Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

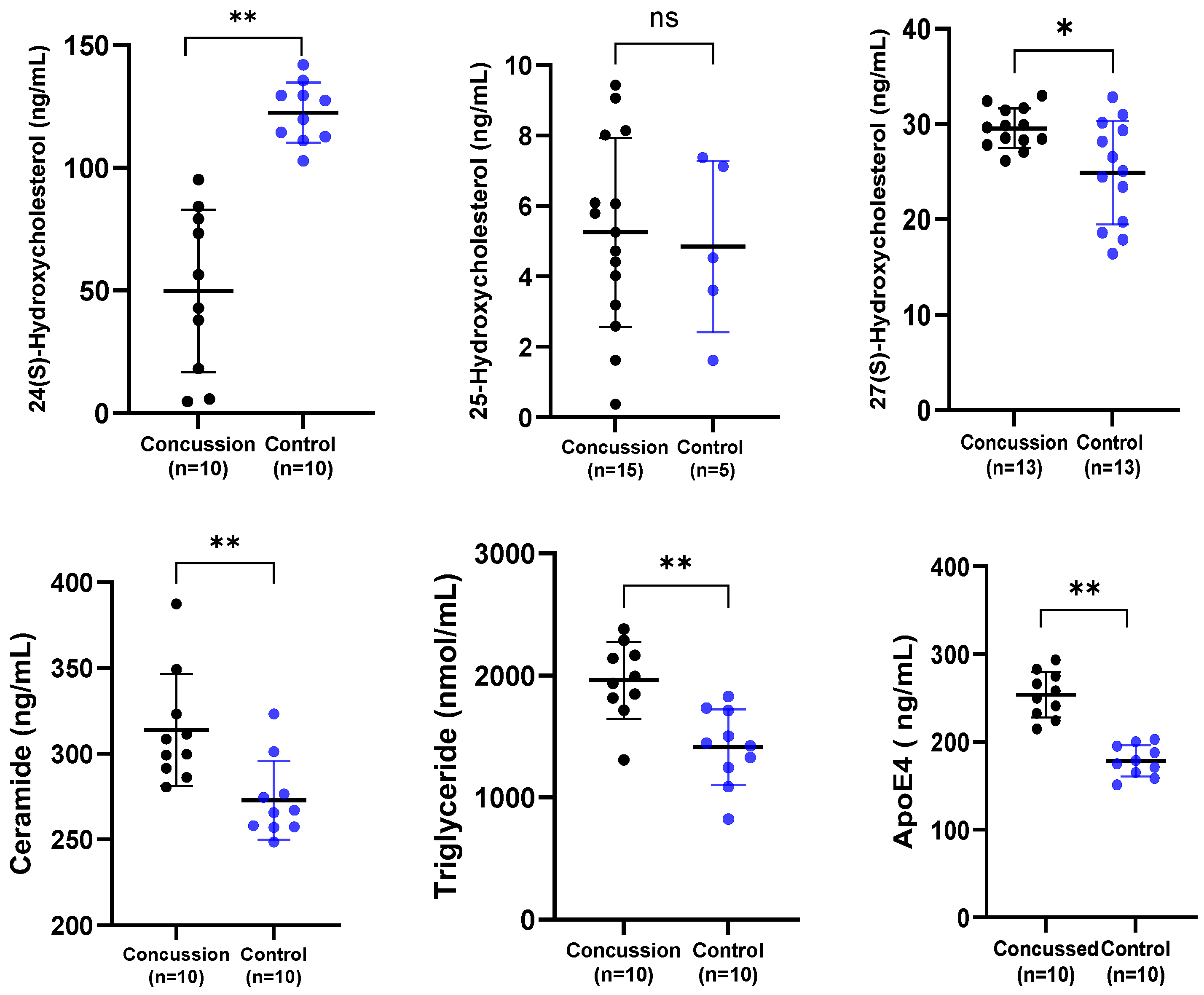

2.1. Serum Biomarker Levels in Concussed and Control Groups

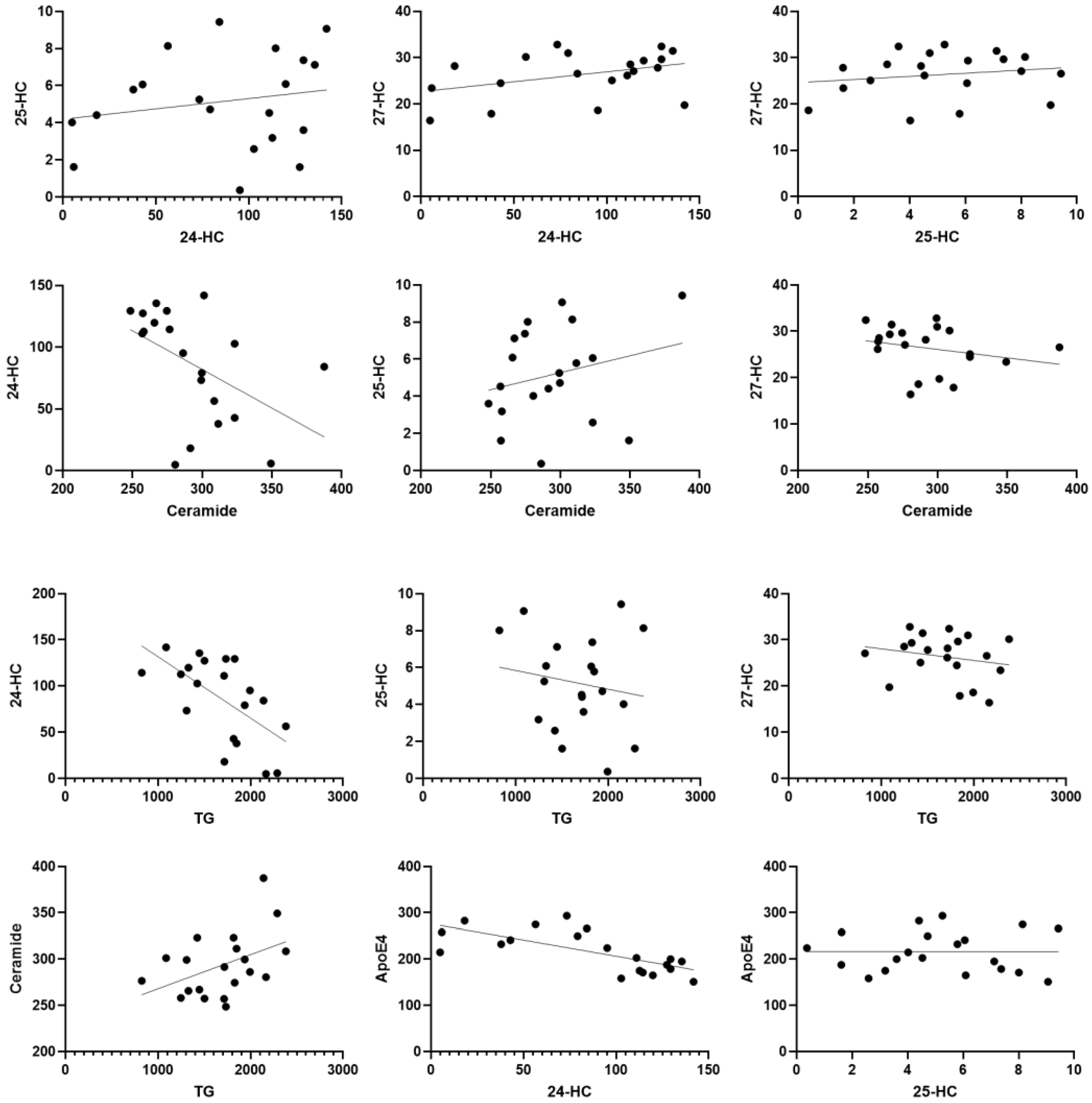

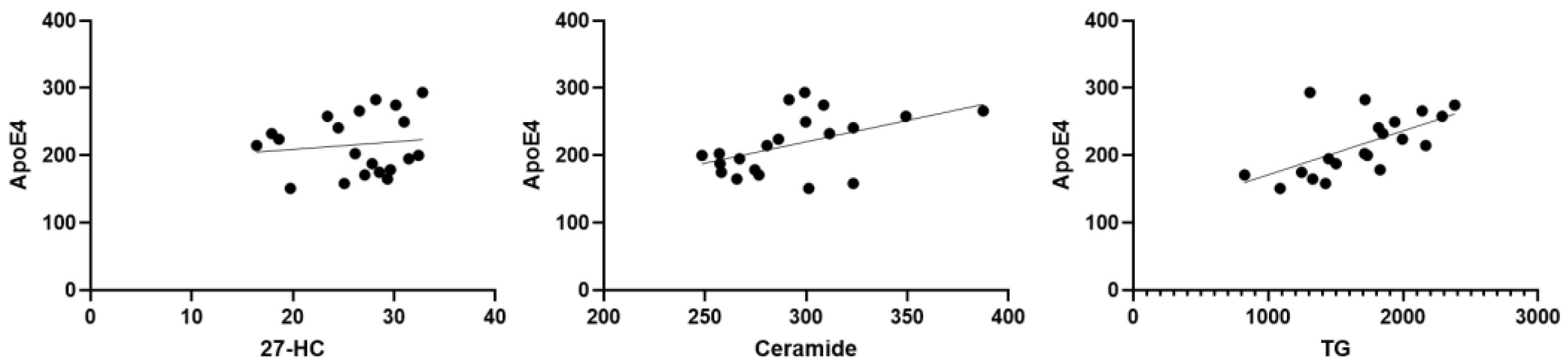

2.2. Correlations Among Biomarkers

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Setting

4.2. Study Participants

4.3. Biomarker Assays

4.4. ELISA Assays

4.5. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hind, K.; Konerth, N.; Entwistle, I.; Theadom, A.; Lewis, G.; King, D.; Chazot, P.; Hume, P. Cumulative sport-related injuries and longer term impact in retired male Elite-and Amateur-Level rugby code athletes and non-contact athletes: A retrospective study. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 2051–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, N.A. The neurophysiology of concussion. Prog. Neurobiol. 2002, 67, 281–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stillman, A.; Alexander, M.; Mannix, R.; Madigan, N.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Meehan, W.P. Concussion: Evaluation and management. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2017, 84, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, L.; Cristofori, I.; Weaver, S.M.; Chau, A.; Portelli, J.N.; Grafman, J. Cognitive decline in older adults with a history of traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.N.; Broglio, S.P. Long-term effects of sport concussion on cognitive and motor performance: A review. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2018, 132, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, K.; Konerth, N.; Entwistle, I.; Hume, P.; Theadom, A.; Lewis, G.; King, D.; Goodbourn, T.; Bottiglieri, M.; Ferraces-Riegas, P.; et al. Mental health and wellbeing of retired elite and amateur rugby players and non-contact athletes and associations with sports-related concussion: The UK Rugby Health Project. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, W.T.; Siu, A.M.; Ahn, H.J.; Chang, B.L.; Murata, N.M. Incidence and risk of concussions in youth athletes: Comparisons of age, sex, concussion history, sport, and football position. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2019, 34, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.; Broglio, S.P.; O′Grady, M.; Wilson, F. History of sport-related concussion and long-term clinical cognitive health outcomes in retired athletes: A systematic review. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 132–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, Z.Y.; Thomas, L.C.; Simon, J.E.; McCrea, M.; Guskiewicz, K.M. Association between history of multiple concussions and health outcomes among former college football players: 15-year follow-up from the NCAA concussion study (1999–2001). Am. J. Sports Med. 2018, 46, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacorte, E.; Ferrigno, L.; Leoncini, E.; Corbo, M.; Boccia, S.; Vanacore, N. Physical activity, and physical activity related to sports, leisure and occupational activity as risk factors for ALS: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 66, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, E.J.; Hein, M.J.; Baron, S.L.; Gersic, C.M. Neurodegenerative causes of death among retired National Football League players. Neurology 2012, 79, 1970–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guskiewicz, K.M.; Marshall, S.W.; Bailes, J.; McCrea, M.; Cantu, R.C.; Randolph, C.; Jordan, B.D. Association between recurrent concussion and late-life cognitive impairment in retired professional football players. Neurosurgery 2005, 57, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halicki, M.J.; Hind, K.; Chazot, P.L. Blood-based biomarkers in the diagnosis of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Research to date and future directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, N.; Fitzgerald, M.; Hume, P.; Hellewell, S.; Horncastle, A.; Anyaegbu, C.; Papini, M.G.; Hargreaves, N.; Halicki, M.; Entwistle, I.; Hind, K.; Chazot, P. Concussion-related biomarker variations in retired rugby players and implications for neurodegenerative disease risk: the UK Rugby Health Study. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25, 7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posse de Chaves, E.; Narayanaswami, V. Apolipoprotein E and cholesterol in aging and disease in the brain. Future Lipidol 2008, 3, 505–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konings, S.C.; Torres-Garcia, L.; Martinsson, I.; Gouras, G.K. Astrocytic and neuronal apolipoprotein E isoforms differentially affect neuronal excitability. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2021, 15, 734001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mahley, R.W. Apolipoprotein E: structure and function in lipid metabolism, neurobiology, and Alzheimer's diseases. Neurobiology of disease 2014, 72, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, C.A.; Zeiler, F.A.; Newcombe, V.; Synnot, A.; Steyerberg, E.; Gruen, R.L.; Rosand, J.; Palotie, A.; Maas, A.I.; Menon, D.K. Apolipoprotein E4 polymorphism and outcomes from traumatic brain injury: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of neurotrauma 2021, 38, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, K.; Han, X.; Chung, J.; Cherry, J.D.; Baucom, Z.; Saltiel, N.; Nair, E.; Abdolmohammadi, B.; Uretsky, M.; Khan, M.M.; Shea, C. Association of APOE genotypes