1. Introduction

The Internet has become an essential part of people’s lives, helping them to carry out various academic, free-time, or social activities via social media, becoming an almost indispensable part of everyday life. Due to its ease of access, Internet usage has increased across all age groups worldwide. The Internet World Stats estimated that in 2022, the percentage of Internet users reached 67,9% of the world population (growing exponentially in recent years). Despite the benefits that the Internet provides, it is not exempt from problems, the greatest of which is the addiction that it generates. Internet addiction is defined as the excessive use of the Internet, which produces cognitive, psychological, or physical harm; experiencing withdrawal symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and nervousness upon losing access, producing a decline in areas of functioning such as school, family, and social life (Young, 2004). Although, unlike other addictions (Galdós & Sánchez, 2010), Internet addiction has not been adopted in the diagnostic section of the 5th Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013) nor the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11, World Health Organization, 2019), considerable proof exists regarding the negative effects on physical and mental health, as well as on social development (Serna & Martínez, 2023).

Gender differences have been frequently reported in patterns of Internet addiction (Liang et al., 2016). Studies indicate that differences in motivation exist by gender, whereby boys tend to experience more addictive behavior when they play games related to power and controlling or exploring sexual fantasies online. In contrast, girls are more likely to communicate with both close and anonymous friends online to share their feelings and emotions (Young, 1998). Additionally, studies reveal that the association between Internet addiction and related factors (e.g., low self-esteem, attention deficit) is higher in boys, with gender being a risk factor in Internet addiction (Liang et al., 2016).

Technological advances and massive Internet usage have also made access to online gambling easier, offering a wide variety of gambling activities that can be carried out via Internet-enabled devices (mobile phones, computers, etc.). These, in turn, can be carried out anytime and anywhere. The possibility to place large bets continuously, easily, and instantaneously is cause for concern as it encourages online gambling addiction. Furthermore, one advantage for the player is that one can remain anonymous while gambling, which is a benefit for the gambler given that they can avoid the negative judgments associated with gambling behavior (Frisone et al., 2020). As a result of parallels between gambling problems and substance use, the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) includes a new category of Non-Substance Behavioural Addiction within the substance addictions category.

In summary, given the pathological similarities of the gambling experience and Internet gambling, and the added harm of Internet addiction, the use of Internet gambling warrants specific consideration. Although a large body of empirical research has been conducted on identifying risk and resiliency factors that influence gambling behavior (demographic, environmental, personality, or biological factors), only a handful of studies have examined other variables that may be associated with online gambling (e.g., Philander & MacKay, 2014). In this sense, it is important to keep the role of craving in mind, that is, the urge to gamble, which functions as excitement as well as alleviates negative emotions (Young & Wohl, 2009).

