1. Introduction

Reading is a fundamental learning activity that supports students in acquiring new knowledge and developing expertise across domains [

1]. To build a coherent understanding of complex topics, readers must integrate information from texts into an interconnected mental model [

2]. While learning from texts is essential for academic success, it can be challenging for students who lack prior knowledge in the topic or reading skills [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Reading comprehension is influenced by both reader characteristics and textual features. Text readability is the extent to which a reader can process and understand a text [

8,

9]. The same text can be easy or challenging to a reader depending on their reading skills and familiarity with the topic. Given the significance of reading comprehension in learning and the variability in reader characteristics, personalized learning emerged to address students' diverse needs.

1.1. Personalized Learning.

Personalized learning involves matching students with learning materials at an appropriate difficulty level, thereby enhancing comprehension and engagement, and supporting vocabulary acquisition, skill development, and overall academic success [

8,

10]. Reading texts suited to students’ abilities fosters interest, motivation, and a passion for learning [

10,

11,

12]. Prior research has demonstrated the importance and efficacy of matching text to readers’ abilities to optimize comprehension and learning outcomes [

12,

13,

14]. Matching the right texts to students’ abilities not only improves comprehension and engagement but also supports vocabulary acquisition, skill development, and academic success [

10,

11].

The Lexile Framework is a widely used text-reader matching tool that determines the reading skill of children and matches them with texts at an appropriate difficulty level [

15,

16]. This framework quantifies text difficulty based on factors such as syntactic complexity, sentence length, and word frequency, while reader skill is assessed using standardized assessment. The Lexile Framework enables instructors to select reading materials that match students’ reading levels with text at appropriate difficulty level [

17]. While established frameworks like Lexile have demonstrated effectiveness, advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) provide promising tool to implement personalized learning at scale.

Generative AI (GenAI) plays a crucial role in advancing personalized learning by dynamically modifying learning materials tailored specifically to students’ needs and abilities. Large Language Models (LLMs) applications have been leveraged to adapt writing style, simplify content, and generate materials tailored to the individual needs [

1]. For instance, Martínez et al. (2024) leveraged LLMs to simplify content, adjust lexical and syntactic complexity to enhance accessibility for students with learning disabilities [

18]. Similarly, researchers have leveraged LLMs and OpenAI’s API to automatically generate personalized reading materials and comprehension assessment within learning management system. These personalized experiences resulted in higher student engagement and increased their study time, ultimately enhancing academic performance and outcomes [

18,

19].

Although the positive impact of personalization on learners’ engagement and performance is well-established, implementation of GenAI-powered personalization in the classroom remains challenging. While text adaptation using LLMs offers a scalable solution to personalize learning, evaluating the effectiveness of modifications can be complicated. Effective text personalization requires rapid validation and iterative refinements to ensure that materials continuously align with students’ evolving needs and learning goals. Traditional assessment (e.g., human comprehension study) is both time-consuming and resource-intensive, which makes it challenging and impractical to implement on a large scale. To address this challenge, an automated and scalable validation method is necessary to evaluate the extent to which personalized content aligns with students’ various needs and assets.

1.2. Evaluating Text Differences Using NLP

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a computational approach that systematically analyzes and extracts patterns from text [

7]. NLP has been used extensively in computer-based learning systems to assess student-generated responses (e.g., self-explanations, think-aloud responses, essays, open-ended answers). Linguistic and semantic metrics derived using NLP provide insights into how students process and comprehend texts [

20,

21]. NLP has been widely applied in educational and psychological research to assess task performance, infer cognitive attributes, and examine individual differences (e.g., literacy skills, prior knowledge; [

22,

23,

24].

NLP text analysis tools (e.g., Coh-Metrix) [

10,

25] have also been applied to extract and analyze linguistic features that influence text readability based on comprehension theories [

8,

25]. Text readability is the extent to which a reader can process and understand a text and it is quantifiable based on linguistic indices [

8,

10]. NLP tools provide linguistic metrics that are associated with coherence-building processes and reading comprehension for different students [

23]. NLP analyses afford systematically distinguishing between different types of texts and discourse based on linguistic and semantic features, and in turn evaluate the readability and difficulty of texts [

8,

25].

1.3. Linguistic Features and Text Readability

Several linguistic features related to text difficulty affect coherence-building processes and reading comprehension for different students [

8]. NLP tools allow researchers to analyze these features to assess comprehension differences across readers [

8,

25]. For instance, cohesion (e.g., connectives, causal, referential, coreference) refers to how well ideas are connected within a text and influences how readers synthesize information and construct meaning [

11,

26]. High-cohesion texts benefit low-knowledge readers who lack the necessary background knowledge to infer meanings due to conceptual gaps [

26]. In contrast, low-cohesion texts are more suitable for high-knowledge readers, as they facilitate deep learning by encouraging inference generation using prior knowledge [

26].

NLP tools also provide metrics related to lexical and syntactic features that are associated with text difficulty (e.g., noun-to-verb ratio, language variety, sentence length). Scientific texts often contain dense information, abstract concepts, and complex sentence structures which make them challenging for students to process information and extract meaning [

27,

28]. Additionally, academic vocabulary increases comprehension difficulty because readers need to have relevant background knowledge to infer word meanings [

28,

29]. While skilled readers can comprehend effectively because they have more knowledge and use effective reading strategies, students who lack sufficient reading skills struggle to comprehend and learn from these texts [

30].

Table 1 describes several linguistic measures related to text complexity that have been shown to correspond to comprehension difficulties faced by students [

10,

11]. These linguistic patterns provide objective, quantifiable measures of text difficulty that correlate with expert judgments of readability [

9]. To effectively tailor text readability for diverse readers with unique characteristics, it is essential to examine the alignment between linguistic features and reader abilities. Additionally, assessing multiple linguistic features related to text difficulty, rather than relying on a single metric, provides a more comprehensive assessment of readability [

8].

As adaptive learning technologies evolve, automated methods for quick and efficient assessment of text modifications are essential. Leveraging NLP to validate modifications offers several advantages over traditional human assessment. NLP can quantify text complexity and provide an objective validation method for text personalization. NLP is efficient and scalable, which allows for iterative evaluation of content across various domains without requiring multiple human studies. NLP assessment can be automated to provide immediate feedback enabling real-time assessment and text refinement. As a result, personalized content can be modified based on quantitative feedback, assessed, and adapted iteratively.

Current Research. In the following studies, we examined how Generative AI (GenAI) can personalize educational texts for different reader profiles by leveraging Natural Language Processing (NLP) to validate modifications. In Experiment 1, we prompted LLMs to modify scientific texts to accommodate four different reader profiles varying in knowledge, reading skills, and learning goals. In Experiment 2, we refined prompting strategies to improve text personalization and focused on one LLM to examine the effect. NLP was leveraged to evaluate how different LLMs and prompting techniques adjust text readability to examine the extent to which modifications align appropriately with the unique needs of readers. We aimed to explore two research questions: 1. To what extent do different LLMs adapt scientific texts for different reader profiles? 2. How does augmented prompting strategies influence the quality of modified texts? These studies highlight how NLP can be applied to validate text readability in real time across large datasets. NLP also facilitates rapid assessment and iteration so that adaptive learning technologies can quickly tailor content to suit students’ needs. Rapid testing and refinement help ensure that learning materials are effectively tailored and personalized to optimize student's learning.

2. Experiment 1: LLM-Text Personalization

In Experiment 1, we examined how four LLMs (Claude 3.5 Sonnet; Llama; Gemini Pro 1.5; ChatGPT 4) modify scientific texts to suit unique reader characteristics and contexts (i.e., prior knowledge, reading skills, learning goals). Ten texts from biology, chemistry, and physics were adapted to align with reader characteristics. NLP was used to analyze linguistic features in the adapted texts to evaluate how well each LLM adjusted text readability to suit the intended readers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. LLM Selection and Implementation Details

The four LLMs selected for the comparative analysis were Claude 3.5 Sonnet (Anthropic), Llama (Meta), Gemini Pro 1.5 (Google), and ChatGPT 4 (OpenAI). See Appendix 1 for details (e.g., versions, dates of usage, training size and parameters) of the four LLMs. These models were selected for the comparison because of the comparable training size and parameters. While the exact numbers of training size vary across models, they are all well-known for their comparable capabilities in language understanding and generating contextually relevant text. Each model is known for its proficiency in natural language understanding and generating contextually relevant text.

3.2. Text Corpus

Ten expository texts in the domains of biology, chemistry and physics were compiled (see Appendix 2). These texts were selected from the iSTART website (

www.adaptiveliteracy.com/istart) [

31,

32]. The texts were chosen for their varying levels of complexity and relevance to scientific topics which are suitable for testing the models’ ability to modify text based on different reader profiles.

Table 2 provides the list of the texts, domains, titles, number of words and the Flesch-Kincaid grade level.

