1. Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most frequently diagnosed malignancy among women globally and is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality. According to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), over 2.3 million new cases of breast cancer were reported worldwide in 2020, accounting for 11.7% of all cancer cases and surpassing lung cancer as the most common cancer in women [

1]. Mortality remains disproportionately high in low- and middle-income countries due to limited access to early detection and effective treatment. The etiology of breast cancer is complex and multifactorial, involving genetic predisposition, hormonal influences, environmental exposures, and lifestyle factors. While high-penetrance mutations such as

BRCA1/2 are well known, most cases are sporadic, influenced by modifiable risk factors including obesity, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and reproductive history [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Recent decades have witnessed an increasing focus on the role of systemic inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and hormonal imbalances in breast carcinogenesis. Amidst this evolving paradigm, the gut microbiota has emerged as a novel player in modulating these risk factors, potentially influencing both the onset and progression of breast cancer. Consequently, understanding gut microbiota dynamics may open new avenues for prevention, risk stratification, and therapy.

The human body is host to an astonishing array of microorganisms collectively known as the microbiota which outnumber our own cells and collectively contribute to essential biological functions [

6]. Among these, the gut microbiota has emerged as a central player in maintaining systemic health, orchestrating complex interactions across metabolic, immunologic, and endocrine systems [

7,

8]. What was once considered a passive bystander is now recognized as a dynamic ecosystem with the potential to shape disease trajectories, including those of cancer. Recent years have witnessed a paradigm shift in oncology: the realization that microbial ecosystems, particularly those residing in the gastrointestinal tract, may influence cancer initiation, progression, and response to therapy [

9,

10,

11]. In the context of breast cancer, the most prevalent malignancy among women worldwide emerging evidence suggests that microbial dysbiosis, estrogen metabolism, immune signaling, and systemic inflammation may converge through the gut axis to influence tumor biology. The human gut harbors a dense and dynamic microbial ecosystem, comprising trillions of microorganisms collectively referred to as the gut microbiota. This community is dominated by four major bacterial phyla:

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidetes,

Actinobacteria, and

Proteobacteria, with species from

Lactobacillus,

Bifidobacterium, and

Bacteroides being especially prevalent in a healthy individual [

12]. The gut microbiota plays a multifaceted role in host physiology, extending far beyond the gastrointestinal tract. In terms of digestion, gut microbes aid in the breakdown of complex polysaccharides and fibers, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which serve as energy sources for colonocytes and modulate inflammation [

13,

14]. Beyond nutrient metabolism, these commensal microbes profoundly influence the immune system, training innate and adaptive responses and contributing to immune tolerance [

15]. A pivotal yet less recognized role of the gut microbiota is in hormonal regulation, especially the metabolism of estrogens through a subset of microbial genes known as the estrobolome. The estrobolome comprises bacteria capable of producing β-glucuronidase, an enzyme that deconjugates estrogen metabolites in the gut, facilitating their reabsorption into systemic circulation [

16]. This recirculation of estrogens has significant implications for hormone-driven conditions, including breast cancer. As such, the gut microbiota can be considered a critical endocrine organ, influencing not only digestion and immunity but also systemic hormonal balance. The systemic impact of the gut microbiota is now well-established, with mounting evidence linking microbial imbalance referred to as dysbiosis to a spectrum of chronic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), type-2 diabetes (T2D), type-1 diabetes (T1D) cardiovascular disease (CVD), and various cancers [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Dysbiosis can arise from multiple factors, including antibiotic use, dietary imbalances, environmental toxins, chronic stress, and aging, disrupting microbial diversity and function. In cancer biology, the gut microbiota is believed to modulate several oncogenic processes through immune modulation, metabolite production, and hormonal regulation [

21]. For example, bacterial fermentation products like SCFAs have been shown to exert anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects, while others such as secondary bile acids and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) may promote tumorigenesis under dysbiosis conditions [

22,

23]. Specific to breast cancer, mechanistic links have been proposed through the estrobolome, gut-associated immune responses, and microbial metabolites that influence cellular proliferation, DNA damage, angiogenesis, and apoptosis [

24]. Additionally, the microbiota-gut-brain axis is emerging as a potential modulator of stress responses and neuroimmune interactions that may indirectly influence tumor progression and metastasis.

Given the growing interest in the intersection of gut microbiota and breast cancer, this review aims to synthesize current knowledge regarding their mechanistic and clinical interplay. It will explore the composition and functional roles of gut microbiota in health, including its role in digestion, immune modulation, metabolism, and estrogen regulation through the estrobolome. The review will then delve into the concept of dysbiosis, elucidating its causes and systemic consequences, especially in relation to breast cancer risk. We will further dissect mechanistic links between gut microbiota and breast cancer, focusing on four major domains: estrogen metabolism and the estrobolome, immune modulation, microbial metabolite production, and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. These pathways collectively underscore the potential for microbial communities to influence breast tumor biology, particularly hormone-receptor-positive subtypes. Moreover, we will present preclinical and clinical evidence supporting the association between gut dysbiosis and breast cancer, including microbial signatures observed in cancer patients. A dedicated section will review the therapeutic potential of biotics including probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics in restoring gut microbial balance and mitigating cancer risk or progression. The review will also assess clinical and preclinical studies on biotics in breast cancer contexts, evaluating their safety, efficacy, and mechanisms of action. Finally, we will address existing challenges and future directions, highlighting gaps in the current literature, the need for personalized approaches, integration with conventional cancer therapies, and regulatory considerations for microbiota-based interventions. So, this review explores the intricate relationship between gut microbiota and breast cancer, with a focus on underlying mechanisms, clinical implications, and emerging interventions. By unpacking the science of microbial endocrinology, immunomodulation, and metabolite signaling, we aim to position the gut microbiota not merely as a biomarker but as a modifiable factor in breast cancer pathogenesis and treatment.

2. Gut Microbiota: Composition and Functions

Human gut microbiota has emerged as a critical determinant of systemic health, influencing a range of physiological processes that extend well beyond the gastrointestinal tract. In the context of breast cancer, a mounting body of evidence suggests that the microbial communities residing in the gut serve as an integral component in the regulation of hormonal balance, immune surveillance, and inflammation factors that collectively modulate cancer susceptibility and progression [

25,

26]. This section delves into the taxonomic composition and functional roles of the gut microbiota, with particular emphasis on its metabolic, immunological, and endocrine dimensions, setting the stage for a mechanistic understanding of how microbial imbalances may contribute to breast carcinogenesis.

2.1. Microbial Composition in a Healthy Human Gut

Human guts harbor a diverse and densely populated ecosystem of microorganisms primarily bacteria but also including viruses, fungi, archaea, and protozoa collectively referred to as the gut microbiota. This microbial community consists of an estimated 10

14 cells and encodes over 100 times more genes than the human genome. In healthy individuals, the gut microbiota is dominated by bacterial phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which collectively account for over 90% of the total bacterial population [

27]. Other consistently observed phyla include

Actinobacteria (e.g.,

Bifidobacterium spp.),

Proteobacteria,

Verrucomicrobia (e.g.,

Akkermansia muciniphila), and Fusobacteria. At the genus level,

Bacteroides,

Faecalibacterium,

Ruminococcus,

Lactobacillus, and

Bifidobacterium represent core taxa with established roles in host physiology [

28]. Notably,

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and

Akkermansia muciniphila have been identified as next-generation probiotics due to their potent anti-inflammatory properties [

29,

30,

31]. The richness and diversity of these microbial communities are considered hallmarks of a healthy gut ecosystem, contributing to microbial resilience and functional redundancy [

32]. Perturbations in this balanced ecosystem, as explored in later sections, may predispose individuals to chronic inflammation and hormone dysregulation, creating a pro-oncogenic milieu.

2.2. Functional Capacities of the Gut Microbiota

The gut microbiota fulfills an expansive array of physiological functions that are indispensable to host health and homeostasis. These can be broadly categorized into four domains: digestion and nutrient assimilation, immune modulation, metabolic regulation, and endocrine control, each of which has implications for breast cancer biology. The gut microbiota facilitates the breakdown of dietary polysaccharides, fibers, and resistant starches that are otherwise indigestible by human enzymes. This microbial fermentation yields short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) namely acetate, propionate, and butyrate that serve as energy substrates for colonocytes, reinforce intestinal barrier integrity, and exhibit immunomodulatory and anti-neoplastic effects [

33]. Butyrate has been shown to inhibit histone deacetylases, thereby regulating gene expression and suppressing tumorigenesis [

34,

35]. Additionally, microbial activity contributes to the synthesis of essential micronutrients such as vitamin K and B-complex vitamins, further influencing host metabolic health [

36,

37]. The gut microbiota plays a foundational role in shaping the host immune system from infancy through adulthood [

38]. Commensal bacteria promote the development of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), prime innate immune responses, and regulate the balance between pro-inflammatory (Th17) and anti-inflammatory (Treg) T cell populations [

8]. Through molecular patterns recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), gut microbes can modulate cytokine production and immune cell trafficking [

39,

40]. Importantly, this immune crosstalk extends systemically, influencing distant tissues including the breast through circulation of cytokines, chemokines, and immune effector cells. By regulating bile acid metabolism, SCFA production, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels, the gut microbiota significantly impacts host metabolic pathways [

41]. For instance, secondary bile acids derived from microbial metabolism act as ligands for nuclear receptors like FXR and TGR5, influencing lipid and glucose homeostasis [

42]. In parallel, microbial-derived LPS can provoke chronic low-grade inflammation, a known driver of tumorigenesis via activation of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway [

43]. Thus, dysregulated microbial metabolism may establish a pro-inflammatory, insulin-resistant state that fuels both metabolic syndromes and cancer progression. Perhaps one of the most compelling roles of gut microbiota in breast cancer biology lies in its regulation of systemic estrogen levels. This endocrine function is primarily mediated by a microbial subcommunity known as the estrobolome.

