1. Introduction

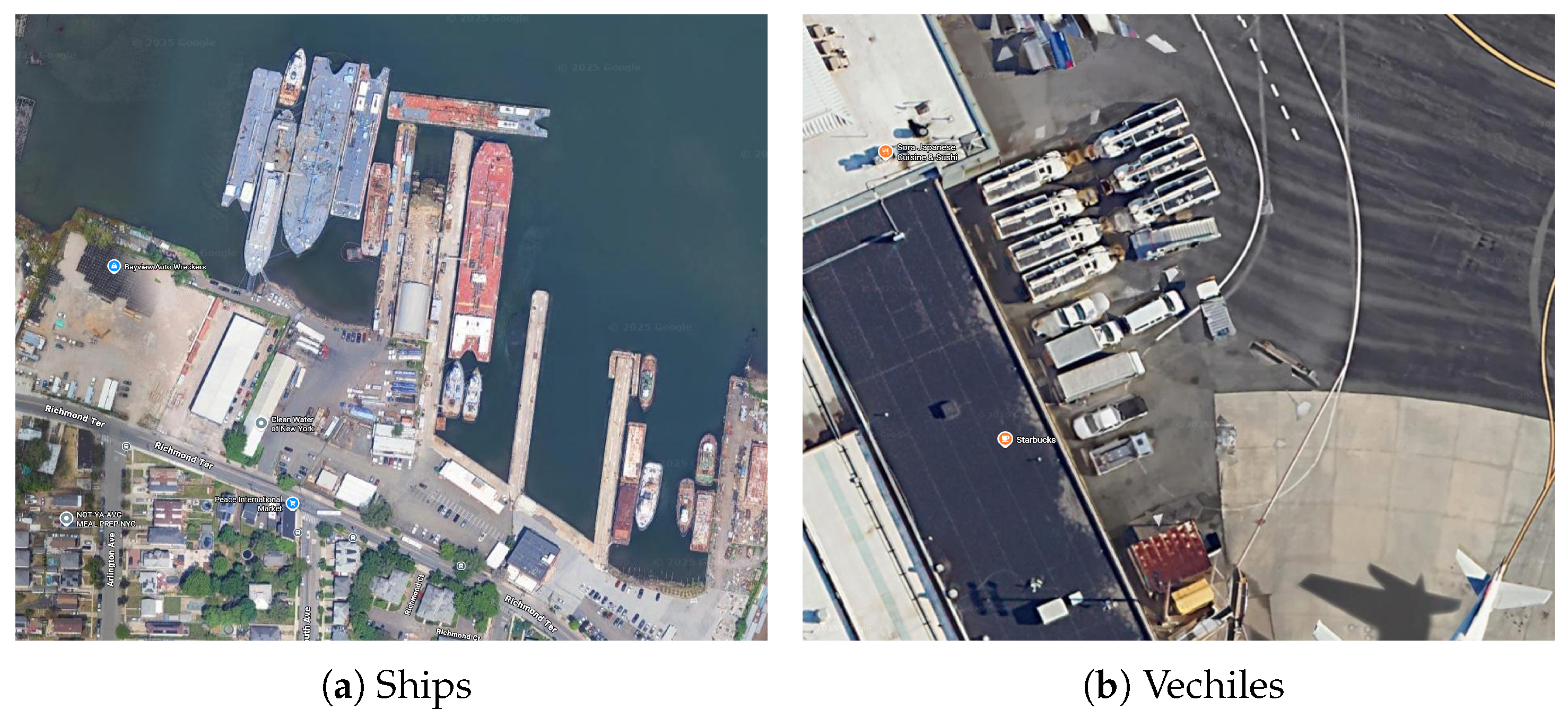

Fine-grained interpretation of remote sensing images have been attracting increasing attention and are being more widely applied in many fields related to remote sensing monitoring. The core significance of fine-grained recognition and analysis of remote sensing images lies in breaking through the limitations of traditional macro interpretation and realizing accurate cognition and efficient management of the Earth’s surface system through sub-class differentiation of ground objects (such as subdivision of tree species in vegetation, Different types objects as in

Figure 1, and functional classification in buildings [

1,

2]). Its value is mainly manifested in three aspects.

Firstly, from the perspective of the data generation layer, fine-grained interpretation has greatly improved the ability to monitor and discover key features in remote sensing applications. Fine-grained recognition is a “precision sensing method” for accurately perceiving surface changes, providing high-quality data input for subsequent governance decisions. For example, in disaster scenarios, through the subdivision of building damage levels (slight cracks or structural collapse [

3,

4]) and land cover types in flooded areas (farmland or residential areas or roads), “risk heat maps” can be generated in real-time to support the priority allocation of rescue forces; in environmental monitoring, the differential identification of water algal species and the degree of vegetation diseases and pests (mild infection or large-area withering [

5,

6]) can capture “early signals” that are easily missed by macro monitoring, striving for response time for pollution control and pest prevention; even in the military field, the fine-grained distinction of target types (armored vehicles or ordinary trucks) and camouflage states (natural vegetation camouflage or artificial camouflage [

7,

8]) can improve the accuracy of battlefield situation awareness. This ability to capture “quantitative change details” upgrades dynamic monitoring from “discovering changes” to “analyzing change mechanisms”, providing a data base for risk prevention and control.

Secondly, fine-grained interpretation supports refined governance and decision-making optimization in the field of remote sensing. Based on fine-grained monitoring data, various governance decisions have been transformed from “extensive” to “precision”. For example, in natural resource management, the subdivided data of crop types and growth stages can guide differentiated irrigation and fertilization; the distinction of tree species and health grades can optimize logging plans and ecological restoration schemes. In urban governance, the fine-grained analysis of construction land functions and building attributes provides accurate basis for floor area ratio adjustment and old city reconstruction. Methods for automatic airport detection from remote sensing images, which detect runways, terminals, etc., support precise functional classification of airport infrastructure [

9]. Compared with macro classification, fine-grained data can eliminate the drawback of “homogeneous management of similar ground objects”-for example, in the governance of wetlands, if only the general category of wetland is unknown, it is difficult to formulate targeted protection measures, but after subdividing into “swamp wetlands” and “tidal flat wetlands”, protection resources can be allocated according to their ecological function differences, making decisions more in line with actual needs.

Finally, fine-grained interpretation drives technological innovation and interdisciplinary integration in remote sensing-related fields. The high requirements of fine-grained analysis have forced the upgrading of the remote sensing technology system and promoted interdisciplinary collaborative innovation. To achieve sub-class differentiation of ground objects, sensor technology is constantly iterated (such as the number of bands of hyperspectral satellites increasing from dozens to hundreds), and algorithm models are continuously optimized (such as deep learning networks with attention mechanisms, which can focus on subtle features of ground objects); at the same time, it relies on interdisciplinary knowledge to build interpretation logic: plant physiology guides the interpretation of vegetation spectral features, urban planning theory constrains the judgment of building functions, ecological principles support the classification of wetland types, and so on. This cycle of “technical demand - disciplinary support - method innovation” not only helps remote sensing interpretation accuracy break through traditional bottlenecks, but also may form an integration paradigm of “remote sensing technology + domain science”, further expand the application boundary of remote sensing, and provide new research tools for agriculture, ecology, urban and other fields.

This paper systematically reviews the background, current situation and progress of fine-grained interpretation in the field of remote sensing, with a focus on the basic principles, key methods and specific application targets of fine-grained. This review focuses on summarizing different types of fine-grained remote sensing interpretation methods and conducts in-depth analyses of specific application scenarios. In addition, this paper also makes a profound summary of the specific challenges brought by the Fine-Grained interpretation method in the field of remote sensing applications, and explores the potential directions for future research at the same time.

2. Main Development Trends

2.1. Journal Distribution

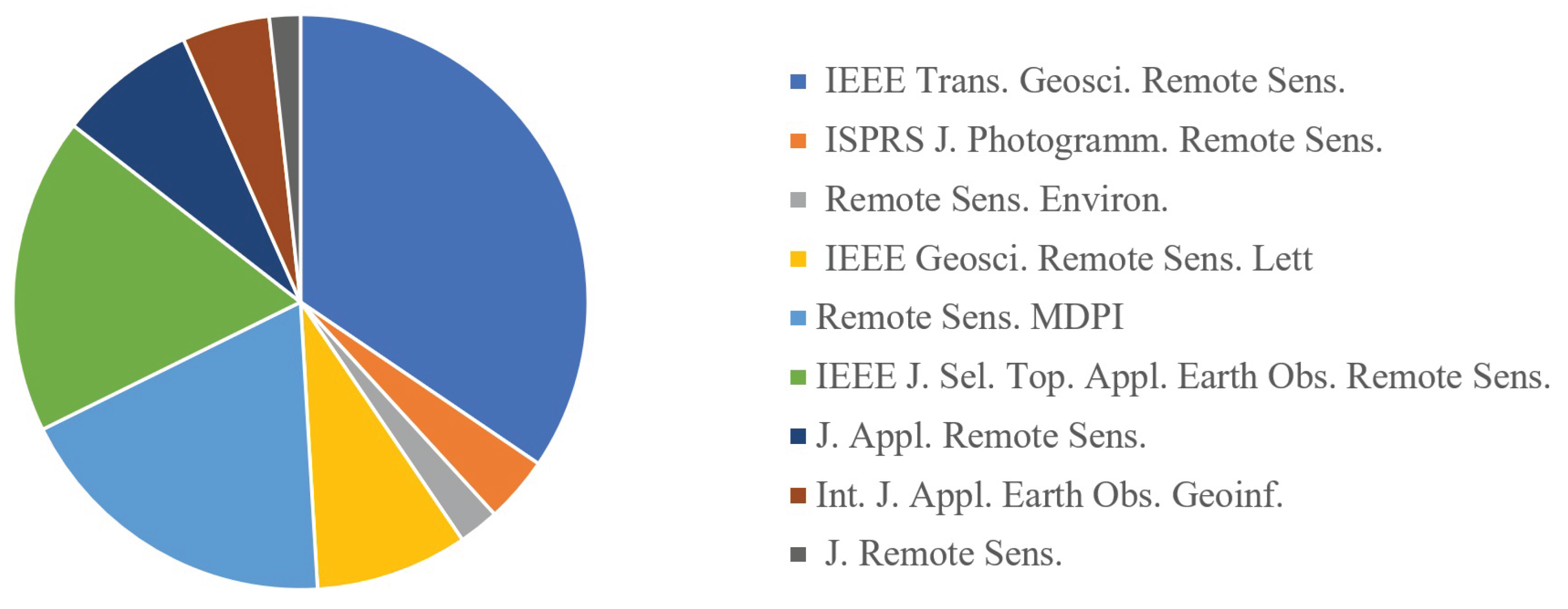

From a journal distribution perspective, top-tier remote sensing publications have become the primary platforms for papers focused fine-grained interpretation of remote sensing images. As shown in

Figure 2, between 2015 and 2025, research on fine-grained remote sensing image interpretation has been published widely across a number of high-impact journals in the geoscience and remote sensing domain. The distribution of articles shows several clear patterns:

Leading journals by output: with 455 published papers, IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing serves as the primary platform for theoretical and technological innovation in this field. Its research covers the core content of the entire fine-grained interpretation chain. It also acts as a key venue for publishing achievements related to theoretical breakthroughs and technological optimization. Remote Sensing (MDPI) has published 246 papers, focusing on multi-directional application exploration and methodological research in fine-grained interpretation. Additionally, it incorporates extensive dataset validation work, providing abundant practical case support for the field. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing has 235 published papers, with a core focus on the application and implementation of fine-grained interpretation technologies. Its research emphasizes the adaptive practice of technologies in specific scenarios and pays attention to fine-grained processing methods for satellite data.

IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters has published 113 papers, featuring short-format research. Its content focuses on single-point innovation and preliminary verification in fine-grained interpretation. It also rapidly disseminates cutting-edge innovative ideas in the field. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing has 103 published papers, emphasizing the practical verification of fine-grained interpretation methods, providing references for the engineering application of methods. With 65 published papers, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation conducts research from a geospatial information perspective. It focuses on publishing achievements related to the integration of remote sensing and geospatial relationships. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing has 49 published papers, focusing on the integration of photogrammetry and remote sensing technologies, reflecting the in-depth linkage between fine-grained interpretation and traditional surveying and mapping technologies. Remote Sensing of Environment has 30 published papers, focusing on the high-value application of fine-grained interpretation in environmental monitoring.

Trends observed: while IEEE and ISPRS outlets remain dominant, the substantial number of publications in IJAEOG and Remote Sensing (MDPI) reflects a move toward more application-oriented and open-access journals, increasing global visibility. High outputs in Remote Sensing (MDPI) and IEEE JSTARS suggest that fine-grained interpretation is increasingly intersecting with computer vision, data science, and earth observation applications. TGRS and RSE continue to publish core theoretical and algorithmic advances, while IJAEOG and MDPI’s Remote Sensing emphasize applied and case-driven studies.

2.2. Annually Published Articles

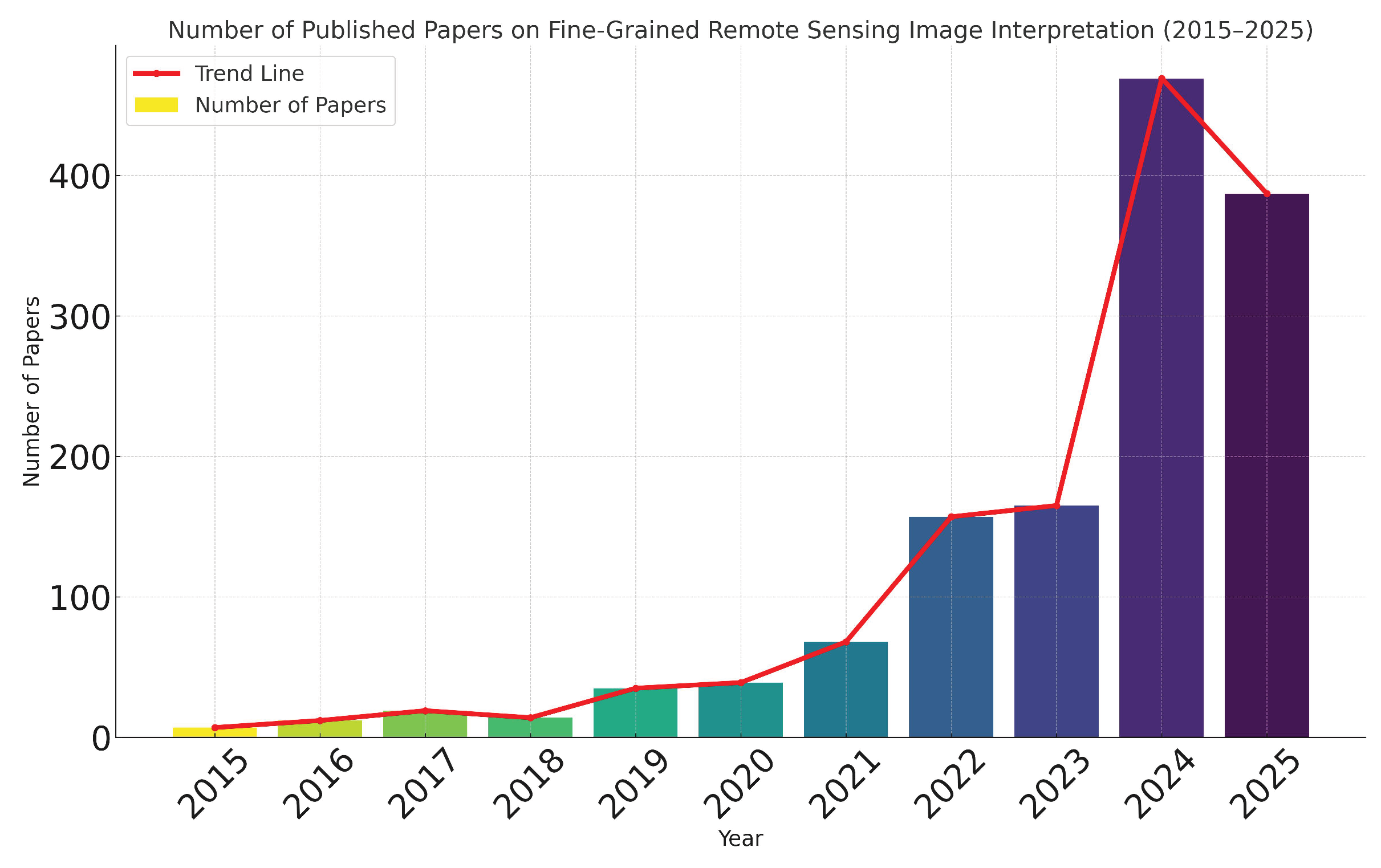

In

Figure 3, this graph adopts a combined form of “bar chart + line chart” to intuitively present the changes in the number of published papers in the field of fine-grained remote sensing image interpretation from 2015 to 2025. The horizontal axis represents the time dimension by year, and the vertical axis denotes the annual number of published papers. Among them, the bar chart corresponds to the actual number of papers published each year, while the red line chart is used to fit the overall trend. From the perspective of data distribution, during the period 2015-2023, the annual number of papers showed a steady growth trend with a relatively moderate growth rate, reflecting the gradual development of research in this field at the technical and theoretical levels during this stage. The year 2023 marked a key turning point, after which the number of papers entered a phase of rapid growth and reached a periodic peak in 2024, demonstrating a significant surge in the research enthusiasm for this field. Although the data in the 2025 bar chart is lower than that in 2024, the actual number of published papers in 2025 has not declined because the year 2025 has not yet ended.

In view of the current development trend, it is expected that fine-grained remote sensing image interpretation will remain a research hotspot in 2025 and the coming years. With the continuous development of multi-source data fusion, artificial intelligence (especially deep learning technology), the accuracy and efficiency of interpretation are expected to be further improved. Interdisciplinary research will also deepen, promoting remote sensing technology to move from macro observation to micro fine-grained interpretation and providing core technical support for the digital and intelligent transformation of various industries.

2.3. Keyword Co-Occurrence Network

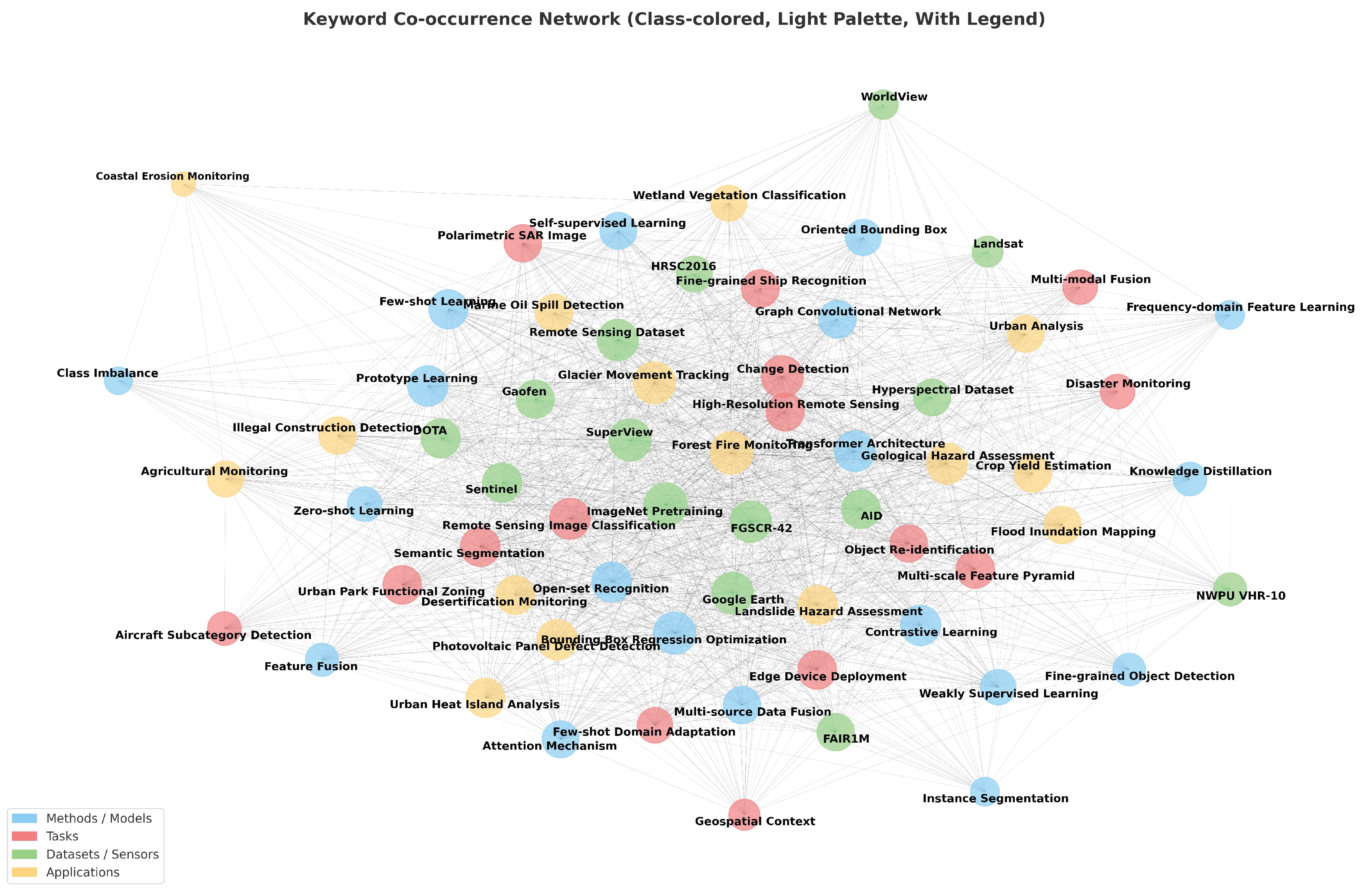

In

Figure 4, this is a keyword co-occurrence network diagram in the field of fine-grained remote sensing interpretation. Nodes of different colors represent different categories: blue for methods/models, red for tasks, green for datasets/sensors, and yellow for applications. The lines between nodes indicate the associations among keywords, while the size of each node reflects the importance or frequency of occurrence of the corresponding keyword. The diagram covers a wide range of keywords, spanning from data acquisition (e.g., satellite sensors such as WorldView and Landsat), processing methods (e.g., self-supervised learning and graph convolutional networks), tasks (e.g., fine-grained ship recognition and change detection) to multi-domain applications (e.g., agricultural monitoring and disaster monitoring). It presents the complex interconnections among various elements in this field.

