1. Introduction

Kamakura is a natural fortress city surrounded by mountains on three sides and the sea on one side, making it a city with abundant nature, which is a characteristic of Kamakura1 [

1].

One of Kamakura’s geographical features is the existence of Yatsu valley, a special feature where a valley landform is formed into a mountainous terrain. This feature cannot be ignored when studying Kamakura. Many temples and shrines have been built near Yatsu valley, and it can be said that Yatsu valley and temples and shrines create Kamakura’s uniqueness.

Prior to this research on Kamakura includes historical research on Kamakura and tourism, geographical research on Kamakura and its landscape, and research on river basins.

First, in the study of Kamakura’s history and tourism, Oshida has continued his research on the evaluation of Kamakura’s value as a tourist destination based on his analysis of the “Kamakura Pictorial Map” and “Kamakura Diary” regarding urban formation, pointing out that the temples and shrines in Kamakura had elements of a tourist destination from the Edo period [

2,

3]. Iwata (2023) not only focused on the facilities related to samurai families as the “samurai capital,” but also expanded the focus to merchants, craftsmen, etc. to clarify the history of the formation of the town of Kamakura [

4].

Second, in a study on the geography and landscape of Kamakura, Takahashi et al. (2005) focused on the landscape composition of the Kenchoji temple precincts and discussed the landscape characteristics of Yatsu valley in the Kamakura culture of temples [

5].

The Yatsu valley topography is an important geographical feature of Kamakura, and Takahashi (2017) reads the history of Kamakura from the perspective of the Yatsu valley and points out that the Yatsu valley is indispensable for the creation of Kamakura’s history [

1].

Fujie et al. (2017) studied changes in the landscape of Yatsu valley due to residential development in Yatsu valley and noted that land in Yatsu valley, which used to be samurai land and temple and shrine land, has been developed and changed [

6].

Yamashita et al. (2005) evaluated the green space preservation plan based on the ratio of green spaces and built-up areas per watershed and conducted a study on the distribution of green spaces per watershed [

7]. Itamura et al. (2024) focused on temples and shrines existing in Watershed and Yatsu valley in the Namerigawa River basin, listed three representative temples, and conducted a study on stormwater runoff in the Namerigawa River basin [

8].

In summary, research on Kamakura’s history and tourism is being conducted. As for studies mentioning temples, shrines, and Buddhist temples and Yatsu valley, which are characteristic features of Kamakura, some materials organize the locations of temples, shrines, and Buddhist temples as flat maps, but there are no studies that grasp the location of temples, shrines, and Buddhist temples together with the topography and organize their characteristics [

2,

3,

4]. In addition, while some studies on Yatsu valley focus on one Yatsu valley and discuss the composition of the landscape, green areas, and rainwater runoff in a limited way, there are no studies on a larger scale that look at the landscape from a bird’s eye view, only organizing names and history [

7,

8]. It is clear from previous studies that river excavation was involved in the creation of the Yatsu valley in Kamakura, and it is obvious that the Namerigawa River, which flows through the center of Kamakura, was a major factor [

1,

4]. To understand the characteristics of the Yatsu valley and to analyze the location of temples and shrines in Kamakura, it is necessary to focus on the Namerigawa River basin.

For all the reasons above, the Namerigawa River watershed was selected as the target area for this study, and the locations of temples and shrines in the watershed were classified according to their characteristics. Specifically, the characteristics of temples, shrines, and Buddhist temples in the watershed will be determined by using GIS and other national land data, as well as by conducting on-site inspections to determine the types of locations in which they are located. In addition, the period and religious sects in which the temples and shrines were built will also be sorted out, and the characteristics of the period in which the temples and shrines were built will be determined. Through the above research, the purpose of this study is to organize the characteristics of temples and shrines by period and sect, and to examine the location characteristics of temples and shrines in the Namerigawa River basin based on the analysis of geology and water environment.

2. Survey Methodology

2.1. Study site

This study focuses on the Namerigawa River watershed, a second-class river flowing through Kamakura City, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, with a total length of 6.3 km and a total watershed area of 10.614㎢8,9). The entire watershed from the headwaters near Asahinatouge in Zyuniso to Yuigahama at the mouth of the river is included within the city of Kamakura [

9].

2.2. Definition of Watershed and Yatsu valley

The city of Kamakura, the subject of this study, is characterized by the fact that the Yatsu valley topography extends into the urban area, and the city was formed in the complex Yatsu valley topography.

In this study, the Yatsu valley was defined as a longitudinal valley in the Valley land parallel to the direction of extension of the mountain range [

10].

Catchment areas were extracted using the hydrological analysis program of the Spatial Analysis tool of Esri’s ArcGIS Pro 3.3 (hereinafter referred to as “GIS”) based on 5 m mesh elevation data (DEM data: Digital Elevation Model) [

11].

