Ⅰ. Introduction

The behavior of sessile liquid droplets in saturated atmospheres plays a significant role in many industrial applications such as seawater desalination [

1,

2], thermal power plants [

1], and heat pipe cooling [

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, the debate over whether an equilibrium exists between sessile liquid droplets and the surrounding atmosphere in the presence of gravity continues to persist. Under isothermal conditions, the liquid droplet seems reasonable to be in equilibrium with the surroundings saturated in vapor of the liquid. Shanahan [

7] derived the theoretical criteria required for system equilibrium. By incorporating the gravity-induced change in hydrostatic pressure into the Laplace equation, he introduced the variation of droplet meniscus curvature with altitude, and then substituted it into the Kelvin equation to obtain the equilibrium vapor pressure along droplet surface as a function of altitude. He found that this relationship was unlikely to be compatible with the distribution of atmospheric pressure with altitude. Therefore, he concluded that the equilibrium could not be achieved and further indicated that a droplet in an atmosphere saturated with its vapor would evaporate very slowly near the substrate and exhibit slow condensation near the top of the droplet.

Meunier and Bonn [

8] thought such a non-equilibrium state violates the second law of thermodynamics. They pointed out that this apparent paradox stems from the absence of gravity in the Kelvin equation adopted by Shanahan. By extending Kelvin’s equation to account for gravity, they showed the equilibrium vapor pressure along droplet surface is independent of the altitude and thus a sessile drop can be perfectly in equilibrium with its vapor. Siboni et al. [

9,

10], however, contended that incorporation of gravity into the Kelvin equation is unnecessary. Nevertheless, they concurred with Meunier and Bonn that a liquid droplet in the presence of its vapor and a uniform gravitational field can reach equilibrium, while also acknowledging the formal correctness of Shanahan’s analysis.

The equilibrium between a sessile liquid droplet and its environment in the presence of gravity is not only an important theoretical issue but also has significant practical implications. To address this issue, this paper first analyzes the influence of gravity on liquid-gas systems and discusses whether gravitational effects need to be included in the Kelvin equation. Then, by considering variations in the atmospheric pressure as well as in the liquid surface curvature, a generalized Kelvin equation is derived. Using this generalized Kelvin equation instead of the simplified classical form, the equilibrium between a sessile droplet resting on a flat, horizontal solid surface and its surrounding atmosphere is analyzed.

Ⅱ. Effects of Gravity on Liquid-Gas System

In a liquid-vapor system, the state of liquid enclosed by interfaces of different curvatures varies, leading to differences in vapor pressure over curved and flat liquid surfaces. The Kelvin equation quantifies this dependence of vapor pressure on interfacial curvature. When the system is subjected to a gravitational field, should the influence of gravitational effects be incorporated into the Kelvin equation? The answer is no. The Kelvin equation describes how the curvature of the liquid-vapor interface affects the equilibrium between the two phases. Because both liquid and vapor phases are at the same height during the phase transition, the gravity is irrelevant to the transition process and thus need not be included in the Kelvin equation.

Although the gravitational field is irrelevant to Kelvin equation, it can affect the pressure fields inside the fluid phases. At equilibrium, the molar Gibbs energy should be the same in both liquid and gas phases [

11]. This means that, under isothermal conditions and in the presence of gravity, the changes in molar Gibbs energy

=0, which yields

for an incompressible liquid phase and

for an ideal vapor phase, where

Vm is the molar volume,

ρ is the density,

g is the gravitational acceleration,

h is the vertical height,

M is the molar mass, and the subscript L and V denote the liquid phase and the vapor phase, respectively.

