1. Introduction

As the population ages, the health problems associated with aging also increase. From a biological perspective, aging is linked to the accumulation of various molecular and cellular damages, resulting in a gradual decline in physical and mental abilities, an increased risk of disease, and ultimately death. The metabolic processes contributing to this progressive damage are called senescence [

1]. Certain pathological conditions, including hypoxia, acidosis, and metabolic disturbances, can trigger senescence, contributing to the onset of various chronic diseases [

2,

3]. Additionally, senescence can be induced by specific environmental factors, such as exposure to compounds that excessively produce free radicals and activate stress-responsive intracellular pathways [

4]. Therefore, developing strategies that target senescence could be beneficial for enhancing healthy aging and aiding in managing age-related disorders.

Polyphenolic flavonoids, which are widely distributed in plants, are recognized for their significant biological activities, including protection against oxidative stress, inflammation, and atherosclerosis in various model organisms [

5]. Among flavonoids, quercetin (3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone) (Q), abundant in vegetables and fruits, is often regarded as the most important in dietary and medicinal contexts. Its intake has been linked to positive health effects due to its antioxidant and free-radical scavenging properties [

6].

Studies on the nematode

Caenorhabditis (C.) elegans demonstrated that Q can positively affect longevity by extending the worms' lifespan and health span [

7,

8] and increasing their resistance to thermal and oxidative stress [

9]. These effects may be partially attributed to the flavonoid's ability to modulate the insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling (IIS) pathway, reduce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and upregulate genes involved in aging and ROS metabolism [

7,

9]. Given the high degree of homology between the IIS pathway in

C. elegans and humans, including genes encoding transcription factors related to aging and senescence [

10,

11], the data obtained from this preclinical model are highly informative. Due to its characteristics- such as simplicity, transparency, ease of cultivation, and short lifespan- this nematode serves as a unique tool for quickly obtaining relevant information on the physiological and pathological mechanisms underlying aging and changes in stress resistance, enabling long-term and costly studies in vertebrates to be conducted more efficiently [

11]. Furthermore, its conserved, metabolically active digestive system provides a rapid and ethically sound approach for evaluating various diet-derived compounds' biological and molecular protective effects [

12].

Recently, Q has been proposed as a natural senolytic compound capable of reducing the number of senescent cells

in vitro and

in vivo in mice [

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, its senolytic potential is less potent than other senolytic agents [

15]. This might be attributed to specific characteristics of Q, such as its low stability, which varies with temperature, pH, the presence of metal ions, and glutathione. Additionally, its poor water solubility complicates its oral bioavailability and may restrict the benefits of this flavonoid, limiting its practical use.

Several attempts have been made to improve Q bioavailability, including liposomes, nanoparticles, nanoemulsions, and micelles [

17,

18]. Among the various delivery systems, a lecithin-based formulation known as Quercefit™ Phytosome™ (QF) was developed [

19]. This formulation significantly enhances the phytonutrient's stability and solubility and provides advantages regarding bioabsorption. When administered to healthy volunteers, QF enables the absorption of Q up to 20 times greater than that of the unformulated version, without any noticeable side effects [

19].

For the first time, our study explored the potential anti-aging effect of QF

in vivo, using the nematode

C. elegans. Experiments were conducted under both physiological and stress-induced conditions to determine whether QF can slow the natural aging process of the organism and help protect it from the harmful effects of stressors. We also assessed the ability of QF to reduce the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which are considered markers of senescence [

20,

21,

22], and to modify the expression of gene components of the IIS pathway. We analysed the effect of QF on the ortholog of the human forkhead box O4 (FOXO4) transcription factor, DAF-16, which is a key mediator of longevity because its activation can result in lifespan extension [

8]. Its target genes contribute to mediating oxidative stress and heat shock stress response, including superoxide dismutase-3 (SOD-3), catalase-1 (CTL-1), and small heat shock protein (HSP)-16.2 and HSP-70 [

7,

9]. In addition, transcription factors relevant for regulating stress-responsive genes involved in longevity and immunosenescence, called SKN-1, an ortholog of the mammalian Nrf/CNC proteins, and HSF-1, an ortholog of the human heat shock transcription factor 1, were considered [

23]. The regulation of target genes of SKN-1, acting as detoxification enzymes by encoding ROS scavengers, was also considered to investigate whether the effect of QF can be ascribed to the modulation of different actors in the ISS pathway.

The findings support the notion that under stressed conditions, QF can promote the stress resistance and longevity of C. elegans by modulating the expression levels of genes and heat-shock elements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Methanol, acetonitrile (ACN), formic acid, phosphoric acid, and polysorbate-80 (cod. P1754) were from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (Milan, Italy). Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC, cod. 14094) was from Farmalabor (Assago, Milan, Italy). Potassium dihydrogen phosphate, sodium phosphate dibasic, sodium chloride, and magnesium sulphate were from Merck (Rahway, NJ, USA). A Milli-Q system produced HPLC-grade water in-house (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Quercetin (Q) and its lecithin formulation Quercefit™ Phytosome™ (QF) were provided by Indena S.p.A (Milan, Italy). QF consists of Q and sunflower lecithin in a 1:1 weight ratio, along with about a fifth part of food-grade excipients that are added to improve the physical state of the product (Patent Application no. WO2019/016146). QF standardization is ≥34.0% ≤42.0% of Q by HPLC.

2.2. C. elegans Maintenance and Treatment

The N2 Bristol C. elegans (Caenorhabditis Genetics Centre (CGC), University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were cultured at 20˚C on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates spread with live or inactivated OP50 Escherichia coli (CGC) as food. Worms were synchronized by egg-laying and cultured at 20˚C on NGM plates spread with OP50 E. coli (CGC) as food in the presence or absence of 50-200 µM Q in QF or the same concentration of unformulated Q. Control worms were fed the same 1% CMC suspension volume containing 0.3% polysorbate-80 alone (Vehicle).

2.3. QF Stability

To establish the optimal experimental scheme to be used in senescence studies with the worms, a stability analysis of Quercefit

TM (QF) was carried out under the same experimental conditions. Thus, QF was dissolved in 1% CMC containing 0.3% polysorbate-80 to obtain a solution with 2 mM of Q. The solution was diluted to 500 μM Q (150 μg/mL) in OP50 E. coli and spotted on NGM agar plates (250 μL/plate). After drying, the plates were incubated at 20°C for various time points ranging from one hour (i.e., the time required to dry the E. coli on the agar) to 2, 4, 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours. The plates were then washed with 1 mL M9 buffer (0.3% potassium dihydrogen phosphate, 0.6% sodium phosphate dibasic, 0.5% sodium chloride, and 1 M magnesium sulfate), and the wash was collected for Q measurement. For comparison, 250 μL of QF solution containing 500 μM Q in OP50 E. coli was also incubated in test tubes at 20°C for the same time points (1, 2, 4, 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours), and then dispensed into tubes containing 750 μL of M9 to achieve a final volume of 1 mL. Each sample was prepared in triplicate. At the end of the incubations, all solutions were sonicated for 15 minutes at high intensity using a Bioruptor® (Diagenode, SA, Seraing, Ougrée, Belgium) and then centrifuged at 1200 x g for 10 minutes to remove cellular debris. The supernatants were collected and analyzed to quantify Q content by HPLC with UV detection, as previously described [

19]. Q was used for the calibration curve. To this end, Q dissolved in methanol at 1 mg/mL was serially diluted with appropriate volumes of methanol to create eight working solutions at 1.0-200 μg/mL. Stock and working solutions of Q were stored at 4°C. Chromatographic separation was performed on an X Bridge BEH C18 (150 x 4.6mm, 2.5 μm) (Waters SpA, Sesto San Giovanni, Italy), equipped with an X Bridge BEH safeguard column (3.9 x 5mm, 2.5μm, Waters) maintained at 35°C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.3% phosphoric acid in water and 100% ACN with a constant flow of 0.7 mL/min. Elution began with 75% mobile phase A (0.3% phosphoric acid in water) and 25% mobile phase B (100% ACN), followed by an 8-minute linear gradient to 40% of A, a 1-minute linear gradient to 10% of A, and a 1-minute linear gradient back to 75% of A, which was maintained for 5 minutes to equilibrate the column. The total run time was 15 minutes. The injection volume was 15 μL, and the wavelength was set at 300 nm for quantitative analysis. The retention time for Q was 6.8 minutes. The peak area was plotted against the corresponding Q concentration, and the linearity of a representative concentration-response fitting was obtained using a weighted 1/x² linear function. A new calibration curve sample was prepared for each experimental session, consistently yielding an R² > 0.99 and reproducible results. No UV signals were observed when injecting blank solutions containing M9 ± OP50

E. coli alone.

2.4. Lifespan and Health Span

To evaluate the effect of the test compounds on the physiological decline of lifespan and health span, nematodes were synchronized by egg-laying and transferred to NGM plates seeded with

E. coli in the presence or absence of QF and unformulated Q (equimolar concentration) daily during the fertile period (5-6 days) to avoid overlapping generations. During this initial period, the test compounds were added to NGM plates daily. For the subsequent period (approximately 15 days), they were added every 48 hours, based on the results obtained from the stability studies. The effects on lifespan and health span under detrimental stress conditions were investigated in worms synchronized by egg-laying and transferred to NGM plates seeded with

E. coli, either in the presence or absence of QF or the same concentration of unformulated Q (equimolar concentration,100 µM Q) dissolved as described above. The worms were grown at 20°C for 72 hours. Control worms were fed the vehicle alone. Nematodes were incubated at 35°C for 3 hours and then placed on 20°C NGM plates seeded with fresh

E. coli, again in the presence or absence of the tested product. Worms were transferred daily as described. Dead, alive, and censored animals were recorded during transfers. Animals were counted as dead if they had neither moved nor reacted to a manual stimulus with a platinum wire, and had no pharyngeal pumping activity. Animals with exploded vulvas or those desiccated against the wall were censored. To determine the mean lifespan and survival curve, the counts of dead and censored animals were used for survival analysis, employing the Online Application for Survival Analysis (OASIS 2) [

24]. The Kaplan-Meier estimator was employed, and p-values were calculated using the log-rank test between different experimental groups. The number of active movements was also assessed in nematodes used for the lifespan assay to gauge healthy aging. Animals crawling spontaneously or in response to a manual stimulus were considered moving, while dead animals and those without crawling behavior were considered not moving. The statistical analysis was performed as described for lifespan [

25].

