1. Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT) is an established treatment for patients with acute liver failure and advanced liver disease, with or without hepatocellular carcinoma. [

1]. Despite advancements in surgical techniques, novel immunosuppressive drugs, vaccination strategies, and improved perioperative care, infections in LT recipients remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality, with rates ranging between 30% and 60%. [

2]

Bacterial infections represent the predominant cause of post-transplant infections, accounting for up to 70% of cases, followed by viral and fungal infections [

3]. Postoperative bacterial infections frequently result in graft dysfunction and compromise extrahepatic organ function, often leading to prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stays. These complications may necessitate modifications in immunosuppressive regimens, thereby heightening the risk of graft rejection. Over the past decade, the prevalence of multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDRBs) in transplant recipients has risen significantly, posing a major clinical challenge with profound implications for both graft viability and patient survival [

4].

Repeated and unavoidable exposure to healthcare environments and antibiotics, combined with immunological dysfunction, places liver transplant (LT) recipients at a significantly increased risk of colonization and infection by MDRB. Identifying specific risk factors and MDRB infection rates at each transplant center is crucial for developing targeted preventive strategies aimed at improving outcomes in LT recipients. One such strategy involves the implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASPs), designed to optimize antibiotic use and mitigate the emergence of resistance in nosocomial infections. At our center, ASPs have been in place since 2018 [

5,

6].

The aim of our study is to elucidate perioperative risk factors associated MDRB infection and colonization within the first six months following liver transplantation, and to assess their influence on patient and graft survival in the context of an implemented antimicrobial stewardship program.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study

This is a retrospective study which includes a systematic review of the medical records of patients who received liver transplants between October 2019 and May 2022. The ethics committee of the General Universitary Gregorio Marañón Hospital in Madrid (Spain) has approved this study (MDR-TXH). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Data are obtained from hospital records using the HCIS (medical record manager) and Servolab (microbiological data management) programs. Patient consent was waived due to retrospective caracter and no interventionism.

2.2. Data Records

Preoperative clinical and demographic variables are recorded as age, sex, weight, height, stage and etiology of liver disease, preoperative hemoglobin, platelets, INR, cephalin time, fibrinogen, D-dimer, bilirubin, creatinine, high sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI), and Pro- B-type natriuretic peptide (proBNP).

Intraoperative data as concentrated red blood cells units, platelets units, fibrinogen, frozen fresh plasma, total crystalloids, donor age, surgery duration min, plasma disappearance rate (PDR) of green indocyanine post-arterial reconstruction, lower hemoglobin during LT, transfusion of more than 4 units of blood, hypotension phase preanhepatic, anhepatic or postreperfusion graft, were defined as mean arterial pressure (MAP) <60 mmHg during more than 15 min. Post-reperfusion syndrome was defined as MAP drop more than 30% of previous values during more than 5 minutes of duration, need for norepinephrine in surgery, and blood transfusion during LT.

Also we recorded at the start of surgery and at the end of surgery the following data: heart rate (HR), MAP, venous central saturation O2 (SvO2), temperature, cardiac index (CI), Global end diastolic index (GEDI), pulmonary vascular permeability index (PVPI), and extravascular lung water index (ELWI).

Postoperatively, we recorded data during postoperative intensive care unit (PICU) stay as hemoglobin, highest creatinine in the first 5 postoperative days, aspartate transaminase, bilirubin, hs-cTnI, Pro- BNP, length PICU stay, mechanical ventilation days, days of orotraqueal intubation, central venous line days, postoperative graft function following Toronto Classification, norepinephrine need in PICU, surgical reintervention at first week, data of death, reintubation, bacteremia in, pneumonia during PICU stay, respiratory failure, kidney failure, postoperative inmmunosupressors drugs administered (steroids, Tacrolimus, Basiliximab or Myclofenate).

2.3. Colonization Record

Patients’ cultures were reviewed between 3 months prior to the transplant and six months after it. A patient were considered to be colonized prior to transplantation if he or she has a rectal or nasal swab culture positive for methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL), carbapenem-producing Enterobacteriaceae Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenem-ase (KPC), metallo-beta-lactamase (MBC) or oxacillinase 48 (OXA-48)), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (E. faecium) (VRE), multi-resistant non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli (P. aeruginosa. A. baumanii. B. cepacia. S. maltophilia) in the three months prior to transplantation or in control cultures obtained at the time of admission to the postoperative intensive care unit (PICU) after LT. The patients were also considered colonized if any of these microorganisms appear in a diagnostic culture (blood cultures, respiratory samples (tracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage), urinary cultures, abscess samples or biological fluid cultures). Also, It were considered colonized if any of these microorganisms appear in a diagnostic culture (blood cultures, respiratory samples (tracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage), urinary cultures, abscess samples or biological fluid cultures).

