1. Introduction

Machine learning (ML), a subset of artificial intelligence (AI), has rapidly transformed diverse sectors, including healthcare, by enabling systems to learn from data, identify patterns, and make decisions with minimal human intervention [

1,

2]. In clinical settings, ML-based clinical decision support systems (CDSS) are increasingly used to aid in diagnosis, treatment planning, and antimicrobial stewardship [

3,

4,

5]. A critical element in the deployment of these ML models is the rigorous validation process, which ensures the model’s reliability, generalizability, and accuracy when presented with new and complex data. This process is important, as models trained on limited data can overfit, capturing noise rather than relevant patterns, leading to poor performance when exposed to new data [

6]. Furthermore, a lack of structured data review processes in some ML systems raises concerns about the accuracy of their recommendations, particularly in healthcare settings where critical variables might not be included in the analysis [

7].

The potential of ML-driven CDSS to improve patient care and public health is considerable, yet there are significant barriers to widespread adoption; one of these is the lack of comprehensive validation techniques [

8] and confidence in an accurate working model. As previous attempts to implement ML-based systems in healthcare have shown, challenges such as poor data integration, concerns about data privacy, limited clinical applicability, and inaccurate recommendations have led to the discontinuation of various clinical support systems such as IBM Watson for Oncology [

9,

10,

11] and DeepMind Health’s Streams [

12,

13,

14]. These experiences highlight the need for robust, ethical, and clinically focused validation approaches to ensure the safe and effective integration of ML into clinical practice [

15]. In addition, due to the rapid pace of evolving technology, formal validation methods are lacking, with limited data on the ideal validation process and evidence that ML processes are accurate [

16]. Lastly, because of the uniqueness of the ML model in this study, to our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating its capabilities and its validation methods. Therefore, it is essential, we examine and test the capabilities of this system [

17,

18].

Arkstone, a biotechnology company, has developed a unique ML model for real-time, patient-specific infectious disease guidance integrated with laboratory results. This system provides clinicians with actionable recommendations aligned with clinical guidelines, intending to improve antimicrobial stewardship and reduce antibiotic overuse.

This study aimed to internally validate the system by evaluating its performance in training data and the system’s ability to recall the trained data and distinguish it from new data accurately. By analyzing the ML model, the integration of these tools into clinical practice can be done confidently. In addition, this study will evaluate the model’s robustness, accuracy, and generalizability for clinical use across diverse settings by evaluating the accuracy of the clinical recommendations themselves, which requires human input (human-in-the-loop (HITL) machine learning). This study aims to provide evidence to support the use of similar tools that enhance infectious disease knowledge and antimicrobial stewardship, particularly in resource-limited environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Description

Data entered the ML model occurs via results sent by laboratories. This is typically done in real-time via an HL7 or API interface but can also be done through manual uploads. Data sent includes patient demographics, laboratory findings (organisms, antibiotic susceptibility, and resistance genes), sample sources, diagnostic codes, allergies, and pregnancy status. Within seconds to minutes, a concise, single-page PDF that provides recommendations on the appropriate antimicrobial, if applicable (

Supplement 1).

For scalable and effective processing of data, a unique machine-learning model was developed that incorporates multiple validation techniques simultaneously, including applied K-Fold cross-validation, random subsampling, and holdout validation. The combination of methods, also called Antimicrobial Intelligence, is applied in real-time (prospective validation), leveraging live data streams. A key component of this is the system’s inability to suggest new treatment options as well as to provide recommendations to untrained data sets. The system, therefore, relies on HITL processes on multiple levels to ensure the data is trained accurately. This step is critical at every stage of data training, ensuring that expert oversight is consistently applied. In addition to requiring human approval to train data, HITL is required and repeated by different infectious disease experts to ensure consistency and accuracy on how the data is trained, minimizing the risk of human error and bias. Furthermore, once the data is finally trained by multiple infectious disease experts, it does not stay in this status indefinitely. Data that has been rigorously trained previously gets pushed back into a status requiring it to be trained again, ensuring that data is repeatedly and periodically retrained so that information is up-to-date and error-free. This also allows for updates to medical recommendations that may have changed since initial training. This hybrid model that incorporates both human oversight and set algorithms ensures its adaptability to new and ever-evolving data.

