1. Introduction

Object detection, as a core task in computer vision, has become highly valuable in recent years. It has important applications in the fields such as autopilot, intelligent security, and medical imaging [

1,

2,

3]. Remote sensing object detection methods have been effectively utilized for the rotational positioning and classification of terrestrial objects through the analysis of high-resolution aerial imageries, thereby broadening the scope of computer vision in earth observation and offering crucial tech services for essential domains such as metropolitan planning, environmental conservation, as well as disaster observation.

Early detection techniques typically incorporate angle prediction into the regression framework of a universal detection model to enhance remote sensing object recognition and forecasting. However, this has obvious limitations: its network architecture design is relatively simple, and the distinctive characteristic of remote sensing images, which differentiates them from natural images, is not thoroughly acknowledged. Specifically, the aerial view of remote sensing scenes can cause problems such as object angle uncertainty, large object scale span (from small vehicles to large buildings), and complex background interference (such as texture interweaving of vegetation and buildings). These features jointly restrict the improvement of detection accuracy [

4].

In recent years, researchers have designed a series of highly specific detection models built upon CNN or self-attention [

5] referring to the attributes of remote sensing images. LSKNet, invented by Li et al. [

6], serves as a backbone network focused on remote sensing object detection, optimized through large selected kernel convolution. R3Det, proposed by Yang et al. [

7], utilizes bilinear interpolation to align the sampled shape with the object in both shape and angle. FPNFormer, developed by Tian et al. [

8], uses self-attention to optimize the feature pyramid. Although existing methods have made considerable progress, they still face dual challenges: the local characteristics of the convolution operation hinder the model’s ability to capture global features, while the self-attention , despite having powerful global modeling capabilities, encounters a performance bottleneck in the process of processing high-resolution images in remote sensing due to quadratic complexity.

Recently, Mamba [

9], a method founded on the state space model (SSM) [

10,

11,

12], has gained significant attention for its efficient Long-range sequence modeling abilities and linear time , and has gradually been applied within the scope of computer vision. However, the Mamba’s potentials within the domain of remote sensing object detection remains to be further explored. In light of this, this study introduces Mamba to the remote sensing object detection tasks, with the goal of addressing the its unique challenges through Mamba’s efficient global modeling capabilities. However, it should be pointed out that Mamba still has shortcomings in local detail representation [

13,

14], which is particularly prominent in remote sensing scenes containing rich textural information and complex backgrounds.

Because of these technical problems, we’ve come up with MambaRetinaNet, a fusion architecture that integrates Mamba and convolution. MambaRetinaNet is structured into three parts, including a feature extraction backbone network based on Mamba, a feature fusion network combining multi-scale convolution with Mamba (MambaFPN), as well as a universal classification and regression head. The backbone network takes advantage of Mamba’s global modeling power to extract long-distance contextual features, which provides the global dependency information for remote sensing object detection. MambaFPN further optimizes the fused feature using our well-designed synergistic perception module. Specifically, to solve the Mamba’s shortcomings in local feature extractions, we were inspired by the Inception convolution [

15] and proposed a two-way feature optimization module based on multi-scale convolution and SSM, named synergistic perception module (SPM). SPM combines the local perception abilities of multi-scale convolution with the global modeling strengths of SSM, achieving effective alignment of the feature spaces of both branches during feature extraction. This integration not only improves global feature extraction capabilities but also mitigates the challenges posed by the scale diversity of remote sensing objects. In the structural design of FPN, we found that different processing methods for different levels of features can better balance the computational overhead and detection accuracy. Based on this, we designed an asymmetric structure for the neck part, which further enhances the efficiency and performance of the MambaFPN by reallocating computing resources between different scales of features.

In essence, the major contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

1. MambaRetinaNet is designed based on RetinaNet to introduce Mamba into remote sensing object detection and explore its potential.

2. A synergistic perception module (SPM) is presented to improve the interplay between local feature detail perception and global context modeling through the collaborative process of multi-scale convolutional feature extraction and Mamba sequence modeling.

3. MambaFPN is proposed, and the feature processing process of feature pyramid is optimized based on the designed SPM module. At the same time, the asymmetric FPN structure is adopted to balance the detection accuracy and calculation efficiency.

4. Rigorous testing on four widely recognized benchmarks reveals that our method yields performance comparable to SOTA approaches, thereby demonstrating its efficiency and practical utility in detecting objects within remote sensing imagery.

2. Related Work

2.1. Remote Sensing Object Detection

In recent years, as remote sensing technology advances rapidly, researchers have deeply studied the particularity of remote sensing object detection. Cheng et al. [

16] developed a rotation pooling operation. This operation significantly augments the model’s capacity to adapt the objects in different directions by strengthening the convolution’s rotation invariance. Han et al. [

17] designed a rotation-equivariant detector (ReDet) to ensure that the model features maintain equivariant properties under spatial transformations. This approach helps maintain the angular information of the object more effectively. Pu et al. [

18] Presented a rotational convolution operation with adaptive properties by predicting the angle of the input to further enhance the directional sensitivity of feature extraction. In addition, some studies focus on effectively aligning sampling points with the spatial characteristics of rotated boxes. R3Det, S2A-Net, and DFA capture the geometric features of the object more efficiently during the feature extraction process [

7,

19,

20]. Li et al.[

21] proposed Oriented RepPoints, which can accurately capture the direction, scale and shape features of rotating objects by introducing an adaptive point set representation method. Moreover, the introduction of self-attention mechanism provides a new solution to angular diversity. Tian et al. [

8] proposed FPNFormer by introducing the self-attention mechanism into the FPN, exploring the effectiveness of self-attention in handling the angular diversity challenge.

