1. Introduction

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have been widely used in biomedical research due to their unique morphological features and ease of functionalization. These properties enable the loading of therapeutic agents, including small molecules, peptides, proteins, and genes, through electrostatic interactions or chemical bonding. The synthesis conditions of mesoporous silica materials can be precisely controlled to optimize their performance while minimizing toxicity. Materials in the SBA series feature a silica-based framework with a highly ordered mesoporous structure, adjustable pore sizes, high specific surface area, and excellent thermal stability. Among the various SBA materials, only SBA-15 and SBA-16 are commonly used in biomedical applications. Notably, SBA-15 is the most frequently selected carrier for large biomolecules due to its large surface area and pore diameter. Incorporating proteins into mesoporous silica enhances their stability, reduces susceptibility to degradation, and improves their therapeutic efficacy in experimental disease models (Xu et al. 2023).

Crotoxin (CTX), a protein extracted from the venom of the South American rattlesnake Crotalus durissus terrificus, has been studied for its analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and muscle-paralyzing activities. The venom exhibits neurotoxic, myotoxic, and coagulant effects (Oliveira et al. 2003), with these toxic actions being primarily attributed to crotoxin, the main component of the venom, which limits its direct medicinal use. Crotoxin has a molecular weight of approximately 24 kDa (Hanashiro, Da Silva, and Bier 1978; Rangel-Santos et al. 2004) and is composed of two subunits: a larger, basic subunit rich in lysine and arginine residues, known as crotapotin (CA), and a smaller, strongly acidic subunit with phospholipase A₂ activity, known as CB (Faure and Bon 1988). Previous studies have shown that the toxicity of crotoxin can be reduced and its therapeutic effects enhanced when it is encapsulated in nanostructured SBA-15 silica. Oral administration of the complex reduced neuropathic pain, a chronic condition experimentally induced in mice by sciatic nerve injury. A decrease in the activation of central nervous system cells, such as astrocytes and microglia involved in inflammatory responses, was also observed (Faure and Bon 1988; Sant’Anna et al. 2020).

Some authors have investigated the effect of free crotoxin on intestinal inflammation and observed that intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of crotoxin led to a significant reduction in the classical symptoms of ulcerative colitis induced by 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) in mice (Almeida et al. 2015). Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, relapsing form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by inflammation of the mucosal lining of the large intestine, primarily affecting the distal colon and rectum. Both genetic and environmental factors play crucial roles in the development of UC. Among environmental influences, industrialization and the westernization of lifestyles characterized by increased consumption of processed and high-fat foods, reduced intake of dietary fiber, greater use of antibiotics and medications, more sedentary lifestyles, and higher hygiene standards (which may impact immune system development) are particularly significant (Faure and Bon 1988; Abebe et al. 2025). These factors can influence the gut microbiota and disrupt the epithelial barrier, leading to abnormal mucosal immune responses and inflammation that contribute to the development of UC. These responses are characterized by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, activation of inflammatory cells, and impaired immunoregulation. As a result, the mucosa becomes damaged, causing symptoms such as diarrhea, rectal bleeding, weight loss, abdominal pain, and other less severe manifestations(Shouval and Rufo 2017; Legaki and Gazouli 2016; Molodecky et al. 2012).

Different experimental protocols can reproduce the pathophysiology of UC, with chemical induction using dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) dissolved in drinking water being one of the most commonly used methods (Jurjus, Khoury, and Reimund 2004). DSS was initially used in hamsters in 1985 (Ohkusa 1985) and later in mice in 1990 by Ohkusa's group (Okayasu et al. 1990), successfully reproducing a model similar to human UC. The symptoms are caused by the direct action of DSS on the epithelial cell barrier, leading to the translocation of gut microbiota from the intestinal lumen into the mucus layers. This triggers inflammatory responses characterized by cellular infiltration, mucin depletion, cryptitis, and the formation of crypt abscesses. (Strober, Fuss, and Blumberg 2002; Perše and Cerar 2012). Due to its chronic nature, associated risks, and limited therapeutic options, ulcerative colitis (UC) significantly impacts patients' quality of life. Ulcerative colitis is significantly more common in Western countries (Europe, North America, and Oceania), with incidence rates frequently exceeding 10 cases per 100,000 people per year. In developing countries, the rates are lower, ranging from approximately 0.5 to 6 cases per 100,000 people per year. The estimated global number of individuals living with ulcerative colitis is approximately 6 million, according to recent systematic reviews and data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study (2017–2023) (Ng et al., 2017; Le Berre, Honap, and Peyrin-Biroulet, 2023). These indices highlight the growing importance of studying the disease(Quaresma et al. 2022; Ye et al. 2015). Available therapies include palliative treatments, such as anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressants, and biological agents that target specific components of the immune response. In more severe cases, disease progression may necessitate partial or total surgical removal of the colon (Iskandar, Dhere, and Farraye 2015; Talley et al. 2011; Asakura et al. 2009). Considering the characteristics of crotoxin and the potentiation of its effects when incorporated into SBA-15 mesoporous silica nanoparticles (CTX-SBA-15), this study presents, for the first time, a detailed biophysical characterization of crotoxin's structure within a silica matrix. We then analyzed the effect of oral administration of the CTX-SBA-15 complex on the progression of DSS-induced ulcerative colitis using a susceptible mouse model.

The synthesis conditions were precisely controlled, ensuring that crotoxin in the complex remained stable. CTX-SBA-15 complex exhibited a protective effect on the progression of ulcerative colitis.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Crotoxin Incorporated into SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles

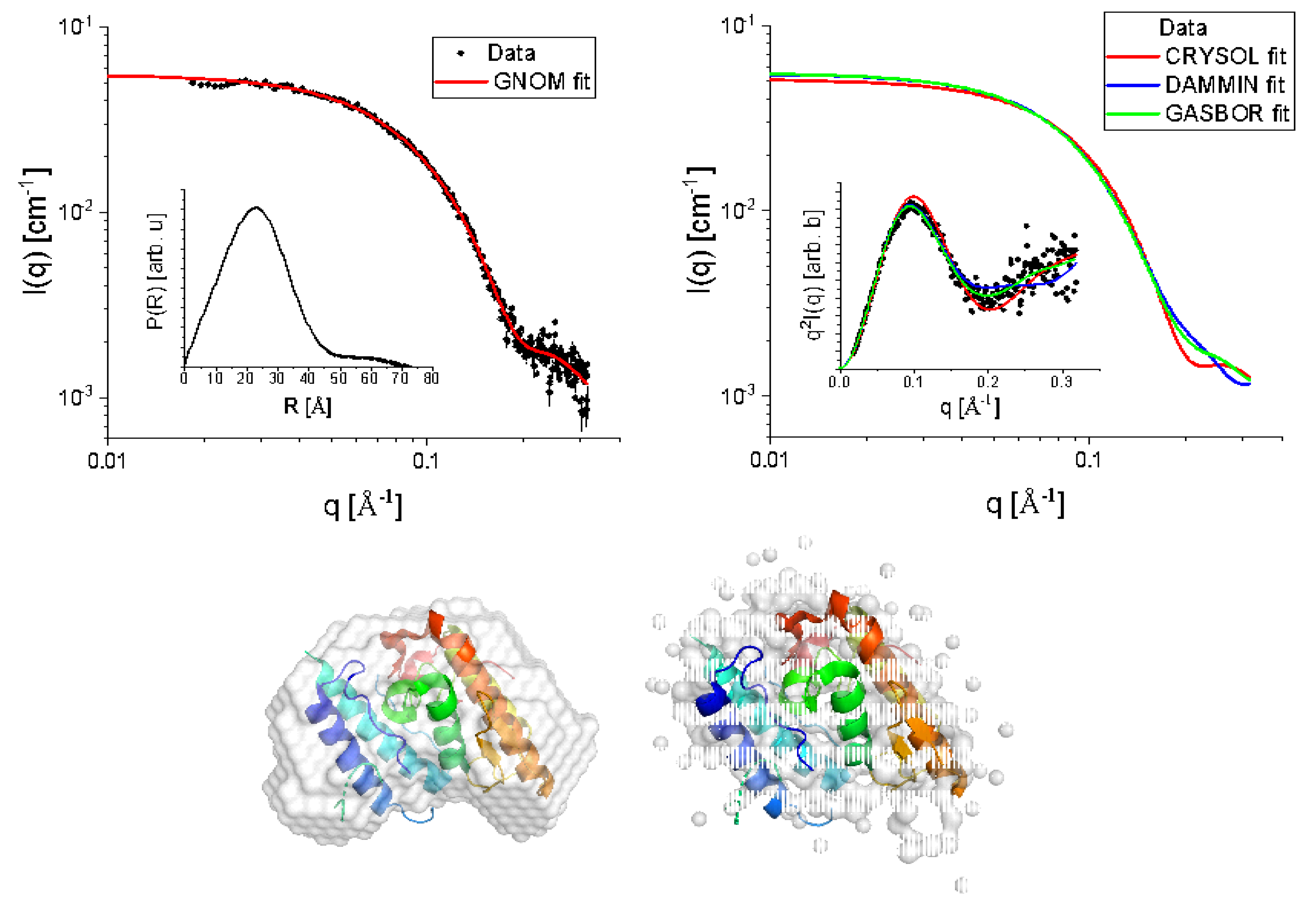

Figure 1-A shows the SAXS experimental data (black-filled circles) of CTX in a PBS buffer. We first proceeded with the Indirect Fourier Transform to extract structural information from the curve, which brings information in the real space in a free modeling approach through the so-called pair distance distribution function, P(R) (Glatter, 1977) (36). The software GNOM was used for this purpose (Svergun, 1992). From the satisfactory IFT fitting (red continuous line in

