1. Introduction

In 2023, global plastic production reached approximately 413.8 million tons. In this context, 90.4% corresponded to plastics of fossil origin, 8.7% and 0.1% were attributed to post-consumer plastics recycled by mechanical and chemical methods, respectively. A minority corresponds to carbon-captured (0.1%) and plastics of biological origin (0.7%) [

1]. At a global level, the packaging sector is the main consumer of plastics, representing 48% of total production. In this sector, 44.9% of the generated waste is used as an energy source, 37.8% is recycled and 17.3% is not approved, ending in sanitary waste (landfill). Currently, the global production capacity of non-biodegradable organic plastics represents 43.7%, while biodegradables represent 56.3%, where the predominant ones are: polylactic acid (37.1%), compound polymers containing starch (5.7%) and poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (4.6%) [

1]. Compounds based on almonds as a polymeric matrix constitute a great opportunity, due to the fact that this biopolymer is obtained from different renewable vegetable sources, presenting a low cost [

2,

3]. However, it has significant limitations that restrict its application in the handling of packages and containers. Low mechanical resistance, specifically, voltage, as well as thermal stability, limit use in industrial applications. The results are fragile products and not suitable for situations that require a median shelf life (in the range of 6 to 12 months) [

4]. Similarity, properties related to the high hydrophilicity of the starch, attributed to the presence of functional groups of hydroxyl (-OH), allows it to absorb humidity from the environment, negatively affecting its mechanical properties. The former, due to the loss of the initial conformation of the structure, due to the fragmentation of the polymer frames [

5,

6]. This, above all, negatively affects the properties of the barrier, such as permeability to water and gases. Under environmental conditions of light and temperature, the phenomenon of retrogradation of the starch has been extensively studied, in which the molecules reorganize and crystallize over time, increasing fragility and decreasing malleability [

7,

8]. Within the alternatives that science continues to work on, the physical, chemical and biological properties are evaluated to know how to affect the plasticizer content first and then the incorporation of waste [

9,

10]. Considering that the chemical nature of different plasticizers has been studied, glycerol is a great deal with an excellent cost-benefit relationship. Its characteristics such as low volatility and similarity with the structure of starch, allow it to be applied in different blends and compositions with it [

11].

Likewise, it can be applied in the development of films under different industrial processes (extrusion for flat and blown film, injection and thermoforming, among others) [

12,

13]. The above is based on the effectiveness of intermolecular interactions through hydrogen bonds between polyols and starch [

14]. Some authors show results where they relate the synergistic effect between starch, additives and glycerol where an increase in tensile strength is evident, without sacrificing other mechanical properties, on the contrary, generating high stability [

15]. Similarly, Santana and collaborators [

16] demonstrated changes in opacity, permeability and mechanical stability in the plasticity in films based on jackfruit starch dispersions and different glycerol concentrations (20, 30, 40, 50 and 60%). In another work it is shown that the incidence of glycerol at high concentrations (40%) presents repercussions in high water absorption and solubility while the stiffness decreases from 620.79 Mpa to 36.08 Mpa as the glycerol increases from 15 to 45% [

17]. In the second case, the aim is to include nanoclays, which are inorganic compounds whose conformation is based on silicate layers, allowing to improve the mechanical properties and the moisture barrier properties and have been widely studied as reinforcements in thermoplastic starch [

18,

19,

20]. Montmorillonite type nanoclays are the most used due to their easy availability in large quantities in nature [

21,

22]. The development of these composite materials is of great interest, and are currently applied. A recent study allows to know the influence on the degree of exfoliation of the clay layers with respect to the proportion of glycerol in a nanocomposite matrix based on starch [

23]. In this context, the objective of this research was to study the rheological, thermal, mechanical and morphological behavior of a plastic film obtained from cassava starch, reinforced with different proportions of nanoclays and glycerol, under the extrusion and extrusion-blow molding process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The plastic films were made from a mixture of modified tapioca starch, glycerol, and nanoclays. The starch used was supplied by Ingredium, reference N-DULGE® C1, with a moisture content of 11% ± 2%. Glycerol was purchased from Suproquim with a purity of 96%, USP grade. The nanoclay was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, with a density of 600–1100 kg/m3 and an average particle size of less than 25 µm.

2.2. Particle Size Analysis by DLS

The determination of the average size and size distribution of starch and nanoclay was carried out using the DLS technique. A Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments) was used, following the methodology proposed by Abdolbaghi, Pourmahdian, and Saadat [

24] and that of H. J. Huang [

25]. Measurements were performed in triplicate in a 0.1% w/v suspension in distilled water. One mL of suspension was placed in a polystyrene cell with a 90° detection angle at a constant temperature of 25 °C.

2.3. Determination of the Rheometric Conditions of the Mixture

A Thermo Scientific Haake Rheomix OS torque rheometer was used, under process conditions described in previous studies [

26]. Three experimental mixtures of 100 g were proposed, with different proportions of the plasticizer glycerol at 30%, 35%, and 40% relative to starch. Subsequently, nanoclay was added to the selected mixtures (35% and 40%) that allowed the best conformation of the plastic material at 0%, 2%, and 4%. The mixtures were prepared 24 h before being processed in the rheometer and subsequently dried at 60°C for 8 h in a forced convection oven. The nomenclature for labeling the samples is related to the composition, as follows: S-g40-NC0, indicates a sample of starch (S) plasticized with 40% glycerol (g) and 0% nanoclay (NC).

2.4. Production of Thermoplastic Starch (TPS) with Nanoclays and Pelletization

A Thermo Scientific Rheomix twin-screw extruder, operating in counter-rotation and with 10 heating zones in the barrel (see

Table 1), was used. The screw speed was kept constant at 65 rpm during extrusion, and the temperature profile was kept uniform and controlled for all experiments. Dies with a diameter of 10 mm were used. The resulting filaments were cut into 1 mm pieces in a pelletizer. The pellets obtained were dried at 60 °C for 12 h and stored for film production and their characterization.

Table 1.

Proportions of P and NA used to establish process conditions.

Table 1.

Proportions of P and NA used to establish process conditions.

| Sample |

Gly (%) |

Nanoclay (%) |

| 35 |

40 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

| S-g35-NC0 |

x |

|

x |

|

|

| S-g35-NC2 |

x |

|

|

x |

|

| S-g35-NC4 |

x |

|

|

|

x |

| S-g40-NC0 |

|

x |

x |

|

|

| S-g40-NC2 |

|

x |

|

x |

|

| S-g40-NC4 |

|

x |

|

|

x |

Table 2.

Temperature profile of the drum during extrusion.

Table 2.

Temperature profile of the drum during extrusion.

TS1

(°C) |

TS2

(°C) |

TS3

(°C) |

TS4

(°C) |

TS5

(°C) |

TS6

(°C) |

TS7

(°C) |

TS8

(°C) |

TS9

(°C) |

TS10

(°C) |

TS-D1

(°C) |

| 70 |

70 |

70 |

75 |

80 |

85 |

90 |

95 |

100 |

105 |

110 |

2.5. Production of Blown Plastic Films

The bionanocomposite films of starch and clay were manufactured on a Collin E20 blown film extrusion line (Germany). It is equipped with a 20 mm diameter extruder and a length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio of 25. The temperature profile in the extruder was previously determined based on bubble formation above the annular nozzle that injects air. The temperature was maintained at 130 °C and a screw speed of 60 rpm. A tubular or blown film was obtained, which was immediately air-cooled. Finally, the films were stored for subsequent testing in a DIES climate chamber at 40 °C and 35% relative humidity.

2.6. Characterization

2.6.1. FTIR Analysis

The infrared spectra of the starch and nanoclay samples were analyzed according to the methodology established in ASTM E1252. A Perkin Elmer Spectrum 3 spectrophotometer was used, ranging in wavelength from 400 cm−1 to 4000 cm−1, in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode.

2.6.2. Rheological analysis

Rheological analysis was carried out following the methodology proposed by Caicedo et al. [

24] with the aim of evaluating the storage and loss moduli. This analysis was performed on both the obtained films and the TPS as a reference. For the test, TPS pellets were used and, in the case of the films, smooth circular samples with a diameter of 25 mm and a thickness of 1 mm were taken. Measurements were carried out on a TA Instruments HR2 rotational rheometer, using a 25 mm parallel plate geometry and a GAP of 1000 μm, under angular frequency conditions of 0.1 rad/s to 628 rad/s, with 5 points per decade, and a test temperature of 170 °C.

2.6.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

A TA Instruments Q50 instrument was used to obtain TGA thermograms of the starch and nanoclay samples, primarily to identify the temperatures at which weight losses due to degradation occur. Samples weighing ±5 mg were placed in sealed alumina cells and heated. The temperature range studied was 25°C to 800°C at a rate of 10°C/min and a nitrogen purge flow rate of 60 mL/min.

2.6.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis

The DSC thermal characterization of the starch and nanoclay bionanocomposites was performed using a TA Instruments Q2000 model. This analysis allowed determining the melting temperatures. The samples were analyzed under a nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 20°C/min. The ASTM D3418 heating procedure was followed with an initial temperature of 20°C and a final temperature of 230 °C, using the theoretical thermal transition temperature of starch as the starting point for the heating program.

2.6.5. Determination of Tensile Strength and Strain

Tensile and elongation tests were performed according to ASTM D882. Sections of the different films obtained were prepared, measuring 10 cm x 2.5 cm. The samples were conditioned in a climate chamber at 40 °C and 35% relative humidity for 4 hours before testing. A calibrated length of 50 mm was drawn from each sample. The thickness was then measured at three different points to obtain an average value, which was entered into the corresponding software to begin the test. The method conditions were previously set to a speed of 12.5 mm/min and a calibrated clamping length of 50 mm. The test consisted of recording the deformation of the material until reaching its breaking point. The tests were performed on an INSTRON universal testing machine with a capacity of 50 kN.

2.6.6. Determination of Tear Strength

The test was carried out according to ASTM D1922-08. Initially, 10 replicates of each film sample were prepared, each measuring 76 mm long and 63 mm wide. The thickness of each sample was measured three times at the center. Two points were marked on each sample, 9.5 mm from the center at the top. With the pendulum in the raised position, the specimens were placed in the testing equipment, and the jaws were adjusted to ensure proper grip. Subsequently, a 20 mm long notch was made in each specimen. Using the knife actuating lever, the pendulum was released to perform the test. Finally, the percentage of the scale value was recorded, and the tear strength (Rr) was calculated in kilograms, applying Equation 1.

Rr= pxm/100xn Eq. 1.

Where: p: Scale reading [%], m: Pendulum mass [g] and n: Number of specimens.

2.6.7. SEM Microscopy

Morphological analysis of the starch and nanoclay samples was performed using a JEOL Model JSM-6490 scanning electron microscope (SEM), Japan. The samples were coated with a gold nanolayer (5 nm thick). This was done using a Cressington 108 Auto Sputter Coater (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA). Micrographs were obtained at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV in a high vacuum.