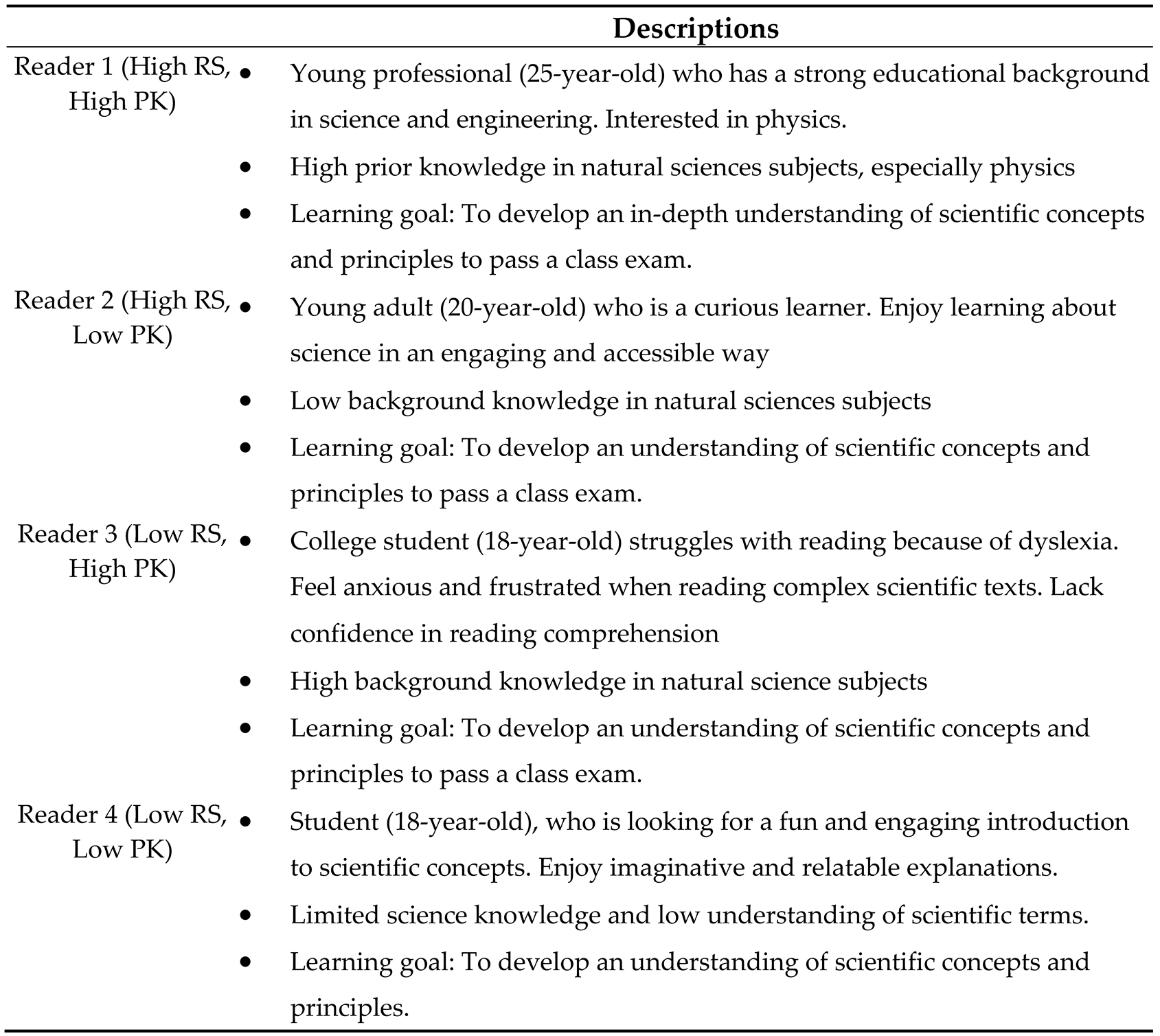

3.3. Reader Profile

Four hypothetical reader profiles were created to simulate readers’ unique characteristics and assess LLMs’ capability to adapt texts to the persona. The characteristics of these four reader profiles differ across background knowledge and reading levels. Each profile included detailed information on the reader’s age, educational background, reading level, prior knowledge, interests, and reading goals (see

Table 3 for reader profile descriptions). While four profiles are limited to explore the extent to which LLM can tailor text to each reader, we designed these four as a proof-of-concept to initially explore personalized adaptations and NLP capabilities in evaluating personalized content.

3.4. Natural Language Processing

The linguistic features of each text modification were extracted using the Writing Analytics Tool (WAT; [

33,

34,

35]). All modifications from all 10 texts were aggregated into one file. The level of text complexity is signified by various linguistic features [

27,

28,

29]. Texts written using academic language, uncommon vocabulary, high lexical density, and complex syntax pose challenges for many readers [

36,

37]. In addition, text comprehensibility can be enhanced by revising materials to include clearer causal relationships, explicit explanations, and more elaborated background information for low-skill, low-knowledge readers [

37].

To assess text suitability to reader profile, we assessed various aspects of the text readability and complexity. See

Table 1 for descriptions of each linguistic feature. We also examined the level of similarity between modified versions and the original text to judge whether the LLM adapted texts and how much changes have been made.

3.5. Procedure

The four LLMs was prompted to modify 10 scientific texts to suit four different reader profiles varying in prior knowledge and reading skill. See

Appendix B for details of the prompts used. The LLMs were prompted to modify each text to improve comprehension and engagement for a reader with the goal to tailor the text to align with the unique characteristics of the reader (age, educational background, reading skill, prior knowledge, and reading goals).

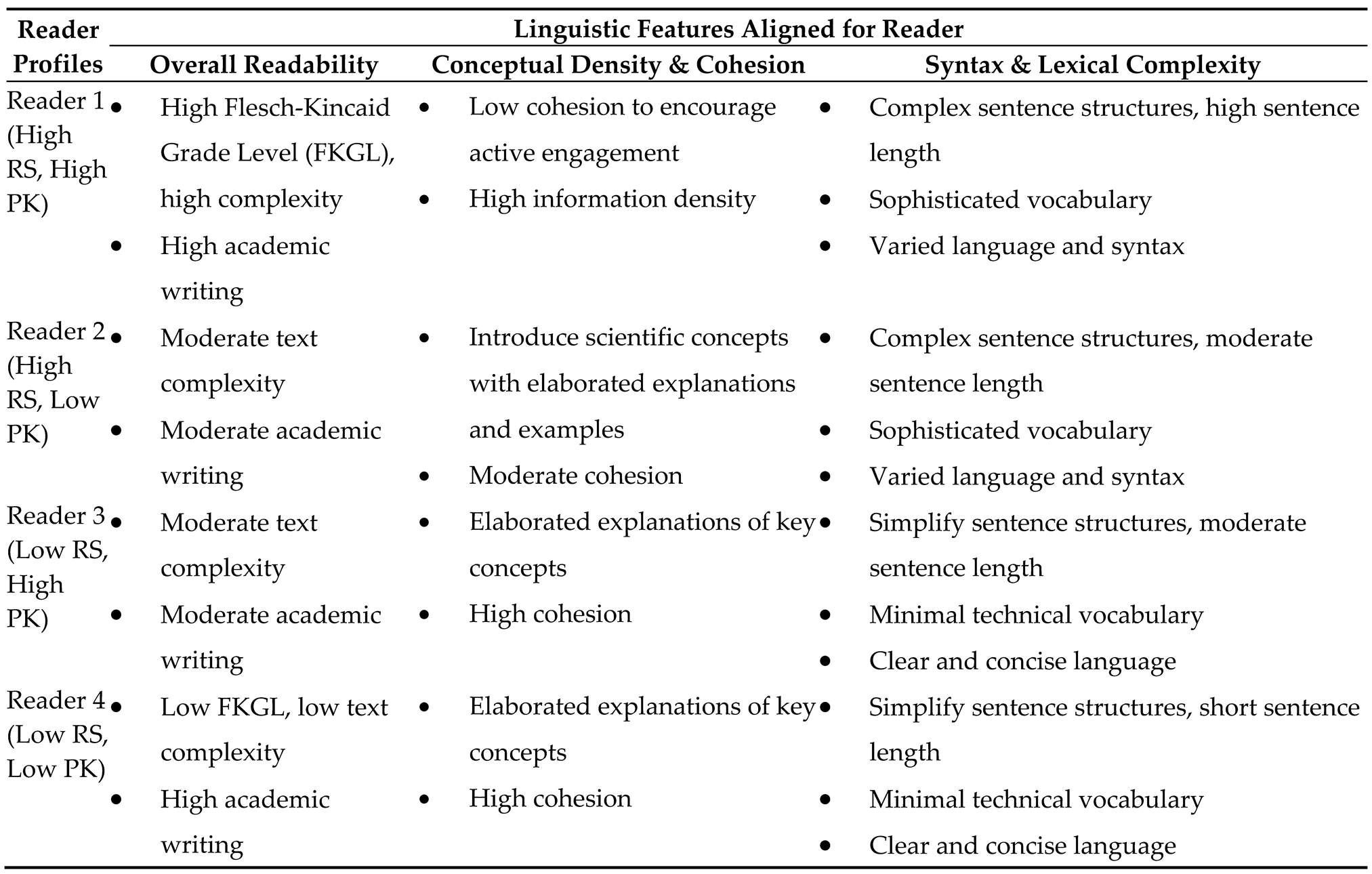

Table 2 provides the descriptions of the four reader profiles that varied as a function of prior knowledge (PK) and reading skill (RS). For each reader profile, the procedure was repeated 10 times, each time with one text. Then the conversation history was erased, and the same procedure was repeated for the next reader profile, modifying 10 science texts using the same prompt. In total, each LLM was prompted 40 times, generated 160 modifications for four reader profiles from four LLMs (Claude, Llama, ChatGPT, Gemini).

The linguistic features (as shown in

Table 1) were extracted using WAT which provides linguistic and semantic indices associated with writing quality. These indices serve as validation metrics to evaluate linguistic and semantic features of the LLM text personalization. By aligning linguistic features with given reader profiles, we provide a basis to assess the extent to which LLM modifications appropriately tailor texts to suit readers’ needs (e.g., low-knowledge readers benefit from cohesive text and simplified syntax, vocabulary; high-knowledge readers benefit from lower cohesion and increased complexity). In

Table 4, we outline how linguistic features should be adapted to align with characteristics of various reader profiles.

