Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

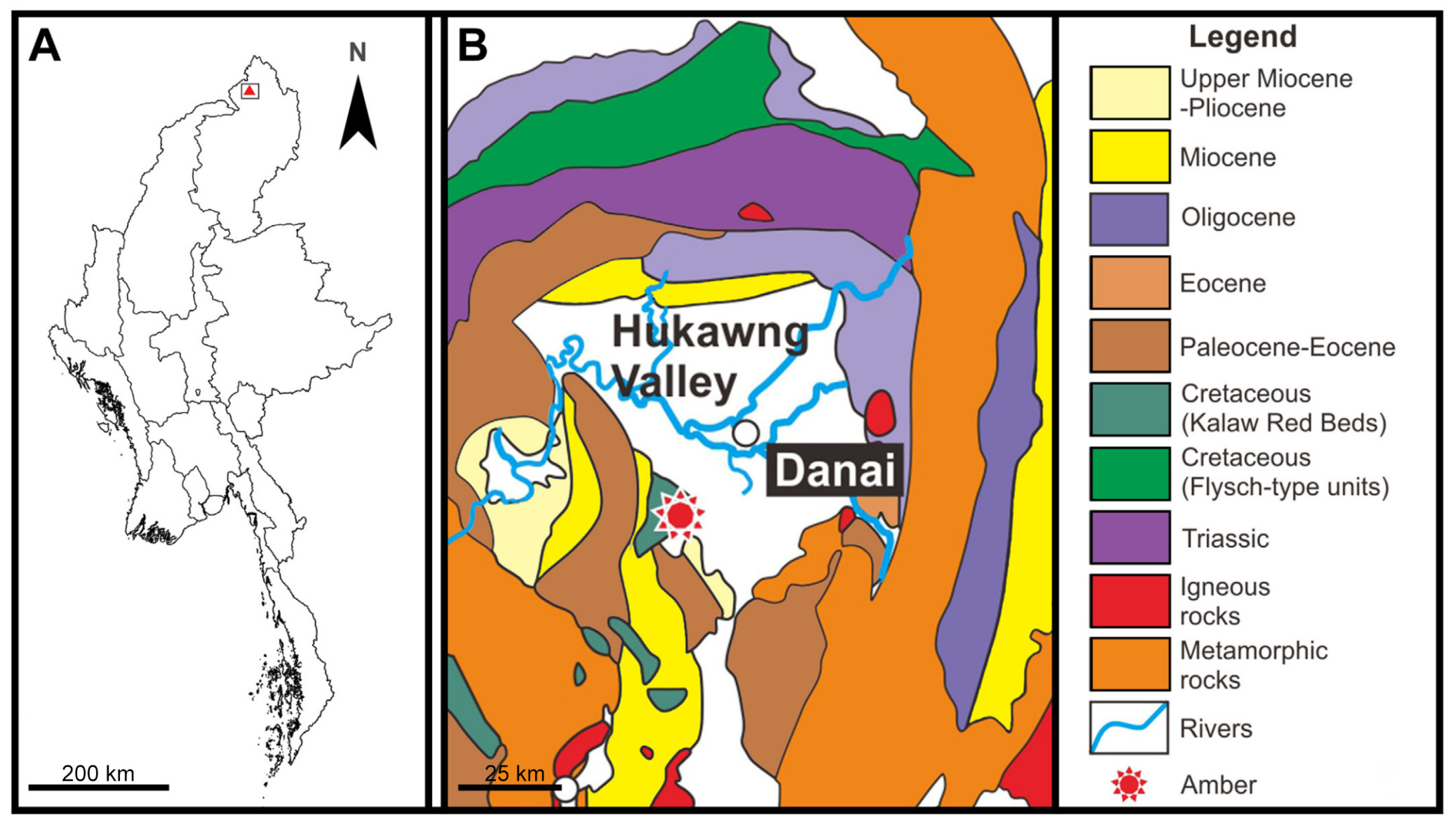

2. Materials and Methods

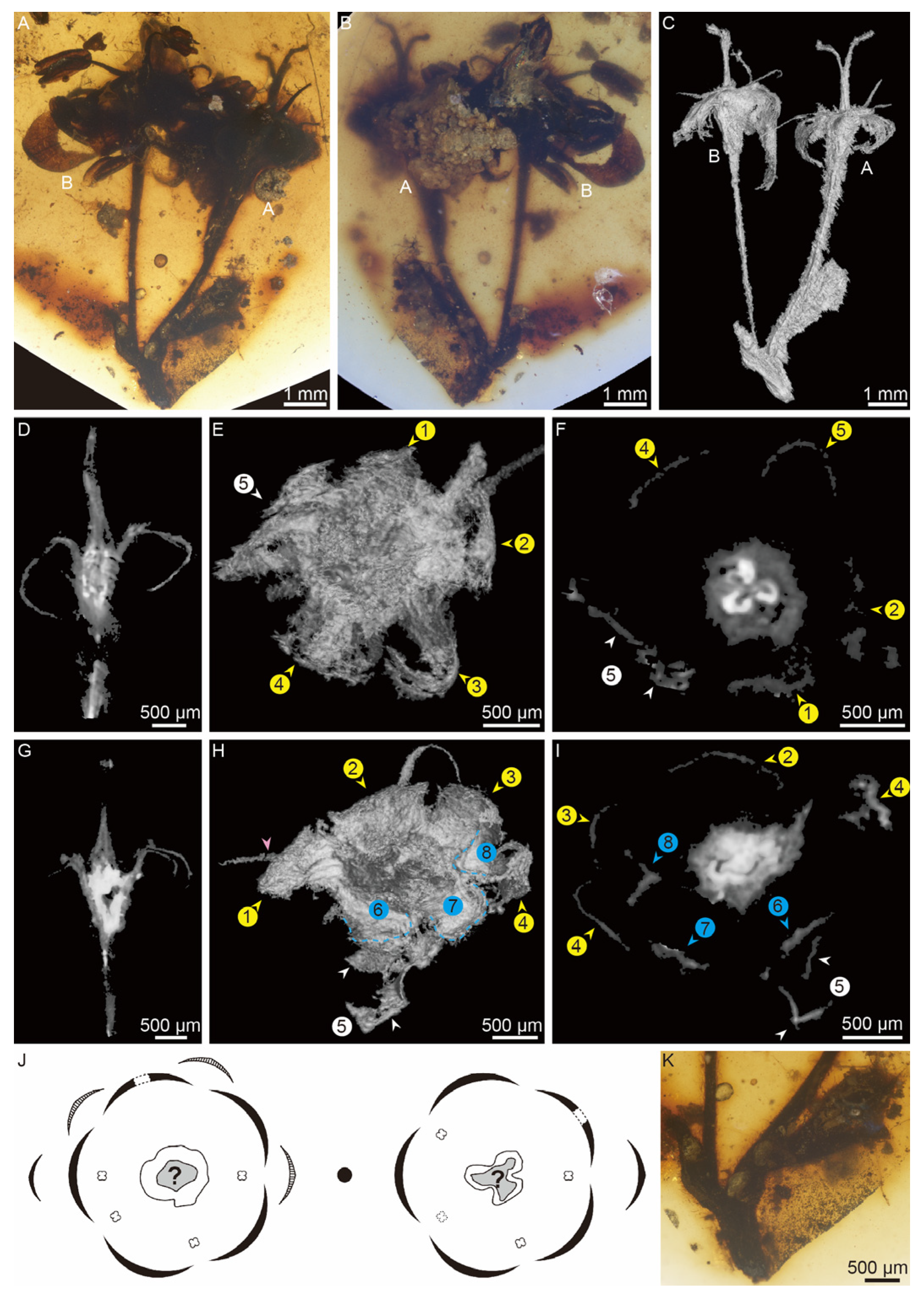

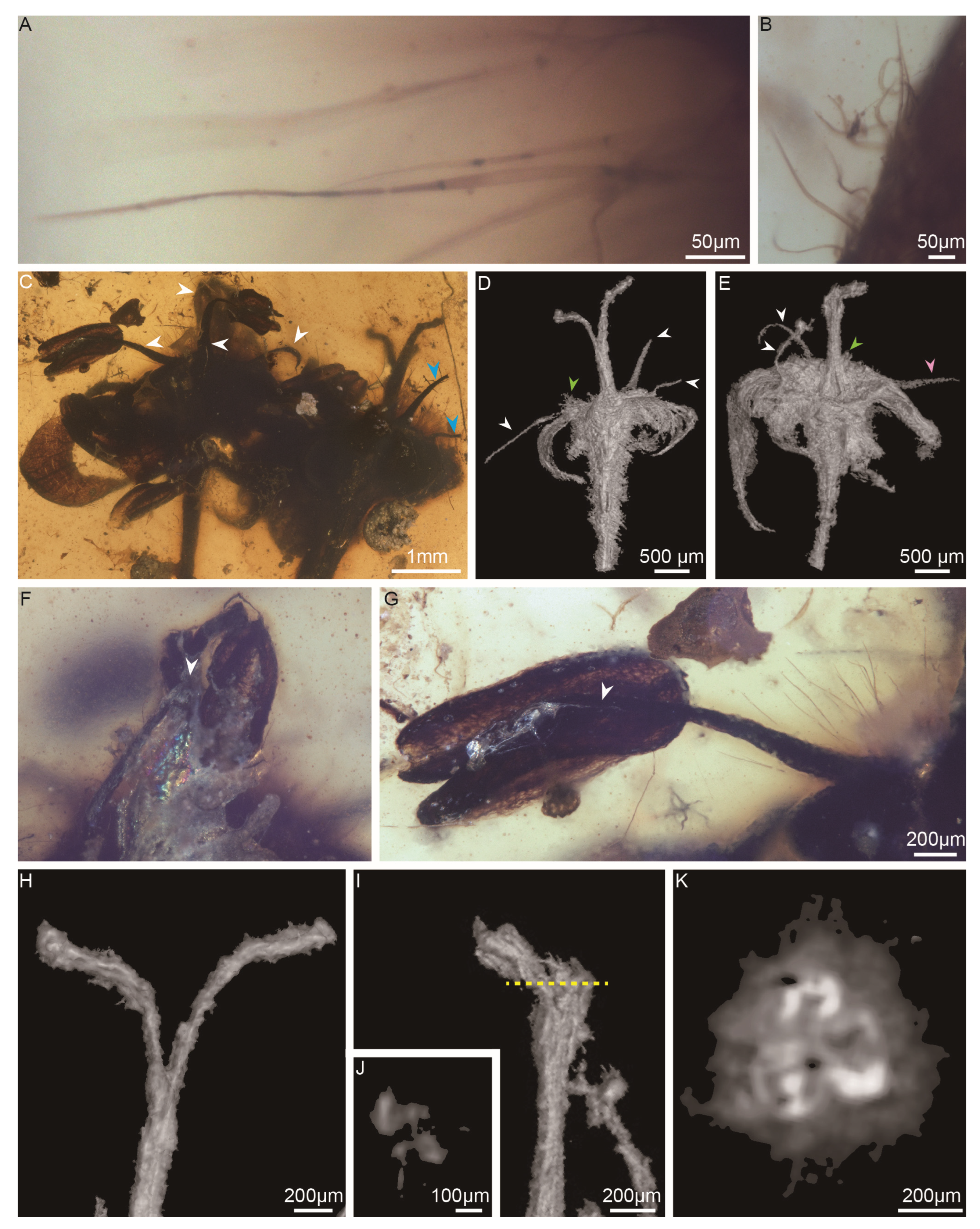

3. Systematics

4. Discussion

4.1. Development of the Paired Flowers

4.2. Comparison with Extant Angiosperms

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Endress, P.K. Flower structure and trends of evolution in eudicots and their major subclades. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 2010, 97, 541–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poinar, G.Jr.; Chambers, K.L.; Buckley, R. Eoepigynia burmensis gen. and sp. nov., an early Cretaceous eudicot flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese Amber. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas 2007, 1, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Poinar, G.Jr.; Chambers, K.L.; Buckley, R. An early Cretaceous angiosperm fossil of possible significance in rosid floral diversification. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas 2008, 2, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, K.; Poinar, G.Jr.; Buckley, R. Tropidogyne, a new genus of Early Cretaceous Eudicots (Angiospermae) from Burmese Amber. Novon 2010, 20, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poinar, G.O.Jr.; Chambers, K.L. Tropidogyne pentaptera, sp. nov., a new mid-Cretaceous fossil angiosperm flower in Burmese amber. Palaeodiversity 2017, 10, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poinar, G.O.Jr.; Chambers, K.L. Tropidogyne lobodisca sp. nov., a third species of the genus from mid-Cretaceous Myanmar amber. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas 2019, 13, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Huang, D.Y.; Cai, C.Y.; Wang, X. The core eudicot boom registered in Myanmar amber. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, E.M.; Pedersen, K.R.; Crane, P.R. The emergence of core eudicots: new floral evidence from the earliest Late Cretaceous. Proc. R. Soc. B 2016, 283, 20161325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester, S.R.; Dilcher, D.L.; Judd, W.S.; Corder, B.; Basinger, J.F. Early Eudicot flower and fruit: Dakotanthus gen. nov. from the Cretaceous Dakota Formation of Kansas and Nebraska, USA. Acta Palaeobot. 2018, 58, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.T.; Yi, T.S.; Gao, L.M.; Ma, P.F.; Zhang, T.; Yang, J.B.; Gitzendanner, M.A.; Fritsch, P.W.; Cai, J.; Luo, Y.; et al. Origin of angiosperms and the puzzle of the Jurassic gap. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.J.; Ma, H. Nuclear phylogenomics of angiosperms and insights into their relationships and evolution. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 546–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, L.X.; Hedges, S.B.; Zhong, B.J. New insights on angiosperm crown age based on Bayesian node dating and skyline fossilized birth-death approaches. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.H.; Grimaldi, D.A.; Harlow, G.E.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, M.C.; Lei, W.Y.; Li, Q.L.; Li, X.H. Age constraint on Burmese amber based on U–Pb dating of zircons. Cretac. Res. 2012, 37, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, R.D.; Ko, K. Geology of an amber locality in the Hukawng Valley, northern Myanmar. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2003, 21, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.A.; Eisenstein, D.; Voet, H.; Gazit, S. Female ‘Mauritius’ litchi flowers are not fully mature at anthesis. J. Hortic. Sci. 1997, 72, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endress, P.K. Disentangling confusions in inflorescence morphology: Patterns and diversity of reproductive shoot ramification in angiosperms. J. Syst. Evol. 2010, 48, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrein, S.; Prenner, G. Unequal twins? Inflorescence evolution in the twinflower tribe Linnaeeae (Caprifoliaceae s.l.). Int. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 174, 200–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A. Pair-flowered cymes in the Lamiales: structure, distribution and origin. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 1577–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, J. Comparative anatomy and morphology of flowers and inflorescences of the Proteaceae. I. Some Australian taxa. Phytomorphology 1959, 9, 325–358. [Google Scholar]

- Haber, J. Comparative anatomy and morphology of flowers and inflorescences of the Proteaceae. II. Some American taxa. Phytomorphology 1961, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.A.S.; Briggs, B.G. Evolution in the Proteaceae. Aust. J. Bot. 1963, 11, 21–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.W.; Tucker, S.C. Inflorescence ontogeny and floral organogenesis in Grevilleoideae (Proteaceae), with emphasis on the nature of the flower pairs. Int. J. Plant Sci. 1996, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endress, P.K.; Igersheim, A. Gynoecium structure and evolution in basal angiosperms. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2000, 161, S211–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igersheim, A.; Endress, P.K. Gynoecium diversity and systematics of the Magnoliales and winteroids. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1997, 124, 213–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronse De Craene, L.P.; Quandt, D.; Wanntorp, L. Floral development of Sabia (Sabiaceae): Evidence for the derivation of pentamery from a trimerous ancestry. Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltis, D.E.; Senters, A.E.; Zanis, M.J.; Kim, S.; Thompson, J.D.; Soltis, P.S.; Ronse De Craene, L.P. .; Endress, P.K.; Farris, J.S. Gunnerales are sister to other core eudicots: Implications for the evolution of pentamery. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronse De Craene, L.P. Meristic changes in flowering plants: How flowers play with numbers. Flora. 