Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methodology

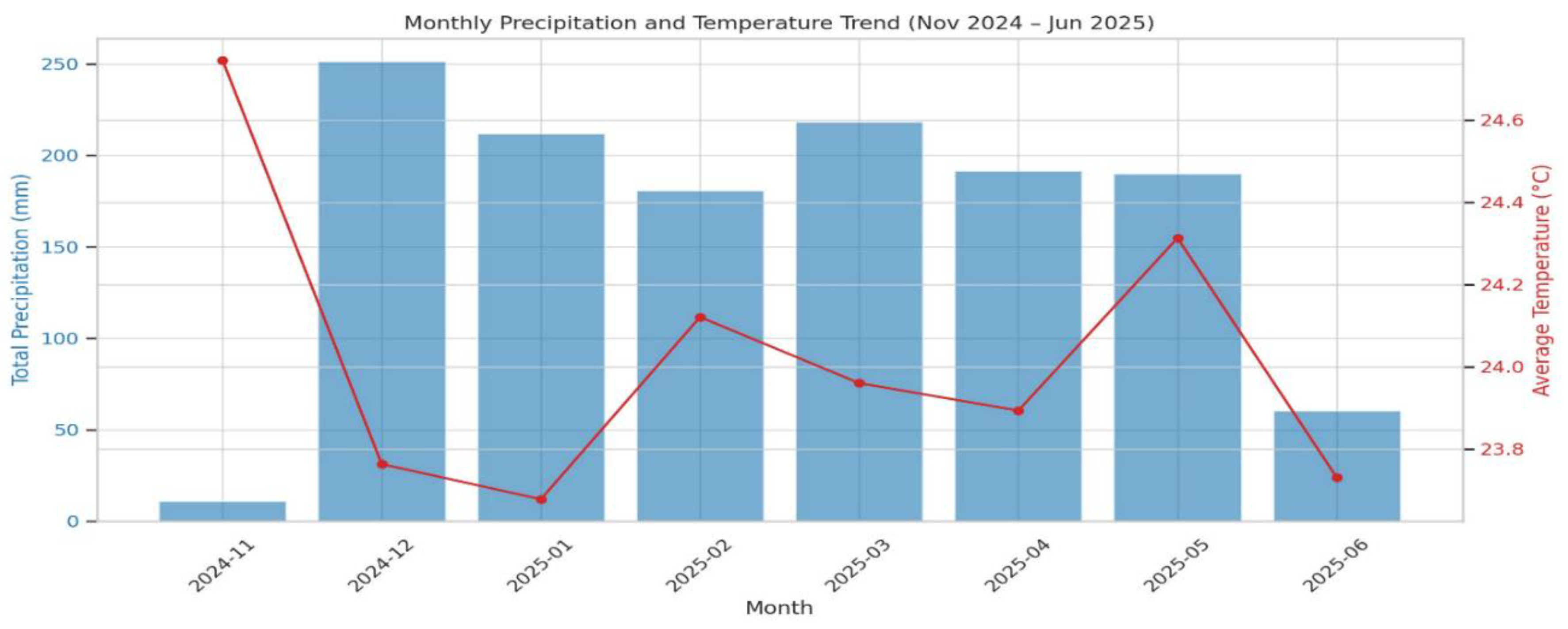

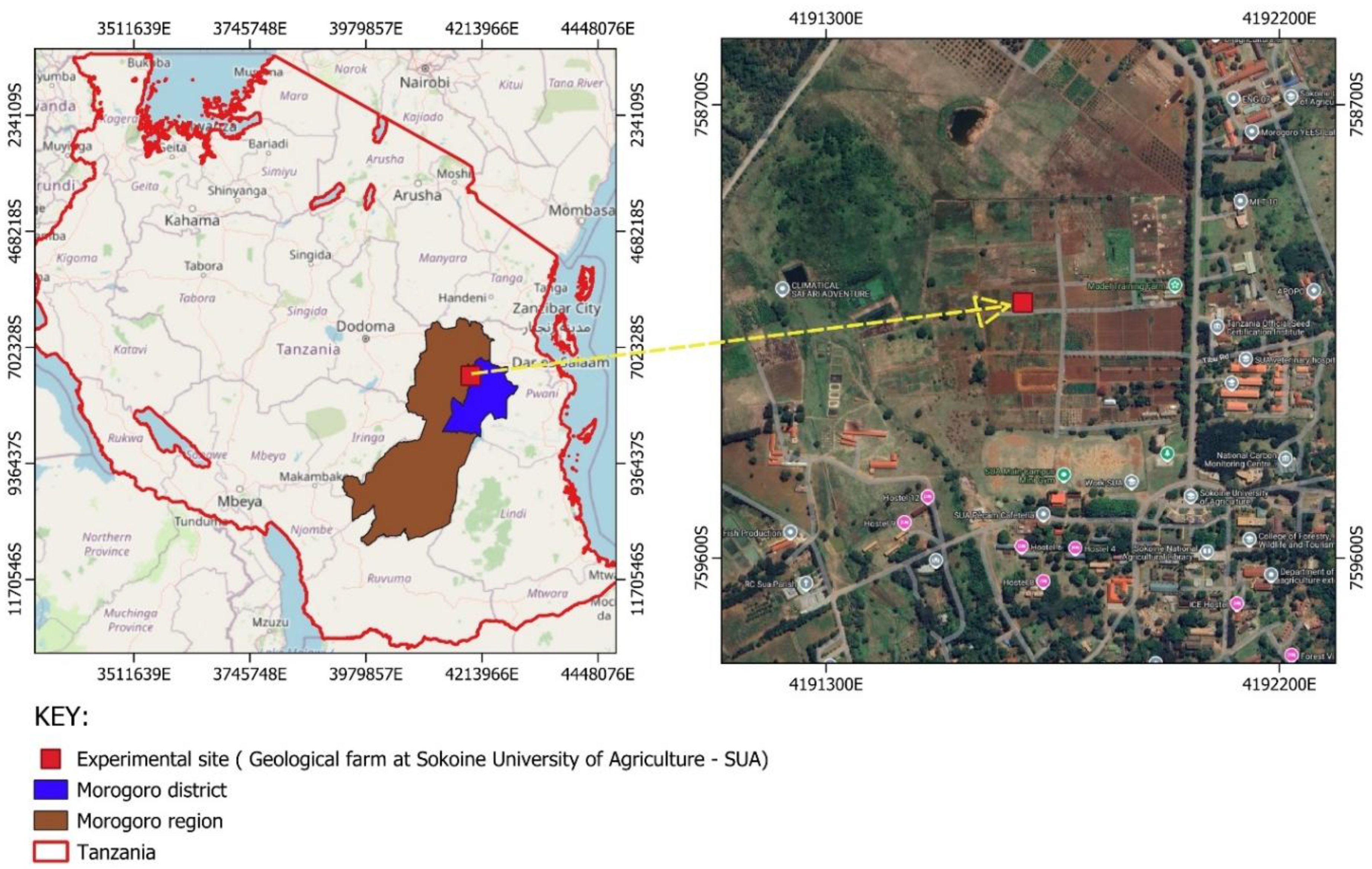

2.1. Location and Climatic Condition of the Study Area

2.2. Soil Sampling, Processing and Laboratory Procedures

2.3. Experimental Layout and Treatments Application

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Growth

2.4.2. Biomass and Yield Parameters

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fertility Status of the Experimental Site