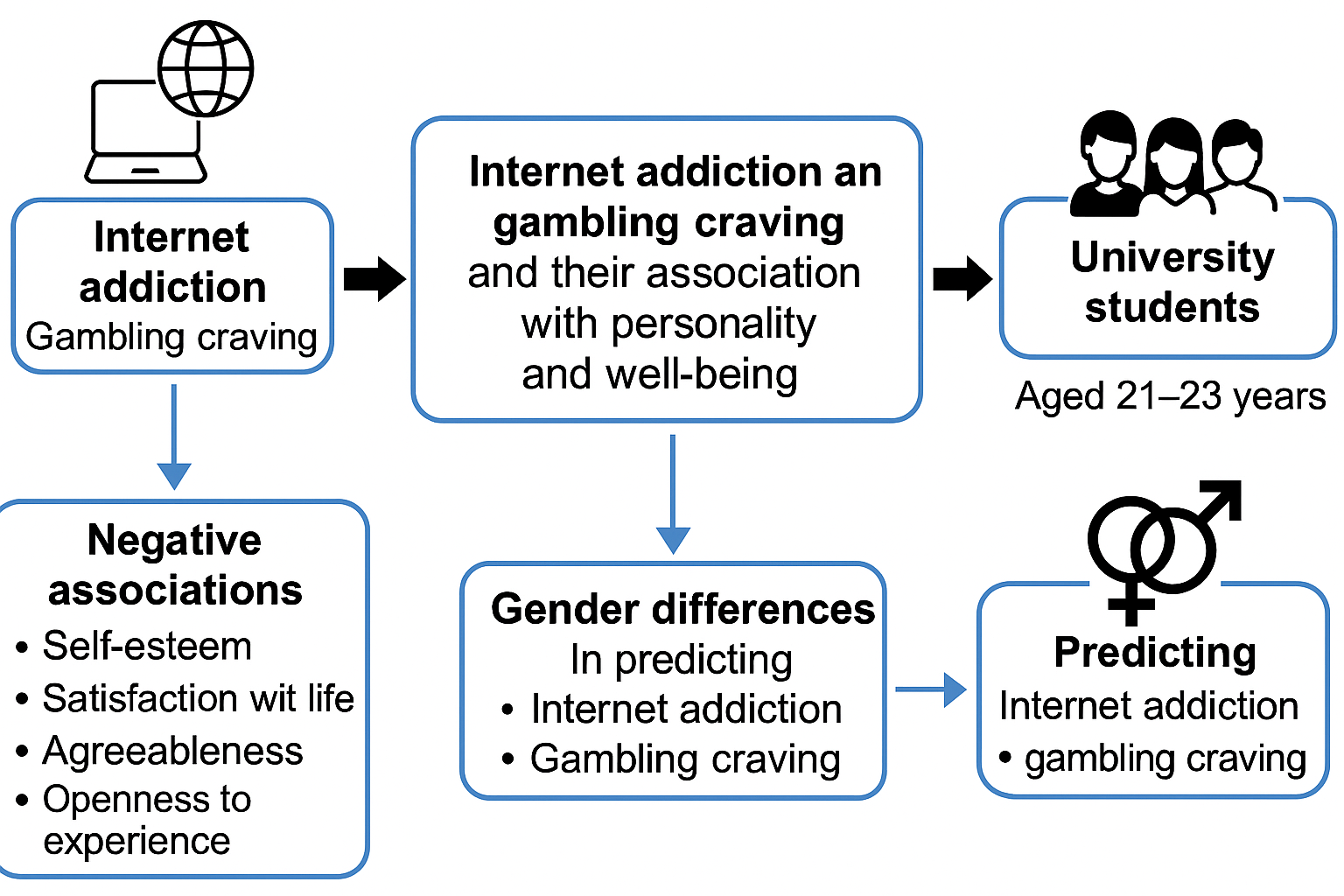

Moreover, excessive Internet usage has prompted research to analyze the influence of different factors on Internet addiction. In this way, Internet addiction has been related to different variables, such as personality, academic performance, depression, the consumption of drugs, alcohol, and tobacco, along with other factors of psychological well-being, such as self-esteem (Dong et al., 2013; Fioravanti et al., 2012). In this study, Internet addiction and gambling craving are related to personality and psychological well-being, measured through self-esteem and satisfaction with life, taking into account possible gender differences.

Personality has been defined as psychological traits that contribute to an individual’s enduring and distinctive patterns of feeling, thinking, and behaving (Cervone, & Pervin, 2010). One of the models most used to describe personality is “The Big Five Model” (Goldberg, 1993). Through this model, personality is explained with five big dimensions: (1) Extraversion, which includes the ability to assert oneself, stand out and influence others, energy and enthusiasm; (2) Agreeableness, which includes the ability to cooperate and listen to others and politeness, i.e., affability or trustworthiness; (3) Conscientiousness, which includes perseverance, persistence and conscientiousness (meticulousness and orderliness); (4) Emotional stability (or the inverse trait, neuroticism), which includes control of one's behavior and control of emotions; and (5) Openness, which includes openness to experience (different values or ways of life) and openness to culture (interest in staying informed and acquiring new knowledge) (McCrae & Costa, 1997; Saiz et al., 2011). Some differences in personality traits by gender have been detected. Women tend to score higher in agreeableness, extraversion, and neuroticism. In the case of openness and conscientiousness, gender differences were small or undetectable (Weisberg, 2011).

The relationship between the big five personality factors and Internet addiction has been analyzed in some recent studies (e.g., Kayiş et al., 2016). Most studies agree that emotional stability (or neuroticism) is one of the personality traits that most predict Internet addiction. In general, the greater the emotional stability, the lower the Internet addiction (Kayiş et al., 2016). Similarly, the traits of extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness tend to relate negatively to Internet addiction in most studies (e.g., Sevidio, 2014; Kayiş et al., 2016).

