3.1. North Marin WDN

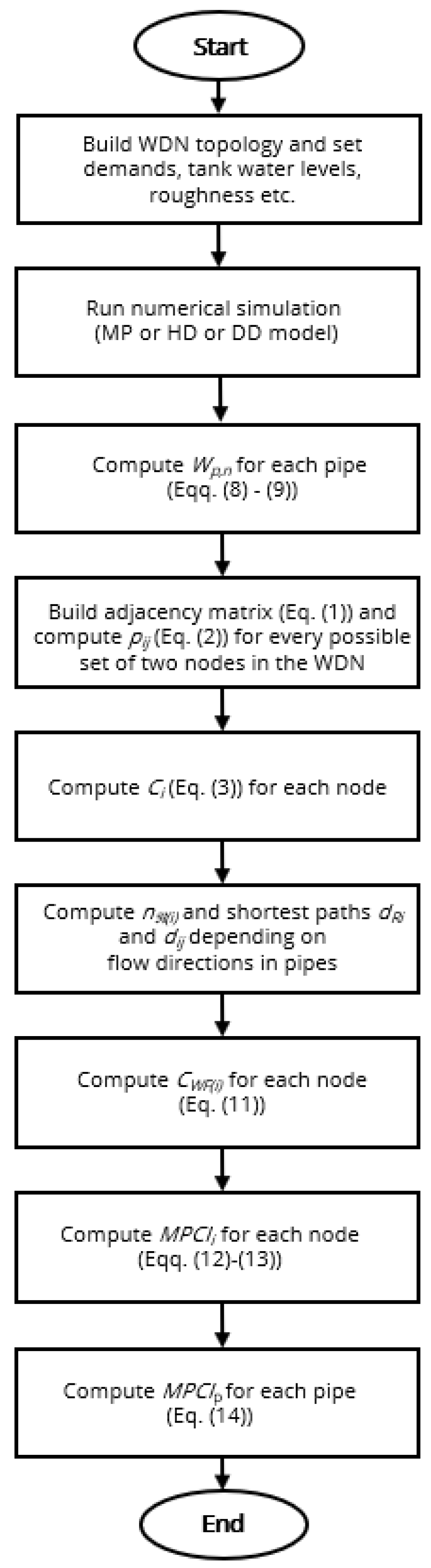

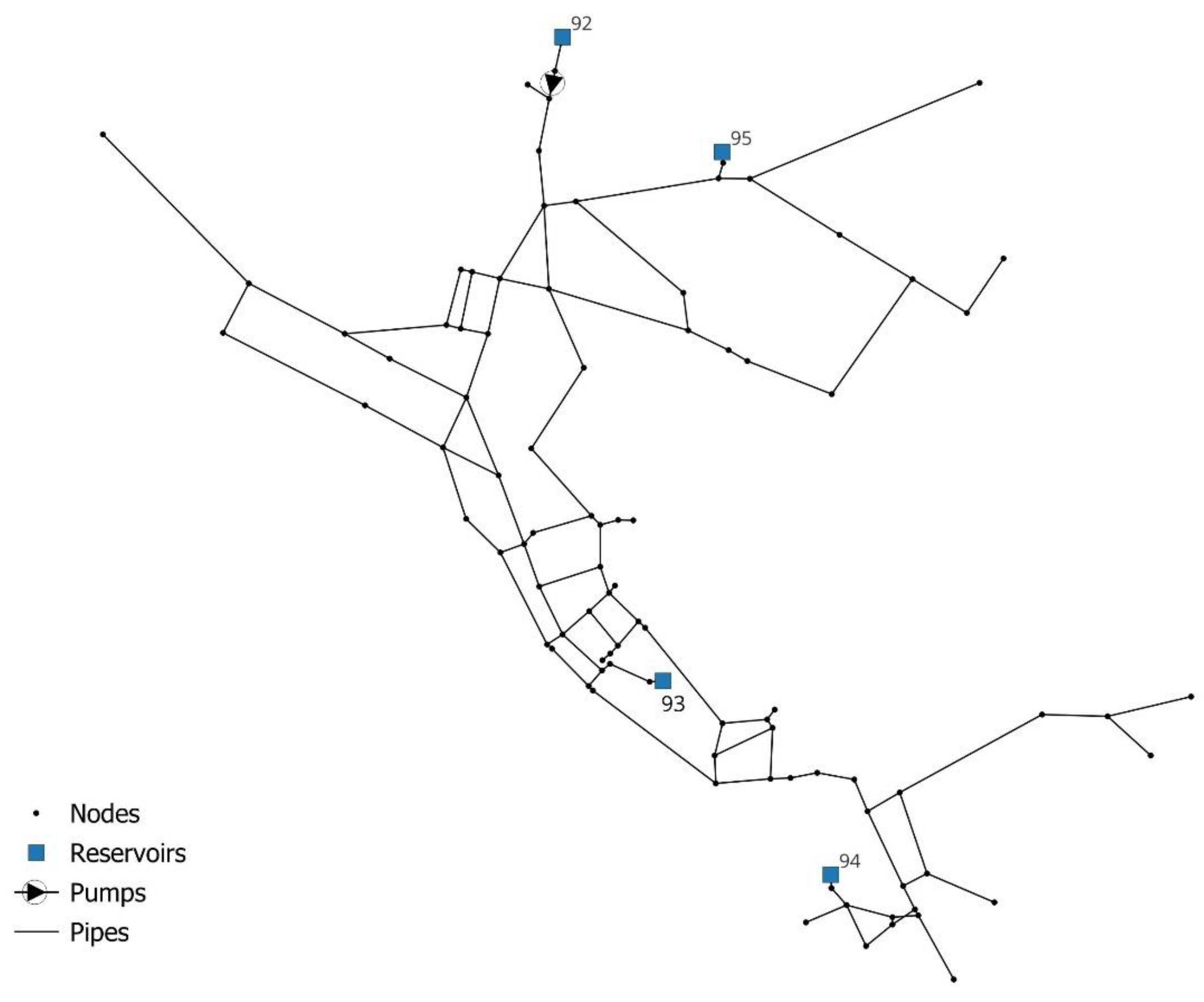

In order to test the validity of the proposed indicator the

Wp,n and

MPCIi,n values of all the nodes of three real-life WDNs have been computed. The first case is EPANET Net3 system [

22], based on North Marin WDN, which is one of the most used networks for validation available in literature; all related data can be found at online database (

https://uknowledge.uky.edu/wdsrd/). We analyzed Net3 configuration at 12:00 A.M., as shown in

Figure 5. The network has 95 nodes, 4 reservoirs (nodes 92, 93, 94, 95), 115 pipes and 1 pump.

A water scarcity scenario was simulated with the HD approach, where three reservoirs (93, 94, 95) were removed from the WDN and a needle valve with 94,3% opening degree was installed downstream reservoir 92. We compared the results (shown in

Figure 6) obtained using the proposed

Wp,n and

MPCIi,n formulations with the results obtained with the

Wp formulation and Hydraulic connectiveness criticality (

HCC) indicator, based on structural hole theory, as proposed by Marlim et. al. [

20] for WDNs criticality assessment (more details in Supplementary Material).

In

