Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Oliviculture constitutes a fundamental Mediterranean rural activity and predominantly for Greece as it primarily accounts for the country’s substantial socio-economic development. Even though the olive tree represents one of the best acclimated species, its overall performance may be significantly impacted by changes of the climate expressed by the extreme weather conditions commonly observed in recent decades. Thus, by considering the lack of scientific detection on the climate suitability evaluation of the olive groves especially over the entire Greek territory, a conjunction between the geomorphological parameters’ mapping of Greece (altitude, aspect, slope and terrain roughness) and the respective required atmospheric conditions mandatory for the olive’s qualitative and quantitative attribution (temperature, precipitation, frost days) has been performed. Every parameter is reclassified to translate its value to a score, and the final suitability map is the outcome of the aggregation of all score maps. Individually, the overall geomorphological and climate suitability for oliviculture is high in Greece given the extensive area resulting as optimal geomorphological and climatic conditions (34.44% and 59.4%, respectively) and overall optimal pedoclimatic conditions (56.61%) for oliviculture. The model maybe characterized by simplicity, usability, flexibility and efficiency. The present modelling procedure may constitute means for identifying suitable areas for sustainable and productive development of the olive culture.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

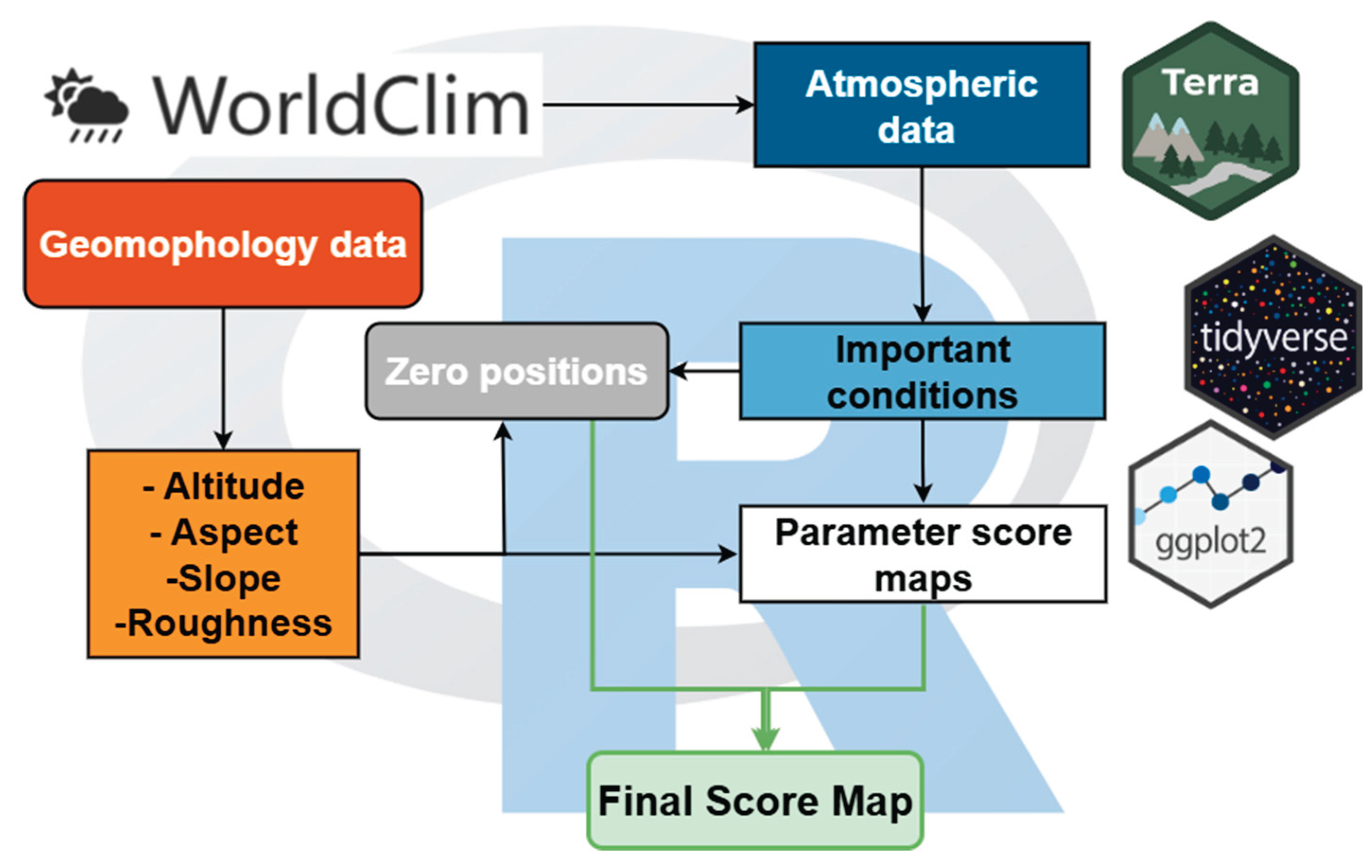

2. Materials and Methods

- Each parameter is classified as a score from 1 to 10. The score 1 is assigned to acceptable conditions of the parameter in relation to olive tree cultivation and score 10 is assigned to the optimal conditions of this parameter. We can also assign a score of 0 where this parameter is unsuitable for cultivation. So, in case the conditions are unsuitable for olive groves the score is zero (0) and when are suitable for this cultivation the score can be from 1 (the lower suitability) to 10 (the higher suitability). In case for one model’s parameter the score is 0 in a site, this site remains unsuitable no matter the score of the rest parameters. The score tables can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S1 to Table S11).

- The geomorphological parameters after the classification to the suitability score (Figure S1 to figure S4) have been summed to a final geomorphological score raster. This raster has been linearly normalized to obtain a score from 1 to 10 for suitable sites. In case one parameter takes zero (0) score, this score remains to the final geomorphological map (Figure 2).

