1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to represent the leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide, accounting for approximately 17.9 million deaths annually and placing immense strain on health systems [

1]. Structured physical activity and supervised exercise programs are consistently recognised as cornerstones for both prevention and secondary rehabilitation [

2]. Regular exercise has been shown to improve aerobic capacity, reduce major risk factors such as hypertension, and decrease rehospitalisation rates. Nevertheless, implementation in real-world settings faces considerable challenges, including variability in individual response to training, restricted availability of personalised interventions, and difficulties in sustaining long-term adherence.

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has rapidly become a disruptive force in medicine [

3,

4,

5,

25]. Although initially applied in diagnostic imaging, risk stratification, and predictive analytics [

4,

5,

15], AI is increasingly entering the therapeutic domain. Its capacity to analyse large, complex datasets and to generate adaptive, data-driven recommendations makes it especially suited for exercise interventions, which require personalisation, continuous feedback, and scalability.

Several domains highlight how artificial intelligence may transform the design and delivery of exercise-based cardiovascular interventions. One of the most evident contributions is the personalisation of training prescriptions. Instead of relying on standardised exercise protocols, machine learning algorithms are capable of incorporating information about an individual’s baseline fitness level, comorbidities, and physiological responses to previous sessions in order to generate more tailored programs [

6,

12]. Such personalisation is clinically important because it minimises the risks of undertraining or overexertion and ensures that each participant receives a regimen optimised for both safety and effectiveness.

Another critical area is continuous monitoring. Wearable devices enhanced with AI now make it possible to track vital parameters such as heart rate, oxygen consumption, and movement patterns in real time [

7,

22]. The integration of these data streams into adaptive models allows exercise intensity to be dynamically adjusted as conditions change, bridging the gap between supervised clinical sessions and unsupervised activity in daily life. This capability not only supports patient safety but also provides clinicians with a more comprehensive understanding of patient progress outside the hospital or laboratory setting.

Equally important is promoting adherence, a longstanding challenge in cardiovascular rehabilitation. Reinforcement learning algorithms and adaptive digital platforms have demonstrated the ability to deliver motivational prompts that evolve according to patient behaviour [

9,

21]. By tailoring feedback to the individual’s level of engagement, mood, or activity pattern, these systems maintain interest and encourage consistent participation over time. This approach addresses one of the most persistent limitations of traditional rehabilitation programs, which often have high dropout rates after the initial months.

Finally, the scalability of AI-enabled interventions holds significant promise. Because these systems can automate elements of coaching, monitoring, and data analysis, they have the potential to extend effective rehabilitation services to much larger populations than would otherwise be feasible with clinician-led models alone. This is particularly relevant for resource-limited contexts, where specialist centres and trained staff are scarce [

11,

17]. By lowering the barriers to access and enabling remote supervision, AI can contribute to more equitable delivery of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation worldwide.

The first feasibility studies demonstrated how ML-based approaches could individualise training loads in cardiac rehabilitation [

6] and how early wearable technologies could support real-time monitoring of physical activity [

7]. Zhou et al. [

8] later confirmed, in one of the earliest randomised controlled trials (RCTs), that adaptive step goals generated through machine learning outperformed fixed prescriptions in improving daily activity levels. Similarly, Aguilera et al. [

9] showed that reinforcement learning could personalise text-message interventions, enhancing adherence in patients with comorbid conditions.

In subsequent years, the applications diversified further. Leitner et al. [

21] developed a fully digital AI health coach capable of autonomously guiding lifestyle modifications and reducing blood pressure. Hsiao et al. [

22] validated machine learning–driven VO₂ estimation from wearable sensors, supporting safe and effective home-based training. Xiao et al. [

12] demonstrated the utility of neural networks for exercise prescriptions in older adults, achieving improvements in VO₂max. Beyond direct interventions, Liang et al. [

10] improved diagnostic accuracy in exercise testing with deep learning, Puce et al. [

13] reviewed generative AI for training design, and Meder et al. [

11] highlighted population-level prevention strategies enabled by AI.

Despite this progress, the literature remains sparse and fragmented, with only eleven eligible studies identified, including just two RCTs [

8,

9]. Most investigations were exploratory, of a small scale, and conducted in technologically advanced settings. Ethical and regulatory concerns, including algorithmic transparency [

3,

23], patient data security, and equitable access [

11], further complicate the clinical implementation.

Therefore, the purpose of this review is to: (1) map the available studies that have applied AI in exercise-based cardiovascular interventions between 2015 and 2025; (2) examine their methodological approaches, study populations, and outcomes; and (3) identify achievements, limitations, and future priorities. Through this synthesis, the review aims to provide a clearer understanding of the potential for AI to enhance exercise-based cardiovascular care and outline the steps required for its safe and equitable translation into clinical practice [

25,

26].

2. Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

This scoping review was designed and conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines [

14]. The use of PRISMA-ScR provided a transparent and systematic structure, ensuring that all stages of the review—from literature search and study selection to data extraction and synthesis—were conducted in a reproducible and methodologically rigorous manner. By adhering to these guidelines, the review process aimed to minimise potential biases and to provide a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on the integration of artificial intelligence in exercise-based cardiovascular interventions.

The population further guided the review framework–concept–context (PCC) model. This model was chosen because of its suitability for scoping reviews, as it allows broad research questions to be addressed while still applying consistent eligibility parameters. The population component focused on human participants engaged in exercise-based interventions relevant to cardiovascular health. The concept was defined as the application of artificial intelligence, specifically machine learning and deep learning techniques, used to deliver, adapt, or monitor exercise interventions. The context referred to any healthcare or community-based setting in which these interventions were applied, including clinical rehabilitation programs, preventive health initiatives, and remote or home-based exercise delivery models.

Defining the review protocol in this structured way offered two primary advantages. First, it provided clarity and consistency in applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, ensuring that only relevant studies were considered. Second, it facilitated comparability across diverse study designs by mapping all eligible research onto the PCC framework. By doing so, the review not only captured early feasibility studies and pilot trials but also encompassed larger randomised controlled trials and validation studies, offering a broad yet coherent overview of the field.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

To ensure that the review captured only relevant and high-quality studies, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Eligible studies were restricted to peer-reviewed, original human research that applied artificial intelligence methods—specifically machine learning or deep learning—to the design, delivery, adaptation, or monitoring of exercise interventions with measurable cardiovascular outcomes. Such outcomes included, but were not limited to, blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen consumption (VO₂), VO₂max, exercise adherence, and diagnostic accuracy in exercise-related contexts.

Studies were excluded if they involved only animal models or laboratory-based simulations without human data, as these do not directly translate into clinical or rehabilitation settings. Similarly, investigations that employed AI solely for diagnostic purposes without incorporating an exercise intervention were not considered. Non–original works, such as reviews, editorials, commentaries, or study protocols lacking empirical data, were also excluded. These criteria ensured that the review remained focused on original, human-based research that demonstrated practical applications of AI within exercise-based cardiovascular health.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A systematic search strategy was developed to identify all relevant studies published between January 2015 and August 2025. Five major electronic databases were selected: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and IEEE Xplore. These databases were chosen for their comprehensive coverage of biomedical, health sciences, and engineering literature, ensuring a multidisciplinary approach to the topic.

The search combined both free-text terms and controlled vocabulary, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and equivalent indexing terms. Keywords such as “artificial intelligence,” “machine learning,” “deep learning,” “exercise,” “physical activity,” and “cardiovascular health” were systematically combined using Boolean operators. Filters were applied to restrict results to human studies and peer-reviewed publications. No language restrictions were applied, although all retrieved studies that met the eligibility criteria were published in English. The search strategy was designed to be broad enough to capture a wide range of applications while still targeting the specific intersection of AI, exercise, and cardiovascular health.

2.4. Study Selection

The study selection process followed a two-stage screening approach. First, titles and abstracts of all retrieved records were independently reviewed by two researchers. Studies that clearly did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded at this stage. In the second stage, the full texts of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed in detail against the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Any disagreements between the reviewers regarding eligibility were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. When necessary, a third reviewer was consulted to adjudicate. Duplicate publications were identified and removed before the screening process began. This rigorous and transparent approach ensured that only studies meeting the predetermined criteria were included in the final synthesis.

2.5. Data Extraction

Data were systematically extracted from each included study using a structured charting form. Extracted variables included the name of the first author, year of publication, country where the study was conducted, and the design of the study (e.g., randomised controlled trial, pilot study, feasibility study, validation trial). Information on population characteristics—such as sample size, age range, sex distribution, and relevant comorbidities—was also recorded.

Additionally, the type of AI methodology applied was identified, distinguishing between machine learning, deep learning, reinforcement learning, and generative models. The exercise modality was documented, including details of the intervention type, duration, frequency, and intensity. Cardiovascular outcomes were noted according to what was reported in the primary study, whether physiological (blood pressure, VO₂, VO₂max), behavioural (adherence, daily step counts), or diagnostic (accuracy in detecting coronary artery disease). Key findings were summarised to highlight the primary contributions of each investigation. This systematic extraction process ensured consistency and facilitated meaningful synthesis across studies with otherwise heterogeneous designs.

2.6. Data Synthesis

Given the methodological diversity of the included studies, data were synthesised descriptively rather than quantitatively. Randomised controlled trials were reported in detail with respect to intervention design, comparators, and measured outcomes. At the same time, pilot and feasibility studies were discussed narratively, with a focus on feasibility, acceptability, and proof-of-concept findings.