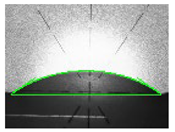

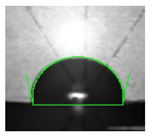

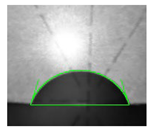

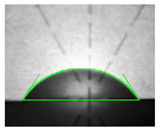

2.6.8. Contact Angle

For the test, the sessile drop analysis method was applied using distilled water as a solvent to study the hydrophobicity of the materials. A ST INDUSTRIES model 20-3500 profiler was used. Initially, each 1 cm x 1 cm film was cut into 10 replicates, and 10 μL of water at 25 °C was added using a micropipette. Photographic recordings were taken at 0 s, 10 s, and 60 s. The contact angle was determined using Image J software.

2.6.9. Determination of Water Vapor Permeability

Water vapor permeability was determined using the ASTM F1249-20 methodology using a PERMATRAN model 3/33 water vapor permeability meter. Sections of approximately 101.6 mm in diameter were cut from the film. The thickness was initially measured at three different points in the exposure area and then transferred to the cell, which has an exposure area of 5 cm2. All tests were performed under temperature and relative humidity conditions of 37.8 °C and 90%, respectively. Data were recorded every 30 minutes.

2.6.10. Statistical Analysis

All test results were analyzed statistically using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test to identify significant differences in results at α = 0.05 using Minitab 22.0 software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Analysis

Clay size analysis using DLS identified two main peaks: peak 1, centered at 479.3 nm, with a volume of 58.0%, and peak 2, at 108.3 nm, with a volume of 42.0%. These results reveal a bimodal particle size distribution, with a significant fraction in the nanometer range. The average size is 587.6 nm, and the polydispersity index (PDI) of 1.0 indicates high heterogeneity in the size distribution. The 58% volume in peak 1 may be related to the formation of lamellar nanoclay agglomerates, which occur due to inefficient dispersion in the ethanolic solution. This lack of dispersion is attributed to the forces of attraction between the particles due to Van der Waals bonds. This phenomenon is also reflected in the high PDI value, which confirms an inhomogeneous size distribution. Despite this, the presence of clay particles on the nanometer scale is observed [

27].

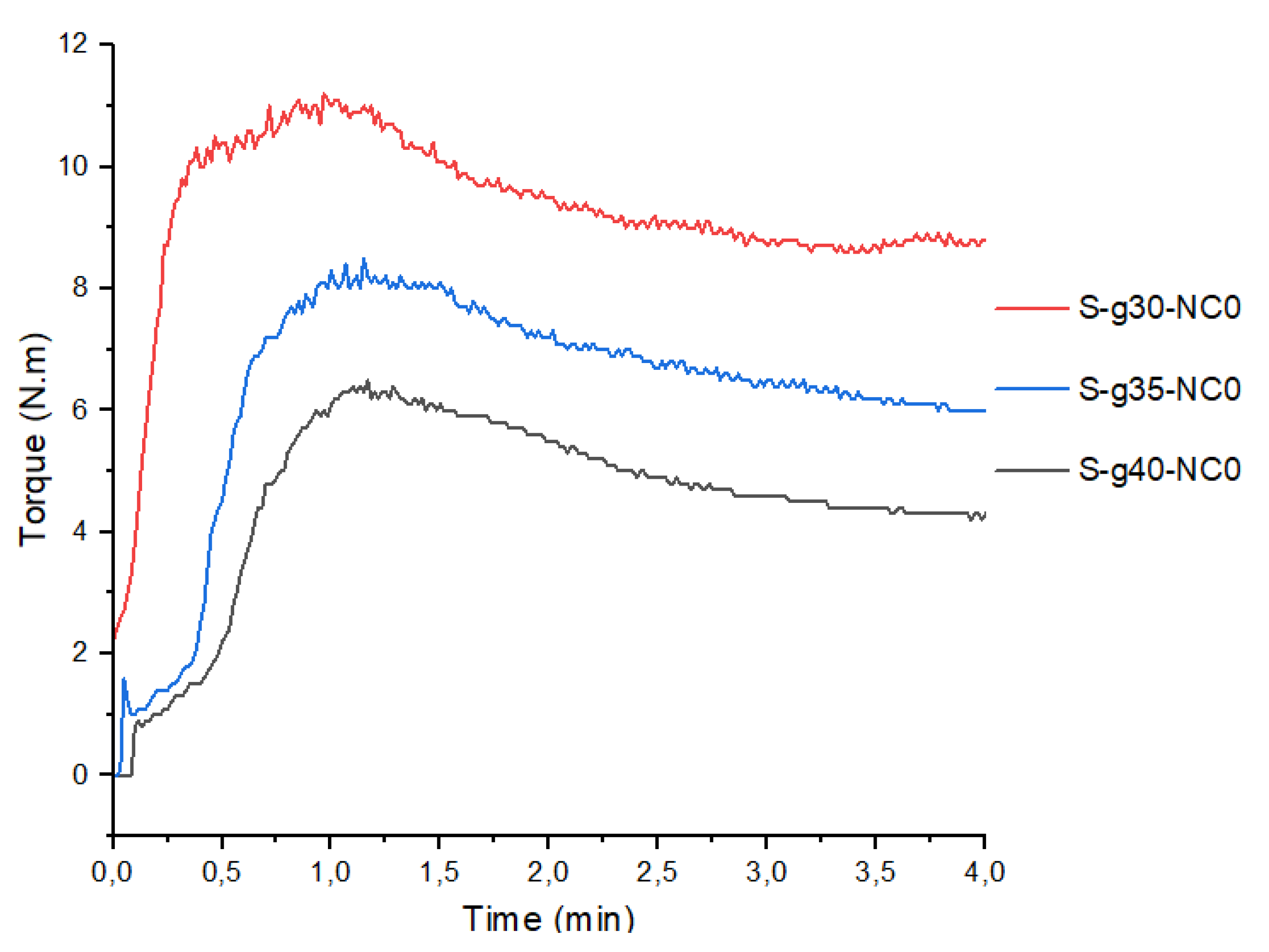

3.2. Torque Rheometry

Figure 1 shows the torque as a response variable as a function of starch mixing time and different glycerol proportions. The rheometric profile revealed a typical Gaussian-like plasticization process, with a rapid increase in torque (in the first 15 s), reaching maximum torques of 11.2 Nm, 8.5 Nm, and 6.5 Nm for the mixtures with 30%, 35%, and 40% glycerol, respectively. The mixture then absorbs enough heat to achieve fusion, and with the action of the plasticizer, the torque drops until stabilization is reached. The values obtained at torque stabilization are 9.8 Nm, 6.2 Nm, and 4.5 Nm for the mixtures with 30%, 35%, and 40% glycerol, respectively.

Therefore, bionanocomposite mixtures that allow a more efficient plasticization in terms of energy consumption and conformation of a viscoelastic mass are selected. The measured values show that the increase in the plasticizer content generates a decrease in torque. The development phase of bionanocomposites pellets in the extrusion equipment continues. The sample with 30% plasticizer is excluded because it presents high process energies, a rigid and fragile texture at the end of the mixing process.

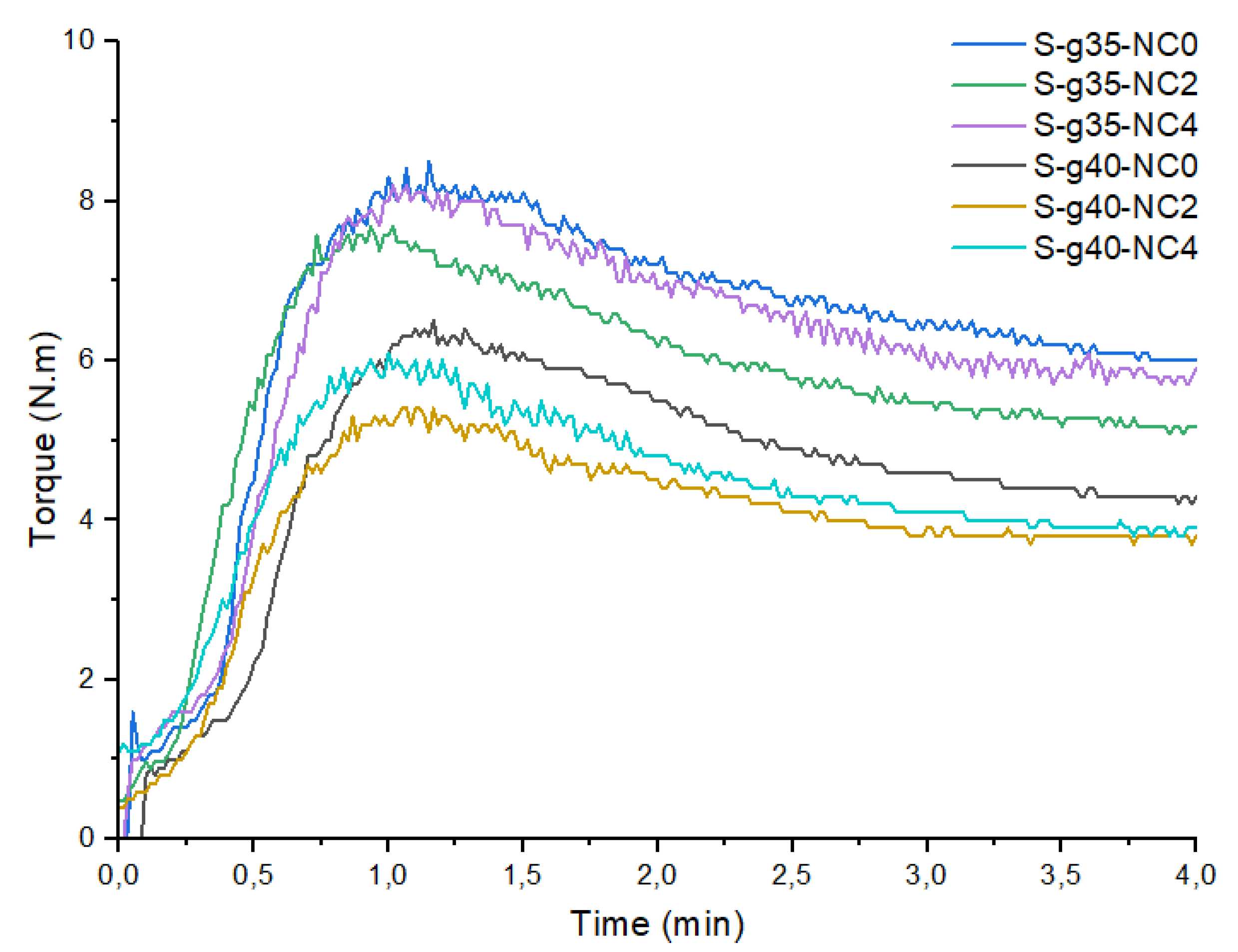

Table 3 shows the results of the maximum torque of the bionanocomposites. These mixtures allow to demonstrate a minimization (≤0.4 N.m) in the torque with the incorporation of nanoclays that facilitate the plasticization process as discussed in previous works [

28]. The decrease in torque indicates a lower viscosity and low resistance to flow during processing. It is important to mention that the conformation of the material was also considered for the selection. In the sample with 40% plasticizer, an excess of the plasticizer can be seen as segregated (see

Figure 2).

