1. Introduction

Understanding flowering phenology, floral visitation, and breeding systems is fundamental to conserving endangered plants, particularly those dependent on pollinators for reproduction. Phenological traits such as the timing, duration, and synchrony of flowering strongly influence reproductive success by affecting pollinator visitation and conspecific pollen transfer [

1,

2]. These traits are often shaped by local conditions and may differ between natural and restored populations, especially in species with small or fragmented ranges [

3]. Created populations may exhibit altered flowering schedules, reduced synchrony, or lower floral output due to demographic immaturity, altered microclimates, or genetic bottlenecks [

4,

5]. Such deviations may reduce pollination success, particularly in obligately outcrossing species, where flowering synchrony is critical for genetic diversity and population viability [

6]. Restoration sites may also differ in pollinator abundance, visitation rates, or network structure, further influencing reproductive outcomes [

7,

8]. Comparative studies of natural versus created populations are therefore essential for evaluating conservation success.

Hibiscus dasycalyx (Neches River rose-mallow) is a federally threatened, state-endangered perennial endemic to eastern Texas, restricted to seasonally inundated riparian habitats [

9]. The species has declined due to habitat loss, hydrological alteration, invasive species, and fragmentation [

10,

11]. Hybridization with congeners such as

H. laevis and

H. moscheutos poses an additional genetic threat [

12]. Evidence from hand-pollination, allozyme, and phylogenomic studies indicates that

H. dasycalyx and

H. laevis are closely related and readily hybridize, whereas

H. moscheutos is more divergent and hybridizes mainly under artificial conditions [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Thus,

H. laevis represents the greater risk to genetic integrity in sympatric settings.

Shared pollinators may further facilitate hybridization. The hibiscus bee

Ptilothrix bombiformis is an oligolectic specialist on Malvaceae and a highly effective pollinator of

Hibiscus species [

18]. Its fidelity to

Hibiscus and visitation across

H. dasycalyx,

H. laevis, and

H. moscheutos make it a likely vector for interspecific pollen transfer [9-10,12]. While this specialization promotes conspecific pollination, it also increases the risk of hybridization when congeners co-flower. The goal of this study is to compare flowering phenology, synchrony, and floral visitor composition between a natural and an outplanted population of

H. dasycalyx, and to evaluate its breeding system through controlled pollination experiments. Results from studies of hybridization interactions will be presented separately in a future paper. These analyses assess how altered flowering and pollinator limitation may influence reproductive success and conservation outcomes for this threatened species.

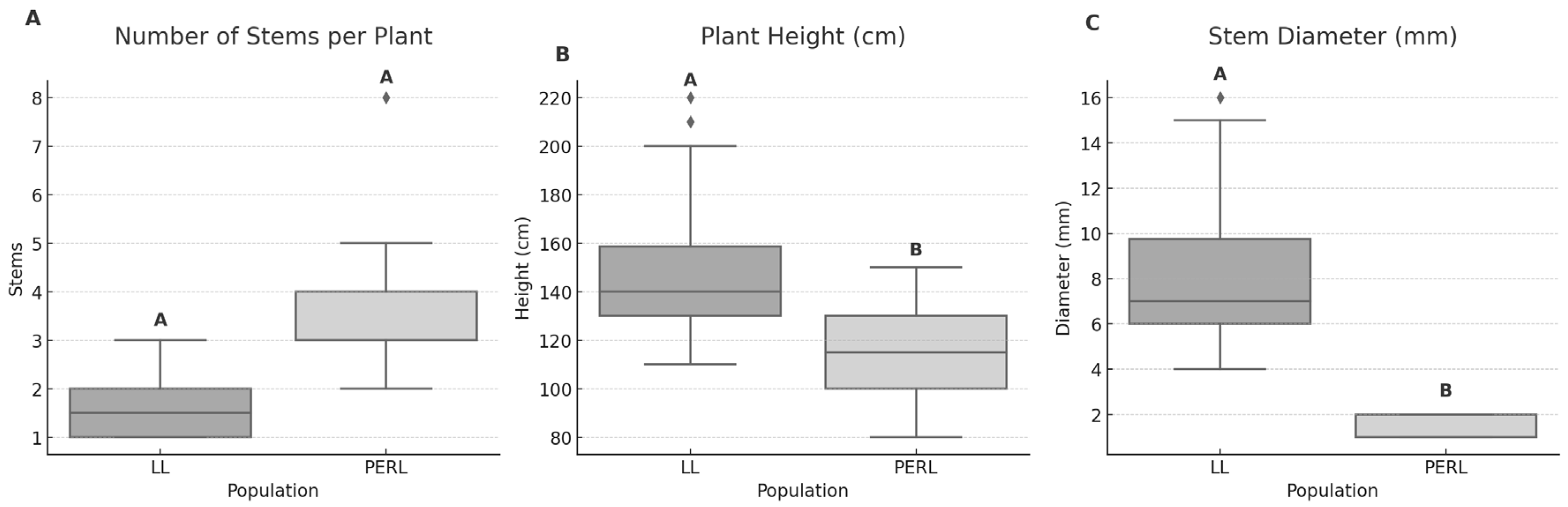

Figure 1.

Comparison of plant size traits between the natural population (LL) and experimental population (PERL) of Hibiscus dasycalyx. (A) Number of stems per plant, (B) plant height, and (C) stem diameter. Boxplots show medians, interquartile ranges, and individual data points. Different letters above boxes indicate significant differences between populations based on Tukey HSD tests (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Comparison of plant size traits between the natural population (LL) and experimental population (PERL) of Hibiscus dasycalyx. (A) Number of stems per plant, (B) plant height, and (C) stem diameter. Boxplots show medians, interquartile ranges, and individual data points. Different letters above boxes indicate significant differences between populations based on Tukey HSD tests (p < 0.05).

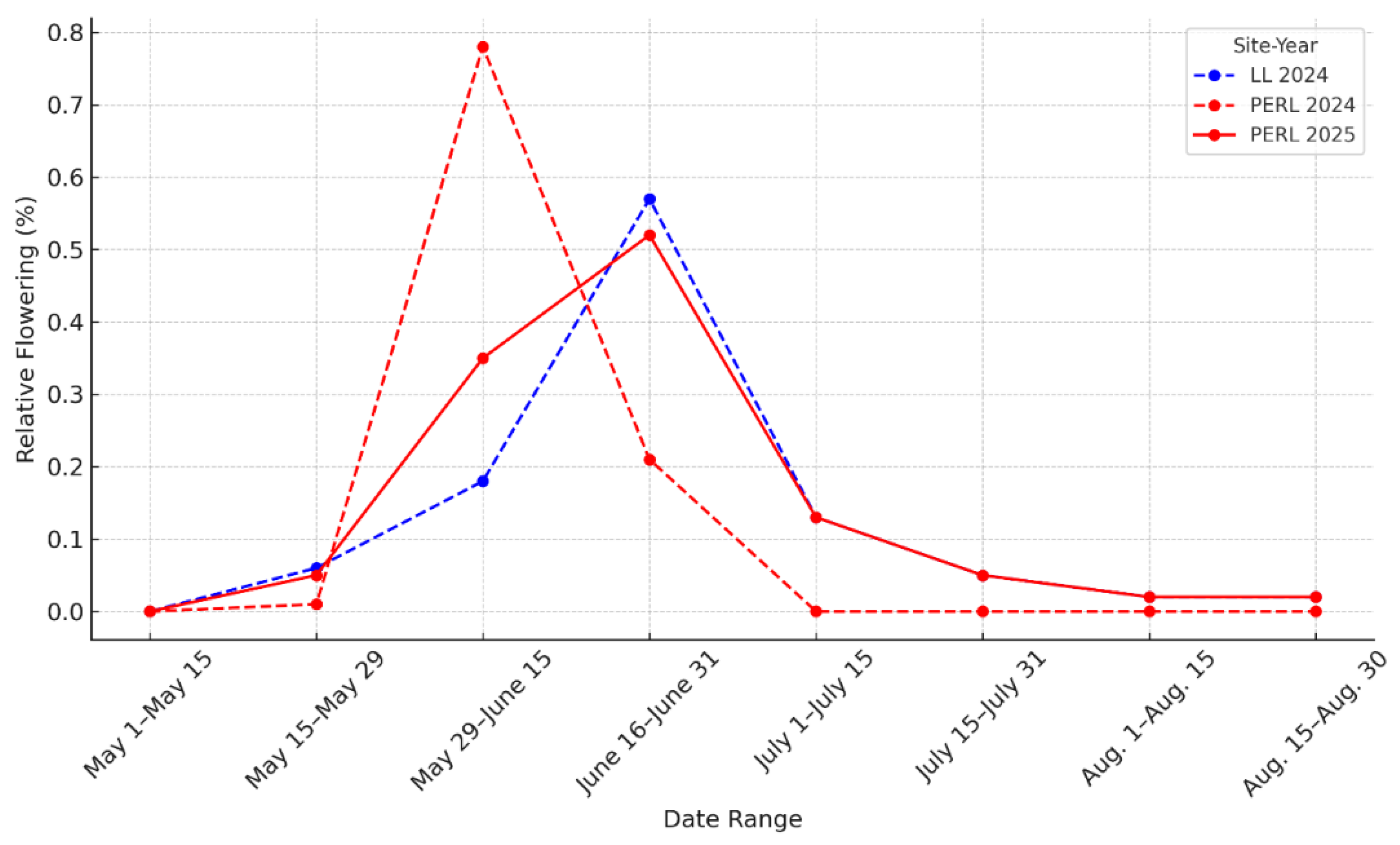

Figure 2.

