Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Personalized Learning

1.2. Text Personalization Evaluation Using Natural Language Processing

1.3. Current Research

2. Materials and Method

2.1. LLM Selection and Implementation Details

2.2. Text Corpus

2.3. Descriptions of Reader Profiles

2.4. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Main Effect of Reader Profile on Variations in Linguistic Features of Modified Texts

3.2. Main Effect of LLMs

3.3. Main Effect of Text Types

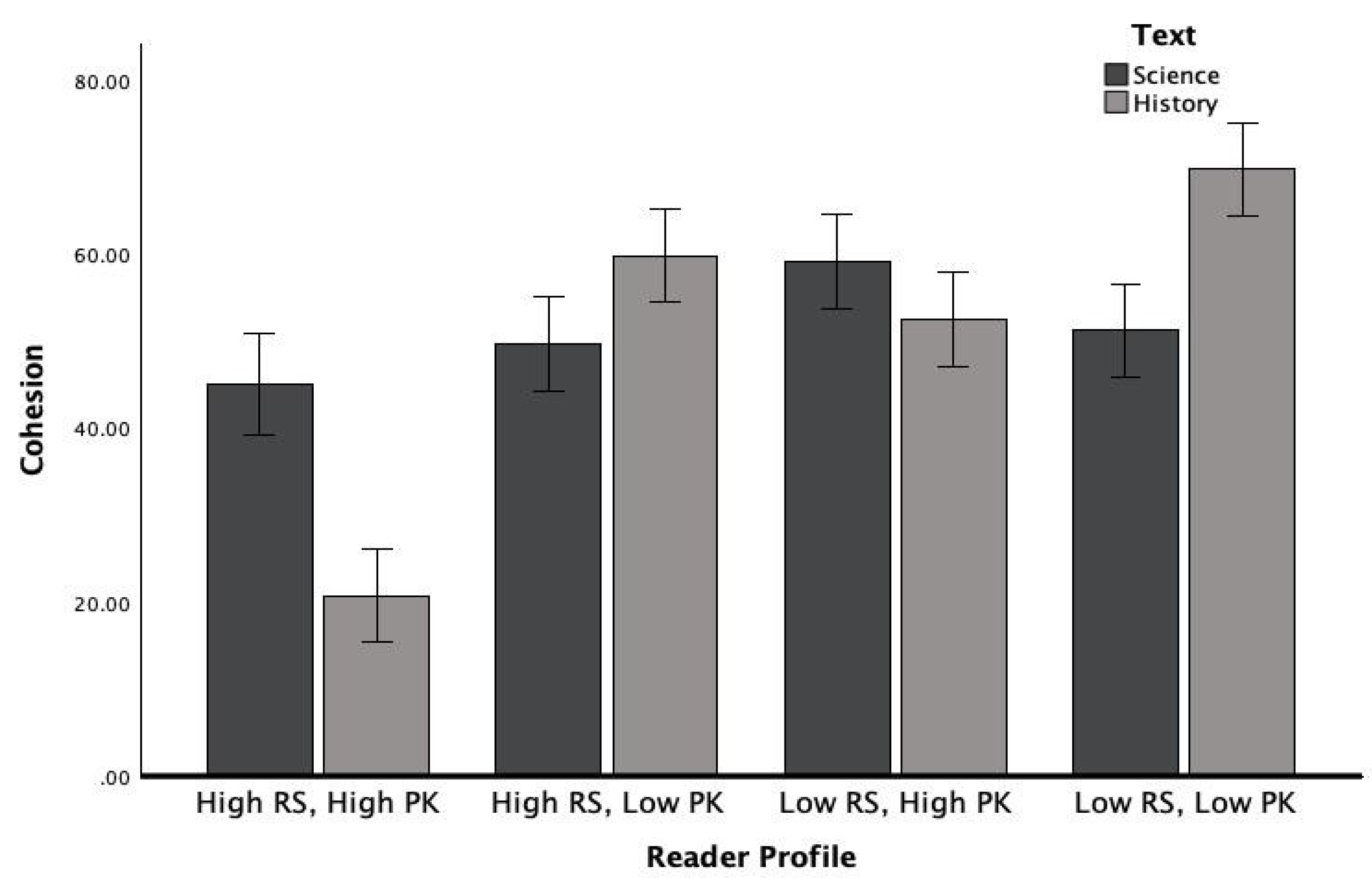

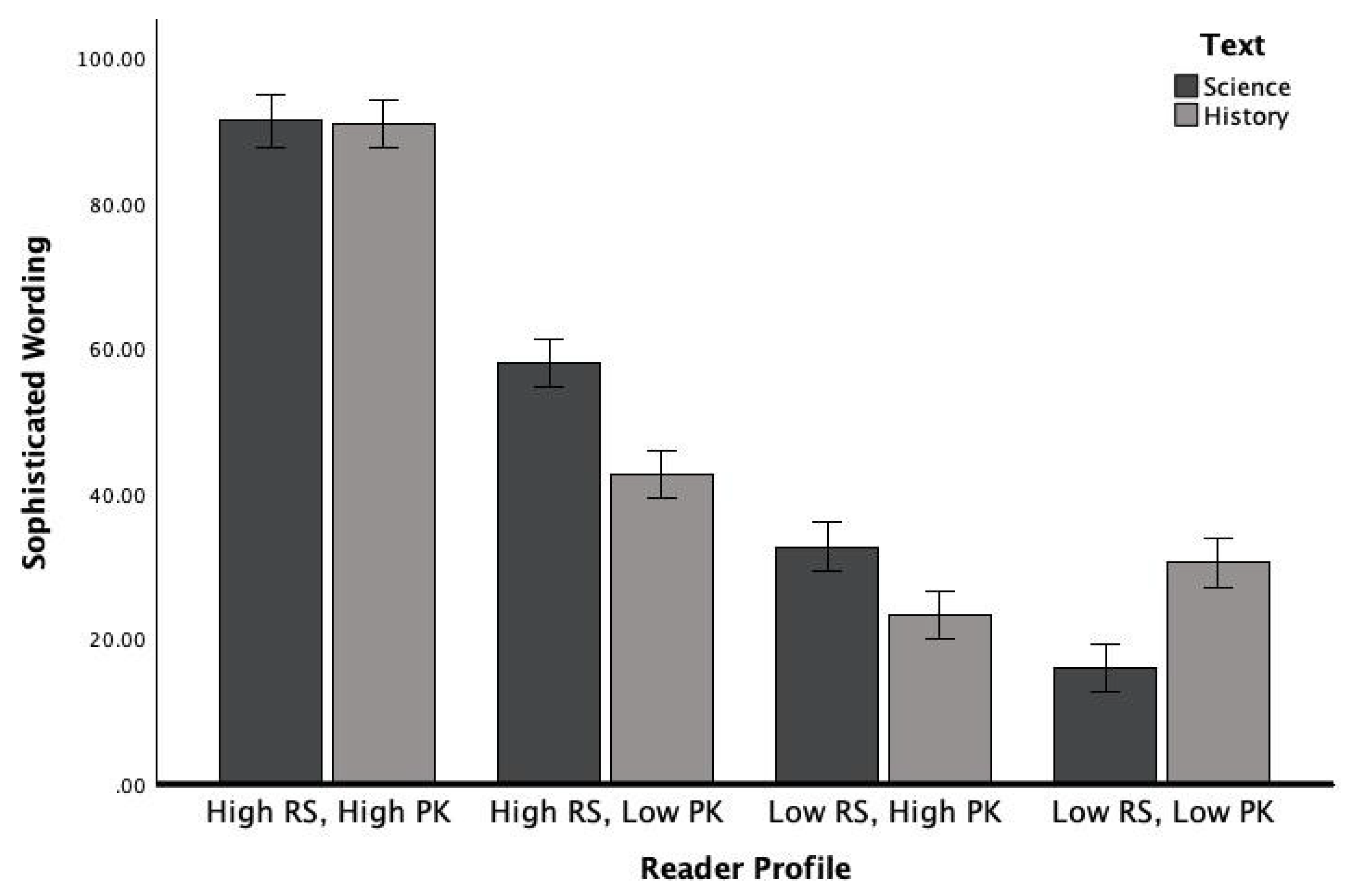

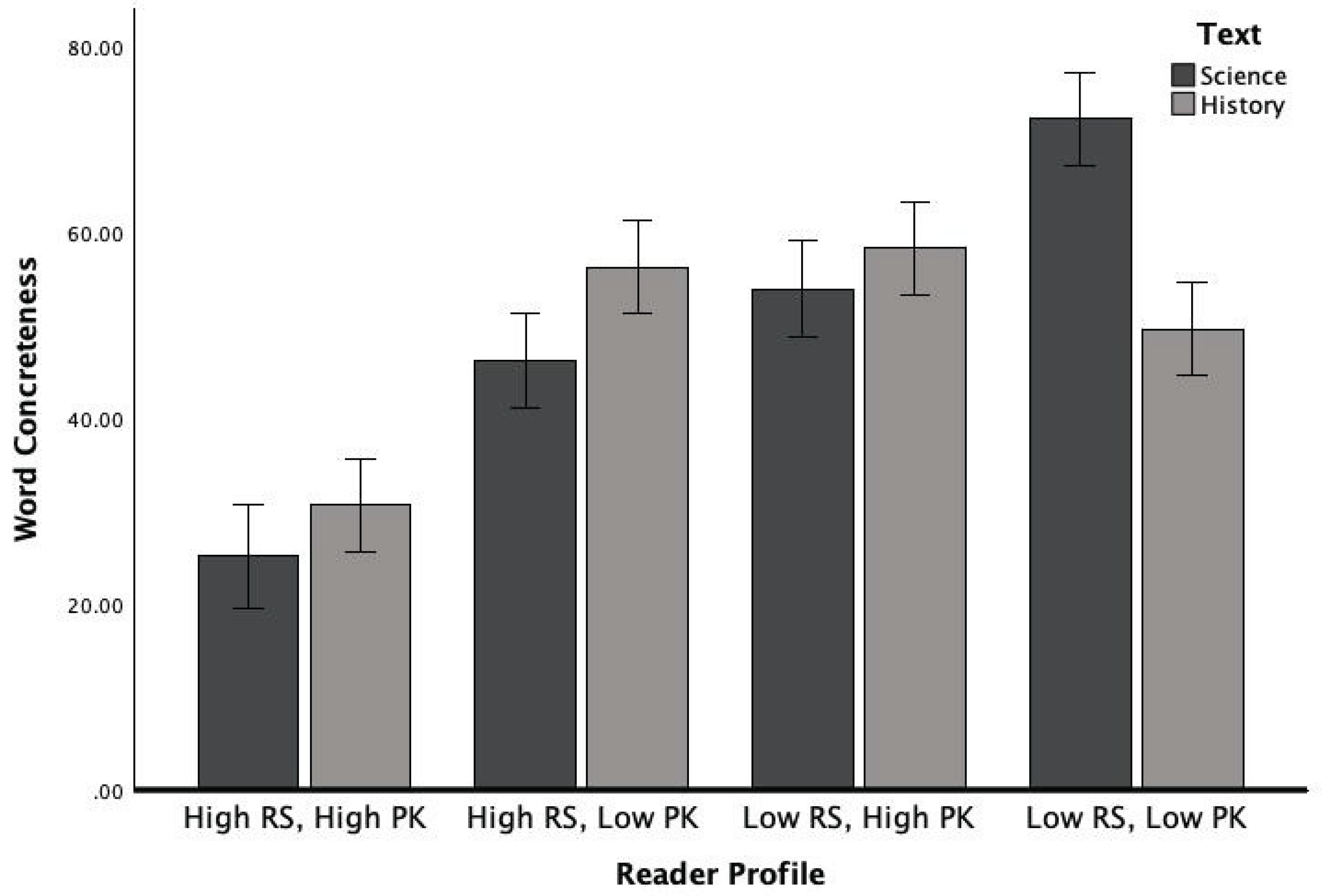

3.4. Interaction Effect Reader x Text Genre

4. Discussion

4.1. Texts Adapted for Different Reader Profiles

4.2. LLMs Generated Outputs with Unique Linguistic Patterns

4.3. Linguistic Differences of Adapted Texts from Science Versus History Domain

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

Funding

Abbreviations

| PK | Prior knowledge |

| RS | Reading skills |

| GenAI | Generative AI |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| AFS | Adaptive Feedback System |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| iSTART | Interactive Strategy Training for Active Reading and Thinking |

| FKGL | Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level |

| WAT | Writing Analytics Tool |

Appendix A. LLM Descriptions

- Version Used: Claude 3.5;

- Date Accessed: 10 June 2025;

- Accessed via https://poe.com web deployment, default configurations were used;

- Training Size: Claude is trained on a large-scale, diverse dataset derived from a broad range of online and curated sources. The exact size of the training data remains proprietary;

