Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

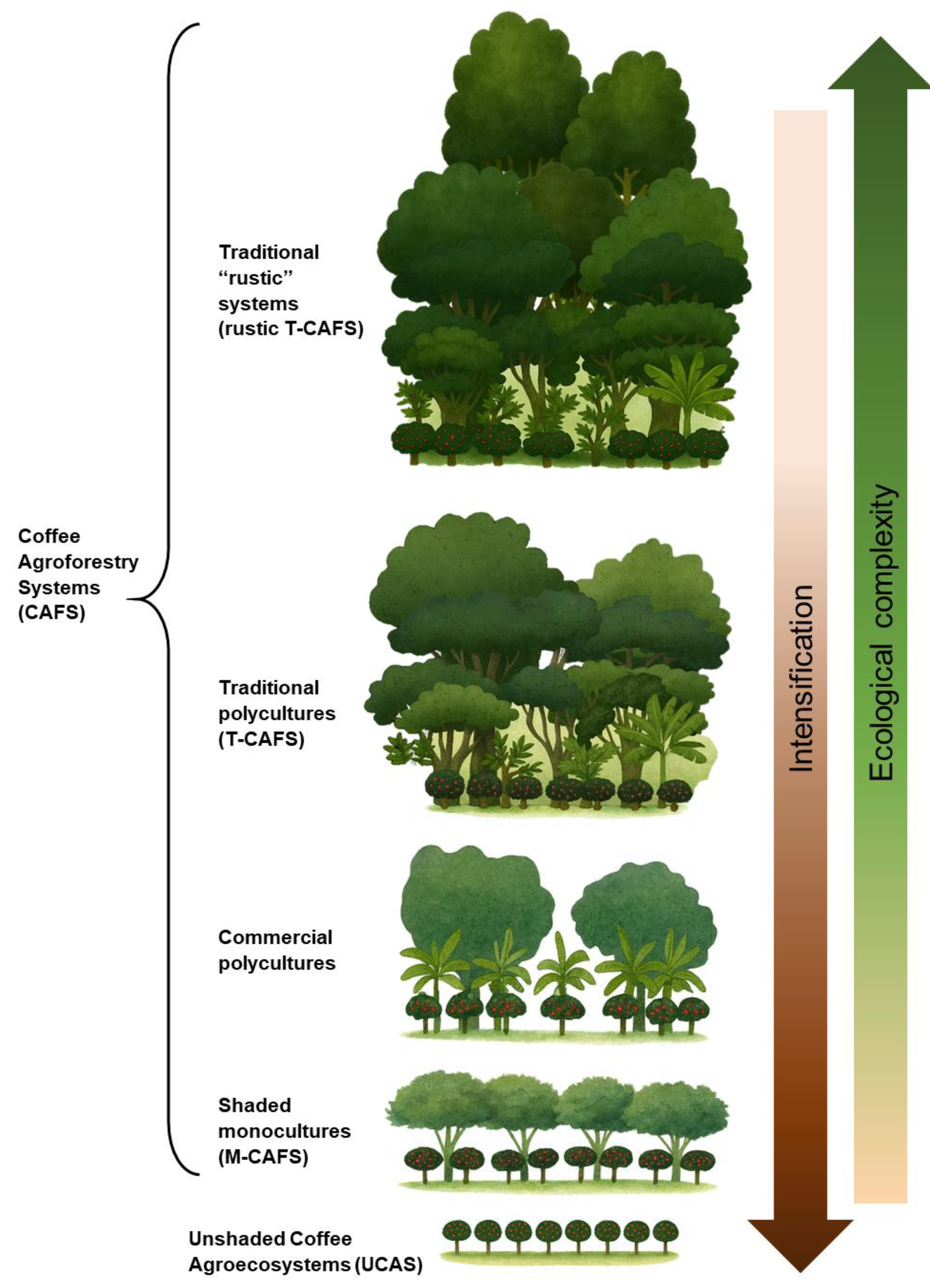

- Multistory agroforestry with diverse shade trees.

- High biodiversity and ecological complexity, supporting key ecosystem functions.

- Native Arabica varieties.

- Minimal external inputs such as agrochemicals.

- Small-scale farms (<10he), often family-owned and operated.

- Integration with local or indigenous knowledge and labor systems.

- High-density coffee monocultures, often with no or low-diversity canopy.

- Ecological simplification and reduced biodiversity.

- Use of Robusta or hybrid Arabica cultivars.

- Heavy reliance on agrochemicals.

- Large-scale operations (>10 ha), often corporate-owned.

- Seasonal wage labor under hierarchical management.

