Submitted:

28 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Multistage Binomial Model

2.1. Measurement Error-Free Model

- When , , and , the MSB model is reduced to the TB model.

-

For binary outcomes ( for ), when , , and , the MSB model is reduced to the ZIB model.The ZIB model has been proposed by Hall [35] to face situations where a binary outcome contains an excess of zeros as compared to the expected zeros under the TB model. The ZIB model assumes that the binary outcome is the product of two Bernoulli processes; a zero from either process (or both) results in a zero. An example of process generating such data in health sciences was investigated by Diop et al. [63]: a study population consisting of a mixture of susceptible subjects who can experience the binary outcome of interest, and cured subjects (cure fraction) who cannot experience the binary outcome. Complications arise from not knowing the immunity (cured or susceptible) status of each subject, and the ZIB model is used to jointly estimate the cure fraction on the one hand, and the logistic regression for the susceptible subjects on the other hand [64,65,66]. Using the MSB model framework (, , , and ) to describe the ZIB model, the success probability of the binary outcome is and the probability that a subject i is cured is . Thus, in this case, the main difference between the MSB model and the ZIB model is that the MSB model allows the minimum probability to be greater than zero, and the maximum success probability to be less than one.When the susceptibility probability is constant across subjects in the ZIB model, the latter can alternatively be considered as a one stage model () with and . In this case, the success probability of the binary outcome is and the probability that a subject i is cured is .

2.2. Multistage Binomial Model Specification

2.3. Conjugate Distribution for Measurement Errors

- For the logit link, and the conjugate distribution of measurement errors is the distribution such that the linear combination follows a logistic Bridge distribution (which is the conjugate distribution of random-effects in marginalized mixed effects logistic models [74]).

- For the probit link, and the conjugate measurement error distribution is the normal distribution with null mean vector and covariance matrix . This follows by Proposition 4 in [75].

2.4. Regularity Conditions and Identifiability

- C1-

- All predictors in the MSB model are bounded, i.e., there exist compact sets (for ), and such that , , and for every . For every , for , for , and for . For every , , and , the are linearly independent. For every and , and the are linearly independent, and for every and , the are linearly independent.

- C2-

- The true parameter vectors , and lie in the interior of known compact sets for , , and respectively.

- C3-

- There exists, for each stage j, a continuous predictor which is in but not in any (for all ), nor in , neither in . Moreover, there exists at least one continuous predictor, either in but not in nor in (for all ), or in but not in nor in (for all ).

- -

- In fact, the motivation of the MSB model assumes that we have some prior knowledge of the steps of the multistage process that generates the binary outcome . This implies that, for each step that we are aware of, we know about at least one specificity that differentiates it from other known steps. This is reflected by condition C3. If our prior knowledge of the steps of the process is confused to the point that two stages share the exact same predictors or risk factors, then we should consider that the two stages are only one known (meaningful) stage.

- -

- If all stages of the modeled process are known and accounted for, the model approaches the limiting special case where and . In this situation, the distinct continuous predictor in each of the q stages (condition C3 is only required for stages. That is, one of the q stages may not have a distinct continuous predictor.

- -

- A continuous predictor is required in the design matrix of either ( in ) or λ ( in ) only if both and are being estimated. For instance, in the important special cases where either or , no distinct continuous predictor is required in any of and design matrices, if present.

- For a logit link function, Proposition 2 remains true if the conjugate measurement error distribution were replaced by the (multivariate) normal distribution with null mean vector. This follows from Theorem 1 of Shklyar [77], given that the error covariance matrices are assumed known in the MSB model (8).

- In the case , the model remains identifiable if all covariance matrices are only known up to a unique scaling factor (see Theorem 2 of Kuchenhoff [78]). In particular, if the unique stage includes only one error-prone continuous predictor, then under conditions C1–C3, a homogeneous variance of the measurement errors is identifiable along with all other model parameters. Extension to requires further investigations.