In the methods/models category (blue nodes), the largest nodes correspond to deep learning-related technologies—specifically Transformer architecture and contrastive learning. These two keywords not only have the highest frequency of occurrence but also connect to the most other nodes (e.g., linking to “fine-grained object recognition” in tasks and “hyperspectral datasets” in data), becoming the core driving forces of technical innovation in the field.

In the tasks category (red nodes), “fine-grained object recognition” and “change detection” are the largest nodes. Their prominent size and dense connecting lines (e.g., linking to multiple processing methods and application scenarios) confirm that high-precision, detail-oriented interpretation tasks have become the primary research focus.

In the datasets/sensors category (green nodes), “hyperspectral datasets” and “high-resolution satellite data (e.g., WorldView)” are the largest nodes. Their frequent co-occurrence with methods and tasks reflects that multi-source, high-precision data has become the basic support for advancing research, with increasing attention paid to data quality and diversity.

In the applications category (yellow nodes), “agricultural monitoring” and “urban planning” are the most prominent nodes. Their strong associations with core tasks indicate that practical application in key fields is the main orientation of research, and the integration between technical methods and industry needs is becoming increasingly close.

Overall, the field of fine-grained remote sensing interpretation shows a trend of multi-dimensional coordinated development, with clear core nodes standing out in the keyword network. The cross-integration among these core nodes (e.g., Transformer connecting to hyperspectral datasets and fine-grained object recognition) is driving the field toward a more refined, intelligent, and application-oriented direction.

3. The Datasets for Fine-Grained Interpretation

3.1. Current Status of the Dataset

Remote sensing datasets play an extremely important role in the research of fine-grained remote sensing image interpretation. The current fine-grained remote sensing interpretation datasets can roughly be divided into three categories: pixel-level, target(object)-level, and scene-level.

Pixel-level datasets are mostly used for land cover classification and feature change detection, such as TREE [

10], Belgium Data [

11], and FUSU [

12]. The data sources are mostly airborne or ground systems (such as the LiCHy hyperspectral system). Emphasize the subtle distinctions in spectral dimensions, such as the spectral differences among land covers.

Object-level datasets mainly are constructed for individual targets such as ships, aircraft, and buildings, for example, HRSC2016 [

13], FGSCR-42 [

14], ShipRSImageNet [

15], and MFBFS [

16]. They are often high resolution (0.1–6m) remote sensing images. There are a large number of categories, emphasizing the subtle differences between similar categories (such as ship models, aircraft models). The data sources mainly include Google Earth, WorldView, GaoFen series satellites, etc.

Scene-level datasets, they have the widest coverage and are applied in remote sensing scene classification and retrieval, such as AID [

17], NWPU-RESISC45 [

18], PatternNet [

19], MLRSNet [

20], Million-AID [

21], and MEET [

22], etc. They are with wide resolution range (0.06–153 m). The sample size is large (ranging from tens of thousands to millions of images). The sources mainly include Google Earth, Bing Maps, Sentinel, OpenStreetMap, etc. In

Table 1, common datasets for fine-grained remote sensing image interpretation is summarized

Overall, the existing datasets have basically covered typical fine-grained objects and scenarios such as ships, aircraft, buildings, vegetation, and land use/cover, providing important support for related research.

3.2. Existing Deficiencies of Datasets

Despite substantial progress, current fine-grained datasets face several limitations.

High intra-class similarity: many fine-grained categories are visually very close, such as different ship or aircraft models, or subtle differences in tree species. This creates severe classification challenges, often leading to model confusion and reduced generalization ability.

Limited modality diversity: most datasets are dominated by optical imagery, whereas multi-modal data integrating SAR, LiDAR, and hyperspectral information are rare. This restricts the ability to fully exploit complementary signals and hampers progress in multi-sensor fusion research.

Geographic imbalance: the majority of existing datasets are constructed from images over China, the United States, and Europe. Large regions, particularly in Africa, South America, and parts of Southeast Asia, remain underrepresented, which reduces global applicability and introduces domain bias.

Annotation bottlenecks: fine-grained annotation requires expert knowledge and is highly time-consuming. As a result, dataset expansion is slow, and some benchmarks are at risk of being “over-saturated,” where algorithmic improvements may reflect overfitting to benchmark idiosyncrasies rather than true generalization.

3.3. Future Outlook of Fine-Grained Datasets

Future dataset development for fine-grained remote sensing interpretation is expected to follow several important directions:

1. Multi-modal integration. Most existing benchmarks are dominated by optical imagery, which captures rich spectral and spatial details but is often limited by weather, lighting, and occlusion. To address these challenges, constructing datasets that integrate optical, SAR, LiDAR, and hyperspectral modalities will be critical. SAR can penetrate clouds and provide structural backscatter features, LiDAR captures accurate 3D geometry and elevation information, and hyperspectral imaging offers detailed spectral signatures for material identification. By combining these complementary data sources, future datasets will enable models to recognize fine-grained categories even under challenging conditions (e.g., distinguishing tree species in dense canopies or identifying military targets under camouflage). Multi-modal benchmarks will also foster the development of fusion-based algorithms that better reflect real-world operational requirements.

2. Global coverage and domain diversity. Current datasets are geographically imbalanced, with most samples collected from regions such as China, the United States, and parts of Europe. This geographic bias restricts the generalization ability of models to unseen domains. Expanding datasets to cover diverse climates, cultures, and ecosystems—for instance, tropical rainforests in South America, arid deserts in Africa, or island regions in Oceania—will help mitigate domain bias. In addition, datasets should incorporate varying socio-economic environments (urban, rural, coastal, industrial) to ensure broader representativeness. Such global and cross-domain coverage will make fine-grained datasets more reliable for worldwide applications such as biodiversity monitoring, agricultural assessment, and disaster response.

3. Temporal and dynamic monitoring. Most existing benchmarks are static snapshots, which limits their use for monitoring changes over time. However, many fine-grained tasks are inherently dynamic, such as crop phenology, urban expansion, forest succession, and water resource fluctuation. Incorporating time-series data will allow researchers to capture temporal evolution and model long-term trends. For example, crop species might be indistinguishable at a single time point but reveal distinct spectral or structural patterns when tracked across multiple growth stages. Similarly, urban construction stages or seasonal flooding patterns can only be fully captured in temporal datasets. Building fine-grained time-series benchmarks will thus support more realistic monitoring and predictive modeling tasks.

4. Efficient annotation strategies. The creation of fine-grained datasets is constrained by the costly and time-consuming nature of expert annotations, especially when subtle distinctions (e.g., between aircraft variants or tree species) require domain expertise. To reduce labeling costs, future work should explore weakly supervised learning (using coarse labels or incomplete annotations), self-supervised learning (leveraging large-scale unlabeled imagery), and crowdsourcing platforms that engage non-experts under expert validation. Additionally, incorporating knowledge graphs and generative augmentation can help generate pseudo-labels or synthetic samples to expand datasets efficiently. These strategies will make it feasible to construct large-scale fine-grained benchmarks in a scalable and sustainable way.

5. Open-world and zero-shot benchmarks. In real-world applications, remote sensing systems often encounter novel classes that were not present in the training data. However, most current datasets assume closed-world settings, where the label space is fixed. Future benchmarks should explicitly support open-world recognition and zero-shot learning, where models can detect and reason about unseen categories by leveraging semantic embeddings, textual descriptions, or external knowledge bases. Initiatives such as OpenEarthSensing [

30] exemplify this trend, providing benchmarks that require models to generalize to novel classes and handle uncertain environments. Such benchmarks will be vital for practical deployments in tasks like disaster monitoring, where emergent phenomena (e.g., new building types or unusual environmental events) cannot be predefined.

In summary, fine-grained datasets at the pixel,object and scene levels have substantially advanced research in remote sensing interpretation, enriching both the scale and complexity of available benchmarks. Nevertheless, limitations such as high intra-class similarity, modality constraints, geographic imbalance, and annotation costs continue to hinder broader applicability. The future of fine-grained dataset construction will rely on multi-modality, global-scale diversity, temporal dynamics, efficient labeling strategies, and open-world settings, enabling more generalizable, intelligent, and application-ready solutions for remote sensing interpretation.

4. Methodology Taxonomy

Remote sensing image interpretation refers to the comprehensive technical process of analyzing, identifying, and interpreting the spectral, spatial, textural, and temporal characteristics of objects or phenomena in remote sensing images. Essentially, it serves as a “bridge” between remote sensing data and practical Earth observation applications. According to the granularity and objectives of information extraction, it can be divided into three core levels: pixel-level, object-level, and scene-level. Each level is interrelated yet has a clear differentiated positioning, while fine-grained interpretation is an in-depth extension of the demand for “subclass distinction” based on these levels.

Pixel-level interpretation, as the foundation of remote sensing interpretation, focuses on the semantic attribution of individual or local pixels. Its core tasks include pixel-level classification (e.g., distinguishing basic ground objects such as farmland, water bodies, and buildings) and semantic segmentation (delineating pixel-level boundaries of ground objects). Traditional methods rely on spectral features (e.g., the low near-infrared reflectance of water bodies) or simple texture features, which are suitable for macro ground object classification in medium- and low-resolution images (e.g., large-scale land use classification). With the development of high-resolution remote sensing technology, pixel-level interpretation has gradually advanced toward “fine-grained attribute distinction.” For example, it can distinguish different crop varieties in hyperspectral images and identify building roof materials in high-resolution optical images. This demand for “subclass segmentation under basic ground objects” has become the prototype of fine-grained interpretation at the pixel level.

