Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

28 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Population

2.2. Trial Design and Treatment

2.3. Visits and Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

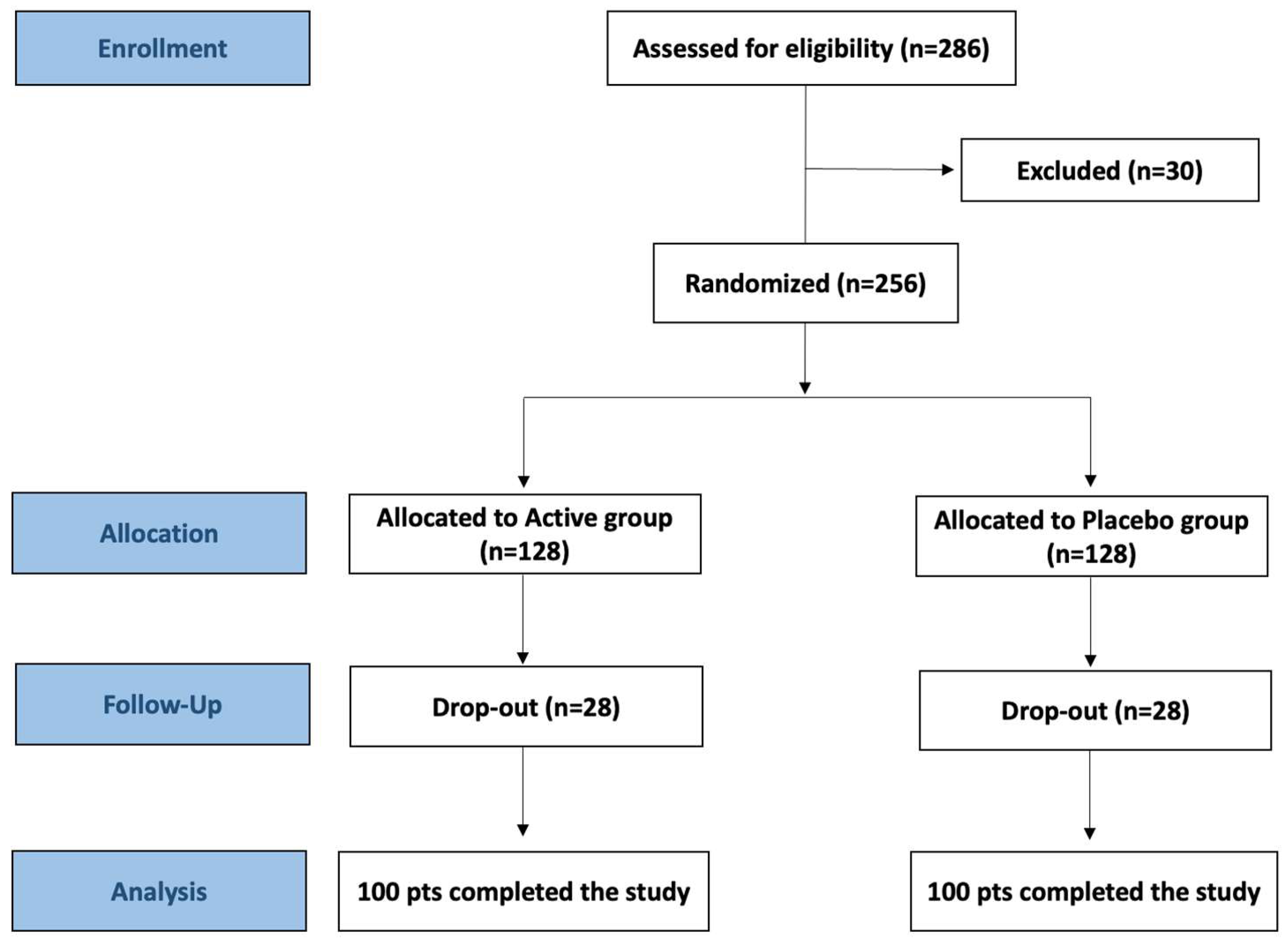

3.1. Participant Flow

3.2. Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

3.3. Effect of Probiotic and Placebo Treatment on Diagnostic Parameters

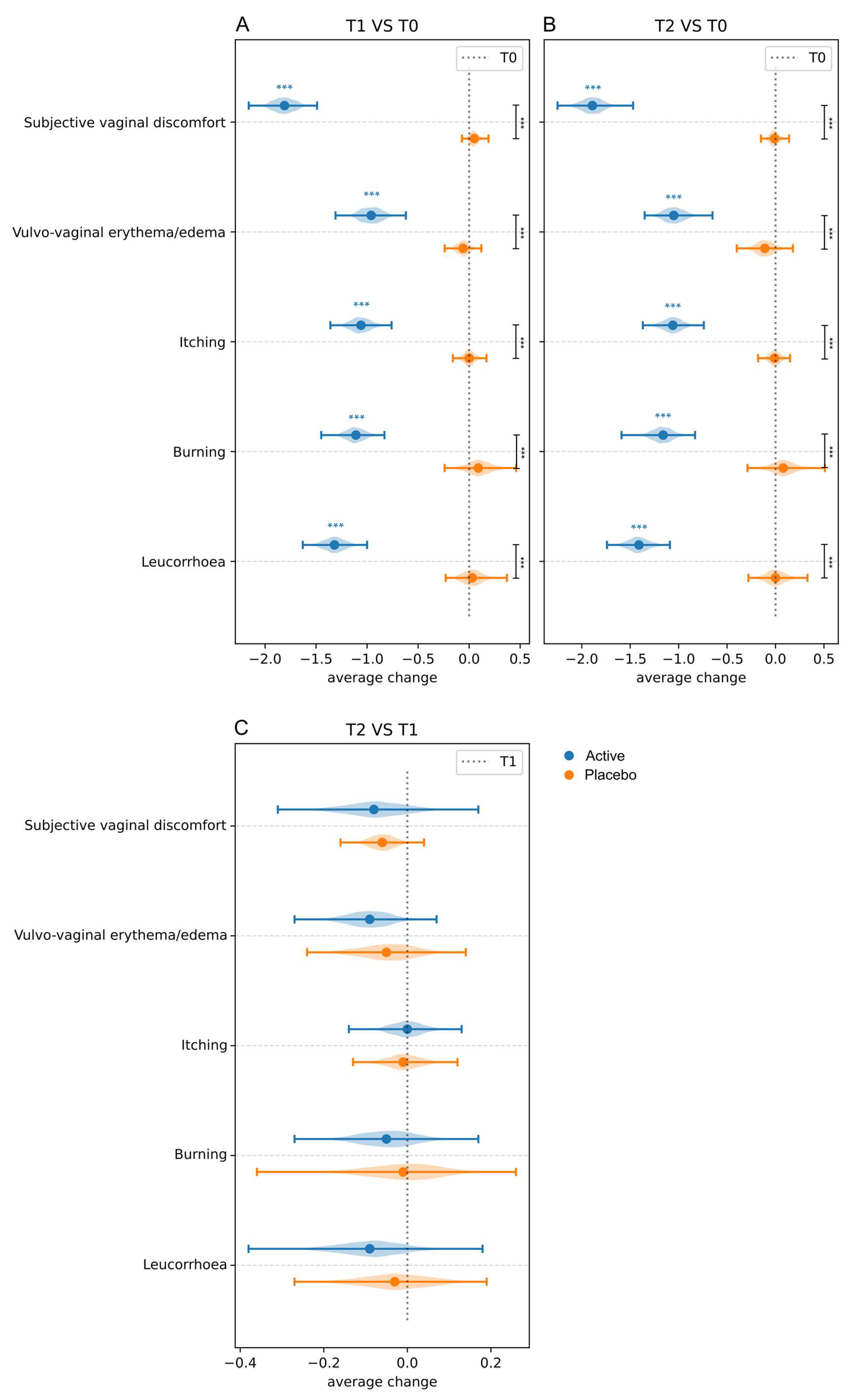