2.5. Penalized Maximum Likelihood Estimation

2.6. Testing for Unit Asymptote

3. Simulation Studies

3.1. Simulated Examples on Mutated Protein Viability

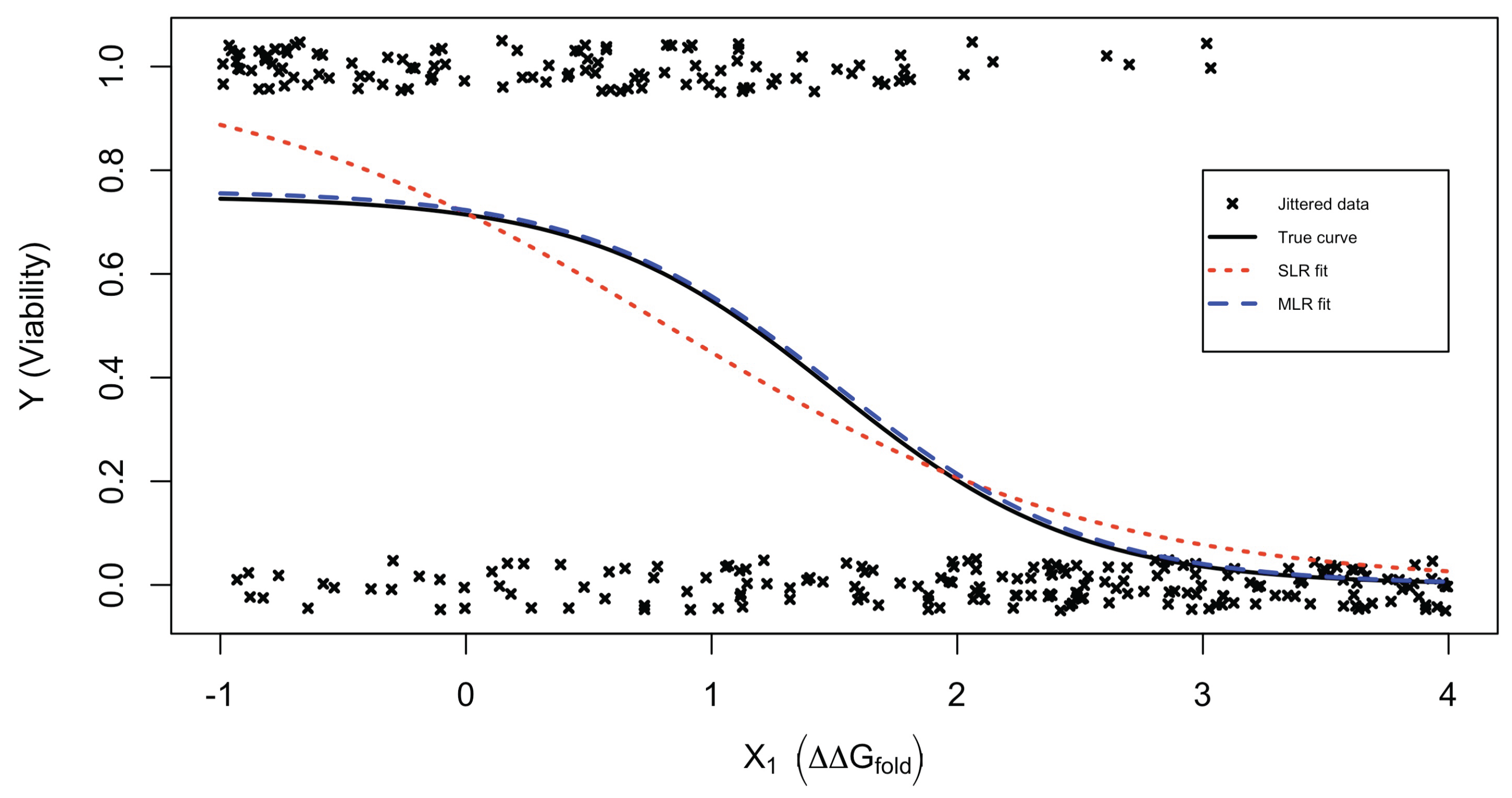

3.1.1. Example 1: Simple Logistic Regression Analysis

3.1.2. Example 2: Two-Stage Logistic Regression Analysis

3.2. General Performance in Synthetic Data

3.2.1. Bias and Accuracy

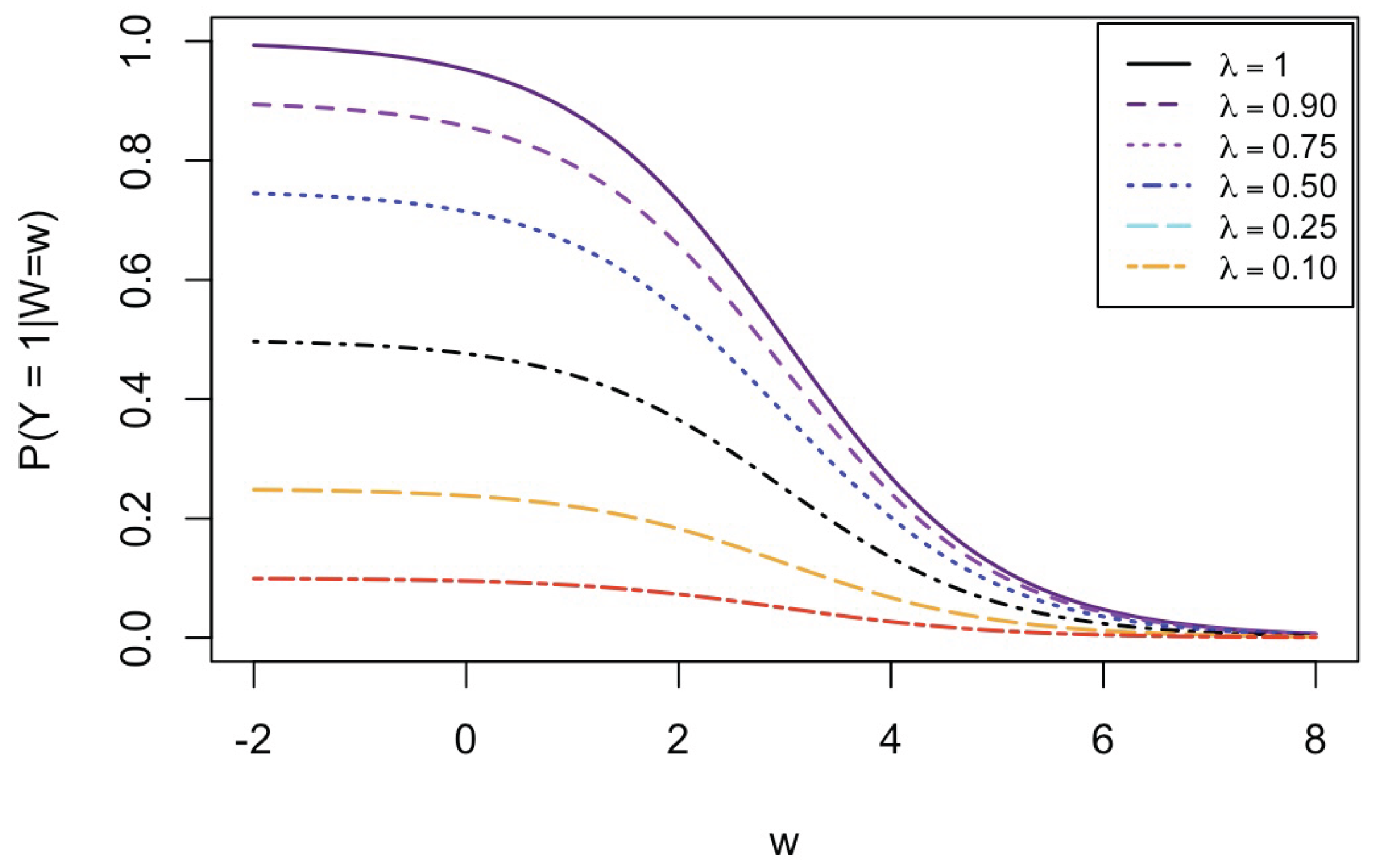

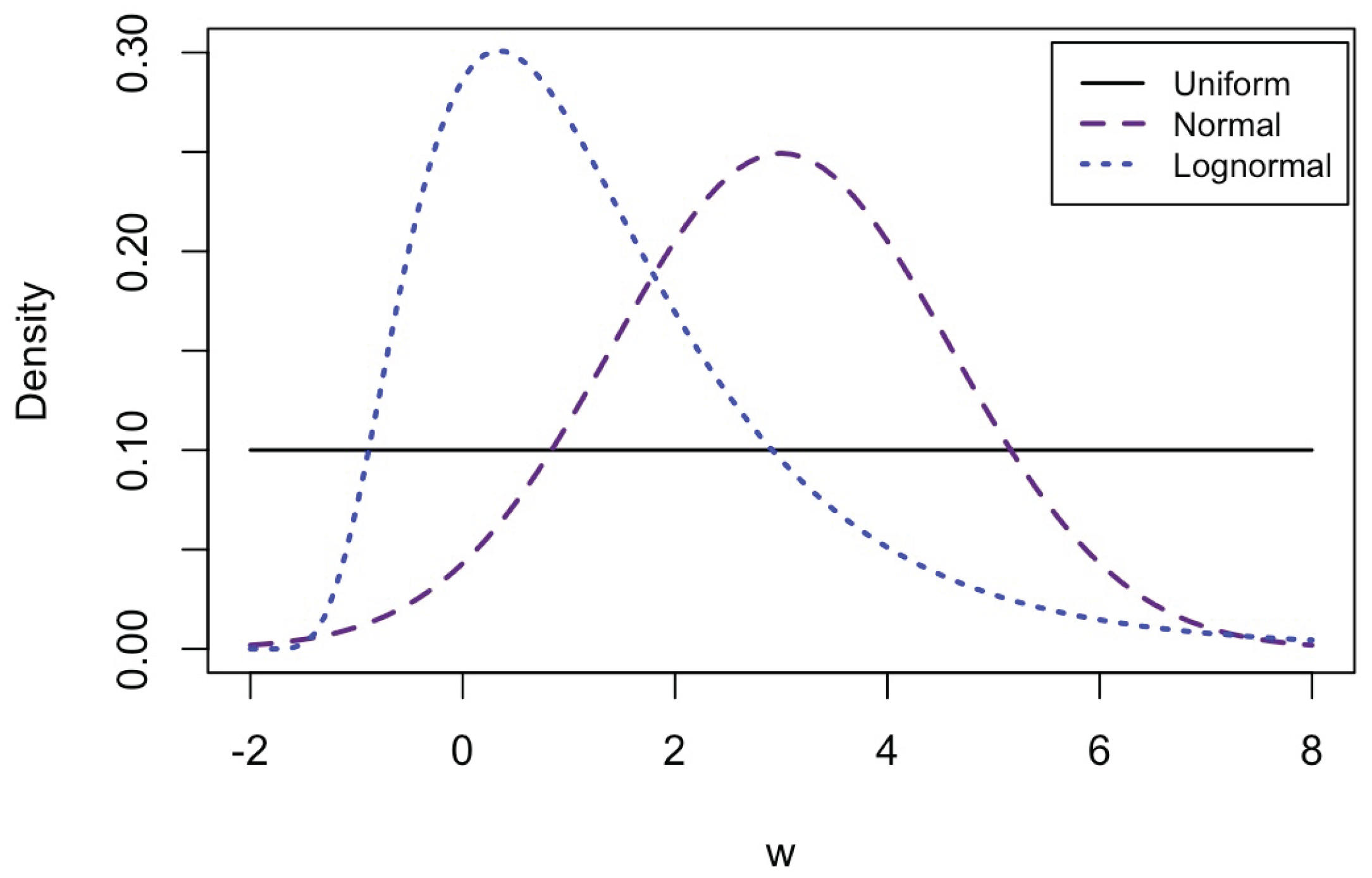

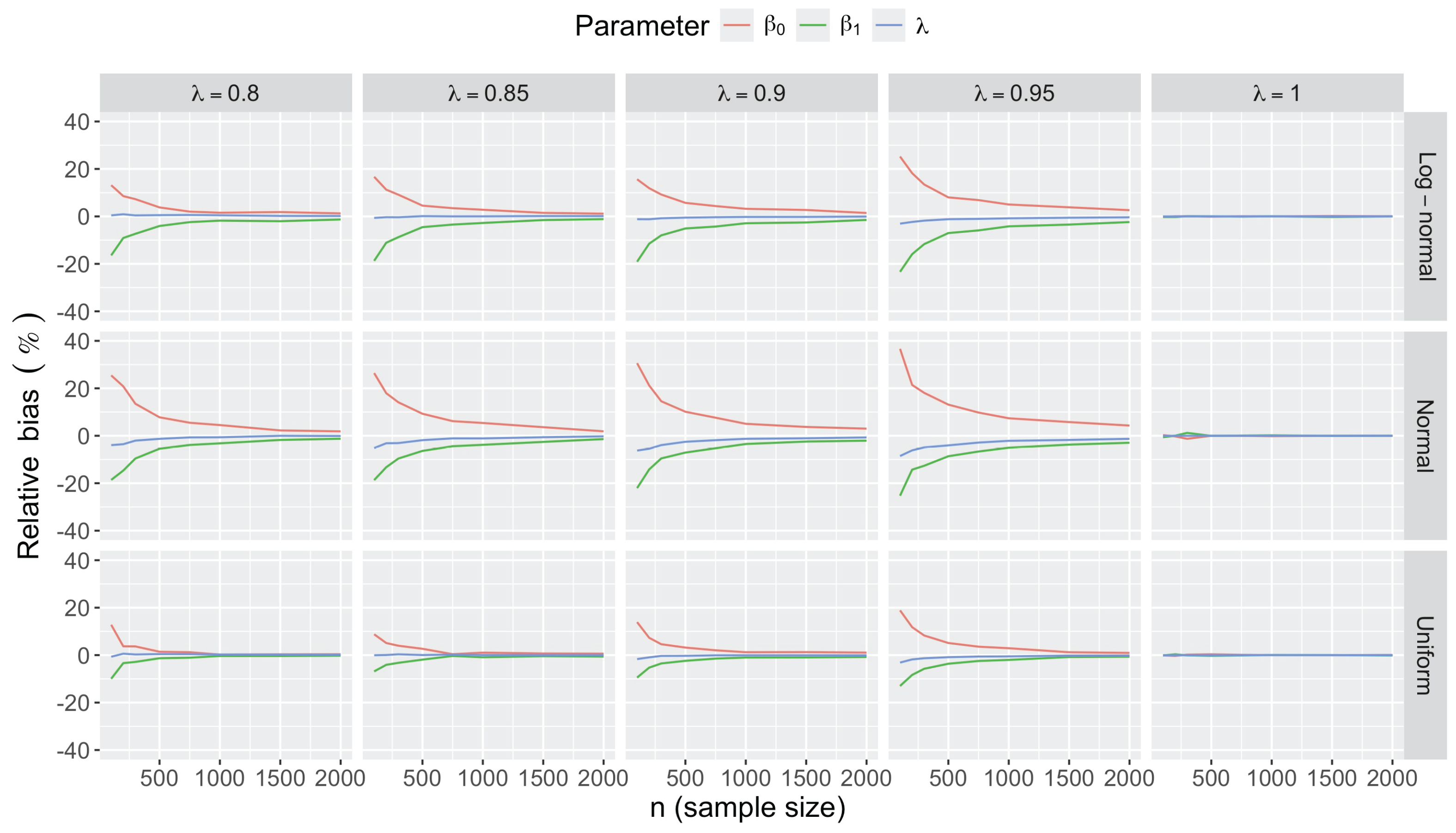

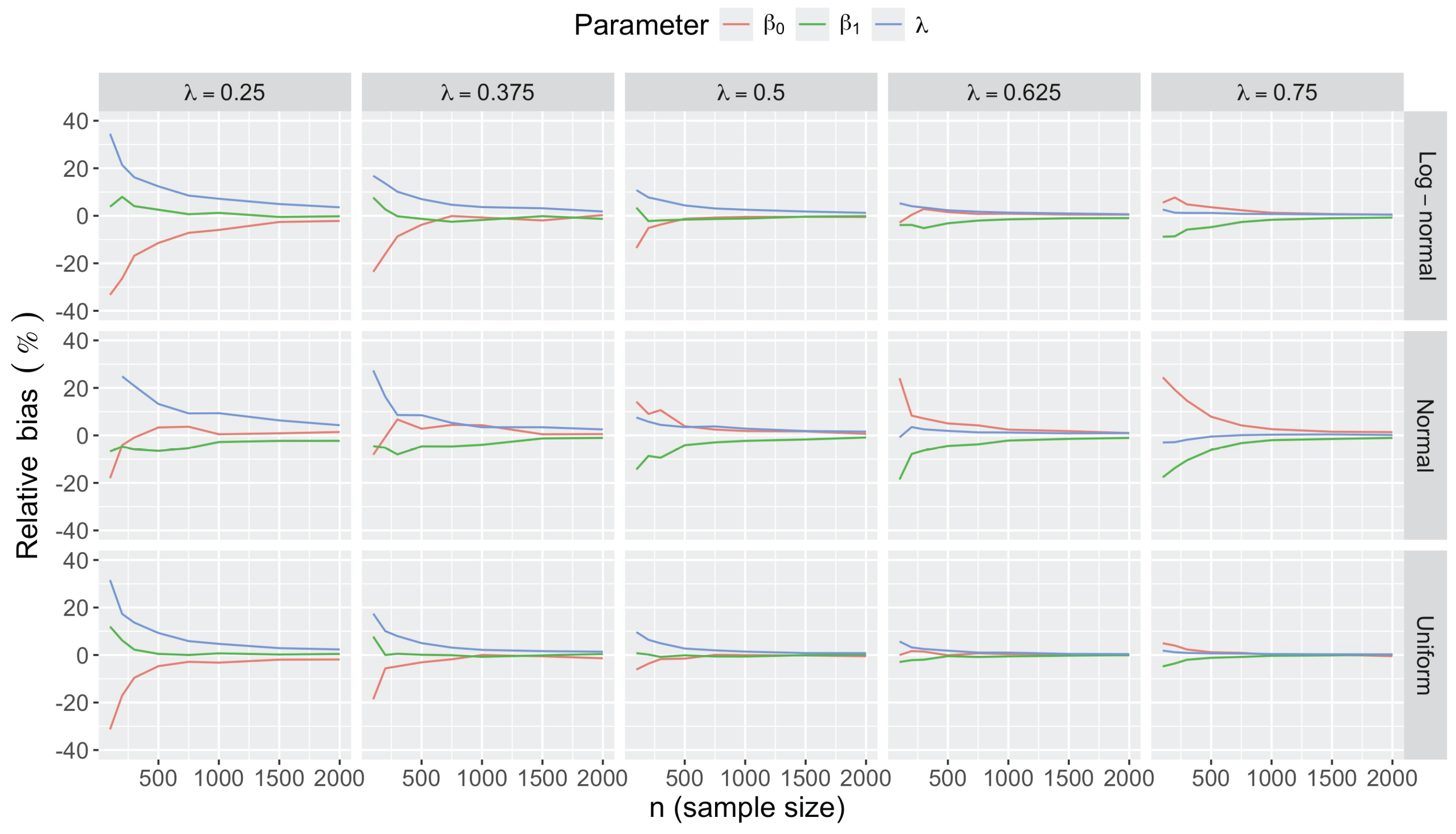

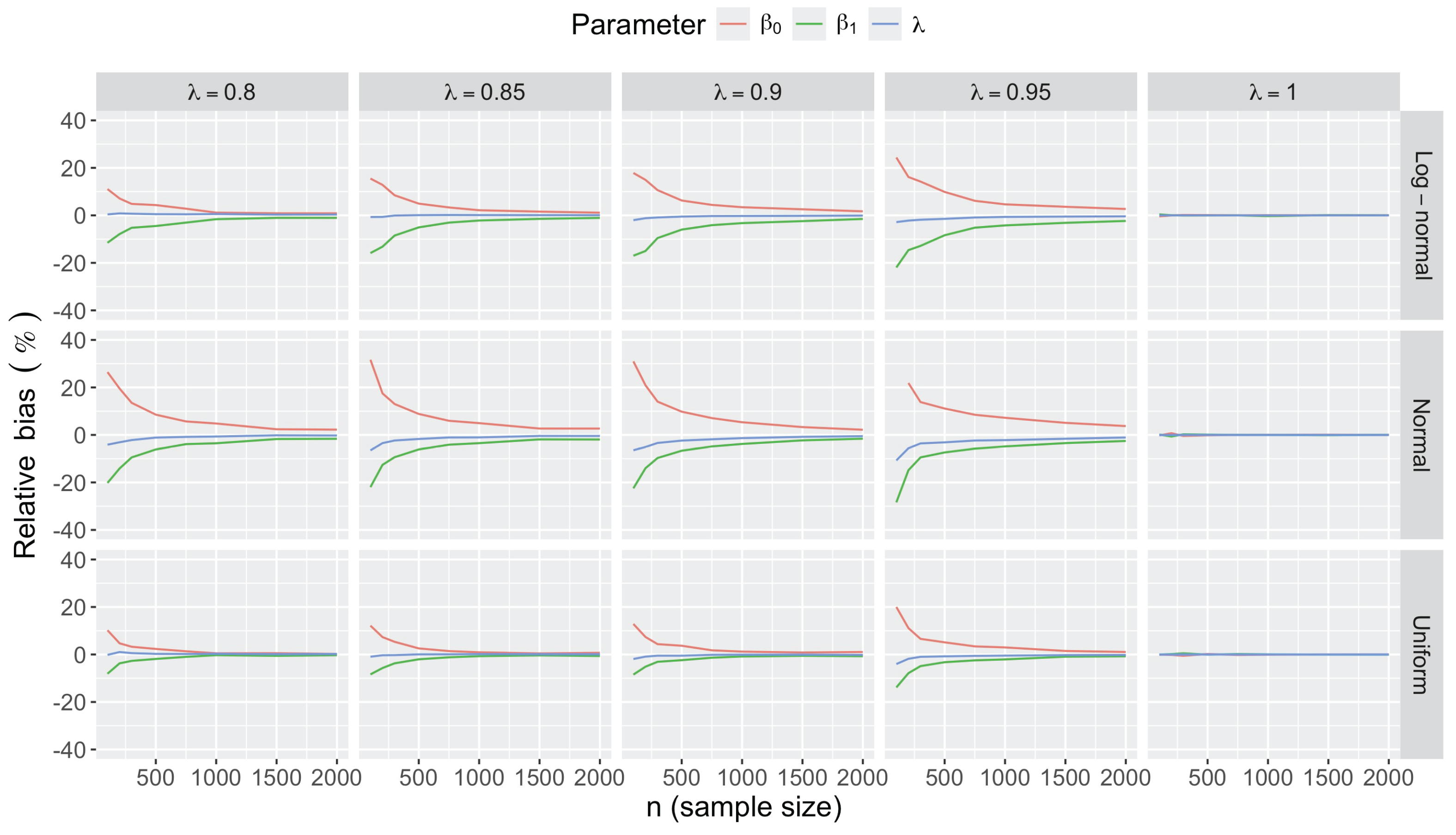

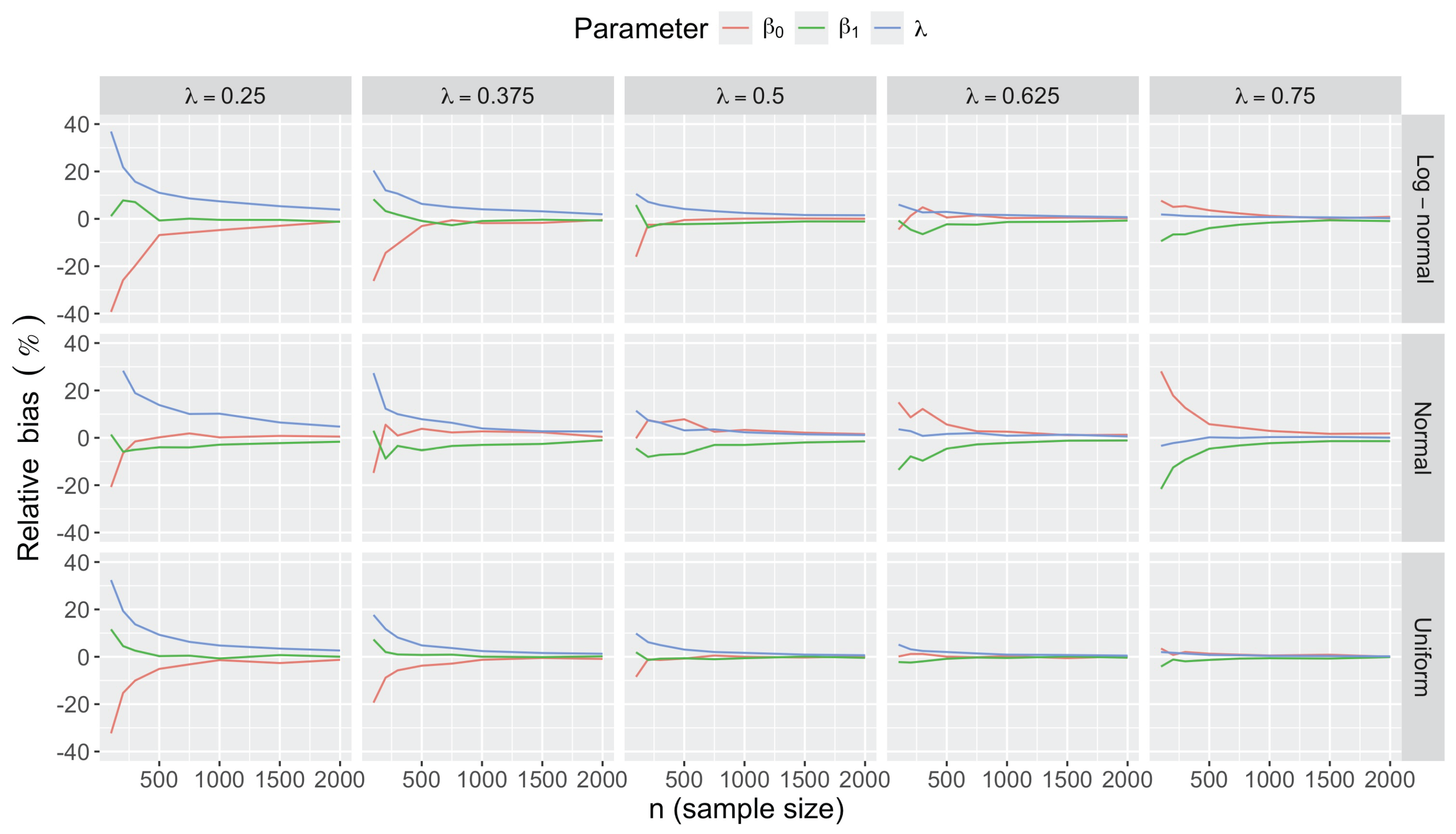

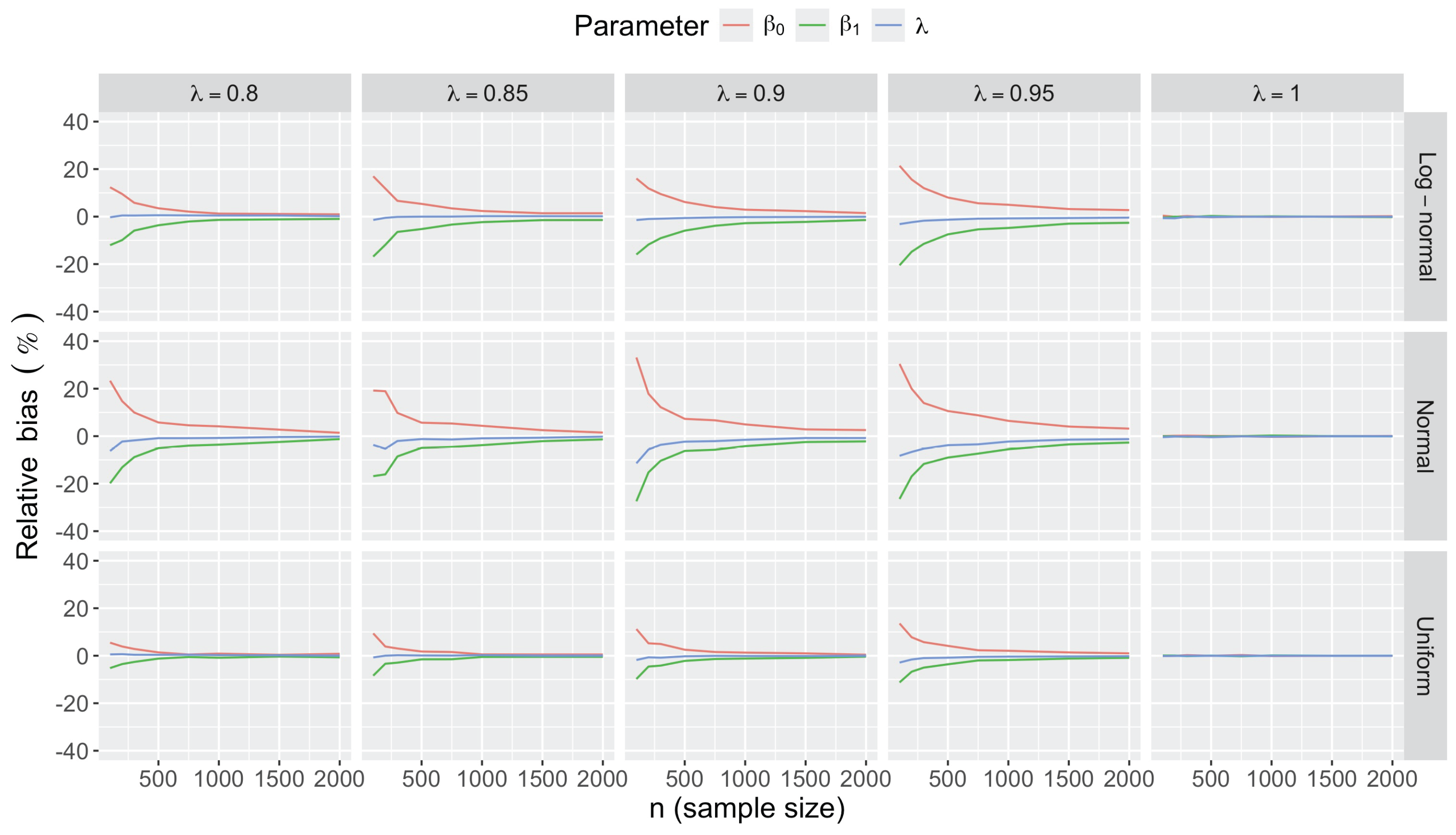

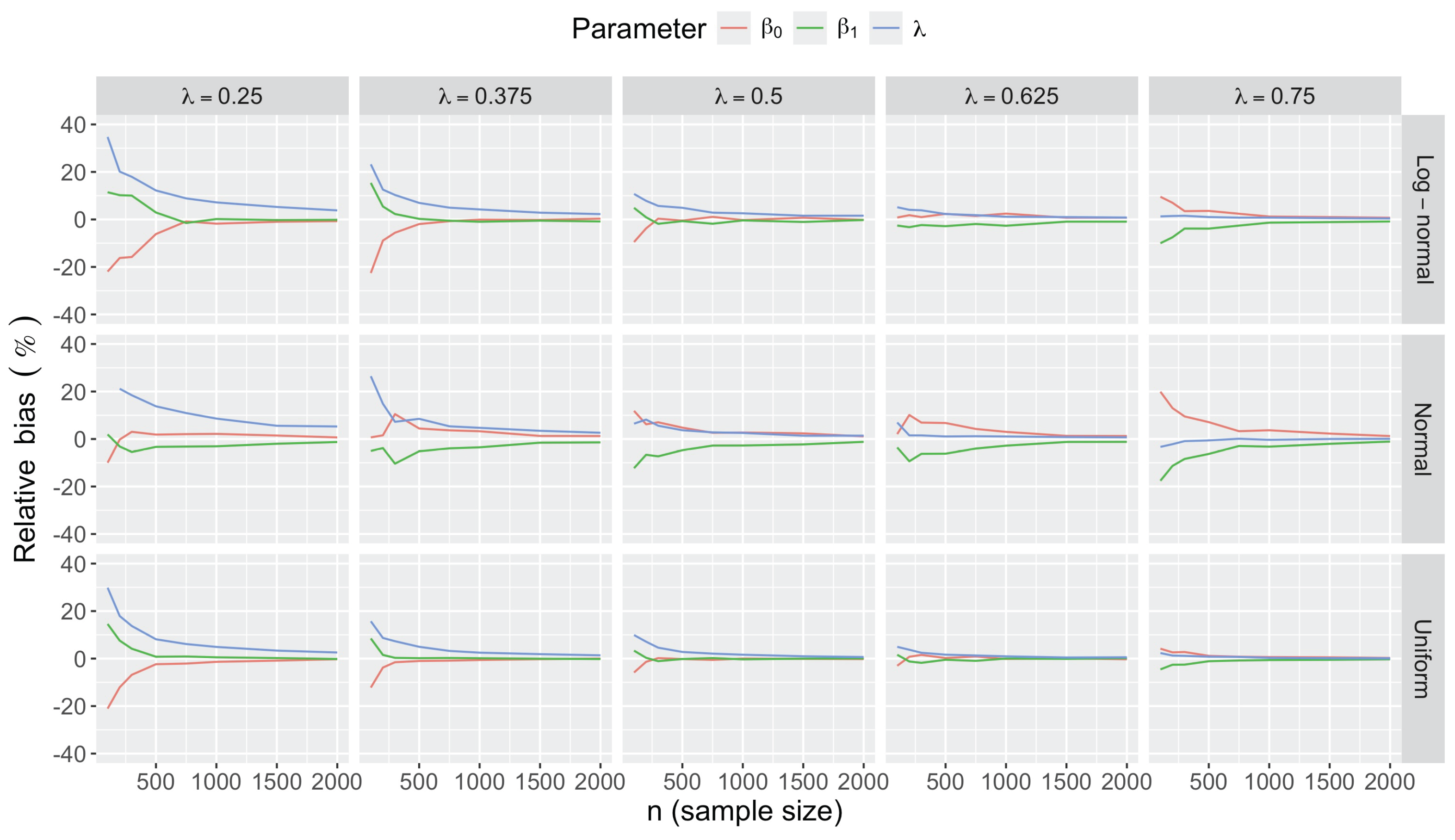

