1. Introduction

Disposable plastic packaging and other non-biodegradable products derived from fossil fuels are accumulating in landfills at alarming rates. A significant portion of this waste eventually degrades into microplastics, contaminating various ecosystems. Despite an annual global plastic production exceeding 300 million tons, recycling rates remain low, with only 10 to 13 percent of plastic waste being effectively recycled [

1]. The widespread use of plastic is largely driven by its durability, thermal and mechanical properties, and ease of processing. However, the environmental crisis resulting from plastic waste has triggered a global search for sustainable alternatives. In response to this challenge, the development of biodegradable films from affordable, eco-friendly materials has gained considerable attention. Such materials could help reduce waste accumulation, limit reliance on fossil fuels, and lower carbon dioxide emissions. Biodegradable plastics, derived from renewable plant-based resources such as starch and cellulose, can be naturally decomposed by microorganisms due to their biological origin. Chitosan, starch, and cellulose are among the most extensively studied biopolymers for food packaging applications [

2]. Starch, in particular, is favored due to its availability, low cost, and biodegradability. However, starch-based plastics often exhibit brittleness and inferior mechanical properties compared to synthetic polymers, which limits their applicability in packaging [

3].

The onion (

Allium cepa) is a widely cultivated and consumed vegetable across the globe. According to FAO data, the global annual harvest amounts to 93.23 million tons, with China being the leading producer. Algeria ranks as the world’s tenth-largest producer, contributing 1.76 million tons. Despite their culinary value, onions generate a considerable amount of waste, particularly peels, which are typically discarded due to their strong odor, rendering them unsuitable for animal feed or fertilizer. Conventional disposal methods such as landfilling, or incineration are both costly and environmentally damaging. This is especially wasteful considering the high content of valuable fibers and phytochemicals present in onion peels. In a recent study, we characterized the flavonoid profiles and biological activities of onion skins from two traditional varieties cultivated in southern Italy. The phytochemical analysis revealed that these by-products are particularly rich in flavonols and anthocyanins, such as quercetin, its glycosides, and cyanidin 3-glucoside, and exhibit significant antioxidant and anti-diabetic activities, as well as proliferative effects on human fibroblasts. These findings clearly demonstrate the potential of onion skin as a source of bioactive compounds for applications in industrial, nutraceutical, and cosmetic sectors [

4]. Onion peel waste, therefore, represents an underutilized resource that can be valorized into value-added products. Given the environmental burden posed by conventional plastics, the transformation of food waste into biodegradable packaging offers a promising and sustainable alternative. Utilizing onion peel powder in biodegradable film formulations may contribute to addressing both ecological and economic issues related to food waste and plastic pollution. To improve the performance of biodegradable plastics, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is commonly applied as an optimization tool [

5]. This statistical approach employs mathematical modeling to identify optimal conditions by analyzing the interactions among multiple input variables. The Central Composite Design (CCD) is a widely used RSM technique, particularly effective for evaluating the influence of formulation variables on material properties. In this study, biodegradable composites were developed using cassava starch and onion peel powder. A Central Composite Design, implemented via Minitab 19, was used to optimize the composition with respect to three key performance indicators: tensile strength, elongation, and biodegradability. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the fabrication of bioplastics using this specific compound in combination with a CCD-based experimental design.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Standards and Materials

Ultrapure water (18 MΩ) was obtained using a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Bedford, USA). MS-grade water (H2O), methanol (MeOH), and acetonitrile (CH3CN) were supplied by Romil (Cambridge, UK). Analytical grade MeOH, CH3CN, Formic acid (HCOOH) and absolute ethanol (EtOH) were supplied by Carlo Erba reagents (Milan, Italy). MS-grade formic acid (HCOOH), quercetin (purity ≥ 95%), isorhamnetin (purity ≥ 95% HPLC), kaempferol (purity ≥ 97%), protocatechuic acid (purity 95%).

2.2. Onion Peels Powder (OPP) Preparation

Onion peels were collected from a local market in the Oum El Bouaghi district. In the laboratory, any adhering dirt or debris was removed by thoroughly washing the peels with water. To facilitate drying, the peels were cut into smaller pieces and left to dry under ambient conditions until a constant weight was achieved. Once dried, the peels were ground using a ball mill (FRITSCH PULVERISETTE 7 premium line) and the resulting powder was sieved through a 45 µm mesh to obtain uniformly sized particles. The onion peel powder (OPP) was stored in unsealed glass bottles at room temperature and pressure until further use.

2.3. Onion Peels Powder (OPP) Extraction

Exhaustive extraction was performed using ultrasound-assisted solid-liquid extraction (UAE) at 25 ◦C in a thermostat-controlled ultrasound bath (Labsonic LBS2, Treviglio, Italy) at the frequency of 20.0 kHz. Dried Allium cepa skins were extracted using aqueous EtOH (70% v/v) and a matrix/solvent ratio of 1:20 (3 × 30 min). At each extraction cycle, after centrifugation 10 min at 9000 g, the extracts of each variety were pooled, filtered (Whatman No. 1 filter) and freeze-dried (freeze dryer Alpha 1–2 LD, Christ, Germany), after the removal of the organic solvent under vacuum at 40 ◦C in a rotary evaporator (Rotavapor R-200, Buchi Italia s.r.l, Cornaredo, Italy). Extraction yields of 10.4% was obtained. Extract was then used for further chemical characterization.

2.4. Quantitative Analysis by UHPLC-UV

Quantitative analyses were performed using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA), equipped with an Ultimate 3000 RS pump, autosampler, column compartment, and variable wavelength detector. Chromatographic separation was carried out on a Kinetex C18 UHPLC column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phases consisted of MS-grade water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both containing 0.1% formic acid (HCOOH). The gradient elution program was as follows: 0–3 min, isocratic at 2% B; 3–5 min, linear gradient from 2% to 13% B; 5–9 min, isocratic at 13% B; 9–12 min, linear gradient from 13% to 18% B, held for 1 min; 13–17 min, linear gradient from 18% to 30% B; 17–21 min, linear gradient from 30% to 50% B; 21–22 min, linear gradient from 50% to 98% B, followed by washing and column re-equilibration for 5 min. The flow rate was set at 600 μL min⁻¹, the column temperature was maintained at 30 °C, and the injection volume was 5 μL. UV chromatograms were monitored at 295 and 365 nm, based on the absorption maxima of the phenolic compounds. Quantification was performed using an external standard calibration method. Calibration curves were generated using mixtures of two commercially available reference standard, protocatechuic acid and quercetin, across six concentration levels (6.25–100 μM), with triplicate injections for each level. The calibration curves showed good linearity (R² > 0.998) over the tested range.