4. Results

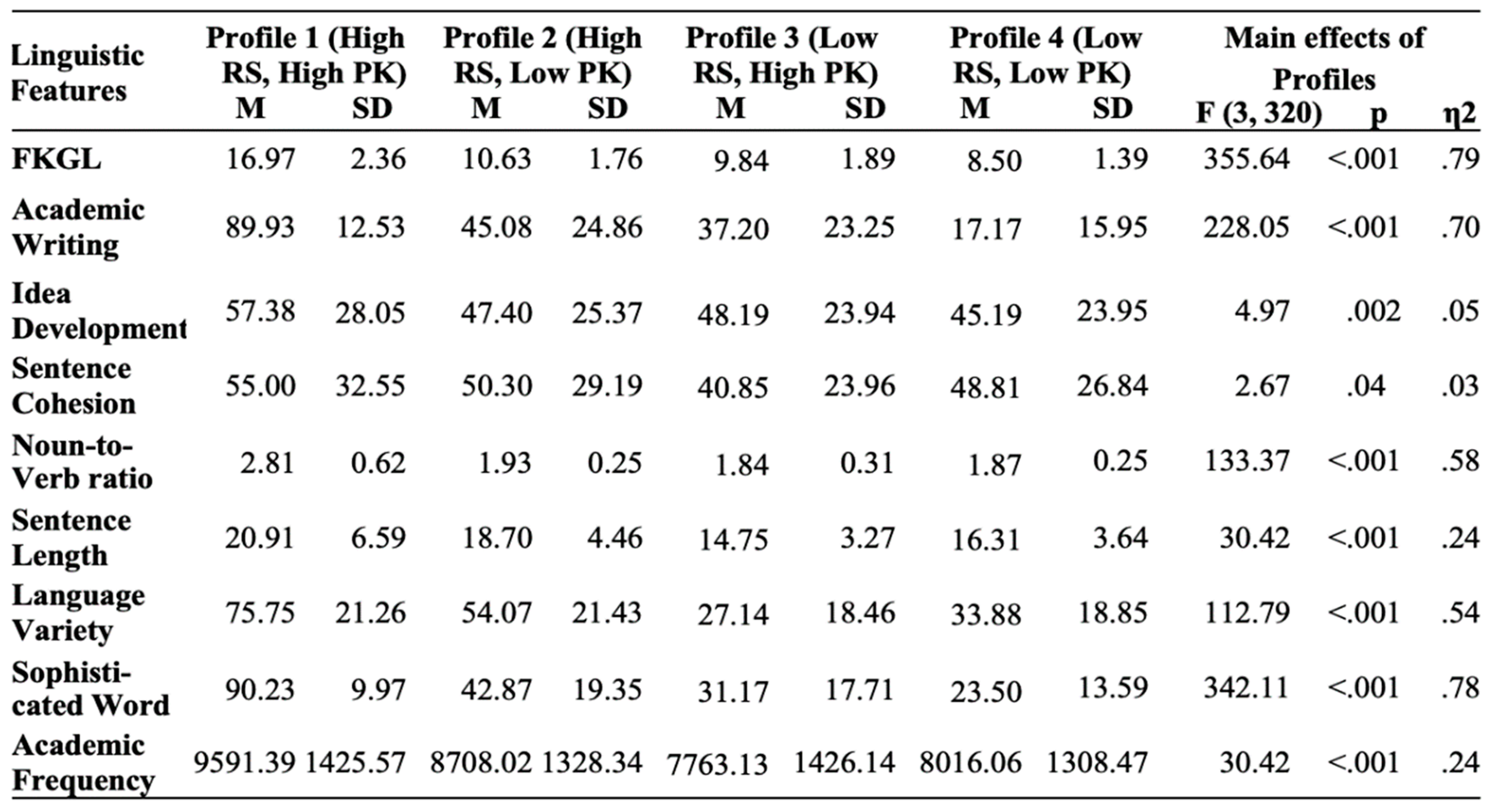

4.1. Main Effect of Reader Profile on Variations in Linguistic Features of Modified Texts.

The goal of this analysis was to examine the extent to which the linguistic features of LLM-modified texts aligned with different reader profiles. A 4x4 MANCOVA was conducted to examine the effects of reader profiles (High RS/High PK, High RS/Low PK, Low RS/High PK, Low RS/Low PK) and LLMs (Claude, Llama, Gemini, ChatGPT) on linguistic features of modifications, with word count included as a covariate. The main effect of reader profiles on linguistic features was significant. See

Table 5 for descriptive statistics and F-values of main effects of reader profiles. Results showed that linguistic features of modifications significantly differed across reader profiles.

As expected, the modifications for Profile 1 (High RS/High PK) had the highest syntactic and lexical complexity measures, followed by Profile 2, then 3 and 4. Texts modified for Profile 1 had significantly higher Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) (M = 16.97, SD = 2.36) compared to texts modified for Profile 2 (High RS, Low PK) (M = 10.63, SD = 1.76), p<.001 and Profile 3 (Low RS, High PK) (M = 9.84, SD = 1.89), p<.001 and Profile 4 (Low RS, Low PK) (M = 8.50, SD = 1.39), p<.001. Pairwise comparisons also revealed significant differences across reader profiles for measures of text complexity, including Academic Writing, Noun-to-Verb Ratio, Sentence Length, Language Variety, Sophisticated Wording, and Academic Vocabulary, aligning with the hypothesized difficulty levels for each profile. As intended, texts modified for Profile 1 had the highest complex syntax and lexical measures, followed by Profile 2, 3, and 4 (all p<.05). Contrary to expectations, cohesion was higher for Profile 1, who has high-knowledge compared to Profile 2 and 4, who both have low prior knowledge (p<.05).

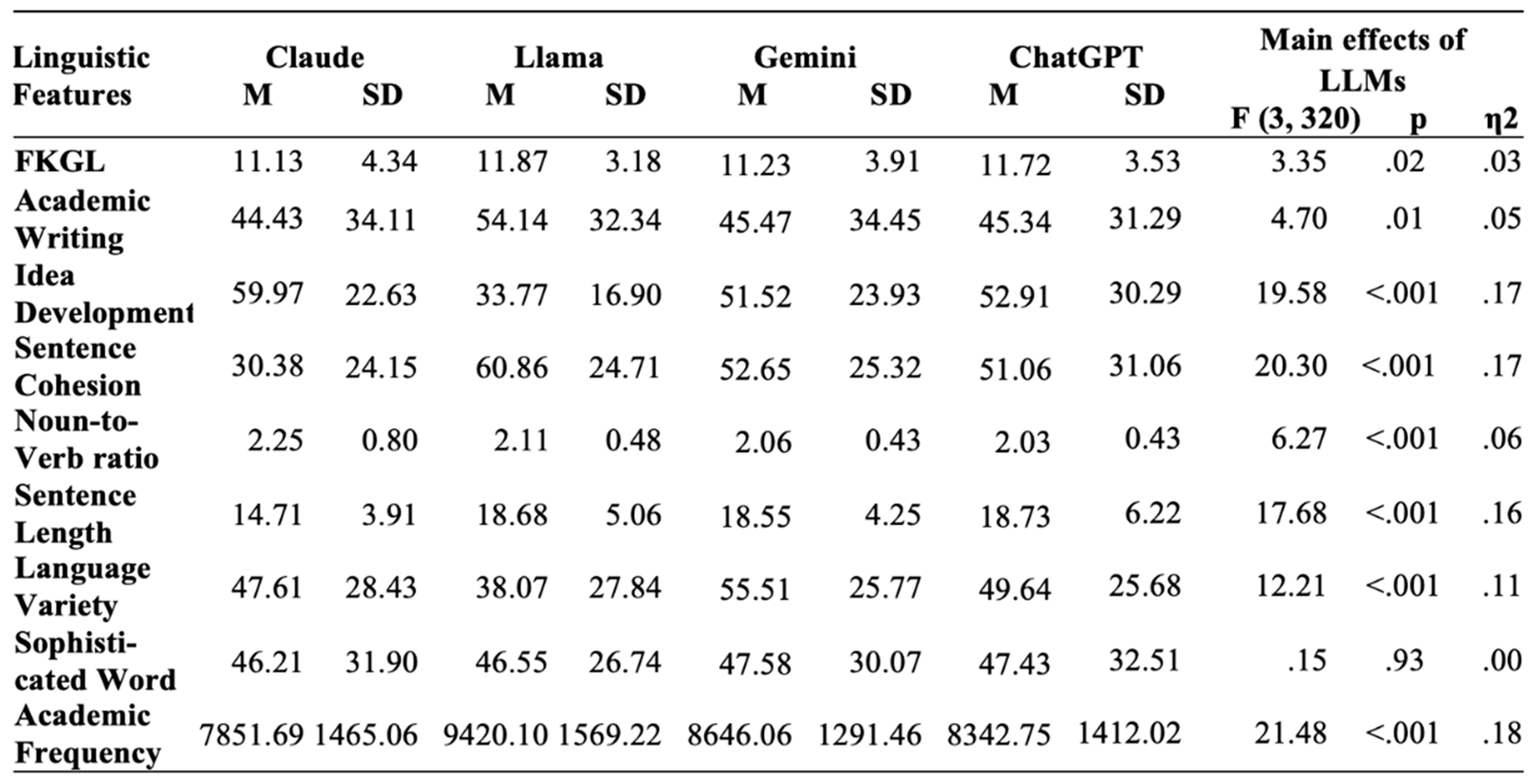

4.2. Main Effect of LLMs

The main effect of models was significant. Linguistic features of modifications from different LLMs differed regardless of reader characteristics. See

Table 6 for descriptive statistics and F-values.

Llama’s modifications (M = 11.87, SD = 3.18) had significantly higher FKGL compared to modifications by Claude (M = 11.13, SD = 4.34), p<.05. Llama’s modifications are significantly higher in Academic Writing, Academic Wording compared to modifications by Claude, Gemini, and ChatGPT (all p<0.05). Modifications by Claude (M = 30.38, SD = 24.15) had significantly lower Sentence Cohesion compared to modifications by Llama (M = 60.86, SD = 24.71), p < .001, Gemini (M = 52.65, SD = 25.32), p<.001, ChatGPT (M = 51.06, SD = 31.06), p< .001. Modifications by Gemini had the highest Language Variety (M = 55.51, SD = 25.77), compared to texts generated by Claude (M = 47.61, SD = 31.9), p<.05 and Llama (M = 38.07, SD = 27.84), p<.001.

5. Experiment 1 Discussion

NLP analyses showed variations in linguistic features that were adjusted by various LLMs to address individual differences. These variations ensure that the modifications were comprehensible and suitable for the given reader. Specifically, modifications generated for high-skill and high prior knowledge profiles showed greater syntax and lexical complexity, academic writing style, and sophisticated language. In contrast, texts modified for high-skill, low-knowledge profiles featured long sentences, sophisticated wording, and varied language while maintaining moderate information density to avoid overwhelming readers with many science concepts due to lower knowledge. Modifications for low-knowledge and less skilled readers simplified sentence structures and wording to increase readability. LLMs’ sensitivity to different reader’s needs led to variation in linguistic features of modified texts, which was captured by NLP analyses.