3.3.1. Clinical Signs and Symptoms

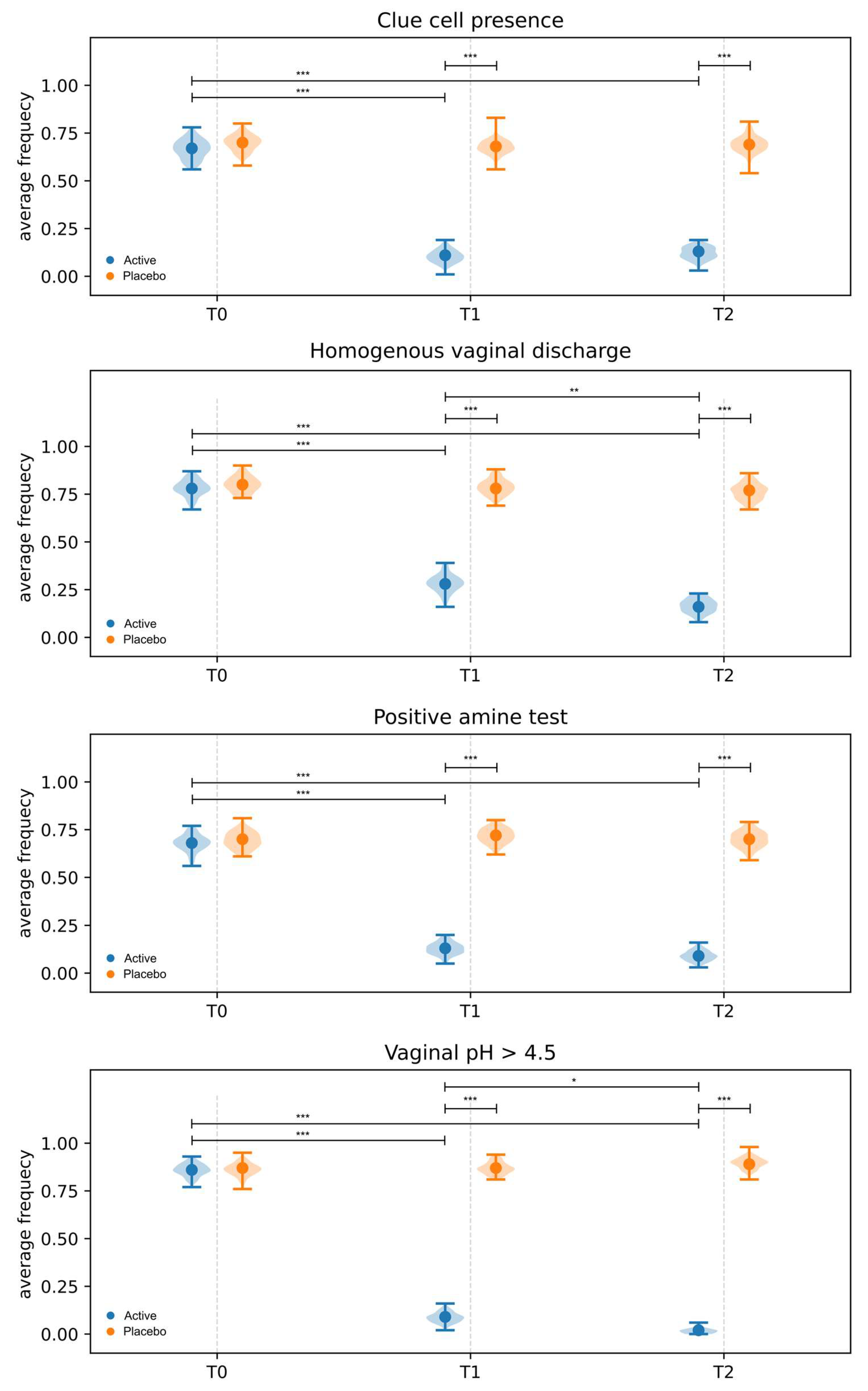

3.3.2. Amsel Criteria

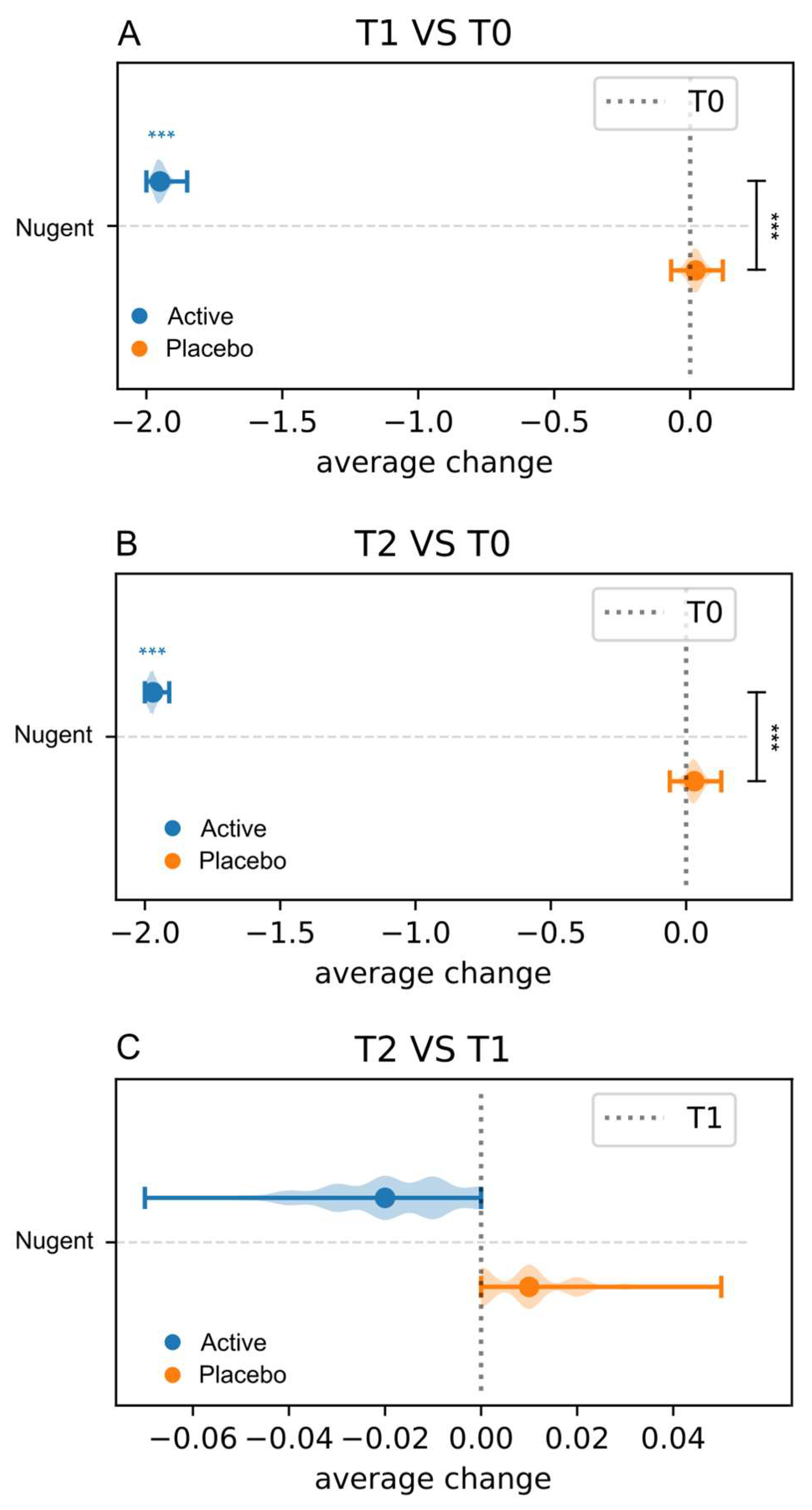

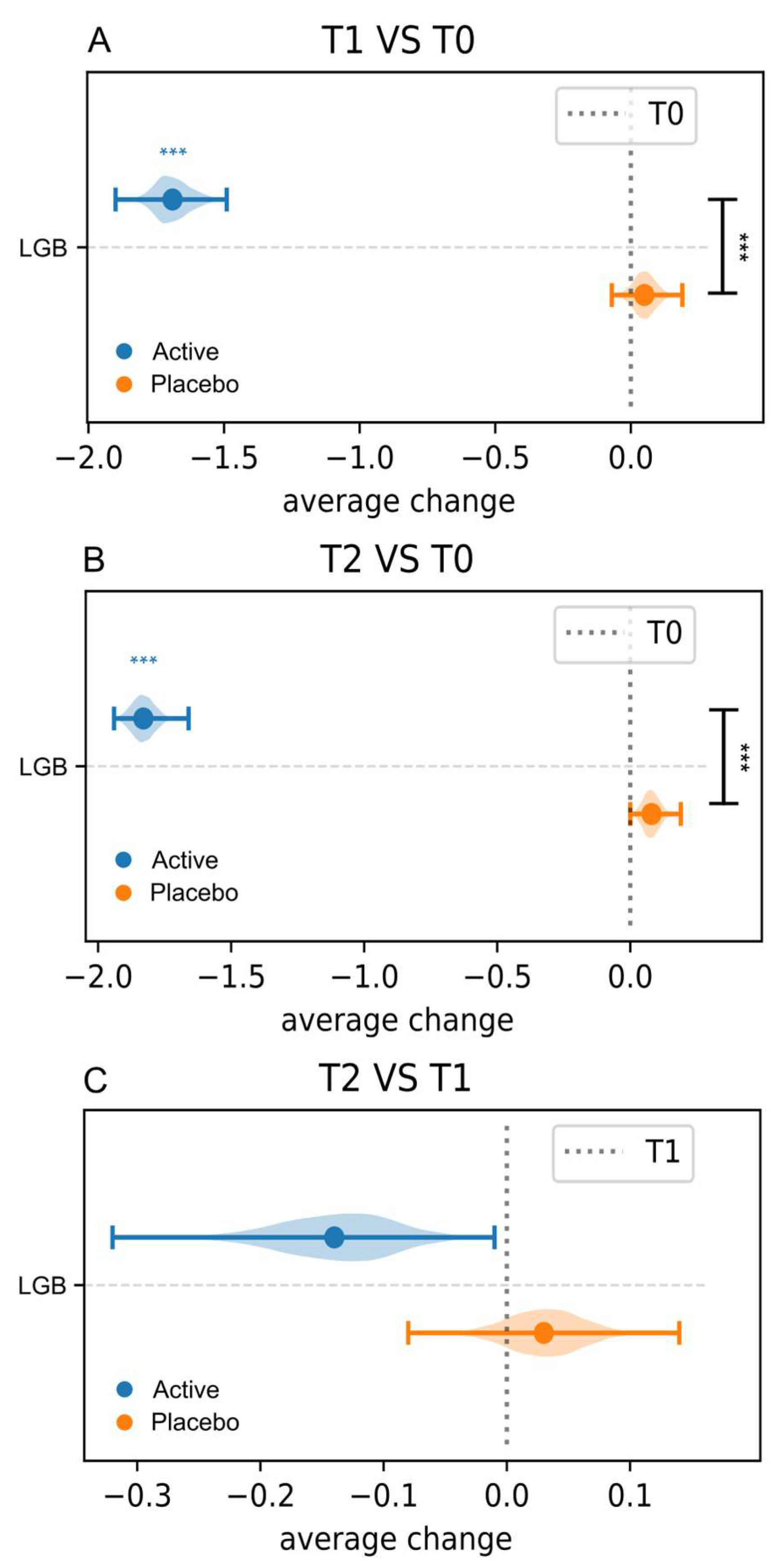

3.3.3. Nugent Score and Lactobacillary Grade

3.3.4. Effect of Probiotic and Placebo Treatment on the Vaginal Microbiota Composition

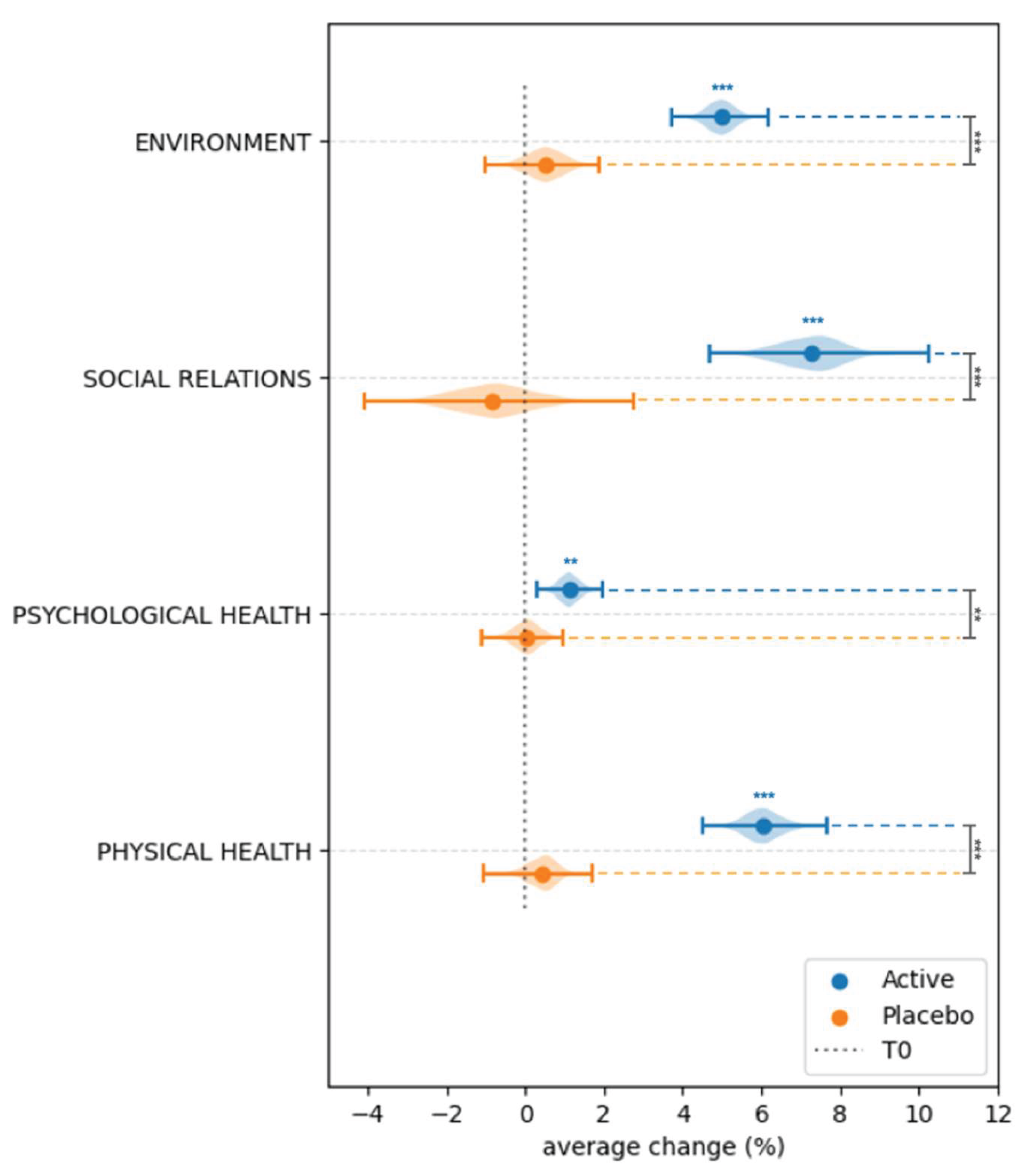

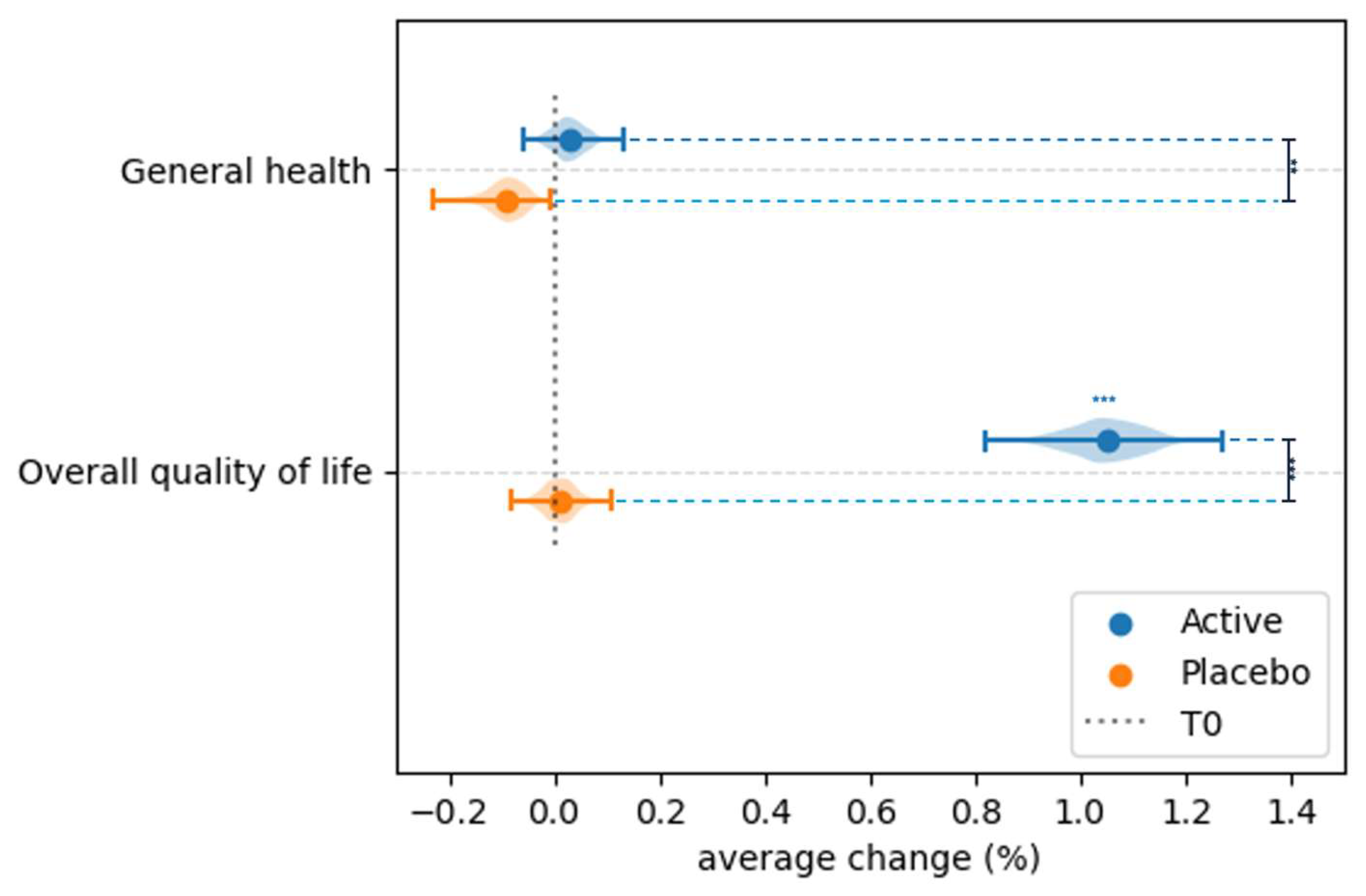

3.4. Effect of Probiotic and Placebo Treatment on the Perceived Quality of Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mei, Z. , Li, D. The role of probiotics in vaginal health. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022, 12, 963868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappello, C. , Acin-Albiac, M., Pinto, D., Polo, A., Filannino, P., Rinaldi, F., Gobbetti, M., Di Cagno, R. Do nomadic lactobacilli fit as potential vaginal probiotics? The answer lies in a successful selective multi-step and scoring approach. Microb Cell Fact, 22.

- Shen, X. , Xu, L., Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., Li, P., Ma, T., Guo, S., Kwok, L.Y., Sun, Z. Postbiotic gel relieves clinical symptoms of bacterial vaginitis by regulating the vaginal microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1114364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, A. , Hiippala, K., Ronkainen, A., Vaccalluzzo, A., Caggia, C., Satokari, R., Randazzo, C.L. Adhesion Properties and Pathogen Inhibition of Vaginal-Derived Lactobacilli. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. [CrossRef]

- Das, S. , Bhattacharjee, M.J., Mukherjee, A.K., Khan, M.R. Recent advances in understanding of multifaceted changes in the vaginal microenvironment: implications in vaginal health and therapeutics. Crit Rev Microbiol, 49.

