Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Data

2.2. Primary Independent Characteristics of Individual Genes

2.3. Transcriptomic Changes of Individual Genes and Functional Pathways

3. Results

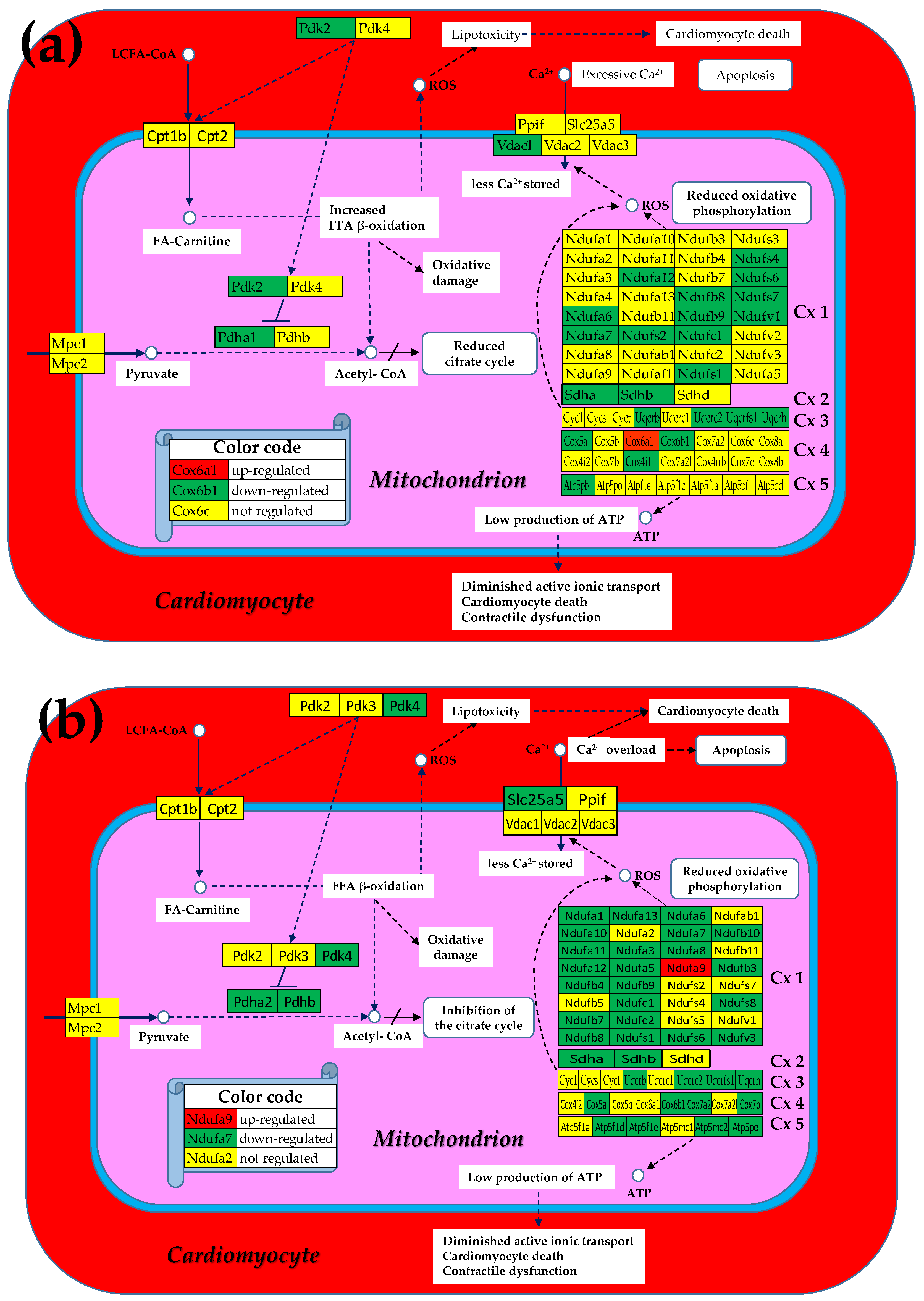

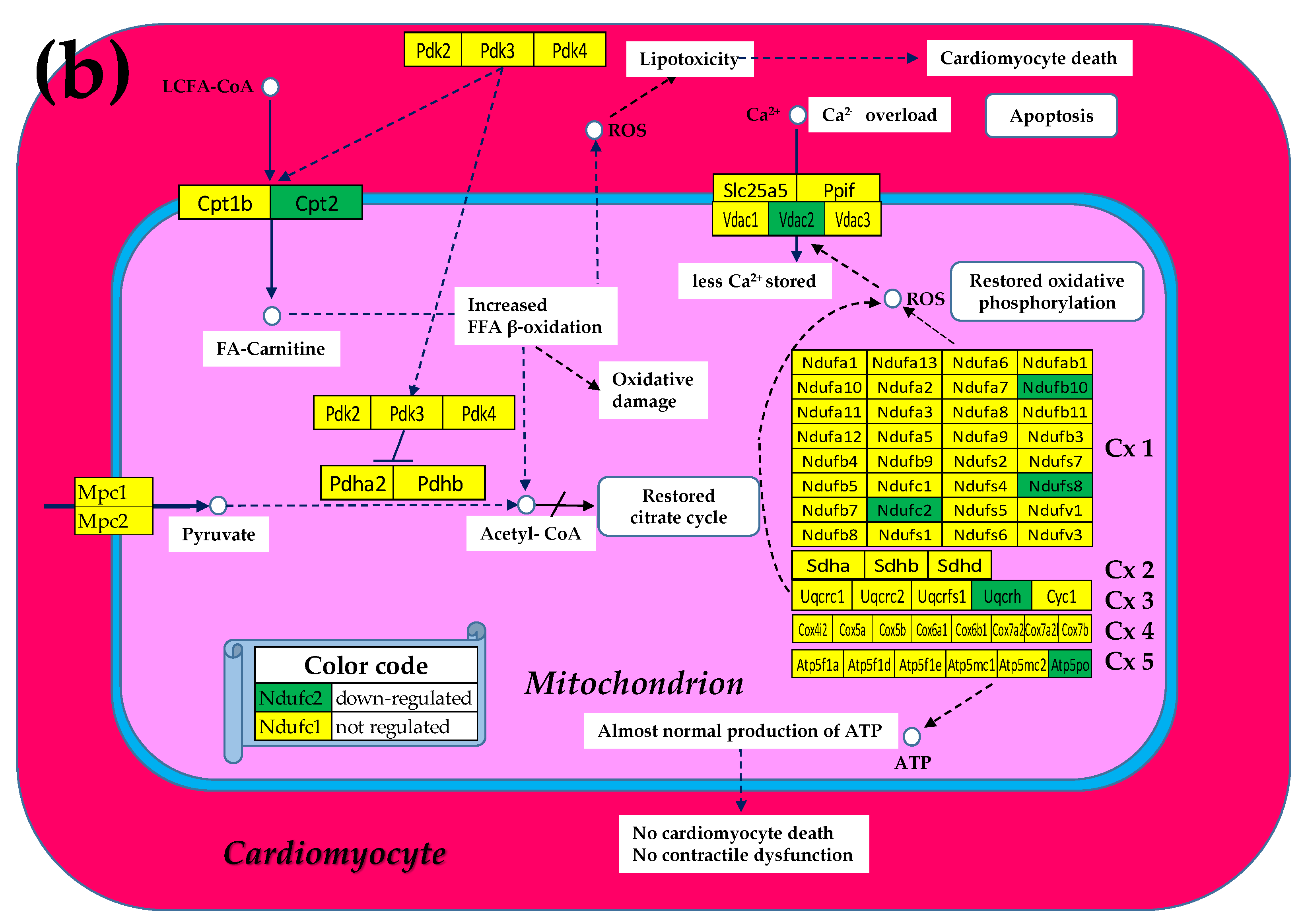

3.1. Both Chagasic Disease and Post-Ischemic Heart Failure Are Characterized by Substantial Downregulation of Mitochondrial Genes