III. A generalized Kelvin Equation

When an additional pressure

is applied to a liquid, its vapor pressure increases from

to

, where

VmL is the molar volume of the liquid,

R denotes the universal gas constant, and

T is the temperature [

11]. Let

be the equilibrium vapor pressure above a flat liquid surface under atmospheric pressure

, and

that above a curved liquid surface (curvature

H) under atmospheric pressure

. Due to changes in atmospheric pressure and liquid surface curvature, the liquid experiences an additional pressure as

, where

γ is the surface tension. Using this value for

yields a generalized Kelvin equation:

Given that

, the simplified classical Kelvin equation can be derived:

IV. Equilibrium Between Sessile Droplet and Atmosphere

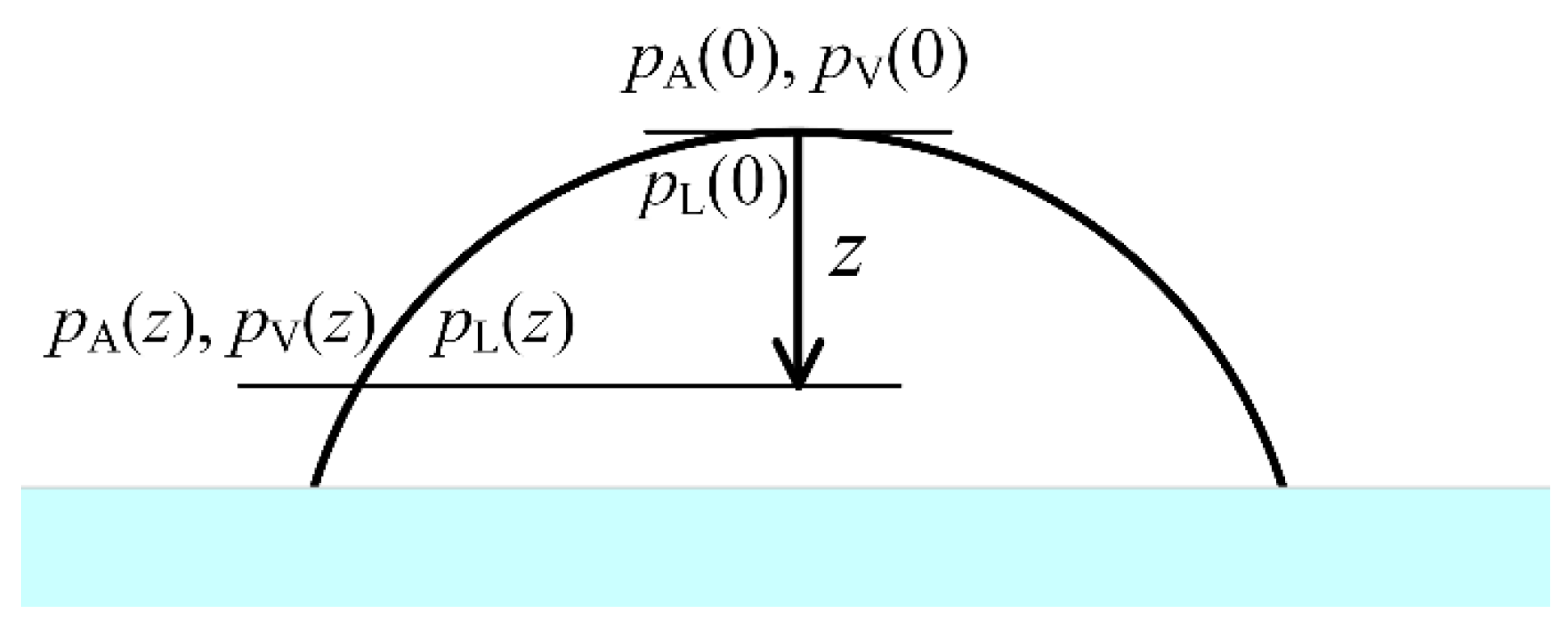

Here, we consider a sessile liquid droplet resting on a flat, horizontal solid surface.

,

, and

are the atmospheric pressure, the vapor pressure, and the liquid pressure, respectively, at the height

z measured downward from the highest point of the droplet (see

Figure 1). To achieve liquid-vapor equilibrium throughout the whole droplet surface in the presence of an arbitrary stationary field due to gravity or an accelerated reference frame, both the mechanical equilibrium and the phase equilibrium should maintain along the droplet surface and inside the two phases.

The mechanical equilibrium in the liquid and in the atmosphere leads to the following relationships:

and

respectively. The mechanical equilibrium across the liquid-gas interface, i.e., the Laplace equation, at heights 0 and

z can be expressed as follows:

and

respectively, where

H(

z) is the curvature of the liquid-vapor interface at height

z. These equations means that, although the gravitational field is irrelevant to Kelvin equation, it can influence the shape of the liquid-vapor interface by altering the pressure fields inside the fluid phases.