2.3. The Estrobolome: Microbial Gatekeeper of Estrogen Homeostasis

The estrobolome is a term coined to describe the collection of gut microbial genes capable of metabolizing estrogens, primarily through the production of the enzyme β-glucuronidase [

16]. This enzymatic activity plays a pivotal role in the enterohepatic circulation of estrogens, a process with direct implications for hormonal homeostasis and hormone-sensitive diseases such as breast cancer. Under physiological conditions, estrogens mainly estrone, estradiol, and estriol which are metabolized in the liver through phase II conjugation reactions, where they are bound to glucuronide or sulfate groups [

44]. This conjugation renders them water-soluble and facilitates their excretion via bile into the intestinal lumen. However, once in the gut, estrogens can be deconjugated by microbial β-glucuronidase enzymes, especially those produced by bacteria in the phyla Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria. Deconjugated, or “free,” estrogens can then be reabsorbed into the bloodstream via the intestinal wall, thereby increasing systemic estrogen levels [

45].

This microbial-mediated reactivation of estrogen constitutes a critical regulatory checkpoint in estrogen metabolism. A balanced estrobolome contributes to hormonal homeostasis, ensuring that circulating estrogen levels remain within a physiological range. However, disruptions in the gut microbiota such as those caused by antibiotics, Western dietary patterns, environmental toxins, or stress can disturb the functional capacity of the estrobolome, either enhancing or impairing β-glucuronidase activity [

46]. Both scenarios are potentially harmful. On one hand, excessive β-glucuronidase activity, often a hallmark of dysbiosis, can lead to abnormally high levels of circulating estrogens, which have been implicated in the development and progression of estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancers [

45]. On the other hand, microbial depletion may lower estrobolomic activity, reducing the enterohepatic recirculation of estrogens and possibly disrupting feedback regulation in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Recent studies have demonstrated that women with higher systemic estrogen levels tend to have distinct gut microbial signatures, with increased relative abundance of

Escherichia,

Clostridium, and

Bacteroides species bacteria known to produce β-glucuronidase. A pivotal study by Fuhrman

et al. (2014) found that postmenopausal women with higher urinary estrogen levels had a more diverse gut microbiome and higher microbial gene counts related to estrogen metabolism, particularly β-glucuronidase activity [

47]. Moreover, reduced microbial diversity and estrobolome gene expression have been associated with obesity, metabolic syndrome, and inflammation, all of which are recognized breast cancer risk factors [

48]. Importantly, not all β-glucuronidase activity is harmful. The context, intensity, and location of the enzyme’s action are key. While moderate levels of β-glucuronidase contribute to normal estrogen recycling and homeostasis, unregulated or excessive activity may shift the hormonal milieu toward a pro-oncogenic state [

16]. This underlines the need for precision modulation of the estrobolome, rather than indiscriminate suppression. Overall, the estrobolome acts as a critical microbial-endocrine interface, regulating estrogen availability through microbial enzymatic actions. Its modulation offers a novel, microbiota-targeted avenue for breast cancer prevention and therapy, particularly in estrogen-dependent subtypes. As research advances, the estrobolome may become a biomarker of hormonal risk and a therapeutic target in precision oncology.

3. Dysbiosis: Definition and Mechanisms

The human gut microbiota, a dense and dynamic microbial ecosystem, is essential to numerous physiological functions, ranging from nutrient metabolism to immune regulation and endocrine signaling. Its balance and diversity are critical for sustaining host health. However, when the composition, density, or functionality of the microbiota becomes disrupted, a condition termed “dysbiosis” arises. Gut dysbiosis reflects a pathological imbalance in the microbial community, and growing evidence implicates it as a key contributor to a broad spectrum of chronic diseases, including metabolic syndrome, autoimmune conditions, neurodegenerative disorders, and various cancers, notably breast cancer [

49].

3.1. What Is Dysbiosis?

Dysbiosis refers to any qualitative or quantitative perturbation in the gut microbiome that disturbs the equilibrium between commensal and pathogenic organisms. It is characterized by:

- ■

A loss of microbial diversity

- ■

A reduction in beneficial bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium)

- ■

An overgrowth of potentially pathogenic taxa (e.g., Escherichia coli, Clostridium difficile)

- ■

A shift in microbial metabolic activity that leads to the production of deleterious compounds

Dysbiosis may be transient or chronic, and its consequences depend on the degree of microbial imbalance and the resilience of the host [

50]. While a healthy microbiota is resilient to perturbation, sustained dysbiosis undermines barrier integrity, disrupts immune tolerance, and alters systemic metabolic and hormonal signals, establishing a microenvironment conducive to tumorigenesis.

3.2. Causes of Gut Dysbiosis

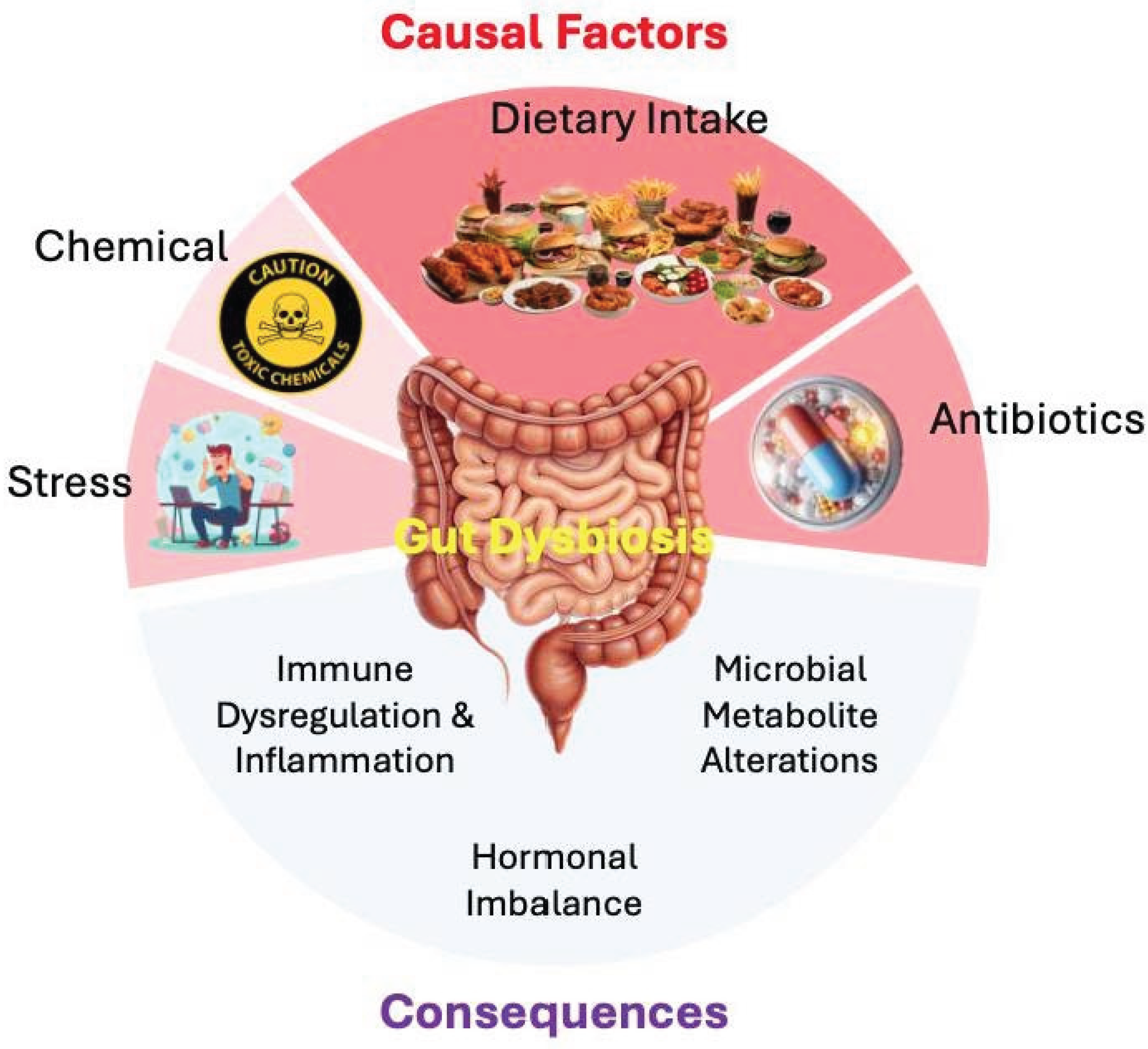

Several endogenous and exogenous factors can trigger dysbiosis. In the context of modern lifestyles, four primary categories are implicated and presented in