Relative flowering intensity of Hibiscus dasycalyx at LL (2024) and PERL (2024, 2025). Flowering is expressed as the proportion of total flowers produced in one-week bins beginning 15 May. LL 2024 (blue, solid line) showed a broad distribution of flowering, PERL 2024 (red, dashed line) had a sharp early peak, and PERL 2025 (red, solid line) displayed an intermediate, extended pattern.

Figure 2.

Relative flowering intensity of Hibiscus dasycalyx at LL (2024) and PERL (2024, 2025). Flowering is expressed as the proportion of total flowers produced in one-week bins beginning 15 May. LL 2024 (blue, solid line) showed a broad distribution of flowering, PERL 2024 (red, dashed line) had a sharp early peak, and PERL 2025 (red, solid line) displayed an intermediate, extended pattern.

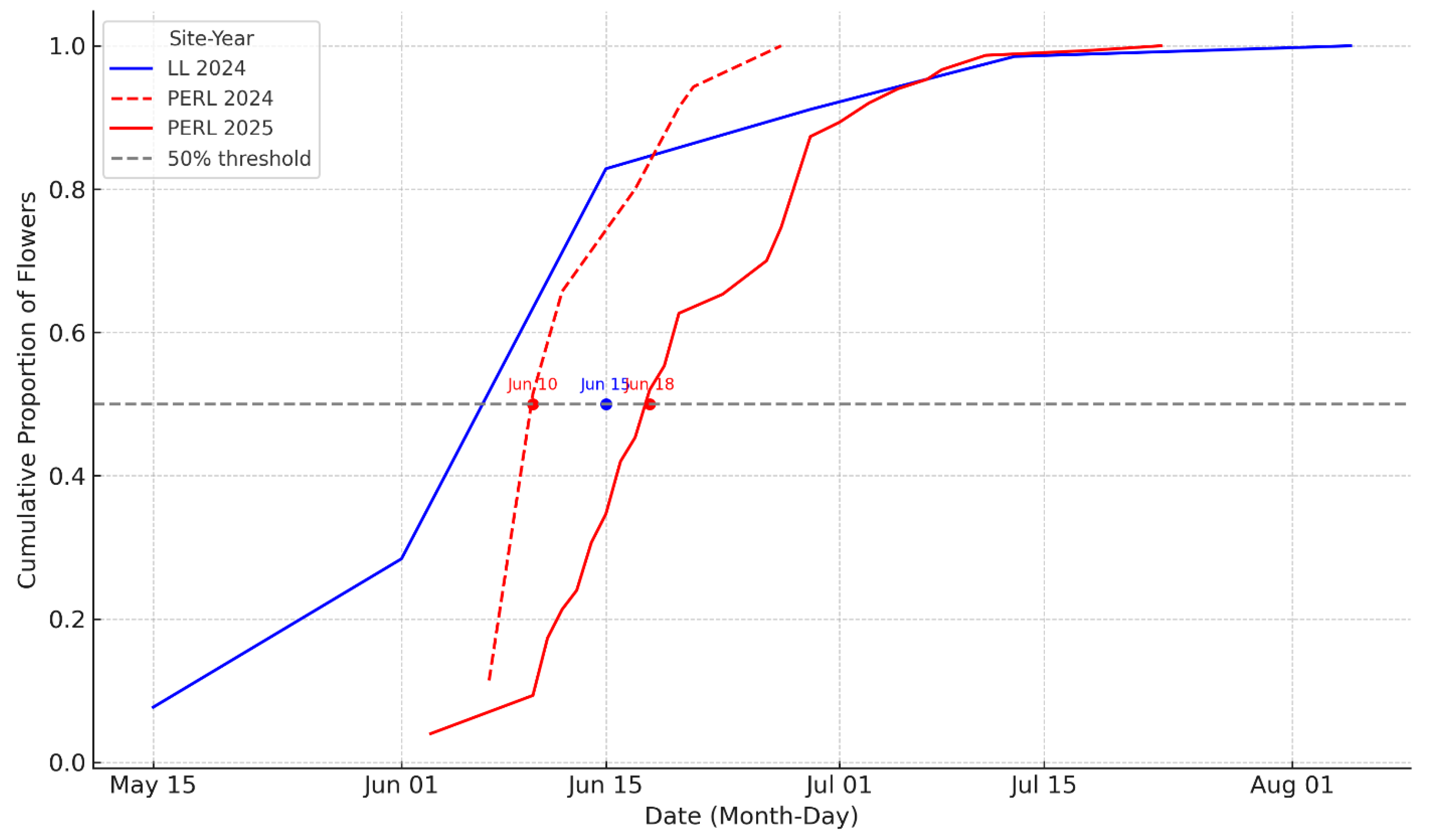

Figure 3.

Cumulative proportion of flowering of Hibiscus dasycalyx at LL (2024) and PERL (2024, 2025). Cumulative flowering curves for Hibiscus dasycalyx across three site-years (LL 2024, PERL 2024, PERL 2025), showing the proportion of flowers produced from May 15 to August 1. The 50% flowering threshold (grey dashed line) was reached on June 10 (PERL 2024), June 13 (LL 2024), and June 18 (PERL 2025). These patterns reflect temporal variation in phenology across sites and years, with implications for pollinator interactions, seed production, and conservation planning.

Figure 3.

Cumulative proportion of flowering of Hibiscus dasycalyx at LL (2024) and PERL (2024, 2025). Cumulative flowering curves for Hibiscus dasycalyx across three site-years (LL 2024, PERL 2024, PERL 2025), showing the proportion of flowers produced from May 15 to August 1. The 50% flowering threshold (grey dashed line) was reached on June 10 (PERL 2024), June 13 (LL 2024), and June 18 (PERL 2025). These patterns reflect temporal variation in phenology across sites and years, with implications for pollinator interactions, seed production, and conservation planning.