Figure 1-A), P(R) was obtained (inset of

Figure 1-A), which suggests the existence of particles with globular shape, possibly with flexible parts, having a maximum length (where P(R) ~ 0) of approximately 70

. The hypothesis about the flexibility along the globular shape is corroborated when the data is visualized in a Kratky plot, i.e., I(q)xq

2 versus q (inset of

Figure 1-B). Additionally, the maximum length of the particles is smaller than the mean mesopore size of the SBA-15, which reinforces the presence of CTX inside the mesopores.

From IFT method, it is also possible to evaluate the protein radius of gyration, RG = (17.93 ± 0.06)

, which is slightly smaller compared to the one reported in the literature (Fernandes et al. 2017a), and the forward scattering, I(0) = (0.053 ± 0.002) cm

-1, related to the protein molecular weight, M

W (in kDa), by (Pinto Oliveira 2011a):

where N

A,

c, and

Δρm are Avogadro’s number, the concentration of the protein (in mg mL

-1), and the excess scattering length density per unit mass (in cm g

-1), respectively. A good approximation of

Δρm for proteins is 2×10

10 cm g

-1 (Pinto Oliveira 2011b). Using

c = 3.44 mg mL

-1, obtained from UV-Vis spectroscopy measurements, we obtained MW ≈ 23.2 kDa, close to the theoretical value calculated from the PDBID 3R0L, indicating a quite monodisperse sample.

Considering the high-resolution model 3R0L for CTX, one can compare the theoretically expected intensity with the obtained SAXS experimental data, for instance, using the CRYSOL program (Svergun, Barberato, and Koch, 1995). Proceeding in this way, we obtained a satisfactory fitting (

Figure 1-B, red continuous line), suggesting that the tertiary structure of CTX (overall shape and size) observed in its crystal form is also kept in solution, as well as the secondary structure, already observed in CD results (

Figure 3-A). This fact is corroborated by the good agreement between the high-resolution model of CTX and the

ab initio bead model obtained from DAMMIN (D. I. Svergun 1999) and GASBOR (D. I. Svergun, Petoukhov, and Koch 2001) programs, the former one using the amount of CTX residues as a constraint. SUPALM program (Konarev, Petoukhov, and Svergun 2016) was used to superimpose one 3D structure onto another, and the visual comparisons are shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

– SAXS data (black filled circles) fitted with the IFT method using GNOM software (red continuous line). Inset: P(R) function obtained from the IFT fit (A). SAXS data were modeled using CRYSOL (using PDBID 3R0L), DAMMIN, and GASBOR (red, blue, and green continuous lines, respectively). Inset: Kratky plot of experimental data and fittings (B). Comparison between the bead models obtained from DAMMIN and GASBOR with the PDBID 3R0L (C).

Figure 1.

– SAXS data (black filled circles) fitted with the IFT method using GNOM software (red continuous line). Inset: P(R) function obtained from the IFT fit (A). SAXS data were modeled using CRYSOL (using PDBID 3R0L), DAMMIN, and GASBOR (red, blue, and green continuous lines, respectively). Inset: Kratky plot of experimental data and fittings (B). Comparison between the bead models obtained from DAMMIN and GASBOR with the PDBID 3R0L (C).

DLS was performed to check the presence of possible protein aggregates in aqueous dispersion, and the autocorrelation function, C(τ), is shown in

Figure 2 (filled circles). By using the Non-Negatively constrained Least Squares (NNLS) method (Morrison, Grabowski, and Herb 1985) to fit the curve C(τ) satisfactorily (

Figure 2, red continuous line), the histograms of hydrodynamic diameter per intensity, per volume, and per number of particles were obtained (

Figure 2, inset). Despite the presence of larger particles with a diameter of (91 ± 28) nm, they are significantly less numerous, as indicated by the histograms of diameter per volume and per number. Thus, most of the particles have a diameter of (4.3 ± 0.2) nm, corroborating that samples are quite monodisperse, in complete agreement with SAXS analyses.

Notably, the obtained autocorrelation function is slightly different from the curve shown in Fernandes study in 2017 (Fernandes et al. 2017b, 2017a). This could be because the authors did not use filtration before the measurements. Therefore, larger aggregates could meaningfully alter the measured data, as is known in any DLS experiment, even if these particles are not as numerous as the smaller ones. To check if DLS data is also consistent with the high-resolution model 3R0L of CTX, we used the HYDROPO software (Ortega, Amorós, and García de la Torre 2011), which allows the calculation of several hydrodynamic properties of rigid macromolecules, such as globular proteins, from their atomic-level structure. Using this, the predicted hydrodynamic diameter of CTX at the experimental conditions used in this investigation is ~4.6 nm, in agreement with the value obtained by DLS analysis. Furthermore, the estimated radius of gyration and the longest CTX length are, respectively, ~17 and ~63 , also in agreement with the SAXS results.

Figure 2.

– Autocorrelation function (filled circles) fitted by the NNLS method (continuous line). Inset: Hydrodynamic diameter distributions of the peptide weighted by number, volume, and intensity.

Figure 2.

– Autocorrelation function (filled circles) fitted by the NNLS method (continuous line). Inset: Hydrodynamic diameter distributions of the peptide weighted by number, volume, and intensity.

The CD spectra of crotoxin in PBS solution (

Figure 3A) show two minima in the 222 and 208 nm regions, and a positive maximum at 192 nm, which are characteristic of the alpha helix content of this protein (Wallace, 2009).

Estimations of the secondary structure content based on this CD spectrum yielded values of ~49% α-helix, 8% β-strands, and 43% others, which are in close agreement with the protein crystal structure deposited on PDBID 3R0L (45% helix, 3% β-sheet, and 52% others). The deconvolution of the CD spectra of crotoxin was performed using the Dichroweb server with the SP175t (Lees et al. 2006) database and the ContinLL software. The increase in temperature was seen to cause severe conformational changes in the crotoxin structure (

Figure 3B). Crotoxin remained thermally stable within the 10-40

oC interval, preserving its native CD spectrum profile unchanged up to 50

oC. However, after crossing this point to higher temperatures (60-90 °C), significant conformational changes (such as the reduction of the 222 nm band, assumed to be due to the loss of helical content) were observed. The temperature of melting (Tm) estimated for the thermal denaturation of crotoxin in PBS was ~67 °C. After cooling back the sample to 10 °C, the native CD spectrum of crotoxin was not reassumed, suggesting the protein has assumed a more unfolded/disordered state due to its thermal denaturation assay as an irreversible process.

Figure 3.

a) Crotoxin CD spectra in PBS (black) and obtained from PDBID 3R0L (red). b) Effect of temperature on the secondary structure of crotoxin. Crotoxin CD spectra, taken from 10 °C (black) to 90 °C (red). Intermediate temperatures (20-80 °C) are grey, and the spectrum of protein cooled back to 10 °C after treatment is dashed blue. Inset: Thermal melting curve for crotoxin, presenting Tm value of ~67 °C.

Figure 3.

a) Crotoxin CD spectra in PBS (black) and obtained from PDBID 3R0L (red). b) Effect of temperature on the secondary structure of crotoxin. Crotoxin CD spectra, taken from 10 °C (black) to 90 °C (red). Intermediate temperatures (20-80 °C) are grey, and the spectrum of protein cooled back to 10 °C after treatment is dashed blue. Inset: Thermal melting curve for crotoxin, presenting Tm value of ~67 °C.