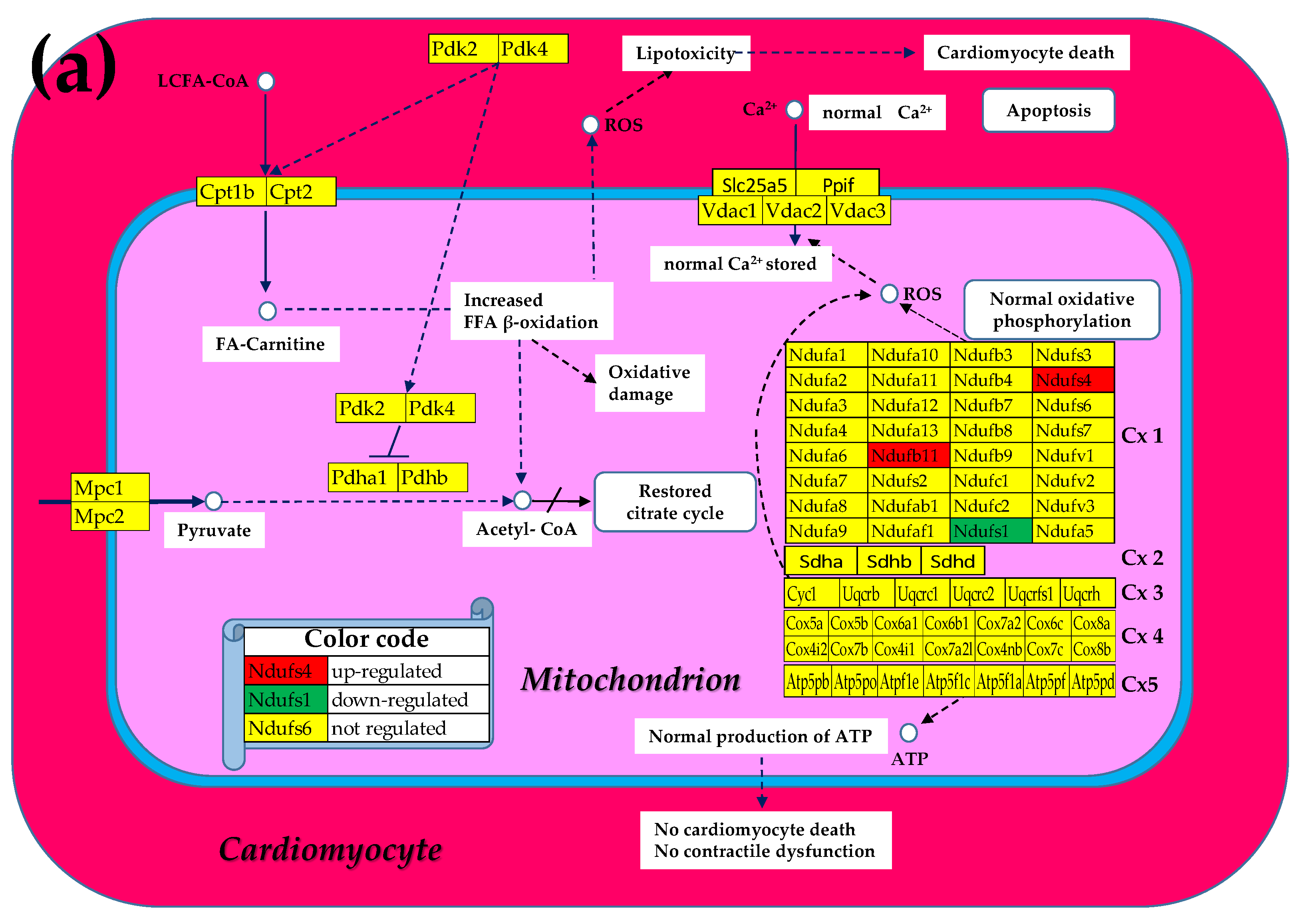

3.2. Cell Treatment Restores the Normal Expression of Most Mitochondrial Genes Altered in Both Chagasic Disease and Post-Ischemic Heart Failure

3.3. The Largest Mitochondrial Gene Contributors to the Transcriptomic Alterations in Both Chagasic and Post-Ischemic Mice

