1. Introduction

Multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR) are an escalating concern and are considered a priority in public health. They have been linked to severe infections with poor therapeutic outcomes, increased hospital stays, and higher healthcare costs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Intensive Care Units (ICUs) have been identified as major contributors to the emergence of MDR within hospitals, making them key targets for controlling these pathogens [

7]. However, epidemiological surveillance studies have shown that a considerable proportion of patients are already carriers of MDR upon ICU admission, either as an infection or colonization [

8,

9,

10].

In response, the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC), supported by the Ministry of Health, launched the “Resistencia Zero” (RZ) project in 2014. This initiative aimed to reduce the incidence of ICU-acquired infections caused by MDR pathogens by 20%. Secondary objectives included understanding the epidemiology of MDR infections in Spanish ICUs, distinguishing between imported and ICU-acquired MDR cases, promoting and strengthening safety policies within ICUs, and implementing evidence-based safe practices [

11,

12].

RZ project recommendations include active screening for MDR in all patients upon ICU admission and at least weekly thereafter. Contact precaution measures—hand hygiene, disposable gloves and gowns, and, if possible, single-patient rooms—should be applied to patients at high risk of carrying MDR according to a risk factor (RF) checklist. This checklist includes six recognized RFs: recent hospital admission and antibiotic therapy, prior MDR carriage, renal replacement therapy, and certain chronic conditions that increase colonization risk, such as chronic ulcers and cystic fibrosis.

However, as demonstrated in some studies [

8,

9], the sensitivity and specificity of these RFs, recognized in the literature and the RZ checklist, are insufficient to efficiently prevent MDR transmission and guide empirical antibiotic therapy.

The application of machine learning (ML) techniques, using variables present at ICU admission, may provide better risk stratification for MDR carriage. Among ML techniques, we aim to use those with clinical interpretability, an appealing feature for their implementation in clinical settings [

13].

The goal of this study is to determine the risk of MDR carriage at ICU admission based on the RF checklist from the RZ project, using machine learning methodology.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective, observational study conducted at a single center, the Intensive Care Unit of Arnau de Vilanova University Hospital in Lleida (HUAV), a 22-bed multidisciplinary ICU. Data were collected from April 2014 to December 2016, during the implementation of the RZ program in Spain.

Patients included were those admitted to the ICU who underwent active MDR screening through mucosal swabs (nasal, pharyngeal, axillary, rectal) within the first 48 hours, as per RZ recommendations, in addition to diagnostic cultures from clinical samples (blood, urine, sputum, tracheal or bronchoalveolar aspirates, surgical wound swabs, or others) based on medical criteria. Patients under 15 years old and those without microbiological cultures performed were excluded.

Patients and/or their families were informed about the microbiological procedures and preventive isolation policy. The HUAV ethics committee (CEIC-3025) approved the study. The development of the models followed the recommendations from the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) initiative [

14].

The study group was randomly divided into a Development Group (DG) and Validation Group (VG) (70:30). A patient was considered an MDR carrier at admission if any of the surveillance cultures or clinical samples collected within the first 48 hours tested positive for MDR. MDR bacteria included methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus spp. (VRE), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales (ESBL), carbapenemase-producing gram-negative bacteria, multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (resistant to more than three common antibiotic families), and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Other gram-negative bacteria resistant to three or more antibiotic families or producing other resistance mechanisms, such as AMP-C or Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, were classified as “others” [

11,

12].

Variables collected at ICU admission included patient data from the ENVIN-HELICS registry [

15] (available at

http://hws.vhebron.net/envin-helics/): age, sex, diabetes mellitus (DM), acute or chronic renal failure, immunosuppression, previous malignancy, liver cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), malnutrition, and organ transplant. Other data included the source of admission (community, nursing home, other institution, hospital ward, or another ICU), reason for admission (medical, elective surgery, emergency surgery, trauma, or coronary), and whether antibiotic treatment was indicated at ICU admission.

The RZ RFs included hospitalization for more than five days in the last three months, institutionalization, history of MDR carriage, antibiotic therapy for more than seven days in the month before admission, hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, and chronic conditions with a high incidence of colonization/infection by MDR (cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, chronic ulcers, etc.) [

11,

12].

Models were developed in the DG and validated in the VG.

Binary logistic regression (LR) was used for variable selection, including those with a univariable p-value <0.1 in the multivariable model. A stepwise approach selected significant variables, and coefficients were rounded to the nearest integer for a scoring system (simple score).

A decision tree model using CHAID (Chi-square automatic interaction detection) employed cross-validation (five partitions) and a stopping rule with a minimum terminal node size of 10 records.