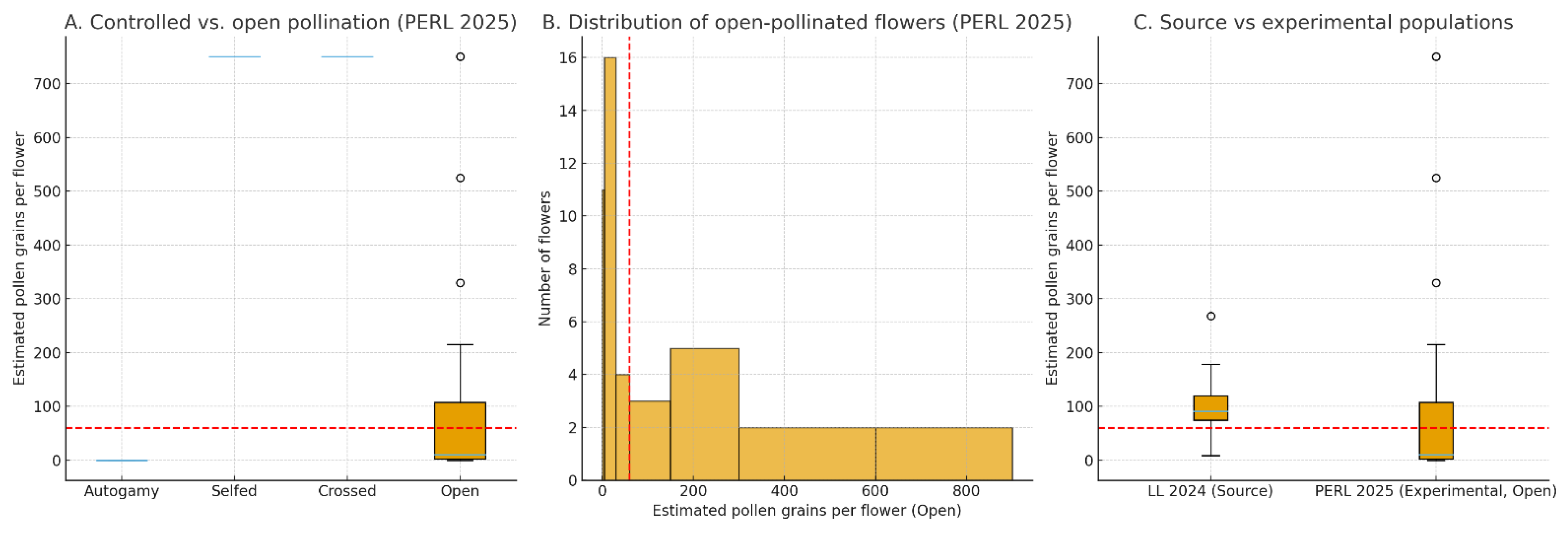

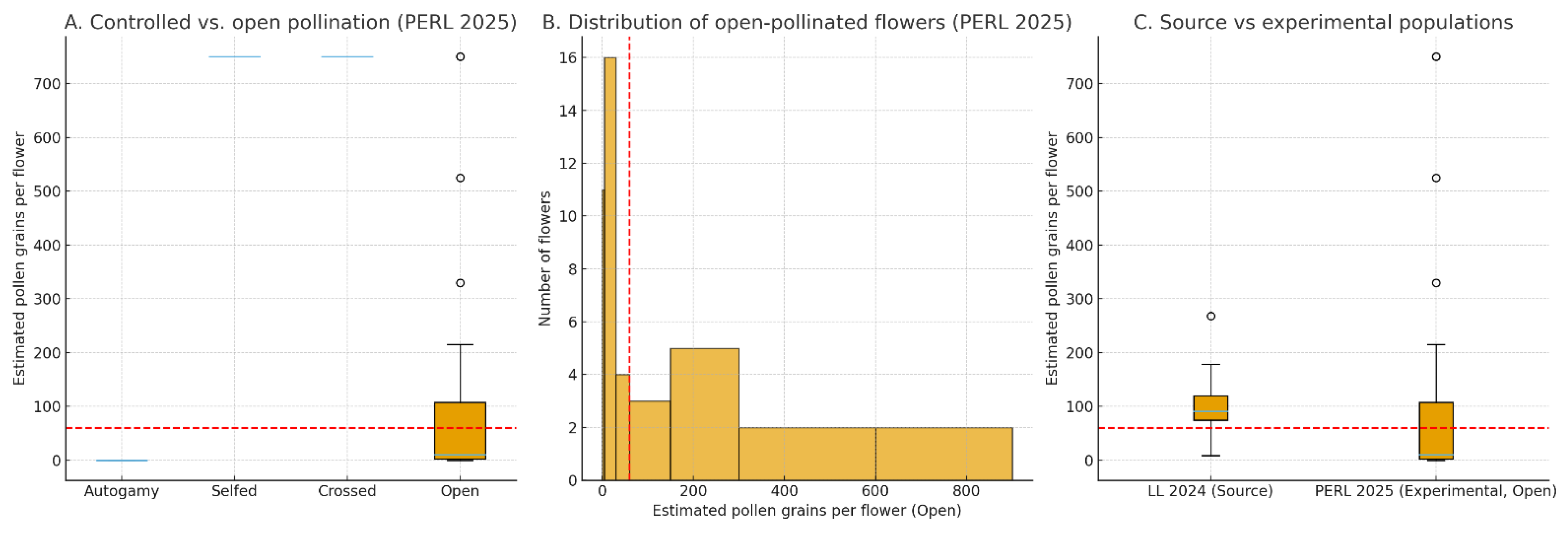

Figure 8.

Stigma pollen deposition in Hibiscus dasycalyx under controlled and natural pollination treatments. (A) Boxplots of estimated pollen grains per flower in the experimental PERL population (2025) for autogamy, selfed, crossed, and open-pollinated treatments. Hand self- and cross-pollinations saturated stigmas with >500 grains, while autogamy flowers received no pollen; open-pollinated flowers showed highly variable deposition. The red dashed line indicates ~60 grains, the approximate threshold required to fertilize ~60 ovules per fruit. (B) Histogram of estimated pollen grains in open-pollinated flowers at PERL, illustrating that most flowers received <30 grains, with only a minority surpassing the 60-grain threshold. (C) Boxplot comparison of total stigma pollen grains per flower in open-pollinated flowers at the experimental PERL population (2025, 6 of 7 plants flowering) versus the natural LL source population (2024, ~200 plants, >30 flowering). Flowers in the dense source population received significantly greater pollen deposition (median = 91 grains, 80% ≥ 60 grains) compared to the sparse experimental population (median = 10 grains, 28% ≥ 60 grains; Mann–Whitney U = 314.0, p = 0.024).

Figure 8.

Stigma pollen deposition in Hibiscus dasycalyx under controlled and natural pollination treatments. (A) Boxplots of estimated pollen grains per flower in the experimental PERL population (2025) for autogamy, selfed, crossed, and open-pollinated treatments. Hand self- and cross-pollinations saturated stigmas with >500 grains, while autogamy flowers received no pollen; open-pollinated flowers showed highly variable deposition. The red dashed line indicates ~60 grains, the approximate threshold required to fertilize ~60 ovules per fruit. (B) Histogram of estimated pollen grains in open-pollinated flowers at PERL, illustrating that most flowers received <30 grains, with only a minority surpassing the 60-grain threshold. (C) Boxplot comparison of total stigma pollen grains per flower in open-pollinated flowers at the experimental PERL population (2025, 6 of 7 plants flowering) versus the natural LL source population (2024, ~200 plants, >30 flowering). Flowers in the dense source population received significantly greater pollen deposition (median = 91 grains, 80% ≥ 60 grains) compared to the sparse experimental population (median = 10 grains, 28% ≥ 60 grains; Mann–Whitney U = 314.0, p = 0.024).

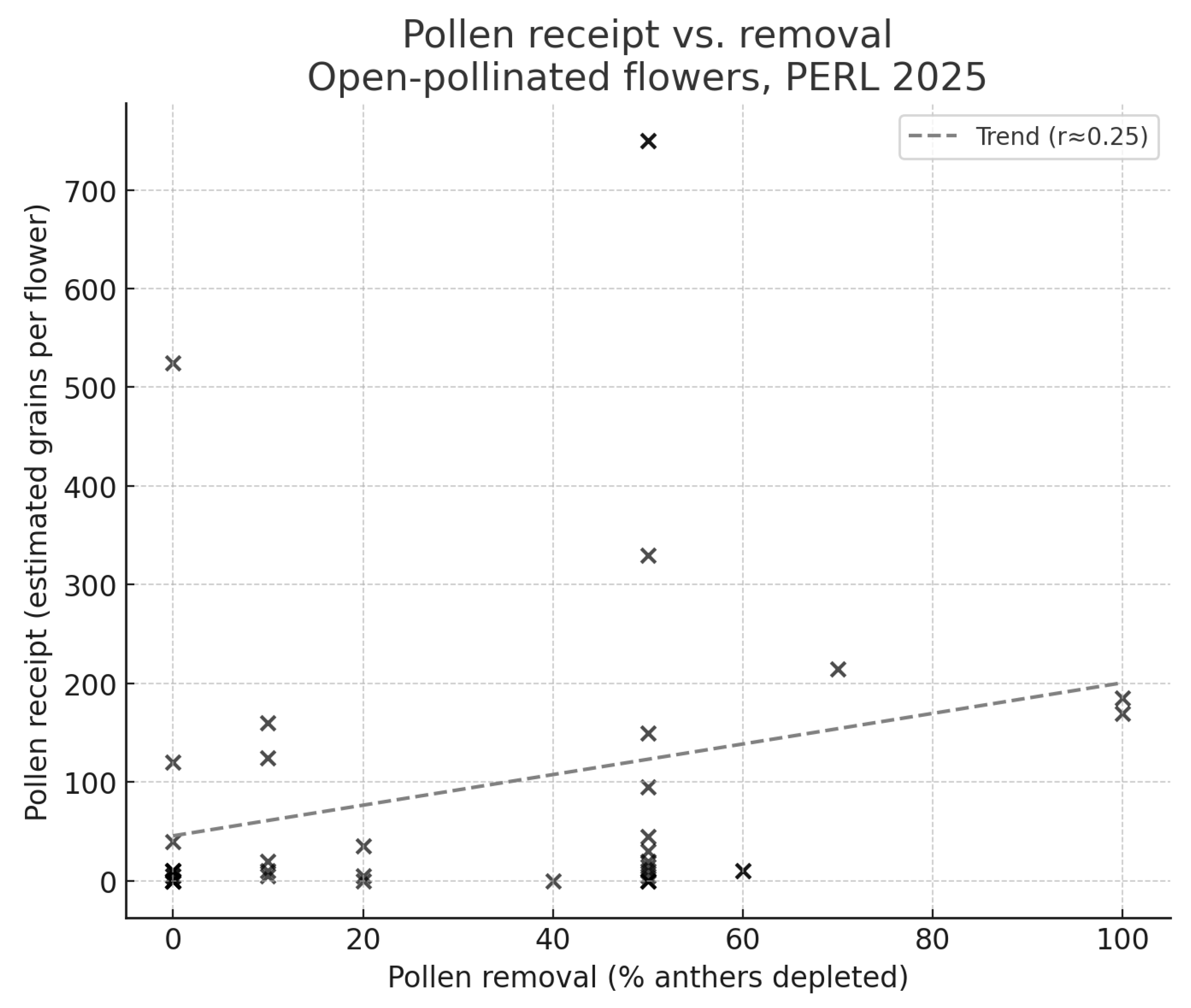

Figure 9.