3.2. Growth Performance of Chinese cabbage under Different Fertilizer Treatments

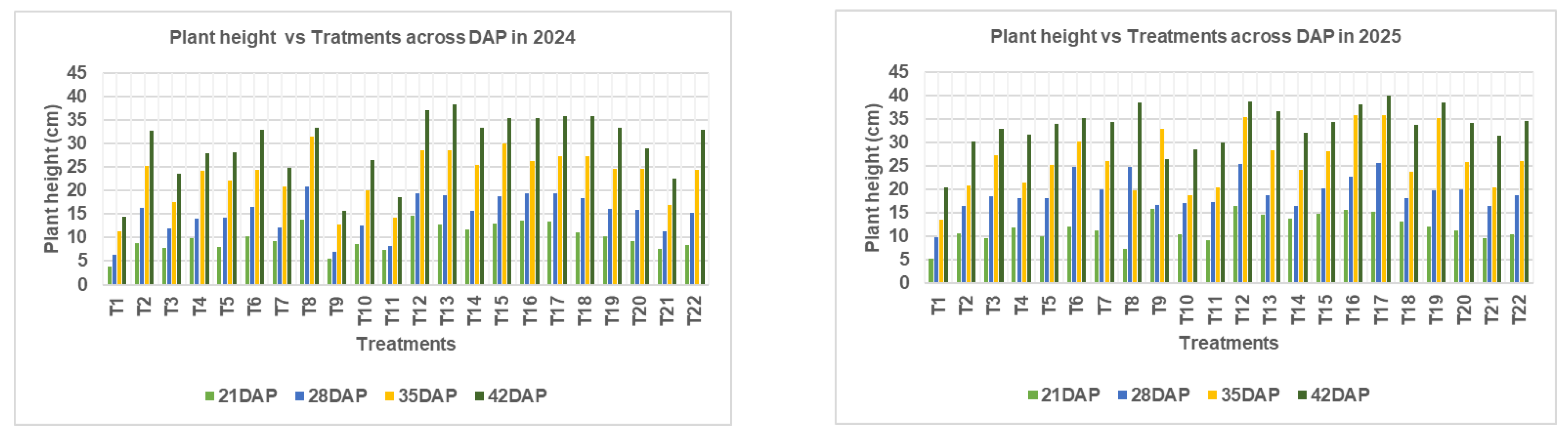

3.2.1. Plant Height Response to Fertilizer Treatments Across Seasons

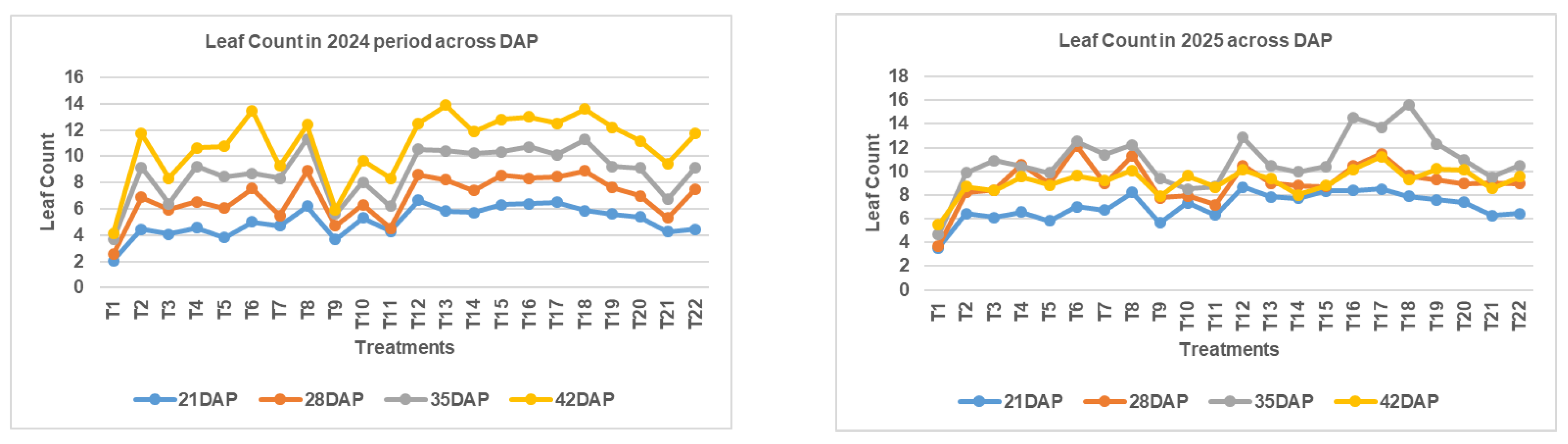

3.3. Leaf Count Response to NPK Fertilizer Application

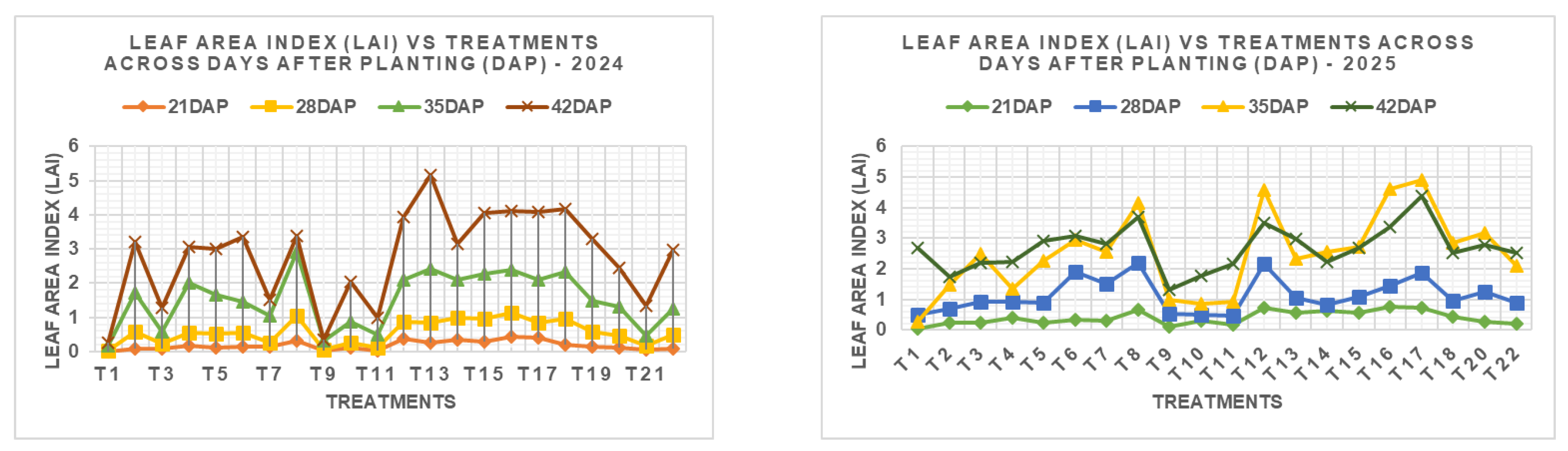

3.4. Effect of NPK Fertilizer Rates on Leaf Area Index (LAI)