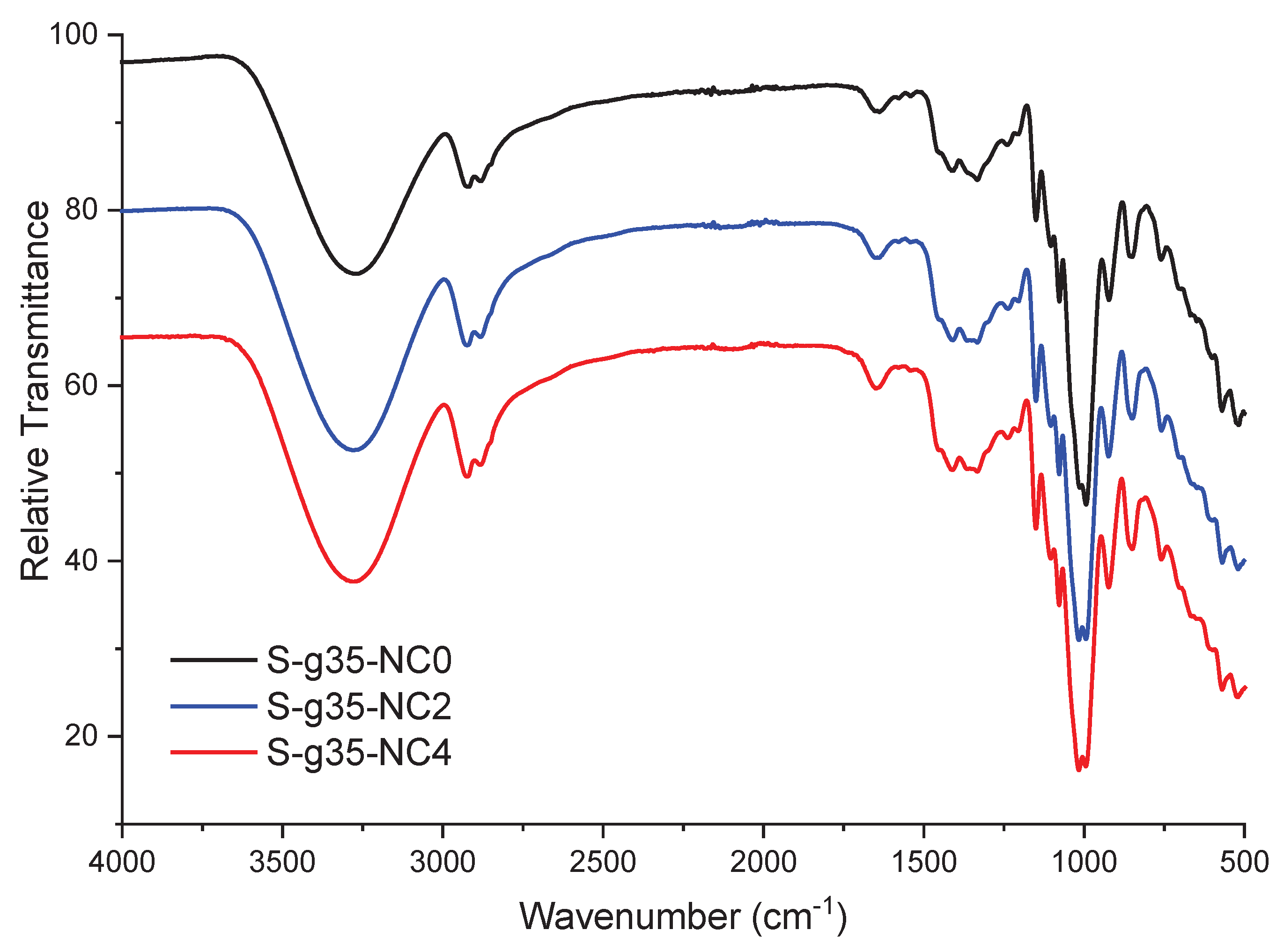

3.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

Figure 3 presents the FTIR spectra of native starch, nanoclays, and glycerol. The starch spectrum presents bands around 3275 cm

−1 corresponding to the vibrations of the hydroxyl functional group (-OH). The bands around 2928 cm

−1 - 2885 cm

−1 are associated with the elongation vibrations of the C-H functional group corresponding to the methylene group (CH

2). The bands at 1636 cm

−1 are related to the bending vibration of absorbed water (H-O-H), which is typical in hygroscopic materials such as starch. The bands at 1458 cm

−1 to 1417 cm

−1 are associated with bending vibrations of the C-H groups and strain vibrations of the C-O group in the glucose rings forming starch, 1336 cm

−1 and 1240 cm

−1 are related to strain vibrations of C-H and C-O groups, respectively. The bands in the region 1150, 1075 and 998 cm

−1 correspond to stretching vibrations of the C-O-C bonds in the starch backbone as well as to vibrations of the C-O bonds in the hydroxyl groups. Finally, the bands in the regions 925 cm

−1 and 858 cm

−1 are associated with vibrations of typical glucose rings in polysaccharides [

29,

30].

The nanoclay spectrum shows some bands in the low-energy region around 3612 cm

−1 and in the broad range between 3500 and 3300 cm

−1, corresponding to the O-H vibrations of the hydroxyl groups present, which are vibrations associated with Al-OH and Si-OH [

31]. This is due to the layered structure of the nanoclay, where tetrahedral sheets of silica are bonded to an octahedral sheet of alumina [

32]. The band at 1631 cm

−1 is attributed to the bending vibrations of water molecules, indicating the presence of moisture in the nanoclay. A pronounced band is also detected at 981 cm

−1, related to the stretching of the Si−O bonds in the tetrahedral layer. The band at 1105 cm

−1 is associated with the Si-O-Si and Al-O-Si vibrations characteristic of clay structures. Finally, the regions between 912 cm

−1 and 840 cm

−1, and at 550 cm

−1, are assigned to the Al−Al−OH and Si−O−Al vibrations, respectively, characteristic of nanoclays.

On the other hand, the FTIR spectrum of glycerol shows a band in the 3276 cm

−1 region attributed to the stretching vibrations of the hydroxyl groups (–OH). Since glycerol has three hydroxyl groups, this band is intense and wide, which also reflects the presence of hydrogen bonds, since glycerol can form multiple bonds both between its own molecules and with water. The bands in the 2937 cm

−1 to 2879 cm

−1 region correspond to the stretching vibrations of the C–H bonds in the methylene (–CH

2) and methyl (–CH

3) groups present in the glycerol structure. The band at 1412 cm

−1 is related to the bending vibrations of the –OH group and to the deformation vibrations of the C–H bonds. The bands in the range of 1329 cm

−1 to 1219 cm

−1 are associated with bending vibrations of the C–H bonds and deformation of the hydroxyl (–OH) groups. The bands at 1106 cm

−1 to 1030 cm

−1 are characteristic of stretching vibrations of the C–O bond in the –OH group of glycerol, indicating the presence of primary and secondary alcohols [

33]. Finally, the bands in the region of 990 cm

−1 to 851 cm

−1 are associated with the structure and deformations of the glycerol carbon skeleton.

The FTIR spectral curves of the bionanocomposite film show similar bands for all samples. These include the band in the range 3200 cm

−1 to 3600 cm

−1 attributed to stretching vibrations of hydroxyl (-OH) groups, indicating the presence of hydrogen bonds in the starch chains and the plasticizer. In the region 2800 cm

−1 to 3000 cm

−1, bands corresponding to stretching vibrations of C-H bonds are observed. These are present in the glucose units of starch and other components of the thermoplastic matrix. The band at 1600 cm

−1 is associated with stretching vibrations of the C=O group, common in carboxyl or carbonyl groups within the matrix. A band in the range 1020 cm

−1 to 1080 cm

−1 is related to C-O-C stretching vibrations and glycosidic bonds, confirming the polymeric structure of starch. Furthermore, this band is associated with the Si-O and Si-O-Si bonds of the nanoclays. It is important to note that the bands at 2800 cm

−1 and 2900 cm

−1 in S-g35-NC2 are more intense compared to S-g35-NC4 [

27,

31]. According to information provided by C. M. O. Müller, J. B. Laurindo, and F. Yamashita [

32], this behavior may be due to a lack of plasticization of the starch and a non-uniform dispersion of the nanoclays on the starch surface.