Object-level interpretation centers on “discrete ground object targets” and requires both spatial localization of targets (e.g., bounding box annotation) and category judgment. Typical applications include ship detection, aircraft recognition, and building extraction. Traditional object-level interpretation focuses on “presence/absence” and “broad category distinction” (e.g., distinguishing “ships” from “aircraft”). However, practical scenarios often require more refined target classification: for instance, ships need to be distinguished into “frigates” and “destroyers,” aircraft into “passenger planes“ and “military transport planes,” and buildings into “historic protected buildings” and “ordinary residential buildings.” This type of “subclass identification under the same broad category” has driven object-level interpretation toward fine-grained development, which needs to overcome the technical challenge of “feature confusion between highly similar targets” (e.g., the similar outlines of different ship models).

Scene-level interpretation takes the “entire image scene” as the analysis unit. By integrating pixels, targets, and contextual information, it judges the overall semantics of the scene (e.g., “airport,” “port,” “urban residential area”) and supports regional-scale applications (e.g., urban functional zone division, disaster scene assessment). Traditional scene-level interpretation focuses on “broad scene category distinction” (e.g., distinguishing “forests” from “cities”). However, refined applications require more detailed scene subclass division: for example, “urban residential areas” need to be subdivided into “high-density high-rise communities” and “low-density villa areas,” “wetlands” into “swamp wetlands” and “tidal flat wetlands,” and “airports” into “military-civilian joint-use airports” and “civil airports.” This “functional/morphological subclass identification under broad scene categories” has become the core demand for fine-grained scene-level interpretation.

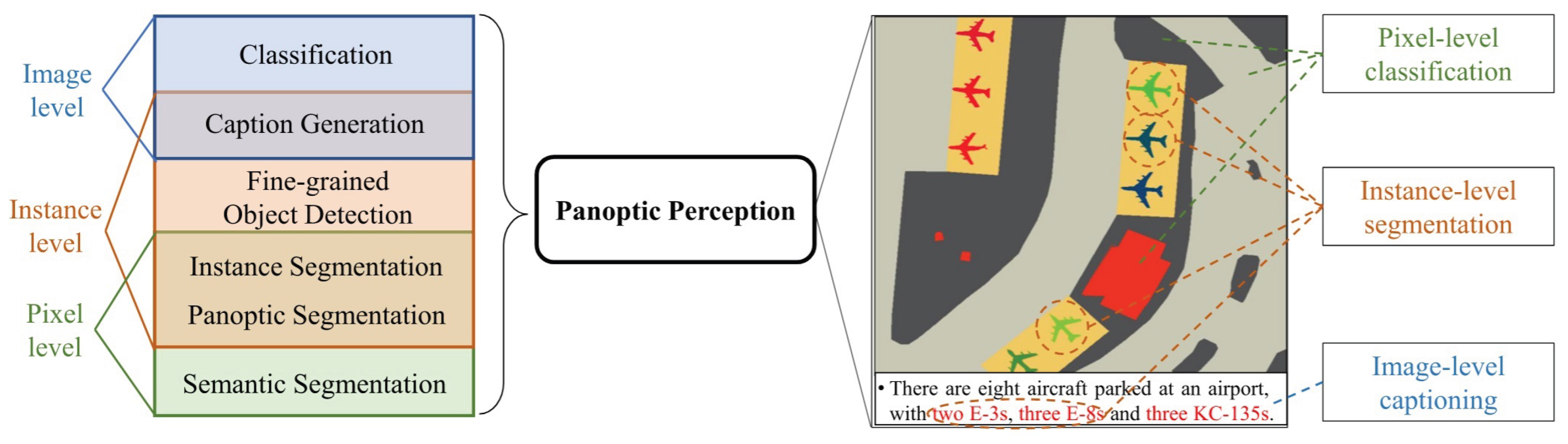

Figure 5.

Examples of Fine-Grained Interpretation at Different Levels [

37]. It proposed a new “panoptic perception” task, which showed the similar conception of image interpretation at different level. The instance-level is similar to the object-level in this paper.

Figure 5.

Examples of Fine-Grained Interpretation at Different Levels [

37]. It proposed a new “panoptic perception” task, which showed the similar conception of image interpretation at different level. The instance-level is similar to the object-level in this paper.

Traditional interpretation at the three aforementioned levels all have the limitation that “macro categorization cannot meet refined application needs”: pixel-level interpretation struggles to distinguish highly similar ground object subclasses (e.g., spectral confusion between different tree species), object-level interpretation fails to identify subdivided types under the same broad category (e.g., different equipment models), and scene-level interpretation cannot divide functionally differentiated scenes (e.g., farmland with different utilization types). Against this backdrop, fine-grained remote sensing image interpretation has emerged.

Fine-grained interpretation is not a new paradigm independent of the three levels, but a technical deepening centered on the goal of “subclass distinction” based on each level. Its core value lies in breaking the bottleneck of semantic ambiguity of ground objects in the same broad category. In the following sections, a comprehensive and in-depth review of the methodologies for these three levels of fine-grained interpretation will be presented.

4.1. Fine-Grained Pixel-Level Classification or Segmentation

The fine-grained remote sensing interpretation at the pixel level mainly includes the classification at the pixel level and the semantic segmentation of the remote sensing images. Generally, there are more studies on pixel-level classification for hyperspectral images and more on semantic segmentation for high-resolution multispectral images. In recent years, research based on spatial-spectral joint classification has become popular. Many classification applications also take advantage of the correlation between pixels and feature consistency, and the boundary between segmentation and classification has gradually blurred. Whether it is classification or segmentation, the challenges faced by pixel-level fine-grained interpretation mainly come from the similarity of the spectral characteristics of subclass pixels within a large category. Some subclasses are even almost indistinguishable in the spectral dimension and can only be distinguished by features such as spatial texture or consistency in the temporal dimension.

For example, as in

Figure 6 from GSFF dataset [

10], which originally has 12 different land-cover classes, containing 9 forest vegetation categories. However, we find that these nine types of vegetation are very difficult to distinguish because their spectra are all very similar. Distinguishing these nine types of vegetation is a typical fine-grained classification problem. In addition, in natural image research like ImageNet, this fine-grained pixel-level classification based on similar spectra is not common. This is one of the significant differences between fine-grained research in the field of remote sensing and traditional computer vision.

Common methods for fine-grained classifying or segmenting pixel-level remote sensing images include novel data representation methods, coarse-fine category relationship modeling method, multi-source data fusion method, advanced data annotation optimization methods, etc.

4.1.1. Novel Data Representation

This category of methods focus on breaking through the limitations of traditional and single features from spectrum through innovative feature extraction mechanisms, enabling more accurate capture of key information required for fine-grained classification (such as morphological structures, subtle texture differences, and edge textures etc.)

Spatial-Spectral Joint Representation. Spatial-spectral joint representation is one of the most popular methods in fine-grained classification at pixel-level. For examples, CASST [

39] establishes long-range mappings between spectral sequences (inter-band dependencies) and spatial features (neighboring pixel correlations) through a dual-branch Transformer and cross-attention; GRetNet [

40] introduces Gaussian multi-head attention to dynamically calibrate the saliency of spectral-spatial features, enhancing the discriminability of fine-grained differences (e.g., spectral peak shifts in closely related tree species); in [

41], CenterFormer focuses on the spatial-spectral features of target pixels through a central pixel enhancement mechanism to reduce background interference; E2TNet [

42] designs an efficient multi-granularity fusion module to balance global correlations of coarse/fine-grained spatial-spectral features; FGSCNN [

43] fuses high-level semantic features with fine-grained spatial details (e.g., edge textures) through an encoder-decoder architecture. Some studies do not simply jointly extract features in the spatial-spectral dimension, but introduce new spatial features such as gradients. For example, in [

44], it proposes G2C-Conv3D, which weighted combines traditional convolution with gradient centralized convolution to simultaneously capture pixel intensity semantic information and gradient changes, so that it supplements intensity features with gradient information to improve the model’s sensitivity to subtle structures such as edges and textures. Spatial-Spectral Joint Representation break the independent modeling of spectral and spatial features, capturing their intrinsic correlations via mechanisms like attention and Transformer to improve classification accuracy in complex scenes with fine-grained classes.

Morphological Representation. Different from spatial-spectral joint representation, there are also studies exploring new feature extraction methods that are completely different from convolution operations or transform operations to deal with fine-grained classification problems. In [

45], the authors propose SLA-NET, which combines morphological operators (erosion and dilation) with trainable structuring elements to extract fine morphological features (e.g., contours and compactness) of tree crowns; in [

46], it designs a dual-concentrated network (DNMF) that separates spectral and spatial information before fusing morphological features to enhance the robustness of tree species classification; morphFormer [

47] models the interaction between the structure and shape of trees/minerals through spectral-spatial morphological convolution and attention mechanisms. This kind of method focuses on the geometric morphology of objects (e.g., crown shape and texture distribution), compensating for the inability of traditional convolution to capture non-Euclidean features.

Edge and Area Representation. These methods Focus on edge continuity and regional integrity, addressing the fragmentation of classification results in traditional methods. In [

48], PatchOut adopts a Transformer-CNN hybrid architecture and a feature reconstruction module to retain large-scale regional features while restoring edge details, enabling patch-free fine land-cover classification; SSUN-CRF [

49] combines a spectral-spatial unified network with a fully connected conditional random field to smooth the edges of classification results and enhance regional consistency; Edge feature enhancement framework (EDFEM+ESM) [

50] improves the segmentation accuracy of mineral edges through multi-level feature fusion and edge supervision.

Advantages of Novel Data Representation mainly lies in: 1) Strong fine-grained feature capture: Innovative representation mechanisms accurately capture key information such as morphology, spatial-spectral correlations, gradient changes, and edge textures, significantly improving the discriminability of closely related categories (e.g., tree species and minerals). 2) Flexible model adaptability: Modular designs (e.g., morphological modules and attention modules) can be embedded into mainstream architectures like CNN and Transformer, compatible with diverse scene requirements. Their Limitations: High model complexity: Modules like multi-scale fusion and morphological transformation increase parameter scales and computational loads, imposing strict requirements on training data volume and hardware computing power.

4.1.2. Modeling Relationships Between Coarse and Fine Classes

This category of methods reduces the reliance of fine-grained tasks on annotated data by modeling the hierarchical relationship between coarse-grained categories (e.g., “vegetation”) and fine-grained categories (e.g., “oak” and “poplar”), using prior knowledge of coarse categories to guide fine category classification.