Moreover, self-esteem is an individual’s set of thoughts and feelings about him/herself and the degree of self-approval or refusal (Rosenberg, 1965). Self-esteem, as the person's perception of him/herself, is formed through experiences with the environment and is influenced especially by environmental reinforcements and significant others (Shavelson et al., 1976). As the core of the individual, self-esteem has been considered key in understanding behavioral, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning (Shavelson et al., 1976). Evidence has shown that males score higher on standard measures of global self-esteem than females as a consequence of learned gender roles and stereotypes (Bleidorn et al., 2016). Self-esteem has been related to a large variety of positive psychological and behavioral outcomes, such as psychological adjustment, positive emotion, or Internet addiction, with a negative relationship between Internet addiction and self-esteem tending to appear (Bahrainian et al., 2014; Greenberg et al., 1999).

Finally, an area of increasing interest among researchers is concerned with how and why people experience their lives in positive ways (i.e., life satisfaction). Life satisfaction is defined as an individual’s overall appraisal of the quality of her or his life, including the immediate effects of life events and mood states (Diener et al.,1999). Life satisfaction has been related to health status, occupation, effective interpersonal relationships, and school dropout (Gómez-Escalonilla et al., 2023; Veenhoven,1988). Research has also shown that global life satisfaction remains invariant across genders (Gilman & Huebner 2003).

The objective of this study was to relate Internet addiction and gambling craving with personality and psychological well-being, measured through self-esteem and satisfaction with life, in a sample of Spanish university students, taking into account possible gender differences. Although studies analyzing online gambling are limited in comparison to those that analyze Internet addiction, given previous research, we expect that Internet addiction and online gambling relate negatively to self-esteem, life satisfaction, and the big five personality factors (agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, extraversion, and emotional stability), in both, boys and girls.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

To ensure a statistical power of 95% (1 − β = 0.95), an a priori calculation was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al., 2009) to determine the minimum required sample size. The analysis set the Type I error rate at the conventional threshold (α = 0.05) and considered a medium effect size (f = 0.21) (Cohen, 1977) in the F-test between Internet addiction and personality factors. The findings indicated that at least 510 participants would be needed for the study. The sample consisted of 517 university students from a large metropolitan area in Spain with over one million inhabitants, 148 males (28.6%) and 369 females (71.4%) from 21 to 23 years old (M= 21.53 years, SD = 3.76.

From a comprehensive list of the university courses in the region, 12 classes were randomly selected through simple random sampling. A professor from each selected class was then contacted to facilitate the online administration of the survey. Student participation was entirely voluntary, with no compensation provided. Considering the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of 1004SEU on 21/03/2025, participants were informed about the procedure for completing the instruments, as well as the conditions regarding the anonymity and confidentiality of the survey, ensuring that they could provide honest and sincere responses following Institutional Review Board approval.

2.2. Instruments

Internet addiction was captured with the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) developed by Young (1998), who likened excessive Internet use most closely to pathological gambling, a disorder of impulse control in DSM-4, and adapted the DSM-4 criteria. Respondents answered the 20-item questionnaire on which are asked to rate items on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“always”), covering the degree to which their Internet use affects their daily routine, social life, productivity, sleeping pattern, and feelings, (e.g., "How often do you neglect the things you need to do around the house to spend more time online?" This scale has high face validity, and it has been subjected to systematic psychometric testing in several countries, such as Spain, the USA, and Colombia (Panova et al., 2021). In this study, the reliability of the Internet Additions Test showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.91.

Online gambling was captured with the Gambling Craving Scale (GC) developed by Young & Wohl (2009). This scale is a short version of a longer scale based on literacy and on criteria to diagnose pathological gambling according to the APA in the Fourth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-4, APA, 1994). Respondents answered the 9 questions on a 7-point scale anchored at 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), measuring the intention to gamble that was anticipated to be fun and enjoyable, the strong and urgent desire to gamble, or the relief from expected negative gambling experiences (e.g., “If I were gambling now, I would be able to think more clearly”). In this study, the reliability of the Gambling Craving Scale showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.74.

Self-esteem was captured with the Self-Esteem Scale developed by Rosenberg (1965) that was adapted to Spanish by Atienza, Moreno, and Balaguer (2000). Respondents answered the 10-item questionnaire on which they are asked to rate items on a five-point Likert scale from 1 to 4 (Strongly disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly agree) (e.g., “I feel that I'm a person of worth”). This scale has been validated in numerous countries (Schmitt & Allik, 2005), and its original reliability was 0.77. For this study, the reliability of the Self-Esteem Scale showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.86.

