Submitted:

27 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

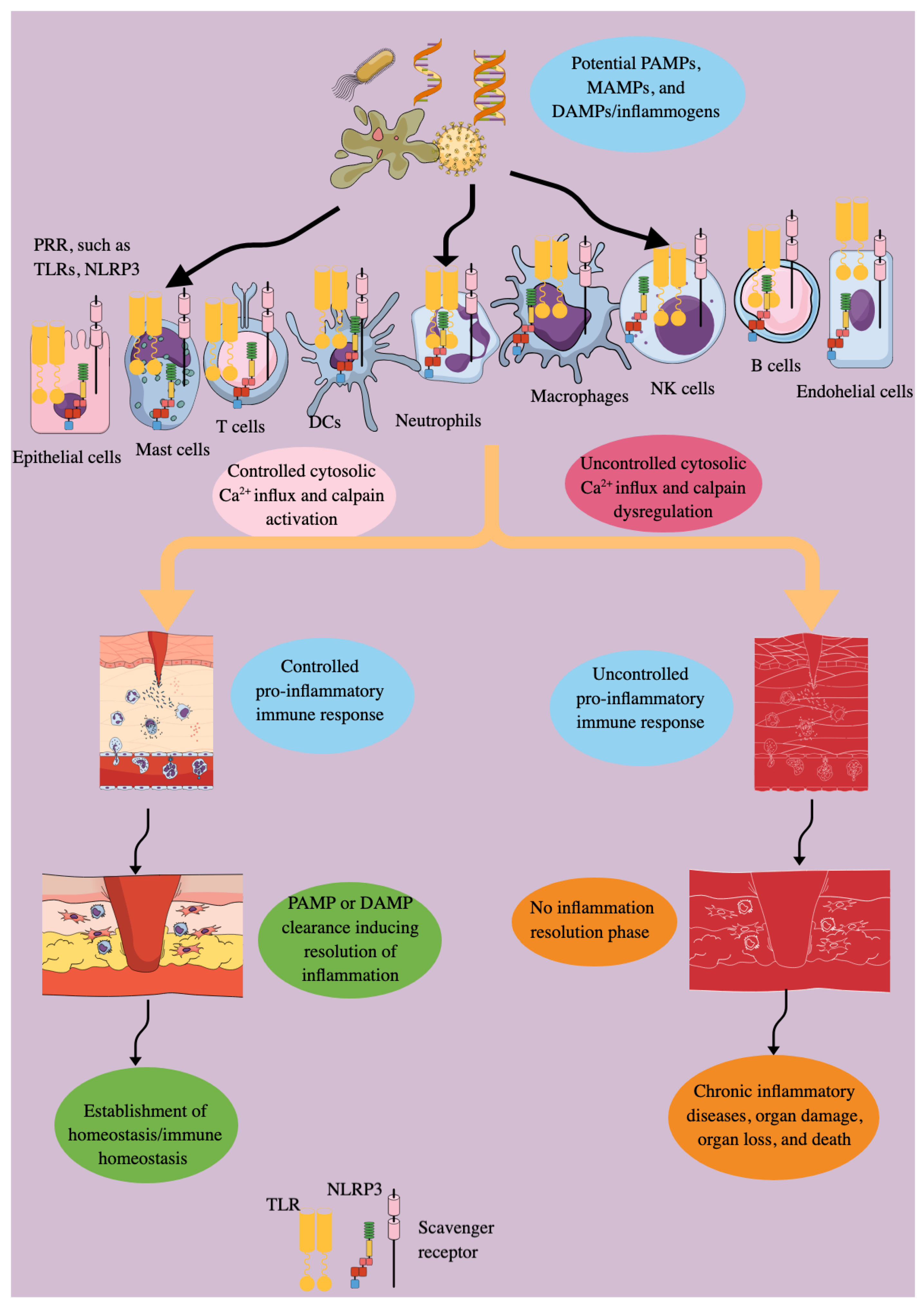

The controlled pro-inflammatory immune response is critical for fighting against external and endogenous threats, such as microbes/pathogens, allergens, xenobiotics, various antigens, and dying host cells and their mediators (DNA, RNA, and nuclear proteins) released into the circulation and cytosol (PAMPs, MAMPs, and DAMPs). Several pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and their downstream adaptor molecules, expressed by innate and adaptive immune cells, are critical in generating the inflammatory immune response by recognizing PAMPs, MAMPs, and DAMPs. However, their dysregulation may predispose the host to develop inflammation-associated organ damage, neurodegeneration, autoimmunity, cancer, and even death due to the absence of the inflammation resolution phase. The cytosolic calcium (Ca2+) level regulates the survival, proliferation, and immunological functions of immune cells. Cysteine-rich proteases, specifically calpains, are Ca2+-dependent proteases that become activated during inflammatory conditions, playing a critical role in the inflammatory process and associated organ damage. Therefore, this article discusses the expression and function of calpains 1 and 2 (ubiquitous calpains) in various innate (epithelial, endothelial, dendritic, mast, and NK cells, as well as macrophages) and adaptive (T and B cells) immune cells, affecting inflammation and immune regulation. As inflammatory diseases are on the rise due to several factors, such as environment, lifestyle, and an aging population, we must not just investigate, but strive for a deeper understanding of the inflammation and immunoregulation under the calpain system (calpain 1 and 2 and their endogenous negative regulator calpastatin) lens, which is ubiquitous and senses cytosolic Ca2+ changes to impact immune response.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Inflammation and Immune Dysregulation Are Keys to Disease Pathologies

3. Calpain Expression and Their Actions in Different Immune (Innate and Adaptive) Cells

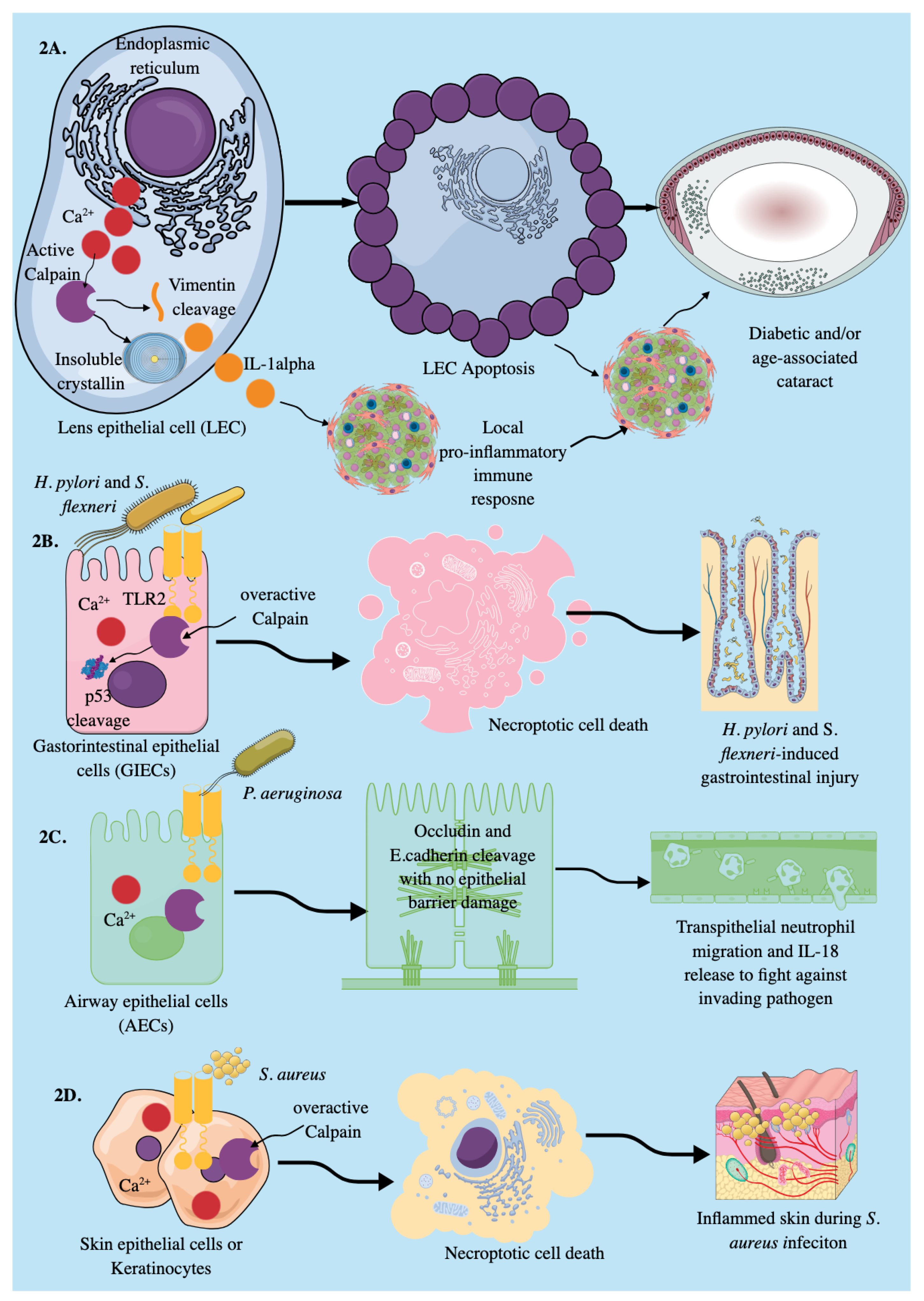

3.1. Epithelial Cells

Signaling Events Inducing Calpain Activation in Epithelial Cells to Induce Their Immunological Functions