3.5. Moisture and Dry Matter Accumulation Trends of Chinese Cabbage

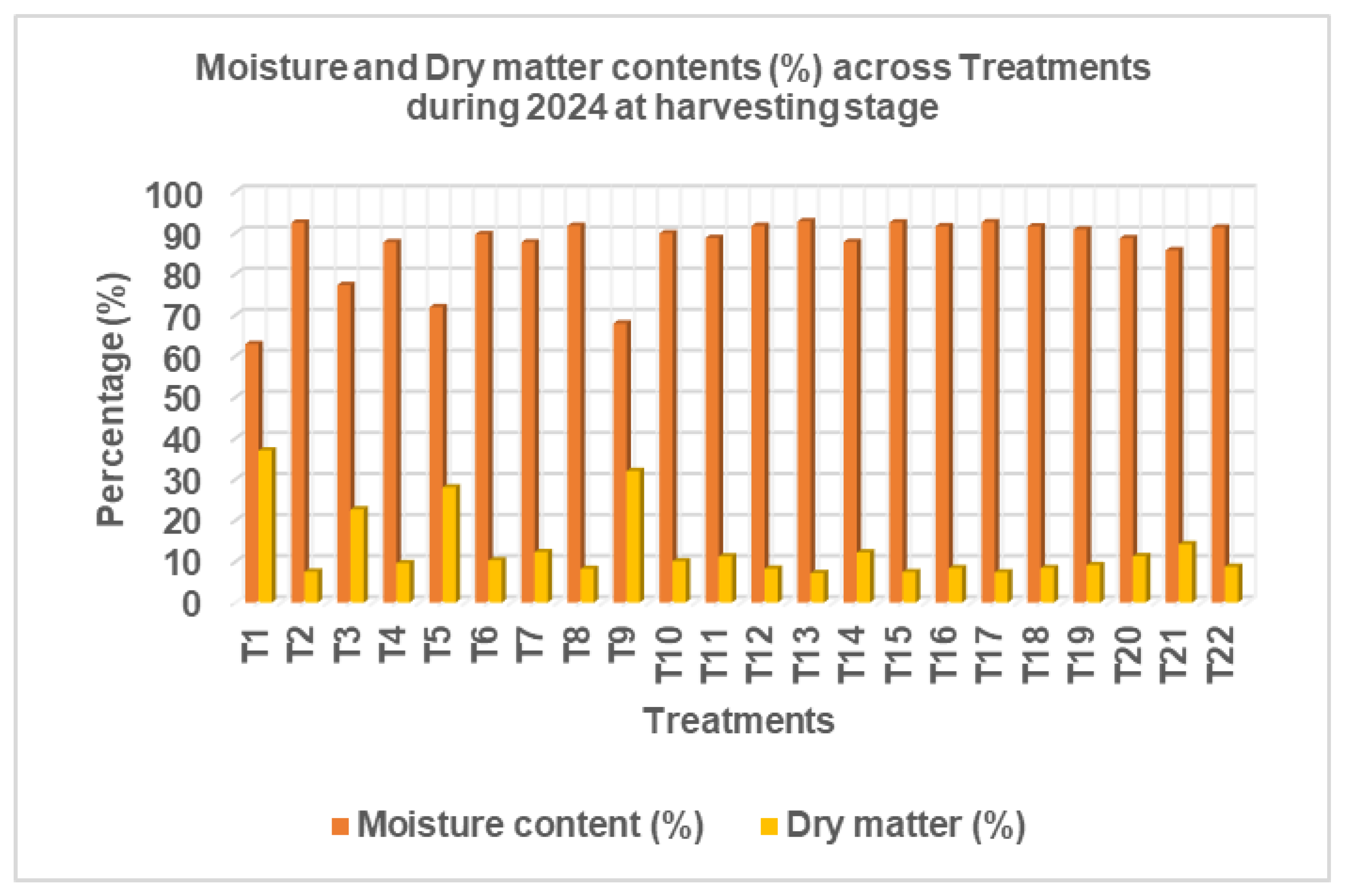

3.5.1. Effect of NPK on Moisture and Dry Matter Contents in 2024 at Maturity Stage

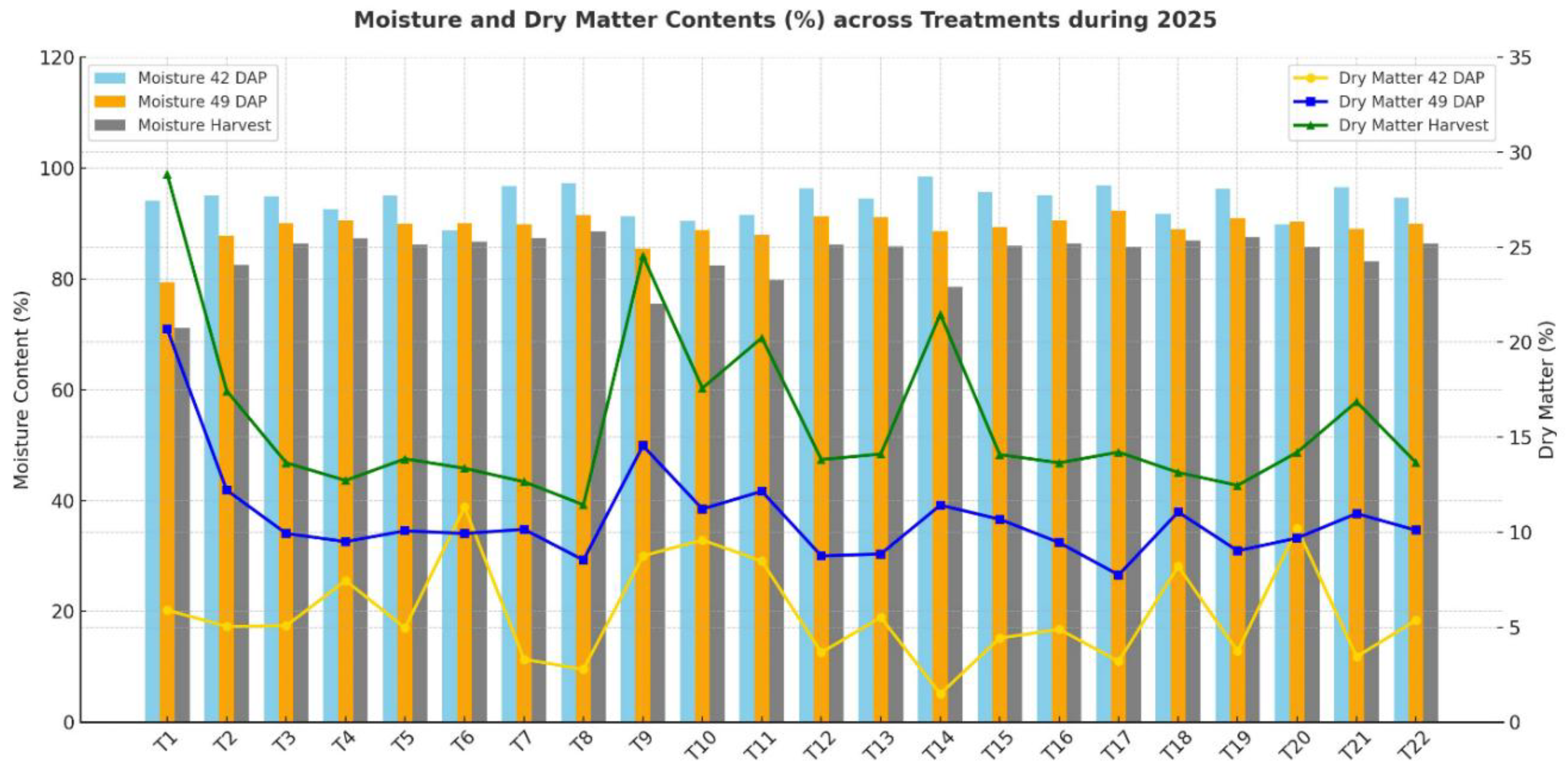

3.5.2. Effect of NPK on Moisture and Dry Matter Contents in 2025 at Different Harvesting Stages

3.6. Influence of NPK Fertilizer Rates on the Nutrient Concentrations and Uptake of Chinese Cabbage During 2024-2025 Seasons