Relationship between pollen removal and pollen receipt in open-pollinated flowers of Hibiscus dasycalyx at the PERL experimental population in 2025. Pollen removal is expressed as the percentage of anthers depleted (1 = full, 2 = sparse, 3 = empty, converted to 0, 50, and 100% respectively), while pollen receipt is estimated from stigma lobe scores (0–4) converted to grain count midpoints (0, 5, 30, 75, 150) and summed across five lobes. Each point represents a single flower (n = 43). The dashed line indicates the fitted linear trend (r ≈ 0.25), showing a weak positive association between pollen removal and stigma deposition. Despite pollen remaining abundant in many anthers, stigmatic pollen receipt was frequently low, indicating that pollinator limitation rather than pollen supply constrained reproduction in this experimental stand.

Figure 9.

Relationship between pollen removal and pollen receipt in open-pollinated flowers of Hibiscus dasycalyx at the PERL experimental population in 2025. Pollen removal is expressed as the percentage of anthers depleted (1 = full, 2 = sparse, 3 = empty, converted to 0, 50, and 100% respectively), while pollen receipt is estimated from stigma lobe scores (0–4) converted to grain count midpoints (0, 5, 30, 75, 150) and summed across five lobes. Each point represents a single flower (n = 43). The dashed line indicates the fitted linear trend (r ≈ 0.25), showing a weak positive association between pollen removal and stigma deposition. Despite pollen remaining abundant in many anthers, stigmatic pollen receipt was frequently low, indicating that pollinator limitation rather than pollen supply constrained reproduction in this experimental stand.

