Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients, Samples, and Diagnosis of Yellow Fever Infection

2.2. Ethics Statement

2.3. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.4. Quantitative Analysis and Photo-Documentation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Clarification of Initials

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YFV | Yellow fever virus |

| NC | Negative control |

| FFPE | Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded |

| HPF | High-power field |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| PT | Portal tract |

| Z1/Z2/Z3 | Periportal/Midzonal/Centrilobular zones |

| BECLIN-1 | Autophagy initiation marker |

| RIP3 | Receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IL-1β/IL-18/IL-33 | Interleukins 1β/18/33 |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Gardner, C.L.; Ryman, K.D. Yellow fever: A reemerging threat. Clin. Lab. Med. 2010, 30, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elton, N.W. Yellow fever in Panama; historical and contemporary. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1952, 1, 436–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, F.V.S.; Ribeiro, I.P.; Ferreira-de-Brito, A.; Santos, A.A.C.D.; Miranda, R.M.; Bonelly, I.S.; Neves, M.S.A.S.; Bersot, M.I.; Santos, T.P.D.; Gomes, M.Q.; Silva, J.L.D.; Romano, A.P.M.; Carvalho, R.G.; Said, R.F.D.C.; Ribeiro, M.S.; Laperrière, R.D.C.; Fonseca, E.O.L.; Falqueto, A.; Paupy, C.; Failloux, A.-B.; Moutailler, S.; Castro, M.G.; Gómez, M.M.; Motta, M.A.; Bonaldo, M.C.; Lourenço-de-Oliveira, R. Haemagogus leucocelaenus and Haemagogus janthinomys are the primary vectors in the major yellow fever outbreak in Brazil, 2016–2018. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waggoner, J.J.; Rojas, A.; Pinsky, B.A. Yellow fever virus: Diagnostics for a persistent arboviral threat. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e00827–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faggioni, G.; De Santis, R.; Moramarco, F.; Di Donato, M.; De Domenico, A.; Molinari, F.; Petralito, G.; Fortuna, C.; Venturi, G.; Rezza, G.; Lista, F. Pan-yellow fever virus detection and lineage assignment by real-time RT-PCR and amplicon sequencing. J. Virol. Methods 2023, 316, 114717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monath, T.P.; Barrett, A.D. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of yellow fever. Adv. Virus Res. 2003, 60, 343–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, C.V.; Free, R.J.; Bhatnagar, J.; Soto, R.A.; Royer, T.L.; Maley, W.R.; Moss, S.; Berk, M.A.; Craig-Shapiro, R.; Kodiyanplakkal, R.P.L.; Westblade, L.F.; Muthukumar, T.; Puius, Y.A.; Raina, A.; Hadi, A.; Gyure, K.A.; Trief, D.; Pereira, M.; Kuehnert, M.J.; Ballen, V.; Kessler, D.A.; Dailey, K.; Omura, C.; Doan, T.; Miller, S.; Wilson, M.R.; Lehman, J.A.; Ritter, J.M.; Lee, E.; Silva-Flannery, L.; Reagan-Steiner, S.; Velez, J.O.; Laven, J.J.; Fitzpatrick, K.A.; Panella, A.; Davis, E.H.; Hughes, H.R.; Brault, A.C.; St George, K.; Dean, A.B.; Ackelsberg, J.; Basavaraju, S.V.; Chiu, C.Y.; Staples, J.E. ; Yellow Fever Vaccine Virus Transplant and Transfusion Investigation Team. Transmission of yellow fever vaccine virus through blood transfusion and organ transplantation in the USA in 2021: Report of an investigation. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e711–e721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Wu, B.; Tang, H.; Luo, Z.; Xu, Z.; Ouyang, S.; Li, X.; Xie, J.; Yi, Z.; Leng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Z.; Zhao, P. Rifapentine is an entry and replication inhibitor against yellow fever virus both in vitro and in vivo. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Di, T.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Qu, J.; Hua, W.; Li, C.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, R.; Wang, Q; Chen, L. ; Wang, S. ; Pang, X.; Liang, M.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Li, D. A fatal yellow fever virus infection in China: Description and lessons. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2016, 5, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.S.; Júnior, P.S.B.; Cerqueira, V.D.; Rivero, G.R.C.; Júnior, C.A.O.; Castro, P.H.G.; Silva, G.A.D.; Silva, W.B.D.; Imbeloni, A.A.; Sousa, J.R.; Araújo, A.P.S.; Silva, F.A.E.; Tesh, R.B.