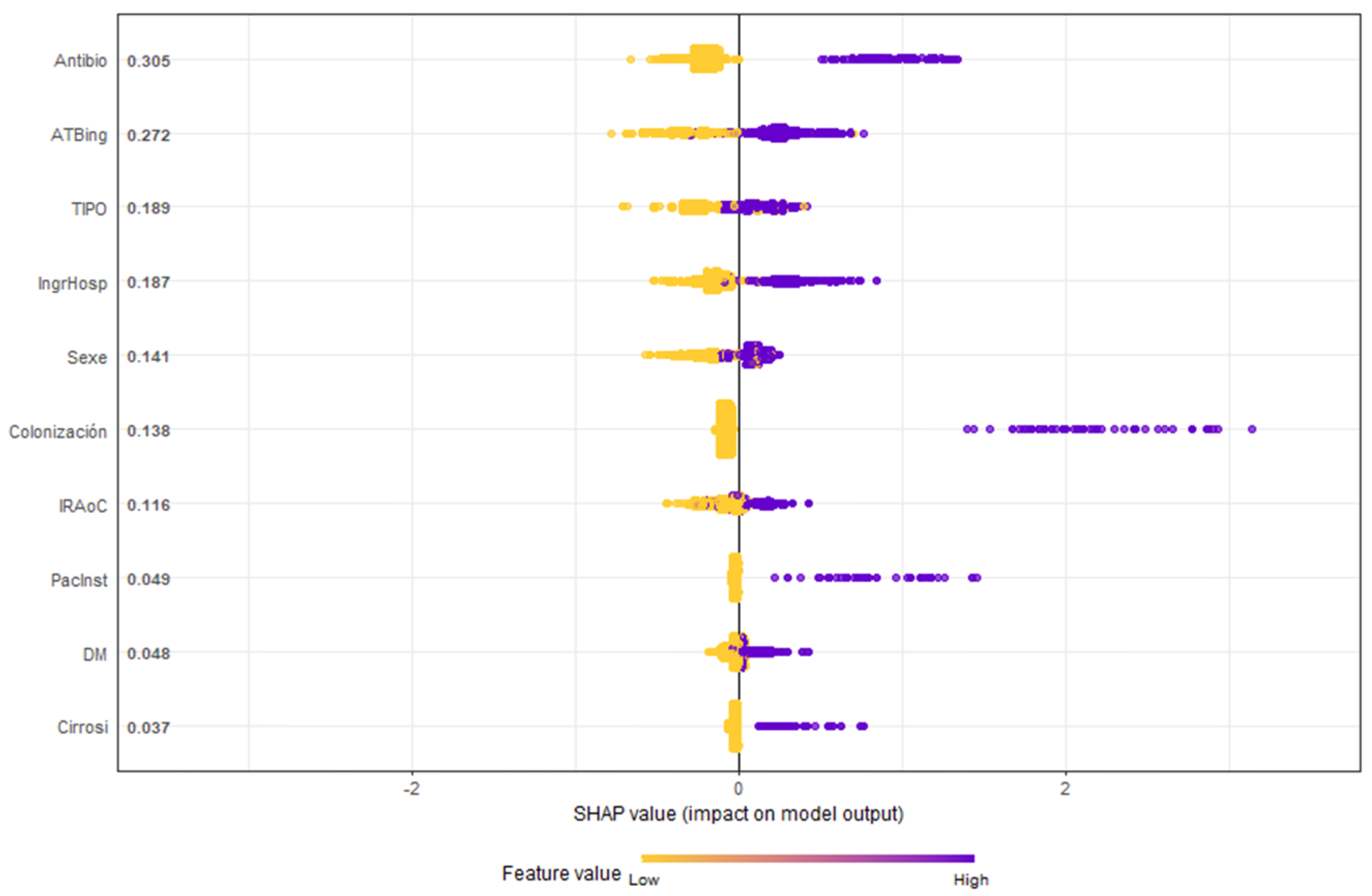

An XGBoost model was also developed, using gradient-boosted classification trees to improve total error. Parameters included maximum tree depth of 4 and a learning rate of 0.05. The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis was used to interpret variable importance in the XGBoost model [

16].

The models’ accuracy was assessed in both DG and VG by calculating sensitivity (S), specificity (E), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and correct classification percentage. Discrimination was assessed using ROC curves and the area under the curve (AUC), while calibration was evaluated with calibration curves.

Statistical analysis described categorical variables as percentages and continuous variables as medians (interquartile range) due to non-normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). The Mann-Whitney test was used for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test for categorical variables, with p<0.05 considered significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 29.0) and R statistics 4.0.3 with the lrm and SHAPforxgboost packages.