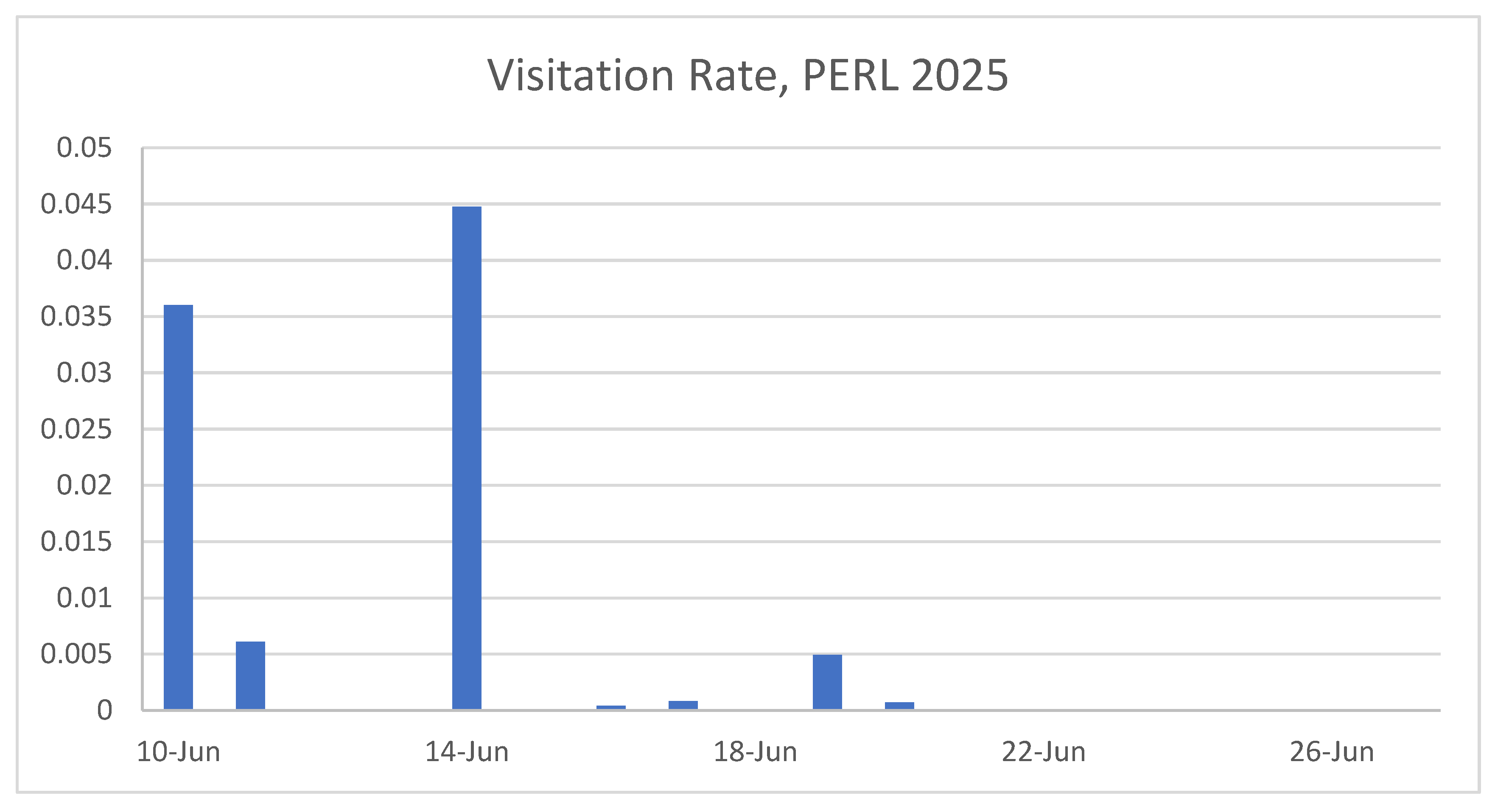

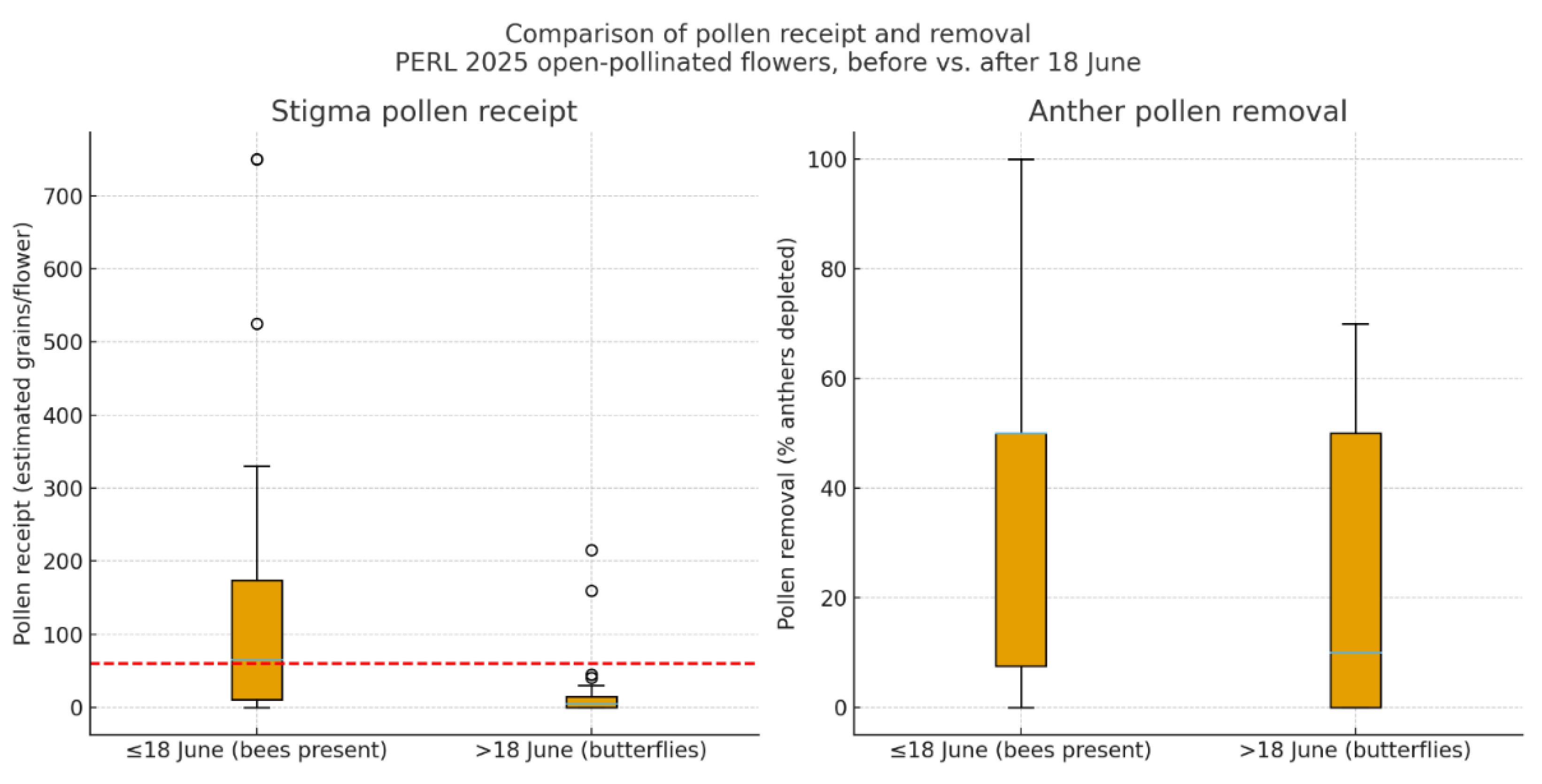

Figure 10.

Pollen receipt and removal in open-pollinated flowers of Hibiscus dasycalyx at the PERL experimental population in 2025, before and after the disappearance of specialist pollinators (Ptilothrix bombiformis). (Left) Stigma pollen receipt (estimated grains per flower) was significantly higher when Ptilothrix bees were present (≤18 June; median = 65 grains) than after they disappeared (>18 June; median = 5 grains; Mann–Whitney U = 339.0, p = 0.007). The red dashed line indicates the approximate ~60-grain threshold required to fertilize all ovules. (Right) Anther pollen removal (% of anthers depleted) tended to be greater when Ptilothrix were present (median = 50%) than after they disappeared (median = 10%), although this difference was not statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U = 286.5, p = 0.155). These results indicate that Ptilothrix bees were the primary effective pollinators, while butterflies and non-Hibiscus bees contributed little to pollen transfer.

Figure 10.

Pollen receipt and removal in open-pollinated flowers of Hibiscus dasycalyx at the PERL experimental population in 2025, before and after the disappearance of specialist pollinators (Ptilothrix bombiformis). (Left) Stigma pollen receipt (estimated grains per flower) was significantly higher when Ptilothrix bees were present (≤18 June; median = 65 grains) than after they disappeared (>18 June; median = 5 grains; Mann–Whitney U = 339.0, p = 0.007). The red dashed line indicates the approximate ~60-grain threshold required to fertilize all ovules. (Right) Anther pollen removal (% of anthers depleted) tended to be greater when Ptilothrix were present (median = 50%) than after they disappeared (median = 10%), although this difference was not statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U = 286.5, p = 0.155). These results indicate that Ptilothrix bees were the primary effective pollinators, while butterflies and non-Hibiscus bees contributed little to pollen transfer.

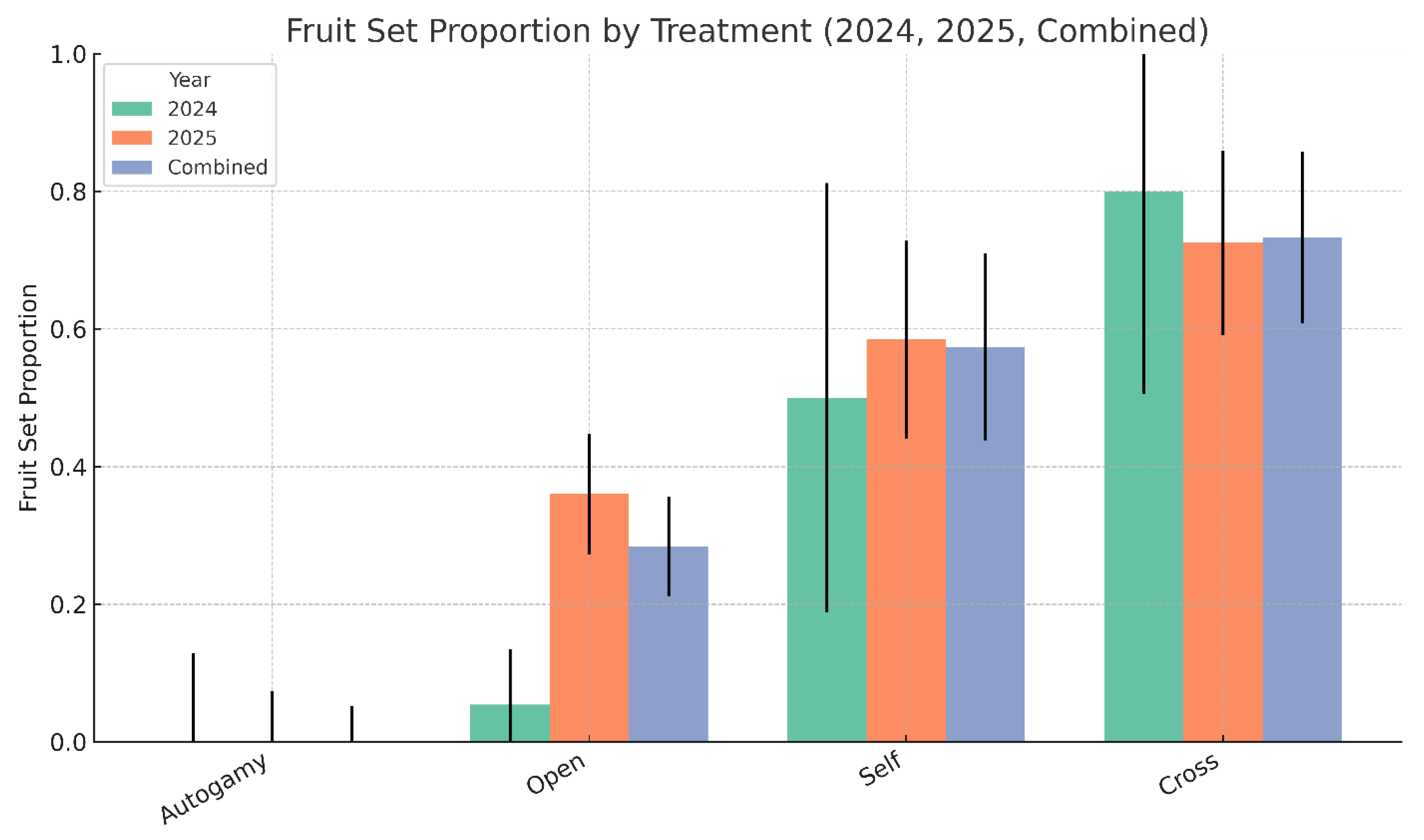

Figure 11.

Fruit set proportion by pollination treatment in 2024, 2025, and the combined dataset. Bars represent the mean proportion of flowers that set fruit for each treatment: Autogamy, Open Pollination, Hand Self-Pollination, and Hand Outcross-Pollination. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals calculated using the Wilson method. Hand cross-pollination consistently yielded the highest fruit set across years, while autogamy resulted in no fruit production in either year.

Figure 11.

Fruit set proportion by pollination treatment in 2024, 2025, and the combined dataset. Bars represent the mean proportion of flowers that set fruit for each treatment: Autogamy, Open Pollination, Hand Self-Pollination, and Hand Outcross-Pollination. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals calculated using the Wilson method. Hand cross-pollination consistently yielded the highest fruit set across years, while autogamy resulted in no fruit production in either year.

