1. Introduction

Shooting is an exceptionally demanding precision sport in which a deviation of only 1 mm at the muzzle can translate into several centimeters of error on the target, directly altering performance outcomes (Ihalainen et al., 2016). Beyond its technical requirements, shooting inherently embraces imperfection and is often perceived as unforgiving: athletes must repeatedly perform under conditions in which even the slightest mistake can determine competitive success or failure. From early developmental stages, shooters are evaluated almost exclusively on results, fostering an environment that cultivates perfectionism, rigid performance tendencies, and heightened vulnerability to self-criticism (Hwang & Chang, 2022). These features make shooting uniquely dependent on advanced psychological regulation, including sustained attentional control, anxiety regulation, emotional flexibility, and the capacity to cope constructively with evaluative pressure. Moreover, recent neurocognitive evidence further shows that elite shooters and archers exhibit enhanced efficiency in attention networks, underscoring the centrality of attentional regulation to precision sport performance (Lu et al., 2021). Importantly, this indicates that the psychological ecology of shooting demands training systems that extend beyond technical routines to foster adaptive responses in a relentlessly evaluative environment.

Traditional Psychological Skills Training (PST) has been widely used to enhance performance across sports. PST generally emphasizes cognitive strategies such as imagery, self-talk, goal setting, biofeedback, and pre-performance routines. In shooting, PST interventions have been particularly evident in cue-based pre-shot routines, attentional focusing techniques, and structured breathing exercises designed to stabilize motor execution. While such tools provide tangible benefits, PST is rooted primarily in control and suppression models. Athletes are encouraged to manage unwanted thoughts, regulate arousal, or eliminate intrusive emotions. However, in static, high-precision contexts such as shooting, excessive attempts to control internal states may paradoxically narrow attentional bandwidth, destabilize fine motor coordination, and undermine trust in established routines. Thus, although PST has a pivotal role in sport psychology, its conceptual and practical limitations in precision-based disciplines highlight the need for complementary frameworks that emphasize acceptance, contextual awareness, and metacognitive flexibility.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a third-wave cognitive-behavioral approach grounded in contextual behavioral science (Hayes, 2011; Hayes & Sackett, 2014), has emerged as one such framework. Rather than attempting to suppress or replace internal experiences, ACT emphasizes six interrelated processes: (1) acceptance of internal experiences without avoidance, (2) cognitive defusion to reduce entanglement with maladaptive thoughts, (3) contact with the present moment to anchor attention, (4) self-as-context to cultivate perspective-taking, (5) values clarification to align behavior with personal meaning, and (6) committed action to sustain effective performance behaviors. Collectively, these processes constitute psychological flexibility (PF), defined as the capacity to persist or adapt behavior in the service of values despite the presence of difficult thoughts or emotions (Hayes, 2019).

Gardner and Moore (2004, 2007) introduced the Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment (MAC) approach as a sport-specific adaptation of ACT, providing a theoretical and applied framework for optimizing performance in competitive settings. Their work established a theoretical foundation for integrating ACT principles into performance enhancement, contrasting with traditional PST’s reliance on suppression and control. Since then, empirical studies have demonstrated the value of MAC and ACT interventions in sport. For example, randomized controlled trials and applied studies have shown improvements in dispositional mindfulness, emotional regulation, and perceived athletic performance across multiple sporting contexts (Josefsson et al., 2019, 2020). More recently, ACT-based interventions have been applied in high-performance environments such as ice hockey, with both feasibility and randomized controlled trials supporting their efficacy in enhancing psychological flexibility and consistency of performance (Lundgren et al., 2020, 2021).

Comparable findings were also reported in elite beach soccer, where a MAC-based program significantly improved rumination, cognitive flexibility, and sport-specific performance outcomes (Sabzevari et al., 2023). Beyond adult elite populations, mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions have also been extended to adolescent athletes, demonstrating feasibility and psychological benefits in developmental high-performance settings (Su et al., 2024). Systematic reviews further confirm that mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions contribute uniquely to resilience, adaptability, and performance enhancement in sport (Noetel et al., 2019). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that ACT and MAC are not novel to sport psychology. The present study, however, addresses the underexplored challenge of translating ACT principles into a structured, discipline-specific, and movement-integrated training system tailored to the psychophysiological demands of elite shooting.

Despite these advances, existing ACT and MAC interventions in sport have exhibited several limitations. Many were implemented as short-term workshops or educational modules, often lacking the repetitive, embodied structure necessary for transfer into sport-specific motor skills. Furthermore, they primarily emphasized clinical or generalized outcomes such as stress reduction, emotional balance, or flow states (Stafford-Brown & Pakenham, 2012; Bernard, 2013; Pears & Sutton, 2021; Ronkainen, N. J., et al., 2025; Ronkainen, H., et al., 2025). Few studies have directly addressed the micro-motor and psychophysiological demands integral to precision sports such as shooting, where the synchronization of breath control, sight alignment, and trigger release constitutes the microstructure of performance (Ihalainen et al., 2016). Consequently, the translation of ACT into a sport-specific psychological training system that incorporates these embodied technical elements remains underdeveloped.