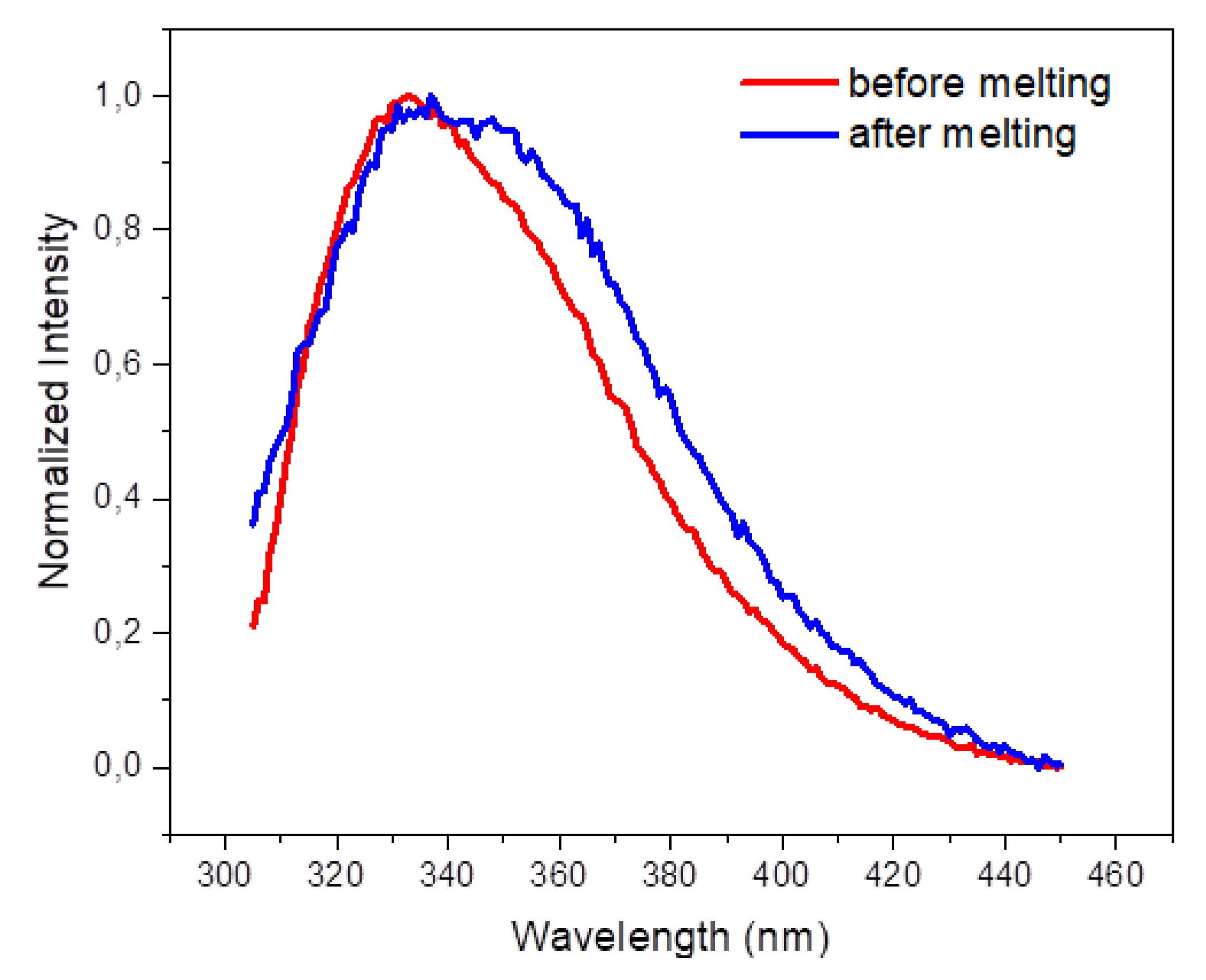

The emission spectrum of the Trp residues of crotoxin in PBS (

Figure 4) shows a maximum emission centered at 333 nm, indicating the preservation of the aromatic residues from exposure to the aqueous environment, which is typically observed in globular proteins (Jameson 2014). However, after heating the protein to 90°C, the maximum emission shifted to ~345 nm, indicating a higher exposure of aromatic residues to the aqueous solvent following thermal treatment. In agreement with that, the reduction of the polarization values of crotoxin in PBS from ~0.17 to ~0.066 was also observed after thermal melting treatment, indicating the Trp residues assume a faster rotation in solution due to their higher local mobility.

Overall, the results demonstrate the efficiency of crotoxin incorporation into mesoporous silica. The analyses indicate that this process does not alter the secondary or tertiary structures of crotoxin in solution. The preservation of aromatic residues and the observed thermostability of the complex further support the structural integrity of the encapsulated crotoxin.

2.2. Crotoxin Incorporated into SBA-15 Mesoporous silica Nanoparticles (CTX-SBA-15) Modulates DSS-Induced Colitis

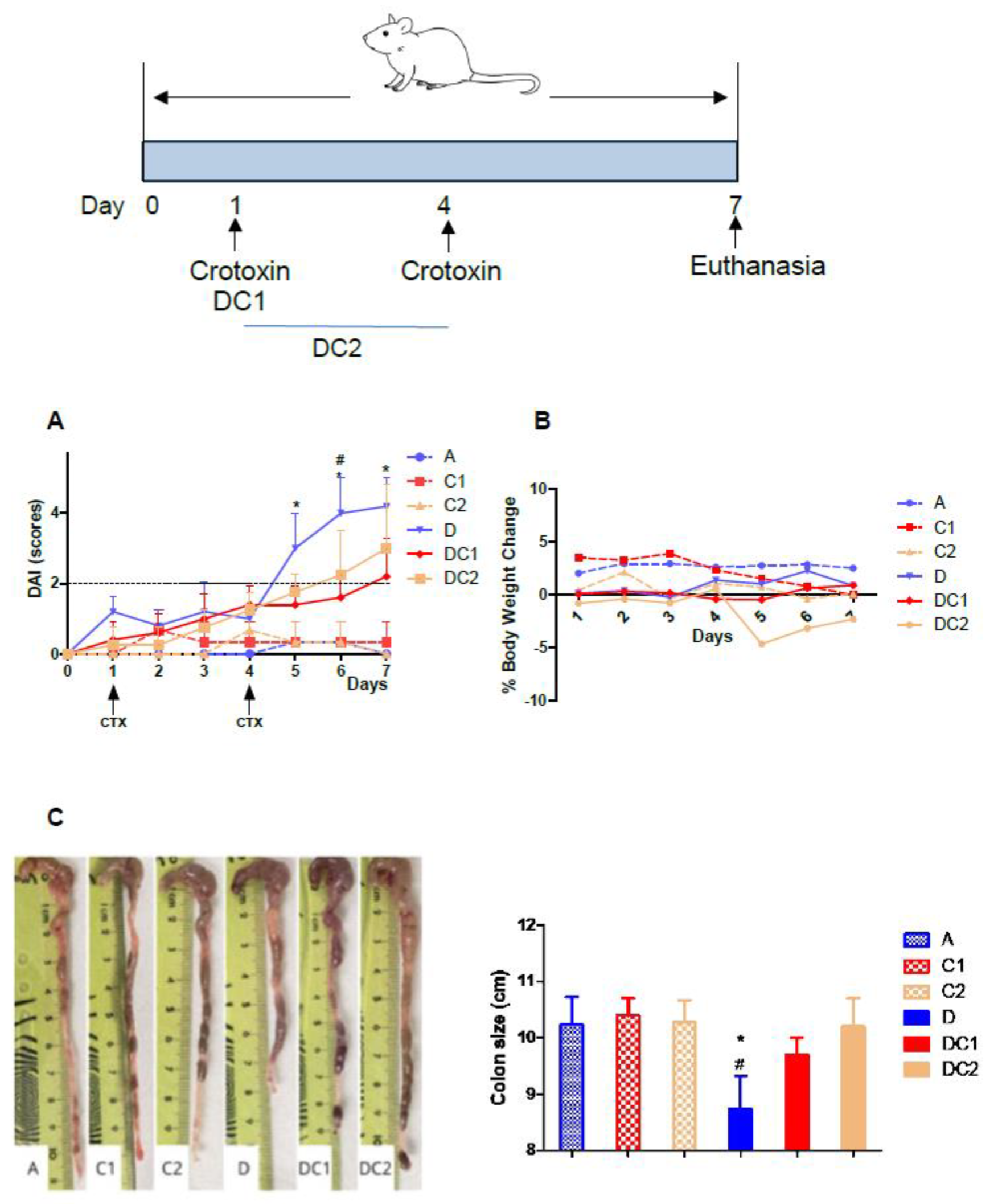

We used crotoxin, incorporated into SBA-15 (CTX-SBA-15), as an anti-inflammatory agent to modulate intestinal inflammation induced by DSS. Behavioral observations confirmed that there was no toxicity or morbidity associated with the orally administered CTX-SBA-15 complex at various concentrations, ranging from 37.5 to 600 μg/kg body weight (data not shown). We divided the AIRmax mice into six groups, as outlined in the Materials and Methods section.