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Vasconcelos, P.F.D.C. Experimental yellow fever virus infection in the squirrel monkey (Saimiri spp.) I: Gross anatomical and histopathological findings in organs at necropsy. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e190501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E.A.; LaFond, R.E.; Gates, T.J.; Mai, D.T.; Malhotra, U.; Kwok, W.W. Yellow fever vaccination elicits broad functional CD4+ T cell responses that recognize structural and nonstructural proteins. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 12794–12804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.T.; Ols, S.; Löfling, M.; Varnaitė, R.; Lindgren, G.; Nilsson, O.; Rombo, L.; Kalén, M.; Loré, K.; Blom, K.; Ljunggren, H.G. Activation and kinetics of circulating T follicular helper cells, specific plasmablast response, and development of neutralizing antibodies following yellow fever virus vaccination. J. Immunol. 2021, 207, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.P.; Matos, D.C.S.; Bertho, A.L.; Mendonça, S.C.F.; Marcovistz, R. Detection of Th1/Th2 cytokine signatures in yellow fever 17DD first-time vaccinees through ELISpot assay. Cytokine 2008, 42, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.; Duarte, M.I.; Vasconcelos, P.F. Midzonal lesions in yellow fever: A specific pattern of liver injury caused by direct virus action and in situ inflammatory response. Med. Hypotheses 2006, 67, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.; Barros, V.L.; Pagliari, C.; Fernandes, E.R.; Guedes, F.; Takakura, C.F.; Andrade, H.F., Jr.; Vasconcelos, P.F.; Duarte, M.I. Revisiting the liver in human yellow fever: Virus-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes associated with TGF-beta, TNF-alpha and NK cells activity. Virology 2006, 345, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olímpio, F.A.; Falcão, L.F.M.; Carvalho, M.L.G.; Lopes, J. da C. ; Mendes, C.C.H.; Filho, A.J.M.; da Silva, C.A.M.; Miranda, V.D.S.C.; dos Santos, L.C.; Vilacoert, F.S. da S.; et al. Endothelium activation during severe yellow fever triggers an intense cytokine-mediated inflammatory response in the liver parenchyma. Pathogens 2022, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, K.R.L.J.; Tauil, P.L. Risk of re-emergence of urban yellow fever in Brazil. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude 2017, 26, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto-Lima, D.; Madec, Y.; Bersot, M.I.; Campos, S.S.; Motta, M.A.; Santos, F.B.D.; Vazeille, M.; Vasconcelos, P.F.D.C.; Lourenço-de-Oliveira, R.; Failloux, A.-B. Potential risk of re-emergence of urban transmission of yellow fever virus in Brazil facilitated by competent Aedes populations. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosser, J.I.; Nielsen-Saines, K.; Saad, E.; Fuller, T. Reemergence of yellow fever virus in southeastern Brazil, 2017–2018: What sparked the spread? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, T.; Siqueira, S.A.; Santos, R.T.; Nassar, E.S.; Coimbra, T.L.; Alves, V.A. Human fatal yellow fever: Immunohistochemical detection of viral antigens in the liver, kidney and heart. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1992, 188, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marianneau, P.; Desprès, P.; Deubel, V. Connaissances récentes sur la pathogénie de la fièvre jaune et questions pour le futur [Recent knowledge on the pathogenesis of yellow fever and questions for the future]. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 1999, 92, 432–434. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A.L.; Kang, L.I.; de Assis Barros D'Elia Zanella, L.G.F.; Silveira, C.G.T.; Ho, Y.L.; Foquet, L. ; Bial, G; McCune, B. T.; Duarte-Neto, A.N.; Thomas, A.; Raué, H.P.; Byrnes, K.; Kallas, E.G.; Slifka, M.K.; Diamond, M.S. Consumptive coagulopathy of severe yellow fever occurs independently of hepatocellular tropism and massive hepatic injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 32648–32656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J. da C. ; Falcão, L.F.M.; Martins Filho, A.J.; Carvalho, M.L.G.; Mendes, C.C.H.; Olímpio, F.A.; do Socorro Cabral Miranda, V.; Dos Santos, L.C.; Chiang, J.O.; Cruz, A.C.R.; Galúcio, V.C.A.; do