Since not all phenolic compounds identified in the extract were available as commercial standards, quantification of quercetin derivatives was performed using the calibration curve of quercetin. Results were expressed as quercetin equivalents (mg/100 g dry matter). When necessary, extracts were diluted to ensure analyte concentrations fell within the dynamic range of the calibration curves.

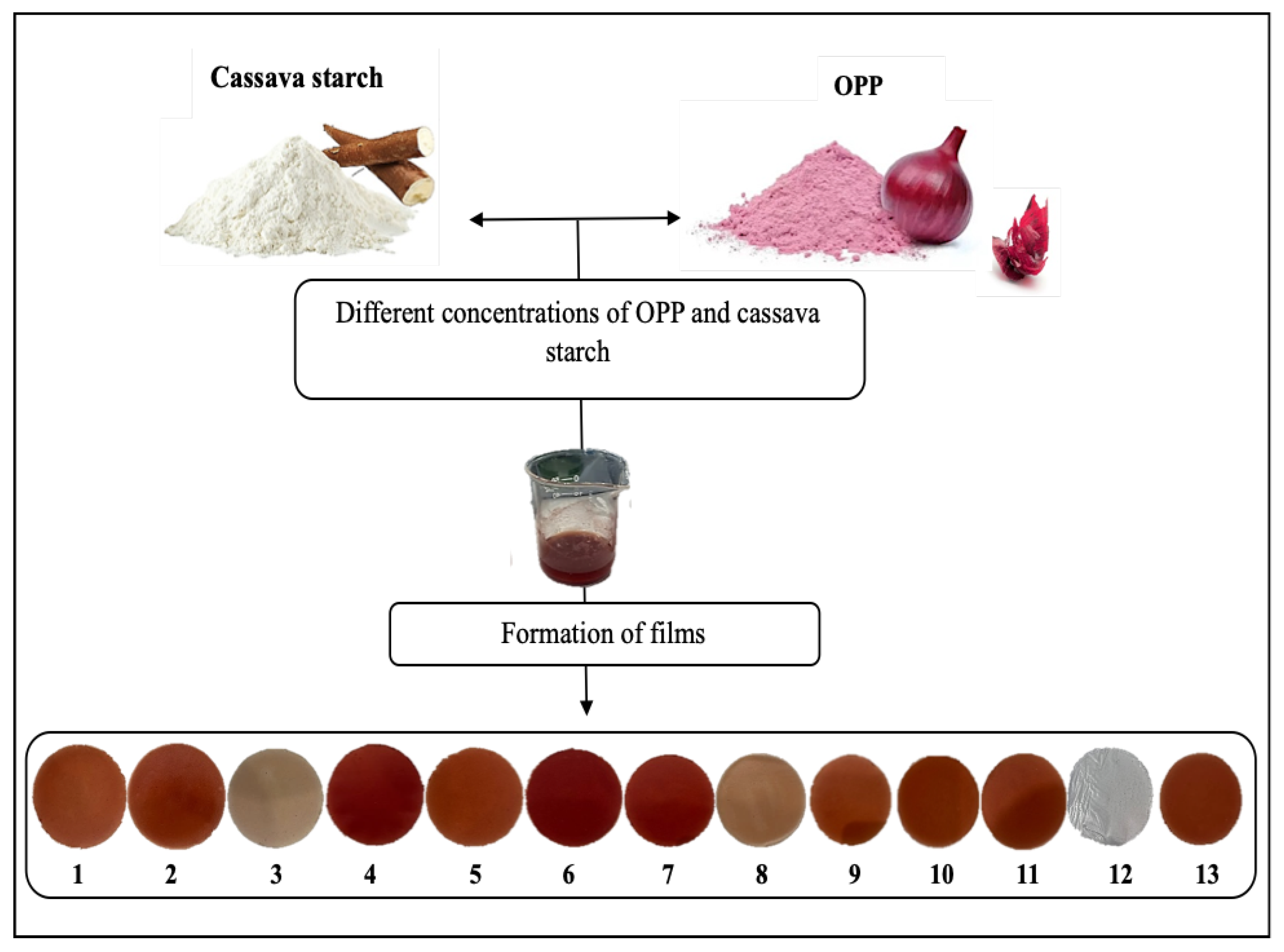

2.5. Starch-OPP Film Preparation

Starch–OPP films were produced using the casting method, following the procedure described by Oliveira Filho et al. (2019), with slight modifications. Film-forming solutions (FFSs) were prepared based on the experimental design described in

Table 1, incorporating cassava starch and OPP at ratios determined through preliminary optimization studies. To prepare the FFS, cassava starch was dissolved in an aqueous glycerol solution (2.5% v/v) and heated to 85 °C under continuous stirring at 280 rpm for 30 minutes. Simultaneously, OPP was dispersed in distilled water at 25 °C and stirred for 10 minutes. The OPP dispersion was then combined with the starch solution and stirred for an additional 2 minutes to ensure homogeneity. A volume of 25 mL of the resulting mixture was poured into Petri dishes (ϕ = 10 cm) and dried in an incubator at 25 °C for 24 hours (

Figure 1). The dried films were then peeled and stored in a desiccator under ambient conditions until further analysis.

Table 1.

Central composite design matrix with coded and uncoded experimental data for cassava starch and onion peel powder components in bioplastic formulation.

Table 1.

Central composite design matrix with coded and uncoded experimental data for cassava starch and onion peel powder components in bioplastic formulation.

| Run |

Coded Value X₁ (Cassava Starch) |

Coded Value X₂ (Onion PP) |

Uncoded Value X₁ (Cassava Starch, %) |

Uncoded Value X₂ (Onion PP %) |

| 1 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

20 |

| 2 |

-1.414 |

0 |

60 |

20 |

| 3 |

1 |

-1 |

94.142 |

5.8579 |

| 4 |

1 |

1 |

94.142 |

34.1421 |

| 5 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

20 |

| 6 |

0 |

1.414 |

80 |

40 |

| 7 |

-1 |

1 |

65.858 |

34.1421 |

| 8 |

-1 |

-1 |

65.858 |

5.8579 |

| 9 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

20 |

| 10 |

1.414 |

0 |

100 |

20 |

| 11 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

20 |

| 12 |

0 |

-1.414 |

80 |

0 |

| 13 |

0 |

0 |

80 |

20 |

2.6. Experimental Design

A Central Composite Design (CCD) with two factors, cassava starch (X₁) and onion peel powder (X₂), was employed to optimize the formulation of the biodegradable plastic. cThis design included five levels for each factor (−α, −1, 0, +1, +α), allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of both individual and interactive effects on the selected response variables.

