Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Ovariectomy

2.3. Guava Seeds

2.4. Seed Delipidation

2.5. Blood Pressure

2.6. Lipid Profile

2.7. HDL Size and Lipid Concentration of HDL Subclasses

2.8. Determination of Apolipoproteins

2.9. Paraoxonase-1 Activity

2.10. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Biochemical Parameters

3.2. Size and Lipid Composition of HDL Subclasses

3.3. Apolipoproteins

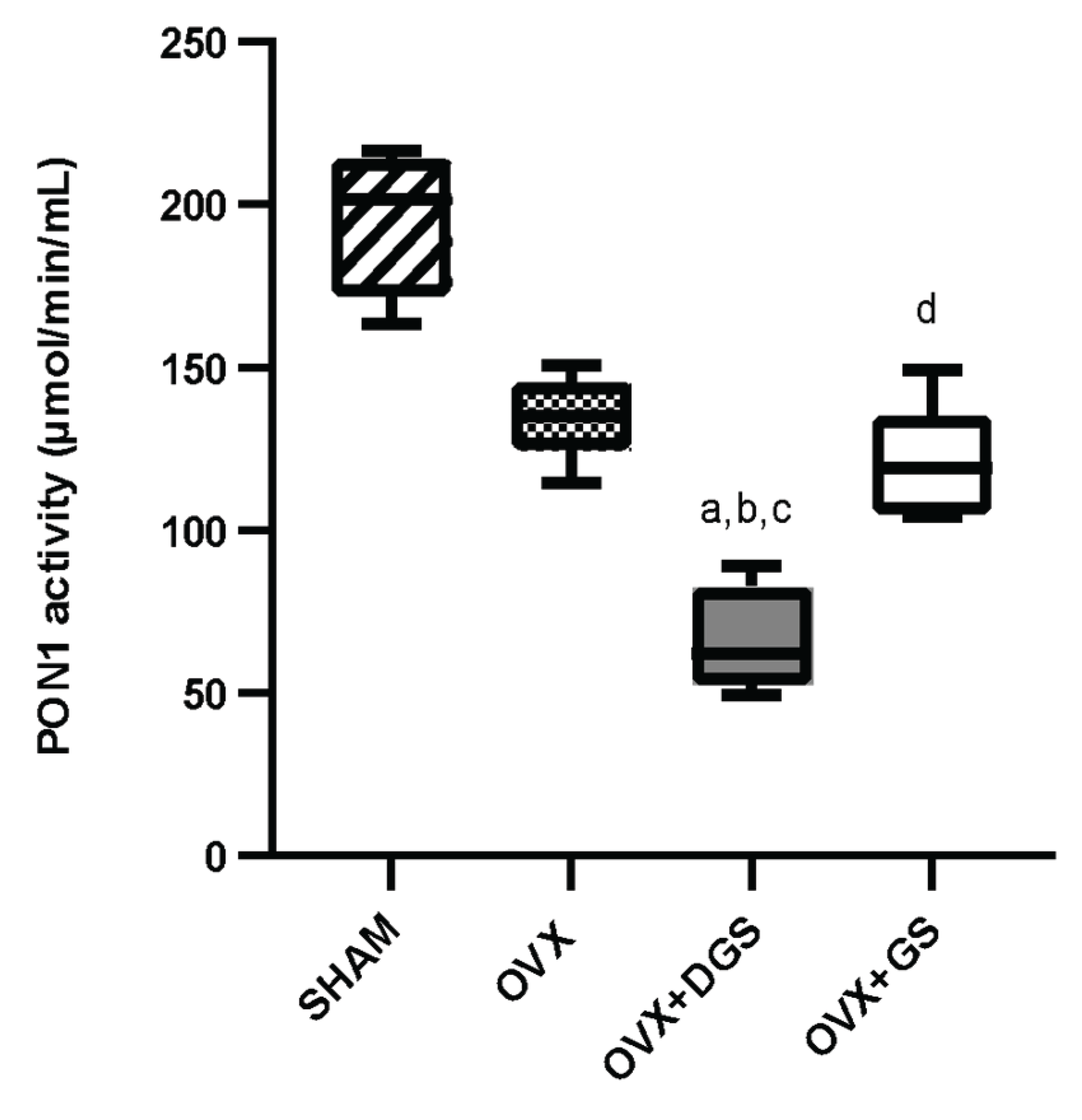

3.4. PON1 Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| PON1 | Paraoxonase-1 |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| SHAM | SHAM-operated rats |

