1. Introduction

Despite significant advancements in reducing mortality rates, particularly within specialized centers, pancreaticoduodenectomy remains a surgical procedure associated with a significantly heightened risk of postoperative morbidity [

1]. Infections, especially those involving multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR), play a pivotal role in contributing to postoperative complications and mortality. A consistent body of evidence underscores the correlation between postoperative MDR infections and compromised short-term outcomes in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery [

2,

3].

The global dissemination of multidrug-resistant organisms within healthcare facilities is a significant and growing concern, exerting not only a substantial impact on the outcomes of surgical patients [

4] but also on the economy and sustainability of the healthcare system [

5]. For these reasons, studies dedicated to the evaluation of MDR contamination after general surgery, its epidemiology, diffusion, and possible mitigation strategies have been advocated by clinicians and healthcare providers [

6].

Intriguingly, multidrug-resistant infections exhibit a higher frequency after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) compared to other abdominal surgeries [

7]. A better understanding of the mechanisms behind this specific finding is paramount, especially considering the impact of MDR on such a complex procedure [

8].

Preoperative biliary stent (PBS) placement, in almost all cases, results in biliary contamination that, in turn, seems to play a major role in postoperative infections after pancreaticoduodenectomy [

9,

10,

11]. The routine practice of preoperative biliary stent (PBS) placement introduces a nuanced challenge, often resulting in biliary contamination and emerging as a key factor in postoperative infections following pancreaticoduodenectomy [

9,

10,

11]. The use of PBS as a 'bridge' therapy before pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with malignant obstructive jaundice remains a subject of ongoing debate. While serving to grant neoadjuvant treatments and patient referral, PBS placement is concurrently associated with an elevated risk of postoperative morbidity [

12]. This heightened morbidity can be attributed to the persistent connection established by PBS between the digestive and biliary tracts, allowing bacterial migration from the duodenum to the biliary tract and resulting in biliary contamination. The chronic nature of this contamination, often necessitating antibiotic therapy, could create an environment conducive to the selection of multidrug-resistant strains. In order to counteract this phenomenon, it is fundamental to gather information on the bacterial strains involved and the mechanisms that could lead to the development of MDR.

This study is designed to provide a thorough assessment of the impact of MDR contamination on short-term postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing PD, elucidating the intricate relationship between MDR bacteria, PBS, and bile contaminations. Through a comprehensive exploration of these dynamics, our objective is to contribute valuable insights that may inform strategies aimed at mitigating the adverse effects of MDR contamination in the postoperative period following PD, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and alleviating the burden of postoperative complications.

2. Methods

This is a retrospective study based on a prospectively maintained database of 825 consecutive patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) between January 2010 and December 2020 at our center. All patients provided informed consent for the collection of their clinical data for scientific purposes.

Demographic and perioperative variables, including age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, Body Mass Index (BMI), preoperative biliary stent, and the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, were collected. Intraoperative parameters (pancreatic texture, Wirsung’s diameter, estimated blood loss, operative time) and postoperative factors (pathological diagnosis, postoperative complications) were also analyzed.

All procedures were performed with a standardized resection by a dedicated group of surgeons in a pancreatic surgery unit and followed the same perioperative enhanced recovery protocol. Reconstruction involved a manual end-to-side pancreatico-jejunostomy (PJ) in double layers, with or without duct-to-mucosa anastomosis. Additionally, an end-to-side hepatico-jejunostomy (HJ) and duodeno/gastro-jejunostomy (DJ) were fashioned on the same jejunal loop according to Child’s modified method. However, patients with a high risk of pancreatic fistula (POPF) development due to soft texture and Wirsung’s diameter < 3 mm underwent a pancreatico-jejunostomy Roux-en-Y.

