1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been associated with a wide spectrum of complications, ranging from respiratory failure and multiorgan involvement to autoimmune phenomena [

1]. Among the less common but increasingly recognized manifestations are COVID-19–induced or -associated myopathies, typically presenting with muscle pain, weakness, and elevated muscle enzyme levels [

1,

2].

The underlying pathogenesis appears multifactorial, however; immune dysregulation and infection-triggered autoimmunity are thought to play a central role, as illustrated by reports of new-onset dermatomyositis and necrotizing autoimmune myopathy following SARS-CoV-2 infection [

1,

2]. Similar cases have also been described after COVID-19 vaccination, suggesting that both natural infection and vaccine-induced immune activation may precipitate clinically significant muscle disease [

3]. Direct viral injury has also been proposed. Muscle biopsy studies have revealed myofiber necrosis with limited inflammation and occasional viral particles, consistent with a combination of direct cytopathic effects and secondary immune-mediated damage[

4]. Taken together, these findings suggest that COVID-19–associated myopathy exists along a clinical spectrum, from mild, self-limiting muscle involvement to severe immune-mediated inflammatory myositis [

5]. However, diagnosis and management of such cases remain clinically challenging.

Diagnosis of such cases is clinically important, as they can mimic primary autoimmune myopathies but often follow a distinct course and prognosis. By presenting this case, we aim to contribute to the growing body of evidence, highlight the diagnostic challenges, and support clinicians in managing this rare but relevant complication.