No meta-analysis was conducted, as the heterogeneity in study design, population, AI methodology, and outcome measures precluded statistical pooling. Instead, results were grouped thematically according to the primary application of AI—such as adaptive goal setting, digital coaching, wearable-based monitoring, exercise prescription engines, diagnostic augmentation, or population-level approaches. This thematic synthesis provided a structured overview of how AI has been integrated into exercise-based cardiovascular health interventions, highlighting both early achievements and areas requiring further research.

2.7. Statistics

Given the exploratory nature of this scoping review and the methodological heterogeneity of the included studies, no meta-analysis was performed. Instead, data were summarised descriptively. Study characteristics, including design, population, intervention type, and AI methodology, were tabulated to facilitate a structured comparison across studies. Cardiovascular outcomes—including blood pressure, exercise adherence, VO₂, VO₂max, and diagnostic accuracy—were reported narratively, with direct values cited from randomised controlled trials where available.

For pilot and feasibility studies, findings were presented qualitatively, focusing on feasibility, acceptability, and proof-of-concept results. Continuous outcomes, such as blood pressure changes or step count increases, were described in terms of mean differences and effect sizes when reported by the primary studies. Diagnostic performance metrics (e.g., area under the curve [AUC]) were presented as provided by the original authors. This descriptive statistical approach is consistent with PRISMA-ScR guidelines [

14] and was deemed most appropriate given the limited number of studies, their small sample sizes, and variability in intervention designs.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