- Chee, W.J.Y. , Chew, S.Y., Than, L.T.L. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microb Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachedjian, G. , Aldunate, M., Bradshaw, C.S., Cone, R.A. The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res Microbiol. 2017, 168, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y. , Liu, Z., Chen, T. Role of vaginal microbiota dysbiosis in gynecological diseases and the potential interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 643422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladine, H.L. , Desai, U.A. Vaginitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician, 97.

- Qi, W. , Li, H., Wang, C., Li, H., Zhang, B., Dong, M., Fan, A., Han, C., Xue, F. Recent Advances in Presentation, Diagnosis and Treatment for Mixed Vaginitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 7597; 11. [Google Scholar]

- Zuñiga Vinueza, A.M. Probiotics for the Prevention of Vaginal Infections: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024, 16, e64473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abavisani, M. , Sahebi, S., Dadgar, F., Peikfalak, F., Keikha, M. The role of probiotics as adjunct treatment in the prevention and management of gynecological infections: An updated meta-analysis of 35 RCT studies. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol, 63.

- Stavropoulou, E. , Bezirtzoglou, E. Probiotics in Medicine: A Long Debate. Front Immunol, 2192; 11. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, C. , Lima, M., Trieu-Cuot, P., Ferreira, P. To give or not to give antibiotics is not the only question. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021, 21, e191–e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, A. , Vaccalluzzo, A., Caggia, C., Balzaretti, S., Vanella, L., Sorrenti, V., Ronkainen, A., Satokari, R., Randazzo, C.L. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus CA15 (DSM 33960) as a Candidate Probiotic Strain for Human Health. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapisarda, A.M.C. , Pino, A., Grimaldi, R.L., Caggia, C., Randazzo, C.L., Cianci, A. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus CA15 (DSM 33960) strain as a new driver in restoring the normal vaginal microbiota: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Front Surg, 5612. [Google Scholar]

- Hopewell, S. , Chan, A.W., Collins, G.S., Hróbjartsson, A., Moher, D., Schulz, K.F., Tunn, R., Aggarwal, R., Berkwits, M., Berlin, J.A., Bhandari, N., Butcher, N.J., Campbell, M.K., Chidebe, R.C.W., Elbourne, D., Farmer, A., Fergusson, D.A., Golub, R.M., Goodman, S.N., Hoffmann, T.C., Ioannidis, J.P.A., Kahan, B.C., Knowles, R.L., Lamb, S.E., Lewis, S., Loder, E., Offringa, M., Ravaud, P., Richards, D.P., Rockhold, F.W., Schriger, D.L., Siegfried, N.L., Staniszewska, S., Taylor, R.S., Thabane, L., Torgerson, D., Vohra, S., White, I.R., Boutron, I. CONSORT 2025 statement: updated guideline for reporting randomized trials. Nat Med. 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.W. , Boutron, I., Hopewell, S., Moher, D., Schulz, K.F., Collins, G.S., Tunn, R., Aggarwal, R., Berkwits, M., Berlin, J.A., Bhandari, N., Butcher, N.J., Campbell, M.K., Chidebe, R.C.W., Elbourne, D.R., Farmer, A.J., Fergusson, D.A., Golub, R.M., Goodman, S.N., Hoffmann, T.C., Ioannidis, J.P.A., Kahan, B.C., Knowles, R.L., Lamb, S.E., Lewis, S., Loder, E., Offringa, M., Ravaud, P., Richards, D.P., Rockhold, F.W., Schriger, D.L., Siegfried, N.L., Staniszewska, S., Taylor, R.S., Thabane, L., Torgerson, D.J., Vohra, S., White, I.R., Hróbjartsson, A. SPIRIT 2025 statement: updated guideline for protocols of randomized trials. Nat Med, 1784; 31. [Google Scholar]

- Amsel, R. , Totten, P.A., Spiegel, C.A., Chen, K.C., Eschenbach, D., Holmes, K.K. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983, 74, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugent, R.P. , Krohn, M.A., Hillier, S.L. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991, 29, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donders, G.G. Definition and classification of abnormal vaginal flora. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007, 21, 355–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998, 28, 551–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, J.D. , Vempati, Y.S. Bacterial Vaginosis and Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Pathophysiologic Interrelationship. Microorganisms. 2024, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Moreno, A. , Aguilera, M. Vaginal Probiotics for Reproductive Health and Related Dysbiosis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 1461. 10, 1461.

- Liu, P. , Lu, Y., Li, R., Chen, X. Use of probiotic lactobacilli in the treatment of vaginal infections: In vitro and in vivo investigations. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 1153; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Takada, K. , Melnikov, V.G., Kobayashi, R., Komine-Aizawa, S., Tsuji, N.M., Hayakawa, S. Female reproductive tract-organ axes. Front Immunol, 1110; 14. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, B.D. , Jabri, B., Bendelac, A. Diverse developmental pathways of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018, 18, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, A.M. , Neugent, M.L., De Nisco, N.J., Mysorekar, I.U. Gut-bladder axis enters the stage: Implication for recurrent urinary tract infections. Cell Host Microbe, 1066; 30. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B. , A, D. , Qin, H., Mi, L., & Zhang, D. Correlation analysis of vaginal microbiome changes and bacterial vaginosis plus vulvovaginal candidiasis mixed vaginitis prognosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 2022. 12, 860589. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccalluzzo, A. , Pino, A., Grimaldi, R.L., Caggia, C., Cianci, S., Randazzo, C.L. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus TOM 22.8 (DSM 33500) is an effective strategy for managing vaginal dysbiosis, rising the lactobacilli population. J Appl Microbiol. 2024, 135, lxae110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, A. , Rapisarda, A.M.C., Vaccalluzzo, A., Sanfilippo, R.R., Coman, M.M., Grimaldi, R.L., Caggia, C., Randazzo, C.L., Russo, N., Panella, M.M., Cianci, A., Verdenelli, M.C. Oral Intake of the Commercial Probiotic Blend Synbio® for the Management of Vaginal Dysbiosis. J Clin Med.