2. Case Presentation

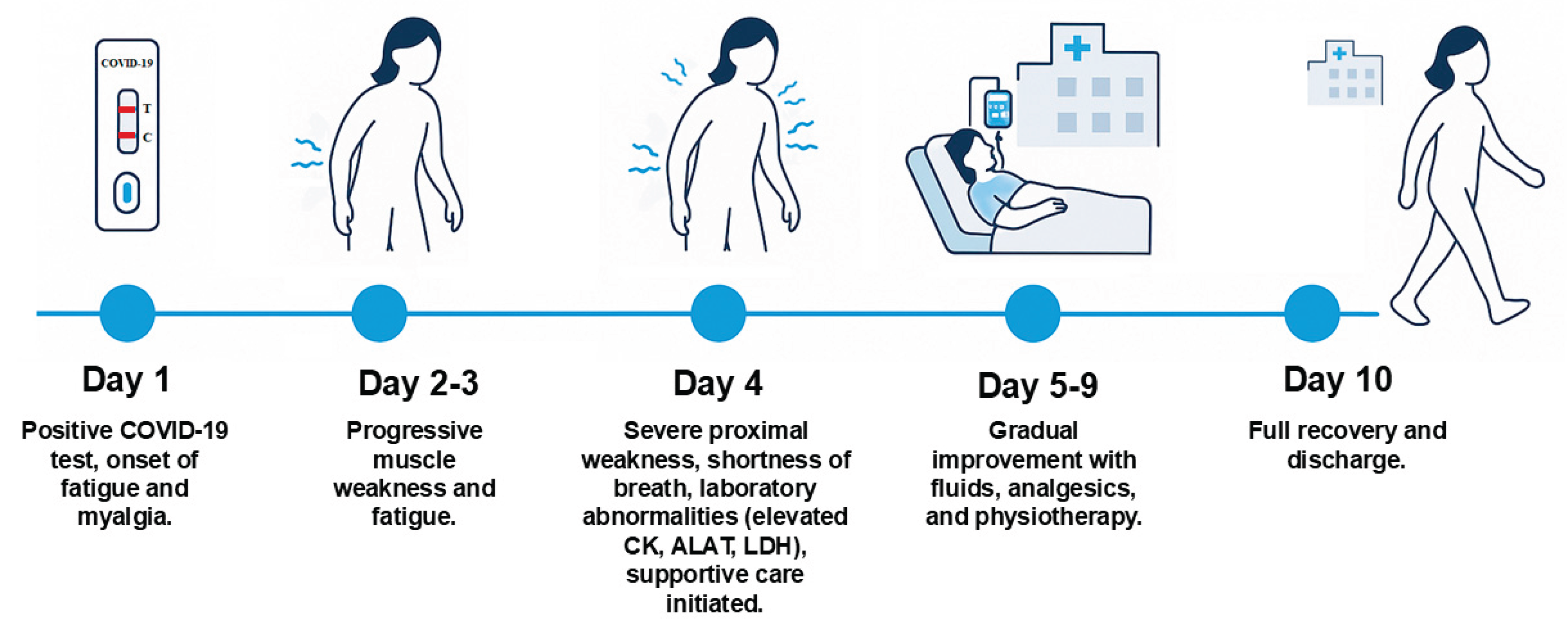

The patient was a 59-year-old woman, previously healthy and physically active, with no history of regular medication use, herbal remedies, or family history of neuromuscular disease. She developed upper respiratory tract symptoms and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 using a home using a rapid antigen test. Shortly thereafter, she developed progressive fatigue, diffuse myalgia, dyspnea on exertion, dizziness, and difficulty performing fine motor tasks such as writing and using a phone. She also reported urinary incontinence.

Over the next few days, her muscle weakness worsened. On day 4, she presented to acute department of our hospital with difficulty standing from a chair, climbing stairs, and carrying objects, accompanied by shortness of breath. On examination, she was alert and oriented, with normal vital signs apart from tachycardia. Physical examinations revealed diffuse muscle tenderness and pronounced proximal weakness in both upper and lower extremities, while reflexes and sensation remained intact. The patient had received four doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the last administered one year before admission.

Laboratory tests confirmed COVID-19 and demonstrated elevated CK (1,370 U/L), ALT (239 U/L), and LDH (616 U/L) (

Table 1). Lumbar puncture was unremarkable, with no signs of inflammation or protein elevation. Chest X-ray had no remarkable change and ECG showed sinus tachycardia (

Figure 1).

The differential diagnoses considered included Guillain–Barré syndrome (excluded by preserved reflexes and normal cerebrospinal fluid), transverse myelitis (excluded by normal cerebrospinal fluid and absence of upper motor neuron signs), medication-induced myopathy such as statin or corticosteroid-related (excluded due to absence of relevant drug exposure), and autoimmune inflammatory myopathies (excluded by negative autoantibody testing and lack of characteristic features).

A multidisciplinary team of infectious disease specialists, neurologists, and rheumatologists concluded that the patient had acute post-viral myopathy secondary to COVID-19. Management included intravenous fluids (a total of 3 liters comprising normal saline and Ringer’s lactate during admission), analgesia with paracetamol 1 g four times daily and ibuprofen 400 mg three times daily, and initiation of early physiotherapy. Her symptoms gradually improved, with resolution of myalgia and restoration of muscle strength within one week. By day 10, she was discharged in near-complete recovery and able to resume her daily activities (

Figure 2).

The patient was followed for 6 months. She returned to work and resumed horse riding 4–5 times per week, as well as fitness training 3 times per week.

3. Discussion

Viral infections have long been recognized as triggers of acute myopathies and Influenza A and B, Enteroviruses such as Coxsackievirus and Echovirus, HIV, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and parvovirus B19 are known causes of viral associated myopathies [

6]. These precedents highlight that SARS-CoV-2 fits into a broader pattern of viral agents capable of inducing muscle disease [

7].

COVID-19-associated myopathy has been described in several forms, including dermatomyositis [

1], autoimmune necrotizing myositis [

2], and post-vaccination myositis [

3]. These heterogeneous presentations suggest complex mechanisms involving immune dysregulation, cytokine-mediated muscle damage, microvascular injury, and possibly direct viral invasion [

3]. Histopathological studies have demonstrated myofiber necrosis, perivascular inflammation, and capillary injury in affected patients [

4], supporting this multifactorial pathogenesis.

The clinical spectrum ranges from severe immune-mediated myopathies requiring immunosuppressive treatment to mild, self-limiting viral myositis that responds to supportive care. [

1,

2] Our case belongs to the latter category, with acute but transient muscle weakness, elevated LDH and myoglobin, and full recovery after intravenous fluids, analgesics, and physiotherapy. Importantly, preserved reflexes, normal cerebrospinal fluid, and absence of sensory deficits helped exclude Guillain–Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, and other neuropathic processes. The autoantibody panel was negative for myositis-specific and myositis-associated antibodies, except for an isolated positivity for chromodomain-helicase-DNA (CHD4, anti-Mi-2). While anti-Mi-2 is typically linked to dermatomyositis with characteristic cutaneous features, these were absent, and the short, self-limiting clinical course contrasted with the chronic autoimmune pattern usually associated with dermatomyositis. In a published case, Plavsic et al. described a 36-year-old woman who developed severe autoimmune myopathy after COVID-19 pneumonia, with markedly elevated CK, persistent anti-Mi-2 and anti-Ro52 positivity, and a chronic course requiring corticosteroids, methotrexate, and intravenous immunoglobulin [

8]. Taken together, these cases highlight the heterogeneity of COVID-19–associated muscle involvement, ranging from transient viral-induced myopathy to persistent autoimmune disease.