| OVX | Ovariectomized rats |

| DGS | Defatted guava seeds |

| GS | Guava seeds |

| HDL-c | HDL cholesterol |

| HDL-Tg | HDL triglycerides |

| HDL-PPL | HDL phospholipids |

| Apo | Apolipoprotein |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| RCT | Reverse cholesterol transport |

| LCAT | Lecithin: cholesterol: acyltransferase |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| LPL | Lipoprotein lipase |

References

- Anagnostis, P.; Stevenson, J.C.; Crook, D.; Johnston, D.G.; & Godsland, I.F. ; & Godsland, I. F. Effects of gender, age and menopausal status on serum apolipoprotein concentrations. Clin Endocrinol 2016, 85, 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, M.C. The emergence of the metabolic syndrome with menopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, E.B. The timing of the age at which natural menopause occurs. Obstet Gynecol Clin 2011, 38, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salpeter, S.R.; Walsh, J.M.E.; Ormiston, T.M.; Greyber, E.; Buckley, N.S.; & Salpeter, E.E.; Salpeter, E. E. Meta-analysis: effect of hormone-replacement therapy on components of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Diabetes Obes Metab 2006, 8, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostara, C.E.; Bairaktari, E.T.; Tsimihodimos, V. Effect of clinical and laboratory parameters on HDL particle composition. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Luna, D. , Carreón-Torres, E., Bautista-Pérez, R., Betanzos-Cabrera, G., Dorantes-Morales, A., Luna-Luna, M.,... & Pérez-Méndez, Ó. Microencapsulated pomegranate reverts high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-induced endothelial dysfunction and reduces postprandial triglyceridemia in women with acute coronary syndrome. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El Khoudary, S.R.; Chen, X.; Nasr, A.; Billheimer, J.; Brooks, M.M.; McConnell, D.; et al. HDL (high-density lipoprotein) subclasses, lipid content, and function trajectories across the menopause transition: SWAN-HDL study. ATVB 2021, 41, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehti, S.; Korhonen, T.M.; Soliymani, R.; Ruhanen, H.; Lähteenmäki, E.I.; Palviainen, M.; et al. The lipidome and proteome of high-density lipoprotein are altered in menopause. J Appl Physiol 2025, 139, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.C. Nutritional influences on estrogen metabolism. Appl Nutr Sci Rep 2001, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Delgado, F.; Katsiki, N.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; & Perez-Martinez, P.; Perez-Martinez, P. Dietary habits, lipoprotein metabolism and cardiovascular disease: From individual foods to dietary patterns. Crit Rev Food Sci Nut 2021, 61, 1651–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural (SADER). Garantiza Agricultura producción y abasto de guayaba para esta temporada decembrina. 