1. Introduction

Migrant children(MC) refer to rural-to-urban migrants who have lived with their parents in destination cities for at least six months(Han et al., 2020). China's 2020 census data reveals 71.09 million migrant children nationwide, including 51.55 million school-aged children (primary to high school), representing 17.32% of the nation's child population(Zhenwu & Wenli, 2021). For these children, schools constitute both educational institutions and vital socialization platforms for urban integration. Transitioning to new educational settings typically involves dual adjustment challenges: rebuilding school-based social networks (teacher-peer relationships) while adjusting to unfamiliar pedagogical approaches, curricula, and campus cultures. This complex adjustment process results in significantly higher maladjustment risks among migrant children versus local students.

School adjustment(SA) refers to students' successful integration into academic and social aspects of school life, including active engagement, developmental progress, and academic achievement(Ladd et al., 1997). Research consistently shows migrant children face greater school adjustment challenges, particularly in academic performance and peer relationships(Gannon et al., 2023; Winsper et al., 2016). These difficulties significantly impact their overall well-being, with studies confirming school adjustment as a strong predictor of mental health outcomes(Arslan & Allen, 2022; Chen et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024).

This issue is especially critical during middle school years when adolescents experience rapid physical and psychological changes while adapting to urban environments(Yu et al., 2024). Inadequate school adjustment during this sensitive period may lead to academic struggles, emotional distress, and long-term consequences for social functioning and life satisfaction. The present study investigates school adjustment mechanisms among migrant middle school students to develop effective support strategies.

According to ecological systems theory, individual development is shaped through dynamic interactions with environmental systems, wherein the family constitutes the primary microsystem that exerts profound influence on migrant children's psychosocial and behavioral development(Wertsch, 2005). Empirical evidence has consistently demonstrated that migrant children's school adjustment disorders has stemmed from cumulative family risk factors(CFR)(Lynn, 2022), particularly parental divorce, financial hardship, and dysfunctional parent-child relationships(Boele et al., 2020; He & Xiao-Yang, 2022; Tetzner & Becker, 2015). Such adversities have elevated children's vulnerability to maladaptive outcomes(Wertsch, 2005). Nevertheless, existing research has predominantly examined isolated family risks, while the compounding effects of multiple familial risk factors have remained understudied. Notably, children exposed to co-occurring risks have demonstrated significantly higher susceptibility to adjustment disorders compared to those facing single risk factors(Ashworth & Humphrey, 2020; Yang et al., 2023).

Empirical studies highlight the crucial importance of examining the cumulative effects of multiple risk factors on migrant children's school adjustment. Addy et al. found that approximately 41% of children face 1-2 family risk factors, while up to 20% are exposed to 3 or more compounding risks(Jiang et al., 2017). Notably, migrant children as a vulnerable group experience significantly higher cumulative risk exposure than their non-migrant peers(Gatt et al., 2020), which may exert multiplicative negative effects on their school adjustment(Yang & Maguire-Jack, 2018).

The cumulative risk model provides a theoretical framework for understanding this phenomenon, emphasizing that the accumulation of risk factors is more predictive of child development outcomes than any single risk(Evans et al., 2013). Operationally, the model employs a dichotomous scoring method (risk present=1, no risk=0) to construct a cumulative risk index through simple summation. This concise yet effective assessment method demonstrates strong feasibility and shows good predictive validity in vulnerable population studies(Appleyard et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2023).

Relative deprivation(RD) refers to the subjective cognitive-emotional experience where individuals or groups perceive themselves to be at a disadvantage compared to reference groups, resulting in negative emotions like resentment and dissatisfaction(XIONG & YE, 2016). Research has shown that exposure to environmental risk factors such as low family socioeconomic status and limited parental education has increased susceptibility to relative deprivation(Wang & Meng, 2024; Ye & Xiong, 2017). For migrant children whose parents are typically rural laborers engaged in unstable, low-paying jobs, this socioeconomic disadvantage fosters strong perceptions of rights deprivation when comparing themselves to urban peers(Zhang & Tao, 2013).

Relative deprivation theory posits that risk exposure triggers relative deprivation through perceived benefit loss, impairing adjustment(Smith et al., 2012; Wickham et al., 2013). Callan et al. found relative deprivation mediates the family economic risk-adjustment link,exacerbating hardship's negative effects(Callan et al., 2017). Zhang and Tao's longitudinal data showed deprivation intensity predicts adjustment decline(Zhang & Tao, 2013). Therefore, when individuals experience multiple concurrent risk factors, their combined effects may significantly strengthen the intensity of relative deprivation, thereby producing more persistent negative impacts on adjustment levels(Ohno et al., 2023).