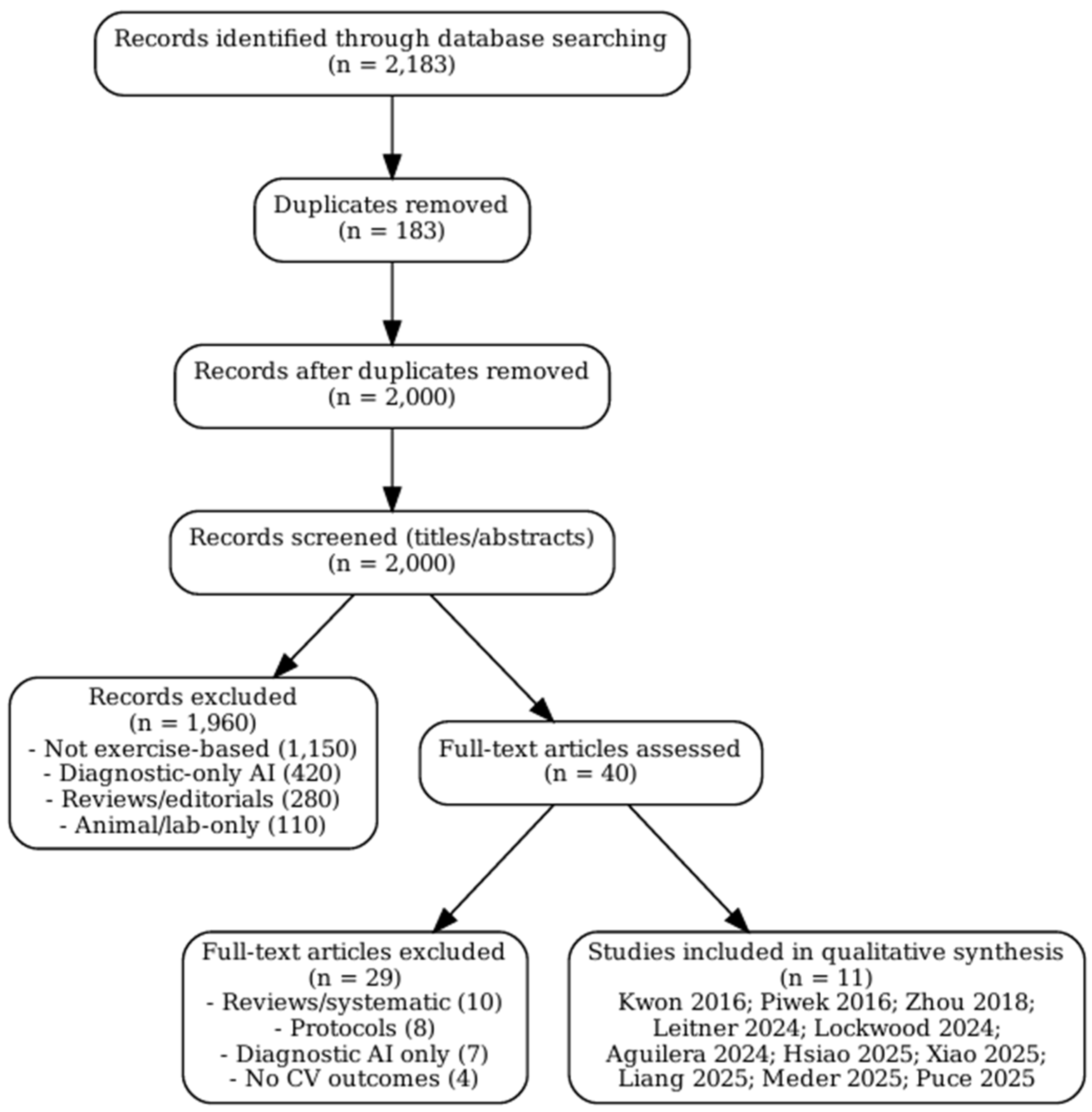

The initial database search identified a total of 2,183 records published between January 2015 and August 2025. Following the removal of duplicate entries, 2,000 unique records were retained for the screening process. Title and abstract screening served as the first stage of evaluation. During this step, the majority of articles were excluded because they clearly did not meet the predefined eligibility criteria. Common reasons for exclusion included studies that addressed artificial intelligence in purely diagnostic applications without incorporating exercise interventions, investigations limited to animal models, and papers that were not original research articles, such as reviews, commentaries, or theoretical discussions.

After this preliminary screening, 40 articles were considered sufficiently relevant to warrant full-text review. At this stage, each study was carefully examined against the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in the methods section. Particular attention was paid to whether AI methods were directly applied to exercise-based interventions and whether cardiovascular outcomes were reported. Studies that incorporated digital health tools but did not include an AI component, or that reported only usability data without physiological or behavioural endpoints, were excluded. Similarly, protocols that proposed but had not yet implemented AI-driven interventions were not included, as the focus of this review was on empirical evidence rather than planned or conceptual projects.

Of the 40 articles reviewed in full, 29 were excluded for reasons such as lack of cardiovascular outcome reporting, reliance on non-AI digital technologies, absence of exercise-based components, or insufficient methodological detail to assess the role of AI. Ultimately, 11 studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria and were selected for detailed synthesis in this review. These included two randomised controlled trials, several feasibility and pilot studies, and more recent validation or single-arm interventional trials.

The overall process of identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion followed the PRISMA-ScR framework [

14]. The flow of study selection is summarised in

Figure 1, which visually depicts the number of records identified, screened, reviewed in full, excluded, and finally included in the analysis. This structured approach ensured transparency and reproducibility in the selection of studies, while also providing a clear rationale for excluding records that did not meet the eligibility thresholds.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

The eleven studies included in this review displayed substantial diversity in terms of design, sample size, and clinical context, reflecting the early but rapidly developing nature of this research field. Several of the earliest contributions took the form of feasibility or pilot studies [

6,

7,

15]. These investigations were typically conducted with relatively small participant groups and short follow-up periods, focusing primarily on establishing the technical feasibility of integrating AI methods into exercise-based cardiovascular interventions. Although limited in scope, they provided important groundwork for later, more rigorous studies by demonstrating that AI-enabled tools could be effectively applied in real-world contexts.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) represented a smaller but highly influential portion of the evidence base. Two studies, those of Zhou et al. [

8] and Aguilera et al. [

9], utilised adaptive AI systems in behavioural interventions aimed at promoting physical activity. These trials enrolled larger and more diverse populations compared with pilot studies, and both demonstrated clear improvements in adherence and activity outcomes relative to traditional static prescriptions. The inclusion of RCTs within this body of literature is significant, as they offer the most substantial evidence to date that AI can enhance exercise interventions not only in terms of feasibility but also in clinical efficacy.

More recent contributions have expanded into validation and single-arm interventional designs [

12,

21,

22]. These studies tended to enrol moderately sized populations and evaluated more sophisticated AI applications, such as autonomous digital coaches, neural network–driven exercise prescriptions, and advanced wearable monitoring systems. For example, Leitner et al. [

21] focused on individuals with hypertension and tested an AI-powered digital health coach, while Hsiao et al. [

22] validated a wearable device capable of real-time VO₂ estimation. Xiao et al. [

12] examined older adults and applied neural networks to generate individualised prescriptions. These studies reflect a trend toward testing AI applications in more clinically meaningful scenarios, where physiological outcomes, such as blood pressure reduction or improvements in aerobic capacity, are systematically measured.

The populations included across the 11 studies were also heterogeneous. Some trials recruited patients actively participating in cardiac rehabilitation programs, while others targeted individuals with chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or depression. Additional studies focused on older adults at risk of cardiovascular decline, thereby expanding the potential reach of AI-enabled interventions beyond secondary prevention to include primary prevention and geriatric populations. The variety of participant groups underscores the versatility of AI applications but also highlights challenges in comparability, as different baseline risks and clinical goals complicate synthesis across studies.

Finally, geographical distribution was skewed toward technologically advanced healthcare settings, particularly in North America, Europe, and East Asia. This reflects both the concentration of AI research infrastructure in these regions and the reliance of most interventions on digital devices such as smartphones, wearable sensors, and internet connectivity. While these contexts provide ideal testbeds for innovation, they also raise questions about the applicability of findings to resource-limited environments, where infrastructure and access remain significant barriers [

11,

17].