2.5. Stress Assays

Synchronized worms were cultured for 72 hours at 20˚C on NGM plates seeded with OP50

E. coli, either in the presence or absence of the test compound. Heat stress was induced by subjecting the animals to 35˚C for 1 to 5 hours, while control worms were maintained at 20˚C. The initiation of heat stress was designated as time 0 hours. Dead, alive, and censored animals were recorded at different time points. Animals were counted as dead if they had neither moved nor reacted to a manual stimulus with a platinum wire, and had no pharyngeal pumping activity. Animals with exploded vulvas or those desiccated against the wall were censored. The survival rate was calculated using the Online Application for Survival Analysis OASIS 2 [

24]. In addition, the number of active movements was also assessed. Animals crawling spontaneously or in response to a manual stimulus were considered moving, while dead animals and those without crawling behavior were considered not moving. The statistical analysis was performed as described for the survival analysis. Oxidative stress was induced by collecting worms and treating them for 2 hours at 20˚C with 0.5 mM hydrogen peroxide (100 worms/100 µL), and plating them on fresh NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli, either in the presence or absence of the test compound. The feeding behavior of worms was assessed 24 hours later by scoring the pharyngeal pumping rate, counting the number of times the terminal bulb of the pharynx contracted in one minute (pumps/min) [

26].

2.6. AGEs Formation

Synchronized worms were cultured at 20˚C on NGM plates seeded with OP50

E. coli, either with or without the test compound. The formation of AGEs was evaluated as described by Komura et al., 2021 [

27]. Briefly, 20 worms aged 3 to 11 days of adulthood were collected by picking, placed in M9 buffer, allowed to settle by gravity, and washed in M9 to remove bacteria. Worm pellets were suspended in 30 µL of 60 mM Tris solution, pH 6.8, containing 10% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 5% β-mercaptoethanol, boiled for 10 minutes at 95°C, and loaded into a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were separated at 100 V in SDS running buffer and transferred for 2 hours at 100 V onto a Polyvinylidene fluoride membrane in 20 mM Tris solution containing 150 mM glycine and 10% methanol. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in 10 mM Tris-HCl solution, pH 7.5, containing 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, 5% (w/v) low-fat dry milk powder, and 2% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, and incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse monoclonal anti-AGE antibody clone 6D12 (1:1000 dilution, DBA, Milan, Italy, catalogue number KAL-KH001) or a mouse monoclonal anti-actin antibody clone C4 (1:2000 dilution, Sigma-Aldrich, catalogue number MAB1501). Anti-mouse IgG peroxidase conjugate (1:10000, Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number A4416) was used as the secondary antibody. Chemioluminescence was detected using Clarity Max Western ECL Substrate (Biorad, Hercules, California, USA), and the membranes were scanned with a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Biorad). The mean volumes of the immunoreactive bands were determined with Image Lab™ software (Bio-Rad).

2.7. Gene Expression

Synchronized worms were cultured for 72 hours at 20˚C on NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli in the presence or absence of the test compound and subjected to heat stress by incubation at 35˚C for 3 hours. Control worms were maintained at 20˚C. Nematodes were then collected with M9 buffer, settled by gravity, and washed with M9 to eliminate bacteria. According to the manufacturer's instructions, RNA was extracted from the pellet of worms using the Maxwell® RSC simplyRNA Tissue kit (Promega Italia Srl, Milan, Italy). Briefly, the pellet of worms was homogenized by Turrax (T10, IKA-Werke GmbH & Co., Germany) for 2 minutes using 200 μL of a chilled working solution prepared by adding 20 μL of 1-thioglycerol per milliliter of homogenization solution. Lysis buffer (200 μL) was added to 200 μL of homogenate, vortexed for 15 seconds, and transferred into the cartridge well. RNA was extracted and eluted in 50 μL of nuclease-free water, and the concentration was quantified using NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Monza, Italy). mRNA was reverse transcribed using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). To this end, 1 µg of RNA was retrotranscripted using random primers in a 20 µL final mix volume. cDNA (50 ng) was used for Q-PCR amplification using the 2X Power SYBRTM Green PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystem, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and the Applied Biosystem QuantStudioTM 5 Real-Time PCR System. Specific primers were designed on the sequences of the genes of interest and used for the PCR amplification (

Table 1). The relative gene expression levels were determined using the 2-ΔΔCT method, using the cell division cycle-related (

cdc-42) or the conserved iron-binding-related (

y45f10d.4) as housekeeping genes.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

No randomization was required for

C. elegans experiments. All evaluations were done blind to the sample identity and treatment group. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10.2 software (CA, USA) by Student’s

t-test, one-way or two-way ANOVA, and Bonferroni’s post hoc test. A

p-value <0.05 was considered significant. For lifespan and health span studies, the number of dead and censored animals was used for survival analysis in OASIS 2 [

24]. The p-values were calculated using the log-rank and Bonferroni’s post hoc test between the pooled populations of animals.

3. Results

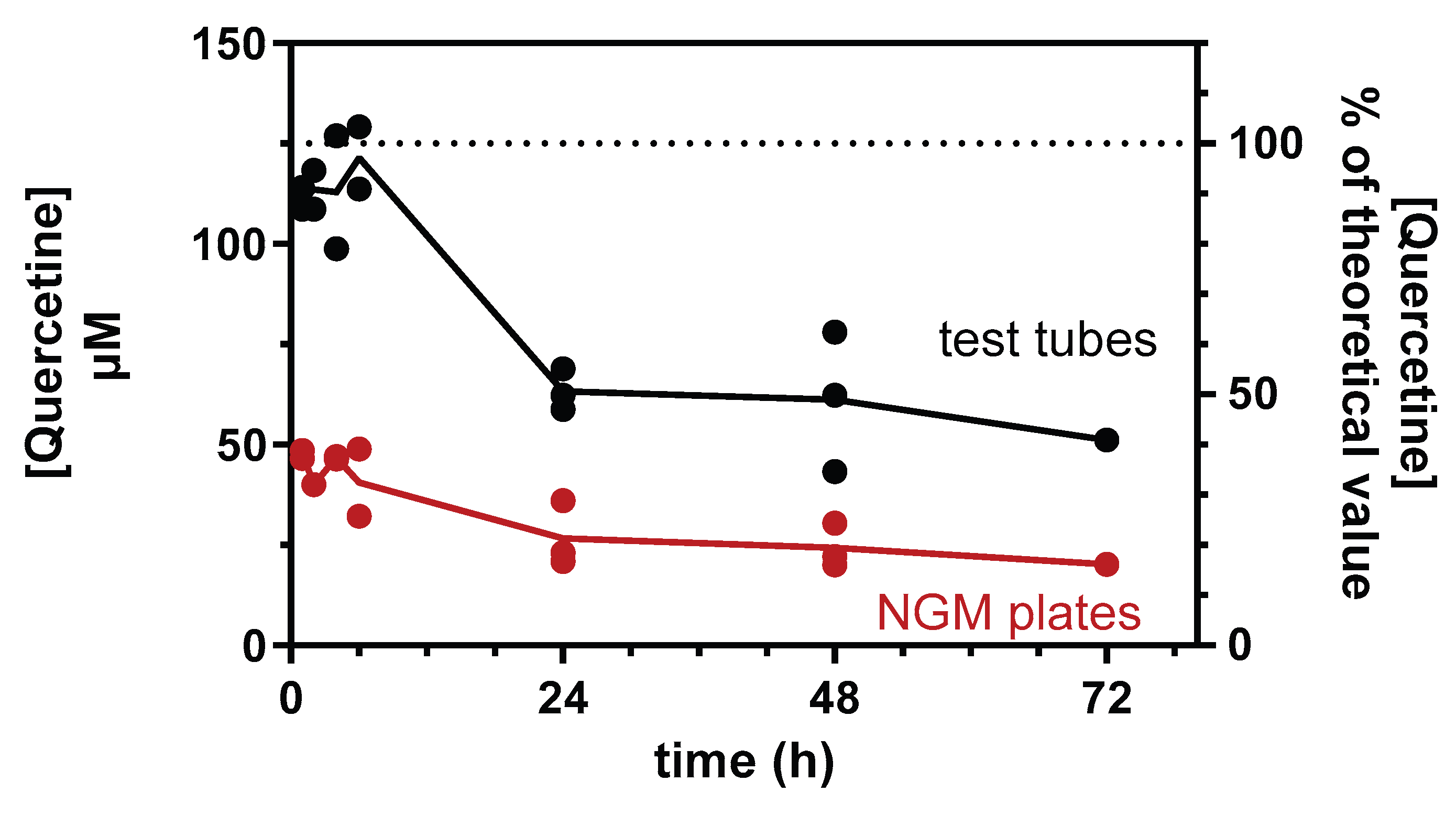

3.1. Optimization of Experimental Conditions for QF’s Efficacy Studies

Initial studies were conducted to establish the stability of Q in the experimental conditions required to assess the effects of QF in

C. elegans. To achieve this, QF was dissolved in 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate-80 to make a 2 mM Q solution, which was then diluted fourfold in OP50

E. coli and spotted onto NGM agar plates (250 μL/plate) or aliquoted for comparison in test tubes (250 μL/tube). After various incubation times, ranging from 1 to 72 hours, the plates were washed with 1 mL M9, while the samples in the tubes were diluted to 1 mL with M9.