Typical methods are: in [

51], it uses GAN and DenseNet, where the generator learns coarse category distributions and the discriminator distinguishes fine category differences to achieve semi-supervised fine-grained classification; coarse-to-fine joint distribution alignment framework [

52] matches cross-domain coarse category distributions and then calibrates fine category feature differences through coupled VAE and adversarial learning; CSSD [

53] maps patch-level coarse-grained information to pixel-level fine category classification through central spectral self-distillation, solving the “granularity mismatch” problem; CPDIC [

54] framework aligns cross-domain coarse-fine category distributions using calibrated prototype loss to enhance domain adaptability; fine-grained multi-scale network [

55] combines superpixel post-processing to iteratively optimize fine category boundaries from coarse classification results; CFSSL [

56] performs coarse classification with a small number of labels, then uses high-confidence pseudo-labels to guide fine-grained classification of small categories.

Advantages of Modeling Relationships Between Coarse and Fine Classes: 1) High data efficiency: By reusing coarse category knowledge (e.g., spectral commonalities of “vegetation”), the demand for annotated samples for fine-grained categories (e.g., specific tree species) is reduced, making it particularly suitable for few-shot scenarios. 2) Strong generalization ability: Hierarchical modeling mitigates the interference of intra-fine-category variations (e.g., different growth stages of the same tree species) on classification, improving the model’s adaptability to scene changes. The limitations are: 1) Risk of hierarchical bias: Unreasonable definition of hierarchical relationships between coarse and fine categories (e.g., incorrectly classifying “shrubs” as a subclass of “arbor”) can lead to systematic bias in fine-grained classification. 2) Limited cross-domain adaptability: In scenes with severe spectral variation (e.g., vegetation in different seasons), differences in feature distribution between coarse and fine categories may disrupt hierarchical relationships, reducing classification accuracy.

4.1.3. Multi-Source Data Integration

The core of this category of methods is to break through the information dimensional limitations of single-source data by fusing complementary data sources (e.g., hyperspectral and LiDAR, remote sensing and crowdsourced data), thereby improving the robustness and accuracy of fine-grained classification.

The fusion of hyperspectral data with LiDAR data or hyperspectral data with geographic information data is one of the two most common methods for fine-grained classification based on data fusion. In [

57] proposes a coarse-to-fine high-order network that fuses spectral features of hyperspectral data and 3D structural information of LiDAR to capture multi-dimensional attributes of land cover through hierarchical modeling; in [

58], it designs a multi-scale and multi-directional feature extraction network that integrates spectral-spatial-height features of hyperspectral and LiDAR data to enhance category discriminability in complex scenes; In [

59], Sentinel-1 radar images (capturing microwave scattering characteristics of flooded areas) are combined with OpenStreetMap crowdsourced data (providing semantic labels of urban functional zones) to improve the accuracy of fine-grained urban flood detection.

Advantages of Multi-source Data Integration Methods: 1) Information complementarity: Multi-source data provide multi-dimensional information such as spectral, spatial, structural, and semantic, compensating for the lack of discriminability of single-source data in complex scenes (e.g., vegetation coverage and urban heterogeneous areas). It is applicable to diverse scenarios such as forests, cities, and hydrology, especially outstanding in distinguishing fine-grained subcategories (e.g., different tree species and flood-submerged buildings/roads). Their Limitations: Challenges of data heterogeneity: Differences in spatial resolution (e.g., 10m for hyperspectral vs. 1m for LiDAR), coordinate systems, and noise levels among different data sources require complex registration and preprocessing steps, increasing the difficulty of method implementation.

4.1.4. Advanced Data Annotation Strategies.

This category of methods focuses on reducing the reliance of fine-grained classification on large-scale accurately annotated data, optimizing annotation efficiency through strategies such as few-shot learning and semi-supervised annotation, and addressing the practical pain points of “high annotation cost and scarce samples”.

The most common approach is to introduce active learning or incremental learning methods into fine-grained remote sensing image classification. LPILC [

60] algorithm, based on linear programming, enables incremental learning with only a small number of new category samples without requiring original category data, adapting to dynamically updated classification needs; CSSD [

53] uses central spectral self-distillation, taking the model’s own predictions as pseudo-labels to reduce dependence on manual annotation; CFSSL [

56] screens high-confidence pseudo-labels through “breaking-tie” sampling (BT criterion) to reduce the impact of noisy annotations on the model.

The Advantages of Advanced Data Annotation Strategies are: 1) Significantly reduced annotation cost: these strategies can reduce manual annotation, making them particularly suitable for scenarios requiring professional knowledge for annotation, such as hyperspectral data. Their Limitations are: The performance of few-shot/incremental learning highly depends on the robustness of pre-trained models. If the initial model has biases (e.g., a tendency to misclassify certain categories), it will continuously affect the classification of new categories.

4.2. Fine-Grained Object-Level Detection

In the context of remote sensing, fine-grained object detection refers to the task of not only identifying major target categories such as vehicles, airplanes, and ships, but also distinguishing their more detailed subcategories. As illustrated in the

Figure 7, conventional object detection merely recognizes broad categories like Vehicle, Airplane, or Ship. In contrast, fine-grained object detection is able to further differentiate vehicles into Van, Small Car, and Other Vehicle; airplanes into A330, A321, A220, and Boeing 737; and ships into Tugboat and Dry Cargo Ship, among others. This enables a more precise and detailed recognition and classification of targets in remote sensing imagery.

Object detection, a core task in computer vision, aims to localize and classify objects in images. It has mainly evolved into two dominant paradigms: two-stage detectors and one-stage detectors, each with distinct architectural designs and trade-offs between accuracy and speed. Most of the target detection methods in the field of remote sensing are derived from these two types of methods in the field of computer vision. The following subsections will respectively review and summarize the improvements of the two types of methods (two-stage and one-stage) for fine-grained object detection tasks.

4.2.1. Two-Stage Detectors

Two-stage methods separate object detection into two sequential steps: (1) generating region proposals (potential object locations) and (2) classifying these proposals and refining their bounding boxes. This modular design typically achieves higher accuracy but at the cost of computational complexity.

R-CNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks) [

62] introduced the first two-stage framework. It uses selective search to generate region proposals, extracts features via CNNs, and applies SVMs for classification. Despite its pioneering nature, redundant computations make it inefficient. Fast R-CNN [

63] addressed R-CNN’s inefficiencies by sharing convolutional features across proposals, using a RoI (Region of Interest) pooling layer to unify feature sizes, and integrating classification and regression into a single network. Faster R-CNN [

64] revolutionized the field by replacing selective search with a Region Proposal Network (RPN), a fully convolutional network that predicts proposals directly from feature maps. This made two-stage detection end-to-end trainable and significantly faster. Mask R-CNN [

65] extended Faster R-CNN by adding a branch for instance segmentation, demonstrating the flexibility of two-stage architectures in handling complex tasks beyond detection. Cascade R-CNN [

66] improved bounding box regression by iteratively refining proposals with increasing IoU thresholds, addressing the mismatch between training and inference in standard two-stage methods.

R-CNN-based methods rely on a two-stage framework to address the core challenge of distinguishing highly similar targets (e.g., aircraft subtypes, ship models) in remote sensing images. In the research of fine-grained object detection, the two-stage structure is more popular than the one-stage structure. Two-stage object detection architectures can be further decomposed into a feature extraction backbone (Backbone) with a feature pyramid network (FPN), a region proposal network (RPN) for candidate regions, a region of interest alignment module (RoIAlign) for precise feature mapping, and task-specific heads for object classification (Cls), bounding box regression (Reg), and optional mask prediction (Mask Branch).

Table 2 summarizes the improvements of fine-grained object detection on these components. Below is a detailed analysis of their improvements with different methods.

Figure 8.

Prototypical Contrast Learning [

79].

Figure 8.

Prototypical Contrast Learning [

79].

Contrastive Learning. This subcategory focuses on optimizing the feature space of highly similar targets through inter-sample contrast to amplify inter-class differences and reduce intra-class variations. Its core logic is to construct positive/negative sample pairs and use contrastive loss to guide the model in learning discriminative features, which is particularly effective for scenarios where visual similarity leads to feature confusion.

Existing studies in this subcategory (Contrastive Learning) mainly include: To address insufficient feature discrimination caused by long-tailed distributions, [

61] proposed PCLDet, which builds a category prototype library to store feature centers of targets (e.g., ships, aircraft) and introduces Prototypical Contrastive Loss (ProtoCL) to maximize inter-class distances while minimizing intra-class distances. A Class-Balanced Sampler (CBS) further balances sample distribution, ensuring that rare subtypes receive sufficient attention. For the problem of intra-class diversity in fine-grained aircraft detection, [

72] designed an Instance Switching-Based Contrastive Learning method. The Contrastive Learning Module (CLM) uses InfoNCE+ loss to expand the feature gap between aircraft subtypes (e.g., passenger aircraft models), while the Refined Instance Switching (ReIS) module mitigates class imbalance and iteratively optimizes features of discriminative regions (e.g., wings, engines). For oriented highly similar targets (e.g., ships), [

79] combined Oriented R-CNN (ORCNN) with Adaptive Prototypical Contrastive Learning (APCL). The Spatial-Aligned FPN (SAFPN) solves the spatial misalignment issue of traditional FPN, providing high-quality feature inputs for contrastive learning, and significantly improves the separability of features for ship subtypes (e.g., frigates vs. destroyers) on datasets such as FGSD and ShipRSImageNet. Unknown ship detection via memory bank and uncertainty reduction [

80] proposed a method that uses a Class-Balanced Proposal Sampler (CBPS) to balance sample learning and a Fine-Grained memory bank-based Contrastive Learning (FGCL) strategy to separate known/unknown ships. The Uncertainty-Aware Unknown Learner (UAUL) module reduces prediction uncertainty, solving the misjudgment of unknown highly similar ships (e.g., new military ships).

Knowledge Distillation. This subcategory aims to balance detection accuracy and model efficiency by transferring fine-grained knowledge from complex “teacher models” to lightweight “student models.” It has expanded from traditional multi-model distillation to self-distillation, enabling knowledge reuse within a single model and adapting to scenarios such as lightweight deployment and few-shot learning.

The technical evolution of this subcategory (Knowledge Distillation) is reflected in three directions: Multi-teacher knowledge distillation for accuracy-efficiency balance [

71] used oriented R-CNN as the first teacher to locate vehicles/ships and Coarse-to-Fine Object Recognition Network (CF-ORNet) as the second teacher for fine-grained recognition. By distilling knowledge from both teachers into a student model and combining filter grafting, the model achieves high accuracy on high-resolution remote sensing images while reducing computational costs. Decoupled distillation for lightweight underwater detection [

81] proposed the Prototypical Contrastive Distillation (PCD) framework, which uses R-CNN as the teacher model to transfer fine-grained knowledge of underwater targets (e.g., submersibles) via prototypical contrastive learning. The decoupled distillation mechanism allows the student model to focus on discriminative features, and contrastive loss enhances semantic structural attributes, improving the robustness of lightweight models in underwater environments. Self-distillation for few-shot scenarios [

82] proposed Decoupled Self-Distillation for fine-grained few-shot detection. The model uses its “high-confidence branch” as an implicit teacher and “low-confidence branch” as a student to transfer knowledge of rare highly similar subtypes (e.g., rare aircraft models). Combined with progressive prototype calibration, this method addresses the problem of insufficient knowledge transfer due to limited data in few-shot scenarios.