Moreover, each LLM’s modifications differed linguistically regardless of reader profiles. Claude’s modifications contained short sentences and were least cohesive but also had the highest idea development measure. Llama’s modifications had the highest complexity measures (e.g., FKGL, Academic Vocabulary, Academic Writing). Gemini balanced depth of information with engaging and cohesive language, used relatable analogies, illustrative examples which are particularly beneficial for educational materials. ChatGPT modifications were cohesive and elaborated concepts thoroughly in the modifications, especially for low-knowledge profiles.

However, NLP analyses also revealed that cohesion features were not appropriately aligned with readers' needs, which contradicts findings for optimal comprehension suggested by prior research [

11,

26,

37]. These inconsistencies in modification highlighted the need to improve prompting technique and provide LLMs with more explicit instructions and background information to guide the modification process. The single-shot prompt used in Experiment 1 lacks context-relevant information that could guide LLMs to perform the task more precisely. Having acknowledged limitations in the generic prompt, we refined and tested an augmented prompt that was more detailed and structured to improve text personalization.

6. Experiment 2: Prompt Refinements

In study 1 and 2, the LLMs did not effectively tailor cohesion features to align with the reader's background knowledge, as suggested by reading comprehension research [

11,

26,

37]. Specifically, texts modified for high-knowledge readers had high cohesion measures compared to modifications for low-knowledge readers. Prior research by McNamara (2001) demonstrated that when reading highly cohesive texts, high-knowledge but less skilled readers have an illusion of understanding [

26]. Cohesion has a critical role in comprehension and learning because conceptual gaps can promote active processing to generate bridging inferences. In contrast, readers with low prior knowledge benefit from cohesive texts since they lack the necessary background knowledge to fill in conceptual gaps. The mismatch in cohesion for modifications for high versus low knowledge readers suggested that the LLMs requires further instruction on how to adjust cohesion appropriately for these profiles. Specifically, there might be some limitations in the LLM’s ability to fully differentiate text cohesion for this specific reader profile which highlights the need for further refinement in tailoring text modifications for less-skilled, high-knowledge readers.

Findings from NLP analyses also showed that idea development measures of modifications tailored for high-knowledge and skilled readers were significantly higher compared to modifications for all other profiles. When reading for academic purposes, it is crucial that students can learn effectively from the text. As such, scientific concepts should be sufficiently and equally elaborated for all students and not just the skilled ones. It is critical that text modifications for low knowledge or less-skilled profiles simplify vocabulary and syntax but still cohesive and comprehensive.

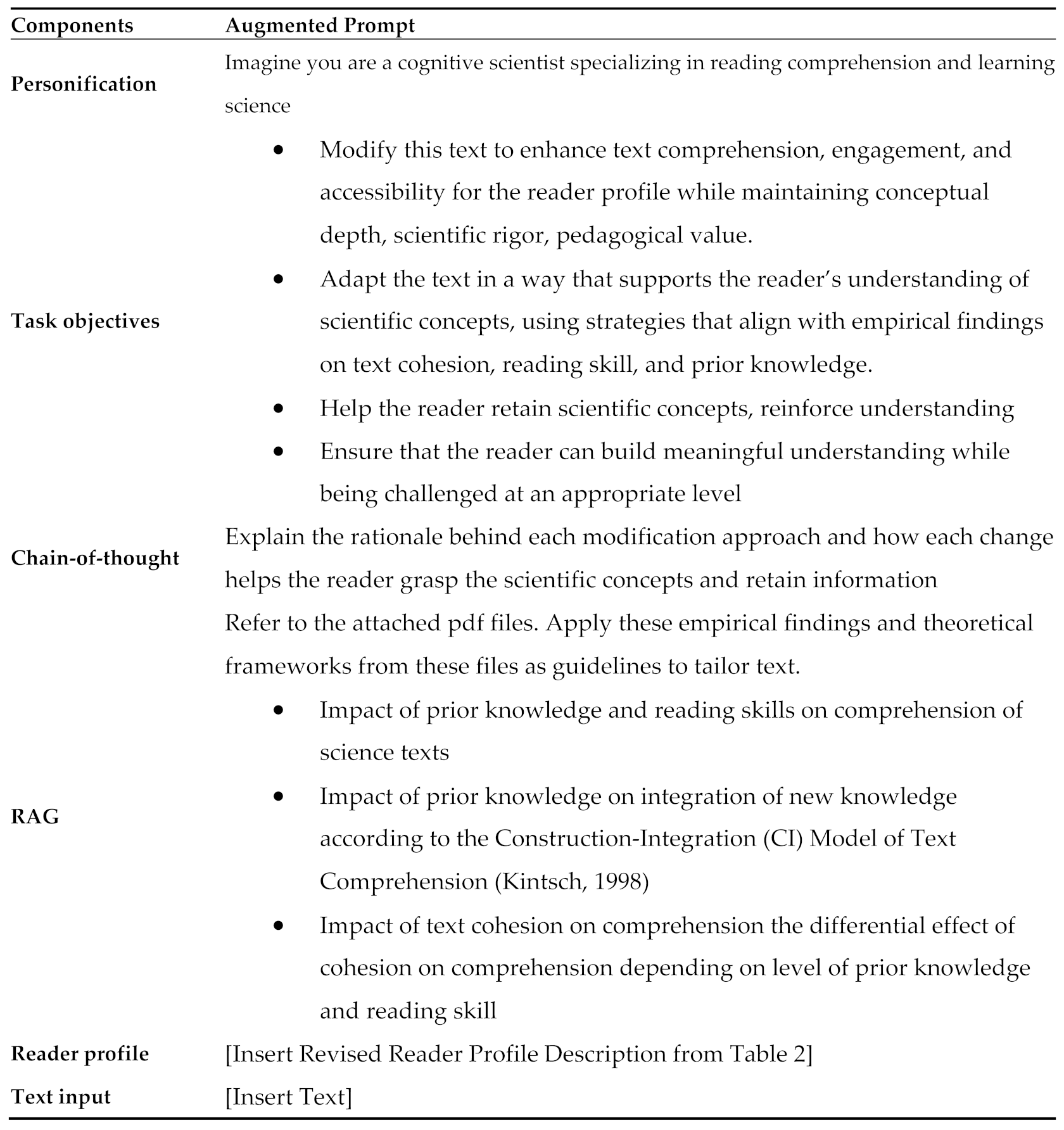

Prompt Improvements

One of the most effective methods to enhance LLMs performance is by instructing the models with clear and structured prompts. Providing LLM with additional context on how to complete the task also helps LLMs generate more accurate outputs and follow adaptation guidelines suggested by prior research [

38]. Srivastava et al. (2022) demonstrated that prompting plays a critical role in determining the quality and relevance of the model’s responses [

39]. The author discussed how the input prompt can influence the variability in performance such that ambiguous or underspecified prompts can lead to inconsistent outputs. Based on findings study 1 and 2 in this proposal, we identified several areas for improvement from the current prompt to enhance text personalization. Iterative prompt improvement can potentially improve LLM capability in tailoring texts to specific reader profiles. As such, the primary focus of Experiment 2 is on enhancing prompts to optimize the LLM performance in text personalization.

Several refinements were made to the prompt used in Experiment 1. See Table 14 for changes made to the modified prompts. First, the descriptions of reader profiles lacked specificity and clarity. To address this, we included more detailed, and quantifiable metrics to demonstrate reading proficiency and prior knowledge level. Instead of using broad terms like "high" or "low" like in the current prompt, we question whether incorporating more specific metrics to describe these attributes would enable the model to better tailor texts. To quantify reading skill, standardized test scores were used as indicators. For instance, the ACT English composite score (32/36; 96th percentile) and ACT Reading composite score (31/36; 94th percentile) is included to demonstrate a high-skilled reader. A reader profile with low science prior knowledge is represented by ACT Math (18/36; 42nd percentile) and ACT Science percentile ranking (19/36; 46th percentile). Description in the profile includes additional information like "Completed one high-school level biology course, with no advanced science coursework, and limited exposure to scientific concepts." By including standardized test scores and quantifiable metrics representing reading proficiency and science knowledge, the LLMs might improve their performance.

Secondly, we integrated Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to enhance the contextual relevance of outputs by grounding the LLMs' responses in empirical findings. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is a framework that enhances the accuracy and contextual relevance of output by incorporating an external knowledge base during the text generation process [

40,

41]. The documents provided to the LLMs were research papers regarding established theoretical frameworks in reading comprehension, text readability, and individual differences. Specifically, in our prompt, the LLMs were instructed to retrieve and utilize research papers as guidelines for modifying content. The RAG approach utilized here involves content-grounded referencing in which the retrieved empirical and theoretical documents serve as contextual frameworks to guide the modifications implicitly. The documents guide the adaptation process implicitly rather than through explicit textual referencing. Integrating research articles into the LLMs’ knowledge base helps guide the modification process, which helps the LLMs to align linguistic features to reader abilities. The LLM integrates insights by tailoring text features to align with established cognitive science principles, without referencing the documents directly.

Two additional techniques were also incorporated in the new prompt:

chain-of-thought and

personification. Personification involves instructing the LLMs to adopt a role aligned with the task’s objectives which leverages its ability to simulate human-like reasoning [

41,

42]. Chain-of-thought involves instructing the model to explain its reasoning process step-by-step. Prior research has shown that making the reasoning process transparent can enhance LLM performance, accuracy and consistency since it breaks down tasks into smaller parts, resulting in coherent and logical responses. Outlining steps and rationales also helps researchers identify errors and refine prompts.

Prompting plays a critical role in the response quality and making the prompt more detailed and structured enhances task performance. As such, in the second experiment, we used NLP to evaluate the improvement in modification generated using the augmented prompt. By analyzing linguistic features, we assess the alignment between modifications and readers’ unique needs and abilities. The four hypothetical reader profiles in Study 1 were modified to be more detailed and structured, following the example in

Table 6. The revised prompts were evaluated using the same 10 scientific texts from Study 1. Unlike Experiment 1, which compared multiple LLMs, Experiment 2 focused on examining the effect of augmented prompting strategies using Gemini to isolate the variability from other LLMs. The augmented prompts were tested on the same 10 scientific texts and modifications were analyzed using NLP tools to extract linguistic features such as cohesion, lexical complexity, and sentence structure. The NLP analyses were used to assess whether the augmented prompt led to improvements in text alignment with different reader profiles. By demonstrating how NLP tools can assess suitability between textual features and reader characteristics, this study proposes a scalable solution for evaluating text personalization.