Figure 1 shows that the concentration of Q measured in the tubes was stable for up to 6 hours, remaining close (90-97% on average) to the expected value (125 µM). The concentration dropped to approximately 50% after 24 hours, then remained almost stable up to 72 hours. In the samples recovered by washing the NGM plates, the concentration of Q was nearly constant in the first 6 hours; still, it represented only 38-33% of the amount initially applied to the plates, possibly due to bacteria-induced degradation and/or incomplete recovery from washing. We also observed that approximately 50% of Q formulated with lecithin in QF degraded from 6 to 24 hours (as seen in tubes), with no further degradation until 72 hours. Based on these results, and taking into account that practical reasons do not allow to avoid the partial degradation occurring in the first 24 hours, for the efficacy studies we planned to keep the worms on NGM plates containing QF or an equimolar concentration of Q for a maximum of 48 hours, after which they are transferred to new, fresh plates prepared in the same manner. Based on these results, to investigate the ability of QF to delay aging and senescence, the lecithin-based formulation was dissolved in 1% CMC containing 0.3% polysorbate-80 (Vehicle) to obtain a stock solution containing 2 mM Q, which was then diluted to 50-200 µM in live

E. coli OP50 before being seeded on NGM plates. Equimolar solutions of Q were prepared in the same manner for experiments to compare the effects of the two products. Synchronized worms were cultured on these plates and transferred every 48 hours to new plates with fresh

E. coli containing the test products, ensuring their continuous exposure to a stable concentration of either formulated or non-formulated phytonutrients. Control worms were cultured on NGM plates seeded with

E. coli OP50, which contained the same volume of vehicle alone.

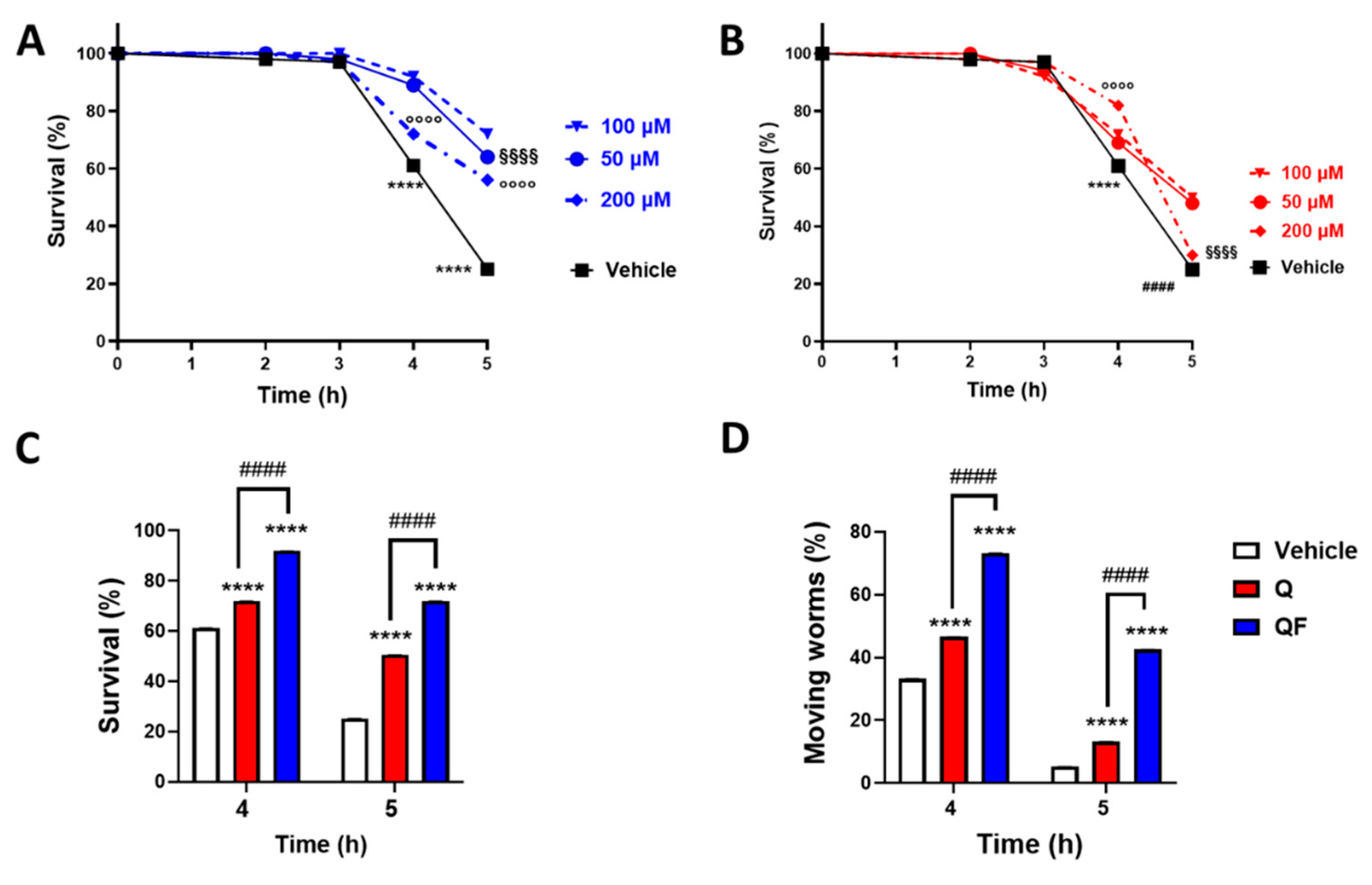

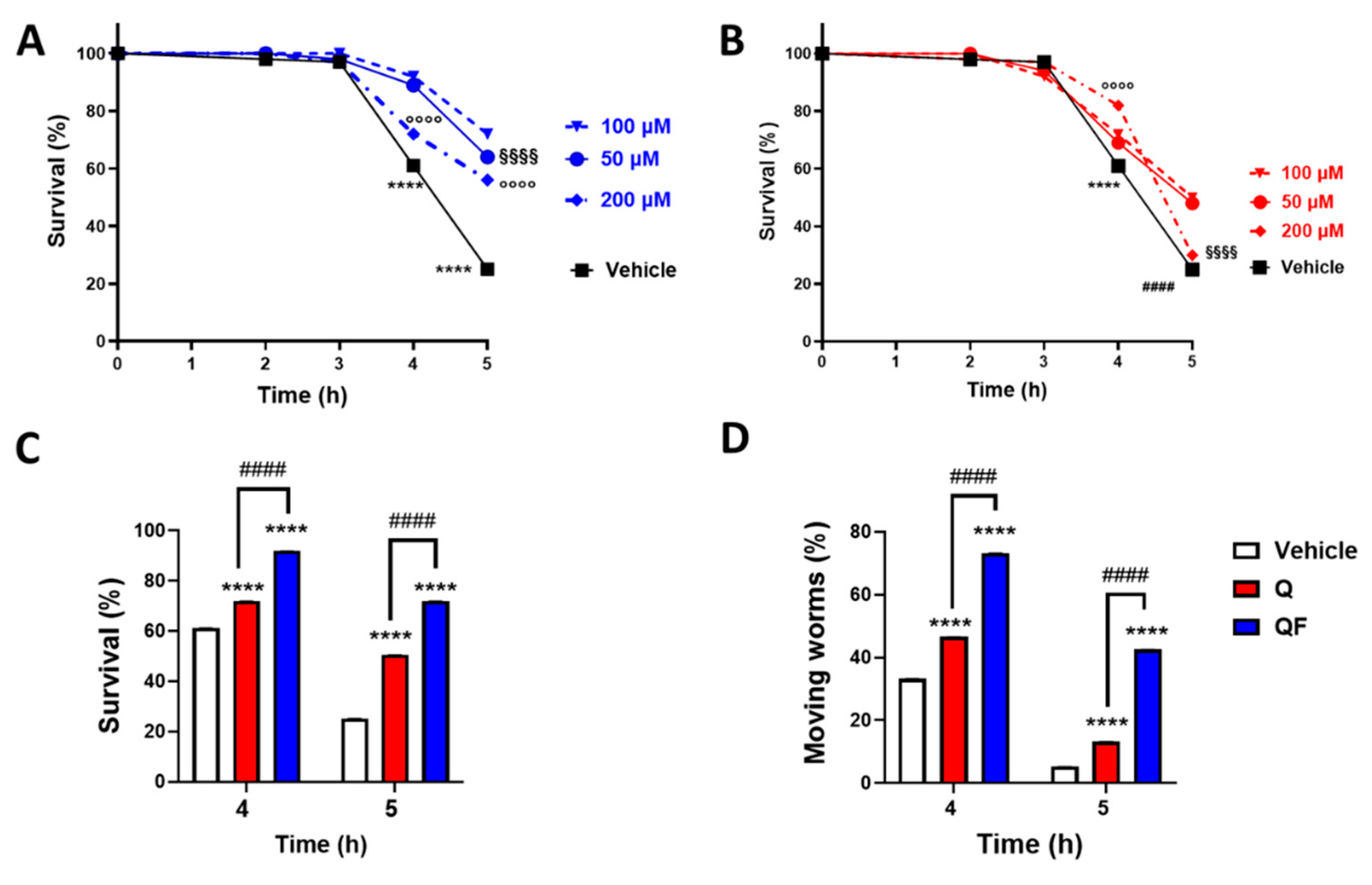

3.2. QF Enhances Worm Resistance to Thermal and Oxidative Stress

The effect of QF on resistance to thermal and oxidative stress was first evaluated. Specifically, nematodes grown in the presence of 50-200 µM QF or equimolar Q were subjected to thermal stress on the third day of adulthood, and their survival was assessed at various later times. The average proportion of living worms remained unchanged until three hours after the stress across all groups (

Figure 2A and 2B).

Exposure to thermal stress for four and five hours resulted in 61% and 25% survival in the control group, while worms treated with all doses of QF or Q exhibited a significantly higher survival percentage. Although a concentration-dependent protective effect was observed at 50 and 100 µM, the highest dose of 200 µM resulted in a lower effect. Five hours after the stress, only 56% of worms treated with 200 µM QF were still alive, compared to 64% and 72% of those treated with 50 and 100 µM, respectively (

Figure 2A). This can be attributed to a hormetic response of Q [

28], rather than specifically to toxicity linked to the lecithin formulation, since similar results were observed with unformulated Q (

Figure 2B). Based on these data, we selected 100 µM as the optimal dose of QF to use in all subsequent experiments. Interestingly, at this dose level, the lecithin delivery formulation was significantly more effective than the same dose of unformulated Q in protecting worms from death (

Figure 2C) and movement impairment (

Figure 2D) induced by thermal stress.

