Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Factors Influencing Firms’ Ambidextrous Innovation

2.2. AI Technologies: Essence and Influence on Firms’ Innovation

2.3. The Role of Data in AI Application

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

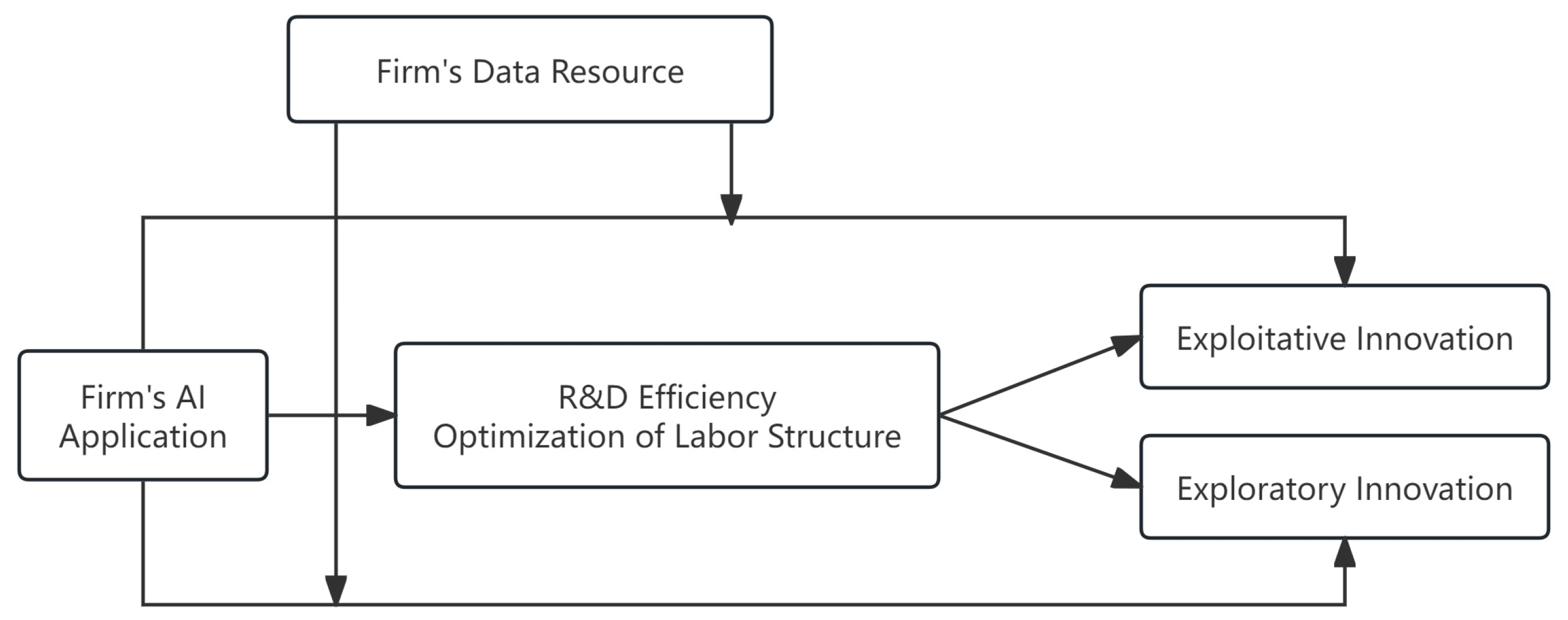

3.1. The Impact and Mechanism of Artificial Intelligence on Firms’ Ambidextrous Innovation

3.2. The Moderating Role of Firms’ Data Resource

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Data Source and Sample Selection

4.2. Description of Variables

4.2.1. Dependent Variables

4.2.2. Independent Variable

4.2.3. Moderating Variable

4.2.4. Control Variable

4.3. Model Specification

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

5.2. Benchmark Regression Results and Analysis

5.3. Robustness Checks

5.3.1. Test of Omitted Variable Bias

5.3.2. Test of Sample Selection Bias

5.3.3. Test of Instrumental Variable

5.3.4. Additional Robustness Checks

5.4. Mechanism Testing

5.5. Heterogeneity Test

5.5.1. Slack Resource Heterogeneity

5.5.2. Firms’ AI Foundation Heterogeneity

5.5.3. Industrial Competitiveness Heterogeneity

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Implications

7.1. Main Research Conclusions

7.2. Practical Implementations

7.2.1. Implications for Government

7.2.2. Implications for Firms

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Chen, Y. Does Artificial Intelligence Promote Firms’ Green Technological Innovation? Sustainability 2025, 17, 4900.