2.4. Infection by Multi-Resistant Compounds

The patient’s medical history data were reviewed in the six months following the transplant. All microbiology samples are also reviewed (blood cultures, respiratory samples, urine cultures, wound samples and biological fluid cultures). The patients were considered to be infected by a MDRB after the transplant if he/she had a clinical diagnosis of infection and a culture suitable for diagnosing said infection that is positive for MRSA, ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae, carabapemenase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (E. faecium), multi-resistant non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli (P. aeruginosa, A. baumanii, B. cepacian, S. maltophilia) in the six months following the transplant, excluding cultures obtained in the first three days of admission to the PICU after transplant.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

For the statistical analysis, a comparison of the variables was made between patients who presented colonization or infection by multi-resistant microorganisms before the liver transplant and after the transplant with those who did not present this colonization/infection either before or after the transplant.

The comparison of the continuous variables between the previously defined groups was made using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test and the comparison of the qualitative variables with the Chi2 test or the Fisher exact test. Variables that obtained a value of p<0.05 in these comparisons were considered significant.

A logistic regression model was then performed to detect the independent risk factors for the appearance of infection by multi-resistant bacilli after the transplant. All those variables in which a p<0.15 had been observed in the univariate analysis for each dependent variable were introduced into the model. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 2

3. Results

3.1. Incidence

The medical records of 133 patients who received liver transplants between October 2018 and May 2022 were reviewed. Thirteen patients (9.8%) developed an infection caused by MDRBs within the first six months following liver transplantation. The mean age of the patients were 55 years. We found no association between these demographic variables and the risk of infection by MDRB (

Table 1).

3.2. Colonization

Twenty-one patients (15%) presented colonization by MDRB before transplant. Of these, 17 (12.3%) present a positive rectal exudate, 4 (2.9%) a nasal exudate, and 1 (0.7%) positive for both. After liver transplantation, 27 patients (20%) showed colonization by rectal MDRB or in cultures of other microbiological samples. The isolated bacteria are shown in

Table 2

No patient colonized by multi-resistant P. aeruginosa was detected before and after to transplant. Only one nasal exudate was found positive for MRSA in a patient who had already been previously colonized. The increase in postoperative colonization by MDRB is due to an increase in the frequency of appearance of bacteria carrying carbapenems (from 10 isolates in 8 patients (5.8% of patients) to 20 isolates in 15 patients (10.9% of patients) and vancomycin-resistant E. faecium which increases from 2 to 7 isolates.

3.3. Multi-Resistant Infection After Transplantation

We only found one infection by MDRB during the admission of patients in PICU for immediate postoperative treatment of liver transplantation. It was a pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant A. baumanii. The infectious complications recorded in the first six months after transplantation were reviewed. In the hepatology ward another 12 infectious complications caused by MDRB are recorded. A total of 13 patients (9.4%) presented infectious complications due to MDRB.

3.4. Risk Factors for Multidrug-Resistant Infection

A univariate analysis of perioperative, intraoperative, and PICU-stay variables identified 19 factors potentially associated with MDRB infection within the first six months following liver transplantation. Patients infected by MDRB had received more fibrinogen, red blood cells, or platelets transfusion intraoperatively that patients no-MDRB infection. Patients with MDRB infection also exhibited higher levels of Pro-BNP prior to liver transplantation and elevated hs-cTnI levels either at the conclusion of the procedure or during the first day of their PICU stay.

Postoperatively, we observed that AST, INR, and hs-cTnI levels on the first postoperative day were higher in patients who developed postoperative MDRB infections. Additionally, these patients experienced longer PICU and hospital stays, a higher incidence of sepsis, respiratory failure, or dialysis requirements, and poorer postoperative graft function compared to patients without MDRB infections (

Table 4).

Table 3.

Intraoperative variables recorded. Values are presented as median (25% and 75% quartiles).

Table 3.

Intraoperative variables recorded. Values are presented as median (25% and 75% quartiles).

| |

Total |

Non-infected patients

(n=120) |

Infected patients

(n=13) |

P value |

| Blood transfusion during LT |

64 (46.7) |

55 (44.4) |

9 (69.2) |

.078 |

| Concentrated red blood cells units |

0 (0-3) |

0 (0-2) |

3 (1-5) |

.018 |

| Transfusion of more than 4 units of blood |

16 (11.7)% |

12 (9.7) |

4 (30.8) |

.036 |

| Platelets units |

0 (0-0) |

0 (0-0) |

0 (0-1) |

.049 |

| Fibrinogen (gr) |

0 (0-4) |

0 (0-3) |

4 (0-4) |

.048 |

| Fresh Frozen Plasma units |

0 (0-0) |

0 (0-0) |

0 (0-0) |

.322 |

| Total crystalloids (mL) |

2325 (2000-2500) |

2300 (2000-2500) |

3000 (2400-3000) |

.322 |

| Hs-cTnI before surgery (ng/mL) |

3.4 (1.8-5.8) |

3.4 (1.9-5.9) |

3.1 (1.7-3.9) |

.790 |

Hs-cTnI 60 min after reperfusion

(ng/mL)