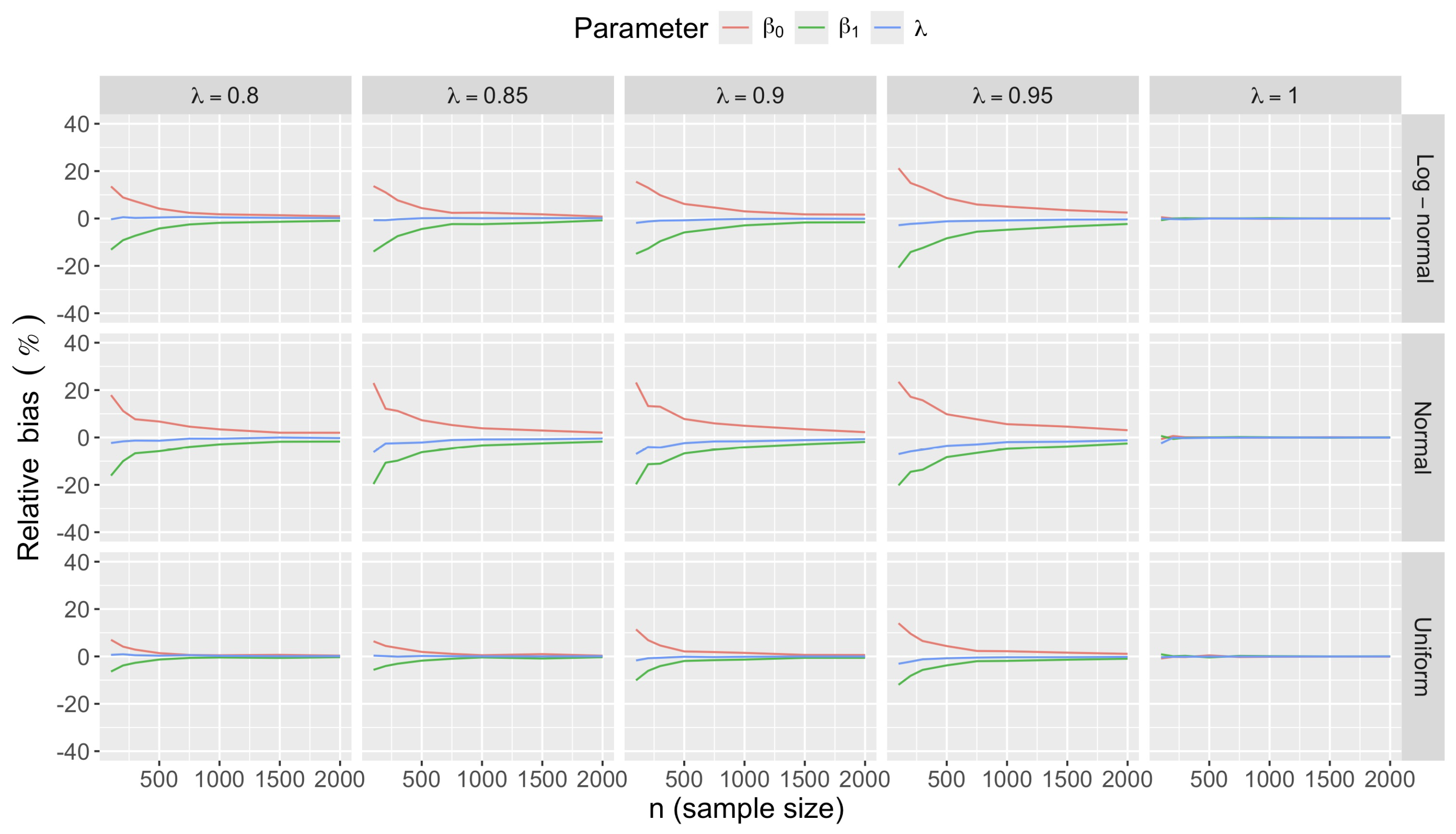

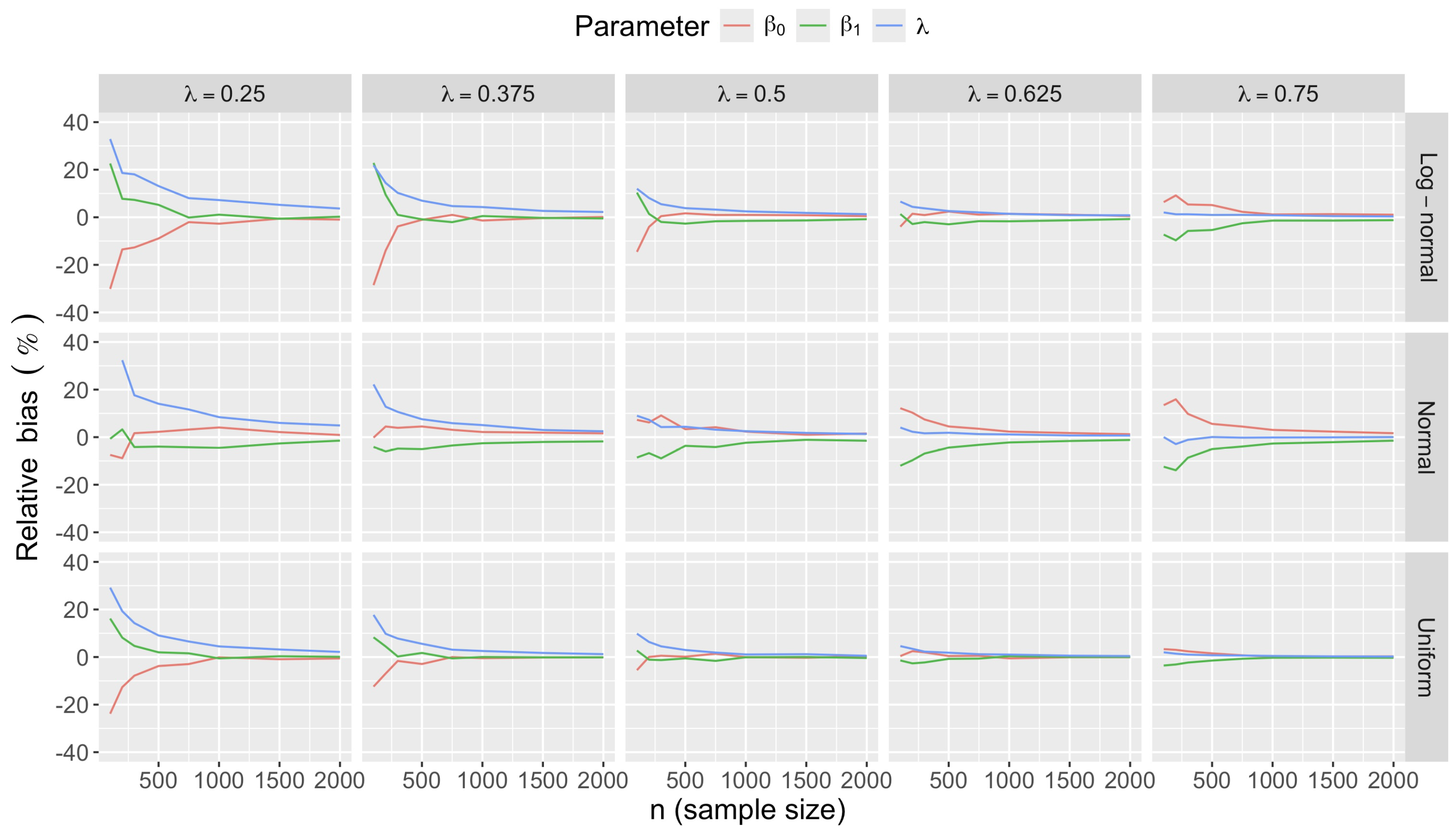

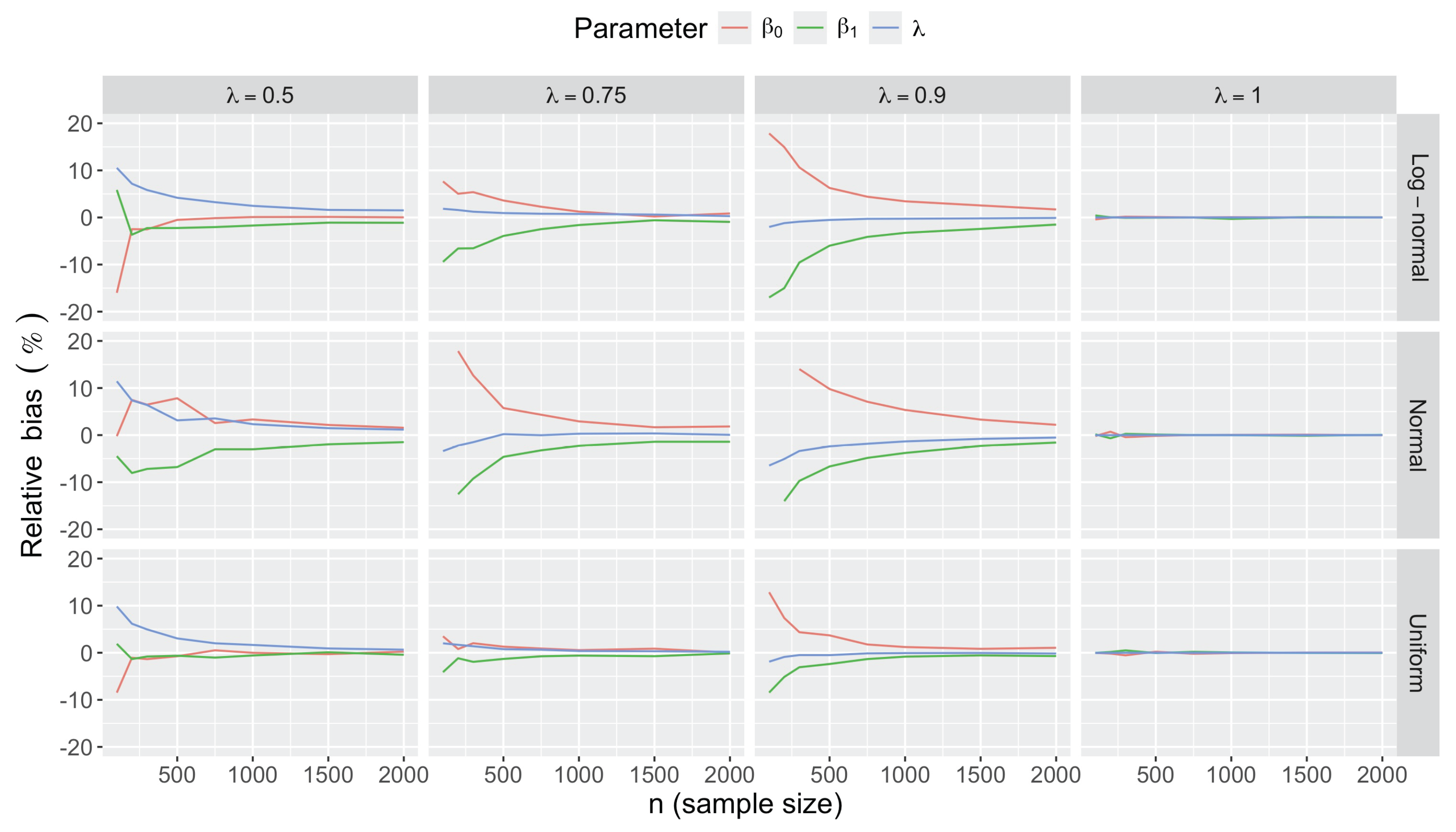

- Bias in . At , the relative of is close to zero for all considered and sample sizes . As decreases, the estimate exhibits a slight , reaching a maximum of about 10% in absolute value at when (Figure 2). We notice a pattern in the : under a uniform for instance, the is negative at and positive for . Additional simulations with values down to 0.25 (see Appendix C) reveal that under a uniform or log-normal , the in is negative (under-estimation) for high values (), essentially zero for medium values (), and positive (over-estimation) for low values (). For the normal , the pattern persists, but the is negative for .