In our case, the advanced diagnostic tools such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electromyography (EMG), or muscle biopsy were not performed, because the clinical and laboratory features were sufficient to establish the diagnosis. This pragmatic approach reflects real-world settings, where extensive neuromuscular workup may not be required if the clinical course is benign and self-limiting.

4. Conclusions

Although rare, COVID-19 can lead to acute myopathy even in individuals with no prior neuromuscular disease. This case illustrates the importance of clinical recognition, exclusion of alternative diagnoses, and the potential for full recovery with supportive therapy. Clinicians should remain alert to muscular manifestations of COVID-19, particularly when patients present with unexplained muscle weakness and pain during or shortly after infection. Furthermore, viral infections, including COVID-19, should be considered as differential diagnosis when patients present with signs and symptoms of myopathy. Sharing such experiences broadens awareness, facilitates timely diagnosis, and may improve outcomes in future patients.

Author Contributions

RAK and AA drafted, finalized, read and agreed to the published version of the case report.

Funding

RAK and AA received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All data are reported here. Further information can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Casper Roed and Omid Rezahosseini for their valuable guidance and support in the preparation of this case report. Their expertise and constructive feedback greatly contributed to the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ALT/ALAT: Alanine aminotransferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; CBC: Complete blood count; CHD4: Chromodomain-helicase-DNA (anti-Mi-2 antibody); CK: Creatine kinase; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid; dL: Deciliter; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; ECG: Electrocardiogram; EMG: Electromyography; g/L: Gram per liter; g/dL: Gram per deciliter; HMG-CoA: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; IU/L: International unit per liter; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; L/L: Liter per liter; mg/dL: Milligram per deciliter; mmol/L: Millimole per liter; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; µg/L: Microgram per liter; µL: Microliter; PCNA: Proliferating cell nuclear antigen; PM-Scl: Polymyositis/scleroderma autoantigen; RBC: Red blood cells; RNA: Ribonucleic acid; SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; Scl-70: DNA topoisomerase I autoantibody; SRP: Signal recognition particle; SSA/SSB: Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A/B; TSH: Thyroid-stimulating hormone; U/L: Unit per liter; WBC: White blood cells

References

- Shimizu, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Sasajima, T.; Suzuki, T.; Okubo, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Temmoku, J.; Yoshida, S.; Asano, T.; Ohira, H.; et al. New-Onset Dermatomyositis Following COVID-19: A Case Report. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veyseh, M.; Koyoda, S.; Ayesha, B. COVID-19 IgG-Related Autoimmune Inflammatory Necrotizing Myositis. BMJ Case Rep 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, J.E.; Uner, M.; Priemer, D.S.; Rosenberg, A.; Chen, L. Muscle Biopsy Findings in a Case of SARS-CoV-2-Associated Muscle Injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2021, 80, 377–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, I.R.B.; Rodrigues, T.C.; Skaf, A.Y. Bilateral Upper Extremity Myositis after COVID-19 Vaccination. BJR|case reports 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, J.; Amato, A.A. Neuromuscular Complications of Coronavirus Disease-19. Curr Opin Neurol 2021, 34, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, B.L.; Cristopher-Stine, L. Triggers of Inflammatory Myopathy: Insights into Pathogenesis.

- Dalakas, M.C. Inflammatory Myopathies: Update on Diagnosis, Pathogenesis and Therapies, and COVID-19-Related Implications. Acta Myologica 2020, 39, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plavsic, A.; Arandjelovic, S.; Popadic, A.P.; Bolpacic, J.; Raskovic, S.; Miskovic, R. SARS-CoV-2–Associated Myopathy with Positive Anti–Mi-2 Antibodies: A Case Report. Hong Kong Medical Journal 2023, 29, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).