3.6.1. Phosphorus Concentration and Uptake in Chinese Cabbage

3.6.2. Nitrogen Content and Uptake in Chinese Cabbage for 2024 and 2025 Seasons

3.6.3. Potassium Concentration and Uptake in Chinese Cabbage

3.7. Yield and Optimal Rates as Influenced by N, P and K Fertilizers on Chinese Cabbage

3.7.1. Yield Response of Chinese Cabbage to N, P, and K Fertilization

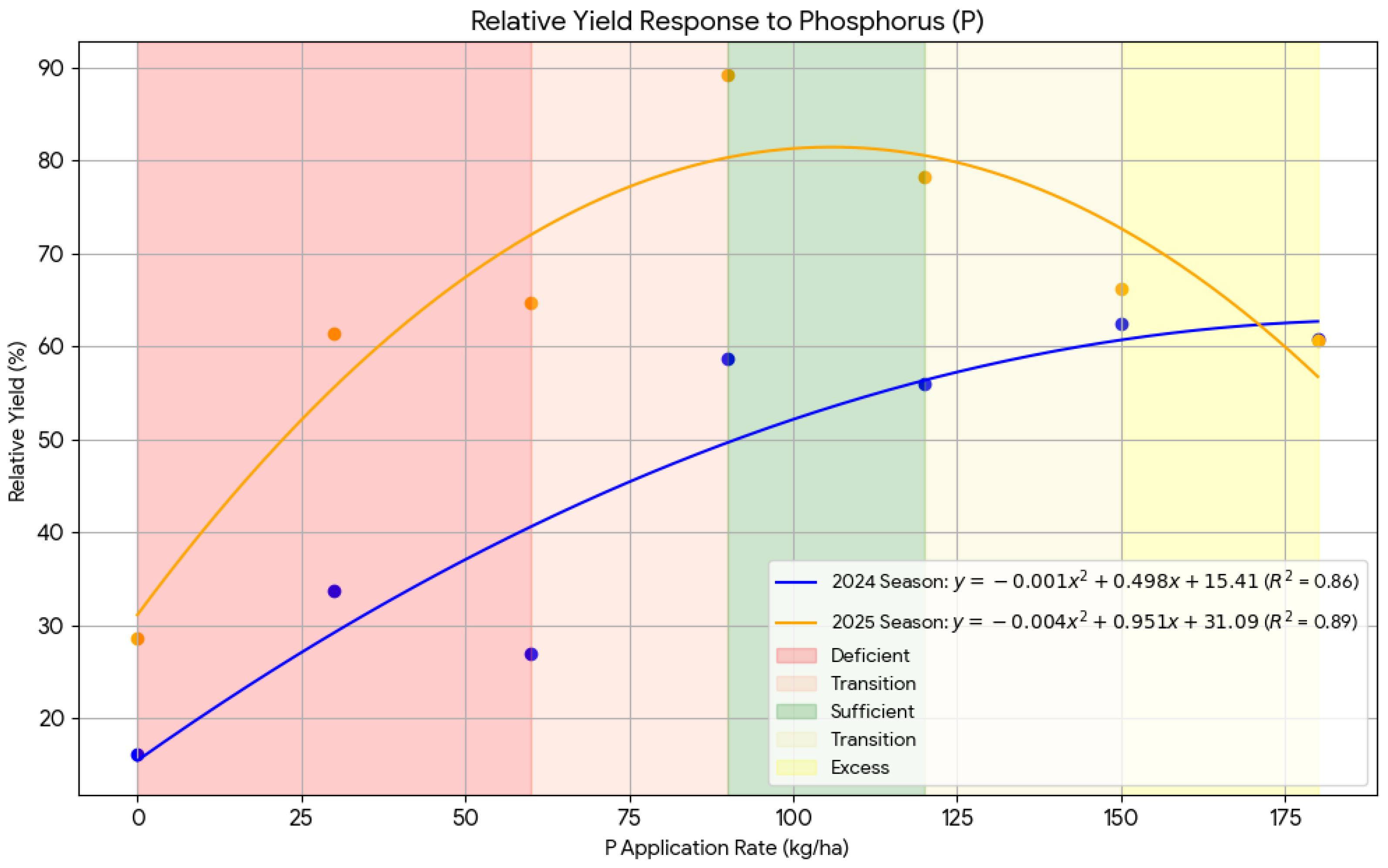

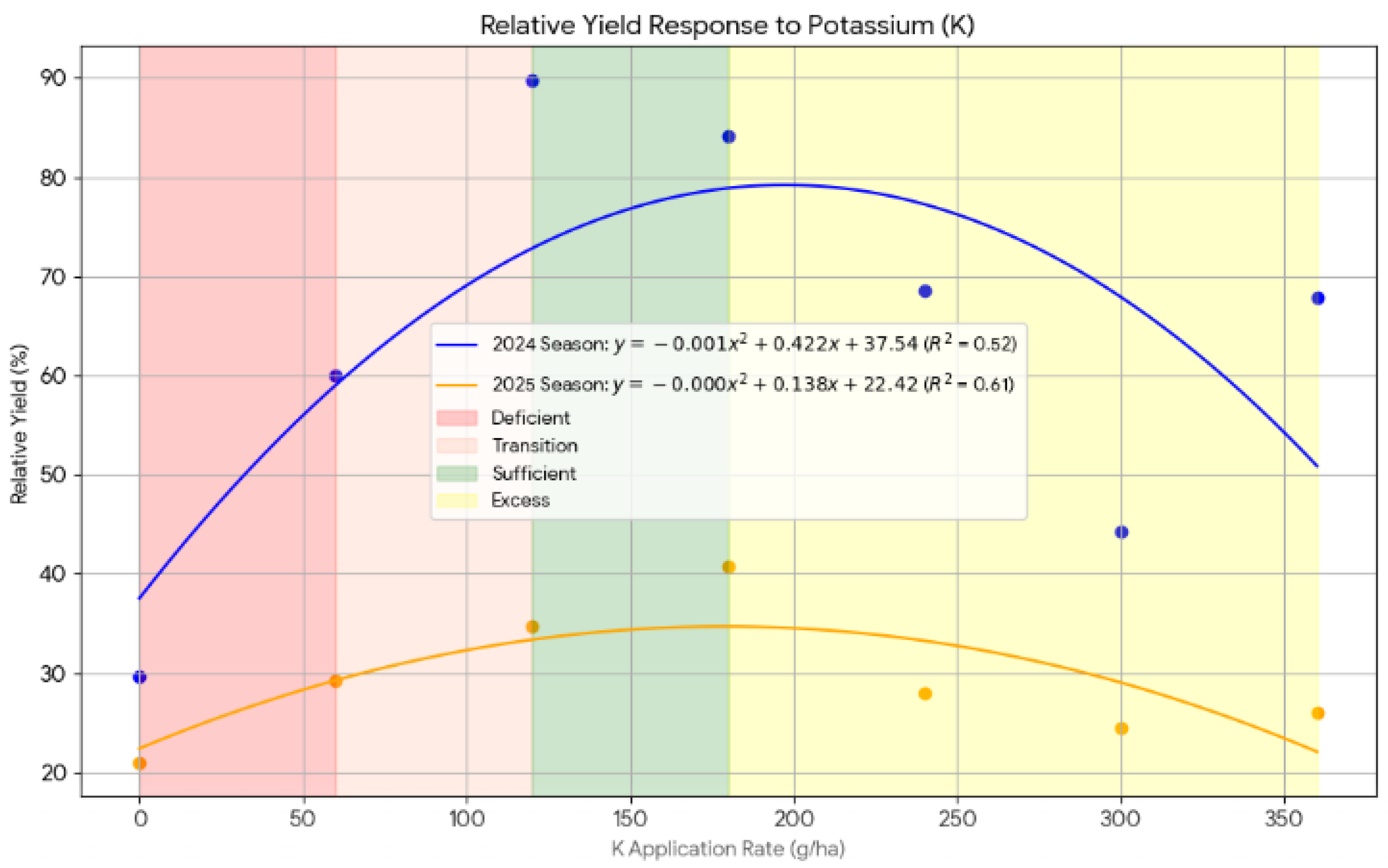

3.7.2. Relative yield of Chinese cabbage to nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium application in 2024–2025 seasons

4. Discussion

4.1. Integrated Growth Response of Chinese Cabbage to NPK Fertilization Regimes: Physiological Mechanisms and Agronomic Implications

4.2. Optimal NPK Fertilization for Enhanced Nutrient Dynamics and Yield of Chinese Cabbage

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Recommendations

- 1.

- Adopt Optimal Fertilizer Rates: Apply N220–N₃₀₀, P₉₀–P₁₂₀, and K₁₂₀–K₁₈₀ kg ha⁻¹ to maximize growth, yield, and nutrient use efficiency. Avoid excessive N (> N₃00) or K (> K180) as these lead to diminishing returns and potential nutrient losses.

- 2.

- Use Balanced Nutrient Management: Incorporate phosphorus and potassium together with nitrogen for synergistic effects on canopy development and leaf formation. Conduct regular soil testing to adjust fertilizer rates according to indigenous nutrient reserves, particularly for potassium, which may be sufficient in some cases.

- 3.

- Time Fertilizer Applications Appropriately: Use split applications, with a basal dose at planting and top-dressing around 3–4 weeks after planting (21–28 DAP), aligning nutrient supply with the period of rapid vegetative growth and root development.

- 4.

- Balance Yield with Quality: For fresh markets, full NPK rates can be applied to maximize succulence. For longer shelf life or processing markets, consider slightly lower N rates (≈N₂₂₅) to increase dry matter content and improve storability.

- 5.