Socorro da Silva Azevedo, R.; Martins, L.C.; Duarte, M.I.S.; de Sousa, J.R.; da Costa Vasconcelos, P.F.; Quaresma, J.A.S. Factors involved in the apoptotic cell death mechanism in yellow fever hepatitis. Viruses 2022, 14, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Y.P.; Falcão, L.F.M.; Smith, V.C.; de Sousa, J.R.; Pagliari, C.; Franco, E.C.S.; Cruz, A.C.R.; Chiang, J.O.; Martins, L.C.; Nunes, J.A.L.; Vilacoert, F.S.D.S.; Santos, L.C.D.; Furlaneto, M.P.; Fuzii, H.T.; Bertonsin Filho, M.V.; da Costa, L.D.; Duarte, M.I.S.; Furlaneto, I.P.; Martins Filho, A.J.; Aarão, T.L.S.; Vasconcelos, P.F.D.C.; Quaresma, J.A.S. Comparative analysis of human hepatic lesions in dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya: Revisiting histopathological changes in the light of modern knowledge of cell pathology. Pathogens 2023, 12, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, F.O.; França, A.; Lima Filho, A.C.M.; Florentino, R.M.; Santos, M.L.; Missiaggia, D.G.; Rodrigues, G.O.L.; Dias, F.F.; Souza Passos, I.B.; Teixeira, M.M.; Andrade, A.M.F.; Lima, C.X.; Vidigal, P.V.T.; Costa, V.V.; Fonseca, M.C.; Nathanson, M.H.; Leite, M.F. Molecular mechanism for protection against liver failure in human yellow fever infection. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, M.L.G.; Falcão, L.F.M.; Lopes, J.D.C.; Mendes, C.C.H.; Olímpio, F.A.; Miranda, V.D.S.C.; Santos, L.C.D.; de Moraes, D.D.P.; Bertonsin Filho, M.V.; da Costa, L.D.; da Silva Azevedo, R.D.S.; Cruz, A.C.R.; Galúcio, V.C.A.; Martins, L.C.; Duarte, M.I.S.; Martins Filho, A.J.; Sousa, J.R.; Vasconcelos, P.F.D.C.; Quaresma, J.A.S. Role of Th17 cytokines in the liver's immune response during fatal yellow fever: Triggering cell damage mechanisms. Cells 2022, 11, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaucher, D.; Therrien, R.; Kettaf, N.; Angermann, B.R.; Boucher, G.; Filali-Mouhim, A.; Moser, J.M.; Mehta, R.S.; Drake, D.R., 3rd; Castro, E.; Akondy, R.; Rinfret, A.; Yassine-Diab, B.; Said, E.A.; Chouikh, Y.; Cameron, M.J.; Clum, R.; Kelvin, D.; Somogyi, R.; Greller, L.D.; Balderas, R.S.; Wilkinson, P.; Pantaleo, G.; Tartaglia, J.; Haddad, E.K.; Sékaly, R.P. Yellow fever vaccine induces integrated multilineage and polyfunctional immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 3119–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, N.; Ivarsson, M.A.; Blom, K.; Gonzalez, V.D.; Braun, M.; Falconer, K.; Gustafsson, R.; Fogdell-Hahn, A.; Sandberg, J.K.; Michaëlsson, J. The human NK cell response to yellow fever virus 17D is primarily governed by NK cell differentiation independently of NK cell education. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 3262–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kum, D.B.; Boudewijns, R.; Ma, J.; Mishra, N.; Schols, D.; Neyts, J.; Dallmeier, K. A chimeric yellow fever–Zika virus vaccine candidate fully protects against yellow fever virus infection in mice. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E.I.; Sutterwala, F.S. Initiation and perpetuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and assembly. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 265, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; An, S.; Dong, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, M. NLRP3 inflammasome activation mediates Zika virus-associated inflammation. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 1942–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, G.; Wu, D.; Luo, Z.; Pan, P.; Tian, M.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, F.; Li, A.; Wu, K.; Liu, X.; Rao, L.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J. Zika virus infection induces host inflammatory responses by facilitating NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and interleukin-1β secretion. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, J.R.; Azevedo, R.D.S.D.S.; Martins Filho, A.J.; de Araujo, M.T.F.; Cruz, E.D.R.M.; Vasconcelos, B.C.B.; Cruz, A.C.R.; de Oliveira, C.S.; Martins, L.C.; Vasconcelos, B.H.B.; Casseb, L.M.N.; Chiang, J.O.