Notably, many migrant children have demonstrated remarkable psychological resilience and achieved positive adjustment despite facing multiple risk factors(Mou et al., 2013). According to cognitive adaptation theory(Taylor, 1983), individuals actively employ psychological strategies to mitigate risks, with beliefs about adversity serving as a crucial protective mechanism in this adaptive process(Shek et al., 2003). Beliefs about adversity(BA) reflect an individual's cognitive appraisal of hardship, encompassing its perceived causes, consequences, and coping methods(Shek, 2005). Those with positive beliefs about adversity tend to view challenges as manageable ("Hardship cultivates growth") rather than insurmountable threats, thereby bolstering resilience and adaptability(Shek, 2004).

Research has confirmed that strong beliefs about adversity buffer against risk factors' harmful effects, promoting psychological adjustment(Callan et al., 2015; Liu & Wang, 2018; Zhao et al., 2013). Specifically, these beliefs mitigate socioeconomic stressors (e.g., financial strain) and parent-child conflicts' negative impacts on adolescents' mental health, reducing depression and behavioral issues(Li et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2021). Additionally, they enhance children's well-being and life satisfaction(Shek, 2004; Zhao et al., 2017). For migrant children, such beliefs are vital: they foster adaptive cognition and emotional regulation. Particularly for those facing multiple risks, positive beliefs about adversity enable realistic adversity appraisal while boosting emotional control, enhancing overall coping ability.

While prior research has explored links between cumulative family risks, relative deprivation, beliefs about adversity , and adjustment, critical gaps persist. First, no study has systematically examined how cumulative family risks affect migrant children's school adjustment. Existing work focuses on single risk factors (e.g., financial stress, parent-child conflict)(Martinez-Escudero et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022), neglecting their combined effects. Second, although school environment risks (e.g., poor teacher-student relations, peer rejection) are well-studied(Pu et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2022), how family risks (e.g., poverty, parental separation) impact school adjustment remains unclear.

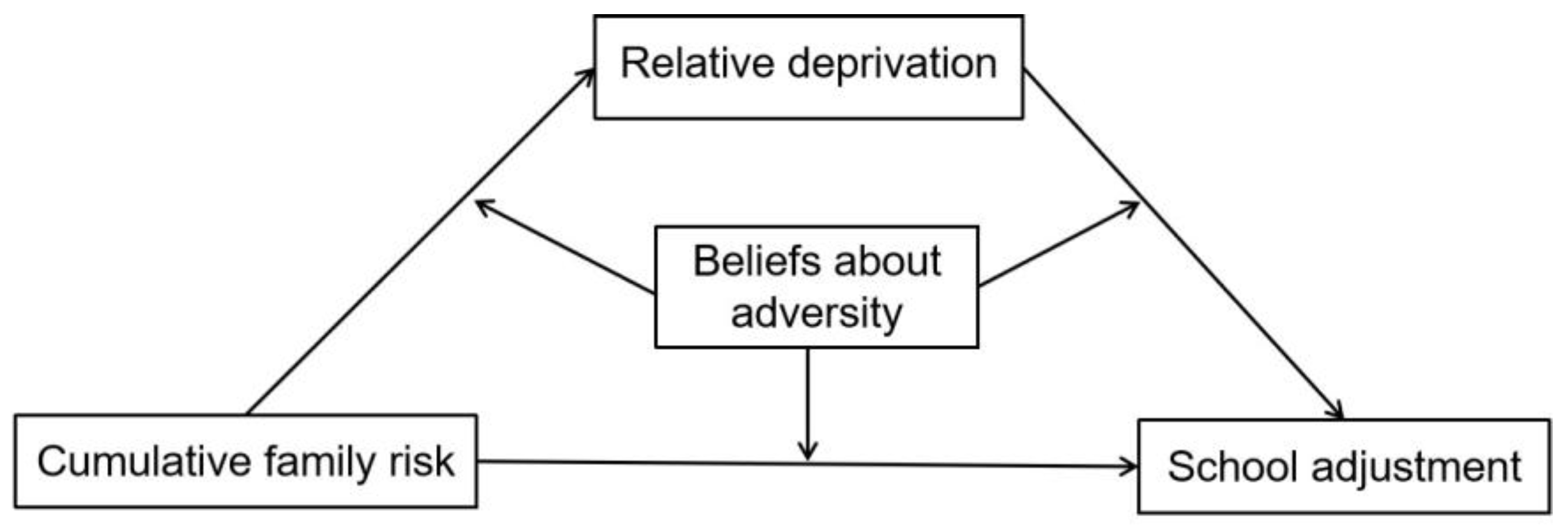

Based on the cumulative risk model, relative deprivation theory, and cognitive adaptation theory, this study employs a moderated mediation model to systematically explore the psychological mechanisms through which cumulative family risks influence migrant children's school adjustment(see

Figure 1). the study tests three key hypotheses:

H1: Cumulative family risk negatively predict migrant children's school adjustment.

H2: Relative deprivation would mediate the correlation between Cumulative family risks and negative risk-taking behaviors of migrant children's school adjustment.