- Number of Parameters: The exact number is not disclosed by Anthropic, but it is estimated to be between 70–100 billion parameters.

- Version Used: Llama 3.1;

- Date Accessed: 10 June 2025;

- Accessed via https://poe.com web deployment, default configurations were used;

- Llama 3.1 was trained on 2 trillion tokens sourced from publicly available datasets, including books, websites, and other digital content;

- Number of Parameters: 70 billion parameters.

- Version Used: Gemini Pro 1.5;

- Date Accessed: 10 June 2025;

- Accessed via https://poe.com web deployment, default configurations were used;

- Training Size: Gemini is trained on 1.5 trillion tokens, sourced from a wide variety of publicly available and curated data, including text from books, websites, and other large corpora;

- Number of Parameters: 100 billion parameters.

- Version Used: GPT-4o;

- Date Accessed: 10 June 2025;

- Accessed via https://poe.com web deployment, default configurations were used;

- Training Size: GPT-4 was trained on an estimated 1.8 trillion tokens from diverse sources, including books, web pages, academic papers, and large text corpora;

- Number of Parameters: The exact number is not publicly disclosed but is in the range of 175 billion parameters.

Appendix B. Reader Profile Descriptions

| Descriptions of High and Low Knowledge Reader in Science | Descriptions of High and Low Knowledge Reader in History | |

| Reader 1 (High RS/High PK*) |

