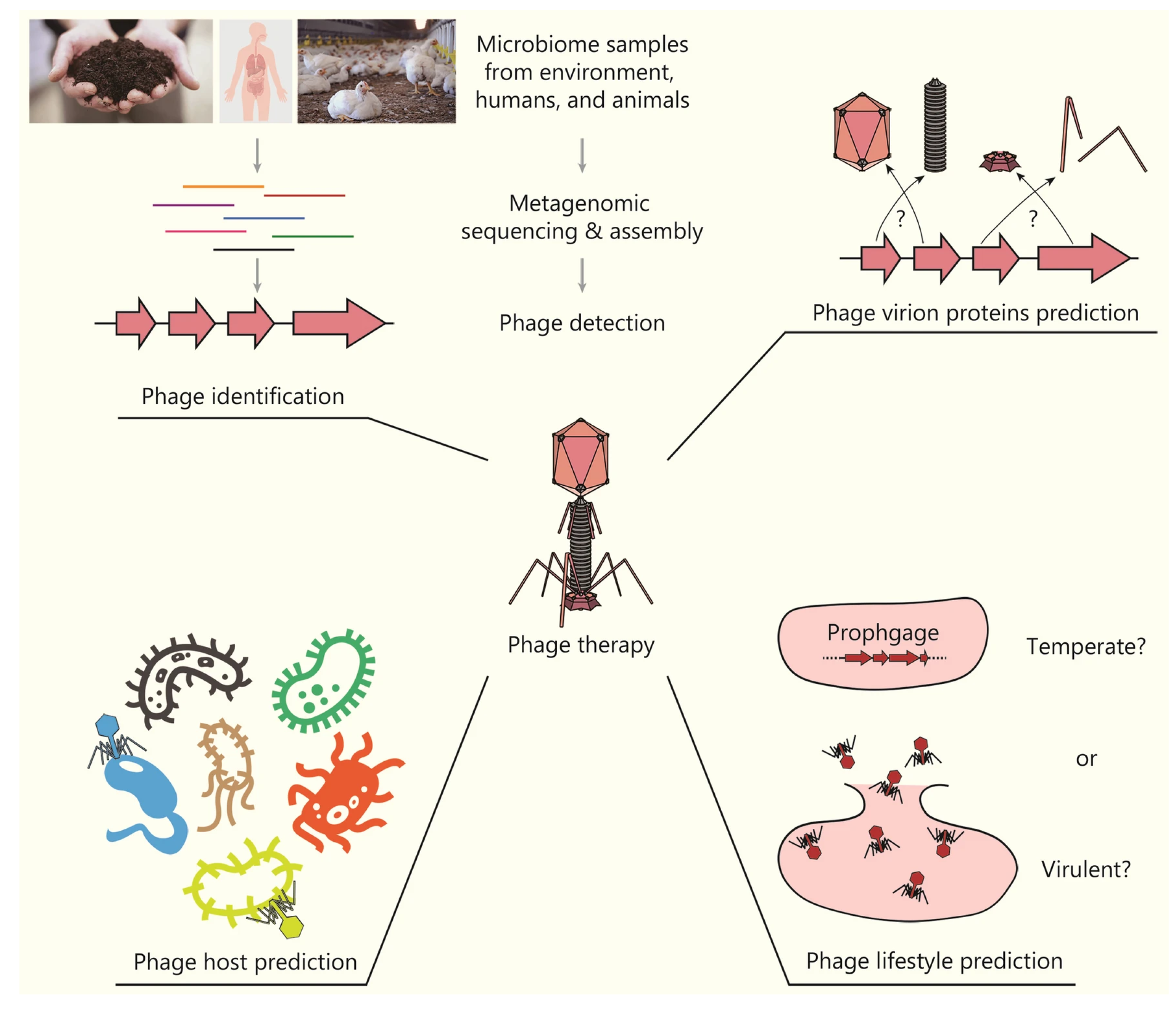

Figure 10.