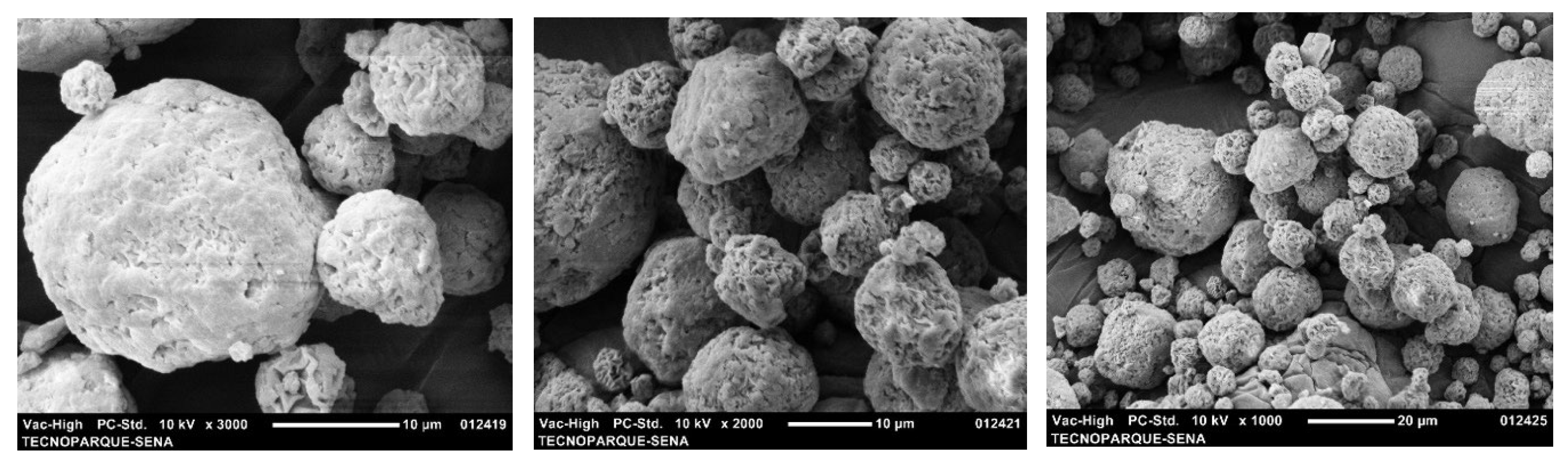

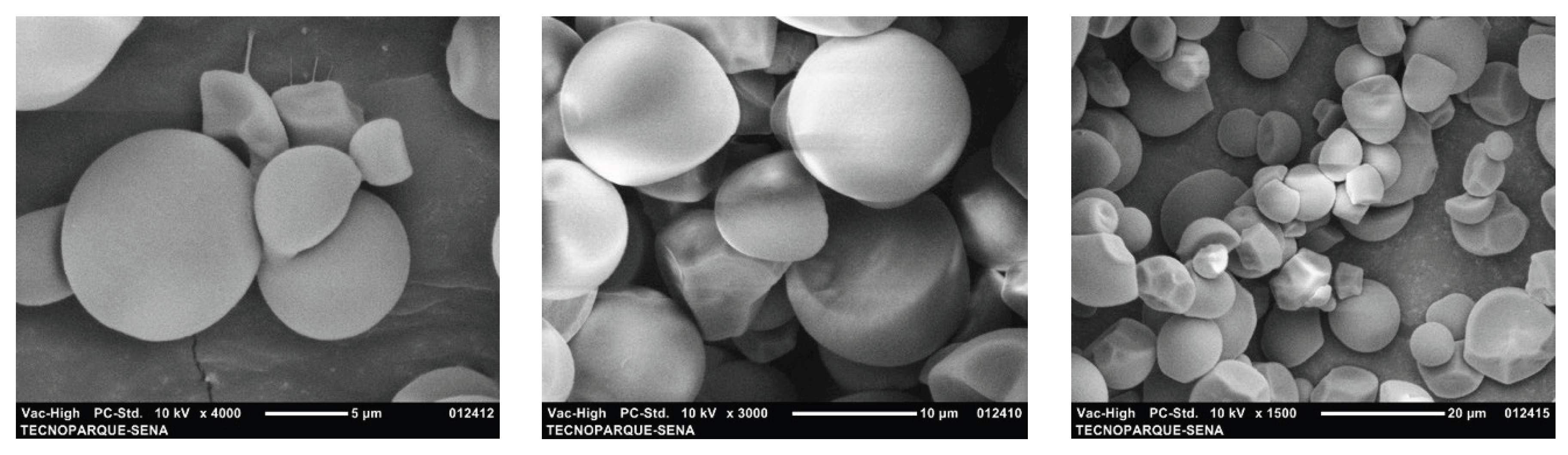

3.4. SEM Microscopy of Nanoclays and Starch

Figure 4 shows micrographs of the nanoclays. Two populations of pseudospherical aggregates with irregular edges are observed. These results are consistent with those reported by K. Moreno-Sader, A. García-Padilla, A. Realpe, M. Acevedo-Morantes, and J. B. P. Soares [

20], who found spherical shapes with some wavy network fringes on the surface of the same clay species. Additionally, aggregates of irregular spherical particles with average diameters of ~15 µm and ~29 µm are observed. Other researchers report that nanoclays have surfaces with pores, interstices or cavities, which are morphological characteristics of montmorillonite-type nanoclays.

SEM micrographs of cassava starch are shown in

Figure 5. The starch granules mostly have a spherical morphology. Some granules have irregular shapes. Regarding the surface of the granules, most are smooth and some are rough with a granule diameter size between 7 µm and 15 µm. These results are consistent with those of L. Franco, M. Soares, S. Ju, and M. C. Garcia [

17], F. Zhu [

18] and finally those of M. Enriquez, R. Velasco, and A. Fernandez [

22] who reported that the morphology of native cassava starch granules is spherical with a size between 5 µm and 17 µm.

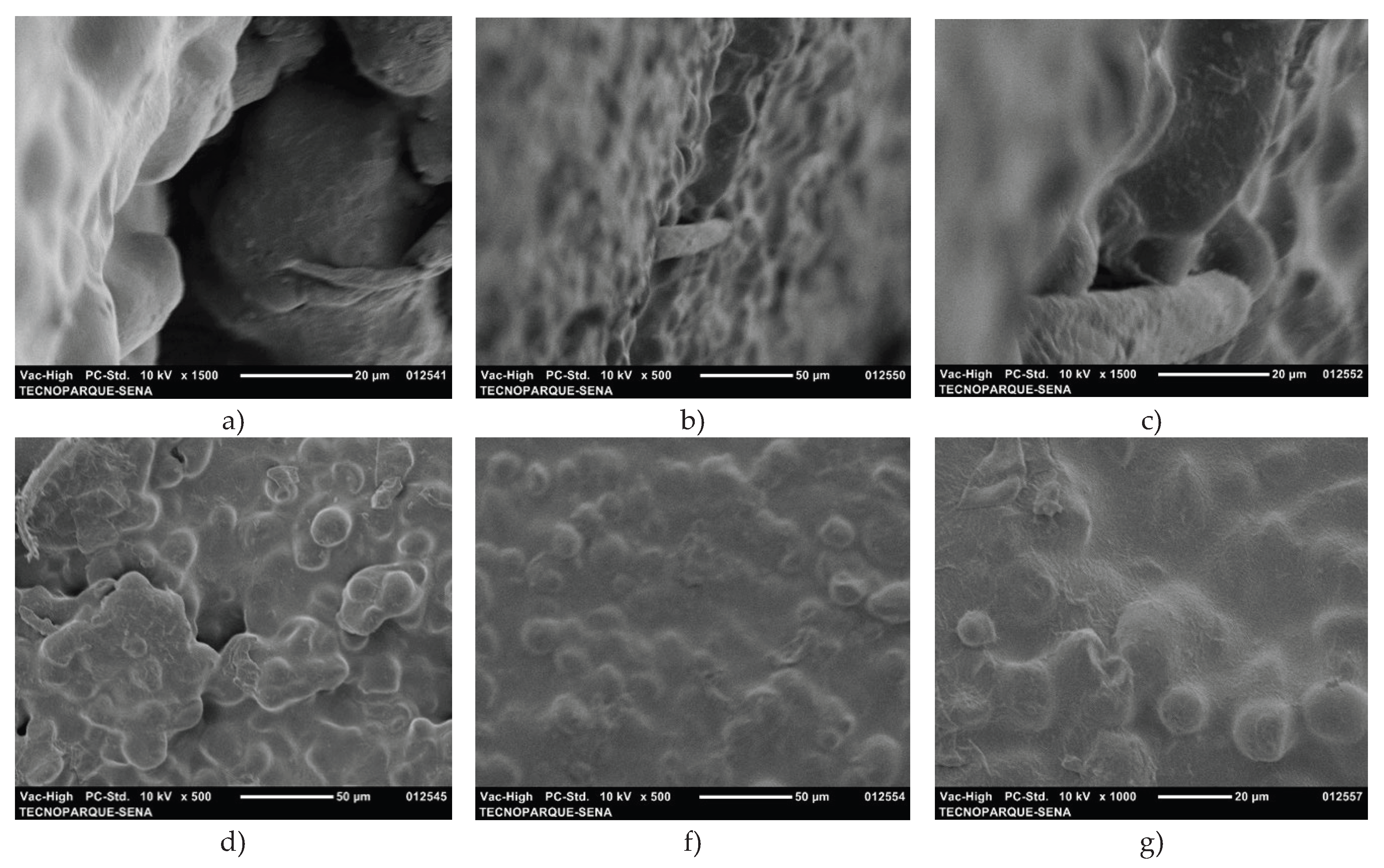

Figure 6 shows SEM micrographs of the F-g35-NC0, F-g35-NC2, and F-g35-NC4 films, with the cross and vertical sections of each film obtained.

In general, the SEM micrographs of the films do not show fractures or phase separation. However, when comparing the micrographs in

Figure 6(d-f), it is observed that the P-g35-NC0 film exhibits cracks and agglomerations compared to F-g35-NC2 and F-g35-NC4. The presence of small aggregates or lumps in some areas could indicate incomplete dispersion of the starch during the mixing process. Although these defects are minor, they could act as points of weakness under mechanical stress or thermal fluctuations, affecting the long-term integrity of the material. The porosities and defects visible on the surface suggest that the mixture may have limited barrier properties, which would affect its performance in applications requiring resistance to the passage of gases or liquids [

30,

32]. The surface of the F-g35-NC2 film is rough and presents prominent aggregates, indicating incomplete or inadequate dispersion of the materials, possibly due to components that were not adequately integrated into the matrix. In contrast, F-g35-NC4 presents a smoother surface with few visible imperfections, indicating excellent interaction between the clay layers and the polymer matrix. This improved integration translates into better mechanical properties and thermal stability [

30]. The uniformity of F-g35-NC4 improves its barrier properties, reducing porosity and increasing the material’s mechanical strength. Furthermore, a lower number of surface defects implies better performance in applications requiring high resistance to the passage of gases or liquids.

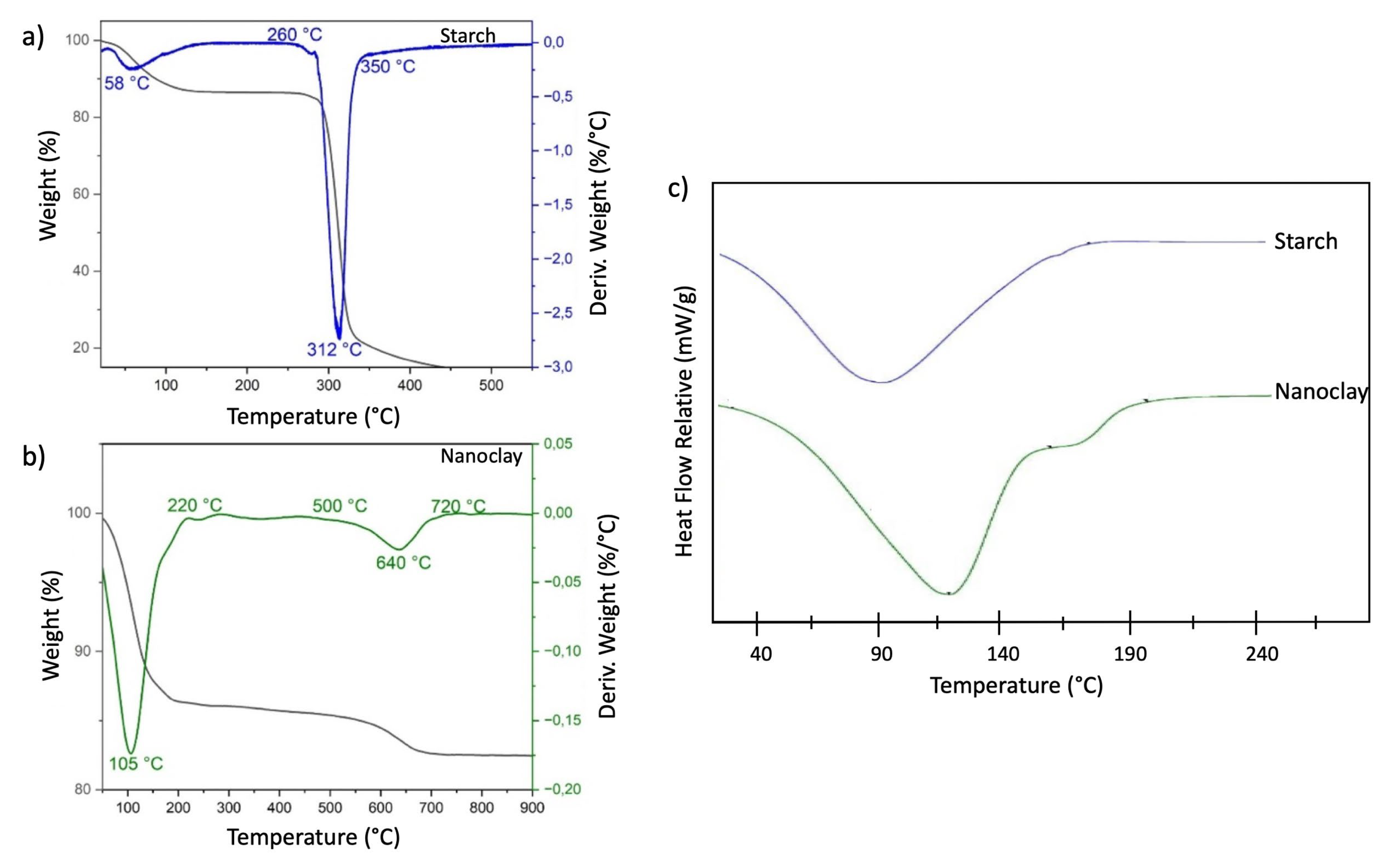

3.5. DSC and TGA Analysis

Figure 7 presents the TGA thermograms and their respective derivatives for starch (

Figure 7a) and nanoclays (

Figure 7b). Two main stages of weight loss are observed in the TGA derivative of starch. The first, around 58 °C, corresponds to a small initial loss attributed to the removal of surface or adsorbed water, which is characteristic of hygroscopic materials. The second stage, between 260 °C and 350 °C, shows a maximum peak at 312 °C, indicating the thermal decomposition of starch. At this stage, the polysaccharide chains are broken, resulting in rapid and significant weight loss, typical of the primary decomposition of starch due to heat. These results are consistent with those reported by X. Chen [

23], who observed a degradation temperature of 319 °C for native cassava starch.