7. Materials and Methods

7.1. LLM Selection

In the second experiment, we refined the prompting process to improve text personalization and focused on performance of Gemini. Gemini was selected for Experiment 2 because its modifications closely resembled those of ChatGPT in terms of conceptual depth but provided more engaging and cohesive outputs. See Appendix 1 for details (e.g., versions, dates of usage, training size and parameters).

7.2. Text Corpus

Ten expository texts from Experiment 1 were used for this experiment. See

Table 1 for information about the texts.

7.3. Reader Profile

Four hypothetical reader profiles created for Study 1 were modified to improve the structure and level of specificity. These enhancements aimed to provide LLMs with clear and more context about the profiles. For instance, standardized test scores (e.g., ACT composite scores in English, Reading, Math, and Science) were included which quantified readers’ proficiency levels. Statements about readers’ academic backgrounds and exposure to scientific concepts further clarified each profile’s prior knowledge and topic familiarity.

Table 7 provides the comprehensive descriptions of these enhanced reader profiles.

7.4. Procedure

The goal of Experiment 2 was to enhance prompt clarity and structure to improve the alignment between LLM-generated modifications and the unique needs of diverse reader profiles. Gemini was prompted with the augmented prompt to modify ten scientific texts to suit the four revised reader profiles (See

Appendix C). Each generation iteration involved ten modifications for each reader profile. In total, there were 40 modifications for four reader profiles. Each modified text was systematically analyzed using WAT to extract linguistic features related text readability such as cohesion, lexical complexity, syntax complexity, academic writing style, and idea elaboration.

Table 1 describes each linguistic feature included in the analysis. These features provided quantitative validation metrics to assess the extent to which the augmented prompt improved the alignment between text modifications and reader profiles. The linguistic features of modifications generated by Gemini from Experiment 1 were used to compare across the two prompts.

8. Results

To examine to what extent the augmented prompts improved alignment between linguistic features and reader’s need, a two-way ANOVA (4 Reader Profiles: High PK/ High RS, High PK/ Low RS, Low PK/ High RS, Low PK/ Low RS x 2 Prompt Types: Single-shot vs. Augmented). There was a significant two-way interaction effect between Reader Profile and Prompt, suggesting that the impact of the augmented prompt on linguistic features of modified texts varied depending on the reader profiles.

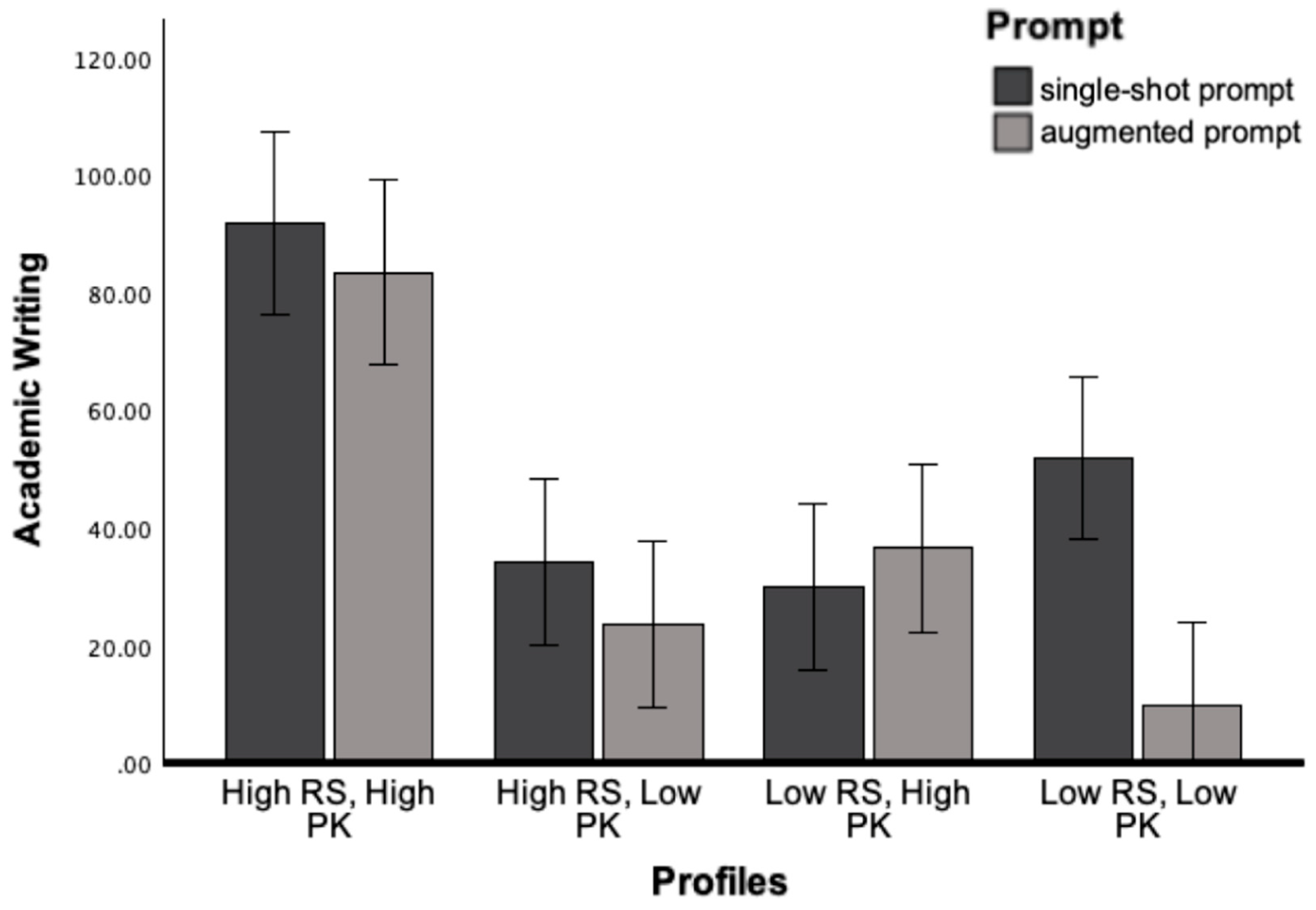

8.1. Academic Writing

The interaction effects between Prompt and Profile were significant, F (3, 240) = 10.45, p<.001, η2 = .12. As intended, the results showed that Academic Writing was significantly lower for texts modified for low-skill and low-knowledge readers using the augmented prompt compared to the single-shot prompt (p<.001). See Figure 3 for main effect of prompt and reader profiles on Academic Writing.

Figure 1.

Academic Writing as a Function of Prompt and Reader Profile.

Figure 1.

Academic Writing as a Function of Prompt and Reader Profile.

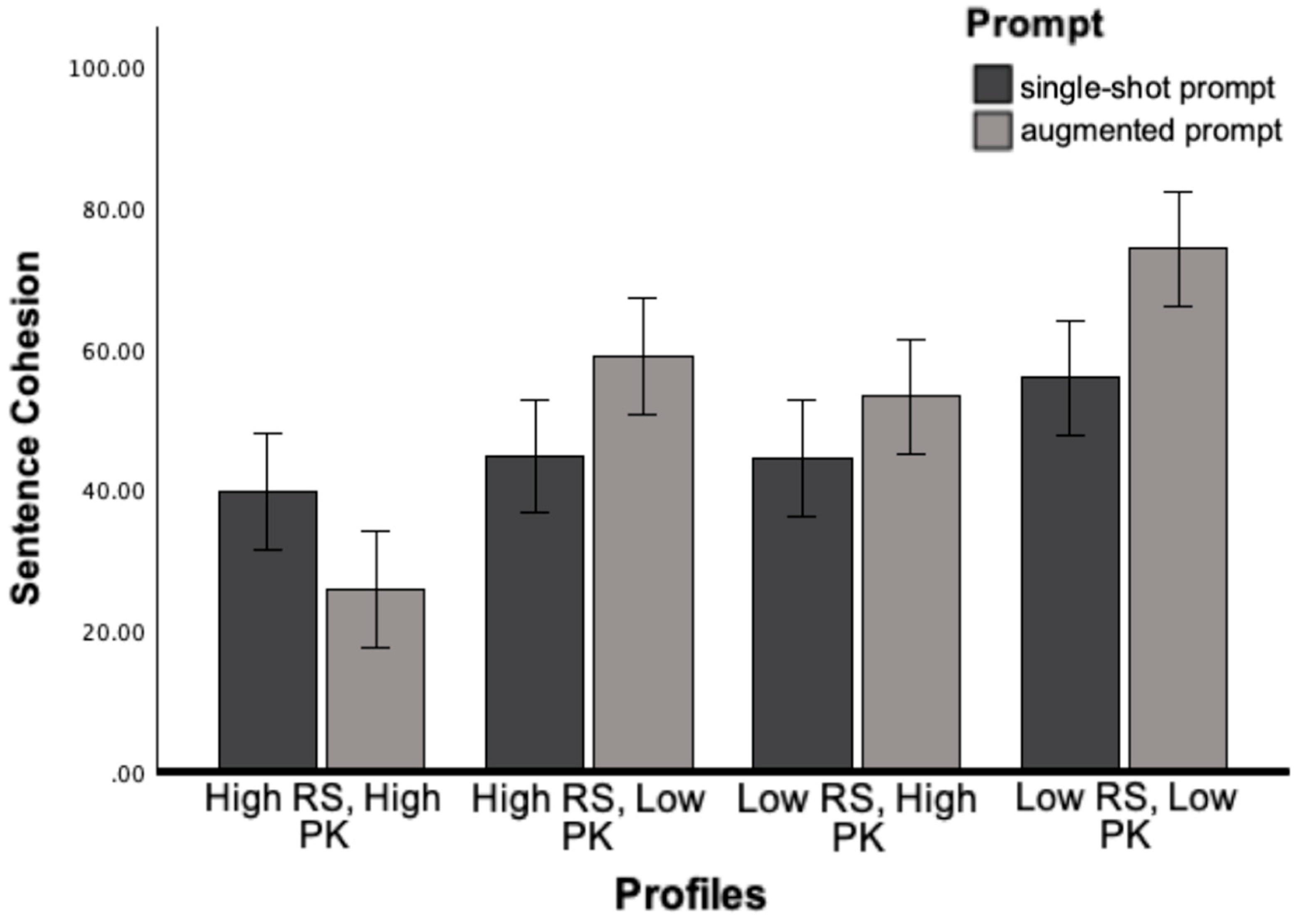

8.2. Conceptual Density and Cohesion

The interaction effect between Prompt and Profile was significant for cohesion, F (3, 240) = 6.18, p<.001, η2 = .07. As predicted, Cohesion was significantly lower for texts modified for high-skill and high-knowledge readers using augmented prompt (p=.02) and were significantly higher for less-skill and low-knowledge readers (p<.05).