Age: 25 Educational level: Senior Major: Chemistry (Pre-med) ACT English composite score: 32/36 (performance is in the 96th percentile) ACT Reading composite score: 32/36 (performance is in the 96th percentile) ACT Math composite score: 28/36 (performance is in the 89th percentile) ACT Science composite score: 30/36 (performance is in the 94th percentile) Science background: Completed eight required biology, physics, and chemistry college-level courses (comprehensive academic background in the sciences, covering advanced topics in biology, chemistry, and physics, well-prepared for higher-level scientific learning and analysis) Reading goal: Understand scientific concepts and principles |

Age: 25 Educational level: Senior Major: History and Archeology ACT English: 32/36 (96th percentile) ACT Reading: 33/36 (97th percentile) AP History score: 5 out of 5 History background: Completed 4 years of college-level courses in U.S. and World History (extensive training in historical analysis, primary source evaluation, and historiography) Reading goal: Understand key historical events and their relevance to society |

| Reader 2 (High RS/Low PK*) |

Age: 20 Educational level: Sophomore Major: Psychology ACT English composite score: 32/36 (performance is in the 96th percentile) ACT Reading composite score: 31/36 (performance is in the 94th percentile) ACT Math composite score: 18/36 (performance is in the 42th percentile) ACT Science composite score: 19/36 (performance is in the 46th percentile) Science background: Completed one high-school-level chemistry course (no advanced science course). Limited exposure and understanding of scientific concepts Interests/Favorite subjects: arts, literature Reading goal: Understand scientific concepts and principles |