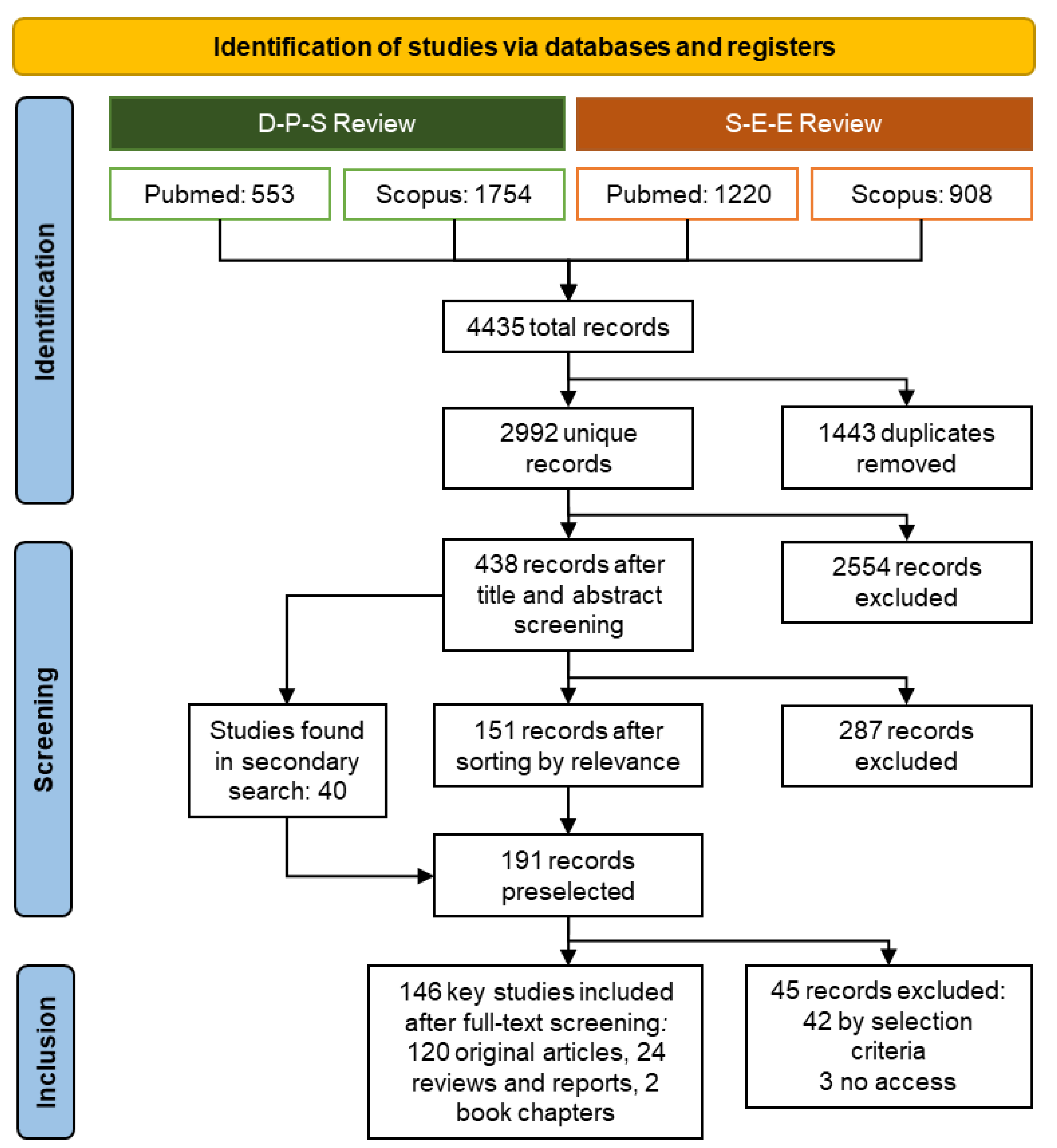

2. Methods

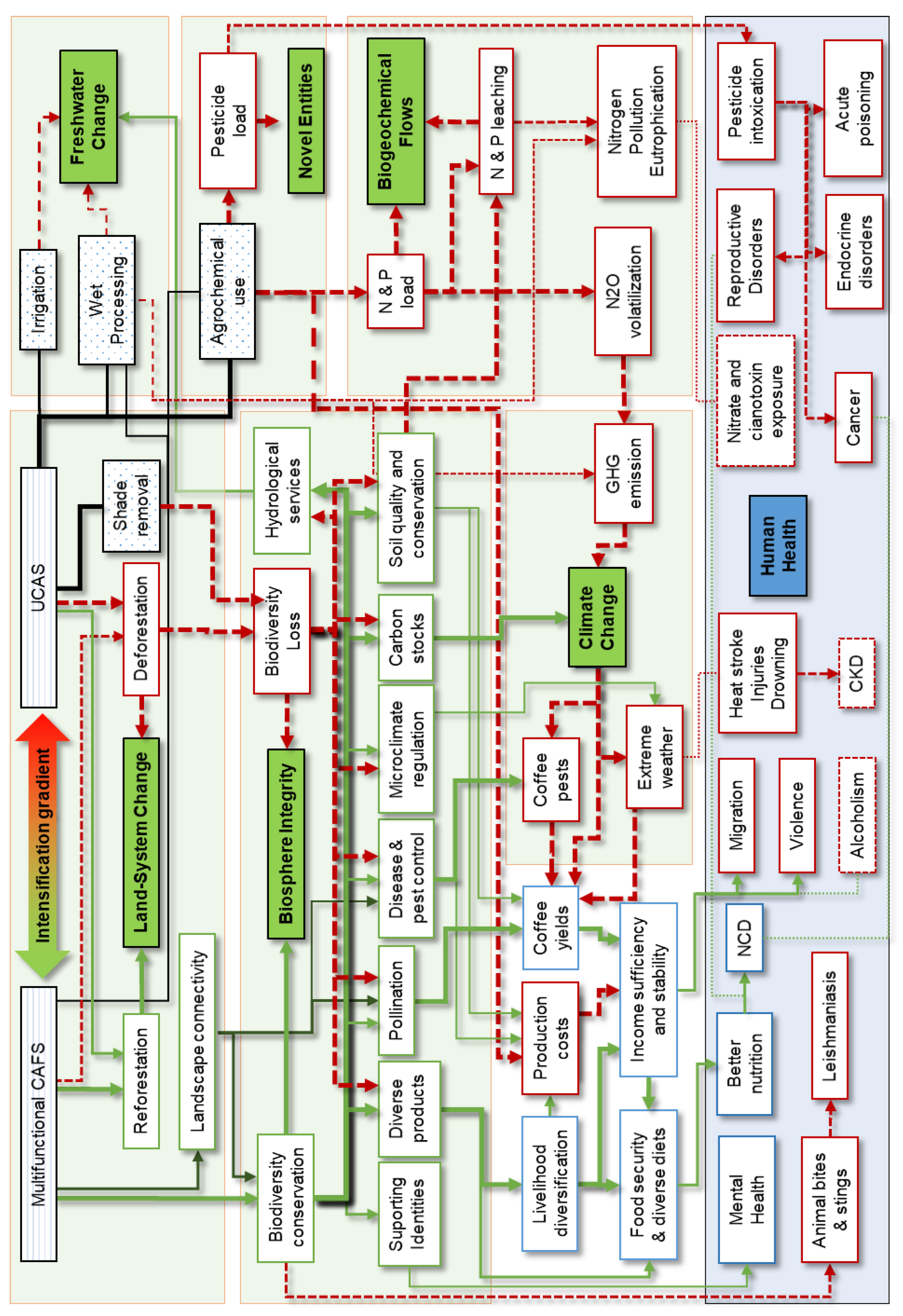

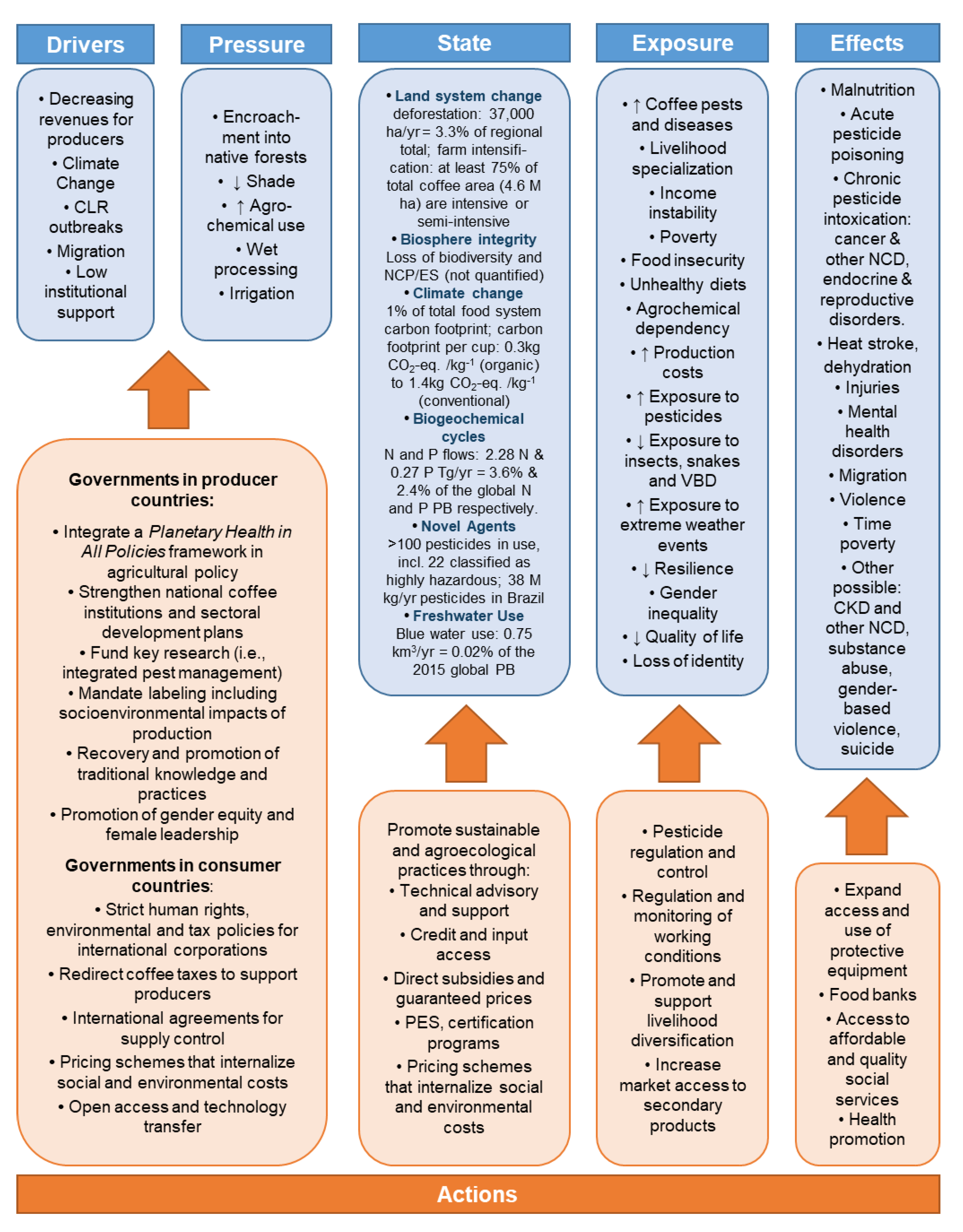

- D-P-S review: a review of the Drivers of CAS management practices and their transformation (Pressure), and their impacts of these on the six PB deemed most relevant in coffee farming (State): biosphere integrity, land-system change, climate change, biogeochemical flows, novel entities, and freshwater use.

- S-E-E review: a review of the impacts of the former on the ecosocial determinants of human health (Exposure) and health outcomes (Effect), particularly among coffee-growing communities and farmers.