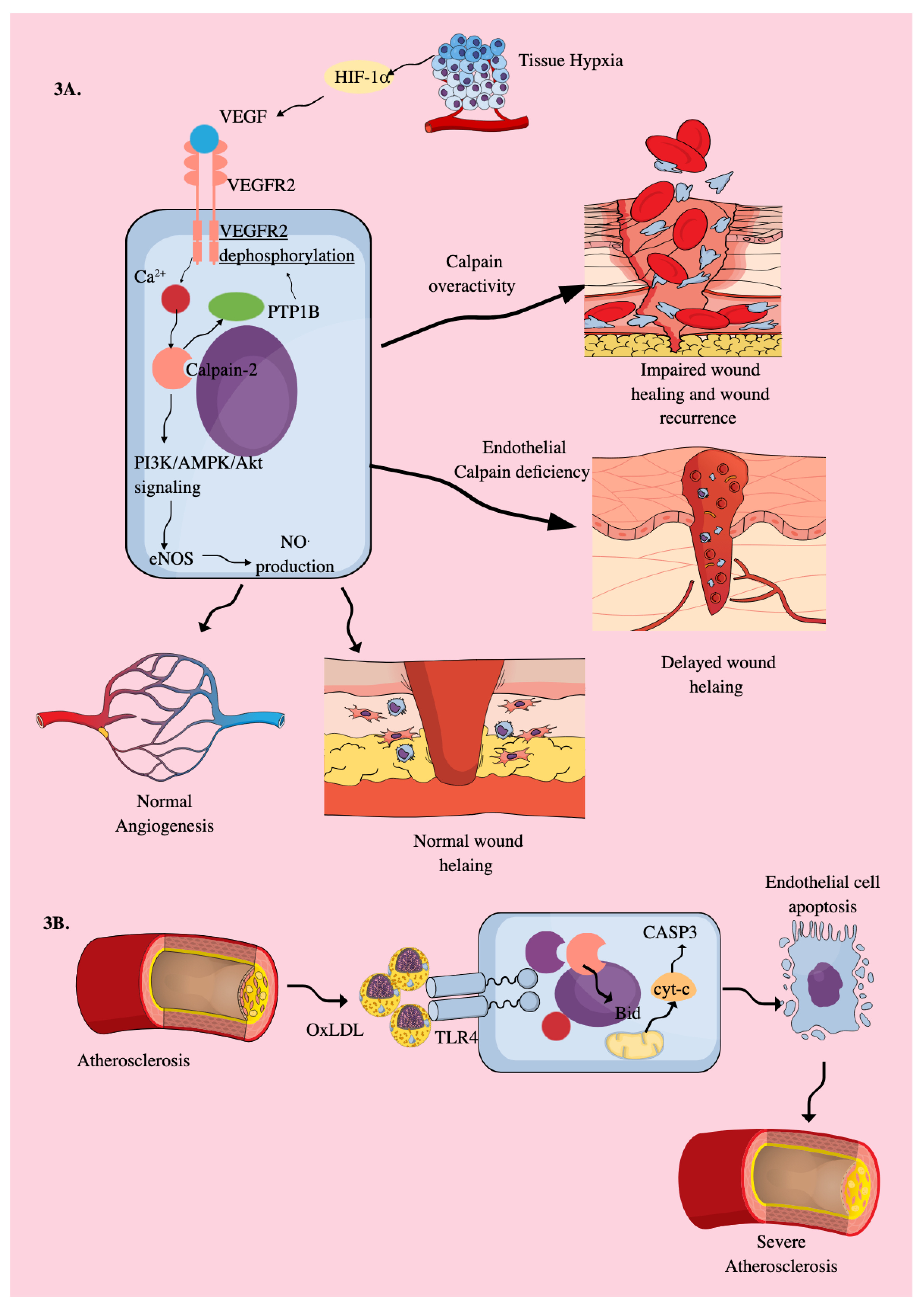

3.2. Endothelial Cells

3.3. Calpains in Myeloid Innate Immune Cells (MICs)

3.3.1. Macrophages:

3.3.2. Neutrophils

3.3.3. DCs

3.3.4. Mast Cells

4. Calpains in Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILCs)

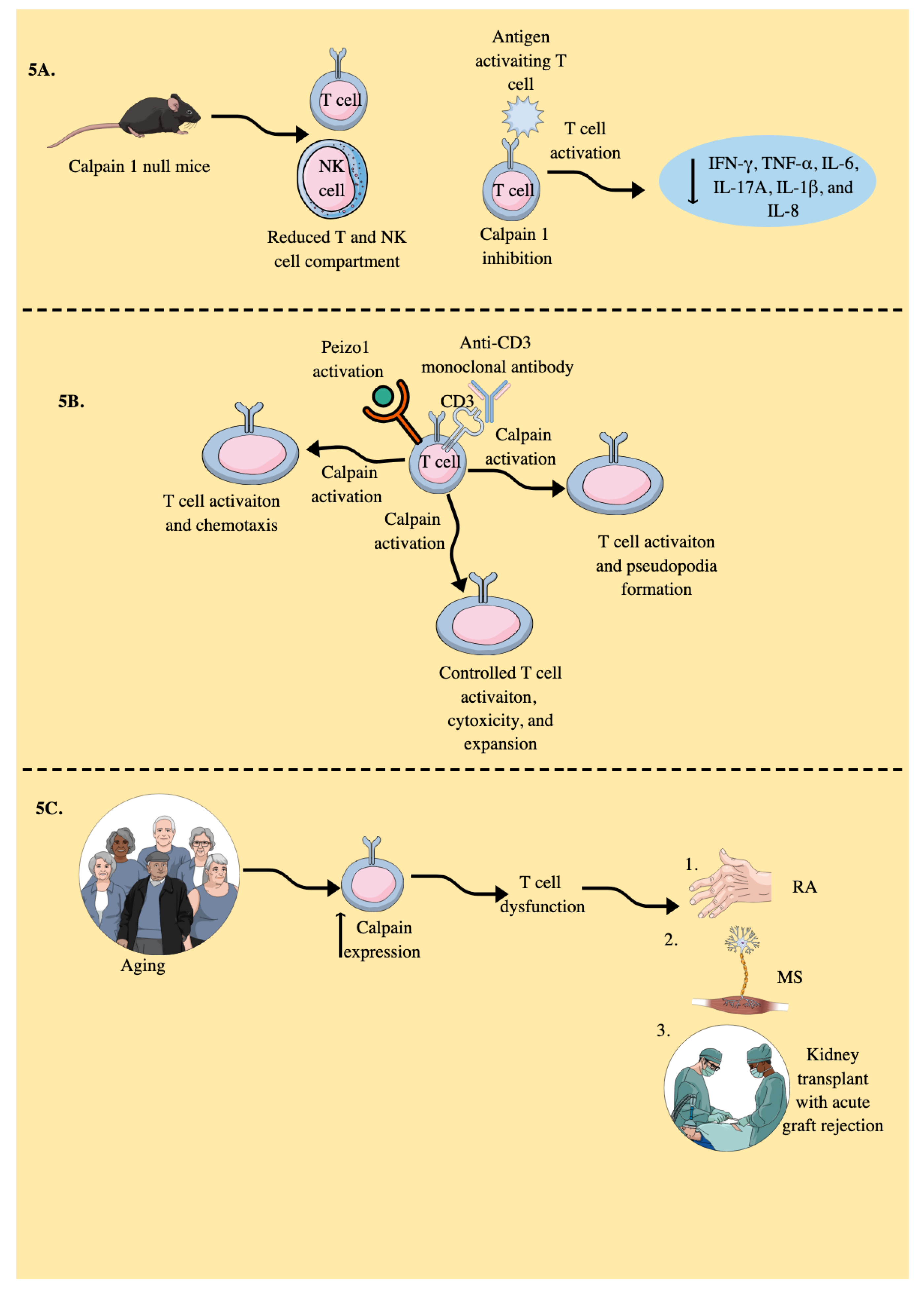

5. Calpains in T Cells

6. Calpains in B Cells

7. Future Perspectives and Conclusion

Author Contribution

Funding

Institutional Review Board

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Figure conceptualization and design

References

- Kumar, V.; Stewart, J.H.t. Immune Homeostasis: A Novel Example of Teamwork. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2782, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobs, S.P.; Kopf, M. Tissue-resident macrophages: Guardians of organ homeostasis. Trends in Immunology 2021, 42, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, J.I.; Farber, D.L. Tissue-Resident Immune Cells in Humans. Annu Rev Immunol 2022, 40, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, T.; Palendira, U.; Tscharke, D.C.; Bedoui, S. Tissue-resident memory T cells in tissue homeostasis, persistent infection, and cancer surveillance. Immunol Rev 2018, 283, 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parijs, L.V.; Abbas, A.K. Homeostasis and Self-Tolerance in the Immune System: Turning Lymphocytes off. Science 1998, 280, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatenoud, L. Teaching the immune system “self” respect and tolerance. Science 2014, 344, 1343–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halper-Stromberg, A.; Jabri, B. Maladaptive consequences of inflammatory events shape individual immune identity. Nature Immunology 2022, 23, 1675–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goll, D.E.; Thompson, V.F.; Li, H.; Wei, W.; Cong, J. The calpain system. Physiol Rev 2003, 83, 731–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.A.; Campbell, R.L.; Davies, P.L. Calcium-bound structure of calpain and its mechanism of inhibition by calpastatin. Nature 2008, 456, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, A.; Thompson, V.F.; Goll, D.E. Interaction of calpastatin with calpain: A review. Biol Chem 2004, 385, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glading, A.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; Wells, A. Cutting to the chase: Calpain proteases in cell motility. Trends in Cell Biology 2002, 12, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.J.; Huttenlocher, A. Regulating cell migration: Calpains make the cut. Journal of Cell Science 2005, 118, 3829–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Takeichi, M. NMDA-Receptor Activation Induces Calpain-Mediated β-Catenin Cleavages for Triggering Gene Expression. Neuron 2007, 53, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollino, D.; Balan, I.; Aurelian, L. Valproic acid induces neuronal cell death through a novel calpain-dependent necroptosis pathway. J Neurochem 2015, 133, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.A.; Fairgrieve, M.R.; Den Hartigh, A.; Yakovenko, O.; Duvvuri, B.; Lood, C.; Thomas, W.E.; Fink, S.L.; Gale, M. Calpain drives pyroptotic vimentin cleavage, intermediate filament loss, and cell rupture that mediates immunostimulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 5061–5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. Toll-like receptors in immunity and inflammatory diseases: Past, present, and future. Int Immunopharmacol 2018, 59, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Inflammation research sails through the sea of immunology to reach immunometabolism. International Immunopharmacology 2019, 73, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Stewart IV, JH, Toll-Like Receptors in Immunity and Inflammation. In Thirty Years since the Discovery of Toll-Like Receptors, Kumar, V. Ed. IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2024.