In addition to the directional diversity, the diversity of object scale is also one of key challenges to be solved in remote sensing object detection. Li et al. [

6] believe that different objects require tailored receptive field sizes, so they proposed a backbone network called LSKNet dedicated to remote sensing object detection. This model employs a large separable convolution kernel and improves the detector’s responsiveness to objects of varying scales via adaptive receptive fields. Cai et al. [

22] introduced the Inception-style convolution structure, which enables the network to have muti-scale receptive fields, thus further improving the network ability to handle scale variations. In addition, Lin et al. [

23] posited that the feature pyramid can improve the detector’s capacity to identify objects with varying sizes by integrating information from different scales, including both coarse and fine-grained representations. On this basis, BFP and RaFPN optimized the feature fusion process by introducing the self-attention mechanism, further balancing the semantic differences between feature layers at different scales [

24,

25]. Zhang et al. [

26] optimized the fusion method of feature maps from the perspective of frequency domain, which significantly improved the overall quality of multi-scale feature maps.

In addition, some studies focuses on designing more appropriate loss functions and label allocation strategies. These functions aim to provide better supervision signals for the training process of remote sensing object detection. Qian et al. [

27] designed a new loss function called MRLoss, which effectively alleviated the problem of boundary discontinuity in rotating boxes regression. GWDLoss and KLLoss achieve alignment of training objectives and test criteria by representing the bounding boxes as a Gaussian distribution [

28,

29]. Furthermore, DCFL and other techniques implement dynamic label allocation strategies that adaptively modify label assignment methods according to the results of classification and regression tasks, thereby offering enhanced supervision for model training and consequently augmenting the precision of remote sensing object detection [

30,

31,

32,

33].

2.2. Vision Mamba

Recently, Mamba [

9], a method based on the SSM [

10,

11,

12], has attracted widespread attention for its effective long-range sequence modeling abilities and scaling linearly with input size, and has gradually been applied in image processing studies. Zhu et al. [

34] pioneered the use of Mamba for image feature extraction, proposed the backbone network Vim, and achieved modeling capabilities comparable to self-attention-based models such as ViT [

35] through a bidirectional scanning strategy, which significantly reduces the inference time. In a subsequent research, Liu et al. [

36] proposed VMamba, which is capable of effectively capturing long-distance dependencies in the non-causal sequence of images by introducing cross-scan strategy, and deeply discussed how to design a faster and more accurate Mamba module. For resolving the shortcomings of Mamba in local feature modeling, Huang et al. [

14] introduced the windowed scanning strategy to enhance the local modeling ability. Pei et al. [

13] resolved the shortcomings of local modeling through a dual-branch structure, and designed a lightweight Mamba backbone network named EfficientvMamba, which achieved a better balance between efficiency and performance. In terms of the principle and performance analysis of Mamba module, Yu et al. [

37] discussed the necessity of introducing Mamba into visual tasks, while Han et al. [

38] deeply studied the similarity between Mamba and linear attention, and combined advantages of the two in designing a more powerful backbone network called Demystify Mamba. Beyond its use in general feature extraction, Mamba is widely adopted in downstream tasks. For example, in image segmentation tasks, studies on U-Mamba, Vm-UNet, Mamba-UNet, SegMamba and others combine the Mamba module with the UNet architecture to demonstrate the powerful segmentation performance through fine feature modeling [

39,

40,

41,

42]. In terms of object detection, Wang et al. [

43] incorporated Mamba into the detection network and proposed a lightweight detection framework called Mamba-YOLO based on Mamba. In multi-modal feature fusion tasks, Chen et al. [

44] designed a multi-modal object detection network called MiM-ISTD, which improved the accuracy of infrared small object detection.

3. Method

3.1. Vision Mamba

State Space Model (SSM) is a continuous system that maps the continuous input

onto the continuous output

through the hidden state

, and is formulated as follows:

where

A is the state transition matrix which specifies how the present state influences the next state,

B is a input matrix, which illustrates the impact of the input on the alteration of the system state,

C serves as the observation matrix, mapping the system state to the output, while

D as the direct transfer matrix that quantifies the input’s immediate impact on the output.

To apply this continuous system to the transformation of discrete sequences, Mamba [

9] transforms parameter

A and parameter

B into their discrete forms

and

by means of zero-order hold method:

where

is the time scale parameter, and

I is the unit matrix. Therefore, the transformed discrete state space model can be obtained as follows:

Selective State Space Model Mamba incorporates a selection mechanism to allow the SSM to perceive the input content effectively. Specifically, Mamba utilizes a learnable linear mapping to adaptively generate SSM parameters of the current time step according to the input

. The process of generation is as follows:

where

are a learnable linear transformations for dynamically generating SSM parameters based on the input, thus enabling the input-driven adaptive modeling.

2D-Selective-Scan for Vision Data (SS2D) Although the sequential scan of Mamba performs well in NLP tasks with causality, its simple sequential scan method struggles to effectively model the spatial structure in image patch sequences without causality. This results in the loss of spatial information. To this end, SS2D [

36] involves Cross-Scan and Cross-Merge strategies to strengthen Mamba’s capacity to handle visual tasks.