Antibiotic prophylaxis was standardized for all patients according to center protocols, designed by infectious disease specialists considering international guidelines and antibiotic resistance profiles of common pathogens isolated in our center during previous studies [

10]. Patients without preoperative biliary stents (PBS) received intraoperative amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (two grams intravenously), with the first dose administered before skin incision and repeated every three hours until the end of the procedure or the third dose. Patients with biliary stenting received a single administration of gentamicin (3 milligrams/kg) before skin incision. For penicillin-allergic patients, a combination of clindamycin 600 mg every 6 hours and gentamicin was administered.

Intraoperative bile cultures were performed in every patient, collected by needle aspiration before bile duct transection. Bacterial contamination of surgical drains was routinely evaluated through microbiological tests performed on the output. The evaluation was consistently performed on postoperative day 5 for the drain positioned posterior to the pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis.

Multi-drug-resistant bacteria (MDR) were defined as any bacteria resistant to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories, according to the definition proposed by an international expert committee and published in 2012 in Clinical Microbiology and Infections [

13].

Surgical site infection was defined as wound infection or organ/space infection occurring during hospitalization or within 30 days after surgery, according to the description provided by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [

14].

Postoperative complications within 90 days were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, considered major (MPC) if grade equal to or greater than 3 [

15].

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) was defined according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery classification [

16]. Clinically relevant POPF (CR-POPF) was defined as grade B and C [

16].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Statistical significance was defined for P-values less than 0.05. Univariate analyses employed the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test for comparing categorical variables, while Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U were utilized for comparing continuous variables, depending on the distribution of the variable. Logistic regression models were applied for both univariate and multivariate analyses. The data were presented as percentages or as median and interquartile range [IQR].

3. Results

A total of 825 patients were evaluated, with 442 patients (53.6%) undergoing stent placement and 383 patients (46.4%) without stents. Overall bile contamination was observed in 54.1% (446/825) of cases. Among patients with bile contamination, 98% (437/446) had a previous stent placement, while only 2% (9/446) did not have a previous stent placement (p < 0.001). Detailed characteristics of the overall population are presented in

Table 1.

MDR isolation in intraoperative bile cultures: MDR bacteria were present in 18.9% (156/825) of bile cultures, exclusively in the stented group.

Among patients with metallic stents, 44.3% (71/160) had MDR bacteria in the bile compared to 18.2% (36/198) with plastic stents (p < 0.001). No other specific patient characteristics in our cohort seemed to correlate with the presence of MDR in the bile at the time of the operation. Factors such as age, BMI, sex, ASA ≥ 3, past history of diabetes, diagnosis, year of the procedure, or undergoing neoadjuvant treatment did not show a clear prevalence in the MDR group.

In cases where MDR bacteria were present in the bile, the CR-POPF rate was 28.2%, compared to 19.0% in the remaining patients (p = 0.01). Reintervention was required in 11% compared to 1.3% (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, in our multivariate analysis, the development of a major postoperative complication (MPC) was correlated with the presence of MDR bacteria in the bile (OR 1.66, 95% CI: 1.1-2.52; p = 0.02). Results are summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3. In this subgroup of patients, 28.0% had an uneventful postoperative period. Considering the postoperative length of stay (LOS), patients with MDR bacteria in the bile had a prolonged LOS compared to patients without, with a median of 13 [

11] days vs 11 [

8] (p = 0.017).

3.1. MDR isolation in surgical drain:

MDR bacteria were identified in the surgical drainage during our routine evaluation on the fifth postoperative day in 144 out of 825 patients (17.4%). Among these, 72.2% had a previous biliary stent placement, while 27.8% were non-stented (p < 0.001).

When considering variables such as age, BMI, sex, ASA ≥ 3, past history of diabetes, diagnosis, year of the procedure, or undergoing neoadjuvant treatment, only ASA ≥ 3 showed a statistically significant difference in the group of patients with MDR contamination of the surgical drain, with a higher rate of ASA ≥ 3 (27.7% vs. 17.1%; p = 0.017).