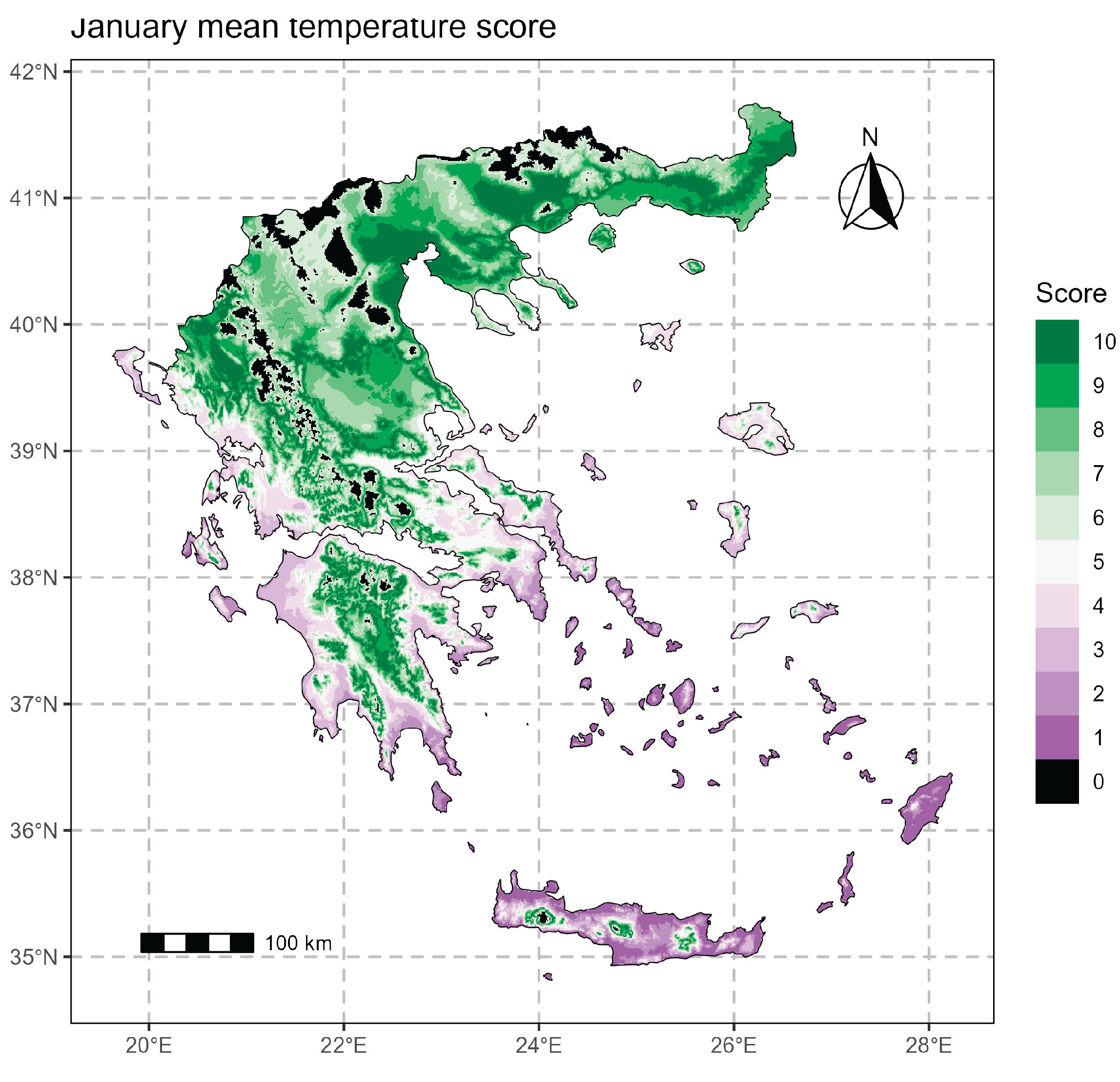

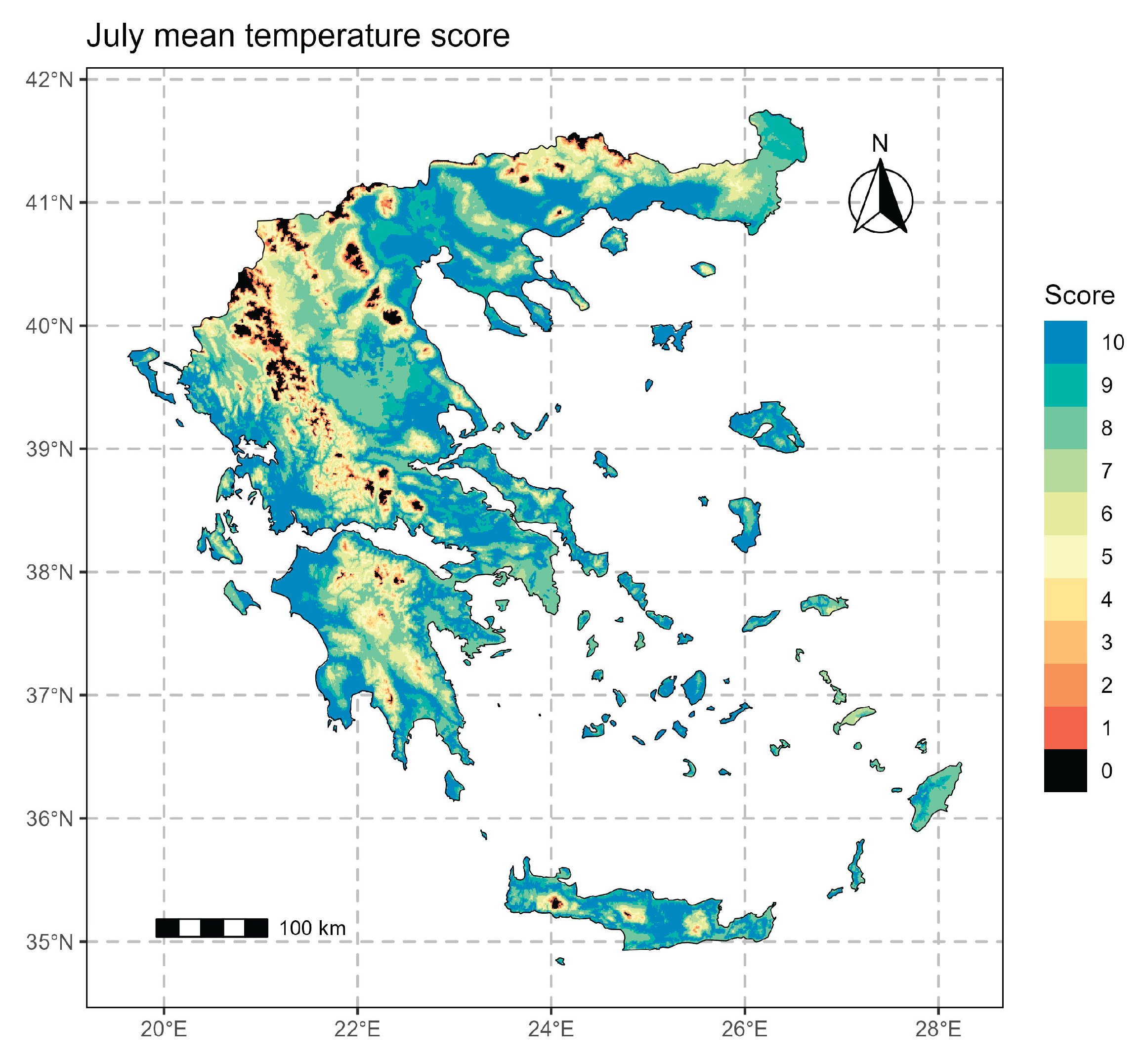

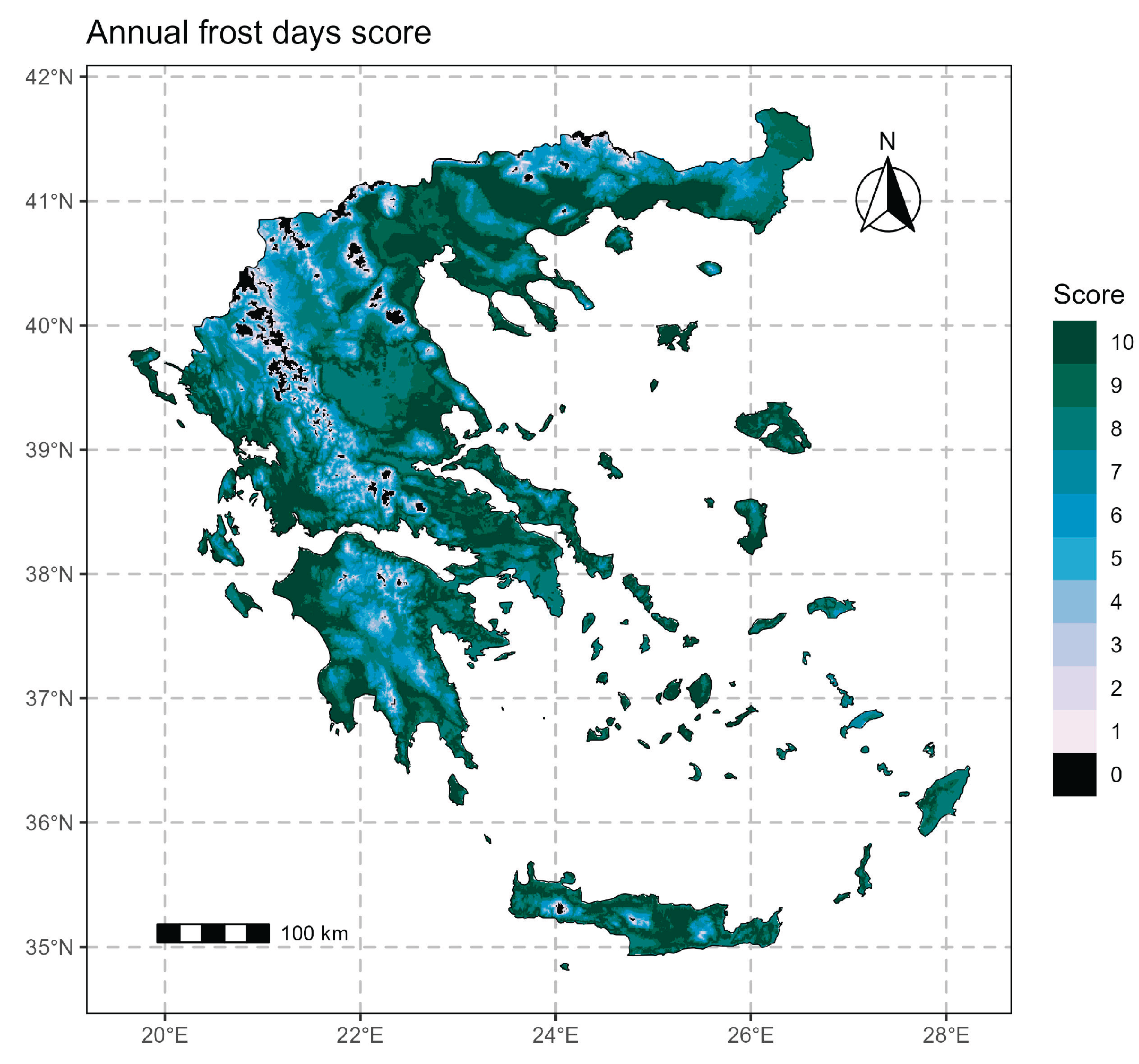

- The climatic parameters rasters have been classified according to the related score tables (Table S5 to Table S11) and have been mapped (Figure 3 to Figure 9). After this step the climatic score rasters have been summed up to a final climatic score raster. This raster has been linearly normalized to have scores from 1 for the less suitable areas up to 10 for the optimal areas in terms of climatic conditions and has been mapped (Figure 10) accordingly. In case a climatic parameter does not allow olive cultivation, in the final raster has been set the zero score.

- Finally, the geomorphology raster score and the climatic raster score have been added to a final suitability score raster. Geomorphology gives the 