Submitted:

25 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Clinical prediction requires formalizing uncertainty into a statistical model. However, persistent confusion between prediction and inference, and between traditional (stepwise) and modern (penalized) development strategies, leads to unstable, poorly calibrated, and overfit models. A structured statistical framework is essential. Methods: This article is a structured, didactic tutorial that explains the core concepts of clinical prediction. It covers the definition of a prediction model, the fundamental strategies for its construction, and the essential framework for its evaluation. Results: The tutorial demystifies model construction by contrasting robust modern methods (penalized regression, LASSO) against traditional approaches (univariable filtering, stepwise selection). It explains how to manage key pitfalls such as collinearity (VIF), non-linearity (RCS), and interaction terms. Finally, it provides a comprehensive assessment framework by reframing model performance into its three essential domains: discrimination (ranking ability), calibration (probabilistic honesty), and validation (generalizability). Conclusions: This guide provides clinicians with the essential methodological foundation to critically appraise and understand modern prediction models.

Keywords:

- Formalizing the 'Clinical Gestalt': A Conceptual Introduction to Prediction

- The Model's Purpose: Prediction vs. Inference

- Job #1: The "Why" Job (Finding the Most Valuable Player)

- Key Question: "Is this one specific factor truly and independently linked to the outcome?"

- Goal: To test a single factor’s isolated importance (e.g., “Is a high WBC count strongly linked to perforated appendix on its own?”).

- Method: Build a model that adjusts for other variables (like age or symptom duration) to isolate that association.

- Limitation: It identifies importance but not predictive usefulness; a factor may be biologically relevant yet contribute little to individual risk estimation.

- Job #2: The "What" Job (Predicting the Game)

- A different task: instead of explaining why, we estimate "What is this patient's probability?"

- Key Question: “What is this specific patient’s personal risk of the outcome?”

- Goal: Generate the most accurate forecast, not a causal explanation.

- Method: Use all variables that improve prediction — including those not independently associated — just as a “home advantage” predicts the score without reflecting player skill.

- Why This Distinction Is Everything

- The Engine of Prediction: A Look Inside

- The "Yes/No" Problem

- Diagnosis: Does this patient with right lower quadrant pain actually have appendicitis? (Yes/No)

- Morbidity: Will this patient develop a surgical site infection? (Yes/No)

- Mortality: Will this specific patient die within 30 days of surgery? (Yes/No)