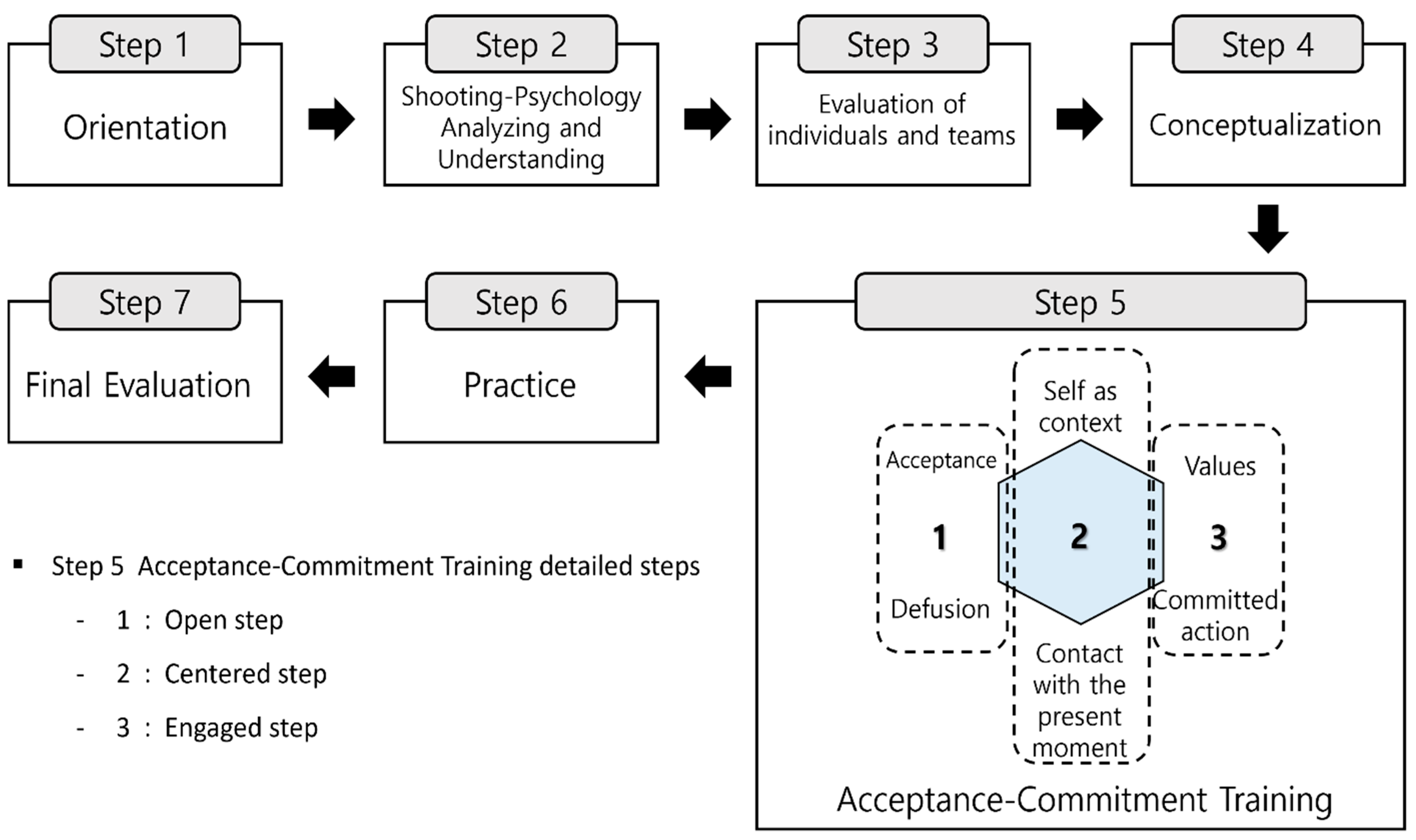

To address this gap, the present study introduces the Acceptance and Commitment Performance Training (ACPT) model and its shooter-specific application (ACPT-S). ACPT restructures ACT principles into a repetitive, movement-based training system designed to align psychological flexibility with the psychophysiological rhythms of elite shooting. Each of ACT’s six processes is strategically embedded into training routines: acceptance is trained through exposure to error and evaluative pressure; cognitive defusion is cultivated via distancing from perfectionistic thoughts; present-moment contact is practiced through respiratory phases and sighting drills; self-as-context is developed by encouraging decentered awareness during pressure simulations; values clarification grounds training in personally meaningful performance standards; and committed action consolidates these processes into replicable pre-shot and in-shot routines. By embedding psychological training within the fine-grained microstructure of shooting, ACPT-S advances ACT from a primarily therapeutic framework toward a discipline-specific psychological skills system.

These principles are further reinforced by the Fascial Circulation Exercise (ACPT-FCE) component, which introduces movement-based practices to reduce co-contraction, stabilize posture, and support proprioceptive clarity. The ACPT-FCE protocol was originally conceptualized as a means of promoting emotional cleansing and psychophysical integration through myofascial flow, aligning psychological flexibility with embodied movement patterns. Prior research on hybrid health models has demonstrated its broader applicability: for example, the HOPE-FIT framework incorporated fascial circulation exercises as embodied psychomotor interventions to enhance somatic–cognitive integration and myofascial flow in older adults (Hwang & Yi, 2025). Similarly, the Movement Poomasi “Wello!” program adapted ACPT-FCE into a digital application, demonstrating that rhythmic, flow-based neuromyofascial activation combined with breathing and sensory alignment can improve circulation, balance, proprioceptive awareness, and emotional self-regulation in community-dwelling older adults (Hwang et al., 2025). These precedents underscore that ACPT-FCE is not merely an adjunct exercise module but a theoretically grounded, evidence-informed method of integrating body-based and acceptance-based training principles within both clinical and performance settings.

Within this framework, psychological flexibility (PF) is not merely a descriptive construct but the mechanistic bridge linking ACT processes to performance. PF is conceptualized as a form of metacognitive attentional regulation: athletes learn to monitor internal cues, flexibly shift attention when disrupted, and re-anchor focus on task-relevant stimuli. This monitor–shift–anchor cycle operates in synchrony with respiratory rhythms and technical phases of shooting, allowing performers to maintain stability under pressure while accommodating internal variability. In doing so, ACPT-S directly addresses concerns about the rationale for PF in precision sports, clarifying its role as a performance-relevant attentional mechanism rather than an abstract psychological concept. Such a model aligns with recent emotion-technical integration frameworks of elite performance (Burns et al., 2022; McLoughlin, G., Roca, & Ford, 2023; McLoughlin, S., & Roche, 2023; Poulus et al., 2024) and provides a compelling rationale for why acceptance-based training is uniquely suited to shooting.

Accordingly, the present study pursues two primary aims: (1) to refine and evaluate the structural coherence and process validity of the ACPT-S framework, and (2) to examine expert evaluations of its theoretical integrity and sport-specific applicability. By explicitly situating ACPT-S within two decades of ACT/MAC research while addressing their translational limitations, this study represents one of the first attempts to evolve ACT into a discipline-specific, movement-integrated performance training system for elite athletes. The ACPT model contributes to advancing sport psychology by (a) demonstrating how ACT principles can be systematically adapted into sport-specific psychological skills training protocols, (b) integrating psychological flexibility with embodied and physiological mechanisms critical to fine motor accuracy, and (c) offering a replicable framework that extends beyond therapeutic applications toward systematic performance enhancement in precision-based sports such as shooting.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

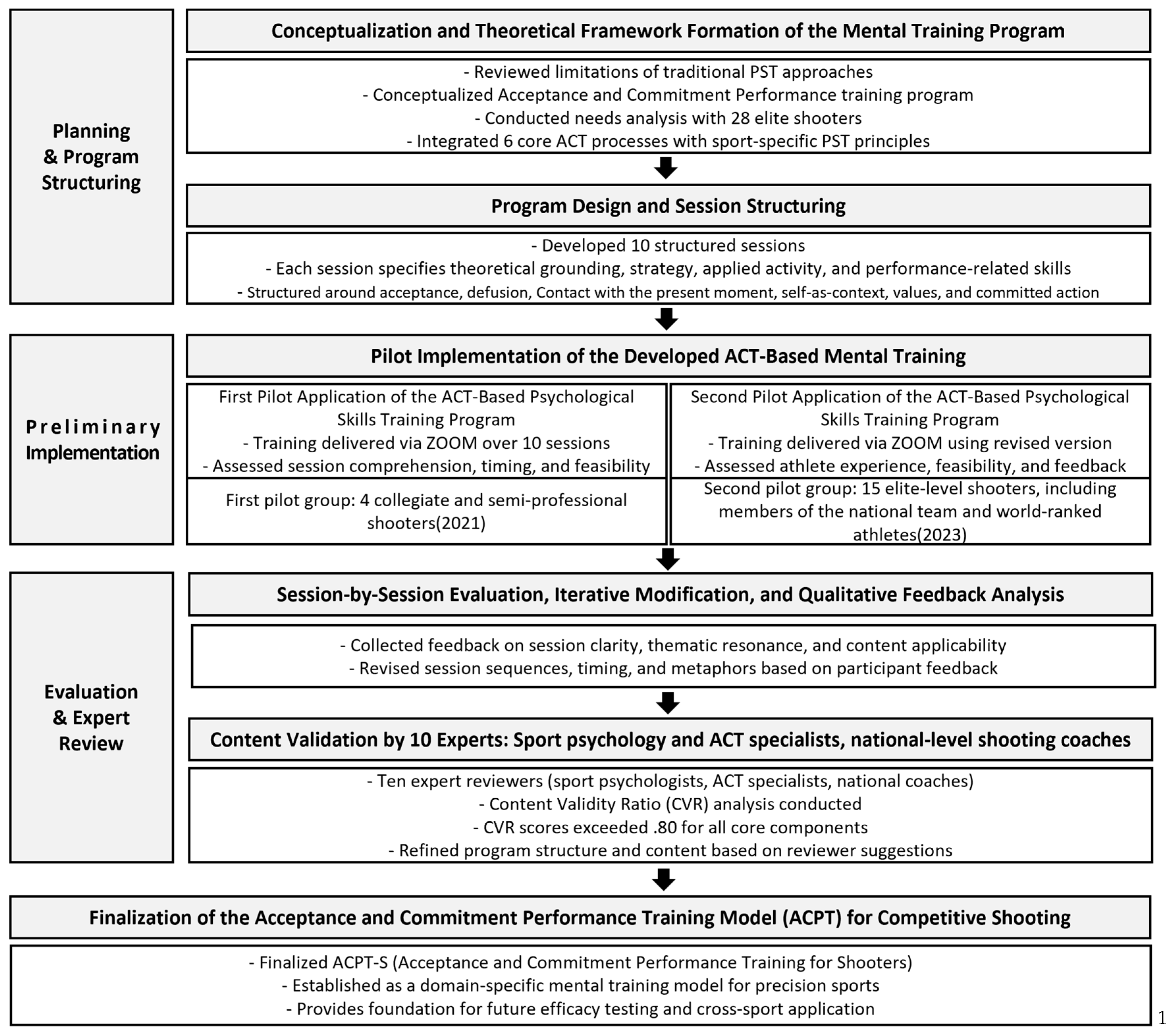

This study employed a multi-phase formative design to develop and preliminarily validate the Acceptance and Commitment Performance Training for Shooters (ACPT-S). The design was reconstructed and extended from Han’s doctoral dissertation (2022) and consisted of two sequential phases:

Development and pilot application of a psychological training module tailored to the sport-specific demands of shooting.