Age: 21 Educational level: Junior Major: Biology ACT English: 32/36 (96th percentile) ACT Reading: 31/36 (94th percentile) AP History score: 2 out of 5 History background: Completed general education high school history; no college-level history courses. Limited interest and knowledge of historical events Interests/Favorite subjects: arts, literature Reading goal: Understand key historical events and their relevance to society |

| Reader 3 (Low RS/High PK*) |

Age: 20 Educational level: Sophomore Major: Health Science ACT English composite score: 19/36 (performance is in the 44th percentile) ACT Reading composite score: 20/36 (performance is in the 47th percentile) ACT Math composite score: 32/36 (performance is in the 97th percentile) ACT Science composite score: 30/36 (performance is in the 94th percentile) Science background: Completed one physics, one astronomy, and two college-level biology courses (substantial prior knowledge in science, having completed multiple college-level courses across several disciplines, strong foundation in scientific principles and concepts) Reading goal: Understand scientific concepts Reading disability: Dyslexia |

Age: 22 Educational level: Junior Major: History ACT English: 19/36 (44th percentile) ACT Reading: 20/36 (47th percentile) AP History score: 5 out of 5 History background: Completed 3 years of college-level history courses (specializing in U.S. history and early modern Europe) Reading goal: Understand key historical events and their relevance to society Reading disability: Dyslexia |

| Reader 4 (Low RS/Low PK*) |

Age: 18 Educational level: Freshman Major: Marketing ACT English composite score: 17/36 (performance is in the 33rd percentile) ACT Reading composite score: 18/36 (performance is in the 36th percentile) ACT Math composite score: 19/36 (performance is in the 48th percentile) ACT Science composite score: 17/36 (performance is in the 34th percentile) Science background: Completed one high-school-level biology course (no advanced science course) Limited exposure and understanding of scientific concepts Reading goal: Understand scientific concepts |

Age: 18 Educational level: Freshman Major: Finance ACT English: 18/36 (35th percentile) ACT Reading: 17/36 (32nd percentile) AP History: 1 out of 5 History background: Only completed basic U.S. History in high school; little engagement or interest in history topics Reading goal: Understand key historical events and their relevance to society |

Appendix C. Prompt Used

| Components | Augmented Prompt |

| Personification | Imagine you are a cognitive scientist specializing in reading comprehension and learning science |

| Task objectives |

|

| Chain-of-thought | Explain the rationale behind each modification approach and how each change helps the reader grasp the scientific concepts and retain information |

| RAG | Refer to the attached pdf files. Apply these empirical findings and theoretical frameworks from these files as guidelines to tailor text

|

| Reader profile | [Insert Reader Profile Description from Appendix B] |

| Text input | [Insert Text] |

References

- Lee, J.S. InstructPatentGPT: Training patent language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Artif. Intell. Law 2024, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, A.; Peng, K.C.; Lohit, S.; Matthiesen, J.; Smith, K.; Tenenbaum, J. Evaluating large vision-and-language models on children’s mathematical olympiads. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 15779–15800. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Hu, X.; Xiao, C.; Bai, J.; Barandouzi, Z.A.; Lee, S.; Lin, Y. Evaluation of large language models in tailoring educational content for cancer survivors and their caregivers: Quality analysis. JMIR Cancer 2025, 11, e67914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Stolzenburg, F. Commonsense reasoning and explainable artificial intelligence using large language models. In Proc. Eur. Conf. Artif. Intell.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 302–319. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-Y. ROUGE: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text Summarization Branches Out: Proc. ACL-04 Workshop; Assoc. Comput. Linguist.: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Porfirio, D.; Wang, X.J.; Zhao, K.; Mutlu, B. VeriPlan: Integrating formal verification and LLMs into end-user planning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.17898. [Google Scholar]

- Pesovski, I.; Santos, R.; Henriques, R.; Trajkovik, V. Generative AI for customizable learning experiences. Sustainability. 2024, 16, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laak, K.-J.; Aru, J. AI and personalized learning: Bridging the gap with modern educational goals. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.02798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Kwon, S.; Kim, K. Empowering personalized learning through a conversation-based tutoring system with student modeling. In Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conf. on Human Factors in Comput. Syst.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Liang, J.; Sierra, C.; Luckin, R.; Tong, R.; Liu, Z.; Cui, P.; Tang, J. AI for education (AI4EDU): Advancing personalized education with LLM and adaptive learning. In Proc. 30th ACM SIGKDD Conf. on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 6743–6744. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, J.F.; Steiner, E.D.; Baird, M.D.; Hamilton, L.S.; Pane, J.D. Informing Progress: Insights on Personalized Learning Implementation and Effects; Res. Rep. RR-2042-BMGF; Rand Corp.: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2017.Pane, J.F.; Steiner, E.D.; Baird, M.D.; Hamilton, L.S.; Pane, J.D. Informing progress: Insights on personalized learning implementation and effects. Rand Corp. Res. Rep. 2017.