2016, 221, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubitzki, K. The families and genera of vascular plants. Volume IX flowering plants. eudicots: Berberidopsidales, Buxales, Crossosomatales, Fabales p.p., Geraniales, Gunnerales, Myrtales p.p., Proteales, Saxifragales, Vitales, Zygophyllales, Clusiaceae Alliance, Passifloraceae Alliance, Dilleniaceae, Huaceae, Picramniaceae, Sabiaceae; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH: Germany, 2007; pp. 418–435. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki, K. The families and genera of vascular plants. Volume VI flowering plants. eudicots. dicotyledons: Celastrales, Oxalidales, Rosales, Cornales, Ericales; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH: Germany, 2004; pp. 202–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki, K. The families and genera of vascular plants. Volume X flowering plants. eudicots: Sapindales, Cucurbitales, Myrtaceae; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH: Germany, 2011; pp. 212–271. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki, K.; Bayer, C. The families and genera of vascular plants. Volume V flowering plants. eudicots. dicotyledons: Malvales, Capparales and Nonbetalain Caryophyllales; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH: Germany, 2003; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit, J.W.; Jeffrey, C. The families and genera of vascular plants. Volume VIII flowering plants. eudicots: Asterales; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH: Germany, 2007; pp. 7–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit, J.W.; Bittrich, V. The families and genera of vascular plants. Volume XV flowering plants. eudicots: Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae); Springer International Publishing AG: Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit, J.W.; Bittrich, V. The families and genera of vascular plants. Volume XIV flowering plants. eudicots: Aquifoliales, Boraginales, Bruniales, Dipsacales, Escalloniales, Garryales, Paracryphiales, Solanales (except Convolvulaceae), Icacinaceae, Metteniusaceae, Vahliaceae; Springer International Publishing AG: Switzerland, 2016; pp. 17–401. [Google Scholar]