Figure 4.

Sentence Cohesion as a Function of Prompt and Reader Profile.

Figure 4.

Sentence Cohesion as a Function of Prompt and Reader Profile.

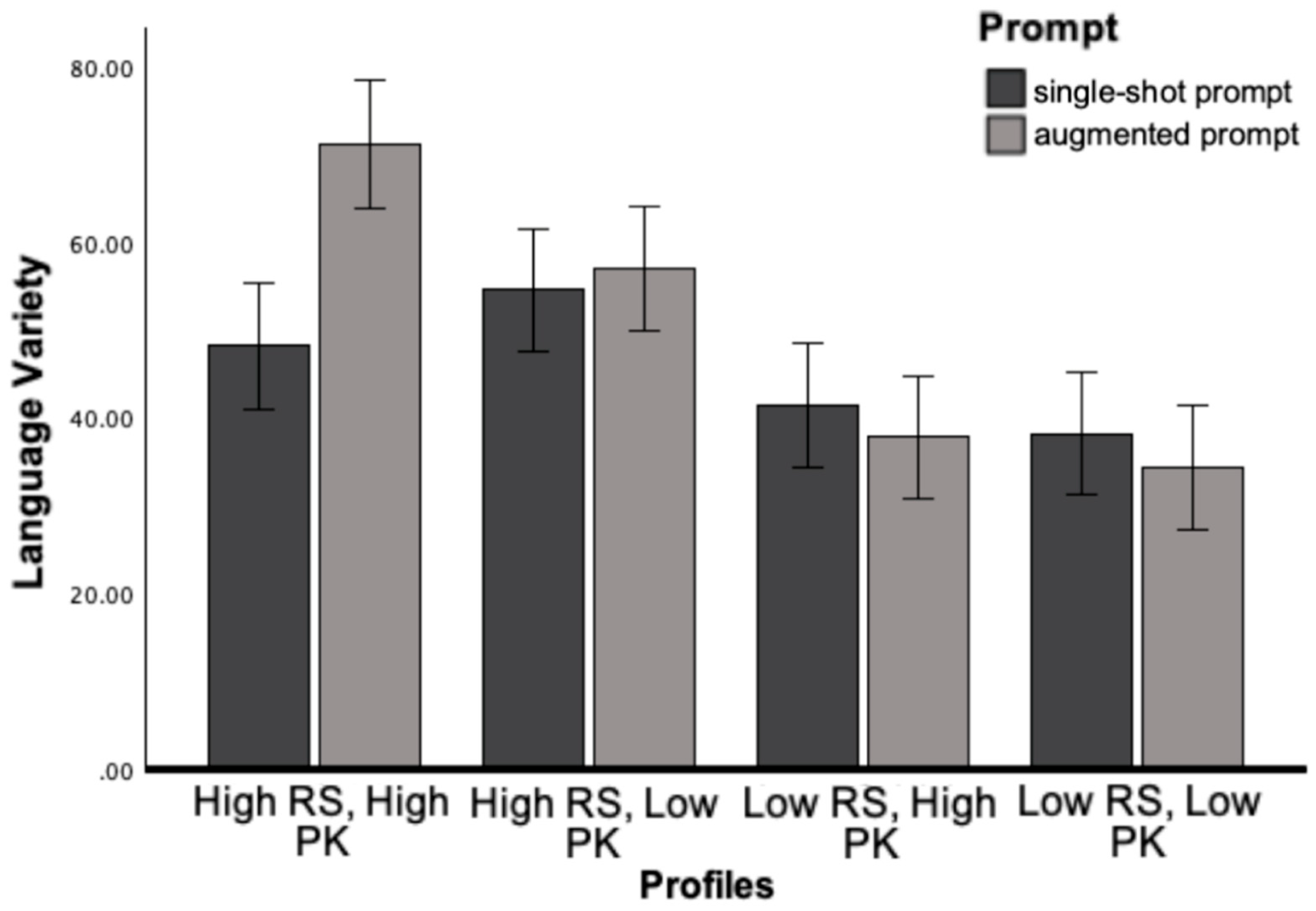

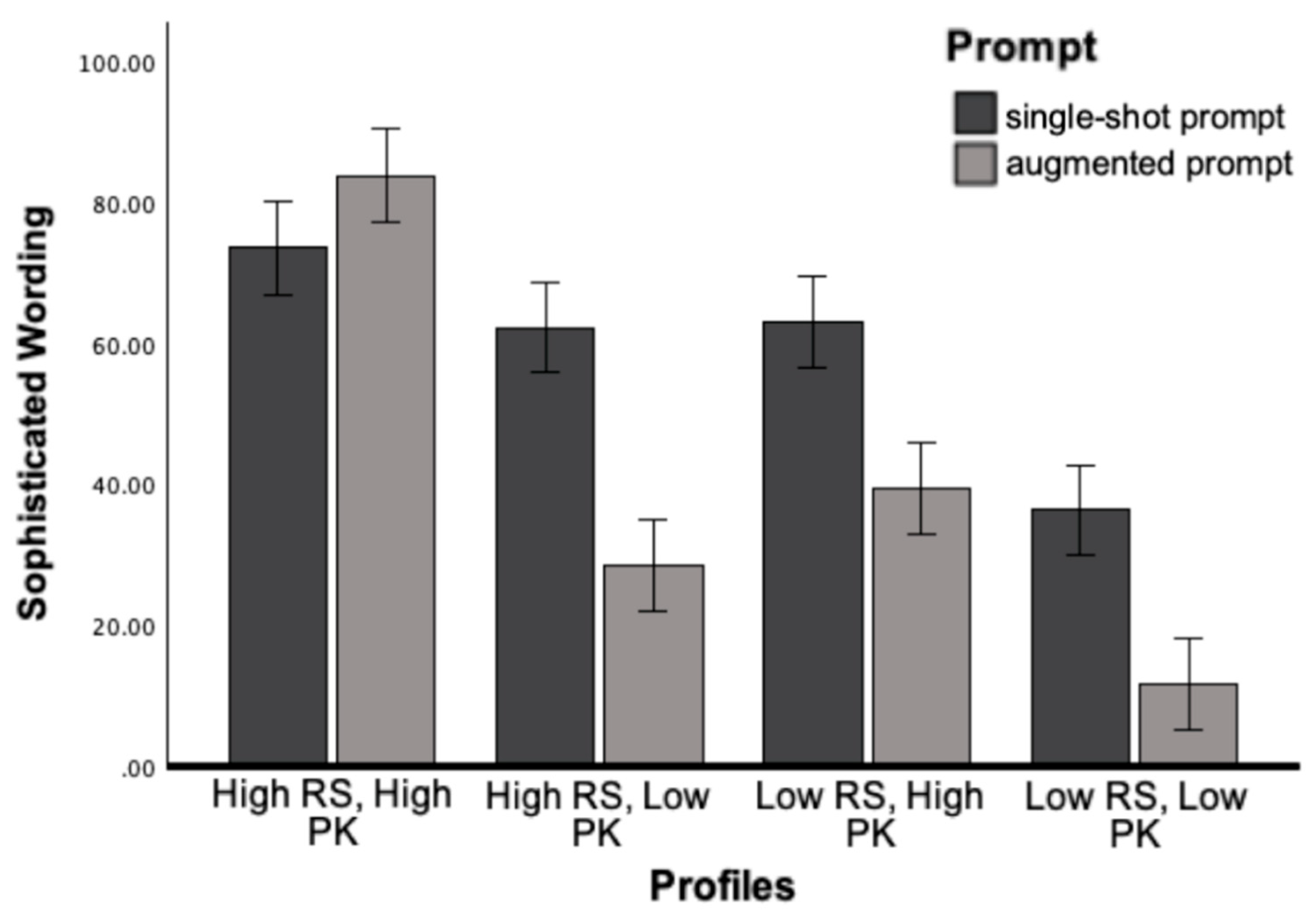

8.3. Syntactic and Lexical Complexity

The interaction effect between Prompt and Profile was significant for Language variety, F (3, 240) = 6.24, p<.001, η2 = .08, and Sophisticated Wording, F (3, 240) = 17.44, p<.001, η2 = .19. As intended, modifications generated by augmented prompt for high knowledge and high skill profiles significantly increased in language variety and sophisticated wording. In contrast, modifications for low knowledge or low skill profiles significantly decreased in lexical sophistication, aligning with the hypothesized difficulty levels for each profile.

Figure 1.

Academic Writing as a Function of Prompt and Reader Profile.

Figure 1.

Academic Writing as a Function of Prompt and Reader Profile.

Figure 1.

Academic Writing as a Function of Prompt and Reader Profile.

Figure 1.

Academic Writing as a Function of Prompt and Reader Profile.

9. Experiment 2 Discussion

NLP analyses provided quantifiable evidence suggesting that the augmented prompt effectively tailored linguistic features to suit different reader needs. Linguistic features were more appropriately aligned to reader needs based on evidence-based text modifications in reading comprehension research. Specifically, texts for high-skill, high-knowledge profiles had increased syntax and lexical sophistication and reduced cohesion, which promotes active processing and deep comprehension [

11,

26,

37]. In contrast, low-skill and low-knowledge profiles benefited from simpler syntax, common vocabulary, and more cohesive modifications that facilitated comprehension. Simplifying language and using familiar words improve readability and ease of understanding for these readers. The results of Experiment 2 suggested that NLP was able to provide objective measures that can illustrate how prompt refinements led to effective text personalization.