3. Results

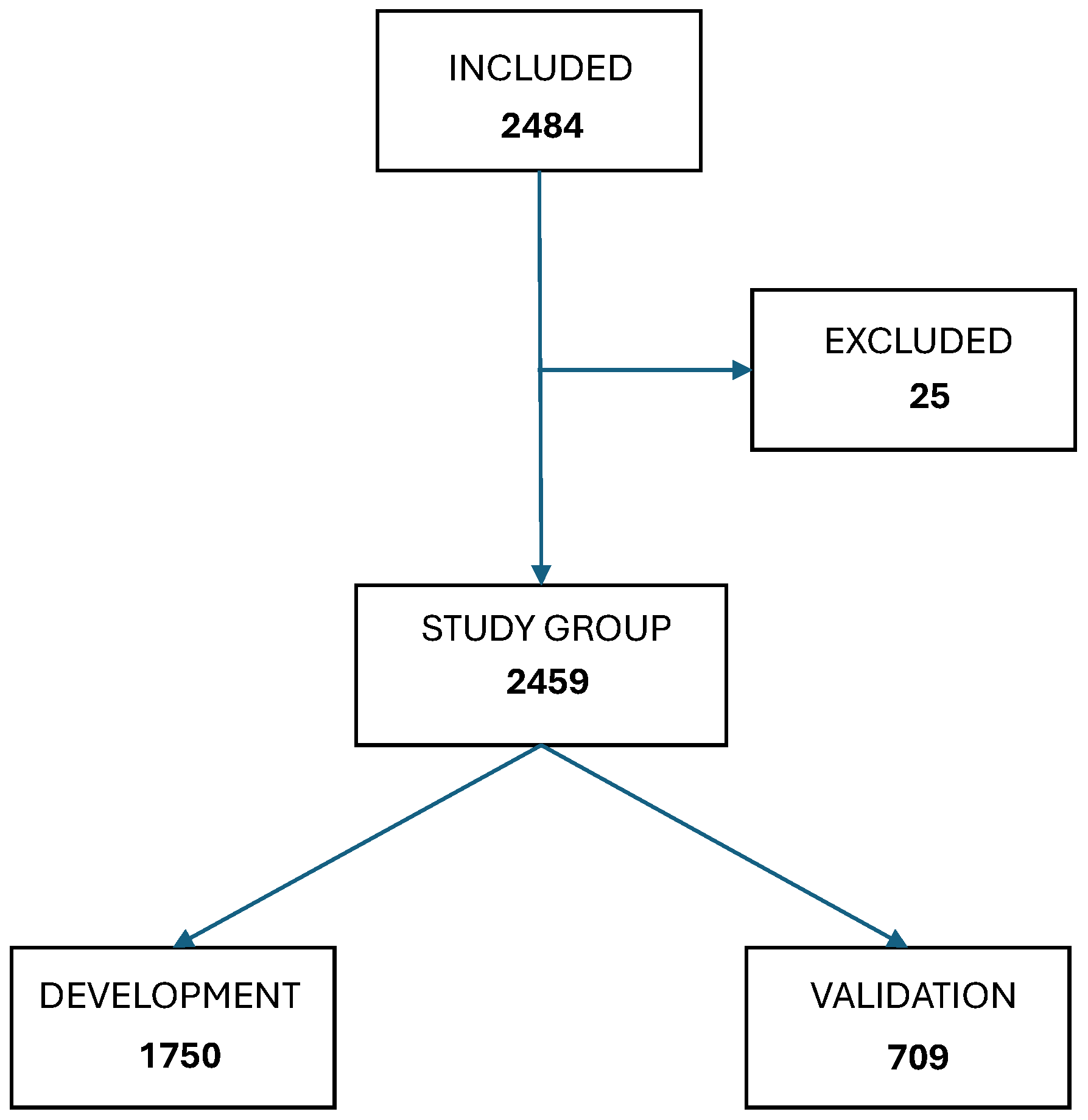

During the study period, 2,484 patients aged between 15 and 98 years (mean age 59.4 years) were admitted to our ICU. A total of 25 patients were excluded due to loss to follow-up or lack of microbiological cultures within the first 48 hours of admission, leaving 2,459 patients for the study group.

Figure 1 illustrates the patient selection diagram for the Development (GD) and Validation (GV) groups.

Of the patients, 62.9% (1,547) were male. Among all admissions, 803 (32.7%) met one or more criteria from the RZ checklist, leading to the application of contact precautions for these patients.

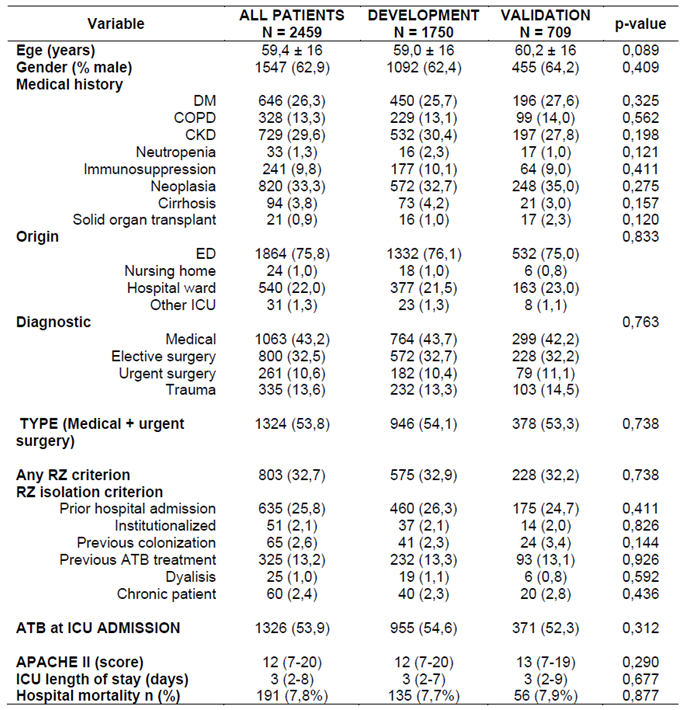

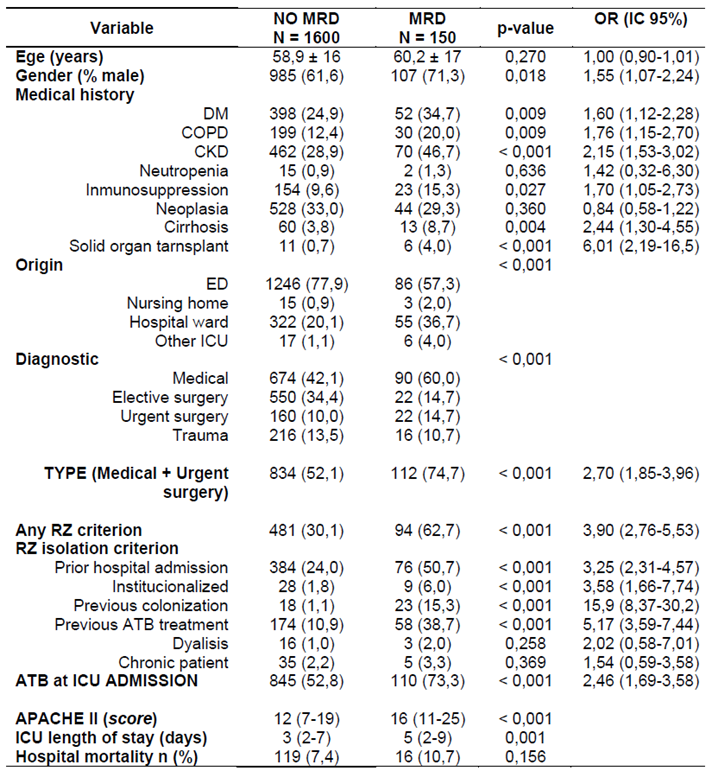

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the GD and GV groups. Approximately one-quarter of ICU admissions presented at least one risk factor for MDR colonization, with prior hospitalization being the most frequent RF, followed by prior antibiotic use.

A total of 210 patients (8.2%) were identified as MDR carriers, with 222 MDRs isolated (some patients carried more than one MDR). Among these, 92 patients (43.8%) carried extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL), 78 (37.1%) carried methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), 24 (11.4%) carried MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 13 (6.2%) carried Acinetobacter baumannii, 5 (2.4%) carried carbapenemase-producing bacteria, and 10 (4.8%) carried other MDR Gram-negative bacteria. In 57 cases (27.1%), MDR presence was associated with infection; in the remainder, it represented colonization.