3.4. The Most and the Least Controlled Mitochondrial Genes in CCC and IHF Mice

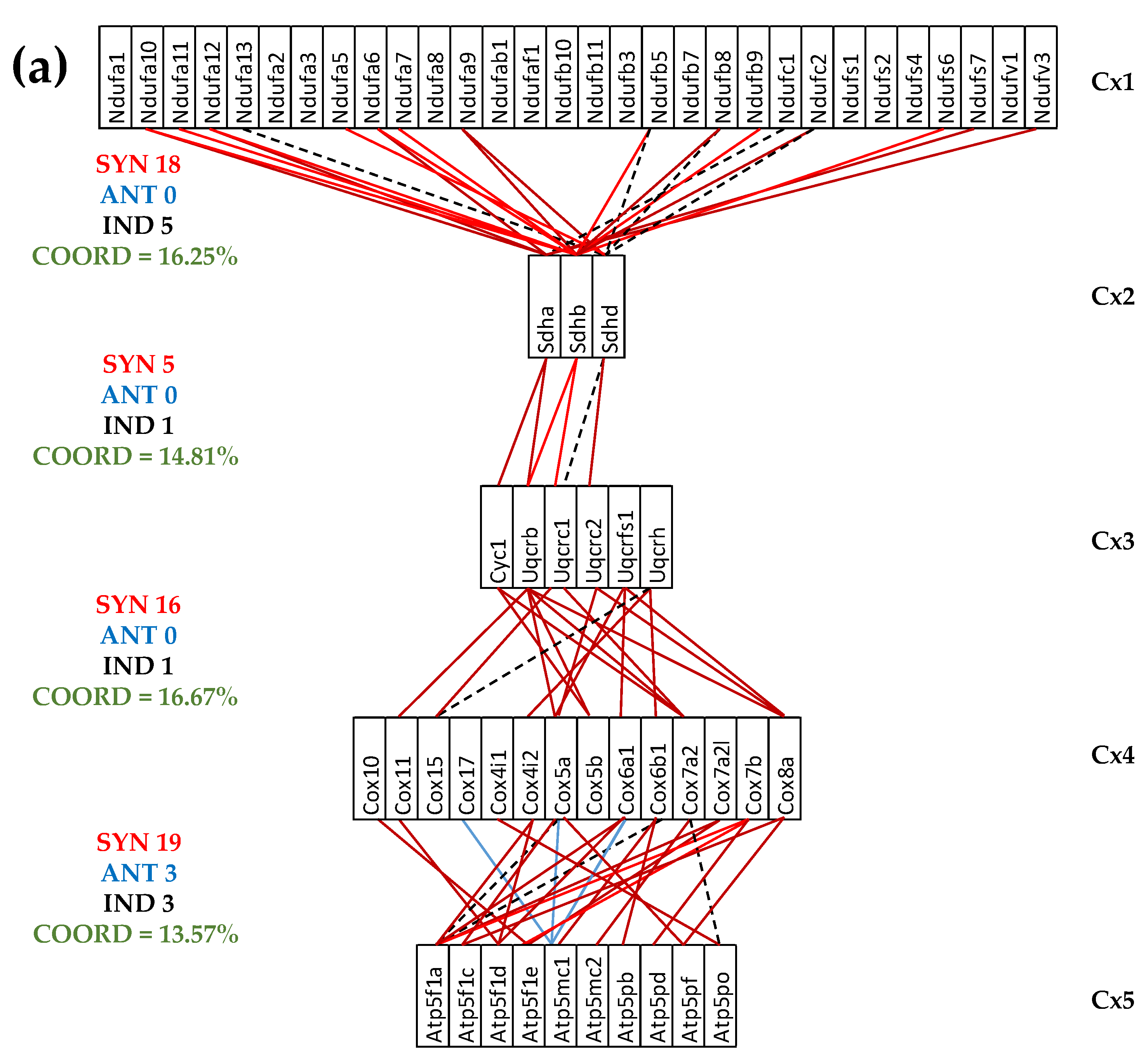

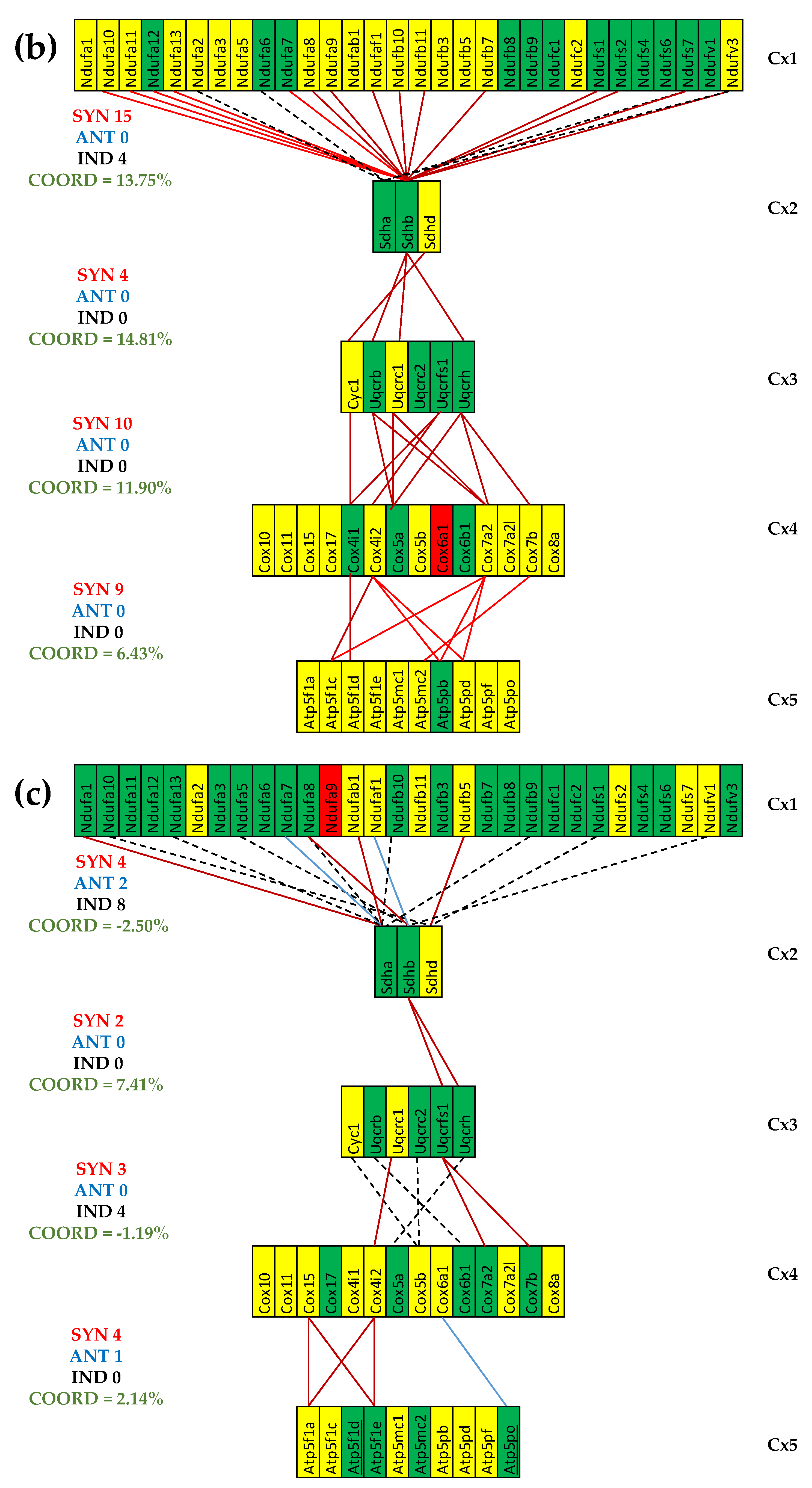

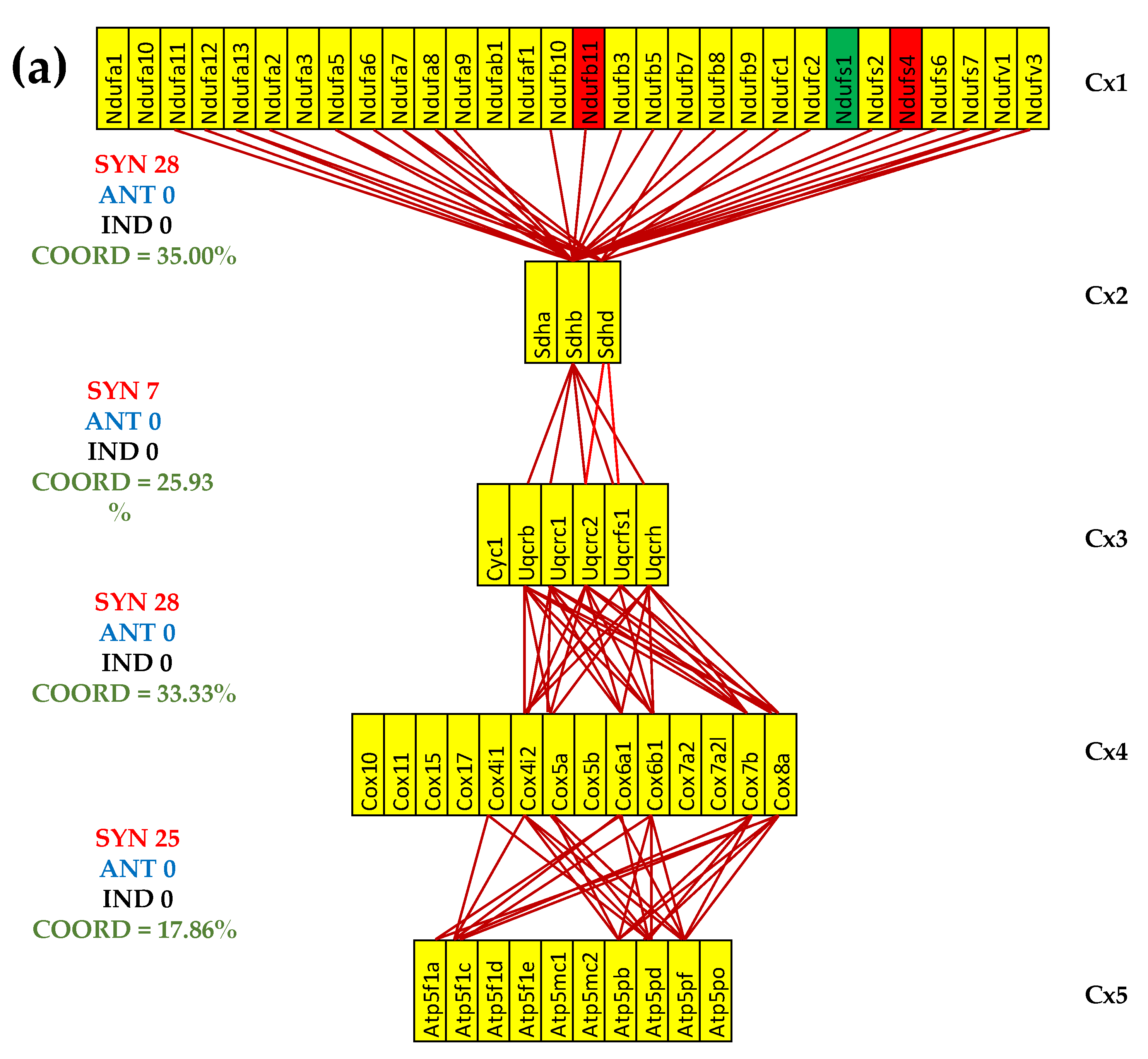