In summary, the characteristics of the included studies reveal a research field still in its formative stages but marked by innovation and diversity. Designs ranged from small-scale feasibility pilots to RCTs and validation studies, populations spanned both clinical and community settings, and interventions addressed a spectrum of outcomes from adherence to physiological performance and diagnostic accuracy. This heterogeneity underscores both the promise and the challenges of synthesising the evidence base for AI in exercise-based cardiovascular care.

3.3. AI Applications in Exercise-Based Interventions

The studies included in this review applied artificial intelligence in diverse ways, reflecting both the breadth of available technologies and the evolving priorities in cardiovascular rehabilitation. One prominent application was adaptive goal setting. Zhou et al. [

8] tested a machine learning–based system that dynamically generated daily step goals according to the participant’s recent activity levels, ensuring that targets remained challenging but achievable. In a similar vein, Aguilera et al. [

9] implemented reinforcement learning to personalise motivational text messages, adjusting both content and frequency based on user engagement patterns. Together, these studies highlight how AI can replace static prescriptions with adaptive interventions that are more responsive to individual behaviours.

Digital coaching represented another primary domain of application. Leitner et al. [

21] deployed an autonomous AI health coach designed to deliver lifestyle recommendations tailored to blood pressure readings and activity data. This digital intervention not only reduced blood pressure but also demonstrated that AI could maintain high levels of engagement without continuous clinician input, pointing to its scalability and clinical potential.

Wearable-based monitoring was also widely explored. Piwek et al. [

7] investigated early consumer-grade wearable devices, recognising both their promise for tracking daily activity and the challenges related to sustained user adherence and data accuracy. More advanced approaches were developed by Hsiao et al. [

22], who validated an AI-driven multispectral photoplethysmography system capable of continuously estimating VO₂ in real time. This innovation provided a reliable tool for adjusting exercise intensity during unsupervised rehabilitation, bridging the gap between clinical assessments and at-home exercise.

Additionally, some studies focused on exercise prescription engines. Kwon et al. [

6] developed a machine learning–based platform capable of tailoring exercise recommendations to individual physiological responses. Xiao et al. [

12] extended this work by applying a back-propagation neural network to generate personalised exercise prescriptions for older adults, ultimately demonstrating improvements in aerobic performance. These contributions illustrate the potential of AI to refine and optimise the core component of rehabilitation: the exercise prescription itself.

AI has also been applied to augment diagnostic capacity. Liang et al. [

10] used deep learning models to analyse exercise stress test data, achieving improved accuracy in the detection of significant coronary artery disease. This application not only enhances diagnostic precision but also strengthens the link between exercise testing and rehabilitation planning, suggesting a broader integration of AI into the cardiovascular care continuum.

Finally, two studies broadened the scope beyond individual-level interventions. Puce et al. [

13] investigated generative AI as a tool for automated exercise program design, offering insights into how algorithms might assist clinicians in developing structured training regimens. Meder et al. [

11], on the other hand, approached AI from a population health perspective, underscoring its potential role in preventive strategies, risk stratification, and the scaling of rehabilitation programs across healthcare systems. Collectively, these studies illustrate the wide-ranging applications of AI, spanning personalised goal setting, monitoring, prescription, diagnostic enhancement, and even systemic approaches to public health.

3.4. Reported Outcomes

The reported outcomes across the included studies were equally diverse, reflecting the multiple dimensions in which AI may contribute to cardiovascular rehabilitation. Improvements in physical activity and adherence were among the most consistently reported findings. Zhou et al. [

8] demonstrated that machine learning–generated step goals significantly increased daily step counts compared with static prescriptions, while Aguilera et al. [

9] showed that reinforcement learning–driven text messaging improved adherence and sustained activity in individuals with diabetes and depression. These findings suggest that AI-based personalisation can help overcome one of the most persistent barriers in lifestyle interventions: maintaining long-term engagement.

Positive cardiovascular outcomes were also observed. Leitner et al. [

21] reported clinically meaningful reductions in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure among participants using an autonomous AI health coach. This highlights the potential of AI not only to encourage behaviour change but also to directly improve clinical risk factors associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Similarly, Xiao et al. [

12] documented significant gains in VO₂max and overall exercise capacity in older adults following neural network–driven individualised prescriptions, demonstrating that AI can enhance cardiorespiratory fitness in populations where functional decline is a pressing concern.

Continuous monitoring outcomes were validated by Hsiao et al. [

22], who showed that AI-based photoplethysmography could reliably estimate VO₂ during unsupervised rehabilitation. This capability enables the real-time adjustment of exercise intensity, thereby enhancing patient safety outside clinical environments. Kwon et al. [

6] further confirmed that machine learning–guided prescriptions could improve HR/VO₂ matching, increasing both the precision and adherence of prescribed training sessions.