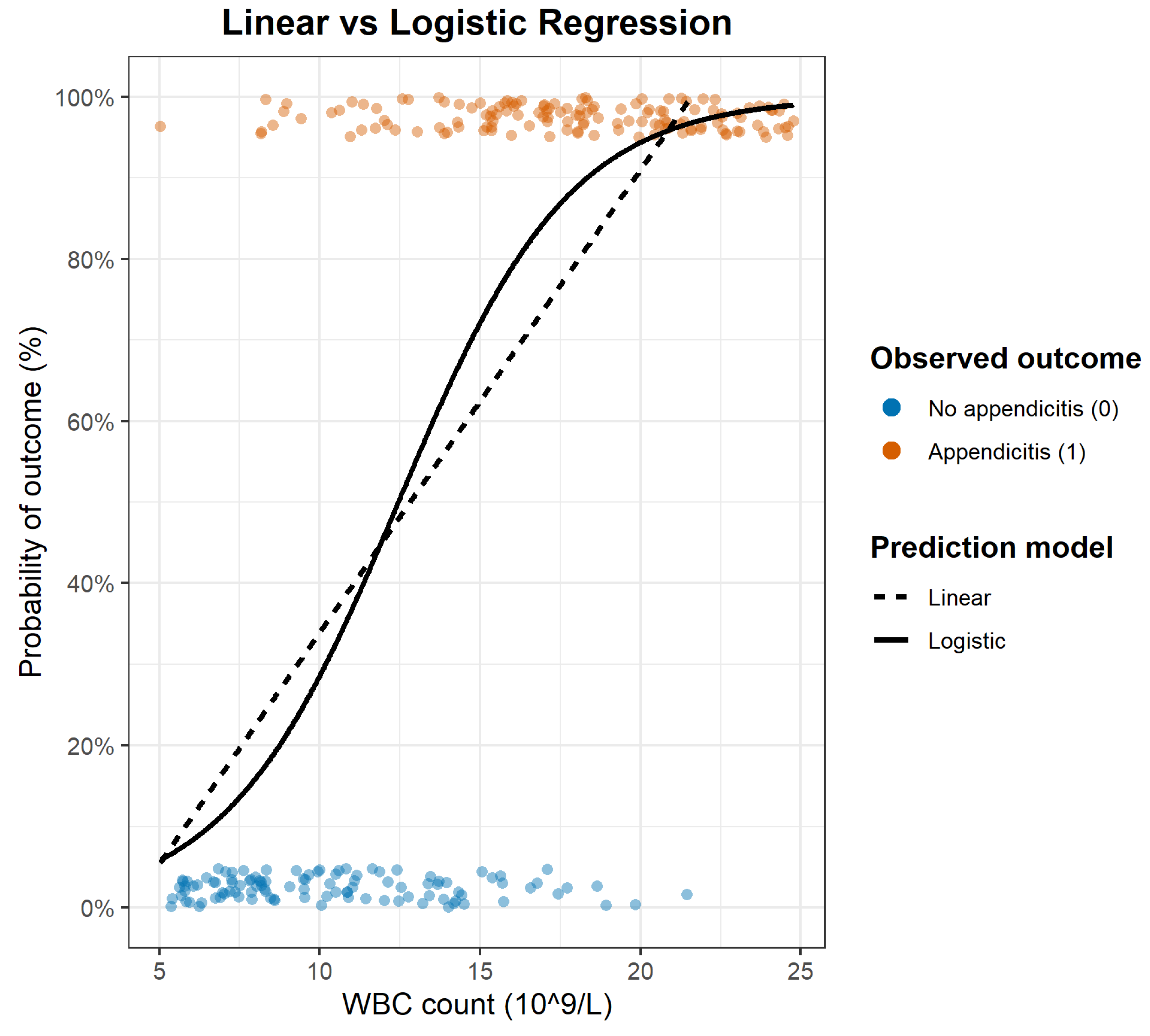

- The Foundational Tool: Linear Regression

- Logistic Regression: The Standard Model for Binary Outcomes

- Center (Location): where predicted probability crosses ~50% — the tipping point along the predictor scale.

- Steepness (Slope): how sharply risk changes near that point — a steep slope signals a strong predictor, a flat one a weak effect.

- The Multivariable Challenge: From a Simple Tool to a Real-World Model

- The Limits of a Single Predictor

- The Multivariable Logistic Regression Engine

- Step 1 – Linear Predictor (Score): All predictors are combined into a single number by multiplying each by its coefficient and summing the results — a mathematical translation of the clinical gestalt. This produces an “unbounded” score, just like in linear regression.

- Step 2 – Logistic Transformation (Probability): That score is then passed through the logistic (S-shaped) function, which converts it into a valid probability between 0% and 100%.

- Modeling Complexity: Non-linearity and Interactions

- Restricted Cubic Splines (RCS)