- Helfat, C.E.; Kaul, A.; Ketchen, D.J.; et al. Renewing the resource-based view: New contexts, new concepts, and new methods. Strategic Management Journal 2023, 44, 1357–1390.

- Murray, A.; Rhymer, J.; Sirmon, D.G. Humans and Technology: Forms of Conjoined Agency in Organizations. Academy of Management Review 2021, 46, 552–571.

- Raisch, S.; Krakowski, S. Artificial Intelligence and Management: The Automation–Augmentation Paradox. Academy of Management Review 2021, 46, 192–210.

- Gama, F.; Magistretti, S. Artificial intelligence in innovation management: A review of innovation capabilities and a taxonomy of AI applications. Journal of Product Innovation Management 2025, 42, 76–111.

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organization Science 1991, 2, 71–87.

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Van den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory Innovation, Exploitative Innovation, and Performance: Effects of Organizational Antecedents and Environmental Moderators. Management Science 2006, 52, 1661–1674.

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly 2005, 50, 329–366.

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; et al. Resource Orchestration to Create Competitive Advantage: Breadth, Depth, and Life Cycle Effects. Journal of Management 2011, 37, 1390–1412.

- Rosenkopf, L.; Nerkar, A. Beyond local search: boundary-spanning, exploration, and impact in the optical disk industry. Strategic Management Journal 2001, 22, 287–306.

- Lin, C.; Chang, C.C. A patent-based study of the relationships among technological portfolio, ambidextrous innovation, and firm performance. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2015, 27, 1193–1211.

- Limaj, E.; Bernroider, E.W.N. The roles of absorptive capacity and cultural balance for exploratory and exploitative innovation in SMEs. Journal of Business Research 2019, 94, 137-153.

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal 1997, 18, 509–533.

- Kinkel, S.; Baumgartner, M.; Cherubini, E. Prerequisites for the adoption of AI technologies in manufacturing – Evidence from a worldwide sample of manufacturing companies. Technovation 2022, 110. 102375.

- Wu, Q.; Qalati, S.A.; Tajeddini, K.; et al. The impact of artificial intelligence adoption on Chinese manufacturing enterprises’ innovativeness: new insights from a labor structure perspective. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2025, 125, 849–874.

- Wamba-Taguimdje, S.L.; Wamba, S.; Kamdjoug, J.R.K.; et al. Influence of artificial intelligence (AI) on firm performance: the business value of AI-based transformation projects. Business Process Management Journal 2020, 26, 1893–1924.

- Zebec, A.; Stemberger, M. Creating AI business value through BPM capabilities. Business Process Management Journal 2024, 30, 1–26.

- Dey, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Abadie, A.; et al. Artificial intelligence-driven supply chain resilience in Vietnamese manufacturing small- and medium-sized enterprises. International Journal of Production Research 2023, 62, 5417–5456.

- Saleem, I.; Hoque, S.; Tashfeen, R.; et al. The Interplay of AI Adoption, IoT Edge, and Adaptive Resilience to Explain Digital Innovation: Evidence from German Family-Owned SMEs. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2023, 18, 1419–1430.

- Guan, J.; Liu, N. Exploitative and exploratory innovations in knowledge network and collaboration network: A patent analysis in the technological field of nano-energy. Research Policy 2016, 45, 97–112.

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17, 99–120.

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 1984, 5, 171–180.

- Kemp, A. Competitive Advantage Through Artificial Intelligence: Toward a Theory of Situated AI. Academy of Management Review 2024, 49, 618–635.

- Barney, J.B.; Reeves, M. AI Won’t Give You a New Sustainable Advantage. Harvard Business Review 2024, 5, 72–79.

- Bresnahan, T.F.; Trajtenberg, M. General purpose technologies ‘Engines of growth’? Journal of Econometrics 1995, 65, 83–108.

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Game analysis on general purpose technology cooperative R&D with fairness concern from the technology chain perspective. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2023, 8, 100312.

- Cristofaro, M.; Giardino, P.L. Surfing the AI waves: the historical evolution of artificial intelligence in management and organizational studies and practices. Journal of Management History 2025.

- Hu, C.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X. Data assets, information uses, and operational efficiency. Applied Economics 2022, 54, 6887–6900.