Figure 5 shows that mice treated with CTX-SBA-15 alone or with water exhibited low DAI scores, while groups that received DSS, with or without CTX-SBA-15, showed elevated scores. However, the administration of CTX-SBA-15, whether as a single or double dose, led to a significant reduction in DAI. This reduction was particularly noticeable starting on the fifth day following the initiation of DSS treatment, coinciding with the peak scores in the DSS-only group. In the group that received two gavage doses of CTX-SBA-15, a noticeable decrease in DAI was observed starting on day 6. It is worth noting that crotoxin administered at 125 µg/kg without SBA-15 does not produce any UC modulatory effect (data not shown).

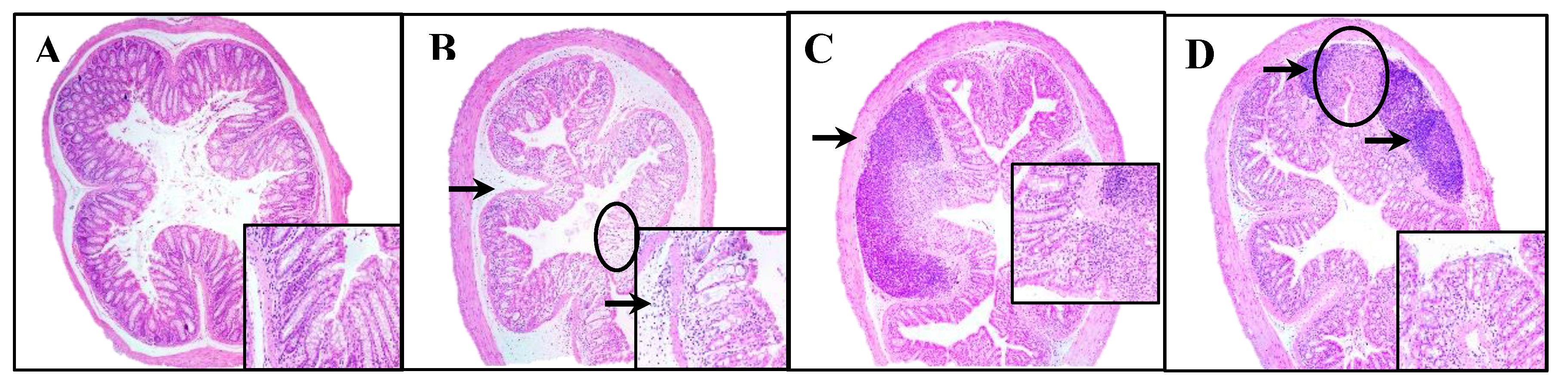

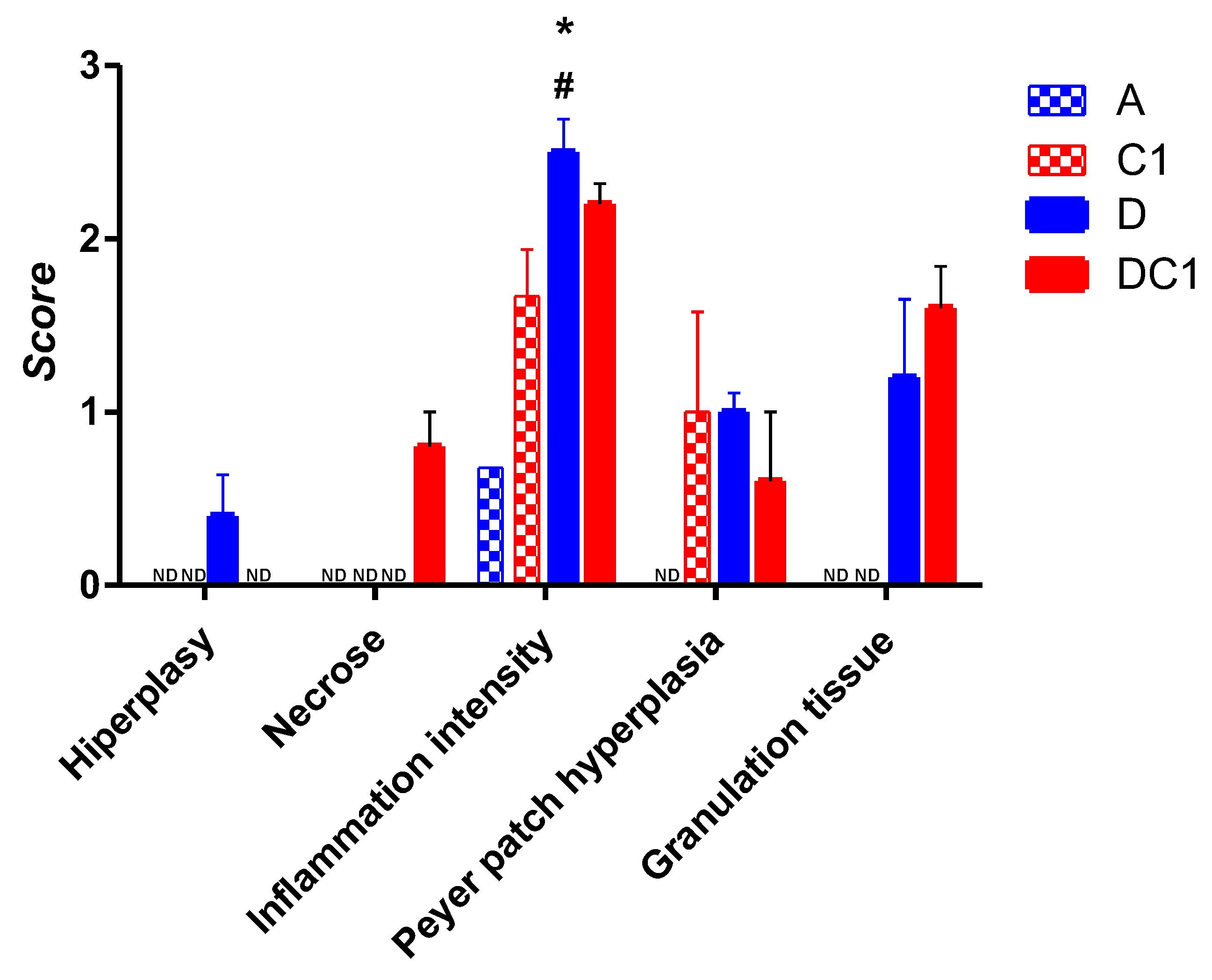

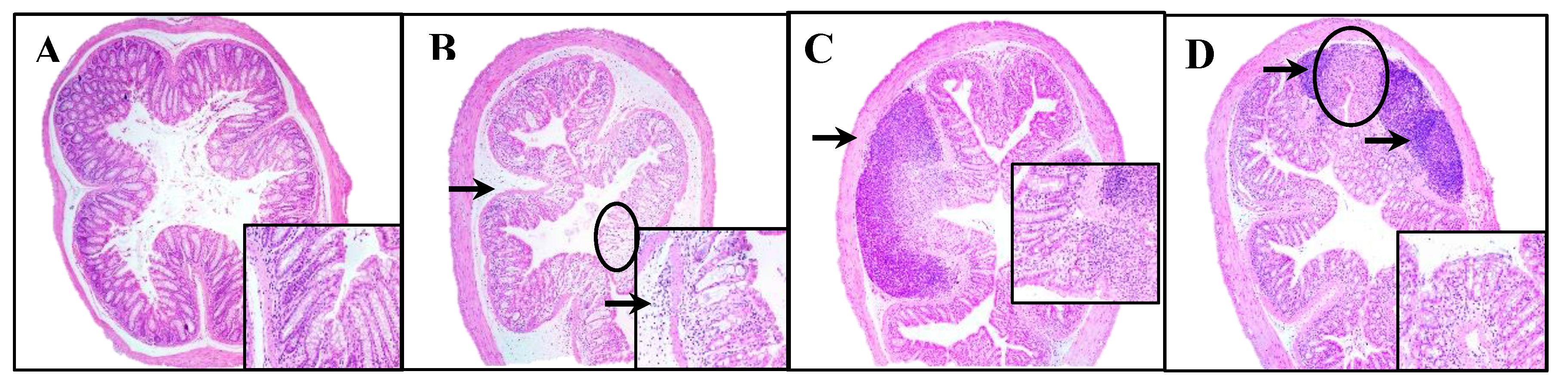

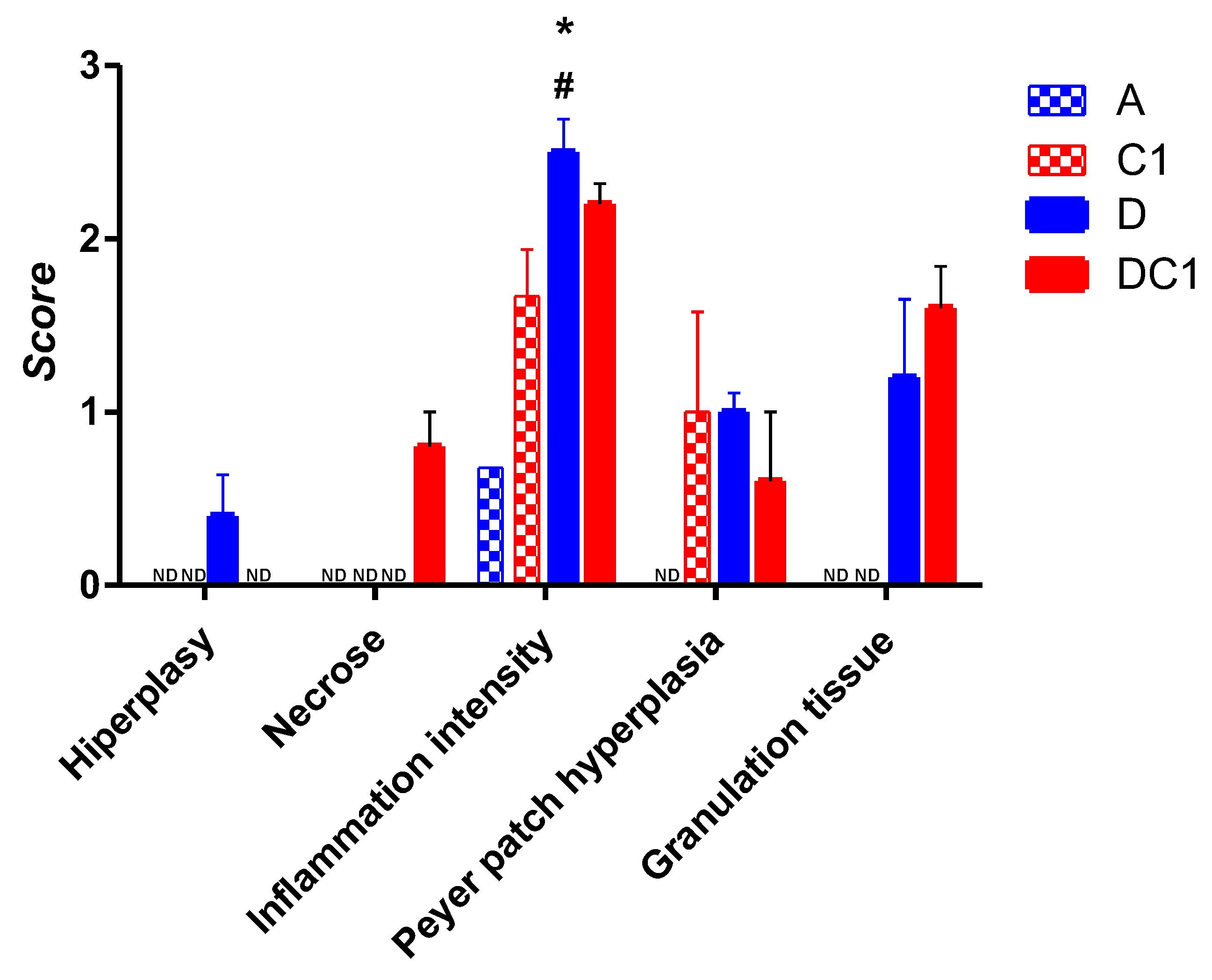

Treatment with DSS resulted in a reduction in colon length, a key indicator of disease progression in experimental colitis. This effect was completely reversed in animals treated with DSS and one or two doses of CTX-SBA-15. Histological analysis revealed that the control groups, which received only water or CTX-SBA-15 (one or two doses), preserved normal colonic epithelial architecture, characterized by visible villi and distinct cell types within the crypts. In contrast, the DSS-treated group displayed epithelial disruption and a marked inflammatory response in the submucosal layer, characterized by neutrophilic infiltration. In the group treated with DSS and CTX-SBA-15, a small but significant reduction in the severity of inflammation was observed compared to the group that received DSS alone.

Figure 6.

Histopathological analysis. Representative photomicrographs (Magnification of 40x and inset 200x) from AIRmax mice. A-typical colonic tissue with access to pure water, B- DSS 2.5% ad libitum indicating submucosa edema associated with inflammatory infiltrate (arrow) and area of glandular cells loss (circle), C- and D- DSS 2.5% and SBA-15- crotoxin 125 µg/Kg bw at the first day (C) or at first and fourth days (D) indicating Peyer’s patch hyperplasia (arrows) and fibroplasia with mild inflammatory infiltrate (circle in D), lower loss of glandular cells compared to the DSS group. Notably, there is no edema, with preservation of the epithelium and villous architecture. E- Histopathological characteristics are measured by scores of hyperplasia, necrosis, inflammation intensity, and Peyer patch hyperplasia alterations. The values shown are the means ± SEM of 5 animals per group. *Difference between DSS-treated and control mice, #Difference between DSS and DC-treated mice, by ANOVA, p < 0.05. ND = not detected.

Figure 6.

Histopathological analysis. Representative photomicrographs (Magnification of 40x and inset 200x) from AIRmax mice. A-typical colonic tissue with access to pure water, B- DSS 2.5% ad libitum indicating submucosa edema associated with inflammatory infiltrate (arrow) and area of glandular cells loss (circle), C- and D- DSS 2.5% and SBA-15- crotoxin 125 µg/Kg bw at the first day (C) or at first and fourth days (D) indicating Peyer’s patch hyperplasia (arrows) and fibroplasia with mild inflammatory infiltrate (circle in D), lower loss of glandular cells compared to the DSS group. Notably, there is no edema, with preservation of the epithelium and villous architecture. E- Histopathological characteristics are measured by scores of hyperplasia, necrosis, inflammation intensity, and Peyer patch hyperplasia alterations. The values shown are the means ± SEM of 5 animals per group. *Difference between DSS-treated and control mice, #Difference between DSS and DC-treated mice, by ANOVA, p < 0.05. ND = not detected.