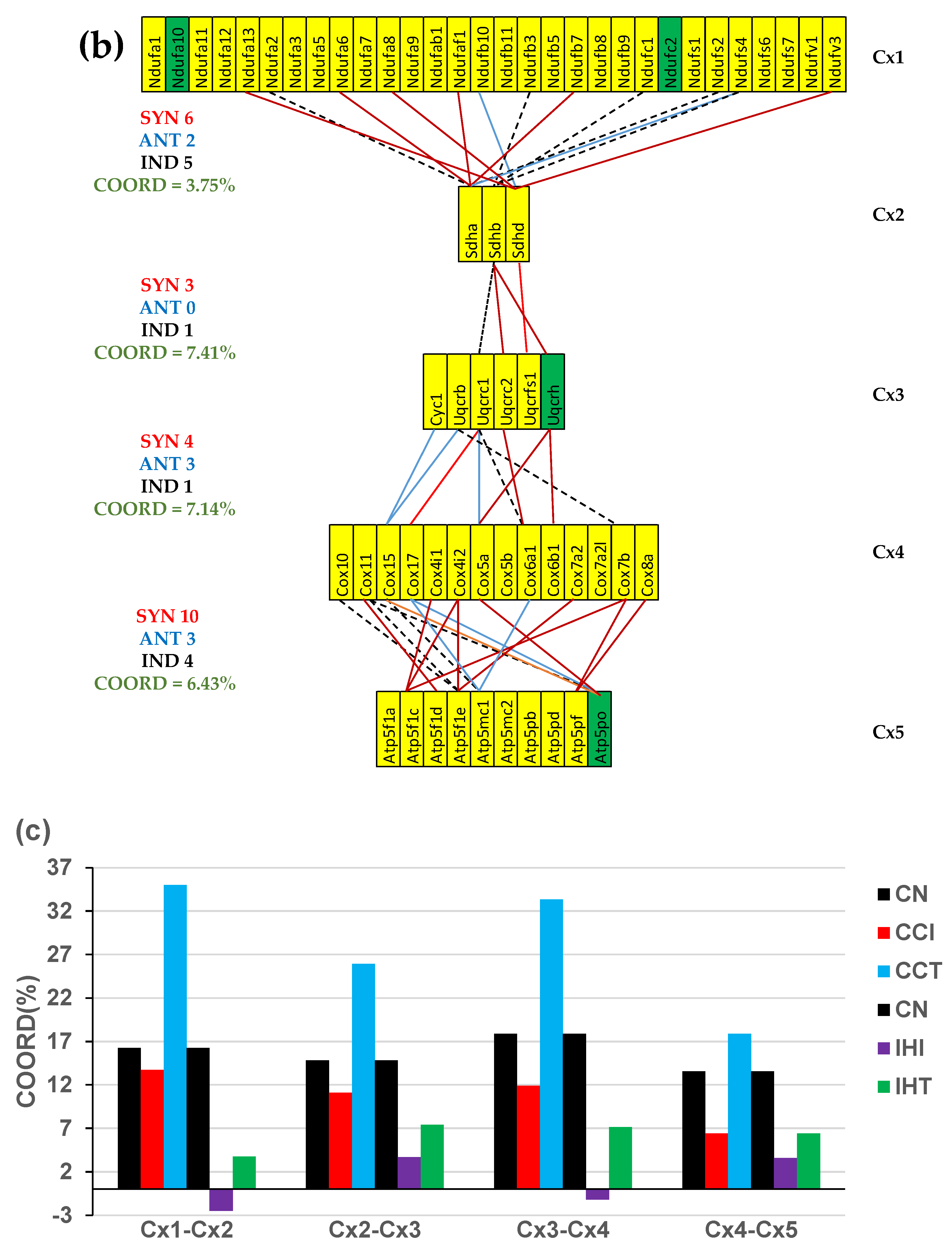

3.5. Both CCC and IHF Alter the Transcriptomic Networks of the Mitochondrial Genes by Partially Decoupling the Oxidative Phosphorylation Complexes