Referring to the study by Katagiri et al. (2004) [

12], the catchment area formed from a water network with a catchment area of 0.05 km2 was used as the threshold for Watershed extraction, and by visualizing a water network with a catchment area of the smallest unit, how the water in the Watershed is collected was organized. The water network with the smallest water catchment area is visualized to show how water is collected in the Watershed.

Temples and shrines in Kamakura have a long history, and some of them have been abandoned up to the present day. Many of the abandoned temples have no historical records, and the dates of their construction and abandonment are unknown [

13].

The data used in this study, such as topographic maps, were surveyed after modern times, and there are many places where temples and shrines were originally built but have been developed into residential areas, etc. It is difficult to compare temples and shrines that have been abandoned and their use changed to examine their location characteristics in the same way as temples and shrines that are currently built. It is difficult to compare temples, shrines, and Buddhist temples that have been abandoned and their use changed in the same way as those that are still standing. Therefore, temples, shrines, and Buddhist temples used in this study are those that are still standing and have the functions of temples, shrines, and Buddhist temples.

3. Namerigawa river basin, temples, shrines, and Yatsu valley

3.1. Watershed of Namerigawa River

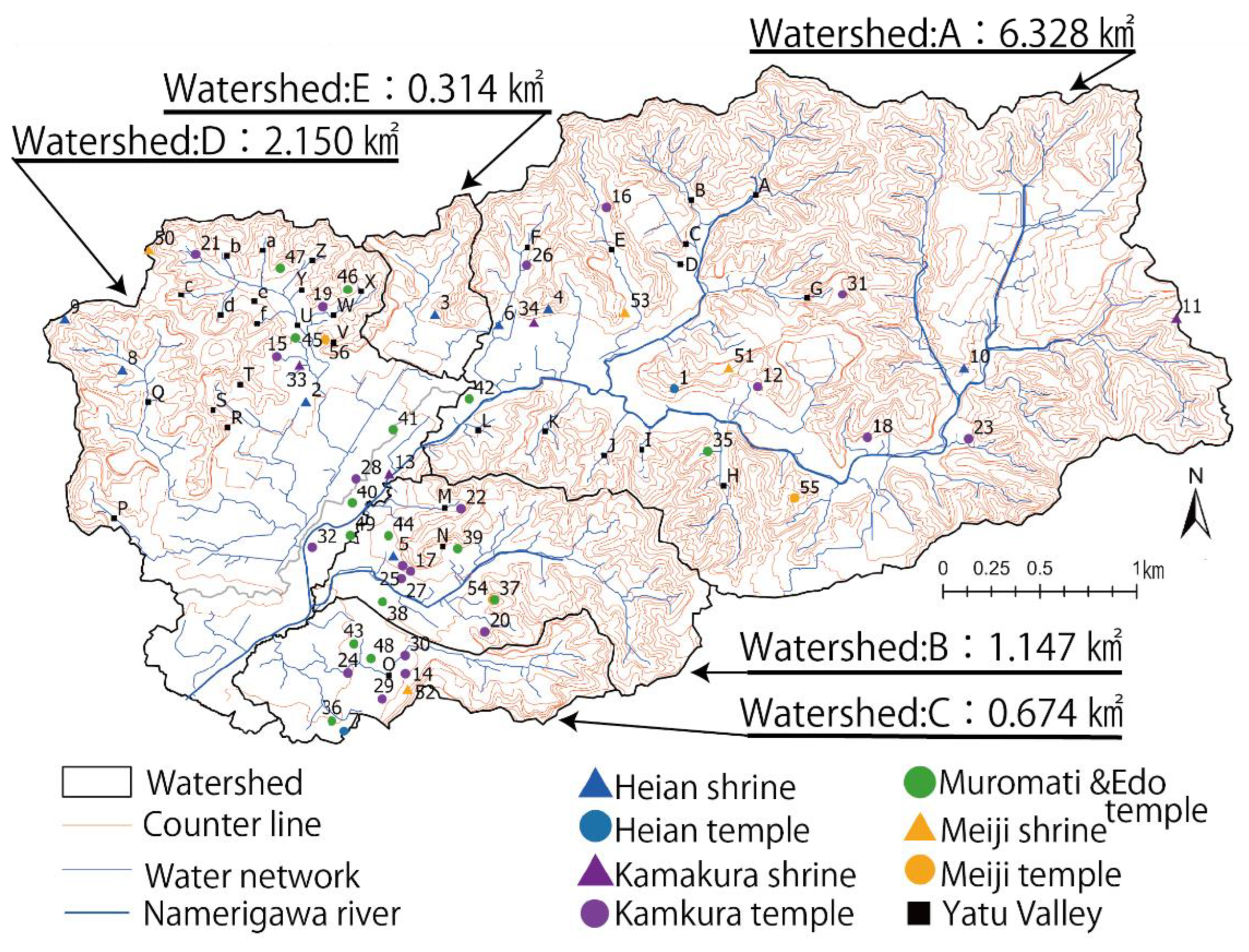

Five Watersheds were extracted from the Namerigawa River watershed using the GIS Hydrologic analysis program.