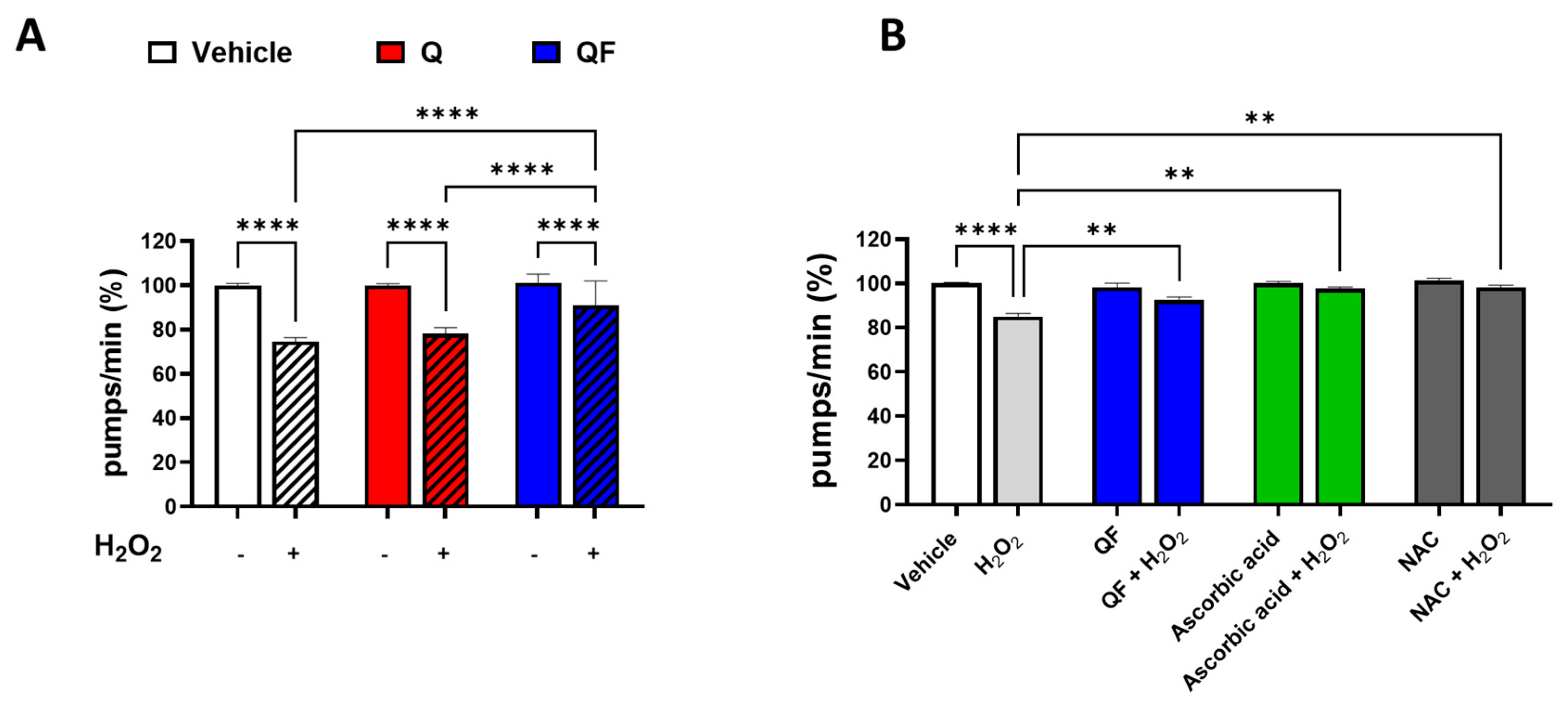

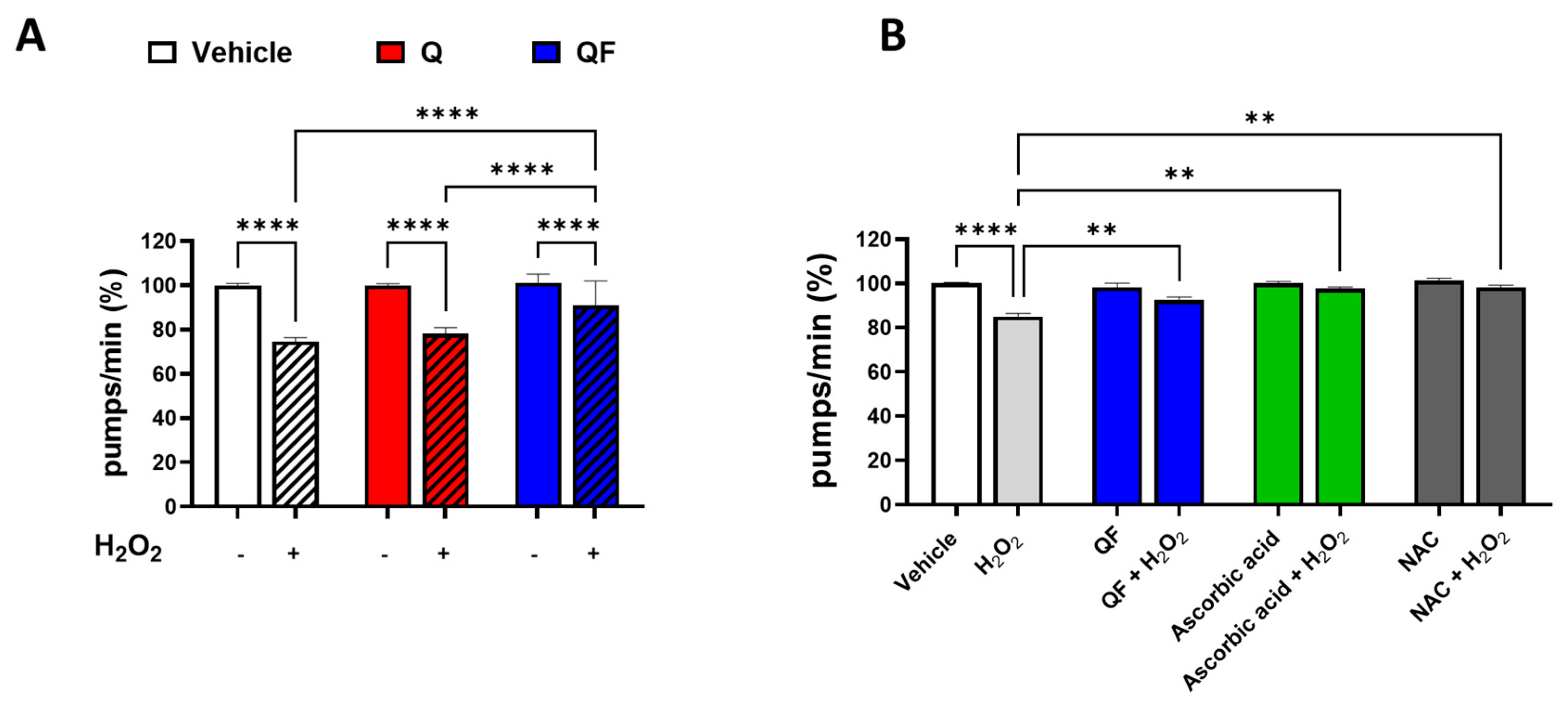

Muscle dysfunction, including a decrease in motility and feeding behavior, is considered a marker of aging and senescence and is known to worsen under stress conditions, such as exposure to heat and ROS [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Worms grown in the presence of QF were treated with hydrogen peroxide on the first day of adulthood, and the function of the pharyngeal muscles was assessed 24 hours later. At 100 µM, QF but not Q significantly protected worms from the pharyngeal dysfunction caused by 0.5 mM hydrogen peroxide (

Figure 3A). This effect is similar to when worms were administered prototypic antioxidants like 5 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and 284 µM ascorbic acid (

Figure 3B). QF and unformulated Q, as well as NAC and ascorbic acid, at the concentrations used, did not affect the feeding behavior of worms (

Figure 3A-B).