- Kumar, V.; Stewart, J.H. t. cGLRs Join Their Cousins of Pattern Recognition Receptor Family to Regulate Immune Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Toll-Like Receptors in Adaptive Immunity. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2022, 276, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.C.; Jha, S.; Linhoff, M.W.; Ting, J.P. The NLR gene family: From discovery to present day. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.D.; Willment, J.A.; Whitehead, L. C-type lectins in immunity and homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol 2018, 18, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canton, J.; Neculai, D.; Grinstein, S. Scavenger receptors in homeostasis and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. The Trinity of cGAS, TLR9, and ALRs Guardians of the Cellular Galaxy Against Host-Derived Self-DNA. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 624597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. The complement system, toll-like receptors and inflammasomes in host defense: Three musketeers’ one target. Int Rev Immunol 2019, 38, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Zou, J.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Pattern recognition receptors: Function, regulation and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Slavik, K.M.; Toyoda, H.C.; Morehouse, B.R.; de Oliveira Mann, C.C.; Elek, A.; Levy, S.; Wang, Z.; Mears, K.S.; Liu, J.; Kashin, D.; Guo, X.; Mass, T.; Sebé-Pedrós, A.; Schwede, F.; Kranzusch, P.J. cGLRs are a diverse family of pattern recognition receptors in innate immunity. Cell 2023, 186, 3261–3276.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.L.; Pasare, C.; Barton, G.M. Control of adaptive immunity by pattern recognition receptors. Immunity 2024, 57, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, Z.; Wu, C.H.; Ding, P. A Comparative Overview of the Intracellular Guardians of Plants and Animals: NLRs in Innate Immunity and Beyond. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2021, 72, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Stewart Iv, J.H. Pattern-Recognition Receptors and Immunometabolic Reprogramming: What We Know and What to Explore. J Innate Immun 2024, 16, 295–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. A STING to inflammation and autoimmunity. J Leukoc Biol 2019, 106, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okin, D.; Medzhitov, R. Evolution of inflammatory diseases. Curr Biol 2012, 22, R733–R740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, J.P. Inflammation and Its Role in Regeneration and Repair. Circ Res 2019, 124, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurora, A.B.; Olson, E.N. Immune Modulation of Stem Cells and Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. Inflammasomes: Pandora’s box for sepsis. J Inflamm Res 2018, 11, 477–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; Miller, A.H.; Mantovani, A.; Weyand, C.M.; Barzilai, N.; Goronzy, J.J.; Rando, T.A.; Effros, R.B.; Lucia, A.; Kleinstreuer, N.; Slavich, G.M. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature Medicine 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszka, Z.; Jenei, V.; Mácsik, R.; Mezhonova, E.; Diyab, S.; Csősz, R.; Bácsi, A.; Mázló, A.; Koncz, G. Life-threatening risk factors contribute to the development of diseases with the highest mortality through the induction of regulated necrotic cell death. Cell Death & Disease 2025, 16, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Jin, Y.; Xing, Y.; Abate, M.D.; Abbasian, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, Z.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelmasseh, M.; Abdollahifar, M.-A.; Abdulah, D.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence of six major immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; You, H.; Zheng, K.; Tang, R.; Zheng, C. The crosstalk between pattern-recognition receptor signaling and calcium signaling. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 192, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ahmad, A. Targeting calpains: A novel immunomodulatory approach for microbial infections. Eur J Pharmacol 2017, 814, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Everingham, S.; Hall, C.; Greer, P.A.; Craig, A.W.B. Calpains promote neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in an acute bacterial peritonitis model. European Journal of Immunology 2014, 44, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Prince, A. TLR2-induced calpain cleavage of epithelial junctional proteins facilitates leukocyte transmigration. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Tian, X.; Sun, H.; Liu, H.; Lu, M.; Wang, H. Calpain-1 mediates vascular remodelling and fibrosis via HIF-1α in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. J Cell Mol Med 2022, 26, 2819–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Xu, Y.; Mericle, M.T.; Mellgren, R.L. Participation of the conventional calpains in apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1590, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horbach, N.; Kalinka, M.; Ćwilichowska-Puślecka, N.; Al Mamun, A.; Mikołajczyk-Martinez, A.; Turk, B.; Snipas, S.J.; Kasperkiewicz, P.; Groborz, K.M.; Poręba, M. Visualization of calpain-1 activation during cell death and its role in GSDMD cleavage using chemical probes. Cell Chem Biol 2025, 32, 603–619.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, R.; Li, Y.; Shui, L.; Ni, L.; Zhang, A. The role of pyroptosis in inflammatory diseases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Hsu, J.-M.; Hung, M.-C. Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis in inflammation and antitumor immunity. Molecular Cell 2021, 81, 4579–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broz, P. Pyroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and roles in disease. Cell Research 2025, 35, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, J.; Katti, R.; Scott, M.J. The Role of Gasdermin-D-Mediated Pyroptosis in Organ Injury and Its Therapeutic Implications. Organogenesis 2023, 19, 2177484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleimer, R.P.; Kato, A.; Kern, R.; Kuperman, D.; Avila, P.C. Epithelium: At the interface of innate and adaptive immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007, 120, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, I.; Ye, F.; McNally, B.; Willette, M.; Flaño, E. Toll-Like Receptor Expression and Induction of Type I and Type III Interferons in Primary Airway Epithelial Cells. Journal of Virology 2013, 87, 3261–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yan, H. Mucosal epithelial cells: The initial sentinels and responders controlling and regulating immune responses to viral infections. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 2021, 18, 1628–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bals, R.; Hiemstra, P.S. Innate immunity in the lung: How epithelial cells fight against respiratory pathogens. European Respiratory Journal 23, (2), 327-333. [CrossRef]