- Focus on Further Research: Conduct multi-location and multi-season trials to refine recommendations across diverse climatic conditions. Explore integrated nutrient management (INM) combining optimized mineral fertilizer with organic amendments to sustain soil fertility, enhance nutrient use efficiency, and improve postharvest quality. Conducting cost-benefit analyses and environmental risk assessments of the recommended fertilizer practices.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afari-Sefa, V.; Rajendran, S.; Kessy, R. F., Karanja, D. K., Musebe, R., & Samali, S. (2016). Impact of nutritional-sensitive interventions on household production and consumption of vegetables in Tanzania. Global Food Security, 9, 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Aslam, M.; Razaq, M.; Murtaza, G. (2023). Potassium nutrition and its interaction with other nutrients: Implications for sustainable crop production. Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1104567. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Rahman, M.; Hassan, K. (2024). Environmental interactions with NPK fertilizer efficiency in tropical vegetable production systems. Journal of Tropical Agriculture, 62(3), 145-158. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Li, Y.; Waqas, M. (2021). Optimizing nitrogen management to improve vegetable yield and reduce environmental impact. Agronomy, 11(6), 1102. [CrossRef]

- Amuri, N. A., Mhoro, L., Mwasyika, T., & Semu, E. (2017). Potential of Soil Fertility Management to Improve Essential Mineral Nutrient Concentrations in Vegetables in Dodoma and Kilombero, Tanzania. Journal of Agricultural Chemistry and Environment, 6(02), 105.

- Amuri, N.; Semu, E.; Mrema, J. P., & Msanya, B. M. (2017). Soil fertility evaluation for optimization of fertilizer use in irrigated lowland rice in Tanzania. Journal of Agricultural Science, 9(12), 100–114. [CrossRef]

- Aung, S. S., Myint, A. K., Maw, T. T., Win, K. K., & Ngwe, K. (2019). Chemical and organic fertilizers application on yield, nutrient uptake and nitrogen use efficiency of chinese cabbage (Brassica pekinensis) in different soils. Journal of Agricultural Research, 6 (2), 60–69.

- Baitilwakea, M. A., Mrema, J. P., & Semu, E. (2011). Phosphorus sorption characteristics of selected Tanzanian soils. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 6(1), 1–10.

- Barrett, C.; Bevis, L. (2015). Food security and soil fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agricultural Systems, 134, 11–20.

- Bindraban, P. S., Dimkpa, C. O., & Pandey, R. (2020). Exploring phosphorus fertilizers and fertilization strategies for improved human and environmental health. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 116, 295–318. [CrossRef]

- Bongani, M.; Muhammad, S.(2020). Fertilizer use and environmental impacts in smallholder agriculture. Sustainability, 12(7), 2850.

- Brady, N.C. and Weil, R. R. (2017). The nature and properties of soil. 15th Edition. Pearson Education. Essex, England. 1104 pp.

- Bray, R.H. and Kurtz, L. T. (1945). Determination of total organic and available forms of phosphorus in soils. Soil Science, 59: 39-45.

- Bremner, J.M. and Mulvaney, C. S. (1982). Total nitrogen. In: Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2 Black et al. (Eds) Agronomy Monograph 9, American Society of Agronomy, Madison, Wisconsin, USA. pp. 1149-1170.

- Bünemann, E. K., Bongiorno, G., Bai, Z., Creamer, R. E., De Deyn, G., de Goede, R., ... & Brussaard, L. (2018). Soil quality A critical review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 120, 105–125. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, H.D. (1965). Cation exchange capacity. In: Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 1. Black, C. A., Evans, D. D., White, J. L., Ensminger, L. E. and Clark, F. E. (Eds), American Society of Agronomy, Madison, Wisconsin. pp. 891-901.

- Choudhary, V. K., Kumar, P. S., & Dixit, A. (2024). Synergistic effects of potassium and bio-fertilizers on leaf development and yield of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. subsp. pekinensis). Journal of Plant Nutrition, 47(5), 789-805.

- Chuan, L.; He, P.; Jin, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.(2019). Nutrient management for improving Chinese cabbage yield and quality in a temperate agricultural system. Agronomy Journal, 111(3), 1234–1244. [CrossRef]

- Day, P.R (1965). Particle fractionation and particle size analysis. In: Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 1. Black, C. A., Evans, D. D., White, J. L., Ensminger, L. E. and Clark, F. E. (Eds), American Society of Agronomy, Madison, Wisconsin. pp. 545-566.

- Duursma, E.K. and Dawson, R. (eds) (1981). Marine organic chemistry: Evolution, composition, interactions and chemistry of organic matter in seawater. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 521 pp.

- Everaarts, A. P., de Putter, H. & Maerere, A. P. (2017). Profitability, labour input, fertilizer application and crop protection in vegetable production in the Arusha region, Tanzania. Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences, 32(3), 5181-5202.

- Everaarts, A. P., Neeteson, J. J., & De Willigen, P. (2017). Yield and nutrient uptake of Chinese cabbage in response to nitrogen and potassium fertilization. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 40(15), 2167–2176. [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K. (2016). The use of nutrients in crop plants (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

- Fageria, N. K., Baligar, V. C., & Jones, C. A. (2011). Growth and mineral nutrition of field crops (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

- Fan, M.; Shen, J.; Yuan, L.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, F. (2021). Improving crop productivity and resource use efficiency to ensure food security and environmental quality in China. Journal of Experimental Botany, 72(2), 338–354. [CrossRef]

- Fixen, P. E., Brentrup, F., Bruulsema, T. W., Garcia, F., Norton, R., & Zingore, S. (2015). Nutrient/fertilizer use efficiency: Measurement, current situation and trends. Managing Water and Fertilizer for Sustainable Agricultural Intensification, 8–38.

- Guo, J., Liu, X., Zhang, Y., Shen, J., Han, W., Zhang, W., ... & Zhang, F. (2019). Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science, 327(5968), 1008–1010. [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M., Marschner, P., & Rengel, Z. (2018). Zinc availability in Tanzanian soils: Implications for crop production. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 64(6), 777–785. [CrossRef]

- Havlin, J. L., Beaton, J. D., Tisdale, S. L., & Nelson, W. L. (2020). Soil fertility and fertilizers (9th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Hawkesford, M. J., Kopriva, S., & De Kok, L. J. (2012). Nutrient use efficiency in plants: Concepts and approaches. Springer.

- Huang, X., Chen, L., & Wang, Z. (2023). Phosphorus nutrition and its impact on root architecture in vegetables. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 125, 134-145.

- Journal of Plant Physiology, 171(9), 656–669. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Lee, S., & Zhang, C. (2025). Optimizing nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium ratios for enhanced physiological processes in brassica crops. Scientia Horticulturae, 325, 112765.