In the TGA derivative of nanoclay, a significant weight loss is observed around 105 °C, corresponding to the elimination of adsorbed water on the surface of the nanoclay. This behavior is similar to that reported by Qin et al., who identified a notable loss around 120 °C in three samples analyzed between 500 °C and 720 °C. A second stage of weight loss is evident, associated with the decomposition of the nanoclay structure and the elimination of functional groups on its surface, mainly hydroxyl groups, a phenomenon known as dehydroxylation of the structural water present in the clay [

24,

25].

Figure 7 presents the DSC curves obtained for the starch and nanoclay (

Figure 7c) samples. The starch thermogram shows an endothermic peak with a maximum temperature of 94 °C, corresponding to its melting point. At this point, the starch absorbs heat and undergoes a gelatinization process, causing the loss of crystalline structures in the starch granules [

17,

18]. The DSC thermogram of the nanoclay shows an endothermic peak associated with the desorption of surface water or water physically adsorbed on its surface. This is a common phenomenon in materials with a high specific surface area. It occurs at a temperature of 115 °C, attributed to the elimination of interlaminar water, that is, water found between the layers of the nanoclay. At 173°C, another endothermic peak corresponds to the elimination of organic molecules or volatile contaminants trapped in the nanoclay structure, and is accompanied by a slight structural change due to thermal energy. In addition, partial dehydroxylation of the nanoclay could occur, a process in which the hydroxyl groups present in the structure are eliminated as the temperature increases [

26].

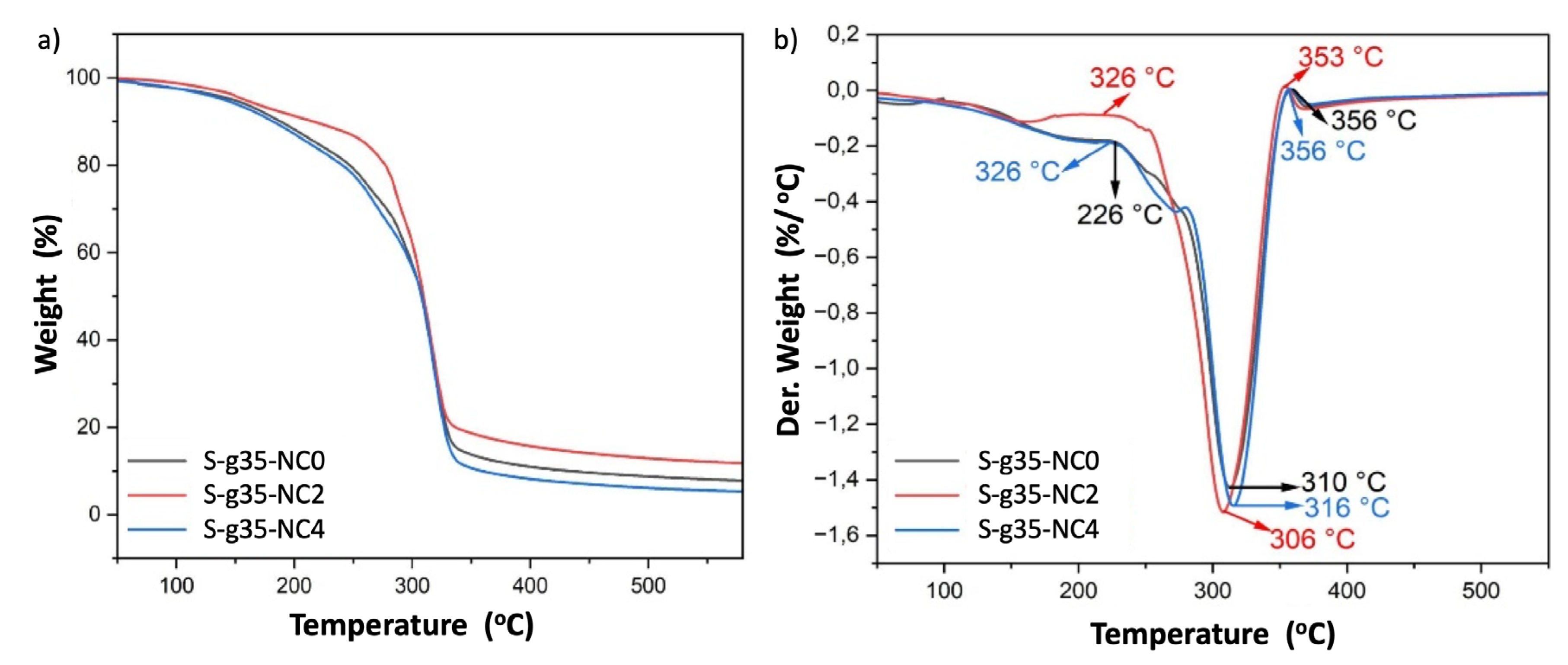

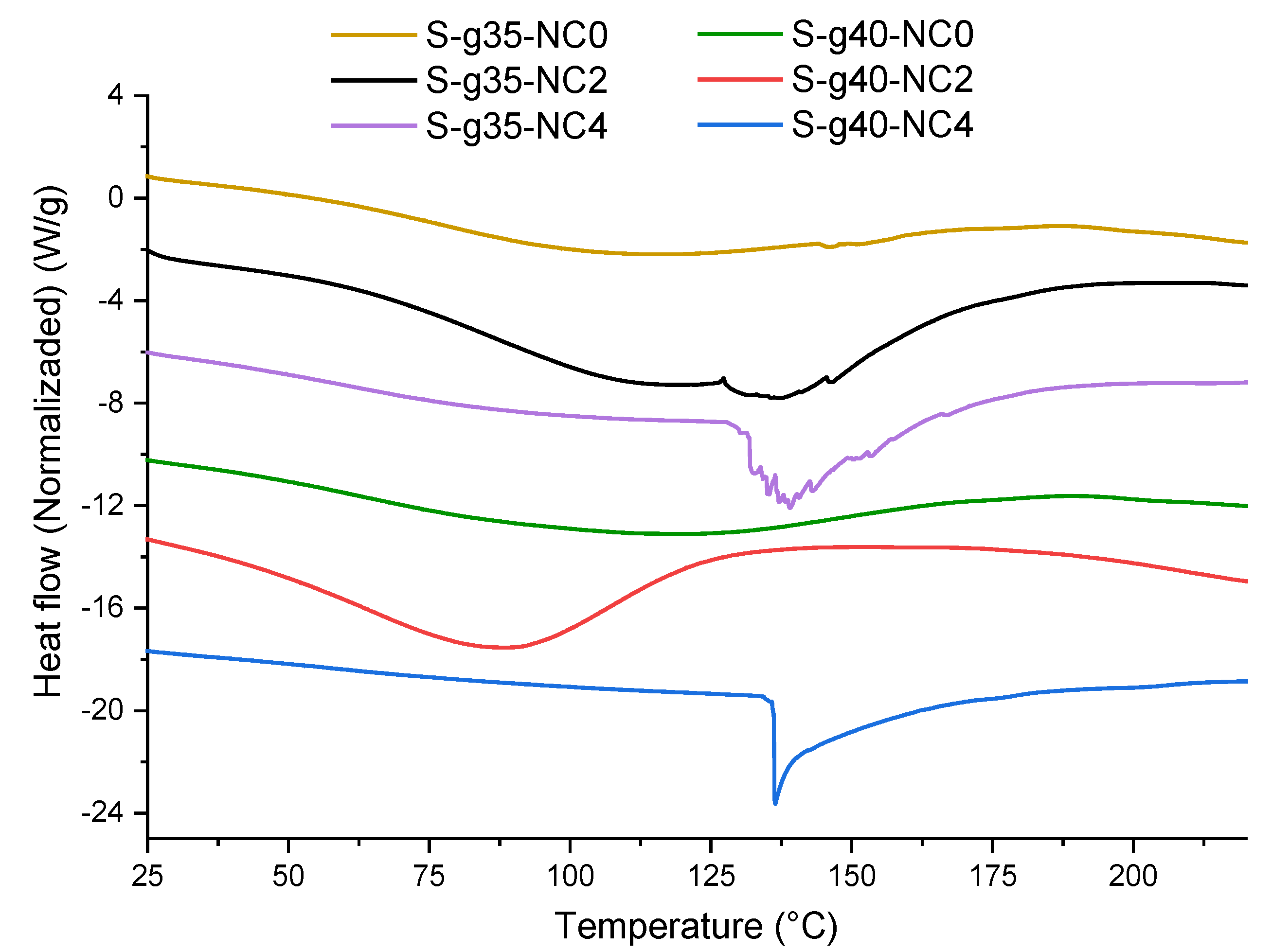

3.6. Characterization of Thermoplastic Starch (TPS) by DSC and TGA

Figure 8 presents the TGA thermograms (

Figure 8a) and their respective derivatives (

Figure 8b) for thermoplastic starch with 35% plasticizer, thermoplastic starch without nanoclays (S-g35-NC0), with 2% nanoclays (S-g35-NC2), and with 4% nanoclays (S-g35-NC4), obtained after the extrusion process. In

Figure 9(b), an initial mass loss is observed between 25°C and 150°C in all samples, associated with the evaporation of surface and adsorbed water, as well as with the interaction of the plasticizer and the nanoclays. The second mass loss corresponds to the thermal decomposition of the starch and nanoclay structures. The maximum degradation temperature of TPS was 310 °C, very similar to that of native starch (312 °C). In the case of S-g35-NC2, this temperature decreased slightly to 306 °C. However, in S-g35-NC4, the degradation temperature increased to 316 °C. This increase indicates that the addition of 4% nanoclays improves the thermal resistance of the material, due to several factors. The interaction between the nanoclays and the polymer matrix, which acts as a thermal barrier. The high degree of dispersion of the nanoclays within the matrix. The formation of interactions between the functional groups of the nanoclays and the starch, which increases the cohesion of the material. And, the fact that nanoclays, being inorganic materials, have a higher decomposition temperature [

30]. Furthermore, their uniform distribution facilitates better heat dissipation within the matrix, which contributes to delaying thermal decomposition processes [

31].