- Critical Pitfalls in Predictive Modelling

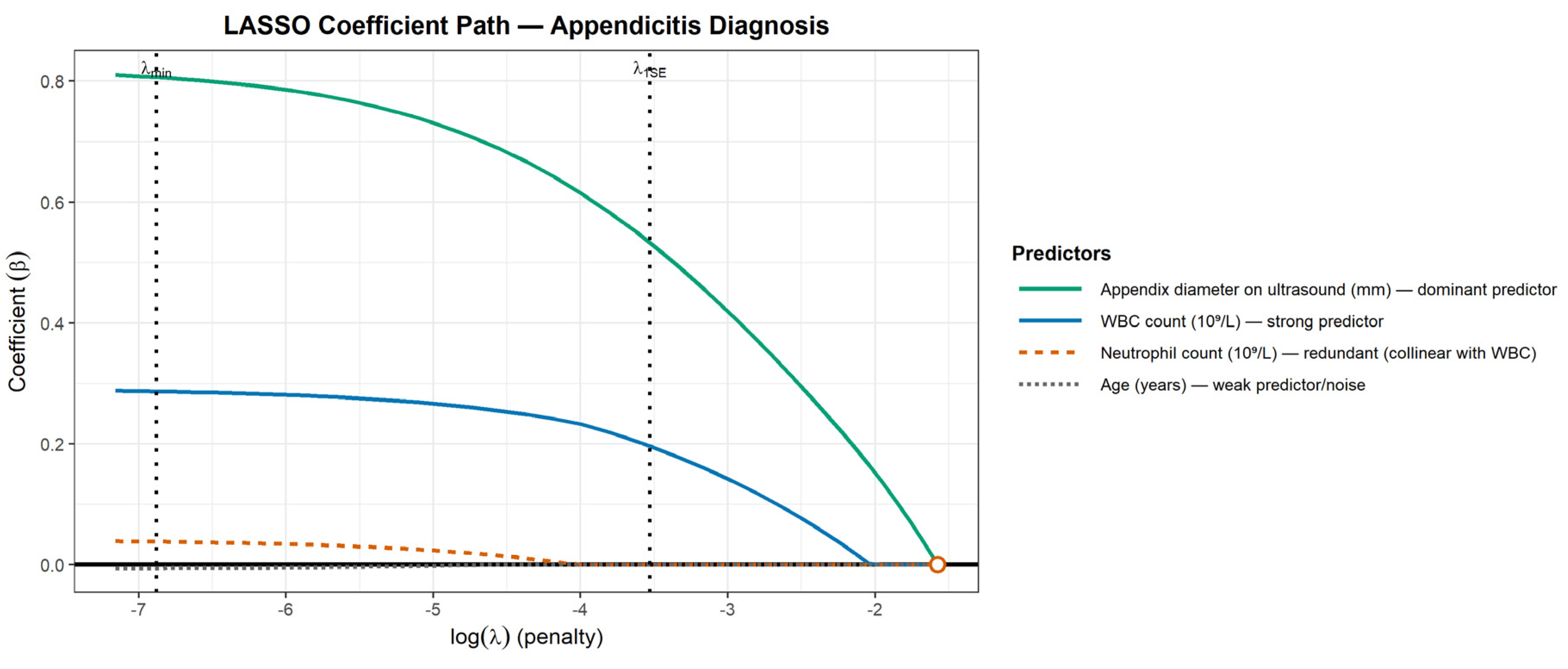

- The Problem of Collinearity (Redundant Predictors): Collinearity occurs when predictors provide overlapping information — effectively “echoing” each other [7]. For example, WBC count and Absolute Neutrophil Count describe the same biological process and tend to move together. This makes the model unstable because it cannot determine how to apportion the weight between them. The result can be extreme or contradictory coefficient estimates. Collinearity is diagnosed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF): a VIF of 1 indicates independence, while higher values (often >5 or >10) signal inflated variance and coefficient instability [7].

- The Problem of "Noise" vs. "Signal" (Overfitting): Clinical reasoning is naturally parsimonious: it prioritizes a few strong predictors and ignores irrelevant noise [6]. Overfitting occurs when a model does the opposite — including too many weak or irrelevant variables for the available sample size. The Events Per Variable (EPV) ratio is a key indicator of this risk. The traditional rule of thumb is 10 EPV [8], but modern studies show this threshold is not universal: the required EPV depends on predictor strength and modeling strategy. Penalized methods like LASSO can safely operate with lower EPV because they constrain complexity, whereas even 10 EPV may be inadequate when predictors are weak. When EPV is too low, the model starts “memorizing” random quirks in the data rather than learning real patterns — classic overfitting. This leads to unstable coefficients and poor performance on new patients, a finding confirmed repeatedly by simulation studies [9]. The dataset used in Figure 2 illustrates the opposite case: high EPV ensures stability.

- The Challenge of Missing Data: Missingness is widespread in clinical datasets and can introduce bias if poorly handled [10]. Common but flawed approaches include complete-case analysis (dropping patients with any missing value, reducing power and distorting representativeness) and mean imputation (which falsely shrinks variability). The recommended approach for data that are Missing At Random is Multiple Imputation (MI) [11], which creates several plausible datasets and pools their estimates, yielding unbiased coefficients and correctly estimated uncertainty.

- Building the Model: The Challenge of Variable Selection

- The Classical "Manual" Method: Univariable Filtering

- Step 1 (Filter): Run separate univariable regressions for each candidate predictor (e.g., 100 variables, as an illustrative example).

- Step 2 (Build): From the results, keep only predictors with a “promising” p-value (e.g., p < 0.10–0.20), rank them by Odds Ratio or coefficient size, and select a fixed number of “top” variables (e.g., 5–10) for the final multivariable model.

- The "Automated" Method: Stepwise Regression

- Forward stepwise: start with no variables and keep adding the “most significant” ones until none meet the entry threshold.

- Backward stepwise: start with all candidate predictors and remove the least significant until all remaining satisfy the retention threshold.

- The Modern Solution: LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) Regression

- small λ → minimal shrinkage → more variables retained

- large λ → stronger shrinkage → weak predictors forced toward zero

- Prevents overfitting by penalizing unnecessary complexity.

- Handles collinearity naturally — between two redundant predictors, one is retained and the other is suppressed.

- Improves reproducibility because the selection is based on penalized optimization rather than fragile p-value thresholds.