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Vasconcelos, P.F.D.C. In situ inflammasome activation results in severe damage to the central nervous system in fatal Zika virus microcephaly cases. Cytokine 2018, 111, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.S.S.; de Sousa, J.R.; Araujo, M.T.F.; Martins Filho, A.J.; de Alcantara, B.N.; Araujo, F.M.C.; Queiroz, M.G.L.; Cruz, A.C.R.; Vasconcelos, B.H.B.; Chiang, J.O.; Martins, L.C.; Casseb, L.M.N.; da Silva, E.V.; Carvalho, V.L.; Vasconcelos, B.C.B.; Rodrigues, S.G.; Oliveira, C.S.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C. In situ immune response and mechanisms of cell damage in central nervous system of fatal cases microcephaly by Zika virus. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.S.; Sousa, J.R.; Bezerra Júnior, P.S.; Cerqueira, V.D.; Oliveira Júnior, C.A.; Rivero, G.R.C.; Castro, P.H.G.; Silva, G.A.; Muniz, J.A.P.C.; da Silva, E.V.P.; Casseb, S.M.M; Pagliari, C.; Martins, L.C.; Tesh, R.B.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C. Experimental yellow fever in squirrel monkey: Characterization of liver in situ immune response. Viruses 2023, 15, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeGottardi, Q.; Gates, T.J.; Yang, J.; James, E.A.; Malhotra, U.; Chow, I.T.; Simoni, Y.; Fehlings, M.; Newell, E.W.; DeBerg, H.A.; Kwok, W.W. Ontogeny of different subsets of yellow fever virus-specific circulatory CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells after yellow fever vaccination. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azamor, T.; da Silva, A.M.V.; Melgaço, J.G.; Dos Santos, A.P.; Xavier-Carvalho, C.; Alvarado-Arnez, L.E.; Batista-Silva, L.R.; de Souza Matos, D.C.; Bayma, C.; Missailidis, S.; Ano Bom, A.P.D.; Moraes, M.O.; da Costa Neves, P.C. Activation of an effective immune response after yellow fever vaccination is associated with the genetic background and early response of IFN-γ and CLEC5A. Viruses 2021, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovay, A.; Fuertes Marraco, S.A.; Speiser, D.E. Yellow fever virus vaccination: An emblematic model to elucidate robust human immune responses. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 2471–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, R.F.; Costa, R.S.; Silva, J.R.; Peres, R.S.; Mendonça, L.R.; Colón, D.F.; Alves-Filho, J.C.; Cunha, F.Q. IL-33 signaling is essential to attenuate viral-induced encephalitis development by downregulating iNOS expression in the central nervous system. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, J.R.; Azevedo, R.S.S.; Martins Filho, A.J.; Araujo, M.T.F.; Moutinho, E.R.C.; Baldez Vasconcelos, B.C.; Cruz, A.C.R.; Oliveira, C.S.; Martins, L.C.; Baldez Vasconcelos, B.H.; Casseb, L.M.N.; Chiang, J.O.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C. Correlation between apoptosis and in situ immune response in fatal cases of microcephaly caused by Zika virus. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 2644–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, S.; Moriyama, M.; Miyake, K.; Nakashima, H.; Tanaka, A.; Maehara, T.; Iizuka-Koga, M.; Tsuboi, H.; Hayashida, J.-N.; Ishiguro, N.; Yamauchi, M.; Sumida, T.; Nakamura, S. Interleukin-33 produced by M2 macrophages and other immune cells contributes to Th2 immune reaction of IgG4-related disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, P.Y. The multifaceted roles of autophagy in flavivirus–host interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Bowman, J.W.; Jung, J.U. Autophagy during viral infection—a double-edged sword. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gordesky-Gold, B.; Leney-Greene, M.; Weinbren, N.L.; Tudor, M.; Cherry, S. Inflammation-induced, STING-dependent autophagy restricts Zika virus infection in the Drosophila brain. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, J.E.; Wudzinska, A.; Datan, E.; Quaglino, D.; Zakeri, Z. Flavivirus NS4A-induced autophagy protects cells against death and enhances virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 22147–22159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, N.; Srivastava, S.; Gupta, S.; Menon, M.B.; Patel, A.K. Dengue virus–induced autophagy is mediated by HMGB1 and promotes viral propagation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 229, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case | Patient | Gender | Age | State | Year | IT* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 001/00 | M | 25 | Tocantins | 2000 | 8 |