3. Drivers of Transformation in Coffee Landscapes

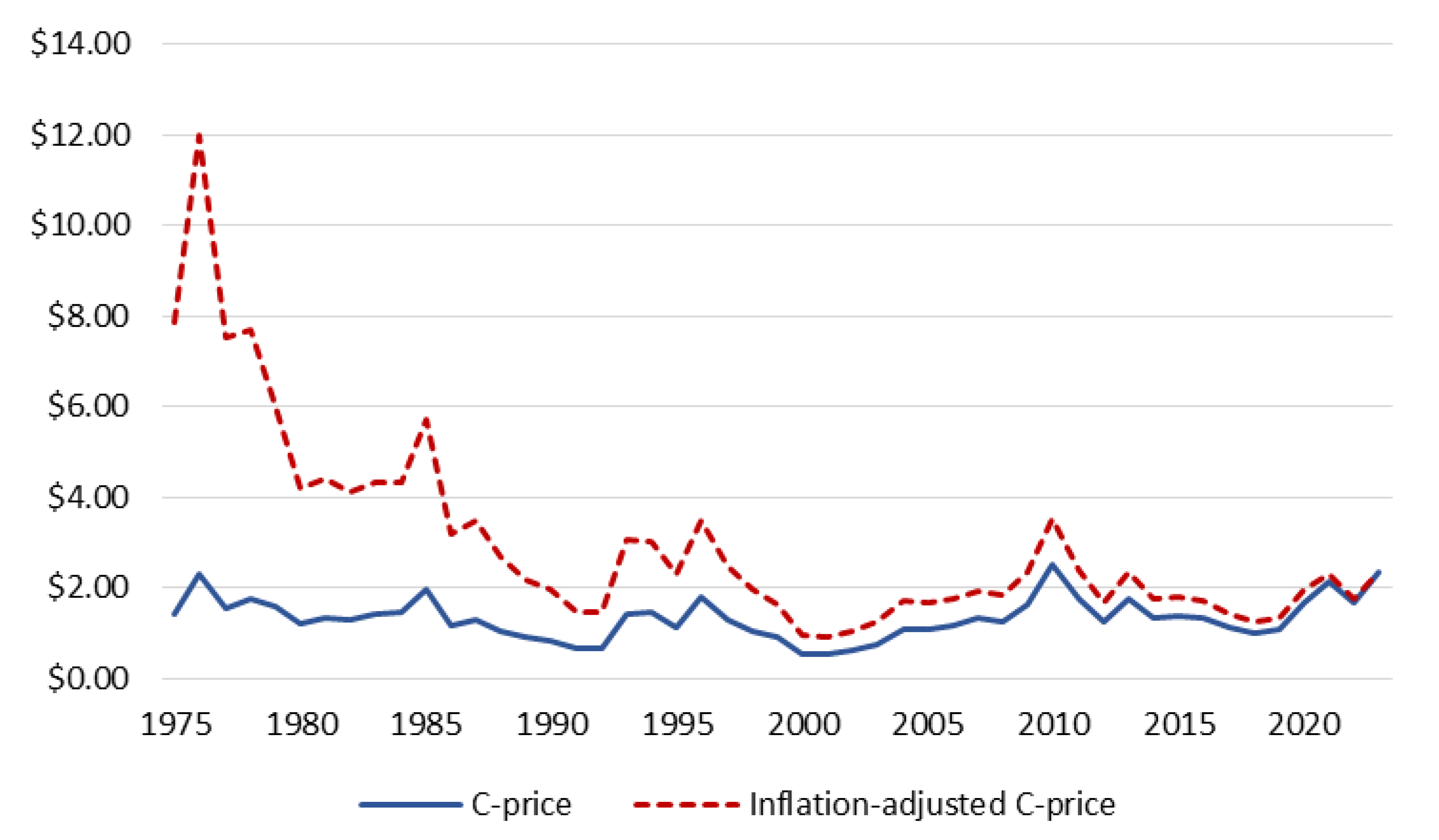

3.1. Decreasing and Volatile Revenues for Coffee Producers

- Box 1. Human Rights violations in Coffee Farming.