The area of each Watershed is 6.328km

2(Watershed:A), 1.147km

2(Watershed:B), 0.674km

2(Watershed:C), 2.150km

2(Watershed:D), 0.314km

2(WatershedE), 0.674km

2(Watershed:C), 0.674km

2(Watershed:D), 0.314km

2(Watershed:C), and 0.314km

2(WatershedE), and the entire Namerigawa river area is 10.614km

2 (

Figure 1).

3.2. Temples and shrines in the Namerigawa river basin

There are 56 temples and shrines in the Namerigawa River watershed [

13]. Therefore, the analysis was conducted separately by denomination and date of construction.

The date of construction and religious denomination were sorted out based on information in the “History of Kamakura City: Shrines and Temples” [

13] and “the Kamakura City Tourist Association” [

14].

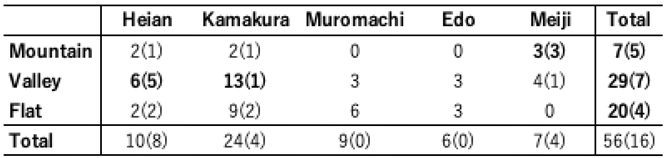

The years of construction were classified into five categories: pre-Heian (including Asuka and Heian periods), Kamakura, Muromachi, Edo, and Meiji periods (including Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods). Ten shrines and temples were erected before the Heian period, 22 during the Kamakura period, 9 during the Muromachi period, 6 during the Edo period, and 7 after the Meiji period (

Table 1).

In Kamakura, there is a mixture of temples and shrines of various religious sects, and it is assumed that each sect has its characteristics in terms of the places where they were built. Therefore, we analyzed the location characteristics of temples and shrines in Kamakura by categorizing the sects along with the period.

Figure 1.

Temples, shrines, and locations as seen from contour lines. Note 1: Numbers and symbols in the figure are linked to

Figure 2 and

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded by period.

Figure 1.

Temples, shrines, and locations as seen from contour lines. Note 1: Numbers and symbols in the figure are linked to

Figure 2 and

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded by period.

For sects, shrines were classified as Shinto. However, since this study is not religious, but rather an analysis of the characteristics of the location of temples, it was decided to classify temples according to their original lineage of teachings rather than by detailed sects, and the following types of sects are used: Type of Jodo-Shu (Ji-Shu, Jodo-Shu), Type of Zen-Shu (Soto-Shu, Rinzai-Shu), Type of Mikkyo (Shingon-Shu, Tendai-Shu). Tendai-Shu), and Type of Nichiren-Shu (Nichiren-Shu and Nichirensho-Shu) [

15].

Table 1.

Construction Period and Location of Temples and Shrines.

Table 1.

Construction Period and Location of Temples and Shrines.

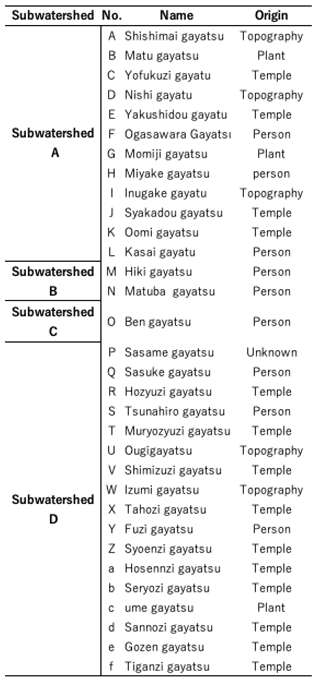

3.3. The existence of the named Yatsu valley in the Namerigawa River basin

The analysis of historical documents such as old maps and documents revealed that there were 32 named Yatsu valleys in the Namerigawa River basin1,[

16]. 14 of the 32 valleys were named after temples and shrines, suggesting that many temples and shrines were built in the Yatsu valley [

1] (

Table 2). It can be inferred that many temples and shrines were built in the Yatsu valley (

Table 2).