3. Discussion

In this study, we focused on the promising potential of crotoxin as an orally administered modulatory agent for experimental ulcerative colitis. To ensure its stability and bioavailability, crotoxin was incorporated into nanostructured silica, a crucial step that protects the molecule during its passage through the digestive tract and enables its delivery to the colonic epithelium (Broering et al., 2024).

Nanostructured silicas are silicon oxide [SiO2] particles with a highly organized mesopore structure that, due to their physicochemical properties, have the potential for use in different areas and biological applications (Cussa et al. 2017; Sant’Anna et al. 2020). These materials can interact with atoms, ions, and molecules, not only on their external surface but also on their interior. As described, SBA-15 silica has a hexagonal structure with highly ordered and interconnected pores, relatively thick walls (up to 6nm), pore size around 10 nm, pore volume greater than 1 cm³g-1, surface area above 800 m2g-1, a large number of silanol groups, which provides high adsorption/incorporation capacity for various organic, inorganic and biological species, in addition to notable thermal, hydrothermal and mechanical stability (Fantini et al. 2021). In the present study, we employed multiple techniques such as Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS), Circular Dichroism (CD), fluorescence spectroscopy, UV-Vis spectrophotometry, and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to analyze various aspects of the nanostructured silica-crotoxin (CTX-SBA-15) complex. These included the structural organization of the material, secondary structure, and conformational changes of the protein upon incorporation into silica, alterations in protein folding, ligand binding, interactions with other molecules or aggregation, and the quantification of crotoxin loading into SBA-15. Collectively, these techniques provided a comprehensive understanding of the CTX-SBA-15 interaction, demonstrating that the structural, conformational, chemical, and functional properties of crotoxin were preserved within the complex.

Toxins derived from venomous animals such as snakes, scorpions, and spiders have contributed significantly to human health, for example, the development of the antihypertensive drug Captopril®, which originated from studies on Bothrops jararaca venom (Zambelli et al. 2016; Cushman and Ondetti 1991; Pontieri, Lopes, and Ferreira 1990). Crotoxin, a component of the venom of snakes from the genus Crotalus, exhibits antinociceptive and immunomodulatory effects in vivo, making it a promising candidate for pharmacological intervention in inflammatory diseases (Almeida et al. 2015; Rangel-Santos et al. 2004; Cardoso et al. 2001). However, the therapeutic application of such toxins is often limited by their inherent toxicity. To mitigate these effects and enhance oral bioavailability, we encapsulated crotoxin in mesoporous SBA-15 silica (Philippart, Schmidt, and Bittner 2016).

As an experimental model, we utilized a line of mice with high inflammatory capacity, derived from heterogeneous populations through selective breeding, to induce a high acute inflammatory response with polyacrylamide particles (Ibanez et al., 1992). These mice develop significant DSS-induced intestinal inflammation that closely mimics human ulcerative colitis (Di Pace et al. 2006).