3.6. Stem Cell Treatment Benefits for the Transcriptomic Coupling of the Oxidative Phosphorylation Complexes

3.7. Both CCC and IHF Alter the Hierarchy of Mitochondrial Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinton, A. Jr.; Claypool, S.M.; Neikirk, K.; Senoo, N.; Wanjalla, C.N.; Kirabo, A.; Williams, C.R. Mitochondrial Structure and Function in Human Heart Failure. Circ Res 2024, 135, 372–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy E, Ardehali H, Balaban RS, DiLisa F, Dorn GW 2nd, Kitsis RN, Otsu K, Ping P, Rizzuto R, Sack MN et al. American Heart Association Council on Basic Cardiovascular Sciences, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology. Mitochondrial Function, Biology, and Role in Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ Res. 2016, 118, 1960–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Hou, L.; Lv, Y.; Xi, L.; Tian, Z. Postinfarction exercise training alleviates cardiac dysfunction and adverse remodeling via mitochondrial biogenesis and SIRT1/PGC-1alpha/PI3K/Akt signaling. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 23705–23718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koka, S.; Aluri, H.S.; Xi, L.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Kukreja, R.C. Chronic inhibition of phosphodiesterase 5 with tadalafil attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic hearts: potential role of NO/SIRT1/PGC-1alpha signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014, 306, H1558–H1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.P.S.; Roda, V.M.P.; Andrieux, P.; Kalil, J.; Chevillard, C.; Cunha-Neto, E. Inflammation and mitochondria in the pathogenesis of chronic Chagas disease cardiomyopathy. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2023, 248, 2062–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.G.; Kukreja, R.C.; Das, A.; Chen, Q.; Lesnefsky, E.J.; Xi, L. Dietary nitrate supplementation protects against Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy by improving mitochondrial function. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 57, 2181–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, G.A. Trypanosoma cruzi/Triatomine Interactions—A Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouali, R.; Bousbata, S. Rhodnius prolixus (kissing bug). Trends Parasitol, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Belbin, T.J.; Spray, D.C.; Iacobas, D.A.; Weiss, L.M.; Kitsis, R.N.; Wittner, M.; Jelicks, L.A.; Scherer, P.E.; Ding, A.; et al. Microarray analysis of changes in gene expression in a murine model of chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy. Parasitol Res 2003, 91, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.; Tanowitz, H.B.; Garg, N.J. Pathogenesis of Chronic Chagas Disease: Macrophages, Mitochondria, and Oxidative Stress. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep, 2018, 5, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.; Srikanth, K.K.; Bommireddi, A.; Leong, T.K.; Miller, D.A.; Ambrosy, A.P.; Zaroff, J. Chagas Disease in Northern California: Observed Prevalence, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes Within an Integrated Health Care Delivery System. Perm J. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.C.; da Silva, M.T.S.; Bezerra Dos Santos, L.; Abdala, M.G.G.; Lopes, A.B.O.; de Oliveira, G.A.; Guedes-da-Silva, F.H.; Rigoni, T.D.S.; Damasceno, F.S.; Barros-Neto, J.A.; et al. Epidemiological assessment of the first year of mandatory notification of chronic Chagas disease in Alagoas. Northeast Brazil. Acta Trop. 2025, 270, 107805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, N.L.; Hamer, G.L.; Moreno-Peniche, B.; Mayes, B.; Hamer, S.A. Chagas Disease, an Endemic Disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2025, 31, 1691–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunkofske, M.E.; Sanchez-Valdez, F.J.; Tarleton, R.L. The importance of persistence and dormancy in Trypanosoma cruzi infection and Chagas disease. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2025, 86, 102615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telleria, J.; Costales, J.A. An Overview of Trypanosoma cruzi Biology Through the Lens of Proteomics: A Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Popov, V.L.; Papaconstantinou, J. Profiling gene transcription reveals a deficiency of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected murine hearts: implications in chagasic myocarditis development. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003, 1638, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, A.; Lo Presti, M.S.; Rivarola, H.W.; Mentesana, G.G.; Pons, P.; Fretes, R.; Paglini-Oliva, P. Mitochondrial involvement in chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2011, 105, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, L.E.; Serrano-García, A.Y.; Rojas, L.Z.; Silva-Sieger, F.; Navarro, M.; Aguilera, L.; Gómez-Ochoa, S.A.; Morillo, C.A. Beyond cardiac embolism and cryptogenic stroke: unveiling the mechanisms of cerebrovascular events in Chagas disease. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2025, 50, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.J.D.N.; da Silva, P.S.; Saraiva, R.M.; Sangenis, L.H.C.; de Holanda, M.T.; Sperandio da Silva, G.M.; Mendes, F.S.N.S.; Xavier, I.G.G.; Costa, H.S.; Gonçalves, T.R.; et al. Food insecurity is associated with decreased quality of life in patients with chronic Chagas disease. PLoS One. 2025, 20, e0328466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, L.E.; Serrano-García, A.Y.; Rojas, L.Z.; Silva-Sieger, F.; Navarro, M.; Aguilera, L.; Gómez-Ochoa, S.A.; Morillo, C.A. Beyond cardiac embolism and cryptogenic stroke: unveiling the mechanisms of cerebrovascular events in Chagas disease. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2025, 50, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Silva, T.G.; Figueiredo, A.; Morais, K.L.P.; Apostólico, J.; Pantaleao, A.; Mutarelli, A.; Araújo, S.S.; Nunes, M.D.C.P.; Gollob, K.J.; Dutra, W.O. Single-cell targeted transcriptomics reveals subset-specific immune signatures differentiating asymptomatic and cardiac patients with chronic Chagas disease. J Infect Dis. 2025, jiaf269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, C.; So, J.; Castro-Sesquen, Y.E.; DeToy, K.; Gutierrez Guarnizo, S.A.; Jahanbakhsh, F.; Malaga Machaca, E.; Miranda-Schaeubinger, M.; Chakravarti, I.; Cooper, V.; et al.; Chagas Working Group Immunologic changes in the peripheral blood transcriptome of individuals with early-stage chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2025, 45, 101090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares MB, de Lima RS, Rocha LL, Vasconcelos JF, Rogatto SR, dos Santos RR, Iacobas S, Goldenberg RC, Iacobas DA, Tanowitz HB. et al. Gene expression changes associated with myocarditis and fibrosis in hearts of mice with chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy. J Infect Dis 2010, 202, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, R.C.; Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Rocha, L.L.; da Silva de Azevedo, Fortes, F. ; Vairo, L.; Nagajyothi, F.; Campos de Carvalho. A.C.; Tanowitz, H.B. et al. Transcriptomic alterations in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected cardiac myocytes. Microbes Infect 2009, 11, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adesse, D.; Goldenberg, R.C.; Fortes, F.S.; Jasmin, Iacobas, D. A.; Iacobas, S.; Campos de Carvalho, A.C.; de Narareth Meirelles, M.; Huang, H.; Soares, M.B. et al. Gap junctions and chagas disease. Adv Parasitol 2011, 76, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinxin, Z.; Pan, H.; Qiao, L. Research progress of connexin 43 in cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025, 12, 1650548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-da-Silva, J.E.; Gonçalves-Santos, E.; Domingues, E.L.B.C.; Caldas, I.S.; Lima, G.D.A.; Diniz, L.F.; Gonçalves, R.V.; Novaes, R.D. The mitochondrial uncoupler 2,4-dinitrophenol modulates inflammatory and oxidative responses in Trypanosoma cruzi-induced acute myocarditis in mice. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2024, 72, 107653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisimura, L.M.; Coelho, L.L.; de Melo, T.G.; Vieira, P.C.; Victorino, P.H.; Garzoni, L.R.; Spray, D.C.; Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Tanowitz, H.B.; et al. Trypanosoma cruzi Promotes Transcriptomic Remodeling of the JAK/STAT Signaling and Cell Cycle Pathways in Myoblasts. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimani, S.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Salehipourmehr, H.; Taghavi Narmi, M.; Lotfimehr, H.; Mehdipour, R. Therapeutic Potential of Endothelial Progenitor Cells in Angiogenesis and Cardiac Regeneration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Rodent Models. Adv Pharm Bull. 2025, 15, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares MB, Lima RS, Souza BS, Vasconcelos JF, Rocha LL, Dos Santos RR, Iacobas S, Goldenberg RC, Lisanti MP, Iacobas DA. et al. Reversion of gene expression alterations in hearts of mice with chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy after transplantation of bone marrow cells. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 1448–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Tanowitz, H.B.; Campos de Carvalho, A.; Spray, D.C. Functional genomic fabrics are remodeled in a mouse model of Chagasic cardiomyopathy and restored following cell therapy. Microbes Infect 2018, 20, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, T.; Soliman-Aboumarie, H. Review of Current Management of Myocardial Infarction. J Clin Med. 2025, 14, 6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.; White, H.D.; Lopez-Ayala, P.; de Silva, R.; Kaski, J.C. Great debate: the universal definition of myocardial infarction is flawed and should be put to rest. Eur Heart J. 2025, ehaf641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taggart C, Ferry AV, Chapman AR, Schulberg SD, Bularga A, Wereski R, Boeddinghaus J, Kimenai DM, Lowry MTH, Chew DP. et al. The assessment and management of patients with type 2 myocardial infarction: an international Delphi study. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, H.; Chen, G.; Wei, P.; Lin, F.; Zhao, G. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a central hub linking Na+/Ca2+ homeostasis and inflammation in ischemic arrhythmias: therapeutic implications. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025, 12, 1506501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meco, M.; Giustiniano, E.; Nisi, F.; Zulli, P.; Agosteo, E. MAPK, PI3K/Akt Pathways, and GSK-3β Activity in Severe Acute Heart Failure in Intensive Care Patients: An Updated Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Ji, H.; Modarresi Chahardehi, A. JAK/STAT pathway in myocardial infarction: Crossroads of immune signaling and cardiac remodeling. Mol Immunol. 2025, 186, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Yang, Y.; Qing, O.; Linhui, J.; Haotao, S.; Liu, C.; Li, G.; Nasser, M.I. Chrysin Attenuates Myocardial Cell Apoptosis in Mice. Cardiovasc Toxicol. [CrossRef]

- Lachtermacher, S.; Esporcatte, B.L.; Montalvao, F.; Costa, P.C.; Rodrigues, D.C.; Belem, L.; Rabischoffisky, A.; Faria Neto, H.C.; Vasconcellos, R.; Iacobas, S. et. Cardiac gene expression and systemic cytokine profile are complementary in a murine model of post-ischemic heart failure. Braz J Med Biol Res 2010, 43, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachtermacher, S.; Esporcatte, B.L.; Fortes, Fda, S. ; Rocha, N.N.; Montalvao, F.; Costa, P.C.; Belem, L.; Rabischoffisky, A.; Faria Neto, H.C.; Vasconcellos, R. et al. Functional and transcriptomic recovery of infarcted mouse myocardium treated with bone marrow mononuclear cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2012, 8, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Yang, F.; Iacobas, D.A.; Xi, L. Mental disorders after myocardial infarction: potential mediator role for chemokines in heart-brain interaction? J Geriatr Cardiol 2024, 21, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxidative phosphorilation. Available online: https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/mmu00190 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/pathway/mmu05415 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Gene expression changes associated with myocarditis and fibrosis in hearts of mice with chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE17363 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Cardiac gene expression and systemic cytokine profile are complementary in a murine model of post ischemic heart failure. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE18703 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Therapy with bone marrow cells recovers gene expression alterations in hearts of mice with chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE24088 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Functional and Transcriptomic Recovery of Infarcted Mouse Myocardium Treated with Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE29769. Accessed on Sept 1st, 2025.