In the diagnostic sphere, Liang et al. [

10] reported that their deep learning model achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.83 for the detection of significant coronary artery disease during exercise stress testing. This finding demonstrates how AI can bridge diagnostic and rehabilitative applications, supporting better patient stratification and intervention planning.

Beyond direct clinical outcomes, conceptual contributions were also noteworthy. Puce et al. [

13] highlighted the role of generative AI in designing exercise programs, framing it as a supportive tool for clinicians rather than a replacement for expertise. Meder et al. [

11] emphasised the potential for AI to scale preventive cardiovascular strategies at a population level, underscoring its relevance not only in individual rehabilitation but also in broader public health initiatives.

Taken together, these outcomes reflect AI’s capacity to generate improvements across multiple domains, including behavioral adherence, physiological fitness, cardiovascular risk factors, diagnostic accuracy, and healthcare system scalability. While preliminary, these findings collectively demonstrate AI’s promise as a transformative tool in cardiovascular rehabilitation.

4. Discussion

This scoping review reveals that, although the field is still developing, artificial intelligence (AI) has already demonstrated multiple pathways through which it can enhance exercise-based cardiovascular interventions. The most prominent contributions include personalising exercise prescriptions, adaptive goal setting, real-time monitoring via wearables, and utilising digital engagement strategies to enhance adherence. Collectively, these advances represent an early but tangible shift from standardised rehabilitation protocols toward more dynamic and individualised care.

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

The earliest exploratory studies in this area, notably those by Kwon et al. [

6] and Piwek et al. [

7], provided the first indications that AI techniques could be meaningfully integrated into exercise-based cardiovascular care. Kwon and colleagues demonstrated how machine learning algorithms, when paired with wearable sensors, could generate exercise prescriptions that adapted to the individual’s physiological responses rather than relying on generic recommendations. Although limited in scale and duration, this pilot study was instrumental in showing that exercise guidance could be personalised in a data-driven manner, moving beyond traditional standardised protocols. In parallel, Piwek and collaborators examined the emerging role of consumer-grade wearable technologies. They highlighted both the promise and limitations of such devices: on one hand, the ability to continuously capture physical activity data in free-living environments; on the other, the challenges of data quality, user adherence, and integration into structured clinical programs. These early works, while not definitive, served as proof-of-concept studies that opened the door for subsequent, more rigorous trials.

The first stronger evidence base was established in 2018. Zhou et al. [

8] conducted one of the earliest randomised controlled trials in this field and demonstrated that adaptive step goals, generated using machine learning, could substantially increase daily physical activity compared with fixed, non-individualised prescriptions. This was a pivotal finding because it showed that the use of adaptive algorithms could dynamically adjust targets in response to real-time performance, thereby maintaining motivation and engagement more effectively than static approaches

. Around the same time, Aguilera et al. [

9] tested a reinforcement learning–based system that delivered personalised text messages to individuals with diabetes and depression. Their trial revealed not only improved adherence but also higher daily step counts, emphasising the capacity of AI to sustain behavioural change in populations with complex comorbidities, who often present challenges for standard rehabilitation programs. Taken together, these two RCTs represented a turning point, as they provided the first controlled evidence that AI-enhanced personalisation could outperform conventional, one-size-fits-all interventions in promoting sustained physical activity.

Subsequent research advanced from feasibility toward clinical relevance. Leitner et al. [

21] implemented an autonomous AI health coach capable of delivering personalised lifestyle recommendations and demonstrated significant reductions in blood pressure among adults with hypertension. This study was notable not only for its outcomes but also for its scalability, suggesting that AI-driven interventions could provide practical guidance with minimal clinician involvement—a crucial factor in healthcare systems facing workforce shortages

. Meanwhile, Hsiao et al. [

22] validated a wearable device enhanced with AI algorithms to estimate oxygen consumption continuously using multispectral photoplethysmography. This innovation bridged a longstanding gap between laboratory-based cardiopulmonary testing and home-based rehabilitation, demonstrating that exercise intensity can be monitored and adjusted in real-time outside of supervised clinical environments. Xiao et al. [

12] extended the application of AI into geriatric care, applying a neural network model to design individualised exercise prescriptions for older adults, which resulted in measurable improvements in aerobic capacity and cardiorespiratory fitness. Together, these studies highlight a transition from exploratory work to clinically meaningful applications, demonstrating that AI-based tools can serve both preventive and rehabilitative purposes across diverse patient populations.

Other contributions expanded the scope beyond direct exercise prescription or monitoring. Liang et al. [

10] applied deep learning methods to exercise stress testing, achieving improved accuracy in detecting significant coronary artery disease. This line of work demonstrates how AI can serve not only as a rehabilitation tool but also as a diagnostic adjunct, thereby strengthening the continuum between disease detection, risk stratification, and therapeutic intervention. Puce et al. [

13] explored the potential of generative AI for program design, identifying opportunities to automate the creation of tailored exercise regimens, while also cautioning about the limitations of current models in capturing the nuance required for clinical application. Meder et al. [

11], in contrast, emphasised a macro-level perspective, examining how AI could contribute to population health through enhanced risk prediction, prevention strategies, and resource allocation. Taken together, these contributions illustrate that AI is not confined to the micro-level of individual patient management but may also serve as a systemic innovation capable of reshaping broader healthcare practices.