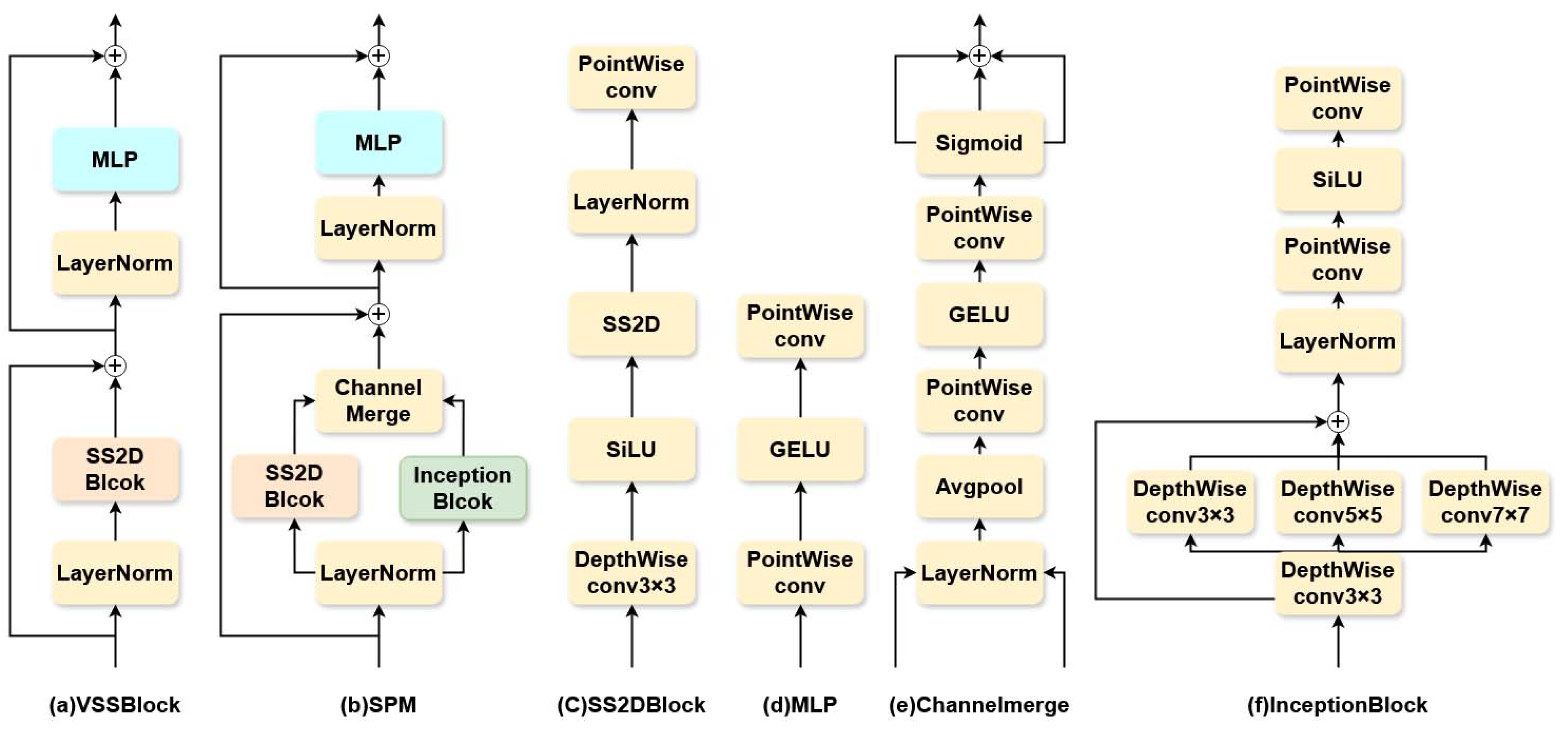

As shown in

Figure 1, the feature map is evenly divided into multiple patches (here divided into nine for display). Subsequently, the patch is sequenced along four different directions by cross-scan to generate four one-dimensional sequences, which are input into the Mamba block for sequence modeling. The processed patch sequence is then sequentially restored to two-dimensional image features through cross-merge. The final scan result is generated by a summation operation.