- Model Assessment: Validation and Calibration

- Model Linkage: The ROC curve is created by plotting sensitivity against specificity across every possible probability threshold generated by the logistic model. The model is the engine; the ROC simply visualizes how well it separates those with and without the outcome.

- Discrimination Assessment: The ROC curve and its summary statistic — the Area Under the Curve (AUC) — quantify discrimination: the model’s ability to correctly rank patients by risk. It answers “Who is higher risk?” but not “How accurate is the predicted probability?”

-

Methodological Limitations: AUC reflects ranking performance only. A model can have a high AUC yet still be clinically poor if it is miscalibrated or fails to generalize. The ROC-AUC also has well-known limitations:

- insensitivity to calibration

- insensitivity to disease prevalence

- equal weighting of false positives/false negatives

- weak guidance for real clinical decision-making

- Is it generalizable? → this is tested through validation

- Is it honest and accurate? → this is tested through calibration

- Validation: Testing Generalizability

-

Internal Validation (minimum standard): When no external dataset is available, a pseudo-new dataset must be created from the original sample. Two accepted approaches are:

- ⚬

- k-fold cross-validation: the data are partitioned into k folds; the model is repeatedly trained on k–1 folds and tested on the remaining fold, producing an average performance estimate across all folds [16].

- ⚬

- Bootstrap validation: a more statistically powerful method [17], in which hundreds or thousands of resamples are drawn with replacement to estimate and correct the optimism in performance, yielding an “honest” score.

- External Validation (gold standard): The model is then tested on an entirely independent dataset (“Data B”), ideally from a different setting or population. Sustained performance in this new cohort confirms generalizability [18].

- Calibration: Testing "Honesty" and Accuracy

-

Visual Assessment

- ⚬

- Calibration Plot: predicted risk on the X-axis vs observed risk on the Y-axis; a perfectly calibrated model lies along the 45° line. A LOESS smoother is often added to show the trend [20].

-

Quantitative Assessment

- ⚬

- Calibration slope: ideal = 1.0; <1.0 indicates overfitting (predictions too extreme).

- ⚬

- Calibration intercept: ideal = 0.0; deviations indicate systematic over- or underestimation.

- ⚬

- Brier Score: measures average squared prediction error; lower is better, though it mixes discrimination and calibration and is prevalence-dependent [21].

- ⚬

- ICI (Integrated Calibration Index): a modern summary measure of calibration error that isolates numerical miscalibration without conflating it with discrimination.

- Clinical Utility: The Test of Usefulness (Decision Curve Analysis)

- Statistical Integrity (Accuracy + Honesty): high discrimination and reliable calibration form the foundation.

- Parsimony: use only the predictors necessary for optimal performance; simpler models are more stable and less prone to overfitting.

- Interpretability: clinicians must be able to understand why a prediction is generated; penalized regression (e.g., LASSO) preserves transparency by limiting unnecessary variables.

- Generalizability: the model must work in new patients and real settings, confirmed through external validation.

- Applicability: feasible in routine care — not dependent on rare, expensive, or operationally unrealistic inputs.

- Implementation / Accessibility: delivered in a usable form (score, nomogram, calculator, or EHR integration) to enable consistent, low-friction deployment.

- Fairness / Equity: performance must be consistent across clinically relevant subgroups. A seminal example is the use of healthcare costs as a proxy for health needs. A model trained on this data incorrectly learns that minority populations, who often have less access to care and thus lower costs for the same level of illness, are "healthier." This leads to the inequitable allocation of healthcare resources and demonstrates how structural biases can be inherited by the model. Even without explicit use of protected attributes, models may inherit bias from proxy variables that encode structural inequities — such as healthcare cost being incorrectly treated as a marker of health need, disproportionately disadvantaging underrepresented groups [23].

- External Context: Reporting Standards and Limitations

- Reporting Guidelines (The Methodological Checklist)

- Inherent Limitations of Predictive Modeling

- Context dependency: performance depends on the setting and population; generalizability is never universal, especially when transporting models across different health systems, geographic regions, or socioeconomic contexts.

- Interpretability trade-off: more complex architectures (e.g., neural networks) may improve accuracy at the expense of transparency.

- Obsolescence: models drift over time as practice, diagnostics, or epidemiology change.

- Conclusion

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Financial Statement/Funding

Ethical approval

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steyerberg EW. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating. 2nd ed. Cham: Springer; 2019.

- Galit Shmueli. "To Explain or to Predict?." Statist. Sci. 25 (3) 289 - 310, August 2010. [CrossRef]

- Harrell FE Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. 2nd ed. Cham: Springer; 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hosmer DW Jr., Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [CrossRef]

- Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989 May;8(5):551-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Springer; 2009.