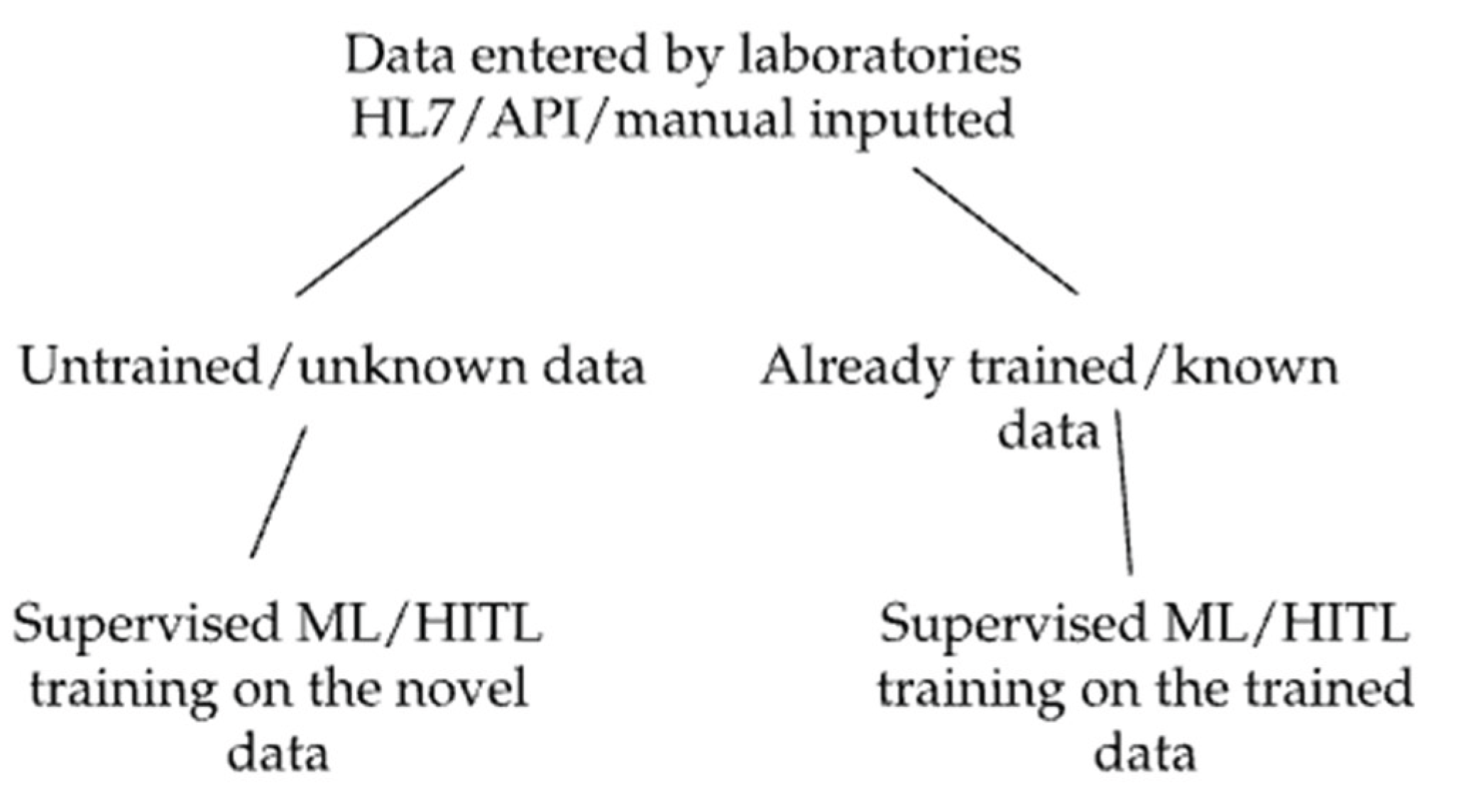

The validation process is divided into three key elements that will be evaluated separately: 1) Evaluation of the system’s ability to distinguish and recall trained from new single data points; 2) Evaluation of the system’s ability to distinguish and recall trained from new complex data sets; (

Figure 1) and 3) Evaluation of the accuracy of the clinical recommendations outputted by the system.

2.2. Data Sources and Preparation

Data were obtained from the Arkstone laboratory results database. The data set included positive and negative microbiology results, as well as demographic data such as patient age and sex, ICD-10-CM codes, allergies, pregnancy status, source of specimen, organism, sensitivity information, and resistance gene information. Diagnostic modalities included molecular or standard culture techniques. Prior to analysis, all data were de-identified according to HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) guidelines. Data were pre-processed to ensure consistency in format and coding.

2.3. Study Design

This validation study consisted of two components: a prospective observational phase and a retrospective analysis of real-world data from Arkstone’s database. The study was conducted in three sequential phases, each designed to evaluate different aspects of the machine learning system’s clinical performance. The research team accessed the dataset remotely from their respective locations, without intervening in clinical care or altering the existing workflow of the system. Researchers reviewing reports were not the same individuals involved in formulating the initial clinical recommendations to avoid confirmation bias.