3.2. Climate Change

3.3. CLR Outbreaks

4. Coffee Farming’s Impacts on Planetary Boundaries

4.1. Biosphere Integrity

4.1.1. Impacts of CAS on Biodiversity Conservation

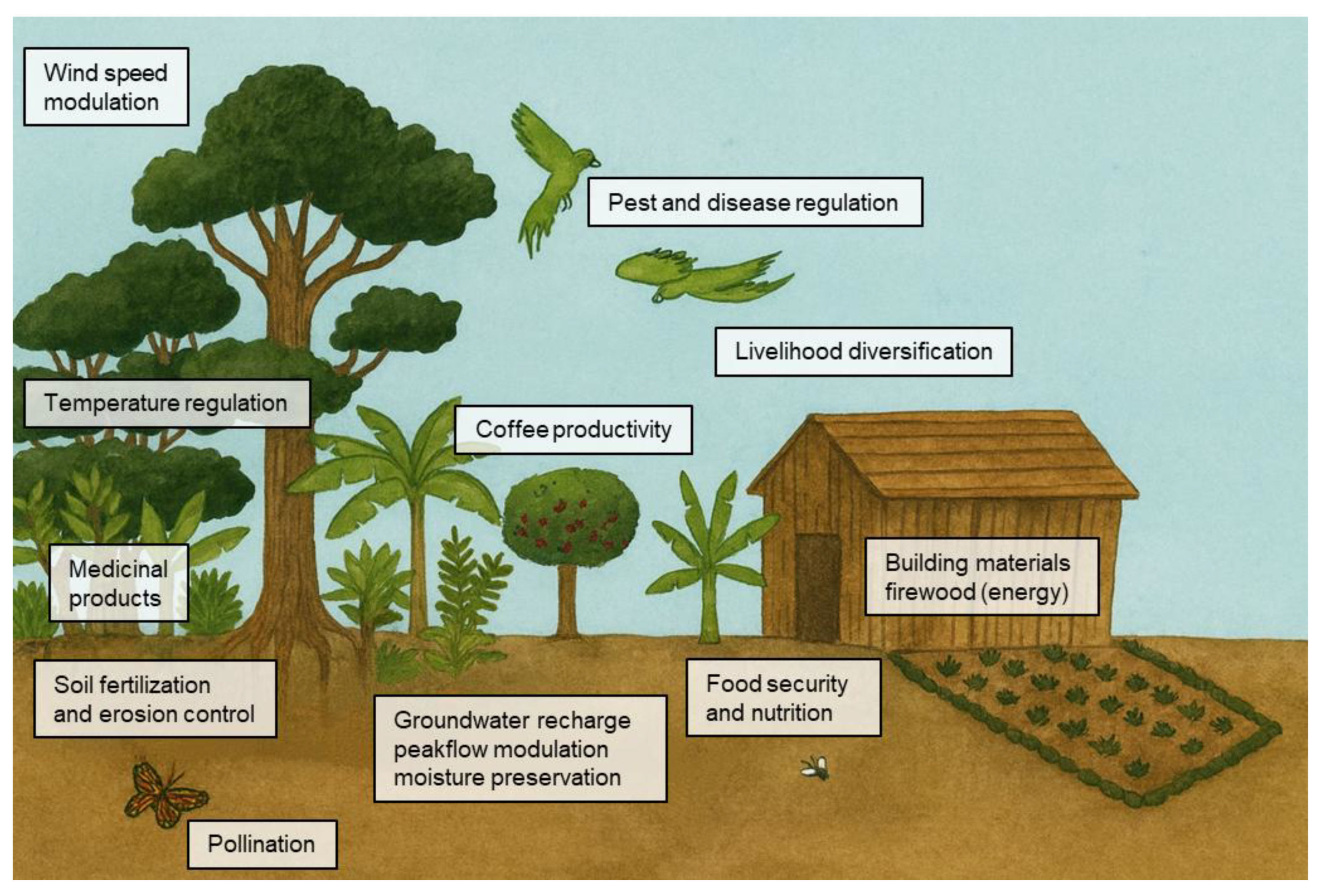

4.1.2. Impacts of CAS on NCP

Soil Health, Nutrient Cycling, and Erosion Control

Hydrological Services

Regulation of Microclimate and Extreme Weather

Pollination

Regulation of Detrimental Organisms

Coffee Productivity

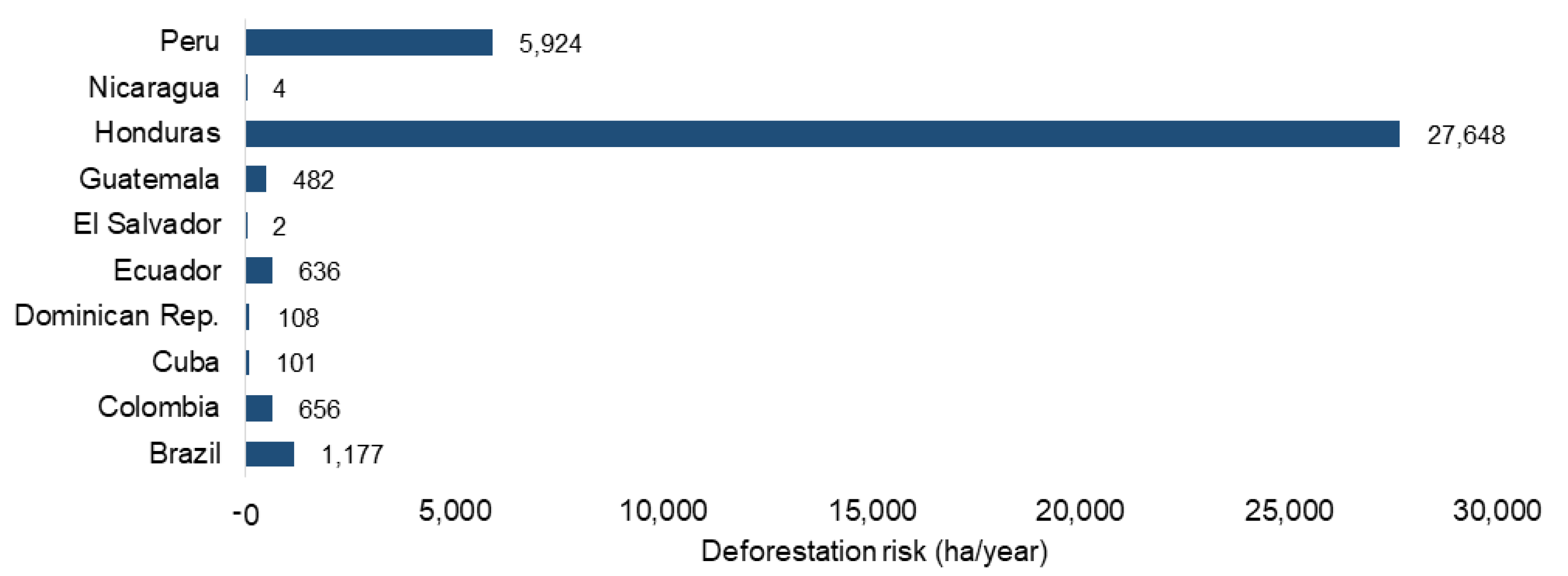

4.2. Land-System Change

4.3. Climate Change

4.4. Biogeochemical Flows

4.5. Freshwater Change

4.6. Novel Entities

5. Coffee Farming’s Impacts on Human Health and Its Ecosocial Determinants

5.1. Occupational Health Hazards, Exposure to Dangerous Fauna, and Leishmaniasis

5.2. Impacts on Ecosocial Determinants of Health

5.2.1. Livelihood Diversification and Income

5.2.2. Food Security and Nutrition

5.2.3. Migration

5.2.4. Peace and Security

5.2.5. Gender Equity

5.2.6. Identity, Quality of Life and Mental Health

6. Discussion

6.1. Human and Planetary Health Impacts of Coffee Farming

6.2. Equity and Identity in the CVC

6.3. Recommended Actions to Protect Planetary Health in Coffee Farming

- -

- Strengthening national coffee institutions and sectoral development plans, including funding mechanisms to support producers during crises.

- -

- Expanding farmer access to credit, land, CLR-resistant seed varieties, inputs, and technical assistance oriented to sustainable practices.

- -

- Providing financial incentives for agroecological production in the form of direct subsidies, payments for ecosystem services, guaranteed minimum prices, and market premiums.

- -

- Developing pricing schemes that internalize social and environmental costs, for instance through targeted taxation mechanisms.

- -

- Including information on the social and environmental impacts of production in product labeling.

- -

- Promoting a more rational and limited use of pesticides, banning highly hazardous pesticides, and enforcing restrictions.

- -

- Promoting integrated pest management prioritizing complementary alternatives such as biological control, agroforestry, and emerging genomic tools.

- -

- Establishing and enforcing minimum working conditions and safety standard, including provisions to ensure that all farmworkers have proper protective equipment.

- -

- Integrating gender perspectives in sectoral programs, promoting female leadership and specifically addressing time poverty.

- -

- Expanding healthcare, social security, and education services in coffee-growing regions, ensuring access for both farmers and seasonal workers.

- -

- Investing in infrastructure and local market access, including for secondary products.

- -

- Establishing mechanisms for an open an equitable access to technological innovations, such as genomic tools for pest control.

- -

- Shortening value chains by linking producers directly to urban consumers.

- -

- Promoting horizontal knowledge exchange and recovery of traditional management practices, protecting biocultural heritage, native seed diversity, and cultural traditions.

6.4. The DPSEEA Framework of Coffee Farming’s Impacts on Planetary Health

6.5. Strengths, Limitations, and Research Gaps

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acosta-Alba I, Boissy J, Chia E, Andrieu N (2020) Integrating diversity of smallholder coffee cropping systems in environmental analysis. Int J Life Cycle Assess 25:252–266. [CrossRef]

- Alexander B, Agudelo LA, Navarro JF, et al (2009) Relationship between coffee cultivation practices in Colombia and exposure to infection with Leishmania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 103:1263–1268. [CrossRef]

- Ali S, Ullah MI, Sajjad A, et al (2021) Environmental and Health Effects of Pesticide Residues. In: Inamuddin, Ahamed MI, Lichtfouse E (eds) Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 48: Pesticide Occurrence, Analysis and Remediation Vol. 2 Analysis. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 311–336.

- Anderzén J, Guzmán Luna A, Luna-González DV, et al (2020) Effects of on-farm diversification strategies on smallholder coffee farmer food security and income sufficiency in Chiapas, Mexico. Journal of Rural Studies 77:33–46. [CrossRef]

- Arellano C, Hernández C (2023) Carbon footprint and carbon storing capacity of arabica coffee plantations of Central America: A review. Coffee Sci 18. [CrossRef]

- Avelino J, Cristancho M, Georgiou S, et al (2015) The coffee rust crises in Colombia and Central America (2008–2013): impacts, plausible causes and proposed solutions. Food Sec 7:303–321. [CrossRef]

- Babbar LI, Zak DR (1995) Nitrogen loss from coffee agroecosystems in Costa Rica: Leaching and denitrification in the presence and absence of shade trees. Journal of Environmental Quality 24:227–233. [CrossRef]

- Bacon CM (2010) A spot of coffee in crisis: Nicaraguan smallholder cooperatives, fair trade networks, and gendered empowerment. Lat Am Perspect 37:50–71. [CrossRef]

- Bacon CM, Sundstrom WA, Flores Gómez ME, et al (2014) Explaining the “hungry farmer paradox”: Smallholders and fair trade cooperatives navigate seasonality and change in Nicaragua’s corn and coffee markets. Global Environ Change 25:133–149. [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Puente G, Galván-Manuel O, Pérez-Soto F, et al (2022) Price hedging for coffee, using the futures market. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 13:1147–1154. [CrossRef]

- Bass JOJ (2006) Forty years and more trees: Land cover change and coffee production in Honduras. Southeast Geogr 46:51–65. [CrossRef]

- Bedoya P. S, García R. A, Londoño F. AL, Restrepo C. B (2014) Determination of organochlorine pesticide residues In serum of coffee and banana growers in the departament of quindío by gc-μecd. Rev Colomb Quim 43:11–16. [CrossRef]

- Bedoya-Durán MJ, Jones HH, Malone KM, Branch LC (2023) Continuous forest at higher elevation plays a key role in maintaining bird and mammal diversity across an Andean coffee-growing landscape. Anim Conserv 26:714–728. [CrossRef]

- Bermeo S, Leblang D (2021) Climate, violence, and Honduran migration to the United States. Brookings. Brookings.

- Bilen C, El Chami D, Mereu V, et al (2023) A Systematic Review on the Impacts of Climate Change on Coffee Agrosystems. Plants 12. [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi C, Carrasquilla G, Volpi S, et al (2009) Biomonitoring of genotoxic risk in agricultural workers from five Colombian regions: Association to occupational exposure to glyphosate. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A Curr Iss 72:986–997. [CrossRef]

- Braunschweig T, Kohli A, Lang S (2019) Agricultural commodity traders in Switzerland: Benefitting from misery. Public Eye Report.

- Bremer L, al. (2021) Chapter 5 - Nature-based solutions, sustainable development, and equity. In: Matthews, John H., Cassin, Jan, Lopez-Gunn, Elena, editors. Nature-based Solutions and Water Security. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands ; Oxford, England ; Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp 81–105.

- Caldwell AC, Silva LCF, Da Silva CC, Ouverney CC (2015) Prokaryotic diversity in the rhizosphere of organic, intensive, and transitional coffee farms in Brazil. PLoS ONE 10. [CrossRef]

- Calvillo-Arriola AE, Sotelo-Navarro PX (2024) A step towards sustainability: life cycle assessment of coffee produced in the indigenous community of Ocotepec, Chiapas, Mexico. Discov Sustain 5. [CrossRef]

- Campos A (2016) Certified coffee, rightless workers. Repórter Brasil - RPBR.