Figure 6 pipes are classified in six criticality groups, according to each different indicator (e.g., considering the WDN with 112 pipes, “1%–10%” refers to the first 11 (about 10%) pipes with the highest values of the computed indicator). In

Figure 6a and 6c results are shown respectively for

Wp,n and

MPCIp, while in

Figure 6b and 6d results obtained with respectively

Wp and

HCC formulations [

20] are shown:

Figure 6.

North Marin WDN pipes ranked in six criticality groups: e.g., considering the WDN with 112 pipes, “1%–10%” refers to the first 11 (about 10%) pipes with the highest values of the computed indicator. IDs of relevant pipes are depicted in black; head driven (HD) approach was used. Ranking according to: a)

Wp,n ; b)

Wp (Marlim et. al. [

20]) ; c)

MPCIp ; d)

HCC (Marlim et. al. [

20]).

Figure 6.

North Marin WDN pipes ranked in six criticality groups: e.g., considering the WDN with 112 pipes, “1%–10%” refers to the first 11 (about 10%) pipes with the highest values of the computed indicator. IDs of relevant pipes are depicted in black; head driven (HD) approach was used. Ranking according to: a)

Wp,n ; b)

Wp (Marlim et. al. [

20]) ; c)

MPCIp ; d)

HCC (Marlim et. al. [

20]).