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the internal validation process of the machine learning (ML) model through three critical components: a) Recognition of novel versus trained data: This component assessed the model’s ability to distinguish between previously unseen (untrained) data and data used during the model’s training process; b) Recognition of complex datasets: This involved evaluating the system’s performance when classifying large and heterogeneous datasets composed of multiple data points from various sources; and c) Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) component: This assessed the accuracy of treatment recommendations generated by the system which requires human input via the HITL process.

2.4. Ethical Considerations and Data Availability

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Private University of Tacna (FACSA-CEI/224-12-2024). All procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and HIPAA guidelines. The study involved no risk to patients, and informed consent was not required, as all data were either retrospective, anonymized, or publicly available. The dataset consisted of publicly accessible BioFire panel results and fully de-identified internal laboratory submissions. No protected health information (PHI) was accessed or disclosed (Supplement 2).

2.5. Procedures

2.5.1. Element 1: Evaluation of the System’s Ability to Distinguish and Recall Trained from New Single Data Points

Element 1 involved a retrospective observational approach to evaluate the system’s ability to generate accurate recommendations based on individual data points, using multiple validation techniques. New data, also known as untrained data, refers to information the system has not previously encountered. Recognizing untrained data and subsequently training the system to identify it in future encounters are critical. Data imputed into the system was sourced from FDA-approved molecular diagnostic BioFire panels published on the BioFire website (

https://www.biofiredx.com/products/the-filmarray-panels/). Panels do not contain any patient information and contain data regarding the type of panel, source of specimen, organism targets, and resistance gene targets. This was to ensure standardized nomenclature of panel types, organisms, and resistance genes. The new data encompassed six different standardized infectious disease panels (

Table 1). The data were selected based on the fact that these panels are among the few FDA-approved comprehensive molecular panels currently available. Additionally, the microbes and resistance markers tested by these panels are considered industry standard. Panel information was uploaded into the system and accessed remotely, from Boca Raton, and repeatedly analyzed on subsequent days.

To ensure the system recognized the uploaded data as novel and untrained, each data point was enclosed in brackets. The dataset was then collectively input into the system (

Table 2), which successfully identified it as entirely new, as bracketed data is never present in the system’s training inputs before. This approach helps prevent overfitting and bias and avoids introducing data already known to the model. Once the data was established as new and untrained, the data was then categorized according to each panel (

Table 2) as designed by the panel manufacturer and entered into the system again. Here, too, the system identified all the variables entered into the system correctly as untrained data. This was expected since training did not occur between training sessions 1 and 2.

The panels were then randomized, and the data were split multiple times to form new data sets containing unique random variables (random subsampling). These new data sets were distributed into six groups: five of these groups became the folds for K-fold cross-validation (

Table 2), and the sixth data set was used for holdout validation (

Table 3). After training on one-fold, the data sets from all six panels were re-entered into the system for analysis (

Table 2). Once all the sets were analyzed, all the data were again introduced back into the system in its entirety for evaluation (

Table 2).

2.5.2. Element 2: Evaluation of the System’s Ability to Distinguish and Recall Trained from New Complex Datasets

An anonymous retrospective analysis was conducted using internal data imputed by various laboratories containing infectious disease results. Data within each lab result includes many variables sent by the lab, such as patient demographics, allergies, organisms, resistance genes, pregnancy status, diagnostic codes, and more. The research team accessed the data remotely from their respective locations. These results were randomly selected by choosing a random 24-hour period (all results from Thursday, August 1, 2024, were used).

Patient-specific information was locked to the researchers and was inaccessible. A team of researchers was tasked with manually reviewing each laboratory result and evaluating the accuracy of how the system classified it (trained or untrained). The assigned researcher was not involved in the initial training of the data to avoid biases.

Data is considered untrained by the system if either a single variable is new or if a dataset has a new combination of trained data (regardless of whether the individual data points have been trained). Fully trained data sets require not only each data point within the dataset to be trained but also require multiple rounds of HITL training for the entire data set combination. This means that the system must see the same combination of data points multiple times before it is considered trained by the system (

Table 4).

2.5.3. Element 3: Evaluation of Human in-the-Loop Component and the Accuracy of Clinical Recommendations

A prospective evaluation of recommendations generated by human-enhanced (HITL) models during the training process was conducted. The primary objective was to determine whether errors occurred during the HITL intervention that could have resulted in inaccurate clinical recommendations. To assess this, a team of independent researchers with expertise in infectious diseases reviewed the system’s output. Each recommendation was compared to established clinical guidelines and evaluated using a structured six-question questionnaire:

- -

Were the microbes being treated as pathogens accurately identified?

- -

Does the antibiotic recommended in OneChoice have activity against the microbe that is presumed to be the pathogen?

- -

Was the recommended dose accurate?

- -

Was the recommended duration of treatment accurate?