| Sepal number | Petal number | Stamen number | Stamen opposite to petals? | Anther attachment | Existence of disk | Style | Ovary position | Carpel number | Placentation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. pilosa | at least 3 | 5 or 6 | at least 4 | yes or no | dorsifixed | no | 2-lobed | half inferior | 3 | unknown |

| Saxifragaceae | (3–)5(–10) | (4)5(6) | 5/5+5 | no | basifixed | no | 2–3 divided | superior to inferior | 2–3 | axile or parietal |

| Rhamnaceae | (3)4–5(6) | (3)4–5(6) | 4–5 | yes | anther minute | yes | 2–4-lobed | superior to inferior | 2–4 | basal |

| Myrtaceae | 4–5 | 4–5 | numerous | / | dorsifixed | yes | solitary | half inferior to inferior | 1–5 | parietal, axile or basal |

| Ancistrocladaceae | 5 | 5 | 10(5, 15) | / | basifixed | no | 3(4)-lobed | half-inferior | 3(4) | pendulous |

| Hydrangeaceae | 4–12 | 4–12, connate | 4–numerous | / | basifixed | no | 1–12 divided | half inferior to inferior | 2–12 | axile at the base and parietal above |

| Loasaceae | (4–)5(–8), connate |

(4–)5(–8), connate |

numerous | / | basifixed | no | solitary | half inferior to inferior | 3–5 | parietal |

| Alseuosmiaceae | 4–5(6), connate | 4–5(6), connate | 4–5(6), connate | no | dorsifixed | yes | solitary | half inferior to inferior | 2–3 | axile |

| Argophyllaceae | 5, connate |

5, connate |

5 | no | basifixed | yes or no | solitary | half inferior to inferior | 1–3 | axile |

| Campanulaceae | (3–)5(–10), connate |

(3–)5(–10), connate | (3–)5(–10) | yes | basifixed | yes | 2–3-lobed | inferior, rarely half inferior or superior | 2–5(–10) | axile |

| Araliaceae | (3–)5(–12), connate |

(3–)5(–12), | 3 –numerous, | / | dorsifixed | yes | 1–numerous | inferior, rarely half inferior or superior | 2–5(–numerous) | apical |

| Torricelliaceae | (3–)5, connate | 5 | 5 | no | basi or dorsifixed | yes or no | 3 divided | inferior | 3 | apical or axile |

| Caprifoliaceae s.l. | 4–5(6), connate | 4–5(6), connate | 4–5 | no | dorsifixed | yes or no | solitary or 2–3-lobed | inferior | 3(2–5) | axile or pendulous |

| Viburnaceae | 2–5, connate |

3–5(6), conate |

3–5(6) | no | basi or dorsifixed | yes or no | solitary or 2–5-lobed | half inferior to inferior | 2-5 | axile or parietal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).