In our in vivo experiments, we administered different doses of CTX-SBA-15 to assess its potential toxicity when delivered orally. Based on behavioral observations, no detectable toxic effects or mortality were observed at the tested doses, supporting the safety of its use in mice. One hypothesis is that SBA-15 reduces the toxic effects of crotoxin when encapsulated (Sant’Anna et al. 2019), which is consistent with our findings. SBA-15 likely functions as both a carrier and a protective matrix, shielding crotoxin throughout the gastrointestinal tract and facilitating its delivery to the therapeutic target (Sant’Anna et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2010).

We used therapeutic concentrations of crotoxin similar to those determined in the studies by Sant’Anna (Sant’Anna et al. 2019, 2020). Previous research by Almeida et al., demonstrated that free crotoxin, when administered intraperitoneally, can modulate acute intestinal inflammation induced by rectal administration of TNBS in mice (Almeida et al. 2015). The results of our current experiments are consistent with these findings, particularly in the group treated with DSS and a single oral dose of CTX-SBA-15. In this group, we observed a reduction in the DAI, primarily due to improved clinical signs, as well as the absence of colon shortening, a decrease in inflammatory infiltrate, and preservation of the colonic epithelium, compared to the control DSS-treated group.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Crotoxin Purification

Crotoxin was purified from Crotalus durissus terrificus venom using the method described by Bon et al. (1989). Briefly, aliquots of venom diluted in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7) were subjected to anion exchange chromatography on a MONO-Q HR 5/5 column in an Akta-FPLC system (GE Healthcare, Brazil). The proteins adsorbed to the resin were eluted in a linear gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl and buffered with 50 mM phosphate. The fractions corresponding to CTX were pooled and dialyzed against PBS, and the protein concentration was determined by the BCA method.

4.2. Preparation of the Complex Crotoxin and SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica (CTX-SBA-15)

The crotoxin (125 μg/Kg) was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4, slowly added to the silica SBA-15 at a 1:10 ratio (CTX:SBA-15), and held for 24 h at 2°C to 8°C with occasional stirring.

4.3. CTX-SBA-15 Characterization

The crotoxin used in this study was characterized by Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS), Circular Dichroism (CD), fluorescence spectroscopy, UV-Vis spectrophotometry, and Dynamical Light Scattering (DLS).

SAXS experiment was performed on a Nanostar (Bruker) instrument equipped with a microfocus Genix 3D system (Xenocs) and a Pilatus 300k (Dectris) detector. The sample-to-detector distance was ~667 mm, which provided an effective range of the modulus of the transfer moment vector, q = 4πsin(θ)/λ (where 2θ is the scattering angle and λ = 1.5418 Å is the X-ray wavelength), from 0.018 to 0.30 Å-1. We measured the CTX sample (at 5 mg/mL) and PBS buffer in the same reusable quartz capillary with a 1.5 mm diameter mounted on stainless steel cases. Data statistics were satisfactory at this concentration, and no interparticle interaction was observed. Data treatment, which includes azimuthal integration, background subtraction, and absolute scale normalization, was performed using the SUPERSAXS software suite (Oliveira CLP).

DLS measurement was performed on a Brookhaven DM-5000 particle-size analyzer at room temperature using a wavelength of 635 nm. Data analysis was conducted using the BIC software provided with the machine. Before the measurements, the CTX sample was filtered using a 0.45 µm filter. Then, with the help of UV-Vis spectroscopy, the concentration was adjusted to 1 mg/mL (by adding PBS buffer) to mitigate the influence of any interparticle interaction on the diffusion coefficient of the particles and, consequently, on the obtained data.

The UV-Vis spectrophotometry was performed in NanoDrop 2000 Thermo-Fischer equipment, using 0.5 mg/mL of CTX in PBS.

The CD spectra of crotoxin (0.1 mg/mL) in PBS were collected on a J-815 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Japan) from 280 nm to 190 nm in 1 nm intervals, using a scan speed of 50 nm/min and a 1.0 mm pathlength quartz Suprasil (Hellma) cuvette at 25 °C. Thermal stability studies of crotoxin in PBS were performed over the temperature range of 10 to 90 °C in 10 °C increments, allowing 5 minutes of equilibration time at each temperature before measurement. Six repeat measurements were made at each temperature. CDToolX (Miles and Wallace 2018) software was used for data processing, which consisted of the average of the six scans of the sample, subtraction of the corresponding buffer baseline, smoothing with a Savitzky–Golay filter, and zeroing at the 263-270 region. Data was converted to delta epsilon (Δε) units using a mean residue weight of 112.9. The secondary structural contents were analyzed using the Dichroweb server (Whitmore and Wallace, 2004), with a database of SP175t (Lees et al., 2006).

The emission spectra of the tryptophan (Trp) fluorescence spectroscopy residues in crotoxin (0.075 mg/ml) in PBS were collected on an ISS K2 spectrofluorometer (Illinois, USA) with excitation performed at 295 nm, using 8 nm slits for both excitation and emission, in a 1 cm pathlength quartz cuvette Hellma, at 25 ºC. Emission spectra were recorded over the wavelength range from 305 to 450 nm. The fluorescence polarization of crotoxin in PBS was measured with excitation at 280 and emission monitored at 340 nm. Fluorescence polarization (P) was determined as a function of the parallel (

) and the perpendicular (

I) fluorescence intensities, according to the equation (Jameson 2014):

4.4. Mice

We used 3-month-old male mice from the AIRmax mouse line (Ibanez et al., 1992), maintained in the animal facilities of the Immunogenetics Laboratory at the Butantan Institute (São Paulo, Brazil). The animals were housed individually in cages with wood shavings and kept on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committee of the Butantan Institute (#6966270422).

4.5. Ulcerative Colitis Induction and CTX-SBA-15 Treatment

We organized the AIRmax mice into experimental groups with five mice per group:

A – Negative control: water and food ad libitum;

D – Positive control: 2.5% DSS (MP Biomedicals, LLC, France) in distilled drinking water for seven consecutive days and food ad libitum;

C1 – CTX-SBA-15 control (single dose): a single oral dose (gavage) of CTX-SBA-15 at 125 μg/kg bw in 300µl volume with water and food ad libitum;

C2 – CTX-SBA-15 control (two doses): two oral doses (gavage) of CTX-SBA-15 at 125 μg/kg bw, administered four days apart, with water and food ad libitum;

DC1 – DSS + CTX-SBA-15 (single dose): a single oral dose of CTX-SBA-15 at 125 μg/kg bw 30 minutes before 2.5% DSS in drinking water for 7 days and food ad libitum;

DC2 – DSS + CTX-SBA-15 (two doses): two oral doses of CTX-SBA-15 at 125 μg/kg bw30 minutes before and 4 days after 2.5% DSS in drinking water for 7 days and food ad libitum.

The animals were monitored for seven days using the Disease Activity Index (DAI).

At the end of the seven-day period, mice were euthanized by an overdose of ketamine (300 mg/Kg) and xylazine (30 mg/Kg) for colon collection and subsequent analysis. This experiment was independently repeated three times.

4.6. Disease Activity Index (DAI)

The Disease Activity Index (DAI) was evaluated based on changes in body weight, stool consistency, and the presence of blood in the feces or at the anus, as described in

Table 1 (Wirtz et al., 2007; De Fazio et al., 2014). Body weight was recorded before treatment initiation and daily for seven consecutive days following DSS administration. The index of diarrhea and rectal bleeding was also recorded daily. DAI scores were calculated by summing the individual scores for weight loss, stool consistency, and presence of blood and rectal bleeding, as outlined in

Table 1. On day seven, animals were euthanized, and colon segments were collected. The colons were washed with saline and measured for length. The distal portion of each colon was then divided into three 1-cm segments for histological analysis.

4.7. Histological Analysis

Distal colon segments were removed and fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, then stored in 70% ethanol until further processing for histology. The samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 µm for Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, according to the standard protocol. For histopathological analysis, abnormal tissues were evaluated using the scoring system described by Erben et al. (2014), which assesses the extent and severity of inflammatory cell infiltrates, epithelial alterations, and mucosal architectural changes (Erben et al., 2014).

4.8. Statistical Analysis

We used a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to statistically determine significant differences between the mean values of the groups; p < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using GraphPadPrism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA.