- Capa D, Pérez-Esteban J, Masaguer A (2015) Unsustainability of recommended fertilization rates for coffee monoculture due to high N2O emissions. Agron Sustainable Dev 35:1551–1559. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Espinosa K, Avitia M, Barrón-Sandoval A, et al (2022) Land-Use Change and Management Intensification Is Associated with Shifts in Composition of Soil Microbial Communities and Their Functional Diversity in Coffee Agroecosystems. Microorg 10. [CrossRef]

- Cerda R, Avelino J, Harvey CA, et al (2020) Coffee agroforestry systems capable of reducing disease-induced yield and economic losses while providing multiple ecosystem services. Crop Prot 134. [CrossRef]

- Cerretelli S, Castellanos E, González-Mollinedo S, et al (2023) A scenario modelling approach to assess management impacts on soil erosion in coffee systems in Central America. Catena 228. [CrossRef]

- Chandler RB, King DI, Raudales R, et al (2013) A small-scale land-sparing approach to conserving biological diversity in tropical agricultural landscapes. Conserv Biol 27:785–795. [CrossRef]

- Chapagain AK, Hoekstra AY (2007) The water footprint of coffee and tea consumption in the Netherlands. Ecol Econ 64:109–118. [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Miguel G, Bonatti M, Ácevedo-Osorio Á, et al (2022) Agroecology as a grassroots approach for environmental peacebuilding Strengthening social cohesion and resilience in post-conflict settings with community-based natural resource management. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 31:36–45. [CrossRef]

- Chort I, Öktem B (2024) Agricultural shocks, coping policies and deforestation: Evidence from the coffee leaf rust epidemic in Mexico. Am J Agric Econ 106:1020–1057. [CrossRef]

- Coltri PP, Pinto HS, Gonçalves RRDV, et al (2019) Low levels of shade and climate change adaptation of Arabica coffee in southeastern Brazil. Heliyon 5. [CrossRef]

- Coltro L, Mourad AL, Oliveira PAPLV, et al (2006) Environmental profile of Brazilian green coffee. Int J Life Cycle Assess 11:16–21. [CrossRef]

- Coltro L, Tavares MP, Sturaro KBFS (2024) Life cycle assessment of conventional and organic Arabica coffees: from farm to pack. International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment. [CrossRef]

- Conti CL, Barbosa WM, Simão JBP, Álvares-da-Silva AM (2018) Pesticide exposure, tobacco use, poor self-perceived health and presence of chronic disease are determinants of depressive symptoms among coffee growers from Southeast Brazil. Psychiatry Res 260:187–192. [CrossRef]

- Cordes KY, Sagan M, Kennedy S (2021) Responsible Coffee Sourcing: Towards a Living Income for Producers.

- Craves J (2006) Pesticides used on coffee farms. In: Coffee & conservation. https://www.coffeehabitat.com/2006/12/pesticides_used_2/. Accessed 5 Aug 2024. Available online:.

- Davidson S (2004) Shade Coffee Agro-Ecosystems in Mexico: A Synopsis of the Environmental Services and Socio-Economic Considerations. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 21:81–95. [CrossRef]

- De Beenhouwer M, Aerts R, Honnay O (2013) A global meta-analysis of the biodiversity and ecosystem service benefits of coffee and cacao agroforestry. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 175:1–7. [CrossRef]

- de Jesús Crespo R, Douthat T, Pringle C (2020) Stream friendly coffee: evaluating the impact of coffee farming on high-elevation streams of the Tarrazú coffee region of Costa Rica. Hydrobiologia 847:1903–1923. [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz VT, Azevedo MM, da Silva Quadros IP, et al (2018) Environmental risk assessment for sustainable pesticide use in coffee production. J Contam Hydrol 18–27. [CrossRef]

- Devoney M (2022) How much of the final price of a cup of coffee do farmers receive? In: Perfect Daily Grind. https://perfectdailygrind.com/?p=99315. Accessed 1 Aug 2024.

- Dube O, Vargas JF (2013) Commodity price shocks and civil conflict: Evidence from Colombia. Rev Econ Stud 80:1384–1421. [CrossRef]

- Dupre SI, Harvey CA, Holland MB (2022) The impact of coffee leaf rust on migration by smallholder coffee farmers in Guatemala. World Dev 156. [CrossRef]

- ECLAC (2021) ECLAC Statistical Briefings.

- Escobar-Ocampo MC, Castillo-Santiago MÁ, Ochoa-Gaona S, et al (2023) Drivers of Land-Use Change in Agroforestry Landscapes of Southern Mexico. Hum Ecol 51:409–422. [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Muñoz C, Madrid-Casaca H, Salazar-Sepúlveda G, et al (2022) Musculoskeletal Symptoms and Assessment of Ergonomic Risk Factors on a Coffee Farm. Appl Sci 12. [CrossRef]

- European Coffee Federation (2022) The journey of the coffee bean.

- FAO (1997) State of the World’s Forests.

- Fernandez M, Méndez VE (2019) Subsistence under the canopy: Agrobiodiversity’s contributions to food and nutrition security amongst coffee communities in Chiapas, Mexico. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 43:579–601. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2024) Markets and trade: Coffee. https://www.fao.org/markets-and-trade/commodities-overview/beverages/coffee/en.

- Fromm I (2023) Climate change impacts, food insecurity and migration: An analysis of the current crisis in Honduras. Migr and Diasporas: Struggl Between Incl and Exclusion 137–149. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel-Hernández L, Barradas VL (2024) Panorama of Coffee Cultivation in the Central Zone of Veracruz State, Mexico: Identification of Main Stressors and Challenges to Face. Sustainability 16. [CrossRef]

- García Ríos A, Martínez AS, Londoño ÁL, et al (2020) Determination of organochlorine and organophosphorus residues in surface waters from the coffee zone in Quindío, Colombia. J Environ Sci Health Part B Pestic Food Contamin Agric Wastes 55:968–973. [CrossRef]

- Gasperín-García EM, Platas-Rosado DE, Zetina-Córdoba P, et al (2023) Quality of life of coffee growers in the high mountains of Veracruz, Mexico. Agron Mesoam 34. [CrossRef]

- Gomez J, Alburqueque G, Ramos E, Raymundo C (2020) An Order Fulfillment Model Based on Lean Supply Chain: Coffee’s Case Study in Cusco, Peru. Adv Intell Sys Comput 1026:922–928. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Delgado F, Roupsard O, Le Maire G, et al (2011) Modelling the hydrological behaviour of a coffee agroforestry basin in Costa Rica. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 15:369–392. [CrossRef]

- González Álvarez A (2017) La Comunidad Maseual en la Tosepan y la revitalización de las lenguas originarias; el proyecto de la Maseualpedia. La Jornada del campo.

- González MA, Dennis RJ, Devia JH, et al (2013) Risk factors for cardiovascular and chronic diseases in a coffee-growing population. Rev Salud Publica 14:390–401.

- Gresser C, Tickell S (2002) Mugged: Poverty in your coffee cup. Oxfam.

- Griffith D, Zamudio Grave P, Cortés Viveros R, Cabrera Cabrera J (2017) Losing Labor: Coffee, Migration, and Economic Change in Veracruz, Mexico. Cult Agric Food Environ 39:35–42. [CrossRef]

- Hajian-Forooshani Z, Salinas ISR, Jiménez-Soto E, et al (2016) Impact of regionally distinct agroecosystem communities on the potential for autonomous control of the coffee leaf rust. Environ Entomol 45:1521–1526. [CrossRef]

- Hansson E, Mansourian A, Farnaghi M, et al (2021) An ecological study of chronic kidney disease in five Mesoamerican countries: associations with crop and heat. BMC Public Health 21:840. [CrossRef]

- Harvey CA, Pritts AA, Zwetsloot MJ, et al (2021) Transformation of coffee-growing landscapes across Latin America. A review. Agron Sustain Dev 41:62. [CrossRef]

- Harvey CA, Saborio-Rodríguez M, Martinez-Rodríguez MR, et al (2018) Climate change impacts and adaptation among smallholder farmers in Central America. Agric Food Secur 7. [CrossRef]

- Hausermann H (2014) Maintaining the Coffee Canopy: Understanding Change and Continuity in Central Veracruz. Hum Ecol 42:381–394. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Castillo RA (2001) Histories and Stories from Chiapas: Border Identities in Southern Mexico., 1st edn. University of Texas Press.

- Hicks P (2018) The Scandal of the C-Price. In: Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine. https://dailycoffeenews.com/2018/09/13/the-scandal-of-the-c-price/. Accessed 31 Jul 2024.

- Hutter H-P, Khan AW, Lemmerer K, et al (2018a) Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of pesticide exposure in male coffee farmworkers of the Jarabacoa Region, Dominican Republic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15. [CrossRef]

- Hutter H-P, Kundi M, Lemmerer K, et al (2018b) Subjective Symptoms of Male Workers Linked to Occupational Pesticide Exposure on Coffee Plantations in the Jarabacoa Region, Dominican Republic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15:2099. [CrossRef]

- International Coffee Council (2019) Futures markets: the role of non-commercial traders.

- International Coffee Organization (ICO) (2020) The Value of Coffee. Sustainability, Inclusiveness, and Resilience of the Coffee Global Value Chain.

- International Coffee Organization (ICO) (2011) Rules on statistics statistical reports.

- IPBES (2017) Update on the Classification of Nature’s Contributions to People by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

- Irizarry AD, Collazo JA, Vandermeer J, Perfecto I (2021) Coffee plantations, hurricanes and avian resiliency: insights from occupancy, and local colonization and extinction rates in Puerto Rico. Glob Ecol Conserv 27. [CrossRef]

- Jha S, Bacon C, Philpott S, et al (2014) Shade coffee: update on a disappearing refuge for biodiversity. Bioscience 64:416–428. [CrossRef]

- Jha S, Vandermeer JH (2010) Impacts of coffee agroforestry management on tropical bee communities. Biol Conserv 143:1423–1431. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Soto E (2021) The political ecology of shaded coffee plantations: conservation narratives and the everyday-lived-experience of farmworkers. The Journal of Peasant Studies 48:1284–1303. [CrossRef]

- Juárez-López BM, Velázquez-Rosas N, López-Binnqüist C (2017) Tree Diversity and Uses in Coffee Plantations of a Mixe Community in Oaxaca, Mexico. J Ethnobiology 37:765–778. [CrossRef]

- Karp DS, Mendenhall CD, Sandí RF, et al (2013) Forest bolsters bird abundance, pest control and coffee yield. Ecol Lett 16:1339–1347. [CrossRef]

- Klein N (2008) The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism.