4.2. Clinical Implications

The findings of this review carry several important implications for clinical practice, particularly in the context of cardiac rehabilitation and preventive cardiology. AI-enabled tools have the capacity to optimise exercise prescriptions by matching training intensity and duration to individual physiological characteristics, thereby improving both safety and effectiveness. For example, machine learning–driven algorithms can analyse variables such as heart rate responses, baseline VO₂, or comorbid conditions to tailor exercise prescriptions in ways that conventional protocols cannot [

6,

12]. Such personalisation reduces the likelihood of undertraining or overexertion and allows programs to be fine-tuned to maximise clinical benefit.

Another central clinical implication is the ability of AI to enhance adherence, which is often the Achilles’ heel of long-term rehabilitation programs. By embedding reinforcement learning principles into digital coaching systems, AI can adjust motivational strategies in real-time, delivering tailored prompts that respond to patient progress and behavioural patterns [

9,

21]. Unlike static programs, these adaptive systems evolve in tandem with the patient, maintaining engagement over extended periods. This adaptability is particularly valuable given that most lifestyle interventions suffer from declining adherence after the first few months, undermining their long-term effectiveness.

The potential of hybrid care models deserves special emphasis. Rather than replacing clinicians, AI tools can function as supportive companions that automate repetitive tasks and extend clinical oversight into everyday life. For instance, digital health coaches can manage routine motivational messaging and feedback, while clinicians remain responsible for complex decision-making and treatment adjustments. Simultaneously, continuous AI-based monitoring can detect abnormal physiological responses—such as unexpected changes in heart rate variability or exercise tolerance—and trigger early warnings, thereby enabling timely clinical intervention. This dual role, combining automation with augmentation, is particularly valuable in the face of persistent shortages of healthcare personnel in rehabilitation programs worldwide.

In addition, AI may help overcome geographical and logistical barriers by extending cardiac rehabilitation into home and community settings. Wearable devices integrated with AI algorithms enable the remote monitoring of exercise intensity and safety parameters, reducing the need for frequent in-person visits [

22]. This shift could be transformative in rural or resource-limited regions, where access to specialised rehabilitation centres is restricted. By reducing dependence on hospital-based programs, AI systems have the potential to democratise access to rehabilitation services, making them available to broader and more diverse populations [

11,

17].

Another layer of clinical impact lies in the integration of AI-enabled rehabilitation with broader digital health infrastructures. Exercise data collected from wearables and mobile platforms can be incorporated into electronic health records, creating more comprehensive patient profiles. This integration not only improves continuity of care but also fosters interdisciplinary collaboration among cardiologists, physiotherapists, primary care physicians, and data scientists. When combined with telemedicine platforms, AI-driven exercise monitoring could enable clinicians to remotely supervise patients, adjust prescriptions in real-time, and maintain a continuous loop of feedback between patients and healthcare providers.

Ultimately, the clinical implications extend to the efficiency of the health system. By automating routine monitoring and patient engagement tasks, AI can reduce the burden on healthcare professionals and potentially lower the costs of rehabilitation programs. At the same time, the continuous data streams generated by AI tools provide opportunities for predictive analytics, allowing clinicians to identify patients at risk of non-adherence, poor outcomes, or adverse events before these occur. In this sense, AI not only personalises care at the individual level but also strengthens preventive strategies at the population level.

4.3. Ethical, Regulatory, and Practical Challenges

The promising results must be tempered by recognition of key challenges. Algorithmic opacity remains a pressing issue: many AI models function as black boxes with limited interpretability [

3,

23]. This reduces clinician trust and complicates the regulatory approval process. To facilitate clinical adoption, explainable AI (XAI) frameworks will be necessary, allowing healthcare professionals to comprehend how recommendations are generated and to validate them against established medical principles.

Access and equity represent another barrier. Interventions often depend on smartphones, wearable devices, and internet access, which are not universally available [

11]. Patients from low-resource regions, older adults with limited digital literacy, and those with socioeconomic barriers may be disproportionately excluded. Addressing this challenge requires designing interventions that are not only technologically sophisticated but also user-friendly, affordable, and adaptable to diverse contexts.

Privacy and data security are additional concerns. Continuous monitoring generates sensitive health data that necessitates robust protections to maintain patient trust and comply with ethical standards. The use of AI in exercise rehabilitation thus intersects with broader debates about data ownership, consent, and the use of secondary data. Transparent governance frameworks and secure infrastructures will be essential.