Personality traits were captured with Mini-IPIP Scale (Donnellan et al., 2006), which is the abbreviated version of the IPIP (International Personality Item Pool) Big Five factorial markers (Goldberg, 1992). Respondents answered the 20 items (four per dimension): Extraversion (E) (e.g., “Talk to a lot of different people at parties”), agreeableness (A) (e.g., “Feel others' emotions”), conscientiousness (C) (e.g., “Talk to a lot of different people at parties”), emotional stability (S) (originally formulated in the inverse sense as neuroticism) (e.g. “ Get upset easily”), and openness (O) (In some research this dimension is also called Intellect or Imagination) (e.g. “Am interested in abstract ideas”). We apply the Spanish version of the Mini-IPIP Scales used by Martínez-Molina and Arias (2018). In this study, the reliability of the Mini-IPIP showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91, and for every factor, the reliability was 0.72 (E), 0.78 (A), (0.75) C, (0.79) S and O (0.81).

Satisfaction with Life Scale was captured with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) developed by Diener et al. (1985), which was adapted to Spanish by Vázquez, Duque, and Hervás (2013). It is a one-dimensional instrument consisting of five items that evaluate the general satisfaction that the individual has with his life. The Likert-type scale of five points rated 1 (very disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); higher scores reflect greater satisfaction (e.g., “ I am satisfied with my life”). In this study, the reliability of the Satisfaction with Life Scale showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.86.

2.3. Plan of Analysis

Firstly, a descriptive and correlational analysis of the study variables was performed. The correlations between the study variables were calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and the difference by gender for each variable was calculated using Student’s t-test. Subsequently, we performed multiple regression analyses to predict the factors of Internet addiction and gambling craving for girls and boys. Statistical analyses were performed using the software package SPSS 28.0.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Analysis of Differences

Internet Addiction presents a positive and significant correlation with GC (r = 0.197, p <.001), however, it shows a significant and inverse relationship with SE (r = -0.258, p <.001), SWL (r = -0.172, p <.001), BFA (r = -0.268, p <.001), BFC (r = -0.224, p <.001), BFS (r = -0.130, p <.01) and BFO (r = -0.223, p <.001). On the other hand, gambling craving presents inverse and significant correlations with SE (r = -0.129, p <.01), SWL (r = -0.119, p <.01), BFA (r = -0.235, p <.001), and BFO (r = -0.099, p <.05).

The results (

Table 1) showed that IA (Internet Addition) was higher in men (M = 2.12, SD = 0.68) than in women (M = 1.93, SD = 0.64), (t(515) = 3.03, p <.01), and GC (Gambling Craving) was also higher in men (M = 1.44, SD = 0.82) than in women (M = 1.30, SD = 0.46) (t(515) = 2.41, p <.01). Satisfaction with life presents statistically significant differences (t(515) = -2.41, p <.01), showing that men (M = 2.76, SD = 0.63) present lower scores than women (M = 2.90, SD = 0.57). Self-esteem did not present statistically significant differences between men and women. On the other hand, the personality factors of the Mini-IPIP showed statistically significant differences by gender in BFE (Extraversion), women (M = 3.11, SD = 0.82) scored higher than men (M = 2.94, SD = 0.88) (t(515) = -2.09, p <.05), in BFA (Agreeableness) women obtained higher scores (M = 4.15, SD = 0.64) than men (M = 3.74, SD = 0.68) (t(515) = -6.49, p <.001), in BFC (Conscientiousness) the scores of women (M = 3.24, SD = 0.82) were statistically higher than those of men (M = 3.07, SD = 0.84) (t(515) = 2.19, p <.05), however in BFS (Emotional Stability) men (M = 3.05, SD = 0.82) scored higher than women (M = 2.71, SD = 0.72) (t(515) = 4.66, p <.001), and, finally, the results did not show statistically significant differences in BFO (openness to experience) between genders.

3.2. Predictive Factors of Internet Addiction

To estimate the association between the personal variables of young people with Internet addiction, a multiple linear regression was performed separately for men (

Table 2) and women (

Table 3). Before multiple regression analysis, multicollinearity should be assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance. Tolerance measures how much beta coefficients are affected by the presence of other predictor variables in a model. The cut-off for tolerance that is generally accepted falls at 0.25; smaller values of tolerance denote higher levels of multicollinearity (Shrestha, 2020). VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) measures the extent to which the regression coefficients are affected by other independent variables in the model. Higher values of VIF are associated with multicollinearity. The generally accepted cutoff for VIF is 2.5, with higher values indicating levels of multicollinearity that could negatively affect the regression model.