H3: Beliefs about adversity would moderate the whole effect paths of cumulative family risk on school adjustment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study was conducted in three middle schools located in Yancheng and Zhenjiang cities, both of which are economically developed coastal cities in eastern China with significant populations of migrant children. From an initial pool of 2,591 collected questionnaires, we excluded 93 due to missing data, resulting in a total of 2,498 valid responses, reflecting a retention rate of 96.41%. Our final analytical sample included 1,128 migrant children (M_age = 12.83 ± 1.21 years), with a balanced gender representation (576 boys, M_age = 13.16 ± 1.12; 552 girls, M_age = 12.48 ± 1.25) and grade distribution (641 seventh-graders and 487 eighth-graders). All study procedures received ethical approval from our institutional review board, and the questionnaires were administered during regular class periods with authorization from the schools.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Cumulative Family Risk

This research examined seven possible family risk factors, assigning a code of “0” to indicate absence and "1" to denote presence of risk. The specifics of coding and assessment were outlined as follows: (1) Family structure: coded “0” when both biological parents are present, and “1” for any other family arrangements. (2) Educational attainment of parents: coded “1” if neither parent had finished high school. (3) Parent-child separation: designated “1” if one or both parents were away due to work or other migration within the previous six months; presence of both parents was coded as “0.” For continuous measures, scores that were at or above the 75th percentile of the overall scale score were classified as “1” (at risk), while scores falling below this level were classified as “0” (no risk). This coding system applies to: (4) Family economic strain : evaluated by a 4-item scale adapted from Wadsworth et al(Wadsworth & Compas, 2002), concentrating on difficulties in covering expenses related to clothing, food, housing, and transportation. Participants responded on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always), and the reliability of the scale was strong, indicated by a Cronbach’s α of 0.91. (5) Family cohesion : assessed by the cohesion subscale of the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale (FACES Ⅱ)(Olson et al., 1983). In this study, to ensure consistency, the scoring was reversed, with higher scores indicating lower levels of cohesion, subsequently categorized as 'low family cohesion.' Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s α for this study was 0.88. (6) parent-child cohesion: The evaluation was conducted using a 20-item scale adapted from Zhang et al(Wenxin et al., 2006). This questionnaire comprises two subscales: paternal cohesion and maternal cohesion. A low score on either subscale indicates the presence of one family risk factor, while a low score on both subscales signifies the existence of two family risk factors. Responses were recorded on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s α for this study was 0.92.

2.2.2. Relative Deprivation

The relative deprivation of adolescents was measured using the Relative Deprivation Scale developed by Ma(Ma, 2012). This 4-item scale assesses adolescents' feelings and experiences regarding their perception of relative deprivation (e.g., "I often feel that others have obtained what rightfully belongs to me"). Each item is rated on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree). This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous studies with Chinese children(Xie et al., 2025). The Cronbach's α for this study was 0.78.

2.2.3. School Adjustment

School adjustment was assessed using the School adjustment Scale developed by Cui(Cui, 2008). This 27-item scale evaluates adolescent school adjustment across several dimensions, including academic adjustment (e.g., "I often find myself distracted while studying"), emotional and attitudinal responses towards school (e.g., "I hate going to school"), peer relationships (e.g., "My classmates don't like me"), teacher-student relationships (e.g., "I am very afraid of my teachers"), and routine adjustment (e.g., "Some of the school rules make me feel uncomfortable").The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous studies with Chinese children(Tiangui et al., 2024). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach's α for this study was 0.90.

2.2.4. Beliefs About Adversity

Beliefs about adversity were assessed using the Beliefs about Adversity Scale developed by Shek(Shek, 2005). This 9-item scale evaluates adolescents' positive beliefs when confronting adversity (e.g., "where there is a will, there is a way"). Each item is rated on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous studies with Chinese children(Hayes, 2012). The cronbach's α for this study was 0.85.

2.3. Procedure

The present study received approval from our university's review board. Prior to the official research, verbal consent was obtained from the school administrators, educators, and students. The questionnaire survey took place in three urban schools, with all experimenters being psychology teachers and graduate students specializing in psychology. A group survey format was utilized for the participants, emphasizing voluntary participation, data confidentiality, and student anonymity. Participants were informed that they needed to respond independently based on their current circumstances.

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 27.0 along with the PROCESS macro. First, the dataset underwent descriptive statistics and correlation analysis in SPSS 27.0. Second, the mediating influence of relative deprivation on the link between cumulative family risk and school adjustment was evaluated using the PROCESS macro's Model 4. Third, the moderating effect of Beliefs about adversity within this mediation process was explored, utilizing Model 59 of the PROCESS macro. Lastly, a simple slope test was executed to break down the significant moderation effect. Before assessing the mediating and moderating influences, all variables were standardized.