The content of cassava starch (X₁) ranged from 60% to 80%, while onion peel powder (X₂) varied from 0% to 40%. These ranges were established based on preliminary experimental screening.

The design comprised 13 experimental runs (

Table 2). The following response variables were selected as critical indicators of suitability for packaging applications: tensile strength (Y₁), elongation at break (Y₂), and biodegradability (Y₃).

The relationship between the independent variables and each response was modeled using the second-order polynomial equation 1:

In this model, b0 represents the predicted response at the center point (0,0); b1 and b2 denote the linear effects of cassava starch and onion peel powder, respectively; b11 and b22represent the quadratic effects; and b12 accounts for the interaction between the two factors (Fairouz et al., 2018).

2.7. Mechanical Test

The mechanical properties of the films, specifically tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break (EB), were evaluated using a texture analyzer (TA.Zwick/Roell), following a modified procedure based on Santos et al. [

6]. Rectangular film strips measuring 50 mm × 20 mm were prepared for testing. The tests were conducted at an initial crosshead speed of 10 mm/min, with a gauge length (distance between grips) set at 50 mm. The instrument software (testXpert V12.0) continuously recorded the force–displacement data throughout the test. Tensile strength was determined as the maximum force sustained before breakage, while elongation at break was calculated as the percentage of strain at the point of rupture.

2.8. Biodegradability Test

The biodegradability of the films was evaluated based on weight loss, following a modified version of the method described by Afshar et al. [

7]. Square film samples (2 cm × 2 cm) were buried at a depth of 5 cm in soil-filled pots and watered daily to maintain moisture levels. After 30 days of incubation under ambient conditions, the samples were carefully removed, gently cleaned to eliminate any adhering soil, and dried before being weighed. The percentage of weight loss was calculated using Equation (2), where W

iW

i is the initial dry mass and W

fW

f is the final dry mass after burial.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses, including response surface modeling and optimization, were performed using Minitab 19 software (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to evaluate the effects of cassava starch and onion peel powder content on the mechanical properties and biodegradability of the bioplastic films. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Quantification of Phenolic Compounds by UHPLC-UV

Fourteen phenolic compounds were identified and quantified in the red onion peel extract using UHPLC-UV analysis. Compound identification was carried out by comparing UV absorption spectra, retention times, and chromatographic profiles with those previously reported by our research team Celano et al. [

4]. The identification of these compounds (

Table 1) was supported by the strong agreement of their retention times and UV-Vis spectral features with those of commercial or isolated standards, as well as with previously characterized compounds. Quantification was performed using an external standard calibration approach, employing commercially available standards including quercetin, kaempferol, isorhamnetin, and protocatechuic acid. Due to the unavailability of certain standards, quercetin derivatives were quantified using the quercetin calibration curve and results are expressed as quercetin equivalents (mg per 100 g dry matter). Despite the absence of mass spectrometric data in this study, the detailed analytical framework established in our previous work enabled reliable identification and quantification of major phenolic constituents in the extract.

Table 1.

Quantitative determination of phenolic compounds in red onion peel extract by UHPLC-UV.

Table 1.

Quantitative determination of phenolic compounds in red onion peel extract by UHPLC-UV.