20% of the final score and the climate gives the rest 80% for this version of the model. The final score map has been linearly normalized to have scores from 1 to 10 for the suitable areas and 0 for unsuitable areas. This raster has been mapped in Figure 11.

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

- Individually, the overall geomorphological and climate suitability for oliviculture is high in Greece.

- A quite extensive area (34.44% surface coverage) appears whith most optimal geomorphological conditions for oliviculture.

- Large areas (59.4% surface coverage) result with most optimal climatic conditions for the olive culture.

- Conjunction of geomorphology suitability and climatic suitability mapping highlights a substantial part of the country’s area (approximately 60%) appearing as optimal for the olive groves.

- Overall, the olive suitability model may be characterized as efficient.

- The observed differentiations of the model-derived final suitability map from the recorded olive growing areas over Greece may be justified by the application of limited climate and geo-morphology components in the model.

- The present modeling procedure may serve as a tool for indicating suitable areas for the development of sustainable and productive olive culture.

- The model is characterized by simplicity, usability, and flexibility.

- Introducing environmental parameters impacted by future climate change into the model may create a new map of climatic suitability.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Anastasiou, E., Balafoutis, A.T., Fountas, S., 2023. Trends in Remote Sensing Technologies in Olive Cultivation. Smart Agric. Technol. 3, 100103. [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Castro, S., Gonçalves, J.F., Moreno, M., Villar, R., 2020. Projected climate changes are expected to decrease the suitability and production of olive varieties in southern Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 709, 136161. [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, O.S., Rodias, E., Terpou, A., Afratis, N., Athanasiou, G., Zahariadis, T., 2024. Bactrocera oleae Control and Smart Farming Technologies for Olive Orchards in the Context of Optimal Olive Oil Quality: A Review. Agronomy 14, 2586. [CrossRef]

- Bonizzato, A., 2020. The socio-economic impacts of organic and conventional olive growing in Italy - New Medit. URL https://newmedit.ciheam.org/2020/04/10/the-socio-economic-impacts-of-organic-and-conventional-olive-growing-in-italy/ (accessed 9.24.25).