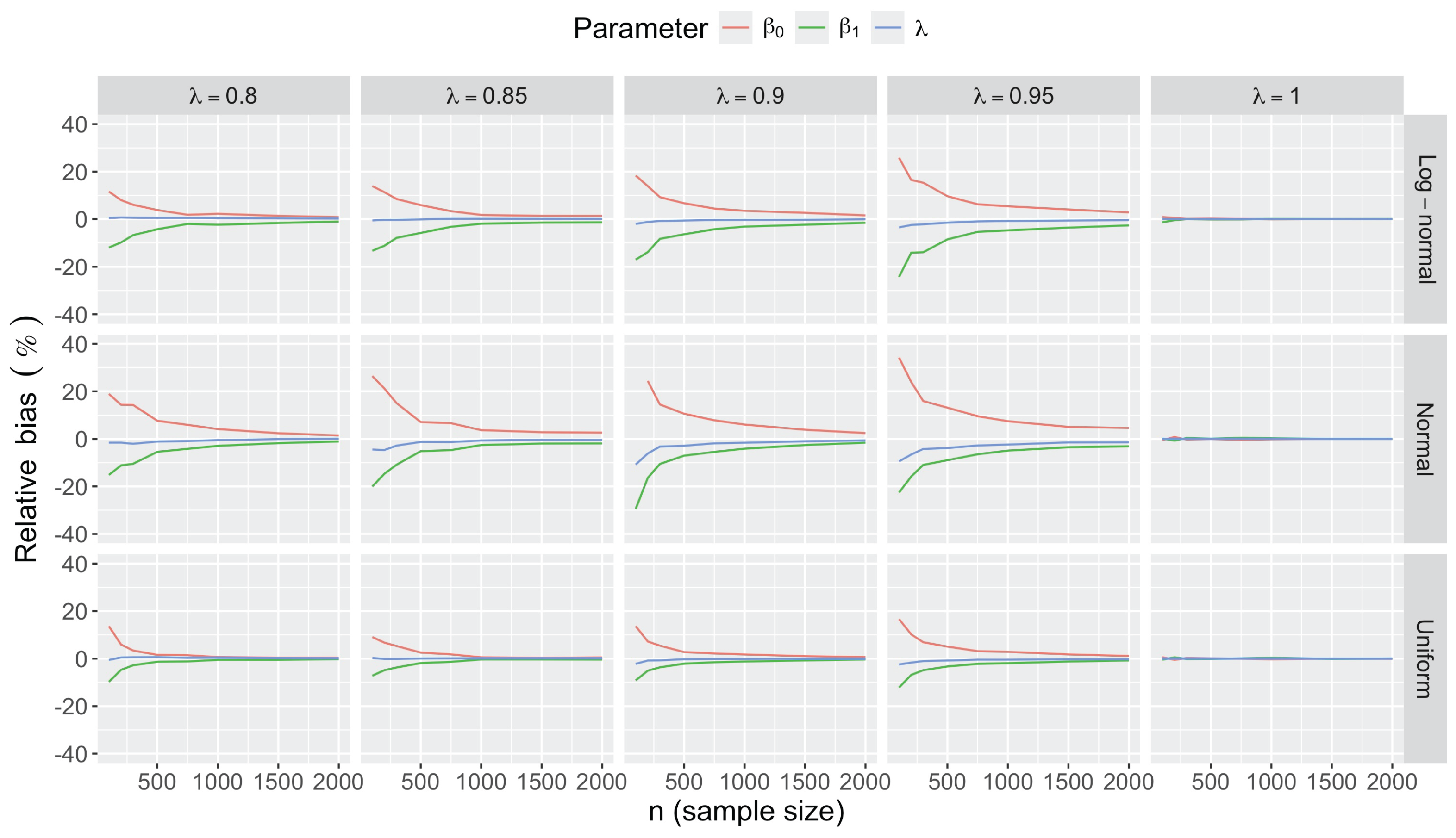

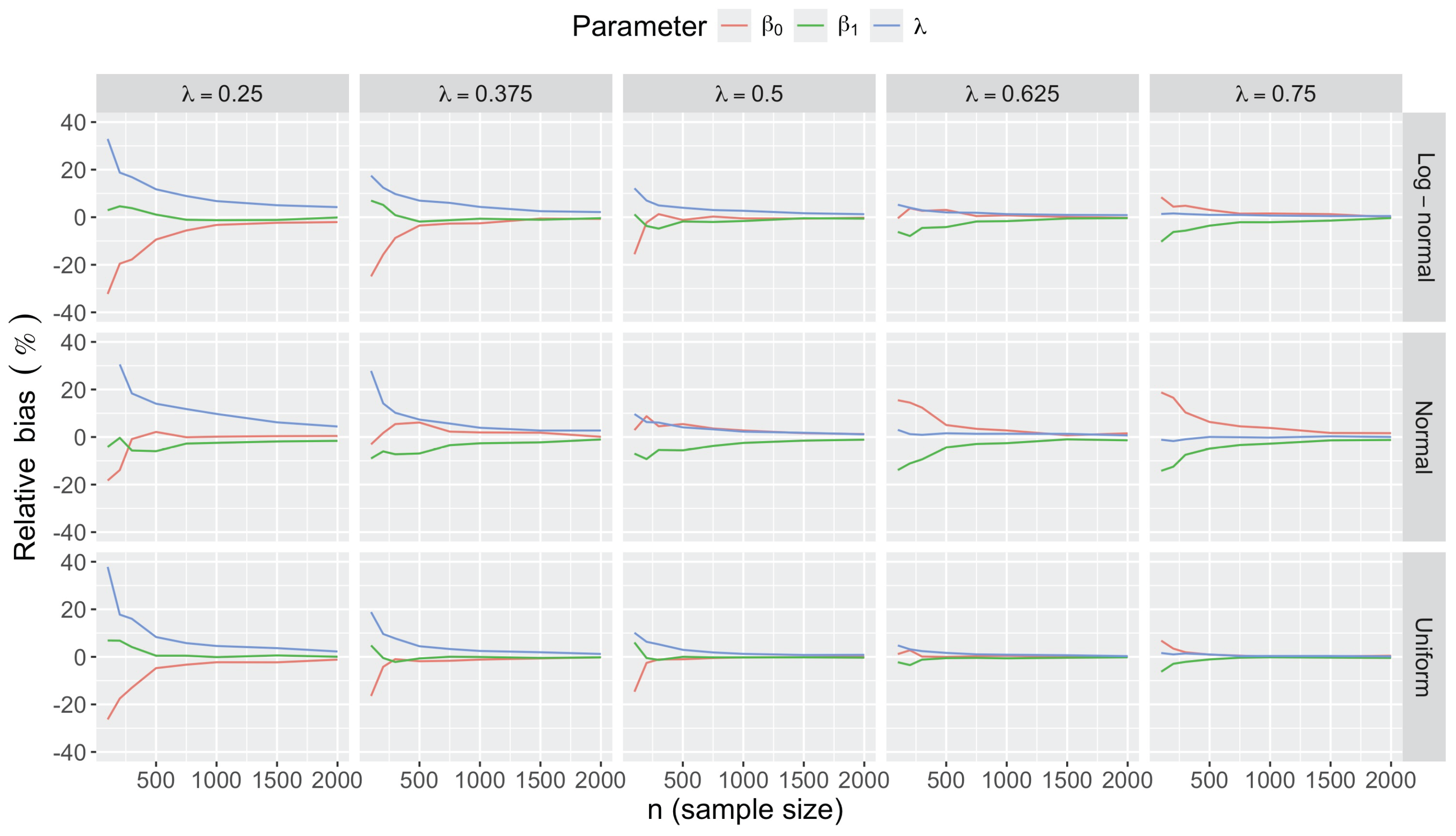

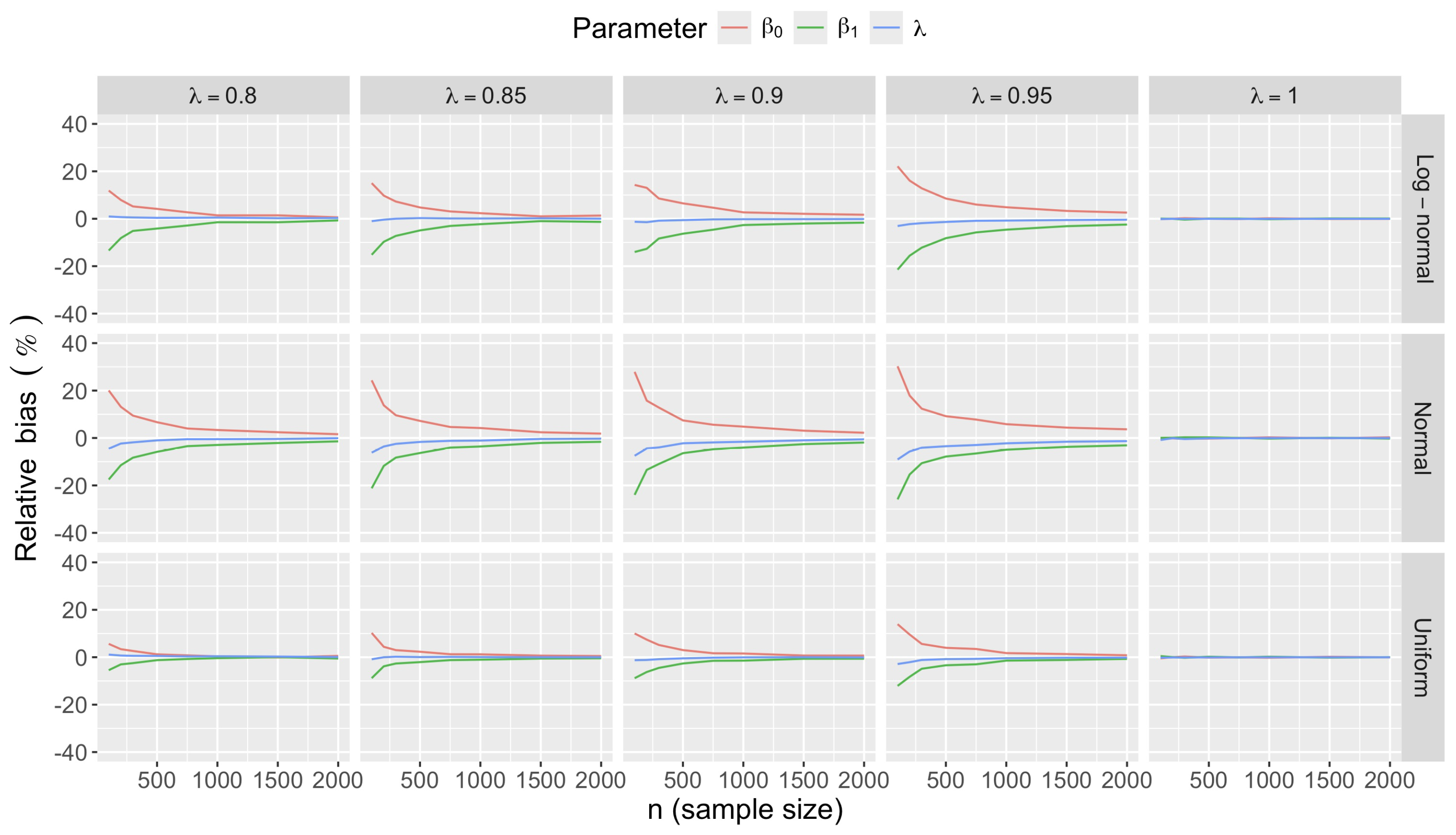

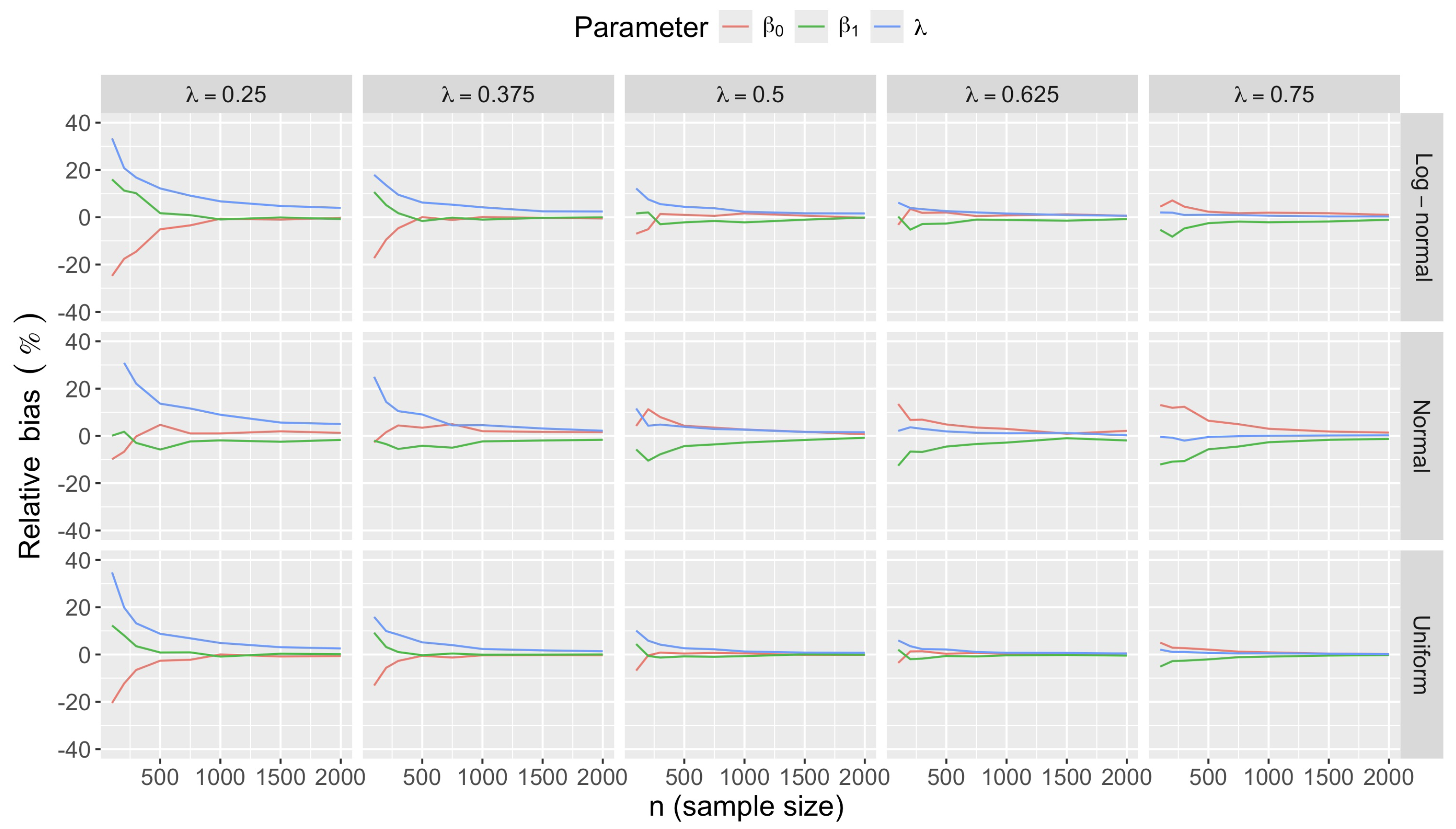

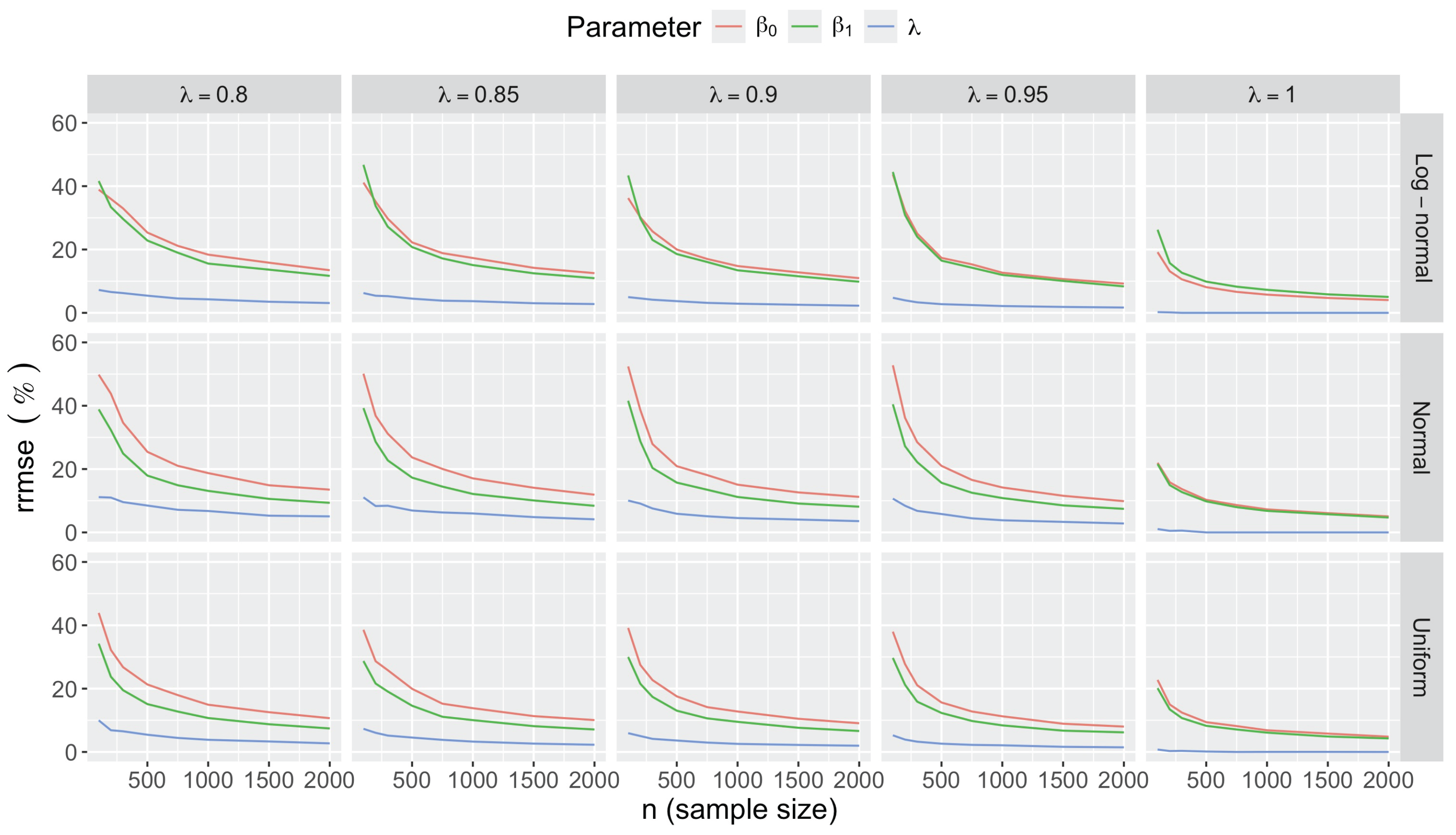

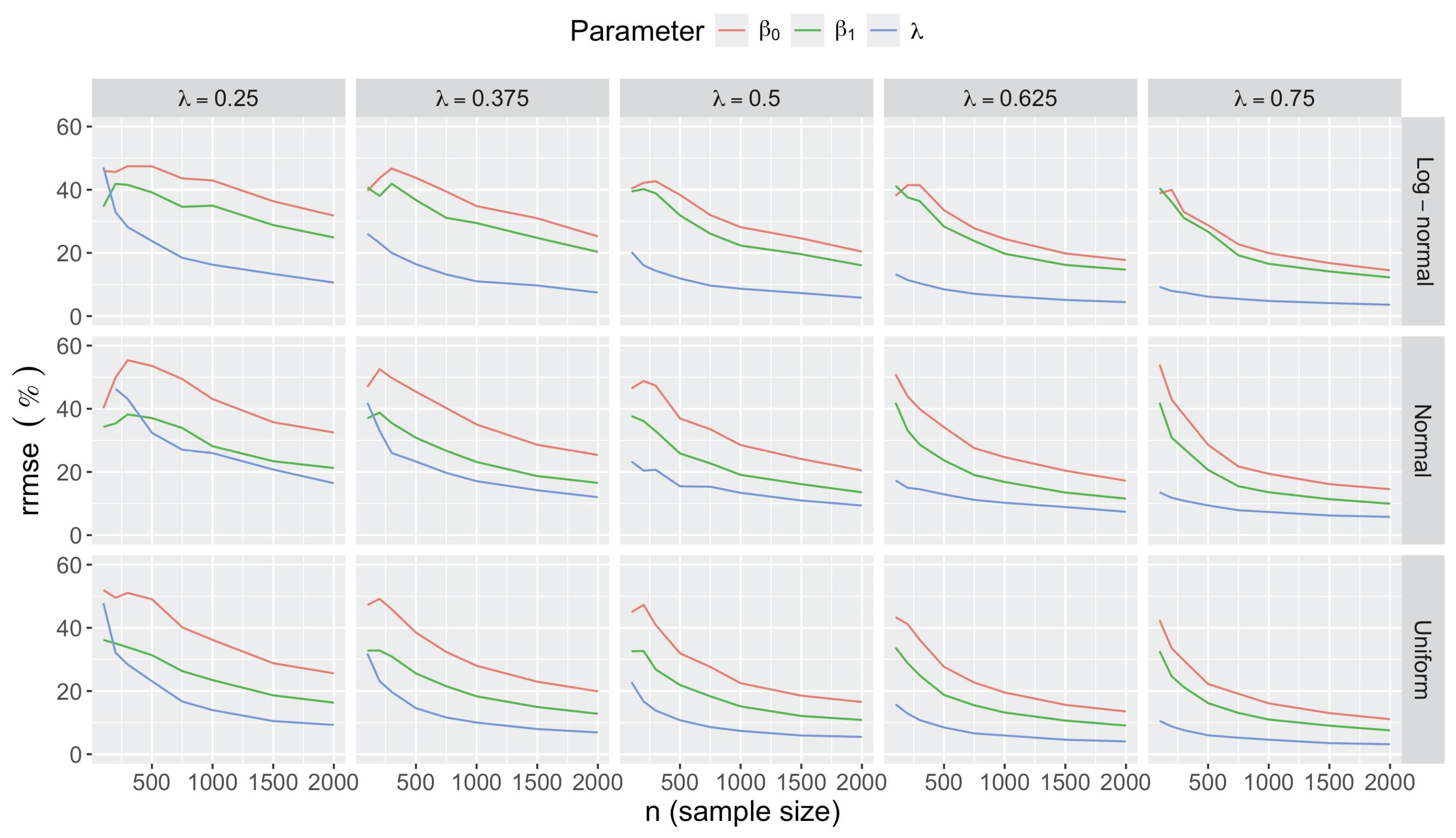

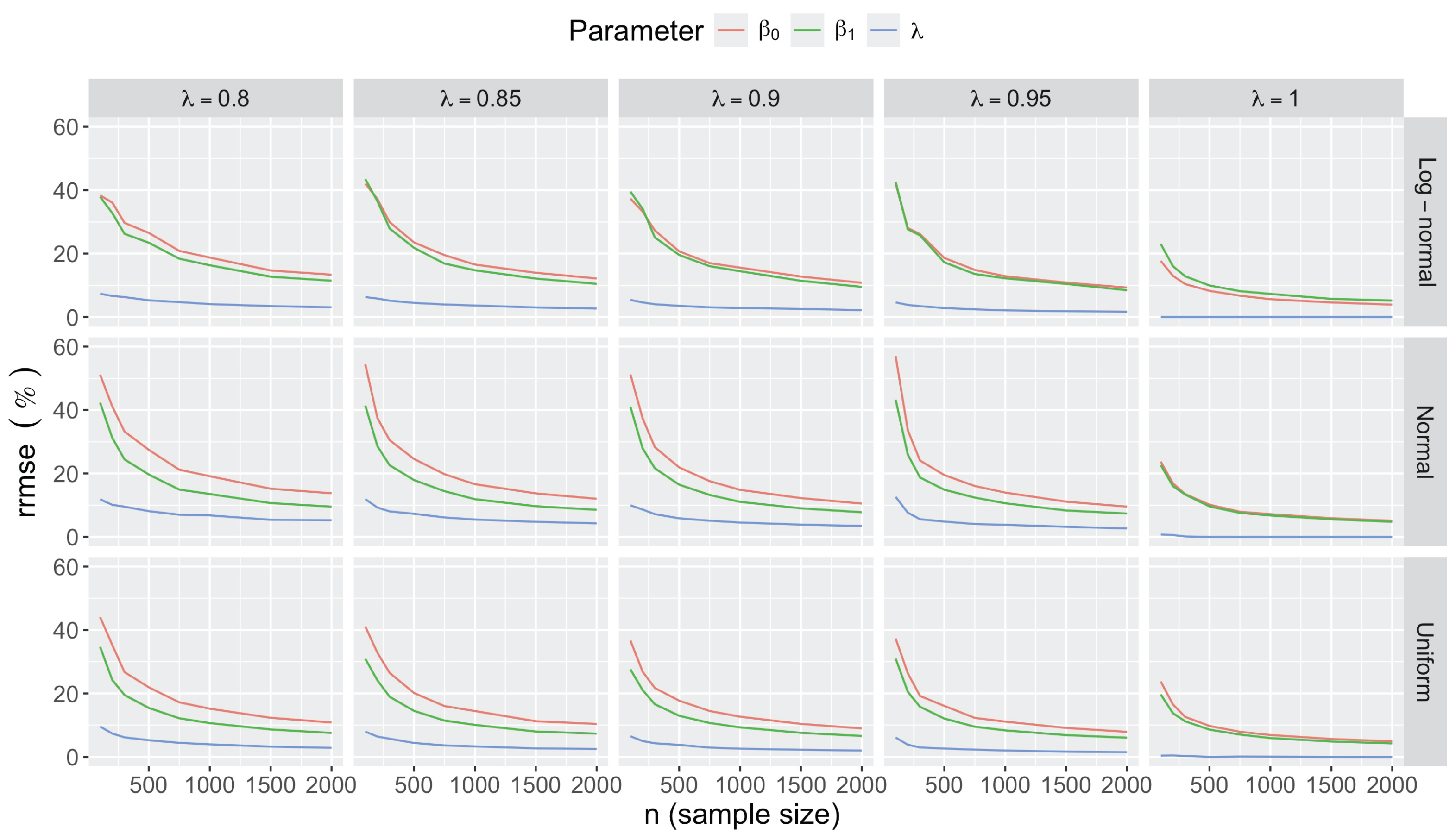

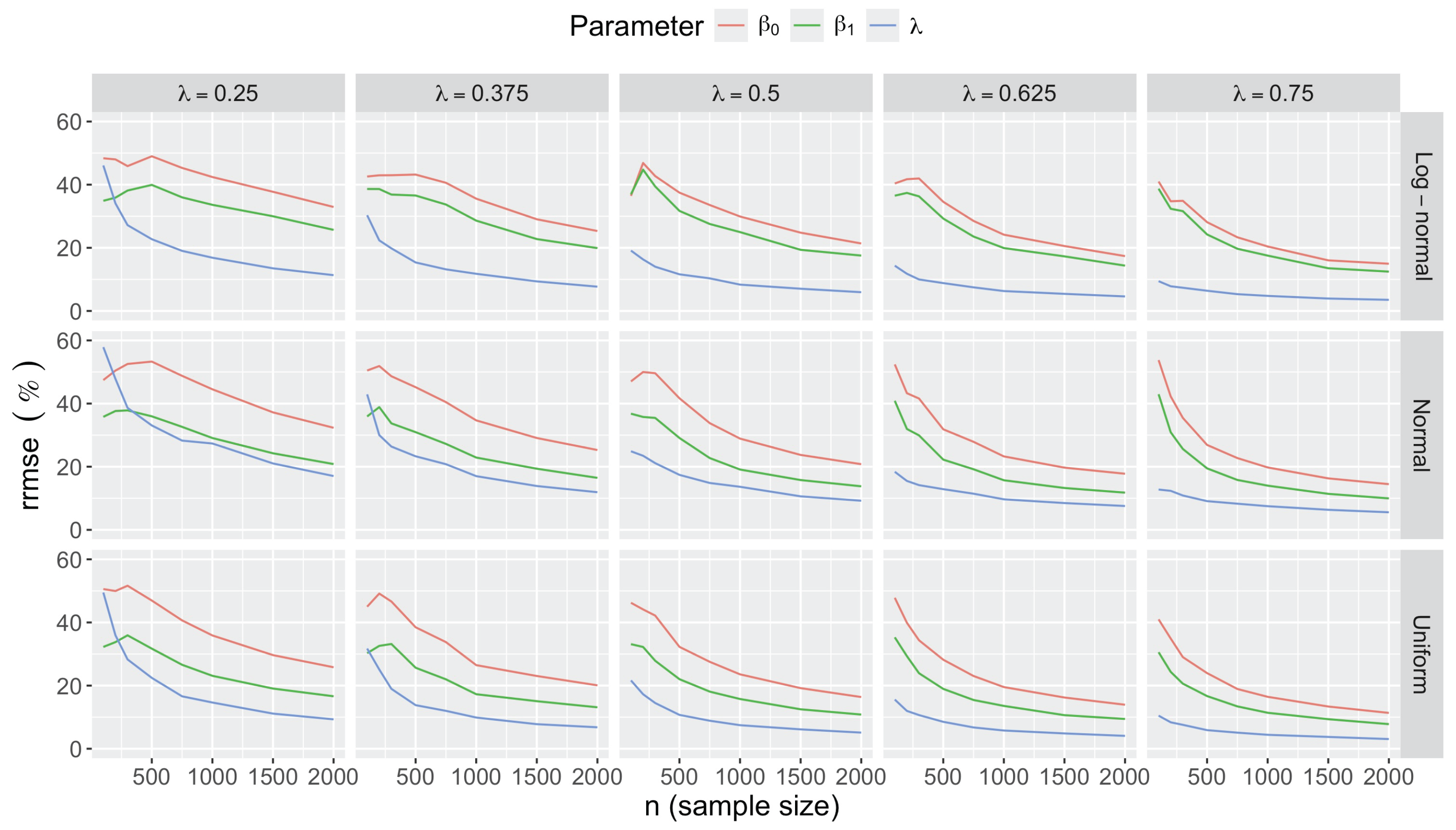

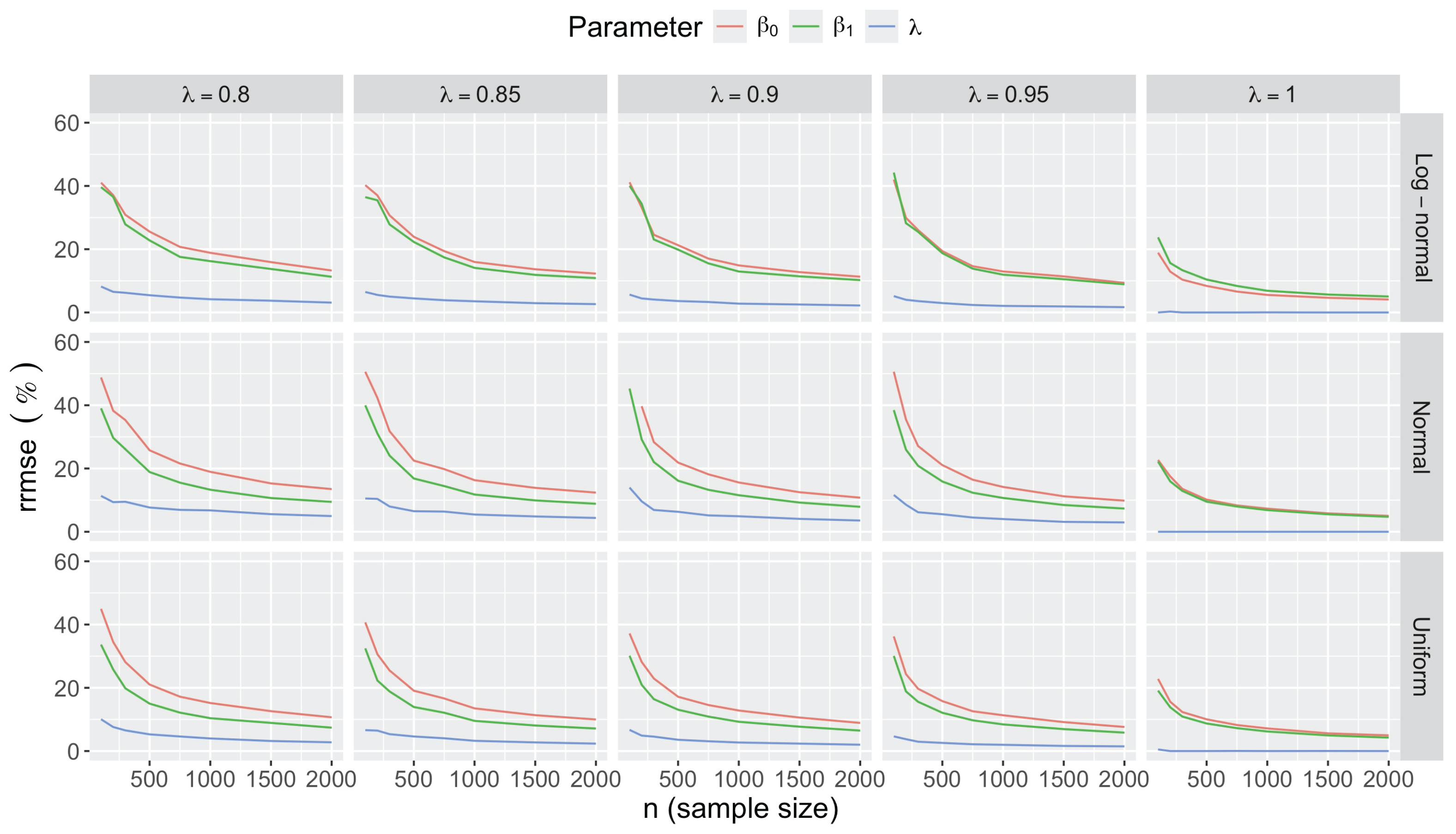

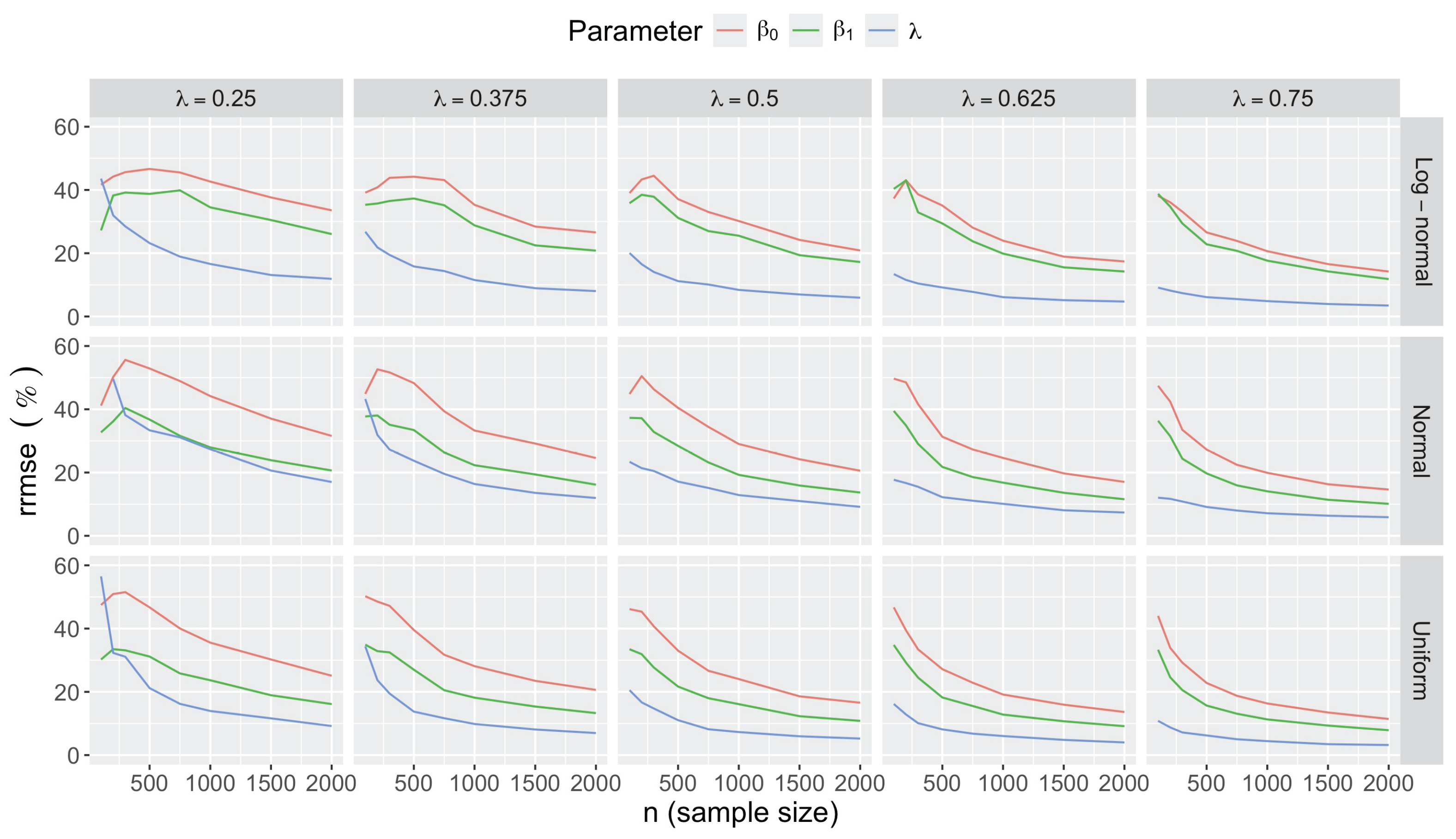