The major postoperative complication (MPC) rate was 29.2% when MDR was found in the drain, compared to 18.5% in patients without MDR contamination of the drain (p = 0.006). In patients with MDR drain contamination, CR-POPF was 29.2% compared to 18.5% (p = 0.004), wound infection was 13.2% compared to 5.3% (p < 0.001), and reintervention rate was 12.5% compared to 4.3% (p < 0.001). Furthermore, in our multivariate analysis (considering pancreas consistency, Wirsung diameter, ASA score, BMI, and age), the development of an MPC was independently correlated with the presence of MDR bacteria in the drainage (OR=1.81, 95% CI: 1.21-2.73, p= 0.0042). Results are summarized in

Table 3 and

Table 4. In this subgroup of patients, 24.3% had an uneventful postoperative period. Also, in this case, patients with MDR bacteria isolated in the surgical drain showed a prolonged length of stay (LOS) compared to patients without, with a median of 13.5 [

11] days vs 11 [

7] (p = 0.001).

Regarding the mechanism of resistance, Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) bacteria contaminating the surgical site on the fifth postoperative day had a statistically significant impact on MPC, with a rate of 30.4% vs. 20.7%. We observed a statistically non-significant effect on MPC by vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) (33.3% vs. 22.3%), carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae (CPE) (25.5% vs. 22.2%), and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (21.1 % vs. 22.4%).

On the other hand, the higher impact on the length of stay was observed in patients with early VRE contamination in the surgical drain, with 18 [

27] days compared to ESBL (14 [

11] days), CPE (13 [

12] days), and MRSA (13 [

5] days). Unfortunately, only one of these observations reached statistical significance.

3.2. MDR isolation:

The incidence of major postoperative complications (MPC) increases when patients have MDR in both bile and drainage. Specifically, the MPC rate is 17.1% for patients without MDR, 27.5% for patients with MDR in the bile, 29.3% for patients with MDR in the drainage, and 33.3% for patients with MDR in both bile and drainage (p=0.002). Results are presented in

Table 5.

Among patients without MDR contamination in the intraoperative bile or drain on the fifth postoperative day, only 2.3% experienced subsequent MDR contamination in the postoperative period.

3.3. MDR bacteria:

Among MDR bacteria in both bile and drainage, the most frequently isolated bacteria belonged to the Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases category (53.8% vs. 13.6%), followed by Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (1.9% vs. 5.7%).

These bacteria were found in both bile and drainage in 67.2% of MDR patients.