- Bernacki, M.L.; Greene, M.J.; Lobczowski, N.G. A systematic review of research on personalized learning: Personalized by whom, to what, how, and for what purpose(s)? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 1675–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, K.S.; Dhatterwal, J.S.; Ojha, R.P. AI in personalized learning. In Advances in Technological Innovations in Higher Education; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, M.J.K.O. Personalized learning through AI. Adv. Eng. Innov. 2023, 5, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, M.P.; Sampelolo, R.; Lura, H. Revolutionizing education: Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence for personalized learning. Klasikal: J. Educ. Lang. Teach. Sci. 2023, 5, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Moreno, L.; Ramos, A. Exploring large language models to generate easy-to-read content. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 6, 1394705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuru, Y.; Dempsey, K.; McNamara, D.S. Prior knowledge, reading skill, and text cohesion in the comprehension of science texts. Learn. Instr. 2009, 19, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; … Amodei, D. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Hardaker, G.; Glenn, L.E. Artificial intelligence for personalized learning: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2025, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Mishra, S.; Liu, A.; Su, S.Y.; Chen, J.; Kulkarni, C.; … Chi, E. Beyond chatbots: ExploreLLM for structured thoughts and personalized model responses. In Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C.; Fung, Y. Educational personalized learning path planning with large language models. arXiv Preprint 2024, arXiv:2407.11773. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, M.; Cai, N.; Lei, V.N.L. Personal learning environments and personalized learning in the education field: Challenges and future trends. In Applied Degree Education and the Shape of Things to Come; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 231–247. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Mittal, P.; Kumar, M.; Bhardwaj, V. The role of large language models in personalized learning: A systematic review of educational impact. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Wang, Y.; Chung, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating the effectiveness of LLMs in introductory computer science education: A semester-long field study. In Proc. 11th ACM Conf. on Learning@Scale; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Létourneau, A.; Deslandes Martineau, M.; Charland, P.; Karran, J.A.; Boasen, J.; Léger, P.M. A systematic review of AI-driven intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) in K–12 education. npj Sci. Learn. 2025, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Hou, X.; Ye, R.; Kazemitabaar, M.; Diana, N.; Liut, M.; Stamper, J. Improving student–AI interaction through pedagogical prompting: An example in computer science education. arXiv Preprint 2025, arXiv:2506.19107. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar, Ó.; Contero, M.; Hincapié, M. Personalized and timely feedback in online education: Enhancing learning with deep learning and large language models. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Liang, J.; Tang, J.; … Wen, Q. Large language models for education: A survey and outlook. arXiv Preprint 2024, arXiv:2403.18105. [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Campos, C. The impact of artificial intelligence on personalized learning in higher education: A systematic review. Trends High. Educ. 2025, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Sha, L.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Martinez-Maldonado, R.; Chen, G.; … Gašević, D. Practical and ethical challenges of large language models in education: A systematic scoping review. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, L.J.; Weber, K.E. The promises and pitfalls of large language models as feedback providers: A study of prompt engineering and the quality of AI-driven feedback. AI 2025, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, M.; Ahmed, Y.; Shamsi, J.A.; Sherwani, F.; Usman, M. AI-based personalized e-learning systems: Issues, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 81323–81342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. BERTScore: Evaluating text generation with BERT. In Proc. Int. Conf. on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2020.

- Basham, J.D.; Hall, T.E.; Carter, R.A. Jr.; Stahl, W.M. An operationalized understanding of personalized learning. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2016, 31, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, B.; McClaskey, K. A step-by-step guide to personalize learning. Learn. Lead. Technol. 2013, 40, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Lavie, A. METEOR: An automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments. In Proc. ACL Workshop on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evaluation Measures for Machine Translation and/or Summarization, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2005; pp. 65–72.

- Lin, C.-Y. ROUGE: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text Summarization Branches Out; Proceedings of the ACL-04 Workshop, Barcelona, Spain, July 2004; pp. 74–81.

- Novikova, J.; Dušek, O.; Curry, A.C.; Rieser, V. Why we need new evaluation metrics for NLG. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. BLEU: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proc. 40th Annu. Meeting Assoc. Comput. Linguist.; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002; pp. 311–318.

- Crossley, S.; Salsbury, T.; McNamara, D. Measuring L2 lexical growth using hypernymic relationships. Lang. Learn. 2009, 59, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, L.; Schmiedek, F.; Brod, G. Developing personalized education: A dynamic framework. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.; McNamara, D.S. GenAI-powered text personalization: Natural language processing validation of adaptation capabilities. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromley, J.G.; Snyder-Hogan, L.E.; Luciw-Dubas, U.A. Reading comprehension of scientific text: A domain-specific test of the direct and inferential mediation model of reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, R.S.; Starr, L.E.; Bailey, A.L. Syntactic complexity as an aspect of text complexity. Educ. Res. 2015, 44, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, T.; McNamara, D.S. Reversing the reverse cohesion effect: Good texts can be better for strategic, high-knowledge readers. Discourse Process. 2007, 43, 121–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, D.S.; Ozuru, Y.; Floyd, R.G. Comprehension challenges in the fourth grade: The roles of text cohesion, text genre, and readers’ prior knowledge. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2011, 4, 229–257. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, A.; Shortt, M.; Goldshtein, M.; Roscoe, R.D. Assessing academic language in tenth-grade essays using natural language processing. Assess. Writ. in press. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, S.A. Developing linguistic constructs of text readability using natural language processing. Sci. Stud. Read. 2025, 29, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, S.A.; Skalicky, S.; Dascalu, M.; McNamara, D.S.; Kyle, K. Predicting text comprehension, processing, and familiarity in adult readers: New approaches to readability formulas. Discourse Process. 2017, 54, 340–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Snow, P.; Serry, T.; Hammond, L. The role of background knowledge in reading comprehension: A critical review. Read. Psychol. 2021, 42, 214–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D.; Gray, B. Nominalizing the verb phrase in academic scientific writing. In The Verb Phrase in English: Investigating Recent Language Change with Corpora; Aarts, B., Close, J., Leech, G., Wallis, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Schleppegrell, M.J. Reading in Secondary Content Areas: A Language-Based Pedagogy; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Martin, J.R. Writing Science: Literacy and Discursive Power; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schleppegrell, M.J.; Achugar, M.; Oteíza, T. The grammar of history: Enhancing content-based instruction through a functional focus on language. TESOL Q. 2004, 38, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D.; Gray, B.; Poonpon, K. Lexical density and structural elaboration in academic writing over time: A multidimensional corpus analysis. J. English Acad. Purp. 2021, 50, 100968. [Google Scholar]