Expert evaluation to assess theoretical coherence and practical feasibility.

Following a formative logic model, the study advanced through a cyclical sequence of needs assessment → theoretical alignment → module construction and iterative refinement → pilot implementation → program adjustment. This design was intentionally selected to integrate contextual, sport-specific requirements with ACT principles, ensuring both ecological validity and theoretical rigor.

The rationale for applying ACT/MAC principles to shooting lies in the sport’s unique psychophysiological demands: unlike dynamic, externally oriented sports, shooting requires synchronization of respiratory control, attentional focus, and fine motor stability under constant evaluative pressure. While the MAC protocol has been successfully implemented in other sports (Gardner & Moore, 2004, 2007; Josefsson et al., 2019, 2020, 2024; Lundgren et al., 2020, 2021), ACPT-S extends this framework by embedding ACT’s six processes into embodied, shooter-specific routines (e.g., breath–release cycles, trigger alignment metaphors). Within this program, psychological flexibility (PF) was operationalized not as an abstract construct but as a mechanism of metacognitive attentional regulation directly linked to performance outcomes.

Table 1 presents the design of the preliminary study. The overall training development and implementation process is summarized in

Figure 1.

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.2.1. Needs Assessment

A total of 28 elite and collegiate-level shooters (rifle and pistol disciplines) voluntarily completed a semi-structured written survey. The survey explored (a) psychological challenges experienced during competitions, (b) prior exposure to mental training, and (c) expectations for the structure and content of a sport-specific psychological skills program. Open-ended responses were thematically analyzed to identify recurrent needs such as perfectionism, attentional lapses under pressure, and difficulties with emotional acceptance. These themes directly informed the construction of ACPT-S session goals and key components.

2.2.2. Pilot Study Participants

Phase 1(2021): Approved by the Korea National Sport University IRB (No. 1263-202106-HR-072-01). Four athletes (2 male, 2 female; Mₐge = 23.0 years; Mₑxp = 9.0 years) from collegiate and corporate teams participated in 10 online sessions delivered via Zoom. Participant characteristics are presented in

Table 2.

Phase 2(2023-2024): Approved by Hanshin University IRB (No. 2023-02-006). Fifteen national-level athletes with international competition experience, including several ranked within the global top tier, took part in the second pilot study. The sample included pistol shooters (4 male, 3 female) and rifle shooters (4 male, 4 female). The average age was 29.4 years, and the mean length of competitive experience was 15.5 years. Participant characteristics are summarized in

Table 3.

2.3. Intervention Overview

The Acceptance and Commitment Performance Training for Shooters (ACPT-S) was designed to systematically integrate the six core processes of Acceptance and Commitment Training (ACT)—acceptance, cognitive defusion, present-moment contact, self-as-context, values clarification, and committed action—into sport-specific routines tailored to the unique demands of shooting. Unlike dynamic sports, shooting requires the fine synchronization of breath control, attentional stability, and motor precision under evaluative pressure; therefore, the ACPT-S protocol emphasized embodied and repeatable routines directly applicable to competition contexts.

Each session of the program was composed of five structured components:

Conceptual overview – introducing the core psychological process of ACT in a sport-relevant context.

Experiential activity – engaging athletes in practical exercises to embody the concept.

Metaphor application – reinforcing understanding through context-sensitive metaphors.

Individual reflection – encouraging athletes to internalize and personalize the learning experience.

Performance linkage – directly connecting psychological processes to shooting-specific skills such as pre-shot routines and trigger control.

The overall theoretical structure of the ACPT-S is presented in

Figure 2 (Final Theoretical Model of ACPT-S), and the preliminary draft of the program’s session organization is illustrated in

Figure 3 (Draft Program Structure). Importantly, this section provides an overview of the program framework; outcome data and the finalized protocol are reported in the Results section.

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Needs Assement

Two open-ended survey questions were posed: (1) “What psychological aspects do you feel need improvement?” and (2) “What kind of support would you like to receive from psychological skills training?” Responses were analyzed to identify specific psychological domains requiring intervention and the types of support most valued by athletes.

2.4.2. Pilot Implementation

Phase 1 (2021): Ten online sessions (60 minutes each) were delivered via Zoom. The focus of this pilot was to assess the structural coherence, delivery flow, and practical feasibility of the initial ACPT-S draft. After each session, participants provided written feedback on comprehension, clarity, and applicability of metaphors. Demographic and athletic information for Phase 1 participants is summarized in

Table 2.

Phase 2 (2023-2024):

The refined ACPT-S was delivered in 10 online sessions to national team athletes exposed to high-performance demands. Following each session, participants completed reflective self-assessment forms, rating attentional control, anxiety regulation, and session relevance on a 5-point Likert scale. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted to capture qualitative insights into participants’ experiences.

Upon completion of the program, a Focus Group Interview (FGI) was conducted to integrate reflections on training engagement and perceived utility. The lead researcher also maintained detailed observational field notes documenting emotional responses, attentional fluctuations, and perceived changes in psychological skills awareness. The characteristics of Phase 2 participants are presented in

Table 3.

2.5. Measures and Data Sources

Self-report: Post-session questionnaires (5-point Likert scale) assessing attentional control, anxiety regulation, and perceived session relevance.

Qualitative data: Open-ended survey responses (needs assessment), session reflections, semi-structured interviews, FGI transcripts, and researcher field notes

Expert review: Training manuals, worksheets, and evaluation sheets reviewed by a panel of experts. Expert panel demographics are summarized in

Table 4.

Interview protocols were developed using a structured item-construction framework to explore subjective changes in depth, consistent with qualitative research standards (Taylor, 2017).

2.6. Data Analysis

Quantitative: Descriptive statistics (means, SDs) were calculated for post-session Likert ratings. Inferential statistics were not conducted due to the small pilot sample.

Qualitative: Data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step thematic analysis (familiarization, coding, theme generation, theme review, naming/defining, reporting). Triangulation across self-reports, interviews, and field notes ensured analytic rigor.