5. Conclusions

Several advanced analytical techniques were used to assess the structure, stability, and physical properties of crotoxin, and to verify that crotoxin was successfully incorporated into the mesoporous silica (SBA-15) structure. This configuration enables the time-controlled release of crotoxin, thereby reducing its toxicity while enhancing therapeutic efficacy. SBA-15- crotoxin demonstrated a significant modulatory effect on DSS-induced experimental ulcerative colitis, evidenced by improvements in the Disease Activity Index (DAI), macroscopic colon appearance, and histological features. Notably, treatment resulted in the preservation of the colonic epithelium and a reduction in inflammatory infiltrates. These initial findings suggest that SBA-15 serves as a protective and efficient delivery system, increasing crotoxin's local bioavailability in the colon and effectively attenuating acute intestinal inflammation. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms and therapeutic role of the SBA-15–crotoxin complex in the prevention and/or treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.N.A.N. and R.G.O.B.; methodology, W.H.K.C., S.M., O.G.R., F.N.A.N. and R.G.O.B.; validation, O.G.R. and M.C.A,F.; formal analysis, F.N.A.N., R.G.O.B., L.F.A., N.C.C.A.F., J.M.G, P.L.O.F., J.L.S.L, N.S. and B.C.F.; investigation, O.G.R., F.N.A.N., B.C.F., and R.G.O.B; resources, O.A.S. and M.C.A,F.; data curation, O.G.R. and M.C.A,F.; writing—original draft preparation, O.G.R.; writing—review and editing, M.C.A,F., P.L.O.F. O.M.I. and J.L.S.L.; supervision, O.G.R. and M.C.A,F; project administration, F.N.A.N.; funding acquisition, O.A.S. and M.C.A,F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo), grant numbers 2017/17844-8, 2019/12301-1. M.C.A. Fantini is a researcher fellow of the CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa, Brazil). NS, OAS, OMI and OGR are research fellows of Fundação Butantan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abebe, Zegeye, Molla Mesele Wassie, Amy C. Reynolds, and Yohannes Adama Melaku. 2025. “Burden and Trends of Diet-Related Colorectal Cancer in OECD Countries: Systematic Analysis Based on Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2021 with Projections to 2050.” Nutrients 17 (8). [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Caroline de Souza, Vinicius Andrade-Oliveira, Niels Olsen Saraiva Câmara, Jacqueline F. Jacysyn, and Eliana L. Faquim-Mauro. 2015. “Crotoxin from Crotalus Durissus Terrificus Is Able to down-Modulate the Acute Intestinal Inflammation in Mice.” PloS One 10 (4): e0121427.

- Asakura, Keiko, Yuji Nishiwaki, Nagamu Inoue, Toshifumi Hibi, Mamoru Watanabe, and Toru Takebayashi. 2009. “Prevalence of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease in Japan.” Journal of Gastroenterology 44 (7): 659–65.

- Bon, C., C. Bouchier, V. Choumet, G. Faure, M. S. Jiang, M. P. Lambezat, F. Radvanyi, and B. Saliou. 1989. “Crotoxin, Half-Century of Investigations on a Phospholipase A2 Neurotoxin.” Acta Physiologica et Pharmacologica Latinoamericana: Organo de La Asociacion Latinoamericana de Ciencias Fisiologicas Y de La Asociacion Latinoamericana de Farmacologia 39 (4): 439–48.

- Broering, Milena Fronza, Pedro Leonidas Oseliero Filho, Pâmela Pacassa Borges, Luis Carlos Cides da Silva, Marcos Camargo Knirsch, Luana Filippi Xavier, Pablo Scharf, et al. 2024. “Development of Ac2-26 Mesoporous Microparticle System as a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.” International Journal of Nanomedicine 19 (April):3537–54.

- Cardoso, D. F., M. Lopes-Ferreira, E. L. Faquim-Mauro, M. S. Macedo, and S. H. Farsky. 2001. “Role of Crotoxin, a Phospholipase A2 Isolated from Crotalus Durissus Terrificus Snake Venom, on Inflammatory and Immune Reactions.” Mediators of Inflammation 10 (3): 125–33.

- Cushman, D. W., and M. A. Ondetti. 1991. “History of the Design of Captopril and Related Inhibitors of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme.” Hypertension 17 (4): 589–92.

- Cussa, Jorgelina, Juliana M. Juárez, Marcos B. Gómez Costa, and Oscar A. Anunziata. 2017. “Nanostructured SBA-15 Host Applied in Ketorolac Tromethamine Release System.” Journal of Materials Science. Materials in Medicine 28 (8): 113.

- De Fazio, Luigia, Elena Cavazza, Enzo Spisni, Antonio Strillacci, Manuela Centanni, Marco Candela, Chiara Praticò, Massimo Campieri, Chiara Ricci, and Maria Chiara Valerii. 2014. “Longitudinal Analysis of Inflammation and Microbiota Dynamics in a Model of Mild Chronic Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Mice.” World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG 20 (8): 2051–61.

- Di Pace, Roberto Francisco, Solange Massa, Orlando Garcia Ribeiro, Wafa Hanna Koury Cabrera, Marcelo De Franco, Nancy Starobinas, Michel Seman, and Olga Célia Martinez Ibañez. 2006. “Inverse Genetic Predisposition to Colon versus Lung Carcinogenesis in Mouse Lines Selected Based on Acute Inflammatory Responsiveness.” Carcinogenesis 27 (8): 1517–25.

- Erben, Ulrike, Christoph Loddenkemper, Katja Doerfel, Simone Spieckermann, Dirk Haller, Markus M. Heimesaat, Martin Zeitz, Britta Siegmund, and Anja A. Kühl. 2014. “A Guide to Histomorphological Evaluation of Intestinal Inflammation in Mouse Models.” International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology 7 (8): 4557–76.

- Fantini, M. C. A., C. L. P. Oliveira, J. L. S. Lopes, T. S. Martins, M. A. Akamatsu, A. G. Trezena, M. T-D Franco, et al. 2021. “Using Crystallography Tools to Improve Vaccine Formulations.” IUCrJ 9 (1): 11–20.

- Faure, G., and C. Bon. 1988. “Crotoxin, a Phospholipase A2 Neurotoxin from the South American Rattlesnake Crotalus Durissus Terrificus: Purification of Several Isoforms and Comparison of Their Molecular Structure and of Their Biological Activities.” Biochemistry 27 (2): 730–38.

- Fernandes, Carlos A. H., Wallance M. Pazin, Thiago R. Dreyer, Renata N. Bicev, Walter L. G. Cavalcante, Consuelo L. Fortes-Dias, Amando S. Ito, Cristiano L. P. Oliveira, Roberto Morato Fernandez, and Marcos R. M. Fontes. 2017a. “Biophysical Studies Suggest a New Structural Arrangement of Crotoxin and Provide Insights into Its Toxic Mechanism.” Scientific Reports 7 (March):43885.

- ———. 2017b. “Biophysical Studies Suggest a New Structural Arrangement of Crotoxin and Provide Insights into Its Toxic Mechanism.” Scientific Reports 7 (March):43885.

- Hanashiro, M. A., M. H. Da Silva, and O. G. Bier. 1978. “Neutralization of Crotoxin and Crude Venom by Rabbit Antiserum to Crotalus Phospholipase A.” Immunochemistry 15 (10-11): 745–50.

- Ibanez, O. M., C. Stiffel, O. G. Ribeiro, W. K. Cabrera, S. Massa, M. de Franco, O. A. Sant’Anna, C. Decreusefond, D. Mouton, and M. Siqueira. 1992. “Genetics of Nonspecific Immunity: I. Bidirectional Selective Breeding of Lines of Mice Endowed with Maximal or Minimal Inflammatory Responsiveness.” European Journal of Immunology 22 (10): 2555–63.

- Iskandar, Heba N., Tanvi Dhere, and Francis A. Farraye. 2015. “Ulcerative Colitis: Update on Medical Management.” Current Gastroenterology Reports 17 (11): 44.

- Jameson, David M. 2014. Introduction to Fluorescence, CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Publishers, New York, NY.

- Jurjus, Abdo R., Naim N. Khoury, and Jean-Marie Reimund. 2004. “Animal Models of Inflammatory Bowel Disease.” Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods 50 (2): 81–92.

- Konarev, Petr V., Maxim V. Petoukhov, and Dmitri I. Svergun. 2016. “Rapid Automated Superposition of Shapes and Macromolecular Models Using Spherical Harmonics.” Journal of Applied Crystallography 49 (Pt 3): 953–60.

- Le Berre, Catherine, Sailish Honap, and Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet. 2023. “Ulcerative Colitis.” Lancet (London, England) 402 (10401): 571–84.

- Lees, Jonathan G., Andrew J. Miles, Frank Wien, and B. A. Wallace. 2006. “A Reference Database for Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy Covering Fold and Secondary Structure Space.” Bioinformatics 22 (16): 1955–62.

- Legaki, Evangelia, and Maria Gazouli. 2016. “Influence of Environmental Factors in the Development of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.” World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics 7 (1): 112–25.