The distribution of named Yatsu valleys was 12 in Watershed: A and 17 in Watershed: D. These two watersheds have many named Yatsu valleys. These two watersheds are in mountainous areas far from the sea, and the existence of many Yatsu valley landforms is one of the reasons for this. On the other hand, their distribution overlaps with that of temples and shrines, suggesting that Yatsu valleys with temples and shrines tend to be named after them (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Many Yatsu valleys are named in Watershed: D. The northwest side of Watershed:D is a large Yatsu valley called Ougigayatsu, and there are many branch valleys in this large Yatsu valley. The branch valleys were also given names (

Table 2). In addition, many temples and shrines are still built in Ougigayatsu, and the location of temples and shrines in each Yatsu valley is a characteristic of Ougigayatsu.

Among the named Yatsu valleys, 14 are related to temples, shrines, and temples, and 9 are related to people.

On the other hand, many of the temples and shrines in Yatsu valley are named after temples and shrines, but as Yofukuji temple, the origin of the name of Yofukuji Valley, is now closed, many of the temples and shrines that gave the valley have been closed and are no longer in existence (

Table 2). The result shows that many of the temples and shrines that gave the Yatsu valley are no longer in existence.

Table 2.

Named valleys in the Namekawa River basin and the origin of their names.

Table 2.

Named valleys in the Namekawa River basin and the origin of their names.

Figure 2.

Relationship between small watersheds of temples and shrines in Kamakura, the date of construction, and religious denominations. Note 1: In the table is a reference number for temples and shrines is linked to

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Note 2: The histories in the table were organized by the author based on references [

1,

16].

Figure 2.

Relationship between small watersheds of temples and shrines in Kamakura, the date of construction, and religious denominations. Note 1: In the table is a reference number for temples and shrines is linked to

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Note 2: The histories in the table were organized by the author based on references [

1,

16].

4. Characteristics of each period

4.1. Characteristics of sects in different periods

In the Heian period, Shintoism was particularly prevalent. In the Kamakura period, a trend in schools of Shintoism emerged after 1260, with many Shingon-Shu schools being built in the first half of the period up to 1260, but after 1260, many Type of Jodo-Shu and Type of Nichiren-Shu schools were built. In the Edo period (1603-1867), many Nichiren-Shu were also erected. In the Meiji Period, three Shinto shrines, which had been extremely rare from the Kamakura Period to the Edo Period, were consecutively erected. This may indicate that the influence of the anti-Buddhist movement of the Meiji period extended to Kamakura (

Figure 2).

4.2. Location characteristics by period

Many temples were built in Watershed: C during the Kamakura period (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). As for the distribution, the land where temples and shrines were built spread out around the temples built in the Heian period.

It is characteristic that many temples were built on the south side of the mainstream of the Namerigawa River during the Edo period. Many temples were also erected on the northwest side of Watershed: D. In the Meiji period, the characteristic of temples and shrines development regardless of the watershed was confirmed (

Figure 1).

In the Namerigawa River basin as a whole, most temples tended to be erected along the mainstream of the Namerigawa River in Watershed: B and Watershed: C. In addition, many temples were erected near the water network on the northwest side of Watershed: D. There were also many temples erected near the water network on the northwest side of Watershed: D.

5. Classification of location

5.1. Definition of Kamakura’s geographical features and location

Previous studies have shown that the city of Kamakura is characterized by an intricate Yatsu valley topography. The mainstream of the Namerigawa River is a small river that flows only within the city of Kamakura, but due to the mountainous nature of Kamakura, many tributaries join the river and flow into the sea (

Figure 1). It is assumed that the tributaries of the Namerigawa River cut the mountains and created the Yatsu valley topography. It is also clear from the geological map that the flats were formed by sediment deposition (

Figure 3). This indicates that the Namerigawa River is one of the indispensable factors in the formation of the city of Kamakura.

In this study, the locations of temples and shrines are classified into “Mountain-type shrine and temple”, “Valley-type shrine and temple” and “Flat-type shrine and temple” to understand the location characteristics of temples and shrines in the Namerigawa River basin. The study classifies the locations of temples and shrines into “Mountain-type shrine and temple”, “Valley-type shrine and temple”, and “Flat-type shrine and temple” to understand the location characteristics of temples and shrines in the Namerigawa River watershed.

The site classification method was based on the study by Jasiewicz et al. (2012) [

17] using Geomorphon, a topographic analysis program in the ArcGIS Spatial Analysis tool. Shoulder, Spur, Slope, Hollow, Footslopee, Valley, and Pit) using Geomorphon, a topographic analysis program of the ArcGIS Spatial Analysis Tool, and field survey were conducted to classify the landforms, taking into account the surrounding environment (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

In this study, the locations of temples and shrines were classified into three categories: “Mountain-type shrine and temple,” “Valley-type shrine and temple,” and “Flat-type shrine and temple. Mountain-type shrine and temple” a type of shrine and temple that is located in a mountainous area. Mountain-type shrines and temples” are temples and shrines built on land that includes peaks and mountainsides, and are classified as “Peak, Ridge, or Shoulder” in the Geomorphon.