- Graesser, A.C.; McNamara, D.S.; Kulikowich, J.M. Coh-Metrix: Providing multilevel analyses of text characteristics. Educ. Res. 2011, 40, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, W.E.; Townsend, D. Words as tools: Learning academic vocabulary as language acquisition. Read. Res. Q. 2012, 47, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D.; Gray, B. Nominalizing the verb phrase in academic science writing. In The Verb Phrase in English: Investigating Recent Language Change with Corpora; Aarts, B., Close, J., Leech, G., Wallis, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wang, H.; Buckingham, L. Mapping out the disciplinary variation of syntactic complexity in student academic writing. System 2023, 113, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z. The language demands of science reading in middle school. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 491–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grever, M.; Van der Vlies, T. Why national narratives are perpetuated: A literature review on new insights from history textbook research. London Rev. Educ. 2017, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijgen, T.; Van Boxtel, C.; Van de Grift, W.; Holthuis, P. Toward historical perspective taking: Students’ reasoning when contextualizing the actions of people in the past. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 2017, 45, 110–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, N.D.; McCarthy, P.M.; Graesser, A.C.; McNamara, D.S. Using temporal cohesion to predict temporal coherence in narrative and expository texts. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Drie, J.; Van Boxtel, C. Historical reasoning: Towards a framework for analyzing students’ reasoning about the past. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 20, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wineburg, S.S.; Martin, D.; Monte-Sano, C. Reading like a historian: Teaching literacy in middle and high school history classrooms; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, T.; Shanahan, C. Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content-area literacy. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2008, 78, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, B.; Magill, K.; Salinas, C. Critical historical inquiry: The intersection of ideological clarity and pedagogical content knowledge. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 2020, 44, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D.; Conrad, S.; Cortes, V. If you look at…: Lexical bundles in university teaching and textbooks. Appl. Linguist. 2004, 25, 371–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. As can be seen: Lexical bundles and disciplinary variation. English Spec. Purp. 2008, 27, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvern, D.; Richards, B.; Chipere, N.; Durán, P. Lexical diversity and language development; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2004; pp. 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, P.M.; Jarvis, S. MTLD, vocd-D, and HD-D: A validation study of sophisticated approaches to lexical diversity assessment. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, K.; Oakhill, J.V.; Barnes, M.A.; Bryant, P.E. Comprehension skill, inference-making ability, and their relation to knowledge. Mem. Cognit. 2001, 29, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, J.P.; Millis, K.K.; RSAT Development Team; Levinstein, I. ; Boonthum, C. Assessing comprehension during reading with the Reading Strategy Assessment Tool (RSAT). Metacogn. Learn. 2011, 6, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Neri, N.; Guill, K.; Retelsdorf, J. Language in science performance: Do good readers perform better? Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 36, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, D.S. Reading both high-coherence and low-coherence texts: Effects of text sequence and prior knowledge. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 2001, 55, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickren, S.E.; Stacy, M.; Del Tufo, S.N.; Spencer, M.; Cutting, L.E. The contribution of text characteristics to reading comprehension: Investigating the influence of text emotionality. Read. Res. Q. 2022, 57, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, T.; McCarthy, K.S.; McNamara, D.S. iSTART StairStepper—Using comprehension strategy training to game the test. Comput. 2021, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, R.T. Syntactic complexity in journal research article abstracts written in English. MEXTESOL J. 2022, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, H.; Wu, X.; Liu, Q.; Su, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Q. Word concreteness modulates bilingual language control during reading comprehension. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2024, Advance online publication.