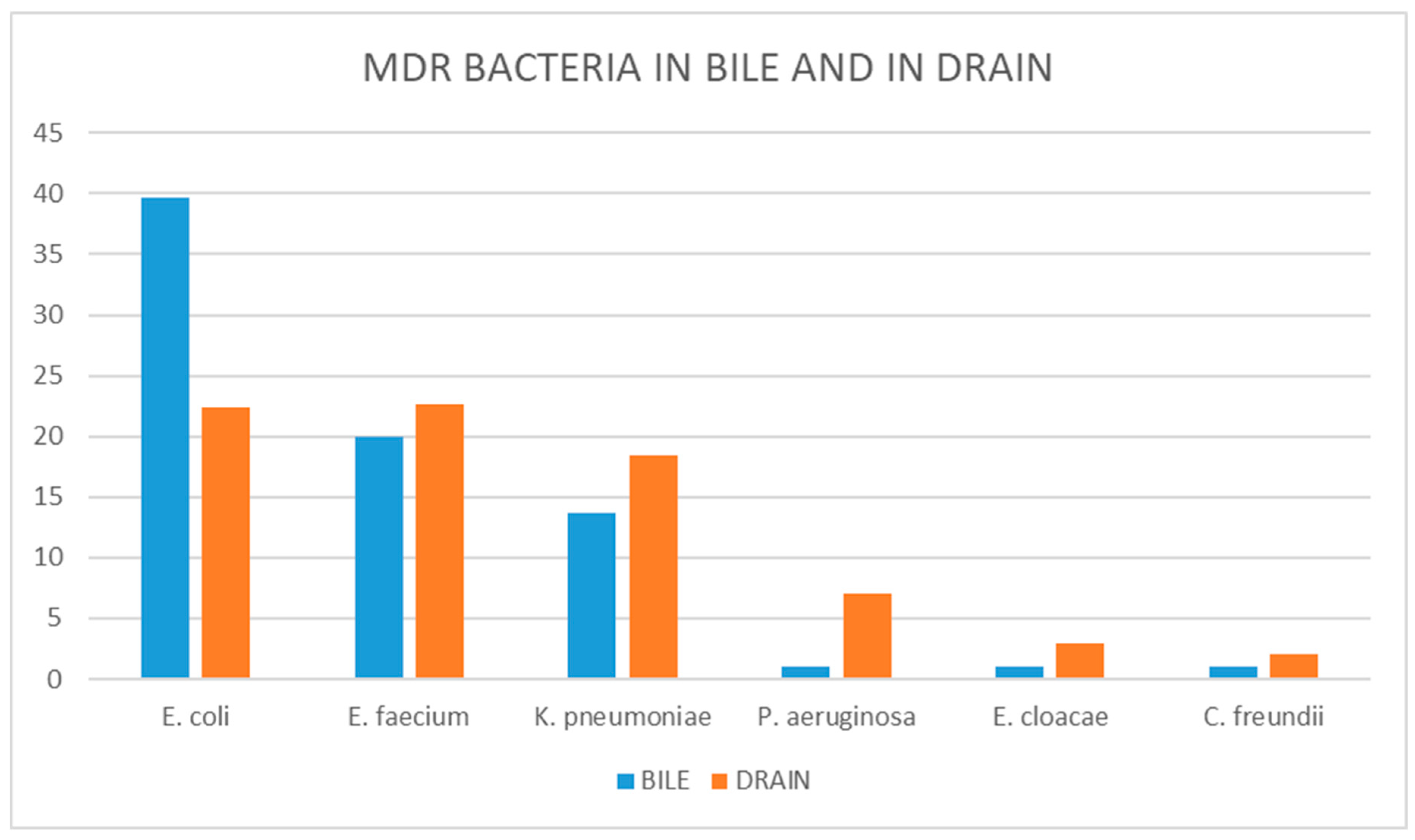

The most common MDR bacteria in bile and drainage were, respectively,

E. coli (39.7% vs. 22.4%),

E. faecium (19.9% vs. 27.2%), and

K. pneumoniae (13.7% vs. 18.4%). The complete list is provided in

Figure 1. Despite consistency in the most common pathogens early contaminating the bile and the drain, a specific different distribution can be observed in the two different environments of isolation.

The percentage of MDR traits for specific pathogens in our series, considering surgical drain isolation, is 36.4% for E. coli, 31.5% for E. faecium, 40.3% for K. pneumoniae, 35.0% for P. aeruginosa, and 40.4% for E. cloacae.

The percentage of MDR traits for specific pathogens in our series, considering the most common MDR and naïve bacteria in bile isolation, is 47.1% for E. coli, 28.7% for E. faecium, 38.5% for K. pneumoniae, 56.2% for P. aeruginosa, 33.3% for E. cloacae, 8.4% for E. faecalis, and 1.5% for C. freundii.

Without considering the MDR trait, the most common bacteria in the bile in our population are E. faecalis, C. freundii, and E. coli, with a prevalence among the bile samples of 60.7%, 47.8%, and 24.9%, respectively.

3.4. Antibiotic therapy:

In accordance with our clinical and institutional policy, systemic antibiotic therapy was not administered upon the discovery of contamination. Antibiotics were prescribed only when a clinically evident infection was present, and when available, cultural findings guided the selection of specific drugs. The choice of antibiotic therapy was discussed with the infectious disease specialist and was required in 47.3% of the overall population, 38.5% of non-stented patients, and 53.1% of those who underwent biliary stenting (p = 0.001).

Antibiotic therapy was needed in 58.2% of patients with MDR bacteria in the bile, with 70.2% of these requiring multidrug therapy. Only 44.4% of patients without MDR in the bile needed antibiotics in the postoperative period (p = 0.001).