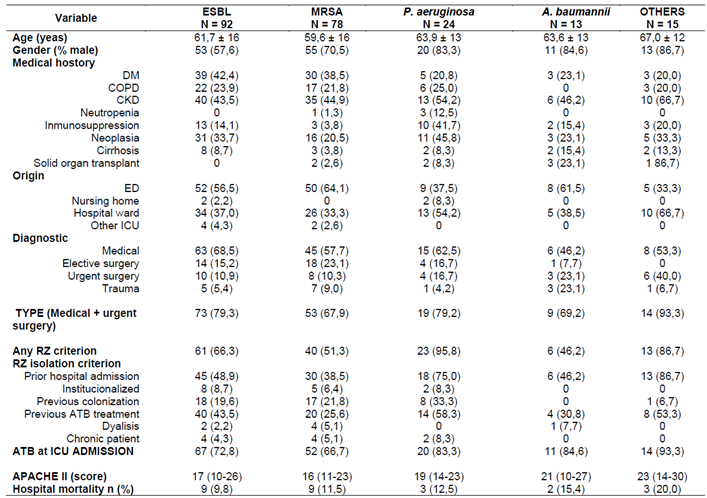

Table 2 details the characteristics of patients with isolated MDRBs in the GD.

Of the MDR carriers, 132 patients (62.8%) had risk criteria according to the RZ checklist. Among these, 50 patients (38%) had one RF, 53 (40%) had two, and 29 (22%) had three or more RFs, indicating an accumulation of risk. The presence of more RFs correlated with a higher probability of MDR carriage (p<0.001). In 78 MDR carriers (37%), none of the RFs from the RZ project were identified.

Table 3 also provides univariable risk values (odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals) and highlights candidate variables for inclusion in multivariable models.

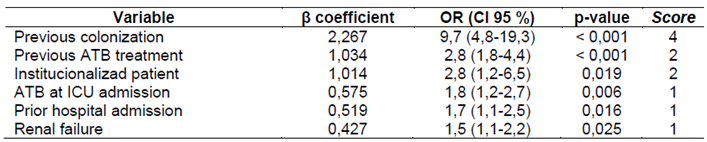

Using binary logistic regression, we identified that prior MDRB colonization or infection, prior antibiotic use, institutionalization, recent hospitalization, and renal failure were the most influential factors for MDR presence upon ICU admission (

Table 4). The simple score methodology assigns weighted scores to these variables, reflecting their importance.

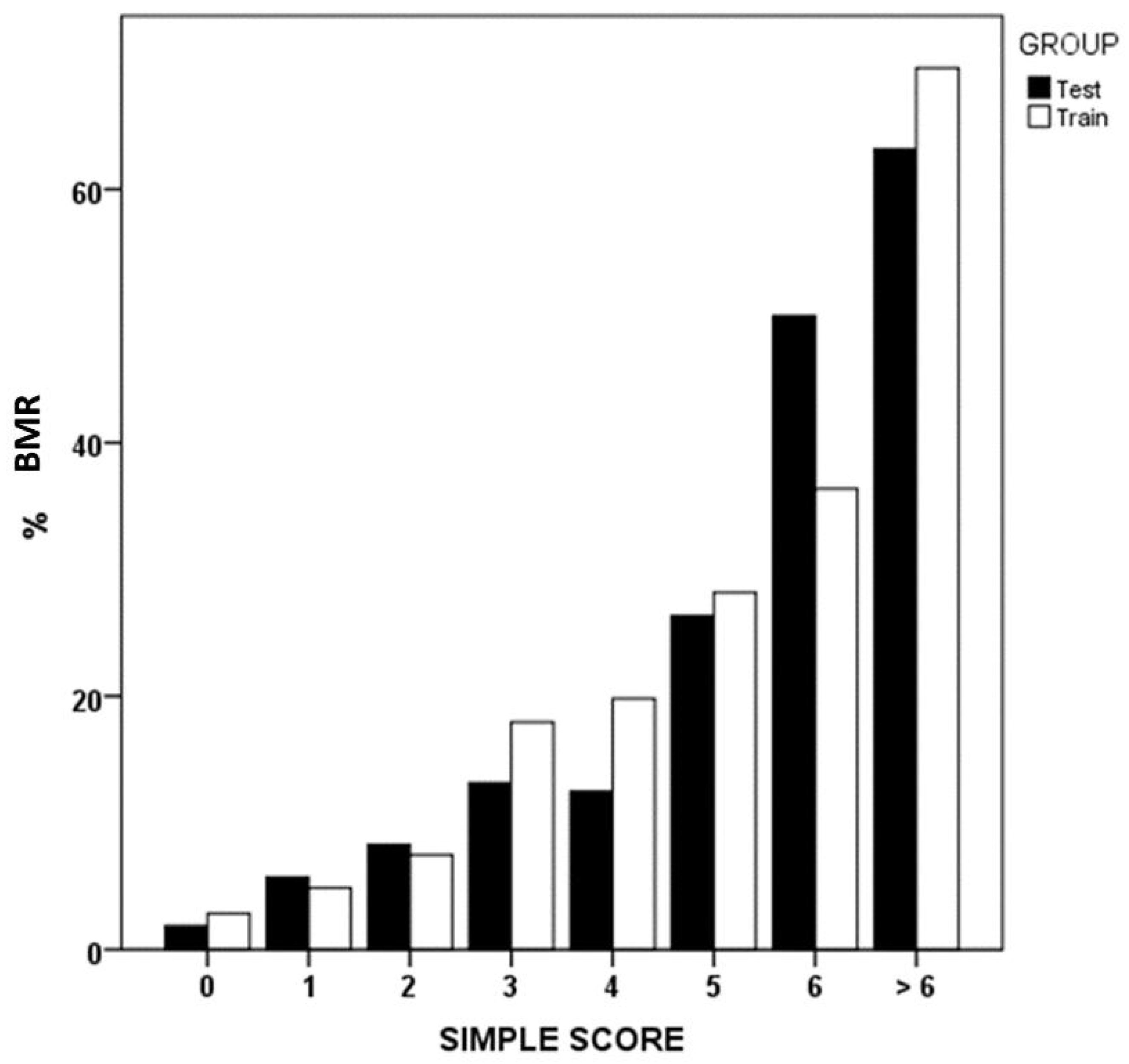

Figure 2 shows MDR prevalence in GD and GV groups according to the simple score.