Valley-type shrine and temple” refers to the Yatsu valley topography characteristic of Kamakura. Valley-type shrine and temple” refers to a place where the land is lower than the surrounding area, not only a sunken lowland but also a relative lowland surrounded by mountains. Pit” in the Geomorphon.

Flat-type shrines and temples are flat, but there are very few flat areas in Kamakura, which are surrounded by mountains and were created by excavation and sedimentation. Therefore, in this research, the areas that are neither “mountain-type shrine and temple” nor “valley-type shrine and temple” are flat, even if the land has a slight slope. The land that has a slight slope, but no obvious unevenness is classified as a “Flat-type shrine and temple” in the Geomorphon. Those classified as “Spur, Slope, or Footslopee” by the Geomorphon were classified as one of the three types after field inspections and consideration of the surrounding environment (

Figure 1,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) since the characteristics of the shrine or temple site cannot be determined by the Geomorphon classification alone. The Geomorphon classification was not sufficient to determine the location characteristics of the temples and shrines.)

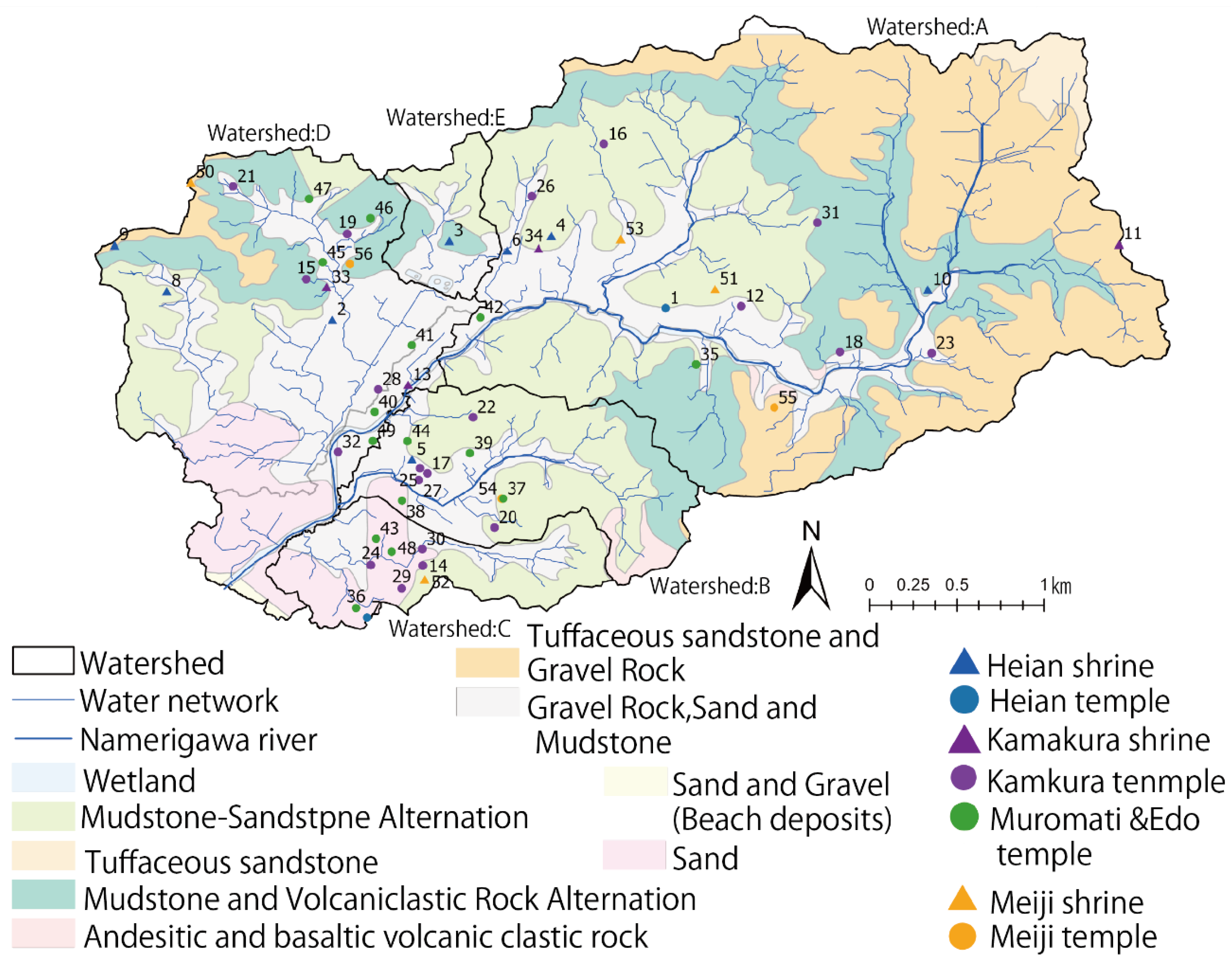

Figure 3.