Among patients with MDR bacteria in the drainage, 72.9% required antibiotic therapy, while 27.3% of patients without MDR bacteria in the drainage needed antibiotics (p < 0.001). In patients with MDR bacteria in the drainage, the most frequently used antibiotics were β-Lactam antibiotics, followed by Fluoroquinolones and Carbapenems. Specific antibiotic therapy rates and the number of lines of therapy are detailed in

Table 6.

4. Discussion

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a complex and technically demanding procedure associated with a high risk of postoperative infectious complications, including infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria. MDR bacteria appear to contaminate patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy more frequently than in other procedures. In our experience, this contamination occurs even before common known risk factors, such as prolonged postoperative antibiotic therapy and ICU stay [

17], can take effect, as demonstrated by the finding of MDR bacteria intraoperatively and on postoperative day 5 (POD V).

In our cohort, the rate of MDR infection in patients who were MDR-free intraoperatively and at POD 5 is 2.3%, a incidence similar to other abdominal surgical procedures [

18], and markedly different from the 17.4% MDR contamination rate of the surgical site observed on POD V in our series. These specific findings suggest that the increased rate of MDR infection after pancreaticoduodenectomy could be related to pre-existing MDR contamination, mainly at the level of the biliary tract. Previous studies have demonstrated that bile infection is associated with previous interventional biliary endoscopy, which is linked to an increased rate of postoperative infections [

19,

20]. Our study is consistent with previous experiences that reported an increase of MDR bacteria in the bile of patients with biliary stents [

21,

22]. We demonstrated that MDR bacteria were only present in the bilicultures of the stented group, and MDR bacteria in the drainage were mostly found in the stented group, with the same MDR bacteria in the bile and early in the drain in 67.2% of cases.

The nature of our study doesn't allow us to define the specific mechanisms underlying our observations. However, the rate of MDR bacteria after pancreaticoduodenectomy, their presence at the time of the procedure in the bile, and their finding on the fifth postoperative day in the surgical drain, indicating the surgical site, clearly identify the preoperative and early postoperative period as the timeframe in which MDR bacteria were selected and began to colonize patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Direct contamination during the surgical procedure or bacteremia could be the main factors that prompt the diffusion of MDR to the surgical site. However, finding them five days after the operation suggests that other mechanisms had granted their survival and reproduction despite intraoperative antibiotic prophylaxis and the immune system activity.

Furthermore, our study confirms that the presence of MDR contamination worsens short-term outcomes of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. When MDR bacteria are present in the bile and in the drainage, there is a statistically significant increase in major postoperative complications. These findings are in line with a previous study by Zhang et al. [

4], which showed that MDR infections were associated with postoperative in-hospital death within 30 days, postoperative hospital stay, and post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage. Our study confirmed that MDR infections worsened the outcome of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy, specifically in clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula, wound infections, and reintervention rate. The last finding aligns with a study by Bodro et al. [

23], which demonstrated that surgical re-intervention after pancreas transplantation was independently associated with the development of infections by MDR organisms. Also, the length of stay, as reported in other studies [

24,

25], is deeply affected by the presence of an MDR bacteria. This observation emphasizes the urgent need for a specific approach to reduce the incidence and impact of MDR in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Interestingly, the presence of MDR early in the drain seems to be correlated with patient frailty, namely ASA ≥ 3. MDR infections are more frequent in frail patients, who are also a high-risk population in the postoperative period [

26]. On the other hand, we didn't observe the same correlation with bile MDR bacteria contamination. It could be hypothesized that the initial contamination at the level of the bile is related to multiple factors, but the early contamination of the same bacteria at the level of the surgical site could be facilitated by the frailty of the patients.