The explanatory model of Internet addiction based on personal factors does not show multicollinearity between the variables (Tolerance > 0.25, VIF < 2.5). The predictive model for men was statistically significant (F (7,140) = 6.113, p <.001, R2adjust = 0.196), explaining 19.6% of the variance. The significant factors of the predictive model in men were extraversion (BFE) (Beta = -0.243, (t(140) = -3.08, p = 0.003), conscientiousness (BFC) (Beta = -0.14, (t(140) = -2.31, p = 0.022), and openness to experience (BFO) (Beta = -0.159, (t(140) = -2.14, p = 0.034). See

Table 2. The predictive model for women was also statistically significant (F (7,361) = 9.693, p <.001, R2adjust = 0.153), explaining 15.3% of the variance. The significant factors of the predictive model in women were self-esteem (SE) (Beta = -0.221, (t(361) = -2.947, p = 0.003), agreeableness (BFA) (Beta = -0.131, (t(361) = -2.570, p = 0.011), conscientiousness (BFC) (Beta = -0.133, (t(364) = -3.422, p = 0.001), and openness to experience (BFO) (Beta = -0.148, (t(361) = -2.14, p <.001). See

Table 3.

3.3. Predictive factors of Gambling Craving

The predictive model for gambling craving in men was not statistically significant (F (7,140) = 1.467, p > 0.05). However, the predictive model for women was statistically significant (F (7,361) = 5,384, p <.001, R2adjust = 0.077), explaining 7.76% of the variance. The explanatory model of gambling craving in women based on personal factors did not show multicollinearity between the variables (Tolerance > 0.25, VIF < 2.5). The significant factor of the predictive model in women was agreeableness (BFA) (Beta = -0.175, (t(361) = -4.595, p <.001). None of the other variables of the model were not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression to identify predictor of gambling craving for women.

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression to identify predictor of gambling craving for women.

| R |

R Square |

Adjust R square |

SEE |

F |

p |

| ,307 |

,095 |

,077 |

,44018 |

F(7,361)=5.384 |

<.001 |

| |

B |

Stand Coef |

t |

Sig |

CI 95% |

Tolerance |

VIF |

| Constant |

2.310 |

|

10.461 |

<.001 |

1.87 |

2.74 |

|

|

| SE |

-0.099 |

-0.119 |

-1.759 |

0.079 |

-0.20 |

0.01 |

0.548 |

1.823 |

| SWL |

-0.055 |

-0.069 |

-1.054 |

0.293 |

-0.15 |

0.04 |

0.585 |

1.710 |

| BFE |

0.035 |

0.062 |

1.160 |

0.247 |

-0.02 |

0.09 |

0.867 |

1.153 |

| BFA |

-0.175 |

-0.244 |

-4.595 |

<0.001 |

-0.25 |

-0.10 |

0.890 |

1.124 |

| BFC |

0.024 |

0.042 |

0.814 |

0.416 |

-0.03 |

0.08 |

0.934 |

1.071 |

| BFS |

-0.002 |

-0.003 |

-0.051 |

0.959 |

-0.07 |

0.07 |

0.726 |

1.377 |

| BFO |

-0.001 |

-0.002 |

-0.038 |

0.969 |

-0.06 |

0.06 |

0.937 |

1.067 |

4. Discussion

The relationship between Internet addiction and gambling craving with personality and psychological well-being, measured through self-esteem and satisfaction with life, is confirmed in Spanish university students. Additionally, the results show that Internet addiction relates positively with online gambling, in line with previous studies that indicate that Internet addiction is closely linked to pathological online gambling, given that the availability of the Internet today provides novel and ample opportunities to gamble online (Comparcini et al., 2018).

Furthermore, the results of the study show that Internet addiction relates negatively to self-esteem and satisfaction with life. These results are consistent with previous studies, which have shown that self-esteem and satisfaction with life relate negatively to Internet addiction (Bahrainian et al., 2014; Greenberg et al., 1999). Regarding the relationship of personality traits of agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience with Internet addiction, the results also confirm previous research (Sevidio, 2014; Kayiş et al., 2016). This reinforces the idea that youth who have difficulty relating with peers in a real, face-to-face environment are at greater risk for addiction to the Internet (Landers, & Lounsbury, 2006). It has also been argued that individuals with low levels of agreeableness are likely to demonstrate aggressive and hostile behaviors, preferring the Internet to establish new, interpersonal relationships to satisfy the need for relationships and to display these behaviors (Landers & Lounsbury, 2006). Likewise, youth who score low on conscientiousness have been described as low self-disciplined individuals who cannot control their Internet usage (Costa & McCrae, 1992). In the same way, youth with low emotional stability would also not possess regulation strategies that allow them to control Internet addiction (Sevidio, 2014). Lastly, youth who score high on openness have a lower tendency to develop an addiction to the Internet, which could have to do with real-world experiences being more vivid and realistic than virtual ones (Kayiş et al., 2016).