In the development of phage therapies, artificial intelligence plays an important role in identifying phages from metagenomic samples, predicting phage proteins and hosts, and determining their lifestyles, thus providing the basis for new therapies.[14]

Figure 10.

In the development of phage therapies, artificial intelligence plays an important role in identifying phages from metagenomic samples, predicting phage proteins and hosts, and determining their lifestyles, thus providing the basis for new therapies.[14]

3.3. Challenges and Future Perspectives of Microbiology AI

The most significant factor limiting AI applications in microbiology is the lack of in vivo and clinical data, coupled with data heterogeneity. The discrepancy between controlled data generated in vitro and real-world (in vivo/clinical) sets poses a significant obstacle to transitioning to clinical applications in antimicrobial discovery. While current AI in vitro designs demonstrate good success in antimicrobial discovery, this data falls short of predicting drug uptake and distribution behavior in the human body. To overcome the current situation and increase the ultimate success rate, next-generation AI architectures, enhanced with more competent preclinical models and real-world evidence, that excel at processing sparse and heterogeneous datasets are needed. Another significant limitation in microbiology data sharing stems from data accessibility and privacy concerns. Because providing accurate diagnostic and accurate data in clinical and environmental samples is subject to sensitive ethical considerations, privacy-conscious collaborative learning strategies such as federated learning, active learning, and swarm learning are promising approaches that support performance improvements by exposing learning examples from sample to sample, eliminating the need for a multi-center data repository. Geographic differences and research biases between laboratory devices and data obtained per person from multiple omics platforms affect data sharing, leading to the reproduction of results in certain parallels and which reduces the decisiveness of the results.

Another critical structural issue concerns the interpretability and clinical reliability of AI models. Because clinicians cannot confidently use the results of so-called “black box” models when they fail to reveal the background of their decisions, explainable AI (XAI), model lifecycle management, and “living verification”—that is, continuous post-market surveillance and validation—strategies are essential for both regulators and clinical practice. High accuracy is not enough to establish confidence in clinical adoption; a traceable decision chain and appropriate validation protocols are also essential. Microbiological diversity—the diversity of species, strains, and resistance mechanisms—limits the ability of a single model to perform adequately across all pathogens and resistance phenotypes. Model performance can degrade rapidly when not built on a balanced dataset, particularly for rare pathogens or rare resistance combinations; therefore, multitask learning, species-specific fine-tuning approaches, and expanded reference databases are essential. Moreover, although the high-dimensional structure of microbiome data, i.e., multiple omics layers, provides opportunities for AI, it also increases the complexities and challenges in data preprocessing, feature extraction, and biological interpretation.

At the operational level, integration into existing hospital and laboratory workflows (LIS, RPA, user interfaces) and "last-mile" adoption challenges persist. Successful integration requires a holistic strategy encompassing not only technical compatibility but also staff training, change management, interoperability standards, and interdisciplinary team coordination. In this context, coordinated efforts among policymakers, technology developers, and clinical staff should be a priority for safe, effective, and sustainable implementation.

3.4. Microbiology and AI Conclusion

Artificial intelligence has become a very promising tool for microbial studies, reducing diagnostic time, increasing accuracy, and generating meaningful biological insights based on molecular and omics data. Image-based and omics-based approaches are providing significant advances in pathogen detection, microbiome studies, and antimicrobial research. However, it is important to remember that the resulting data are tightly linked to the source, various characteristics of the data composition, and iterations of preprocessing steps. To achieve true clinical benefit, findings must be continuously updated through prospective validation. From an application perspective, (1) in early-stage research and drug development, AI offers advantages in compound screening and target modeling, while (2) a clinical-grade AI solution can only produce independent and reliable results if thorough validation, explainability, and continuous monitoring are provided. Standardization, rigorous validation protocols, user training, and continuous monitoring are critical for transitioning to the clinical phase.