Figure 1:

Diet

One of the most influential modulators of gut microbiota is dietary intake. Diets low in fiber and high in refined sugars, saturated fats, and processed foods the hallmark of Western dietary patterns have been associated with reduced microbial diversity and increased abundance of pro-inflammatory species. These diets deprive commensal bacteria of fermentable substrates, particularly non-digestible fibers (prebiotics), leading to decreased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, a key metabolite for maintaining mucosal integrity and anti-inflammatory responses. Moreover, diets high in animal protein and fat promote the proliferation of bile-tolerant bacteria (e.g.,

Bilophila wadsworthia) while reducing beneficial saccharolytic bacteria [

51]. The resultant shifts not only promote inflammation but may also affect estrogen metabolism via the estrobolome, thereby influencing breast cancer risk.

3.3. Antibiotic Use

Antibiotics are indispensable in modern medicine, yet their broad-spectrum activity can indiscriminately eliminate both harmful and beneficial bacteria. Even short courses of antibiotics can cause long-lasting changes in the gut microbiota composition, sometimes persisting for months or years. This microbial vacuum can be exploited by opportunistic and pathogenic organisms, leading to reduced colonization resistance, metabolic dysregulation, and impaired immunological responses. In the context of estrogen metabolism, antibiotic-induced depletion of estrobolome taxa reduces β-glucuronidase activity, potentially impairing estrogen recycling and hormonal balance [

52]. This has been observed in animal studies where antibiotic treatment altered estrogen plasma levels and impacted estrogen-responsive tissues.

3.4. Environmental Toxins

Chronic exposure to environmental toxins such as pesticides, heavy metals (e.g., arsenic, lead), plasticizers (e.g., BPA, phthalates), and air pollutants have been shown to alter gut microbial profiles [

53]. These xenobiotics may exert direct antimicrobial effects or modulate host-microbe interactions via endocrine-disrupting properties. For example, bisphenol A (BPA), a known estrogen mimic, can disrupt microbial community structure and potentially synergize with dysbiosis microbiota to amplify estrogenic signaling, thereby increasing the likelihood of estrogen-receptor-positive breast tumor development [

52].

3.5. Psychosocial and Physiological Stress

The gut-brain axis represents a bi-directional communication system between the central nervous system and the gut microbiota. Chronic stress, through the release of glucocorticoids and catecholamines, alters gut motility, mucosal permeability, and immune functional of which impact microbial ecology [

54]. Stress-induced dysbiosis is associated with reduced abundance of beneficial commensals and increased pro-inflammatory bacteria, which in turn stimulate immune dysregulation and low-grade systemic inflammation [

55], two hallmarks of the cancer-promoting microenvironment.

3.6. Consequences of Dysbiosis on Host Physiology

Dysbiosis exerts widespread effects on host physiology through multiple interrelated pathways. In the context of breast cancer, three principal domains warrant special attention: a balanced microbiota plays an essential role in promoting immune tolerance and preventing excessive inflammation [

15]. Dysbiosis skews this balance by enhancing gut permeability (“leaky gut”), allowing microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to enter systemic circulation [

49]. This leads to chronic low-grade inflammation, which can fuel tumorigenesis by promoting angiogenesis, inhibiting apoptosis, and facilitating immune evasion by emerging tumor cells [

56]. In addition, dysbiosis impairs regulatory T cell (Treg) activity and disrupts antigen presentation that further impairs the anti-tumor immune surveillance [

57]. This is particularly critical in breast cancer, where immune infiltration patterns and inflammatory profiles are key determinants of prognosis and therapeutic response. The gut microbiota, especially the estrobolome, is integral to estrogen regulation. Dysbiosis can either augment or suppress β-glucuronidase-mediated deconjugation of estrogens, leading to hormonal imbalances that are directly implicated in estrogen-dependent tumor proliferation [

16,

45,

46]. Elevated systemic estrogen levels, secondary to microbial dysregulation, have been observed in postmenopausal women with increased breast cancer risk [

58]. Furthermore, gut bacteria influence the metabolism of other hormones such as androgens, progesterone, and cortisol [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. Such disruptions in the endocrine landscape can synergize with oncogenic mutations, driving carcinogenesis and progression in hormone-responsive breast cancers. Dysbiosis alters microbial metabolic outputs, including the synthesis of SCFAs (e.g., butyrate, propionate), bile acids, and tryptophan metabolites. These compounds exert potent epigenetic, immunomodulatory, and metabolic effects. For instance, butyrate known for its anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative properties and inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs), thereby influencing gene expression relevant to tumor suppression [

22,

66,

67,

68]. Secondary bile acids, when elevated due to dysbiosis, can be cytotoxic, pro-inflammatory, and genotoxic [

69,

70]. Tryptophan metabolites such as indole derivatives modulate immune responses through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), influencing cancer immunity [

71,

72,

73,

74]. Collectively, these shifts in microbial metabolite profiles can alter host cell signaling, disrupt DNA repair mechanisms, and create a pro-carcinogenic epigenetic landscape conducive to breast cancer initiation and progression.

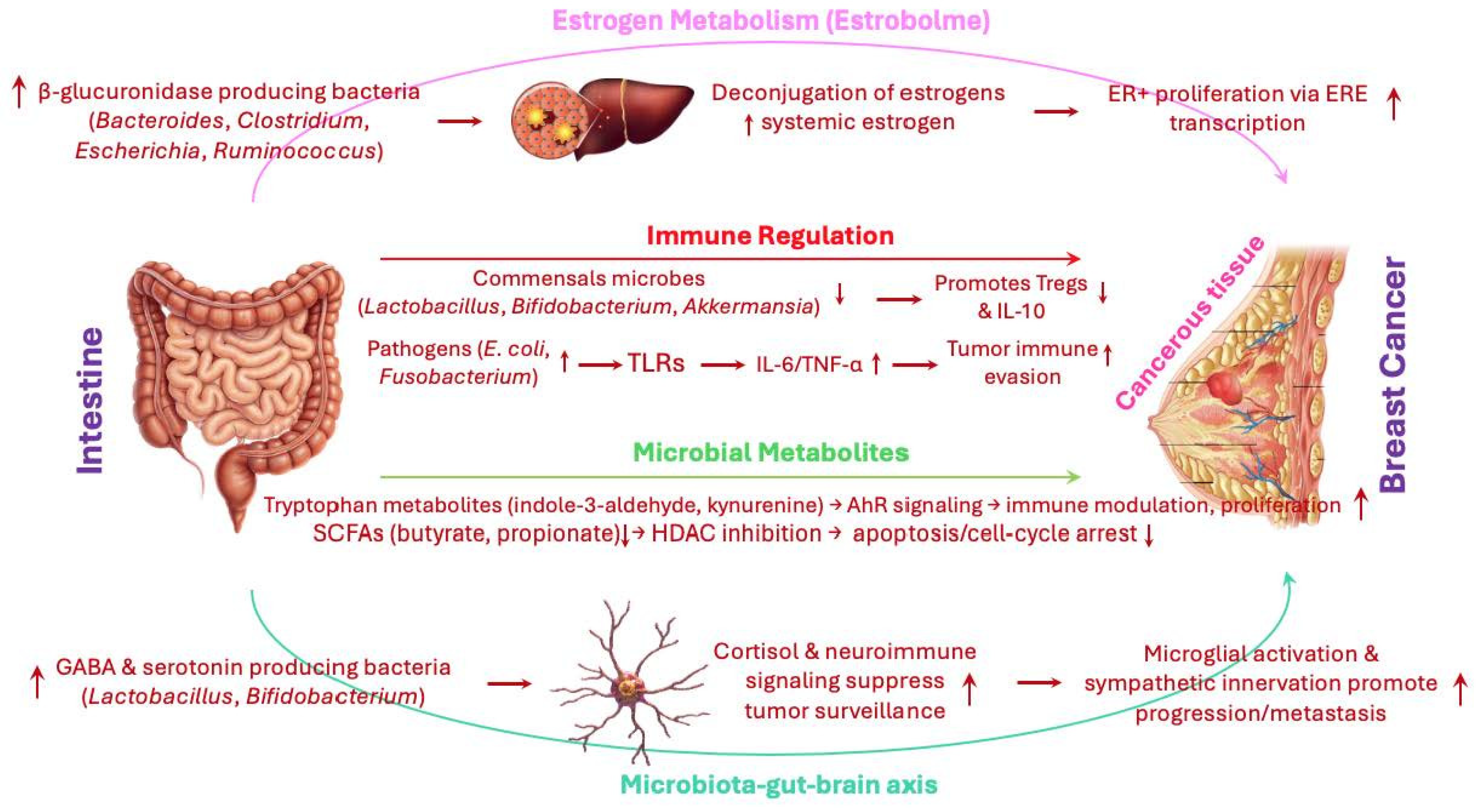

4. Mechanistic Links Between Gut Microbiota and Breast Cancer

The interplay between gut microbiota and breast cancer development is multifaceted, involving hormonal modulation, immune regulation, and metabolic signaling (

Figure 2). Emerging evidence suggests that specific microbial functions and metabolites orchestrate complex interactions with the host endocrine and immune systems, directly impacting tumorigenesis. This section explores the mechanistic underpinnings that link gut microbial activity to breast cancer pathogenesis.