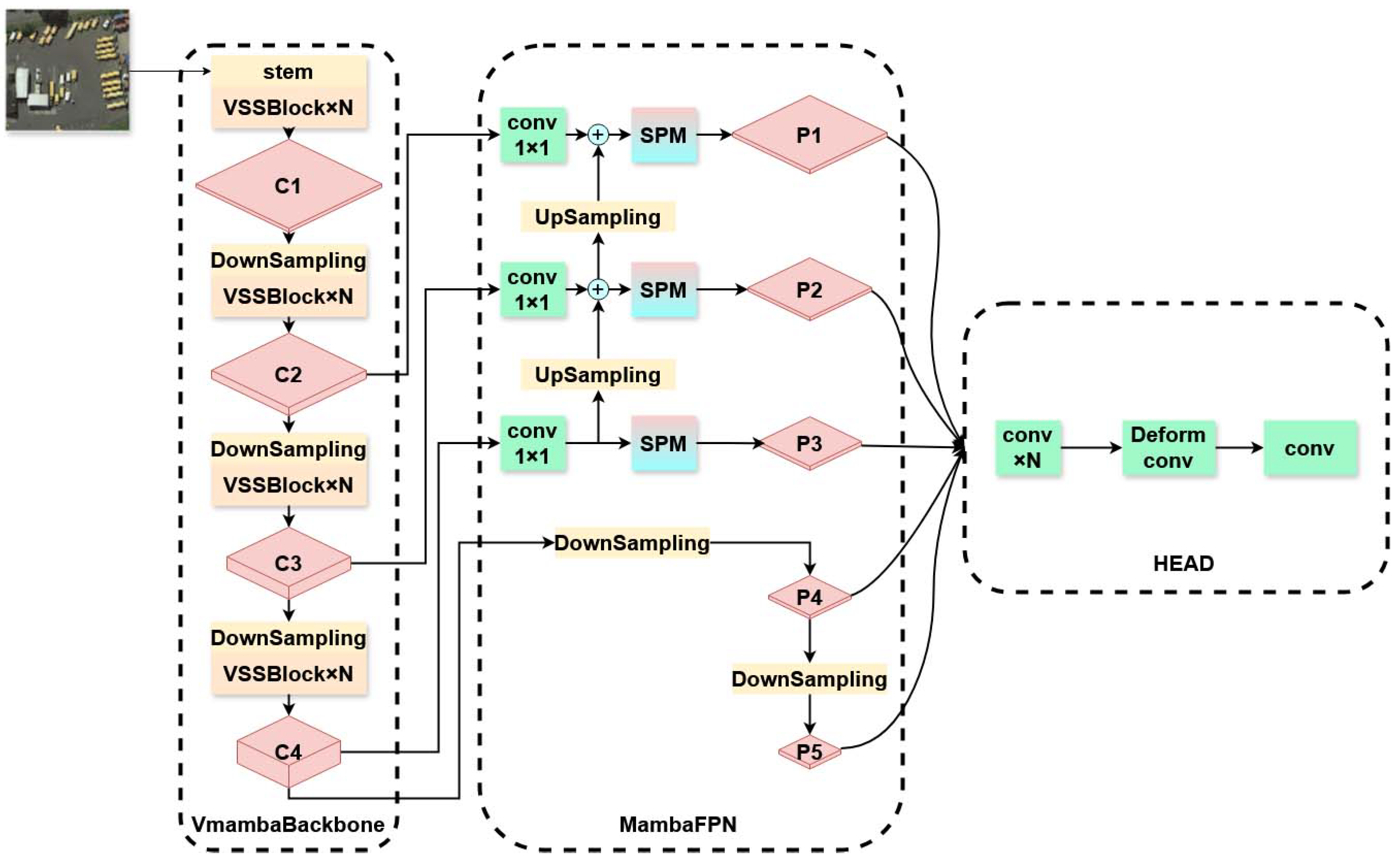

3.2. Framework of MambaRetinanet Network

To effectively integrate the capabilities of the Mamba framework in long-distance dependency modeling, this study proposes the MambaRetinaNet object detection framework as shown in

Figure 2. In this framework, the input image is initially processed by the backbone network based on the VMamba architecture, and then features of different levels are interacted and fused across scales through the specially designed MambaFPN . The final generated features are sent to the detection head to perform the object classification and boxes regression tasks respectively.

In MambaRetinanet, the structure of VmambaBackbone is similar to that of the classical visual backbones such as ResNet [

45], both consisting of four stages. The first stage contains a stem module that partitions the input image into a patch sequence through a 4x4 convolution, and contains several SS2D-based global modeling VSSBlock modules (

Figure 3a). The subsequent three stages consist of a down-sampling module and multiple VSSBlock modules, which are employed to incrementally decrease the feature map size and gather richer global context information. MambaFPN optimizes the fused features through SPM (

Figure 3b). This design not only effectively reduces the overlapping effect, but also enhances the instance correlation within the same feature levels. For the design of detection head, we adopted an architecture similar to that of the traditional detection head, which is mainly composed of multiple consecutive convolutional layers. The sole distinction is the incorporation of a deformabale convolution operation prior to the convolution that produces the prediction result, utilizing the offset generated by the convolution to modify the center location of the preset boxes. This design enables the model to adaptively fine-tune the sampling position as per the nature of different objects. And, through the optimized boxes, it can efficiently address the problem of mismatch with smaller objects [

31].

3.3. Synergistic Perception Module (SPM)

For the common problem of lacking adequate local detail extraction by universal vision Mamba module in multi-scale environment, this study proposes a synergistic perception module (SPM), which forms a complementary structure through carefully designed InceptionBlock and VSSBlock. While giving full play to the advantages of the global feature modeling of Mamba module, it realizes the synchronous capture and retention of local detail features through spatial perception enhancement mechanism. This feature synergy method effectively overcomes the local feature attenuation problem of the traditional visual Mamba architectures, and realizes the synergistic optimization of multi-scale feature expression.

As depicted in

Figure 3 (a) and (b), the key difference between our synergistic perception module (SPM) and the VSSBlock is the introduction of a dual-branch structure. Specifically, for a given input feature

X, SPM first processes the normalized feature input

using two different modules of SS2DBlock and InceptionBlock respectively, to extract the global feature

and the local feature

. Next,

and

are fed into the Channelmerge module, which reinforces the global feature and the local feature through the shared channel attention mechanism [

46] and suppresses the redundant information. Finally, these two kinds of features are fused via element-wise summation operation, in order to achieve a more comprehensive feature representation. The procedure for the dual-branch is as follows:

To meet the needs of feature extraction with changeable scales in remote sensing images, InceptionBlock has multiple parallel depthwise convolution branches, and uses convolution kernels of different sizes to process input features, so as to efficiently capture the multi-scale information. Subsequently, the outputs of these branches are fused through element-by-element summation operation to integrate features at different scales. To further refine the effectiveness of feature expression, InceptionBlock uses two point-by-point convolutions to perform information interaction and transformation between channels on the fused features. Furthermore, to ensure consistency with the features produced by SS2DBlock, LayerNorm is employed for normalization rather than the more prevalent BatchNorm. The definition of InceptionBlock is as follows:

where DConv represents depthwise convolution, PConv represents point convolution,

X and

Y and represent the input and the output, respectively.

3.4. MambaFPN

The traditional feature pyramid network (FPN) utilizes convolution operations to process fused multi-scale features, mitigating feature overlap; however, its fixed receptive field convolution kernel struggles to accommodate the scale variations of instances within the same level of the feature map in intricate remote sensing scenarios, leading to constrained model efficacy. Secondly, the traditional Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) employs a symmetrical architecture to handle various levels of feature maps; specifically, identical operations are applied to the outputs at each level, disregarding the distinct processing needs of shallow detail features and deep semantic information, resulting in an imbalance between computational resources and model accuracy.