- Koutouleas A, Collinge DB, Ræbild A (2023) Alternative plant protection strategies for tomorrow’s coffee. Plant Pathology 72:409–429. [CrossRef]

- Lalani B, Lanza G, Leiva B, et al (2024) Shade versus intensification: Trade-off or synergy for profitability in coffee agroforestry systems? Agric Syst 214. [CrossRef]

- Latini AO, Silva DP, Souza FML, et al (2020) Reconciling coffee productivity and natural vegetation conservation in an agroecosystem landscape in Brazil. J Nat Conserv 57. [CrossRef]

- Laux TS, Bert PJ, Ruiz GMB, et al (2012) Nicaragua revisited: Evidence of lower prevalence of chronic kidney disease in a high-altitude, coffee-growing village. J Nephrol 25:533–540. [CrossRef]

- Leal-Echeverri JC, Tobón C (2021) The water footprint of coffee production in Colombia. Rev Fac Nac Agron Medellín 74:9685–9697. [CrossRef]

- Libert Amico A, Ituarte-Lima C, Elmqvist T (2020) Learning from social–ecological crisis for legal resilience building: multi-scale dynamics in the coffee rust epidemic. Sustainability Science 15:485–501. [CrossRef]

- Libert-Amico A, Paz-Pellat F (2018) Del papel a la acción en la mitigación y adaptación al cambio climático: la roya del cafeto en Chiapas. Madera y bosques 24. [CrossRef]

- Lima J, Rossini S, Reimão R (2010) Sleep disorders and quality of life of harvesters rural labourers. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 68:372–376. [CrossRef]

- Lin BB (2007) Agroforestry management as an adaptive strategy against potential microclimate extremes in coffee agriculture. Agric For Meterol 144:85–94. [CrossRef]

- Londoño ÁL, Restrepo B, Sánchez JF, et al (2018) Pesticides and hypothyroidism in farmers of plantain and coffee growing areas in Quindío, Colombia. Rev Salud Publica 20:215–220. [CrossRef]

- López-Ramírez SM, Sáenz L, Mayer A, et al (2020) Land use change effects on catchment streamflow response in a humid tropical montane cloud forest region, central Veracruz, Mexico. Hydrol Processes 34:3555–3570. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ridaura S, Barba-Escoto L, Reyna C, et al (2019) Food security and agriculture in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. Food Secur 11:817–833. [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Baez SE, Domínguez-Haydar Y, Di Prima S, et al (2021) Shade-grown coffee in colombia benefits soil hydraulic conductivity. Sustainability 13. [CrossRef]

- Lyon S, Mutersbaugh T, Worthen H (2017) The triple burden: the impact of time poverty on women’s participation in coffee producer organizational governance in Mexico. Agric Hum Values 34:317–331. [CrossRef]

- Manson S, Nekaris KAI, Nijman V, Campera M (2024) Effect of shade on biodiversity within coffee farms: A meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment 914. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Salinas A, Chain-Guadarrama A, Aristizábal N, et al (2022) Interacting pest control and pollination services in coffee systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119:e2119959119. [CrossRef]

- Martins LD, Eugenio FC, Rodrigues WN, et al (2018) Carbon and water footprints in Brazilian coffee plantations - the spatial and temporal distribution. Emirates J Food Agric 30:482–487. [CrossRef]

- Mayorga I, Vargas de Mendonça JL, Hajian-Forooshani Z, et al (2022) Tradeoffs and synergies among ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, and food production in coffee agroforestry. Front For Glob Change 5. [CrossRef]

- McCune N, Luna Y, Vandermeer J, Perfect I (2021) Cuestiones Agrarias y Transformaciones Agroecológicas. In: Benítez M, Rivera-Núñez T, García-Barrios L (eds) Agroecología y Sistemas Complejos: Planteamientos epistémicos, casos de estudio y enfoques metodológicos, 1st edn. CopIt ArXives, México CDMX, pp 27–50.

- Méndez VE, Bacon CM, Olson M, et al (2010) Agrobiodiversity and Shade Coffee Smallholder Livelihoods: A Review and Synthesis of Ten Years of Research in Central America. The Professional Geographer 62:357–376. [CrossRef]

- Merhi A, Kordahi R, Hassan HF (2022) A review on the pesticides in coffee: Usage, health effects, detection, and mitigation. Front Public Health 10:1004570. [CrossRef]

- Mise YF, Lira-da-Silva RM, Carvalho FM (2016) Agriculture and snakebite in Bahia, Brazil – An ecological study. Ann Agric Environ Med 23:416–419. [CrossRef]

- Moguel P, Toledo VM (1999) Biodiversity Conservation in Traditional Coffee Systems of Mexico. Conservation Biology 13:11–21.

- Molina-Monteleón CM, Mauricio-Gutiérrez A, Castelán-Vega R, Tamariz-Flores JV (2024) Importance of Soil Health for Coffea spp. Cultivation from a Cooperative Society in Puebla, Mexico. Land 13. [CrossRef]

- Moreaux C, Meireles DAL, Sonne J, et al (2022) The value of biotic pollination and dense forest for fruit set of Arabica coffee: A global assessment. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 323:107680. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ramirez N, Bianchi FJJA, Manzano MR, Dicke M (2024) Ecology and management of the coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei): the potential of biological control. BioControl 69:199–214. [CrossRef]

- Morris KS, Mendez VE, Olson MB (2013) “Los meses flacos”: Seasonal food insecurity in a Salvadoran organic coffee cooperative. J Peasant Stud 40:423–446. [CrossRef]

- Moshammer H, Poteser M, Hutter H-P (2020) More pesticides—less children? Wien Klin Wochenschr 132:197–204. [CrossRef]

- Murillo-López BE, Castro AJ, Feijoo-Martínez A (2022) Nature’s Contributions to People Shape Sense of Place in the Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia. Agric 12. [CrossRef]

- Murrieta-Galindo R, González-Romero A, López-Barrera F, Parra-Olea G (2013) Coffee agrosystems: An important refuge for amphibians in central Veracruz, Mexico. Agrofor Syst 87:767–779. [CrossRef]

- Myhrvold N (2024) Coffee. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Nava-Tablada ME (2012) International migration and coffee production in Veracruz, Mexico. Migraciones Int 6:139–171.

- Nieto-Betancurt L, Mosquera-Becerra J, Fandiño-Losada A, Guava LAS (2024) Suicide and medical practices: Assessing the way of life among Colombian coffee-growing rural men in mental health care. Salud Colectiva 20. [CrossRef]

- Noriega-Puglisevich JA, Eckhardt KI (2024) Hydrological effects of the conversion of tropical montane forest to agricultural land in the central Andes of Peru. Environ Qual Manage. [CrossRef]

- Ocampo CB, Ferro MC, Cadena H, et al (2012) Environmental factors associated with American cutaneous leishmaniasis in a new Andean focus in Colombia. Trop Med Int Health 17:1309–1317. [CrossRef]

- Olguín EJ, Sánchez G, Mercado G (2004) Cleaner production and environmentally sound biotechnology for the prevention of upstream nutrient pollution in the Mexican coast of the Gulf of México. Ocean Coast Manage 47:641–670. [CrossRef]

- Padovan MP, Brook RM, Barrios M, et al (2018) Water loss by transpiration and soil evaporation in coffee shaded by Tabebuia rosea Bertol. and Simarouba glauca dc. compared to unshaded coffee in sub-optimal environmental conditions. Agric For Meterol 248:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Palomino-García LR, Vargas-Vásquez ML (2023) Identification of Hazards and Assessment of Risks associated with the Harvesting of Coffee. Puerto Rico Health Sci J 42:43–49.

- PAN International (2021) PAN International List of Highly Hazardous Pesticides.

- Panhuysen S, de Vries F (2023) Coffee Barometer 2023.

- Pascual-Mendoza S, Manzanero-Medina GI, Saynes-Vásquez A, Vásquez-Dávila MA (2020) Agroforestry systems of a Zapotec community in the northern Sierra of Oaxaca, Mexico. Bot Sci 98:128–144. [CrossRef]

- Pendrill F, Persson UM, Godar J, Kastner T (2019) Deforestation displaced: trade in forest-risk commodities and the prospects for a global forest transition. Environ Res Lett 14:055003. [CrossRef]

- Pendrill F, Persson UM, Kastner T (2020) Deforestation risk embodied in production and consumption of agricultural and forestry commodities 2005-2017.