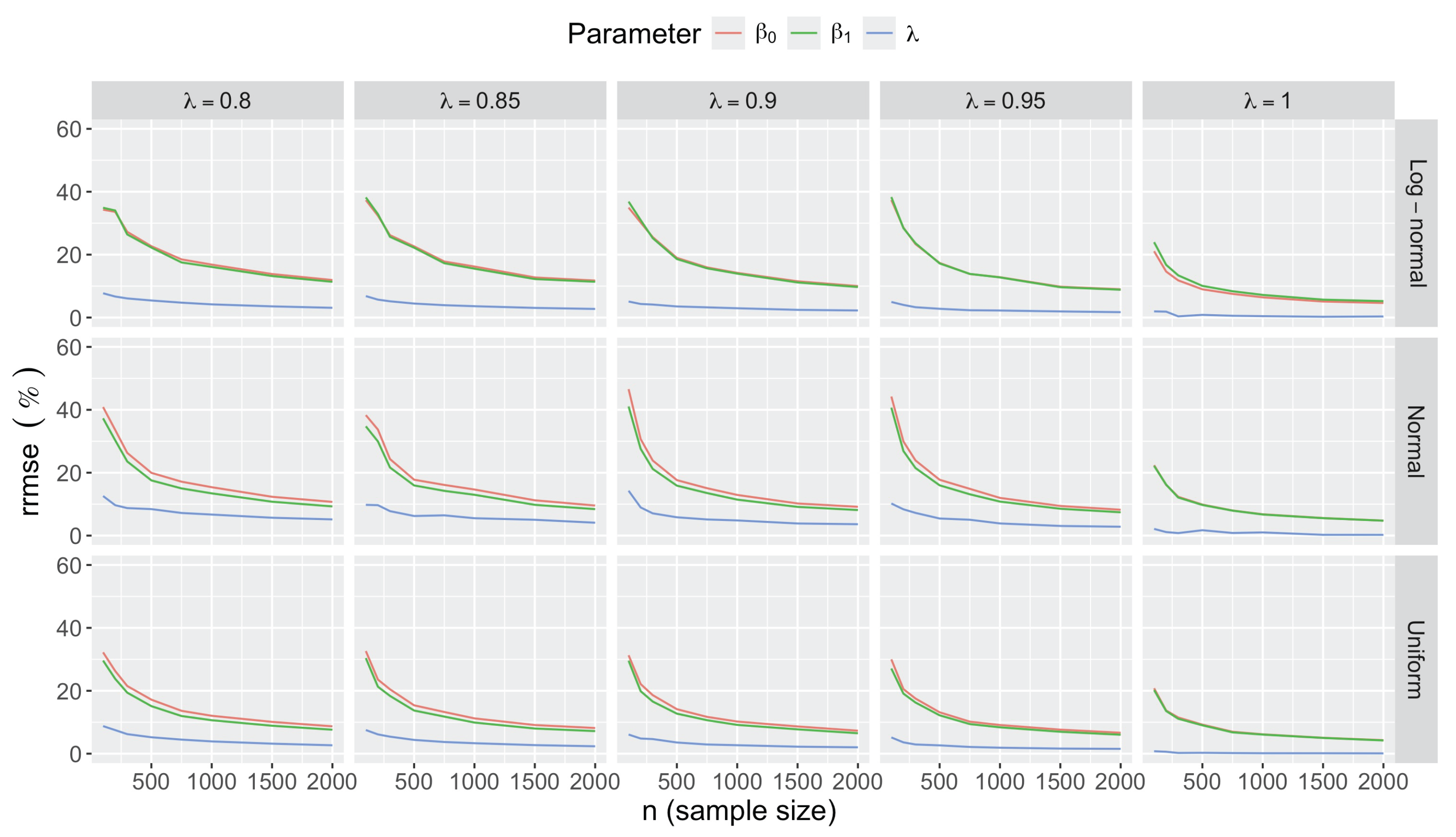

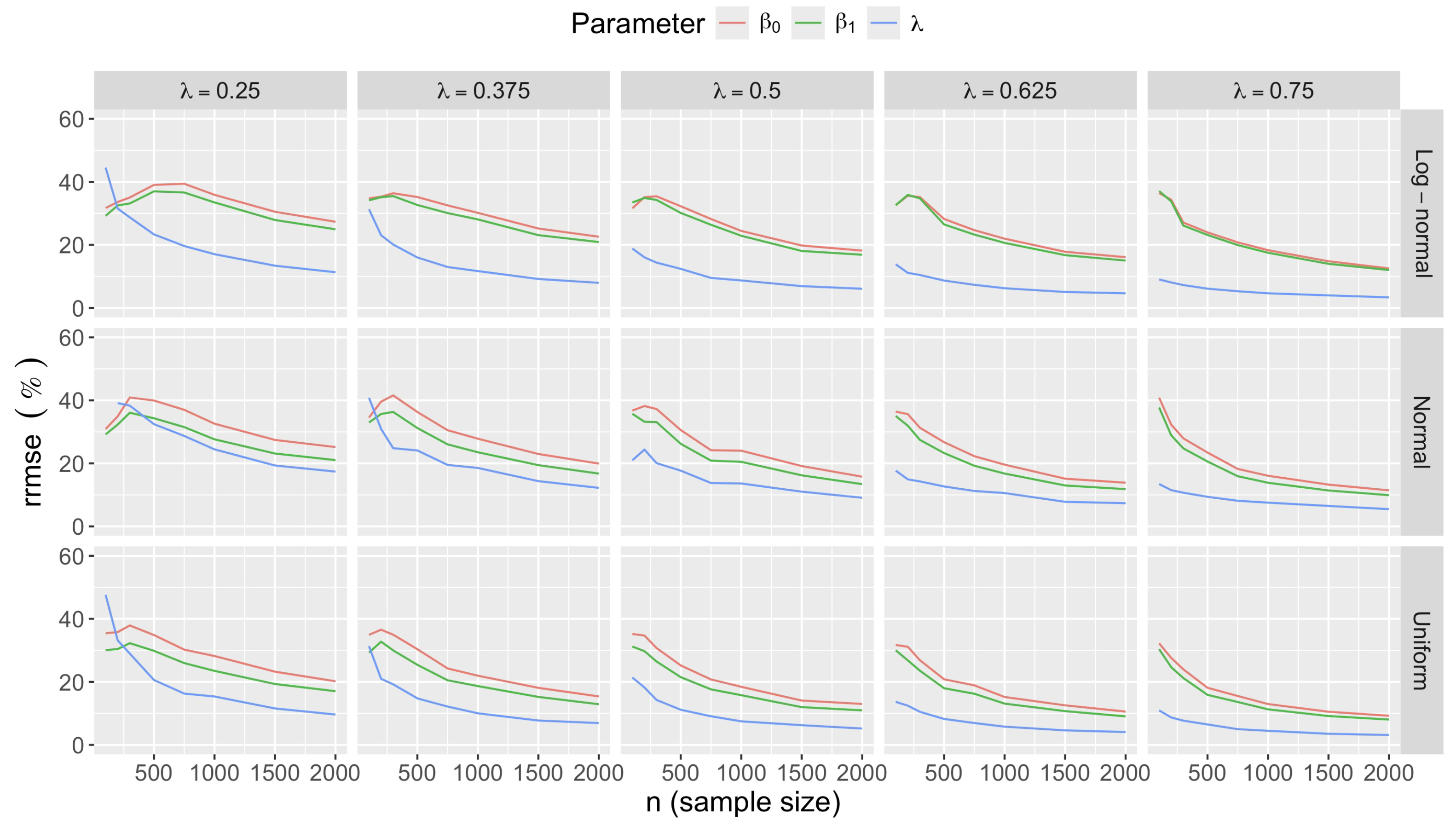

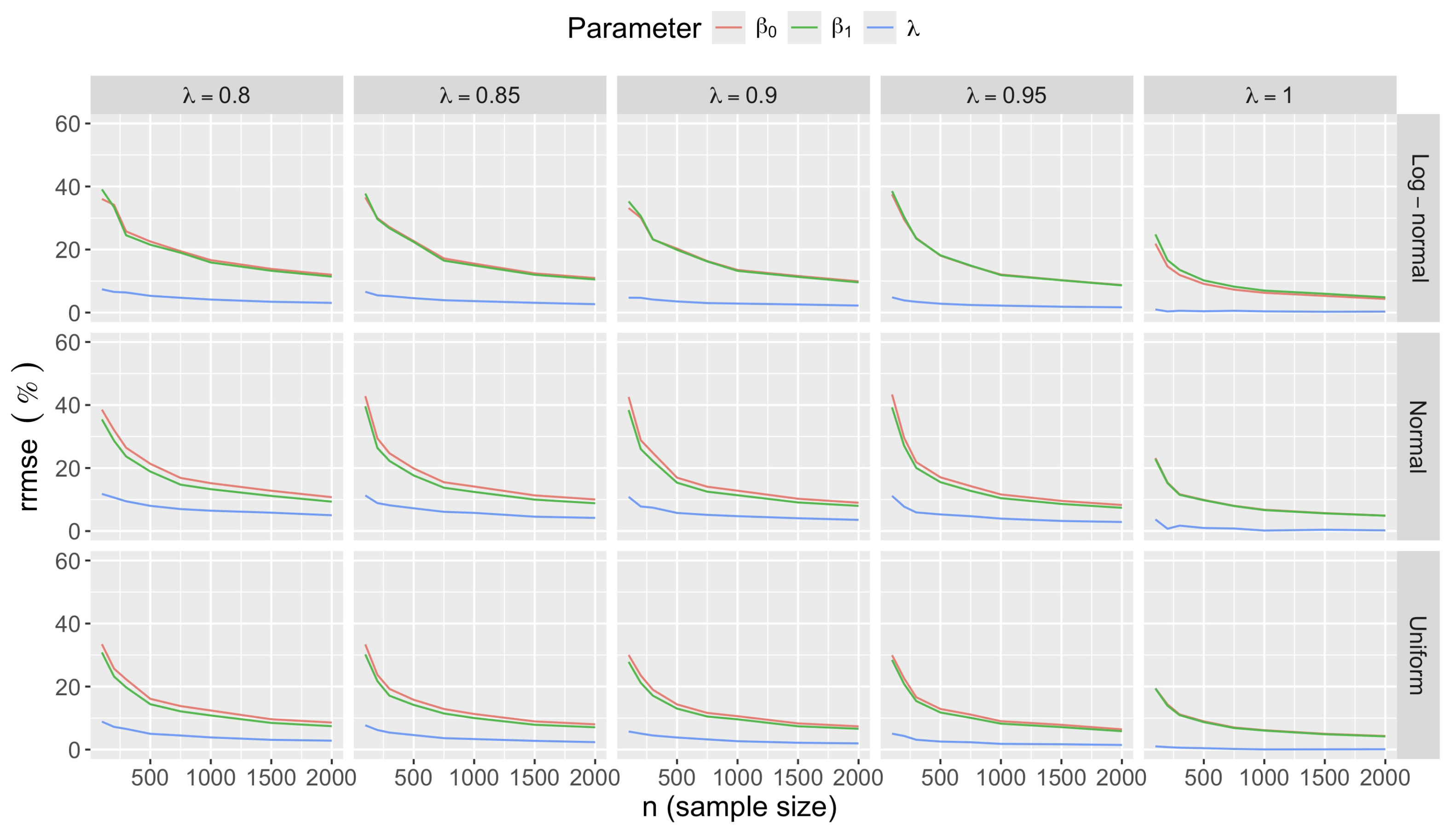

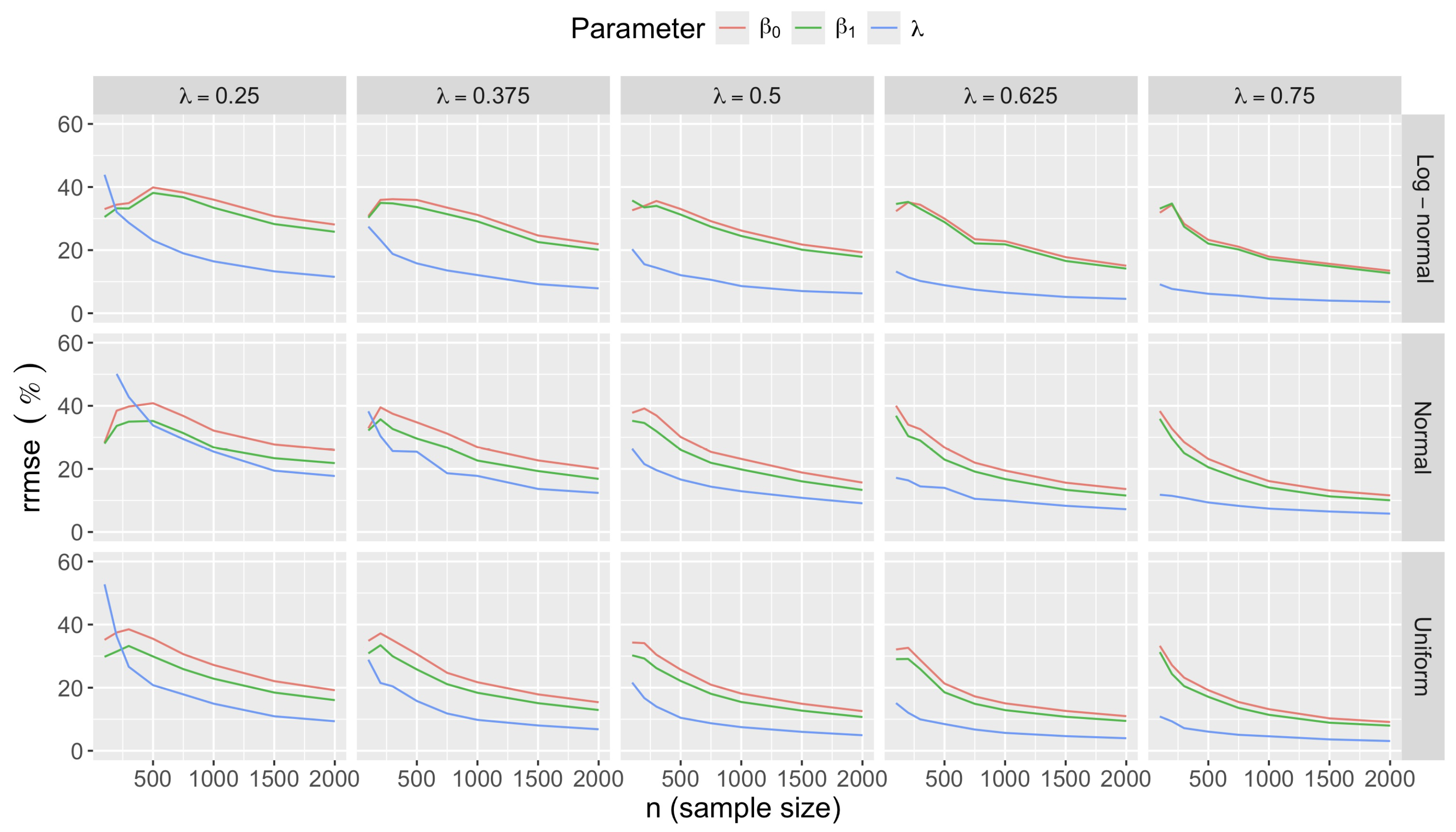

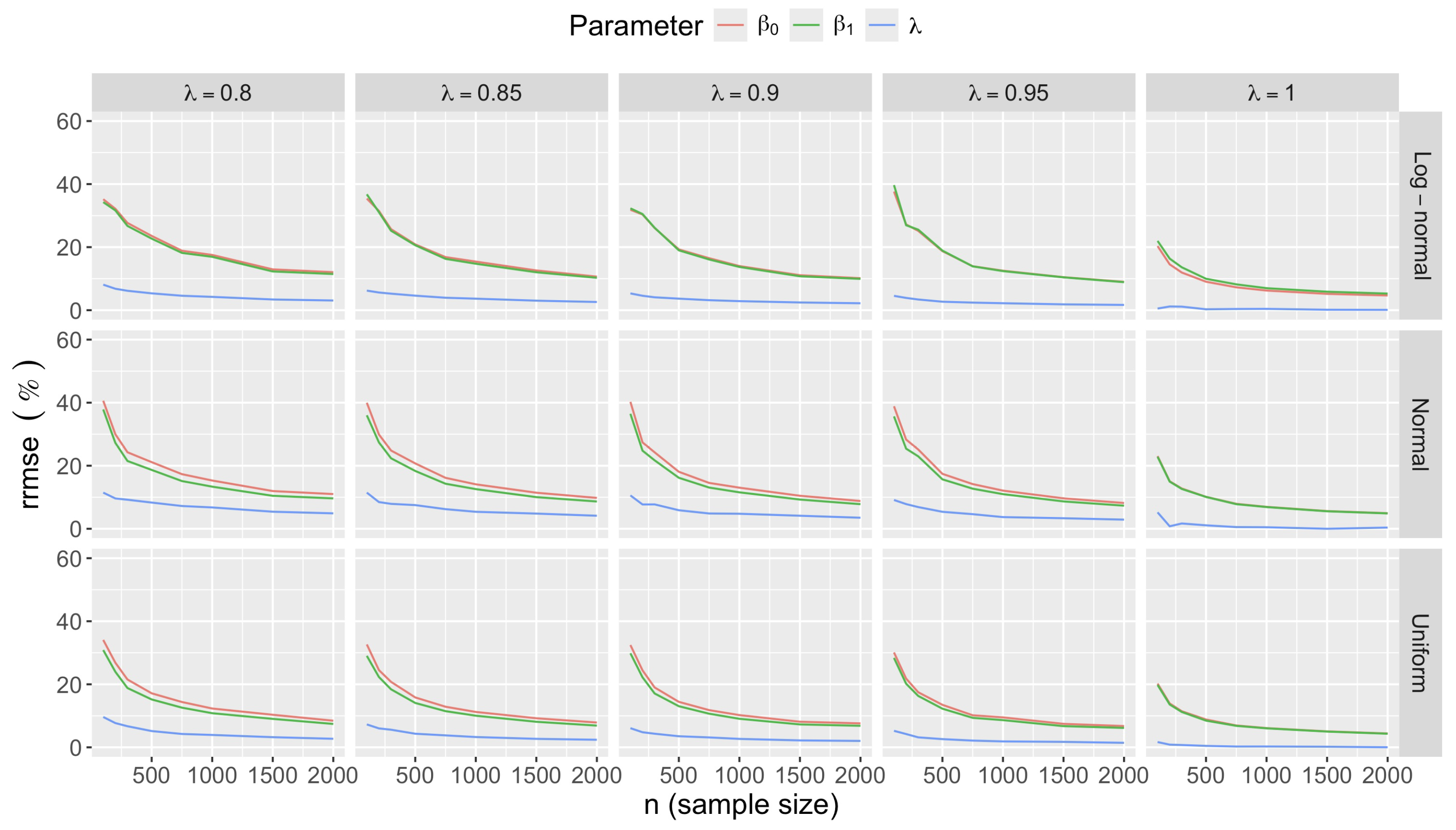

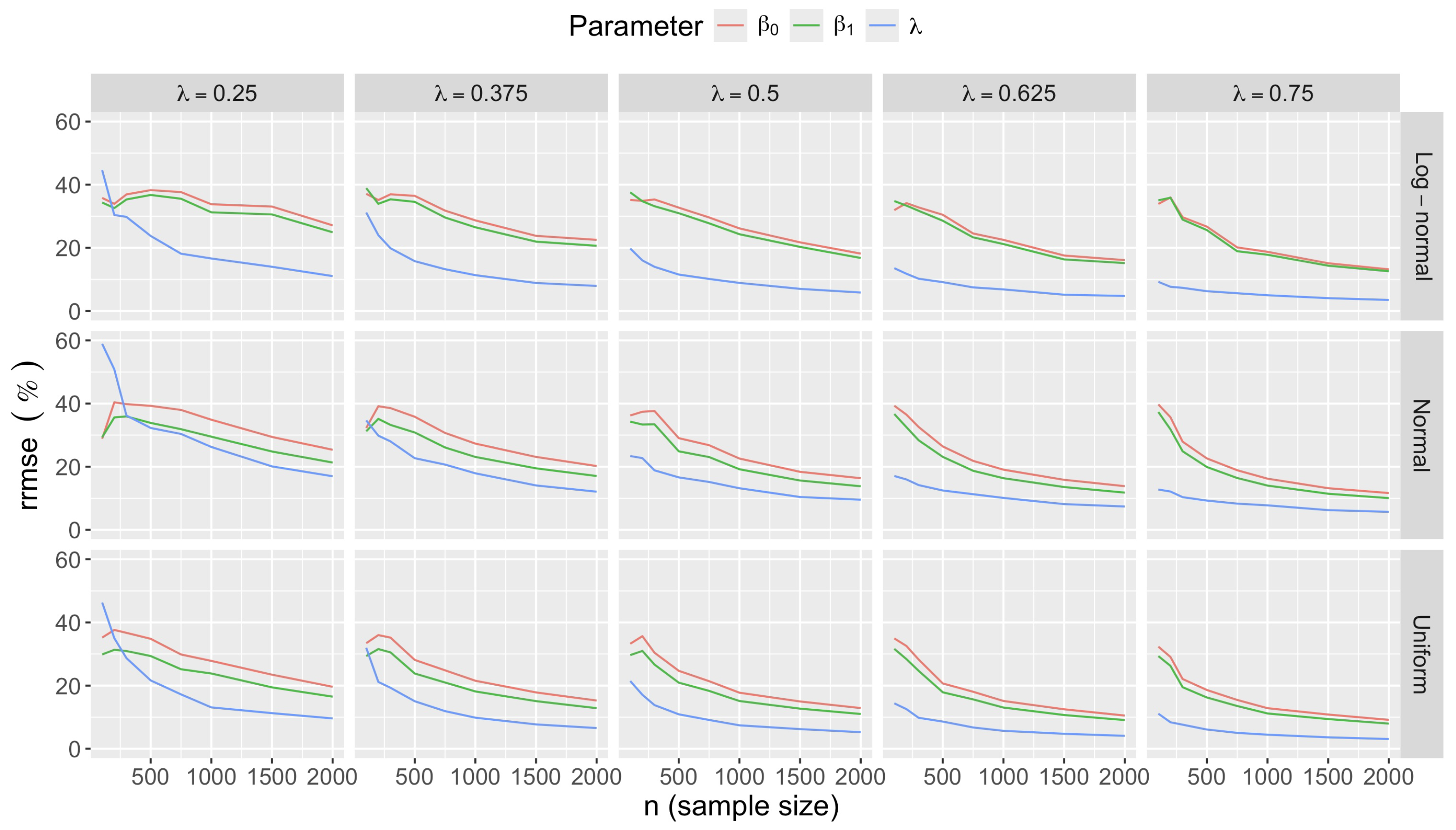

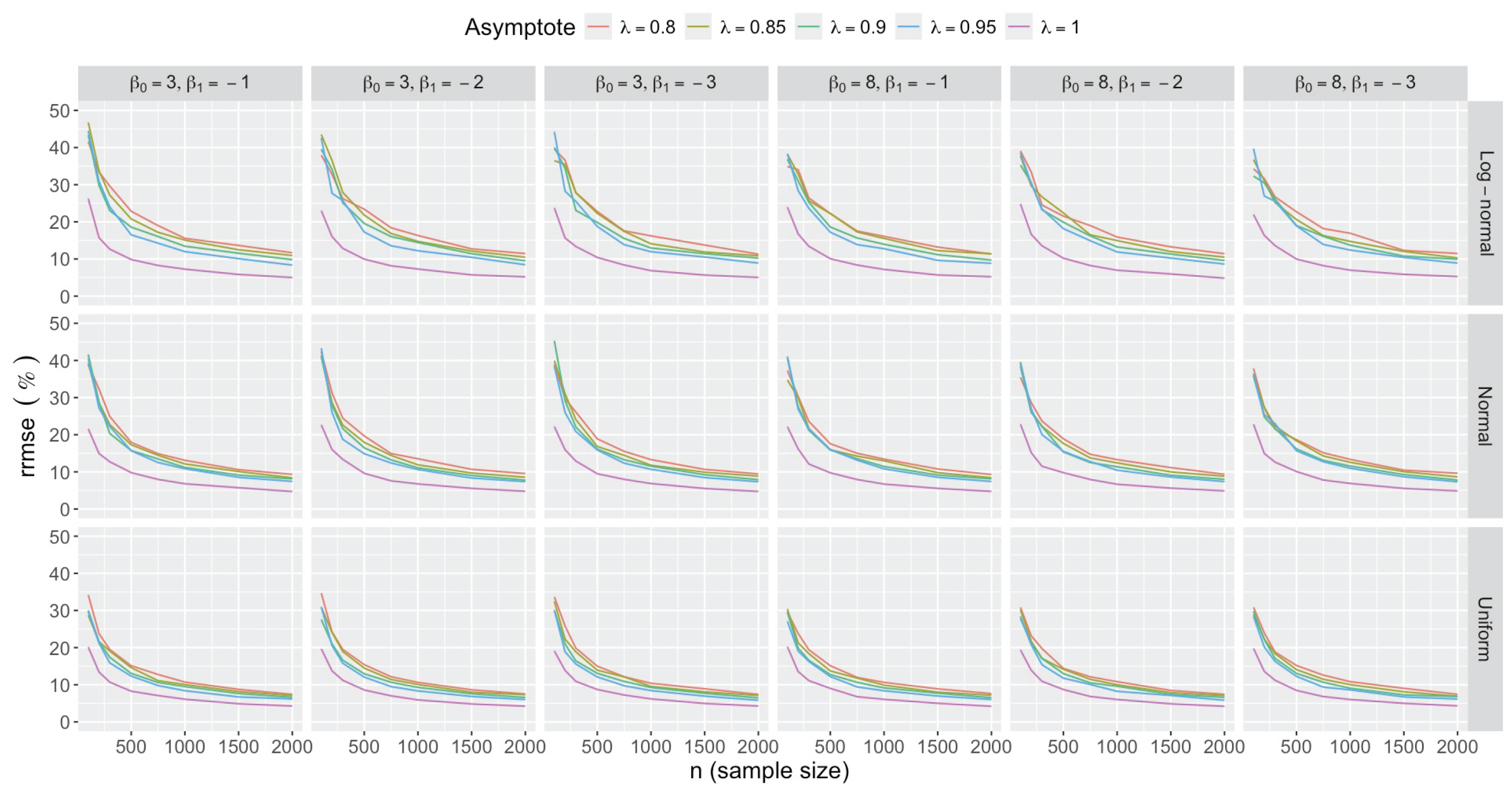

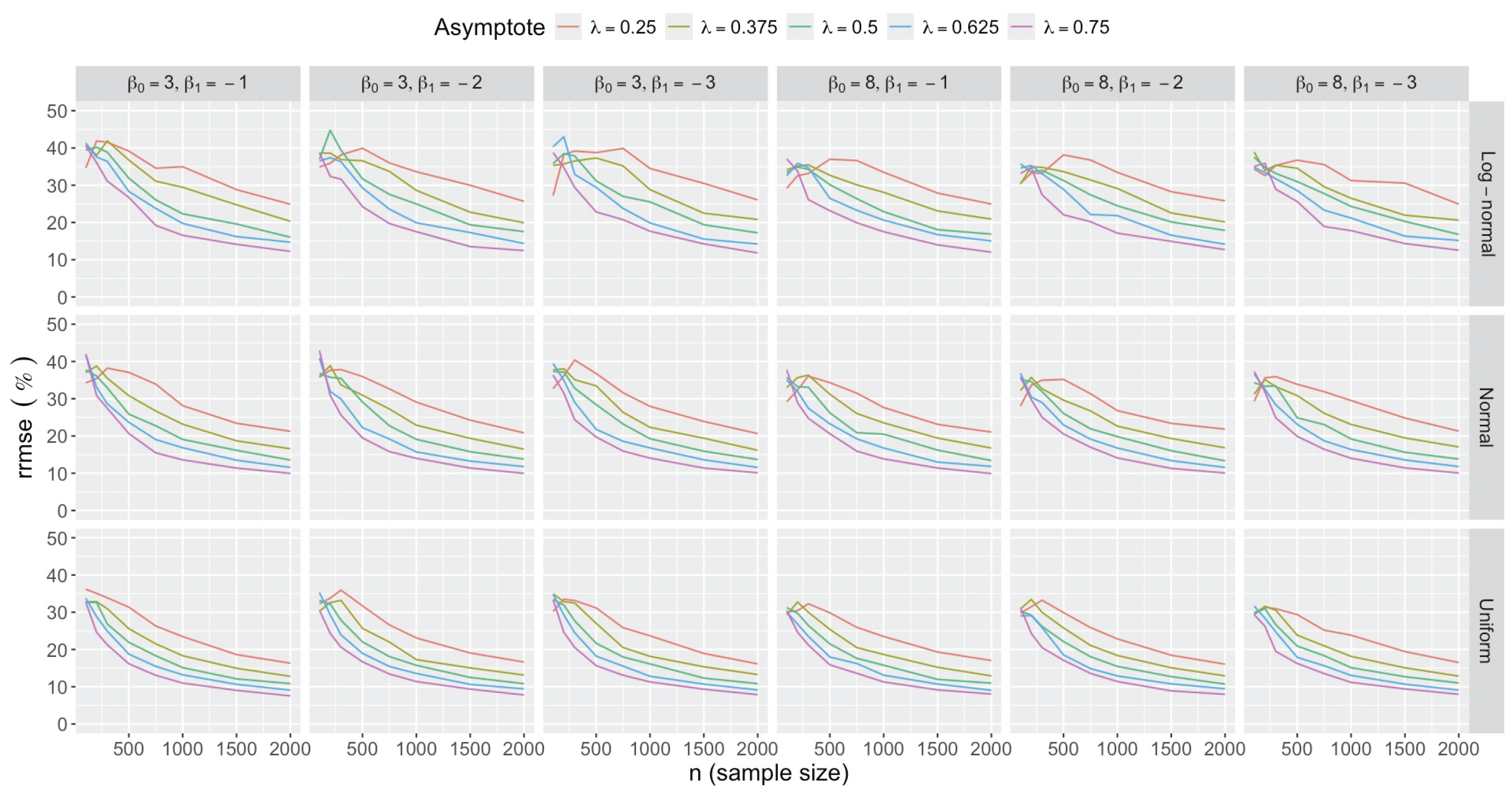

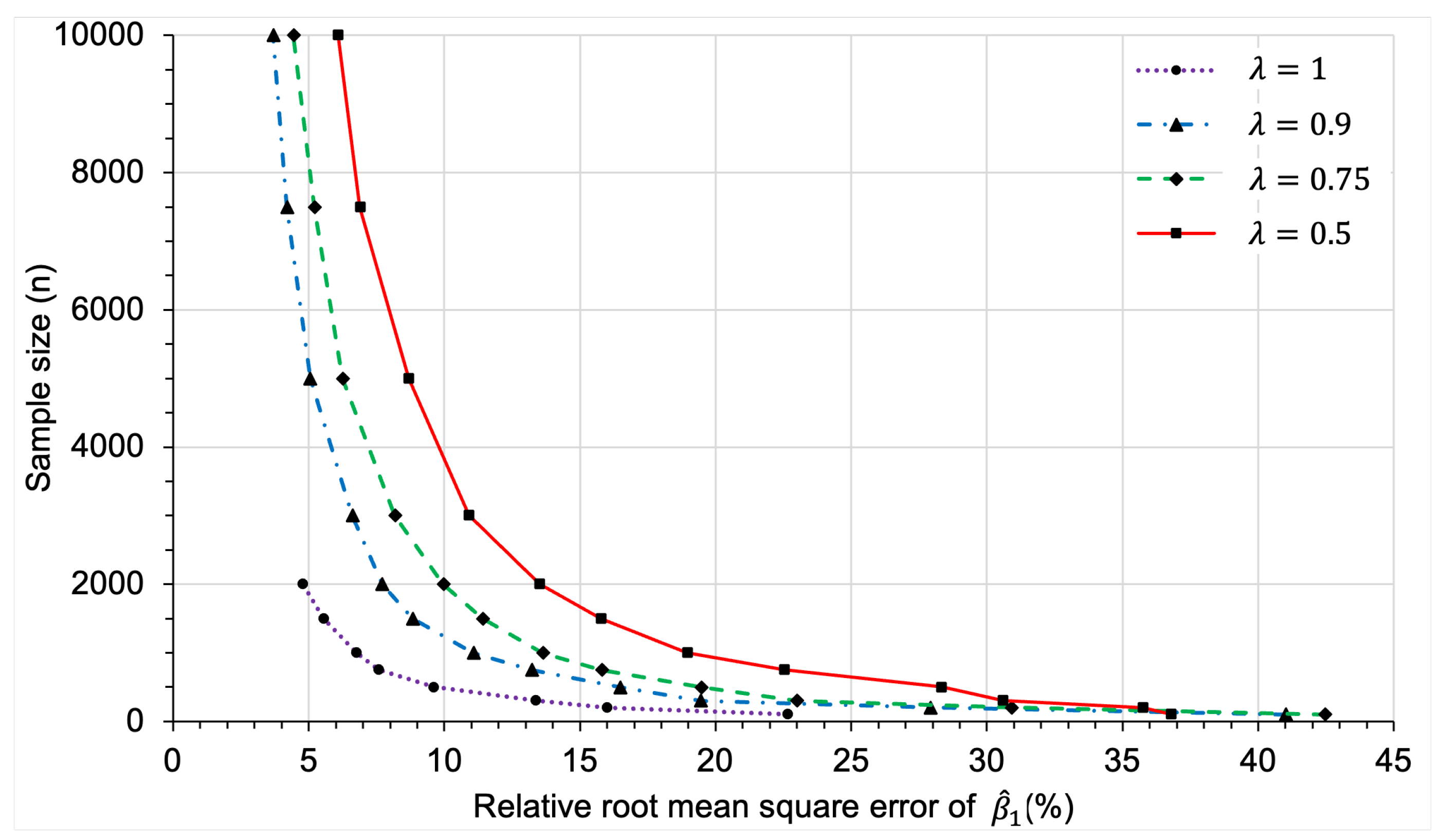

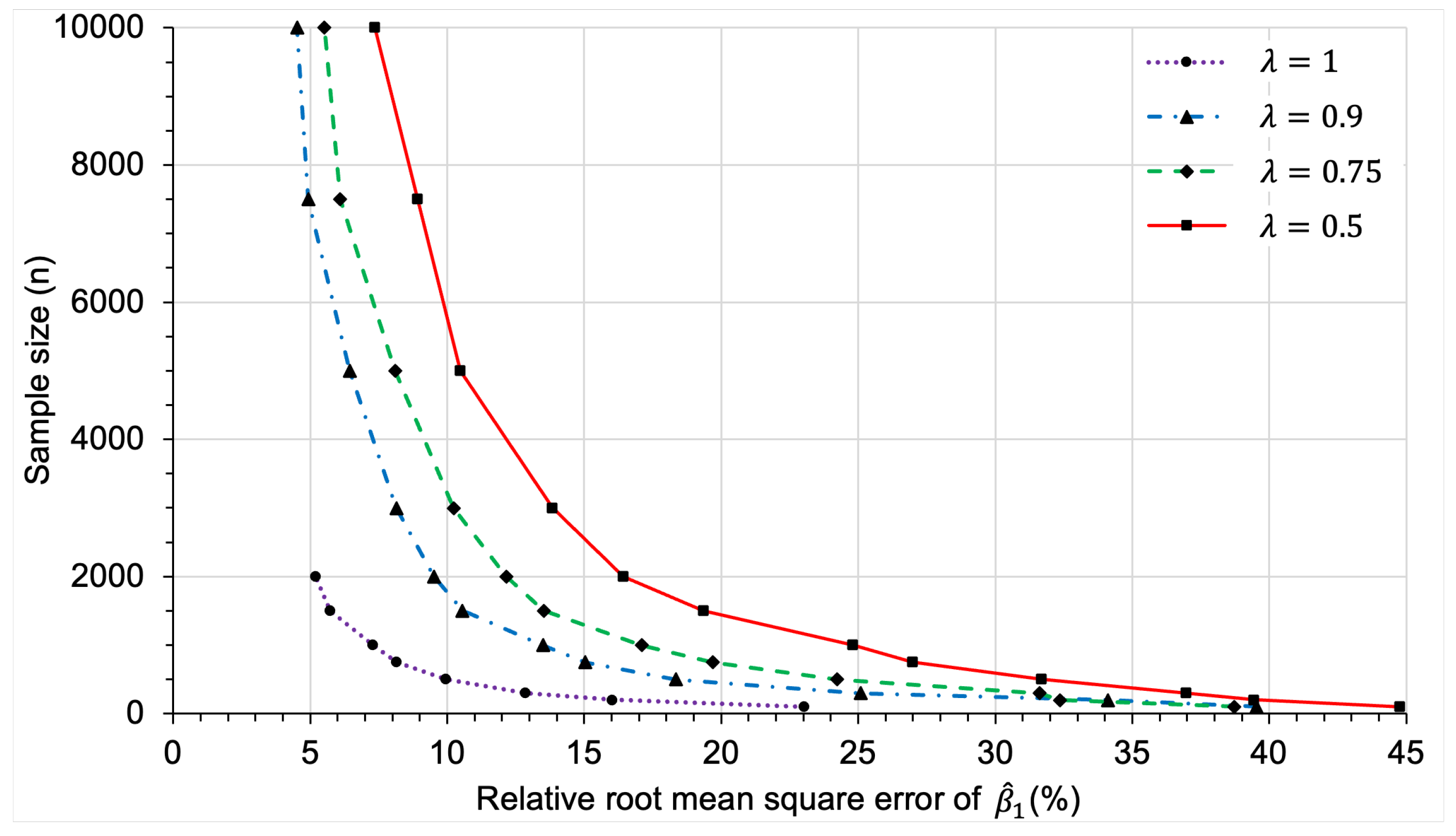