| N° |

Compound Name |

R(t) (min) |

RDS (%) |

mg/100 g DM ± RDS |

| 1 |

Protocatechuic acid |

1.2 |

1.8 |

135.8 ± 6 |

| 2 |

2-(3,4-Dihydroxybenzoyl)-2,4,6-trihydroxy-3(2H)-benzofuranone |

6.0 |

3.9 |

116.5 ± 4 |

| 3 |

Quercetin-7,4′-diglycoside |

6.5 |

7.0 |

63.5 ± 8 |

| 4 |

Quercetin-3,4′-diglycoside |

6.9 |

5.5 |

74.3 ± 12 |

| 5 |

Quercetin-4′-glycoside |

10.3 |

6.4 |

351.3 ± 8 |

| 6 |

Isorhamnetin-4′-glycoside |

12.5 |

6.6 |

nq |

| 7 |

Quercetin |

13.5 |

7.6 |

510.4 ± 12 |

| 8 |

Kaempferol |

16.4 |

2.0 |

nq |

| 9 |

Isorhamnetin |

16.7 |

2.6 |

nq |

| 10 |

Quercetin dimer 4′-glycoside |

17.1 |

1.9 |

44.1 ± 4 |

| 11 |

Quercetin dimer 4′-glycoside |

18.2 |

0.8 |

43.3 ± 6 |

| 12 |

Quercetin dimer hexoside |

18.5 |

2.5 |

nq |

| 13 |

Quercetin dimer |

19.4 |

0.8 |

110.3 ± 2 |

| 14 |

Quercetin trimer |

20.7 |

2.4 |

62.8 ± 6 |

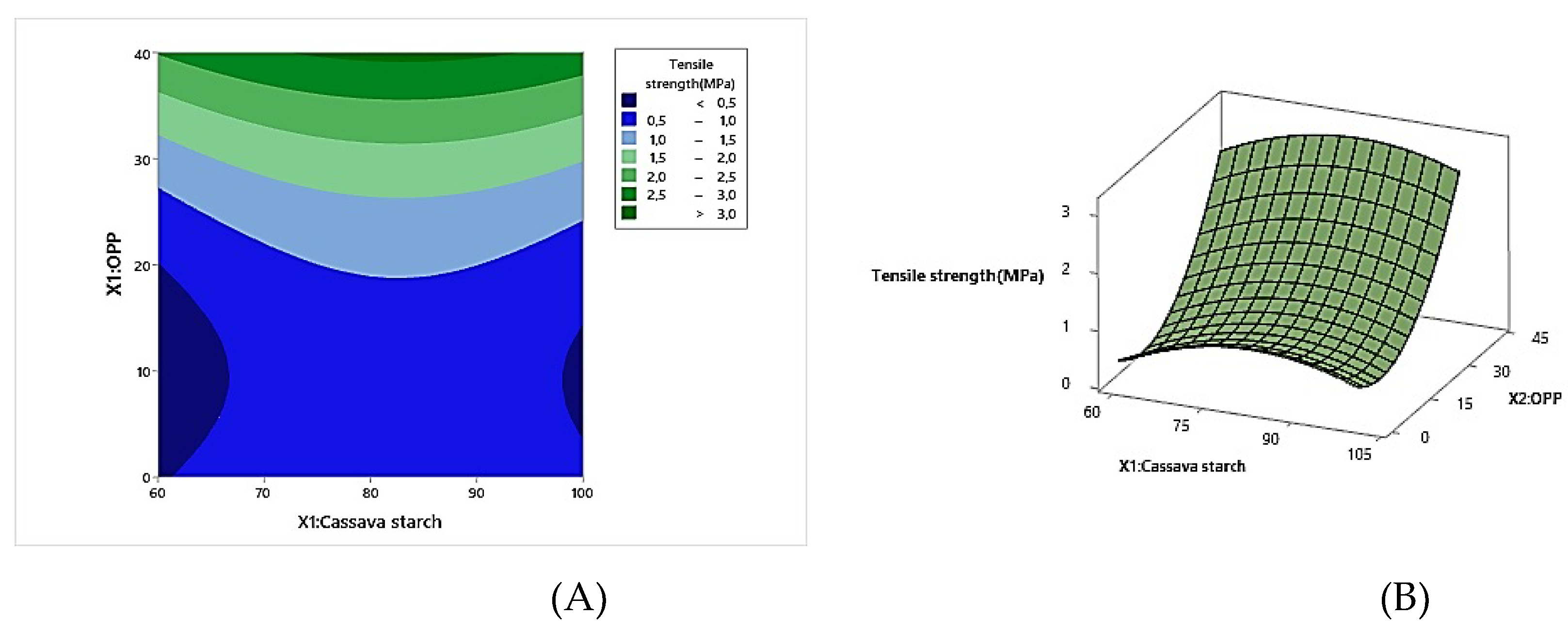

3.2. Effect of Cassava Starch and Onion Peel Powder on Tensile Strength of Film

The effect of cassava starch (X₁) and onion peel powder (X₂) on the tensile strength of the biodegradable films is summarized in

Table 2. The tensile strength of the bioplastics exhibited significant variation across the experimental runs, ranging from 0.52 MPa to 3.87 MPa (

Table 2). These values align with the findings of Kechichian et al. [

8], who reported similar tensile strength values for cassava starch films containing natural antimicrobial agents, and those of dos Santos Caetano et al. [

9], who observed comparable values in cassava starch films incorporated with natural compounds. The highest tensile strength was observed in the formulation with the highest concentration of onion peel powder (40%). This suggests that onion peel powder may act as a reinforcing agent within the bioplastic matrix, enhancing its tensile strength. As predicted by the regression model (

Table 3), tensile strength was significantly (p < 0.05) influenced by both the linear and quadratic terms of onion peel powder (OPP) content. The coefficient of the first-order term in Equation 3 (after excluding non-significant terms) indicated that tensile strength increased with higher OPP content. The model explained 81.53% of the variability in the tensile strength response (R² = 0.8153). The response surface plot (

Figure 2) further corroborates these findings, demonstrating a positive correlation between OPP content and tensile strength. At lower OPP concentrations, tensile strength decreased due to factors such as poor compatibility between starch and OPP, disruption of the starch matrix, and increased brittleness. However, as the OPP content increased, tensile strength improved due to enhanced interfacial adhesion, a reinforced polymer matrix, and greater resistance to deformation. This suggests the existence of an optimal OPP concentration at which tensile strength is maximized (

Figure 2). The observed enhancement in tensile strength can be attributed to two primary factors: (1) the formation of strong intermolecular hydrogen bonds, which promote the development of a rigid and continuous network within the film matrix, and (2) the presence of numerous oxygen (O) and hydroxyl (OH) groups in the quercetin structure of OPP. These functional groups are capable of forming electrostatic interactions with active groups in both starch and OPP, thereby enhancing film cohesion and ultimately increasing tensile strength [

10].

Table 2.

Mechanical properties and biodegradability of biodegradable plastics formulated with varying starch and OPP concentrations.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties and biodegradability of biodegradable plastics formulated with varying starch and OPP concentrations.

| Run |

Cassava Starch (%) |

Onion Peel Powder (%) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Elongation (%) |

Biodegradability (%) |

| 1 |

80 |

20 |

1.07 ± 0.017 e f

|

48.70 ± 0.021 f

|

30.83 ± 0.051 e f

|

| 2 |

60 |

20 |

0.75 ± 0.005 i

|

72.07 ± 0.025 c

|

30.04 ± 0.040 f

|

| 3 |

94.142 |

5.8579 |

0.58 ± 0.010 j

|

47.63 ± 0.01 g

|

32.08 ± 0.060 c

|

| 4 |

94.142 |

34.1421 |

1.52 ± 0.011 b

|

60.37 ± 0.015 d

|

26.00 ± 0.5 h

|

| 5 |

80 |

20 |

0.97 ± 0.015 g

|

47.24 ± 0.045 h

|

31.43 ± 0.030 c d e

|

| 6 |

80 |

40 |

3.87 ± 0.011 a

|

14.09 ± 0.030 l

|

27.43 ± 0.015 g

|

| 7 |

65.858 |

34.1421 |

1.41 ± 0.02 c

|

24.11 ± 0.051 k

|

31.00 ± 1.145 d e f

|

| 8 |

65.858 |

5.8579 |

0.52 ± 0.015 k

|

73.46 ± 0.060 b

|

36.96 ± 0.015 b

|

| 9 |

80 |

20 |

1.08 ± 0.01 d e

|

47.68 ± 0.026 g

|

30.69 ± 0.035 e f

|

| 10 |

100 |

20 |

1.11 ± 0.015 d

|

97.06 ± 0.065 a

|

25.21 ± 0.020 h

|

| 11 |

80 |

20 |

1.11 ± 0.015 d

|

52.85 ± 0.025 e

|

32.04 ± 0.037 c d

|

| 12 |

80 |

0 |

0.88 ± 0.015 h

|

38.15 ± 0.035 j

|

38.38 ± 0.170 a

|

| 13 |

80 |

20 |

1.03 ± 0.005 f

|

43.73 ± 0.015 i

|

32.20 ± 0.1 c

|

Table 3.

Regression coded coefficients for second-order polynomial equation representing the relationship between the responses and process variables.

Table 3.