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

To mitigate common method bias, anonymous assessments and partially reversed scoring for some questions were implemented to regulate the testing procedure. In the analysis phase, Harman’s single-factor test was applied. Findings revealed that there were 27 factors with eigenvalues exceeding one, with the initial principal factor accounting for 24.68% of the variance (less than 40%), indicating that the current study did not exhibit significant common method bias.

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and correlations among the primary study variables. Cumulative family risk exhibited a significant positive correlation with relative deprivation, while showing a significant negative correlation with both school adjustment and beliefs about adversity. Furthermore, relative deprivation was significantly negatively correlated with both school adjustment and beliefs about adversity. In contrast, school adjustment demonstrated a significant positive correlation with beliefs about adversity.

3.3. Testing for the Mediating Role of Relative Deprivation

In Hypothesis 2, we anticipated that relative deprivation would mediate the relationship between cumulative family risk and school adjustment. We conducted the mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro (Model 4). After controlling for migrant children’s gender and age, cumulative family risk was positively associated with relative deprivation (β=0.28, p<.001), which, in turn, negatively affected school adjustment (β=-0.15, p<.001)(see

Table 2). Additionally, the residual direct effect was significant (β = -0.17, p < .001, bootstrap 95% CI [-0.20, -0.15]), indicating that relative deprivation mediated the relationship between cumulative family risk and school adjustment (indirect effect = -0.04, bootstrap 95% CI [-0.06, -0.03]) (see

Table 3). The mediating effect accounted for 19.76% of the total effect of cumulative family risk on school adjustment.

3.4. Testing for Moderated Mediation

Next, we estimated the moderating role of beliefs about adversity in the relationship between relative deprivation and school adjustment. We employed Model 59 from the PROCESS macro to investigate the moderating effect of beliefs about adversity(Hayes, 2012). As shown in