| 2 | 106/00 | M | 75 | Goiás | 2000 | NR** |

| 3 | 108/00 | M | 49 | Goiás | 2000 | 7 |

| 4 | 494/00 | M | NR** | Distrito Federal | 2000 | NR** |

| 5 | 251/00 | M | 16 | Mato Grosso do Sul | 2000 | 6 |

| 6 | 252/00 | M | 49 | Goiás | 2000 | NR** |

| 7 | 253/00 | M | 23 | Goiás | 2000 | NR** |

| 8 | 255/00 | M | NR** | Goiás | 2000 | NR** |

| 9 | 291/00 | M | NR** | Goiás | 2000 | NR** |

| 10 | 158/00 | M | 33 | Goiás | 2000 | NR** |

| 11 | 063/03 | M | NR** | Minas Gerais | 2003 | NR** |

| 12 | 339/04 | M | 36 | Amazonas | 2004 | 11 |

| 13 | 019/08 | M | 64 | Goiás | 2008 | 7 |

| 14 | 273/08 | M | 57 | Goiás | 2008 | 7 |

| 15 | 068/08 | F | 65 | Goiás | 2008 | 2 |

| 16 | 095/08 | M | 42 | Goiás | 2008 | 3 |

| 17 | 143/08 | M | 37 | Distrito Federal | 2008 | NR** |

| 18 | 361/15 | F | 53 | Rio grande do Norte | 2015 | 4 |

| 19 | 062/16 | M | 35 | Goiás | 2016 | NR** |

| 20 | 346/16 | M | 15 | Goiás | 2016 | 7 |

| 21 | 369/16 | M | 27 | Goiás | 2016 | 1 |

| Markers | Reference | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS | Abcam/ab15323 | 1/200 |