- -

Was the preferred therapy the optimal therapy?

- -

Were there organisms that should have been addressed but were not?

Based on their responses, reviewers categorized discrepancies in HITL-trained outputs as either major or minor: a) Major discrepancies: Failure to identify a pathogen that required treatment or recommending antibiotics that were ineffective against the identified microbe(s); b) Minor discrepancies: Incorrect antibiotic dosage or treatment duration (outside FDA or guideline-based ranges), a suboptimal choice when a better preferred or alternative therapy was available. This review process aimed to ensure the integrity of HITL-influenced recommendations and identify opportunities for further refinement of the system.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using the STATA 17 statistical package.

For element 1: evaluating the system’s ability to distinguish between trained vs. untrained data the following metrics were calculated: a) Accuracy: proportion of data points correctly classified as trained or untrained; b) Precision: proportion of instances that were correctly identified as trained data; c) Recall: ability of the trained model to correctly identify previously trained data points; and d) F1 Score: the harmonic meaning of precision and recall

For element 2: evaluating the system’s ability to distinguish between trained vs untrained complex data sets, the following metrics were calculated: a) True Positive Rate (TPR): proportion of fully trained data sets correctly identified; b) True negative rate (TNR): proportion of untrained datasets correctly identified; c) False positive rate (FPR): proportion of untrained datasets incorrectly classified as trained; And d) False negative rate (FNR): proportion of fully trained datasets incorrectly classified as untrained.

For element 3: evaluating the accuracy of HITL in in providing accurate clinical recommendations, the percentage of reports with major and minor discrepancies was calculated. All statistical tests were performed at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Element 1: Evaluation of the System’s Ability to Distinguish and Recall Trained from New Single Data Points

From the six panels (

Table 1), there were initially 192 data points. However, after removing duplicate variables that spanned across multiple panels, 111 unique variables remained. Each panel was fully input into the system. Since this was novel data, the system correctly identified all these variables as new (

Table 2).

The proportion of true positive results (correctly identified as trained) to the total predicted positives (all instances predicted as trained) is a measure of precision. (

Table 5). The proportion of true positives to the total actual positives (all actual trained data points) is a measure of recall. This is collectively assessed using the F1 score.

The proportion of true positive results (i.e., correctly identified as trained) relative to the total number of instances predicted as trained represents the system’s precision (

Table 6). Similarly, the ratio of true positives to all actual trained data points reflects the system’s recall. Together, these metrics demonstrate the system’s flawless performance in accurately distinguishing between trained and untrained data under the evaluated conditions.

3.2. Element 2: Evaluation of the System’s Ability to Distinguish and Recall Trained from New Complex Data Sets

A total of 1,401 real laboratory results were analyzed from the systems database (