Hierarchical Feature Optimization and Highly Similar Feature Mining (HFOSFM). This subcategory follows the logic of “from low-level feature purification to high-level feature fusion” to iteratively improve feature quality, with the ultimate goal of mining subtle discriminative features of highly similar targets. Low-level optimization focuses on eliminating noise (e.g., background interference, posture misalignment), while high-level optimization emphasizes integrating semantic information to enhance feature completeness.

Key innovations across these HFOSFM studies include: Low-level noise filtering and high-level feature matching [

73] proposed PETDet, which uses the Quality-Oriented Proposal Network (QOPN) to generate high-quality oriented proposals (low-level purification) and the Bilinear Channel Fusion Network (BCFN) to extract independent discriminative features for proposals (high-level refinement). Adaptive Recognition Loss (ARL) further guides the R-CNN head to focus on high-quality proposals, solving the mismatch between proposals and features for highly similar targets. Multi-domain feature fusion and semantic association construction [

70] proposed DIMA, which synchronously learns image and frequency-domain features via the Frequency-Aware Representation Supplement (FARS) mechanism (low-level detail enhancement) and builds coarse-fine feature relationships using the Hierarchical Classification Paradigm (HCP) (high-level semantic integration). This approach effectively amplifies structural differences between highly similar samples (e.g., ships of different tonnages). For oriented targets (e.g., rotating ships), [

74] proposed SFRNet, which uses the Spatial-Channel Transformer (SC-Former) to correct feature misalignment caused by posture variations (low-level spatial interaction) and the Oriented Transformer (OR-Former) to encode rotation angles (high-level semantic supplementation). This ensures that local differences (e.g., wing angles of tilted aircraft) are fully captured.

Category Relationship Modeling and Similarity Measurement Optimization (CRMSMO). This subcategory explicitly models intrinsic relationships between categories (e.g., hierarchical, structural, or functional relationships) to optimize similarity measurement logic, addressing the issue where traditional methods fail to distinguish highly similar targets due to over-reliance on visual features.

Representative studies of CRMSMO are: Semantic decoupling and anchor matching optimization [

76] proposed a method for fine-grained ship detection that decouples classification and regression features using a polarized feature focusing module and selects high-quality anchors via adaptive harmony anchor labeling. By optimizing the matching between anchors and category features, it improves the localization accuracy of highly similar ships. Hierarchical relationship constraint and feature distance expansion [

77] proposed HMS-Net, which reinforces features at different semantic levels (e.g., ship contours vs. local components) and uses hierarchical relationship constraint loss to model the semantic hierarchy of ship subtypes (e.g., destroyer models). This explicitly expands the feature distance between highly similar subcategories. Invariant structural feature extraction via graph modeling [

78] proposed Invariant Structure Representation, which uses the Graph Focusing Process (GFP) module to extract invariant structural features (e.g., cross-shaped aircraft, rectangular vehicles) based on graph convolution. The Graph Aggregation Network (GAN) updates node weights to enhance structural feature expression, enabling the model to distinguish visually similar targets by their inherent structural relationships. Shape-aware modeling for large aspect ratio targets [

69] addressed the high similarity and large aspect ratio of ships in high-resolution satellite images by designing a Shape-Aware Feature Learning module to alleviate feature alignment bias and a Shape-Aware Instance Switching module to balance category distribution. This ensures sufficient learning of rare ship subtypes (e.g., special operation ships).

Multi-Source Feature Fusion and Context Utilization. This subcategory compensates for the lack of discriminative information caused by visual similarity by fusing multi-modal data (e.g., RGB, multispectral, LiDAR) and leveraging contextual relationships. It is particularly effective for scenarios where single-modal features are insufficient to distinguish highly similar targets (e.g., street tree subtypes). For example, in [

68], it proposed a multisource region attention network that fuses RGB, multispectral, and LiDAR data. A multisource region attention module assigns weights to features of highly similar street tree subtypes, using multi-modal differences (e.g., spectral reflectance, elevation information) to supplement the information gap caused by visual similarity. This approach significantly improves the fine-grained classification accuracy of street trees in remote sensing imagery. Few-shot aircraft detection via cross-modal knowledge guidance [

83] proposed the TEMO method, which introduced text-modal descriptions of aircraft and fused text-visual features via a cross-modal assembly module. This reduces confusion between new categories and known similar aircraft, enabling fine-grained recognition in few-shot scenarios based on the R-CNN two-stage framework.

4.2.2. One-Stage Detectors

Single-stage detectors (such as the YOLO series) omit the separation steps of candidate region generation and subsequent classification, and directly perform category prediction and bounding box regression on the feature map. This end-to-end structure significantly reduces model complexity and inference latency, thereby enabling real-time detection capabilities. Although early single-stage methods generally lagged behind two-stage detectors in terms of accuracy, YOLO et al. have made many improvements and achieved significant enhancements in aspects such as network structure optimization, loss function improvement, and the introduction of feature enhancement modules.

YOLO (You Only Look Once) [

84] pioneered one-stage detection by treating object detection as a regression task. It divides the image into a grid, with each grid cell predicting bounding boxes and class probabilities, enabling real-time performance. SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector) [

85] introduced multi-scale feature maps to detect objects of varying sizes, using default bounding boxes (anchors) at different layers to improve small object detection. RetinaNet [

86] addressed the class imbalance issue in one-stage detectors with Focal Loss, a modified cross-entropy loss that down-weights easy background examples. This closed the accuracy gap with two-stage methods. YOLOv3 [

87] enhanced the original YOLO with multi-scale prediction, a more efficient backbone (Darknet-53), and better class prediction, balancing speed and accuracy. EfficientDet [

88] optimized both accuracy and efficiency through compound scaling (co-scaling depth, width, and resolution) and a weighted bi-directional feature pyramid network (BiFPN), achieving state-of-the-art results on COCO. YOLOv7 [

89] introduced trainable bag-of-freebies (e.g., ELAN architecture, model scaling) and bag-of-specials (e.g., reparameterization) to boost performance, outperforming previous YOLO variants and other one-stage detectors on speed-accuracy curves.

Methods based on YOLO can be structurally decomposed into Backbone, Neck, and Head.

Table 3 summarizes the improvements of existing fine-grained object detection approaches with respect to these decomposed components.

These methods can also be broadly categorized into four groups: data and input augmentation-driven, attention and feature fusion-driven, discriminative learning and task design-driven, and optimization and post-processing-driven. Each direction addresses different technical aspects, yet they share the common goal of enhancing the ability to distinguish visually similar targets and to improve the detection of small objects in complex remote sensing scenes.

Data and Input Augmentation-Driven Methods. This category mainly focuses on enriching input data and sample representation, alleviating challenges of limited training samples and class imbalance in remote sensing. For instance, the improved YOLOv7-Tiny [

90] applies multi-scale/rotation augmentation to expand input sample diversity; Lightweight FE-YOLO [

91] optimizes input by preprocessing input data to highlight fine-grained features of small targets; YOLOv8 (G-HG) [

92], adjusts input feature resolution to match multi-scale remote sensing targets; YOLO-RS [

93] adopts context-aware input sampling to focus on crop fine-grained regions; YOLOX-DW [

94] applies adaptive sampling to balance the distribution of fine-grained classes in input data . Moreover, DETet [

95] and MFL [

96] explore image degradation recovery and super-resolution enhancement, offering new approaches to restore fine details in low-quality remote sensing images. These studies highlight that input-level improvements not only enhance robustness but also provide stronger foundations for fine-grained discrimination.

Attention and Feature Fusion-Driven Methods. Methods in this category emphasize enhancing discriminative feature representations by leveraging attention mechanisms and multi-scale fusion. For example, FGA-YOLO [

97] and SR-YOLO [

98] combine global multi-scale modules, bidirectional FPNs, and super-resolution convolutions to strengthen fine-grained representation of aircraft and UAV targets. WDFA-YOLOX [

99] and YOLOv5+CAM [

100] address SAR feature loss and wide-area vehicle detection through wavelet-based compensation and attention mechanisms. IF-YOLO [

101] and FiFoNet [

102] improve feature pyramid and fusion strategies to preserve small-object features and suppress background noise. These works demonstrate that precise feature modeling under complex backgrounds and scale variations is crucial for fine-grained detection.

Discriminative Learning and Task Design-Driven Methods. This research line emphasizes introducing additional discriminative constraints or multi-task mechanisms to improve the separation of visually similar categories. FD-YOLOv8 [

104] captures subtle differences in aircraft through local detail modules and focus modulation mechanisms. Related-YOLO [

103] leverages relational attention, hierarchical clustering, and deformable convolutions to model structural relations between ship components. GTDet [

105] enhances classification-regression consistency for oriented objects using optimal transport-based label assignment and decoupled angle prediction. MFL [

96] builds a closed-loop between detection and super-resolution, guiding degraded images to recover discriminative details. Overall, these methods contribute discriminative signals by focusing on local part modeling, relational learning, and multi-task integration.

Optimization and Post-Processing-Driven Methods. This category centers on loss function design and post-processing optimization, improving adaptation to fine-grained targets during both training and inference. WDFA-YOLOX [

99] and SR-YOLO [

98] introduce novel regression losses (Chebyshev distance-IoU and normalized Wasserstein distance) to improve bounding box localization for small objects. GTDet [

105] applies optimal transport-based assignment to address the scarcity of positive samples for oriented objects with large aspect ratios. SA-YOLO [

107] dynamically adjusts class weights with adaptive loss functions to mitigate bias from data imbalance. DETet [

95] employs iterative filtering during post-processing to suppress noise and false positives in night-time UAV imagery. These strategies demonstrate that careful optimization and post-processing not only stabilize training but also ensure the preservation of small and fine-grained targets during inference.

Overall, YOLO-based fine-grained detection research in remote sensing has established a comprehensive improvement pathway spanning input augmentation, feature modeling, discriminative learning, and optimization strategies. Data and input enhancements improve baseline robustness, attention and feature fusion strengthen discriminative representations, discriminative learning and task design introduce novel supervision signals, and optimization and post-processing ensure stability and reliability across stages. Future trends are expected to further integrate these directions, such as combining input augmentation with discriminative learning, or unifying feature modeling and optimization strategies into an end-to-end framework, to comprehensively improve fine-grained detection performance in remote sensing.

4.2.3. Other Methods for Fine-Grained Object Detection

In the field of fine-grained object detection in remote sensing, aside from YOLO and RCNN-based methods, existing studies can be broadly categorized into four classes: methods based on Transformer/DETR, classification/recognition networks, customized approaches for special modalities or scenarios, and graph-based or structural feature modeling methods. These approaches address challenges such as category ambiguity, feature indistinctness, and complex scene conditions from different perspectives, including global feature modeling, fine-grained feature optimization, environment-specific adaptation, and structural information exploitation.