- Chen, L.; Zaharia, M.; Zou, J. How is ChatGPT’s behavior changing over time? Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Xie, Q.; Ananiadou, S. Factual consistency evaluation of summarization in the era of large language models. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cong, T.; Zhao, Z.; Backes, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y. Robustness over time: Understanding adversarial examples’ effectiveness on longitudinal versions of large language models. arXiv Preprint 2023, arXiv:2308.07847. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, A.; Lazebnik, T. Whose LLM is it anyway? Linguistic comparison and LLM attribution for GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Bard. arXiv Preprint, 2024; arXiv:2402.14533. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, D.S.; Graesser, A.C.; Louwerse, M.M. Sources of text difficulty: Across genres and grades. In Measuring Up: Advances in How We Assess Reading Ability; Sabatini, J.P., Albro, E., O’Reilly, T., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2012; pp. 89–116. [Google Scholar]

- Achugar, M.; Schleppegrell, M.J. Beyond connectors: The construction of cause in history textbooks. Linguist. Educ. 2005, 16, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatiyatullina, G.M.; Solnyshkina, M.I.; Kupriyanov, R.V.; Ziganshina, C.R. Lexical density as a complexity predictor: The case of science and social studies textbooks. Res. Result. Theor. Appl. Linguist. 2023, 9, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.C. Nouns in history: Packaging information, expanding explanations, and structuring reasoning. Hist. Teach. 2010, 43, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Follmer, D.J.; Li, P.; Clariana, R. Predicting expository text processing: Causal content density as a critical expository text metric. Read. Psychol. 2021, 42, 625–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atil, B.; Chittams, A.; Fu, L.; Ture, F.; Xu, L.; Baldwin, B. LLM Stability: A detailed analysis with some surprises. arXiv e-prints, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Savova, G.; Wang, L. Assessing the macro and micro effects of random seeds on fine-tuning large language models. arXiv Preprint 2025, arXiv:2503.07329. [Google Scholar]

- Alkaissi, H.; McFarlane, S.I. Artificial Hallucinations in ChatGPT: Implications in Scientific Writing. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, R.; Simmons, B.; Thornton, J.E. A call to address AI “hallucinations” and how healthcare professionals can mitigate their risks. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laban, P.; Kryściński, W.; Agarwal, D.; Fabbri, A.R.; Xiong, C.; Joty, S.; Wu, C.S. LLMs as factual reasoners: Insights from existing benchmarks and beyond. arXiv Preprint 2023, arXiv:2305.14540. [Google Scholar]

| Features | Metrics and Descriptions |

| Writing Style | Academic writing*: The extent to which the texts include domain-specific words and sophisticated sentence structures, commonly found in academic writing texts |

| Conceptual Density and Cohesion | Lexical density: The extent to which text contains sentences with dense and precise information, including complex noun phrases and sophisticated and specific function words Noun-to-verb ratio*: Text with a high noun-to-verb ratio results in dense information and complex sentences that require greater cognitive effort to process Sentence cohesion*: The extent to which the text contains connectives and cohesion cues (e.g., repeating ideas and concepts) |

| Syntax Complexity | Sentence length*: Longer sentences often have more clauses and complex structure Language variety*: The extent to which the text contains a variety of lexical and syntax structures |

| Lexical Complexity | Word concreteness: The degree to which words are tangible and refer to concepts that can be experienced by the senses. High measures indicate the texts contain more tangible words, while low measures indicate more abstract concepts Sophisticated wording*: Lower measures indicate the vocabulary familiar and common, whereas higher measures indicate more advanced words Academic frequency*: Indicates the extent of sophisticated vocabulary are used, which are also common in academic texts |

| Connectives | All connectives: Refers to the overall density of linking words and phrases (e.g., however, therefore, then, in addition). Higher values indicate the text is overtly guiding the reader through logical, additive, contrastive, temporal, or causal relations, increasing cohesion. Lower values imply that relationships must be inferred from context Temporal connectives: Markers that place events on a timeline (e.g., then, meanwhile, during, subsequently) Causal connectives: Markers that signal cause-and-effect or reasoning links (e.g., because, since, therefore, thus, as a result) |

| Domain | Topic | Text Titles | Word Count | FKGL* |

| Science | Biology | Bacteria | 468 | 12.10 |

| Science | Biology | The Cells | 426 | 11.61 |

| Science | Biology | Microbes | 407 | 14.38 |

| Science | Biology | Genetic Equilibrium | 441 | 12.61 |

| Science | Biology | Food Webs | 492 | 12.06 |

| Science | Biology | Patterns of Evolution | 341 | 15.09 |

| Science | Biology | Causes and Effects of Mutations | 318 | 11.35 |

| Science | Biochemistry | Photosynthesis | 427 | 11.44 |

| Science | Chemistry | Chemistry of Life | 436 | 12.71 |

| Science | Physics | What are Gravitational Waves? | 359 | 16.51 |

| History | American History | Battle of Saratoga | 424 | 9.86 |

| History | American History | Battles of New York | 445 | 11.77 |

| History | American History | Battles of Lexington and Concord | 483 | 12.85 |

| History | American History | Emancipation Proclamation | 271 | 13.4 |

| History | American History | House of Burgesses | 200 | 12.8 |

| History | American History | Abraham Lincoln- Rise to Presidency | 631 | 12.15 |

| History | American History | George Washington | 260 | 9.79 |

| History | French & American History | Marquis de Lafayette | 356 | 13.78 |

| History | Dutch & American History | New York (New Amsterdam) Colony | 403 | 12.97 |

| History | World History | Age of Exploration | 490 | 10.49 |

| Linguistic Features |

Reader 1 (High RS/ High PK*) | Reader 2 (High RS/Low PK*) | Reader 3 (Low RS/ High PK*) | Reader 4 (Low RS/Low PK*) | Main Effects of Profile | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F (3, 320) | p | η2 | |