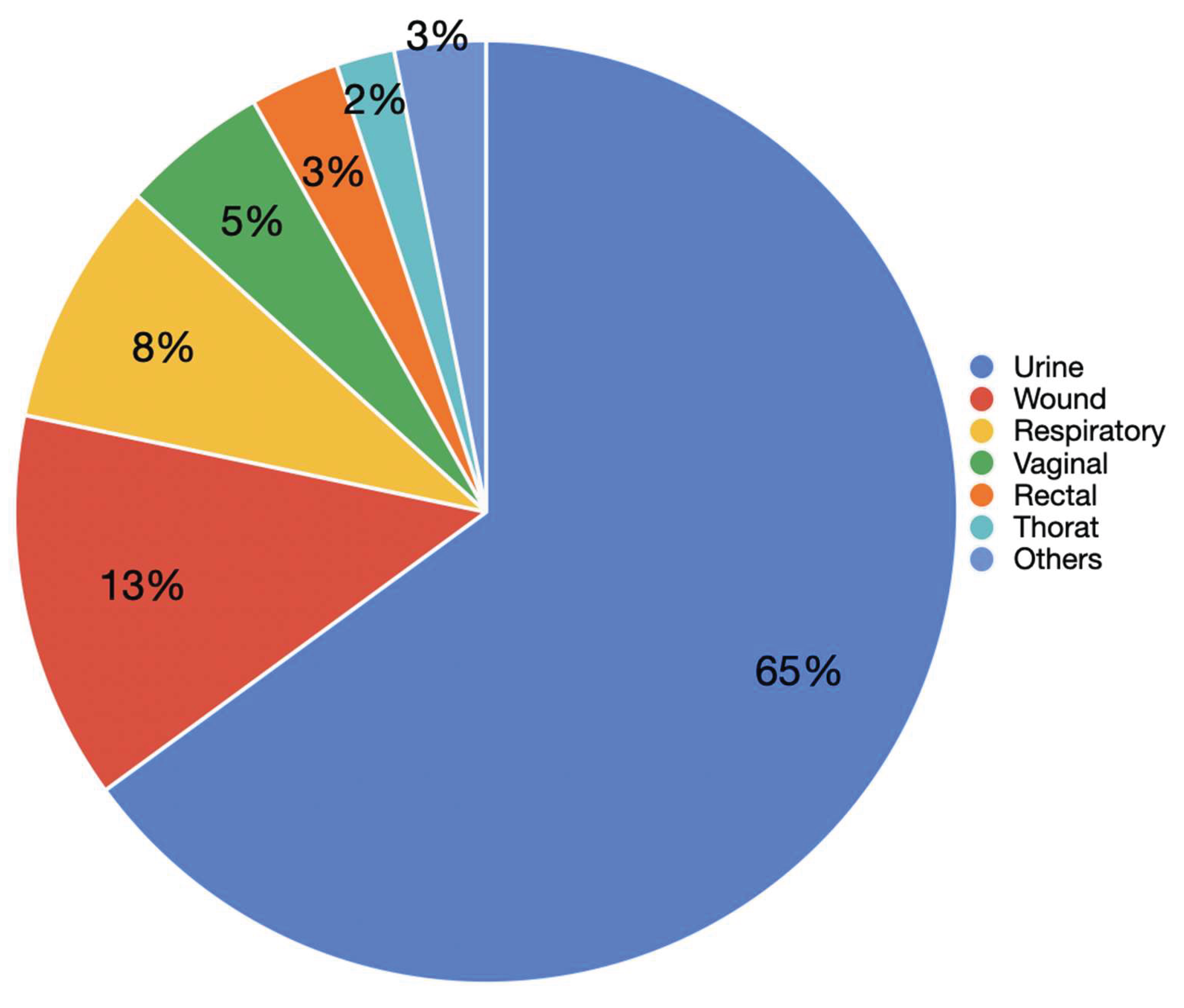

Supplement 2). These results were randomly selected by choosing a 24-hour period at random. The dataset was diverse, encompassing results from 66 laboratories located in 55 different regions across 24 states and one international site. This data included: 176 specified provider locations (12%), 936 unspecified practice locations (62%), 198 specified facility locations (13%), and 200 non specified facility locations (13%). A total of 65% of the clinical samples analyzed were urine specimens, representing the most frequent sample type. This was followed by wound (13%), respiratory (8%), and vaginal samples (5%). Other less frequent sources included rectal (3%), throat (2%), nail (2%), oral (1%), urogenital, epidermal, and unknown sources (all <1%) (

Figure 2).

Among the 1,401 results analyzed, 238 (16.98%) were confirmed as negative results and 1163 (83.02%) as positive. Of the positive results, 519 (44.62%) were identified by the system as fully trained, while 644 (55.38%) reports required training (untrained). This classification was verified through manual review, verifying the system’s ability to accurately distinguish between trained and untrained datasets. The system’s classification performance was evaluated using the full set of 1,401 reports. Using 238 true negatives and 519 true positives, the F1 Score and related performance metrics were calculated as follows (

Table 7).

Performance Metrics:

- -

Precision: TP / (TP + FP) = 519 / (519 + 0) = 1.0 (100%)

- -

Recall: TP / (TP + FN) = 519 / (519 + 0) = 1.0 (100%)

These results indicate that the system achieved perfect accuracy in distinguishing between fully trained and untrained datasets under real-world conditions.

3.3. Element 3. Evaluation of the HITL Component in the Accuracy of Clinical Recommendations

Among the 1,401 results analyzed, 238 (16.98%) were confirmed as negative and 1,163 (83.02%) as positive. Of the positive results, 519 (44.62%) corresponded to fully trained data (Table 11). Additionally, 233 (20.03%) had been trained once but required further reinforcement. Specifically, 164 cases (14.10%) required one additional training session, 61 (5.24%) required two sessions, 7 (0.60%) required three, and 1 case (0.09%) required four sessions. A total of 267 cases (22.95%) were classified as partially untrained, defined as datasets with greater than 90% similarity to data previously seen by the system. Among these, 186 (15.99%) required two training sessions, 41 (3.52%) required three, 19 (1.63%) required four, and five cases each (0.43%) required five or six sessions, respectively. In contrast, 97 cases (8.34%) were classified as completely untrained, having less than 90% similarity to any known dataset. These required more intensive training: 63 cases (5.42%) required two sessions, 15 (1.29%) required three, 12 (1.03%) required four, four (0.34%) required five, two (0.17%) required six, and one case (0.09%) required seven sessions. (

Table 8)

Of the 644 reports that required training, all were reviewed by a clinical team with expertise in infectious disease. According to the consensus of the reviewers, no major discrepancies were identified. Minor discrepancies were observed in 100 (15.52%) of the 644 reports. Specifically, 11 (1.71%) reports involved the system recommending a different antibiotic than what was typically preferred; 36 (5.59%) reports suggested that an alternative antibiotic or combination could have been considered; 34 (5.28%) reports included recommendations where the dose or administration interval lacked formal FDA approval or varied across clinical references; and 20 (3.11%) reports did not address organisms of questionable pathogenicity (

Table 9). Overall, these findings indicate a high level of consistency between the system’s recommendations and accepted clinical standards, with only minor variations that reflect the complexity and nuance of clinical decision-making.