- Bordoni, M., Gambarani, A., Giganti, M., Vivaldi, V., Rossi, G., Bazzano, P., Meisina, C., 2025. Present and Projected Suitability of Olive Trees in a Currently Marginal Territory in the Face of Climate Change: A Case Study from N-Italy. Sustainability 17, 1949. [CrossRef]

- Büttner, G., 2014. CORINE Land Cover and Land Cover Change Products, in: Manakos, I., Braun, M. (Eds.), Land Use and Land Cover Mapping in Europe, Remote Sensing and Digital Image Processing. Springer Netherlands, pp. 55–74. [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, J.M., Ruiz-Ramos, M., Soriano, M.A., Gabaldón-Leal, C., Santos, C., Lorite, I.J., 2020. Identifying adaptation strategies to climate change for Mediterranean olive orchards using impact response surfaces. Agric. Syst. 185, 102937. [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, I., Polychroni, I., Psomiadis, E., Nastos, P., 2021. Spatiotemporal Estimation of the Olive and Vine Cultivations’ Growing Degree Days in the Balkans Region. Atmosphere 12, 148. [CrossRef]

- den Herder, M., Moreno, G., Mosquera-Losada, R.M., Palma, J.H.N., Sidiropoulou, A., Santiago Freijanes, J.J., Crous-Duran, J., Paulo, J.A., Tomé, M., Pantera, A., Papanastasis, V.P., Mantzanas, K., Pachana, P., Papadopoulos, A., Plieninger, T., Burgess, P.J., 2017. Current extent and stratification of agroforestry in the European Union. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 241, 121–132. [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E., Hijmans, R.J., 2017. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 4302–4315. [CrossRef]

- Foscolou, A., Critselis, E., Panagiotakos, D., 2018. Olive oil consumption and human health: A narrative review. Maturitas 118, 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H., Moriondo, M., Leolini, L., Santos, J.A., 2021. Mediterranean Olive Orchards under Climate Change: A Review of Future Impacts and Adaptation Strategies. Agronomy 11, 56. [CrossRef]

- Guise, I., Silva, B., Mestre, F., Muñoz-Rojas, J., Duarte, M.F., Herrera, J.M., 2024. Climate change is expected to severely impact Protected Designation of Origin olive growing regions over the Iberian Peninsula. Agric. Syst. 220, 104108. [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R.J., Bivand, R., Forner, K., Ooms, J., Pebesma, E., Sumner, M.D., 2022. terra: Spatial Data Analysis [WWW Document]. URL https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra (accessed 7.7.22).

- Honorio, F., Aguirado, C., Paniagua, L.L., García-Martín, A., Rebollo, L., Rebollo, F.J., 2024. Exploring the Climate and Topography of Olive Orchards in Extremadura, Southwestern Spain. Land 13, 495. [CrossRef]

- International Olive Council, 2024. World Market of Olive Oil and Table Olives - Data From December 2024. Int. Olive Counc. URL https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/world-market-of-olive-oil-and-table-olives-data-from-december-2024/ (accessed 9.23.25).

- Jimenez-Lopez, C., Carpena, M., Lourenço-Lopes, C., Gallardo-Gomez, M., Lorenzo, J.M., Barba, F.J., Prieto, M.A., Simal-Gandara, J., 2020. Bioactive Compounds and Quality of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Foods 9, 1014. [CrossRef]

- Kakkavou, K., Gemtou, M., Fountas, S., 2024. Drivers and barriers to the adoption of precision irrigation technologies in olive and cotton farming—Lessons from Messenia and Thessaly regions in Greece. Smart Agric. Technol. 7, 100401. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Verma, S., 2022. Ensemble modeling to predict the impact of future climate change on the global distribution of Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata. Front. For. Glob. Change 5. [CrossRef]

- Kokkotos, E., Zotos, A., Tsirogiannis, G., Patakas, A., 2021. Prediction of Olive Tree Water Requirements under Limited Soil Water Availability, Based on Sap Flow Estimations. Agronomy 11, 1318. [CrossRef]

- Kostelenos, G., Kiritsakis, A., 2017. Olive Tree History and Evolution, in: Olives and Olive Oil as Functional Foods. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Koubouris, G., Psarras, G., 2024. Pedoclimatic and Landscape Conditions of Greek Olive Groves, in: Muñoz-Rojas, J., García-Ruiz, R. (Eds.), The Olive Landscapes of the Mediterranean: Key Challenges and Opportunities for Their Sustainability in the Early XXIst Century. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, pp. 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P., Giorgi, F., Rohling, E., Seager, R., 2023. Chapter 3 - Mediterranean climate: past, present and future, in: Schroeder, K., Chiggiato, J. (Eds.), Oceanography of the Mediterranean Sea. Elsevier, pp. 41–91. [CrossRef]