Moreover, gambling craving is negatively related to self-esteem, satisfaction with life, agreeableness, and openness to experience. Although this relationship has not been extensively researched in the literature, the results are consistent with previous studies that identified a relationship between personal vulnerability (e.g., inferiority in peer groups, self-esteem) and gambling craving, such that gambling acts would represent a form of emotional evasion while substituting other deficiencies (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002). As Craig (1995) argues, an individual's negative self-worth in relationships with peers can lead to dependent behaviors to avoid such relationships.

Additionally, the differences between boys and girls were considered in predicting Internet addiction and gambling craving through personality and psychological well-being. The results indicate that in boys, the traits of personality, extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience predict Internet addiction. However, self-esteem and the personality traits of agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness better predict Internet addiction in girls. Regarding gambling craving, none of the variables analyzed predicted its presence in boys, while in girls, agreeableness was the predictive variable.

Finally, although not central to this research, the study shows some gender differences in personality and psychological well-being variables consistent with previous research (Weisberg, 2011). Girls scored higher than boys in the personality traits of extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness; however, boys scored higher than girls in emotional stability. Furthermore, although no differences were found in self-esteem between girls and boys, girls scored higher than boys in satisfaction with life.

Several limitations of the study should be noted to provide direction for future research. First, the study was conducted with university students, so the participants may not be representative. Second, the study was cross-sectional and used self-reporting measures, so future research might be carried out with other populations and use longitudinal data to generate a more solid relationship among the constructs examined. In any case, the results show the importance of considering Internet addiction and gambling craving as two separate behaviors and the differences in the variables that predict Internet addiction and gambling craving in boys and girls.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org.

Authors’ contributor roles

Joan García-Perales: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing. Isabel Martínez: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing. Elena Delgado: Investigation, Visualization, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing–review & editing

Funding

This work was realized in the framework of the project 2022-GRIN-34452, 85% co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, within the framework of the FEDER Program of Castilla-La Mancha for the period 2021–2027, action 01A/008.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Selart European University in Spain (protocol code 7/2024 and 15 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest .

References

- American Psychiatric Association, D. S. M. T. F., & American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Vol. 5, No. 5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Atienza, F., Moreno, Y., & Balaguer, I. (2000). Escala de autoestima de Rosenberg. Apunt Psicol, 22(2), 247-55.

- Bahrainian, S. A., Alizadeh, K. H., Raeisoon, M. R., Gorji, O. H., & Khazaee, A. (2014). Relationship of Internet addiction with self-esteem and depression in university students. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene, 55(3), 86.

- Bearsley, C., & Cummins, R. A. (1999). No place called home: Life quality and purpose of homeless youths. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 8, 207-226. [CrossRef]

- Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97(5), 487–499. [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn, W., Arslan, R. C., Denissen, J. J., Rentfrow, P. J., Gebauer, J. E., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. Journal of personality and social psychology, 111(3), 396–410. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/pspp0000078.

- Cervone, D., & Pervin, L. A. (2022). Personality: Theory and research. John Wiley & Sons.

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Comparcini, D., Simonetti, V., Galli, F., Buccoliero, D., Palombelli, E., Sepede, G. y Cicolini, G. (2018). Gioco d’azzardo patologico e dipendenza da Internet tra gli studenti infermieri: uno studio pilota. Professioni infermieristiche, 71(1).