4. Discussion

This study provides a robust assessment of the internal validation of this novel ML system, demonstrating its ability to accurately differentiate between trained and untrained data, both at the level of individual data points and in complex data sets. To our knowledge, this is the only system currently deploying such validation techniques.

It is important to note that once a data point is trained on the system, it remains trained even if it appears in larger data sets. This eliminates the need to retrain the system on the same data point in subsequent data sets. Furthermore, unlike traditional K-fold cross-validation, where training occurs on all but one fold, in this study, the data was trained on a single fold and tested against the other untrained folds. This approach was necessary due to the large volume of data and the nature of the system: once a data point is trained, it cannot be untrained. This method was more efficient and effective in terms of time, allowing for more training sessions within the constraints of the system.

The system shows high accuracy in recognizing new data by distinguishing untrained from trained individual data points using multiple validation techniques (K-fold cross-validation, random subsampling, and holdout validation). As well as accurately classifying complex data sets, with over 1000 real-world laboratory data from diverse sources, which highlights its ability to generalize and avoid overfitting to the training data. Also, the diversity of real-world data with data from 66 laboratories in 55 regions, across multiple states, and one international location ensures the system’s adaptability to diverse clinical settings and reduces the possibility of bias [

19].

The use of multiple validation techniques (K-fold cross-validation, random subsampling, and holdout validation) in the study mitigates the risks of overfitting and improves the generalizability of the model [

7,

20]. In the system studied, the HITL component for multi-stage data training enables the participation of clinical experts, prevents error propagation, and ensures compliance with current medical guidelines [

4]. This is a key strength, particularly in the context of high-stakes clinical decision-making [

21,

22].

The critical importance of HITL validation is highlighted by the detection of 100 minor discrepancies out of 644 reviewed reports. This finding reinforces that, although ML algorithms are powerful tools capable of processing large volumes of data and identifying patterns, the nuanced clinical judgment of infectious disease specialists remains essential to ensure patient safety and optimize treatment strategies [

3,

23]. The nature of these discrepancies is particularly telling: while the automated system excels at data analysis, it lacks the ability to account for complex clinical subtleties and evolving scientific insights. For instance, the system relies on external references, such as FDA guidelines or published literature, for dosing and administration intervals. Although generally accurate, these references may not always reflect the most current evidence or account for patient-specific factors, which clinicians are uniquely positioned to evaluate. Additionally, the system provides generalized recommendations and is not designed to handle rare or atypical clinical scenarios, further emphasizing the necessity of expert oversight. These results suggest that the HITL process successfully mitigated potential errors or suboptimal recommendations, underscoring the vital role of human oversight in AI-supported clinical care [

22,

24]. This is especially significant in the realm of antimicrobial stewardship, where inappropriate antibiotic prescribing can contribute to the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance [

22,

25].

The methodology and findings of the study can be contrasted with previous attempts to validate ML-based CDSS; For example, IBM Watson for Oncology, while initially promising, failed due to inaccurate recommendations and integration challenges, ultimately leading to its discontinuation [

26,

27]. This highlights the crucial need for robust validation processes, as demonstrated in the present study. Mayo Clinic Predictive Analytics: This project faced data complexity and integration issues, which halted its progress [

23]. The Pediatric Alert System employed cross-validation techniques, however, this system suffered from limitations due to data sparsity, which impacted the effectiveness of its model [

28]. The use of large, diverse datasets and HITL helps overcome this.

This study demonstrates a robust validation process, which emphasizes real-time application and human oversight. It also highlights the advantage of having a system that is not intended to be used for “discovery” of new findings, but instead focuses on adhering to existing guidelines and best practices. The system was carefully trained by infectious disease experts and periodically re-evaluated. This method ensures both the accuracy and up-to-date nature of the database and algorithms. The system was designed to assume that error is possible and, therefore, never allows data to be trained indefinitely.