4.1. Estrogen Metabolism and the Estrobolome

One of the most studied mechanistic pathways linking gut microbiota to breast cancer is the regulation of systemic estrogen levels by the estrobolome a subset of the gut microbiota capable of metabolizing estrogens. Estrogens undergo hepatic conjugation and are excreted into the bile as inactive glucuronides. In the gut, bacterial β-glucuronidase enzymes, predominantly from

Bacteroides,

Clostridium,

Escherichia, and

Ruminococcus species, deconjugate these estrogens, allowing them to be reabsorbed into the enterohepatic circulation [

16,

45,

75]. Elevated β-glucuronidase activity has been associated with increased systemic estrogen levels a known risk factor for hormone-receptor-positive breast cancers [

76,

77]. Higher systemic estrogen levels can enhance the proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer cells via estrogen response element (ERE)-mediated transcription. Studies have shown that postmenopausal women with reduced gut microbial diversity and increased abundance of β-glucuronidase-producing bacteria exhibit elevated plasma estrogen levels [

47]. These findings suggest that dysbiosis of the estrobolome can potentially increase breast cancer risk or influence treatment outcomes in ER+ subtypes.

4.2. Immune System Modulation

Gut microbiota modulates immune responses through antigen presentation, cytokine production, and maintenance of mucosal integrity. These immunological changes can have downstream effects on systemic inflammation and tumor surveillance. Commensal bacteria such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Akkermansia muciniphila promote regulatory T-cell (Treg) differentiation and the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10, thereby maintaining immune homeostasis [

78]. Conversely, pathogenic taxa such as

Escherichia coli and

Fusobacterium nucleatum can activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs), induce pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), and drive chronic inflammation conditions that favor tumor development and progression [

79,

80,

81,

82]. Chronic inflammation induced by microbial dysbiosis contributes to immune evasion by increasing myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and Treg infiltration in the tumor microenvironment. This suppressive milieu inhibits cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity, facilitating tumor survival. Moreover, bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can potentiate NF-κB signaling and COX-2 expression, further amplifying inflammatory cascades associated with breast cancer progression [

79].

4.3. Microbial Metabolites

Microbial fermentation and metabolism yield bioactive compounds such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), secondary bile acids, and tryptophan metabolites that significantly influence host cell signaling pathways. SCFAs primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate are produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers. Butyrate exhibits anti-tumorigenic properties through histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition, leading to epigenetic regulation of genes involved in apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [

83]. Secondary bile acids like deoxycholic acid (DCA), derived from microbial metabolism of primary bile acids, have been implicated in carcinogenesis due to their pro-inflammatory and DNA-damaging properties [

8]. Tryptophan-derived metabolites, such as indole-3-aldehyde and kynurenine, activate aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling, which influences immune cell differentiation and intestinal barrier function. Dysregulated AhR signaling has been observed in breast cancer tissues and is thought to contribute to immune evasion and tumor progression [

84]. These microbial metabolites can directly impact breast epithelial cells by modulating signaling pathways involved in proliferation (e.g., PI3K/Akt/mTOR), apoptosis (e.g., Bcl-2/Bax ratio), and angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF expression). Butyrate, for instance, has been shown to suppress angiogenesis and metastasis in breast cancer models by downregulating hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) [

85,

86].

4.4. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

The bidirectional communication between the gut and brain, modulated by microbial metabolites and neuroactive compounds, also plays a role in cancer biology. Psychological stress is an established risk factor for cancer progression and can be modulated by gut microbiota through the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Microbes such as

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium produce gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin, and other neuromodulators that influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Stress-induced activation of the HPA axis leads to increased cortisol levels, which can suppress immune surveillance and facilitate tumorigenesis [

87,

88,

89,

90]. Microbial dysbiosis has also been associated with neuroinflammation and alterations in microglial function, contributing to a permissive environment for cancer metastasis, particularly to the brain. In breast cancer models, microbiota-induced neuroimmune signaling has been implicated in the regulation of sympathetic innervation of tumors, thereby influencing tumor growth and dissemination [

91]. Overall, the microbiota-gut-brain axis emerges as a critical mediator linking psychological stress, neuroimmune signaling, and cancer progression. By shaping HPA axis activity, immune surveillance, and neuroinflammatory responses, gut microbes influence both tumor growth and metastatic potential. These insights highlight the gut-brain axis as a promising frontier for integrative cancer prevention and therapeutic strategies.

5. Microbial Signatures of Breast Cancer: Linking Gut Health to Hormonal and Immune Pathways

Gut dysbiosis refers to a disruption in the normal composition and function of the gut microbiome, characterized by reduced microbial diversity, loss of beneficial commensals, and an expansion of pathogenic or pro-inflammatory taxa [

92]. This imbalance can profoundly alter systemic homeostasis, contributing to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and hormonal imbalances key risk factors implicated in breast cancer pathophysiology. The mechanisms through which gut dysbiosis may promote breast cancer include: (i) modulation of estrogen metabolism via the estrobolome[

93]; (ii) activation of immune signaling cascades promoting a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment [

94]; and (iii) production of microbial metabolites that influence host epigenetics and cell proliferation [

95]. These pathways have been validated through a spectrum of experimental approaches, including preclinical models and human studies, reinforcing the concept that gut microbiota may function as both a mediator and a marker of breast cancer risk [

96]. The interplay between the gut microbiota and systemic host physiology has emerged as a focal point in understanding the etiopathogenesis of breast cancer. Mounting evidence from both experimental and clinical investigations suggests that disruptions in the gut microbial ecosystem commonly referred to as gut dysbiosis can modulate host hormonal milieu and immune function in ways that may promote mammary tumorigenesis. In this context, the identification of distinct microbial signatures associated with breast cancer has offered new avenues for both diagnostic and therapeutic innovation. This section synthesizes the current understanding of the evidence linking gut dysbiosis to breast cancer, drawing from preclinical models, epidemiological investigations, and microbiome profiling studies.

Advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies and integrative metagenomic analyses have significantly enhanced our ability to characterize the gut microbiota in relation to breast cancer in both clinical and pre-clinical studies [

97]. These methodologies have uncovered distinct microbial taxa and functional gene profiles that are recurrently associated with breast cancer presence, progression, and subtype specificity [

98]. Notably, a consistent pattern of compositional and functional dysbiosis has emerged in breast cancer cohorts, marked by a relative depletion of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing commensals such as

Roseburia and

Eubacterium rectale, alongside an enrichment of pro-inflammatory genera including

Prevotella,

Desulfovibrio, and specific

Clostridium spp [

99,

100]. This shift in microbial ecology contributes to a state of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation and is further implicated in the disruption of mucosal immunity and mucin layer integrity, thereby fostering a microenvironment conducive to tumorigenesis [

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106]. Metagenomic profiling has revealed functional alterations in microbial pathways that may mechanistically link gut dysbiosis to breast cancer biology. These include upregulated microbial gene networks involved in xenobiotic degradation, estrogen metabolism, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis each of which can influence host immune modulation and hormonal homeostasis [

99]. Elevated microbial conversion of primary to secondary bile acids, such as deoxycholic acid, has been shown to induce oxidative stress, DNA damage, and increased epithelial proliferation, all of which are recognized as contributors to carcinogenesis [

107,

108]. Importantly, these microbial alterations are not confined to the gut milieu. Recent findings suggest that microbial DNA and metabolites may translocate into systemic circulation and localize to extraintestinal tissues, including the breast tumor microenvironment. Here, they can modulate immune cell phenotypes, cytokine production, and tumor cell behavior, thus acting as functional modulators of cancer progression [

109,

110,

111].