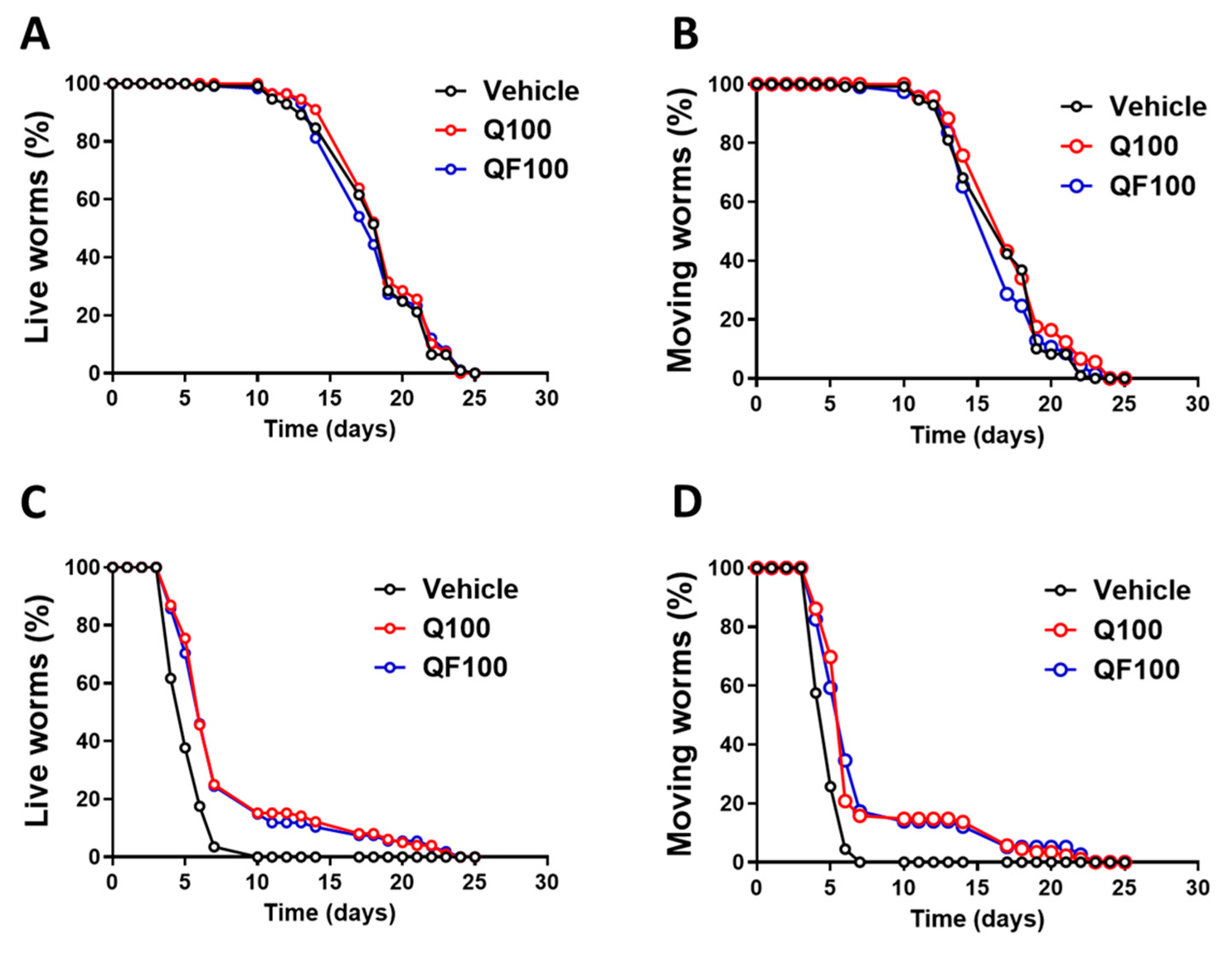

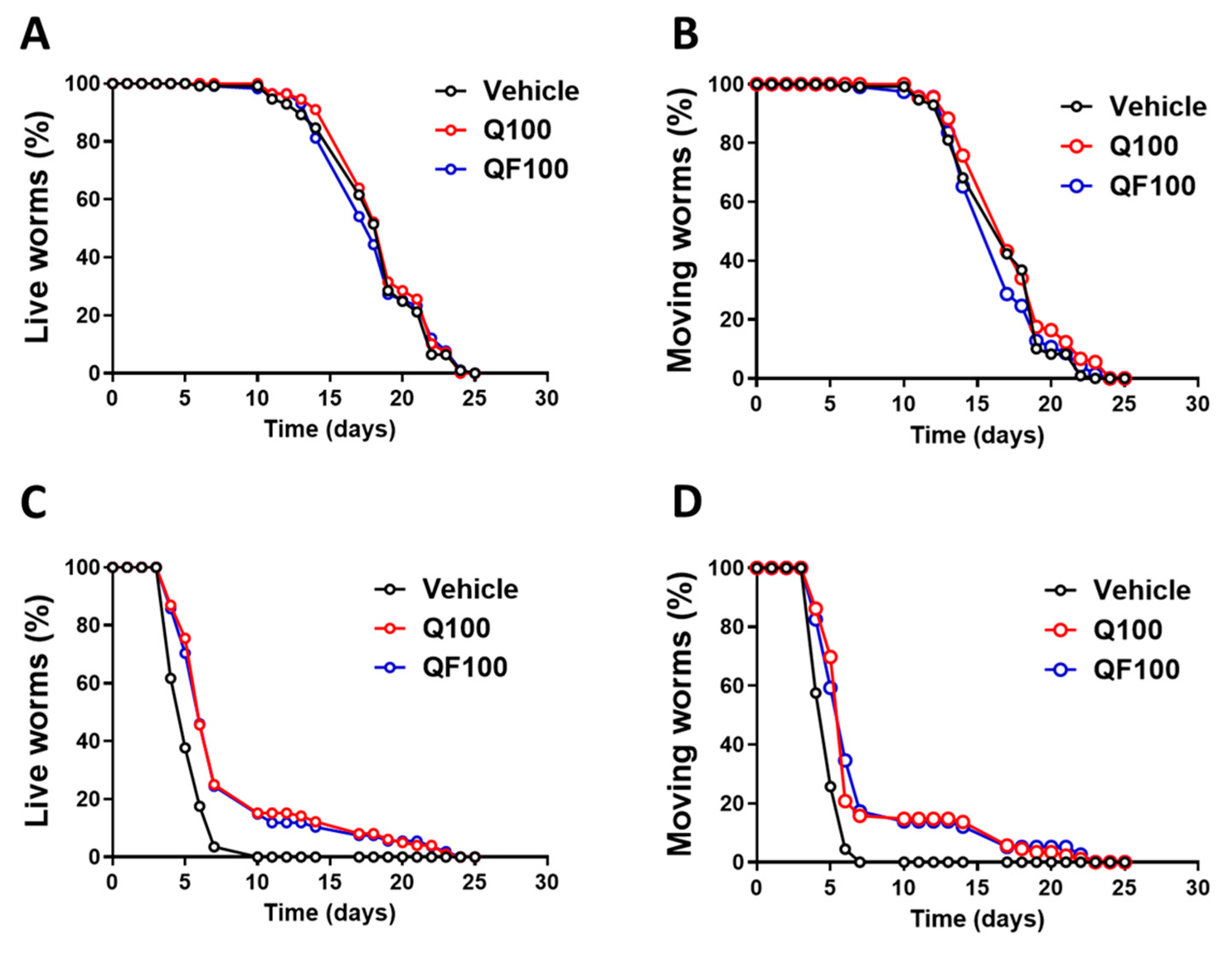

3.3. QF Enhances the Worm’s Lifespan and Health Span

In the presence or absence of 100 µM QF or unformulated Q, aging under physiological and stress-induced conditions was evaluated by assessing the lifespan and health span of the worms. No extension in lifespan or improvement in health span was observed under physiological conditions (

Figure 4A-B and

Table 2). However, under thermal stress conditions, 100 µM QF, similar to unformulated Q, increased worms' lifespan and health span by about 50%, demonstrating its capacity to counteract the decline in response to stress (Figures 4C-D and

Table 2). Since the decrease in worms’ motility is a functional parameter indicative of senescence, the ability of QF to improve the health span indicates the senolytic effect of this compound.

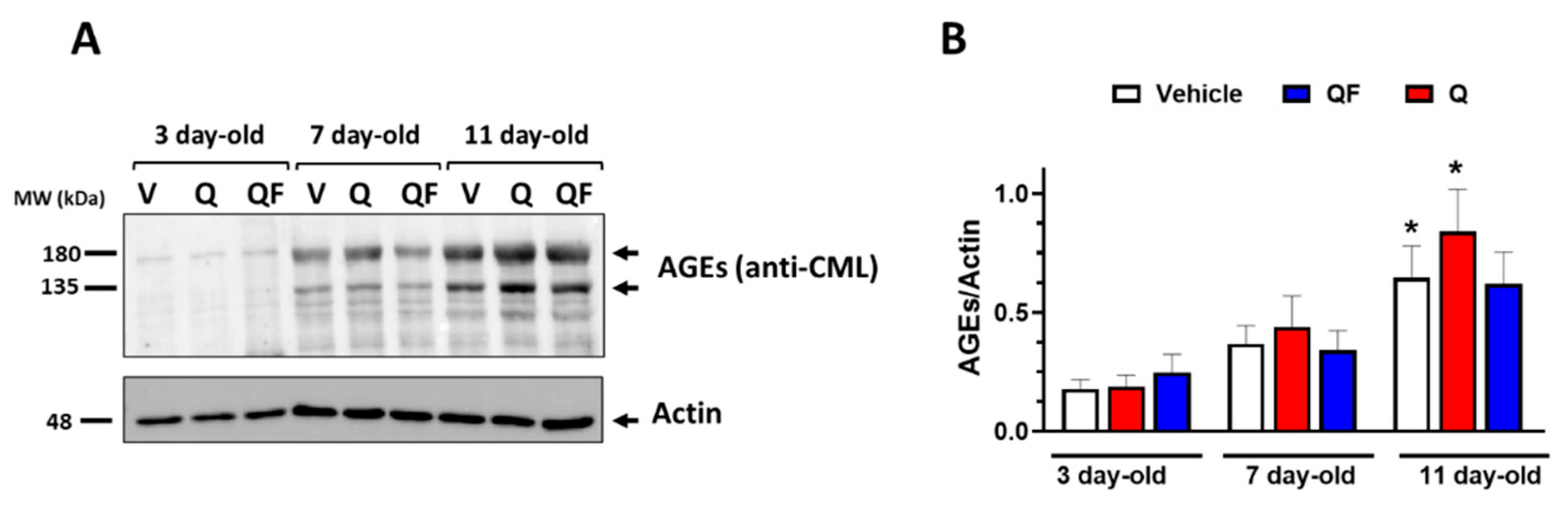

3.4. QF Does not Significantly Reduce AGEs Accumulation

The senolytic effect of QF was assessed by examining the accumulation of AGEs, which are considered senescence markers. As expected, we observed a significant increase in AGEs with the age of the worms starting on the 11

th day of adulthood, as shown by quantifying the immunoreactive signal from Western blot analysis using the anti-AGEs CML antibody (

Figure 5A and B). Neither QF nor Q significantly reduced AGEs accumulation. However, in 11-day-old worms grown with 100 µM Q, a significant accumulation of AGEs was observed, similar to the controls, while in the presence of QF, this was not the case (

Figure 5B). The lack of significance for QF could be due to high variability in the western blot data, caused by the poor specificity of the anti-AGE antibody, or it may be that a more significant effect appears later when the worms are more advanced in aging.