Limitations of this study include that data curation, particularly for complex data sets, was restricted to a single-day period. Although the sample was geographically diverse, limiting the sample to a single day could introduce some bias into the data sample, possibly related to the capabilities of the quality control team on that particular day. Furthermore, while HITL is essential, the manual review process introduces the potential for bias and variability in data interpretation [

7,

29]. Automating some components of the HITL process could improve consistency. Lastly, this study does not evaluate the subsequent impact on patient outcomes and antimicrobial stewardship.

The system’s unique approach to antimicrobial guidance is an innovative system, notable for its reliance on established treatment guidelines and avoidance of novel treatment suggestions, thereby prioritizing safety and adherence to proven practices. To meet these goals, this first study demonstrates that the first two steps of the process work robustly, laying the groundwork to demonstrate that the system works efficiently, and if subsequent steps follow suit, will lead to appropriate and useful recommendations in the real world. This is a preliminary study that focuses primarily on the technical performance of the system in identifying trained versus untrained data, and final results and clinical outcomes are not yet included. Therefore, the impact of the system on patient care and antimicrobial stewardship requires further study.

This study provides valuable insights into the design and validation of ML-based CDSS for antimicrobial stewardship. The combination of robust statistical validation techniques with a comprehensive HITL process represents a promising strategy for ensuring the accuracy and clinical relevance of AI-driven recommendations. The findings suggest that such systems can potentially contribute to improved antimicrobial prescribing practices and, ultimately, better patient outcomes.

Future research should focus on external validation and evaluating the performance of the model in diverse clinical settings and patient populations to assess its generalizability and identify potential biases [

20,31]. In addition, prospective clinical trials through randomized controlled trials to evaluate the impact of the CDSS on antimicrobial use, patient outcomes, and healthcare costs may be of benefit [

4,

22] Lastly, expanding HITL evaluation by collecting more detailed data on the types of discrepancies identified during the HITL process to further refine the model and identify areas where clinician training may be needed. Integrating with Electronic Health Records (EHRs) may facilitate seamless data flow and improve clinician workflow [

22,

26,

30]

By continuing to refine and validate these systems, we can harness the power of AI to support clinicians in making informed decisions about antimicrobial therapy, contributing to the fight against antimicrobial resistance, and improving patient care.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the robust performance of a novel ML model in accurately distinguishing between trained and novel data, achieving 100% accuracy. This result was validated using multiple methodologies, including K-fold cross-validation, random subsampling, and holdout validation. The system also successfully identified complex datasets as either trained or untrained with high reliability. Integrating HITL validation enhanced the model’s adaptability and quality control, reinforcing the value of clinical oversight in AI systems. These findings suggest that advanced ML models can be effectively and consistently trained to support clinical decision support systems (CDSS), helping to bridge key gaps in antimicrobial stewardship. While the system showed excellent performance in identifying data patterns and learning behavior, its clinical decision-making capabilities also demonstrated strong internal validity. Specifically, it achieved 100% accuracy in avoiding major discrepancies and 84% agreement in minor discrepancies when evaluated against clinical standards. This high level of internal validation represents a promising first step toward broader implementation. Future studies should focus on external validation across diverse healthcare settings and evaluate the impact of these AI-driven recommendations on real-world clinical outcomes and patient care.

Ethical Considerations and Data Availability

All data used in this study were either publicly available (BioFire panels) or obtained from internal, de-identified laboratory submissions. No protected health information (PHI) was accessed or disclosed. However, the study was submitted to and approved by an Ethics Committee, and all data were managed per HIPAA guidelines. The processed database will be attached to the paper.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Supplement 1,

Supplement 2.

Author Contributions

(I) Conceptualization: A Frenkel, D Gross, (II) Methodology: D Gross, A Frenkel, M Hueda-Zavaleta (III) Software: D Gross, (IV) Validation: A Frenkel, JC Gomez de la Torre, C Chavez-Lencinas (V) Formal analysis: A Frenkel, A Rendon, C Chavez-Lencinas, J MacDermott, C Gross, S Allman, S. Lundblad, J Siegel, S Choi (VI) Investigación: A Frenkel, D Gross, C Chavez-Lencinas, JC Gomez de la Torre, M Hueda-Zavaleta (VII )Resources A Frenkel, D Gross.: (VIII) Data curation: A Frenkel, JC Gomez de la Torre, C Chavez-Lencinas, A Rendon (IX) Writing - Original draft: A Frenkel, (X)Writing - review & editing: M Hueda-Zavaleta, A Frenkel, C Chavez-Lencinas, JC Gomez de la Torre, M Hueda-Zavaleta (XI) Visualization: (XII)Supervision: A Rendon, J MacDermott, C Gross, S Allman, S. Lundblad, J Siegel, S Choi (XIII)Project administration: I. Zavala (XIV): Funding acquisition: A Frenkel.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this manuscript, as well as its definitions, can be downloaded at the following link: Supplement 2.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the personnel at Arkstone Medical Solutions and Roe Clinical Laboratory, who have actively been working.