|

19.6 (12.4-35.1) |

18.8 (12.4-34.7) |

31.3 (23.5-49.7) |

.033 |

| Preoperative ProBNP (pg/mL) |

132(73-283) |

133 (73- 318) |

141 (50-276) |

.024 |

|

Donor age (y) |

62 (51-73) |

62 (51-73) |

69 (60-74) |

.238 |

| Graft Ischemia length (min) |

357 (312-397) |

357 (315-396) |

358 (308-420) |

0.919 |

| Hepatic Flow artery (mL/min) |

200 (140-300) |

200 (145-300) |

165 (128-265) |

0.311 |

| Portal Flow venous (mL/min) |

1115 (765-1600) |

1200 (850-1600) |

950 (685-1627) |

0.443 |

| Surgery duration (min) |

200 (178-232) |

200 (180-231) |

233 (170-260) |

.699 |

| PDR 60 mins after reperfusion (%) |

15.2 (11.2-19) |

15 (11-19.2) |

17.1 (12.4-18.1) |

.649 |

| Lower hemoglobin during LT (gr/dL) |

7.6 (6.8-9.8) |

7.6 (6.8-9.8) |

7.3 (6.5-8.4) |

.722 |

| Hypotension Phase I |

37 (27.2)% |

33 (26.8) |

4 (30.8) |

0.493 |

| Hypotension Phase II |

33 (24.3)% |

29 (23.6) |

4 (30.8) |

0.39 |

| Hypotension Phase III |

53 (39)% |

49 (39.8) |

4 (30.8) |

0.374 |

| PRS |

33 (24.3)% |

27 (22) |

6 (46.2) |

0.053 |

| Use Norepinephrine during surgery |

59 (43.4) |

51 (41.5) |

8 (61.5) |

0.165 |

| HR_baseline (bpm) |

68 (59-79) |

68 (59-78) |

66 (63-82) |

.773 |

| MAP_baseline (mmHg) |

75 (66-87) |

74 (66-87) |

80 (74-91) |

.743 |

|

CI baseline (L/min/m2) |

3.1 (2.67-3.66) |

3.1 (2.7-3.7) |

3.17 (2.6-3.35) |

.363 |

|

GEDI_baseline (mL/m2) |

639 (543-725) |

639 (539-725) |

610 (581-670) |

.823 |

| HR_end of surgery (bpm) |

82 (70-94) |

80 (70-95) |

82 (71-86) |

.773 |

| MAP_ end of surgery (mmHg) |

63 (55-70) |

62 (51-68) |

61 (55-70) |

.594 |

|

GEDI_ end of surgery (mL/m2) |

609 (508-691) |

677 (585-830) |

799 (668-821) |

.517 |

| CI_ end of surgery (L/min/m2) |

4.27 (3.2-5.1) |

3.68 (3.1-4.4) |

3.14 (2.3-4.7) |

.037 |

Table 4.

Postoperative variables recorded in the study. Values are presented as median (25% and 75% quartiles). We highlight those values that we consider relevant after the analysis.

Table 4.

Postoperative variables recorded in the study. Values are presented as median (25% and 75% quartiles). We highlight those values that we consider relevant after the analysis.