- Adesse, D.; Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Garzoni, L.R.; Meirelles Mde, N.; Tanowitz, H.B.; Spray. D.C. Transcriptomic signatures of alterations in a myoblast cell line infected with four distinct strains of Trypanosoma cruzi. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010, 82, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A.; Iacobas, S.; Lee, P.R.; Cohen, J.E.; Fields, R.D. Coordinated Activity of Transcriptional Networks Responding to the Pattern of Action Potential Firing in Neurons. Genes. 2019, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A. Biomarkers, Master Regulators and Genomic Fabric Remodeling in a Case of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Genes. 2020, 11, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, D.A. ; Xi, L Theory and Applications of the (Cardio) Genomic Fabric Approach to Post-Ischemic and Hypoxia-Induced Heart Failure. J Pers Med 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.M.; Lees, J.G.; Murray, A.J.; Velagic, A.; Lim, S.Y.; De Blasio, M.J.; Ritchie, R.H. Precision Medicine: Therapeutically Targeting Mitochondrial Alterations in Heart Failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2025, 10, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, A.; Mengozzi, A.; Geiger, M.; Gorica, E.; Mohammed, S.A.; Paneni, F.; Ruschitzka, F.; Costantino, S. ; Mitochondrial epigenetics in aging and cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023, 10, 1204483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrangelo, D.; Lopa, C.; Litterio, M.; Cotugno, M.; Rubattu, S.; Lombardi, A. Metabolic Disturbances Involved in Cardiovascular Diseases: The Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Altered Bioenergetics and Oxidative Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalla, N.S.; Ostadal, P.; Tappia, P.S. Involvement of Oxidative Stress in Mitochondrial Abnormalities During the Development of Heart Disease. Biomedicines. 2025, 13, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Blandino, A.; Scherer, D.; Zulantay, I.; Apt, W.; Varela, N.M.; Llancaqueo, M.; Garcia, L.; Ortiz, L.; Nicastri, E.; et al. Small-RNA sequencing identifies serum microRNAs associated with abnormal electrocardiography findings in patients with Chagas disease. J Infect. 2025, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Xu, H. Diagnosis and treatment of post-acute myocardial infarction ventricular aneurysm: A review. Medicine 2025, 104, e43696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formosa, L.E.; Muellner-Wong, L.; Reljic, B.; Sharpe, A.J.; Jackson, T.D.; Beilharz, T.H.; Stojanovski, D.; Lazarou, M.; Stroud, D.A.; Ryan, M.T. Dissecting the Roles of Mitochondrial Complex I Intermediate Assembly Complex Factors in the Biogenesis of Complex I. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Zhao, H.; Luo, L.; Wu, W. Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Supplementation to Alleviate Heart Failure: A Mitochondrial Dysfunction Perspective. Nutrients. 2025, 17, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdemir, N.; Cakir, C.; Topcu, U.; Uysal, F. A Comprehensive Review of Mitochondrial Complex I During Mammalian Oocyte Maturation. Genesis. 2025, 63, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Guan, R.; Rotstein, O.D.; Liu, X.; Wen, X.Y. ndufa7 plays a critical role in cardiac hypertrophy. J Cell Mol Med. 2020, 24, 13151–13162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckelsma, V.L.; Levinger, I.; McKenna, M.J.; Formosa, L.E.; Ryan, M.T.; Petersen, A.C.; Anderson, M.J.; Murphy, R.M. Preservation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial content in older adults: relationship between mitochondria, fibre type and high-intensity exercise training. J Physiol. 2017, 595, 3345–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Hu, S.; Liu, X.; He, M.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; Huang, M.; Fang, Q.; Wang, Y. CAV3 alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy via inhibiting NDUFA10-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Jin, X.; Xia, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, C.; Shao, D.; Fang, N.; Meng, C. Characterization of mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase 1alpha subcomplex 10 variants in cardiac muscles from normal Wistar rats and spontaneously hypertensive rats: Implications in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Mol Med Rep 2016, 13, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iverson, T.M.; Singh, P.K.; Cecchini, G. An evolving view of complex II-noncanonical complexes, megacomplexes, respiration, signaling, and beyond. J Biol Chem. 2023, 299, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Fasham, J.; Al-Hijawi, F.; Qutob, N.; Gunning, A.; Leslie, J.S.; McGavin, L.; Ubeyratna, N.; Baker, W.; Zeid, R.; et al. Consolidating biallelic SDHD variants as a cause of mitochondrial complex II deficiency. Eur J Hum Genet. 2021, 29, 1570–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Qiao, L.; Yu, R.; Ren, H.; Zhao, A.; Sun, Y.; Wang, A.; Li, B.; Wang, X. et. Exploring the biological basis for the identification of different syndromes in ischemic heart failure based on joint multi-omics analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1641422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielmann, N.; Schenkl, C.; Komlodi, T.; da Silva-Buttkus, P.; Heyne, E.; Rohde, J.; Amarie, O.V.; Rathkolb, B.; Gnaiger, E.; Doenst, T.; et al. Knockout of the Complex III subunit Uqcrh causes bioenergetic impairment and cardiac contractile dysfunction. Mamm Genome 2023, 34, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čunátová, K.; Fernández-Vizarra, E. Pathological variants in nuclear genes causing mitochondrial complex III deficiency: An update. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2024, 47, 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkler, C.A.; Kalpage, H.; Shay, J.; Lee, I.; Malek, M.H. Grossman, L.I.; Huttemann, M. Tissue- and Condition-Specific Isoforms of Mammalian Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunits: From Function to Human Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 1534056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.J.; Garg, N. Oxidative modification of mitochondrial respiratory complexes in response to the stress of Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004, 37, 2072–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Velasquez, S.; Durrani, S.; Jiang, M.; Neiman, M.; Crocker, J.S.; Benoit, J.B.; Rubinstein, J.; Paul, A.; Ahmed, R.P. MicroRNA-1825 induces proliferation of adult cardiomyocytes and promotes cardiac regeneration post-ischemic injury. Am J Transl Res 2017, 9, 3120–3137. [Google Scholar]