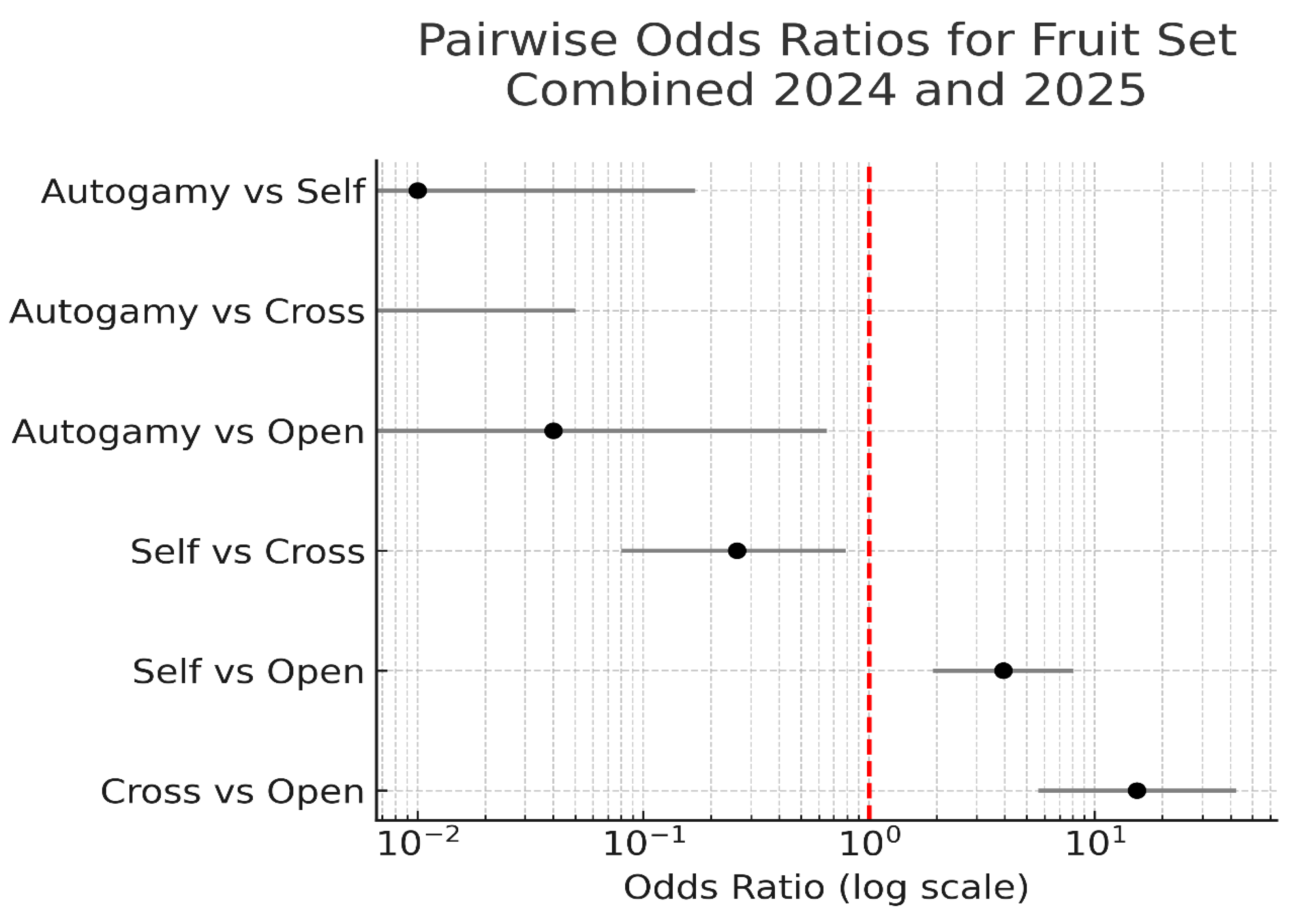

Figure 12.

Pairwise odds ratios comparing fruit set success among pollination treatments using combined data from 2024 and 2025. Odds ratios were calculated using 2 × 2 contingency tables with Wilson 95% confidence intervals. Values greater than 1 indicate that the first treatment listed had higher odds of fruit set than the second. A red dashed line at odds ratio = 1 denotes no difference between treatments. Autogamy consistently underperformed all other treatments, while hand cross-pollination showed significantly greater odds of fruit set compared to both open and self-pollination.

Figure 12.

Pairwise odds ratios comparing fruit set success among pollination treatments using combined data from 2024 and 2025. Odds ratios were calculated using 2 × 2 contingency tables with Wilson 95% confidence intervals. Values greater than 1 indicate that the first treatment listed had higher odds of fruit set than the second. A red dashed line at odds ratio = 1 denotes no difference between treatments. Autogamy consistently underperformed all other treatments, while hand cross-pollination showed significantly greater odds of fruit set compared to both open and self-pollination.

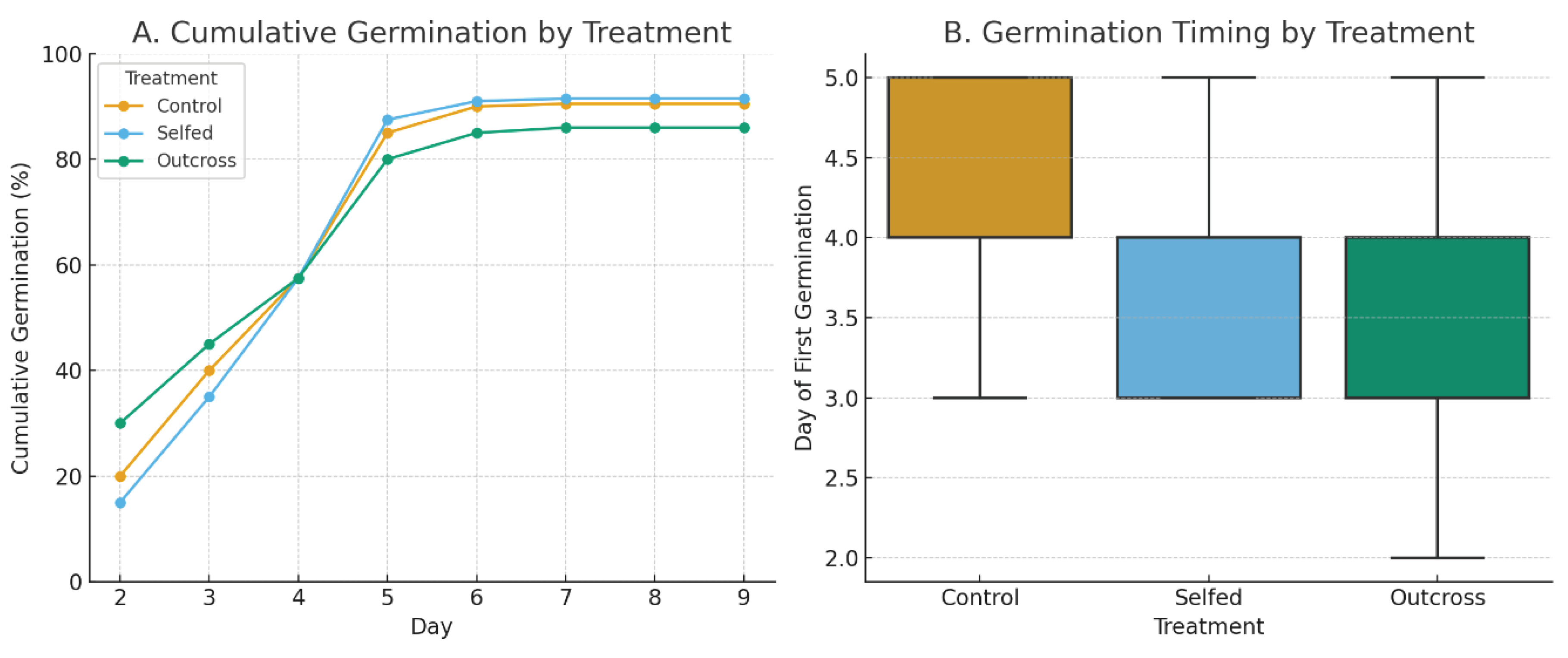

Figure 13.

Germination of Hibiscus dasycalyx seeds across pollination treatments. (A) Cumulative germination expressed as percentage of total seeds (n = 200 per treatment) over a 9-day period. (B) Timing of first germination by treatment, shown as boxplots with median, interquartile range, and minimum–maximum values. Treatments included control (open-pollinated), selfed, and outcrossed flowers.

Figure 13.

Germination of Hibiscus dasycalyx seeds across pollination treatments. (A) Cumulative germination expressed as percentage of total seeds (n = 200 per treatment) over a 9-day period. (B) Timing of first germination by treatment, shown as boxplots with median, interquartile range, and minimum–maximum values. Treatments included control (open-pollinated), selfed, and outcrossed flowers.

Table 1.

Comparison of environmental variables between LL (natural population) and PERL (experimental population) sites, reported as mean ± standard error (SE). Two-sample t-tests were used to evaluate site differences. Soil moisture scores were identical between sites and could not be tested.

Table 1.

Comparison of environmental variables between LL (natural population) and PERL (experimental population) sites, reported as mean ± standard error (SE). Two-sample t-tests were used to evaluate site differences. Soil moisture scores were identical between sites and could not be tested.

| Variable |

LL Mean ± SE |

PERL Mean ± SE |

t-statistic |

p-value |

| Soil pH |

5.92 ± 0.09 |

5.50 ± 0.00 |

4.499 |

0.0003 |

| Soil Temperature (°C) |

24.78 ± 0.13 |

24.00 ± 0.00 |

6.018 |

<0.0001 |

| Soil Moisture (score) |

4.00 ± 0.00 |

4.00 ± 0.00 |

— |

— |

| Light (score) |

5.20 ± 0.20 |

6.00 ± 0.00 |

4 |

0.0161 |

| Canopy Openness (%) |

88.19 ± 3.29 |

96.17 ± 3.83 |

1.578 |

0.1308 |

Table 2.