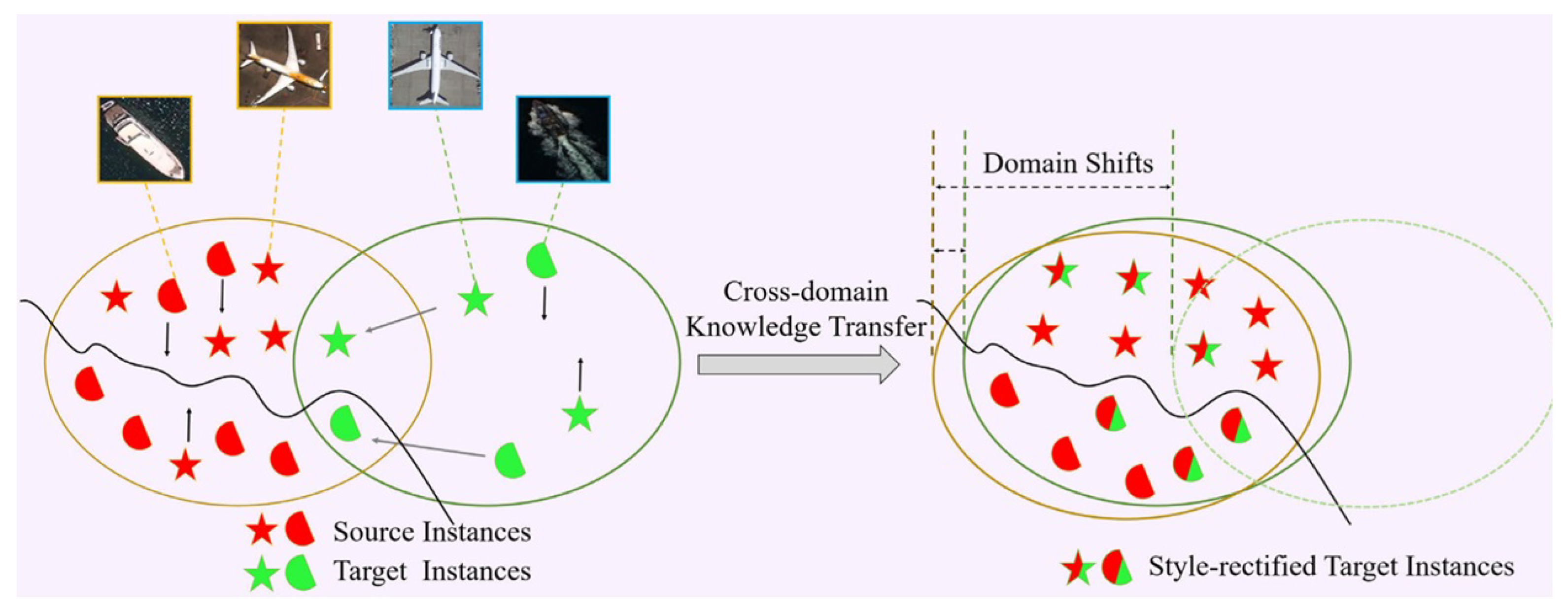

Figure 9.

FSDA-DETR [

108]. Domain shift is observed between the source and target domains when the given target-domain data is scarce.

Figure 9.

FSDA-DETR [

108]. Domain shift is observed between the source and target domains when the given target-domain data is scarce.

Transformer/DETR-Based Methods. Transformer and DETR-based methods leverage self-attention mechanisms to model global feature dependencies, enabling the capture of fine-grained target relationships across the entire image and supporting end-to-end detection. Typical studies include: FSDA-DETR [

108] employs cross-domain style alignment and category-aware feature calibration to achieve effective adaptation in optical-SAR cross-domain few-shot scenarios; GMODet [

109] integrates region-aware and semantic-spatial progressive interaction modules within the DETR framework to capture spatio-temporal correlations of ground-moving targets, enabling efficient detection in large-scale remote sensing images; InterMamba [

106] combines cross-visual selective scanning with global attention and user interaction feedback to optimize detection and annotation in dense scenes, enhancing discriminability in crowded environments.

CNN-Based Feature Interaction and Classification (Non-YOLO/RCNN). This category primarily focuses on fine-grained object classification or recognition. Most methods do not involve explicit detection or YOLO/RCNN structures(without localization modules), but rely on feature optimization, data augmentation, and feature purification to improve category discriminability. A few approaches (Context-Aware method [

110]) incorporate lightweight localization modules in addition to classification. Representative works include [

111], which combines CNN features with natural language attributes for zero-shot recognition; [

112], which uses region-aware instance modeling and adversarial generation to mitigate inter-class similarity; EFM-Net [

113], which leverages feature purification and data augmentation to enhance fine-grained characteristics; [

114], integrating weak and strong features to iteratively optimize discriminative regions in low-resolution images; [

115], proposing a coarse-to-fine hierarchical framework for urban village classification; and [

116], which uses feature decoupling and pyramid transformer encoding to distinguish visually similar targets in UAV videos. Overall, these methods emphasize enhancing classification capability under limited or ambiguous feature conditions.

Customized Methods for Special Modalities or Scenarios. These methods target fine-grained object detection under specific modalities (e.g., thermal infrared, underwater) or challenging scenarios (e.g., low-light, night-time), optimizing feature extraction and localization through specialized modules. Typical studies include: U-MATIR [

117] constructs a multi-angle thermal infrared dataset and leverages heterogeneous label spaces with hybrid view cascade modules to enable efficient detection of thermal infrared targets; DEDet [

95] employs pixel-level exposure correction and background noise filtering to improve feature quality and detection performance under low-light UAV imagery; PCD method [

81] uses prototype contrastive learning and decoupled distillation to transfer features and lighten models for underwater fine-grained targets, enhancing overall detection performance.

Graph-Based or Structural Feature Modeling Methods. Graph-based methods model structural relationships among target components, reinforcing classification and localization through structural consistency.Typical studies include: GFA-Net [

78] employs a graph-focused aggregation network to model structural features and node relations, achieving precise detection of structurally deformed targets; In [

118], it integrates geospatial priors with frequency-domain analysis to infer the distribution and class relationships of aircraft in large-scale SAR images, enabling efficient localization.

Overall, the three categories of fine-grained object detection methods form a complementary technical system targeting the core challenge of “high inter-class similarity”: R-CNN-based methods mainly achieve high precision through specialized technical paths (contrastive learning, knowledge distillation, hierarchical feature optimization) and are suitable for complex scenarios (few-shot, unknown categories); YOLO-based methods mainly prioritize efficiency via multi-scale fusion and attention mechanisms, making them ideal for real-time scenarios (UAV, SAR); Other methods break through traditional frameworks to address special scenarios (cross-domain, nighttime, zero-shot), providing innovative supplements.

4.3. Fine-Grained Scene-Level Recognition

Fine-grained scene-level recognition is playing an increasingly important role in remote sensing applications, where distinguishing subtle differences between visually similar scenes has become more complex and challenging. Many studies on scene understanding in remote sensing images draw on methods and models from the field of computer vision. In the field of computer vision, image scene understanding generally follows two fundamental paradigms: bottom-up and top-down approaches.

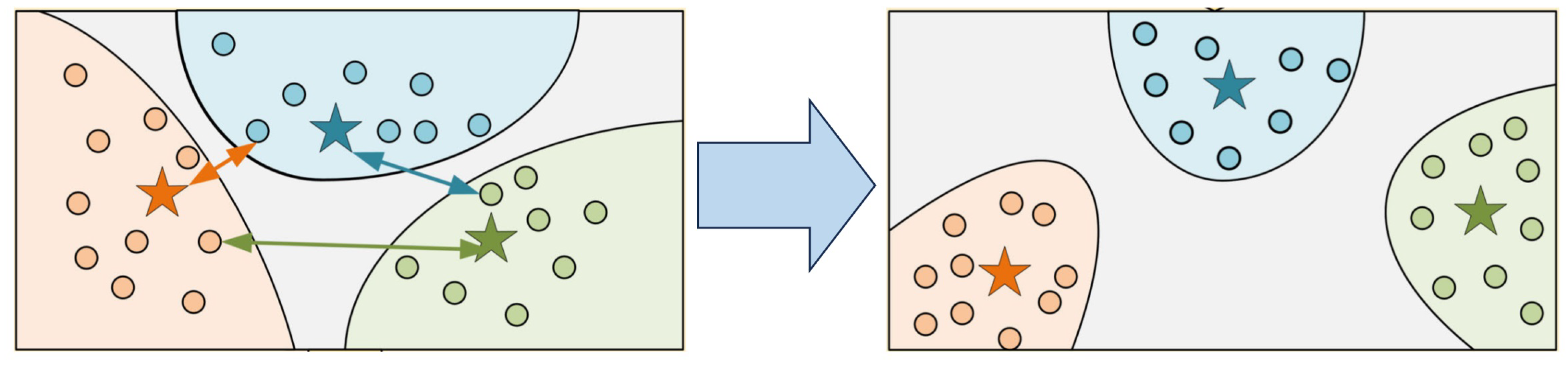

Bottom-up methods start from pixels and low-level features, progressively extracting textures, shapes, and spectral information, and then aggregating them into high-level semantics through deep neural networks, as in

Figure 10. Their advantages lie in being data-driven, well-suited for large-scale imagery, and capable of automatic feature learning with good transferability. However, they often lack high-level semantic constraints, making them vulnerable to intra-class variability and complex backgrounds, which may lead to insufficient semantic interpretability.

Top-down methods, in contrast, begin with task objectives or prior knowledge, employing geographic knowledge graphs, ontologies, or semantic rules to guide and constrain the interpretation of low-level features, as in

Figure 10. These approaches have the strengths of semantic clarity and interpretability, aligning more closely with human cognition. Their limitations, however, include dependence on high-quality prior knowledge, high construction costs, and limited scalability in large-scale automated tasks.

In terms of research trends, bottom-up methods dominate the current literature. In fine-grained remote sensing scene understanding in particular, most studies rely on multi-scale feature modeling, attention mechanisms, convolutional neural networks, and Transformer architectures to capture subtle inter-class differences through hierarchical abstraction. These approaches are well-suited to large-scale data-driven training and have therefore become the mainstream. By contrast, top-down methods are mainly explored in knowledge-based scene parsing, cross-modal alignment, and zero-shot learning, and remain relatively limited in number, though they show promise for enhancing semantic interpretability and cross-domain generalization.