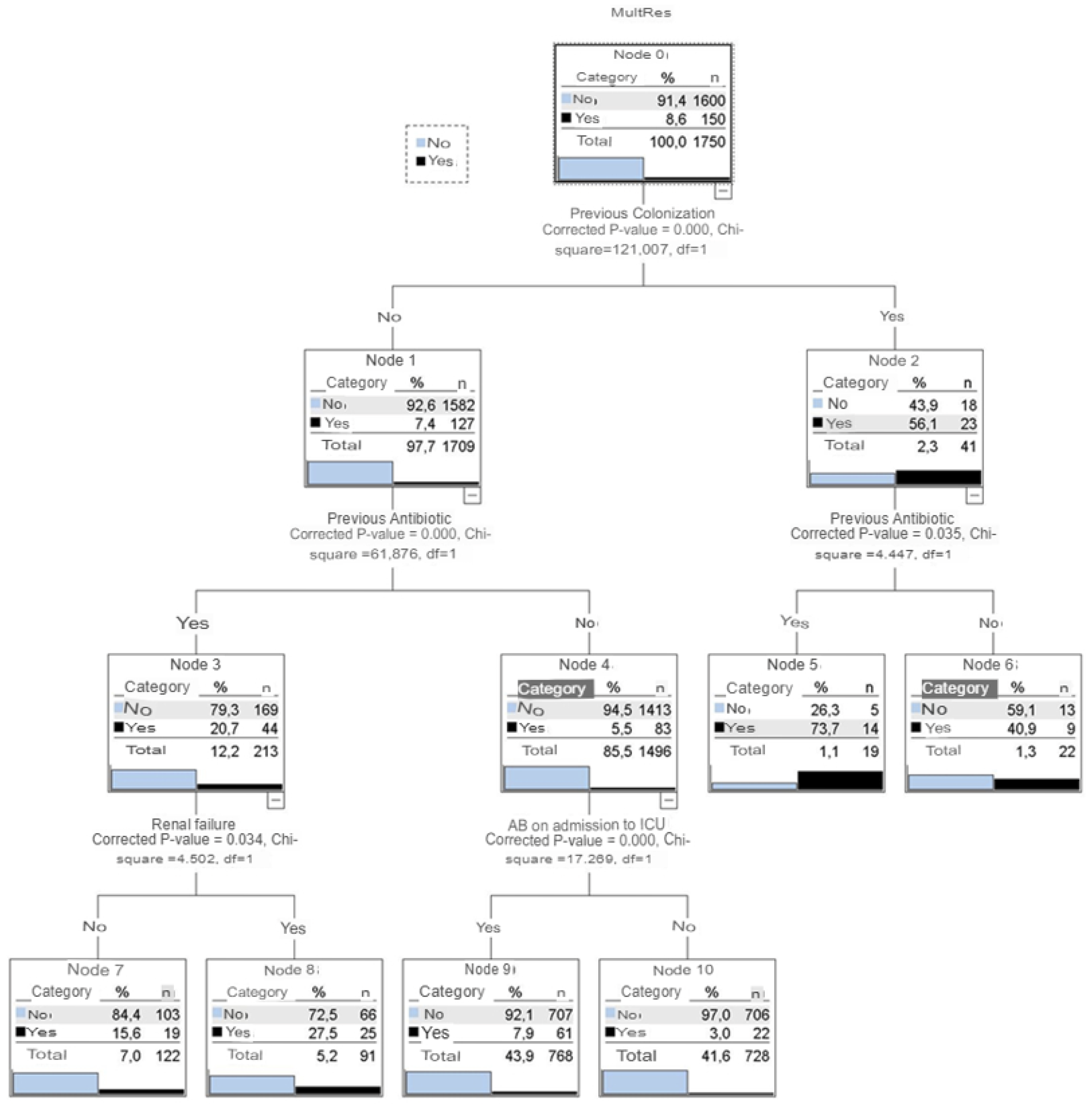

A CHAID classification tree (

Figure 3) identified four key variables: prior colonization, prior antibiotic use, renal failure, and indication for antibiotic therapy at ICU admission. Among patients with prior colonization or infection, 56% had MDR upon ICU admission. This percentage increased to nearly 74% with prior antibiotic use. Patients without prior colonization showed 7.4% MDR prevalence, which rose to 20.7% with prior antibiotic use and 27.5% with additional renal failure history.

Table 4 highlights the SHAP methodology, ranking variables by importance. Notably, antibiotic use before or at ICU admission emerged as the most significant RFs.