10. General Discussion

In these two experiments, we leveraged LLMs to modify text for different readers and used linguistic features to evaluate the LLM-generated modifications. Experiment 1 showed that LLMs varied in how they adapt text readability to align with readers’ characteristics, which was evidenced in variations of linguistic features related to text difficulty. In Experiment 2, NLP analyses illustrated how the augmented prompt enhances text personalization. These prompt refinements resulted in better aligned text readability. These findings established how automated text analysis can be applied to evaluate the effectiveness of text modifications for different readers. As such, NLP can analyze linguistic features to determine whether modified texts align with readers’ needs.

This study further demonstrates the benefits of augmenting information provided to the LLMs using various techniques (e.g., personification, chain-of-thought, RAG). Generative AI can be leveraged to quickly modify content: there is little doubt that LLMs can generate revised versions of content based on human instructions. However, the dilemma is that there have been few attempts (if any), other than intuition, to validate modifications of content using generative AI. This study demonstrates how NLP can provide real-time assessment regarding the extent to which content is appropriately tailored to students’ needs and abilities. As a result, it allows for iterative refinements to increase the likelihood that the LLM will generate content aligned with expectations. Modifications can be adjusted based on quantitative analyses and further improved without requiring costly and time-consuming studies with human participants. By quickly tailoring text features with individual needs and validating the content, NLP validation approaches have the potential to enhance personalized learning, particularly when there is substantial evidence to inform hypotheses, as in the case of the impact of the linguistic and semantic features of text.

Limitations & Future Direction

In the current research, only four reader profiles were used for generating LLM-adapted texts. While this number provided sufficient proof-of-concept for exploring personalized adaptations and demonstrating the capabilities of NLP methods in evaluating personalized content, the limited number of profiles potentially constrains the generalizability of our findings. Specifically, the reader profiles might not capture the full complexity and range of individual differences in a diverse student population. Additional characteristics such as interests, motivation, cultural backgrounds, learning disabilities beyond dyslexia, or cognitive characteristics were not sufficiently represented in these profiles [

43,

44,

45]. To accurately personalize and evaluate educational materials, it is essential to capture these broader individual differences beyond reading skills and prior knowledge [

46]. Future research should explore more nuanced reader characteristics and incorporate a more diverse set of reader profiles to improve external validity. In addition, it would be beneficial to test on a larger and more diverse text domains.

Another limitation of these two experiments is that each text was prompted to be modified only once for each reader profile. LLMs are inherently non-deterministic, and each iteration can produce varying outputs even when using the same prompts [

47]. The variability in responses across identical prompts even within the same model is particularly problematic especially when they are used for educational tasks that require consistency [

48]. As such, conducting single-run trials limits the ability to capture and quantify this internal variability. Future research can systematically analyze repeated text generations to examine reliability and consistency across LLM outputs.

The NLP-validation approach facilitates automated evaluations, enabling modifications to be rapidly tested, refined through quantitative feedback, and adapted accordingly. As such, it’s beneficial to also explore how personalized content dynamically evolve to match students’ changing knowledge, interests, and skills over time. While NLP measures provide efficient and objective indicators of text personalization quality, future research can conduct usability testing with students to examine impact of LLMs adaptation on academic performance and engagement.

11. Conclusion

The novel contribution of this research is the demonstration of an automated NLP-based validation method that systematically and iteratively assess GenAI-modified educational texts. Unlike traditional human assessment, which is resource-intensive and time-consuming, leveraging NLP provides a scalable and efficient validation process. Specifically, NLP metrics objectively quantify text complexity and readability, allowing for immediate feedback loops that support rapid iteration and content refinement. In the two experiments, NLP provided objective and quantifiable evidence to evaluate linguistic alignment between LLM-generated modifications and readers' individual needs. Experiment 1 illustrated that LLMs varied in their capacity to adjust readability appropriately for different reader profiles. Experiment 2 demonstrated how augmented prompting techniques improved alignment with readers' characteristics, further emphasizing the effectiveness of iterative refinements using NLP feedback.

NLP-validation approach supports continuous and iterative refinements to enhance personalization. After initial LLM outputs are analyzed, subsequent iterations can integrate NLP-generated. This data-driven iterative cycle allows the system to continuously and dynamically adapt educational content as learners' skills and knowledge evolve, significantly enhancing personalized learning experiences over time. The current study highlighted NLP validation approach as a scalable, real-time and practical evaluation tool for validating personalized educational contents efficiently. Automated NLP validation can be applied to create adaptive, personalized learning environments that evolve in response to learner growth.

Funding

The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305T240035 to Arizona State University. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PK |

Prior knowledge |

| RS |

Reading skills |

| GenAI |

Generative AI |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

Appendix A. LLM Descriptions

Claude 3.5 Sonnet (Anthropic)

Version Used: Claude 3.5

Date Accessed: August 31, 2024

Accessed via Poe.com web deployment, default configurations were used

Training Size: Claude is trained on a large-scale, diverse dataset derived from a broad range of online and curated sources. The exact size of the training data remains proprietary.

Number of Parameters: The exact number of parameters for Claude 3.5 is not disclosed by Anthropic, but it is estimated to be between 70–100 billion parameters.

Llama (Meta)

Version Used: Llama 3.1

Date Accessed: August 31, 2024

Accessed via Poe.com web deployment, default configurations were used

Llama 3.1 was trained on 2 trillion tokens sourced from publicly available datasets, including books, websites, and other digital content.

Number of Parameters: Llama 3.1 consists of 70 billion parameters.

Gemini Pro 1.5 (Google DeepMind)

Version Used: Gemini Pro 1.5

Date Accessed: August 31, 2024

Accessed via Poe.com web deployment, default configurations were used

Training Size: Gemini is trained on 1.5 trillion tokens, sourced from a wide variety of publicly available and curated data, including text from books, websites, and other large corpora.

Number of Parameters: Gemini 1.0 operates with 100 billion parameters.

ChatGPT (OpenAI)

Version Used: GPT-4o

Date Accessed: August 31, 2024

Accessed via Poe.com web deployment, default configurations were used

Training Size: GPT-4 was trained on an estimated 1.8 trillion tokens from diverse sources, including books, web pages, academic papers, and large text corpora.

Number of Parameters: The exact number of parameters for GPT-4 is not publicly disclosed, but in the range of 175 billion parameters.

Appendix B. Single-Shot Prompt Experiment 1

Modify the text to improve comprehension and engagement for a reader. The goal of this personalization task is to tailor materials that aligns with the unique characteristics of the reader (age, background knowledge, reading skills, reading goal and preferences, interests) while maintaining content coverage and important terms/ concepts from the original text. Follow these steps:

Analyze the input text and determine its reading level (e.g., Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level), linguistic complexity (e.g., sentence length, vocabulary), and the assumed background knowledge required for comprehension.

Analyze the reader profile and identify key information: Age, Reading Level (e.g., beginner, intermediate, advanced), Prior Knowledge (specific knowledge related to the text's topic), Reading Goals (e.g., learn new concepts, enjoyment, research, pass an exam), Interests (what topics or themes are motivating for the reader?), Accessibility Needs (specify any learning disabilities or preferences that require text adaptations, dyslexia, visual impairments).

Reorganize information, modify the syntax, vocabulary, and tone to tailor to the reader's characteristics.

If the reader has less knowledge about the topic, then provide sufficient background knowledge or relatable examples and analogies to support comprehension and engagement. If the reader has strong background knowledge and high reading skill, then increase depth of information and avoid overly explaining details.

[Insert Reader 1 Description]

[Insert Text]

Appendix C. Augmented Prompt Experiment 2

References

- Abbes, F.; Bennani, S.; Maalel, A. Generative AI and gamification for personalized learning: Literature review and future challenges. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Ramos, A.; Moreno, L. Exploring large language models to generate easy-to-read content. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 6, 1394705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, L.; Francis, G.A.; Tsapali, M. The effectiveness of technology-supported personalized learning in low- and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1935–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, D.S.; Levinstein, I.B.; Boonthum, C. : iSTART: Interactive strategy training for active reading and thinking. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, E.; Jones, A.; Kucirkova, N.; Scanlon, E. : A literature synthesis of personalised technology-enhanced learning: What works and why. Res. Learn. Technol. 2018, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, J.; Pataranutaporn, P.; Danry, V.; Perteneder, F.; Mao, Y.; Maes, P.: Putting things into context: Generative AI-enabled context personalization for vocabulary learning improves learning motivation. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2024, 1–15.

- McNamara, D.S. : Chasing theory with technology: A quest to understand understanding. Discourse Process. 2021, 58, 422–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, S.A., Skalicky, S., Dascalu, M., McNamara, D., Kyle, K. Predicting text comprehension, processing, and familiarity in adult readers: New approaches to readability formulas. Discourse Processes 2017, 54(1), 1–20.

- Crossley, S.A., Skalicky, S., McNamara, D.S., Paquot, M. Large-scale crowdsourcing of human judgments of text difficulty: A methodology for collecting reliable data. Behavior Research Methods 2023, 1–20.

- McNamara, D.S. , Louwerse, M.M., McCarthy, P.M., Graesser, A.C. Coh-Metrix: Capturing linguistic features of cohesion. Discourse Processes 2010, 47(4), 292–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, D.S. Reading both high-coherence and low-coherence texts: Effects of text sequence and prior knowledge. Discourse Processes 2001, 31(1), 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natriello, G. The adaptive learning landscape. Teachers College Record 2017, 119(3), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Boulay, B., Poulovassilis, A., Holmes, W., Mavrikis, M. What does the research say about how artificial intelligence and big data can close the achievement gap? In R. Luckin (Ed.) Enhancing Learning and Teaching with Technology: What the Research Says 2018, pp. 256–285.