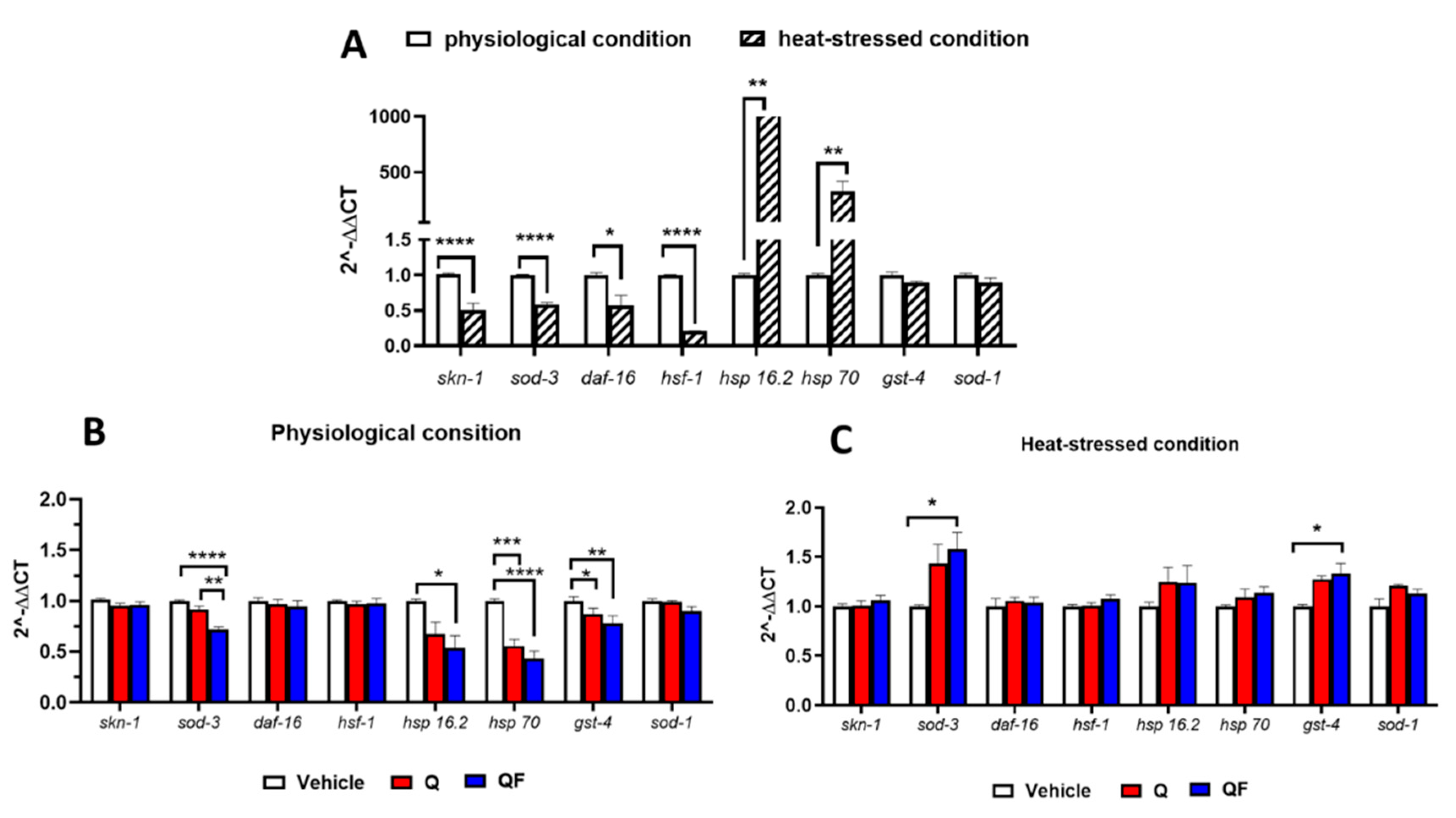

3.5. QF Under Stress Conditions Regulates Gene Expression and Heat-Shock Elements

To understand the mechanism of QF activities, we measured the expression of genes involved in the IIS and MAPK pathways using RT-qPCR in worms exposed to thermal stress or not. As expected, heat exposure significantly increased the expression of

hsp-16.2 and

hsp-70, while it decreased the levels of

skn-1,

daf-16,

hsf-1, and

sod-3 (

Figure 6A). As shown in

Figure 6B-C, QF, like Q, did not change the expression of

skn-1,

daf-16,

hsf-1, and

sod-1 in worms under normal or heat-stressed conditions.

In worms maintained under physiological conditions, QF significantly reduced the expression of the

sod-3, hsp-16.2, hsp-70, and

gst-4 genes compared to control nematodes. Although to a lesser extent, similar effects were observed in worms treated with an equimolar concentration of Q; however, for

hsp-16.2, the decrease did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 6B). As suggested for Q [

34], QF may also act as a ROS scavenger, thus repressing the transcription of heat-shock element genes activated by thermal stress, such as

hsp-16.2 and

hsp-70 (

Figure 6A), as well as genes involved in the antioxidant and detoxification response, like

sod-3 and

gst-4. Notably, in worms subjected to thermal stress, QF significantly promoted the expression of these last two genes and slightly increased, although not significantly, the expression of

hsp-16.2 (

Figure 6C). As reported in the literature, less pronounced effects that did not reach statistical significance were observed with Q (

Figure 6C) [

7]. These results indicate that, under stressed conditions, QF can modulate gene levels and heat-shock elements associated with longevity and stress resistance.

4. Discussion

Flavonoids are proposed to delay and palliate aging where senescence is involved. The dietary sources of natural phenolic compounds afford protection in the aging process and include, as some examples, naringenin, hesperidin, Q, kaempferol, luteolin, genistein, epigallocatechin gallate, and resveratrol. Many of these compounds possess anti-senescence effects. The benefits of Q in fighting aging, involving protection from the cellular damage of oxidative stress, are well documented. However, they may be limited in vivo by Q's low water solubility, poor stability, and oral bioavailability, requiring a high dose to achieve desired effects. To improve the water solubility of Q and enhance its biological absorption in vivo, a lecithin formulation technology has been used to develop QF. This study investigated, for the first time, whether the formulation improves the anti-aging effect of Q using C. elegans.

We observed that QF is more effective than Q in protecting worms from thermal and oxidative stress-induced toxicity, showing effects similar to common antioxidants such as ascorbic acid and NAC. QF also significantly extends the lifespan and health span of stressed worms, but not those of nematodes aged in physiological conditions. These results do not align with the available literature, which reports a slight but significant increase in the mean lifespan of approximately 10% when worms were grown in the presence of a comparable concentration of Q [

8,

9]. However, it should be noted that the published data were obtained using fluorodeoxyuridine to render worms sterile. This carcinogenic compound, whose use is debated among

C. elegans researchers, could act as a stressor; therefore, the results obtained under these experimental conditions would represent stress-induced aging rather than physiological aging.

Gene expression analyses also indicate that the effects of QF are linked to increased expression of

sod-3 and

gst-4, which are related to an increase in longevity and stress resistance, and a slight, although non-significant increase in

hsp-16.2 expression, also associated with longevity. These results align with data from other groups studying the effect of Q in wild-type and mutant worms[

7,

8,

33,

34,

35], but differ from findings by Sugawara and Sakamoto, who reported that Q feeding increased the transcription of all these genes [

9]. The reason for this difference is difficult to determine and likely relates to differences in methods and experimental approaches. Notably, although

skn-1 is a key gene for regulating detoxification enzymes and is reported to be involved in Q-induced resistance to thermal stress [

9], its expression level was unaffected by QF, especially in this model [

7,

33]. Additionally, QF did not alter the expression of

sod-1, a

skn-1 target gene encoding ROS scavengers, which was reported to be increased by Q only by Sugawara and Sakamoto [

9]. The protective effect of QF was not linked to changes in the level of the

daf-16 gene [

7,

8], but it cannot be excluded that, as suggested for Q, it could be associated with the nuclear translocation of the protein, thus activating the expression of stress-responsive genes [

34].

This is the first evidence that QF, acting at the transcriptional level, can provide stress protection that promotes aging and senescence. Since these transcription factors are conserved across species, including vertebrates, the data from C. elegans suggest that QF could also have protective effects on human health. Clinical studies are planned to explore and translate these promising lifespan benefits observed in our research to humans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., L.D., and M.M.B.; methodology, M.G., M.M., and M.M.B.; investigation, C.F., M.N., M.M., and M.M.B.; data curation, M.M., M.G., L.D., and M.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D., M.G.; writing—review and editing, L.D., M.G., M.M., A.R., and S.T.; supervision, L.D. and S.T.; funding acquisition, L.D., and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Indena SpA funded this research. The sponsor had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation. They contributed to the writing of the report and the choice of journal to submit the article to for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this article are available at Zenodo at the request of the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

C. elegans and OP50 E. coli were provided by the GCG, funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors, Antonella Riva and Serena Tongiani, are employees of Indena SpA.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Q |

Quercetin |

| QF |

Quercefit™ Phytosome™ |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| C. |