- Kochian, L. V., Hoekenga, O. A., & Piñeros, M. A. (2004). How do crop plants tolerate acid soils? Mechanisms of aluminum tolerance and phosphorus efficiency. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 55, 459–493. [CrossRef]

- Landon, J. R. (ed.) (1991). Booker Tropical Soil Manual: A handbook for Soil Survey and Agricultural Land Evaluation in the Tropics and Subtropics. Longman, New York. 450 pp.

- Larkcom, J. (2008). Asian vegetables: Cultivation and nutritional importance. London: HarperCollins.

- Lee, J. G., Lee, B. Y., & Lee, H. J. (2010). Accumulation of phytochemicals in Chinese cabbage grown under different fertilization regimes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 58(3), 1613–1621. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Wang, Y., & He, P. (2025). The role of indigenous soil potassium reserves in vegetable production systems: Implications for fertilizer recommendations. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 71(1), 45-55.

- Lindsay W., L. and Norvell W. A. (1978). Development of a DTPA soil test for zinc, iron, manganese and copper. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 42: 421–428.

- Liu, X., Wang, Y., Qian, X., Wu, Z., Zhou, R., Hou, X., Qi, Y., & Jiang, F. (2025). Maintaining high yield and improving quality of non-heading Chinese cabbage through nitrogen reduction in different seasons. Agronomy, 15(3), 571. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q., Wang, X., & Liu, Y. (2022). Optimizing NPK fertilization to improve vegetable yield and nutrient use efficiency. Sustainability, 14(8), 4572. [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M. (2014). Mineral Fertilizers and Green Mulch in Chinese Cabbage [Brassica pekinensis (Lour.) Rupr.]: Effect on Nutrient Uptake, Yield and Internal Tipburn. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B — Soil and Plant Science. 52(1): 25-35. [CrossRef]

- Marschner, P. (2012). Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants 3rd Edition. Elsevier Ltd. 649 pp.

- Maselesele, D., Ogola, J. B. O., & Murovhi, R. N. (2022). Nutrient uptake and yield of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. Chinensis) increased with application of macadamia husk compost. Horticulturae, 8(3), Article 196. [CrossRef]

- Masso, C., Baijukya, F., & Ebanyat, P. (2017). Challenges and opportunities for agricultural intensification in the East African Highlands. Agricultural Systems, 153, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Mntambo, M. (2017). Vegetable production for income and nutrition security in Tanzania. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development, 5(2), 45–54.

- Moberg, J. R. (2001). Soil and Plant Analysis Manual. Revised Edition. The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Chemistry Department, Copenhagen, Denmark. 137 pp.

- Msanya, B. M. (2021). Soil fertility management for sustainable vegetable production in Tanzania. Morogoro: Sokoine University of Agriculture Press.

- Msanya, B. M., Kimaro, D. N., Kimbi, G. G., & Mhoro, L. (2003). Soil-landscape relationships in the Morogoro District, Tanzania. African Journal of Science and Technology, 4(1), 66–78.

- Murphy, J. and Riley, J. P. (1962). Modified single solution method for determination of phosphate in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta, 27: 31-36.

- Nelson, D. W. and Sommers L. E. (1982). Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In: Methods of Soil Analysis. II. Chemical and Microbiological properties. Second Edition. Page, A. L., Miller, R. H., Keeney, D. R., Baker, D. E., Roscoe E., Ellis, J. and Rhodes, J. D. (Eds). Madison, Wisconsin, USA. pp. 539-581.

- NSST. (1992). National Soil Service of Tanzania: Soil laboratory manual. Ministry of Agriculture, Tanzania.

- Nziguheba, G., Palm, C. A., & Bationo, A. (2016). Integrated soil fertility management in Africa: Principles, practices, and prospects. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 104(3), 347–361. [CrossRef]

- Okalebo, J. R., Gathua, K. W and Woomer, P. L. (2002). Laboratory methods of soil and plant analysis: A working manual. 2nd Edition. TSBF-CIAT and SACRED Africa, Nairobi. 127 pp.

- Pasakdee, S., Agus, F., & Van Noordwijk, M. (2006). Root architecture of Brassica crops under varying soil conditions. Plant and Soil, 285(1–2), 85–100. [CrossRef]

- Rengel, Z., & Damon, P. M. (2019). Crop nutrition: Physiology and management of nutrients. Advances in Agronomy, 158, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J., Williams, J., Daily, G., Noble, A., Matthews, N., Gordon, L., ... & Smith, J. (2017). Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio, 46(1), 4–17. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A., Santos, P., & Gonzalez, M. (2024). Combined effect of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium fertilizers on plant metabolism and growth regulation in cruciferous vegetables. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 189, 67-78. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S., Chakraborty, D., & Singh, S. B. (2020). Micronutrient management in tropical vegetable production systems. Advances in Agronomy, 161, 175–246. [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff (2014). Key to Soil Taxonomy. 12th Edition. Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Handbook, Washington DC. 372 pp.

- Thomas, G. W. (1986). Exchangeable cations. In: Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties. 2nd Edition. Page, A. L., Miller, R. H., Keeney, D. R., Baker, D. E., Roscoe E., Ellis, J. and Rhodes, J. D. (Eds). Madison, Wisconsin, USA. pp. 403-430.

- Tittonell, P., Vanlauwe, B., Leffelaar, P. A., Shepherd, K. D., & Giller, K. E. (2008). Exploring diversity in soil fertility management of smallholder farms in western Kenya. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 110(3–4), 149–165. [CrossRef]

- Traka, M. H. (2016). Health benefits of glucosinolates. Advances in Botanical Research, 80, 247–279. [CrossRef]

- Tubiello, F. N., Conchedda, G., Wanner, N., Federici, S., Rossi, S., & Grassi, G. (2023). Greenhouse gas emissions from fertilizer use: Trends and mitigation options. Nature Food, 4, 452–461. [CrossRef]

- Van Ranst, E., Nerloo, M., Demeyer, A. and Pauwels, J. M. (1999). Manual for the soil Chemistry and Fertilizer Laboratory. Analytical Methods for soils and Plants Equipment and Management of Consumable. International Training Centre for Post-Gradutes Soil Scientists and Department of Applied Analytical and Physical Chemistry. Laboratory of Analytical Chemistry and Applied Ecochemistry, University of Ghent. 243 p.