| IL-1β | Abcam/ab9722 | 1/100 |

| IL-18 | Abcam/ab68435 | 1/100 |

| IL-33 | Abcam/ab118503 | 1/100 |

| BECLIN 1 | Abcam/ab210498 | 1/500 |

| RIP3 | Abcam/ab152130 | 1/50 |

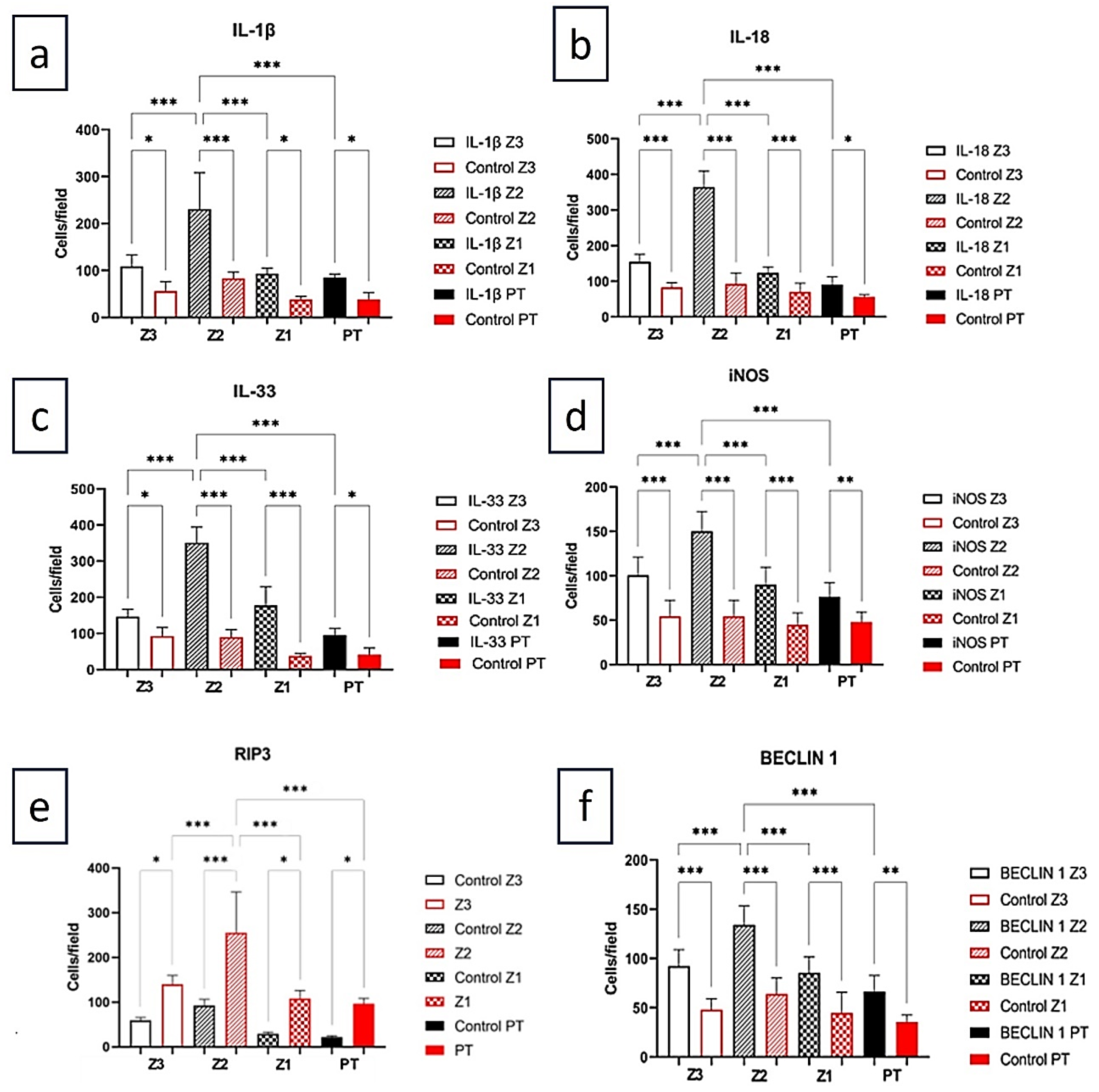