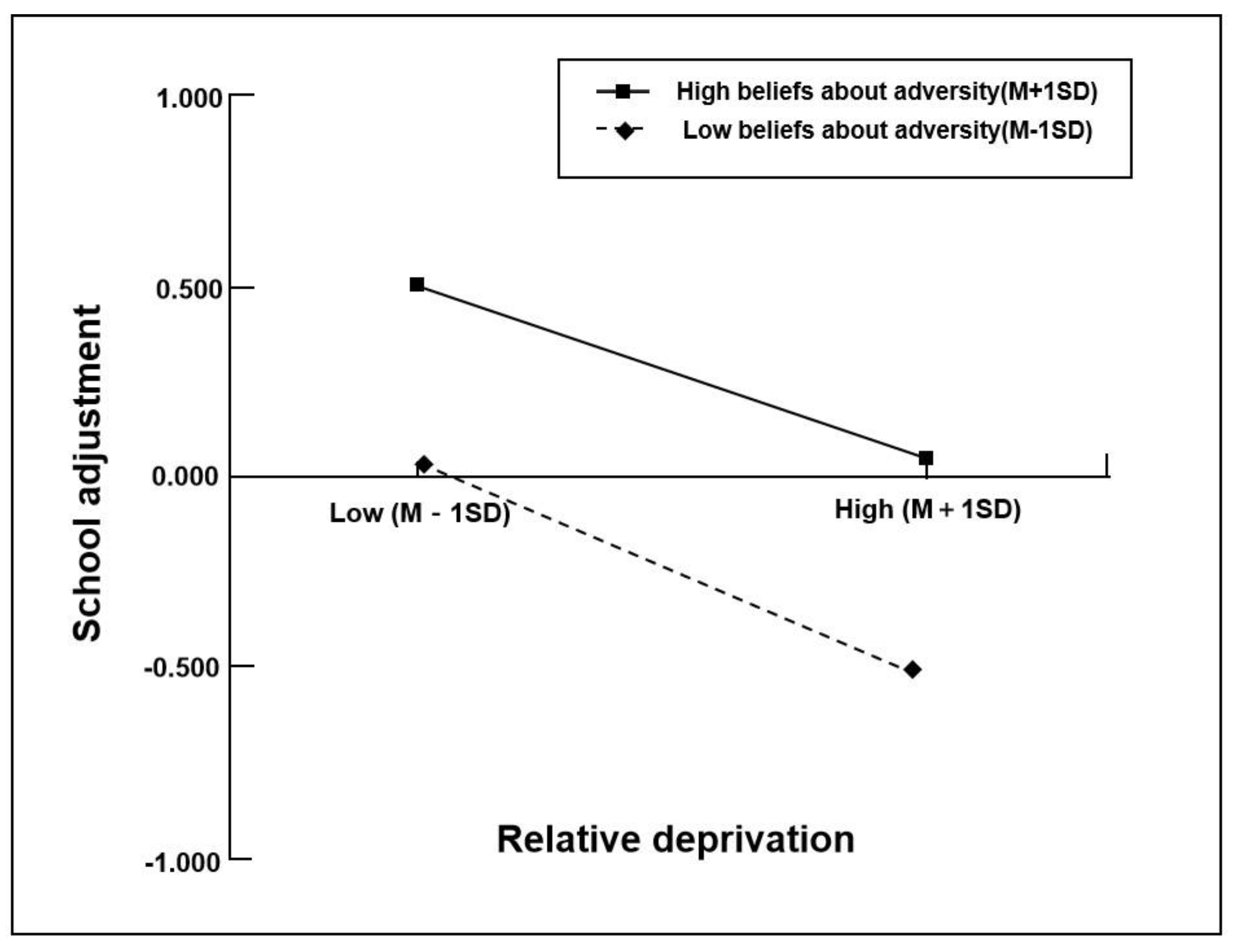

Table 4, after controlling for gender and age, the interaction term between CFR and BA not significantly predicted the relative deprivation and school adjustment(β=0.03, p>0.05, bootstrap 95% CI [-0.02, 0.08]; β = -0.01, p>0.05, bootstrap 95% CI [-0.03, 0.02), the interaction term between RD and BA significantly predicted the school adjustment (β = 0.05, p < .05, bootstrap 95% CI [0.01, 0.08]).

The simple slopes analysis revealed that for migrant children with weaker beliefs about adversity (M-1SD), higher levels of relative deprivation were associated with lower levels of school adjustment (βsimple = -0.30, p < .001). Conversely, for migrant children with stronger beliefs about adversity (M+1SD), the effect of relative deprivation on school adjustment was significantly weaker (βsimple = -0.21, p < .001) (see

Figure 2). Thus, relative deprivation emerged as a much stronger predictor of school adjustment for migrant children with lower levels of beliefs about adversity, aligning with the stress-buffering model.

4. Discussion

The current study provides evidence that the negative association between cumulative family risk and school adjustment is mediated by relative deprivation, and that this direct effect is moderated by beliefs about adversity. The major contribution of the present study is that it deepens our understanding of how cumulative family risk is associated with migrant children's school adjustment. Furthermore, the complex moderated mediation model offers insights for potential prevention and intervention programs aimed at reducing migrant children's school adjustment problems.

Our findings indicate that cumulative family risk is significantly associated with the school adjustment of migrant children, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. This result suggests that cumulative family risk serves as a critical risk factor influencing externalizing problem behaviors in migrant children, aligning with previous research and reinforcing the cumulative risk model(Evans et al., 2013; Kliewer et al., 2017). As Evans et al argue, exposure to multiple concurrent risk factors substantially increases the likelihood of adverse developmental outcomes in children(Evans et al., 2013). This effect is particularly salient among middle school-aged migrant children, a population undergoing a critical developmental transition. Within urban education systems, these children constitute a vulnerable group, confronting not only typical school adjustment challenges but also compounded socio-environmental stressors. When such risk factors accumulate and interact, their synergistic effects can significantly exacerbate difficulties in the school adjustment process.

The current study confirms that relative deprivation partially mediates the association between cumulative family risk and migrant children's school adjustment, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. The results indicate that cumulative family risk affects school adjustment through both direct pathways and those mediated by relative deprivation.

Specifically, the findings demonstrate that cumulative family risk significantly increases relative deprivation, aligning with previous studies and reinforcing parental relative deprivation theory(Pettigrew, 2016; Smith et al., 2012). Chronic exposure to multiple family risks leads to negative self-evaluations and perceived unfair disadvantages, which trigger feelings of relative deprivation(Pettigrew, 2016; Zhang et al., 2022). Notably, our observations of migrant children mirror established findings, showing that multi-factorial family risks consistently predict the emergence of relative deprivation(Pinchak & Swisher, 2022). Furthermore, the study establishes that relative deprivation significantly impairs migrant children's school adjustment, corroborating earlier findings(Keshavarz et al., 2021; Mishra & Carleton, 2015). This detrimental psychological state fosters perceptions of disadvantage through social comparisons, adversely affecting various domains of school adjustment. These results underscore the dual nature of adjustment mechanisms in novel educational settings: while cumulative risk factors remain crucial, equal consideration must be given to the mediating role of subjective psychological experiences in shaping adjustment outcomes.

The moderation analysis indicates that beliefs about adversity significantly moderate the relationship between relative deprivation and school adjustment, providing partial support for Research Hypothesis 3. Data analysis reveals that as migrant children's beliefs about adversity increase, the negative impact of relative deprivation on their school adjustment shows a significant weakening trend, which corresponds to previous studies and cognitive adaptation theory(Keshavarz et al., 2021) . As a positive psychological resource, beliefs about adversity enhance migrant children's optimism and psychological resilience(Mou et al., 2013), strengthen their belief in being masters of their own destiny, and enable them to actively seek value and meaning in adversity(Wang & Liu, 2023; Zhao et al., 2017). This transformation of unfavorable circumstances into motivation for personal development assists their adjustment to new school environments(Shek, 2004; Zhao et al., 2013).