and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. JAMA neurology 2022, 79, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Calle, R.; Konings, S.C.; Frontiñán-Rubio, J.; García-Revilla, J.; Camprubí-Ferrer, L.; Svensson, M.; Martinson, I.; Boza-Serrano, A.; Venero, J.L.; Nielsen, H.M.; Gouras, G.K. APOE in the bullseye of neurodegenerative diseases: impact of the APOE genotype in Alzheimer’s disease pathology and brain diseases. Molecular neurodegeneration 2022, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.; Kim, J.; Stewart, F.R.; Jiang, H.; DeMattos, R.B.; Patterson, B.W.; Fagan, A.M.; Morris, J.C.; Mawuenyega, K.G.; Cruchaga, C.; Goate, A.M. Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-β peptide clearance. Science translational medicine 2011, 3, 89ra57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xia, Y.; Gui, Y. Neuronal ApoE4 in Alzheimer’s disease and potential therapeutic targets. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2023, 15, 1199434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonski, A.M.; Warren, L.; Usenovic, M.; Zhou, H.; Sugam, J.; Parmentier-Batteur, S.; Voleti, B. Astrocytic expression of the Alzheimer’s disease risk allele, ApoEε4, potentiates neuronal tau pathology in multiple preclinical models. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L. Human ApoE isoforms differentially modulate brain glucose and ketone body metabolism: implications for Alzheimer's disease risk reduction and early intervention. Journal of Neuroscience 2018, 38, 6665–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, H.C. Roles of apoE4 on the pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease and the potential therapeutic approaches. Cellular and molecular neurobiology 2023, 43, 3115–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, B.S.; Villapol, S.; Sloley, S.S.; Barton, D.J.; Parsadanian, M.; Agbaegbu, C.; Stefos, K.; McCann, M.S.; Washington, P.M.; Rodriguez, O.C.; Burns, M.P. Apolipoprotein E4 impairs spontaneous blood brain barrier repair following traumatic brain injury. Molecular neurodegeneration 2018, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.D.; Winkler, E.A.; Singh, I.; Sagare, A.P.; Deane, R.; Wu, Z.; Holtzman, D.M.; Betsholtz, C.; Armulik, A.; Sallstrom, J.; Berk, B.C. Apolipoprotein E controls cerebrovascular integrity via cyclophilin A. Nature 2012, 485, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, A.; Nation, D.A.; Sagare, A.P.; Barisano, G.; Sweeney, M.D.; Chakhoyan, A.; Pachicano, M.; Joe, E.; Nelson, A.R.; D’Orazio, L.M.; Buennagel, D.P. APOE4 leads to blood–brain barrier dysfunction predicting cognitive decline. Nature 2020, 581, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, V.C.; Clark, A.L.; Sorg, S.F.; Evangelista, N.D.; Werhane, M.L.; Bondi, M.W.; Schiehser, D.M.; Delano-Wood, L. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 genotype is associated with reduced neuropsychological performance in military veterans with a history of mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology 2018, 40, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, M.S.; Pálovics, R.; Munson, C.N.; Long, C.; Johansson, P.K.; Yip, O.; Dong, W.; Rawat, E.; West, E.; Schlachetzki, J.C.; Tsai, A. APOE4/4 is linked to damaging lipid droplets in Alzheimer’s disease microglia. Nature 2024, 628, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muza, P.; Bachmeier, C.; Mouzon, B.; Algamal, M.; Rafi, N.G.; Lungmus, C.; Abdullah, L.; Evans, J.E.; Ferguson, S.; Mullan, M.; Crawford, F. APOE genotype specific effects on the early neurodegenerative sequelae following chronic repeated mild traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience 2019, 404, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, E.; Subramaniam, S.; Murphy, R.C.; Nishijima, M.; Raetz, C.R.; Shimizu, T.; Spener, F.; Van Meer, G.; Wakelam, M.J.; Dennis, E.A. Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids1. Journal of lipid research 2009, 50, S9–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, K.D.; Zsombok, A.; Eckel, R.H. Lipid processing in the brain: a key regulator of systemic metabolism. Frontiers in endocrinology 2017, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermenati, G.; Mitro, N.; Audano, M.; Melcangi, R.C.; Crestani, M.; De Fabiani, E.; Caruso, D. Lipids in the nervous system: from biochemistry and molecular biology to patho-physiology. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2015, 1851, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, X.; Yu, W.; Chen, S.; Ying, J.; Hua, F. Lipid metabolism and storage in neuroglia: role in brain development and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell & bioscience 2022, 12, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Nessel, I.; Michael-Titus, A.T. Lipid profiling of brain tissue and blood after traumatic brain injury: A review of human and experimental studies. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Academic Press, April 2021; Volume 112, pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- de Freitas, F.A.; Levy, D.; Zarrouk, A.; Lizard, G.; Bydlowski, S.P. Impact of oxysterols on cell death, proliferation, and differentiation induction: current status. Cells 2021, 10, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.Y.; Linsenbardt, A.J.; Emnett, C.M.; Eisenman, L.N.; Izumi, Y.; Zorumski, C.F.; Mennerick, S. 24 (S)-Hydroxycholesterol as a modulator of neuronal signaling and survival. The Neuroscientist 2016, 22, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.; Toral-Rios, D.; Yu, J.; Paul, S.M.; Cashikar, A.G. 25-hydroxycholesterol promotes brain cytokine production and leukocyte infiltration in a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwarha, G.; Ghribi, O. Does the oxysterol 27-hydroxycholesterol underlie Alzheimer's disease–Parkinson's disease overlap? Experimental gerontology 2015, 68, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T.; Miyanoki, Y.; Urano, Y.; Uehara, M.; Saito, Y.; Noguchi, N. Effect of vitamin E on 24 (S)-hydroxycholesterol-induced necroptosis-like cell death and apoptosis. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2017, 169, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, V.; Masterman, T.; Diczfalusy, U.; De Luca, G.; Hillert, J.; Björkhem, I. Changes in human plasma levels of the brain specific oxysterol 24S-hydroxycholesterol during progression of multiple sclerosis. Neuroscience letters 2002, 331, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkhem, I.; Lövgren-Sandblom, A.; Leoni, V.; Meaney, S.; Brodin, L.; Salveson, L.; Winge, K.; Pålhagen, S.; Svenningsson, P. Oxysterols and Parkinson's disease: evidence that levels of 24S-hydroxycholesterol in cerebrospinal fluid correlates with the duration of the disease. Neuroscience letters 2013, 555, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Fan, S.; Romo, A.R.; Xu, D.; Ferriero, D.M.; Jiang, X. Serum 24S-hydroxycholesterol predicts long-term brain structural and functional outcomes after hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal mice. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2021, 41, 312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Odnoshivkina, U.G.; Kuznetsova, E.A.; Petrov, A.M. 25-hydroxycholesterol as a signaling molecule of the nervous system. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2022, 87, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.M.; Noh, M.Y.; Kim, H.; Cheon, S.Y.; Lee, K.M.; Lee, J.; Cha, E.; Park, K.S.; Lee, K.W.; Sung, J.J.; Kim, S.H. 25-Hydroxycholesterol is involved in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 11855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xi, Y.; Yu, H.; An, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, T.; Xiao, R. 27-hydroxycholesterol promotes Aβ accumulation via altering Aβ metabolism in mild cognitive impairment patients and APP/PS1 mice. Brain Pathology 2019, 29, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuolikainen, A.; Acimovic, J.; Lövgren-Sandblom, A.; Parini, P.; Andersen, P.M.; Björkhem, I. Cholesterol, oxysterol, triglyceride, and coenzyme Q homeostasis in ALS. Evidence against the hypothesis that elevated 27-hydroxycholesterol is a pathogenic factor. PloS one 2014, 9, p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencarelli, C.; Martinez–Martinez, P. Ceramide function in the brain: when a slight tilt is enough. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2013, 70, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.R.; Jin, H.K.; Bae, J.S. Diverse roles of ceramide in the progression and pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodia, A.; Romaus-Sanjurjo, D.; Aramburu-Núñez, M.; Álvarez-Rafael, D.; Vázquez-Vázquez, L.; Camino-Castiñeiras, J.; Leira, Y.; Pías-Peleteiro, J.M.; Aldrey, J.M.; Sobrino, T.; Ouro, A. Ceramide/sphingosine 1-phosphate axis as a key target for diagnosis and treatment in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 8082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringali, C.; Giussani, P. Ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate in neurodegenerative disorders and their potential involvement in therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Holtzman, D.M.; McKeel, W.D., Jr.; Kelley, J.; Morris, J.C. Substantial sulfatide deficiency and ceramide elevation in very early Alzheimer's disease: potential role in disease pathogenesis. Journal of neurochemistry 2002, 82, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, B.; Gong, C.X.; Schuchman, E.H. Deregulation of sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of aging 2010, 31, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Irigoyen, J.; Cartas-Cejudo, P.; Iruarrizaga-Lejarreta, M.; Santamaría, E. Alteration in the cerebrospinal fluid lipidome in Parkinson’s disease: a post-mortem pilot study. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbacci, D.C.; Roux, A.; Muller, L.; Jackson, S.N.; Post, J.; Baldwin, K.; Hoffer, B.; Balaban, C.D.; Schultz, J.A.; Gouty, S.; Cox, B.M. Mass spectrometric imaging of ceramide biomarkers tracks therapeutic response in traumatic brain injury. ACS chemical neuroscience 2017, 8, 2266–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, J.O.; Algamal, M.; Leary, P.; Abdullah, L.; Mouzon, B.; Evans, J.E.; Mullan, M.; Crawford, F. Converging and differential brain phospholipid dysregulation in the pathogenesis of repetitive mild traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2019, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, X.; Song, Q.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; Chen, T. The relevance between abnormally elevated serum ceramide and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease model mice and its mechanism. Psychopharmacology 2024, 241, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernath, M.M.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Nho, K.; Barupal, D.K.; Fiehn, O.; Baillie, R.; Risacher, S.L.; Arnold, M.; Jacobson, T.