| Academic Writing | 75.84 | 24.74 | 51.66 | 26.48 | 33.06 | 27.15 | 34.30 | 22.96 | 121.25 | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| Language Variety | 80.73 | 19.21 | 50.76 | 20.57 | 27.72 | 17.39 | 30.33 | 18.44 | 251.32 | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| Lexical Density | .68 | .12 | .61 | .12 | .59 | .11 | .58 | .10 | 226.13 | <0.001 | 0.53 |

| Sentence Cohesion | 32.86 | 28.89 | 54.75 | 29.93 | 55.83 | 22.68 | 60.45 | 26.92 | 35.11 | <.001 | .15 |

| Noun-to-Verb Ratio | 2.79 | .46 | 2.53 | .55 | 2.54 | .72 | 1.84 | .34 | 119.86 | <.001 | .37 |

| Sentence Length | 18.62 | 5.97 | 14.78 | 5.49 | 14.59 | 4.47 | 13.53 | 4.11 | 61.98 | <.001 | .23 |

| Word Concreteness | 29.86 | 17.79 | 50.52 | 25.63 | 55.18 | 27.21 | 60.76 | 24.96 | 57.26 | <.001 | .22 |

| Sophisticated Word | 88.85 | 9.52 | 51.12 | 21.09 | 29.05 | 17.64 | 23.42 | 16.06 | 603.28 | <.001 | .75 |

| Academic Frequency | 10842.04 | 1812.02 | 9471.83 | 1517.92 | 9017.30 | 1812.29 | 8823.87 | 1779.10 | 57.97 | <.001 | .22 |

| Causal Connectives | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | 3.11 | .03 | .02 |

| Temporal Connectives | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .79 | .50 | .00 |

| All Connectives | .05 | .01 | .05 | .01 | .05 | .01 | .05 | .01 | 3.54 | .02 | .02 |

| Linguistic Features |

Claude | Llama | Gemini | ChatGPT | Main Effects of LLMs | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F (3, 320) | p | η2 | |

| Academic Writing | 48.42 | 31.73 | 53.28 | 30.50 | 45.78 | 30.98 | 47.37 | 29.23 | 1.98 | 0.12 | 0.01 |

| Language Variety | 47.16 | 29.78 | 40.04 | 27.99 | 54.42 | 28.78 | 47.92 | 25.37 | 12.12 | <.001 | 0.06 |

| Lexical Density | .62 | .12 | .61 | .12 | .62 | .12 | .61 | .12 | 5.26 | 0.001 | 0.03 |

| Sentence Cohesion | 63.35 | 28.59 | 41.55 | 27.20 | 47.94 | 27.31 | 51.05 | 29.52 | 21.73 | <.001 | 0.10 |

| Noun-to-Verb Ratio | 2.56 | .84 | 2.38 | .56 | 2.44 | .57 | 2.33 | .51 | 7.88 | <.001 | 0.17 |

| Sentence Length | 12.46 | 4.38 | 16.32 | 5.15 | 16.38 | 5.09 | 16.35 | 5.88 | 42.71 | <.001 | 0.17 |

| Word Concreteness | 47.33 | 26.23 | 46.25 | 26.89 | 51.94 | 27.85 | 50.80 | 26.00 | 1.60 | .189 | 0.10 |

| Sophisticated Word | 47.30 | 32.20 | 46.70 | 27.88 | 49.38 | 31.52 | 49.05 | 30.82 | 2.72 | .044 | 0.01 |

| Academic Frequency | 8848.43 | 1915.11 | 10388.74 | 1847.94 | 9592.04 | 1875.01 | 9325.83 | 1638.72 | 48.392 | <.001 | 0.19 |

| Causal Connectives | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .56 | .64 | 0.00 |

| Temporal Connectives | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | 11.87 | <.001 | 0.06 |

| All Connectives | .05 | .01 | .05 | .01 | .05 | .01 | .05 | .01 | 4.03 | .007 | 0.02 |

| Linguistic Features |

Science Texts | History Texts | Main Effects of Text Types | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | F (1, 320) | p | η2 | |

| Academic Writing | 50.08 | 27.98 | 47.34 | 33.15 | 2.80 | .10 | 0.01 |

| Language Variety | 47.06 | 29.30 | 47.71 | 27.56 | .84 | .36 | 0.00 |

| Lexical Density | .72 | .06 | .51 | .05 | 5743.50 | <.001 | 0.90 |

| Sentence Cohesion | 51.26 | 28.63 | 50.68 | 29.80 | .09 | .76 | 0.00 |

| Noun-to-Verb Ratio | 2.34 | .58 | 2.51 | .68 | 18.31 | <.001 | 0.03 |

| Sentence Length | 17.67 | 5.21 | 13.09 | 4.59 | 254.88 | <.001 | 0.30 |

| Word Concreteness | 49.53 | 28.42 | 48.62 | 25.10 | .12 | .73 | 0.00 |

| Sophisticated Word | 49.27 | 30.95 | 46.94 | 30.25 | 5.00 | .03 | 0.01 |

| Academic Frequency | 10557.87 | 1670.58 | 8519.65 | 1540.14 | 412.42 | <.001 | 0.41 |

| Causal Connectives | .01 | .01 | .00 | .00 | 78.44 | <.001 | 0.11 |

| Temporal Connectives | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | 17.01 | <.001 | 0.03 |

| All Connectives | .06 | .01 | .05 | .01 | 26.50 | <.001 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).