- Pott, J.; Hornef, M. Innate immune signalling at the intestinal epithelium in homeostasis and disease. EMBO reports 2012, 13, 684–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.J.; Lloyd, C.M. Regulation of immune responses by the airway epithelial cell landscape. Nature Reviews Immunology 2021, 21, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, M.H.; Kuijk, E.W.; Nieuwenhuis, E.E.S. Innate immunity of the gut epithelium: Blowing in the WNT? Mucosal Immunology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, D.A.; Nice, T.J.; Rauch, I. Innate immune sensing by epithelial barriers. Curr Opin Immunol 2021, 73, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, S.L.; Goldblatt, D.L.; Evans, S.E.; Tuvim, M.J.; Dickey, B.F. Airway Epithelial Innate Immunity. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, A.; Schleimer, R.P. Beyond inflammation: Airway epithelial cells are at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2007, 19, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, C.C.; Yu, A.; Heroux, D.; Akhabir, L.; Sandford, A.J.; Neighbour, H.; Denburg, J.A. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) secretion from human nasal epithelium is a function of TSLP genotype. Mucosal Immunol 2015, 8, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebina-Shibuya, R.; Leonard, W.J. Role of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in allergy and beyond. Nature Reviews Immunology 2023, 23, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatton, C.F.; Botting, R.A.; Dueñas, M.E.; Haq, I.J.; Verdon, B.; Thompson, B.J.; Spegarova, J.S.; Gothe, F.; Stephenson, E.; Gardner, A.I.; et al. Delayed induction of type I and III interferons mediates nasal epithelial cell permissiveness to SARS-CoV-2. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Sharma, S.; Roy, S.; Varma, S.; Bose, M. Pulmonary epithelial cells are a source of interferon-gamma in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Immunol Cell Biol 2007, 85, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, H.S.; Elvington, M.L.; Perng, Y.-C.; Liszewski, M.K.; Byers, D.E.; Farkouh, C.; Yusen, R.D.; Lenschow, D.J.; Brody, S.L.; Atkinson, J.P. Intracellular C3 Protects Human Airway Epithelial Cells from Stress-associated Cell Death. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 2019, 60, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, D.H.; Starick, M.; Aponte Alburquerque, R.; Kulkarni, H.S. Local complement activation and modulation in mucosal immunity. Mucosal Immunology 2024, 17, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N.; Jayaraman, A.; Reinhardt, C.; Campbell, J.D.; Bosmann, M. A single-cell lung atlas of complement genes identifies the mesothelium and epithelium as prominent sources of extrahepatic complement proteins. Mucosal Immunology 2022, 15, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, H.S.; Liszewski, M.K.; Brody, S.L.; Atkinson, J.P. The complement system in the airway epithelium: An overlooked host defense mechanism and therapeutic target? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 141, 1582–1586.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.K.; Ozantürk, A.N.; Kulkarni, D.H.; Ma, L.; Barve, R.A.; Dannull, L.; Lu, A.; Starick, M.; McPhatter, J.N.; Garnica, L.; Sanfillipo-Burchman, M.; Kunen, J.; Wu, X.; Gelman, A.E.; Brody, S.L.; Atkinson, J.P.; Kulkarni, H.S. Lung epithelial cell–derived C3 protects against pneumonia-induced lung injury. Science Immunology 2023, 8, eabp9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.T.; Tsukamoto, T.; Nigam, S.K. Selective degradation of E-cadherin and dissolution of E-cadherin-catenin complexes in epithelial ischemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2000, 278, F847–F852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Shearer, T.R.; Azuma, M. Loss of Calpastatin Leads to Activation of Calpain in Human Lens Epithelial Cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2014, 55, 5278–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasl, J.; Caslavsky, J.; Grusanovic, J.; Chvalova, V.; Kosla, J.; Adamec, J.; Grousl, T.; Klimova, Z.; Vomastek, T. Depletion of calpain2 accelerates epithelial barrier establishment and reduces growth factor-induced cell scattering. Cellular Signalling 2024, 121, 111295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Kim, M.S.; Chung, S.K. Calpain and Caspase-12 Expression in Lens Epithelial Cells of Diabetic Cataracts. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2016, 167, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Harris, F.; Dennison, S.; Singh, J.; Phoenix, D.A. Calpains: Targets of cataract prevention? Trends in Molecular Medicine 2004, 10, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.D.; Johar, K.; Vasavada, A. Causative and preventive action of calcium in cataractogenesis. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2004, 25, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, S.; Harris, F.; Singh, J.; Phoenix, D. Role of calpains in diabetes mellitus-induced cataractogenesis: A mini review. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2004, 261, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yao, K.; Fu, Q.L. Potential immune involvement in cataract: From mechanisms to future scope of therapies. Int J Ophthalmol 2025, 18, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmunol 2019, 332, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Toll-like receptors in sepsis-associated cytokine storm and their endogenous negative regulators as future immunomodulatory targets. International Immunopharmacology 2020, 89, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño, J.F.; Abreu, M.T. Epithelial Toll-like receptors and their role in gut homeostasis and disease. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2020, 17, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribar, S.C.; Richardson, W.M.; Sodhi, C.P.; Hackam, D.J. No Longer an Innocent Bystander: Epithelial Toll-Like Receptor Signaling in the Development of Mucosal Inflammation. Molecular Medicine 2008, 14, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakoff-Nahoum, S.; Paglino, J.; Eslami-Varzaneh, F.; Edberg, S.; Medzhitov, R. Recognition of Commensal Microflora by Toll-Like Receptors Is Required for Intestinal Homeostasis. Cell 2004, 118, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soranno, D.E.; Coopersmith, C.M.; Brinkworth, J.F.; Factora, F.N.F.; Muntean, J.H.; Mythen, M.G.; Raphael, J.; Shaw, A.D.; Vachharajani, V.; Messer, J.S. A review of gut failure as a cause and consequence of critical illness. Critical Care 2025, 29, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, Q.; Truong-Tran, A.Q.; Plitt, J.R.; Beck, L.A.; Schleimer, R.P. Activation of airway epithelial cells by toll-like receptor agonists. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004, 31, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengroth, L.; Millrud, C.R.; Kvarnhammar, A.M.; Kumlien Georén, S.; Latif, L.; Cardell, L.-O. Functional Effects of Toll-Like Receptor (TLR)3, 7, 9, RIG-I and MDA-5 Stimulation in Nasal Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Invernizzi, R.; Lloyd, C.M.; Molyneaux, P.L. Respiratory microbiome and epithelial interactions shape immunity in the lungs. Immunology 2020, 160, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, X. Lung microbiome: New insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, R.L.; Rorke, E.A. Molecular biology of keratinocyte differentiation. Environ Health Perspect 1989, 80, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Going, Toll-like receptors in skin inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Excli j 2021, 20, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Kim, T.-G.; Ryu, J.-H. Conversation between skin microbiota and the host: From early life to adulthood. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2025, 57, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, L.; Grice, E.A. The Skin Microbiota: Balancing Risk and Reward. Cell Host & Microbe 2020, 28, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Chen, T.; Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Yu, Z.; Xie, B.; Qian, C.; Xu, S.; Li, N.; Cao, X.; Wang, J. Extracellular calcium elicits feedforward regulation of the Toll-like receptor-triggered innate immune response. Cell Mol Immunol 2017, 14, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birla, H.; Xia, J.; Gao, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F.; Patel, S.; Amponsah, A.; Bekker, A.; Tao, Y.-X.; Hu, H. Toll-like receptor 4 activation enhances Orai1-mediated calcium signal promoting cytokine production in spinal astrocytes. Cell Calcium 2022, 105, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Kim, S.H.; Das, A.; Yang, S.-N.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, M.K.; Berggren, P.-O.; Lee, Y.; Chai, J.C.; Kim, H.J.; Chai, Y.G. TLR3-/4-Priming Differentially Promotes Ca2+ Signaling and Cytokine Expression and Ca2+-Dependently Augments Cytokine Release in hMSCs. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 23103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K.A.; Kagan, J.C. Toll-like Receptors and the Control of Immunity. Cell 2020, 180, 1044–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zanoni, I.; Cullen, T.W.; Goodman, A.L.; Kagan, J.C. Mechanisms of Toll-like Receptor 4 Endocytosis Reveal a Common Immune-Evasion Strategy Used by Pathogenic and Commensal Bacteria. Immunity 2015, 43, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, J.C.; Su, T.; Horng, T.; Chow, A.; Akira, S.; Medzhitov, R. TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon-beta. Nat Immunol 2008, 9, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, T.E.; Mathmann, C.D.; Domínguez Cadena, L.C.; Muusse, T.W.; Kim, H.; Wells, J.W.; Ulett, G.C.; Hamerman, J.A.; Brooks, A.J.; Kobe, B.; Sweet, M.J.; Stacey, K.J.; Blumenthal, A. TLR4 endocytosis and endosomal TLR4 signaling are distinct and independent outcomes of TLR4 activation. EMBO reports 2025, 26, 2740–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack, J.; Doyle, S.L.; Connolly, D.J.; Reinert, L.S.; O’Keeffe, K.M.; McLoughlin, R.M.; Paludan, S.R.; Bowie, A.G. TRAM is required for TLR2 endosomal signaling to type I IFN induction. J Immunol 2014, 193, 6090–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Dios, R.; Nguyen, L.; Ghosh, S.; McKenna, S.; Wright, C.J. CpG-ODN-mediated TLR9 innate immune signalling and calcium dyshomeostasis converge on the NFκB inhibitory protein IκBβ to drive IL1α and IL1β expression. Immunology 2020, 160, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.M.; Lapointe, T.K.; Jackson, S.; Beck, P.L.; Jones, N.L.; Buret, A.G. Helicobacter pylori Activates Calpain via Toll-Like Receptor 2 To Disrupt Adherens Junctions in Human Gastric Epithelial Cells. Infection and Immunity 2011, 79, 3887–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergounioux, J.; Elisee, R.; Prunier, A.-L.; Donnadieu, F.; Sperandio, B.; Sansonetti, P.; Arbibe, L. Calpain Activation by the Shigella flexneri Effector VirA Regulates Key Steps in the Formation and Life of the Bacterium’s Epithelial Niche. Cell Host & Microbe 2012, 11, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapaquette, P.; Fritah, S.; Lhocine, N.; Andrieux, A.; Nigro, G.; Mounier, J.; Sansonetti, P.; Dejean, A. Shigella entry unveils a calcium/calpain-dependent mechanism for inhibiting sumoylation. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritah, S.; Lhocine, N.; Golebiowski, F.; Mounier, J.; Andrieux, A.; Jouvion, G.; Hay, R.T.; Sansonetti, P.; Dejean, A. Sumoylation controls host anti-bacterial response to the gut invasive pathogen Shigella flexneri. EMBO Rep 2014, 15, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karhausen, J.; Ulloa, L.; Yang, W. SUMOylation Connects Cell Stress Responses and Inflammatory Control: Lessons From the Gut as a Model Organ. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 646633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eislmayr, K.D.; Nichols, C.A.; Liu, F.L.; Yuvaraj, S.; Babirye, J.P.; Roncaioli, J.L.; Vickery, J.; Barton, G.M.; Lesser, C.F.; Vance, R.E. Macrophages orchestrate elimination of Shigella from the intestinal epithelial cell niche via TLR-induced IL-12 and IFN-γ. Cell Host & Microbe 2025, 33, 1535–1549.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pore, D.; Mahata, N.; Pal, A.; Chakrabarti, M.K. 34 kDa MOMP of Shigella flexneri promotes TLR2 mediated macrophage activation with the engagement of NF-kappaB and p38 MAP kinase signaling. Mol Immunol 2010, 47, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmann, D.; Godoy, P.; Weiss, C.; Gerloff, A.; Singer, M.V.; Dooley, S.; Böcker, U. Interfering with interferon-γ signalling in intestinal epithelial cells: Selective inhibition of apoptosis-maintained secretion of anti-inflammatory interleukin-18 binding protein. Clin Exp Immunol 2011, 163, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrusant-Fernandez, M.; ap Rees, T.; Jimeno, R.; Angelis, N.; Ng, J.C.; Fraternali, F.; Li, V.S.W.; Barral, P. IFN-γ-dependent regulation of intestinal epithelial homeostasis by NKT cells. Cell Reports 2024, 43, 114948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glading, A.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; Wells, A. Cutting to the chase: Calpain proteases in cell motility. Trends Cell Biol 2002, 12, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.; Huttenlocher, A.; Lauffenburger, D.A. Calpain proteases in cell adhesion and motility. Int Rev Cytol 2005, 245, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.J.; Huttenlocher, A. Regulating cell migration: Calpains make the cut. J Cell Sci 2005, 118 Pt 17, 3829–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Prince, A. Ca2+ signaling in airway epithelial cells facilitates leukocyte recruitment and transepithelial migration. J Leukoc Biol 2009, 86, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cario, E.; Gerken, G.; Podolsky, D.K. Toll-Like Receptor 2 Controls Mucosal Inflammation by Regulating Epithelial Barrier Function. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soong, G.; Chun, J.; Parker, D.; Prince, A. Staphylococcus aureus Activation of Caspase 1/Calpain Signaling Mediates Invasion Through Human Keratinocytes. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2012, 205, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, J.; Virtue, A.; Shen, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.-F. An evolving new paradigm: Endothelial cells—conditional innate immune cells. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2013, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einhorn, S.; Eldor, A.; Vlodavsky, I.; Fuks, Z.; Panet, A. Production and characterization of interferon from endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol 1985, 122, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xu, K.; Shao, Y.; Saaoud, F.; Snyder, N.W.; Yang, L.; Yu, J.; Wu, S.; Hu, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, X. Editorial: Endothelial cells as innate immune cells. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1035497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.T.; Fisher, M.J.; Sumbria, R.K. Brain endothelial cells as phagocytes: Mechanisms and implications. Fluids Barriers CNS 2025, 22, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amersfoort, J.; Eelen, G.; Carmeliet, P. Immunomodulation by endothelial cells—Partnering up with the immune system? Nature Reviews Immunology 2022, 22, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Saredy, J.; Yang, W.Y.; Sun, Y.; Lu, Y.; Saaoud, F.; Drummer, C.; Johnson, C.; Xu, K.; Jiang, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, X. Vascular Endothelial Cells and Innate Immunity. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2020, 40, e138–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.M.; Wang, Y.; Youn, J.Y.; Cai, H. Endothelial cell calpain as a critical modulator of angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1863, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Akasu, R.; Miyazaki, A. Calpain proteolytic systems counteract endothelial cell adaptation to inflammatory environments. Inflammation and Regeneration 2020, 40, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youn, J.-Y.; Wang, T.; Cai, H. An Ezrin/Calpain/PI3K/AMPK/eNOSs1179 Signaling Cascade Mediating VEGF-Dependent Endothelial Nitric Oxide Production. Circulation Research 2009, 104, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodnar, R.J.; Yates, C.C.; Wells, A. IP-10 Blocks Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-Induced Endothelial Cell Motility and Tube Formation via Inhibition of Calpain. Circulation Research 2006, 98, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Cui, Z.; Li, Z.; Block, E.R. Calpain-2 regulation of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. The FASEB Journal 2006, 20, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Youn, J.Y.; Cai, H. Protein Phosphotyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) in Calpain-dependent Feedback Regulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR2) in Endothelial Cells: IMPLICATIONS IN VEGF-DEPENDENT ANGIOGENESIS AND DIABETIC WOUND HEALING*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2017, 292, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ma, K.; Kwon, S.H.; Garg, R.; Patta, Y.R.; Fujiwara, T.; Gurtner, G.C. The Abnormal Architecture of Healed Diabetic Ulcers Is the Result of FAK Degradation by Calpain 1. J Invest Dermatol 2017, 137, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Wu, W.; Zheng, D.; Peng, G.; Huang, H.; Shen, Z.; Teng, X. Targeted inhibition of endothelial calpain delays wound healing by reducing inflammation and angiogenesis. Cell Death & Disease 2020, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembe, J.-D.; Garabet, W.; Augustin, M.; Dissemond, J.; Ibing, W.; Schelzig, H.; Stuermer, E.K. Immunomarker profiling in human chronic wound swabs reveals IL-1 beta/IL-1RA and CXCL8/CXCL10 ratios as potential biomarkers for wound healing, infection status and regenerative stage. Journal of Translational Medicine 2025, 23, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.I.; Van Raemdonck, K.; Mohammad, G.; Kangave, D.; Van Damme, J.; Abu El-Asrar, A.M.; Struyf, S. Autocrine CCL2, CXCL4, CXCL9 and CXCL10 signal in retinal endothelial cells and are enhanced in diabetic retinopathy. Experimental Eye Research 2013, 109, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Thai, K.; Kepecs, D.M.; Winer, D.; Gilbert, R.E. Reversing CXCL10 Deficiency Ameliorates Kidney Disease in Diabetic Mice. The American Journal of Pathology 2018, 188, 2763–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potz, B.A.; Sabe, A.A.; Sabe, S.A.; Lawandy, I.J.; Abid, M.R.; Clements, R.T.; Sellke, F.W. Calpain inhibition decreases myocardial fibrosis in chronically ischemic hypercholesterolemic swine. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2022, 163, e11–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Taketomi, Y.; Saito, Y.; Hosono, T.; Lei, X.-F.; Kim-Kaneyama, J.-r.; Arata, S.; Takahashi, H.; Murakami, M.; Miyazaki, A. Calpastatin Counteracts Pathological Angiogenesis by Inhibiting Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 Degradation in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Circulation Research 2015, 116, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariano, R.F.; Gardner, T.W. Retinal angiogenesis in development and disease. Nature 2005, 438, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011, 473, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Patel, J.M.; Block, E.R. Hypoxia-specific upregulation of calpain activity and gene expression in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 1998, 275, L461–L468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aono, Y.; Ariyoshi, H.; Tsuji, Y.; Ueda, A.; Tokunaga, M.; Sakon, M.; Monden, M. Localized Activation of m-Calpain in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells Upon Hypoxia. Thrombosis Research 2001, 102, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, X.-G.; Chen, Q.-W.; Li, X.-S.; Zheng, M.-M.; Ke, D.-Z.; Deng, W.; Li, G.-Q.; Jiang, J.; Wu, Z.-Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Cao, G.-Y. Suppression of NHE1 by small interfering RNA inhibits HIF-1α-induced angiogenesis in vitro via modulation of calpain activity. Microvascular Research 2011, 81, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, M.; Ingueneau, C.; Vindis, C.; Thiers, J.C.; Glock, Y.; Rousseau, H.; Sawa, Y.; Bando, Y.; Mallat, Z.; Salvayre, R.; Nègre-Salvayre, A. Oxygen-regulated protein-150 prevents calcium homeostasis deregulation and apoptosis induced by oxidized LDL in vascular cells. Cell Death & Differentiation 2008, 15, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas, S.; Witztum, J.L. Oxidized phospholipids in cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2024, 21, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindis, C.; Elbaz, M.; Escargueil-Blanc, I.; Augé, N.; Heniquez, A.; Thiers, J.-C.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R. Two Distinct Calcium-Dependent Mitochondrial Pathways Are Involved in Oxidized LDL-Induced Apoptosis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2005, 25, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, I.; Nitulescu, M.; Saido, T.C.; Dias, N.; Pedro, L.M.; e Fernandes, J.F.; Ares, M.P.S.; Pörn-Ares, I. Activation of calpain-1 in human carotid artery atherosclerotic lesions. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2009, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Xue, Q.; Cao, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, F.; Yang, Y.; Hayden, M.R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, K. Toll-Like Receptor 4 Mediated Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein-Induced Foam Cell Formation in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells via Src and Sirt1/3 Pathway. Mediators Inflamm 2021, 2021, 6639252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Taketomi, Y.; Takimoto, M.; Lei, X.-F.; Arita, S.; Kim-Kaneyama, J.-r.; Arata, S.; Ohata, H.; Ota, H.; Murakami, M.; Miyazaki, A. m-Calpain Induction in Vascular Endothelial Cells on Human and Mouse Atheromas and Its Roles in VE-Cadherin Disorganization and Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2011, 124, 2522–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Hiron, T.K.; Chalisey, A.; Malhotra, Y.; Agbaedeng, T.; O’Callaghan, C.A. Ox-LDL induces a non-inflammatory response enriched for coronary artery disease risk in human endothelial cells. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 21877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Taketomi, Y.; Higashi, T.; Ohtaki, H.; Takaki, T.; Ohnishi, K.; Hosonuma, M.; Kono, N.; Akasu, R.; Haraguchi, S.; Kim-Kaneyama, J.-R.; Otsu, K.; Arai, H.; Murakami, M.; Miyazaki, A. Hypercholesterolemic Dysregulation of Calpain in Lymphatic Endothelial Cells Interferes With Regulatory T-Cell Stability and Trafficking. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2023, 43, e66–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gu, W.; Wei, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, T.; Shuai, L.; Zhou, X.; Tang, F. Deficiency of Calpain-1 attenuates atherosclerotic plaque and calcification and improves vasomotor dysfunction in Apolipoprotein E knockout mice through inhibiting inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2025, 749, 151369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ji, J.; Zheng, D.; Su, L.; Peng, T.; Tang, J. Protective role of endothelial calpain knockout in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury via attenuation of the p38-iNOS pathway and NO/ROS production. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2020, 52, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluri, H.; Grimsley, M.; Anasooya Shaji, C.; Varghese, K.P.; Zhang, S.L.; Peddaboina, C.; Robinson, B.; Beeram, M.R.; Huang, J.H.; Tharakan, B. Attenuation of Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown and Hyperpermeability by Calpain Inhibition. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 26958–26969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta-Guardo, H.; Biering, S.B.; Castillo-Rojas, B.; DiBiasio-White, M.J.; Lo, N.T.; Espinosa, D.A.; Warnes, C.M.; Wang, C.; Cao, T.; Glasner, D.R.; Beatty, P.R.; Kuhn, R.J.; Harris, E. Flavivirus NS1-triggered endothelial dysfunction promotes virus dissemination. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, K.; Shen, H.; Wu, H.; Wan, C.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Z. Calpain-2 protein influences chikungunya virus replication and regulates vimentin rearrangement caused by chikungunya virus infection. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackow, E.R.; Gorbunova, E.E.; Gavrilovskaya, I.N. Endothelial cell dysfunction in viral hemorrhage and edema. Front Microbiol 2014, 5, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh Roy, S.; Sadigh, B.; Datan, E.; Lockshin, R.A.; Zakeri, Z. Regulation of cell survival and death during Flavivirus infections. World J Biol Chem 2014, 5, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.M.; Zhang, Q.X.; Murray, A.G. Endothelial Cell Calpain Activity Facilitates Lymphocyte Diapedesis. American Journal of Transplantation 2005, 5, 2640–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, M.D. Mechanism of Diapedesis: Importance of the Transcellular Route. Adv Immunol 2016, 129, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, W.A. Mechanisms of Transendothelial Migration of Leukocytes. Circulation Research 2009, 105, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etwebi, Z.; Landesberg, G.; Preston, K.; Eguchi, S.; Scalia, R. Mechanistic Role of the Calcium-Dependent Protease Calpain in the Endothelial Dysfunction Induced by MPO (Myeloperoxidase). Hypertension 2018, 71, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, A. Mast cells: Emerging sentinel innate immune cells with diverse role in immunity. Mol Immunol 2010, 48, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, A. Neutrophils: Cinderella of innate immune system. Int Immunopharmacol 2010, 10, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Dendritic cells in sepsis: Potential immunoregulatory cells with therapeutic potential. Mol Immunol 2018, 101, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, E.; Park, Y.H.; Kitahara, A.; Yamagata, Y.; Kannagi, R.; Murachi, T. Distribution of calpains and calpastatin in human blood cells. Biochem Int 1988, 16, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Hoffmann, F.W.; Norton, R.L.; Hashimoto, A.C.; Hoffmann, P.R. Selenoprotein K Is a Novel Target of m-Calpain, and Cleavage Is Regulated by Toll-like Receptor-induced Calpastatin in Macrophages*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 34830–34838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Kummarapurugu, A.B.; Zheng, S.; Ghio, A.J.; Deshpande, L.S.; Voynow, J.A. Neutrophil elastase activates macrophage calpain as a mechanism for phagocytic failure. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2025, 328, L93–L104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass, E.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Kierdorf, K.; Schlitzer, A. Tissue-specific macrophages: How they develop and choreograph tissue biology. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayan, V.; Pradhan, P.; Braud, L.; Fuchs, H.R.; Gueler, F.; Motterlini, R.; Foresti, R.; Immenschuh, S. Human and murine macrophages exhibit differential metabolic responses to lipopolysaccharide—A divergent role for glycolysis. Redox Biol 2019, 22, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneemann, M.; Schoedon, G. Species differences in macrophage NO production are important. Nature Immunology 2002, 3, 102–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, F.; Wang, R.; Yi, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Q. Tissue macrophages: Origin, heterogenity, biological functions, diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Zhang, P.X.; Satoh, A.; Caputo, C.; Medzhitov, R.; Shenoy, A.; Egan, M.E.; Krause, D.S. Abnormal trafficking and degradation of TLR4 underlie the elevated inflammatory response in cystic fibrosis. J Immunol 2011, 186, 6990–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, T.P.; Frankenberger, M.; Heimbeck, I.; Burggraf, D.; Wjst, M.; Wright, A.K.; Kerscher, M.; Nährig, S.; Huber, R.M.; Fischer, R.; Ziegler-Heitbrock, L. Decreased expression of HLA-DQ and HLA-DR on cells of the monocytic lineage in cystic fibrosis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014, 92, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexis, N.E.; Muhlebach, M.S.; Peden, D.B.; Noah, T.L. Attenuation of host defense function of lung phagocytes in young cystic fibrosis patients. J Cyst Fibros 2006, 5, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, D.; Bruscia, E.M.; Kopp, B.T. Emerging Concepts in Defective Macrophage Phagocytosis in Cystic Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettucciari, K.; Quotadamo, F.; Noce, R.; Palumbo, C.; Modesti, A.; Rosati, E.; Mannucci, R.; Bartoli, A.; Marconi, P. Group B Streptococcus (GBS) disrupts by calpain activation the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton of macrophages. Cell Microbiol 2011, 13, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettucciari, K.; Fetriconi, I.; Mannucci, R.; Nicoletti, I.; Bartoli, A.; Coaccioli, S.; Marconi, P. Group B Streptococcus induces macrophage apoptosis by calpain activation. J Immunol 2006, 176, 7542–7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Van Vleet, T.; Schnellmann, R.G. The role of calpain in oncotic cell death. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2004, 44, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, O.; Sastalla, I.; Wos-Oxley, M.; Rohde, M.; Medina, E. Streptococcus pyogenes induces oncosis in macrophages through the activation of an inflammatory programmed cell death pathway. Cell Microbiol 2009, 11, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulett, G.C.; Maclean, K.H.; Nekkalapu, S.; Cleveland, J.L.; Adderson, E.E. Mechanisms of group B streptococcal-induced apoptosis of murine macrophages. J Immunol 2005, 175, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Leon-Lopez, Y.S.; Thompson, M.E.; Kean, J.J.; Flaherty, R.A. The PI3K-Akt pathway is a multifaceted regulator of the macrophage response to diverse group B Streptococcus isolates. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1258275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Castejon, G.; Corbett, D.; Goldrick, M.; Roberts, I.S.; Brough, D. Inhibition of Calpain Blocks the Phagosomal Escape of Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewamitta, S.R.; Nomura, T.; Kawamura, I.; Hara, H.; Tsuchiya, K.; Kurenuma, T.; Shen, Y.; Daim, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Qu, H.; Sakai, S.; Xu, Y.; Mitsuyama, M. Listeriolysin O-Dependent Bacterial Entry into the Cytoplasm Is Required for Calpain Activation and Interleukin-1α Secretion in Macrophages Infected with Listeria monocytogenes. Infection and Immunity 2010, 78, 1884–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Wang, J.; Hou, D.; Liu, W.; Xie, C.; Shi, K.; Han, W.; Miao, X.; Chen, J.; Cai, Z.; Yang, H.; Ling, Q.; Yin, K.; Dong, Z.; Huang, Z. Calpain-2 facilitates infection of the intracellular bacteria Listeria monocytogenes and invasion intestinal immune barrier by impairing nitric oxide homeostasis. Journal of Advanced Research 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnardel, J.; Da Silva, C.; Henri, S.; Tamoutounour, S.; Chasson, L.; Montañana-Sanchis, F.; Gorvel, J.-P.; Lelouard, H. Innate and Adaptive Immune Functions of Peyer’s Patch Monocyte-Derived Cells. Cell Reports 2015, 11, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Hugot, J.P.; Barreau, F. Peyer’s Patches: The Immune Sensors of the Intestine. Int J Inflam 2010, 2010, 823710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.J.; Choi, H.H.; Choi, J.A.; Jeong, J.A.; Cho, S.N.; Lee, J.H.; Park, J.B.; Kim, H.J.; Song, C.H. Mycobacterium kansasii-induced death of murine macrophages involves endoplasmic reticulum stress responses mediated by reactive oxygen species generation or calpain activation. Apoptosis 2013, 18, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, E.F.; Dekonenko, A.; Arko-Mensah, J.; Mandell, M.A.; Dupont, N.; Jiang, S.; Delgado-Vargas, M.; Timmins, G.S.; Bhattacharya, D.; Yang, H.; Hutt, J.; Lyons, C.R.; Dobos, K.M.; Deretic, V. Autophagy protects against active tuberculosis by suppressing bacterial burden and inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, E3168–E3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, R.; Berliocchi, L.; Adornetto, A.; Varano, G.P.; Cavaliere, F.; Nucci, C.; Rotiroti, D.; Morrone, L.A.; Bagetta, G.; Corasaniti, M.T. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Beclin-1 and autophagy deregulation following retinal ischemic injury in vivo. Cell Death Dis 2011, 2, e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.; Peñaloza, H.; Wang, Z.; Wickersham, M.; Parker, D.; Patel, P.; Koller, A.; Chen, E.I.; Bueno, S.M.; Uhlemann, A.C.; Prince, A. Acquired resistance to innate immune clearance promotes Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 pulmonary infection. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e89704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.Y.; Kim, D.W.; Karmin, J.A.; Hong, D.; Chang, S.S.; Fujisawa, M.; Takayanagi, H.; Bigliani, L.U.; Blaine, T.A.; Lee, H.J. mu-Calpain regulates receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL)-supported osteoclastogenesis via NF-kappaB activation in RAW 264.7 cells. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 29929–29936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, Y. RANKL-induced M1 macrophages are involved in bone formation. Bone Research 2017, 5, 17019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, E.; Smyth, M.J.; Dougall, W.C.; Teng, M.W.L. Roles of the RANKL–RANK axis in antitumour immunity—implications for therapy. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2018, 15, 676–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigoni, T.S.; Vellozo, N.S.; Cabral-Piccin, M.; Fabiano-Coelho, L.; Lopes, U.G.; Filardy, A.A.; DosReis, G.A.; Lopes, M.F. RANK Ligand Helps Immunity to Leishmania major by Skewing M2-Like Into M1 Macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, D.; Yan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, R.; Li, Z.; Greer, P.A.; Peng, T.; Wang, Q. Myeloid cell-specific deletion of Capns1 prevents macrophage polarization toward the M1 phenotype and reduces interstitial lung disease in the bleomycin model of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2022, 24, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Thomas, A.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Kernan, K.A.; Su, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Takano, J.; Saido, T.C.; Eddy, A.A. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α1 promotes calpain-1 activation and macrophage inflammation in hypercholesterolemic nephropathy. Lab Invest 2011, 91, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, A. Is neuroimmunomodulation a future therapeutic approach for sepsis? International Immunopharmacology 2010, 10, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hone, A.J.; McIntosh, J.M. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Therapeutic targets for novel ligands to treat pain and inflammation. Pharmacological Research 2023, 190, 106715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papke, R.L.; Lindstrom, J.M. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Conventional and unconventional ligands and signaling. Neuropharmacology 2020, 168, 108021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulski, Z.; Hartmann, P.; Jositsch, G.; Zasłona, Z.; Lips, K.S.; Pfeil, U.; Kurzen, H.; Lohmeyer, J.; Clauss, W.G.; Grau, V.; Fronius, M.; Kummer, W. Nicotinic receptors on rat alveolar macrophages dampen ATP-induced increase in cytosolic calcium concentration. Respiratory Research 2010, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauwels, A.; Rogge, E.; Vandendriessche, B.; Shiva, S.; Brouckaert, P. Extracellular ATP drives systemic inflammation, tissue damage and mortality. Cell Death & Disease 2014, 5, e1102–e1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Virgilio, F.; Vultaggio-Poma, V.; Falzoni, S.; Giuliani, A.L. Extracellular ATP: A powerful inflammatory mediator in the central nervous system. Neuropharmacology 2023, 224, 109333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savio, L.E.B. P2X receptors in the balance between inflammation and pathogen control in sepsis. Purinergic Signalling 2022, 18, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välimäki, E.; Cypryk, W.; Virkanen, J.; Nurmi, K.; Turunen, P.M.; Eklund, K.K.; Åkerman, K.E.; Nyman, T.A.; Matikainen, S. Calpain Activity Is Essential for ATP-Driven Unconventional Vesicle-Mediated Protein Secretion and Inflammasome Activation in Human Macrophages. The Journal of Immunology 2016, 197, 3315–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Letavernier, E.; Le Saux, C.J.; Houssaini, A.; Abid, S.; Czibik, G.; Sawaki, D.; Marcos, E.; Dubois-Rande, J.L.; Baud, L.; Adnot, S.; Derumeaux, G.; Gellen, B. Calpastatin overexpression impairs postinfarct scar healing in mice by compromising reparative immune cell recruitment and activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2015, 309, H1883–H1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Stewart IV, J.H. Obesity, bone marrow adiposity, and leukemia: Time to act. Obesity Reviews 2024, 25, e13674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kiran, S.; Kumar, S.; Singh, U.P. Extracellular vesicles in obesity and its associated inflammation. International Reviews of Immunology 2022, 41, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarov, S.; Blériot, C.; Ginhoux, F. Role of adipose tissue macrophages in obesity-related disorders. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2022, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, S.P.; McCann, D.; Desai, M.; Rosenbaum, M.; Leibel, R.L.; Ferrante, A.W. Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 2003, 112, 1796–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Miyazaki, A. Emerging roles of calpain proteolytic systems in macrophage cholesterol handling. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017, 74, 3011–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrum, S.; Sommer, M.; Raulien, N.; Gericke, M.; Massier, L.; Kovacs, P.; Krasselt, M.; Landgraf, K.; Körner, A.; Dietrich, A.; Blüher, M.; Rossol, M.; Wagner, U. Macrophages in obesity are characterised by increased IL-1β response to calcium-sensing receptor signals. International Journal of Obesity 2022, 46, 1883–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Xu, D.; Deng, W.; Yang, W.; Tang, F.; Da, M. Knockout of calpain-1 protects against high-fat diet-induced liver dysfunction in mouse through inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation. Food Sci Nutr 2021, 9, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.A.; Gu, W.; Li, S.; Wei, Y.; Tang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Juvenal, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, T.; Shuai, L.; Wang, Z.; Wu, B.; Zhou, X.; Tang, F. Calpain-1 is required for abnormality of liver function and metabolism in apolipoprotein E knockout mouse evaluated noninvasively by small animal MRI and PET-CT. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2025, 1870, 159616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniappan, L.; Javidan, A.; Jiang, W.; Mohammadmoradi, S.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Katz, W.S.; Balakrishnan, A.; Howatt, D.A.; Subramanian, V. Calpain Inhibition Attenuates Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Fibrosis in Diet-induced Obese Mice. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 14398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, V.; Balakrishnan, A.; Howatt, D.A.; Moorleghen, J.J.; Katz, W.S. Abstract 81: Pharmacological Inhibition of Calpain Attenuates Adipose Tissue Apoptosis, Macrophage Accumulation and Inflammation in Diet-induced Obese Mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2013, 33 (Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanouna, G.; Mesnard, L.; Vandermeersch, S.; Perez, J.; Placier, S.; Haymann, J.-P.; Campagne, F.; Moroch, J.; Bataille, A.; Baud, L.; Letavernier, E. Specific calpain inhibition protects kidney against inflammaging. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokuta, M.A.; Nuzzi, P.A.; Huttenlocher, A. Calpain regulates neutrophil chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 4006–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsube, M.; Kato, T.; Kitagawa, M.; Noma, H.; Fujita, H.; Kitagawa, S. Calpain-mediated regulation of the distinct signaling pathways and cell migration in human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol 2008, 84, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knepper-Nicolai, B.; Savill, J.; Brown, S.B. Constitutive Apoptosis in Human Neutrophils Requires Synergy between Calpains and the Proteasome Downstream of Caspases *. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273, 30530–30536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Gómez, A.; Perretti, M.; Soehnlein, O. Resolution of inflammation: An integrated view. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2013, 5, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.; Gilroy, D.W. Chronic inflammation: A failure of resolution? Int J Exp Pathol 2007, 88, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jundi, B.; Lee, D.-H.; Jeon, H.; Duvall, M.G.; Nijmeh, J.; Abdulnour, R.-E.E.; Pinilla-Vera, M.; Baron, R.M.; Han, J.; Voldman, J.; Levy, B.D. Inflammation resolution circuits are uncoupled in acute sepsis and correlate with clinical severity. JCI Insight 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delano, M.J.; Ward, P.A. The immune system’s role in sepsis progression, resolution, and long-term outcome. Immunol Rev 2016, 274, 330–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, S.; Hallett, M.B. Single cell measurement of calpain activity in neutrophils reveals link to cytosolic Ca2+ elevation and individual phagocytotic events. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2019, 515, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitt, S.; Francis, R.J.; Hallett, M.B. Ca2+ and calpain control membrane expansion during the rapid cell spreading of neutrophils. Journal of Cell Science 2013, 126, 4627–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Zlatar, L.; Muñoz-Becerra, M.; Lochnit, G.; Herrmann, I.; Pfister, F.; Janko, C.; Knopf, J.; Leppkes, M.; Schoen, J.; Muñoz, L.E.; Schett, G.; Herrmann, M.; Schauer, C.; Mahajan, A. Calpain-1 weakens the nuclear envelope and promotes the release of neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Communication and Signaling 2024, 22, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gößwein, S.; Lindemann, A.; Mahajan, A.; Maueröder, C.; Martini, E.; Patankar, J.; Schett, G.; Becker, C.; Wirtz, S.; Naumann-Bartsch, N.; Bianchi, M.E.; Greer, P.A.; Lochnit, G.; Herrmann, M.; Neurath, M.F.; Leppkes, M. Citrullination Licenses Calpain to Decondense Nuclei in Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, O.E.; Borregaard, N. Neutrophil extracellular traps—the dark side of neutrophils. J Clin Invest 2016, 126, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baratchi, S.; Danish, H.; Chheang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, A.; Lai, A.; Khanmohammadi, M.; Quinn, K.M.; Khoshmanesh, K.; Peter, K. Piezo1 expression in neutrophils regulates shear-induced NETosis. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kim, S.J.; Lei, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Tsung, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps in homeostasis and disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiemer, A.J.; Lokuta, M.A.; Surfus, J.C.; Wernimont, S.A.; Huttenlocher, A. Calpain inhibition impairs TNF-alpha-mediated neutrophil adhesion, arrest and oxidative burst. Mol Immunol 2010, 47, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemer, A.J.; Lokuta, M.A.; Surfus, J.C.; Wernimont, S.A.; Huttenlocher, A. Calpain inhibition impairs TNF-α-mediated neutrophil adhesion, arrest and oxidative burst. Molecular Immunology 2010, 47, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, M. Dendritic Cells in Immunity and Tolerance—Do They Display Opposite Functions? Immunity 2003, 19, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Murillo, I.; Adán-Barrientos, I.; Galán, M.; Wculek, S.K.; Sancho, D. Dendritic cells as orchestrators of anticancer immunity and immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2024, 21, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, C.Y.; Belabed, M.; Park, M.D.; Mattiuz, R.; Puleston, D.; Merad, M. Dendritic cell maturation in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2025, 25, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, Y.; Carragher, N.O.; Thrasher, A.J.; Jones, G.E. Inhibition of calpain stabilises podosomes and impairs dendritic cell motility. Journal of Cell Science 2006, 119, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumilina, E.; Huber, S.M.; Lang, F. Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of dendritic cell functions. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2011, 300, C1205–C1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle, Y.; Burns, S.; Thrasher, A.J.; Jones, G.E. The leukocyte podosome. Eur J Cell Biol 2006, 85, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, A.; Frenette, P.S. Leukocyte Podosomes Sense Their Way through the Endothelium. Immunity 2007, 26, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, C.V.; Sage, P.T.; Sciuto, T.E.; de la Fuente, M.A.; Geha, R.S.; Ochs, H.D.; Dvorak, H.F.; Dvorak, A.M.; Springer, T.A. Transcellular Diapedesis Is Initiated by Invasive Podosomes. Immunity 2007, 26, 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zahir, N.; Jiang, Q.; Miliotis, H.; Heyraud, S.; Meng, X.; Dong, B.; Xie, G.; Qiu, F.; Hao, Z.; McCulloch, C.A.; Keystone, E.C.; Peterson, A.C.; Siminovitch, K.A. The autoimmune disease–associated PTPN22 variant promotes calpain-mediated Lyp/Pep degradation associated with lymphocyte and dendritic cell hyperresponsiveness. Nature Genetics 2011, 43, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, T.W. Lyp breakdown and autoimmunity. Nature Genetics 2011, 43, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizaoui, K.; Terrazzino, S.; Cargnin, S.; Lee, K.H.; Gauckler, P.; Li, H.; Shin, J.I.; Kronbichler, A. The role of PTPN22 in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases: A comprehensive review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021, 51, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel-Côté, G.; Gendron, D.; Rola-Pleszczynski, M.; Stankova, J. Regulation of platelet-activating factor-mediated protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B activation by a Janus kinase 2/calpain pathway. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, N.E.; Wilson, H.M. Recent Developments in the Role of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) as a Regulator of Immune Cell Signalling in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braquet, P.; Rola-Pleszcynski, M. Platelet-activating factor and cellular immune responses. Immunology Today 1987, 8, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafforini, D.M.; McIntyre, T.M.; Zimmerman, G.A.; Prescott, S.M. Platelet-activating factor, a pleiotrophic mediator of physiological and pathological processes. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2003, 40, 643–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, R.; Terlizzi, M.; Di Crescenzo, V.G.; Popolo, A.; Pecoraro, M.; Perillo, G.; Galderisi, A.; Pinto, A. Human lung cancer-derived immunosuppressive plasmacytoid dendritic cells release IL-1α in an AIM2 inflammasome-dependent manner. Am J Pathol 2015, 185, 3115–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, S.N.; St. John, A.L. Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens. Nature Reviews Immunology 2010, 10, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plum, T.; Feyerabend, T.B.; Rodewald, H.-R. Beyond classical immunity: Mast cells as signal converters between tissues and neurons. Immunity 2024, 57, 2723–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, C.N.; Hoft, S.G.; DiPaolo, R.J. Mast Cells as Important Regulators in Autoimmunity and Cancer Development. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 752350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dileepan, K.N.; Raveendran, V.V.; Sharma, R.; Abraham, H.; Barua, R.; Singh, V.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, M. Mast cell-mediated immune regulation in health and disease. Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.K.; Nair, A.; Gupta, M. Mast Cells in Neurodegenerative Disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Gou, G.; Wen, M.; Luo, C.; Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Du, Q.; Xu, J.; Xie, R. Mast cells: Key players in digestive system tumors and their interactions with immune cells. Cell Death Discovery 2025, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, F.; Chen, W.; Wu, P.; Wieschhaus, A.J.; Chishti, A.H.; Roche, P.A.; Chen, W.M.; Lin, T.J. Calpain-1 contributes to IgE-mediated mast cell activation. J Immunol 2014, 192, 5130–5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, G.P.; Ahmed, M.E.; Thangavel, R.; Kempuraj, D.; Dubova, I.; Raikwar, S.P.; Zaheer, S.; Iyer, S.S.; Zaheer, A. A role for glia maturation factor dependent activation of mast cells and microglia in MPTP induced dopamine loss and behavioural deficits in mice. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 87, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, S.J.; Smith, P.D.; Jackson-Lewis, V.; Lamba, W.R.; Hayley, S.P.; Grimm, E.; Callaghan, S.M.; Slack, R.S.; Melloni, E.; Przedborski, S.; Robertson, G.S.; Anisman, H.; Merali, Z.; Park, D.S. Inhibition of calpains prevents neuronal and behavioral deficits in an MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci 2003, 23, 4081–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, A.; McCoy, H.M.; Zaman, V.; Shields, D.C.; Banik, N.L.; Haque, A. Calpain activation and progression of inflammatory cycles in Parkinson’s disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2022, 27, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempuraj, D.; Ahmed, M.E.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Thangavel, R.; Raikwar, S.P.; Zaheer, S.A.; Iyer, S.S.; Burton, C.; James, D.; Zaheer, A. Mast Cell Activation, Neuroinflammation, and Tight Junction Protein Derangement in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury. Mediators Inflamm 2020, 2020, 4243953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lan, Z.; Hu, Z. Role and mechanisms of mast cells in brain disorders. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1445867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, E.; van Bergeijk, D.; Oosting, R.S.; Redegeld, F.A. Mast cells in neuroinflammation and brain disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017, 79, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, P.; Befus, A.D. Inhibition of calpain is a component of nitric oxide-induced down-regulation of human mast cell adhesion. J Immunol 2003, 170, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Innate lymphoid cells: New paradigm in immunology of inflammation. Immunology Letters 2014, 157, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Innate lymphoid cell and adaptive immune cell cross-talk: A talk meant not to forget. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2020, 108, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivier, E.; Artis, D.; Colonna, M.; Diefenbach, A.; Di Santo, J.P.; Eberl, G.; Koyasu, S.; Locksley, R.M.; McKenzie, A.N.J.; Mebius, R.E.; Powrie, F.; Spits, H. Innate Lymphoid Cells: 10 Years On. Cell 2018, 174, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. Innate Lymphoid Cells: Immunoregulatory Cells of Mucosal Inflammation. European Journal of Inflammation 2014, 12, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Innate Lymphoid Cells and Adaptive Immune Cells Cross-Talk: A Secret Talk Revealed in Immune Homeostasis and Different Inflammatory Conditions. International Reviews of Immunology 2021, 40, 217–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diefenbach, A.; Colonna, M.; Koyasu, S. Development, Differentiation, and Diversity of Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity 2014, 41, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.V.; Goust, J.M.; Banik, N.L. Differential distribution of calpain in human lymphoid cells. Neurochem Res 1993, 18, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, W.M.; de Bont, H.J.; Mulder, G.J.; Nagelkerke, J.F. The role of calpains in apoptotic changes in isolated hepatocytes after attack by Natural Killer cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2002, 11, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, A.M.; Brahmi, Z. Inhibition of the calpain-mediated proteolysis of protein kinase C enhances lytic activity in human NK cells. Cell Immunol 1991, 138, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kwon, S. Enhanced cytotoxic activity of natural killer cells from increased calcium influx induced by electrical stimulation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, I.; Liesche, C.; van Ooijen, H.; Urlaub, D.; Verron, Q.; Sandström, N.; Fasbender, F.; Claus, M.; Eils, R.; Beaudouin, J.; Önfelt, B.; Watzl, C. NK cells switch from granzyme B to death receptor–mediated cytotoxicity during serial killing. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2019, 216, 2113–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Labrada, A.; Pesini, C.; Santiago, L.; Hidalgo, S.; Calvo-Pérez, A.; Oñate, C.; Andrés-Tovar, A.; Garzón-Tituaña, M.; Uranga-Murillo, I.; Arias, M.A.; Galvez, E.M.; Pardo, J. All About (NK Cell-Mediated) Death in Two Acts and an Unexpected Encore: Initiation, Execution and Activation of Adaptive Immunity. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 896228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Cytotoxic T Cells: Kill, Memorize, and Mask to Maintain Immune Homeostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 8788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.S.; Park, K.; Gola, A.; Baptista, A.P.; Miller, C.H.; Deep, D.; Lou, M.; Boyd, L.F.; Rudensky, A.Y.; Savage, P.A.; Altan-Bonnet, G.; Tsang, J.S.; Germain, R.N. A local regulatory T cell feedback circuit maintains immune homeostasis by pruning self-activated T cells. Cell 2021, 184, 3981–3997.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.J.; Powrie, F. Regulatory T Cells Reinforce Intestinal Homeostasis. Immunity 2009, 31, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Jiao, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchay, S.; Nunez, R.; Bartholomew, A.M.; Chishti, A.H. Calpain I Null Mice Display Lymphoid Hyperplasia. Blood 2004, 104, 1268–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.V.; Goust, J.-M.; Chakrabarti, A.K.; Barbosa, E.; Hogan, E.L.; Banik, N.L. Calpain Expression in Lymphoid Cells: INCREASED mRNA AND PROTEIN LEVELS AFTER CELL ACTIVATION (∗). Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270, 2497–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selliah, N.; Brooks, W.H.; Roszman, T.L. Proteolytic cleavage of α-actinin by calpain in T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody. The Journal of Immunology 1996, 156, 3215–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikosik, A.; Jasiulewicz, A.; Daca, A.; Henc, I.; Frąckowiak, J.E.; Ruckemann-Dziurdzińska, K.; Foerster, J.; Le Page, A.; Bryl, E.; Fulop, T.; Witkowski, J.M. Roles of calpain-calpastatin system (CCS) in human T cell activation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 76479–76495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, M.T.; Brooks, W.H.; Roszman, T.L. Calcium-dependent Signaling Pathways in T Cells: Potential role of calpain, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1b, and p130cas in integrin-mediated signaling events*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 33377–33383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiede, F.; Lu, K.H.; Du, X.; Zeissig, M.N.; Xu, R.; Goh, P.K.; Xirouchaki, C.E.; Hogarth, S.J.; Greatorex, S.; Sek, K.; Daly, R.J.; Beavis, P.A.; Darcy, P.K.; Tonks, N.K.; Tiganis, T. PTP1B Is an Intracellular Checkpoint that Limits T-cell and CAR T-cell Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 752–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, M.T.; Dix, A.R.; Brooks, W.H.; Roszman, T.L. β1 Integrin-Mediated T Cell Adhesion and Cell Spreading Are Regulated by Calpain. Experimental Cell Research 2000, 261, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, D.; Müller, S.; Martinon, F.; Demotz, S.; Iwashima, M.; Valitutti, S. Degradation of ZAP-70 following antigenic stimulation in human T lymphocytes: Role of calpain proteolytic pathway. J Immunol 1999, 163, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damen, H.; Tebid, C.; Viens, M.; Roy, D.C.; Dave, V.P. Negative Regulation of Zap70 by Lck Forms the Mechanistic Basis of Differential Expression in CD4 and CD8 T Cells. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 935367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.S.C.; Raychaudhuri, D.; Paul, B.; Chakrabarty, Y.; Ghosh, A.R.; Rahaman, O.; Talukdar, A.; Ganguly, D. Cutting Edge: Piezo1 Mechanosensors Optimize Human T Cell Activation. The Journal of Immunology 2018, 200, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.S.C.; Mandal, T.; Biswas, P.; Hoque, M.A.; Bandopadhyay, P.; Sinha, B.P.; Sarif, J.; D’Rozario, R.; Sinha, D.K.; Sinha, B.; Ganguly, D. Piezo1 mechanosensing regulates integrin-dependent chemotactic migration in human T cells. In eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd.: 2024.