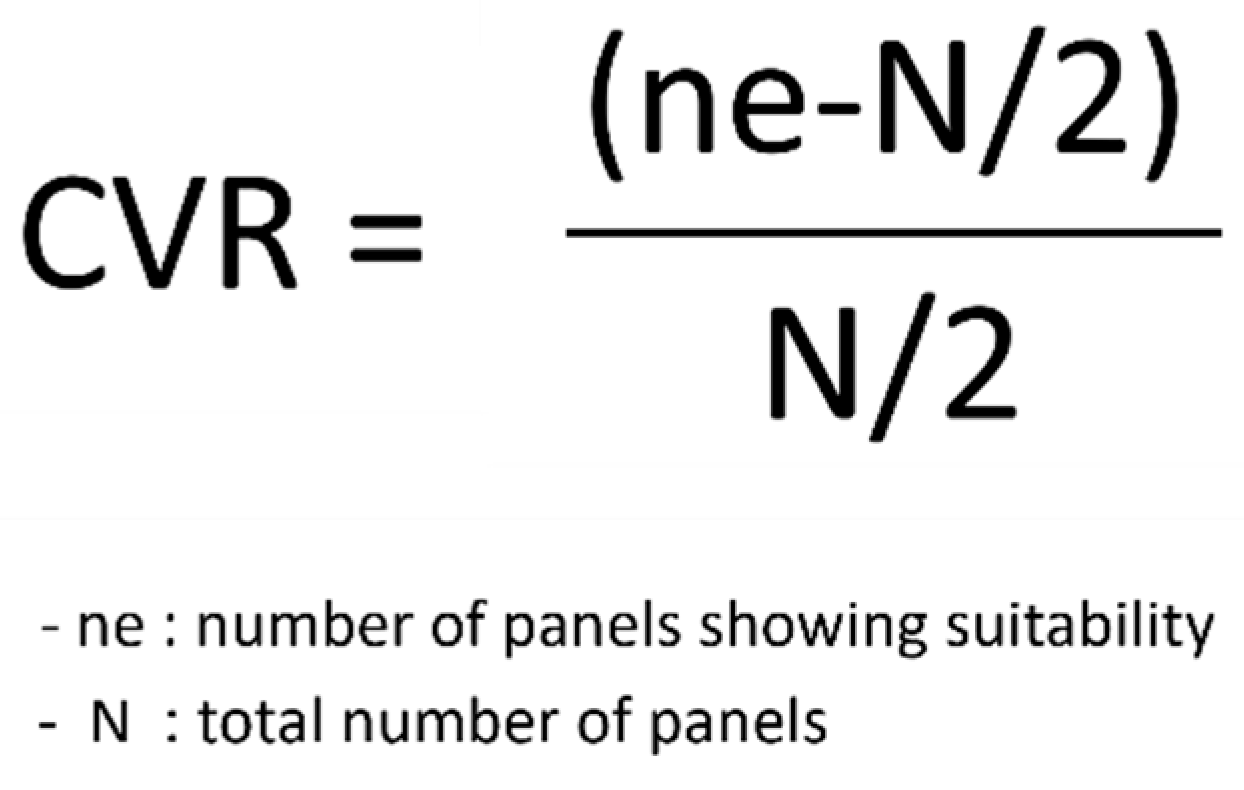

Content Validity: Lawshe’s (1975) Content Validity Ratio (CVR) was computed for expert panel ratings, with the threshold for a 10-member panel set at .62. The calculation formula is presented in

Figure 4.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the Expert Panel on Sport and ACT Counseling (n = 10).

Table 4.

Characteristics of the Expert Panel on Sport and ACT Counseling (n = 10).

| Group |

Gender |

Coaching Experience (years) |

Athletic Experience (years) |

Position |

Sport |

Shooting

Expert |

M |

30 |

10 |

National Coach |

Shooting |

| F |

- |

10 |

Active Athlete |

Shooting |

| Group |

Gender |

Teaching

Experience

(years)

|

Research

Experience

(years)

|

Sport

Psychology

Counseling

Experience

(years)

|

ACT

Counseling

Experience

(years)

|

Sport |

Sport

Psychology

Counseling

Expert |

F |

25 |

20 |

20 |

6 |

Shooting |

| M |

24 |

20 |

18 |

18 |

- |

| M |

13 |

13 |

13 |

- |

Golf |

| M |

20 |

15 |

10 |

1 |

Track |

| M |

12 |

14 |

- |

13 |

- |

| M |

10 |

16 |

10 |

5 |

Taekwondo |

| M |

9 |

12 |

9 |

- |

- |

| M |

3 |

8 |

7 |

- |

- |

3. Trustworthiness and Ethical Considerations

3.1. Ethical Approval and Participant Rights

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Korea National Sport University (IRB No. 1263-202106-HR-072-01; Approval Date: June 17, 2021) and Hanshin University (IRB No. 2023-02-006; November 13, 2023). Phase 1 was conducted from June 17 to November 6, 2021, and Phase 2 from November 13, 2023 to June 17, 2024.

All participants received detailed information regarding the research purpose, procedures, and voluntary nature of participation. Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Participants voluntarily completed surveys, activity worksheets, and feedback forms, and their confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained throughout the study. No personally identifiable information was disclosed in the results or publications.

3.2. Trustworthiness and Rigor

To establish the trustworthiness of this qualitative inquiry, the study employed multiple validation strategies grounded in Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) four foundational criteria: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Building upon these principles, we further integrated contemporary insights from Adler (2022), who emphasized that trustworthiness must be understood as a reflexive, dynamic, and ethically engaged process that is maintained throughout the lifecycle of the research.

To enhance credibility, data triangulation was performed using open-ended surveys, semi-structured interviews, session-specific reflective feedback, and observational field notes. This multi-perspective approach fostered analytic depth and internal coherence (Breitmayer et al., 1993; Donkoh, 2023).

Investigator triangulation was also implemented through collaborative coding and consensus discussions among qualitative experts to minimize interpretive bias. Peer debriefings were held at multiple stages with ACT-trained clinicians and sport psychology professionals to ensure theoretical consistency and contextual appropriateness.

Member checking involved returning thematic summaries to a subset of participants to verify the resonance and authenticity of the interpretations (Birt et al., 2016). This procedure reinforced the alignment between researcher interpretations and participant perspectives.

To promote transferability, the study included detailed descriptions of participant profiles, training environments, and implementation protocols, enabling readers to evaluate the relevance of findings in similar elite sport contexts.

Dependability was established through transparent documentation of research phases, methodological decisions, and program development processes. An audit trail was maintained, reflecting iterative adaptations and ensuring analytic accountability.

Confirmability was addressed by maintaining reflexive journals and collecting external reviews from ACT experts and sport psychologists. Their feedback helped confirm the fidelity of the intervention to the ACT model while also ensuring cultural and contextual relevance (Hayes et al., 2011).

In sum, this study adhered not only to established standards of qualitative rigor but also to modern perspectives that regard trustworthiness as an evolving, ethically grounded process (Adler, 2022). All procedures were carried out following IRB approval and in strict compliance with international ethical standards.

4. Researcher Positionality

This study was conducted by Dr. Suyoung Hwang and Dr. Woori Han, both Ph.D.-level scholars in sport psychology. They collaborate with a shared practitioner-scholar orientation, committed to promoting the psychological well-being and performance enhancement of elite athletes by bridging research and applied practice.

Dr. Woori Han initially conceptualized the Acceptance and Commitment Performance Training framework for elite shooters in her 2021 doctoral dissertation—the first of its kind in Korea. Her earlier work included designing ACT-based interventions to promote psychological flexibility in middle- and long-distance runners during her master’s program and developing an ACT training program to help college athletes manage COVID-19-related stress during her doctoral studies. Through years of field application and academic engagement, Dr. Han has cultivated top-tier expertise in ACT implementation within sport contexts.

She holds a Level 1 certification in sport psychology counseling (KSSP), has completed both the basic and advanced sport mental coaching curricula, and has provided individual and group consultations to elite athletes across track and field, judo, archery, badminton, and e-sports. In addition, she actively participates in these disciplines as a recreational athlete to deepen her experiential insight. A certified ACT Level 2 practitioner, Dr. Han has been actively involved in national psychology conferences and workshops since 2015 and has delivered over 100 ACT-based sessions through the Gangwon Sports Council, supporting performance enhancement beyond the shooting domain.

Dr. Suyoung Hwang is a former national skeet shooter with over a decade of elite-level experience. She holds an official shooting coach license and has completed the Level 1 sport psychology counseling curriculum through KSSP. As a research professor, she bridges academic inquiry with athletic practice. Dr. Hwang also holds an internationally accredited MBTI certification and actively engages in professional development across mindfulness, ACT, and performance-based psychological interventions. In this study, she contributed significantly to strengthening the structural design and validating the program through both qualitative and quantitative analyses.

As insider researchers, both authors possess a profound understanding of the psychological and cultural nuances within the Korean elite sport system. Aware of the potential for interpretive bias, they implemented multiple strategies—including triangulation, external consultation, and independent coding procedures—to ensure analytical rigor and uphold the trustworthiness of the research (Morrow, 2005).

5. Results

5.1. Sample Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of participants across both pilot phases are summa rized in

Table 2 (Phase 1, 2021) and

Table 3 (Phase 2, 2023–2024).

Phase 1 involved four collegiate and corporate team athletes (2 male, 2 female; M_age = 23.0 years; M_experience = 9.0 years).

Phase 2 included 15 national-level shooters (7 pistol, 8 rifle), many with international competition experience and global top-tier rankings (M_age = 29.4 years; M_experience = 15.5 years).

These cohorts provided distinct developmental contexts: Phase 1 offered preliminary feasibility data, whereas Phase 2 involved validation in a highly competitive population.