- Costa Jr, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and individual differences, 13(6), 653-665. [CrossRef]

- Craig, R. J. (1995). The role of personality in understanding substance abuse. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 13(1), 17-27. [CrossRef]

- Cuadri, C., Garcia-Perales, J., Martínez, I. & Veiga, F. (2025). Relationship Between Parenting Styles and Personality in Older Spanish Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):339. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40150234/. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of personality assessment, 49(1), 71-75. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological bulletin, 125(2), 276. [CrossRef]

- Dong, G., Wang, J., Yang, X., & Zhou, H. (2013). Risk personality traits of Internet addiction: A longitudinal study of Internet-addicted Chinese university students. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 5(4), 316-321. [CrossRef]

- Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological assessment, 18(2), 192. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior research methods, 41(4), 1149-1160. [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, G., Dèttore, D., & Casale, S. (2012). Adolescent Internet addiction: testing the association between self-esteem, the perception of Internet attributes, and preference for online social interactions. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(6), 318-323. [CrossRef]

- Frisone, F., Settineri, S., Sicari, P. F., & Merlo, E. M. (2020). Gambling in adolescence: a narrative review of the last 20 years. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(4), 438-457. [CrossRef]

- Galdós, J. S., & Sánchez, I. M. (2010). Relación del tratamiento por dependencia de la cocaína con los valores personales de apertura al cambio y conservación. Adicciones, 22(1), 51-58. [CrossRef]

- Gilman, R., & Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 192-205. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological assessment, 4(1), 26. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American psychologist, 48(1), 26-34. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. L., Lewis, S. E., & Dodd, D. K. (1999). Overlapping addictions and self-esteem among college men and women. Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 565-571. [CrossRef]

- Internet World Stats: Usage and Population Statistics (Nov 15, 2023). Internet Usage Statistics. Available online: https://www.Internetworldstats.com/stats.htm (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Kayiş, A. R., Satici, S. A., Yilmaz, M. F., Şimşek, D., Ceyhan, E., & Bakioğlu, F. (2016). Big five-personality trait and Internet addiction: A meta-analytic review. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Landers, R. N., & Lounsbury, J. W. (2006). An investigation of Big Five and narrow personality traits in relation to Internet usage. Computers in human behavior, 22(2), 283-293. [CrossRef]

- Liang, L., Zhou, D., Yuan, C., Shao, A., & Bian, Y. (2016). Gender differences in the relationship between Internet addiction and depression: A cross-lagged study in Chinese adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 463-470. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Molina, A., & Arias, V. B. (2018). Balanced and positively worded personality short-forms: Mini-IPIP validity and cross-cultural invariance. PeerJ, 6. [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American psychologist, 52(5), 509-516. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & quantity, 41, 673-690. [CrossRef]

- Panova, T., Carbonell, X., Chamarro, A., & Ximena Puerta-Cortes, D. (2021). Internet Addiction Test research through a cross-cultural perspective: Spain, USA and Colombia. Adicciones, 33(4). Available online: https://www.adicciones.es/index.php/adicciones/article/view/1345/1132 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Philander, K. S., & MacKay, T. L. (2014). Online gambling participation and problem gambling severity: Is there a causal relationship?. International Gambling Studies, 14(2), 214-227. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures package, 61(52), 18.

- Saiz, J., Álvaro, J. L., & Martínez, I. (2011). Relación entre rasgos de personalidad y valores personales en pacientes dependientes de la cocaína. Adicciones, 23(2), 125-132. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of personality and social psychology, 89(4), 623-642. [CrossRef]

- Serna, C., García-Perales, J., & Martínez, I. (2023). Protective and risk parenting styles for Internet and online gambling addiction. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R. (2014). Exploring the effects of demographic factors, Internet usage and personality traits on Internet addiction in a sample of Italian university students. Computers in human behavior, 35, 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Review of educational research, 46(3), 407-441. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. (2020). Detecting multicollinearity in regression analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, 8(2), 39-42. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, C., Duque, A., & Hervas, G. (2013). Satisfaction with life scale in a representative sample of Spanish adults: validation and normative data. The Spanish journal of psychology, 16, E82. [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. (1988). The utility of happiness. Social indicators research, 20, 333-354. [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, Y. J., DeYoung, C. G., & Hirsh, J. B. (2011). Gender differences in personality across the ten aspects of the Big Five. Frontiers in psychology, 2, 178. [CrossRef]

- Young, K. S. (1998). Caught in the net: How to recognize the signs of Internet addiction--and a winning strategy for recovery. John Wiley & Sons.

- Young, K. S. (2004). Internet addiction: A new clinical phenomenon and its consequences. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(4), 402-415. [CrossRef]

- Young, M. M., & Wohl, M. J. (2009). The Gambling Craving Scale: Psychometric validation and behavioral outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(3), 512-522. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Correlations and differences in means by gender.

Table 1.