To solve this problem, MambaFPN introduces a Mamba-based feature processing module called SPM, where global contextual modeling is utilized to model the long-distance dependencies across instances in combination with local context awareness to enhance the dynamic adaptability to scale changes. This global-local dual-field synergy mechanism enhances MambaRetinaNet’s feature discrimination for instances at different scales.

Secondly, MambaFPN is designed with an asymmetric structure, where processing modules are allocated in a differentiated manner to balance and optimize detection performance and computational speed.

As shown in

Figure 2, MambaFPN receives the last three hierarchical feature maps C2, C3, and C4 of the backbone network to generate multi-scale feature maps P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5. Specifically, C2, C3, and C4 are first processed through a bottom-up feature fusion path to fully integrate multi-level features in a way that generates a fused multi-scale feature map. The fused features are further optimized by the SPM to enhance their expressive capability. In the end, P1, P2, and P3 are generated. The feature maps P4 and P5 correspond to deeper levels. These features have been downsampled multiple times, resulting in a significantly increased receptive field. At this time, each feature pixel already contains rich semantic and contextual information and can capture more global image features, so there is no need for further processing through the SPM. Therefore, MambaFPN is directly based on C4. It generates P4 and P5 through two rounds of downsampling, simplifying the calculation while maintaining performance.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Dataset

To evaluate the performance of the proposed MambaRetinaNet, we carried out comprehensive experiments on various benchmark remote sensing object detection datasets, such as DOTA-v1.0 [

4], DOTA-v1.5, DOTA-v2.0 [

47], as well as DIOR-R [

48].

DOTA series, a high-quality dataset tailored for remote sensing object detection tasks, is widely used in research and for the evaluation of complex scenes or multi-scale object detection algorithms. By continuously and iteratively increasing the variety of classes and the corresponding object samples, DOTA-v2.0, the latest version, consists of 11,268 images and a total of 1,793,658 object annotations, spanning across 18 different object type. Relative to the original release, DOTA-v2.0 features a significant enhancement in both diversity and complexity. As a result, handling complex backgrounds and objects at varying scales has become much more challenging.

Derived from the DIOR dataset, the DIOR-R dataset is an extended version that introduces rotating bounding box annotations to better accommodate object directionality in remote sensing images. This dataset holds 23,463 images with 192,518 instances of objects, distributed over 20 categories, and provides more challenging experimental conditions to evaluate how well detection algorithms perform on objects with orientation.

4.2. Implementation Details

In the entirety of the experiments, the training and evaluation was implemented in a single leaflet NVIDIA RTX 4070 GPU computer. The model was run using the MMRotate [

49] framework and PyTorch [

50], with training conducted using a stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer. The hyperparameters for the optimizer were set to a learning rate of 0.005, momentum of 0.9, and weight decay of 0.0001.In terms of cost function, the Focal Loss was leveraged for the classification task to alleviate the category imbalance, while IOU loss [

51] was used for the regression task to optimize the overlap degree of the object boxes. In addition, to further boost the model performance, we introduced a dynamic label allocation method to optimize the matching strategy of positive and negative samples.

For data augmentation, we only used random flipping to simplify the experimental process. For the experiments with the DOTA dataset, we followed the official standard setting to crop the input image into small blocks with a size of 1024 × 1024, an overlap area of 200 for training and evaluation and a batch size of 2. For experiments with the DIOR-R dataset, we set the input image size at 800 × 800 with a batch size of 4. In the testing phase, we utilized the training and validation sets of each dataset for model training and conducted the final evaluation on the test set.

To ensure stability and convergence of model performance during testing, experiments on all datasets were set to 40 rounds of training. Except for the DOTA-v1.0 dataset, which was trained for 36 rounds. While in the ablation experiment, we selected DOTA-v2.0 training set with abundant object categories and instances for training and performed the evaluation on the validation set. To efficiently verify the impact of each module and configuration, we reduced the training rounds to 12 so as to quickly analyze the specific influence of each module and configuration on model performance.

4.3. Results

We systematically compared the proposed MambaRetinaNet model with a variety of advanced remote sensing object detection methods on the above four datasets to comprehensively verify its performance and generalization ability.

Table 1 presents the outcomes of the proposed MambaRetinaNet using single-scale training tests on the DOTA-v2.0 , and compares them with other advanced detection models. The mAP of MambaRetinaNet reaches 57.17, indicating its ability to compete with other models. MambaRetinaNet demonstrates a 10.49 improvement in mAP over the baseline model RetinaNet, which fully proves the effectiveness of our method. In addition, the data show that MambaRetinaNet performs particularly well in categories such as Harbor and Roundabout. It further reveals that the proposed model effectively detects object instances that require large receptive fields or have significant scale changes.

In

Table 2 and

Table 3 we provide a summary on the detection results of MambaRetinaNet and classical one-stage and two-stage detection methods on the DOTA-v1.0 and DOTA-v1.5 , respectively. Compared with classical methods, our method shows remarkable performance superiority on these two datasets. On the DOTA-v1.5 , MambaRetinaNet obtained a mAP of 70.21, whereas on the DOTA-v1.0 , it reached 77.50.When we compare our method to the baseline model, it consistently performs better across different versions of the DOTA series datasets, and it improves accuracy by almost +11.