A growing body of literature supports the existence of breast cancer-associated microbial signatures distinct constellations of microbial taxa and metabolic functions that correlate with disease presence, subtype differentiation, and clinical outcomes. Among these, the estrobolome a subset of gut microbial genes capable of metabolizing estrogens has garnered particular attention [

45,

112]. Dysregulation of the estrobolome, often characterized by increased β-glucuronidase activity, enhances enterohepatic recirculation of deconjugated estrogens, leading to elevated systemic estrogen levels [

45,

113]. This hormonal reactivation is especially relevant for estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer, where increased estrogen bioavailability can directly stimulate tumor growth [

48]. Higher relative abundances of

Enterobacteriaceae,

Clostridium, and

Bacteroides spp. have been associated with elevated estrobolome activity and increased breast cancer risk, particularly among postmenopausal women [

114]. In addition to hormonal modulation, immune-related microbial alterations have also been implicated in breast cancer pathophysiology [

114]. Enrichment of pro-inflammatory taxa such as

Desulfovibrio,

Bilophila wadsworthia, and LPS-producing

Gammaproteobacteria can activate innate immune receptors including TLR4 and NOD2, driving chronic inflammation and immune cell recruitment to the tumor microenvironment [

100,

115,

116,

117]. Conversely, the depletion of immunoregulatory commensals such as

Lactobacillus,

Roseburia, and

Faecalibacterium undermines regulatory T cell (Treg) induction and mucosal barrier integrity, thereby exacerbating inflammation and promoting neoplastic transformation [

118].

Emerging evidence further suggests that microbial signatures may differ by breast cancer subtype. ER+ tumors are frequently associated with heightened β-glucuronidase activity and increased abundance of estrogen-metabolizing microbes, whereas triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is more commonly linked to severe dysbiosis, pro-inflammatory microbial profiles, and diminished SCFA production [

119,

120]. These subtype-specific microbial patterns hold significant diagnostic and prognostic potential. Indeed, machine learning models leveraging microbiome-derived features have demonstrated robust accuracy in distinguishing between breast cancer subtypes and predicting therapeutic response, underscoring the potential of gut microbial signatures as both non-invasive biomarkers and actionable targets in personalized oncology.

6. Role of Biotics in Modulating Gut Microbiota

Biotics comprising probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics have emerged as promising modulators of gut microbial composition and function, offering novel strategies to mitigate breast cancer risk by restoring microbial homeostasis. These interventions target specific axes of gut-host communication, including microbial metabolite production, mucosal immunity, endocrine signaling, and intestinal barrier function [

121,

122]. As evidence continues to reveal microbiota’s critical influence on estrogen metabolism, immune homeostasis, and systemic inflammation, biotics represents a rational, modifiable approach to alter breast cancer susceptibility and progression.

Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that confer health benefits when administered in adequate amounts, have been extensively studied for their immunomodulatory and anti-carcinogenic effects [

123,

124]. Among the most investigated genera are

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium, which exert pleiotropic actions through multiple host-microbiota interactions [

125,

126]. Certain

Lactobacillus strains inhibit bacterial β-glucuronidase activity in the gut, thus reducing enterohepatic recirculation of estrogens and lowering systemic estrogen exposure a key hormonal factor implicated in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer [

127,

128,

129]. Concurrently, probiotics can modulate immune function by enhancing mucosal immunity, increasing regulatory T-cell populations, promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10), and dampening pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and TNF-α [

130,

131,

132]. Importantly, probiotics also strengthen gut barrier integrity by upregulating tight junction proteins such as Zo1, occludin and claudins, thereby preventing microbial translocation and systemic endotoxemia, which are known to contribute to chronic inflammation and cancer progression [

21,

131,

133,

134,

135]. Preclinical studies in mammary tumor models have demonstrated that the administration of Lactobacillus casei or Bifidobacterium longum can reduce tumor burden and promote antitumor immune responses. Although clinical data remain limited, early-phase trials suggest that probiotic supplementation may improve systemic inflammation and enhance tolerance to anticancer therapies in breast cancer patients.

Prebiotics, in contrast, are defined as selectively fermentable substrates that promote the growth and activity of beneficial gut microbes [

136,

137,

138]. Commonly studied prebiotics include inulin, fructooligosaccharides (FOS), and galactooligosaccharides (GOS), all of which escape digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract and undergo fermentation in the colon by commensal bacteria [

139,

140]. This process results in the production of SCFAs notably butyrate, acetate, and propionate which exert anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory, and epigenetic effects. Butyrate acts as a histone deacetylase inhibitor, modulating gene expression, promoting apoptosis in cancer cells, and reinforcing epithelial barrier function [

141,

142,

143]. Through selective stimulation of beneficial taxa such as

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus, prebiotics contribute to a microbiota configuration associated with reduced cancer risk. Moreover, by influencing microbial β-glucuronidase activity and mucosal immune responses, prebiotics indirectly impact estrogen metabolism and immune surveillance [

45,

144]. Experimental models have shown that dietary prebiotics can modulate tumorigenesis, especially when consumed in the context of a high-fiber diet, although robust clinical evidence in breast cancer remains to be established [

145,

146,

147,

148].

Synbiotics, which combine both probiotics and prebiotics, are designed to leverage the complementary benefits of microbial supplementation and substrate support [

149,

150,

151,

152,

153]. This synergistic approach enhances colonization efficiency of probiotics, augments beneficial metabolite production, and stabilizes the microbial ecosystem. Synbiotics have demonstrated superior efficacy compared to individual biotics in modulating inflammatory markers, improving mucosal integrity, and restoring microbial diversity [

154,

155,

156,

157,

158,

159]. Clinical studies, particularly in gastrointestinal malignancies, suggest that synbiotics can reduce chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicity and systemic inflammation. Although specific evidence in breast cancer patients is limited, these findings suggest that synbiotics may offer therapeutic advantages by modulating host-microbe interactions implicated in breast carcinogenesis. For example, randomized trials involving synbiotics formulations combining

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG with inulin have shown reduced gut permeability and improved systemic inflammatory profiles effects that are mechanistically relevant to breast cancer [

160,

161,

162,

163,

164,

165].

Postbiotics represent a novel and increasingly recognized class of biotics, encompassing non-viable microbial cells, cellular components, and metabolites that confer biological activity in the host [

166,

167,

168,

169]. Unlike probiotics, postbiotics do not require microbial viability, offering advantages in terms of safety and self-stability. Key bioactive components include SCFAs (particularly butyrate), bacteriocins, lipoteichoic acids, and extracellular polysaccharides can directly influence host immune responses, modulate epithelial regeneration, and exert anti-proliferative effects on tumor cells [

170,

171,

172,

173,

174,

175]. Butyrate, for example, promotes apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines and regulates gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms [

176,

177,

178,

179]. Lipoteichoic acids and peptidoglycans derived from

Lactobacillus species have been shown to enhance mucosal immunity and protect against inflammation-driven tumorigenesis [

180]. Although the application of postbiotics in breast cancer remains in early stages, emerging studies suggest that they may potentiate the effects of immunotherapy, reduce cancer stem cell phenotypes, and serve as safe, standardized alternatives to live microbial administration.

Collectively, biotics represents a versatile toolkit for modulating the gut microbiota in ways that are increasingly understood to impact breast cancer biology. Through their influence on microbial composition, metabolite production, immune tone, and hormonal metabolism, biotics may alter the systemic milieu in a manner conducive to cancer prevention and improved treatment outcomes. The integration of biotic-based interventions into personalized medicine frameworks guided by microbial, metabolomic, and host-response profiling could unlock novel avenues for preventing and managing breast cancer. Future research must aim to elucidate strain-specific effects, define optimal dosing strategies, and validate clinical efficacy through rigorously designed mechanistic and interventional studies.

7. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence on Biotics in Breast Cancer

Recent advances in microbiome science have revealed that breast cancer (BC) is not merely a localized disease but may be intricately linked with systemic microbial ecology, particularly the gut microbiota. Biotics encompassing probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and next-generation microbial therapeutics offer a compelling frontier for modulating host immunity, metabolism, and estrogen regulation. In this section, we examine the current body of preclinical and clinical evidence for biotics in the context of breast cancer prevention and therapy, detailing molecular mechanisms, translational efforts, and safety considerations.

7.1. Preclinical Evidence: In Vivo and In Vitro Models

Preclinical studies have provided critical insights into the therapeutic potential of biotics: probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics in the context of breast cancer (BC). Using both in-vitro and in-vivo models, these investigations have elucidated key mechanisms by which gut microbial modulation may influence tumor biology, including immunomodulation, apoptosis induction, modulation of oncogenic signaling pathways, and alterations in microbial-derived metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). While these studies vary in microbial species, delivery methods, and tumor models, collectively they support a strong rationale for exploring biotic interventions as adjuncts in breast cancer prevention and treatment.