- Felin, T.; Holweg, M. Theory Is All You Need: AI, Human Cognition, and Causal Reasoning. Strategy Science 2024, 9, 346–371.

- Lebovitz, S.; Lifshitz-Assaf, H.; Levina, N. To Engage or Not to Engage with AI for Critical Judgments: How Professionals Deal with Opacity When Using AI for Medical Diagnosis. Organization Science 2022, 33, 126–148.

- Paschen, U.; Pitt, C.; Kietzmann, J. Artificial intelligence: Building blocks and an innovation typology. Business Horizons 2020, 63, 147–155.

- Hudson, K.; Morgan, R.E. Industry Exposure to Artificial Intelligence, Board Network Heterogeneity, and Firm Idiosyncratic Risk. Journal of Management Studies 2025.

- Soto-Acosta, P.; Popa, S.; Martínez-Conesa, I. Information technology, knowledge management and environmental dynamism as drivers of innovation ambidexterity: a study in SMEs. Journal of Knowledge Management 2018, 22, 824–849.

- Bernal, P.; Maicas, J.; Vargas, P. Exploration, exploitation and innovation performance: disentangling the evolution of industry. Industry and Innovation 2019, 26, 295–320.

- Waseel, A.H.; Zhang, J.H.; Shehzad, M.U.; et al. Navigating the innovation frontier: ambidextrous strategies, knowledge creation, and organizational agility in the pursuit of competitive excellence. Business Process Management Journal 2024, 30, 2127–2160.

- Oluwafemi, T.B.; Mitchelmore, S.; Nikolopoulos, K. Leading innovation: Empirical evidence for ambidextrous leadership from UK high-tech SMEs. Journal of Business Research 2020, 119, 195-208.

- Tan, M.; Xia, Q. Curious, unconventional and creative: CEO openness and innovation ambidexterity. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2024, 36, 1054–1066.

- Hanifah, H.; Halim, H.; Ahmad, N.; et al. Emanating the key factors of innovation performance: leveraging on the innovation culture among SMEs in Malaysia. Journal of Asia Business Studies 2019, 13, 559-587.

- Khan, B.Z. Related Investing: Family Networks, Gender, and Shareholding in Antebellum New England Corporations. Business History Review 2022, 96, 487–524.

- Mueller, V.; Rosenbusch, N.; Bausch, A. Success Patterns of Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation. Journal of Management 2013, 39, 1606–1636.

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X. Too Much of a Good Thing: The Dual Effect of R&D Subsidy on Firms’ Exploratory Innovation. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 2023, 70, 1639–1651.

- Gao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Can public R&D subsidy facilitate firms’ exploratory innovation? The heterogeneous effects between central and local subsidy programs. Research Policy 2021, 50, 104221.

- Kim, K.; Seo, E.H.; Kim, C.Y. The Relationships Between Environmental Dynamism, Absorptive Capacity, Organizational Ambidexterity, and Innovation Performance from the Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 449.

- Auh, S.; Menguc, B. Balancing exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of competitive intensity. Journal of Business Research 2005, 58, 1652–1661.

- Bachmann, J.T.; Ohlies, I.; Flatten, T. Effects of entrepreneurial marketing on new ventures’ exploitative and exploratory innovation: The moderating role of competitive intensity and firm size. Industrial Marketing Management 2021, 92, 87–100.

- Li, L.; Wang, Z. Does Investment in Digital Technologies Foster Exploitative and Exploratory Innovation? The Moderating Role of Strategic Flexibility. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 2024, 71, 9402–9413.

- Mariani, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Generative artificial intelligence in innovation management: A preview of future research developments. Journal of Business Research 2024, 175, 114542.

- Gehman, J.; Glaser, V.L.; Merritt, P. An Assemblage Perspective on Hybrid Agency: A Commentary on Raisch and Fomina’s “Combining Human and Artificial Intelligence”. Academy of Management Review 2025, 50, 477–479.

- Grote, G.; Parker, S.K.; Crowston, K. Taming Artificial Intelligence: A Theory of Control-Accountability Alignment among AI Developers and Users. Academy of Management Review 2024, 00, 1-22.

- Gregory, R.W.; Henfridsson, O.; Kaganer, E.; et al. The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Data Network Effects for Creating User Value. Academy of Management Review 2021, 46, 534–551.

- Raisch, S.; Fomina, K. Combining Human and Artificial Intelligence: Hybrid Problem-Solving in Organizations. Academy of Management Review 2025, 50, 441–464.