In

Figure 9, the TPS exhibits an endothermic peak at 113 °C, corresponding to the melting temperature of the matrix. This relatively low temperature indicates that the unreinforced matrix has lower thermal stability. In the S-g35-NC2 sample, an endothermic peak is observed at 138 °C. This reflects a significant increase in the thermal transition temperature compared to the TPS. The incorporation of 2% nanoclays improves the thermal stability of the starch matrix, likely due to the interaction between the nanoclays and the starch, which generates a network more resistant to temperature variations. Finally, S-g35-NC4 also shows an endothermic peak at 138 °C, similar to S-g35-NC2. This suggests that the addition of nanoclays up to 4% does not significantly increase the thermal transition temperature beyond that observed with 2%, which could indicate that the thermal boosting effect of nanoclays reaches a limit above this concentration [

31].

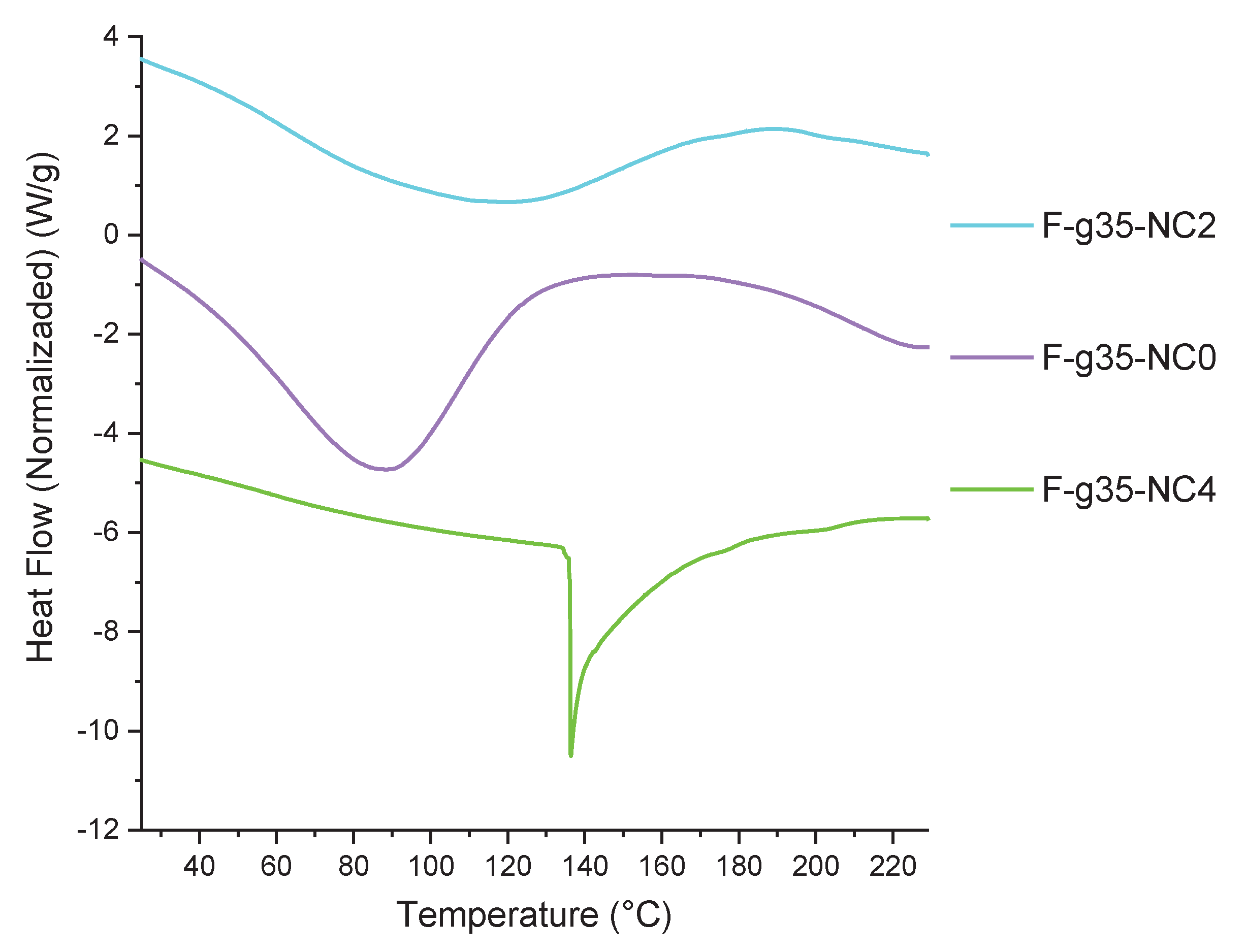

3.7. DSC Thermograms of the Films

Figure 10 presents the DSC thermograms for the bionanocomposite films. Sample F-g35-NC0 exhibits an endothermic peak at 88 °C, corresponding to the melting temperature of the film-forming mixture. Sample F-g35-NC2 exhibits an endothermic peak around 120 °C, indicating a higher thermal transition temperature compared to sample F-g35-NC0. The presence of nanoclays raises the melting temperature due to the interaction between the starch matrix and the nanoclays, which limits molecular motion and improves the material’s thermal resistance. Sample F-g35-NC4 presents an endothermic peak at 136 °C, the highest of the three samples, suggesting that increasing the nanoclay content significantly improves the thermal stability of the material. This behavior indicates that a higher amount of nanoclay reinforces the film structure, further limiting the movement of the polymer chains. Similar results were reported by E. Gil and M. Mesa [

33], who found that the addition of nanoclay improved the thermal stability and reduced starch recrystallization. An important aspect to highlight is that in sample F-g3-NC4, the melting range is lower compared to samples F-g35-NC0 and F-g35-NC2, reflected in a sharper peak. This behavior can be attributed to a higher degree of molecular ordering in the sample and to a strong interaction between the nanoclays and the starch, generating a thermal insulation effect that contributes to a higher stability of the material [

30].

Sample F-g35-NC0 exhibits an endothermic peak at 88 °C, corresponding to the melting temperature of the film-forming mixture. Sample F-g35-NC2 exhibits an endothermic peak around 120 °C, indicating a higher thermal transition temperature compared to sample F-g35-NC0. The presence of nanoclays raises the melting temperature due to the interaction between the starch matrix and the nanoclays, limiting molecular motion and improving the material’s thermal stability. Sample F-g35-NC4 exhibits an endothermic peak at 136 °C, the highest of the three samples, suggesting that increasing the nanoclay content significantly improves the material’s thermal stability. This behavior indicates that a higher amount of nanoclay reinforces the film structure, further limiting the movement of the polymer chains. Similar results were reported by E. Gil and M. Mesa [

33], who found that the addition of nanoclay improved thermal stability and reduced starch recrystallization. An important aspect to highlight is that in sample F-g35-NC4, the melting range is lower compared to samples F-g35-NC0 and F-g35-NC2, reflected in a sharper peak. This behavior can be attributed to a greater degree of molecular ordering in the sample and a strong interaction between the nanoclays and starch, generating a thermal insulation effect that contributes to greater material stability [

30].

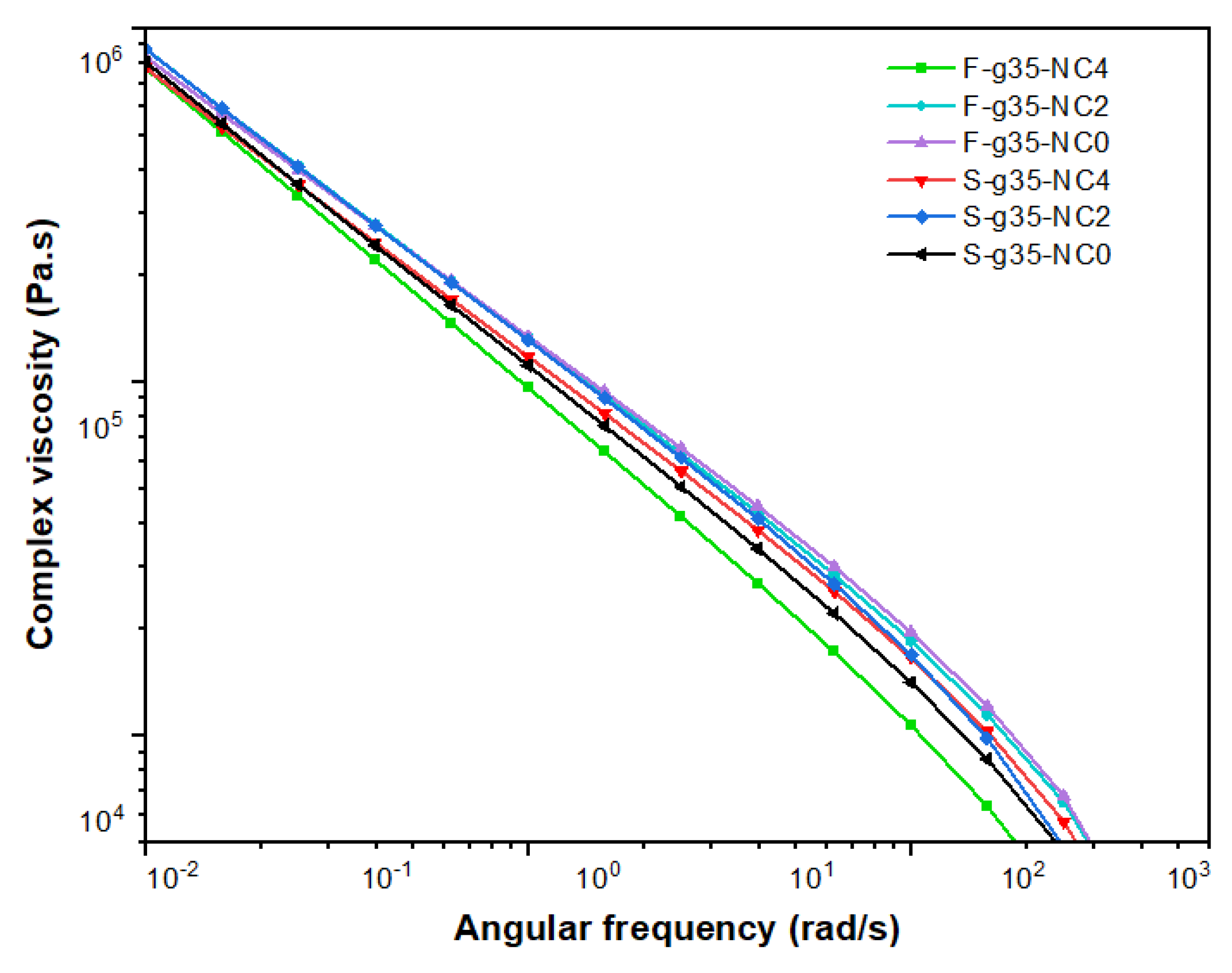

3.8. Rheological Analysis of the TPS and the Obtained Films

Dynamic rheological properties are useful as indicators of the thermoplastic state of the extruded bionanocomposite samples (S-g35-NC) and their respective films (F-g35-NC).