| |

Total

(n=133) |

Non-MDRB infection

(n=120) |

MDRB infection

(n=13) |

P value |

| Hb (g/dL) PICU arrival |

10.1 (8.8-11.75) |

10.05 (8.8-11.7) |

10.3 (9-11.95) |

.589 |

| Highest creatinine in the first 5 days PO |

1.43 (1.01-1.94) |

1.39(1.01-1.9) |

2.03 (1.1-2-46) |

.152 |

| AST day 1 after LT |

144 (85-262) |

133 (81-230) |

326 (163-631) |

.002 |

| AST day 2 after LT |

69.2 (36.2-169) |

66 (35--152) |

166 (56-546) |

.018 |

| INR day 1 after LT |

1.93 (1.58-2.51) |

1.91 (1.56-2.42) |

2.74 (1.83-4.57) |

.009 |

| INR day 2 after LT |

1.51 (1.28-1.89) |

1.5 (1.28-1.87) |

1.98 (1.24 -3.01) |

.215 |

| Bilirubin day 1 after LT |

3.6 (2.2-6.8) |

3.2 (1.9-8.1) |

3.65 (2.15-6.75) |

.806 |

| Bilirubin day 2 after LT |

1.9 (1-3.2) |

1.9 (1.1-3.4) |

2.15 (.8-4.75) |

.898 |

| Troponin I day 1 after LT |

66.2 (30.4-156) |

59 (27.8-123) |

138 (86.4-225) |

.024 |

| Troponin I day 2 after LT (ng/mL) |

87.9 (32.9-253) |

77 (31-249) |

161 (118-265) |

.238 |

| Pro BNP on 1st day PICU |

226 (102-384) |

219 (98-365) |

334 (208-589) |

.225 |

| PICU stay (days) |

2 (1-3) |

2 (1-3) |

3 (2-7) |

.075 |

|

Reintubation (Yes) |

11 (8) |

9 (7.3) |

2 (15.4) |

0.305 |

|

Pneumonia in PICU (Yes) |

1 (0.7) |

0 (0) |

1 (7.7) |

0.95 |

| Respiratory failure (Yes) |

43 (32.3) |

35 (29.1) |

8 (61.5) |

0.034 |

| Length Mechanical Ventilation (days) |

0 (0-1) |

0 (0-1) |

1 (0-2) |

.077 |

| Length Intubation (days) |

0 (0-1) |

0 (0-1) |

1 (0-2) |

.081 |

| Reintervention (Yes) |

37 (27.8) |

32 (26.7) |

5 (38.5) |

.274 |

| Retrasplantation (Yes) |

15 (11.3) |

12 (10) |

3 (23.1) |

.165 |

| Length intravenous Central line (days) |

2 (1-3) |

2 (1-3) |

3(2-7) |

.072 |

| Hospital stay length (days) |

16 (13 -23) |

15 (13-14) |

28 (16-48) |

.004 |

| PICU stay length (days) |

3 (2-4) |

3 (2-4) |

4 (3-7) |

.021 |

| Postoperative Graft Function 72h (I vs II,III, or IV grades) |

36 (29) |

36 (26.3) |

0 (0) |

.021 |

| Extubated patient in the operating room |

89 (66.9) |

84 (70) |

5 (38.5) |

0.057 |

| Norepinephrine need in PICU |

19 (14.3) |

17 (14,2) |

2 (15.4) |

0.598 |

| Reintervention in first week |

22 (23.7) |

19 (22.6) |

3 (23.1) |

0.36 |

| Died in first week post LT |

2 (7.1) |

2 (7.7) |

0 (0) |

0.86 |

| Death in PICU |

4 (3.2) |

4 (2.9) |

0 (0) |

0.651 |

| Died in first year post LT |

10 (7.5) |

7 (5.8) |

3 (23.1) |

0.059 |

| Bacteremia in PICU |

1 (0.7) |

1 (0.8) |

0 (0) |

0.137 |

| Other infection in PICU |

26 (19.7) |

21 (17.5) |

5 (41.7) |

0.059 |

| Sepsis |

7 (5.3) |

3 (2.5) |

4 (30.7) |

<.001 |

| PICU respiratory failure |

31 (23.5) |

25 (20.8) |

6 (46.1) |

0.035 |

| Hemodyalisis |

17 (12.9) |

12 (10) |

5 (38.4) |

0.009 |

| Readmission PICU |

5 (3.8) |

3 (2.5) |

2 (16.7) |

0.065 |

| Arterial thrombosis |

8 (6.1) |

6 (5) |

2 (16.7) |

0.156 |

| Portal thrombosis |

6 (4.5) |

4 (3.3) |

2 (16.7) |

0.035 |

| Leak bylis |

15 (11.4) |

11 (9.2) |

4 (33.3) |

0.031 |

| Cholangitis |

5 (3.8) |

3 (2.5) |

2 (16.7) |

0.065 |

| Steroids |

130 (96.3) |

117 (95.2) |

13 (100) |

0.598 |

| Tacrolimus |

69 (87.3) |

63 (87.5) |

6 (46.2) |

0.892 |

| Basiliximab |

98 (71.5) |

87 (70.2) |

11 (84.6) |

0.272 |

| Miclofenato |

101 (73.7) |

91 (73.4) |

10 (76.9) |

0.54 |

| MDRB colonization before LT |

22 (16.5) |

17 (14.2) |

5 (38.5) |

0.028 |

| MDRB colonization at PICU |

28 (21) |

21 (17.5) |

7 (53.8) |

0.005 |

Then, a multivariate analysis of the indicated parameters were performed. We found that pre-transplant colonization with MDRB (OR 5.72 CI 1.7-18.7 p=0.005). and the use of dyalisis during PICU stay (OR 6.42 CI 95% 1.7-23.4; p =0.009) were an independent risk factor to develop MDRB infection in the postoperative period up to six months after transplant