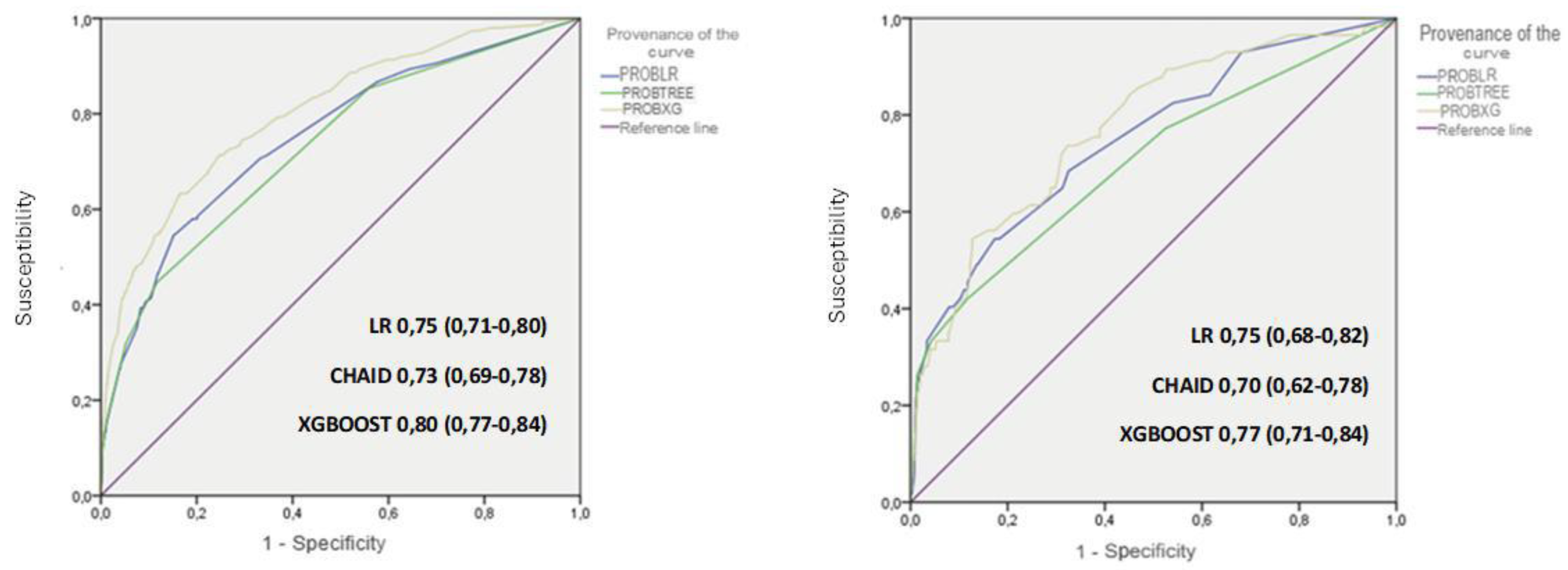

Figure 5 illustrates the discriminatory capacity of the models in GD and GV, measured by the area under the ROC curve (AUROC). The XGBoost model achieved the highest values, maintaining discriminatory power in GV.

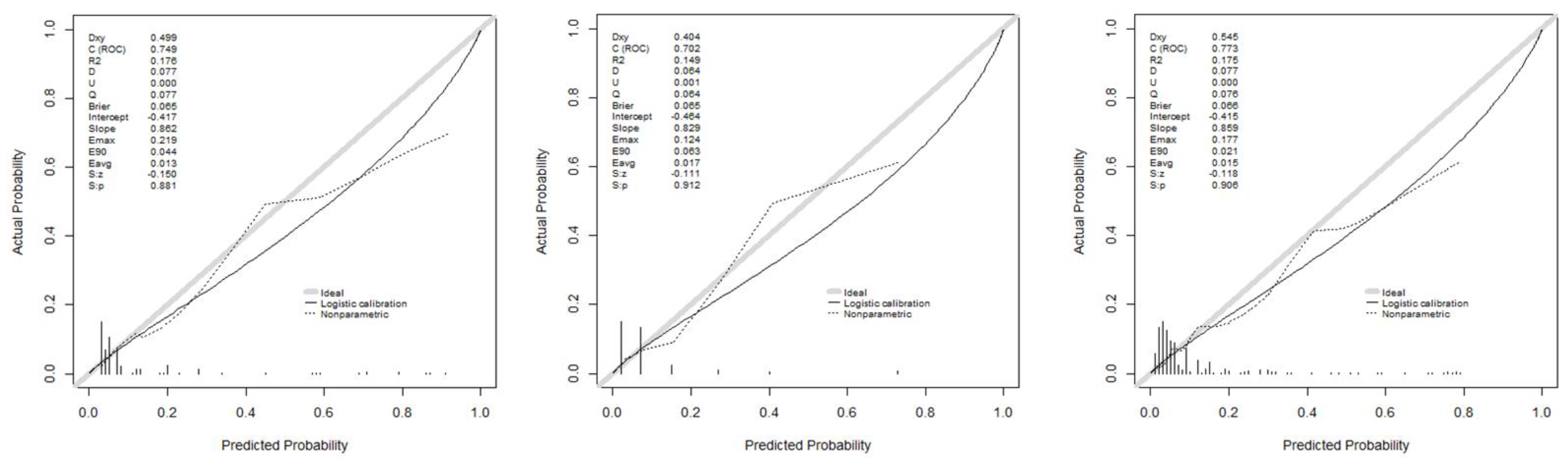

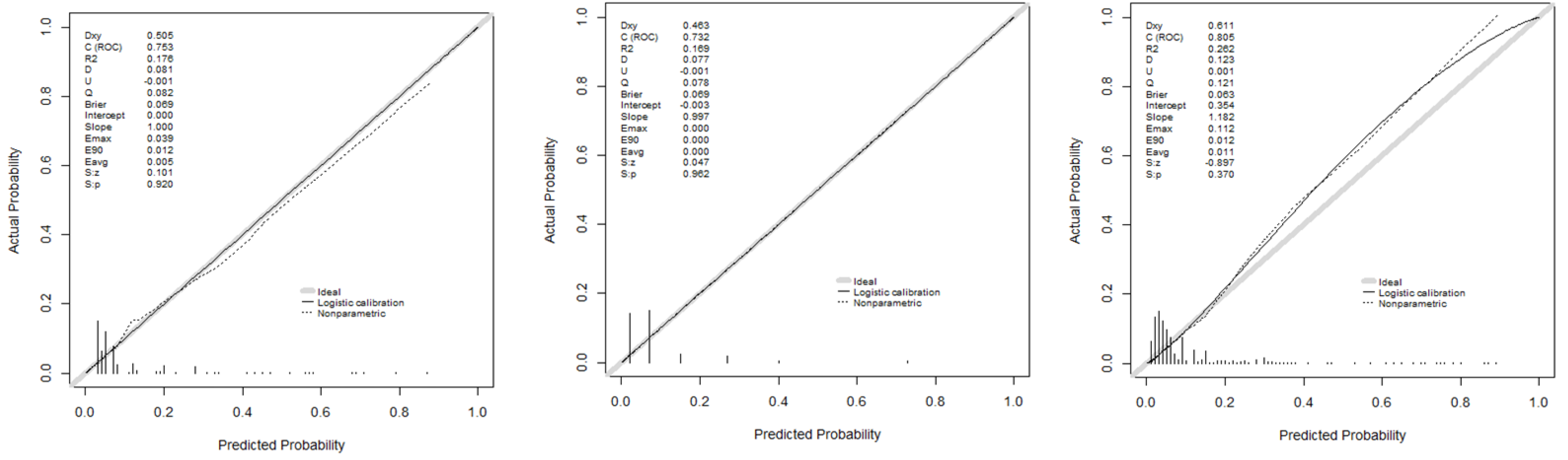

Figure 6 presents calibration curves, which show acceptable values, albeit with some loss of calibration in GV.