- Chen, C. , Hao, L., Zhang, Z., Tian, L., Zhang, X., Zhu, J., Jie, Z., Tong, X., Xiao, L., Zhang, T., Jin, X., Xu, X., Yang, H., Wang, J., Kristiansen, K., Jia, H. Cervicovaginal microbiome dynamics after taking oral probiotics. J Genet Genomics. 2021, 48, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. , Lyu, J., Ge, L., Huang, L,. Peng, Z., Liang, Y., Zhang, X., Fan, S. Probiotic Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Limosilactobacillus reuteri RC-14 as an Adjunctive Treatment for Bacterial Vaginosis Do Not Increase the Cure Rate in a Chinese Cohort: A Prospective, Parallel-Group, Randomized, Controlled Study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

- Husain, S. , Allotey, J., Drymoussi, Z., Wilks, M., Fernandez-Felix, B.M., Whiley, A., Dodds, J., Thangaratinam, S., McCourt, C., Prosdocimi, E.M., Wade, W.G., de Tejada, B.M., Zamora, J., Khan, K., Millar, M. Effects of oral probiotic supplements on vaginal microbiota during pregnancy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with microbiome analysis. BJOG.

- Yang, S. , Reid, G., Challis, J.R.G., Gloor, G.B., Asztalos, E., Money, D., Seney, S., Bocking, A.D. Effect of Oral Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14 on the Vaginal Microbiota, Cytokines and Chemokines in Pregnant Women. Nutrients.

- Anukam, K. , Osazuwa, E., Ahonkhai, I., Ngwu, M., Osemene, G., Bruce, A.W., Reid, G. Augmentation of antimicrobial metronidazole therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Microbes Infect.

- Martinez, R.C. , Franceschini, S.A., Patta, M.C., Quintana, S.M., Gomes, B.C., De Martinis, E.C., Reid, G. Improved cure of bacterial vaginosis with single dose of tinidazole (2 g), Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1, and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Can J Microbiol.

- De Alberti, D. , Russo, R., Terruzzi, F., Nobile, V., Ouwehand, A.C. Lactobacilli vaginal colonisation after oral consumption of Respecta(®) complex: a randomised controlled pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet.

- Russo, R. , Edu, A., De Seta, F. Study on the effects of an oral lactobacilli and lactoferrin complex in women with intermediate vaginal microbiota. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018, 298, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, R. , Superti, F., Karadja, E., De Seta, F. Randomised clinical trial in women with Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: Efficacy of probiotics and lactoferrin as maintenance treatment. Mycoses, 62.

- Russo, R. , Karadja, E., De Seta, F. Evidence-based mixture containing Lactobacillus strains and lactoferrin to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis: a double blind, placebo controlled, randomised clinical trial. Benef Microbes, 10.

- Lyra, A. , Ala-Jaakkola, R., Yeung, N., Datta, N., Evans, K., Hibberd, A., Lehtinen, M.J., Forssten, S.D., Ibarra, A., Pesonen, T., Junnila, J., Ouwehand, A.C., Baranowski, K., Maukonen, J., Crawford, G., Lehtoranta, L. A Healthy Vaginal Microbiota Remains Stable during Oral Probiotic Supplementation: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Microorganisms, 11.

- Chapple, A. Vaginal thrush: perceptions and experiences of women of south Asian descent. Health Educ Res. 2001, 16, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aballéa, S. , Guelfucci, F., Wagner, J., Khemiri, A., Dietz, J.P., Sobel, J., Toumi, M. Subjective health status and health-related quality of life among women with Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidosis (RVVC) in Europe and the USA. Health Qual Life Outcomes.

- Zhu, Y.X. , Li, T., Fan, S.R., Liu, X.P., Liang, Y.H., Liu, P. Health-related quality of life as measured with the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire in patients with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Y. , Lee, A., Fischer, G. Quality of life in patients with chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis: A before and after study on the impact of oral fluconazole therapy. Australas J Dermatol, 58.

- Thomas-White, K. , Navarro, P., Wever, F., King, L., Dillard, L.R., Krapf, J. Psychosocial impact of recurrent urogenital infections: a review. Womens Health, 2023; 19. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, X.Y. , Chung, F.Y., Lee, B.K., Azhar, S.N.A., Sany, S., Roslan, N.S., Ahmad, N., Yusof, S.M., Abdullah, N., Nik Ab Rahman, N.N., Abdul Wahid, N., Deris, Z.Z., Oon, C.E., Wan Adnan, W.F., Liong, M.T. Lactobacilli reduce recurrences of vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Appl Microbiol, 3168. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion criteria |