5.2. Needs Assessment Validation

Thematic analysis of open-ended survey responses (N = 28) identified three major psychological domains requiring improvement: worry and rumination (21.4%), anxiety and tension (21.4%), and diminished mental toughness (21.4%). Additional themes included concentration, emotional regulation, and self-confidence (see

Table 5).

When asked about the type of psychological support desired, the most frequently cited response was mental toughness enhancement (42.9%), followed by tension management (14.3%), anxiety regulation (14.3%), and concentration (7.1%) (see

Table 6).

These findings highlighted athletes’ vulnerability to cognitive overload and emotional strain in competitions, while underscoring their dissatisfaction with uniform PST methods and desire for individualized, context-sensitive interventions.

Importantly, these needs not only identified psychological vulnerabilities but also directly informed the construction of the hybrid theoretical model (see

Section 5.3), ensuring that program design was empirically grounded in athlete-derived demands.

5.3. Theoretical Model Output

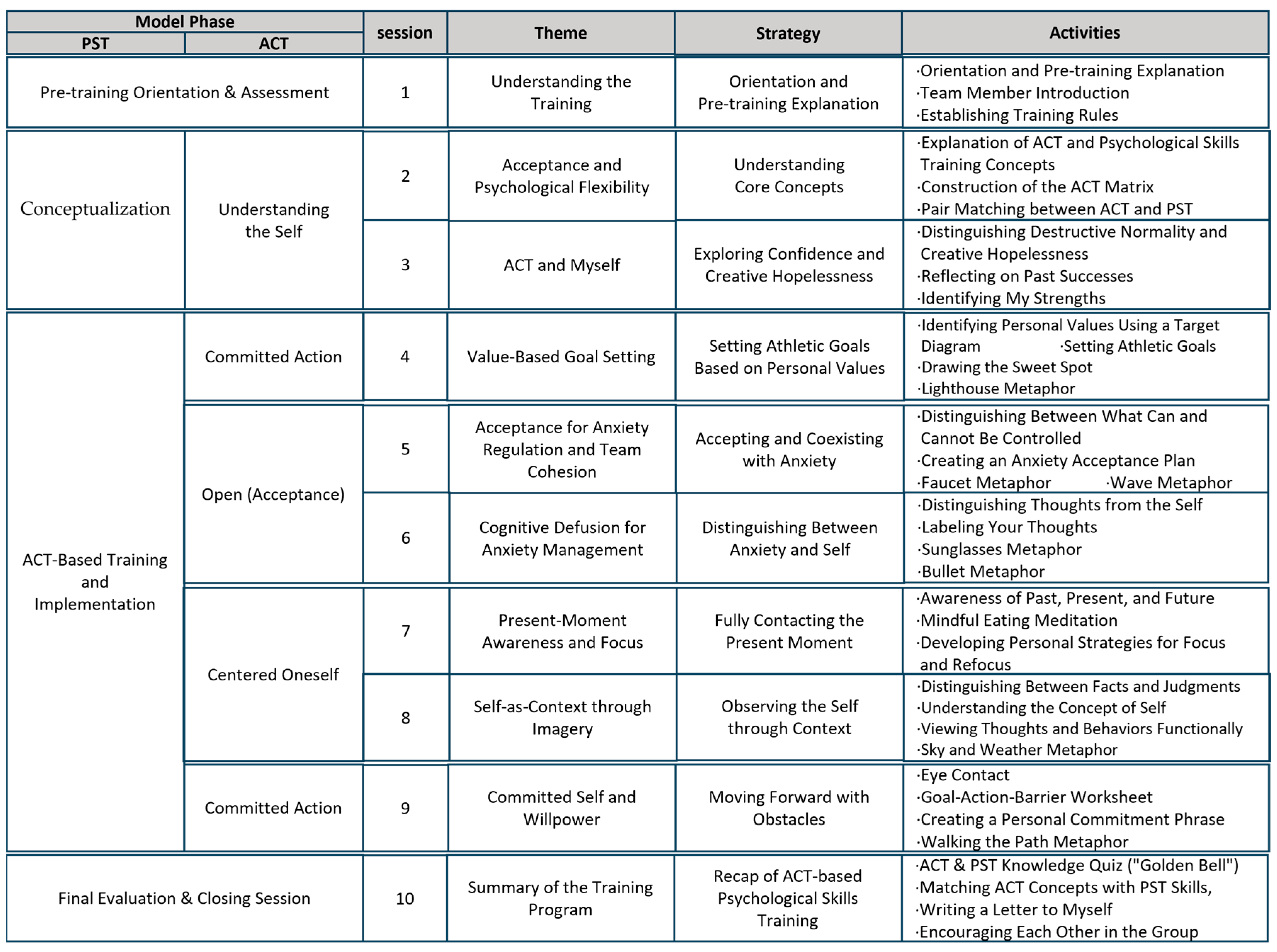

Integrating literature evidence with needs assessment results, a hybrid theoretical framework was constructed that combined ACT’s six processes (acceptance, cognitive defusion, present-moment contact, self-as-context, values, and committed action) with educational progressions from PST (Morris & Thomas, 1995; Boutcher & Rotella, 1987).

The resulting ACPT-S model (see

Figure 2) provides a participant-centered, context-sensitive framework tailored to the static, precision-based demands of shooting. This theoretical model was further elaborated into a draft program structure comprising ten sequential sessions, illustrated in

Figure 3.

5.4. Pilot Validation

5.4.1. Operational Evaluation

The program was successfully implemented across both phases. Sessions generally proceeded as planned, but minor issues were observed: inadequate explanation of transfer during Session 3 and excessive activity load during Session 4, leading to time overruns. These insights indicated the need for better allocation of activities and improved instructional clarity.

Despite occasional technical challenges (e.g., intermittent internet disconnections), the online delivery format was found feasible and facilitated uninterrupted training, even under pandemic restrictions. Notably, in Phase 2, athletes’ engagement and concentration improved across sessions, supporting the practicality of the program.

5.4.2. Process Evaluation

Qualitative reflections revealed positive experiential outcomes, including:

Improved emotional acceptance (“Observing my thoughts and myself from a third-person perspective helped me approach problems more calmly”).

Enhanced attentional control and self-awareness.

Increased trust in self through defining ACT concepts in their own words.

Enjoyment from value-based activities and personalized engagement due to the small group setting.

Representative quotations are summarized in

Table 7.

5.4.3. Outcome Evaluation

Analysis of post-program interviews and FGIs indicated four key areas of psychological change:

Internalization of ACT principles: athletes reported cognitive defusion and increased psychological flexibility (e.g., shifting from suppression to acceptance of negative emotions).

Selective attentional focus: prioritizing solvable problems while letting go of uncontrollable concerns.

Enhanced tolerance of negative emotions and reduced rumination.