Caenorhabditis |

| IIS |

Insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling (IIS) pathway |

| AGEs |

Advanced glycation end products |

| FOXO4 |

Human forkhead box O4 |

| SOD-3 |

Superoxide dismutase-3 |

| CTL-1 |

Catalase-1 |

| HSP |

Small heat shock protein |

| ACN |

Acetonitrile |

| CMC |

Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose |

| CGC |

Caenorhabditis Genetics Centre |

| NGM |

Nematode growth medium |

| SDS |

Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| NAC |

N-acetylcysteine |

References

- Wissler Gerdes, E.O.; Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Discovery, Development, and Future Application of Senolytics: Theories and Predictions. FEBS J 2020, 287, 2418–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimpour, S.; Zakeri, M.; Esmaeili, A. Crosstalk between Obesity, Diabetes, and Alzheimer’s Disease: Introducing Quercetin as an Effective Triple Herbal Medicine. Ageing Res Rev 2020, 62, 101095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, D.; Gil, J. Senescence and Aging: Causes, Consequences, and Therapeutic Avenues. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viña, J.; Olaso-Gonzalez, G.; Arc-Chagnaud, C.; De la Rosa, A.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C. Modulating Oxidant Levels to Promote Healthy Aging. Antioxid Redox Signal 2020, 33, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, J.A.; Perez-Jimenez, J.; Neveu, V.; Medina-Remón, A.; M’hiri, N.; García-Lobato, P.; Manach, C.; Knox, C.; Eisner, R.; Wishart, D.S.; et al. Phenol-Explorer 3.0: A Major Update of the Phenol-Explorer Database to Incorporate Data on the Effects of Food Processing on Polyphenol Content. Database (Oxford) 2013, 2013, bat070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Sun, C.; Mao, L.; Ma, P.; Liu, F.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y. The Biological Activities, Chemical Stability, Metabolism and Delivery Systems of Quercetin: A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2016, 56, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuda-Durán, B.; González-Manzano, S.; Miranda-Vizuete, A.; Sánchez-Hernández, E.; R Romero, M.; Dueñas, M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; González-Paramás, A.M. Exploring Target Genes Involved in the Effect of Quercetin on the Response to Oxidative Stress in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019, 8, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, N.; Pietsch, K.; Menzel, R.; Steinberg, C.E.W. Quercetin-Mediated Longevity in Caenorhabditis Elegans: Is DAF-16 Involved? Mech Ageing Dev 2008, 129, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, T.; Sakamoto, K. Quercetin Enhances Motility in Aged and Heat-Stressed Caenorhabditis Elegans Nematodes by Modulating Both HSF-1 Activity, and Insulin-like and P38-MAPK Signalling. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0238528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Xiao, X.; Nian, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; Bao, W.; Li, C.; et al. Senolytics Enhance the Longevity of Caenorhabditis Elegans by Altering Betaine Metabolism. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2024, 79, glae221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, D.K.; Fuentealba, M.; Dönertaş, H.M.; Partridge, L.; Thornton, J.M. Functional Conservation in Genes and Pathways Linking Ageing and Immunity. Immun Ageing 2021, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunti, S.; Andersen, N.; Rayes, D.; De Rosa, M.J. Drug Discovery: Insights from the Invertebrate Caenorhabditis Elegans. Pharmacology Res & Perspec 2021, 9, e00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, M.S.; Habiel, D.M.; Coelho, A.L.; Verri, W.A.; Hogaboam, C.M. Quercetin Enhances Ligand-Induced Apoptosis in Senescent Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Fibroblasts and Reduces Lung Fibrosis In Vivo. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2019, 60, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Jiang, K.; Ogrodnik, M.; Chen, X.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Lohmeier, H.; Ahmed, L.; Tang, H.; Tchkonia, T.; Hickson, L.J.; et al. Increased Renal Cellular Senescence in Murine High-Fat Diet: Effect of the Senolytic Drug Quercetin. Transl Res 2019, 213, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özsoy Gökbilen, S.; Becer, E.; Vatansever, H.S. Senescence-Mediated Anticancer Effects of Quercetin. Nutr Res 2022, 104, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, B.A.; Mitchell, A.E.; Shin, A.C.; Dehghani, F.; Shen, C.-L. Dietary Flavonoid Actions on Senescence, Aging, and Applications for Health. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2025, 139, 109862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomou, E.-M.; Papakyriakopoulou, P.; Saitani, E.-M.; Valsami, G.; Pippa, N.; Skaltsa, H. Recent Advances in Nanoformulations for Quercetin Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Silva, M.; Faria-Silva, C.; Carvalheiro, M.C.; Simões, S.; Marinho, H.S.; Marcelino, P.; Campos, M.C.; Metselaar, J.M.; Fernandes, E.; Baptista, P.V.; et al. Quercetin Liposomal Nanoformulation for Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, A.; Ronchi, M.; Petrangolini, G.; Bosisio, S.; Allegrini, P. Improved Oral Absorption of Quercetin from Quercetin Phytosome®, a New Delivery System Based on Food Grade Lecithin. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2019, 44, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebeková, K.; Brouder Šebeková, K. Glycated Proteins in Nutrition: Friend or Foe? Exp Gerontol 2019, 117, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacco, F.; Brownlee, M. Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Complications. Circ Res 2010, 107, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, V.; Maczurek, A.; Phan, T.; Steele, M.; Westcott, B.; Juskiw, D.; Münch, G. Advanced Glycation Endproducts and Their Receptor RAGE in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Aging 2011, 32, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jo, Y.; Cho, D.; Ryu, D. L-Threonine Promotes Healthspan by Expediting Ferritin-Dependent Ferroptosis Inhibition in C. Elegans. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.K.; Lee, D.; Lee, H.; Kim, D.; Son, H.G.; Yang, J.-S.; Lee, S.-J.V.; Kim, S. OASIS 2: Online Application for Survival Analysis 2 with Features for the Analysis of Maximal Lifespan and Healthspan in Aging Research. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 56147–56152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Romeo, M.; Larigot, L.; Hemmers, A.; Tschage, L.; Kleinjohann, J.; Schiavi, A.; Steinwachs, S.; Esser, C.; Menzel, R.; et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-Dependent and -Independent Pathways Mediate Curcumin Anti-Aging Effects. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diomede, L.; Romeo, M.; Rognoni, P.; Beeg, M.; Foray, C.; Ghibaudi, E.; Palladini, G.; Cherny, R.A.; Verga, L.; Capello, G.L.; et al. Cardiac Light Chain Amyloidosis: The Role of Metal Ions in Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 27, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komura, T.; Yamanaka, M.; Nishimura, K.; Hara, K.; Nishikawa, Y. Autofluorescence as a Noninvasive Biomarker of Senescence and Advanced Glycation End Products in Caenorhabditis Elegans. NPJ Aging Mech Dis 2021, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas, M.; Surco-Laos, F.; González-Manzano, S.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Gómez-Orte, E.; Cabello, J.; Santos-Buelga, C. Deglycosylation Is a Key Step in Biotransformation and Lifespan Effects of Quercetin-3-O-Glucoside in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Pharmacol Res 2013, 76, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, P.; Braeckman, B.P.; Matthijssens, F. ROS in Aging Caenorhabditis Elegans: Damage or Signaling? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2012, 2012, 608478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.I.; Pincus, Z.; Slack, F.J. Longevity and Stress in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Aging (Albany NY) 2011, 3, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.; Snoek, L.B.; De Bono, M.; Kammenga, J.E. Worms under Stress: C. Elegans Stress Response and Its Relevance to Complex Human Disease and Aging. Trends Genet 2013, 29, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dues, D.J.; Andrews, E.K.; Schaar, C.E.; Bergsma, A.L.; Senchuk, M.M.; Van Raamsdonk, J.M. Aging Causes Decreased Resistance to Multiple Stresses and a Failure to Activate Specific Stress Response Pathways. Aging (Albany NY) 2016, 8, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietsch, K.; Saul, N.; Menzel, R.; Stürzenbaum, S.R.; Steinberg, C.E.W. Quercetin Mediated Lifespan Extension in Caenorhabditis Elegans Is Modulated by Age-1, Daf-2, Sek-1 and Unc-43. Biogerontology 2009, 10, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampkötter, A.; Timpel, C.; Zurawski, R.F.; Ruhl, S.; Chovolou, Y.; Proksch, P.; Wätjen, W. Increase of Stress Resistance and Lifespan of Caenorhabditis Elegans by Quercetin. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 2008, 149, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzenberger, E.; Deusing, D.J.; Marx, C.; Boll, M.; Lüersen, K.; Wenzel, U. The Polyphenol Quercetin Protects the Mev-1 Mutant of Caenorhabditis Elegans from Glucose-Induced Reduction of Survival under Heat-Stress Depending on SIR-2.1, DAF-12, and Proteasomal Activity. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014, 58, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Stability of QF. The stability of Q in QF was measured at different time points after incubation in NGM plates, simulating the conditions used in studies with the worms, or test tubes for comparison. Each point corresponds to the result of a single experimental session (each of them determined in triplicate).

Figure 1.

Stability of QF. The stability of Q in QF was measured at different time points after incubation in NGM plates, simulating the conditions used in studies with the worms, or test tubes for comparison. Each point corresponds to the result of a single experimental session (each of them determined in triplicate).

Figure 2.

QF increased the heat stress tolerance. Synchronized worms were grown for 72 h at 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with A) QF (blue) or B) equimolar Q (red) dissolved in 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 and diluted with OP50 E. coli to administer 0, 100, or 200 μM Q. Control worms were maintained on NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli and 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 alone (Vehicle). Thermal stress was induced by incubating worms at 35°C, and the survival and motility were evaluated at different times later. A-B) Percentage of survival expressed as percentage of viable worms at time 0. Data are the mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments (N=75). **** p<0.0001 vehicle vs. all concentrations of treated worms at the corresponding time point, °°°° p<0.0001 200 μM vs. 50 and 100 μM QF or Q-treated worms at the corresponding time point, and A) §§§§ p<0.0001 50 μM QF vs. 100 and 200 μM QF and B) §§§§ p<0.0001 200 μM Q vs. 50 and 100 μM Q at the corresponding time point, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis. C) Percentages of survival and D) moving worms determined after 4 and 5 h of thermal stress of worms not treated (Vehicle) or treated with 100 μM unformulated Q or QF. Data are the mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments (N=75). **** p<0.0001 vs. Vehicle at the corresponding time point, and #### p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Figure 2.

QF increased the heat stress tolerance. Synchronized worms were grown for 72 h at 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with A) QF (blue) or B) equimolar Q (red) dissolved in 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 and diluted with OP50 E. coli to administer 0, 100, or 200 μM Q. Control worms were maintained on NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli and 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 alone (Vehicle). Thermal stress was induced by incubating worms at 35°C, and the survival and motility were evaluated at different times later. A-B) Percentage of survival expressed as percentage of viable worms at time 0. Data are the mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments (N=75). **** p<0.0001 vehicle vs. all concentrations of treated worms at the corresponding time point, °°°° p<0.0001 200 μM vs. 50 and 100 μM QF or Q-treated worms at the corresponding time point, and A) §§§§ p<0.0001 50 μM QF vs. 100 and 200 μM QF and B) §§§§ p<0.0001 200 μM Q vs. 50 and 100 μM Q at the corresponding time point, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis. C) Percentages of survival and D) moving worms determined after 4 and 5 h of thermal stress of worms not treated (Vehicle) or treated with 100 μM unformulated Q or QF. Data are the mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments (N=75). **** p<0.0001 vs. Vehicle at the corresponding time point, and #### p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Figure 3.