Site, year, number of flowering plants, total number of flowers produced, duration of population flowering, synchrony of flowering within population, and mean ± SE flower production per flowering plant.

Table 2.

Site, year, number of flowering plants, total number of flowers produced, duration of population flowering, synchrony of flowering within population, and mean ± SE flower production per flowering plant.

| Site |

Year |

Plants Flowering |

Flowers Produced |

Duration of Flowering (Dates, Days) |

Synchrony |

Flowers/Flowering Plant (Mean ± SE) |

| LL |

2024 |

20 |

335 |

15 May–4 Aug (82 days) |

0.650 |

16.75 ± 3.54 |

| PERL |

2024 |

5 |

35 |

7–27 Jun (20 days) |

0.375 |

5.00 ± 1.27 |

| PERL |

2025 |

4 |

150 |

3 Jun–23 Jul (50 days) |

0.419 |

30.0 ± 20.34 |

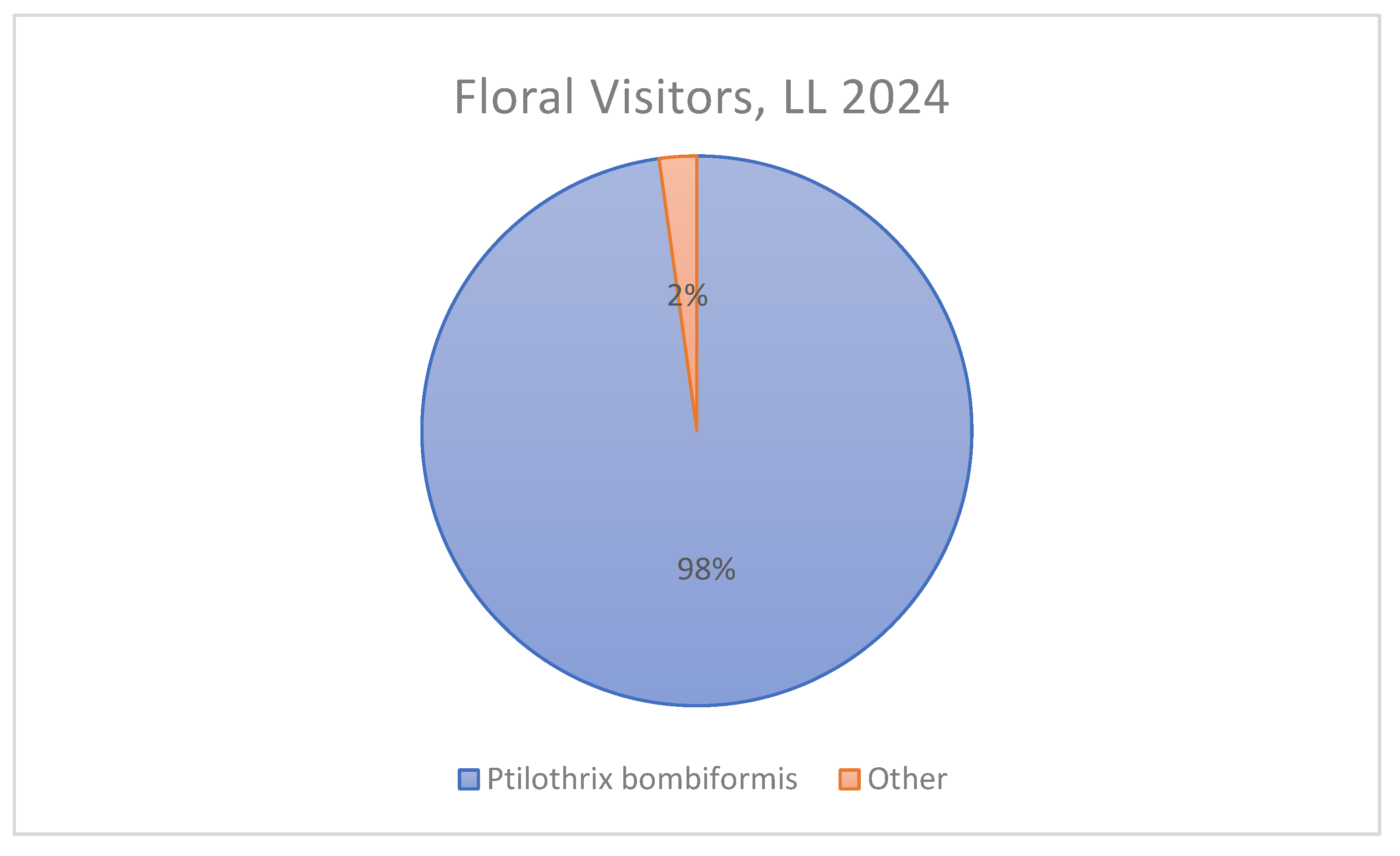

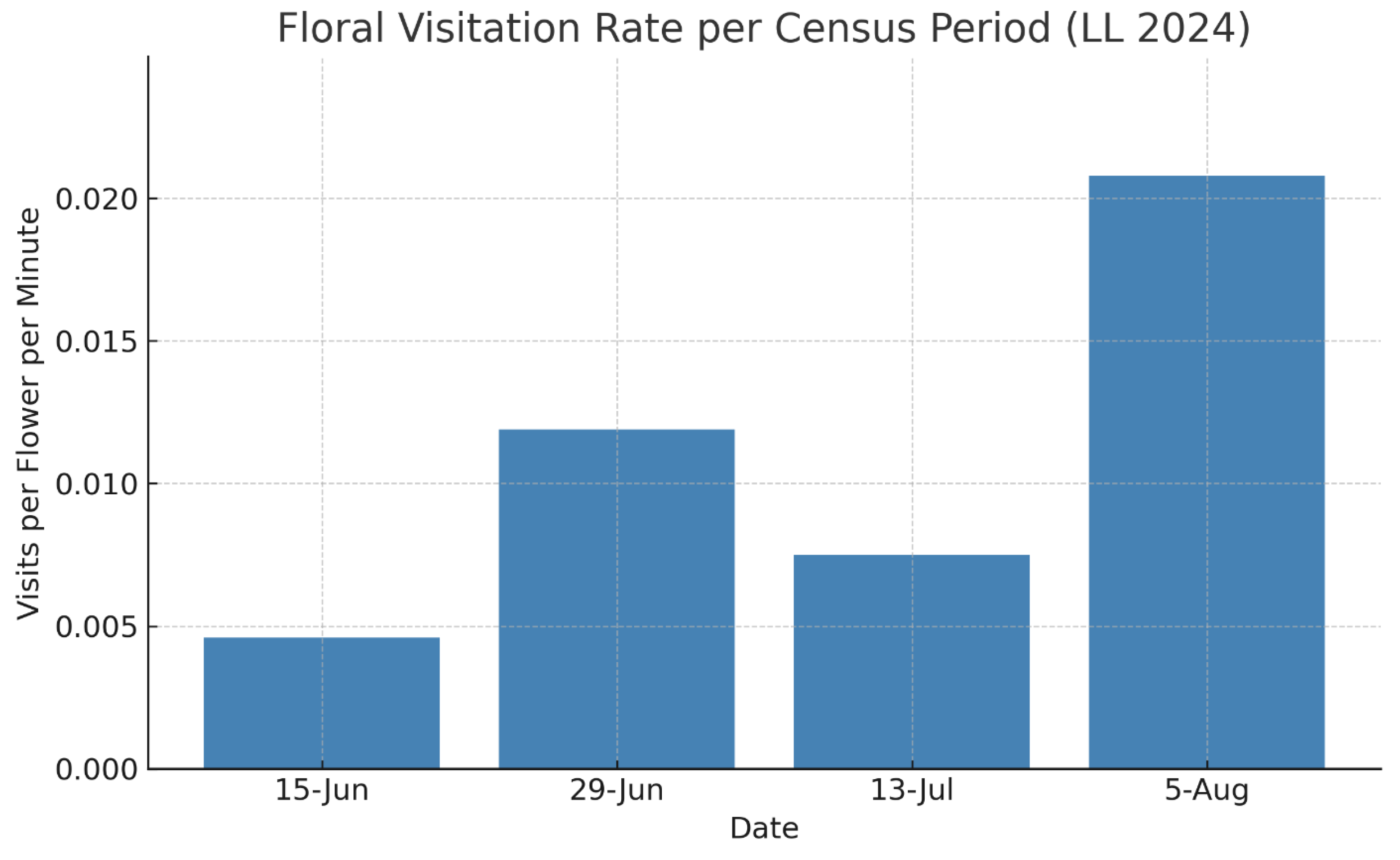

Table 3.