3.5. Survival

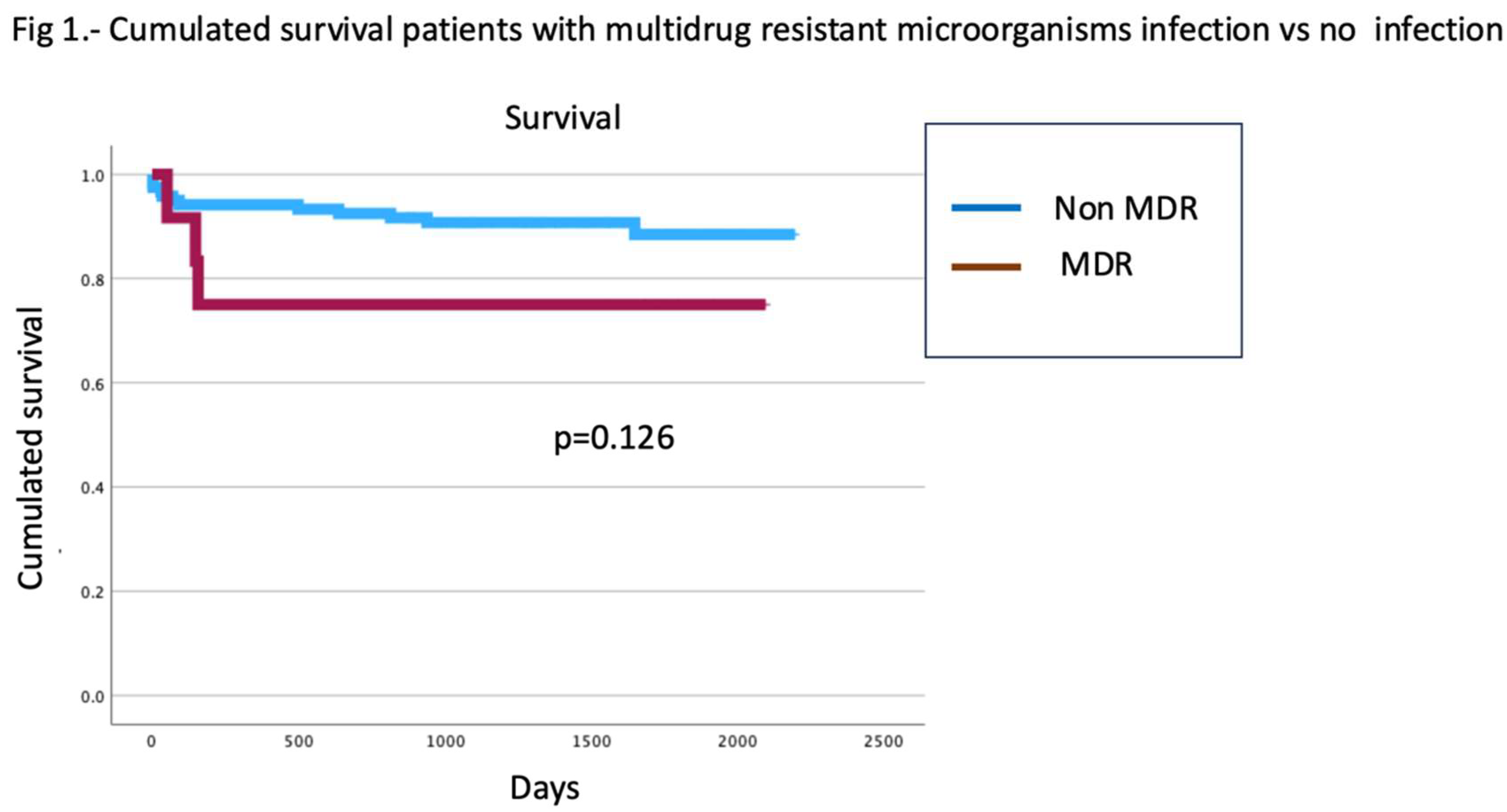

Finally, patients who developed MDRB infections showed no differences in survival compared to those without MDRB infections (Log rank =0.126) (

Figure 1)

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

In our study, we observed the existence of various risk factors independently associated with the occurrence of MDRB infections during the first six months postoperatively. The results of this research highlight the importance of prior colonization by these microorganisms and the need for renal replacement therapy during the immediate postoperative period, although other predisposing factors have also been identified in this study.

It’s well known that pre-transplant colonization has been identified as an independent risk factor for MDRB infections within the first six months following LT [

7]. This underscores the critical need for routine screening for MDRB colonization. The prevalence of MDRB colonization is considered one of the unresolved issues with the greatest impact on health [

8]. It has been shown that the most important pathogens are Gram-negative bacteria [

9]. The incidence among patients on the liver transplant waiting list is very high, and its impact on the postoperative course is profound [

10]. By this reason, it is essential to develop strategies focused on preoperative decolonization and/or preventing the progression from colonization to infection, particularly in immunocompromised patients, such as those undergoing liver transplantation.

There is currently uncertainty about whether MDRB colonization is an indirect marker of patient frailty or severity, indicating a need for a higher number of antibiotics, with the consequent intestinal dysbiosis, or whether colonization physiopathologically affects the clinical course of patients.

Kidney injury following LT is a relatively common complication, with its incidence varying depending on the classification criteria used. Studies have shown that it is associated with 30-day mortality, graft dysfunction, and overall mortality [

11,

12]. The development of acute kidney injury in the postoperative period is multifactorial; however, patients with renal failure, particularly those requiring dialysis, are at a significantly higher risk of infection by MDRBs [

13]. This increased risk necessitates greater use of antibiotics and prolonged hospital stays, thereby enhancing exposure to MDRBs [

14]. Notably, a high prevalence of infections caused by MDRBs, such as vancomycin-resistant enterococci and methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus, has been reported in dialysis patients [

15].

In our study, we did not observe significant differences in baseline renal function prior to LT between patients who developed MDRB infections within six months post-LT and those who did not. However, pre-LT MELD scores were higher, albeit not significantly, in patients who later developed MDRB infections. The MELD score is widely used to assess the severity of chronic liver disease and serves as a predictive tool for mortality among patients on the LT waiting list. This score incorporates INR, bilirubin, and creatinine levels. While preoperative creatinine is a recognized risk factor in many types of surgical interventions, this association has not been consistently demonstrated in transplant surgery patients [

16,

17]. Moreover, our cohort showed a higher incidence of sepsis, which may have substantially contributed to the development of acute kidney injury. Both the direct effects of sepsis on renal function and the necessity of broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat severe infections in immunosuppressed patients could explain why a greater proportion of MDRB-infected patients in our study required renal replacement therapy during their stay in the PICU.