| Fertile age (18-45 years); regular menstruation; presence of BV (at least 3 Amsel criteria; Nugent score ≥7); co-occurring of AV (diagnosed based on the Donders’ score) and VVC (clinical picture and yeast culture); presence of at least one vaginal symptom (leucorrhea, burning, itching, erythema/oedema or subjective vaginal discomfort); no participation in other clinical studies; consent to participate; willingness to collaborate in completing the study procedures, non-lactating status, appropriate personal hygiene, the cognitive ability for collaboration. |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| Presence of sexually transmitted disease due to Chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Trichomonas vaginalis; presence of specific vaginitis related to acute AV and VVC; clinically apparent herpes simplex infection; precancerous lesions due to Human papillomavirus; human immunodeficiency virus infection; confirmed diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID); recent use of antibiotic and/or antifungal drugs (less than one month); recent consumption of probiotics or food containing probiotics; recent use of immunosuppressive drugs (less than one month); pregnancy or breastfeeding; use of douching; hypersensitivity or allergy to any ingredient of investigational product or placebo; chronic diseases; neoplastic disease; diabetes; genital tract bleeding. |

| Demographic characteristics | Active group (n=100) | Placebo group (n=100) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.58 ± 5.74 | 32.13 ± 6.52 | 0.7727 |

| Body mass index | |||

| <18.5 | 4 | 5 | 0.7369 |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | 81 | 81 | |

| 25 – 29.9 | 8 | 8 | |

| ≥ 30 | 7 | 6 | |

| Smoking habits | 24 | 22 | 0.8667 |

| Contraceptive use | |||

| Oral | 12 | 15 | 0.6796 |

| Barrier | 28 | 30 | 0.8762 |

| Others | 36 | 34 | 0.8822 |

| History of vaginal dysbiosis | 61 | 58 | 0.7733 |

| Sexual activity | 68 | 71 | 0.7588 |

| Clinical characteristics | Active group (n=100) | Placebo group (n=100) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | Leucorrhoea | 95 | 97 | 0.7209 |

| Burning | 92 | 89 | 0.6306 | |

| Itching | 79 | 82 | 0.7214 | |

| Vulvovaginal Erythema/Oedema | 90 | 88 | 0.8217 | |

| Subjective vaginal discomfort | 95 | 97 | 0.7209 | |

| Amsel Criteria | Homogenous vaginal discharge | 78 | 80 | 0.8623 |

| Clue cell presence | 67 | 70 | 0.7609 | |

| Positive amine test | 68 | 70 | 0.8785 | |

| Vaginal pH > 4.5 | 86 | 87 | 1.0000 | |

| Nugent score | 0–3 | 0 | 0 | 0.4738 |

| 4–6 | 3 | 5 | ||

| 7–10 | 97 | 95 | ||

| Lactobacillary grade | I | 0 | 0 | 0.4719 |

| II | 8 | 11 | ||

| III | 92 | 89 | ||

| Microbial groups | Active group (n=100) | Placebo group (n=100) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 |

p-value T0vsT1 |

p-value T0vsT2 |

p-value T1vsT2 |

T0 | T1 | T2 |

p-value T0vsT1 |

p-value T0vsT2 |

p-value T1vsT2 |

|

| Lactobacillus spp. | 3.49 ± 0.08 | 7.19 ± 0.71 | 7.21 ± 0.76 | 3.89 x 10-18* | 3.89 x 10-18* | 0.0033* | 3.51 ± 0.12 | 3.52 ± 0.14 | 3.53 ± 0.34 | 0.1760 | 0.0039* | 0.0216* |

| Enterococcus spp. | 4.93 ± 0.57 | 2.17 ± 0.99 | 2.14 ± 0.86 | 3.89 x 10-18* | 3.89 x 10-18* | 0.0026* | 4.90 ± 0.59 | 4.99 ± 0.57 | 4.98 ± 0.58 | 0.0001* | 0.0000* | 0.7258 |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 3.70 ± 0.36 | 1.83 ± 0.22 | 1.76 ± 0.24 | 3.89 x 10-18* | 3.89 x 10-18* | 0.0023* | 3.69 ± 0.29 | 3.78 ± 0.32 | 3.79 ± 0.33 | 0.0000* | 0.0000* | 0.0237* |

| Gardnerella spp. | 4.41 ± 0.50 | 1.93 ± 0.47 | 1.92 ± 0.21 | 3.89 x 10-18* | 3.89 x 10-18* | 0.0005* | 4.43 ± 0.44 | 4.53 ± 0.36 | 4.44 ± 0.43 | 0.0007* | 0.9014 | 0.0098* |

| Candida spp. | 3.83 ± 0.29 | 1.32 ± 0.81 | 1.34 ± 0.78 | 3.89 x 10-18* | 3.89 x 10-18* | 0.6996 | 3.87 ± 0.42 | 3.95 ± 0.41 | 3.92 ± 0.43 | 0.0006* | 0.0510 | 0.8231 |

| Escherichia coli | 4.02 ± 0.68 | 1.11 ± 0.82 | 1.09 ± 0.81 | 3.89 x 10-18* | 3.89 x 10-18* | 0.1492 | 4.17 ± 0.48 | 4.05 ± 0.52 | 4.11 ± 0.54 | 0.0000* | 0.0890 | 0.0078* |

| Microbial groups | Sampling time | ANCOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect† | p-value | ||

| Lactobacillus spp. | T1 | 3.6978 | 6.23 x 10-117* |

| T2 | 3.6905 | 8.40 x 10-105* | |

| Enterococcus spp. | T1 | -2.8436 | 1.87 x 10-72* |

| T2 | -2.8546 | 5.31 x 10-78* | |

| Staphylococcus spp. | T1 | -1.9538 | 6.66 x 10-118* |

| T2 | -2.0379 | 4.44 x 10-118* | |

| Gardnerella spp. | T1 | -2.5927 | 1.09 x 10-116* |

| T2 | -2.5226 | 5.11 x 10-123* | |

| Candida spp. | T1 | -2.6082 | 1.58 x 10-75* |

| T2 | -2.5624 | 2.95 x 10-74* | |

| Escherichia coli | T1 | -2.8240 | 8.47 x 10-95* |

| T2 | -2.9056 | 9.29 x 10-93* | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).