- Chalmers, D.; MacKenzie, N.G.; Carter, S. Artificial Intelligence and Entrepreneurship: Implications for Venture Creation in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 2021, 45, 1028–1053.

- Krakowski, S.; Luger, J.; Raisch, S. Artificial intelligence and the changing sources of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal 2023, 44, 1425–1452.

- Wang, L.; Zhao, C.; Wei, W.; et al. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Enterprise Industrial Internet Standardization on Digital Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7347.

- Te’eni, D.; Yahav, I.; Zagalsky, A.; et al. Reciprocal Human-Machine Learning: A Theory and an Instantiation for the Case of Message Classification. Management Science 2023.

- Kakatkar, C.; Bilgram, V.; Füller, J. Innovation analytics: Leveraging artificial intelligence in the innovation process. Business Horizons 2020, 63, 171–181.

- Brem, A.; Giones, F.; Werle, M. The AI Digital Revolution in Innovation: A Conceptual Framework of Artificial Intelligence Technologies for the Management of Innovation. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 2023, 70, 770–776.

- Rammer, C.; Fernández, G.P.; Czarnitzki, D. Artificial intelligence and industrial innovation: Evidence from German firm-level data. Research Policy 2022, 51, 104555.

- Sun, Z.; Wu, X.; Dong, Y.; et al. How Does Artificial Intelligence Application Enable Sustainable Breakthrough Innovation? Evidence from Chinese Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7787.

- Liu, J.; Chang, H.; Forrest, J.Y.L.; et al. Influence of artificial intelligence on technological innovation: Evidence from the panel data of China’s manufacturing sectors. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2020, 158, 120142.

- Boussioux, L.; Lane, J.N.; Zhang, M.; et al. The Crowdless Future? Generative AI and Creative Problem-Solving. Organization Science 2024, 35, 1589–1607.

- Yu, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wu, P. How data shape actor relations in artificial intelligence innovation systems: an empirical observation from China. Industrial and Corporate Change 2021, 30, 251–267.

- Moser, C.; den Hond, F.; Lindebaum, D. Morality in the Age of Artificially Intelligent Algorithms. Academy of Management Learning & Education 2022, 21, 139–155.

- Hillebrand, L.; Raisch, S.; Schad, J. Managing with Artificial Intelligence: An Integrative Framework. Academy of Management Annals 2025, 19, 343–375.

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J. Organizational Ambidexterity: Antecedents, Outcomes, and Moderators. Journal of Management 2008, 34, 375–409.

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 1996, 17(S2), 109–122.

- Yu, S.; Chai, Y.; Samtani, S.; et al. Motion Sensor–Based Fall Prevention for Senior Care: A Hidden Markov Model with Generative Adversarial Network Approach. Information Systems Research 2024, 35, 1–15.

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; et al. Digital Innovation Management: Reinventing Innovation Management Research in a Digital World. MIS Quarterly 2017, 41, 223–238.

- Yao, J.Q.; Zang, K.P.; Guo, L.P.; Feng, X. How does Artificial Intelligence Improve Enterprise Productivity?—Based on the Perspective of Labor Skill Restructuring. Manag. World 2024, 40, 101–116.

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, J. How do family firms respond strategically to the digital transformation trend: Disclosing symbolic cues or making substantive changes? Journal of Business Research 2023, 155, 113395.

- Mikolov, T.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, K.; et al. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 2; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3111–3119.

- Altonji, J.G.; Elder, T.E.; Taber, C.R. Selection on Observed and Unobserved Variables: Assessing the Effectiveness of Catholic Schools. Journal of Political Economy 2005, 113, 151–184.

- Loonam, J.; Eaves, S.; Kumar, V.; et al. Towards digital transformation: Lessons learned from traditional organizations. Strategic Change 2018, 27, 101–109.

- Chen, J.; Roth, J. Logs with Zeros? Some Problems and Solutions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2023, 139, 891–936.

- Chen, C.J.; Huang, Y.F. Creative workforce density, organizational slack, and innovation performance. Journal of Business Research 2010, 63, 411–417.