Table 4 provides the experimental results of the MambaRetinaNet and other models in remote sensing object detection on the DIOR-R dataset, and verifies the generalization ability of the proposed model. From the results, it is apparent that our model not only comprehensively surpasses the classic remote sensing object detection methodology in terms of accuracy in detection by reaching 71.50 mAP, but also delivers a remarkable improvement of +13.95 compared with the baseline model. This result fully demonstrates that MambaRetinaNet performs well not only on a single dataset but also exhibits high generalization capabilities.

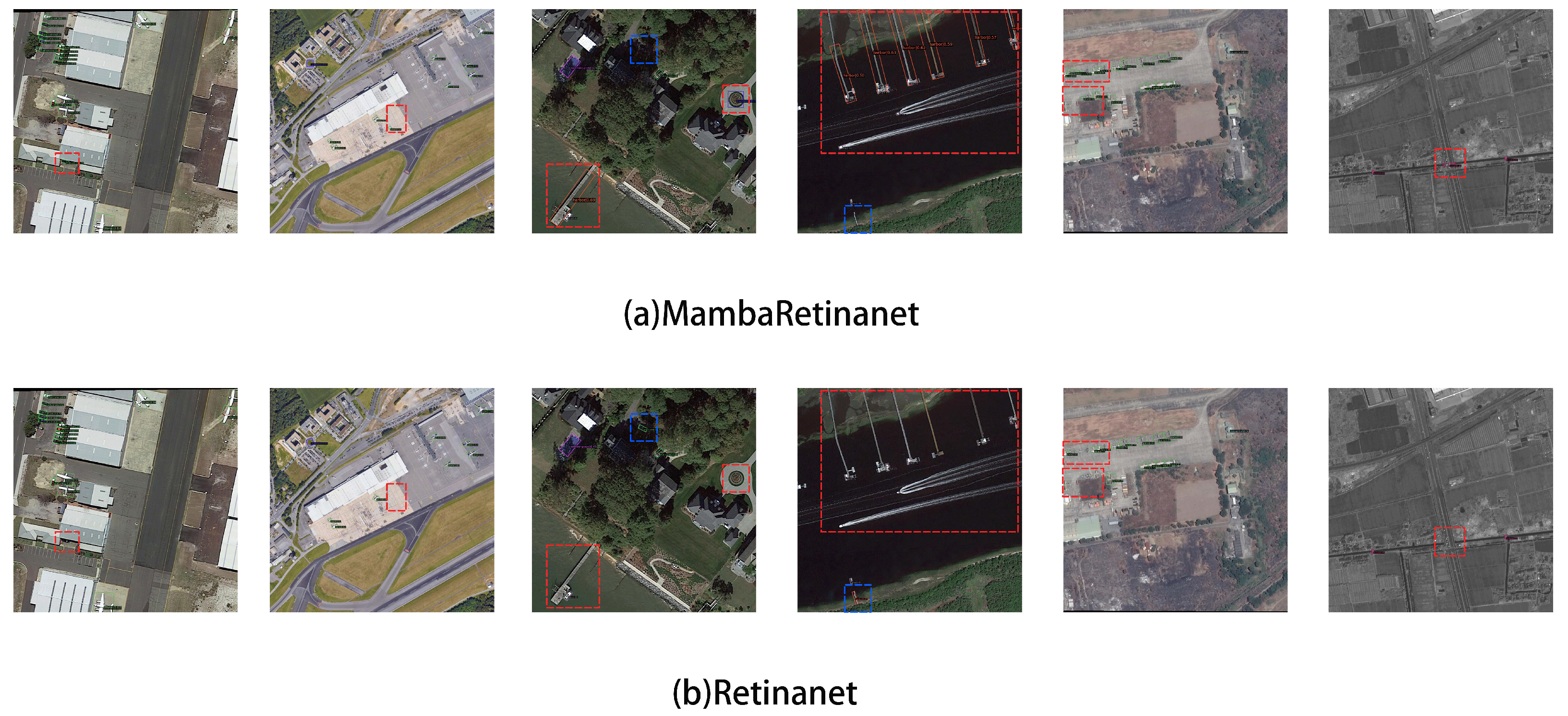

Beyond the quantitative analysis provided earlier, we also engaged in visualization experiments for qualitative inspection. As shown in

Figure 4, MambaRetinaNet shows a significant performance improvement when dealing with objects requiring large receptive fields. Besides, in complex environments, such as blurred or occluded scenes, MambaRetinaNet shows higher adaptability. In contrast, RetinaNet-OBB has limited performance in these challenging environments, making it difficult to effectively deal with complex scenes and scale changes. In addition, MambaRetinaNet shows evident improvements in object classification. The detection outcomes of this model typically exhibit elevated classification confidence, signifying a substantial improvement in the model’s semantic extraction capability.

Combined experimental results show that by improving the network architecture and feature extraction mechanism, MambaRetinaNet effectively enhances our ability to capture semantic features while retaining the key details of the object. This enables MambaRetinanet to make full use of local and global information to extract effective features when facing complex scenes and changeable scales, so as to detect an object more accurately.

4.4. Ablation Experiments

Here we conduct a series of ablation tests to confirm the efficacy of the suggested asymmetric FPN and SPM and various hyperparameter setups. To guarantee the consistency and reliability of the experimental results, all experimental configurations are consistent with RetinaNet, and the only difference is that the original FPN is replaced by the proposed MambaFPN.

Asymmetric FPN Several rounds of ablation experiments were conducted to investigate the effectiveness of asymmetric FPN. As shown in

Table 5, when convolution or SPM is used for all stages of FPN, the model’s mAP are 51.70 and 53.61, respectively. However, if SPM is used only in the first three stages and the convolution is retained in the last two stages, the model’s mAP is significantly improved to 54.47, presenting the best performance. This result indicates the necessity of choosing the proper processing method founded on the natures of the features at various stages, and demonstrates the superiority of the asymmetric FPN.