Classification of location characteristics of temples and shrines. Note 1: The numbers in the figure are linked to

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded by period.

Figure 3.

Classification of location characteristics of temples and shrines. Note 1: The numbers in the figure are linked to

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded by period.

Figure 4.

Location and geology of temples and shrines. Note 1: Numbers in the figure are linked to

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded by period. Note3 The author classified the topographic features and created a figure based on Jarosław Jasiewicz et al. (2021). Note3:

Figure 6 illustrates the location classification for each item.

Figure 4.

Location and geology of temples and shrines. Note 1: Numbers in the figure are linked to

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded by period. Note3 The author classified the topographic features and created a figure based on Jarosław Jasiewicz et al. (2021). Note3:

Figure 6 illustrates the location classification for each item.

Figure 5.

Location Characteristics by Denomination. Note 1: The numbers in the figure are linked to

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded according to denomination. Note 3: The author classified the topographic features and created a figure based on Jarosław Jasiewicz et al. (2021). Note 3:

Figure 6 illustrates the location classification for each item.

Figure 5.

Location Characteristics by Denomination. Note 1: The numbers in the figure are linked to

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded according to denomination. Note 3: The author classified the topographic features and created a figure based on Jarosław Jasiewicz et al. (2021). Note 3:

Figure 6 illustrates the location classification for each item.

Figure 6.

Location classification for each item. Note1:This figure shows the location classification for each item in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Location classification for each item. Note1:This figure shows the location classification for each item in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

5.2. Location of temples and shrines

Seven “Mountain-type shrines and temples” and 29 “Valley-type shrines and temples” were selected as the location of temples and shrines, while 20 “Flat-type shrine and temple” were selected as the location of temples and shrines, with “Valley-type shrines and temples” being the most common, and “Mountain-type shrine and temple” was the least common. Mountain-type shrine and temple” was the least common type, but five out of seven were shrines, indicating that shrines built in the Namerigawa River basin tend to be “mountain-type shrines and temples. The “mountain-type shrine and temple” tended to be more common among the shrines built in the Namerigawa River basin. As for “Valley-type shrines and temples”, 13 out of 29 cases are temples and shrines built in the Kamakura period. It is clear that many “Valley-type shrines and temples” were built in the Kamakura period (

Table 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 4).

Ten temples and shrines were built before the Heian period (794-1185), six of which were “Valley-type shrines and temples. In the Heian period, many “valley-type shrines and temples” were constructed (

Table 1). On the other hand, “flat-type shrines and temples” were more common in temples and shrines built in the Muromachi and Edo periods (

Table 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 4).

In the Meiji period, “Flat-type shrine and temple” was not built, but “Valley-type shrine and temple” and “Mountain-type shrine and temple” were built. However, all three of the “mountain-type shrines and temples” in the Meiji period were shrines, all three were built soon after the Meiji Period.

Shrines Built in Meiji period was newly constructed under the influence of the anti-Buddhist movement, but only the land for the “Mountain-type shrine and temple” could be acquired due to land constraints. It is assumed that the “Mountain-type shrine and temple” was built because only the “Mountain-type shrine and temple” was available due to land availability. This suggests that the location of the site is related to both the period and religious denomination.

5.3. Location characteristics by denomination

In the Namerigawa River basin, the most common sect was the Type of Nichiren-Shu with 18 cases, followed by Shinto with 16 cases (

Table 3). On the other hand, the least number of Type of Zen-Shu was 4 (

Table 3). The analysis of the location characteristics of each religious sect revealed that 29 of the 56 temples and shrines built in the Namerigawa River watershed were “Valley-type shrines and temples,” and that most of them, except the Type of Jodo-Shu, were located in valleys. Unlike the other four sects, the Type of Jodo-Shu tended to be Flat, with 6 out of 10 cases being Flat-type (

Table 3,

Figure 4). The Type of Nichiren-Shu, like the Type of Jodo-Shu, also tended to be Flat, with 9 out of 18 cases. Both of these two sects were founded in the Kamakura period (1185-1333), and it became clear that they were built mostly in the Kamakura period (1185-1333) and the Namerigawa River area, they were built in the flat areas of Watershed: B and Watershed: C (

Table 3,

Figure 4).

Table 3.

Location Characteristics by Denomination.

Table 3.

Location Characteristics by Denomination.