- López-Bernal, Á., Morales, A., García-Tejera, O., Testi, L., Orgaz, F., De Melo-Abreu, J.P., Villalobos, F.J., 2018. OliveCan: A Process-Based Model of Development, Growth and Yield of Olive Orchards. Front. Plant Sci. 9. [CrossRef]

- Lorite, I.J., Gabaldón-Leal, C., Ruiz-Ramos, M., Belaj, A., de la Rosa, R., León, L., Santos, C., 2018. Evaluation of olive response and adaptation strategies to climate change under semi-arid conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 204, 247–261. [CrossRef]

- Mairech, H., López-Bernal, Á., Moriondo, M., Dibari, C., Regni, L., Proietti, P., Villalobos, F.J., Testi, L., 2021. Sustainability of olive growing in the Mediterranean area under future climate scenarios: Exploring the effects of intensification and deficit irrigation. Eur. J. Agron. 129, 126319. [CrossRef]

- Mairech, H., López-Bernal, Á., Moriondo, M., Dibari, C., Regni, L., Proietti, P., Villalobos, F.J., Testi, L., 2020. Is new olive farming sustainable? A spatial comparison of productive and environmental performances between traditional and new olive orchards with the model OliveCan. Agric. Syst. 181, 102816. [CrossRef]

- Manna, P., Bonfante, A., Colandrea, M., Di Vaio, C., Langella, G., Marotta, L., Mileti, F.A., Minieri, L., Terribile, F., Vingiani, S., Basile, A., 2020. A geospatial decision support system to assist olive growing at the landscape scale. Comput. Electron. Agric. 168, 105143. [CrossRef]

- Marakis, G., Gaitis, F., Mila, S., Papadimitriou, D., Tsigarida, E., Mousia, Z., Karpouza, A., Magriplis, E., Zampelas, A., 2021. Attitudes towards Olive Oil Usage, Domestic Storage, and Knowledge of Quality: A Consumers’ Survey in Greece. Nutrients 13, 3709. [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulos, G., Kasapi, K.A., Koubouris, G., Psarras, G., Arampatzis, G., Hatzigiannakis, E., Kavvadias, V., Xiloyannis, C., Montanaro, G., Malliaraki, S., Angelaki, A., Manolaraki, C., Giakoumaki, G., Reppas, S., Kourgialas, N., Kokkinos, G., 2020. Adaptation of Mediterranean Olive Groves to Climate Change through Sustainable Cultivation Practices. Climate 8, 54. [CrossRef]

- Montsant, A., Baena, O., Bernárdez, L., Puig, J., 2021. Modelling the impacts of climate change on potential cultivation area and water deficit in five Mediterranean crops. Span. J. Agric. Res. 19, e0301–e0301. [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.-F., Lees, M., 2018. FoodIntegrity Handbook: Eurofins Analytics France.

- Moriondo, M., Ferrise, R., Trombi, G., Brilli, L., Dibari, C., Bindi, M., 2015. Modelling olive trees and grapevines in a changing climate. Environ. Model. Softw. 72, 387–401. [CrossRef]

- Moriondo, M., Leolini, L., Brilli, L., Dibari, C., Tognetti, R., Giovannelli, A., Rapi, B., Battista, P., Caruso, G., Gucci, R., Argenti, G., Raschi, A., Centritto, M., Cantini, C., Bindi, M., 2019. A simple model simulating development and growth of an olive grove. Eur. J. Agron. 105, 129–145. [CrossRef]

- Moriondo, M., Trombi, G., Ferrise, R., Brandani, G., Dibari, C., Ammann, C.M., Lippi, M.M., Bindi, M., 2013. Olive trees as bio-indicators of climate evolution in the Mediterranean Basin. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 22, 818–833. [CrossRef]

- Ozalp, A.Y., Akinci, H., 2023. Evaluation of Land Suitability for Olive (Olea europaea L.) Cultivation Using the Random Forest Algorithm. Agriculture 13, 1208. [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E., 2018. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R J. 10, 439–446.