- Lu, Jie, Monty Liong, Zongxi Li, Jeffrey I. Zink, and Fuyuhiko Tamanoi. 2010. “Biocompatibility, Biodistribution, and Drug-Delivery Efficiency of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy in Animals.” Small 6 (16): 1794–1805.

- Miles, Andrew J., and B. A. Wallace. 2018. “CDtoolX, a Downloadable Software Package for Processing and Analyses of Circular Dichroism Spectroscopic Data.” Protein Science: A Publication of the Protein Society 27 (9): 1717–22.

- Molodecky, Natalie A., Ing Shian Soon, Doreen M. Rabi, William A. Ghali, Mollie Ferris, Greg Chernoff, Eric I. Benchimol, et al. 2012. “Increasing Incidence and Prevalence of the Inflammatory Bowel Diseases with Time, Based on Systematic Review.” Gastroenterology 142 (1): 46–54.e42; quiz e30.

- Morrison, Ian D., E. F. Grabowski, and C. A. Herb. 1985. “Improved Techniques for Particle Size Determination by Quasi-Elastic Light Scattering.” Langmuir: The ACS Journal of Surfaces and Colloids 1 (4): 496–501.

- Ng, Siew C., Hai Yun Shi, Nima Hamidi, Fox E. Underwood, Whitney Tang, Eric I. Benchimol, Remo Panaccione, et al. 2017. “Worldwide Incidence and Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the 21st Century: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies.” Lancet (London, England) 390 (10114): 2769–78.

- Oliveira CLP and Pederson JS. Background subtraction and normalization in SANS and SAX [Internet]. Available from https://portal.if.usp.br/cristal/sites/portal.if.usp.br.cristal/files/Treatment_SAXS_crislpo.pdf.

- Ohkusa T. 1985. “[Production of experimental ulcerative colitis in hamsters by dextran sulfate sodium and changes in intestinal microflora].” Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai zasshi = The Japanese journal of gastro-enterology 82 (5): 1327–36.

- Okayasu, I., S. Hatakeyama, M. Yamada, T. Ohkusa, Y. Inagaki, and R. Nakaya. 1990. “A Novel Method in the Induction of Reliable Experimental Acute and Chronic Ulcerative Colitis in Mice.” Gastroenterology 98 (3): 694–702.

- Oliveira, Daniela G. de, Marcos H. Toyama, Alice M. C. Martins, Alexandre Havt, Arlândia C. L. Nobre, Sergio Marangoni, Paula R. Câmara, et al. 2003. “Structural and Biological Characterization of a Crotapotin Isoform Isolated from Crotalus Durissus Cascavella Venom.” Toxicon : Official Journal of the International Society on Toxinology 42 (1): 53–62.

- Ortega, A., D. Amorós, and J. García de la Torre. 2011. “Prediction of Hydrodynamic and Other Solution Properties of Rigid Proteins from Atomic- and Residue-Level Models.” Biophysical Journal 101 (4): 892–98.

- Perše, Martina, and Anton Cerar. 2012. “Dextran Sodium Sulphate Colitis Mouse Model: Traps and Tricks.” Journal of Biomedicine & Biotechnology 2012 (May):718617.

- Philippart, M., J. Schmidt, and B. Bittner. 2016. “Oral Delivery of Therapeutic Proteins and Peptides: An Overview of Current Technologies and Recommendations for Bridging from Approved Intravenous or Subcutaneous Administration to Novel Oral Regimens.” Drug Research 66 (3): 113–20.

- Pinto Oliveira, Cristiano Luis. 2011a. “Investigating Macromolecular Complexes in Solution by Small Angle X-Ray Scattering.” In Current Trends in X-Ray Crystallography. InTech.

- ———. 2011b. “Investigating Macromolecular Complexes in Solution by Small Angle X-Ray Scattering.” In Current Trends in X-Ray Crystallography. InTech.

- Pontieri, V., O. U. Lopes, and S. H. Ferreira. 1990. “Hypotensive Effect of Captopril. Role of Bradykinin and Prostaglandinlike Substances.” Hypertension 15 (2 Suppl): I55–58.

- Quaresma, Abel B., Aderson O. M. C. Damiao, Claudio S. R. Coy, Daniela O. Magro, Adriano A. F. Hino, Douglas A. Valverde, Remo Panaccione, et al. 2022. “Temporal Trends in the Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in the Public Healthcare System in Brazil: A Large Population-Based Study.” Lancet Regional Health. Americas 13 (September):100298.

- Rangel-Santos, A., C. Lima, M. Lopes-Ferreira, and D. F. Cardoso. 2004. “Immunosuppresive Role of Principal Toxin (crotoxin) of Crotalus Durissus Terrificus Venom.” Toxicon: Official Journal of the International Society on Toxinology 44 (6): 609–16.

- Sant’Anna, Morena Brazil, Flavia Souza Ribeiro Lopes, Louise Faggionato Kimura, Aline Carolina Giardini, Osvaldo Augusto Sant’Anna, and Gisele Picolo. 2019. “Crotoxin Conjugated to SBA-15 Nanostructured Mesoporous Silica Induces Long-Last Analgesic Effect in the Neuropathic Pain Model in Mice.” Toxins 11 (12). [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, Morena Brazil, Aline C. Giardini, Marcio A. C. Ribeiro, Flavia S. R. Lopes, Nathalia B. Teixeira, Louise F. Kimura, Michelle C. Bufalo, et al. 2020. “The Crotoxin:SBA-15 Complex Down-Regulates the Incidence and Intensity of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Through Peripheral and Central Actions.” Frontiers in Immunology 11 (October):591563.

- Shouval, Dror S., and Paul A. Rufo. 2017. “The Role of Environmental Factors in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Review.” JAMA Pediatrics 171 (10): 999–1005.

- Strober, Warren, Ivan J. Fuss, and Richard S. Blumberg. 2002. “The Immunology of Mucosal Models of Inflammation.” Annual Review of Immunology 20:495–549.

- Svergun, D., C. Barberato, and M. H. J. Koch. 1995. “CRYSOL– a Program to Evaluate X-Ray Solution Scattering of Biological Macromolecules from Atomic Coordinates.” Journal of Applied Crystallography 28 (6): 768–73. [CrossRef]

- Svergun, D.I. 1992. “Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria” J. Appl. Cryst. 25, 495-503. [CrossRef]

- Svergun, D. I. 1999. “Restoring Low Resolution Structure of Biological Macromolecules from Solution Scattering Using Simulated Annealing.” Biophysical Journal 76 (6): 2879–86.

- Svergun, D. I., M. V. Petoukhov, and M. H. Koch. 2001. “Determination of Domain Structure of Proteins from X-Ray Solution Scattering.” Biophysical Journal 80 (6): 2946–53.

- Talley, Nicholas J., Maria T. Abreu, Jean-Paul Achkar, Charles N. Bernstein, Marla C. Dubinsky, Stephen B. Hanauer, Sunanda V. Kane, et al. 2011. “An Evidence-Based Systematic Review on Medical Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease.” The American Journal of Gastroenterology 106 Suppl 1 (April):S2–25; quiz S26.

- Wallace, B. A. 2009. “Protein Characterisation by Synchrotron Radiation Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy.” Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 42 (4): 317–70.

- Whitmore, Lee, and B. A. Wallace. 2004. “DICHROWEB, an Online Server for Protein Secondary Structure Analyses from Circular Dichroism Spectroscopic Data.” Nucleic Acids Research 32 (Web Server issue): W668–73.

- Wirtz, Stefan, Clemens Neufert, Benno Weigmann, and Markus F. Neurath. 2007. “Chemically Induced Mouse Models of Intestinal Inflammation.” Nature Protocols 2 (3): 541–46.

- Xu, Bolong, Shanshan Li, Rui Shi, and Huiyu Liu. 2023. “Multifunctional Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 8 (1): 435.

- Ye, Yulan, Zhi Pang, Weichang Chen, Songwen Ju, and Chunli Zhou. 2015. “The Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Inflammatory Bowel Disease.” International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 8 (12): 22529–42.

- Zambelli, V. O., K. F. M. Pasqualoto, G. Picolo, A. M. Chudzinski-Tavassi, and Y. Cury. 2016. “Harnessing the Knowledge of Animal Toxins to Generate Drugs.” Pharmacological Research: The Official Journal of the Italian Pharmacological Society 112 (October):30–36.

- Lees JG, Miles AJ, Wien F, Wallace BA. 2006. A reference database for circular dichroism spectroscopy covering fold and secondary structure space. Bioinformatics 22(16):1955–1962.

- Wallace BA. 2009. Protein characterization by synchrotron radiation circular dichroism spectroscopy. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 42(04):317–370.

- Whitmore L, Wallace BA. 2004. DICHROWEB: an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic acids research 32:W668–W673.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).