We can observe in

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b that pipes with the highest

Wp,n values (between top 1% and top 10%) are the ones carrying most of the flow in the network and are located downstream of the reservoir and in the central branch of the WDN, while pipes located in peripherals areas generally have low positions in

Wp,n ranking.

Pipes 112 and 110, even if located near the reservoir, have zero

Wp value (

Figure 6b) due to zero nodal demand in each node of these pipes. Instead, with the new

Wp,n formulation (

Figure 6a), the same pipes rank in the first criticality group because, even though nodal demands are zero, flow rate in these pipes is the highest among all pipes. Eq. (8) correctly captures this criticality, which is also consistent with the topology of the WDN: in fact, a disconnection of these two pipes from the network would lead to hydraulic isolation of all the pipes downstream of the reservoir.

Another significant difference between

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b is about pipes 33 and 34 where nodal demand in one of their nodes, despite being relatively low, is not satisfied at all: again, this is properly taken into account by Eq. (8) and thus

Wp,n is able to provide detailed information about pipes where nodal demand is at least partially not satisfied.

The

MPCIp and

HCC rankings are shown in

Figure 6c and

Figure 6d respectively. Unlike

Wp,n, that takes into account only hydraulic parameters,

MPCIp and

HCC integrate topological and hydraulic characteristics and results provide evidence of that.

In

Figure 6c pipes 33 and 34 show moderate criticality values, albeit located near pipes with high positions in

MPCIp ranking. This can be explained by the relatively low fraction of the total water flow carried by them to the top right area of the WDN. The major fraction is carried instead by pipes 20 and 35, that are the only two connected to both the central branch of the WDN and the top right region: as expected,

MPCIp raises up to the first criticality group in spite of

Wp,n ranking (

Figure 6a) in the third group (21%-30%).

MPCIp and

HCC (

Figure 6d) criticality rankings are considerably different, especially for pipes 112 and 110 that have the lowest ranking according to

HCC formulation (

Figure 6d) as a result of the zero nodal demands of their nodes. This criticality also affects pipes downstream of pipe 112 (pipes 17, 18, 19) and lowers their criticality ranking. All these pipes instead, according to

MPCIp ranking (

Figure 6c), are in the first criticality group as they carry a large portion of flow, and again this is consistent with the topology of the WDN. Considerable differences can also be observed in pipes 24, 26, 29 (top right region in

Figure 6c and

Figure 6d) that are located in a peripheral region of the WDN: while their

HCC ranking is high (

Figure 6c), because of their distance from water source and the low number of connected pipes,

MPCIp ranking is low, because it gives higher criticality to pipes (like 20 and 35) required by pipes 24, 26 and 29 to remain connected to water sources.

With the aim of quantifying the differences shown in

Figure 6, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated and results are shown in

Table 1:

While a good correlation (

rs=0.536) exists between

Wp,n and

Wp (Marlim et. al. [

20]), mainly due to similar computed pipe flows, and also between

Wp,n and

MPCIp, instead

MPCIp and

HCC show completely different trends (

rs=-0.44), in compliance with criticality rankings depicted in

Figure 6c and

Figure 6d, because of nodes with zero nodal demands as described above.

In order to give a perspective about how the computed results could lead to a signification variation in water quality, simulations of Net3 were carried out considering a realistic 24h demand pattern, provided in Supplementary Material. Results indicate that, within 24 hours, the velocities in 106 pipes of the 112 pipes are subject to an increase up to 203%. Following Braga et al. [

23], we assume that a significant daily velocity variation can lead to systematic detachment of material accumulated over the pipe walls, especially when shear stress on the walls increases significantly. This effect could become more remarkable when a WDN operates for a larger period of time (e.g., during a water scarcity scenario) with several pipes with zero flow rate: when the network returns to regular operating conditions, this would lead to the detachment of all the material accumulated on pipe walls during the previous water scarcity period.

From this first test it is clear that MPCIp accurately integrates hydraulic and topological features of the WDN although even Wp,n alone provides significant insights, especially for free surface flow pipes, that can lead to a significant degradation of the quality of the delivered water.