Figure 11 shows the complex viscosity and storage modulus of these samples at different shear frequencies. In the low-frequency range, the interaction between the entanglement of the molecular chains significantly affects the complex viscosity and storage modulus, providing insight into the processing effect on the samples. [

34]

Thus, at an angular frequency of 100 rad/s, a significant increase in the storage modulus was observed for all bionanacocomposites. This behavior has been observed in cassava starch samples due to the formation of an elastic network structure, which is generated when the material is subjected to external stresses. Furthermore, the addition of clay reduces the viscosity of the composite as observed in

Figure 11 for S-g35-NC4 and F-g35-NC4, which makes the deformation of the TPS secondary phase more significant under heating conditions during processing [

35]. Furthermore, Figure 12 shows that the storage modulus and complex viscosity of TPS only show slight changes with increasing speed. This suggests that the molecular weight of TPS produced at different speeds remains relatively constant. In other words, the effect of elongational rheology contributes positively to the conservation of the molecular weight of TPS, while ensuring an adequate plasticization state of the materials [

36].

3.9. Contact Angle

Table 4 presents the contact angle results of the films and the ANOVA between the films for each time (0, 10, and 60 s). It is evident that for time 0 s, the F-g35-NC0 film has the lowest contact angle (52.00° ± 1.37) and is significantly different compared to F-g35-NC2 (73.90° ± 3.22) and 4% (89.93° ± 8.78). The addition of nanoclays generates a more hydrophobic surface at both concentrations. The results show that the contact angle was higher at all times for sample F-g35-NC4, showing significant differences compared to sample PB at 10 and 60 seconds. According to the information reported by G. Giridhar, R. K. N. R. Manepalli, and G. Apparao [

37], contact angle values less than 90° are considered indicative of hydrophilic surfaces. However, as pointed out by T. Gutierrez, R. Ollier, and V. Alvarez [

38], the classification as hydrophobic or hydrophilic may vary depending on the application of the material (such as packaging, coating, or in biomedical applications). In composite materials, contact angles between 50° and 90° are considered slightly hydrophobic. Therefore, the contact angle values above 65°, obtained for the films with 2% and 4% nanoclay content evaluated in this work, can be considered hydrophobic surfaces. For times of 10 s and 60 s, no significant differences were observed between the treatments.

3.10. Determination of Mechanical and Barrier Properties

Table 5 presents the results for thickness, tensile strength, strain, water vapor transmission rate, and tear strength of the films obtained. The thickness results show that the F-g35-NC0 film (0.11 ± 0.03 mm) is smaller and presents a significant difference compared to the F-g35-NC2 (0.78 ± 0.12 mm) and F-g35-NC4 (0.71 ± 0.07 mm) films. This suggests that the addition of nanoclays increases the thickness of the films, indicating that nanofillers not only alter the physical properties of the films but can also influence their functionality in specific applications [

39]. In this sense, thickness could be a crucial factor for the material’s effectiveness and performance in packaging applications.

The tensile strength results show that the F-g35-NC0 film has a value of 0.48 ± 0.10 MPa, significantly higher than the F-g35-NC2 (0.20 ± 0.03 MPa) and F-g35-NC4 (0.23 ± 0.02 MPa) films. The incorporation of nanoclays in the proportions studied reduces the tensile strength. This behavior could be attributed to a saturation phenomenon. This phenomenon negatively affects the dispersion of clay particles in the polymer matrix, which can lead to the formation of aggregates. These aggregates interfere with interparticle interactions and the viscosity of the mixture, negatively impacting the mechanical properties of the material [

40].

Regarding the deformation results, it can be stated that the reinforced films exhibit mechanical characteristics that allow them to compete with synthetic plastics. These films exhibit elongation percentages of 44.57% and 66.90% and are classified as semi-rigid materials. This indicates limited scope for elastic deformation and the ability to recover their shape after the application of force. This phenomenon could be attributed to the plasticizing effect exerted by both glycerol and nanoclay on the polymer matrix, increasing the flexibility of the material [

30]. This greater flexibility can be advantageous in applications that require a material capable of deforming without fracturing. The deformability of this bioplastic offers numerous opportunities for film development, positioning it as a viable alternative to synthetic materials such as polypropylene and polystyrene [

41].

The water vapor transmission rate is a critical variable in the evaluation of the barrier properties of films. In this study, the base film F-g35-NC0 exhibits a rate of 0.17 ± 0.095 g/m

2.day. It can be inferred that with the incorporation of the hydrophilic plasticizer (glycerol) in the polymer matrix, the water vapor transmission rate of the film increases, by decreasing molecular interactions and increasing the spaces between the polymer chains [

42]. Formulations containing F-g35-NC0 show significantly lower rates, with values of 0.054 ± 0.071 g/m

2.day and 0.003 ± 0.011 g/m

2.day for concentrations of 2% and 4%, respectively. These results show a significant decrease in water vapor permeability with increasing nanoclay concentration. This trend is consistent with the barrier effect that nanometric-scale compounds provide to the polymer matrix. The above suggests that the incorporation of silicate improves mechanical properties and also optimizes the functionality of films in applications requiring effective humidity control. The layered silicate structure creates a winding path for water vapor molecules to traverse the material. This increases the tortuosity and transit time of the molecules, thereby reducing water vapor permeability [

43]. It also generates a more complex structure, which leads to improved water vapor barrier properties of films [

44]. The ability to reduce water vapor permeability is critical in the design of packaging and coating materials, due to the required protection against moisture that preserves the quality of the product inside [

45].

The tear resistance results show significant differences between the film formulations analyzed. The base film F-g35-NC0 presents a resistance of 0.090 ± 0.272 kg, considerably lower than the films with 2% (0.680 ± 0.187 kg) and 4% (0.740 ± 0.009 kg) nanoclays. These data indicate that the incorporation of nanoclays significantly improves the tear resistance. This increase can be attributed to better cohesion and a more robust structure in the polymer matrix. It suggests that nanoclays act as a filler, and also contribute to the mechanical integrity of the material. This is due to the presence of functional groups that interact with starch and plasticizer [

46]. This property is key for applications that require greater durability and resistance during handling.

4. Conclusions

The addition of nanoclays, particularly montmorillonite, at a 4% concentration demonstrated a significant improvement in the thermal properties, deformation percentage, and tear resistance of plastic films. These results highlight the potential of nanoclays as an effective reinforcement, making them a viable alternative for packaging applications requiring greater mechanical strength and durability. The addition of nanoclays at concentrations of 2% and 4% demonstrated a decrease in the water vapor transmission rate, suggesting that nanoclays not only improve mechanical properties but also contribute to a stronger moisture barrier. This behavior is crucial for packaging applications requiring effective vapor permeability control. The contact angle results for films with the addition of nanoclays show an increase in this angle, indicating a lower affinity for water. This increase in contact angle suggests that nanoclays contribute to improving the hydrophobic properties of the films, which would be beneficial for applications where greater resistance to moisture is required.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- The circular economy for plastics: a European overview. Avaliable online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/the-circular-economy-for-plastics-a-european-analysis-2024/ (Accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Singh, P., Pandey, V. K., Singh, R., Singh, K., Dash, K. K., & Malik, S. Unveiling the potential of starch-blended biodegradable polymers for substantializing the eco-friendly innovations. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 2024, 15, 101065. [CrossRef]

- Plastic pollution is growing relentlessly as waste management and recycling fall short, OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2022/02/plastic-pollution-is-growing-relentlessly-as-waste-management-and-recycling-fall-short.html (Accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Rahardiyan, D., Moko, E. M., Tan, J. S., & Lee, C. K. Thermoplastic starch (TPS) bioplastic, the green solution for single-use petroleum plastic food packaging – A review. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2023, 168, 110260. [CrossRef]

- Cataño, F. A., Moreno-Serna, V., Cament, A., Loyo, C., Yáñez-S, M., Ortiz, J. A., & Zapata, P. A. Green composites based on thermoplastic starch reinforced with micro- and nano-cellulose by melt blending - A review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023, 248, 125939. [CrossRef]

- Rivadeneira-Velasco, K. E., Utreras-Silva, C. A., Díaz-Barrios, A., Sommer-Márquez, A. E., Tafur, J. P., & Michell, R. M. Green Nanocomposites Based on Thermoplastic Starch: A Review. Polymers. 2021, 13(19), 3227. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zhou, M., Cheng, G., Cheng, F., Lin, Y., and Zhu, P. X. Fabrication and characterization of starch-based nanocomposites reinforced with montmorillonite and cellulose nanofibers. Carbohydr Polym. 2019, vol. 210, pp. 429–4362. [CrossRef]

- Ley 2232, por la cual se establecen medidas tendientes a la reducción gradual de la producción u consumo de ciertos productos plásticos de un solo uso y se dictan otras disposiciones. ANDI. Avaliable online: https://www.andi.com.co/Uploads/LEY%202232%20DE%2007%20DE%20JULIO%20DE%202022.pdf (Accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Plan Nacional para la Mesa Nacional para la Gestion Sostenible de los Plasticos de un Solo Uso. Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. Avaliable online: https://www.minambiente.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/plan-nacional-para-la-gestion-sostenible-de-plasticos-un-solo-uso-minambiente.pdf (Accessed on 18 Ocotber 2024).

- Minciencias firma alianza para desarrollar y lanzar el Clúster Colombiano de Bioplásticos. Minciencias. Available online: https://minciencias.gov.co/sala_de_prensa/minciencias-firma-alianza-para-desarrollar-y-lanzar-el-cluster-colombiano (Accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Yuan, N., Xu, L., Zhang, L., Ye, H., Zhao, J., Liu, Z., & Rong, J. Superior hybrid hydrogels of polyacrylamide enhanced by bacterial cellulose nanofiber clusters. Materials Science and Engineering. 2016, C, 67, 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Bioeconomía para una Colombia potencia viva y diversa: Hacia una sociedad impulasada por el conocimiento. Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación. Avaliable online: https://minciencias.gov.co/sites/default/files/upload/paginas/bioeconomia_para_un_crecimiento_sostenible-qm_print.pdf (Accessed on 18 Ocotber 2024).

- Abdolbaghi, S., Pourmahdian, S., & Saadat, Y. Preparation of poly(acrylamide)/nanoclay organic-inorganic hybrid nanoparticles with average size of ∼250 nm via inverse Pickering emulsion polymerization. Colloid and Polymer Science, 2014, 292(5), 1091–1097. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. C., Franco, C. M. L., Júnior, M. S. S., & Caliari, M. Structural characteristics and gelatinization properties of sour cassava starch. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2016, 123(2), 919–926. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-J., Huang, S.-Y., Wang, T.-H., Lin, T.-Y., Huang, N.-C., Shih, O., Jeng, U.-S., Chu, C.-Y., & Chiang, W.-H. Clay nanosheets simultaneously intercalated and stabilized by PEGylated chitosan as drug delivery vehicles for cancer chemotherapy. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2023, 302, 120390. [CrossRef]

- Jie, X., Lin, C., Qian, C., He, G., Feng, Y., & Yin, X. Preparation and properties of thermoplastic starch under the synergism of ultrasonic and elongational rheology. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2024, 274, 133155. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Li, X., Gao, B., & Zhang, S. Reactive extrusion fabrication of thermoplastic starch with Ca2+ heterodentate coordination structure for harvesting multiple-reusable PBAT/TPS films. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2024, 339, 122240. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. Composition, structure, physicochemical properties, and modifications of cassava starch. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2015, 122, 456–480. [CrossRef]

- Mina, J. Caracterización físico-mecánica de un almidón termoplástico (TPS) de yuca y análisis interfacial con fibras de Fique. Biotecnologia en el Sector Agripecuario y Agroindustrial, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 99–109, 2012.