2022. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/prensa/garantiza-agricultura-produccion-y-abasto-de-guayaba-para-esta-temporada-decembrina#:~:text=En%202021%2C%20Michoac%C3%A1n%20registr%C3%B3%2010,y%2029%20mil%20982%20toneladas. (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Martínez, R.; Torres, P.; Meneses, M.A.; Figueroa, J.G.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; & Viuda-Martos, M.; Viuda-Martos, M. Chemical, technological and in vitro antioxidant properties of mango, guava, pineapple and passion fruit dietary fibre concentrate. Food Chem 2012, 135, 1520–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Lima, R.; Ferreira, S.R.S.; Vitali, L.; & Block, J.M.; Block, J. M. May the superfruit red guava and its processing waste be a potential ingredient in functional foods? Food Res Int 2019, 2019 115, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchôa-thomaz, A.M.A.; Sousa, E.C.; Carioca, J.O.B.; Morais, S.M.D.; Lima, A.D.; Martins, C.G.; et al. Chemical composition, fatty acid profile and bioactive compounds of guava seeds (Psidium guajava L.). Food Sci Technol 2014, 34, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, H.; Kausar, T.; Noreen, S.; Rehman, H.U.; Hussain, A.; Huang, Q.; et al. In vivo screening and antidiabetic potential of polyphenol extracts from guava pulp, seeds and leaves. Animals 2020, 10, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prommaban, A.; Utama-Ang, N.; Chaikitwattana, A.; Uthaipibull, C.; Porter, J.B.; & Srichairatanakool, S.; Srichairatanakool, S. Phytosterol, lipid and phenolic composition, and biological activities of guava seed oil. Molecules 2020, 25, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Chang, C.K.; Tso, T.K.; Huang, J.J.; Chang, W.W.; & Tsai, Y.C.; Tsai, Y. C. Antioxidant activities of various fruits and vegetables produced in Taiwan. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2004, 55, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelegrini, P.B.; Murad, A.M.; Silva, L.P.; Dos Santos, R.C.; Costa, F.T.; Tagliari, P.D.; et al. Identification of a novel storage glycine-rich peptide from guava (Psidium guajava) seeds with activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Peptides 2008, 29, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación. NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-062-ZOO-1999, Especificaciones técnicas para la producción, cuidado y uso de los animales de laboratorio. Diario Oficial de la Federación, 6 de diciembre de 1999, México.