- Nohria, N.; Gulati, R. Is Slack Good or Bad for Innovation? Academy of Management Journal 1996, 39, 1245–1264.

| Seed Word | Extended Word |

| Data strategy | cloud, data infrastructure, data connection |

| Data governance | data management, data hub, data middleware, data middle platform, business intelligence, informatization, computility, algorithm |

| Data framework | parallel processing, data model, data sharing, data interflow, service-oriented architecture, database, AutoML, sampling, PyTorch, TensorFlow, visualization, open edge computing, metadata, product data management, distributed computation, data modeling |

| Data standard | data warehouse, data exchange, data fabric, data retrieval, data coding, security orchestration, automation and response, data closed loop, network video recorder, enterprise resource planning, DevOps, data model, decision support system |

| Data quality | internet safety, password, information safety, data validation, sensitive data, data provenance, data lineage, data monitoring, data reconciliation, data collection |

| Data safety | information security, local area network, private data, data protection |

| Data application | data analysis, data mining, intellectual algorithm, data business, software development, data silo, data modeling, data service, data sensing |

| Data life cycle | data maintenance, intelligent fault diagnose, data retire, data destruction |

| Variable Name | Variable Expression | Obs | Mean | Std | Min | Max |

| Firms’ exploitative innovation performance | Exploit | 21,253 | 2.818 | 1.977 | 0.000 | 9.774 |

| Firms’ exploratory innovation performance | Explore | 21,253 | 1.509 | 1.170 | 0.000 | 7.172 |

| Firms’ AI application | AI | 21,253 | 0.782 | 1.032 | 0.000 | 5.620 |

| Firms’ size | Size | 21,253 | 22.633 | 1.362 | 17.641 | 28.697 |

| Firms’ age | Age | 21,253 | 3.087 | 0.263 | 1.792 | 4.290 |

| Return on firms’ total assets | Roa | 21,253 | 0.023 | 0.089 | -2.646 | 0.786 |

| Firms’ liability | Leverage | 21,253 | 0.464 | 0.207 | 0.008 | 1.957 |

| R&D investment intensity | R&D | 21,253 | 15.426 | 6.697 | 0.000 | 24.630 |

| Firms’ board scale | Board | 21,253 | 2.123 | 0.201 | 0.000 | 2.890 |

| Firms’ governance structure | Independent | 21,253 | 0.378 | 0.058 | 0.000 | 0.800 |

| Firms’ share concentrationTOP5 | Top5 | 21,253 | 0.146 | 0.112 | 0.001 | 0.810 |

| Variables | Exploit | Explore | AI | Size | Age | Leverage | Roa | R&D | Board | Independent | Top5 |

| Exploit | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Explore | 0.663*** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| AI | 0.281*** | 0.162*** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Size | 0.312*** | 0.390*** | 0.041*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| Age | -0.100*** | -0.085*** | 0.004 | 0.075** | 1.000 | ||||||

| Leverage | 0.076*** | 0.071*** | -0.022** | 0.407*** | 0.103*** | 1.000 | |||||

| Roa | 0.080*** | 0.104*** | -0.007 | 0.127*** | -0.025*** | -0.321*** | 1.000 | ||||

| R&D | 0.415*** | 0.609*** | 0.217*** | 0.123*** | -0.120*** | -0.089*** | 0.070*** | 1.000 | |||

| Board | 0.100*** | 0.086*** | -0.067*** | -0.030*** | 0.010 | -0.026*** | 0.009 | -0.537*** | 1.000 | ||

| Independent | -0.018** | 0.014* | 0.043*** | 0.311*** | -0.065*** | 0.058*** | 0.135*** | -0.051*** | 0.074*** | 1.000 | |

| TOP5 | 0.068*** | 0.039*** | -0.080*** | 0.311*** | -0.065*** | 0.058*** | 0.135*** | -0.051*** | 0.074*** | 0.038*** | 1.000 |

| VIF | — | — | 1.064 | 1.602 | 1.04 | 1.482 | 1.233 | 1.117 | 1.561 | 1.458 | 1.154 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | Exploit | Explore | Exploit | Explore | Exploit | Explore |