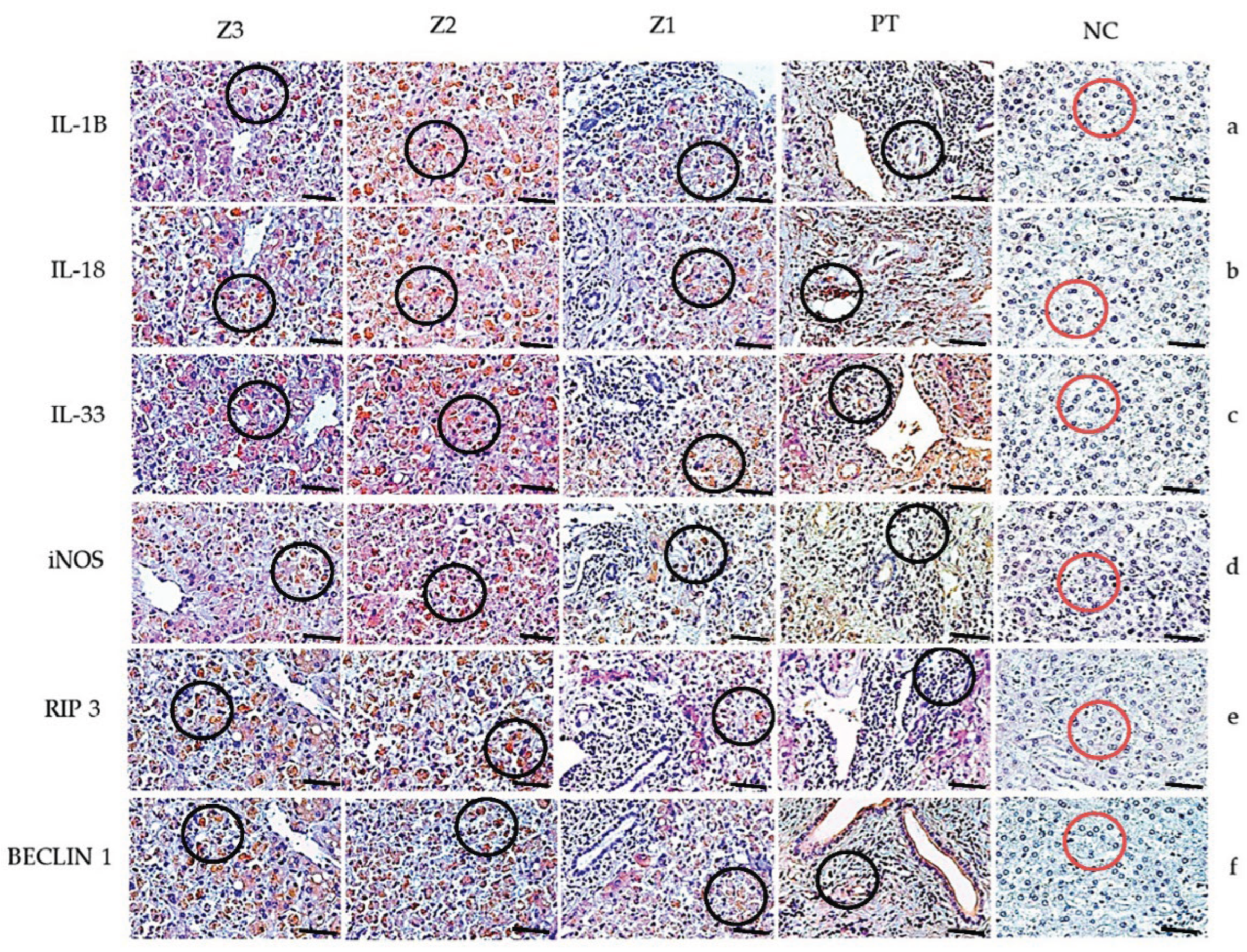

| Markers | Z3 | Z2 | Z1 | PT | ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | 109.0±24.06 | 190.5±75.03 | 86.10±16.38 | 70.10± 16.38 | <0.0001*** |