- Elbatarny, M.; Lu, Y.T.; Hu, M.; Coles, J.; Mital, S.; Ross-White, A.; Honjo, O.; Barron, D.J.; Gramolini, A.O. Systems biology approaches investigating mitochondrial dysfunction in cyanotic heart disease: a systematic review. EBioMedicine 2025, 118, 105839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Gu, Y. Analysis of the prognostic value of mitochondria-related genes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024, 24, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hejzlarova, K.; Mracek, T.; Vrbacky, M.; Kaplanova, V.; Karbanova, V.; Nuskova, H.; Pecina, P.; Houstek, J. Nuclear genetic defects of mitochondrial ATP synthase. Physiol Res 2014, 63, S57–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, J.A.; Havlickova, V.; Zimmermann, F.; Magler, I.; Kaplanova, V.; Jesina, P.; Pecinova, A.; Nuskova, H.; Koch, J.; Sperl, W.; et al. Mitochondrial ATP synthase deficiency due to a mutation in the ATP5E gene for the F1 epsilon subunit. Hum Mol Genet 2010, 19, 3430–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereyra, A.S.; Hasek, L.Y.; Harris, K.L.; Berman, A.G.; Damen, F.W.; Goergen, C.J.; Elli,s J. M. Loss of cardiac carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 results in rapamycin-resistant, acetylation-independent hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 18443–18456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Escamilla, I.; Benedicto, C.; Pérez-Carrillo, L.; Delgado-Arija, M.; González-Torrent, I.; Vilchez, R.; Martínez-Dolz, L.; Portolés, M.; Tarazón, E.; Roselló-Lletí, E. Alterations in Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation System: Relationship of Complex V and Cardiac Dysfunction in Human Heart Failure. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Song, L.; Hu, L.; Guo, D.; Ren, G.; Peng, T.; Liu, M.; Fang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, M.; et al. Cardiac-specific overexpression of Ndufs1 ameliorates cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction by alleviating mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. Exp Mol Med. 2022, 54, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Li, L.; Ma, L.; Song, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. Activation of RXRα exerts cardioprotection through transcriptional upregulation of Ndufs4 in heart failure. Sci Bull 2024, 69, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Hu, S.; Liu, X.; He, M.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; Huang, M.; Fang, Q.; Wang, Y. CAV3 alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy via inhibiting NDUFA10-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. J Transl Med. 2024, 22, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederich MW, Erdogan AJ, Coughlin CR, 2nd, Elos MT, Jiang H, O'Rourke CP, Lovell MA, Wartchow E, Gowan K, Chatfield KC, Chick WS, Spector EB, Van Hove JLK and Riemer J. Mutations in the accessory subunit NDUFB10 result in isolated complex I deficiency and illustrate the critical role of intermembrane space import for complex I holoenzyme assembly. Hum Mol Genet 2017, 26, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhang, P.; Pei, F. COX6B1 relieves hypoxia/reoxygenation injury of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes by regulating mitochondrial function. Biotechnol Lett. 2019, 41, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, S.S.; Souza, M.A.; Santos, E.C.; Caldas, I.S.; Gonçalves, R.V.; Novaes, R.D. Oxidative stress, cardiomyocytes premature senescence and contractile dysfunction in in vitro and in vivo experimental models of Chagas disease. Acta Trop. 2023, 244, 106950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Miranda, A.; Joviano-Santos, J.V.; Ribeiro, G.A.; Botelho, A.F.M.; Rocha, P.; Vieira, L.Q.; Cruz, J.S.; Roman-Campos, D. Reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide imbalances lead to in vivo and in vitro arrhythmogenic phenotype in acute phase of experimental Chagas disease. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernansanz-Agustín, P.; Enríquez, J.A. Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species by Mitochondria. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frade, A.F.; Guerin, H.; Nunes, J.P.S.; Silva, L.; Roda, V.M.P.; Madeira, R.P.; Brochet, P.; Andrieux, P.; Kalil, J.; Chevillard, C.; et al. Cardiac and Digestive Forms of Chagas Disease: An Update on Pathogenesis, Genetics, and Therapeutic Targets. Mediators Inflamm 2025, 8862004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.H.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.H.; Yao, B.C.; Chen, Q.L.; Wang, L.Q.; Guo, Z.G.; Guo, S.Z. NDUFB11 and NDUFS3 regulate arterial atherosclerosis and venous thrombosis: Potential markers of atherosclerosis and venous thrombosis. Medicine 2023, 102, e36133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajyothi, J.F.; Weiss, L.M. Advances in understanding the role of adipose tissue and mitochondrial oxidative stress in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. F1000Res. 2019, 8, F1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, A.K. OXPHOS mediators in acute myeloid leukemia patients: Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for personalized medicine. World J Surg Oncol. 2024, 22, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkenani, M.; Barallobre-Barreiro, J.; Schnelle, M.; Mohamed, B.A.; Beuthner, B.E.; Jacob, C.F.; Paul, N.B.; Yin, X.; Theofilatos, K.; Fischer, A. et. Cellular and extracellular proteomic profiling of paradoxical low-flow low-gradient aortic stenosis myocardium. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024, 11, 1398114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Bai, J.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, Z. Molecular Signatures of Mitochondrial Complexes Involved in Alzheimer's Disease via Oxidative Phosphorylation and Retrograde Endocannabinoid Signaling Pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 9565545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparks, L.M.; Xie, H.; Koza, R.A.; Mynatt, R.; Hulver, M.W.; Bray, G.A.; Smith, S.R. A high-fat diet coordinately downregulates genes required for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2005, 54, 1926–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Social Science Statistics. Available online: https://www.socscistatistics.com/pvalues/pearsondistribution.aspx (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ahmad, B.; Dumbuya, J.S.; Li, W.; Tang, J.X.; Chen, X.; Lu, J. Evaluation of GFM1 mutations pathogenicity through in silico tools, RNA sequencing and mitophagy pahtway in GFM1 knockout cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025, 304 Pt 2 Pt 2, 140970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemeshko, V.V. Mechanism of Na+ ions contribution to the generation and maintenance of a high inner membrane potential in mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2025, 149571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedor, J.G.; Jones, A.J.Y.; Di Luca, A.; Kaila, V.R.I.; Hirst, J. Correlating kinetic and structural data on ubiquinone binding and reduction by respiratory complex I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017, 114, 12737–12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galemou Yoga, E.; Haapanen, O.; Wittig, I.; Siegmund, K.; Sharma, V.; Zickermann, V. Mutations in a conserved loop in the PSST subunit of respiratory complex I affect ubiquinone binding and dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2019, 1860, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röpke, M.; Saura, P.; Riepl, D.; Pöverlein, M.C.; Kaila, V.R.I. Functional Water Wires Catalyze Long-Range Proton Pumping in the Mammalian Respiratory Complex I. J Am Chem Soc. 2020, 142, 21758–21766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yawar, W.; Farooqui, A.R.; Ali, S.; Lathiya, N.; Ghous, Z.; Sultan, R.; Alhomrani, M.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Almalki, A.A.; et al. Transcriptomics data integration and analysis to uncover hallmark genes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Transl Res. 2024, 16, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobas, S.; Ede, N.; Iacobas, D.A. The Gene Master Regulators (GMR) Approach Provides Legitimate Targets for Personalized, Time-Sensitive Cancer Gene Therapy. Genes. 2019, 10, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| THE LARGEST CONTRIBUTORS TO THE MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSCRIPTOME ALTERATION IN CCC MICE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Description | AVE | X-IN | P | |WIR| | X-IT | P | |WIR| |

| Cox4i1 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV isoform 1 | 165 | -1.69 | 0.02 | 111 | -2.05 | 0.45 | 95 |

| Sdha | Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit A, flavoprotein | 61 | -2.49 | 0.00 | 91 | -1.71 | 0.16 | 36 |

| Atp5pb | ATP synthase peripheral stalk-membrane subunit b | 62 | -2.35 | 0.00 | 83 | -1.47 | 0.27 | 21 |

| Ndufa4 | Mlrq-like protein | 105 | -1.78 | 0.09 | 76 | -1.46 | 0.27 | 35 |

| Ndufs1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 1 | 34 | -3.02 | 0.01 | 68 | -2.20 | 0.05 | 39 |

| Average mitochondrial |WIR| | 54 | 49 | ||||||

| The largest overall contributors to the entire transcriptome alteration in CCC mice | ||||||||

| Pln | Phospholamban | 148 | -2.64 | 0.09 | 222 | -2.65 | 0.31 | 167 |

| Overall average |WIR| | 2.24 | 1.15 | ||||||

| THE LARGEST CONTRIBUTORS TO THE MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSCRIPTOME ALTERATION IN IHF MICE | ||||||||

| Gene | Description | AVE | X-IN | P | |WIR| | X-IT | P | |WIR| |

| Cox5a | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit Va | 49 | -59.69 | 0.09 | 2603 | -2.29 | 0.28 | 45 |

| Uqcrh | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase hinge protein | 59 | -2.64 | 0.02 | 94 | -1.94 | 0.03 | 54 |

| Cox7a2 | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIIa 2 | 49 | -2.67 | 0.00 | 81 | -1.20 | 0.16 | 8 |

| Cox6b1 | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIb polypeptide 1 | 49 | -2.66 | 0.00 | 80 | 1.09 | 0.48 | 2 |

| Cox7b | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIb | 64 | -2.28 | 0.03 | 80 | -1.07 | 0.69 | 1 |

| Average mitochondrial |WIR| | 69 | 12 | ||||||

| The largest overall contributors to the entire transcriptome alteration in IHF mice | ||||||||

| Cox5a | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit Va | 49 | -59.69 | 0.09 | 2603 | -2.29 | 0.28 | 45 |

