1. Introduction

The Michelson-Morley experiment (1887) yielded a null result, indicating equal light travel times along the longitudinal and transverse arms of an interferometer. This finding is traditionally interpreted as evidence against the existence of a luminiferous ether.

The Michelson–Morley experiment (1887) [

1] aimed to detect Earth’s motion through a hypothetical medium for light propagation, historically termed the “ether.” The experiment’s null result, showing equal light travel times in orthogonal arms, challenged the existence of such a medium and paved the way for Einstein’s special relativity [

3]. However, alternative interpretations proposing a medium—modeled as a property of space itself or a field—have persisted [

5,

6]. This paper reexamines the experiment within the reference frame of a hypothetical propagation medium, modeled not as a classical ether but as a property of space or a field. We derive a general relationship between longitudinal and transverse dimensional changes that is both necessary and sufficient to explain the null result.

2. Historical Background

In the late 19th century, the luminiferous ether was hypothesized as the medium for light propagation. Michelson and Morley [

1] designed an interferometer to detect Earth’s motion relative to this medium, expecting interference fringe shifts due to differing light travel times. The null result contradicted expectations, prompting Lorentz [

2] to propose length contraction in the direction of motion, later generalized by FitzGerald [

4]. Einstein’s special relativity [

3] explained the null result without a medium, but medium-based models have been proposed [

5,

6,

7], motivating this generalized analysis.

3. Definitions

We consider the interferometer in the reference frame of a hypothetical medium, modeled as a property of space or a field, through which light propagates at speed c. We define:

: longitudinal dilation/contraction factor, .

: transverse dilation/contraction factor, .

: proper arm length measured when the interferometer is at rest relative to the propagation medium.

Our goal is to find the relationship between and that ensures equal light travel times in both arms.

4. Longitudinal Arm Analysis

To analyze the light path in the longitudinal arm, we consider the round-trip time in the frame of the medium:

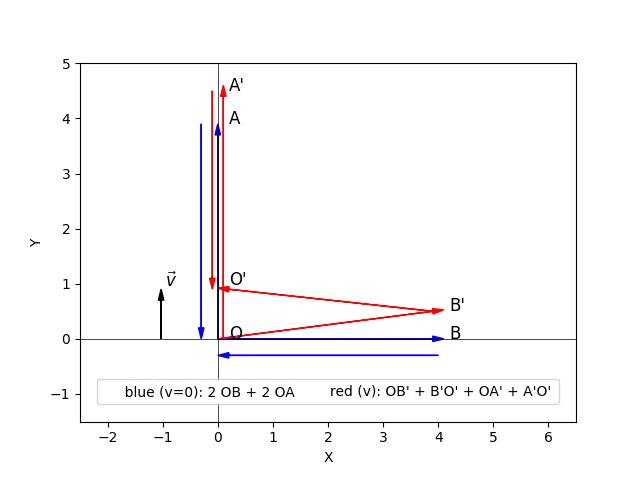

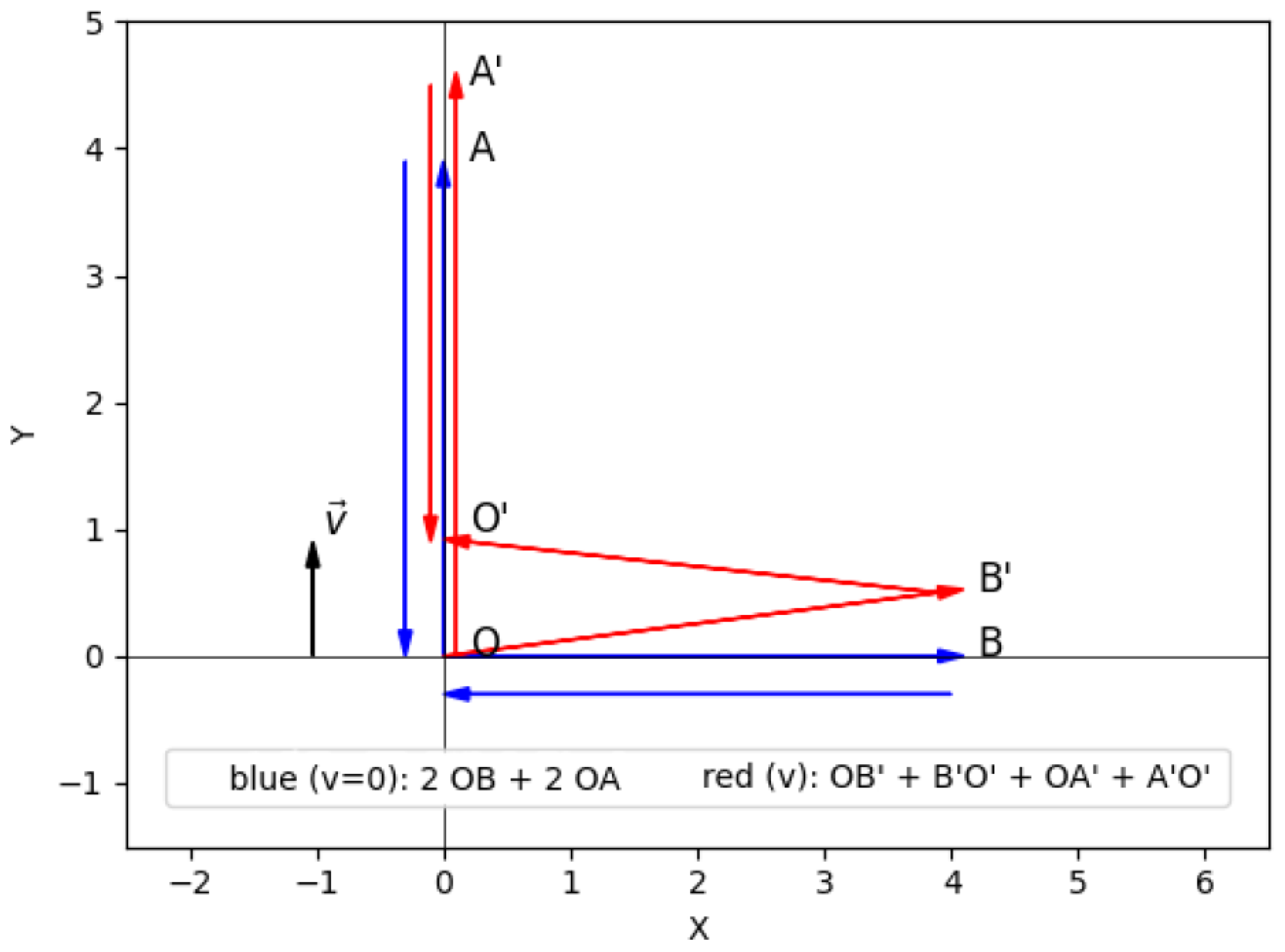

Figure 1.

Photon Trajectories in the Stationary and Moving Michelson–Morley Interferometer

Figure 1.

Photon Trajectories in the Stationary and Moving Michelson–Morley Interferometer

In the medium frame:

5. Transverse Arm Analysis

For the transverse arm:

6. Equality Condition

Equal travel times require:

Solving for the ratio:

Thus:

Table 1.

Complete analysis of light paths in the Michelson-Morley experiment (medium frame).

Table 1.

Complete analysis of light paths in the Michelson-Morley experiment (medium frame).

| Parameter |

Longitudinal Arm |

Transverse Arm |

| Arm length in medium frame |

|

|

| Relative speed (medium frame) |

|

|

| One-way time |

|

|

| Round-trip time |

|

|

| Round-trip distance |

|

|

| Null result condition |

|

| Lorentz special case |

|

7. Invariance of the Null Result for an Arbitrary Initial Velocity

The derivation in

Section 6 assumed an interferometer starting at rest in the medium frame. A critical test of the model’s consistency is to verify that the null result will be obtained

regardless of the apparatus’s initial state of motion relative to the medium. We now demonstrate this invariance.