Correlations and differences in means by gender.

| |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| 1. IA |

--- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. GC |

0.197*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3. SE |

-0.258*** |

-0.129** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4. SWL |

-0.172*** |

-0.119** |

0.617*** |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 5. BFE |

-0.058 |

-0.024 |

0.263*** |

0.241*** |

|

|

|

|

|

| 6. BFA |

-0.268*** |

-0.235*** |

0.135*** |

0.181*** |

0.196*** |

|

|

|

|

| 7. BFC |

-0.224*** |

-0.056 |

0.122** |

0.131** |

-0.050 |

0.137** |

|

|

|

| 8. BFS |

-0.130** |

-0.065 |

0.443** |

0.391*** |

0.097* |

-0.058 |

-0.024 |

|

|

| 9. BFO |

-0.223*** |

-0.099* |

0.127*** |

0.067 |

0.103* |

0.202*** |

-0.026 |

0.052 |

|

| Mm |

2.12 |

1.44 |

3.01 |

2.76 |

2.94 |

3.74 |

3.07 |

3.05 |

3.72 |

| SDm |

0.68 |

0.82 |

0.62 |

0.63 |

0.88 |

0.68 |

0.84 |

0.82 |

0.71 |

| Mw |

1.93 |

1.30 |

3.02 |

2.90 |

3.11 |

4.15 |

3.24 |

2.71 |

3.62 |

| SDw |

0.64 |

0.46 |

0.55 |

0.57 |

0.82 |

0.64 |

0.82 |

0.72 |

0.76 |

| t |

3.03** |

2.41** |

-0.19 |

-2.41** |

-2.09* |

-6.49*** |

-2.19* |

4.66*** |

1.32 |

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression to identify predictor of Internet addiction in men.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression to identify predictor of Internet addiction in men.

| R |

R Square |

Adjust R2 |

SEE |

F |

p |

| 0.484 |

0.234 |

0.196 |

0.607 |

F(7,140)=6.113 |

<.001 |

| |

B |

Stand Coef |

t |

sig |

CI 95% |

Tolerance |

VIF |

| Constant |

4,817 |

|

11,12 |

,000 |

|

,548 |

|

|

| SE |

-0.216 |

-0.199 |

-1.95 |

.053 |

3.96 |

.585 |

.527 |

1.899 |

| SWL |

0.086 |

0.079 |

0.78 |

.436 |

-0.44 |

.867 |

.530 |

1.886 |

| BFE |

-0.014 |

-0.019 |

-0.23 |

.815 |

-0.13 |

.890 |

.861 |

1.161 |

| BFA |

-0.243 |

-0.245 |

-3.08 |

.003 |

-0.14 |

.934 |

.867 |

1.154 |

| BFC |

-0.14 |

-0.174 |

-2.31 |

.022 |

-0.40 |

.726 |

.962 |

1.039 |

| BFS |

-0.102 |

-0.122 |

-1.45 |

.148 |

-0.26 |

.937 |

.771 |

1.297 |

| BFO |

-0.159 |

-0.167 |

-2.14 |

.034 |

-0.24 |

.548 |

.891 |

1.123 |

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression to identify predictors of Internet addiction for women.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression to identify predictors of Internet addiction for women.

| R |

R Square |

Adjust R2 |

SEE |

F |

p |

| .398 |

.158 |

.153 |

0.588 |

F(7,361)=9.693 |

<.001 |

| |

B |

Stand Coef |

t |

Sig |

CI 95% |

Tolerance |

VIF |

| Constant |

4,014 |

|

13.599 |

<.001 |

3.43 |

4.59 |

|

|

| SE |

-0.221 |

-0.192 |

-2.947 |

0.003 |

-0.36 |

-0.07 |

0.548 |

1.823 |

| SWL |

0.025 |

0.023 |

0.363 |

0.717 |

-0.11 |

0.16 |

0.585 |

1.710 |

| BFE |

0.063 |

0.081 |

1.553 |

0.121 |

-0.01 |

0.14 |

0.867 |

1.153 |

| BFA |

-0.131 |

-0.132 |

-2.570 |

0.011 |

-0.23 |

-0.03 |

0.890 |

1.124 |

| BFC |

-0.133 |

-0.171 |

-3.422 |

0.001 |

-0.21 |

-0.05 |

0.934 |

1.071 |

| BFS |

-0.065 |

-0.073 |

-1.296 |

0.196 |

-0.16 |

0.03 |

0.726 |

1.377 |

| BFO |

-0.148 |

-0.177 |

-3.557 |

<.001 |

-0.22 |

-0.06 |

0.937 |

1.067 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).