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Shaw, L.M. Serum triglycerides in Alzheimer disease: Relation to neuroimaging and CSF biomarkers. Neurology 2020, 94, e2088–e2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, V.; Frazier, D.T.; Bettcher, B.M.; Jastrzab, L.; Chao, L.; Reed, B.; Mungas, D.; Weiner, M.; DeCarli, C.; Chui, H.; Kramer, J.H. Triglycerides are negatively correlated with cognitive function in nondemented aging adults. Neuropsychology 2017, 31, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Shang, S.; Li, P.; Chen, C.; Dang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Huo, K.; Deng, M.; Wang, J.; Qu, Q. The gender-and age-dependent relationships between serum lipids and cognitive impairment: a cross-sectional study in a rural area of Xi’an, China. Lipids in Health and Disease 2019, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, J.R.; Lim, S.W.; Zheng, H.X.; Ho, C.H.; Chang, C.H.; Chio, C.C.; Wee, H.Y. Triglyceride is a good biomarker of increased injury severity on a high fat diet rat after traumatic brain injury. Neurochemical Research 2020, 45, 1536–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnefeld, L.; Vogel, A.; Gurke, R.; Geisslinger, G.; Schäfer, M.K.; Tegeder, I. Phosphatidylethanolamine deficiency and triglyceride overload in perilesional cortex contribute to non-goal-directed hyperactivity after traumatic brain injury in mice. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Xu, D.; Peng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, J.; Crutcher, K.A. Meta-analysis of APOE 4 allele and outcome after traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurotrauma 2008, 25, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellstrøm, T.; Andelic, N.; Holthe, Ø.Ø.; Helseth, E.; Server, A.; Eiklid, K.; Sigurdardottir, S. APOE-ε4 is associated with reduced verbal memory performance and higher emotional, cognitive, and everyday executive function symptoms two months after mild traumatic brain injury. Frontiers in neurology 2022, 13, 735206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.T.; Hsiao, T.; Hsieh, C.J.; Chiang, Y.H.; Yen, T.C.; Chiu, W.T.; Lin, K.J.; Hu, C.J. Accumulation of amyloid in cognitive impairment after mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of the neurological sciences 2015, 349, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.Y.J.; Seet, R.C.; Huang, S.H.; Long, L.H.; Halliwell, B. Different patterns of oxidized lipid products in plasma and urine of dengue fever, stroke, and Parkinson's disease patients: cautions in the use of biomarkers of oxidative stress. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2009, 11, 407–420. [Google Scholar]