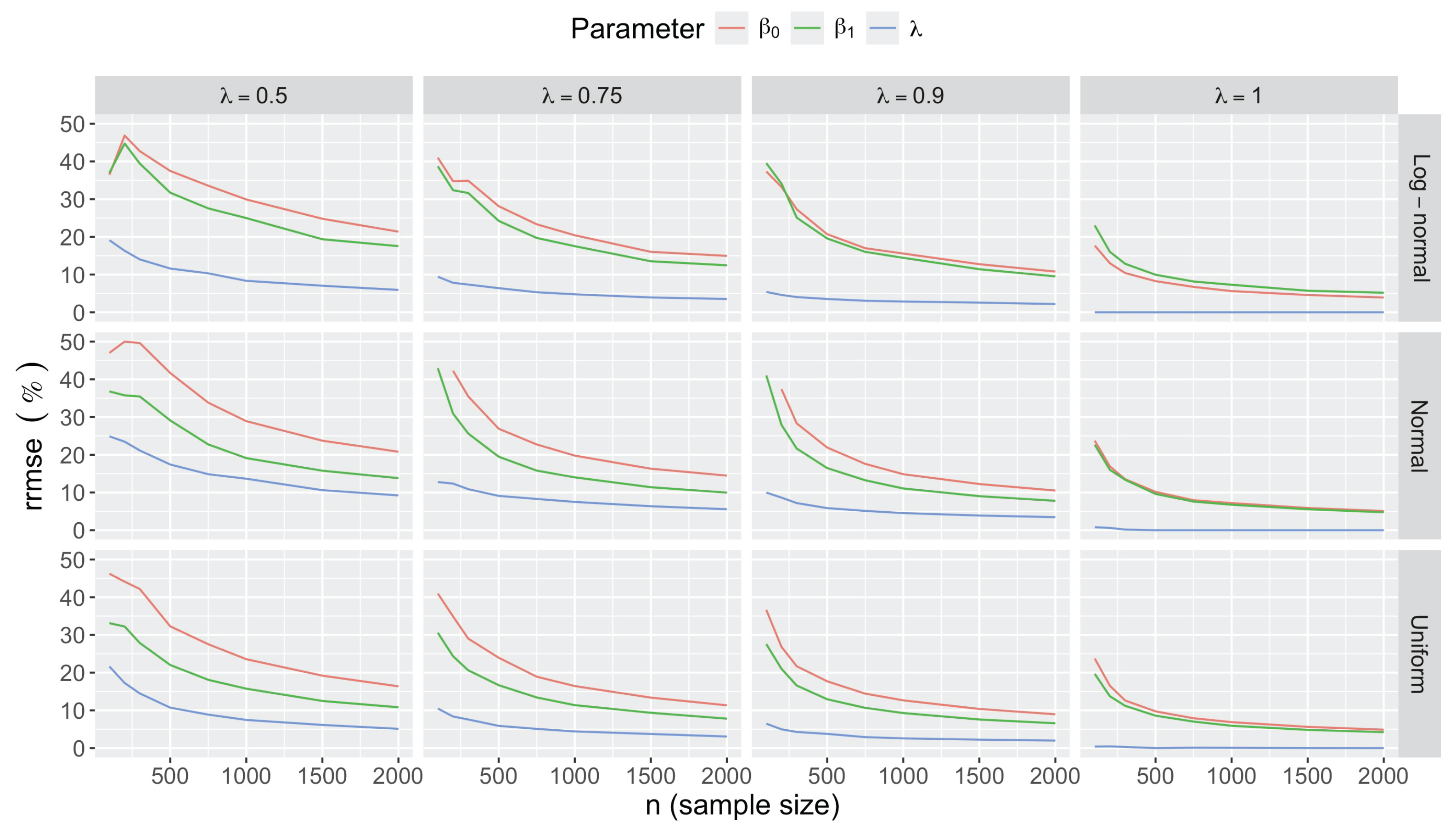

- Accuracy of . At , the relative of is close to zero for all and sample sizes. The accuracy also decreases with (Figure 3). Indeed, under the uniform with , the of is about 6% for , but reaches about 21% for . We observe a similar trend under the log-normal , with a around 5% at , and 19% at (). The estimate is comparatively less accurate under a normal , with a around 10% at , and 25% at ().