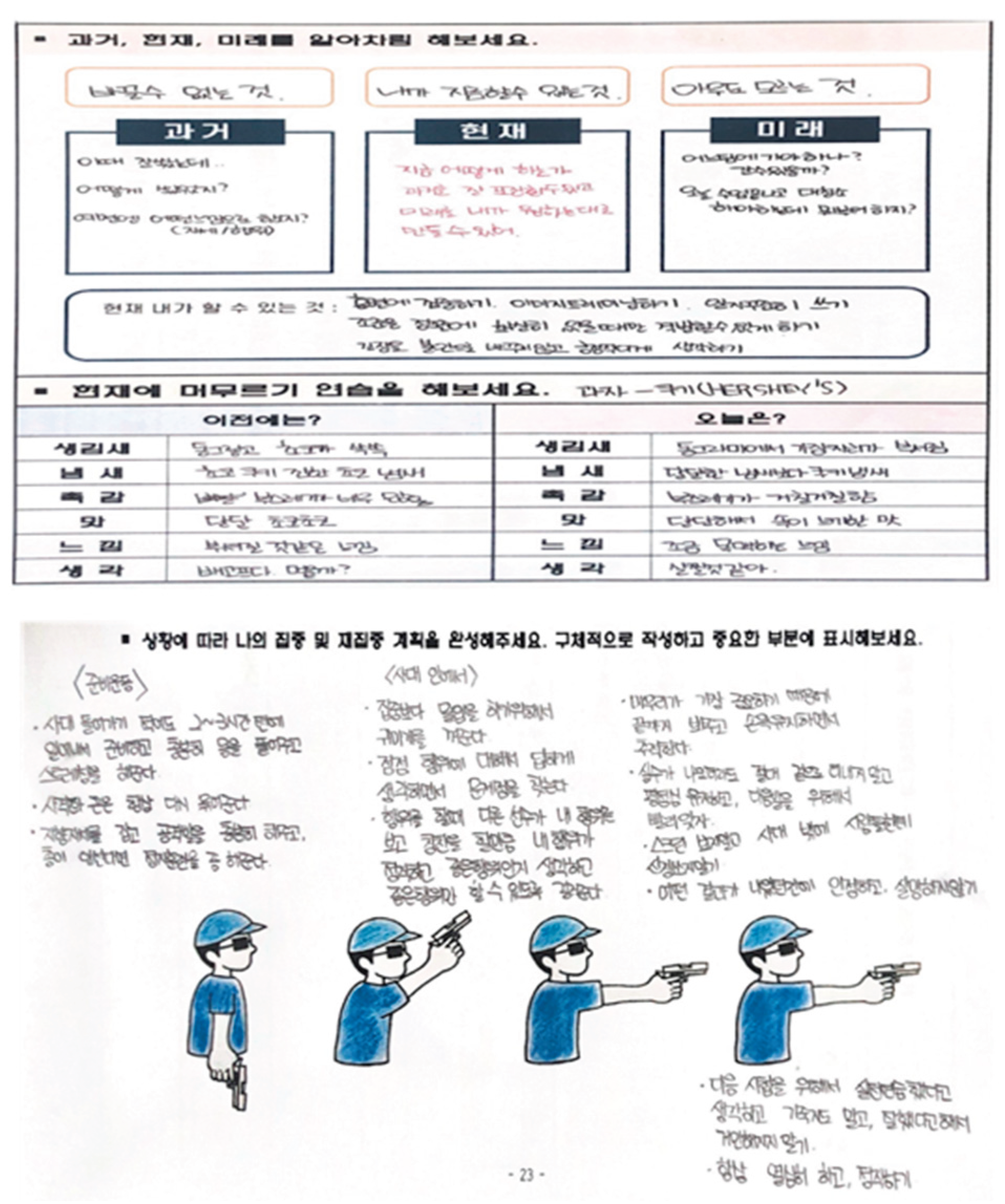

Expanded temporal self-awareness, integrating past, present, and future perspectives.

Illustrative responses are summarized in

Table 8, confirming that ACPT-S facilitated both skill acquisition and meaningful psychological transformation.

A representative example of the applied session activity (Session 8) is provided in

Figure 5.

Collectively, these outcomes provided empirical justification for refining metaphors, sequencing activities, and enhancing reflective components, thereby feeding directly into the finalization stage of the ACPT-S.

Table 7.

Process Evaluation from the Pilot Study.

Table 7.

Process Evaluation from the Pilot Study.

| Participants’ Reflections on the Benefits of Acceptance and Commitment Performance Training |

|---|

| A |

Observing my thoughts and myself from a third-person perspective without judgment helped me realize that the problems were not as severe as they seemed. Applying this perspective to my daily life was highly effective—it helped relieve more than half of the worries and concerns that had been overwhelming my mind. |

| B |

I enjoyed the activity where we visualized the most joyful moments in our lives.

It was fun and engaging. |

| C |

The training that involved defining elements of ACT in my own words was especially meaningful. Through this process, I came to trust myself more and realized that the answers lie within me. I also learned to better understand my thoughts and emotions and to view myself more objectively. |

| D |

Writing a letter of encouragement to myself and setting personal exercise goals were particularly helpful. Because the sessions involved only a small number of participants, each individual could fully engage in the training and accurately identify areas for personal improvement. |

Table 8.

Outcome Evaluation from the Pilot Study.

Table 8.

Outcome Evaluation from the Pilot Study.

| Participants’ Reflections on Psychological Changes after ACT-Based Training |

|---|

| A |

During the course, I applied what I learned to address major worries and concerns and found it very effective. Negative thoughts became more positive, and by looking at my problems from a third-person perspective, I was able to approach them more calmly. |

| B |

I now focus only on the problems I can solve and no longer dwell on those I cannot. |

| C |

I used to suppress or ruminate on negative emotions and thoughts. Through the training, I learned to face and accept them from a third-person perspective. Now I can respond more adaptively to similar situations. |

| D |

I gained insight into what is needed across past, present, and future timelines. |

Figure 5.

Representative example from the 10-session ACPT program.

Figure 5.

Representative example from the 10-session ACPT program.

5.5. Expert Validation

A panel of ten experts (eight ACT-trained sport psychologists and two national-level shooting coaches) evaluated the final draft of the ACPT-S program. Content Validity Ratio (CVR) scores exceeded the minimum threshold (.62) across all items, with all items rated at CVR ≥ .80, indicating strong expert agreement (see

Figure 4 and

Table 9).

Qualitative feedback emphasized:

The importance of providing clearer explanations of ACT concepts.

The need for adjusted time allocation to prevent disengagement.

Prioritizing participant reflection over excessive activity load.

Designing tasks that allow continued practice beyond sessions.

A synthesis of expert recommendations is presented in

Table 10, which highlighted the necessity of balancing conceptual depth with practical engagement.

5.6. Program Finalization as Validation Output

Based on pilot findings and expert validation, the ACPT-S protocol was finalized into a 10-session standardized format. Each session followed five structured components:

This final version (see Figure 6) established ACPT-S as a domain-specific intervention tailored to the psychophysiological demands of elite shooters.

Importantly, the finalization stage represented not only a programmatic output but the culmination of a multi-layered validation process. Activity and metaphor selection had been systematically grounded in prior ACT and PST literature (Johnson et al.,2023;Kang, 2016; Son, 2020; Stoddard et al., 2014), and refined through cultural adaptation for Korean elite shooters. Pilot implementation further highlighted which exercises were intuitive, engaging, and functionally applicable in shooting contexts (e.g., “Creative Hopelessness Sharing,” “Fact vs. Judgment,” “Sky and Weather Metaphor”). Finally, the expert panel’s CVR analysis confirmed the conceptual clarity and contextual appropriateness of these activities, while qualitative feedback emphasized the need for improved time allocation, clearer explanation of ACT concepts, and stronger links to athletes’ daily training routines.

Thus, finalization represents the closure of a formative validation cycle that integrated:

Iterative pilot testing with feedback loops (

Table 2 and

Table 3, 7–8), and

Through this cumulative process, the ACPT-S was validated as both theoretically sound and practically feasible, positioning the program for subsequent large-scale empirical testing.

5.7. Session-Level Program Highlihts

The validated ACPT-S framework was operationalized into session-level activities that directly embedded ACT processes into the microstructure of shooting performance. Key highlights include:

Self-Understanding: Activities such as Creative Hopelessness Sharing and the ACT Matrix (Krafft et al., 2017) guided athletes to recognize limitations of avoidance-based coping and fostered motivation for change. In addition, the concept of self-compassion was introduced, emphasizing support over control or avoidance in dealing with distress. Research indicates that self-compassion positively influences confidence in performance and anxiety regulation (Terry & Leary, 2011), thereby strengthening athletes’ internal motivation and resilience.

Values: Introduced early using the “Value Target Tool,” enabling athletes to connect training goals with personal and performance-related values. This design aligns with recent evidence that clarifying performance-related values enhances motivation and sustainable goal pursuit among elite athletes (Su et al., 2024). By linking values to concrete training behaviors, shooters were able to maintain clarity and persistence under evaluative pressure.

Acceptance: Metaphors such as the faucet and Olympic surfing wave were combined with Anxiety–Acceptance Plans to cultivate openness in evaluative contexts. Consistent with findings from Sabzevari et al. (2023), acceptance-based strategies improved cognitive flexibility and reduced maladaptive rumination, allowing athletes to remain functional under performance stress.