Notably, the study found that beliefs about adversity did not significantly moderate the relationships between cumulative family risk and school adjustment or relative deprivation in migrant children. This non-significant result aligns with the dual-pathway theory of beliefs about adversity(Li et al., 2012), which identifies two patterns: (1) a "timely assistance" pattern where buffering effects strengthen with increasing risk severity, and (2) a "drop in the bucket" pattern where protection weakens as risks accumulate. Our findings supported the second pattern; under conditions of high cumulative risk, the buffering capacity of beliefs about adversity progressively diminished as risks compounded, ultimately proving insufficient to counteract the accumulated negative effects(Yang & Huang, 2020). This suggests a limited protective utility of these beliefs in contexts of extreme adversity.

This study investigates the relationship between cumulative family risk and school adjustment among migrant children, highlighting the mediating role of relative deprivation and the moderating role of beliefs about adversity. These findings provide empirical evidence for the development of prevention and intervention strategies aimed at high-risk migrant children facing difficulties in school adjustment. However, three main limitations should be acknowledged: First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to examine potential age-related variations in the effects of cumulative family risk; future longitudinal studies could better capture the dynamic nature of these effects over time. Second, while the seven selected family risk factors represent significant family risks, future research could broaden the scope by incorporating additional family risk factors (e.g., parental neglect) and ecological risk factors from school and community contexts, thereby providing a more comprehensive assessment of cumulative risk effects. Third, the scoring of four risk factors was based on the participants' relative standing within the sample, which may introduce sample-specific dependencies—a methodological challenge commonly encountered in cumulative risk model research(Appleyard et al., 2005). Consequently, caution is advised when generalizing these findings due to potential issues of sample homogeneity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F. and Z.Z.; methodology, S.F. and X.G.; formal analysis S.F.; investigation, S.F. and Z.Z.; writing-original draft preparation S.F.; writing-review and editing, S.F. and X.G.; supervision, S.F. and Z.Z.; project administration S.F.; funding acquisition, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province in 2024 grant number 24JYC002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Yancheng Teachers University (No. 2024040035: Date: 15 August 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. We obtained research consent from school leaders and head teachers, while ensuring parental informed consent for participants aged 15 years or younger.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by research fund of Jiangsu Provincial Key Constructive Laboratory for Big Data of Psychology and Cognitive Science.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Appleyard, K., Egeland, B., van Dulmen, M. H., & Alan Sroufe, L. (2005). When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 46(3), 235-245. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G., & Allen, K.-A. (2022). Complete mental health in elementary school children: Understanding youth school functioning and adjustment. Current Psychology, 41(3), 1174-1183. [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, E., & Humphrey, N. (2020). More than the sum of its parts: Cumulative risk effects on school functioning in middle childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90. [CrossRef]

- Boele, S., Denissen, J., Moopen, N., & Keijsers, L. (2020). Over-time fluctuations in parenting and adolescent adaptation within families: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 5(3), 317-339. [CrossRef]

- Callan, M. J., Kim, H., Gheorghiu, A. I., & Matthews, W. J. (2017). The interrelations between social class, personal relative deprivation, and prosociality. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(6), 660-669. [CrossRef]

- Callan, M. J., Kim, H., & Matthews, W. J. (2015). Age differences in social comparison tendency and personal relative deprivation. Personality and individual differences, 87, 196-199. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Yu, X., Ma’rof, A. A., Zaremohzzabieh, Z., Abdullah, H., Halimatusaadiah Hamsan, H., & Zhang, L. (2022). Social identity, core self-evaluation, school adaptation, and mental health problems in migrant children in China: a chain mediation model. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(24), 16645. [CrossRef]

- CUI N. A study on the relationship of school adjustment and self-conception amongjunior school students.Chongqing:Southwest University. 2008. (in Chinese).

- Evans, G. W., Li, D., & Whipple, S. S. (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological bulletin, 139(6), 1342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannon, J., Budgeon, C. A., & Li, I. W. (2023). Relationships between student mobility and academic and behavioural outcomes in Western Australian public primary schools. Australian Journal of Education, 67(3), 270-289. [CrossRef]

- Gatt, J. M., Alexander, R., Emond, A., Foster, K., Hadfield, K., Mason-Jones, A., Reid, S., Theron, L., Ungar, M., & Wouldes, T. A. (2020). Trauma, resilience, and mental health in migrant and non-migrant youth: an international cross-sectional study across six countries. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, 344024. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-l., Zhang, Y.-n., & Liu, Y. (2020). Changes and new characteristics of the definition of migrant children and left-behind children. Journal of Research on Education for Ethnic Minorities, 31(6), 81-88.