- Kucirkova, N. Personalised learning with digital technologies at home and school: Where is children's agency. In Mobile Technologies in Children's Language and Literacy: Innovative Pedagogy in Preschool and Primary Education; Oakley, G., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mesmer, H.A.E. Tools for Matching Readers to Texts: Research-Based Practices, 1st ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1–234. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, C.; Burdick, H. The Lexile Framework as an approach for reading measurement and success. Available online: https://metametricsinc.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Lexile-Framework-for-Reading.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Stenner, A.J.; Burdick, H.; Sanford, E.E.; Burdick, D.S. How accurate are Lexile text measures. J. Appl. Meas. 2007, 8, 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Pesovski, T.; Dorr, M.; Thoms, B. AI-generated personalized learning materials: Improving engagement and comprehension in learning management systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Technology, Virtual, Switzerland, 12 March 2024; pp. 112–124.

- Dunn, T.J.; Kennedy, M. Technology-enhanced learning in higher education: Motivators and demotivators of student engagement. Comput. Educ. 2019, 129, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sonia, A.N.; Magliano, J.P.; McCarthy, K.S.; Creer, S.D.; McNamara, D.S.; Allen, L.K. Integration in multiple-document comprehension: A natural language processing approach. Discourse Process. 2022, 59, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.K.; Creer, S.C.; Öncel, P. Natural language processing as a tool for learning analytics—Towards a multi-dimensional view of the learning process. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in Education Conference (AIED 2022), Durham, UK, 27–31 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, S.A.; Allen, L.K.; Snow, E.L.; McNamara, D.S. Incorporating learning characteristics into automatic essay scoring models: What individual differences and linguistic features tell us about writing quality. J. Educ. Data Min. 2016, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, S.A.; Kim, M.; Allen, L.; McNamara, D.S. Automated summarization evaluation (ASE) using natural language processing tools. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2019), Chicago, IL, USA, 25–29 June 2019; pp. 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.K.; Graesser, A.C.; McNamara, D.S. Automated analyses of natural language in psychological research. Trends Psychol. Sci. 2023. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, D.S.; Graesser, A.C.; McCarthy, P.M.; Cai, Z. Automated Evaluation of Text and Discourse with Coh-Metrix, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 1–312. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, T.; McNamara, D.S. Reversing the reverse cohesion effect: Good texts can be better for strategic, high-knowledge readers. Discourse Process. 2007, 43, 121–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, W.; Townsend, D. Words as tools: Learning academic vocabulary as language acquisition. Read. Res. Q. 2012, 47, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C.E. Academic language and the challenge of reading for learning about science. Science 2010, 328, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, R.S.; Starr, L.E.; Bailey, A.L. Syntactic complexity as an aspect of text complexity. Educ. Res. 2015, 44, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, J.P.; Millis, K.K. Assessing reading skill with a think-aloud procedure. Cogn. Instr. 2004, 21, 251–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, T.; McCarthy, K.S.; McNamara, D.S. iSTART StairStepper—Using comprehension strategy training to game the test. Computers 2021, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perret, C.A.; Johnson, A.M.; McCarthy, K.S.; Guerrero, T.A.; McNamara, D.S. StairStepper: An adaptive remedial iSTART module. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2017), Wuhan, China, 28 June–2 July 2017; pp. 557–560. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Creer, S.D.; Arner, T.; Roscoe, R.D.; Allen, L.K.; McNamara, D.S. Participatory design of a writing analytics tool: Teachers’ needs and design solutions. In Companion Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (LAK22).

- Öncel, P.; Flynn, L.E.; Sonia, A.N.; Barker, K.E.; Lindsay, G.C.; McClure, C.M.; McNamara, D.S.; Allen, L.K. Automatic student writing evaluation: Investigating the impact of individual differences on source-based writing. In Proceedings of the 11th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference (LAK21), CA, USA, 2021, ACM: Irvine; pp. 260–270.

- Potter, A.; Shortt, M.; Goldshtein, M.; Roscoe, R.D. Assessing academic language in tenth-grade essays using natural language processing. Assess. Writ. in press, pp. 1–13.

- Beck, I.L.; McKeown, M.G.; Sinatra, G.M.; Loxterman, J.A. Revising social studies text from a text-processing perspective: Evidence of improved comprehensibility. Read. Res. Q. 1991, 26, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuru, Y.; Dempsey, K.; McNamara, D.S. Prior knowledge, reading skill, and text cohesion in the comprehension of science texts. Learn. Instr. 2009, 19, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.; Rastogi, A.; Rao, A.; Shoeb, A.A.M.; Abid, A.; Fisch, A.; Wang, G. Beyond the imitation game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.04615. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, P.; Singh, A.K.; Saha, S.; Jain, V.; Mondal, S.; Chadha, A. A systematic survey of prompt engineering in large language models: Techniques and applications. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.07927. [Google Scholar]

- Bisk, Y.; Zellers, R.; Bras, R.L.; Gao, J.; Choi, Y. Experience grounds language. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10151. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, N.; Engle, R.W. The nature of individual differences in working memory capacity: Active maintenance in primary memory and controlled search from secondary memory. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.M.; Lyon, G.R.; Fuchs, L.S.; Barnes, M.A. Learning Disabilities: From Identification to Intervention, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: Aka the remix. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2014, 84, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog 2019. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/better-language-models (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Dornburg, A.; Davin, K. To what extent is ChatGPT useful for language teacher lesson plan creation? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.09974. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

Linguistic Features related to text readability.

Table 1.

Linguistic Features related to text readability.

| Features |

Metrics and Descriptions |

| Overall Readability |

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL): Indicates text difficulty based on sentence length and word length

Academic writing: The extent to which the texts include domain-specific words and sophisticated sentence structures, commonly found in academic writing texts

Development of ideas: The extent to which ideas and concepts are developed and elaborated throughout a text. |

| Conceptual Density and Cohesion |

Noun to verb ratio: Text with a high noun-to-verb ratio results in dense information and complex sentences that require greater cognitive effort to process

Sentence cohesion: The extent to which the text contains connectives, and cohesion cues (e.g., repeating ideas, concepts). |

| Syntax Complexity |

Sentence length: Longer sentences often have more clauses and complex structure

Language variety: Indicates the extent to which text varies in the language used (sentence structures, wordings) |

| Lexical Complexity |

Sophisticated wording: Lower measures indicate the vocabulary familiar and common, whereas higher measures indicate more advanced words.

Academic frequency: Indicates the extent of sophisticated vocabulary are used, which are also common in academic texts |

Table 2.

Scientific Texts.

Table 2.

Scientific Texts.

| Domain |

Text Title |

Word Count |

FKGL1

|

| Biology |

Bacteria |

468 |

12.10 |

| Biology |

The Cells |

426 |

11.61 |

| Chemistry |

Chemistry of Life |

436 |

12.71 |

| Biology |

Genetic Equilibrium |

441 |

12.61 |

| Biology |

Food Webs |

492 |

12.06 |

| Biology |

Patterns of evolution |

341 |

15.09 |

| Biology |

Causes and Effects of Mutations |

318 |

11.35 |

| Physics |

What are Gravitational Waves? |

359 |

16.51 |

| Biochemistry |

Photosynthesis |

427 |

11.44 |

| Biology |

Microbes |

407 |

14.38 |

Table 3.

Descriptions of Various Reader Profiles Provided to the LLMs.

Table 3.

Descriptions of Various Reader Profiles Provided to the LLMs.

Table 4.

Hypothesized Linguistic Features of Adapted Texts Aligned to Reader Profiles.

Table 4.

Hypothesized Linguistic Features of Adapted Texts Aligned to Reader Profiles.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics and Main Effects of Reader Profiles.

Table 5.

Descriptive Statistics and Main Effects of Reader Profiles.

Table 6.

Descriptive Statistics and Main Effects of Reader Profiles.

Table 6.

Descriptive Statistics and Main Effects of Reader Profiles.

Table 7.

Descriptions of Various Reader Profiles Provided to the LLMs.

Table 7.

Descriptions of Various Reader Profiles Provided to the LLMs.

| |

Descriptions |

| Reader 1 (High RS, High PK) |

Age: 25

Educational level: Senior

Major: Chemistry (Pre-med)

ACT English composite score: 32/36 (performance is in the 96th percentile)

ACT Reading composite score: 32/36 (performance is in the 96th percentile)

ACT Math composite score: 28/36 (performance is in the 89th percentile)

ACT Science composite score: 30/36 (performance is in the 94th percentile)

Science background: Completed 8 required biology, physics and chemistry college-level courses (comprehensive academic background in the sciences, covering advanced topics in biology, chemistry, and physics, well-prepared for higher-level scientific learning and analysis)

Reading goal: Understand scientific concepts and principles |

| Reader 2 (High RS, Low PK) |

Age: 20

Educational level: Sophomore

Major: Psychology

ACT English composite score: 32/36 (performance is in the 96th percentile)

ACT Reading composite score: 31/36 (performance is in the 94th percentile)

ACT Math composite score: 18/36 (performance is in the 42th percentile)

ACT Science composite score: 19/36 (performance is in the 46th percentile)

Science background: Completed 1 high-school level chemistry course (no advanced science course). Limited exposure and understanding of scientific concepts

Interests/ Favorite subjects: arts, literature

Reading goal: Understand scientific concepts and principles |

| Reader 3 (Low RS, High PK) |

Age: 20

Educational level: Sophomore

Major: Health Science

ACT English composite score: 19/36 (performance is in the 44th percentile)

ACT Reading composite score: 20/36 (performance is in the 47th percentile)

ACT Math composite score: 32/36 (performance is in the 97th percentile)

ACT Science composite score: 30/36 (performance is in the 94th percentile)

Science background: Completed 1 physics, 1 astronomy and 2 college level biology courses (substantial prior knowledge in science, having completed multiple college-level courses across several disciplines, strong foundation in scientific principles and concepts)

Reading goal: Understand scientific concepts

Reading disability: Dyslexia |

| Reader 4 (Low RS, Low PK) |

Age: 18

Educational level: Freshman

Major: Marketing

ACT English composite score: 17/36 (performance is in the 33rd percentile)

ACT Reading composite score: 18/36 (performance is in the 36th percentile)

ACT Math composite score: 19/36 (performance is in the 48th percentile)

ACT Science composite score: 17/36 (performance is in the 34th percentile)

Science background: Completed 1 high-school level biology course (no advanced science course). Limited exposure and understanding of scientific concepts

Reading goal: Understand scientific concepts |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).