Cognitive Defusion: Exercises like “Fact vs. Judgment” and the “Sunglasses Metaphor” promoted flexible distancing from anxiety-laden thoughts. Recent studies highlight that defusion practices not only reduce the believability of negative thoughts but also facilitate attentional reallocation toward task-relevant cues (McLoughlin et al., 2023), which is particularly critical in precision sports such as shooting.

Present-Moment Awareness: Practices such as “Noticing Past–Present–Future” and eating meditation enhanced attentional anchoring and refocusing strategies. Research on elite shooters and archers (Lu et al., 2021) shows that maintaining present-moment awareness is directly linked to efficiency in attention networks, validating the inclusion of mindfulness-based attentional resets within the ACPT-S framework.

Self-as-Context: The Sky and Weather Metaphor, imagery practices, and functional perspective activities expanded athletes’ awareness of self beyond transient internal states. By cultivating decentered awareness, athletes reported greater tolerance of fluctuating emotional states, consistent with evidence that perspective-taking supports resilience and psychological well-being in high-performance contexts (Ronkainen et al., 2025).

Committed Action: Goal–Action–Barrier planning and commitment phrases reinforced persistence and value-driven behavior, even under pressure. These strategies operationalized the transition from abstract values to concrete actions, ensuring that performance routines remained aligned with both athletic and personal goals, a link emphasized in recent ACT-based sport interventions (Pears & Sutton, 2021).

These highlights were not merely descriptive but constituted validated components, consistently reinforced by pilot participants’ feedback (

Table 7 and

Table 8) and expert review (

Table 9 and

Table 10). Unlike conventional PST methods that emphasize control and suppression (e.g., imagery or arousal regulation), ACPT-S operationalized acceptance-based processes into embodied sport-specific routines, thereby bridging metacognitive flexibility with the psychophysiological microstructure of shooting performance.

6. Discussion

This study developed and preliminarily validated a psychological skills training program for elite shooters based on the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) model. While ACT has traditionally been applied in therapeutic contexts, this study reinterpreted ACT as a structured performance training (ACPT) model tailored to high-performance sports. The shift from “therapy” to “training” reflects a fundamental innovation, positioning ACT not as a remedial tool but as a proactive method to cultivate mental agility, attentional control, and emotional resilience in elite athletic contexts.

In contrast to conventional Psychological Skills Training (PST), which emphasizes self-regulation, goal setting, and behavioral routines, ACPT incorporates core ACT principles—acceptance, cognitive defusion, mindfulness, values clarification, and committed action—to enhance athletes’ psychological flexibility and performance sustainability. By explicitly integrating these metacognitive processes into sport-specific performance routines (e.g., breath–release cycles, trigger alignment), ACPT-S directly addresses the psychophysiological demands of shooting while also compensating for PST’s limitations, such as its insufficient focus on acceptance-based coping.

The findings of the pilot study indicated that participants experienced meaningful psychological and behavioral changes, including enhanced self-awareness, value alignment, attentional refocusing, and improved emotional coping. The process and outcome evaluations revealed that participants internalized key concepts, such as acceptance and defusion, and applied them to real-life performance and personal challenges. This supports the growing view that ACT is not only effective in clinical populations but also highly relevant in performance-based domains.

Expert evaluation further confirmed the content validity and field applicability of the program. All session components scored above .80 on the Content Validity Ratio (CVR), exceeding Lawshe’s (1975) minimum criterion for 10 raters. Qualitative feedback also supported the clarity of conceptual explanations, appropriate time allocation, and the logical sequencing of activities. Importantly, the validation process was not limited to expert review alone but integrated needs assessment, iterative pilot refinement, and structured expert evaluation—together constituting a multi-layered validation framework.

A distinctive feature of ACPT is its structured progression through ACT’s six core processes, aligned with sport-specific psychological constructs. This structure enables athletes to navigate the internal landscape of performance anxiety, self-doubt, and identity confusion by cultivating meta-awareness and action-oriented commitment. For example, the integration of metaphors (e.g., the faucet, waves, sunglasses, and sky weather) with mindfulness and reflection activities supported athletes in differentiating between experiential reality and reactive narratives, fostering psychological distance and cognitive flexibility.

Crucially, this study offers an expanded theoretical framework that bridges ACT with PST. Instead of treating PST as a competing framework, ACPT-S incorporates PST’s educational progression model (Morris & Thomas, 1995; Boutcher & Rotella, 1987) while embedding ACT’s acceptance-based principles. This hybridization provides both structure and flexibility, thereby addressing limitations of traditional PST while enhancing its ecological validity in precision-based sports.

In summary, this study contributes a theoretically grounded and practically validated ACT-based training model that redefines the development of psychological skills in sports. Future studies should examine the longitudinal effects of the ACPT and its adaptation to various performance environments. Ultimately, the ACPT framework positions psychological flexibility as a core competency in elite performance, one that can be cultivated through deliberate, structured, and value-driven mental training.

7. Limitations

Despite these contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged to ensure a balanced interpretation of the findings.

First, the pilot studies involved relatively small samples, particularly in Phase 1 (n = 4). Although such constraints are common in elite sports research due to the limited availability of high-performance athletes, the small sample size restricts generalizability. Future studies should therefore employ larger and more diverse samples across age groups, competitive levels, and cultural contexts.

Second, while ACPT-S was explicitly positioned as an advancement over conventional PST, this study did not include a direct comparison group receiving PST. Thus, although the rationale for addressing PST’s limitations—such as its reliance on uniform routines and limited emphasis on acceptance—was articulated, comparative effectiveness remains untested. Future randomized controlled trials directly contrasting PST and ACPT-S are needed.

Third, the validation process relied primarily on formative evaluation (needs assessment, pilot implementation, and expert review), rather than longitudinal performance outcomes. While this approach ensured ecological validity and allowed systematic refinement, the absence of long-term follow-up across competitive seasons leaves questions about the durability of program effects. Future research should incorporate prospective, longitudinal designs to test sustained efficacy.

Fourth, the delivery format was fully online due to contextual restrictions such as COVID-19. While feasible and effective, participants noted that face-to-face delivery might have provided deeper experiential engagement, particularly in metaphor-based and group-reflective activities. Hybrid delivery models should therefore be tested to optimize accessibility without compromising depth.

Finally, although metaphors and exercises were tailored for Korean shooters, their interpretation may vary across cultures. Cross-national adaptation and cultural validation studies are essential to ensure global applicability of ACPT-S.

By acknowledging these limitations, this study provides a transparent account of its scope and sets clear directions for more rigorous, comparative, and longitudinal research.

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study developed an ACT-based psychological skills training program (ACPT-S: Acceptance and Commitment Performance Training for Elite Shooters) specifically designed for elite shooting athletes and examined its preliminary validity. A needs assessment identified the psychological demands of competitive shooting, guiding the program’s content and structure. The program was refined through iterative pilot implementation and expert validation, establishing both its feasibility and field applicability.

This work makes several theoretical and practical contributions. First, it offers an integrative model bridging ACT’s six processes with foundational PST concepts, positioning ACPT-S as a hybrid framework that overcomes the limitations of traditional PST while maintaining its structured progression. Unlike conventional approaches that focus narrowly on either clinical or performance domains, ACPT-S unifies perspectives to foster holistic psychological development in elite athletes.

Second, the final version of ACPT-S was tailored to the real-world demands of shooters. Structured around seven modules—self-understanding, value clarification, acceptance, cognitive defusion, present-moment awareness, self-as-context, and committed action—it delivers a comprehensive psychological training pathway. Importantly, this study reconceptualized ACT as a proactive training paradigm, not merely as clinical therapy, thereby expanding its scope from rehabilitation to high-performance enhancement.

Third, ACPT-S addresses long-acknowledged limitations of PST by introducing strategies that cultivate psychological flexibility: the ability to remain open, focused, and committed to valued actions under pressure. This adaptability makes ACPT-S suitable for diverse sports, age groups, and competition levels, while reframing mental training as not merely performance-oriented but meaning-oriented, aligning achievement with personal values and long-term well-being.