- La Marca, V.; Maresca, B.; Spagnuolo, M.S.; Cigliano, L.; Dal Piaz, F.; Di Iorio, G.; Abrescia, P. Lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase in brain: Does oxidative stress influence the 24-hydroxycholesterol esterification? Neuroscience Research 2016, 105, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, M.F.; Vega, G.L.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Moore, C.; Madden, C.; Hudak, A.; Lütjohann, D. Plasma 24S-hydroxycholesterol and other oxysterols in acute closed head injury. Brain injury 2008, 22, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Fa, W.; Dong, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, C.; Liu, K.; Mao, M.; Zhu, M.; Liang, X.; Wang, N.; Ma, Y. Triglyceride–glucose index, Alzheimer's disease plasma biomarkers, and dementia in older adults: The MIND-China study. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2023, 15, p. [Google Scholar]

- Dunk, M.M.; Rapp, S.R.; Hayden, K.M.; Espeland, M.A.; Casanova, R.; Manson, J.E.; Shadyab, A.H.; Wild, R.; Driscoll, I. Plasma oxysterols are associated with serum lipids and dementia risk in older women. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2024, 20, 3696–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.B.; Sene, A.; Santeford, A.; Fujiwara, H.; Sidhu, R.; Ligon, M.M.; Shankar, V.A.; Ban, N.; Mysorekar, I.U.; Ory, D.S.; Apte, R.S. Oxysterol signatures distinguish age-related macular degeneration from physiologic aging. EBioMedicine 2018, 32, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli, M.N.; McDonald, J.G.; Thompson, B.M.; Arega, E.A.; Palys, T.J.; Rees, J.R.; Barry, E.L.; Baron, J.A. Association of demographic and health characteristics with circulating oxysterol concentrations. Journal of clinical lipidology 2022, 16, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leoni, V.; Long, J.D.; Mills, J.A.; Di Donato, S.; Paulsen, J.S.; members of the PREDICT-HD study group. Plasma 24S-hydroxycholesterol correlation with markers of Huntington disease progression. Neurobiology of disease 2013, 55, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teitsdottir, U.D.; Halldorsson, S.; Rolfsson, O.; Lund, S.H.; Jonsdottir, M.K.; Snaedal, J.; Petersen, P.H. Cerebrospinal fluid C18 ceramide associates with markers of Alzheimer’s disease and inflammation at the pre-and early stages of dementia. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2021, 81, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, D.; Chakrabarti, S.S.; Banerjee, A.; Sharma, P.; Biswas, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Serum 24-hydroxycholesterol in probable Alzheimer's dementia: Reexploring the significance of a tentative Alzheimer's disease biomarker. Aging Medicine 2019, 2, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaru, V.V.; Troncoso, J.; Wheeler, D.; Pletnikova, O.; Wang, J.; Conant, K.; Haughey, N.J. ApoE4 disrupts sterol and sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer's but not normal brain. Neurobiology of aging 2009, 30, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, P.A.; Theadom, A.; Lewis, G.N.; Quarrie, K.L.; Brown, S.R.; Hill, R.; Marshall, S.W. A comparison of cognitive function in former rugby union players compared with former non-contact-sport players and the impact of concussion history. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Hind, K.; Hume, P.; Singh, J.; Neary, J.P. Neurovascular coupling by functional near infra-red spectroscopy and sport-related concussion in retired rugby players: The UK rugby health project. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, I.; Francis, P.; Lees, M.; Hume, P.; Hind, K. Lean Mass, Muscle Strength, and Muscle Quality in Retired Rugby Players: The UK Rugby Health Project. Int. J. Sports Med. 2022, 43, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnoff, J.T.; Jelsing, E.J.; Smith, J. Biomarkers, genetics, and risk factors for concussion. PM&R 2011, 3, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.; Akonasu, H.; Shishkin, R.; Taghibiglou, C. Plasma soluble prion protein, a potential biomarker for sport-related concussions: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concussed Group N = 26 |

Control Group N = 19 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean ages | 39.32±6.44 | 47.19±12.11 |

| Mean ages at retirement | 26.56±4.89 | 33.77±9.24 |

| Mean years since retirement from the sport | 7.04±5.23 | 8.33±4.29 |

| Playing position | 4 prop, 3 hooker, 1 forward, 2 s row, 1 fly half, 4 center, 4 wing, 3 backward, 1 openside flanker, 1 blindside flanker, 2 lock. |

1 blindside flanker, 2 backwards, 1 wing, 1 number 8, 1 prop, 1 standoff, 12 non-athletes. |

| Mean weight | 100.2±11.14 | 86.53±15.47 |

| Mean height | 183.81±7.09 | 178.5±6.33 |

| Rugby league (RL) or union (RU) | 12(RL), 14 (RU) | 5(RU), 2(RL), 12 (N/A) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).