In summary, fine-grained remote sensing scene understanding is currently almost exclusively driven by bottom-up feature learning approaches, while top-down methods remain at an exploratory stage. This paper mainly reviews two studies on the scene level of remote sensing images: scene classification and image retrieval. Most of them are bottom-up fine-grained image recognition or understanding.

4.3.1. Scene Classification

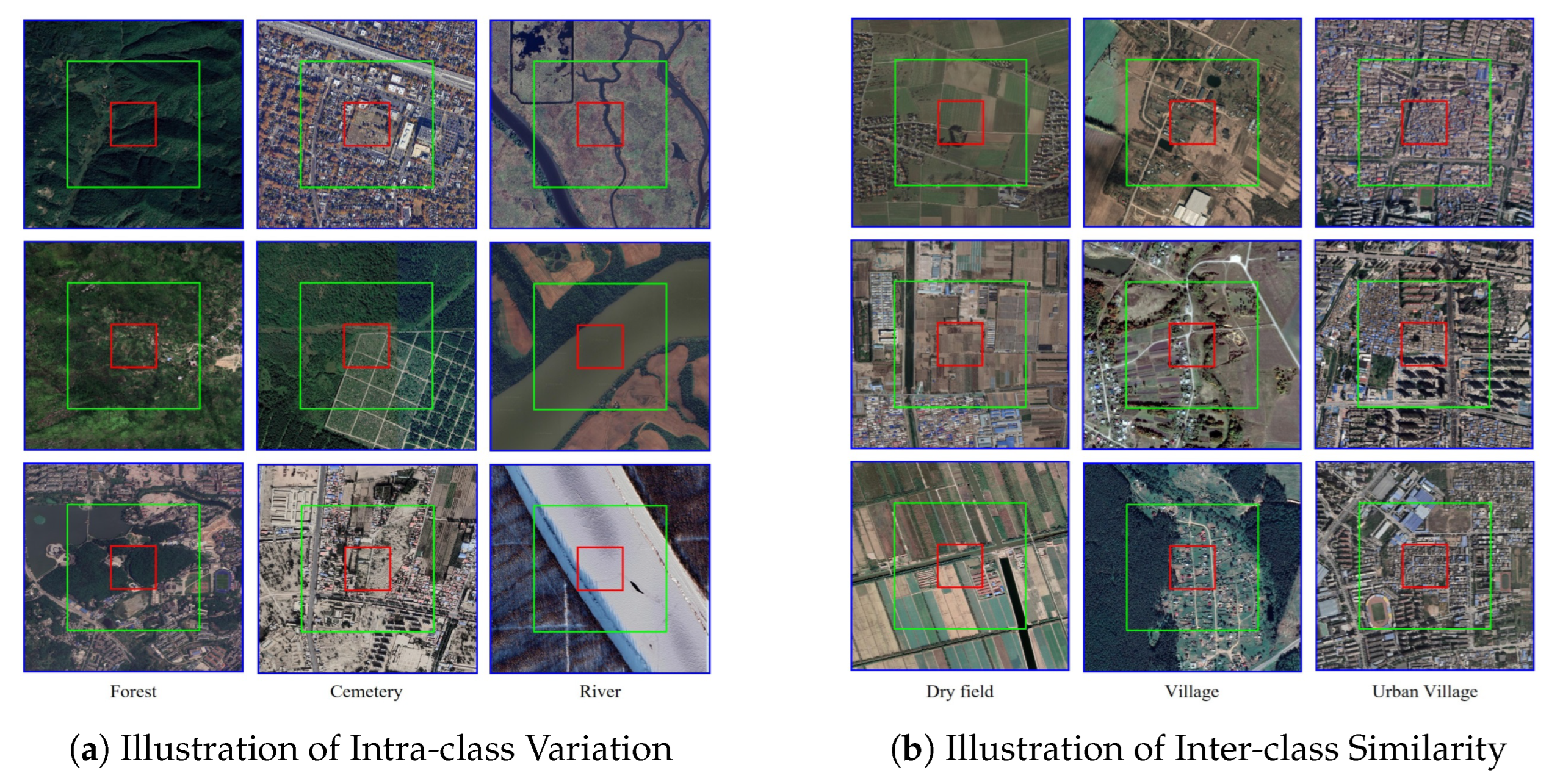

The core challenges of fine-grained remote sensing image scene classification converge on four dimensions: feature confusion caused by “large intra-class variation and high inter-class similarity”, data constraints from “high annotation costs and scarce samples”, modeling imbalance between “local details and global semantics”, and domain shift across “sensors and regions”. The studies can be categorized into four core classes and one category of scattered research according to technical objectives and methodological logic.

Multi-Granularity Feature Modeling. It is one of the core approaches to resolving “Intra-Class Variation-Inter-Class Similarity”. This category represents the fundamental technical direction for fine-grained classification. Its core logic involves mining multi-dimensional features (e.g., “local-global”, “low-high resolution”, “high-low frequency”) to capture subtle discriminative information between subclasses, thereby addressing the pain points of “large intra-class variation and high inter-class similarity” in remote sensing scenes. Its technical evolution has progressed from single-granularity enhancement to multi-granularity collaborative decoupling, which can be further divided into two technical branches:

1) Multi-Level Feature Fusion and Semantic Collaboration. This branch strengthens the transmission and discriminability of fine-grained semantics through feature interaction across different network levels. Typical studies include: [

120] proposed the MGML-FENet framework, innovatively designing a Channel-Separate Feature Generator (CS-FG) to extract multi-granularity local features (e.g., building edge textures, crop ridge structures) at different network levels; [

121] proposed MGSN, pioneering a coarse-grained guiding fine-grained bidirectional mechanism. Its MGSL module enables simultaneous learning of global scene structures and local details; [

122] proposed the MG-CAP framework: it generates multi-granularity features via progressive image cropping, and uses Gaussian covariance matrices (replacing traditional CNN features) to capture feature high-order correlations.

2) Frequency/Scale Decoupling and Enhancement. Typical studies include: Targeting the characteristic of remote sensing images where “high-frequency details are separated from low-frequency structures”, this branch strengthens the independence and discriminability of fine-grained features through frequency decomposition or multi-scale modeling; [

123] proposed MF²CNet: it realizes parallel extraction and decoupling of high/low-frequency features (high-frequency for fine-grained details like road markings, low-frequency for global structures like road orientation); [

124] designed a Multi-Granularity Decoupling Network (MGDNet), focusing on “fine-grained feature learning under class-imbalanced scenarios”. The network is guided to focus on subclass differences using region-level supervision; [

125] proposed the ECA-MSDWNet, which integrates “multi-scale feature extraction” with incremental learning: the Efficient Channel Attention module focuses on key fine-grained features, while the multi-scale depthwise convolution reduces computational costs.

Figure 11.

Illustration of Intra-Class Variation and Inter-Class Similarity in Scene-Level Recognition in MEET [

22].

Figure 11.

Illustration of Intra-Class Variation and Inter-Class Similarity in Scene-Level Recognition in MEET [

22].

Cross-Domain and Domain Adaptation Learning. It is one of key technologies for addressing “sensor-region” Shift. In practical applications of fine-grained remote sensing classification, distribution shifts between training data (source domain) and test data (target domain) (e.g., optical-SAR sensor differences, regional differences between southern and northern farmlands) drastically reduce model generalization. This category mainly includes:

1) Open-Set Domain Adaptation: Addressing Real-World Scenarios with “Unknown Subclasses in the Target Domain” Traditional domain adaptation assumes “complete category overlap between source and target domains”, while Open-Set Domain Adaptation (OSDA) is more aligned with remote sensing reality (e.g., unknown subclasses such as “new artificial islands” or “special crops” appearing in the target domain). Its core lies in “separating unknown classes and aligning fine-grained features of known classes”. [

126] proposed IAFAN, which innovatively designs a USS mechanism (calculating sample semantic correlations via instance affinity matrix to identify unknown classes) and uses SDE loss to expand fine-grained differences between known classes (e.g., parking lot-industrial park vehicle arrangement density differences).

2) Multi-Source Domain Adaptation. It achieves fine-grained alignment with limited annotations. For scenarios where the target domain contains only a small number of annotations, this branch improves the domain adaptability of fine-grained features through “pseudo-label optimization” and ”multi-source subdomain modeling“. [

127] uses a bidirectional prototype module for source-target category/pseudo-label alignment, introduces adversarial training to optimize pseudo-labels (reducing mislabeling like ”elevated roads as bridges“). In [

128] for multi-source-single-target domain shifts, it adopts a ”shared + dual-domain feature extractor“ architecture (learning multi-source shared features like water bodies low reflectance first, then fine-grained subdomain alignment per source-target pair). In [

129] to address fine-grained domain shift via frequency dimension, its HFE module aligns source-target fine-grained details (e.g., road marking edge intensity), LFE module aligns global structures (e.g., road network topology).

Semi-Supervised and Zero-Shot Learning. It is the inevitable path to reducing fine-grained annotation dependence. Annotations for fine-grained remote sensing scene classification require dual expertise in pixel-level labeling and subclass semantics, resulting in extremely high annotation costs. This category overcomes data constraints through ”limited annotations + unlabeled sample utilization“ or ”knowledge transfer“, serving as a key enabler for the large-scale application of fine-grained classification.

1) Semi-Supervised Learning. Pseudo-Label Optimization and Consistency Constraints, mainly focused on enhancing the model’s ability to learn fine-grained features through ”supervised signals + unsupervised consistency“. [

130] modeled fine-grained road scene understanding as semi-supervised semantic segmentation. It optimizes supervised loss on annotated samples and consistency loss (e.g., perturbed prediction consistency) on unlabeled ones via ensemble prediction, and cuts annotation cost by using few annotated samples to reach high accuracy of fully supervised models on a self-built dataset. [

124] solved fine-grained minority sample mislabeling—evaluating pseudo-label reliability via model confidence and class prior, prioritizing high-reliability samples for updates, and combined DCF loss to improve minority class accuracy in subclass classification.

2) Zero-Shot Learning. By knowledge graphs or cross-modal transfer, this method targets scenarios with no annotations for target subclasses. This branch achieves fine-grained classification through knowledge transfer, with a core focus on establishing accurate mappings between visual features and semantic descriptions. For example, In [

131], this study constructs a Remote Sensing Knowledge Graph (RSKG) for the first time. It generates semantic representations of remote sensing scene categories through graph representation learning, so as to improve the ability of domain semantic expression.

CNN and Transformer Fusion Modeling. This is one of the technical trend of balancing local details-global semantics. Traditional CNNs excel at extracting local fine-grained features (e.g., edges, textures) but lack strong global semantic modeling capabilities; Transformers excel at capturing global dependencies (e.g., spatial correlations between targets) but have insufficient local detail perception. This category achieves complementary advantages through strategies such as knowledge distillation, feature embedding, and hierarchical fusion, addressing the core contradiction of fragmented local features and missing global semantics in fine-grained classification.