| Control | 67.20±13.39 | 83.20±13.39 | 54.40±18.24 | 48.00± 11.31 | |

| Tukey (p ≤ 0.05) | <0.0001*** | <0.0001*** | 0.0002*** | 0.0098** | |

| IL-18 | 154.7±21.06 | 365.0±44.86 | 123.4±16.89 | 90.67±21.66 | <0.0001*** |

| Control | 83.20±13.39 | 92.80±30.78 | 70.40±24.27 | 60.80±7.259 | |

| Tukey (p ≤ 0.05) | 0.0001*** | <0.0001*** | <0.0001*** | 0.0011** | |

| IL-33 | 146.3 ± 20.42 | 351.2±43.07 | 177.2±51.64 | 89.14±21.21 | <0.0001*** |

| Control | 92.80 ± 23.73 | 89.60 ± 21.47 | 37.60 ± 7.79 | 41.60 ± 18.24 | |

| Tukey (p ≤ 0.05) | 0.0011** | 0.0045** | 0.0008*** | 0.0091** | |

| iNOS | 100.6±20.33 | 150.1±22.33 | 89.90±19.90 | 76.19±15.92 | <0.0001*** |

| Control | 38.40±18.24 | 38.40±8.764 | 44.80±13.39 | 48.00±19.60 | |

| Tukey (p ≤ 0.05) | <0.0001*** | <0.0001*** | <0.0001*** | 0.0062** | |

| RIP3 | 140.20 ± 19.41 | 255.10 ± 90.92 | 108.10 ± 18.13 | 96.33 ± 12.06 |

<0.0001*** |

| Control | 59.20 ± 6.57 | 92.80 ± 13.39 | 29.40 ± 3.84 | 22.20 ± 2.68 | |

| Tukey (p ≤ 0.05) | <0.0001*** | <0.0001*** | <0.0001*** | <0.0001*** | |

| BECLIN 1 | 92.19 ± 16.71 | 134.10 ± 19.25 | 85.33 ± 16.26 | 66.29 ± 16.23 | <0.0001*** |

| Control | 48.00 ± 11.31 | 64.00 ± 16.00 | 44.80 ± 20.86 | 35.60 ± 6.98 | |

| Tukey (p ≤ 0.05) | <0.0001*** | 0.0008*** | <0.0001*** | <0.0001 |

| Pair (marker [zone] – marker [zone]) | R | p |

|---|---|---|

| RIP3 (Z1) – iNOS (PT) | 0.8402 | <0.0001 |

| RIP3 (Z2) – iNOS (PT) | -0.8333 | <0.0001 |

| RIP3 (Z2) – IL-1β (PT) | -0.8179 | <0.0001 |

| RIP3 (Z2) – iNOS (Z2) | -0.8160 | <0.0001 |

| IL-18 (Z3) – IL-33 (Z3) | 0.8044 | <0.0001 |

| iNOS (Z1) – IL-1β (PT) | 0.8011 | <0.0001 |

| IL-33 (Z2) – BECLIN-1 (Z1) | 0.7876 | <0.0001 |

| IL-33 (Z2) – BECLIN-1 (PT) | 0.7615 | 0.0002 |

| iNOS (Z2) – IL-18 (PT) | -0.7569 | <0.0001 |

| IL-18 (Z2) – BECLIN-1 (Z2) | -0.7557 | 0.0003 |

| IL-18 (Z2) – BECLIN-1 (Z1) | -0.7528 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).