Synergistic Perception Module (SPM) We compared the proposed SPM with the current advanced visual Mamba module.

Table 6 illustrates that the VSSBlock achieved an mAP of 53.03, while the EVSSBlock attained an mAP of 53.00. In contrast, our proposed SPM reached an mAP of 54.47, showing the best performance.

Interestingly, although EVSSBlock introduces convolution to enhance Mamba’s local modeling capabilities, its detection accuracy is equal to or even slightly lower than that of VSSBlock using solely Mamba. We believe this may be caused by the failure to effectively capture the contextual details at multiple scales due to the restrictions of 3 × 3 convolution in dealing with the remote sensing images, which is an important reason that inspired us to propose the SPM.

In addition, we also analyzed the effects of varying the sizes and quantities of convolution kernels on the performance of the SPM. As shown in

Table 6, the SPM presents the best performance (mAP is 54.47) when the convolution kernel size is (3, 3, 5, 7) and the number of convolution kernels is 4. However, as the size or number of convolution kernels increases, performance declines to a certain degree. We speculate that this may be caused by the negative impact of background noise introduced by the larger convolution kernel, which affects the model’s performance.

5. Discussion

Experimental results illustrate that introducing Mamba into the remote sensing object detection domain can significantly enhance the performance. Compared to the baseline models, our MambaRetinaNet achieved an approximate 11% improvement. Both quantitative and qualitative analyses indicate that MambaRetinaNet not only provides more accurate classification but also offers a more reliable solution for remote sensing scenarios that require large receptive fields or involve variable scales.

This advantage primarily stems from the integration of the Mamba module and the design of the SPM. Mamba not only fulfills the need for an excessively large receptive field for objects exhibiting extreme shape ratios but also enriches feature diversity through global feature extraction, thereby enabling more precise classification. Moreover, to address Mamba’s limitations in local modeling, we fuse global features with local information at different scales to obtain a more comprehensive feature representation. Although multi-scale feature extraction methods have been widely adopted, our study focuses on leveraging multi-scale features to compensate for Mamba’s shortcomings in local feature extraction—an essential factor for successfully applying Mamba in the realm of remote sensing object localization.

Ablation analysis of the SPM suggests that, compared to other general-purpose visual Mamba modules, SPM yields superior detection performance. A comparison with the EVSSBlock further confirms that our proposed InceptionBlock exhibits enhanced local feature extraction capabilities for remote sensing tasks. In addition, the configuration of convolution kernel sizes and quantities determines the range of scale variations addressed at each layer. Our experiments indicate that setting the convolution kernel sizes to (3,3,5,7) improves detection performance, whereas increasing the kernel size or number slightly degrades performance—likely due to the introduction of redundant noise from an excessively large receptive field.

Furthermore, ablation studies on the asymmetric FPN suggest that applying differentiated processing strategies to different feature levels is critical. Unlike other efficient methods that utilize complex processing units in deeper layers and simpler ones in shallower layers, our optimal results are achieved by employing more complex units in the shallow layers and simpler ones in the deeper layers. This phenomenon may stem from the fact that shallow features are highly sensitive to global information as they are limited by smaller receptive fields. Introducing global information can significantly improve the contextual modeling capabilities of shallow layers, thereby improving the overall model performance. As network depth increases and the receptive field of deep features expands sufficiently, the incremental advantage of incorporating additional global information diminishes, and performance may decline due to information redundancy.

Although MambaRetinaNet has demonstrated excellent performance in remote sensing object detection, it has not fully tapped into its potential. This is due to the limitations in computing resources, which prevented us from integrating the synergistic perception module into the backbone network .network. The design of remote sensing object detection backbone network has aroused extensive research interest over recent years. Research on LSKNet [

6] and PKINet [

22] provides us with an opportunity to explore further and offers useful references. In addition, the research on MambaRetinaNet is mainly centered on solving multi-scale issues in remote sensing images, while less attention has been paid to angular diversity. Therefore, future studies should concentrate on further integrating the Mamba module into the backbone network for remote sensing task, and to explore its potential in addressing the challenge of angular diversity, thereby fully leveraging Mamba’s unique advantages.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, a novel remote sensing object detection model called MambaRetinaNet, which aims to address complex scenes and object scale diversity in remote sensing object detection, is presented and the potential of Mamba in the field of remote sensing object detection is studied. Considering the nature of remote sensing images and the merits and demerits of Mamba, we designed the SPM. By combining Mamba with multi-scale convolution, we solved the limitations of Mamba in local detail modeling and efficiently fused global and local semantics. Building on this, an asymmetric feature pyramid network (MambaFPN) was further developed, incorporating SPM and differentiating feature processing to balance the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

The experimental results showed that MambaRetinaNet is highly competitive on four mainstream remote sensing detection datasets. Specifically, the model outperforms the baseline by over 11% across four datasets and achieves SOTA performance on the DOTA-v2.0 dataset. Although MambaRetinanet has delivered an excellent detection accuracy, we have not further delved into the wide applicability of the designed module to the backbone network, and the research on whetherMamba module can effectively deal with the problem of angular diversity is not sufficient. Future studies will concentrate on these areas.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, J.C. and J.W.; methodology, J.C. ,J.S. and J.W.; software, J.C.; validation, J.C.; formal analysis, J.C.; Investigation, J.C. and J.Y.; Resources, J.S.. and H.G.; data curation, J.C. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and J.W.; supervision, J.W., J.S., H.G., G.W. and D.Z.; funding acquisition, J.S. and H.G.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Major Project of "Next Generation Artificial Intelligence" (Grant No. 2023ZD0120604), the Key Research and Development Program of Henan Province (Grant No. 241111212300), and the Major Science and Technology Project of Henan Province (Grant No. 201400210100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 779–788.