3.2. Campofelice di Roccella WDN

The second case study is the new WDN designed for the “Campofelice di Roccella” residential area of Sicily, in Italy, shown in

Figure 7: the network is modeled with 1 reservoir, 128 nodes and 177 pipes and in the design scenario the flow rate leaving the reservoir is

Qsupply =39.2 l/s. In this case results obtained with MP and HD approaches for the hydraulic computations have been compared (for both the proposed

Wp,n and

MPCIp), in order to highlight the relevant effect of the properly adopted hydraulic solution. In the analyzed water scarcity scenario, a reduced water supply was considered, with a corresponding flow rate Q

supply =30.4 l/s (about 75% of the design water supply) obtained through a needle valve located downstream of the reservoir and a water leakage occurring in each internal node, with a total leakage

Qleakage=5.2 l/s (see Supplementary Material for network data).

In

Figure 7a and

Figure 7b results provided respectively by MP and HD model are shown:

Figure 7.

Free surface flow pipes and no flow rate pipes computed by a) MP model and b) HD model for Campofelice di Roccella WDN.

Figure 7.

Free surface flow pipes and no flow rate pipes computed by a) MP model and b) HD model for Campofelice di Roccella WDN.

In this scenario remarkable differences appear between the two models: while the HD model (

Figure 7b) provides zero pipes with no flow rate, the MP model (

Figure 7a) provides 13 pipes with free surface flow and 36 pipes with no flow rate, which represent about 20% of the total number of pipes in the WDN. These results directly impact

Wp,n and

MPCIp ranking for both models, as shown in

Figure 8:

The most critical pipes for Wp,n and MPCIp rankings are, as expected, the ones near the reservoir and in the central area of the WDN, followed in the ranking by their adjacent pipes.

In particular

Wp,n rankings do not differ significantly between MP (

Figure 8a) and HD (

Figure 8b) models in key regions of the network, due to the high number of pipes where nodal demands of their nodes are not partially or completely satisfied: this shows clearly how

Wp formulation of Eq. (8) is able to identify critical pipes from an hydraulic point of view and it is not strongly affected by the adopted hydraulic model, although pipes where free surface flow occurs generally have an higher ranking with MP model (

Figure 8a) than with the HD one (

Figure 8b). Observe that, due to water leakage in nodes,

qp increases in some pipes and

Wp,n increases as well: this is consistent because criticality of these pipes has to take into account the effect of leakage; as a consequence, only the actual nodal flow, excluding leakages, is considered in

Qa,i and

Qa,j of Eq. (8).

Figure 8.

Campofelice di Roccella WDN pipes ranked in six criticality groups depending on the considered indicator: e.g., considering the WDN with 177 pipes, “1%–10%” refers to the first 17 (about 10%) pipes with the highest values of the computed indicator. IDs of relevant pipes are depicted in black. Ranking according to: a) Wp,n (MP approach) ; b) Wp,n (HD approach) ; c) MPCIp (MP approach) ; d) MPCIp (HD approach).

Figure 8.

Campofelice di Roccella WDN pipes ranked in six criticality groups depending on the considered indicator: e.g., considering the WDN with 177 pipes, “1%–10%” refers to the first 17 (about 10%) pipes with the highest values of the computed indicator. IDs of relevant pipes are depicted in black. Ranking according to: a) Wp,n (MP approach) ; b) Wp,n (HD approach) ; c) MPCIp (MP approach) ; d) MPCIp (HD approach).

However, the results provided by

MPCIp offer a very different perspective on the criticality ranking: in fact, according to HD model (

Figure 8d), there is an entire group of pipes, located in the central WDN area (identified by the dotted box in

Figure 8d), with a rank between the third and fifth group of criticality. This is because HD model is unable to estimate the zero flow rate in this area, computed instead by the MP model as shown before in

Figure 7a.

According to the HD model, these pipes have a major relevance, because they carry the major fraction of flow to the upper part of the WDN. The pipes in the external areas of the network are instead ranked in the least critical group (49, 48, 86, 101, 100, 119 on the left in

Figure 8d).

The MP model, on the opposite (

Figure 8c), is able to detect free surface flow pipes and in particular pipes with zero flow rate, and this leads to substantially different results: a significant variation in criticality ranking affects almost all the pipes in the central region of the WDN (dotted box in

Figure 8c), that rank in the least criticality group even though, from just an hydraulic point of view, they are quite critical (as attested by high

Wp,n ranking in

Figure 8a). These pipes are in fact no more essential in the considered scenario, because a large part of the entering flow is redirected to a different part of the network, specifically to pipes on the left side (49, 48, 86, 101, 100, 119). All these pipes show now greater relevance and they are essential for the water supply of the upper part of the network that, according to the MP model, cannot be supplied by the central WDN region anymore.