- Bias and accuracy of and . At (all ), the of regression parameter estimates and is also close to zero (Figure 2), and the (which is then essentially the standard deviation for each estimator) is about at , at , and at (Figure 3). As decreases, the relative increases, reaching for and for when and . This indicates that the lower , the larger the sample size required to achieve the same level of accuracy for regression coefficients.

- Effect of predictor distribution. The distribution of the predictor does not affect the accuracy of the estimates and for close to one (Figure 3). But as decreases, the relative is ceteris paribus minimum under uniform and maximum under log-normal for both and . At for instance, at under a uniform predictor. In contrast, at under a log-normal predictor.

- Impact of regression coefficients. The trends in the relative and shown for and (Figure 2 and Figure 3) are similar across combinations of and . Specifically, the of the estimates and increase with , and for , the is ceteris paribus minimum under uniform and maximum under log-normal (see Appendix C).

- Beta regression on the accuracy of . To summarize the general trends for the slope estimate , we fitted a beta regression to the values of the relative of as a function of the simulation factors. Table 4 presents the results of the fit which explain about 87% of the variability in . From Table 4, we observe that the leading factors in the variations of are , and , with significant interactions. For instance, decreasing by 0.1 results on average in a 6.5% increase in under a uniform and a small sample (). Switching then to a log-normal , we have on average a 16% increase in for small values, and about a 26% increase for values close to one. Under scenarios with , we observe an average 7% decrease in as compared with .

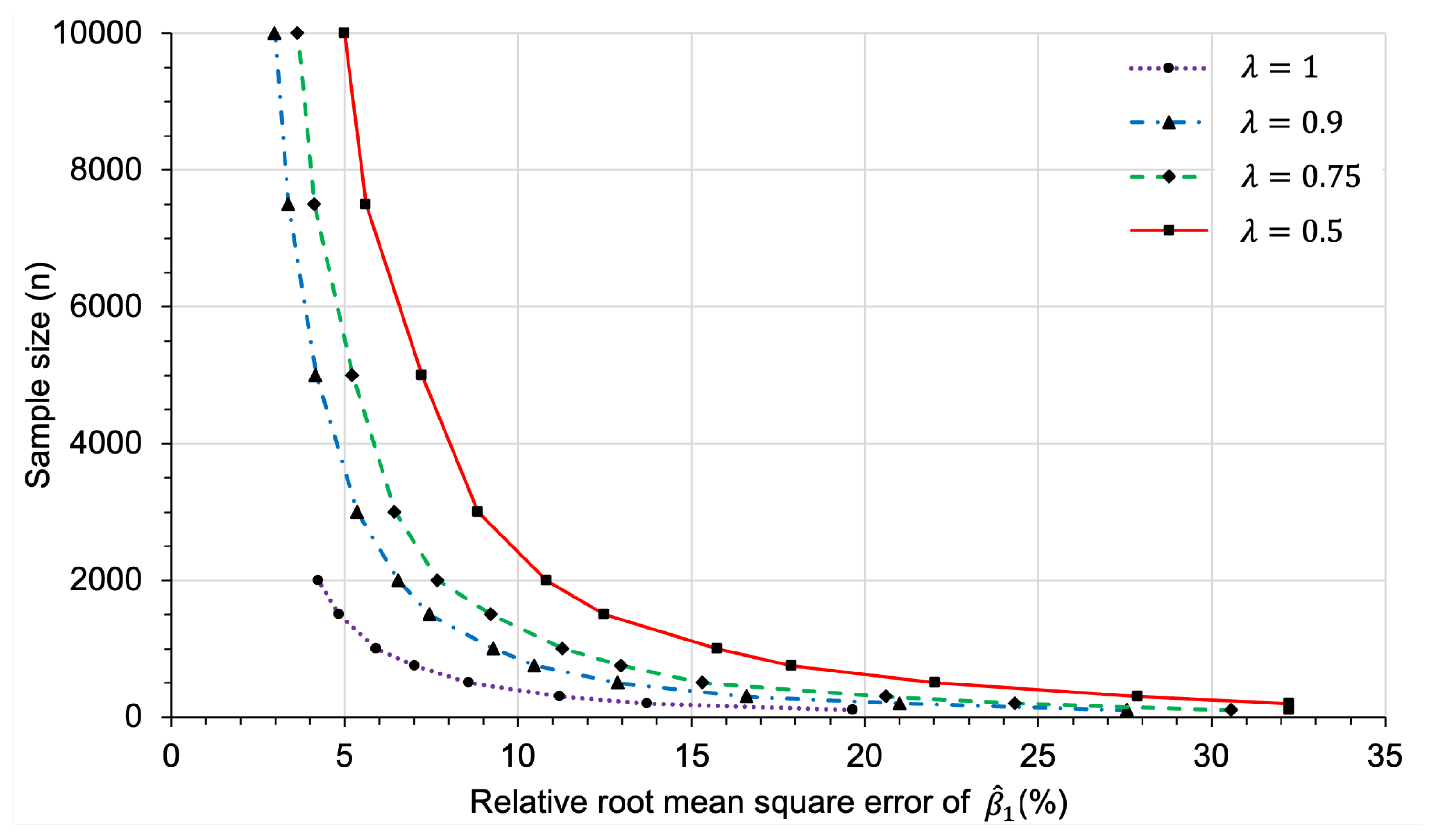

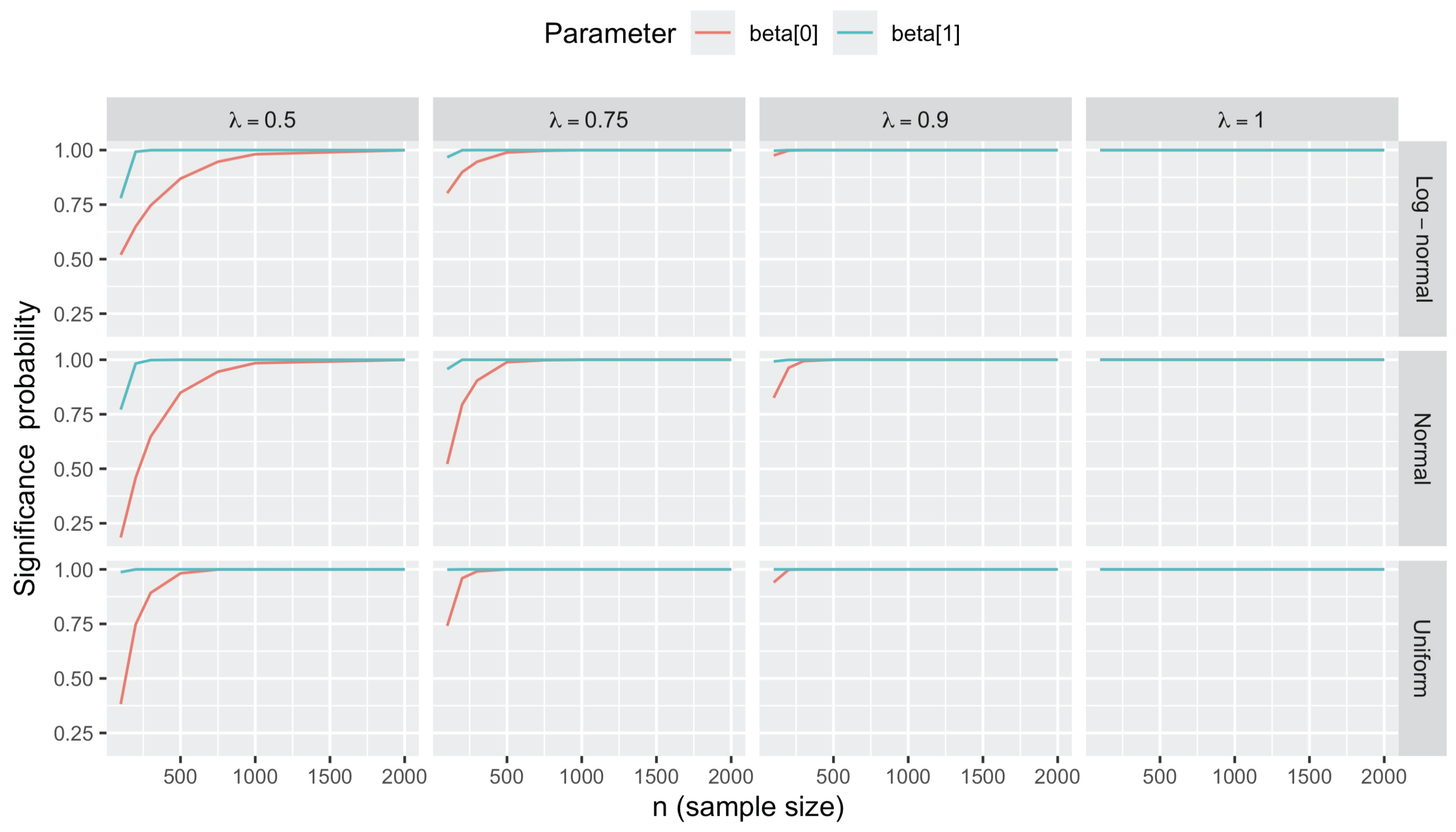

3.2.2. Sample Size Determination

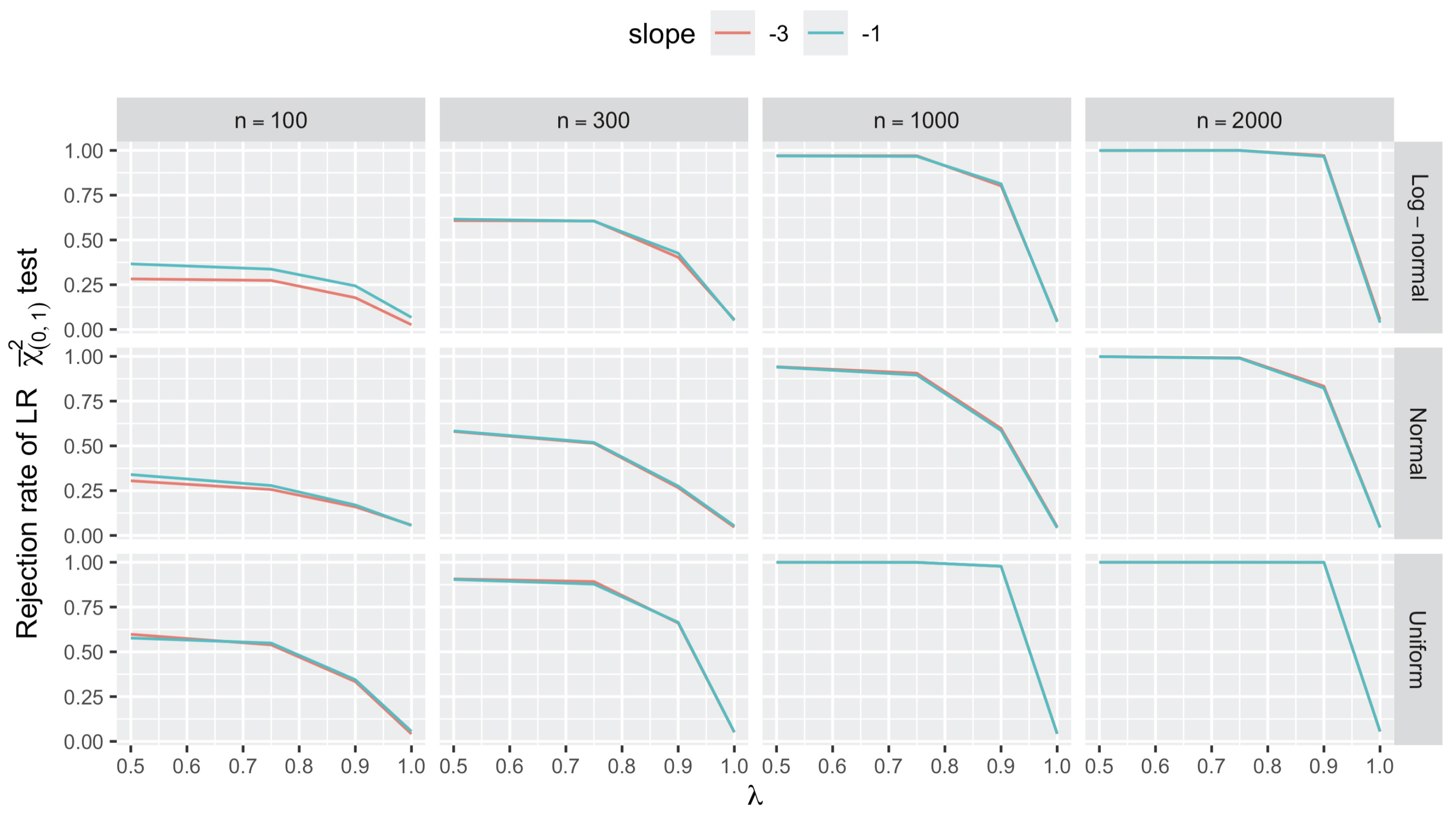

3.2.3. Testing for Unit Asymptote

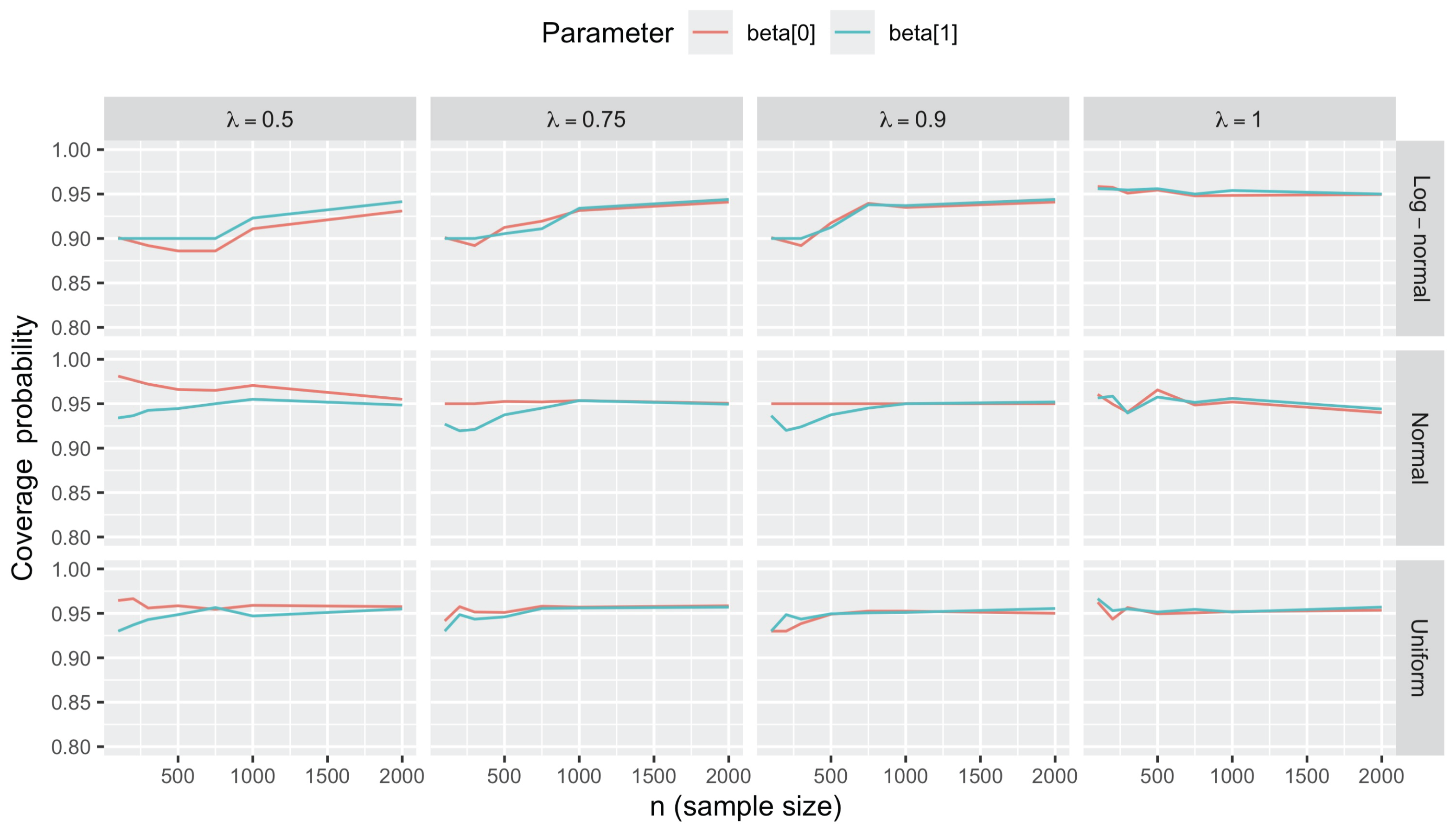

3.2.4. Statistical Inference on Regression Coefficients

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Proof of Propositions

Appendix A.1. Proof of Proposition 1

Appendix A.2. Proof of Proposition 2

-

Case of logit link:Here, , hence . Equation (A9) becomesDifferentiating both sides of the last equality with respect to yields . Along with the condition C1, this implies that , and by Lemma A1, we get .

-

Case of probit link:We have , and , hence . Note that by the condition C1 and the assumption , we have . Equation (A10) thus readsThen, because the assumption gives and condition C1 ensures , by Lemma A2, we have , which then gives by Lemma A1. We have overall shown that under the logit or probit link function, implies that for .

Appendix B. Score Vector and Information Matrix

Appendix B.1. Maximum Likelihood

Appendix B.2. Penalized Maximum Likelihood

Appendix C. Simulation Details

Appendix C.1. Simulation Design

| Simulation factor | Notation | Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 100, 200, 300, 500, 750, 1000, 1500, 2000 | |

| Upper limit of success probability | 0.5, 0.75, 0.9, 1 | |

| Intercept | 3, 8 | |

| Slope | -3, -2, -1 | |

| Distribution of the predictor | Uniform, Normal, Log-normal |

Appendix C.2. Additional Simulation Results

Appendix C.2.1. Bias

Appendix C.2.2. Accuracy

Appendix C.2.3. Sample Size Determination

References

- Harris, J.K. Primer on binary logistic regression. Family medicine and community health 2021, 9, e001290. [CrossRef]

- Zabor, E.C.; Reddy, C.A.; Tendulkar, R.D.; Patil, S. Logistic regression in clinical studies. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics 2022, 112, 271–277. [CrossRef]

- Halvorson, M.A.; McCabe, C.J.; Kim, D.S.; Cao, X.; King, K.M. Making sense of some odd ratios: A tutorial and improvements to present practices in reporting and visualizing quantities of interest for binary and count outcome models. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2022, 36, 284. [CrossRef]

- Nelder, J.A.; Wedderburn, R.W. Generalized linear models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (General) 1972, 135, 370–384.

- Webster, A.J. Multi-stage models for the failure of complex systems, cascading disasters, and the onset of disease. PloS one 2019, 14, e0216422. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, F.; Theis, F.J.; Rädler, J.O.; Hasenauer, J. Parameter estimation for dynamical systems with discrete events and logical operations. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 1049–1056. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Rohlfs, R.; Schwartz, R. Implementation of a discrete event simulator for biological self-assembly systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Winter Simulation Conference, 2005. IEEE, 2005, pp. 9–pp.