- Puig-Sirera, À., Rallo, G., Paredes, P., Paço, T.A., Minacapilli, M., Provenzano, G., Pereira, L.S., 2021. Transpiration and Water Use of an Irrigated Traditional Olive Grove with Sap-Flow Observations and the FAO56 Dual Crop Coefficient Approach. Water 13, 2466. [CrossRef]

- Rallo, G., Baiamonte, G., Juárez, J.M., Provenzano, G., 2014. Improvement of FAO-56 Model to Estimate Transpiration Fluxes of Drought Tolerant Crops under Soil Water Deficit: Application for Olive Groves. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 140, A4014001. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B., Darouich, H., Oliveira, A.R., Farzamian, M., Monteiro, T., Castanheira, N., Paz, A., Gonçalves, M.C., Pereira, L.S., 2023. Water use and soil water balance of Mediterranean tree crops assessed with the SIMDualKc model in orchards of southern Portugal. Agric. Water Manag. 279, 108209. [CrossRef]

- Ropero, R.F., Rumí, R., Aguilera, P.A., 2019. Bayesian networks for evaluating climate change influence in olive crops in Andalusia, Spain. Nat. Resour. Model. 32, e12169. [CrossRef]

- Skiada, V., Tsarouhas, P., Varzakas, T., 2019. Preliminary Study and Observation of “Kalamata PDO” Extra Virgin Olive Oil, in the Messinia Region, Southwest of Peloponnese (Greece). Foods 8, 610. [CrossRef]

- Smoly, I., Elbaz, H., Engelen, C., Wechsler, T., Elbaz, G., Ben-Ari, G., Samach, A., Friedlander, T., 2025. A model estimating the level of floral transition in olive trees exposed to warm periods during winter. J. Exp. Bot. 76, 1266–1284. [CrossRef]

- Solomou, A.D., Sfougaris, A., 2021. Contribution of Agro-Environmental Factors to Yield and Plant Diversity of Olive Grove Ecosystems (Olea europaea L.) in the Mediterranean Landscape. Agronomy 11, 161. [CrossRef]

- Tsiaras, S., Domakinis, C., 2023. Use of GIS in Selecting Suitable Tree Crop Cultivation Sites in Mountainous Less Favoured Areas: An Example from Greece. Forests 14, 1210. [CrossRef]

- Urdiales-Flores, D., Zittis, G., Hadjinicolaou, P., Cherchi, A., Alessandri, A., Peleg, N., Lelieveld, J., 2024. A Global Analysis of Historical and Future Changes in Mediterranean Climate-Type Regions. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 5607–5620. [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, F.J., López-Bernal, Á., García-Tejera, O., Testi, L., 2023. Is olive crop modelling ready to assess the impacts of global change? Front. Plant Sci. 14. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H., Chang, W., Henry, L., Pedersen, T.L., Takahashi, K., Wilke, C., Woo, K., Yutani, H., Dunnington, D., 2020a. ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics [WWW Document]. URL https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggplot2 (accessed 2.5.20).

- Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., Müller, K., 2020b. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation [WWW Document]. URL https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed 4.25.20).

| Geomorphological Suitability Score | Total (%) |

| 0 | 24.12 |

| 2 | 0.03 |

| 3 | 0.84 |

| 4 | 4.97 |

| 5 | 9.92 |

| 6 | 9.76 |

| 7 | 15.92 |

| 8 | 16.82 |

| 9 | 12.21 |

| 10 | 5.41 |

| Climatic Suitability Score | Area covered (%) |

| 0 | 36.29 |

| 5 | 0.00 |

| 6 | 0.54 |

| 7 | 3.77 |

| 8 | 17.02 |

| 9 | 36.00 |

| 10 | 6.38 |

| Suitability Score | Total (%) | Over CLC areas (%) |

| 0 | 41.93 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 6 | 1.44 | 0.13 |

| 7 | 14.61 | 8.28 |

| 8 | 32.23 | 58.53 |

| 9 | 9.76 | 33.05 |

| 10 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).