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. In: University of Kansas, KS.

- He, H., & Xiao-Yang, Y. (2022). The Effect of Family Socioeconomic Status on Preschool Migrant Children’s Problem Behaviors: The Chain Mediating Role of Family Resilience and Child-Parent Relationship. Journal of Psychological Science, 45(2), 315.

- Jiang, Y., Granja, M. R., & Koball, H. (2017). Basic facts about low-income children: children 6 through 11 years, 2015.

- Keshavarz, S., Coventry, K. R., & Fleming, P. (2021). Relative deprivation and hope: Predictors of risk behavior. Journal of gambling studies, 37(3), 817-835. [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, W., Pillay, B. J., Swain, K., Rawatlal, N., Borre, A., Naidu, T., Pillay, L., Govender, T., Geils, C., & Jäggi, L. (2017). Cumulative risk, emotion dysregulation, and adjustment in South African youth. Journal of child and family studies, 26(7), 1768-1779. [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G. W., Kochenderfer, B. J., & Coleman, C. C. (1997). Classroom Peer Acceptance, Friendship, and Victimization: Distinct Relational Systems that Contribute Uniquely to Children's School Adjustment? Child Development, 68. [CrossRef]

- Li, D., Zhang, W., Li, X., Li, N., & Ye, B. (2012). Gratitude and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: Direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of adolescence, 35(1), 55-66. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Zhang, X., & Lyu, H. (2024). Low socioeconomic status and academic achievement: a moderated mediation model of future time perspective and Chinese cultural beliefs about adversity. Current Psychology, 43(4), 3669-3681. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., & Wang, Q. (2018). Stressful life events and the development of integrity of rural-to-urban migrant children: the moderating role of social support and beliefs about adversity. Psychological Development and Education, 34(5), 548-557.

- Luo, R., Chen, F., Ke, L., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., & Luo, Y. (2023). Interparental conflict and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal moderated mediation model. Development and psychopathology, 35(2), 972-981. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, B. A. (2022). A Nationally Representative Study of Family Resilience Factors and Socioemotional Functioning in Children of Migrant Farmworkers. The Catholic University of America.

- Ma, A. (2012). Relative deprivation and social adaption: the role of mediator and moderator. Acta Psychologica Sinica. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Escudero, J. A., Garcia, O. F., Alcaide, M., Bochons, I., & Garcia, F. (2023). Parental socialization and adjustment components in adolescents and middle-aged adults: How are they related? Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 1127-1139. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S., & Carleton, R. N. (2015). Subjective relative deprivation is associated with poorer physical and mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 144-149. [CrossRef]

- Mou, J., Griffiths, S. M., Fong, H., & Dawes, M. G. (2013). Health of China's rural–urban migrants and their families: a review of literature from 2000 to 2012. British medical bulletin, 106(1), 19-43. [CrossRef]

- Ohno, H., Lee, K.-T., & Maeno, T. (2023). Feelings of personal relative deprivation and subjective well-being in Japan. Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 158. [CrossRef]

- Olson, D. H., Russell, C. S., & Sprenkle, D. H. (1983). Circumplex model of marital and family systems: Vl. Theoretical update. Family process, 22(1), 69-83. [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F. (2016). In pursuit of three theories: Authoritarianism, relative deprivation, and intergroup contact. Annual review of psychology, 67(1), 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Pinchak, N. P., & Swisher, R. R. (2022). Neighborhoods, schools, and adolescent violence: Ecological relative deprivation, disadvantage saturation, or cumulative disadvantage? Journal of youth and adolescence, 51(2), 261-277. [CrossRef]

- Pu, J., Gan, X., Pu, Z., Jin, X., Zhu, X., & Wei, C. (2024). The healthy context paradox between bullying and emotional adaptation: a moderated mediating effect. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 1661-1675.

- Shek, D. T. (2004). Chinese cultural beliefs about adversity: Its relationship to psychological well-being, school adjustment and problem behaviour in Hong Kong adolescents with and without economic disadvantage. Childhood, 11(1), 63-80. [CrossRef]

- Shek, D. T. (2005). A longitudinal study of Chinese cultural beliefs about adversity, psychological well-being, delinquency and substance abuse in Chinese adolescents with economic disadvantage. Social Indicators Research, 71(1), 385-409. [CrossRef]

- Shek, D. T., Tang, V., Lam, C., Lam, M., Tsoi, K., & Tsang, K. (2003). The relationship between Chinese cultural beliefs about adversity and psychological adjustment in Chinese families with economic disadvantage. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 31(5), 427-443. [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M., & Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality and social psychology review, 16(3), 203-232. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Chui, E. W., Chen, J., & Fu, Y. (2020). School adaptation of migrant children in Shanghai: Accessing educational resources and developing relations. Journal of child and family studies, 29(6), 1745-1756. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. E. (1983). Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. American psychologist, 38(11), 1161. [CrossRef]

- Tetzner, J., & Becker, M. (2015). How being an optimist makes a difference: The protective role of optimism in adolescents’ adjustment to parental separation. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(3), 325-333. [CrossRef]

- Tiangui, T., Hao, L., Zeliang, Y., Xiaofan, P., & Yangu, P. (2024). Longitudinal relationship between social avoidance and distress, learning burnout, school adaptation and depression among high school students. 中国学校卫生, 45(4), 544-548.