- Brower, G.L.; Gardner, J.D.; & Janicki, J.S.; Janicki, J. S. Gender mediated cardiac protection from adverse ventricular remodeling is abolished by ovariectomy. Mol Cell Biochem 2003, 251, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronsky, T.J. The ovariectomized rat as an animal model for postmenopausal bone loss. Cells Mater 1992, S69–S74. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.T.; Krauss, R.M.; Nichols, A.V.; Vranizan, K.M.; & Wood, P.D.; Wood, P. D. Identifying the predominant peak diameter of high-density and low-density lipoproteins by electrophoresis. J Lipid Res 1990, 31, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreón-Torres, E.; Juárez-Meavepeña, M.; Cardoso-Saldaña, G.; Gómez, C.H.; Franco, M.; Fievet, C.; et al. Pioglitazone increases the fractional catabolic and production rates of high-density lipoproteins apo AI in the New Zealand White Rabbit. Atherosclerosis 2005, 181, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnick, G.R.; McNamara, J.R.; Boggess, C.N.; Clendenen, F.; Williams, P.T.; & Landolt, C.C.; Landolt, C. C. Polyacrylamide gradient gel electrophoresis of lipoprotein subclasses. Clin Lab Med 2006, 26, 803–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huesca-Gómez, C.; Carreón-Torres, E.; Nepomuceno-Mejía, T.; Sánchez-Solorio, M.; Galicia-Hidalgo, M.; Mejía, A.M.; et al. Contribution of cholesteryl ester transfer protein and lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase to HDL size distribution. Endocr Res 2004, 30, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez-Meavepeña, M.; Carreón-Torres, E.; López-Osorio, C.; García-Sánchez, C.; Gamboa, R.; Torres-Tamayo, M.; et al. The Srb1+ 1050T allele is associated with metabolic syndrome in children but not with cholesteryl ester plasma concentrations of high-density lipoprotein subclasses. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2012, 10, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, C.; Torres-Tamayo, M.; Juárez-Meavepeña, M.; López-Osorio, C.; Toledo-Ibelles, P.; Monter-Garrido, M.; et al. Lipid plasma concentrations of HDL subclasses determined by enzymatic staining on polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels in children with metabolic syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 2011, 412, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Ibelles, P.; García-Sánchez, C.; Ávila-Vazzini, N.; Carreón-Torres, E.; Posadas-Romero, C.; Vargas-Alarcón, G.; & Pérez-Méndez, O.; Pérez-Méndez O. Enzymatic assessment of cholesterol on electrophoresis gels for estimating HDL size distribution and plasma concentrations of HDL subclasses [S]. J Lipid Res 2010, 51, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, K.N.; Smolen, A.; Eckerson, H.W.; & La Du, B.N.; La Du, B. N. Purification of human serum paraoxonase/arylesterase. Evidence for one esterase catalyzing both activities. Drug Metab Dispos 1991, 19, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwak, S.A.; Wilson, J.L.; Chen, W.; Garcia-Rudaz, C.; Khaksari, M.; Cowley, M.A.; Enriori, P.J. Estradiol prevents fat accumulation and overcomes leptin resistance in female high-fat diet mice. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 4447–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Griffith, J.A.; Chasan-Taber, L.; Olendzki, B.C.; Jackson, E.; Stanek III, E.J.; et al. Association between dietary fiber and serum C-reactive protein. Am J Clin Nutr 2006, 83, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, V.M.R.; Wei, G.; Baird, B.C.; Murtaugh, M.; Chonchol, M.B.; Raphael, K.L.; et al. High dietary fiber intake is associated with decreased inflammation and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2012, 81, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, D.W.; Davis, C.K.; Irving, B.A.; Rodriguez, J.; Barrett, E.J.; Weltman, A.; et al. A high-carbohydrate, high-fiber meal improves endothelial function in adults with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2313–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhital, S.; Gidley, M.J.; & Warren, F.J.; Warren, F. J. Inhibition of α-amylase activity by cellulose: Kinetic analysis and nutritional implications. Carbohydr Polym 2015, 123, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, O.; Claggett, B.; Rodriguez, F.; Cai, J.; Moncrieft, A.E.; Garcia, K.; et al. Associations of insulin resistance with systolic and diastolic blood pressure: a study from the HCHS/SOL. Hypertension 2021, 78, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajani, S.; Curley, S.; & McGillicuddy, F.C.; McGillicuddy F. C. Unravelling HDL—looking beyond the cholesterol surface to the quality within. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macho-González, A.; Garcimartín, A.; Naes, F.; López-Oliva, M.E.; Amores-Arrojo, A.; González-Muñoz, M.J.; et al. Effects of fiber purified extract of carob fruit on fat digestion and postprandial lipemia in healthy rats. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 6734–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.C.; Inui, A.; & Chen, C.Y.; Chen, C. Y. Weight loss induced by whole grain-rich diet is through a gut microbiota-independent mechanism. World J Diabetes 2020, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camont, L.; Chapman, M.J.; & Kontush, A.; Kontush, A. Biological activities of HDL subpopulations and their relevance to cardiovascular disease. Trends Mol Med 2011, 17, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.S.; Khokhar, A.A.; May, H.T.; Kulkarni, K.R.; Blaha, M.J.; Joshi, P.H.; et al. HDL cholesterol subclasses, myocardial infarction, and mortality in secondary prevention: the Lipoprotein Investigators Collaborative. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskis, J.; Fink, H.; Nyberg, L.; Thyr, J.; Li, J.Y.; & Enejder, A.; Enejder, A. Plaque-associated lipids in Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue visualized by nonlinear microscopy. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 13489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kypreos, K.E.; & Zannis, VI.; Zannis, VI. Pathway of biogenesis of apolipoprotein E-containing HDL in vivo with the participation of ABCA1 and LCAT. Biochem J 2007, 403, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, A.M.; Koch, M.; Mendivil, C.O.; Furtado, J.D.; Tjønneland, A.; Overvad, K.; et al. Apolipoproteins E and CIII interact to regulate HDL metabolism and coronary heart disease risk. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e98045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.K.; Aroner, S.A.; Mukamal, K.J.; Furtado, J.D.; Post, W.S.; Tsai, M.Y.; et al. High-density lipoprotein subspecies defined by presence of flipoprotein C-III and incident coronary heart disease in four cohorts. Circulation 2018, 137, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; & Scott, J.E.; Scott, J. E. Estradiol enhances cell-associated paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity in vitro without altering PON1 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 397, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, S.; Alonso-Villaverde, C.; Coll, B.; Ferré, N.; Marsillach, J.; Aragonès, G.; et al. Serum paraoxonase-1 activity and concentration are influenced by human immunodeficiency virus infection. Atherosclerosis 2007, 194, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabresi, L.; Villa, B.; Canavesi, M.; Sirtori, C.R.; James, R.W.; Bernini, F.; & Franceschini, G.; Franceschini, G. An ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid concentrate increases plasma high-density lipoprotein 2 cholesterol and paraoxonase levels in patients with familial combined hyperlipidemia. Metabolism 2004, 53, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, M.; Origasa, H.; Matsuzaki, M.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Saito, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; et al. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet 2007, 369, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, A.; Rathnasamy, V.K.; Veerasamy, B.; Sangeetha, V.S.; Vellaichamy, J.; & Subbian, M.; Subbian, M. GUAVA (Psidium Guajava L.) SEED: A REVIEW ON NUTRITIONAL PROFILE, BIOACTIVE COMPOUNDS, FUNCTIONAL FOOD PROPERTIES, HEALTH BENEFITS AND INDUSTRIAL APPLICATIONS. FEB 2024, 33, 703–710. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, I. Factors affecting intestinal absorption of cholesterol and plant sterols and stanols. J Oleo Sci 2015, 64, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, D.; Mohammed, S.; & Hamed, I.; Hamed, I. Chia seeds oil enriched with phytosterols and mucilage as a cardioprotective dietary supplement towards inflammation, oxidative stress, and dyslipidemia. J Herbmed Pharmacol 2021, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.Y.; Yu, M.H.; Jung, Y.S.; Lee, S.P.; Shon, J.H.; & Lee, S.O.; Lee, S. O. Defatted safflower seed extract inhibits adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and improves lipid profiles in C57BL/6J ob/ob mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutr Res 2016, 36, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koza, J.; & Jurgoński, A.; Jurgoński, A. Partially defatted rather than native poppy seeds beneficially alter lipid metabolism in rats fed a high-fat diet. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 14171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Shao, H.; Bi, Q.; Chen, J.; & Ye, Z.; Ye, Z. Grape seed procyanidin B2 inhibits adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells by targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ with miR-483-5p involved mechanism. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 86, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | SHAM | OVX | OVX+DGS | OVX+GS |