- Manhart, M.; Morozov, A.V. Protein folding and binding can emerge as evolutionary spandrels through structural coupling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 1797–1802. [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, P.; Nnoaham, K.E.; Clarke, D.; Capewell, S.; Rayner, M. Modelling the impact of a healthy diet on cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012, 66, 420–426. [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.; Holford, T. Additive, multiplicative, and other models for disease risks. American Journal of Epidemiology 1978, 108, 341–346. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fröhlich, H.; Grigoriev, D.; Vakulenko, S.; Zimmermann, J.; Weber, A.G. A simple 3-parameter model for cancer incidences. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 3388. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Powers, S.; Zhu, W.; Hannun, Y.A. Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development. Nature 2016, 529, 43–47.

- Peto, R. Epidemiology, multistage models, and short-term mutagenicity tests. International Journal of Epidemiology 2016, 45, 621–637. [CrossRef]

- Wacholder, S.; Han, S.S.; Weinberg, C.R. Inference from a multiplicative model of joint genetic effects for ovarian cancer risk. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2011, 103, 82–83. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, P.; Shibata, D. A simple algebraic cancer equation: calculating how cancers may arise with normal mutation rates. BMC cancer 2010, 10, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Siemiatycki, J.; Thomas, D.C. Biological models and statistical interactions: an example from multistage carcinogenesis. International journal of epidemiology 1981, 10, 383–387. [CrossRef]

- Armitage, P. Multistage models of carcinogenesis. Environmental health perspectives 1985, 63, 195–201.

- Loomba, R.; Yang, H.I.; Su, J.; Brenner, D.; Iloeje, U.; Chen, C.J. Obesity and alcohol synergize to increase the risk of incident hepatocellular carcinoma in men. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2010, 8, 891–898. [CrossRef]

- Ishak, K.J.; Kreif, N.; Benedict, A.; Muszbek, N. Overview of parametric survival analysis for health-economic applications. Pharmacoeconomics 2013, 31, 663–675. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Wu, J.L.; Hsu, C.C.; Wang, J.D.; Sung, J.M. Diabetes and end-stage renal disease synergistically contribute to increased incidence of cardiovascular events: a nationwide follow-up study during 1998–2009. Diabetes care 2014, 37, 277–285. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Aldana, R.; Gomez-Verjan, J.C.; Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; García-Peña, C. Spatial epidemiological study of the distribution, clustering, and risk factors associated with early COVID-19 mortality in Mexico. PloS one 2021, 16, e0254884. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Mavaddat, N.; Wilcox, A.N.; Cunningham, A.P.; Carver, T.; Hartley, S.; Babb de Villiers, C.; Izquierdo, A.; Simard, J.; Schmidt, M.K.; et al. BOADICEA: a comprehensive breast cancer risk prediction model incorporating genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Genetics in Medicine 2019, 21, 1708–1718. [CrossRef]

- Di Angelantonio, E.; Kaptoge, S.; Wormser, D.; Willeit, P.; Butterworth, A.S.; Bansal, N.; O’Keeffe, L.M.; Gao, P.; Wood, A.M.; Burgess, S.; et al. Association of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with mortality. Jama 2015, 314, 52–60.

- Ott, J.; Ullrich, A.; Mascarenhas, M.; Stevens, G. Global cancer incidence and mortality caused by behavior and infection. Journal of public health 2011, 33, 223–233. [CrossRef]

- Lee, P. Relation between exposure to asbestos and smoking jointly and the risk of lung cancer. Occupational and environmental medicine 2001, 58, 145–153. [CrossRef]

- Katz, K.A. The (relative) risks of using odds ratios. Archives of dermatology 2006, 142, 761–764. [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S. Noncollapsibility, confounding, and sparse-data bias. Part 1: The oddities of odds. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2021, 138, 178–181. [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S. Noncollapsibility, confounding, and sparse-data bias. Part 2: What should researchers make of persistent controversies about the odds ratio? Journal of clinical epidemiology 2021, 139, 264–268. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S. Estimating and contextualizing the attenuation of odds ratios due to non collapsibility. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 2017, 46, 786–804. [CrossRef]

- Janani, L.; Mansournia, M.A.; Nourijeylani, K.; Mahmoodi, M.; Mohammad, K. Statistical issues in estimation of adjusted risk ratio in prospective studies. Archives of Iranian medicine 2015, 18, 0–0.

- Correia, K.; Williams, P.L. Estimating the relative excess risk due to interaction in clustered-data settings. American Journal of Epidemiology 2018, 187, 2470–2480. [CrossRef]

- Marschner, I.C. Relative risk regression for binary outcomes: methods and recommendations. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Statistics 2015, 57, 437–462. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.K.; Mallawaarachchi, I.; Lee, S.; Tarwater, P. Methods for estimating relative risk in studies of common binary outcomes. Journal of applied statistics 2014, 41, 484–500. [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Nie, L.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Sun, W. Bivariate random effects models for meta-analysis of comparative studies with binary outcomes: methods for the absolute risk difference and relative risk. Statistical methods in medical research 2012, 21, 621–633. [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.B. Zero-inflated Poisson and binomial regression with random effects: a case study. Biometrics 2000, 56, 1030–1039. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.S.; Robins, J.M.; Wang, L. On modeling and estimation for the relative risk and risk difference. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2017, 112, 1121–1130. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Markes, S.; Richardson, T.S.; Wang, L. Multiplicative effect modelling: the general case. Biometrika 2022, 109, 559–566. [CrossRef]

- Doi, S.A.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Xu, C.; Lin, L.; Chivese, T.; Thalib, L. Controversy and debate: questionable utility of the relative risk in clinical research: paper 1: a call for change to practice. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2022, 142, 271–279. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Chen, Y.; Cole, S.R.; MacLehose, R.F.; Richardson, D.B.; Chu, H. Controversy and Debate: Questionable utility of the relative risk in clinical research: Paper 2: Is the Odds Ratio “portable” in meta-analysis? Time to consider bivariate generalized linear mixed model. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2022, 142, 280–287. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Chu, H.; Cole, S.R.; Chen, Y.; MacLehose, R.F.; Richardson, D.B.; Greenland, S. Controversy and Debate: Questionable utility of the relative risk in clinical research: Paper 4: Odds Ratios are far from “portable”—A call to use realistic models for effect variation in meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2022, 142, 294–304. [CrossRef]

- Suhail A, D.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Xu, C.; Lin, L.; Chivese, T.; Thalib, L. Questionable utility of the relative risk in clinical research: A call for change to practice. J Clin Epidemiol 2020.

- Mood, C. Logistic regression: Uncovering unobserved heterogeneity, 2017. 341160.

- Mood, C. Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European sociological review 2010, 26, 67–82. [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.S. Omitted variables and misspecified disturbances in the logit model. Technical report, Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, 2005.

- Yatchew, A.; Griliches, Z. Specification error in probit models. The Review of Economics and Statistics 1985, pp. 134–139. [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.F. Specification error in multinomial logit models: Analysis of the omitted variable bias. Journal of Econometrics 1982, 20, 197–209.

- Buis, M.L. Logistic regression: When can we do what we think we can do, 2017.

- Brzoska, P.; Sauzet, O.; Breckenkamp, J. Unobserved heterogeneity and the comparison of coefficients across nested logistic regression models: how to avoid comparing apples and oranges. International Journal of Public Health 2017, 62, 517–520. [CrossRef]

- Cologne, J.; Furukawa, K.; Grant, E.J.; Abbott, R.D. Effects of omitting non-confounding predictors from general relative-risk models for binary outcomes. Journal of Epidemiology 2019, 29, 116–122. [CrossRef]

- Schuster, N.A.; Twisk, J.W.; Ter Riet, G.; Heymans, M.W.; Rijnhart, J.J. Noncollapsibility and its role in quantifying confounding bias in logistic regression. BMC medical research methodology 2021, 21, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Berkson, J. Are there two regressions? Journal of the american statistical association 1950, 45, 164–180.

- King, G.; Zeng, L. Logistic regression in rare events data. Political analysis 2001, 9, 137–163. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.L. Alternatives to logistic regression models in experimental studies. The Journal of Experimental Education 2022, 90, 213–228. [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.; Mansournia, M.A. Penalization, bias reduction, and default priors in logistic and related categorical and survival regressions. Statistics in medicine 2015, 34, 3133–3143. [CrossRef]

- Firth, D. Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika 1993, 80, 27–38.

- Albert, A.; Anderson, J.A. On the existence of maximum likelihood estimates in logistic regression models. Biometrika 1984, 71, 1–10.

- Heinze, G.; Schemper, M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Statistics in medicine 2002, 21, 2409–2419. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Zeng, E. On the relationship between multicollinearity and separation in logistic regression. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation 2021, 50, 1989–1997. [CrossRef]

- Mansournia, M.A.; Geroldinger, A.; Greenland, S.; Heinze, G. Separation in logistic regression: causes, consequences, and control. American journal of epidemiology 2018, 187, 864–870. [CrossRef]

- Rainey, C. Dealing with separation in logistic regression models. Political Analysis 2016, 24, 339–355. [CrossRef]

- Botes, M.; Fletcher, L. Comparing logistic regression methods for a sparse data set when complete separation is present. In Proceedings of the Annual Proceedings of the South African Statistical Association Conference. South African Statistical Association (SASA), 2014, number con-1 in 2014, pp. 1–8.

- Hauck Jr, W.W.; Donner, A. Wald’s test as applied to hypotheses in logit analysis. Journal of the american statistical association 1977, 72, 851–853.

- Diop, A.; Diop, A.; Dupuy, J.F. Maximum likelihood estimation in the logistic regression model with a cure fraction. Electronic Journal of Statistics 2011, 5, 460–483.

- Diop, A.; Diop, A.; Dupuy, J.F. Simulation-based inference in a zero-inflated Bernoulli regression model. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation 2016, 45, 3597–3614.

- Diallo, A.O.; Diop, A.; Dupuy, J.F. Asymptotic properties of the maximum-likelihood estimator in zero-inflated binomial regression. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 2017, 46, 9930–9948. [CrossRef]

- Pho, K.H. Goodness of fit test for a zero-inflated Bernoulli regression model. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation 2024, 53, 756–771. [CrossRef]

- Diop, A.; Ba, D.B.; Lo, F. Asymptotic properties in the Probit-Zero-inflated Binomial regression model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.00483 2021.

- Garel, M.; Solberg, E.J.; Sæther, B.E.; Grøtan, V.; Tufto, J.; Heim, M. Age, size, and spatiotemporal variation in ovulation patterns of a seasonal breeder, the Norwegian moose (Alces alces). The American Naturalist 2009, 173, 89–104.

- Longford, N. Analysis of Covariance. In International Encyclopedia of Education (Third Edition), Third Edition ed.; Peterson, P.; Baker, E.; McGaw, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2010; pp. 18–24. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Thompson, R. Gauss-Hermite quadrature approximation for estimation in generalised linear mixed models. Computational statistics 2003, 18, 57–78. [CrossRef]

- Rabe-Hesketh, S.; Skrondal, A.; Pickles, A. Reliable estimation of generalized linear mixed models using adaptive quadrature. The Stata Journal 2002, 2, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Asheri, H.; Hosseini, R.; Araabi, B.N. A new EM algorithm for flexibly tied GMMs with large number of components. Pattern recognition 2021, 114, 107836. [CrossRef]

- Dempster, A.P.; Laird, N.M.; Rubin, D.B. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the royal statistical society: series B (methodological) 1977, 39, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Louis, T.A. Matching conditional and marginal shapes in binary random intercept models using a bridge distribution function. Biometrika 2003, 90, 765–775. [CrossRef]

- Azzalini, A.; Valle, A.D. The multivariate skew-normal distribution. Biometrika 1996, 83, 715–726. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P. Corrected Probability Mass Function of the Binomial Distribution. Resonance 2021, 26, 1721–1724.

- Shklyar, S. Identifiability of logistic regression with homoscedastic error: Berkson model. Modern Stochastics: Theory and Applications 2015, 2, 131–146. [CrossRef]

- Küchenhoff, H. The identification of logistic regression models with errors in the variables. Statistical Papers 1995, 36, 41–47. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaaibi, M.; Wesonga, R. Bias reduction in the logistic model parameters with the LogF (1, 1) penalty under MAR assumption. Frontiers in Applied Mathematics and Statistics 2022, 8, 1052752. [CrossRef]

- Heinze, G.; Puhr, R. Bias-reduced and separation-proof conditional logistic regression with small or sparse data sets. Statistics in medicine 2010, 29, 770–777. [CrossRef]

- Heinze, G.; Ploner, M. Fixing the nonconvergence bug in logistic regression with SPLUS and SAS. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2003, 71, 181–187. [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, H. The theory of probability; OuP Oxford, 1998.

- Fisher, R.A. On the mathematical foundations of theoretical statistics. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, containing papers of a mathematical or physical character 1922, 222, 309–368.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Susko, E. Likelihood ratio tests with boundary constraints using data-dependent degrees of freedom. Biometrika 2013, 100, 1019–1023. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A. Asymptotic distribution of test statistics in the analysis of moment structures under inequality constraints. Biometrika 1985, 72, 133–144.

- Molenberghs, G.; Verbeke, G. Likelihood ratio, score, and Wald tests in a constrained parameter space. The American Statistician 2007, 61, 22–27. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.D.; Allman, E.S.; Rhodes, J.A. Hypothesis testing near singularities and boundaries. Electronic journal of statistics 2019, 13, 2150. [CrossRef]

- Baey, C.; Cournède, P.H.; Kuhn, E. Asymptotic distribution of likelihood ratio test statistics for variance components in nonlinear mixed effects models. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 2019, 135, 107–122. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Bull, S.B. Penalized maximum likelihood inference under the mixture cure model in sparse data. Statistics in Medicine 2023, 42, 2134–2161. [CrossRef]

- Drton, M.; Williams, B. Quantifying the failure of bootstrap likelihood ratio tests. Biometrika 2011, 98, 919–934. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Windmeijer, F.A. An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models. Journal of econometrics 1997, 77, 329–342. [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.P.; White, I.R.; Crowther, M.J. Using simulation studies to evaluate statistical methods. Statistics in Medicine 2019, 38, 2074–2102. [CrossRef]

- Cribari-Neto, F.; Zeileis, A. Beta Regression in R. Journal of Statistical Software 2010, 34, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Gueorguieva, R. A multivariate generalized linear mixed model for joint modelling of clustered outcomes in the exponential family. Statistical modelling 2001, 1, 177–193.

- Bonat, W.H.; Jørgensen, B. Multivariate covariance generalized linear models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C: Applied Statistics 2016, 65, 649–675. [CrossRef]

- Kosmidis, I.; Firth, D. Bias reduction in exponential family nonlinear models. Biometrika 2009, 96, 793–804. [CrossRef]

- Kosmidis, I.; Firth, D. A generic algorithm for reducing bias in parametric estimation. Electronic Journal of Statistics 2010, 4, 1097–1112. [CrossRef]

- Blizzard, L.; Hosmer, W. Parameter estimation and goodness-of-fit in log binomial regression. Biometrical Journal 2006, 48, 5–22. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. Properties of sufficiency and statistical tests. Proceedings of the royal society of london. series a-mathematical and physical sciences 1937, 160, 268–282. [CrossRef]

- Rao, C. Score test: historical review and recent developments. Advances in ranking and selection, multiple comparisons, and reliability: methodology and applications 2005, pp. 3–20.

- Tovissodé, C.F.; Diop, A.; Glèlè Kakaï, R. Inference in skew generalized t-link models for clustered binary outcome via a parameter-expanded EM algorithm. Plos one 2021, 16, e0249604. [CrossRef]

- Vrabel, R. A note on the matrix determinant lemma. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 2016, 111, 643–646.

- Guyon, X. Statistique et Econométrie : du modèle linéaire aux modèles non-linéaires; Ellipses, 2001; p. 205. ISBN 2-7298-0842-6.

- Efron, B.; Hinkley, D.V. Assessing the accuracy of the maximum likelihood estimator: Observed versus expected Fisher information. Biometrika 1978, 65, 457–483.

- Cao, X.; Spall, J.C. Relative performance of expected and observed Fisher information in covariance estimation for maximum likelihood estimates. In Proceedings of the 2012 American Control Conference (ACC). IEEE, 2012, pp. 1871–1876.

- Yuan, X.; Spall, J.C. Confidence intervals with expected and observed fisher information in the scalar case. In Proceedings of the 2020 American Control Conference (ACC). IEEE, 2020, pp. 2599–2604.

- Jiang, S.; Spall, J.C. Comparison between Expected and Observed Fisher Information in Interval Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 55th Annual Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–6.

- Magnus, J.R.; Neudecker, H. Matrix differential calculus with applications to simple, Hadamard, and Kronecker products. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 1985, 29, 474–492. [CrossRef]

- Magnus, J.R.; Neudecker, H. The commutation matrix: some properties and applications. The annals of statistics 1979, 7, 381–394. [CrossRef]

- Hamid, H.A.; Wah, Y.B.; Xie, X.J.; Rahman, H.A.A. Assessing the effects of different types of covariates for binary logistic regression. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings. American Institute of Physics, 2015, Vol. 1643, pp. 425–430.

| Parameter | SLR | MLR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | ||||

| 0.9300 (0.2031) | [ 0.5319, 1.3281] | 2.9461 (0.8613) | [ 1.2581, 4.6342] | ||

| () | -1.1359 (0.1302) | [-1.3911, -0.8806] | -1.9427 (0.3915) | [-2.7100, -1.1755] | |

| - | - | 1.1586 (0.3262) | [ 0.5192, 1.7979] | ||

| - | - | 0.7611 (0.0593) | [ 0.6269, 0.8579] | ||

| Deviance | 277.4280 | 270.3012 | |||

| AIC | 281.4280 | 276.3012 | |||

| 0.3054 | 0.3232 | ||||

| Parameter | ZIL | MLR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | ||||

| 1.2107 (0.3296) | [ 0.5648, 1.8566] | 2.9969 (1.1077) | [ 0.8259, 5.1679] | ||

| () | -1.1456 (0.1758) | [-1.4901, -0.8010] | -1.9110 (0.5003) | [-2.8916, -0.9304] | |

| 4.2708 (1.4974) | [ 1.3360, 7.2055] | 4.5245 (1.5648) | [ 1.4575, 7.5914] | ||

| () | -1.1949 (0.3353) | [-1.8520, -0.5378] | -1.2602 (0.3542) | [-1.9545, -0.5659] | |

| - | - | 1.5059 (0.4904) | [ 0.5447, 2.4671] | ||

| - | - | 0.8185 (0.0729) | [ 0.6329, 0.9218] | ||

| Deviance | 229.5335 | 222.5019 | |||

| AIC | 237.5335 | 232.5019 | |||

| 0.3678 | 0.3872 | ||||

| Measure | Model | Model parameter (true value) | Predictive power | ||||||

| (3) | (-2) | (3) | (-1) | (0.8) | |||||

| Mean | ZIL | 2.1830 | -1.6863 | 2.2972 | -0.8708 | - | 0.0333 | 0.9690 | |

| MLR | 3.3368 | -2.1564 | 3.2767 | -1.0685 | 0.8022 | 0.0280 | 0.9806 | ||

| (%) | ZIL | -27.23 | 15.69 | -23.43 | 12.92 | - | - | - | |

| MLR | 11.23 | -7.82 | 9.22 | -6.85 | 0.28 | - | - | ||

| (%) | ZIL | 50.42 | 34.49 | 45.00 | 30.40 | - | - | - | |

| MLR | 43.18 | 32.54 | 40.01 | 29.35 | 9.55 | - | - | ||

| Term | Mean (log link) | Precision parameter (log link) | |||

| Estimate (SE) | Estimate (SE) | ||||

| Intercept | -0.8591 (0.0174) | [-0.8931, -0.8251] | 6.1178 (0.2054) | [ 5.7152, 6.5204] | |

| n | -0.0003 (0.0000) | [-0.0003, -0.0003] | 0.0020 (0.0002) | [ 0.0016, 0.0024] | |

| -0.6482 (0.0278) | [-0.7027, -0.5937] | -2.3751 (0.2475) | [-2.8602, -1.8899] | ||

| -0.0688 (0.0104) | [-0.0892, -0.0484] | 0.2182 (0.0741) | [ 0.0730, 0.3633] | ||

| -0.0026 (0.0027) | [-0.0078, 0.0026] | - | - | ||

| = Normal | 0.0942 (0.0190) | [ 0.0570, 0.1314] | -0.7010 (0.1460) | [-0.9872, -0.4149] | |

| = Log-normal | 0.1588 (0.0190) | [ 0.1216, 0.1960] | -0.6797 (0.1460) | [-0.9658, -0.3935] | |

| -0.0006 (0.0000) | [-0.0006, -0.0005] | -0.0012 (0.0002) | [-0.0016, -0.0007] | ||

| 0.0001 (0.0000) | [ 0.0001, 0.0001] | - | - | ||

| Normal) | 0.0001 (0.0001) | [ 0.0001, 0.0001] | 0.0006 (0.0001) | [ 0.0003, 0.0009] | |

| Log-normal) | 0.0001 (0.0001) | [ 0.0001, 0.0002] | 0.0003 (0.0001) | [ 0.0001, 0.0006] | |

| Normal) | 0.0499 (0.0293) | [-0.0075, 0.1072] | - | - | |

| Log-normal) | 0.1010 (0.0295) | [ 0.0432, 0.1588] | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).