In our cohort, MDR bacteria in bile and drainage were

E. Coli, E. Faecium, and

K. Pneumoniae. These findings could be explained by an ascending bacterial migration from the duodenum to the biliary system due to biliary stenting, with subsequent bile contamination. These results are similar to a previous study by Cortes et al. [

27], who reported that the most frequent organisms in cultures of intraoperative bile were

Enterococcus species, followed

by E. coli and

Klebsiella species. Of extreme interest is the finding that the microorganisms isolated more frequently in the bile,

E. faecalis and

C. freundii, aren't the same species responsible for the majority of the MDR contamination. Specific bacteria, such as

Enterobacters, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, show impressive rates of MDR compared to the susceptible strains, one in two or one in three of these pathogens were MDR in our analysis, a rate far higher than reported in the literature. Specific bacteria seem more prone to develop MDR strains in the preoperative period in stented patients; in this setting, a selective pressure seems to promote the contamination by these specific subgroups of pathogens.

A unique analysis was aimed at antibiotic therapy in the postoperative period after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Patients with MDR infections received more lines of antibiotic therapy than patients with infections caused by non-resistant bacteria. More costly and specific lines of antibiotics were used on MDR bacteria, increasing the cost for the health system and undermining the efficacy of these same drugs in the near future. Our findings suggest that in the specific case of pancreaticoduodenectomy, probably to avoid damage to the patients and the health system due to MDR contamination, the crucial point could be the pre and intraoperative period more than the postoperative. Studies on the best intraoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in these specific settings are needed, as well as the implementation of the actual stenting device to mitigate bacterial contamination, as has been done with other medical devices (e.g., urinary catheters). In recent years, the early detection of MDR bacteria by rectal swab evaluation has started to be used in clinical practice, leading to the isolation of patients with such contamination at the moment of admission [

28]. Such a strategy should be considered, especially in patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy after biliary stent placement, but studies are needed to evaluate its cost-effectiveness and efficacy for the health system. More than this, the possibility to associate other more therapeutic approaches or management protocols in this subgroup of patients needs to be assessed to improve their short-term outcomes.

Our study also highlighted that MDR bacteria in the bile were found especially in patients with metallic stents rather than in patients with plastic stents. Various literature [

29,

30,

31] suggests the superiority of metallic stents to plastic stents due to their longer patency, potentially avoiding replacement and stent-related problems in patients who are subjected to a delayed schedule or underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The efficacy of metallic stents is still debated in the pre-operative setting. Considering the larger diameter of metallic stents, it definitely helps to resolve cholestasis or obstructed bile flow by decompression. At the same time, it is also possible that more bacteria from the gut flora could be introduced into the bile duct in comparison to plastic stents. On the other hand, metallic stents are the common choice in patients who will maintain the stent longer and usually in patients who will undergo neoadjuvant therapy. This prolonged stay could represent the main cause of the increased rate of MDR bacteria contamination observed, even if in our series, we didn't observe a correlation between MDR contamination of the bile and neoadjuvant therapies.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a single-center retrospective study, while multicenter prospective studies will be necessary to confirm our results. Despite a single-center series granting a uniformity of treatment management and a standardized clinical and surgical approach that could be difficult to obtain in a multicenter setting. Second, the choice to perform microbiological tests only on POD 5 and only from the pancreatic surgical drain was not based on previous experience or literature because none was available. We chose this timeframe to detect early clinically relevant contamination, not simple direct contamination by biliary intraoperative spillage. Third, it covers a ten years' experience, and even if no major changes had occurred in surgical technique and antibiotic therapy in our center, still, the rate of neoadjuvant therapy had increased drastically through the years, and this variability could have partially affected our observation. On the other hand, the high number of patients involved in this study allowed subgroup analysis and the evaluation of even more rare pathogens such as VRE.

In conclusion, we confirm that early MDR contamination worsens the short-term outcomes of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. MDR contamination increases postoperative major complications, length of stay, and multiple antibiotic therapy. Our data suggest that the majority of MDR surgical site infections derive from the preoperative period, probably from biliary contamination resulting after the placement of a biliary stent. Under specific conditions, these bacteria early contaminate the surgical site, affecting patients' short-term outcomes. Further comprehensive studies are needed to demonstrate what intervention could influence MDR bile contamination and how to mitigate this phenomenon to reduce postoperative morbidity.