Our study highlights notable differences in the hemodynamic profiles of patients who developed infections caused by MDRBs compared to those who did not within six months following surgery. Patients who developed MDRB infections exhibited significantly impaired myocardial function during the intraoperative period of LT and the immediate postoperative phase, as assessed through measurements of cardiac output, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI), and proBNP levels.

To date, no prior studies have established a direct relationship between MDRB infections and myocardial function. However, existing evidence suggests a strong association between myocardial stress and the development of non-cardiac postoperative complications. Noordzij and colleagues reported a higher incidence of sepsis in non-cardiac surgeries among patients with elevated hs-cTn levels. It has been hypothesized that the perioperative stress response—which includes inflammatory activation, sympathetic and neuroendocrine hyperactivity, immunosuppression, and hypercoagulability [

18] -in conjunction with perioperative complications such as bleeding-anemia, hypovolemia-tachycardia, and hypoxia, may initiate or exacerbate myocardial cell injury [

19,

20]. Furthermore, myocardial injury, characterized by diastolic dysfunction and reduced cardiac output, may impair the ability to meet the increased perfusion demands of extracardiac tissues affected by surgical trauma. Based on these findings, we propose that a causal relationship is plausible, whereby patients with MDRB colonization are predisposed to developing infections by these microorganisms, which carry an elevated risk of severe complications.

The manipulation of the biliary tract during LT predisposes to the contamination of bile, which in turn may predispose patients to infections caused by MDRB. Sugawara et al. observed in patients undergoing hepatectomy with bile duct resection that 7.5% of their patients had biliary tract infections or colonization with MDRB. These isolates were identical to those found in incisional wound samples or blood cultures [

21]. Zhong et al. reported a higher incidence of biliary complications in patients with MDRB (30.3% vs. 4.6%) [

22]. In our study, we confirmed that patients with MDRB infections had an incidence of bile leakage nearly four times higher, which we believe was partially responsible for the presence of MDRB infections.

The need for reintervention due to bile leaks constitutes an independent risk factor for the development of MDRB infections within six months post-transplantation. This finding aligns with previous studies that link bile leaks to a higher incidence of bacterial infections. The association may stem from the prolonged use of abdominal drainage catheters often required in these cases, which significantly increases the risk of intra-abdominal and surgical wound infections [

23]. Furthermore, bile leaks may extend hospital stays, thereby compounding the risk of MDRB infections.

In our study, we did not find that the presence of pneumonia was a risk factor for infection by MDRB infections, as has been reported in other studies. However, patients who developed MDRB infections in the postoperative period of LT exhibited a higher incidence of documented respiratory failure. Although the duration of mechanical ventilation was longer in patients with MDRB infections, this difference did not reach statistical significance. We believe that with a larger sample size, statistical significance might have been achieved. We hypothesize that these patients underwent more extensive airway manipulation to improve their respiratory status, which could explain the colonization of the airway by MDRBs and the subsequent development of infections caused by these microorganisms during the late postoperative period. Additionally, airway manipulation and the increased risk of pneumonia in these immunocompromised patients may have led to the prophylactic use of antibiotics, potentially contributing to the deleterious development of MDRB.

In our study, intraoperative blood transfusion was found to be an independent risk factor for the development of MDRB infections. This finding is consistent with other studies conducted in LT recipients, where it has been identified as a risk factor for bacterial infections. A possible explanation for this increased risk of infection associated with transfusion is the greater availability of iron, a vital element for most bacteria and fungi that promotes their growth and increases their virulence by counteracting the action of natural antimicrobial mechanisms present in the host plasma [

24]. In fact, in the face of acute infections or injuries, the body responds by sequestering iron as a defense mechanism, and with transfusion, the effect of this defense is counteracted. In addition, allogeneic blood transfusion leads to the exposure of alloantigens in the circulation, which gives rise to an immunomodulatory effect with decreased action of NK cells, decreased CD4/CD8 ratio, alterations in antigen presentation or in cellular immunity [

25]. However, although blood transfusion appears to play an immunosuppressive role, it is important to highlight that it constitutes an indirect marker of greater intraoperative complications and more complex and prolonged procedures that are associated with a higher risk of infectious complications.

In the present investigation, MDRB infections are not associated with decreased survival. This is not in line with the results of other studies [

26,

27]. It is important to remember that patients with this type of infection frequently encounter additional risk factors linked to mortality, which can significantly influence their prognosis (greater liver and kidney dysfunction, age over 60 years, graft dysfunction, postoperative biliary complications or perioperative bleeding).

The impact of multidrug-resistant infections on liver transplant patients highlights the importance of knowing the ecology of each center, even each unit, in order to establish the most appropriate prevention and early treatment measures.

A better understanding of the factors influencing the development of infectious complications caused by multidrug-resistant microorganisms after liver transplant may help identify patient groups that could benefit from personalized preventive or therapeutic interventions.