The phase equilibrium, i.e., the generalized Kelvin equations, at heights 0 and

z can be expressed as

and

respectively.

Combining the equations (5), (6), (7), and (8) gives

Substituting equations (3) and (4) into equation (9) yields an identity, indicating the self-consistency of the above equations. This means that both mechanical equilibrium and phase equilibrium can be simultaneously satisfied across the entire droplet surface and within both phases. Therefore, a sessile liquid droplet on a flat surface can achieve equilibrium with its surrounding environment in the presence of an arbitrary stationary field due to gravity.

V. Conclusions

In this study, the effects of gravity on liquid-gas systems are analyzed. The results show that, although the gravitational field influences the shape of the liquid-vapor interface by modifying pressure distributions within the fluid phases, it does not affect the phase transition process and therefore need not be included in the Kelvin equation. By accounting for variations in the atmospheric pressure as well as in the liquid surface curvature, a generalized Kelvin equation is derived. Using this generalized Kelvin equation instead of the simplified classical form, it is shown that, in the presence of an arbitrary stationary field due to gravity, both mechanical equilibrium and phase equilibrium between sessile liquid droplets resting on a flat, horizontal solid surface and its environment can be simultaneously satisfied. This result demonstrates that such droplets can indeed attain full equilibrium with their environment even in the presence of gravity.

This study demonstrates that Shanahan’s analysis is formally correct. The incompatibility he derived between mechanical equilibrium and phase equilibrium arises solely from his use of the simplified classical Kelvin equation, rather than the generalized Kelvin equation proposed in this study. The present work demonstrates the theoretical possibility of equilibrium between a sessile droplet and its environment. However, in practice, such equilibrium is difficult to achieve even in a closed system, especially when horizontal liquid surfaces or additional droplets are present. Nevertheless, despite of its simplifications and limitations, the present theory reflects the essential features of the equilibrium between a sessile droplet and its surroundings, and thus provides a theoretical framework for clarifying the behavior of sessile liquid droplets in saturated or high-humidity atmospheres.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52375166).

References

- B. E. Fil, G. Kini, S. Garimella, A review of dropwise condensation: Theory, modeling, experiments, and applications. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer. 2020, 160:120172. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ghalavand, M. S. Hatamipour, A. Rahimi, A review on energy consumption of desalination processes. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 54(6):1526-1541. [CrossRef]

- L. L. Vasiliev, Heat pipes in modern heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2005, 25(1):1-19. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, C. Shi, L. Yang, et al., Investigation of the droplet dynamics and thermal performance during dropwise condensation in the wickless heat pipe condenser. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 2025, 161. [CrossRef]

- L. K. Malla, P. Dhanalakota, P. S. Mahapatra, et al., Thermal and flow characteristics in a flat plate pulsating heat pipe with ethanol-water mixtures: From slug-plug to droplet oscillations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Cioulachtjian, S. Launay, S. Boddaert, et al., Experimental investigation of water drop evaporation under moist air or saturated vapour conditions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2010, 49(6):859-866. [CrossRef]

- Martin E. R. Shanahan, Is a Sessile Drop in an Atmosphere Saturated with Its Vapor Really at Equilibrium? Langmuir. 2002, 18(21):7763-7765. [CrossRef]

- Jacques, Meunier, Daniel et al., Comment on Is a Sessile Drop in an Atmosphere Saturated with Its Vapor Really at Equilibrium? Langmuir. 2003, 19(13):5553–5554. [CrossRef]

- C.D. Volpe, S. Siboni, Comment on ‘Is a Sessile Drop in an Atmosphere Saturated with Its Vapor Really at Equilibrium?’ and Subsequent Criticism. Langmuir. 2006, 22(13):5963-5967. [CrossRef]

- S. Siboni, Determination of the Kelvin equation in the presence of an arbitrary gravitational/inertial field. Am. J. Phys. 2006, 74(7):565-568. [CrossRef]

- P. Atkins, J. D. Paula, J Keeler, Atkins’ Physical Chemistry. (12th edition). Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).