Regression coded coefficients for second-order polynomial equation representing the relationship between the responses and process variables.

| Response |

Equation |

R² |

| Y₁: Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Y₁ = -6.56 + 0.184 X₁ - 0.051 X₂ + 0.002494 X₂² Equation 3 |

0.8153 |

| Y₂: Elongation (%) |

Y₂ = 681.3 - 14.97 X₁ - 4.44 X₂ + 0.08638 X₁² - 0.05974 X₂² + 0.0776 X₁ X₂ Equation 4 |

0.9723 |

| Y₃: Biodegradability (%) |

Y₃ = -1.1 + 1.132 X₁ - 0.440 X₂ - 0.00798 X₁² + 0.00522 X₂² Equation 5 |

0.9542 |

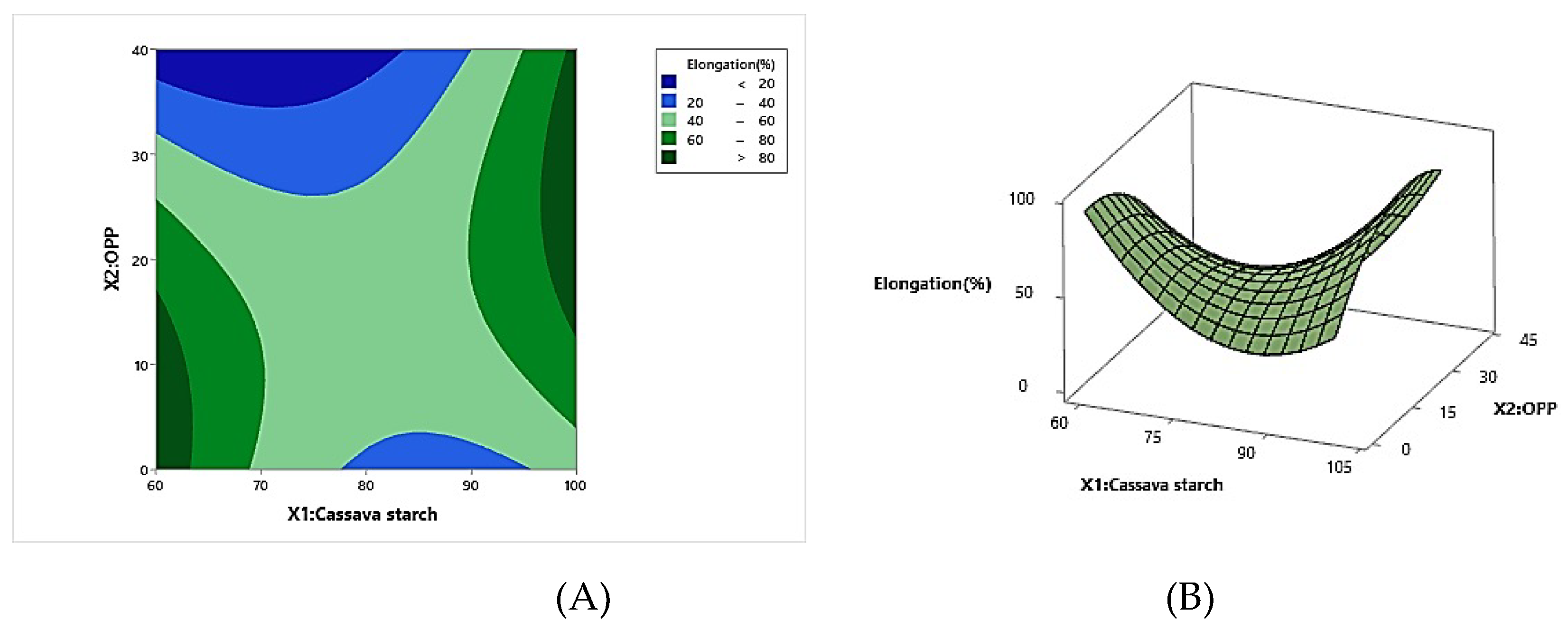

3.3. Effect of Cassava Starch and Onion Peel Powder on Elongation of Film

The elongation of the bioplastics varied significantly across runs, ranging from 14.09% to 97.06% (

Table 2). Similar trends were identified by Alqahtani et al. [

11] and Ayyubi et al. [

12] for films made from corn starch-based materials reinforced with date palm pits and chitosan/cassava starch/PVA/crude glycerol, respectively. The greatest elongation was observed in the run with the highest cassava starch content (100%), suggesting that cassava starch contributes to the bioplastic’s ductility.

The regression model (

Table 3) revealed that elongation was significantly influenced (p < 0.05) by both the linear and quadratic terms of cassava starch (X₁) and onion peel powder (OPP) concentration (X₂), as well as their interaction. The model explained 97.23% of the variation in elongation (R² = 0.9723). The coefficients of the first-order term in Equatin 4 (

Table 4) indicate that elongation increased with cassava starch content but decreased with OPP content. Additionally, cassava starch exhibited a negative quadratic effect, while OPP showed a positive quadratic effect on film elongation (p < 0.05). A positive interaction between cassava starch and OPP also influenced film elongation (

Table 3). The relationship between cassava starch, OPP content, and elongation is visualized in

Figure 3. Our films exhibited a reduction in elongation as the OPP content increased. This trend is consistent with findings by Adilah et al. [

13] and Piñeros et al. [

14], who reported reduced elongation with increased concentrations of mango kernel extract in films composed of soy protein isolate and fish gelatin, and rosemary in cassava starch films, respectively. Onion peel is a rich source of mono- and polysaccharides, including fructo-oligosaccharides, gelling pectin, and a low quantity of lignin-based dietary fiber, along with fragrant compounds exhibiting biological activity [

15]. These carbohydrates likely act as plasticizers, contributing to the observed decrease in elongation [

16]. The results of this investigation suggest that carbohydrates and bioactive compounds in OPP serve a plasticizing role in cassava starch films.

Figure 3.

The effect of cassava starch (x1) and OPP(X2) on the elongation response; surface contour (A) and three-dimensional plots (B).

Figure 3.

The effect of cassava starch (x1) and OPP(X2) on the elongation response; surface contour (A) and three-dimensional plots (B).