We recognized that our study has several limitations, including a small sample size and its retrospective design. The data were collected from the hospital database, and any gaps in data collection during patient care may have influenced the results. Therefore, prospective studies with larger populations are needed to draw definitive conclusions regarding risk factors. Additionally, the experience of a single center may differ significantly from that of other countries or regions globally. It is also important to note that part of the study period coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to enhanced hospital hygiene measures and a reduced number of liver transplants. As a result, further research is needed to investigate future trends in MDRB infections in patients undergoing liver transplantation.

In conclusion, the results of this study allow us to expand our knowledge of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of MDRB infection in the postoperative period of liver transplantation. This knowledge is important in order to establish prevention and treatment strategies for these infections that could improve the results in these patients.

5. Conclusions

Multidrug-resistant bacteria infections after liver transplant are clinically relevant

Pre and intraoperative risk factors exist that contribute to their development.

Prior colonization by these bacteria is clearly identified as a risk factor.

Perioperative cardiac and renal function are modifiable risk factors.

Identifying modifiable risk factors may help define patient phenotypes that could benefit from personalized preventive or therapeutic interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization RR, AC, AFY, SR, IG, JH, PM, SR, AE, MP, PD, and PP, Methodology: RR, AC, AFY, IG, JH, SR, MP, PD, and PP, Software: RR, AC, AFY, IG, JH, SR, MP, PD, and PP, Validation: RR, AC, AFY, SR, IG, JH, PM, SR, AE, MP, PD, and PP, formal análisis: RR, AFY, IG, JH, MP, PD, and PP, investigation RR, AC, AFY, SR, IG, JH, PM, SR, AE, MP, PD, and PP, resources, RR, AFY, JH, PM, and PP, data curation, RR, AC, AFY, SR, IG, JH, PM, SR, AE, MP, PD, and PP, writing—original draft preparation, RR, AFY, SR, IG, JH, PM, MP, PD, and PP, writing—review and editing, RR, JH, PM, SR, AE, AFY IG, and PP, visualization, RR, AC, AFY, SR, IG, JH, PM, SR, AE, MP, PD, and PP, supervision, RR, AFY, JH, SR PM, IG, and PP, project administration, RR, JH, PM, SR, PM, AFY, and PP, All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. RR: Rafael Ramos, AC: Alberto Calvo, AFY: Ainoha Fernández-Yunquera, SR: Silvia Ramos, IG: Ignacio Garutti, JH: Javier Hortal, PM: Patricia Muñoz, SR: Sergio Ramos, AE: Adoración Elvira, MP: Mercedes Power, PD: Patricia Duque, PP: Patricia Piñeiro

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee Institutional of Gregorio Marañón Hospital Madrid Spain.

Informed Consent Statement

The Ethics Committee of the HGU Gregorio Marañón considered an exemption from the requirement for informed consent for the following reasons: This is a study of general public interest and social value in the field of biomedical research. This is a case registry in which the collection of patient personal and health data is minimized, and is maintained in a system with restricted access exclusively to researchers at the participating hospital and the study coordinators. Obtaining informed consent for this registry may be impractical in many cases, due to the patient’s acute or serious condition, many of whom have even died. Additionally, obtaining informed consent would be a limitation for the proper execution of the project, which requires a comprehensive record of all known cases. Finally, it is considered that collecting cases with the established confidentiality guarantees does not pose any risk to patients.

Data Availability Statement

Authors may grant access to the database if necessary, provided that the privacy conditions required by the ethics committee are met

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Violeta María Dueñas Valverde and Miriam Rebeca Diaz Serrano, students of medicine and surgery at the Complutense University of Madrid, for their collaboration in carrying out this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

MDRB: Multidrug-resistant microorganisms; LT: Liver transplantation; ICU: Intensive care units; hs-cTnI: High sensitivity cardiac troponin I; PDR: Plasma disappearance rate; MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; proBNP: Pro- B-type natriuretic peptide; HR Heart rate; CI: Cardiac index ; GEDI Global end diastolic index; PICU: Postoperative intensive care unit; MRSA Methicillin-resistant S. aureus; ESBLPE; Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae; CPE: Carbapenem-producing Enterobacteriaceae; KPC: Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenem-ase; MBC: metallo-beta-lactamase; OXA-48: oxacillinase 48; VRE: vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. P.: Pseudomonas; A.:Acinetobacter; St.: Stenotrophomonas; INR: International Normalized Ratio. FHF: Fulminant hepatic failure; aPTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. E. coli: Escherichia coli; Pr: Proteus. PRS: Post-reperfusion síndrome. NK Natural Killer

References

- Black, C.K.; Termanini, K.M.; Aguirre, O.; Hawksworth, J.S.; Sosin, M. Solid organ transplantation in the 21st century. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 409–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarese, A.; Senzolo, M.; Sasset, L.; Bassi, D.; Cillo, U.; Burra, P. Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in the liver transplant setting. Updat. Surg. 2024, 76, 2521–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righi, E. Management of bacterial and fungal infections in end stage liver disease and liver transplantation: Current options and future directions. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4311–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shbaklo, N.; Tandoi, F.; Lupia, T.; Corcione, S.; Romagnoli, R.; De Rosa, F.G. Bacterial and Viral Infections in Liver Transplantation: New Insights from Clinical and Surgical Perspectives. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong Nguyen M, Shields RK, Chen L, William Pasculle A, Hao B, Cheng S, et al. Molecular Epidemiology, Natural History, and Long-Term Outcomes of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales Colonization and Infections Among Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:395-406.