- Vanlauwe, B., Descheemaeker, K., Giller, K. E., Huising, J., Merckx, R., Nziguheba, G.,... & Zingore, S. (2015). Integrated soil fertility management in sub-Saharan Africa: Unravelling local adaptation. Soil, 1(1), 491–508. [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P. M., Naylor, R., Crews, T., David, M. B., Drinkwater, L. E., Holland, E.,... & Zhang, F. S. (2009). Nutrient imbalances in agricultural development. Science, 324(5934), 1519–1520. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Zhang, J., & Sun, Y. (2022). Nitrogen management in vegetable production: Balancing productivity and environmental protection. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 337, 108057. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Li, H., & Zhang, P. (2023). Calcium and magnesium roles in vegetable stress tolerance. Journal of Plant Science, 92(5), 500-515.

- Zhang, H., Xu, F., Wu, Y., Hu, H., & Dai, X. (2017). Progress of potassium management in agricultural systems of China. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 16(12), 2800–2810. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. (2022). Global production and market trends of Chinese cabbage. Horticultural Plant Journal, 8(1), 15–2.

- Zörb, C., Senbayram, M., & Peiter, E. (2014). Potassium in agriculture—Status and perspectives.

| Parameter | Soil A | Critical Level | Fertility Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (H₂O, 1:2.5) | 5.01 | 5.5–7.3 | Strongly acidic | Thiagalingam (2003); Landon (1991) |

| EC (µS cm⁻¹) | 226 | < 4000 | Very low | NSST (1992) |

| Organic carbon (%) | 1.8 | 2.51–3.5 | Medium | Landon (1991) |

| Organic matter (%) | 3.10 | 4.3–6.0 | Medium | Landon (1991) |

| Total nitrogen (%) | 0.14 | > 0.5 | Low | Tisdale et al. (2004) |

| C:N ratio | 12.86 | 8–13 | Good quality | NSST (1992) |

| Available P (mg kg⁻¹) | 2.24 | > 20 | Very low | Nziguheba et al. (2016) |

| Available S (mg kg⁻¹) | 39.2 | 11–15 | Very high | Landon (1991) |

| Exch. K (Cmol(+) kg⁻¹) | 0.95 | > 0.4 | High | Landon (1991) |

| Exch. Ca (Cmol(+) kg⁻¹) | 0.63 | 2.6–5.0 | Medium | Landon (1991) |

| Exch. Mg (Cmol(+) kg⁻¹) | 3.51 | 1.1–2.0 | Very high | Landon (1991) |

| Exch. Na (Cmol(+) kg⁻¹) | 0.19 | 0.1–0.3 | Low | Landon (1991) |

| CEC (Cmol(+) kg⁻¹) | 7.28 | 15–40 | Low | Landon (1991) |

| Ca:Mg ratio | 0.179 | 3:1 | Unfavourable | Landon (1991) |

| K:Mg ratio | 0.271 | < 1:1 | Adequate | Rengel & Damon (2019) |

| ESP (%) | 2.61 | < 6.0 | Non-sodic | NSST (1992) |

| Base saturation (%) | 72.53 | > 75 | Medium | Landon (1991) |

| Cu (mg kg⁻¹) | 2.66 | > 0.6 | Very high | Landon (1991) |

| Zn (mg kg⁻¹) | 0.92 | > 1 | Medium | Landon (1991) |

| Fe (mg kg⁻¹) | 34.36 | > 4.5 | Very high | Landon (1991) |

| Mn (mg kg⁻¹) | 45.55 | > 1 | Very high | Landon (1991) |

| Clay (%) | 54.12 | 35–60 | High | USDA (2017) |

| Silt (%) | 9.64 | 20–40 | Low | USDA (2017) |

| Sand (%) | 36.24 | 20–50 | Medium | USDA (2017) |

| Textural class | Clay | – | Moderate water-holding capacity | USDA (2017) |

| Nitrogen Analysis for 2024-2025 Seasons | Phosphorus Analysis for 2024-2025 Seasons | Potasium Analysis for 2024-2025 Seasons | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application Rate (kg/ha) | 2024 | 2025 | Application Rate (kg/ha) | 2024 | 2025 | Application Rate (kg/ha) | 2024 | 2025 | ||||||

| N_% | N_Uptake | N_% | N_Uptake | P_% | P_Uptake | P_% | P_Uptake | K_% | K_Uptake | K_% | K_Uptake | |||

| Absolute control | 2.68ab | 0.32a | 0.7a | 0.26a | Absolute control | 0.11ab | 0.01a | 0.01a | 0.01a | Absolute control | 1.57a | 0.19a | 1.27a | 0.14a |

| N0 | 3.7ab | 1.98ab | 1.03ab | 0.52ab | P0 | 0.04a | 0.01a | 0.14ab | 0.03ab | K0 | 2ab | 1.74ab | 1.7ab | 1.05b |

| N75 | 2.91ab | 0.68ab | 2.04bc | 1.47abc | P30 | 0.13ab | 0.04a | 0.15ab | 0.08ab | K60 | 2.57bc | 2.13ab | 2.13b | 1.35bc |

| N150 | 4.16ab | 2.45b | 2.36c | 1.51abc | P60 | 0.39ab | 0.14ab | 0.27ab | 0.17ab | K120 | 3.17cd | 2.18ab | 2.9b | 1.9cd |

| N225 | 4.15ab | 2.32b | 4.47de | 3.02bc | P90 | 0.21ab | 0.14ab | 0.28ab | 0.21b | K180 | 3.53de | 2.05ab | 3.2c | 2.5 de |

| N300 | 4.27b | 2.41b | 4.6e | 3.39c | P120 | 0.24ab | 0.15ab | 0.34b | 0.22 b | K240 | 4.13e | 2.22b | 3.87d | 3.14e |

| N375 | 3.14ab | 0.8ab | 3.22cd | 2.41abc | P150 | 0.23ab | 0.16ab | 0.28ab | 0.1 ab | K300 | 3.17cd | 1.32ab | 3.1c | 1.6bc |

| N450 | 1.07a | 1.04ab | 2.14bc | 1.78abc | P180 | 0.52b | 0.45b | 0.18ab | 0.09ab | K360 | 2.13ab | 1.7 ab | 2.1b | 1.35bc |

| p-value | 0.044 | 0.057 | <0.001 | 0.006 | p_value | 0.246 | 0.115 | 0.223 | 0.153 | p_value | <0.001 | 0.277 | <0.001 | < 0.001 |

| CV (%) | 33.2 | 61.4 | 17.4 | 48.8 | CV_% | 92.6 | 123.5 | 62 | 82.3 | CV_% | 10.5 | 58.5 | 8 | 17.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).