Applying the RZ criteria, isolating 32.7% of patients effectively captured 62.8% of MDR carriers. A simple score >1 improved MDR identification to 70.5% while isolating 37.1% of patients. Using the CHAID tree without the antibiotic indication variable, isolating 14.4% of patients achieved 56% MDR identification. Adding this variable increased isolation to 57.3% and detection to 83.1%. This left 1,051 patients undetected by these criteria, of whom 35 were MDR carriers. Annex 1 describes these 1,051 patients (35 MDR vs. 1,016 non-MDR). Undetected MDRs were associated with male gender, unplanned admissions, higher APACHE II scores, and no significant difference in mortality.

Figure 4.

Honeycomb chart showing the evaluation of the variables of the GXBOOST model with SHAP analysis. ATB: previous antibiotic therapy (7 days in prior month); ATB AD: antibiotic therapy upon ICU admission; TYPE: urgent medical or surgical diagnosis; Prev hosp adm: previous hospital admission (5 days in prior 3 months); Gender: male; Renal failure: acute or chronic renal failure; Nursing home: residence in a nursing home; DM: diabetes mellitus; cirrhosis: hepatic cirrhosis.

Figure 4.

Honeycomb chart showing the evaluation of the variables of the GXBOOST model with SHAP analysis. ATB: previous antibiotic therapy (7 days in prior month); ATB AD: antibiotic therapy upon ICU admission; TYPE: urgent medical or surgical diagnosis; Prev hosp adm: previous hospital admission (5 days in prior 3 months); Gender: male; Renal failure: acute or chronic renal failure; Nursing home: residence in a nursing home; DM: diabetes mellitus; cirrhosis: hepatic cirrhosis.

Figure 5.

ROC and ABC curves of the models used. According to Development and Validation group.

Figure 5.

ROC and ABC curves of the models used. According to Development and Validation group.

Figure 6.

Calibration curves of the models used. Development and Validation group.

Figure 6.

Calibration curves of the models used. Development and Validation group.

4. Discussion

ICU isolation for potential MDR carriers can exacerbate patient problems. While isolation and contact precautions reduce MDR transmission and outbreaks, they also have adverse effects, including psychological stress, compromised care quality, adverse reactions, and increased costs related to staff, materials, and logistics [

17,

18,

19]. Conscious patients may experience social and emotional isolation, perceiving care as depersonalized. Thus, isolating all ICU admissions is suboptimal; identifying high-risk patients optimizes healthcare and improves risk-benefit ratios [

20,

21].

The RZ isolation criteria achieve acceptable but suboptimal performance, missing one-third of MDR carriers. A 2021 Spanish study [

8] found unnecessary isolation in nearly 70% of patients based on RZ criteria, identifying prior MDR colonization/infection as the sole RF linked to MDR presence upon ICU admission. Padilla-Serrano et al [

10] reported prior antibiotic use and post-surgical admissions as major RFs for ESBL Enterobacteriaceae colonization.

Our models improved MDR identification but required isolation of a higher patient percentage. MDR RFs vary; prior colonization, prolonged hospitalization, and recent antibiotics were significant in our results. However, a notable proportion of MDR carriers lacked identifiable RFs from the RZ checklist. For example, nearly half of MRSA and A. baumannii carriers had no identified RFs.

Specific ICU profiles and infection data are crucial for guiding isolation decisions [

22]. Tools like the ENVIN-HELICS program track nosocomial infections and MDRs in Spanish ICUs [

23].

Our study underscores that not all RFs are equally significant. For instance, prior MDR carriage and RF accumulation notably increase MDR likelihood. CHAID decision trees provide interpretable rules to identify patients for effective preventive isolation. XGBoost offers better discrimination but is less interpretable. SHAP analysis helps clarify variable importance, particularly for antibiotic use.

In conclusion, we can state that the risk factors included in the checklist for preventive isolation of patients upon ICU admission, as outlined in the RZ project, have limitations, while machine learning models offer certain advantages. Not all risk factors hold the same importance, and the decision rules provided by classification trees identify patient groups with specific characteristics. Antibiotic use, both prior to and at the time of ICU admission, is a risk factor to consider. There is a group of patients, whose specific characteristics may vary across ICUs, for whom no identifiable risk factors warranting preventive isolation are found.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MMP, JTC and SCB.; methodology, MMP, JTC; software, JTC, SCB.; validation, MMP, JTC, XNC.; formal analysis, JTC.; investigation, SCB, JTC.; data curation, SCB, MMT, GJJ, MVV, BBG; writing—original draft preparation, SCB.; writing—review and editing, MMP, JTC, XNC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Arnau de Vilanova University Hospital (protocol code CEIC 3025 approved in March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not required according to the ethics committee due to the characteristics of the study, but all patients and/or family members were informed.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATB |

antibiotic |

| MDR |

multidrug resistant bacteria |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| RZ |

Resistencia Zero Project |

| RF |

risk factors |

| ESBL |

extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales |

| MRSA |

meticilin resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| SEMICYUC |

Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva y Unidades Coronarias |

| ML |

machine learning |

| HUAV |

Arnau de Vilanova University Hospital |

| DG |

Development Group |

| VG |

Validation Group |

| VRE |

vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus spp. |

| DM |

diabetes mellitus |

| COPD |

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CKD |

Chronic Kidney Disease |

| ED |

emergency department |

| LR |

logistic regression |

| CHAID |

Chi-square automatic interaction detection |

| SHAP |

SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| S |

sensitivity |

| E |

specificity |

| PPV |

positive predictive value |

| NPV |

negative predictive value |

| AUC |

area under the curve |

References

- Caǧlayan Ç, Barnes SL, Pineles LL, Harris AD, Klein EY. A Data-Driven Framework for Identifying Intensive Care Unit Admissions Colonized With Multidrug-Resistant Organisms. Front Public Health. 2022 Mar 17;10.

- Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of Mortality Associated with Methicillin-Resistant and Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia: A Meta-analysis [Internet]. Vol. 36, Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/36/1/53/283567.

- DiazGranados CA, Zimmer SM, Klein M, Jernigan JA. Comparison of Mortality Associated with Vancomycin-Resistant and Vancomycin-Susceptible Enterococcal Bloodstream Infections: A Meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2005;41:327–33. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/41/3/327/337451.

- Cosgrove SE, Qi Y, Kaye KS, Harbarth S, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. The Impact of Methicillin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia on Patient Outcomes: Mortality, Length of Stay, and Hospital Charges . Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005 Feb;26(2):166–74.

- Song X, Srinivasan A, Plaut D, Perl TM. Effect of Nosocomial Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Bacteremia on Mortality, Length of Stay, and Costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003 Apr;24(4):251–6.

- Maragakis LL, Perencevich EN, Cosgrove SE. Clinical and economic burden of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2008 Oct;6(5):751–63.

- Strich JR, Palmore TN. Preventing Transmission of Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens in the Intensive Care Unit. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017 Sep 1;31(3):535–50.

- Abella Álvarez A, Janeiro Lumbreras D, Lobo Valbuena B, Naharro Abellán A, Torrejón Pérez I, Enciso Calderón V, et al. Analysis of the predictive value of preventive isolation criteria in the intensive care unit. Medicina Intensiva (English Edition). 2021 May;45(4):205–10.

- Carvalho-Brugger S, Miralbés Torner M, Jiménez Jiménez G, Badallo O, Álvares Lerma F, Trujillano J, et al. Preventive isolation criteria for the detection of multidrug-resistant bacteria in patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A multicenter study within the Zero Resistance program. Medicina Intensiva (English Edition). 2023 Nov;47(11):629–37.

- Padilla-Serrano A, Serrano-Castañeda J, Carranza-González; R, García-Bonillo M. Factores de riesgo de colonización por enterobacterias multirresistentes e impacto clínico. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2018;31(3):257–62.

- Ministerio de Sanidad SS e I. Prevención de la Emergencia de Bacterias Multirresistentes en el Paciente Crítico - “PROYECTO RESISTENCIA ZERO” (RZ) [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2024 Apr 4]. Available from: https://seguridaddelpaciente.sanidad.gob.es/practicasSeguras/seguridadPacienteCritico/docs/PROYECTO_RZ_-_VERSION_FINAL_26MARZO_2014.pdf.

- Garnacho Montero J, Lerma FÁ, Galleymore PR, Martínez MP, Rocha LÁ, Gaite FB, et al. Combatting resistance in intensive care: The multimodal approach of the Spanish ICU “Zero Resistance” program. Vol. 19, Critical Care. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2015.

- Yi F, Yang H, Chen D, Qin Y, Han H, Cui J, et al. XGBoost-SHAP-based interpretable diagnostic framework for alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023 Dec 1;23(1).

- Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. BMJ (Online). 2015 Jan 7;350.

- GTEIS - SEMICYUC. SOCIEDAD ESPAÑOLA DE MEDICINA INTENSIVA, CRÍTICA Y UNIDADES CORONARIAS GRUPO DE TRABAJO DE ENFERMEDADES INFECCIOSAS “ESTUDIO NACIONAL DE VIGILANCIA DE INFECCIÓN NOSOCOMIAL EN UCI”. ENVIN-HELICS 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 31]. Available from: https://hws.vhebron.net/envin-helics/.

- Lundberg SM, Erion G, Chen H, DeGrave A, Prutkin JM, Nair B, et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat Mach Intell. 2020 Jan 1;2(1):56–67.

- Abad C, Fearday A, Safdar N. Adverse effects of isolation in hospitalised patients: A systematic review. Vol. 76, Journal of Hospital Infection. 2010. p. 97–102.

- Marra AR, Edmond MB, Schweizer ML, Ryan GW, Diekema DJ. Discontinuing contact precautions for multidrug-resistant organisms: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2018 Mar 1;46(3):333–40.

- Morgan DJ, Wenzel RP, Bearman G. Contact precautions for endemic MRSA and VRE: Time to retire legal mandates. Vol. 318, JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. American Medical Association; 2017. p. 329–30.

- Cooper BS, Stone SP, Kibbler CC, Cookson BD, Roberts JA, Medley GF, et al. Isolation measures in the hospital management of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): systematic review of the literature. BMJ. 2004;329:1–8.

- Djibré M, Fedun S, Le Guen P, Vimont S, Hafiani M, Fulgencio JP, et al. Universal versus targeted additional contact precautions for multidrug-resistant organism carriage for patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2017 Jul 1;45(7):728–34.

- López-Pueyo MJ, Barcenilla-Gaite F, Amaya-Villar R, Garnacho-Montero J. Multirresistencia antibiotica en unidades de criticos. Med Intensiva. 2011 Jan;35(1):41–53.

- Álvarez-Lerma F, Palomar M, Olaechea P, Otal JJ, Insausti J, Cerdá E, et al. Estudio nacional de vigilancia de infección nosocomial en unidades de cuidados intensivos. Informe evolutivo de los años 2003-2005. Med Intensiva. 2007;31(1):6–17.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).