- Moreno-Sader, K., García-Padilla, A., Realpe, A., Acevedo-Morantes, M., & Soares, J. B. P. Removal of Heavy Metal Water Pollutants (Co 2+ and Ni 2+ ) Using Polyacrylamide/Sodium Montmorillonite (PAM/Na-MMT) Nanocomposites. ACS Omega, 2019, 4(6), 10834–10844. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A. M., Aziz, S. B., Brza, M. A., Saeed, S. R., Al-Asbahi, B. A., Sadiq, N. M., Ahmed, A. A. A., & Murad, A. R. Glycerol as an efficient plasticizer to increase the DC conductivity and improve the ion transport parameters in biopolymer based electrolytes: XRD, FTIR and EIS studies. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 2022, 15(6), 103791. [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, M. G., Velasco, R., & Fernández, A. Caracterización de almidones de yuca nativos y modificados para la elaboración de empaques biodegradables. Biotecnología En El Sector Agropecuario Y Agroindustrial, 2013, 11(1), 21–30. Recuperado a partir de https://revistas.unicauca.edu.co/index.php/biotecnologia/article/view/1222.

- Chen, X., Yao, W., Gao, F., Zheng, D., Wang, Q., Cao, J., Tan, H., & Zhang, Y. Physicochemical Properties Comparative Analysis of Corn Starch and Cassava Starch, and Comparative Analysis as Adhesive. Journal of Renewable Materials, 2021, 9(5), 979–992. [CrossRef]

- Elkhalifah, A. E. I., Maitra, S., Azmi Bustam, M., & Murugesan, T. Thermogravimetric analysis of different molar mass ammonium cations intercalated different cationic forms of montmorillonite. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2012, 110(2), 765–771. [CrossRef]

- Olopade, B. K., Nwinyi, O. C., Adekoya, J. A., Lawal, I. A., Abiodun, O. A., Oranusi, S. U., & Njobeh, P. B. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Modified Montmorillonite Clay for Mycotoxin Decontamination in Cereal Grains. The Scientific World Journal, 2020, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, C., & Pulgarin, H. L. C. Study of the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Thermoplastic Starch/Poly(Lactic Acid) Blends Modified with Acid Agents. Processes, 2021, 9(4), 578. [CrossRef]

- Zanini, N. C., Ferreira, R. R., Barbosa, R. F. S., de Souza, A. G., Camani, P. H., Oliveira, S. A., Mulinari, D. R., & Rosa, D. S. Two different routes to prepare porous biodegradable composite membranes containing nanoclay. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2023, 140(44). [CrossRef]

- Bangar, S. P., Whiteside, W. S., Ashogbon, A. O., & Kumar, M. Recent advances in thermoplastic starches for food packaging: A review. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 2021, 30, 100743. [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, C. N., Kling, I. C. S., Ferreira, W. H., Andrade, C. T., & Simao, R. A. Starch films containing starch nanoparticles as produced in a single step green route. Industrial Crops and Products, 2022, 177, 114481. [CrossRef]

- Calambas, H. L., Fonseca, A., Adames, D., Aguirre-Loredo, Y., & Caicedo, C. Physical-Mechanical Behavior and Water-Barrier Properties of Biopolymers-Clay Nanocomposites. Molecules, 2021, 26(21), 6734. [CrossRef]

- Dang, K. M., Yoksan, R., Pollet, E., & Avérous, L. Morphology and properties of thermoplastic starch blended with biodegradable polyester and filled with halloysite nanoclay. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2020, 242, 116392. [CrossRef]

- Müller, C. M. O., Laurindo, J. B., & Yamashita, F. Composites of thermoplastic starch and nanoclays produced by extrusion and thermopressing. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2012, 89(2), 504–510. [CrossRef]

- Gil, E. & Mesa, M. Efectos de la modificación de arcilla con ácido cítrico en la morfología y retrogradación de almidón termoplástico (TPS) plastificado con glicerol. Professional degree, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia, 2013.

- Gutiérrez, T. J. Starch-based food packaging films processed by reactive extrusion/thermo-molding using chromium octanoate-loaded zeolite A as a potential triple-action mesoporous material (reinforcing filler/food-grade antimicrobial organocatalytic nanoreactor). Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 2022, 34, 100974. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, M., & Murillo, E. A. Structural, thermal, rheological, morphological and mechanical properties of thermoplastic starch obtained by using hyperbranched polyester polyol as plasticizing agent. DYNA, 2018, 85(206), 178–186. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Hou, A., Hu, X., Lu, X., & Qu, J.-P. Effect of elongational rheology on plasticization and properties of thermoplastic starch prepared by biaxial eccentric rotor extruder. Industrial Crops and Products, 2022, 176, 114323. [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, G., Manepalli, R. K. N. R., & Apparao, G. Contact Angle Measurement Techniques for Nanomaterials. In Thermal and Rheological Measurement Techniques for Nanomaterials Characterization 2017, (pp. 173–195). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, T. J., Ollier, R., & Alvarez, V. A. Surface Properties of Thermoplastic Starch Materials Reinforced with Natural Fillers. 2018, (pp. 131–158). [CrossRef]

- Noshirvani, N., Hong, W., Ghanbarzadeh, B., Fasihi, H., & Montazami, R. Study of cellulose nanocrystal doped starch-polyvinyl alcohol bionanocomposite films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 107, 2065–2074. [CrossRef]

- Noguera-Guayacan, C. J., Fernández-Solarte, A. M., & Villalba-Vidales, J. A. Efecto de arcilla Montmorillonita K10 como refuerzo mecánico en almidón termoplástico de yuca. AiBi Revista de Investigación, Administración e Ingeniería, 2022, 10(3), 71–76. [CrossRef]

- Medina, L. Evaluación de los parámetros de procesamiento y formulación de involucrados en el desarrollo de una lamina TPS para termoformado. Pressional degree, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia, 2007.

- Giannakas, A., Grigoriadi, K., Leontiou, A., Barkoula, N.-M., & Ladavos, A. Preparation, characterization, mechanical and barrier properties investigation of chitosan–clay nanocomposites. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 108, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, K., Asadpour, G., & Sharifi, S. H. Bio nanocomposites based on cationic starch reinforced with montmorillonite and cellulose nanocrystals: Fundamental properties and biodegradability study. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2020, 146, 374–386. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A., Yaraki, M. T., Ghorbanpour, M., Agarwal, S., & Gupta, V. K. Enhanced Antibacterial effect of chitosan film using Montmorillonite/CuO nanocomposite. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2018, 109, 1219–1231. [CrossRef]

- Punia Bangar, S., Whiteside, W. S., Chaudhary, V., Parambil Akhila, P., & Sunooj, K. V. Recent functionality developments in Montmorillonite as a nanofiller in food packaging. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2023, 140, 104148. [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswamy, R. ., & Sukhadia, A. Orientation characteristics of LLDPE blown films and their implications on Elmendorf tear performance. Polymer, 2000, 41(26), 9205–9217. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Torque rheogram of starch samples with different glycerol contents.

Figure 1.

Torque rheogram of starch samples with different glycerol contents.

Figure 2.

Rheogram obtained from biopolymer mixtures with the incorporation of nanoclay.

Figure 2.

Rheogram obtained from biopolymer mixtures with the incorporation of nanoclay.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of the polymeric bionanocomposites.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of the polymeric bionanocomposites.

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscopies obtained for the clay at different magnifications (3000x, 2000x and 1000x).

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscopies obtained for the clay at different magnifications (3000x, 2000x and 1000x).

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscope images obtained for clay at different magnifications (4000x, 3000x and 1500x).

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscope images obtained for clay at different magnifications (4000x, 3000x and 1500x).

Figure 6.

SEM micrographs of films (a) cross-section P, (b) cross-section F-g35-NC2, c) cross-section F-g35-NC4, (d) surface section F-g35-NC0, (e) surface section F-g35-NC2, and (f) surface section F-g35-NC0.

Figure 6.

SEM micrographs of films (a) cross-section P, (b) cross-section F-g35-NC2, c) cross-section F-g35-NC4, (d) surface section F-g35-NC0, (e) surface section F-g35-NC2, and (f) surface section F-g35-NC0.

Figure 7.

a) TGA starch and b) TGA nanoclay, and c) DSC curves of starch and nanoclay.

Figure 7.

a) TGA starch and b) TGA nanoclay, and c) DSC curves of starch and nanoclay.

Figure 8.

(a) Thermogravimetric analysis of S-g35-NC0, S-g35-NC2, and S-g35-NC4 (b) TGA derivative of S-g35-NC0, S-g35-NC2, and S-g35-NC4.

Figure 8.

(a) Thermogravimetric analysis of S-g35-NC0, S-g35-NC2, and S-g35-NC4 (b) TGA derivative of S-g35-NC0, S-g35-NC2, and S-g35-NC4.

Figure 9.

DSC analysis of S-g35-NC0, S-g35-NC2, and S-g35-NC4.

Figure 9.

DSC analysis of S-g35-NC0, S-g35-NC2, and S-g35-NC4.

Figure 10.

Thermograms of the thermal transitions of the bionanocomposite films.

Figure 10.

Thermograms of the thermal transitions of the bionanocomposite films.

Figure 11.

Complex viscosity curves as a function of the oscillation frequency of the bionanocomposites.

Figure 11.

Complex viscosity curves as a function of the oscillation frequency of the bionanocomposites.

Table 3.

Maximum torque values obtained in the bionanocomposites obtained in the torque rheometer.

Table 3.

Maximum torque values obtained in the bionanocomposites obtained in the torque rheometer.

| Sample |

Maximum torque [N.m] |

| S-g35-NC0 |

8.5 |

| S-g35-NC2 |

7.6 |

| S-g35-NC4 |

8.2 |

| S-g40-NC0 |

6.5 |

| S-g40-NC2 |

5.4 |

| S-g40-NC4 |

6.1 |

Table 4.

Contact angle values obtained when a water droplet came into contact with the surface of P, 2% PNA, and 4% PNA films.

Table 5.

Results for the mechanical and barrier properties of the films.

Table 5.

Results for the mechanical and barrier properties of the films.

| Films |

Thickness |

Tensile strength |

Percentage of deformation |

Water vapor transmission rate |

Tear resistance |

| (mm) |

(MPa) |

(%) |

(g/m2.day) |

(kg) |

| F-g35-NC0 |

0.11 ± 0.03a

|

0.48 ± 0.10a

|

6.80 ± 1.01a

|

0.17 ± 0.095a

|

0.090 ± 0.272a

|

| F-g35-NC2 |

0.78 ± 0.12b

|

0.20 ± 0.03b

|

44.57 ± 3.67b

|

0.054 ± 0.071b

|

0.680 ± 0.187b

|

| F-g35-NC4 |

0.71 ± 0.07b

|

0.23 ± 0.02b

|

66.90 ± 4.85c

|

0.003 ± 0.011c

|

0.740 ± 0.009b

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).