7.2. In Vitro Studies

In vitro models have been instrumental in uncovering direct anti-tumor effects of bacterial strains and their metabolites on breast cancer cell lines. Cell-free supernatants derived from probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG have demonstrated significant cytotoxicity against both estrogen receptor-positive (MCF-7) and triple-negative (MDA-MB-231) breast cancer cell lines, primarily through activation of caspase-dependent apoptosis and suppression of proliferation [

181]. These effects are frequently associated with alterations in the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic genes, including upregulation of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 and downregulation of Bcl-2 [

182].

Beyond whole organisms, bacterial metabolites such as SCFAs particularly butyrate, acetate, and propionate exert potent anti-cancer effects [

183]. Butyrate, for instance, functions as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, leading to epigenetic reprogramming of cancer cells and upregulation of tumor suppressor genes such as p21 and p53 [

184].

Propionibacterium freudenreichii-derived SCFAs induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells via both intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor-mediated) pathways, with involvement of caspase-8 and caspase-9 [

185]. These metabolites also interfere with cancer-associated signaling cascades, including the Wnt/β-catenin and MAPK pathways, contributing to reduced proliferation and increased apoptotic cell death [

186]. Moreover, postbiotic components such as bacteriocins, peptidoglycans, and exopolysaccharides have demonstrated immunostimulatory and cytostatic properties [

187]. Although mechanistic clarity remains incomplete, emerging evidence suggests that bacterial products can also modulate the expression of genes involved in cell cycle arrest and DNA repair, positioning them as promising non-viable alternatives to live biotherapeutics.

7.3. In Vivo Studies

Rodent models of breast cancer have corroborated the anti-tumor potential of biotics in vivo, offering crucial insights into host-microbiota-tumor interactions. In a seminal study by Lakritz

et al. (2014), oral administration of

Lactobacillus reuteri to MMTV-HER2/neu transgenic mice significantly suppressed spontaneous mammary tumorigenesis [

188]. This effect was mechanistically linked to systemic immune modulation, characterized by an increase in CD4

+CD25

+FoxP3

+ regulatory T cells and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α [

189]. These findings suggest that microbial reprogramming may enhance anti-tumor immunity while tempering chronic inflammation both hallmarks of tumor suppression [

190]. In another murine study demonstrated that

Lactobacillus plantarum effectively inhibited tumor growth in a breast cancer model [

191,

192]. Tumor-bearing mice treated with the probiotic exhibited reduced tumor volumes and downregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in tumor tissues [

193]. Concurrently, the probiotic intervention led to increased fecal abundance of SCFA-producing taxa, notably

Faecalibacterium and

Roseburia, indicating that microbial metabolic reprogramming contributes to systemic anti-tumor effects [

194]. Prebiotics have also shown promise in breast cancer models. In a DMBA-induced carcinogenesis model, rats supplemented with inulin exhibited decreased tumor incidence and multiplicity, likely mediated through enhanced colonic butyrate production and immune activation [

195]. Moreover, dietary fructooligosaccharides (FOS) reduced both primary tumor size and pulmonary metastases in a 4T1 mouse model [

196]. These effects correlated with increased SCFA levels, restoration of gut microbial diversity, and a shift in the cytokine milieu toward a Th1-dominant, anti-tumor phenotype, as evidenced by elevated IFN-γ and IL-12 expression in splenic lymphocytes [

25,

197]. Synbiotic formulations, combining probiotics and prebiotics, have shown synergistic benefits. Even administration of a synbiotic comprising

Bifidobacterium longum and inulin significantly attenuated tumor burden in 4T1-bearing mice [

198,

199]. The synbiotic regimen not only restored microbiota diversity and SCFA levels but also downregulated tumor angiogenesis and invasion markers, including VEGF and MMP-9 [

147,

200]. These results indicate that synbiotics can simultaneously enhance microbial stability and exert multi-level effects on tumor progression.

Emerging interest in postbiotics has added another dimension to preclinical strategies. Although in vivo studies in breast cancer remain limited, there is growing evidence that direct administration of SCFAs or microbially derived metabolites could recapitulate many of the benefits observed with live bacterial interventions, with potentially improved safety profiles [

201,

202,

203,

204,

205,

206,

207]. Butyrate supplementation in mouse models has demonstrated tumor suppressive effects through HDAC inhibition and immune cell modulation, while tryptophan-derived indole metabolites such as indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) have shown antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in other cancer contexts, warranting further exploration in breast cancer [

201]. Taken together, in vitro and in vivo studies underscore the multifaceted mechanisms by which biotics may modulate breast cancer risk and progression. These findings collectively establish a strong biological foundation for translational research, although they also highlight the complexity of host-microbiome-tumor interactions and the need for precise, context-specific interventions.

8. Clinical Studies: From Pilot Trials to Emerging Translational Evidence

Corroborating insights from preclinical animal models, an expanding body of human studies has substantiated the relevance of gut microbiota in breast cancer (BC) etiology and progression. Case-control analyses consistently report significant dysbiosis in breast cancer patients, marked by reduced microbial α-diversity (both richness and evenness), and a notable shift in taxonomic composition when compared to healthy controls [

179,

208,

209,

210,

211,

212,

213,

214,

215,

216,

217,

218,

219]. This diminished diversity reflects a less resilient and less functionally redundant gut ecosystem, potentially undermining host metabolic and immune homeostasis. Specifically, there is a recurring depletion of anti-inflammatory and metabolically beneficial taxa including

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii,

Bifidobacterium spp.,

Lactobacillus spp., and

Akkermansia muciniphila alongside an enrichment of potentially pathogenic or pro-inflammatory genera such as

Escherichia/Shigella,

Clostridium hathewayi, and various

Enterobacteriaceae [

220,

221,

222,

223,

224]. Beyond these cross-sectional associations, longitudinal cohort data are beginning to uncover temporal dynamics linking microbial profiles to breast cancer risk. For instance, microbiota-based analyses from the American Gut Project and the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program (BCERP) have demonstrated that certain microbial signatures may precede clinical diagnosis [

225,

226,

227]. Notably, fecal samples collected prior to diagnosis exhibited elevated abundances of

Collinsella,

Eggerthella, and

Clostridium spp. microorganisms with known roles in estrogen metabolism, oxidative stress, and inflammation [

228,

229]. These taxa are enriched in genes encoding β-glucuronidase and sulfotransferases, enzymes that deconjugate estrogens in the gut lumen, facilitating enterohepatic recirculation and potentially increasing systemic estrogen levels [

48,

230,

231]. This functional signature of the microbiota, often termed the

estrobolome, is particularly relevant for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer subtypes [

127,

232,

233,

234]. Metagenomic and metabolomic investigations further illuminate distinct functional attributes of the gut microbiome in breast cancer patients. Comparative analyses reveal that microbiota in these patients harbor enriched gene pathways involved in estrogen reactivation, bile acid metabolism, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis all of which are implicated in tumor-promoting systemic effects [

99,

226,

235,

236]. Elevated microbial β-glucuronidase activity has been detected in fecal metatranscriptomes of postmenopausal breast cancer patients [

232], correlating with higher systemic levels of free estrogens. Moreover, increased microbial production of secondary bile acids (e.g., deoxycholic acid), indole derivatives, and phenolic compounds has been reported in serum and fecal metabolomic profiles of breast cancer cohorts [

237,

238]. These metabolites interact with host nuclear receptors such as the estrogen receptor (ER), aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), and farnesoid X receptor (FXR), modulating cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and immune response in ways conducive to tumor growth.

The impact of gut microbiota on systemic hormone regulation is especially pronounced in postmenopausal women, in whom endogenous estrogen production shifts primarily to peripheral sources. In this demographic, alterations in the estrobolome may exert outsized effects. For example, higher β-glucuronidase activity observed in the gut microbiota of postmenopausal breast cancer patients has been associated with elevated circulating estradiol levels, suggesting a microbiota-mediated mechanism of hormonal dysregulation [

45,

114,

144]. Such findings point to a bidirectional crosstalk between microbial and endocrine axes, with implications for both disease prediction and intervention. Despite robust observational data linking dysbiosis with breast cancer risk, interventional studies evaluating the therapeutic modulation of the microbiota in clinical breast cancer settings remain limited, though recent trials offer encouraging findings. In a pilot randomized controlled trial, Zaharuddin

et al. (2022) assessed the effects of a multispecies probiotic formulation (comprising

Lactobacillus acidophilus,

Bifidobacterium bifidum, and

Streptococcus thermophilus) in early-stage breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy [

239,

240,

241]. Over the intervention period, probiotic administration led to improved gut microbial diversity, attenuation of gastrointestinal side effects, and increased peripheral natural killer (NK) cell activity suggesting an immunostimulatory role for microbial support during cytotoxic therapy [

241,

242,

243]. Similarly, Toi

et al. (2021) evaluated the effects of

Lactobacillus casei Shirota (Yakult) in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant therapy [

244]. The probiotic intervention was associated with reduced systemic inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), and a significantly lower incidence of neutropenia highlighting a potential role for probiotics in mitigating treatment-associated immunosuppression and inflammation [

245,

246,

247]. In addition to probiotic supplementation, observational evidence implicates diet-induced modulation of the microbiome as a relevant factor in breast cancer risk. A landmark analysis from the Nurses’ Health Study II demonstrated that high dietary fiber intake during adolescence and early adulthood was inversely associated with breast cancer risk later in life [

248]. The proposed mechanism centers on fiber’s capacity to support SCFA-producing taxa and reduce estrogen reabsorption through modulation of β-glucuronidase activity.