7.1. General Proof

Consider an interferometer moving with velocity

relative to the medium. Its arms, as measured in the medium frame, are contracted/dilated according to some functions

and

. The round-trip times for light, calculated in the medium frame, are:

The ratio of these times is:

For the times to be equal (

), the following condition must hold:

which is equivalent to the fundamental relationship derived earlier:

This simple calculation shows that

the null result is guaranteed for any velocity , provided the deformation factors satisfy Eq. (4). The specific functional forms of

and

are irrelevant; only the constraint on their ratio matters for the Michelson-Morley outcome. This reveals that the experimental null result only fixes the

ratio between the transverse and longitudinal deformations, leaving the individual functions underdetermined.

7.2. The Lorentz Contraction as a Special Case

The framework presented here is more general than the historical interpretation. The traditional Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction postulate corresponds to a specific, restrictive choice for the deformation functions:

This choice clearly satisfies the general condition (

4), as

. However, it is merely one particular solution among an infinite set of possibilities.

Any pair of functions satisfying is consistent with the Michelson-Morley experiment. For example, an isotropic scaling of the entire apparatus () is ruled out, but a scenario with a mild longitudinal contraction and a slight transverse dilation is perfectly admissible. The Lorentz solution is therefore a special case of the more general condition derived in this work. It imposes the additional, experimentally unmotivated constraints that the transverse dimension remains absolutely unchanged () and that the longitudinal contraction takes its maximal form. The Michelson-Morley experiment alone cannot distinguish between the Lorentz case and other solutions satisfying the general ratio; it only mandates the relationship between the two deformations.

8. Discussion

The derived condition, , ensures the Michelson–Morley null result in a medium-based framework. Key features:

At (i.e., when the interferometer is at rest relative to the propagation medium), , implying no anisotropic dimensional changes.

For , the transverse arm contracts relative to the longitudinal arm, generalizing the Lorentz contraction (which corresponds to ).

The relationship holds invariantly for arbitrary inertial frames, as proven in

Section 7.

The generality of this framework—where only the ratio between deformations is constrained—allows for various physical interpretations beyond the specific Lorentz-FitzGerald case. Different medium properties (isotropic or anisotropic) would correspond to different functional forms of and , all satisfying the same fundamental constraint from the null result.

This approach provides a mathematical foundation for exploring alternative medium-based theories without contradicting experimental evidence. Future high-precision interferometry experiments could potentially distinguish between different implementations of this general framework.

9. Conclusion

The Michelson–Morley null result can be reproduced in a medium-based framework if:

This generalizes the Lorentz contraction and supports alternative interpretations where light propagates through a medium modeled as space or a field.

The key insight is that this framework distinguishes between the "true" motion relative to the medium and the "apparent" behavior measured by an observer comoving with the apparatus. While a theory requiring knowledge of absolute velocities relative to the medium would be practically unusable, our approach shows that the measurable physics—the relationships between observed quantities—can be made identical to those of special relativity through the appropriate deformation factors.

In this sense, special relativity emerges as the effective theory for observers who can only measure relative motions, providing the correct operational formulas without reference to any preferred frame. Our medium-based interpretation offers a possible underlying mechanism while remaining empirically equivalent at the level of observable predictions.

This demonstrates that the experimental null result is compatible with multiple theoretical interpretations. Special relativity remains the most economical framework for practical physics, but exploring alternative interpretations can provide valuable insights into the fundamental nature of spacetime.

References

- Michelson, A. A., & Morley, E. W. (1887). On the Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether. American Journal of Science, 34, 333-345.

- Lorentz, H. A. (1904). Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity smaller than that of light. Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, 6, 809-831.

- Einstein, A. (1905). Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. Annalen der Physik, 17(10), 891-921.

- FitzGerald, G. F. (1889). The Ether and the Earth’s Atmosphere. Science, 13(328), 390.

- Prokhovnik, S. J. (1973). The Logic of Special Relativity. Cambridge University Press.

- Cahill, R. T. (2005). The Michelson and Morley 1887 Experiment and the Discovery of Absolute Motion. Progress in Physics, 3, 25-29.

- Mansouri, R., & Sexl, R. U. (1977). A test theory of special relativity: I. Simultaneity and clock synchronization. General Relativity and Gravitation, 8(7), 497-513. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R. J., & Thorndike, E. M. (1932). Experimental Establishment of the Relativity of Time. Physical Review, 42(3), 400-418. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).