| AI | 0.121*** (0.015) |

0.063*** (0.014) |

0.073*** (0.015) |

0.034** (0.014) |

-0.103* (0.060) |

0.152*** (0.054) |

| Data | -0.065** (0.029) |

0.014 (0.030) |

||||

| AI×Data | 0.054*** (0.018) |

-0.035** (0.016) |

||||

| Size | 0.420*** (0.032) |

0.258*** (0.025) |

0.408*** (0.032) |

0.258*** (0.025) |

||

| Age | -0.073 (0.327) |

-0.821*** (0.268) |

-0.023 (0.327) |

-0.818*** (0.268) |

||

| Roa | -0.159 (0.099) |

-0.204** (0.084) |

-0.167* (0.099) |

-0.202* (0.084) |

||

| Leverage | 0.008 (0.107) |

0.165 (0.104) |

0.015 (0.106) |

0.158 (0.104) |

||

| R&D | 0.041*** (0.003) |

0.037*** (0.003) |

0.042*** (0.003) |

0.037*** (0.003) |

||

| Board | 0.1910* (0.103) |

0.052 (0.085) |

0.1862* (0.103) |

0.054 (0.085) |

||

| Independent | 0.220 (0.291) |

-0.478* (0.238) |

0.214 (0.291) |

-0.476* (0.238) |

||

| Top5 | 0.317 (0.285) |

0.573* (0.230) |

0.343 (0.285) |

0.558* (0.230) |

||

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 21,253 | 21,253 | 21,253 | 21,253 | 21,253 | 21,253 |

| Adj.R square | 0.825 | 0.435 | 0.837 | 0.475 | 0.838 | 0.475 |

| Exploit | Explore | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Groups of Controls | Coefficient of Limited Controls | Coefficient of All Controls | Ratio Difference | Coefficient of Limited Controls | Coefficient of All Controls | Ratio Difference |

| No Controls | 0.538 | 0.073 | 0.160 | 0.184 | 0.034 | 0.227 |

| Only Control Firm- and Year-Fixed Effects | 0.121 | 0.073 | 1.521 | 0.063 | 0.034 | 1.172 |

| Only Control Firm-Specific Variables | 0.097 | 0.073 | 3.041 | 0.058 | 0.034 | 1.417 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | Exploit | Explore | AI | Exploit | Explore |

| AI | 0.073*** (0.015) |

0.031** (0.013) |

|||

| IV | 0.042*** (0.011) |

||||

| AI_IV | 1.627*** (0.526) |

0.672* (0.265) |

|||

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 20,794 | 20,794 | 19,371 | 19,371 | 19,371 |

| Adj.R square | 0.832 | 0.461 | 0.346 | 0.244 | 0.172 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Variables | Exploit | Explore | Exploit | Explore | Exploit | Explore | Exploit | Explore |

| AI | 0.077*** (0.016) |

0.030* (0.015) |

0.067*** (0.014) |

0.043*** (0.013) |

0.088*** (0.024) |

0.044** (0.021) |

||

| Invest | 0.006** (0.003) |

0.006** (0.002) |

||||||

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year-Industry FE | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| Observation | 17.584 | 17.584 | 21,253 | 21,253 | 21,253 | 21,253 | 10,397 | 10,397 |

| Adj.R square | 0.847 | 0.480 | 0.084 | 0.047 | 0.850 | 0.487 | 0.847 | 0.494 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | Efficiency | Exploit | Explore | Graduate | Exploit | Explore |

| AI | 0.004*** (0.001) |

0.042*** (0.010) |

0.004** (0.002) |

0.468*** (0.138) |

0.071*** (0.015) |

0.289** (0.013) |

| Efficiency | 12.066*** (0.214) |

10.131*** (0.175) |

||||

| Graduate | 0.004*** (0.001) |

0.004*** (0.001) |

||||

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 17.584 | 17.584 | 21,253 | 21,253 | 21,253 | 21,253 |

| Adj.R square | 0.798 | 0.901 | 0.621 | 0.841 | 0.837 | 0.475 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | High Slack Resource | Low Slack Resource | ||

| Exploit | Explore | Exploit | Explore | |

| AI | 0.064*** (0.022) |

0.037* (0.020) |

0.056*** (0.020) |

0.023 (0.019) |

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 11,011 | 11,011 | 11,011 | 11,011 |

| Adj.R square | 0.849 | 0.474 | 0.826 | 0.484 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | High AI foundation | Low AI foundation | ||

| Exploit | Explore | Exploit | Explore | |

| AI | -0.002 (0.041) |

-0.020 (0.036) |

0.075*** (0.016) |

0.0360** (0.014) |

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 2,319 | 2,319 | 19.702 | 19.702 |

| Adj.R square | 0.850 | 0.469 | 0.820 | 0.470 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | High competition intensity | Low competition intensity | ||

| Exploit | Explore | Exploit | Explore | |

| AI | 0.060*** (0.019) |

-0.002 (0.018) |

0.074*** (0.021) |

0.050** (0.020) |

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 11,045 | 11,045 | 10.976 | 10.976 |

| Adj.R square | 0.835 | 0.451 | 0.834 | 0.503 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).