The framework recommendations can be grouped under four concrete headings:

Reference datasets should be designed to be open and shareable, and multi-site standards should be adopted collaboratively.

Explainable AI and validation: AI models should be supported by continuous validation strategies and transparency of results should be ensured.

Data sharing and federative learning: Data should be shared while being protected, and network models designed around federative learning logic should be used.

Interdisciplinary and ethical roadmaps: Teams from different disciplines should be involved at each stage, and processes should be progressed with a simultaneous, structured and ethical approach.

These recommendations support the effective use of micro-interpretation data while ensuring that data protection, standards, and sharing issues can be addressed in practical applications. Furthermore, explainable AI has led to significant advances in patient recommendations, development, and community responses.

4. Comparative Analysis-Result

Artificial intelligence (AI) systems increase diagnostic accuracy, shorten processing times, and minimize human-related errors in both laboratory types. For example, integrated systems in biochemistry and microbiology laboratories, resulting from the development of AI, reduce error proneness, significantly shorten processing times, and increase clinical accuracy. This advancement also advances laboratory automation, automating routine analyses and minimizing human error. Furthermore, in both fields, data mining and machine learning are extracting crucial insights from biological and process data, such as early diagnosis, risk prediction, and prognosis. For example, the clinlabomics approach transforms conventional blood tests into strategic information sources that provide extraordinary insights. Furthermore, in microbiology, AI-assisted microscopic imaging and omics analysis are increasing diagnostic speed and ensuring accuracy.

Biochemistry: AI, combined with machine learning and deep learning algorithms, is used in the analysis of biochemical parameters in blood and body fluids in areas such as early diagnosis, risk estimation (e.g., diabetes or cancer risk), and prognosis. For example, simple laboratory tests can estimate smoking habits or aging rates, and the presence of COVID-19 or various cancers can be predicted from blood tests. Furthermore, automation of laboratory management, such as the detection of mislabeled samples, the separation of clotted serum, and the automatic determination of reference intervals, are also applications of AI in biochemistry. Technologies used include decision trees, support vector machines (SVM), logistic regression, artificial neural networks (ANN, DNN), and big data analytics.

Microbiology: In pathogen detection, culture analysis, and microbiome studies, AI combines image processing, deep learning, and bioinformatics techniques. For example, a system equipped with lensless holographic microscopy can use deep neural networks to detect bacterial growth stages early and determine the presence of pathogens within 12 hours. Such deep learning-enabled platforms significantly reduce testing time and automate live bacterial colony counting, eliminating the need for expert assistance. In multi-omics applications such as microbiome and virome analysis, AI is also being used to process genetic sequencing data, classify unknown microorganisms, and model ecosystem interactions. AI-based approaches also play an active role in antibiotic discovery and resistance detection, and classify bacterial/virus species. Technologies used include image classification using convolutional neural networks (CNNs), machine learning algorithms for sequence data, and large-scale bioinformatics tools.

4.1. Common and Domain-Specific Challenges

Common challenges in AI applications across both fields include: data privacy and security, as sensitive patient data must be protected; regulatory compliance, ensuring AI-based diagnostics comply with standards such as FDA and EU standards; AI interpretability (the black box problem); and system integration, i.e., adapting to existing hospital-laboratory workflows. Clinical biochemistry also faces ethical, technical, and educational hurdles, requiring software/hardware infrastructure updates and training for laboratory personnel. In microbiology, data heterogeneity is paramount: the discrepancy between controlled data obtained in vitro and real-world clinical data hinders antibiotic discovery and resistance studies. Microbiology also faces specific challenges, such as the diversity of microorganisms (various species and strains), the imbalance in resistance combinations, and the high volume of multilayered omics data. In both fields, the challenge of "last-mile" integration is significant; even the best AI solutions cannot reach their full potential if they cannot adapt to the complex healthcare ecosystem.