Future research (Study 2) should empirically examine the long-term impact of ACPT-S, its direct effects on competition outcomes, and its adaptability to other sports contexts. Integration of digital technologies—such as sensor-based focus tracking, biofeedback, and app-based self-practice modules—represents a promising direction to enhance scalability, accessibility, and precision in delivery.

Ultimately, this study redefines ACT not as a therapeutic intervention but as a rigorously validated training framework for high-performance contexts. By embedding ACT within the architecture of sport-specific psychological training, ACPT-S sets the stage for a new paradigm of resilience through flexibility, performance through presence, and success through values-driven action.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: W.H. and S.H. Methodology: W. H. and S. H. Validation: S.H. and W.H. Formal analysis: W.H. and S.H. Resources: W.H. Writing-original draft preparation: S.H. Writing-review and editing: W.H. Supervision: E.S.Y and S.H. Funding acquisition: E.S.Y. All authors read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research funded by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the Na-tional Research Foundation of Korea, NRF-2021S1A5C2A02089245/NRF- 2022S1A5B1082534.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013), local legislation, and institutional guidelines. Ethical approval for the research was granted by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Korea National Sport University (IRB No. 1263-202106-HR-072-01; Approval Date: June 17, 2021) and Hanshin University (IRB No. 2023-02-006; Approval Date: November 13, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study is grounded in the doctoral dissertation of Dr. Woori Han (2021), in which the foundational structure of the Acceptance and Commitment Performance Training for Elite Shooters (ACPT-S) was first conceptualized. The present research further advances the model through empirical validation and theoretical refinement, led by Dr. Suyoung Hwang, by integrating additional components and extending its application to elite-level athletes. The authors sincerely thank Dr. Eun-Surk Yi for his invaluable administrative leadership and financial support. His contribution was instrumental in facilitating the successful implementation of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACT |

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| ACPT-S |

Acceptance and Commitment Performance Training for Elite Shooters |

| PST |

Psychological Skills Training |

References

- Adler, R. H. (2022). Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Human Lactation, 38(4), 598–602. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, M. E. (2013). The strength of self-acceptance: Theory, practice and research. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802–1811. [CrossRef]

- Boutcher, S. H., & Rotella, R. J. (1987). A psychological skills educational program for closed-skill performance enhancement. The Sport Psychologist, 1(2), 127–137. [CrossRef]

- Breitmayer, B. J., Ayres, L., & Knafl, K. A. (1993). Triangulation in qualitative research: Evaluation of completeness and confirmation purposes. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 25(3), 237–243. [CrossRef]

- Donkoh, S., & Mensah, J. (2023). Application of triangulation in qualitative research. Journal of Applied Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 10(1), 6–9. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2004). A mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based approach to athletic performance enhancement: Theoretical considerations. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 707–723. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2007). The psychology of enhancing human performance: The mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) approach. Springer Publishing.

- Han, W. (2022). The effects of ACT-based psychological skills training for shooters: Relationships between ACT process variables and psychological factors [Doctoral dissertation, Korea National Sport University]. Korea National Sport University.

- Hayes, S. C. (2011). Acceptance and commitment in psychotherapy. Institute for the Advancement of Human Behavior.

- Hayes, S. C. (2019). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Towards a unified model of behavior change. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 226–227. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S. C., & Sackett, C. (2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy. In The encyclopedia of clinical psychology. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S., & Chang, D. (2022). Development of elite shooter’s marksmanship perfectionistic strivings scale. Korean Journal of Sport Science, 31(5), 323–344.

- Hwang, S., & Yi, E. (2025). HOPE-FIT in action: A hybrid effectiveness–implementation protocol for thriving wellness in aging communities. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(7), 1123. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S., Kim, H., & Yi, E. (2025). Healthy movement leads to emotional connection: Development of the Movement Poomasi “Wello!” application based on digital psychosocial touch—A mixed-methods study. Healthcare, 13(4), 987. [CrossRef]

- Ihalainen, S., Kuitunen, S., Mononen, K., Linnamo, V., & Häkkinen, K. (2016). Determinants of competitive rifle shooting performance. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 26(3), 266–274. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. I., Hudson, M., & Ryan, C. G. (2023). Perspectives on the insidious nature of pain metaphor: We literally need to change our metaphors. Frontiers in Pain Research, 4, 1224139. [CrossRef]

- Josefsson, T., Gustafsson, H., Robinson, P., Cedenblad, M., Sievert, E., & Ivarsson, A. (2024). Examining the effects of the mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) programme on sport-specific dispositional mindfulness, sport anxiety, and experiential acceptance in martial arts. Scandinavian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 19–26. [CrossRef]

- Josefsson, T., Ivarsson, A., Gustafsson, H., Stenling, A., Lindwall, M., Tornberg, R., & Lundqvist, C. (2019). Effects of mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) on sport-specific dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation, and self-rated athletic performance in a multiple-sport population: An RCT study. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1518–1529. [CrossRef]

- Josefsson, T., Tornberg, R., Gustafsson, H., & Ivarsson, A. (2020). Practitioners’ reflections of working with the mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) approach in team sport settings. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 11(2), 92–102. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. C. (2016). Effects of mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) and psychological skills training (PST) for shooters [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Korea National Sport University.

- Krafft, J., Levin, M. E., Potts, S., & Schoendorff, B. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of multiple versions of an acceptance and commitment therapy Matrix app for well-being. Behavior Modification, 43(2), 246–272. [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28(4), 563–575. [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y. (1980). Guba. E.(1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage. LincolnNaturalistic Inquiry1985.

- Lu, Q., Li, P., Wu, Q., Liu, X., & Wu, Y. (2021). Efficiency and enhancement in attention networks of elite shooting and archery athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 527–536. [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, G., Roca, A., & Ford, P. R. (2023). Metacognition and attentional control in high-performance sport: Implications for training and performance. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 21(4), 389–405. [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, S., & Roche, B. T. (2023). ACT: A process-based therapy in search of a process. Behavior Therapy, 54(6), 939–955. [CrossRef]

- Morris, T., & Thomas, P. (1995). Approaches to applied sport psychology. In T. Morris & J. Summers (Eds.), Sport psychology: Theory, applications and issues (pp. 215–258). Wiley.

- Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 250–260. [CrossRef]

- Noetel, M., Ciarrochi, J., Van Zanden, B., & Lonsdale, C. (2019). Mindfulness and acceptance approaches to sporting performance enhancement: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(1), 139–175. [CrossRef]

- Pears, M., & Sutton, J. (2021). Acceptance and commitment training for stress management in collegiate athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 33(5), 482–498. [CrossRef]

- Poulus, D., McCarthy, P., & Jones, G. (2024). Emotional-technical integration and elite sport performance: A conceptual model. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 13(2), 145–158. [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, H., Lundgren, T., Kenttä, G., Ihalainen, J. K., Kalaja, S., Valtonen, M., & Lappalainen, R. (2025). A sport-specific ACT group intervention for promoting athletes’ mental well-being: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 37(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, N. J., Ryba, T. V., & Aunola, K. (2025). Flow and acceptance in endurance sport: A mixed-methods exploration. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 68, 102308. [CrossRef]

- Sabzevari, F., Samadi, H., Ayatizadeh, F., & Machado, S. (2023). Effectiveness of mindfulness-acceptance-commitment based approach for rumination, cognitive flexibility and sports performance of elite players of beach soccer: A randomized controlled trial with 2-months follow-up. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 19(1), e174501792303282. [CrossRef]

- Son, J. R. (2020). Metaphors and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [In Korean]. Hakjisa.

- Stafford-Brown, J., & Pakenham, K. I. (2012). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for athlete burnout: A case study. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 6(3), 189–207. [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J. A., & Afari, N. (2014). The big book of ACT metaphors: A practitioner’s guide to experiential exercises and metaphors in acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

- Su, N., Si, G., Liang, W., Bu, D., & Jiang, X. (2024). Mindfulness and acceptance-based training for elite adolescent athletes: A mixed-method exploratory study. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1401763. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. (2017). Assessment in applied sport psychology. Human Kinetics.

- Terry, M. L., & Leary, M. R. (2011). Self-compassion, self-regulation, and health. Self and Identity, 10(3), 352–364. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).