A follow-up clinical intervention explored the effects of a plant-based, high-fiber diet in breast cancer survivors [

245,

249]. Participants experienced significant increases in the relative abundance of

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and

Akkermansia muciniphila, along with improvements in urinary estrogen metabolite ratios (i.e., increased 2-OHE1:16α-OHE1), suggesting enhanced estrogen detoxification capacity and favorable shifts in host-microbiota interactions [

144,

249,

250]. Extending beyond probiotics and diet, recent trials have explored the impact of synbiotic formulations. A double-blind randomized controlled trial by Khazaei

et al. (2023) investigated the effects of a multiple species of

Lactobacillus in postmenopausal breast cancer patients over a 12-week intervention [

251]. The synbiotic group exhibited significant improvements in microbial diversity and butyrate production, as well as enhanced patient-reported outcomes such as reduced fatigue and improved quality of life. Although oncologic endpoints (e.g., tumor progression or recurrence) were not directly assessed, the observed immune-metabolic benefits underscore the potential for synbiotics as supportive interventions during survivorship and therapy [

251]. Currently, no clinical trials have evaluated the direct administration of postbiotics defined as non-viable microbial products or metabolic by products in breast cancer treatment. However, observational studies suggest that reduced levels of SCFAs, particularly butyrate and propionate, are characteristic of the breast cancer microbiome [

208,

252]. A prospective study further demonstrated that fecal microbiota signatures predictive of butyrate production correlated inversely with systemic inflammation and circulating hormone levels associated with oncogenesis [

21,

126,

253]. These data implicate postbiotic restoration whether through diet, probiotics, or direct supplementation as a promising but underexplored therapeutic avenue. Collectively, these findings delineate a multifaceted interplay between gut microbiota composition, metabolic function, host hormonal status, and breast cancer risk and progression. The convergence of taxonomic, functional, and metabolic disruptions in the breast cancer microbiome underscores the necessity of integrative, multi-omics approaches in future clinical research. Longitudinal and interventional studies targeting the microbiota represent a compelling frontier in breast cancer prevention, prognosis, and therapy.

9. Safety, Efficacy, and Clinical Translation

The safety of biotics, especially probiotics, in immuno-compromised individuals remains a key concern. While generally recognized as safe (GRAS), probiotics can pose rare risks of bacteremia, sepsis, or fungemia in critically ill or neutropenic patients [

254]. Hence, clinical deployment necessitates rigorous safety screening, strain-level characterization, and patient stratification. Prebiotics and postbiotics present fewer safety concerns due to the absence of live organisms, although high intake may lead to bloating, gas, or osmotic diarrhea [

255,

256,

257]. Importantly, postbiotics such as SCFAs and bacteriocins may allow therapeutic benefit without the risks associated with live microbes [

256,

258,

259]. Clinical efficacy of biotics is highly variable and influenced by individual microbiome composition, genetic background, and treatment history. Stratified or personalized approaches potentially informed by baseline microbiota profiling and machine learning algorithms are likely required to identify responders.

The timing and context of biotic administration also matter. Some preclinical studies suggest that probiotics may enhance chemotherapeutic efficacy (e.g., paclitaxel, doxorubicin), while others caution against possible interference with drug metabolism [

260,

261,

262,

263]. A nuanced understanding of host-drug-microbe interactions is essential for optimized biotic deployment. The translation of biotics into clinical practice is hampered by regulatory ambiguities. Most probiotics and prebiotics are classified as food supplements rather than therapeutics, resulting in a lack of standardized dosing, strain documentation, and clinical endpoints. Regulatory frameworks must evolve to accommodate next-generation biotics and microbiome-modifying agents, potentially under new classifications such as “live biotherapeutic products” (LBPs).

10. Challenges, Future Directions and Conclusions

An expanding body of evidence supports a complex, bidirectional interplay between the gut microbiota and breast cancer, mediated through a nexus of endocrine, immune, and metabolic pathways. Gut microbial dysbiosis is a state of altered microbial composition and function emerges as a critical factor influencing breast carcinogenesis. This influence is exerted via modulation of systemic estrogen levels through the estrobolome, disruption of mucosal and systemic immune homeostasis, and the generation of bioactive microbial metabolites, including SCFAs, secondary bile acids, and LPS, which collectively shape a pro- or anti-tumorigenic microenvironment. The gut microbiota, as a dynamic regulator of host physiology, plays a central role in modulating systemic immunity, endocrine signaling, and metabolic regulation. In the context of breast cancer, a heterogeneous and multifactorial disease, recent integrative studies have begun to unravel how perturbations in the gut microbial ecosystem may contribute to disease initiation, progression, and therapeutic response. This paradigm shift underscores the microbiota not merely as a passive bystander but as an active participant in breast cancer biology, capable of influencing the host’s immune-endocrine axis and, potentially, tumor microenvironment.

Mounting preclinical, clinical, and molecular evidence converges on the notion that gut microbial imbalances are implicated in breast cancer pathogenesis. Specifically, alterations in estrobolome activity, chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, and dysregulated microbial metabolite profiles appear to orchestrate a biologically permissive milieu for tumorigenesis. Furthermore, the identification of breast cancer-associated microbial signatures opens promising avenues for the development of microbiome-informed diagnostics, prognostics, and therapeutic strategies. Despite these advances, several limitations constrain the translational potential of current findings. Most human studies remain cross-sectional or observational in nature, often confounded by dietary, genetic, and environmental heterogeneity. Sample sizes are frequently small, and longitudinal data are scarce, hindering causal inference. Moreover, methodological inconsistencies in microbiome sampling, sequencing protocols, and data analysis pipelines impede reproducibility and cross-study comparisons. Addressing these limitations is critical to validate microbial biomarkers and realize the clinical potential of microbiota-targeted interventions.

To advance the field, future research should prioritize:

Large-scale, longitudinal cohort studies that integrate gut microbiome profiling with host multi-omics data (e.g., metabolomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics) to capture temporal dynamics and context-specific host-microbe interactions.

Randomized interventional trials assessing the efficacy of microbiota-modulating strategies such as dietary interventions, probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in altering breast cancer risk, progression, and treatment outcomes.

Mechanistic investigations using in vitro systems and gnotobiotic models to delineate the causal roles of specific microbial taxa and their metabolites in breast tumorigenesis and immune modulation.

In summary, the gut microbiota represents a malleable and clinically actionable component of breast cancer pathophysiology. As research continues to elucidate its mechanistic underpinnings, microbial signatures hold the potential to revolutionize breast cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Ultimately, the integration of microbiome science into precision oncology frameworks could pave the way for novel, microbiota-informed strategies that bridge the gap between gut health and cancer biology.

Author Contributions

P.M, S.G, A.P, So.S, A.G performed the literature search and written the manuscript. S.P.M, Sw.S prepared the figures. P.M, S.P.M, S.S.C had the idea for the article. A.S, J.B, Sw.S, S.S.C, S.P.M reviewed and revised the manuscript text critically for important intellectual content.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed in the present study.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the library and information services staff for their valuable assistance with literature searches and access to scientific resources. We also extend our sincere appreciation to colleagues whose insightful feedback helped refine the manuscript during its early drafting stages, and we thank Grammarly for supporting English language editing.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest regarding the content of this review article.

References

- Sung, H., et al., Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021. 71(3): p. 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Admoun, C. and H.N. Mayrovitz, The Etiology of Breast Cancer, in Breast Cancer, H.N. Mayrovitz, Editor. 2022, Exon Publications. Copyright: The Authors.; The author confirms that the materials included in this chapter do not violate copyright laws. Where relevant, appropriate permissions have been obtained from the original copyright holder(s), and all original sources have been appropriately acknowledged or referenced.: Brisbane (AU).

- Xu, H. and B. Xu, Breast cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors and screening. Chin J Cancer Res, 2023. 35(6): p. 565-583. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X., et al., Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2025. 10(1): p. 49.

- Dorling, L., et al., Breast Cancer Risk Genes - Association Analysis in More than 113,000 Women. N Engl J Med, 2021. 384(5): p. 428-439.