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2980–2988.

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 3974–3983.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser. ; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Hou, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Cheng, M.M.; Yang, J.; Li, X. Large selective kernel network for remote sensing object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2023, pp. 16794–16805.

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Feng, Z.; He, T. R3det: Refined single-stage detector with feature refinement for rotating object. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 3163–3171.

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, W. FPNFormer: Rethink the method of processing the rotation-invariance and rotation-equivariance on arbitrary-oriented object detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752 2023.

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.00396 2021.

- Gu, A.; Johnson, I.; Goel, K.; Saab, K.; Dao, T.; Rudra, A.; Ré, C. Combining recurrent, convolutional, and continuous-time models with linear state space layers. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 572–585. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Gu, A.; Berant, J. Diagonal state spaces are as effective as structured state spaces. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 22982–22994. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, X.; Huang, T.; Xu, C. Efficientvmamba: Atrous selective scan for light weight visual mamba. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09977 2024.

- Huang, T.; Pei, X.; You, S.; Wang, F.; Qian, C.; Xu, C. Localmamba: Visual state space model with windowed selective scan. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09338 2024.

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015, pp. 1–9.

- Cheng, G.; Zhou, P.; Han, J. Learning rotation-invariant convolutional neural networks for object detection in VHR optical remote sensing images. IEEE transactions on geoscience and remote sensing 2016, 54, 7405–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Xia, G.S. Redet: A rotation-equivariant detector for aerial object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 2786–2795.

- Pu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gan, W.; Wang, Z.; Song, S.; Huang, G. Adaptive rotated convolution for rotated object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 6589–6600.

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Xia, G.S. Align Deep Features for Oriented Object Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Lu, K.; Xue, J. Refined one-stage oriented object detection method for remote sensing images. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2022, 31, 1545–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhu, J. Oriented reppoints for aerial object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 1829–1838.

- Cai, X.; Lai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Yao, Y. Poly kernel inception network for remote sensing detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 27706–27716.

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 2117–2125.

- Guo, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, N.; Song, B.; Gao, X. A rotational libra R-CNN method for ship detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 5772–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Y. RaFPN: Relation-aware Feature Pyramid Network for Dense Image Prediction. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiao, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H. Laplacian feature pyramid network for object detection in VHR optical remote sensing images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Yang, X.; Peng, S.; Yan, J.; Guo, Y. Learning modulated loss for rotated object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 2458–2466.

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q. Rethinking rotated object detection with gaussian wasserstein distance loss. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 11830–11841.

- Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Tian, Q.; Yan, J. Learning high-precision bounding box for rotated object detection via kullback-leibler divergence. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 18381–18394. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Li, W.; Xia, X.G.; Tao, R. A general Gaussian heatmap label assignment for arbitrary-oriented object detection. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2022, 31, 1895–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Ding, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Yu, L.; Xia, G.S. Dynamic coarse-to-fine learning for oriented tiny object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 7318–7328.

- Hou, L.; Lu, K.; Xue, J.; Li, Y. Shape-adaptive selection and measurement for oriented object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 923–932.

- Hou, L.; Lu, K.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Xue, J. G-rep: Gaussian representation for arbitrary-oriented object detection. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2401.09417].

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 2020.

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. Vmamba: Visual state space model. Advances in neural information processing systems 2024, 37, 103031–103063. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Wang, X. Mambaout: Do we really need mamba for vision? arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.07992 2024.

- Han, D.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Han, Y.; Pu, Y.; Ge, C.; Song, J.; Song, S.; Zheng, B.; Huang, G. Demystify mamba in vision: A linear attention perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.16605 2024.

- Ma, J.; Li, F.; Wang, B. U-mamba: Enhancing long-range dependency for biomedical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.04722 2024.

- Ruan, J.; Li, J.; Xiang, S. Vm-unet: Vision mamba unet for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02491 2024.

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, G.; Li, L. Mamba-unet: Unet-like pure visual mamba for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.05079 2024.

- Xing, Z.; Ye, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhu, L. Segmamba: Long-range sequential modeling mamba for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2024, pp. 578–588.

- Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X. Mamba YOLO: SSMs-based YOLO for object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05835 2024.

- Chen, T.; Ye, Z.; Tan, Z.; Gong, T.; Wu, Y.; Chu, Q.; Liu, B.; Yu, N.; Ye, J. Mim-istd: Mamba-in-mamba for efficient infrared small target detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 7132–7141.

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, M.Y.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; et al. Object detection in aerial images: A large-scale benchmark and challenges. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2021, 44, 7778–7796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Xie, X.; Lang, C.; Yao, Y.; Han, J. Anchor-free oriented proposal generator for object detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Hou, L.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Yan, J.; Lyu, C.; et al. Mmrotate: A rotated object detection benchmark using pytorch. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2022, pp. 7331–7334.

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Fang, J.; Song, X.; Guan, C.; Yin, J.; Dai, Y.; Yang, R. Iou loss for 2d/3d object detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 international conference on 3D vision (3DV). IEEE, 2019, pp. 85–94.

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2961–2969.

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Long, Y.; Xia, G.S.; Lu, Q. Learning RoI transformer for detecting oriented objects in aerial images. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.00155 2018.

- Xie, X.; Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Oriented R-CNN for object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 3520–3529.

- Ming, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Miao, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, L. Dynamic anchor learning for arbitrary-oriented object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 2355–2363.

- Courtrai, L.; Pham, M.T.; Lefèvre, S. Small object detection in remote sensing images based on super-resolution with auxiliary generative adversarial networks. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).