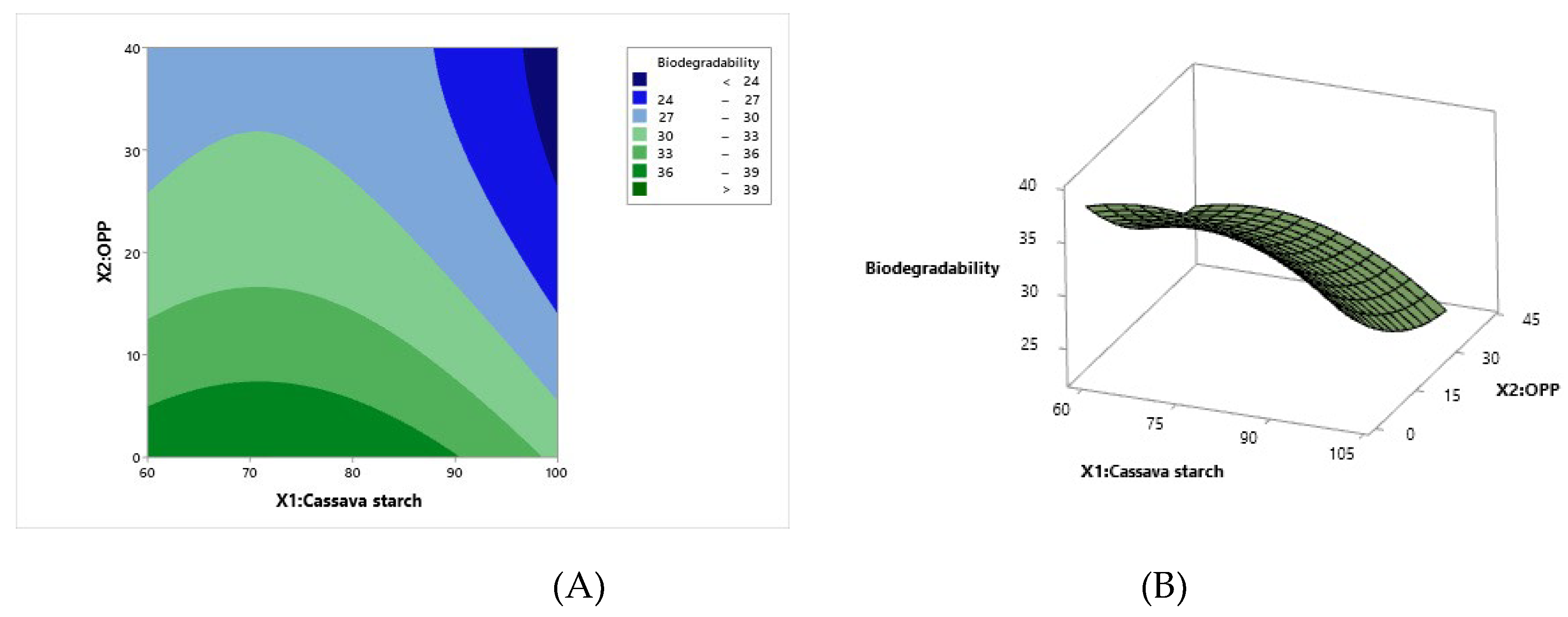

3.4. Effect of Cassava Starch and Onion Peel Powder on the Biodegradability of Film

The biodegradability of the bioplastics varied from 25.21% to 38.38% (

Table 2, Figure4). Similar trends were documented by Zhao et al. [

17] for Starch/PVA films enhanced with titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Interestingly, the highest biodegradability was observed in the run with the lowest onion peel powder content (0%), suggesting a potential negative impact of OPP on biodegradability. These results are consistent with earlier studies by Ayyubi et al. [

12] and Romero et al. [

18], which reinforce the significant impact of composition on the mechanical characteristics and biodegradability of eco-friendly films. The regression model (

Table 3) indicated that biodegradability was significantly affected (p < 0.05) by both linear and quadratic terms of cassava starch (X₁) and OPP content (X₂). The model explained 95.42% of the variation in biodegradability (R² = 0.9542). The coefficients from the first-order term in Equation 5 (

Table 4) show that biodegradability decreased with increasing levels of both cassava starch and OPP. Additionally, cassava starch exhibited a negative quadratic effect, while OPP showed a positive quadratic effect on film biodegradability (p < 0.05).