- Peraza S, Wesseling C, Aragon A, et al (2012) Decreased kidney function among agricultural workers in El Salvador. Am J Kidney Dis 59:531–540. [CrossRef]

- Pereira Machado AC, Baronio GJ, Soares Novaes C, et al (2024) Optimizing coffee production: Increased floral visitation and bean quality at plantation edges with wild pollinators and natural vegetation. J Appl Ecol 61:465–475. [CrossRef]

- Perfecto I, Hajian-Forooshani Z, Iverson A, et al (2019a) Response of Coffee Farms to Hurricane Maria: Resistance and Resilience from an Extreme Climatic Event. Sci Rep 9. [CrossRef]

- Perfecto I, Jiménez-Soto ME, Vandermeer J (2019b) Coffee Landscapes Shaping the Anthropocene: Forced Simplification on a Complex Agroecological Landscape. Current Anthropology 60:S236–S250. [CrossRef]

- Perfecto I, Jiménez-Soto ME, Vandermeer J (2019c) Coffee landscapes shaping the anthropocene: Forced simplification on a complex agroecological landscape. Current Anthropology 60:S236–S250. [CrossRef]

- Perfecto I, Rice RA, Greenberg R, Van der Voort ME (1996) Shade Coffee: A Disappearing Refuge for Biodiversity: Shade coffee plantations can contain as much biodiversity as forest habitats. BioScience 46:598–608. [CrossRef]

- Pham Y, Reardon-Smith K, Mushtaq S, Cockfield G (2019) The impact of climate change and variability on coffee production: a systematic review. Climatic Change 156:609–630. [CrossRef]

- Philpott SM, Arendt WJ, Armbrecht I, et al (2008a) Biodiversity loss in Latin American coffee landscapes: Review of the evidence on ants, birds, and trees. Conserv Biol 22:1093–1105. [CrossRef]

- Philpott SM, Lin BB, Jha S, Brines SJ (2008b) A multi-scale assessment of hurricane impacts on agricultural landscapes based on land use and topographic features. Agric Ecosyst Environ 128:12–20. [CrossRef]

- Piato K, Subía C, Lefort F, et al (2022) No Reduction in Yield of Young Robusta Coffee When Grown under Shade Trees in Ecuadorian Amazonia. Life (Basel) 12. [CrossRef]

- Piato K, Subía C, Pico J, et al (2021) Organic Farming Practices and Shade Trees Reduce Pest Infestations in Robusta Coffee Systems in Amazonia. Life (Basel) 11. [CrossRef]

- Pineda JA, Piniero M, Ramírez A (2019) Coffee production and women’s empowerment in Colombia. Hum Organ 78:64–74. [CrossRef]

- Pronti A, Coccia M (2020) Agroecological and conventional agricultural systems: Comparative analysis of coffee farms in Brazil for sustainable development. Int J Sustainable Dev 23:223–248. [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Huatangari L, Fernandez-Zarate FH, Huaccha-Castillo AE (2022) Nitrous Oxide Emissions Generated in Coffee Cultivation: A Systematic Review. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology 21:1697–1703. [CrossRef]

- Rafferty JP (2023) Encyclopedia Britannica. In: Anthropocene Epoch. https://www.britannica.com/science/Anthropocene-Epoch. Accessed 15 Nov 2023.

- Reichert B, de Kok A, Pizzutti IR, et al (2018) Simultaneous determination of 117 pesticides and 30 mycotoxins in raw coffee, without clean-up, by LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. Anal Chim Acta 1004:40–50. [CrossRef]

- Reichman DR (2022) Putting climate-induced migration in context: the case of Honduran migration to the USA. Reg Environ Change 22:91. [CrossRef]

- Renard MC (2011) Chapter 5: Free trade of coffee, exodus of coffee workers: The case of the Southern Mexican border region of the state of Chiapas. Res Rural SociolDev 17:147–165. [CrossRef]

- Rettberg A (2010) Global markets, local conflict: Violence in the Colombian coffee region after the breakdown of the international coffee agreement. Lat Am Perspect 37:111–132. [CrossRef]

- Riah W, Laval K, Laroche-Ajzenberg E, et al (2014) Effects of pesticides on soil enzymes: a review. Environ Chem Lett 12:257–273. [CrossRef]

- Rice RA (2008) Agricultural intensification within agroforestry: The case of coffee and wood products. Agric Ecosyst Environ 128:212–218. [CrossRef]

- Rice RA (2011) Fruits from shade trees in coffee: How important are they? Agrofor Syst 83:41–49. [CrossRef]

- Richardson K, Steffen W, Lucht W, et al (2023) Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances 9:eadh2458. [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Orjuela JC, Falcón-Espitia N, Arias-Escobar A, Plazas-Cardona D (2024) Conserving biodiversity in coffee agroecosystems: Insights from a herpetofauna study in the Colombian Andes with sustainable management proposal. Perspect Ecol Conserv 22:196–204. [CrossRef]

- Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, et al (2009) A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461:472–475. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Camayo F, Lundy M, Borgemeister C, et al (2024) Local food system and household responses to external shocks: the case of sustainable coffee farmers and their cooperatives in Western Honduras during COVID-19. Front Sustain food Syst 8. [CrossRef]

- Rossi E, Montagnini F, de Melo Virginio Filho E (2011) Effects of management practices on coffee productivity and herbaceous species diversity in agroforestry systems in Costa Rica. In: Agroforestry as a Tool for Landscape Restoration. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., pp 113–132.

- Salvi RM, Lara DR, Ghisolfi ES, et al (2003) Neuropsychiatric evaluation in subjects chronically exposed to organophosphate pesticides. Toxicol Sci 72:267–271. [CrossRef]

- Sauvadet M, den Meersche KV, Allinne C, et al (2019) Shade trees have higher impact on soil nutrient availability and food web in organic than conventional coffee agroforestry. Sci Total Environ 649:1065–1074. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer JW, Adgate JL, Reynolds SJ, et al (2020) A Pilot Study to Assess Inhalation Exposures among Sugarcane Workers in Guatemala: Implications for Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Origin. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17:5708. [CrossRef]

- Scott M (2015) Climate & Coffee. In: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). http://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-and/climate-coffee. Accessed 20 Apr 2024.

- Soto-Pinto L, Colmenares SE, Kanter MB, et al (2022) Contributions of Agroforestry Systems to Food Provisioning of Peasant Households: Conflicts and Synergies in Chiapas, Mexico. Front Sustain Food Syst 5. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Pinto L, Romero-Alvarado Y, Caballero-Nieto J, Warnholtz GS (2001) Woody plant diversity and structure of shade-grown-coffee plantations in Northern Chiapas, Mexico. Rev Biol Trop 49:977–987.

- Souza HND, de Goede RGM, Brussaard L, et al (2012) Protective shade, tree diversity and soil properties in coffee agroforestry systems in the Atlantic Rainforest biome. Agric Ecosyst Environ 146:179–196. [CrossRef]

- Sporchia F, Taherzadeh O, Caro D (2021) Stimulating environmental degradation: A global study of resource use in cocoa, coffee, tea and tobacco supply chains. Curr Res Environ Sustain 3. [CrossRef]

- Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockström J, et al (2015) Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347:1259855. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855. [CrossRef]

- Sternhagen EC, Black KL, Hartmann EDL, et al (2020) Contrasting Patterns of Functional Diversity in Coffee Root Fungal Communities Associated with Organic and Conventionally Managed Fields. Appl Environ Microbiol 86. [CrossRef]

- Toledo VM, Moguel P (2012) Coffee and Sustainability : The Multiple Values of Traditional Shaded Coffee Coffee and Sustainability : The Multiple Values of Traditional Shaded Coffee. 0046. [CrossRef]

- Tully KL, Lawrence D, Scanlon TM (2012) More trees less loss: Nitrogen leaching losses decrease with increasing biomass in coffee agroforests. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 161:137–144. [CrossRef]

- Tully KL, Wood SA, Lawrence D (2013) Fertilizer type and species composition affect leachate nutrient concentrations in coffee agroecosystems. Agroforestry Systems 87:1083–1100. [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2023) Coffee: World Markets and Trade. https://fas.usda.gov/data/coffee-world-markets-and-trade. Accessed 20 Apr 2024.

- USAID (2021) Monitoring & Evaluation Support for Collaborative Learning and Adapting - Climate Change, Food Security, and Migration Briefer.