- Mansfield, E. R., & Helms, B. P. (1982). Detecting Multicollinearity. The American Statistician, 36(3a), 158–160. [CrossRef]

- Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996 Dec;49(12):1373-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Habbema JD. Stepwise selection in small data sets: a simulation study of bias in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999 Oct;52(10):935-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2002. 408 p.

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. Print ISBN: 9780471087052. [CrossRef]

- Draper NR, Smith H. Applied Regression Analysis. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1998.

- 13. Robert Tibshirani, Regression Shrinkage and Selection Via the Lasso, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), Volume 58, Issue 1, January 1996, Pages 267–288, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02080.x. [CrossRef]

- Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982 Apr;143(1):29-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arredondo Montero J, Martín-Calvo N. Diagnostic performance studies: interpretation of ROC analysis and cut-offs. Cir Esp (Engl Ed). 2023 Dec;101(12):865-867. Epub 2022 Nov 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Stone, Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), Volume 36, Issue 2, January 1974, Pages 111–133, https://. [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE Jr, Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Aug;54(8):774-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siontis GC, Tzoulaki I, Castaldi PJ, Ioannidis JP. External validation of new risk prediction models is infrequent and reveals worse prognostic discrimination. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015 Jan;68(1):25-34. Epub 2014 Oct 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Calster B, Nieboer D, Vergouwe Y, De Cock B, Pencina MJ, Steyerberg EW. A calibration hierarchy for risk models was defined: from utopia to empirical data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Jun;74:167-76. Epub 2016 Jan 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin PC, Steyerberg EW. Graphical assessment of internal and external calibration of logistic regression models by using loess smoothers. Stat Med. 2014 Feb 10;33(3):517-35. Epub 2013 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brier GW. Verification of forecasts expressed in terms of probability. Mon Weather Rev. 1950;78(1):1-3.

- Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006 Nov-Dec;26(6):565-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019 Oct 25;366(6464):447-453. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ. 2015 Jan 7;350:g7594. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins GS, Moons KGM, Dhiman P, Riley RD, Beam AL, Van Calster B, Ghassemi M, Liu X, Reitsma JB, van Smeden M, Boulesteix AL, Camaradou JC, Celi LA, Denaxas S, Denniston AK, Glocker B, Golub RM, Harvey H, Heinze G, Hoffman MM, Kengne AP, Lam E, Lee N, Loder EW, Maier-Hein L, Mateen BA, McCradden MD, Oakden-Rayner L, Ordish J, Parnell R, Rose S, Singh K, Wynants L, Logullo P. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ. 2024 Apr 16;385:e078378. Erratum in: BMJ. 2024 Apr 18;385:q902. doi: 10.1136/bmj.q902. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Feature | Univariable Filtering | Stepwise Regression | LASSO (Penalized Regression) |

| Selection Criterion | Univariable p-value (isolated) | p-value (automated) | Cross-Validation (optimizes performance) |

| Overfitting Risk | High | Very High (structurally designed to overfit) | Low (structurally designed to prevent overfitting) |

| Handling Collinearity | None (fails) | Unstable (arbitrarily picks one) | Robust (shrinks one predictor to zero) |

| Model Stability | Low | Very Low (not reproducible) | High (reproducible) |

| Methodological Status | Discouraged | Strongly Discouraged | Modern Standard |

| Quality Domain | Metric | Typical Range | Function |

| Discrimination | AUC / ROC | 0.5 (chance) to 1.0 (perfect) | Ranks individuals by relative risk. |

| Calibration (Honesty) | Calibration plot / Brier score / ICI | Brier = 0.0 (perfect) | Assesses the accuracy of predicted probabilities. |

| Robustness | Internal validation (Bootstrap) | Optimism-corrected performance | Tests the reproducibility on unseen data. |

| Clinical Utility | Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) | Net Benefit | Evaluates whether using the model improves decision-making. |

| Validation Level | Type | What It Demonstrates | Methodological Value |

| Level 0 | Apparent performance (resubstitution) | Model tested on its own training data; no optimism correction. | Not valid as performance evidence. |

| Level 1 | Internal validation (CV / Bootstrap) | Corrects for optimism; evaluates reproducibility in the same population. | Minimum acceptable standard. |

| Level 2 | External validation (independent dataset) | Demonstrates reproducibility across institutions or settings. | Gold standard for generalizability. |

| Level 3 | Transportability (context shift) | Confirms robustness across changes in prevalence, case-mix, or system. | Highest credibility threshold. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).