- Wernimont, S.A.; Simonson, W.T.N.; Greer, P.A.; Seroogy, C.M.; Huttenlocher, A. Calpain 4 Is Not Necessary for LFA-1-Mediated Function in CD4+ T Cells. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ganguly, A.; Mucsi, A.D.; Meng, J.; Yan, J.; Detampel, P.; Munro, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, M.; Hari, A.; Stenner, M.D.; Zheng, W.; Kubes, P.; Xia, T.; Amrein, M.W.; Qi, H.; Shi, Y. Strong adhesion by regulatory T cells induces dendritic cell cytoskeletal polarization and contact-dependent lethargy. J Exp Med 2017, 214, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, B.; Shi, Y.; Qi, H. Class II MHC-independent suppressive adhesion of dendritic cells by regulatory T cells in vivo. J Exp Med 2017, 214, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, W.T.N.; Franco, S.J.; Huttenlocher, A. Talin1 Regulates TCR-Mediated LFA-1 Function1. The Journal of Immunology 2006, 177, 7707–7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.J.; Rodgers, M.A.; Perrin, B.J.; Han, J.; Bennin, D.A.; Critchley, D.R.; Huttenlocher, A. Calpain-mediated proteolysis of talin regulates adhesion dynamics. Nature Cell Biology 2004, 6, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, F.; Tapia-Rojo, R.; Winograd-Katz, S.; Boujemaa-Paterski, R.; Li, W.; Unger, T.; Albeck, S.; Aponte-Santamaria, C.; Garcia-Manyes, S.; Medalia, O.; Geiger, B.; Gräter, F. Allosteric activation of vinculin by talin. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Said, R.; Nguyen-Vigouroux, C.; Henriot, V.; Gebhardt, P.; Pernier, J.; Grosse, R.; Le Clainche, C. Talin and vinculin combine their activities to trigger actin assembly. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikosik, A.; Foerster, J.; Jasiulewicz, A.; Frąckowiak, J.; Colonna-Romano, G.; Bulati, M.; Buffa, S.; Martorana, A.; Caruso, C.; Bryl, E.; Witkowski, J.M. Expression of calpain-calpastatin system (CCS) member proteins in human lymphocytes of young and elderly individuals; pilot baseline data for the CALPACENT project. Immun Ageing 2013, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowski, J.M.; Bryl, E. Paradoxical age-related cell cycle quickening of human CD4(+) lymphocytes: A role for cyclin D1 and calpain. Exp Gerontol 2004, 39, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, J.; Dansou, B.; Hervé, R.; Levi, C.; Tamouza, H.; Vandermeersch, S.; Demey-Thomas, E.; Haymann, J.-P.; Zafrani, L.; Klatzmann, D.; Boissier, M.-C.; Letavernier, E.; Baud, L. Calpains Released by T Lymphocytes Cleave TLR2 To Control IL-17 Expression. The Journal of Immunology 2016, 196, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangié, C.; Zhang, W.; Perez, J.; Dubois, Y.C.; Haymann, J.P.; Baud, L. Extracellular calpains increase tubular epithelial cell mobility. Implications for kidney repair after ischemia. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 26624–26632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, T.; Oppenheim, J.J. Chemerin reveals its chimeric nature. J Exp Med 2008, 205, 2187–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, J.L.; Hart, R.; Russ, A.; Dixon, J.P.; Colledge, W.H.; Doran, J.; Hendrick, A.G.; Carlton, M.B.; Greaves, D.R. Synthetic chemerin-derived peptides suppress inflammation through ChemR23. J Exp Med 2008, 205, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.-Y.; Leung, L.L.K. Proteolytic regulatory mechanism of chemerin bioactivity. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 2009, 41, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Oda, N.; Sato, Y. Cell-associated activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta by calpain. J Cell Physiol 1998, 174, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letavernier, B.; Zafrani, L.; Nassar, D.; Perez, J.; Levi, C.; Bellocq, A.; Mesnard, L.; Sachon, E.; Haymann, J.P.; Aractingi, S.; Faussat, A.M.; Baud, L.; Letavernier, E. Calpains contribute to vascular repair in rapidly progressive form of glomerulonephritis: Potential role of their externalization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012, 32, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikosik, A.; Zaremba, A.; Puchalska, Z.; Daca, A.; Smolenska, Z.; Lopatniuk, P.; Mital, A.; Hellman, A.; Bryl, E.; Witkowski, J.M. Ex vivo measurement of calpain activation in human peripheral blood lymphocytes by detection of immunoreactive products of calpastatin degradation. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2007, 45, 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Mimori, T.; Suganuma, K.; Tanami, Y.; Nojima, T.; Matsumura, M.; Fujii, T.; Yoshizawa, T.; Suzuki, K.; Akizuki, M. Autoantibodies to calpastatin (an endogenous inhibitor for calcium-dependent neutral protease, calpain) in systemic rheumatic diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1995, 92, 7267–7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Després, N.; Talbot, G.; Plouffe, B.; Boire, G.; Ménard, H.A. Detection and expression of a cDNA clone that encodes a polypeptide containing two inhibitory domains of human calpastatin and its recognition by rheumatoid arthritis sera. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 1995, 95, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iguchi-Hashimoto, M.; Usui, T.; Yoshifuji, H.; Shimizu, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Ito, Y.; Murakami, K.; Shiomi, A.; Yukawa, N.; Kawabata, D.; Nojima, T.; Ohmura, K.; Fujii, T.; Mimori, T. Overexpression of a minimal domain of calpastatin suppresses IL-6 production and Th17 development via reduced NF-κB and increased STAT5 signals. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letavernier, E.; Dansou, B.; Lochner, M.; Perez, J.; Bellocq, A.; Lindenmeyer, M.T.; Cohen, C.D.; Haymann, J.P.; Eberl, G.; Baud, L. Critical role of the calpain/calpastatin balance in acute allograft rejection. Eur J Immunol 2011, 41, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.W.; Doonan, B.P.; Tyor, W.R.; Abou-Fayssal, N.; Haque, A.; Banik, N.L. Regulation of Th1/Th17 cytokines and IDO gene expression by inhibition of calpain in PBMCs from MS patients. J Neuroimmunol 2011, 232, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, S.A.; Guyton, M.K.; Haque, A.; Vandenbark, A.; Tyor, W.R.; Ray, S.K.; Banik, N.L. Increased calpain correlates with Th1 cytokine profile in PBMCs from MS patients. J Neuroimmunol 2007, 190, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotta, M.T.; Rossini, S.; Suvieri, C.; Coletti, A.; Orabona, C.; Macchiarulo, A.; Volpi, C.; Grohmann, U. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1): An up-to-date overview of an eclectic immunoregulatory enzyme. Febs j 2022, 289, 6099–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forteza, M.J.; Polyzos, K.A.; Baumgartner, R.; Suur, B.E.; Mussbacher, M.; Johansson, D.K.; Hermansson, A.; Hansson, G.K.; Ketelhuth, D.F.J. Activation of the Regulatory T-Cell/Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase Axis Reduces Vascular Inflammation and Atherosclerosis in Hyperlipidemic Mice. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berditchevski, F.; Fennell, E.; Murray, P.G. Calcium-dependent signalling in B-cell lymphomas. Oncogene 2021, 40, 6321–6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, C.; Leben, R.; Rakhymzhan, A.; Kirchhoff, F.; Nitschke, L.; Radbruch, H.; Niesner, R.A.; Hauser, A.E. Intravital quantification reveals dynamic calcium concentration changes across B cell differentiation stages. eLife 2021, 10, e56020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, A.; Ohtsuki, H.; Kirihata, Y.; Yamagata, Y.; Takano, E.; Kannagi, R.; Murachi, T. Selective localization of calpain I (the low-Ca2+-requiring form of Ca2+-dependent cysteine proteinase) in B-cells of human pancreatic islets. FEBS Letters 1985, 184, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Vela, A.; Serrano, F.; González, M.A.; Abad, J.L.; Bernad, A.; Maki, M.; Martínez-A, C. Transplanted Long-Term Cultured Pre-Bi Cells Expressing Calpastatin Are Resistant to B Cell Receptor–Induced Apoptosis. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2001, 194, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Vela, A.; González de Buitrago, G.; Martínez, A.C. Implication of calpain in caspase activation during B cell clonal deletion. Embo j 1999, 18, 4988–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conacci-Sorrell, M.; Eisenman, R.N. Post-translational control of Myc function during differentiation. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, T.; Park, H.; Tsang, M.; de Alborán, I.M.; Nicks, A.; Wilson, L.; Knoepfler, P.S.; Andrews, S.; Rawlings, D.J.; Eisenman, R.N.; Iritani, B.M. Myc stimulates B lymphocyte differentiation and amplifies calcium signaling. J Cell Biol 2007, 179, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]