4.2. Solutions and Recommendations

The recommendations to address these challenges are as follows: Collaboration for data sharing and confidentiality: Federated learning and similar methods can be used to share data across centers, allowing models to be developed while maintaining patient data confidentiality. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) and continuous validation: Decision-making processes for AI models should be made transparent, and continuous post-launch monitoring and validation should be conducted. Standardized datasets and protocols: Open, shared reference datasets should be created, and multi-center standards should be jointly established. Interdisciplinary collaboration: Teams of engineers, physicians, ethicists, and regulators should be established, and user-friendly interfaces and interoperability standards should be developed. Furthermore, AI training for laboratory personnel and change management strategies for the compatibility of algorithms with healthcare IT infrastructure are gaining importance.

4.3. Future Strategies in Biochemistry and Microbiology

In the future, AI applications in biochemistry and microbiology laboratories will become even more widespread. Large-scale multicenter data repositories and standardized clinical omics data sources will be developed. The use of explainable and validated AI systems in clinical diagnosis will increase, enabling early disease prediction and personalized treatment plans through predictive analytics. In microbiology, analyses supported by federative learning, in particular, will deepen their understanding of microorganism pathogens and resistance profiles; AI systems will rapidly play a role in the discovery of new antibiotics and biological agents. User-friendly design and interoperability will be prioritized, and AI-supported laboratory information systems, robotic automation, and remote work solutions will be integrated. These developments will accelerate and increase diagnostic processes in laboratories, while also significantly improving efficiency and patient safety in healthcare.

References

- Esteva A, et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nature Medicine. 2019;25(1):24–29. [CrossRef]

- Greenspan H, van Ginneken B, Summers RM. Deep learning in medical imaging: overview and future promise of an exciting new technique. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2016;35(5):1153–1159. [CrossRef]

- Jha S, Topol EJ. Adapting to artificial intelligence. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2353–2354. [CrossRef]

- Jiang F, Jiang Y, Zhi H, Dong Y, Li H, Ma S, et al. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: past, present and future. Stroke and Vascular Neurology. 2017;2(4):230–243. [CrossRef]

- Nelson DL, Cox MM. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. 8th ed. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 2021.

- Jin B, Liu H, Zhang Y, Guo T, Liu Y. Clinlabomics: leveraging clinical laboratory data by data mining and machine learning. BMC Bioinformatics. 2022;23(1):116. [CrossRef]

- Gupta P, Ali I, Awasthi A, Bhardwaj S, Shankhdhar PK, Gangwar V, Kumar A. The role of artificial intelligence in clinical biochemistry: a systematic review. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Research. 2025;5(2):45–58.

- Smith KP, et al. Applications of artificial intelligence in clinical microbiology diagnostic testing. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 2020;42(8):61–70. [CrossRef]

- Iadanza E, et al. Gut microbiota and artificial intelligence approaches: a scoping review. Health and Technology. 2020;10:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Koydemir HC, Qiu Y, Bai B, Zhang Y, Jin Y, et al. Early-detection and classification of live bacteria using time-lapse coherent imaging and deep learning. Light: Science & Applications. 2020;9:118. [CrossRef]

- Quince C, Walker AW, Simpson JT, Loman NJ, Segata N. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nature Biotechnology. 2017;35(9):833–844. [CrossRef]

- Lescure FX, et al. GPT-4-based AI agents—the new expert system for detection of antimicrobial resistance mechanisms? Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2024;62(11):e00689-24. [CrossRef]

- Liu G, Catacutan DB, Rathod K, Swanson K, Jin W, Mohammed JC, et al. Deep learning-guided discovery of an antibiotic targeting Acinetobacter baumannii. Nature Chemical Biology. 2023;19(11):1342–1350. [CrossRef]

- Liu GY, Yu D, Fan MM, Zhang X, Jin ZY, Tang C, et al. Antimicrobial resistance crisis: could artificial intelligence be the solution? Military Medical Research. 2024;11:7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).