QF increased the resistance to oxidative stress. Synchronized worms were grown for 72 h at 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with QF or unformulated Q dissolved in 1% CMC containing 0.3% polysorbate 80 (vehicle) and diluted with OP50 E. coli to obtain 100 μM Q. Control worms were maintained on NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli and the corresponding volume of vehicle. Oxidative stress was induced by treating worms for 2 h at 20°C with 0.5 mM H2O2, and the A) pharyngeal motility was evaluated 24 h later. Pharyngeal pumping of worms is expressed as the percentage of pumps/min of vehicle-treated worms. Data are the mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments (N=40). B) To evaluate the protective effect of antioxidant compounds, worms were treated for 2 hours at 20°C with 0.5 mM hydrogen peroxide in the absence or presence of 284 µM ascorbic acid and 5 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC), and the pharyngeal motility was determined 24 h later. Pharyngeal pumping of worms was expressed as a percentage of pumps/min of vehicle-treated worms. Data are the mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments (N=30). *p<0.001, ** p<0.005, and **** p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Figure 3.

QF increased the resistance to oxidative stress. Synchronized worms were grown for 72 h at 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with QF or unformulated Q dissolved in 1% CMC containing 0.3% polysorbate 80 (vehicle) and diluted with OP50 E. coli to obtain 100 μM Q. Control worms were maintained on NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli and the corresponding volume of vehicle. Oxidative stress was induced by treating worms for 2 h at 20°C with 0.5 mM H2O2, and the A) pharyngeal motility was evaluated 24 h later. Pharyngeal pumping of worms is expressed as the percentage of pumps/min of vehicle-treated worms. Data are the mean ± SEM from 4 independent experiments (N=40). B) To evaluate the protective effect of antioxidant compounds, worms were treated for 2 hours at 20°C with 0.5 mM hydrogen peroxide in the absence or presence of 284 µM ascorbic acid and 5 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC), and the pharyngeal motility was determined 24 h later. Pharyngeal pumping of worms was expressed as a percentage of pumps/min of vehicle-treated worms. Data are the mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments (N=30). *p<0.001, ** p<0.005, and **** p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Figure 4.

Effect of QF and unformulated Q on the lifespan and health span of

C. elegans under physiological and heat-stress damage conditions. (A, B) Synchronized worms were plated on NGM plates seeded with

E. Coli OP50 and 100 µM Q or an equimolar concentration of QF dissolved in a solution containing 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 and left at 20°C. Control worms were plated on NGM plates seeded with

E. Coli OP50 and 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 (Vehicle). The (A) lifespan and (B) health span were scored daily. (C, D) Synchronized worms were grown for 72 h at 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with 100 µM Q or an equimolar concentration of QF dissolved in 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 and diluted with OP50

E. coli. Control worms were maintained on NGM plates seeded with OP50

E. coli and 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 alone (Vehicle). Thermal stress was induced by incubating worms at 35°C for 3 h. Worms were then transferred to 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with 100 µM Q or an equimolar concentration of QF or Vehicle. The (C) lifespan and (D) health span were scored daily. Data are the mean ± SEM. See

Table 2 for mean lifespan, health span, and statistical analyses.

Figure 4.

Effect of QF and unformulated Q on the lifespan and health span of

C. elegans under physiological and heat-stress damage conditions. (A, B) Synchronized worms were plated on NGM plates seeded with

E. Coli OP50 and 100 µM Q or an equimolar concentration of QF dissolved in a solution containing 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 and left at 20°C. Control worms were plated on NGM plates seeded with

E. Coli OP50 and 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 (Vehicle). The (A) lifespan and (B) health span were scored daily. (C, D) Synchronized worms were grown for 72 h at 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with 100 µM Q or an equimolar concentration of QF dissolved in 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 and diluted with OP50

E. coli. Control worms were maintained on NGM plates seeded with OP50

E. coli and 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 alone (Vehicle). Thermal stress was induced by incubating worms at 35°C for 3 h. Worms were then transferred to 20°C on NGM agar plates seeded with 100 µM Q or an equimolar concentration of QF or Vehicle. The (C) lifespan and (D) health span were scored daily. Data are the mean ± SEM. See

Table 2 for mean lifespan, health span, and statistical analyses.

Figure 5.

Effect of QF on AGEs. A) Western blot, representative of 3 biological replicates, of AGEs in samples extracted from worms of different ages grown at 20°C in the presence of 100 µM QF or Q dissolved in a solution containing 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80. Control worms were grown in the same experimental conditions in the presence of 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 (Vehicle, V). Proteins extracted from 20 worms were loaded in each gel lane and immunoblotted with anti-AGE-CML or anti-actin antibody. B) Quantification of total AGEs expressed as the mean volume of anti-AGE-CML bands (at 135 and 180 kDa) immunoreactivity normalized to the actin band. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5), *p<0.005 vs. the corresponding group at 3 days of adulthood, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Figure 5.

Effect of QF on AGEs. A) Western blot, representative of 3 biological replicates, of AGEs in samples extracted from worms of different ages grown at 20°C in the presence of 100 µM QF or Q dissolved in a solution containing 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80. Control worms were grown in the same experimental conditions in the presence of 1% CMC and 0.3% polysorbate 80 (Vehicle, V). Proteins extracted from 20 worms were loaded in each gel lane and immunoblotted with anti-AGE-CML or anti-actin antibody. B) Quantification of total AGEs expressed as the mean volume of anti-AGE-CML bands (at 135 and 180 kDa) immunoreactivity normalized to the actin band. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 5), *p<0.005 vs. the corresponding group at 3 days of adulthood, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Figure 6.

QF modulates the expression of genes associated with longevity and stress resistance. A) Expression level of the analyzed genes in worms exposed to thermal stress (heat-stressed condition) or not (physiological condition). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM normalized for the value obtained in physiological conditions. Data are from 3 independent experiments (N=15). *p<0.005, **p<0.001, and **** p<0.0001, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis. B, C) Effect of Q and QF on the expression of genes in worms B) maintained at physiological conditions and C) exposed to thermal stress. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments (N=15), and are normalized for the value obtained with vehicle. *p<0.005, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0005, **** p<0.0001, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Figure 6.

QF modulates the expression of genes associated with longevity and stress resistance. A) Expression level of the analyzed genes in worms exposed to thermal stress (heat-stressed condition) or not (physiological condition). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM normalized for the value obtained in physiological conditions. Data are from 3 independent experiments (N=15). *p<0.005, **p<0.001, and **** p<0.0001, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis. B, C) Effect of Q and QF on the expression of genes in worms B) maintained at physiological conditions and C) exposed to thermal stress. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments (N=15), and are normalized for the value obtained with vehicle. *p<0.005, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0005, **** p<0.0001, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Table 1.

List of the primers used in the study to perform gene-expression analysis.

Table 1.

List of the primers used in the study to perform gene-expression analysis.

| Name |

Sequence (5’-3’) |

|

skn-1- Forward |

5’-GCGACGAGACGAGACGATAA-3’ |

|

skn-1-Reverse |

5’-TGAGGTGTTGGACGATGGTG-3’ |

|

sod-3- Forward |

5‘-GGCTGTTTCGAAAGGGAATCT-3‘ |

|

sod-3-Reverse |

5‘-CCTTTGAAGGTTCTCCACCA-3‘ |

|

daf-16 - Forward |

5‘-ATCAGACATCGTTTCCTTCGG-3‘ |

|

daf-16 -Reverse |

5‘-TTAACCGTTTCTCTGGACTAGC-3‘ |

|

hsf-1 - Forward |

5‘-CGAGGATCCACTCAGACAGC-3‘ |

|

hsf-1 -Reverse |

5‘-GTAGTTTGGGTCCGGCACAT-3‘ |

|

hsp-16.2- Forward |

5‘-TCCATCTGAGTCTTCTGAGATTGTT-3‘ |

|

hsp-16.2 -Reverse |

5‘-GATAGCGTACGACCATCCAAA-3‘ |

|

hsp-70- Forward |

5‘-AGCCGGTTGAAAAGGCACT-3‘ |

|

hsp-70 -Reverse |

5‘-AGTTGAGGTCCTTCCCATTGAA-3‘ |

|

gst-4 - Forward |

5‘-CTTGGCAAGAAAATTTGGACTC-3‘ |

|

gst-4 -Reverse |

5‘-GCGTCACTTCCATAGAAAACG-3‘ |

|

sod-1- Forward |

5‘-AGGTCTCCAACGCGATTTTT-3‘ |

|

sod-1 -Reverse |

5‘-TCGGACTTCTGTGTGATCCAG-3‘ |

|

cdc-42 - Forward |

5’-CTGTTGTGGTGGGTCGAGAG-3’ |

|

cdc-42 - Reverse |

5’-GTTGACGCAGAAGGGACTGA-3’ |

|

y45F10d.4 - Forward |

5’-ATCTTCCCTGGCAACCGAAT-3’ |

|

y45F10d.4 - Reverse |

5’-TGGGCGAGCATTGAACAGT-3’ |

Table 2.

QF affects worms' survival and health span only under heat-stress damage conditions.

Table 2.

QF affects worms' survival and health span only under heat-stress damage conditions.

| |

PHYSIOLOGIC CONDITION |

HEAT-STRESS CONDITION |

| Vehicle |

Q |

QF |

Vehicle |

Q |

QF |

| Sample size |

120 |

120 |

120 |

120 |

123 |

120 |

| Censor |

11 |

16 |

18 |

3 |

8 |

17 |

Median of survival

(days ± SEM) |

18.28 ± 0.32 |

18.80 ± 0.29 |

18.21 ± 0.33 |

5.27 ± 0.13 |

8.16 ± 0.46**** |

7.94 ± 0.48**** |

Lifespan

Improvement rate (%) |

- |

2.8 |

0 |

- |

54.8 |

50.7 |

Median of moving

Worms (days ± SEM) |

16.76 ± 0.29 |

17.43 ± 0.30 |

16.57 ± 0.3 |

4.88 ± 0.08 |

7.45 ± 0.43**** |

7.49 ± 0.48**** |

| Health span improvement rate (%) |

- |

4.0 |

0 |

0 |

52.7 |

53.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).