6. Geology and location characteristics of temples and shrines

In this chapter, temples and shrines in the Namerigawa River watershed were analyzed from a geological perspective based on the Geological NAVI [

19] of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology.

The Namerigawa River basin contains eight types of geology (“Mudstone-Sandstone Alternation”, “Tuffaceous sandstone”, “Mudstone and Volcaniclastic Rock Alternation”, “Andesitic and basaltic volcanic clastic rock Alternation”, and “Tuffaceous sandstone”), “Mudstone and Volcaniclastic Rock Alternation”, “Andesitic and basaltic volcanic clastic rock “, “Tuffaceous sandstone and Gravel Rock”, “Gravel Rock, Sand, and Mudstone”, “Sand and Gravel (Beach deposits)”, and “Sand” (

Figure 3) [

19].

Watershed: A is dominated by “Tuffaceous sandstone and Gravel Rock”, and “Mudstone and Volcaniclastic Rock Alternation the Namerigawa river channel is “Gravel Rock, Sand and Mudstone” (

Figure 3). Watershed: B and Watershed: C are mainly “Mudstone-Sandstone Alternation”. Watershed:D is dominated by “Mudstone and Volcaniclastic Rock Alternation”, while Watershed: C and Watershed:D are characterized by a high sand content at the mouth. It is assumed that sand was deposited at the mouth of the Namerigawa River due to the influence of the sea and sand carried by the river’s mining activities.

In terms of the relationship between the location of temples and shrines and geology, most of the temples and shrines in Watershed: A and Watershed:D are located on the geological boundaries (

Figure 3). On the other hand, in Watershed: C and Watershed:D, many temples and shrines are located in “Gravel Rock, Sand, and Mudstone”. Temples and shrines not located on geological boundaries tended to be located near rivers and water networks (

Figure 3).

Next, the location and geological trends of temples and shrines by period were identified. In the temples and shrines before the Heian period and after the Meiji period, there was a tendency for many temples and shrines to be built in locations that were not geological boundaries. These two periods are characterized by a tendency for more shrines when considering the ratio of temples to shrines compared to the three periods of the Kamakura, Muromachi, and Edo periods (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3). Therefore, it can be inferred that shrines within the Namerigawa River watershed have little relationship with geology. On the other hand, how about temples (

Figure 3).

Focusing on temples, it is clear that many of them are located on geological boundaries (

Figure 7). In particular, many of the Type of Mikkyo and Type of Zen-Shu temples are located on the geological boundary (

Figure 7). On the other hand, some temples, such as the Type of Jodo-Shu, are not located on the geological boundary, but most of them are located near the Namerigawa River or the water network (

Figure 7). The geological boundaries tend to have many springs and wells. In addition, springs that emerge between geological features are abundant in Kamakura, and these springs are called “squeezed water,” which is one of the characteristics of Kamakura[

19]. It is clear that temples and shrines built from the Kamakura period to the Edo period tend to be located in areas with easy access to water.

7. Conclusion

The following five points were identified in this study based on historical archives and GIS analysis of the location.

First, Kamakura has a well-developed Yatsu valley topography, and there are many Yatsu valleys named after temples and shrines. Among them, there are many Yatsu valleys with names closely related to temples and shrines, such as “Yofukuji Valley. On the other hand, many of the temples and shrines from which Yatsu valley derives its name, such as Yofukuji temple, are now defunct[

21].

Second, 29 of the 56 sites were “Valley-type shrines and temples,” indicating that many temples and shrines were built in the Yatsu valley topography. In addition, 13 of the 29 “Valley-type shrine and temple” sites were temples and shrines built in the Kamakura period (1185-1333), and 13 of the 29 “Valley-type shrine and temple” sites were temples and shrines built in the Kamakura period (1185-1333). It was revealed that “Valley-type shrines and temples” were particularly numerous among those built in the Kamakura period.

Third, it became clear that temples and shrines erected in the Namerigawa River watershed were predominantly sectarian, depending on the period. Shintoism tended to be particularly prevalent before the Heian period and after the Meiji period. From the Kamakura period to the Edo period, there was a trend in the number of temples and shrines built after 1260, with the Shingon-Shu type being the most common in the first half of the period until 1260, but the Type of Jodo-Shu and Type of Nichiren-Shu being the most common after 1260. It has also become clear that the Type of Nichiren-Shu tended to be erected more frequently in the Edo period.

Figure 7.

Geological characteristics by denomination. Note 1: The numbers in the figure are linked to

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded according to denomination.

Figure 7.

Geological characteristics by denomination. Note 1: The numbers in the figure are linked to

Table 2. Note 2: The points in the figure are color-coded according to denomination.