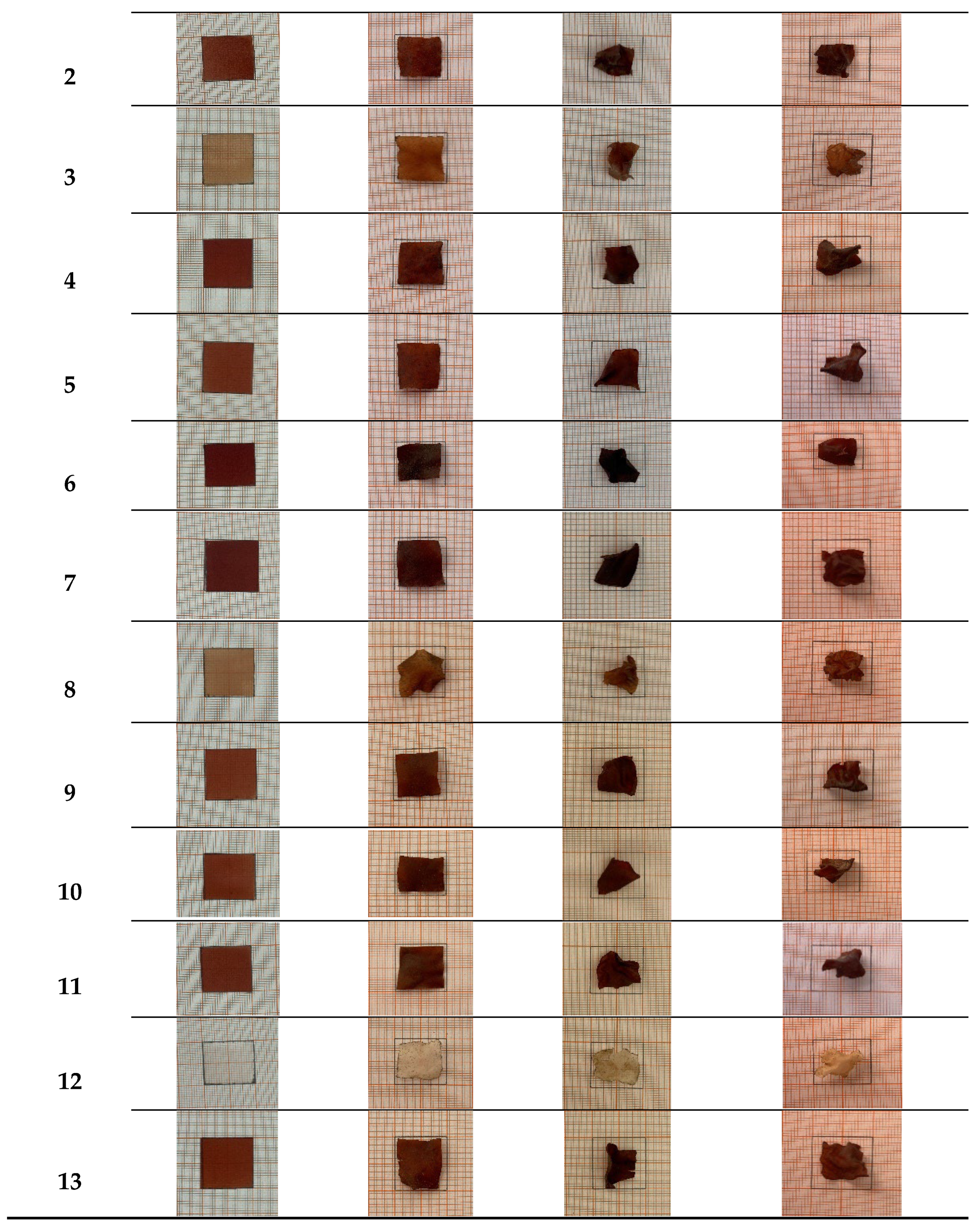

Figure 5 provides a visual representation of how cassava starch and onion peel powder (OPP) content relate to the biodegradability of the composite films. The images, spanning a 30-day degradation period, show that while initially the films are intact with diverse appearances, they generally undergo degradation characterized by shrinking size, shape distortion and fragmentation, increased brittleness and porosity, changes in surface texture, and sometimes color alterations. Importantly, the degree and speed of this breakdown differ among the various film formulations, indicating that the specific ratio of cassava starch to OPP significantly affects their biodegradability.Incorporating OPP into the bioplastic matrix seems to slightly hinder the biodegradation process. This effect is likely attributed to several factors. Firstly, the presence of phenolic compounds within OPP, known for their antimicrobial properties, can inhibit soil microbiota enzymatic activity. Secondly, the cellulose content in OPP contributes to its resistance to microbial breakdown compared to starch-based materials. While starch, consisting of glucose units connected via α-1,4 glycosidic linkages, is readily hydrolyzed by microorganisms, cellulose’s β-1,4 linkages create a more recalcitrant structure, hindering microbial attack and slowing overall biodegradation [

11,

19].

Figure 4.

The effect of cassava starch (x1) and OPP (X2) on the biodegradability response; surface contour (A) and three-dimensional plots (B).

Figure 4.

The effect of cassava starch (x1) and OPP (X2) on the biodegradability response; surface contour (A) and three-dimensional plots (B).

3.5. Optimization and model Validation

The previous section developed mathematical models correlating starch and OPP content with the selected response variables. Building upon these models, this section focuses on optimizing the biodegradable composite composition. According to Hun and Cennadios [

20], biodegradable films exhibiting tensile strength (TS) ranging from 1 to 10 MPa and elongation at break (EB) between 10% and 100% are considered satisfactory. Optimization was conducted based on specific criteria for each formulation. For Formula 1, the goal was to maximize tensile strength while maintaining target values for elongation and biodegradability. Formula 2 prioritized maximum tensile strength and biodegradability while minimizing elongation. Lastly, Formula 3 aimed to maximize all three properties: tensile strength, elongation, and biodegradability. These optimization goals were aligned with the requirements of food packaging applications, which demand high mechanical strength. Subsequent verification experiments, whose results are presented in

Table 5, demonstrated close agreement between predicted and experimental values.

Figure 5.

The appearance of 0,7,15 and 30-day degradation of the composite films.

Figure 5.

The appearance of 0,7,15 and 30-day degradation of the composite films.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the potential of cassava starch-based biodegradable films incorporated with onion peel powder (OPP) for enhancing mechanical properties and biodegradability. The formulations optimized via Central Composite Design (CCD) show promising properties for sustainable food packaging applications. The characterization of OPP revealed that its chemical composition and bioactive properties, particularly its flavonoid content, significantly influence the mechanical and biodegradability properties of the films. Several studies have highlighted the advantages of incorporating plant-based fillers, such as onion peel, into biodegradable films. For instance, Bayram et al. [

21], explored the use of fruit and vegetable waste as fillers in biodegradable films and found that the incorporation of bioactive compounds from agricultural waste enhanced both the mechanical strength and antioxidant properties of the films. This is consistent with our findings, where the OPP added to the cassava starch matrix improved the tensile strength while maintaining an optimal balance with elongation and biodegradability. The antioxidant activity attributed to the flavonoid compounds, notably quercetin, found in onion peel [

22], likely contributed to the improved properties of the films, as it is known that antioxidants can also influence the degradation process by interacting with environmental factors such as light and moisture. Furthermore, the results of this study are in line with the work of Ali et al. [

23], who investigated the biodegradability of starch-based films and reported that the inclusion of natural fillers, such as plant powders, accelerated the biodegradation process due to the enhanced microbial activity. The biodegradation rates observed in our study, with weight loss percentages of 31.86%, 29.12%, and 29.02% for the optimized formulations, are comparable to those reported previous Malachovskienė et al. [

24] and Malekzadeh et al. [

25], where films containing natural fillers showed similar levels of degradation within a similar soil burial period. These findings suggest that the OPP not only improves the mechanical properties of the films but also contributes to their environmentally friendly decomposition, a crucial factor for sustainable packaging. The role of the onion peel powder in improving both the mechanical and biodegradability properties of the films may be attributed to its rich phytochemical profile. As demonstrated by our characterization data obtained via UHPLC/MS, the onion peel powder used in this study contains significant amounts of flavonoids and phenolic compounds, which have been shown to act as plasticizers in biopolymer matrices Maryuni et al. [

26]. These compounds may not only contribute to the films’ mechanical performance but also play a role in facilitating microbial degradation, which is a critical aspect for bioplastics intended for environmental applications. In addition, the optimization process used in this study, based on the Central Composite Design (CCD), allowed for the identification of formulations that strike an ideal balance between mechanical strength and biodegradability. The outcomes of this study are consistent with the findings of Rocha Gomes et al. [

27] and Tafa et al. [

28], who also utilized CCD to optimize the properties of bioplastics. The use of statistical design in bioplastic research is becoming increasingly important for the development of high-performance, sustainable materials. However, it is important to note that while the formulations developed in this study exhibit promising properties, further research is needed to explore their performance under real-world conditions, including food contact applications, to better understand their long-term stability and safety.