- Usva K, Sinkko T, Silvenius F, et al (2020) Carbon and water footprint of coffee consumed in Finland—life cycle assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 25:1976–1990. [CrossRef]

- Utrilla-Catalan R, Rodríguez-Rivero R, Narvaez V, et al (2022) Growing Inequality in the Coffee Global Value Chain: A Complex Network Assessment. Sustainability 14:672. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya C, Fitch G, Martinez GHD, et al (2023) Management practices and seasonality affect stingless bee colony growth, foraging activity, and pollen diet in coffee agroecosystems. Agric Ecosyst Environ 353. [CrossRef]

- Valencia V, García-Barrios L, Sterling EJ, et al (2018) Smallholder response to environmental change: Impacts of coffee leaf rust in a forest frontier in Mexico. Land Use Policy 79:463–474. [CrossRef]

- van Asselt J, Useche P (2022) Agricultural commercialization and nutrition; evidence from smallholder coffee farmers. World Dev 159. [CrossRef]

- van Rikxoort H, Schroth G, Läderach P, Rodríguez-Sánchez B (2014) Carbon footprints and carbon stocks reveal climate-friendly coffee production. Agron Sustain Dev 34:887–897. [CrossRef]

- VanDervort DR, López DL, Orantes CM, Rodríguez DS (2014) Spatial distribution of unspecified chronic kidney disease in El Salvador by crop area cultivated and ambient temperature. MEDICC Rev 16:31–38.

- Vázquez EF (2023) En Veracruz la lucha por el café justo cuesta la cárcel. Pie de Página.

- Vázquez G, Aké-Castillo JA, Favila ME (2011) Algal assemblages and their relationship with water quality in tropical Mexican streams with different land uses. Hydrobiologia 667:173–189. [CrossRef]

- Whitmee S, Haines A, Beyrer C, et al (2015) Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. The Lancet 386:1973–2028. [CrossRef]

- Zaro GC, Caramori PH, Wrege MS, et al (2022) Coffee crops adaptation to climate change in agroforestry systems with rubber trees in southern Brazil. Sci Agric 80. [CrossRef]

| 1 | NCP: the positive and negative contributions of living nature (i.e., the biosphere) to people’s quality of life (IPBES 2017). The conceptual antecedent of the NCP framework is the ecosystem services framework. |

| 2 | To convert between different coffee forms, a ratio of 5.4 : 2 : 1.25 : 1 (fresh cherry coffee : dry cherry coffee : parchment coffee : green coffee) is suggested (ICO 2011; Arellano and Hernández 2023). |

| 3 | 1 Tg = 1,000,000 tons. |

| 4 | Closed technologies include agrochemicals, farming machinery, genetically-modified seeds, software or other technologies impossible to manufacture, repair or modify by farmers themselves, thus increasing dependence. |

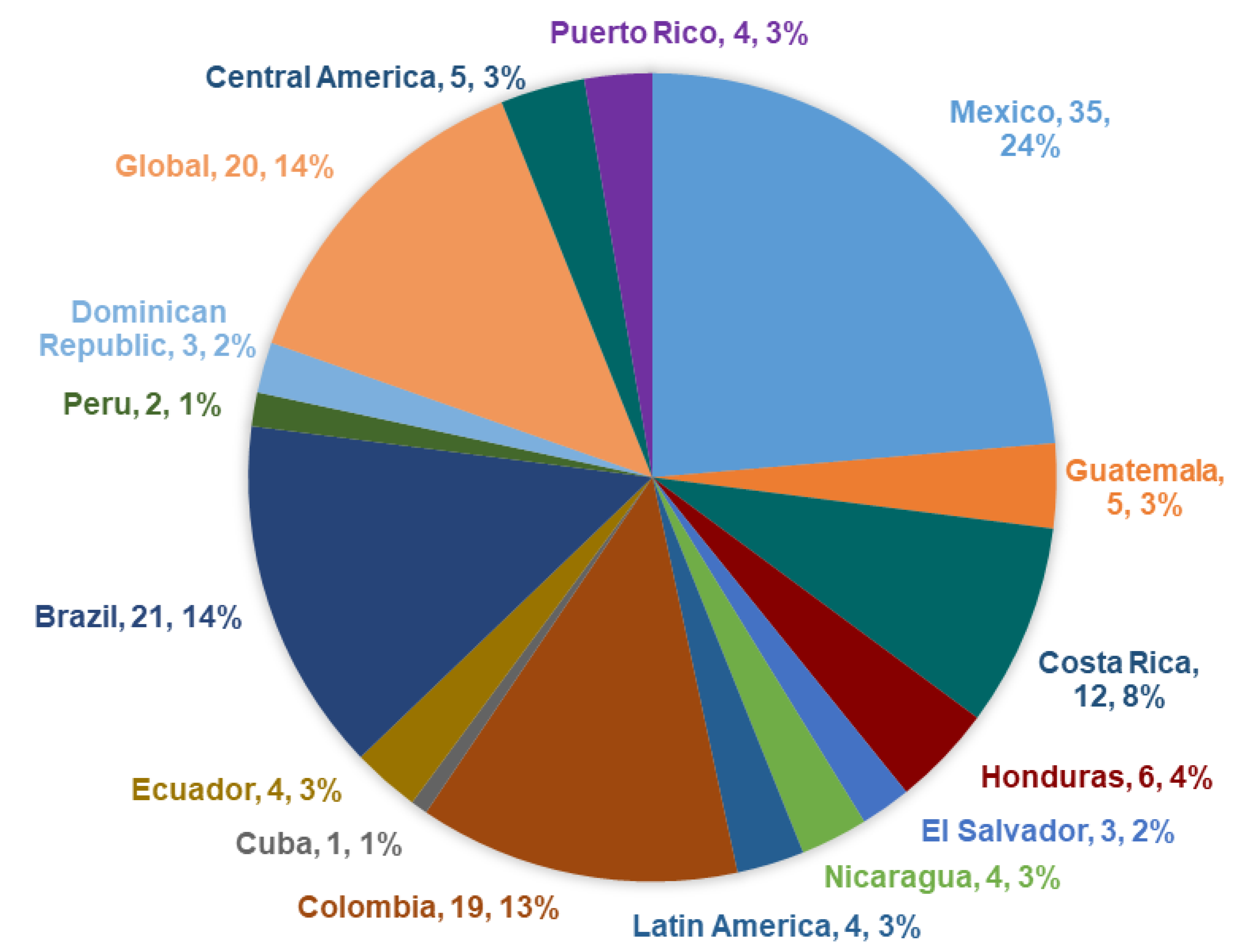

| Element | Keyword sample |

| CAS in Latin America | Coffee, system, growing, harvesting, farming, agroecosystem, agroforestry, farming, plantation, smallholder, shaded, sun, unshaded, monoculture, landscapes, etc. |

| Planetary Boundaries | Climate change, global warming, biodiversity, conservation, nitrogen, phosphorus, land use, land system, deforestation, pollution, freshwater, agrochemical, fertilizer, pesticide, etc. |

| Geographical delimitation | List of 18 Latin American countries |

| Human Health and its determinants | Health, exposure, infections, zoonosis, vector, food security, nutrition, income, poverty, migration, violence, mental, gender, intoxication, water security, extreme weather, bite, sting, etc. |

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria: |

|

| Land system | Soil (t C ha-1) | Biomass (t C ha-1) | Total (t C ha-1) |

| T-CAFS | 180 | 80 | 260 |

| M-CAFS | 130 | 43 | 173 |

| UCAS | 120 | 7 | 127 |

| Cornfield | 66 | 2 | 68 |

| Grassland | 80 | 8 | 88 |

| Pesticide | Human Health Hazards | Environmental Hazards |

| Chlorpyrifos | Reproductive toxicant (GHS) | Highly toxic to bees (EPA) |

| Copper II Hydroxide | Fatal if inhaled (GHS) | Very toxic to aquatic organisms and very persistant in water, soil or sediment (EPA) |

| Cypermethrin | Highly toxic to bees (EPA) | |

| Cyproconazole | Reproductive toxicant (GHS) | |

| Diazinon | Probable carcinogen (IARC) | Highly toxic to bees (EPA) |

| Disulfoton | Extremely high accute toxicity (WHO Ia) | |

| Diuron | Probable carcinogen (EPA) | |

| Endosulfan | Fatal if inhaled (GHS) | Persistent Organic Pollutant (Stockholm convention) |

| Epoxiconazole | Probable carcinogen (EPA, GHS), reproductive toxicant (GHS) | |

| Glyphosate | Probable carcinogen (IARC) | |

| Iprodione | Probable carcinogen (EPA) | |

| Malathion | Probable carcinogen (IARC) | Highly toxic to bees (EPA) |

| Mancozeb | Probable carcinogen (EPA, GHS), reproductive toxicant (GHS), endocrine disruptor (EU) | |

| Methyl Parathion | Extremely high accute toxicity (WHO Ia), fatal if inhaled (GHS) | Very toxic to aquatic organisms (EPA) |

| Methomyl | High acute toxicity (WHO 1b) | Highly toxic to bees (EPA) |

| Paraquat Dichloride | Fatal if inhaled (GHS) | |

| Pendimethalin | Very bioaccumulative, very persistant in water, soils or sediments (EPA) | |

| Permethrin | Probable carcinogen (EPA) | Highly toxic to bees (EPA) |

| Simazine | Probable carcinogen (GHS), probable reproductive toxicant (GHS) | |

| Thiamethoxam | Highly toxic to bees (EPA) | |

| Triadimenol | Reproductive toxicant (GHS) | |

| Triazophos | High acute toxicity (WHO 1b) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).