| Body weight gain (g) | 28.00±9.57 | 63.00±25.16c | 57.20±23.73d | 32.83±3.82 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 145.20±10.60 | 166.94±9.35b | 138.89±17.78 | 149.38±10.80 |

| Media blood pressure (mmHg) | 121.30±6.50 | 144.31±10.35a,b | 102.42±21.22 | 122.70±12.01 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 37.01±8.42 | 40.88±5.59 | 33.77±2.84 | 32.42±6.18 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 49.42±14.62 | 55.63±10.04b,c | 28.72±5.25d | 37.83±6.95 |

| Phospholipids (mg/dL) | 115.46±15.67 | 134.29±19.88b,c | 80.37±12.88d | 99.81±8.06 |

| Non-HDL-c (mg/dL) | 9.15±6.90 | 7.56±3.92 | 15.64±1.17 | 4.86±4.09 |

| HDL lipid profile | SHAM | OVX | OVX+DGS | OVX+GS |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 27.86±4.59 | 33.32±2.42 | 18.13±2.31a,b,c | 27.55±6.90 |

| HDL-Tg (mg/dL) | 11.65±3.18 | 10.42±1.88 | 8.48±1.35 | 7.32±2.57 |

| HDL-PPL (mg/dL) | 58.80±13.86 | 64.71±4.38 | 52.06±5.31 | 61.66±12.68 |

| HDL-c/HDL-PPL ratio | 0.44±0.08 | 0.52±0.05 | 0.35±0.04b | 0.52±0.06 |

| HDL-Tg/HDL-PPL ratio | 0.18±0.09 | 0.16±0.04 | 0.17±0.03 | 0.14±0.04 |

| HDL subclasses | SHAM | OVX | OVX+DGS | OVX+GS |

| Protein (%) | ||||

| HDL 2b | 40.60±3.32 | 46.56±2.08 | 48.12±1.64a | 43.19±5.06 |

| HDL 2a | 13.06±2.46 | 12.03±1.20 | 13.26±2.12 | 12.23±2.28 |

| HDL 3a | 16.68±2.00 | 14.39±1.06 | 14.84±1.21 | 15.10±2.11 |

| HDL 3b | 8.25±0.92 | 8.23±0.73 | 7.48±1.21 | 8.29±1.14 |

| HDL 3c | 19.00±3.10 | 18.51±1.74 | 16.31±1.07 | 21.19±3.75c |

| Cholesterol (%) HDL 2b |

||||

| 40.53±1.36 | 43.46±2.33 | 36.82±1.60 | 39.74±2.93 | |

| HDL 2a HDL 3a HDL 3b HDL 3c |

12.09±0.53 | 11.77±0.44 | 11.04±1.38 | 11.79±0.82 |

| 17.05±1.42 | 15.65±2.10 | 19.71±4.05 | 17.19±1.63 | |

| 9.24±0.80 | 8.42±1.19 | 11.38±1.91b | 9.77±1.29 | |

| 21.09±3.20 | 20.69±2.26 | 27.18±1.30a,b | 23.83±2.52 | |

| Triglycerides (%) HDL 2b |

||||

| 34.90±3.37 | 36.94±2.34 | 39.53±3.08 | 36.50±2.75 | |

| HDL 2a | 11.13±1.13 | 11.15±0.65 | 11.75±0.53 | 10.58±1.28 |

| HDL 3a | 17.63±2.57 | 17.29±1.58 | 16.53±0.44 | 17.05±1.42 |

| HDL 3b | 9.49±0.41 | 9.28±0.95 | 9.00±0.54 | 9.63±1.19 |

| HDL 3c | 26.84±1.90 | 25.33±2.93 | 23.37±2.62 | 26.25±3.05 |

| Phospholipids (%) | ||||

| HDL 2b | 41.34±5.21 | 40.54±3.64 | 39.70±0.94 | 41.42±6.00 |

| HDL 2a | 10.87±0.76 | 10.39±0.78 | 11.97±1.06 | 10.01±0.88c |

| HDL 3a | 16.57±2.18 | 15.64±1.03 | 17.21±0.39 | 15.47±1.34 |

| HDL 3b | 8.99±1.01 | 9.27±0.80 | 8.92±0.74 | 9.00±0.78 |

| HDL 3c | 22.24±2.29 | 24.79±1.64 | 22.20±0.93 | 24.11±3.49 |

| Apolipoproteins | SHAM | OVX | OVX+DGS | OVX+GS |

| Apo AIV | 19.79±1.53 | 18.22±3.64 | 22.76±3.13 | 21.01±3.12 |

| Apo E | 19.92±3.26 | 18.95±1.85 | 13.70±3.38a,b,c | 21.68±3.33 |

| Apo AI | 44.17±3.20 | 45.60±5.38 | 41.79±7.65 | 39.93±8.10 |

| Apo AII | 8.71±1.12 | 8.99±1.58 | 8.34±3.28 | 9.18±1.30 |

| Apo C | 5.89±0.90 | 6.75±0.88 | 13.41±5.03a,b,c | 8.20±0.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).