Conflicts of Interest

Ari Frenkel is Co-founder and Chief Science Officer of Arkstone Medical Solutions, the company that produces the OneChoice report evaluated in this study. JC Gómez de la Torre works as the Director of Molecular Informatics at Arkstone Medical Solutions and as Medical Director at Roe Lab in Lima, Perú, while Alicia Rendon and Miguel Hueda Zavaleta serve as Quality Assurance Managers at Arkstone Medical Solutions. These affiliations may be perceived as potential conflicts of interest. However, the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation, and the decision to publish the results were conducted independently, with no undue influence from the authors’ affiliations or roles within the company.

Abbreviations

| ML |

Machine learning |

| CDSS |

Clinical decision support systems |

| HITL |

Human involvement in the loop |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ASP |

Antimicrobial stewardship program |

| AMR |

Antimicrobial resistance |

References

- Jordan, M. I. , & Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Russell, S. , & Norvig, P. (2020). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Cabitza, F. , Rasoini, R., & Gensini, G. F. Unintended consequences of machine learning in medicine. JAMA 2017, 318, 517–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mehrabi, N. , Morstatter, F., Saxena, N., Lerman, K., & Galstyan, A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, W. , Wilson, R., Gilchrist, M., Georgiou, P., Holmes, A., & Rawson, T. Personalising intravenous to oral antibiotic switch decision making through fair interpretable machine learning. Nature Communications 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C. M. (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer.

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high-stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nature Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynants, L. , et al. (2020). “Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19: systematic review and critical appraisal.” BMJ.

- Creswell, J. (2019). Google’s DeepMind faces a reckoning in health care. The New York Times.

- Herper, M. (2018). IBM Watson’s Health Struggles Show How Hard It Is to Use AI to Transform Health Care. Forbes.

- Kelion, L. (2019). DeepMind AI achieves Grandmaster status in Starcraft 2. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-50212841.

- McKinney, S. M. (2020). International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening. Nature.

- IBM to sell Watson Health assets to Francisco Partners. Healthcare IT News. Published January 21, 2022. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.healthcareitnewsibm-sell-watson-health-assets-francisco-partners.

- Shickel B, Tighe PJ, Bihorac A, Rashidi P. Deep EHR: A Survey of Recent Advances in Deep Learning Techniques for Electronic Health Record (EHR) Analysis. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2018, 22, 1589–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- cO’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Wellcome Collection; 2016 May 19.

- Sanchez-Martinez S, Camara O, Piella G, et al. Machine learning for clinical decision-making: challenges and opportunities in cardiovascular imaging. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 8, 765693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramgopal S, Lorenz D, Navanandan N, Cotter JM, Shah SS, Ruddy RM, Ambroggio L, Florin TA. Validation of Prediction Models for Pneumonia Among Children in the Emergency Department. Pediatrics. 2022, 150, e2021055641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Calster B, Wynants L, Timmerman D, Steyerberg EW, Collins GS. Predictive analytics in healthcare: how can we know it works? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019, 26, 1651–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinaro, A. M. , Simon, R., & Pfeiffer, R. M. Prediction error estimation: a comparison of resampling methods. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3301–3307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K. P. (2012). Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective. MIT Press.

- Yao, Y. , Rosasco, L., & Caponnetto, A. On early stopping in gradient descent learning. Constructive Approximation 2007, 26, 289–315. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T. , Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction (2nd ed.). Springer.

- James, G. , Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2021). An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R. Springer.Second Edition.

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, J. , Larochelle, H., & Adams, R. P. Practical Bayesian optimization of machine learning algorithms. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2012, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar]

- Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville: Deep learning. The MIT Press, 2016, 800 pp, ISBN, 2016.

- Kohavi, R. , & Provost, F. Glossary of terms. Machine Learning 1998, 30, 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Raschka, S. , & Mirjalili, V. (2019). Python Machine Learning: Machine Learning and Deep Learning with Python, scikit-learn, and TensorFlow (3rd ed.). Packt Publishing.

- David Vázquez-Lema, Eduardo Mosqueira-Rey, Elena Hernández-Pereira, Carlos Fernandez-Lozano, Fernando Seara-Romera, and Jorge Pombo-Otero. 2024. Segmentation, classification and interpretation of breast cancer medical images using human-in-the-loop machine learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 3023–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan H, Kang L, Li Y, Fan Z. Human-in-the-loop machine learning for healthcare: current progress and future opportunities in electronic health records. Med Adv. 2024, 2, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins G S, Dhiman P, Ma J, Schlussel M M, Archer L, Van Calster B et al. Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 1): from development to external validation. BMJ 2024, 384, e074819. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).