Fourth, in terms of the relationship between location and watershed, many temples tended to be built in the vicinity of Watershed: B and Watershed: C along the mainstream of the Namerigawa River. Temples and shrines tended to be densely located in Watershed: B, Watershed: C, and Watershed:D, while those in Watershed: A tended to be scattered. Watershed: A tends to be more dispersed.

Fifth, many of the temples and shrines built between the Kamakura and Edo periods in the Namerigawa River basin are located at geological boundaries or water networks, and many of them are located in areas where water is easily accessible.

This study used GIS and other national land survey data, as well as field surveys to identify the location of temples and shrines in the Namerigawa River basin and analyzed them from the viewpoint of the period in which they were built and the religious sect that they belong to.

Previous studies on Kamakura’s temples and shrines have mainly focused on archaeological research using historical documents and excavations. The location characteristics of temples and shrines in the Namerigawa River watershed presented in this study are very important for future historical and geographical studies.

This study examined the location characteristics of temples and shrines in the Namerigawa River basin by focusing on the water network, topography, and geology. To conduct a detailed analysis of the location characteristics of temples and shrines in Kamakura, we believe that similar research should be conducted in other river basins within Kamakura. Comparing and examining these findings will lead to new insights.

References

- Shinichiro Takahashi (2017). History of Kamakura: Recommendations for a Yatsu valley tour, Koshi Shoin, PP273.

- Oshida, K. Study on the Succession Status of Ancient Capital Tourism in Modern Kamakura. Landscape Research 2013, 76, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kako Oshida (2014). Research on the Inheritance of the Value of Tourism Resources in “Illustrations of Kamakura” after the Early Modern Period, 14th Academic Research Grant (2014)Academic Research Grant (Results). Available online: https://www.kokudo.or.jp/grant/pdf/h26/oshida.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Iwata, A. Development of “town” and transformation of urban space in Kamakura in the Middle Modern Period. Architectural History 2023, 81, 2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, M.; Ishikawa, M. A study on religious Yatsu valley landscape structure in the ancient capital Kamakura as seen in Kenchoji Temple. Landscape Studies 2005, 68, 439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Fujie, N.; Manabe, R.; Murayama, A. Transition of Kamakura Yatsu valley residential development in recent years and the actual condition of change in spatial composition. Urban Planning Report 2019, 18, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, E.; Katagiri, Y.; Ishikawa, M. Study on analysis of green conservation areas using Watershed as a unit. 2005, 40, 865–870.

- Toma Itamura, Tkanori Fukuoka (2023). Fundamental Study on Land Use and Rainwater Runoff Control Functions in the Namerigawa River Watershed, Kamakura, Japan, Tokyo University of Agriculture Agricultural Journal, Vol. 68, No. 3, 73-83. [https://nodai.repo.nii.ac. 2000.

- Kamakura City Green Basic Plan. Available online: https://www.city.kamakura.kanagawa.jp/midori/miki.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Akira Matsumura(2019). Daijirin, 4th ed. Sanseido, p1276, p2755.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Available online: https://www.gsi.go.jp/kiban/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Katagiri, Y.; Yamashita, E.; Ishikawa, M. A study on the creation of Watershed database based on common data and a method for evaluating green space environment. Landscape Research 2004, 67, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamakura City (1972). Kamakura City History, Shrines and Temples, Yoshikawa Kobunkan, PP472.

- Kamakura City Tourism Association, Shrines and Temples. Available online: https://www.trip-kamakura.com/life/13/4/24/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- The author organized the sects by lineage concerning Iwata (2023)[4].

- Kamakura City Central Library Modern Archives & CPC no Kai (2008): Kamakura Yatsu valley records (In the collection of Kamakura City Central Library) (This document is not tobe taken out of the building and is for viewing in the museum only.

- Jasiewicz, J.; Stepinski, T.F. Geomorphons—a pattern recognition approach to classification and mapping of landforms. Geomorphology 2012, 182, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamakura City Tourism Association Web site, History and Culture. Available online: https://education.trip-kamakura.com/%e7%a4%be%e4%bc%9a%ef%bc%88%e6%ad%b4%e5%8f%b2%e3%83%bb%e6%96%87%e5%8c%96%ef%bc%89/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Geological Survey of Japan, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Geological Chart System Geological NAVI. Available online: https://gbank.gsj.jp/geonavi/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Kamakura City website, Natural Environment Survey Results—Kamakura City. Available online: https://www.city.kamakura.kanagawa.jp/midori/documents/23josyou.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Yofukuji temple was built in 1194 but was destroyed by fire in 1405.

- Kamakura City Home Page: Historic Site of Eifukuji Temple. Available online: https://www.city.kamakura.kanagawa.jp/treasury/yohukuji_cg.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).