- Wadsworth, M. E., & Compas, B. E. (2002). Coping with family conflict and economic strain: The adolescent perspective. Journal of research on adolescence, 12(2), 243-274. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., & Liu, X. (2023). Child abuse and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese migrant adolescents: the moderating roles of beliefs about adversity and family socioeconomic status. Journal of interpersonal violence, 38(3-4), 3165-3190. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Meng, W. (2024). Adverse childhood experiences and deviant peer affiliation among Chinese delinquent adolescents: the role of relative deprivation and age. Frontiers in psychology, 15, 1374932. [CrossRef]

- Wenxin, Z., Meiping, W., & Fuligni, A. (2006). Expectations for autonomy, beliefs about parental authority, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion. Acta Psychologica Sinica.

- Wertsch, J. V. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 23, 143. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, S., Shevlin, M., & Bentall, R. P. (2013). Development and validation of a measure of perceived relative deprivation in childhood. Personality and individual differences, 55(4), 399-405. [CrossRef]

- Winsper, C., Wolke, D., Bryson, A., Thompson, A., & Singh, S. P. (2016). School mobility during childhood predicts psychotic symptoms in late adolescence. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 57(8), 957-966. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Gao, B., Hu, T., & He, W. (2025). The Vicious Cycle of Peer Stress and Self-Directed Violence Among Chinese Left-Behind Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Relative Deprivation. Aggressive Behavior, 51(3), e70035. [CrossRef]

- XIONG, M., & YE, Y. (2016). The concept, measurement, influencing factors and effects of relative deprivation. Advances in Psychological Science, 24(3), 438. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., & Huang, J. (2020). Emotional neglect and gaming addiction of rural left-behind children: the moderating roles of beliefs about adversity. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 9, 86-93.

- Yang, B., Xiong, C., & Huang, J. (2021). Parental emotional neglect and left-behind children’s externalizing problem behaviors: The mediating role of deviant peer affiliation and the moderating role of beliefs about adversity. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105710.

- Yang, G., Chen, Y., Ye, M., Cheng, J., & Liu, B. (2023). Relationship between family risk factors and adolescent mental health. Zhong nan da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban= Journal of Central South University. Medical Sciences, 48(7), 1076-1085. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Y., & Maguire-Jack, K. (2018). Individual and cumulative risks for child abuse and neglect. Family relations, 67(2), 287-301. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y., & Xiong, M. (2017). The effect of environmental factors on migrant children’s relative deprivation: the moderating effect of migrant duration. Chin J Spec Educ, 7, 41-46.

- Yu, L., Wu, X., Zhang, Q., & Sun, B. (2024). Social Support and Social Adjustment Among Chinese Secondary School Students: The Mediating Roles of Subjective Well-Being and Psychological Resilience. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 3455-3471. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Dong, C., Jiang, Y., Zhang, Q., Li, H., & Li, Y. (2023). Parental phubbing and child social-emotional adjustment: A meta-analysis of studies conducted in China. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 4267-4285. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J., Gu, J., & Wang, W. (2022). The relationship between bullying victimization and cyber aggression among college students: The mediating effects of relative deprivation and depression. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 3003-3012.

- Zhang, J., & Tao, M. (2013). Relative deprivation and psychopathology of Chinese college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 903-907. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L., Zhang, Y., Zhou, J., Zhang, X., & Gao, L. (2024). The Mediating Role of School Adaptation in the Impact of Adolescent Victimization from Bullying on Mental Health: A Gender Differences Perspective. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 3515-3531. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J., Liu, X., & Zhang, W. (2013). Peer rejection, peer acceptance and psychological adjustment of left-behind children: The roles of parental cohesion and children's cultural beliefs about adversity. Acta Psychologica Sinica. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Luan, F., Sun, P., Xu, T., & Liu, X. (2017). Parental cohesion, beliefs about adversity and left-behind children’s positive/negative emotion in rural China. Psychological Development and Education, 33(4), 441-448.

- Zhenwu, Z., & Wenli, L. (2021). Data quality of the 7th population census and new developments of China's population. Population Research, 45(3), 46.

- Zhou, M., Fan, L., Tian, Y., Wu, D., Zhang, F., & Du, W. (2022). Does mental health mediate the effect of deviant peer affiliation on school adaptation in migrant children: evidence from a nationally representative survey in China. Public Health, 213, 78-84. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).