- Fernández A, Díez-Picazo C, Iglesias Sobrino C, Trueba Collado C, Romero Cristóbal M, Díaz Fontenla F,et al. Implementation and impact of an antibiotic control program and multidrug-resistant bacterial colonization in a liver transplant unit. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2023;115:357-61.

- Ferstl, P.G.; Filmann, N.; Heilgenthal, E.-M.; Schnitzbauer, A.A.; Bechstein, W.O.; Kempf, V.A.J.; Villinger, D.; Schultze, T.G.; Hogardt, M.; Stephan, C.; et al. Colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms is associated with in increased mortality in liver transplant candidates. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0245091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, E.; Pieper, D.H. Tackling Threats and Future Problems of Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. In How to Overcome the Antibiotic Crisis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 398, ISBN 9783319492827. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.H.; Kong, H.S.; Jia, C.K.; Zhang, W.J.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.L.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, S.S. Risk factors for pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli among liver recipients. Clin. Transplant. 2010, 24, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannella, M.; Bartoletti, M.; Campoli, C.; Rinaldi, M.; Coladonato, S.; Pascale, R.; Tedeschi, S.; Ambretti, S.; Cristini, F.; Tumietto, F.; et al. The impact of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization on infection risk after liver transplantation: a prospective observational cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cywinski, J.B.; Mascha, E.J.; You, J.; Sessler, D.I.; Kapural, L.; Argalious, M.; Parker, B.M. Pre-transplant MELD and sodium MELD scores are poor predictors of graft failure and mortality after liver transplantation. Hepatol. Int. 2011, 5, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Xia, Q.; Wang, S.; Qiu, Y.; Che, M.; Dai, H.; Qian, J.; Ni, Z.; Axelsson, J.; et al. Strong Impact of Acute Kidney Injury on Survival After Liver Transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2010, 42, 3634–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I McDonald, H.; Thomas, S.L.; Nitsch, D. Chronic kidney disease as a risk factor for acute community-acquired infections in high-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calfee, D.P. Multidrug-Resistant Organisms Within the Dialysis Population: A Potentially Preventable Perfect Storm. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 65, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharioudakis, I.M.; Zervou, F.N.; Ziakas, P.D.; Rice, L.B.; Mylonakis, E. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Colonization Among Dialysis Patients: A Meta-analysis of Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Significance. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 65, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundakci, A.; Pirat, A.; Komurcu, O.; Torgay, A.; Karakayalı, H.; Arslan, G.; Haberal, M. Rifle Criteria for Acute Kidney Dysfunction Following Liver Transplantation: Incidence and Risk Factors. Transplant. Proc. 2010, 42, 4171–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Iglesias, J.; A DePalma, J.; Levine, J.S. Risk factors for acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: the impact of changes in renal function while patients await transplantation. BMC Nephrol. 2010, 11, 30–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeloef, S.; Alamili, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Gögenur, I. Troponin elevations after non-cardiac, non-vascular surgery are predictive of major adverse cardiac events and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 117, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biccard, B.M.; Naidoo, P.; de Vasconcellos, K. What is the best pre-operative risk stratification tool for major adverse cardiac events following elective vascular surgery? A prospective observational cohort study evaluating pre-operative myocardial ischaemia monitoring and biomarker analysis. Anaesthesia 2012, 67, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landesberg G, Beattie WS, Mosseri M, Jaffe AS, Alpert JS. Perioperative myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2009; 119:2936-44.

- Sugawara, G.; Yokoyama, Y.; Ebata, T.; Igami, T.; Yamaguchi, J.; Mizuno, T.; Onoe, S.; Watanabe, N.; Nagino, M. Postoperative infectious complications caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens in patients undergoing major hepatectomy with extrahepatic bile duct resection. Surgery 2020, 167, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Men, T.-Y.; Li, H.; Peng, Z.-H.; Gu, Y.; Ding, X.; Xing, T.-H.; Fan, J.-W. Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections after liver transplantation – Spectrum and risk factors. J. Infect. 2011, 64, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C. Analysis of infections in the first 3-month after living donor liver transplantation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 1975–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.K.; Werner, B.G.; Ruthazer, R.; Snydman, D.R. Increased Serum Iron Levels and Infectious Complications after Liver Transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, e16–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blajchman, M.A. Transfusion immunomodulation or TRIM: What does it mean clinically? Hematology 2005, 10, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinar, G.; Kalkan, I.A.; Azap, A.; Kirimker, O.E.; Balci, D.; Keskin, O.; Yuraydin, C.; Ormeci, N.; Dokmeci, A. Carbapenemase-Producing Bacterial Infections in Patients With Liver Transplant. Transplant. Proc. 2019, 51, 2461–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.L.; Flood, A.; Zaroda, T.E.; Acosta, C.; Riley, M.M.S.; Busuttil, R.W.; Pegues, D.A. Outcomes of Colonization with MRSA and VRE Among Liver Transplant Candidates and Recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2008, 8, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).