This relevant difference in criticality ranking is caused by several adjacent pipes in the central region with zero flow rate: the nodes connecting these pipes will have a zero CWF value (Eq. (11)), because their number nℜ of reachable nodes is equal to zero and, as consequence, their MPCIi decreases dramatically or even drops to zero. This also proves that CWF(i) is necessary in Eq. (12) because otherwise, if the influence of node i were only given by C(i)-1 (and not by C(i)-1CWF(i)) than node i would always have much higher influence than all the other connected nodes (given by ) due to the higher order or magnitude of C(i)-1.

A final consideration concerns pipe 27 which, despite being in the first criticality group in

Wp,n ranking (

Figure 8a), in

MPCIp ranking is in the last group (

Figure 8c): this major variation is the effect of zero or low flow rate in all the pipes connected to pipe 27. This is correctly taken into account by

MPCIp formulation (Eq. 12); again, as mentioned before, low

MPCIp ranking suggests that pipe 27 role is not fundamental for the WDN in the analyzed scenario.

Spearman’s coefficient results are provided in

Table 2:

Results confirm what shown in

Figure 8, in particular a strong correlation (

rs=0.903) can be observed between the hydraulic weight

Wp,n and

MPCIp. The reason is that HD approach is unable to determine free surface flow pipes, unlike the MP approach, and this leads to a smaller correlation (

rs=0.478).

3.3. Marchi Rural WDN

A third test case is the Marchi Rural water distribution network in Australia, based on a real irrigation system, which can be classified as a transmission dense-loop network, unlike the first two analyzed WDNs. The network has 2 reservoirs, 380 nodes and 477 pipes; data can be found at online database (

https://uknowledge.uky.edu/wdsrd/).

In this test only a regular scenario, where all nodal demands are satisfied, was analyzed, and the HD approach was used for the hydraulic model.

In

Figure 9a comparison between the hydraulic weight computed according to Marlim et. al. [

20] and according to the new formulation of Eq. (9) can be observed:

Major differences are evident between

Figure 9a and

Figure 9b and this is mainly due to the large number of nodes with zero nodal demand. In fact, when both nodes of one pipe have zero demand, the computed pipe hydraulic weight (Marlim et. al. [

20]) will always be zero, regardless of the pipe flow which instead could be very high, especially near the two reservoirs (R1 and R2) and in critical pipes connecting separated areas of the WDN. Because of this, in

Figure 9a the real hydraulic dynamics of the network cannot be observed, and the most critical pipes (depicted in red in

Figure 9a) are always the ones located in the most peripherical areas of the WDN, irrespective of every other parameter.

Figure 9.

Marchi Rural WDN pipes ranked in six criticality groups depending on the considered indicator: e.g., considering the WDN with 477 pipes, “1%–10%” refers to the first 47 (about 10%) pipes with the highest values of the computed indicator. IDs of relevant pipes are depicted in black; head driven (HD) approach was used. Ranking according to: a)

Wp (Marlim et. al. [

20]) ; b)

Wp,n.

Figure 9.

Marchi Rural WDN pipes ranked in six criticality groups depending on the considered indicator: e.g., considering the WDN with 477 pipes, “1%–10%” refers to the first 47 (about 10%) pipes with the highest values of the computed indicator. IDs of relevant pipes are depicted in black; head driven (HD) approach was used. Ranking according to: a)

Wp (Marlim et. al. [

20]) ; b)

Wp,n.

Formulation of Eq. (9) instead correctly captures the hydraulic dynamics and, as expected, the most critical pipes are those located near the reservoirs, while medium criticality (between the top 21%–30% and top 31%–40% Wp,n) is assigned to pipes acting as a bridge between different regions of the network.

This test clearly shows that the new formulation performs accurately even in scenarios where only few nodes have higher than zero demand; finally, even though only the HD approach was applied, results are consistent with water dynamics and again this proves that the new hydraulic weight does not necessarily need to always rely on MP approach.

Finally, computed Spearman’s coefficient is

rs=0.323, in compliance with the large divergence between

Figure 9a and

Figure 9b.