Finally, integration into healthcare systems is not straightforward. Clinicians require training to interpret AI-generated insights effectively, and healthcare systems must adapt their workflows and reimbursement models to support implementation [

25]. Without adjustments to organisational structures and reimbursement mechanisms, even the most effective AI systems may fail to achieve real-world uptake.

4.4. Research Gaps and Future Directions

The current body of evidence on AI-enabled exercise interventions for cardiovascular health is still relatively modest, fragmented, and characterised by considerable methodological heterogeneity. One of the most pressing priorities for the field is the design and implementation of large-scale, multicenter randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving diverse patient populations [

8,

9]. To date, only two RCTs have been conducted, both with encouraging results, but small sample sizes and population specificity limit the generalizability of their findings. Broader trials are necessary to validate efficacy across different demographic groups, clinical conditions, and healthcare contexts.

Another critical research direction is the establishment of standardised frameworks for validation, reporting, and evaluation [

14,

20]. At present, studies employ highly variable AI algorithms, exercise modalities, and outcome measures, which makes direct comparison difficult and undermines the ability to synthesise evidence quantitatively. Developing consensus-based methodological standards would not only improve comparability but also accelerate regulatory approval and clinical translation.

Equally important is the need to ensure that AI models are transparent and explainable [

3,

23]. The current reliance on “black-box” deep learning approaches has generated scepticism among clinicians, who are hesitant to adopt systems they cannot fully interpret. Investment in explainable AI (XAI) research is therefore essential, as it can help align algorithmic outputs with medical reasoning, facilitate clinician acceptance, and strengthen patient trust.

Integration of AI into real-world healthcare delivery remains another unresolved challenge. Future studies must examine not only technical performance but also cost-effectiveness, workflow compatibility, and the impact on clinician workload [

11,

25]. Without clear evidence that AI tools improve efficiency and reduce costs, healthcare systems may be reluctant to adopt them, regardless of their potential benefits.

Equity of access also warrants attention. Most existing studies have been conducted in technologically advanced settings, where participants have ready access to smartphones, wearable devices, and stable internet connections. To ensure that AI-driven rehabilitation does not exacerbate existing health disparities, research should deliberately include underrepresented populations and be tested in low-resource environments [

11]. This may involve designing low-cost, simplified platforms or integrating AI solutions into community-based care models that can function even with limited infrastructure.

Finally, progress will require interdisciplinary collaboration that extends beyond the traditional boundaries of cardiology and exercise science. Effective implementation of AI requires cooperation among clinicians, data scientists, biomedical engineers, behavioural scientists, and policymakers [

25,

26]. Such collaboration can help ensure that technological innovations are clinically relevant, ethically sound, and scalable across different health systems.

Beyond these immediate priorities, it will also be essential to evaluate long-term outcomes of AI-enabled interventions. Future studies should determine whether initial improvements in adherence, blood pressure, or VO₂max translate into sustained reductions in morbidity, mortality, and healthcare utilisation. Moreover, opportunities exist to explore synergies between AI and other emerging technologies—including virtual reality, gamification strategies, and digital twins—which could further enhance personalisation, engagement, and predictive accuracy.

If these goals are met, AI has the potential to evolve from exploratory feasibility tools into established, evidence-based components of cardiovascular rehabilitation. Such progress would not only support the shift toward precision exercise medicine but also contribute to population-level strategies for reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease. Ultimately, success will depend not only on continuous technical innovation but also on ensuring that AI systems are explainable, equitable, and seamlessly integrated into clinical practice.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review synthesised evidence on AI in exercise-based cardiovascular interventions. Eleven studies illustrated AI’s ability to personalise exercise prescriptions [

6,

12], set adaptive activity goals [

8,

9], support continuous monitoring [

7,

22], and improve adherence [

9,

21]. Diagnostic and generative applications further expanded the scope [

10,

13].

AI has the potential to overcome persistent barriers in rehabilitation and prevention by aligning with the principles of precision medicine [

25,

26]. However, the evidence remains preliminary. More RCTs, harmonised methods, and studies in diverse populations are urgently needed. Ethical and equity concerns—including algorithmic transparency [

3,

23], data protection, and accessibility [

11]—must be addressed before large-scale adoption.

AI should be seen as a complementary tool that enhances, rather than replaces, clinical expertise. With rigorous validation, transparent frameworks, and equitable implementation, AI could help shift cardiovascular rehabilitation toward flexible, hybrid models that extend care beyond hospital walls and ultimately reduce the global burden of disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and E.K.; methodology, A.D., P.S., P.D. and E.K.; software, P.S. and P.D..; validation, A.D., P.S.,P.D. and E.K.; formal analysis, P.D. and E.K.; investigation, A.D., P.S., P.D. and E.K.; data curation A.D., P.S., P.D. and E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.and E.K.; writing—review and editing, A.D., P.S., P.D. and E.K.; supervision, A.D., and E.K.; project administration, A.D..; funding acquisition, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.