- Gilbert, J.A., et al., Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat Med, 2018. 24(4): p. 392-400. [CrossRef]

- Schoultz, I., et al., Gut microbiota development across the lifespan: Disease links and health-promoting interventions. J Intern Med, 2025. 297(6): p. 560-583. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y., et al., Gut Microbiota and Immune System Interactions. Microorganisms, 2020. 8(10). [CrossRef]

- Trosvik, P. and E.J. de Muinck, Ecology of bacteria in the human gastrointestinal tract--identification of keystone and foundation taxa. Microbiome, 2015. 3: p. 44.

- Goodman, B. and H. Gardner, The microbiome and cancer. J Pathol, 2018. 244(5): p. 667-676.

- El Tekle, G. and W.S. Garrett, Bacteria in cancer initiation, promotion and progression. Nat Rev Cancer, 2023. 23(9): p. 600-618. [CrossRef]

- Hou, K., et al., Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2022. 7(1): p. 135.

- Kim, C.H., Complex regulatory effects of gut microbial short-chain fatty acids on immune tolerance and autoimmunity. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 2023. 20(4): p. 341-350. [CrossRef]

- Koh, A., et al., From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell, 2016. 165(6): p. 1332-1345. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D., T. Liwinski, and E. Elinav, Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Research, 2020. 30(6): p. 492-506. [CrossRef]

- Ervin, S.M., et al., Gut microbial β-glucuronidases reactivate estrogens as components of the estrobolome that reactivate estrogens. J Biol Chem, 2019. 294(49): p. 18586-18599. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, X.C., et al., Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biology, 2012. 13(9): p. R79. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.A., et al., The effects of prebiotics on gastrointestinal side effects of metformin in youth: A pilot randomized control trial in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2023. 14: p. 1125187. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., et al., Probiotics and prebiotics for the amelioration of type 1 diabetes: present and future perspectives. Microorganisms, 2019. 7(3): p. 67. [CrossRef]

- Vich Vila, A., et al., Faecal metabolome and its determinants in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut, 2023. 72(8): p. 1472-1485. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., et al., Gut microbiota as a new target for anticancer therapy: from mechanism to means of regulation. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 2025. 11(1): p. 43. [CrossRef]

- Nshanian, M., et al., Short-chain fatty acid metabolites propionate and butyrate are unique epigenetic regulatory elements linking diet, metabolism and gene expression. Nat Metab, 2025. 7(1): p. 196-211. [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M., et al., Association of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Gut Microbiome With Clinical Response to Treatment With Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab in Patients With Solid Cancer Tumors. JAMA Netw Open, 2020. 3(4): p. e202895. [CrossRef]

- Arnone, A.A., et al., Gut microbiota interact with breast cancer therapeutics to modulate efficacy. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 2025. 17(2): p. 219-234. [CrossRef]

- Farhadi Rad, H., et al., Microbiota and Cytokine Modulation: Innovations in Enhancing Anticancer Immunity and Personalized Cancer Therapies. Biomedicines, 2024. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Causal effect of gut microbiota on the risk of cancer and potential mediation by inflammatory proteins. World Journal of Surgical Oncology, 2025. 23(1): p. 163. [CrossRef]

- Mariat, D., et al., The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol, 2009. 9: p. 123.

- Ma, Z., et al., A systematic framework for understanding the microbiome in human health and disease: from basic principles to clinical translation. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2024. 9(1): p. 237. [CrossRef]

- Effendi, R., et al., Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in Immune-Related Diseases. Microorganisms, 2022. 10(12). [CrossRef]

- Moon, J., et al., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii alleviates inflammatory arthritis and regulates IL-17 production, short chain fatty acids, and the intestinal microbial flora in experimental mouse model for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther, 2023. 25(1): p. 130. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-B., et al., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Attenuates CKD via Butyrate-Renal GPR43 Axis. Circulation Research, 2022. 131(9): p. e120-e134. [CrossRef]

- Ley, R.E., D.A. Peterson, and J.I. Gordon, Ecological and Evolutionary Forces Shaping Microbial Diversity in the Human Intestine. Cell, 2006. 124(4): p. 837-848. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.P., et al., Abnormalities in microbiota/butyrate/FFAR3 signaling in aging gut impair brain function. JCI Insight, 2024. 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., et al., Butyrate acts as a positive allosteric modulator of the 5-HT transporter to decrease availability of 5-HT in the ileum. Br J Pharmacol, 2024. 181(11): p. 1654-1670. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.P., et al., Free Fatty Acid Receptors 2 and 3 as Microbial Metabolite Sensors to Shape Host Health: Pharmacophysiological View. Biomedicines, 2020. 8(6): p. 154. [CrossRef]

- Grant, E.T., et al., Dietary fibers boost gut microbiota-produced B vitamin pool and alter host immune landscape. Microbiome, 2024. 12(1): p. 179. [CrossRef]

- Rowland, I., et al., Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur J Nutr, 2018. 57(1): p. 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H., et al., Age-associated changes in innate and adaptive immunity: role of the gut microbiota. Front Immunol, 2024. 15: p. 1421062. [CrossRef]

- Spindler, M.P., et al., Human gut microbiota stimulate defined innate immune responses that vary from phylum to strain. Cell Host Microbe, 2022. 30(10): p. 1481-1498.e5. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., et al., Interactions between toll-like receptors signaling pathway and gut microbiota in host homeostasis. Immun Inflamm Dis, 2024. 12(7): p. e1356. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.M., et al., The Influence of the Gut Microbiome on Host Metabolism Through the Regulation of Gut Hormone Release. Front Physiol, 2019. 10: p. 428. [CrossRef]

- Jyoti and P. Dey, Mechanisms and implications of the gut microbial modulation of intestinal metabolic processes. npj Metabolic Health and Disease, 2025. 3(1): p. 24. [CrossRef]

- Luo, R., et al., An examination of the LPS-TLR4 immune response through the analysis of molecular structures and protein–protein interactions. Cell Communication and Signaling, 2025. 23(1): p. 142. [CrossRef]

- Chabi, K. and L. Sleno, Estradiol, Estrone and Ethinyl Estradiol Metabolism Studied by High Resolution LC-MS/MS Using Stable Isotope Labeling and Trapping of Reactive Metabolites. Metabolites, 2022. 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., et al., Gut microbial beta-glucuronidase: a vital regulator in female estrogen metabolism. Gut Microbes, 2023. 15(1): p. 2236749. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.B., et al., Gut microbial β-glucuronidases influence endobiotic homeostasis and are modulated by diverse therapeutics. Cell Host Microbe, 2024. 32(6): p. 925-944.e10. [CrossRef]

- Fuhrman, B.J., et al., Associations of the fecal microbiome with urinary estrogens and estrogen metabolites in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2014. 99(12): p. 4632-40. [CrossRef]

- Larnder, A.H., A.R. Manges, and R.A. Murphy, The estrobolome: Estrogen-metabolizing pathways of the gut microbiome and their relation to breast cancer. Int J Cancer, 2025. 157(4): p. 599-613. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., et al., Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Pathogenesis, Diseases, Prevention, and Therapy. MedComm (2020), 2025. 6(5): p. e70168. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., et al., Exploring and evaluating microbiome resilience in the gut. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 2025. 101(5). [CrossRef]

- David, L.A., et al., Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature, 2014. 505(7484): p. 559-63. [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.M., L. Al-Nakkash, and M.M. Herbst-Kralovetz, Estrogen-gut microbiome axis: Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas, 2017. 103: p. 45-53. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, K., et al., The Impact of Environmental Chemicals on the Gut Microbiome. Toxicol Sci, 2020. 176(2): p. 253-284. [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E., Stress in the microbiome-immune crosstalk. Gut Microbes, 2024. 16(1): p. 2327409. [CrossRef]

- Anand, N., V.R. Gorantla, and S.B. Chidambaram, The Role of Gut Dysbiosis in the Pathophysiology of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Cells, 2022. 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., et al., Tumor initiation and early tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and interventional targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2024. 9(1): p. 149.

- Lin, N.Y.-T., et al., Microbiota-driven antitumour immunity mediated by dendritic cell migration. Nature, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.A., et al., Menopause Is Associated with an Altered Gut Microbiome and Estrobolome, with Implications for Adverse Cardiometabolic Risk in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. mSystems, 2022. 7(3): p. e0027322. [CrossRef]

- Tao, J., et al., Role of intestinal testosterone-degrading bacteria and 3/17β-HSD in the pathogenesis of testosterone deficiency-induced hyperlipidemia in males. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 2024. 10(1): p. 123. [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.-N., et al., Clostridium scindens metabolites trigger prostate cancer progression through androgen receptor signaling. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, 2023. 56(2): p. 246-256. [CrossRef]

- McCurry, M.D., et al., Gut bacteria convert glucocorticoids into progestins in the presence of hydrogen gas. Cell, 2024. 187(12): p. 2952-2968.e13. [CrossRef]