| Overall average |WIR| | 1.63 | 0.70 | ||||||

| THE MOST AND THE LEAST CONTROLLED MITO GENES IN CCC MICE | RCS-FC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Description | CN | IN | IT | IN | IT | |

| Ndufa10 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A10 | 3.86 | -1.17 | -0.64 | -32.80 | -22.70 | |

| Cox7b | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIb | 2.59 | -0.42 | -1.59 | -8.05 | -18.12 | |

| Ndufb10 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit B10 | 2.15 | -0.95 | -0.68 | -8.56 | -7.13 | |

| Vdac2 | Voltage-dependent anion channel 2 | 1.06 | 2.59 | -0.63 | 2.89 | -3.23 | |

| Mpc2 | mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 2 | 0.32 | 1.54 | 0.68 | 2.34 | 1.28 | |

| Cox4nb | COX4 neighbor | 0.81 | 1.28 | 0.98 | 1.38 | 1.12 | |

| Ndufb5 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit B5 | 0.43 | -0.53 | 1.66 | -1.95 | 2.33 | |

| Ndufb11 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit B11 | 0.99 | 0.54 | 1.62 | -1.36 | 1.55 | |

| Ndufaf4 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A4 | 0.29 | -0.92 | 1.37 | -2.32 | 2.11 | |

| Sdhd | Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit D, integral membrane protein | -1.87 | -0.32 | -0.30 | 2.92 | 2.96 | |

| Cox5a | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit Va | -1.58 | 1.17 | -2.53 | 6.69 | -1.94 | |

| Ndufa9 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A9 | -1.26 | -2.64 | -0.32 | -2.60 | 1.93 | |

| Cpt2 | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 | 0.53 | -1.67 | 0.21 | -4.60 | -1.25 | |

| Pdk2 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isoenzyme 2 | 0.60 | -1.43 | -0.67 | -4.09 | -2.41 | |

| Ppif | Peptidylprolyl isomerase F (cyclophilin F) | 0.57 | -1.41 | -0.56 | -3.94 | -2.18 | |

| Cox7b | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIb | 2.59 | -0.42 | -1.59 | -8.05 | -18.12 | |

| Atp5pf | ATP synthase peripheral stalk subunit F6 | 1.52 | -0.81 | -1.58 | -5.01 | -8.53 | |

| Cox4i1 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV isoform 1 | 0.66 | -0.20 | -1.56 | -1.81 | -4.65 | |

| THE MOST AND THE LEAST CONTROLLED MITO GENES IN IHF MICE | RCS-FC | ||||||

| Cox6b1 | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIb polypeptide 1 | 1.36 | 4.38 | 0.05 | 8.13 | -2.48 | |

| Atp5f1e | ATP synthase F1 subunit epsilon | -0.79 | 2.68 | 0.68 | 11.07 | 2.77 | |

| Atp5mc2 | ATP synthase membrane subunit c locus 2 | 0.52 | 1.75 | -0.37 | 2.35 | -1.86 | |

| Ndufb11 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 11 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 2.38 | 1.10 | 3.11 | |

| Ndufv1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein 1 | -1.14 | -0.97 | 1.79 | 1.12 | 7.58 | |

| Cpt1b | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1b, muscle | 0.16 | -1.42 | 1.64 | -2.99 | 2.79 | |

| Ndufa9 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A9 | -1.26 | -2.64 | -0.32 | -2.60 | 1.93 | |

| Cyc1 | Cytochrome c-1 | -1.05 | -1.67 | 0.93 | -1.54 | 3.95 | |

| Ndufa11 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A11 | -0.36 | -1.58 | -0.29 | -2.34 | 1.04 | |

| Cox5a | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit Va | -1.58 | 1.17 | -2.53 | 6.69 | -1.94 | |

| Mpc1 | mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 | -1.05 | -0.92 | -1.71 | 1.10 | -1.58 | |

| Ndufc2 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit C2 | 0.38 | -0.30 | -1.52 | -1.61 | -3.75 | |

| The most controlled genes in the entire transcriptome in CN and IHF mice | RCS-FC | ||||||

| Tmem186 | Transmembrane protein 186 | 5.19 | -0.10 | 0.70 | -39.13 | -22.50 | |

| Cd164 | CD164 antigen | 0.09 | 5.28 | 0.57 | 36.56 | 1.40 | |

| Atp13a2 | ATPase type 13A2 | 0.66 | -0.03 | 4.55 | -1.61 | 14.82 | |

| The least controlled genes in the entire transcriptome in CN and IHF mice | RCS-FC | ||||||

| Gmcl1 | Germ cell-less homolog 1 (Drosophila) | -2.40 | -0.33 | -2.50 | 4.19 | -1.07 | |

| Idh3g | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 (NAD+), gamma | -1.10 | -2.83 | 0.80 | -3.32 | 3.72 | |

| Tsc22d4 | TSC22 domain family, member 4 | 0.98 | 0.25 | -2.91 | -1.67 | -14.86 | |

| MOST PROMINENT MITO GENES IN CCC MICE | GCH | GCH-FC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENE | Description | IN | IT | IN | IT | |||

| Cox4i2 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4I2 | 13.20 | 17.02 | 8.74 | 11.27 | |||

| Ndufb7 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 7 | 11.73 | 17.82 | 14.09 | 21.42 | |||

| Cox6b1 | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIb polypeptide 1 | 11.48 | 17.52 | 4.81 | 7.34 | |||

| Uqcrh | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase hinge protein | 11.21 | 16.07 | 4.66 | 6.67 | |||

| Ndufs4 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 4 | 11.00 | 12.23 | 4.66 | 5.18 | |||

| Ndufa7 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 7 | 7.48 | 19.80 | 1.42 | 3.77 | |||

| Ndufc1 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit C1 | 4.60 | 19.71 | -1.18 | 3.63 | |||

| Ndufa2 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 2 | 6.54 | 19.70 | 7.64 | 23.01 | |||

| Ndufa10 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex 10 | 9.54 | 19.57 | 1.71 | 3.52 | |||

| Uqcrb | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase binding protein | 9.95 | 19.55 | 2.44 | 4.80 | |||

| MOST PROMINENT MITO GENES IN IHF MICE | GCH | GCH-FC | ||||||

| Cox6b1 | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIb polypeptide 1 | 24.16 | 2.08 | 5.53 | -2.10 | |||

| Atp5f1e | ATP synthase F1 subunit epsilon | 9.01 | 2.00 | 3.70 | -1.22 | |||

| Atp5mc2 | ATP synthase membrane subunit c locus 2 | 5.13 | 1.12 | 1.88 | -2.44 | |||

| Ndufs5 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5 | 4.22 | 1.40 | 1.13 | -2.65 | |||

| Ndufa1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 1 | 4.21 | 3.60 | 1.38 | 1.18 | |||

| Ndufb11 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 11 | 3.01 | 6.39 | -1.90 | 1.12 | |||

| Ndufs4 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 4 | 0.80 | 5.92 | -9.72 | -1.31 | |||

| Ndufv1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein 1 | 0.72 | 4.48 | -3.68 | 1.68 | |||

| Cyc1 | Cytochrome c-1 | 0.52 | 4.26 | -4.69 | 1.73 | |||

| Ndufa1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 1 | 4.21 | 3.60 | 1.38 | 1.18 | |||

| MOST PROMINENT MITO GENES IN HEALTHY MICE | GCH | CCC | IHF | |||||

| Ndufb10 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 10 | 13.07 | 7.21 | 2.26 | ||||

| Ndufa10 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex 10 | 9.79 | 9.54 | 1.01 | ||||

| Uqcrb | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase binding protein | 9.69 | 9.95 | 2.91 | ||||

| Ndufaf1 | NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex assembly factor 1 | 8.14 | 8.31 | 1.67 | ||||

| Ndufs4 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 4 | 7.76 | 11.00 | 0.80 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).