5. Conclusion

Biodegradable plastics based on cassava starch and onion peel powder (OPP) were successfully synthesized using the casting method. The formulation was optimized using Minitab 19 software to achieve favorable mechanical properties—tensile strength, elongation at break,and biodegradability. Experimental validation showed strong agreement between predicted and observed values, confirming the model’s reliability in determining optimal formulation parameters. These results highlight the potential of cassava starch/OPP-based bioplastics as promising sustainable alternatives to conventional plastics, particularly for packaging applications. One limitation of this study is the focus on specific ratios of cassava starch and OPP, without exploring other variations in composition, such as the inclusion of additional biopolymers or reinforcement materials, which could further enhance the properties of the bioplastics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T., and L.R.; methodology, A.T. F.D., and I.S.; software, A.T., T.C., and M.D.E.; validation, A.T., T.C., R.A., and L.R.; formal analysis, A.T., T.C., F.D., I.S. R.A., and M.D.E.; investigation, A.T., T.C., F.D., I.S. R.A., and M.D.E; resources, L.R.; data curation, A.T., T.C., F.D., I.S. R.A., and M.D.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T., M.D.E. and L.R.; writing—review and editing, A.T., M.D.E. and L.R.; visualization, T.C.; supervision, L.R.; project administration, L.R.; funding acquisition, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the doctoral thesis research of Assala Torche at Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, Kasdi Merbah University, 30000, Ouargla, Algeria. The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Algeria is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Krishnamurthy, A.; Amritkumar, P. Synthesis and characterization of eco-friendly bioplastic from low-cost plant resources. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkoula, N.M.; Alcock, B.; Cabrera, N.O.; Peijs, T. Flame-Retardancy Properties of Intumescent Ammonium Poly(Phosphate) and Mineral Filler Magnesium Hydroxide in Combination with Graphene. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2008, 16, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Alemzadeh, I.; Vossoughi, M. Functional properties of biodegradable corn starch nanocomposites for food packaging applications. Mater. Des. 2013, 50, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celano, R.; Docimo, T.; Piccinelli, A.L.; Gazzerro, P.; Tucci, M.; Di Sanzo, R.; Carabetta, S.; Campone, L.; Russo, M.; Rastrelli, L. Onion peel: Turning a food waste into a resource. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, M.; Joseph, J.; Selvaraj, T.; Sivakumar, D. Application of desirability-function and RSM to optimise the multi-objectives while turning Inconel 718 using coated carbide tools. Int. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2013, 27, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.G.; Silva, G.F.A.; Gomes, B.M.; Martins, V.G. A novel sodium alginate active films functionalized with purple onion peel extract (Allium cepa). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, S.; Baniasadi, H. Investigation the effect of graphene oxide and gelatin/starch weight ratio on the properties of starch/gelatin/GO nanocomposite films: The RSM study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechichian, V.; Ditchfield, C.; Veiga-Santos, P.; Tadini, C.C. Natural antimicrobial ingredients incorporated in biodegradable films based on cassava starch. Lwt 2010, 43, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Caetano, K.; Almeida Lopes, N.; Haas Costa, T.M.; Brandelli, A.; Rodrigues, E.; Hickmann Flôres, S.; Cladera-Olivera, F. Characterization of active biodegradable films based on cassava starch and natural compounds. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasem odhaib, A.; Pirsa, S.; Mohtarami, F. Biodegradable film based on barley sprout powder/pectin modified with quercetin and V2O5 nanoparticles: Investigation of physicochemical and structural properties. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, N.; Alnemr, T.; Ali, S. Development of low-cost biodegradable films from corn starch and date palm pits (Phoenix dactylifera). Food Biosci. 2021, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyubi, S.N.; Purbasari, A. ; Kusmiyati The effect of composition on mechanical properties of biodegradable plastic based on chitosan/cassava starch/PVA/crude glycerol: Optimization of the composition using Box Behnken Design. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 63, S78–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilah, A.N.; Jamilah, B.; Noranizan, M.A.; Hanani, Z.A.N. Utilization of mango peel extracts on the biodegradable films for active packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeros-Hernandez, D.; Medina-Jaramillo, C.; López-Córdoba, A.; Goyanes, S. Edible cassava starch films carrying rosemary antioxidant extracts for potential use as active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 63, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osojnik Črnivec, I.G.; Skrt, M.; Šeremet, D.; Sterniša, M.; Farčnik, D.; Štrumbelj, E.; Poljanšek, A.; Cebin, N.; Pogačnik, L.; Smole Možina, S.; et al. Waste streams in onion production: Bioactive compounds, quercetin and use of antimicrobial and antioxidative properties. Waste Manag. 2021, 126, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, M.R.; Barros, T.T.; De Moura, M.R.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Assis, O.B.G. Effect of Chitosan Nanoparticles and Pectin Content on Mechanical Properties and Water Vapor Permeability of Banana Puree Films. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, B.; Cui, M.; Li, Y. Effect of KNbO3 content on crystal structure and electrical properties. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2013, 4, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Bastida, C.A.; Flores-Huicochea, E.; Martin-Polo, M.O.; Velazquez, G.; Torres, J.A. Compositional and Moisture Content Effects on the Biodegradability of Zein/Ethylcellulose Films. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4038–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, F.G.; Troncoso, O.P.; Torres, C.; Díaz, D.A.; Amaya, E. Biodegradability and mechanical properties of starch films from Andean crops. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 48, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hun, J.H.; Cennadios, A. Edible Films and Coatings: a review. Innov. Food Packag. 2005, 239–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, B.; Ozkan, G.; Kostka, T.; Capanoglu, E.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Valorization and application of fruit and vegetable wastes and by-products for food packaging materials. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joković, N.; Matejić, J.; Zvezdanović, J.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.; Stanković, N.; Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Bernstein, N. Onion Peel as a Potential Source of Antioxidants and Antimicrobial Agents. Agronomy 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Basit, A.; Hussain, A.; Sammi, S.; Wali, A.; Goksen, G.; Muhammad, A.; Faiz, F.; Trif, M.; Rusu, A.; et al. Starch-based environment friendly, edible and antimicrobial films reinforced with medicinal plants. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malachovskienė, E.; Bridžiuvienė, D.; Ostrauskaitė, J.; Vaičekauskaitė, J.; Žalūdienė, G. A Comparative Investigation of the Biodegradation Behaviour of Linseed Oil-Based Cross-Linked Composites Filled with Industrial Waste Materials in Two Different Soils. J. Renew. Mater. 2023, 11, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, E.; Tatari, A.; Dehghani Firouzabadi, M. Effects of biodegradation of starch-nanocellulose films incorporated with black tea extract on soil quality. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryuni, D.R.; Prameswari, D.A.; Astari, S.D.; Sari, S.P.; Putri, D.N. Identification of active compounds in red onion (Allium ascalonicum) peel extract by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS and determination of its antioxidant activity. J. Teknol. Has. Pertan. 2022, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha Gomes, Á.V.; De Lima Leite, R.H.; Da Silva Júnior, M.Q.; Gomes Dos Santos, F.K.; Mendes Aroucha, E.M. Influence of composition on mechanical properties of cassava starch, sisal fiber and carnauba wax biocomposites. Mater. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafa, K.D.; Satheesh, N.; Abera, W. Mechanical properties of tef starch based edible films: Development and process optimization. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).