Floral visitation data for Hibiscus dasycalyx at the LL site during the 2024 flowering season. Observations summarize flower abundance, visitation frequency, and pollinator composition across four census dates. Ptilothrix bombiformis dominated the floral visitor community.

Table 3.

Floral visitation data for Hibiscus dasycalyx at the LL site during the 2024 flowering season. Observations summarize flower abundance, visitation frequency, and pollinator composition across four census dates. Ptilothrix bombiformis dominated the floral visitor community.

| Date |

Flowers Observed |

Observation Time (min) |

Total Visits |

% Visits by

Ptilothrix bombiformis

|

Visitor Species Richness |

| 15 Jun |

73 |

435 |

145 |

95.2% |

8 |

| 29 Jun |

62 |

423 |

313 |

99.7% |

2 |

| 13 Jul |

22 |

187 |

31 |

100% |

1 |

| 5 Aug |

4 |

240 |

20 |

85.0% |

4 |

| Total |

151 |

1285 |

509 |

97.8% |

|

Table 5.

Floral visitation observations for Hibiscus dasycalyx at PERL in June 2024. Flowers were observed on multiple dates for a total of 515 minutes. Only two visits, both by Melissodes bimaculatus, were recorded.

Table 5.

Floral visitation observations for Hibiscus dasycalyx at PERL in June 2024. Flowers were observed on multiple dates for a total of 515 minutes. Only two visits, both by Melissodes bimaculatus, were recorded.

| Date |

Observation Time |

# Flowers |

Total Visits |

Floral Visitor |

| 7 Jun 2024 |

14:00–14:30 |

2 |

0 |

— |

| 10 Jun 2024 |

14:50–15:30 |

2 |

0 |

— |

| 12 Jun 2024 |

14:45–15:30 |

2 |

0 |

— |

| 13 Jun 2024 |

09:00–10:40 |

7 |

2 |

Melissodes bimaculatus |

| 12 Jun 2024 |

15:00–15:30 |

2 |

0 |

— |

| 17 Jun 2024 |

15:15–15:45 |

4 |

0 |

— |

| Total |

515 min |

12 |

2 |

1 species |

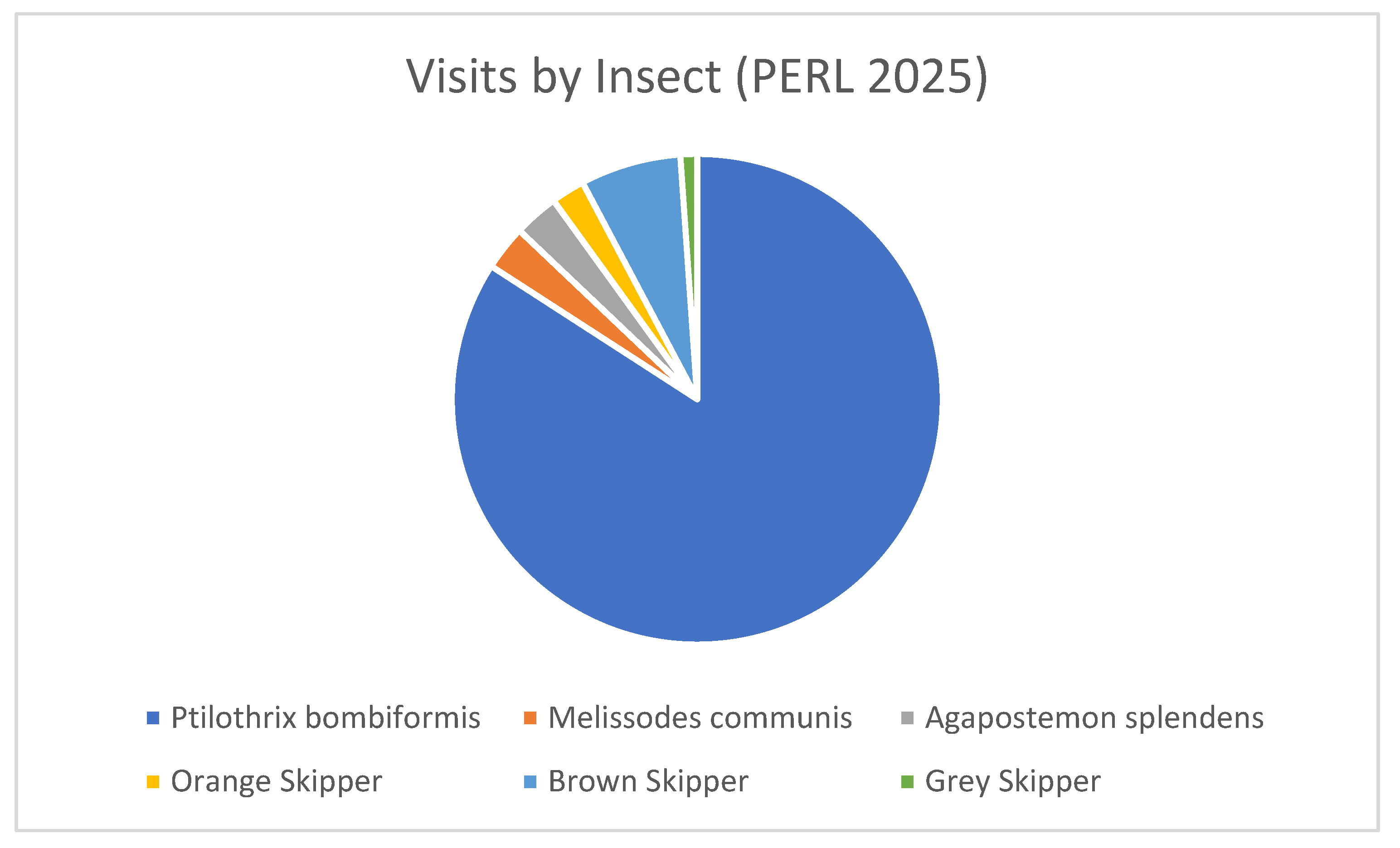

Table 7.

Handling time (seconds) of 139 floral visits to Hibiscus dasycalyx at PERL in 2025 for species with at least ≥4 observations. Values are means ± SE, with ranges in parentheses. A Kruskal-Wallis test across species found significant differences in foraging time (H = 16.17, p = 0.00031).

Table 7.

Handling time (seconds) of 139 floral visits to Hibiscus dasycalyx at PERL in 2025 for species with at least ≥4 observations. Values are means ± SE, with ranges in parentheses. A Kruskal-Wallis test across species found significant differences in foraging time (H = 16.17, p = 0.00031).

| Species |

n |

Handling Time (s) (Mean ± SE, Range) |

| Agapostemon splendens |

8 |

73.5 ± 25.6 (16–229) |

| Melissodes communis |

9 |

26.2. ± 7.26. (1–56) |

| Ptilothrix bombiformis |

122 |

14.1 ± 1.68 (1-134) |

Table 8.

Handling time (seconds) of Ptilothrix bombiformis by behavior. Values are means ± SE, with ranges in parentheses. Welch’s t-test (unequal variance) was highly significant (t = 3.89, p = 0.00075). Not recorded are mixed foraging bouts and fly-by’s.

Table 8.

Handling time (seconds) of Ptilothrix bombiformis by behavior. Values are means ± SE, with ranges in parentheses. Welch’s t-test (unequal variance) was highly significant (t = 3.89, p = 0.00075). Not recorded are mixed foraging bouts and fly-by’s.

| Behavior |

n |

Handling Time (s) (Mean ± SE, Range) |

| Nectaring |

7 |

5 (2-14) |

| Pollen gathering |

107 |

14.4 ± 1.81 (1–134) |

Table 9.

Results of pollination treatments in Hibiscus dasycalyx at LL, 2024–2025. Values are number of flowers, fruits, and percentage fruit set.

Table 9.

Results of pollination treatments in Hibiscus dasycalyx at LL, 2024–2025. Values are number of flowers, fruits, and percentage fruit set.

| Year |

Plants Used (Tag ID)* |

Treatment |

Flowers (N) |

Fruits |

Fruit Set (%) |

| 2024 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9 |

Autogamy |

11 |

0 |

0 |

| |

|

Open (Control) |

37 |

2 |

3.5 |

| |

|

Selfed |

6 |

3 |

50 |

| |

|

Crossed |

5 |

4 |

80 |

| 2025 |

2, 3, 5, 6, 9 |

Autogamy |

22 |

0 |

0 |

| |

|

Open (Control) |

108 |

41 |

38 |

| |

|

Selfed |

41 |

28 |

68 |

| |

|

Crossed |

39 |

34 |

87 |