1. Introduction

Yellow fever (YF) is an arboviral disease transmitted by hematophagous mosquitoes that can present a spectrum of clinical manifestations ranging from asymptomatic cases to severe forms with hemorrhage. It is a disease transmitted by mosquitoes infected with Yellow Fever Virus (YFV) belonging to the

Flavivirus genus, in Africa and is maintained in wild cycles by non-human primates (NHP) and hematophagous arthropods of the

Haemagogus and

Sabethes genera in South America. Its lethality ranges from 20% to 50% [

1].

The urban cycle encompasses

Aedes aegypti and human interactions, posing the most significant public health concern. The resurgence of this urban cycle in the Americas, coupled with vulnerable human populations, has raised alarms among public health authorities. This is primarily due to inadequate vaccination coverage in both non-endemic and endemic regions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. After the virus enters the human body through the bite of the transmitting mosquito, it quickly reaches the lymph nodes and spreads into the bloodstream. Viral replication begins in the lymph nodes. After the release of virions into the bloodstream, a period known as viremia, organs such as the liver, kidneys and spleen, for example, are also infected [

6,

7,

8].

Apoptosis and necrosis have long been considered the main processes of cell death in YF infection, but it is believed that necroptosis may play an important role in the cell death of hepatocytes [

9,

10,

11]. Necroptosis, a recently recognized type of programmed cell death, contributes to inflammation and various diseases such as cancer, stroke, and kidney disease [

12]. When triggered by various stimuli, necroptosis is initiated by the activation of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIP1). Activated RIP1 interacts with RIP3 through their RIP homotypic interaction motifs, phosphorylates RIP3, and forms an RIP1/RIP3 complex called the necrosome [

13]. Then, mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) is recruited and phosphorylated by RIP3 in the necrosome [

14]. Phosphorylated MLKL monomers aggregate to form oligomers and translocate to the plasma membrane to execute necroptosis [

14,

15].

Although multiple cell death pathways are involved in YF, including apoptosis and necrosis, the effect of necroptosis remains largely unknown [

2,

11,

16,

17,

18,

19]. In this study, our aim was to explore the activation of necroptosis in YF and identify the role of RIP1/RIP3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis in human liver tissue.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients, Samples, and Diagnosis of Yellow Fever Infection

This study used 26 human liver biopsies. Among them, 21 samples of fatal cases of YF were confirmed through positive results for the virus by reverse transcriptase reaction followed by polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and immunohistochemistry, one or both. In addition, five control samples from patients with preserved liver architecture tested negative for YF and other Flaviviruses circulating in Brazil, according to the death verification service (Renato Chaves Scientific Expertise Center) in the city of Belém in the state of Pará, Brazil. The confirmation of the diagnosis for the positive cases of YF was based on the study by Olimpio et al. [

16], including histopathological, immunohistochemical, and Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis. For histopathological diagnosis, the paraffin-embedded biopsies were cut into 5μm sections and stained with the hematoxylin-eosin method.

Table 1 shows detailed information about the patients included in this study.

2.2. Ethics Statement

Patient samples were obtained and processed as part of the response measures to the surveillance of the YFV epidemic in Brazil on an emergency basis, as defined by the Ministry of Health. This study was approved (No. 2.824.592) by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of the Evandro Instituto Chagas (IEC). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations approved by the CEP / IEC and the Brazilian Ministry of Health rules and regulations for studies with biological samples.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunostaining of the hepatic tissues with antibodies specific for MLKL (Abnova, Taiwan, TW, H00197259-M02, dilution 1:50), RIP1 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, ab72139, dilution 1:50), RIP3 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, ab152130, dilution 1:50), was performed using the streptavidin-biotin peroxidase immunohistochemical method (SABC) [

20] and adapted it according to Olímpio et al., [

16]. Briefly, tissue samples were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated in a decreasing series of ethanol (90%, 80%, and 70%). Liver sections were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 45 min to block endogenous peroxidase. Incubation in citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 20 min at 90 °C was realized to recover antigens. Non-specific proteins were blocked by incubating the sections in 10% skim milk for 30 min. Histological sections were then incubated overnight with the primary antibodies diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin (supplementary file). The slides were immersed in 1 × PBS and incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibody (LSAB; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) in an oven for 30 min at 37 °C. The slides were immersed in 1 × PBS and incubated with streptavidin peroxidase (LSAB; DakoCytomation) for 30 min at 37 °C. For visualization, specimens were treated with a chromogenic solution (0.03% diaminobenzidine and 3% hydrogen peroxide). Finally, histological sections were washed in distilled water, counterstained with Harris hematoxylin for 1 min, dehydrated in ethanol (70%, 80%, 90%), and deparaffinized in xylene.

2.4. Quantitative Analysis and Photo-Documentation

The markers used to characterize the in-situ inflammasome profile were visualised using an Axio Imager Z1 microscope (Zeiss). Immunostaining results were evaluated quantitatively by randomly selecting ten fields in the hepatic parenchyma (Z3: Pericental zone; Z2: Midzonal zone; Z1: Periportal zone; PT: Portal tract) of the fatal YF or negative control (NC) cases for viewing at high magnification. Each field was subdivided into 10 × 10 areas delimited by a 0.0625 mm2 grid.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data were stored in a Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet and analysed using GraphPadPrism 9.0. The numerical variables were expressed as the mean, median, standard deviation, and variance. One-way ANOVA, Tukey’stest, and Pearson correlation were also applied; results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

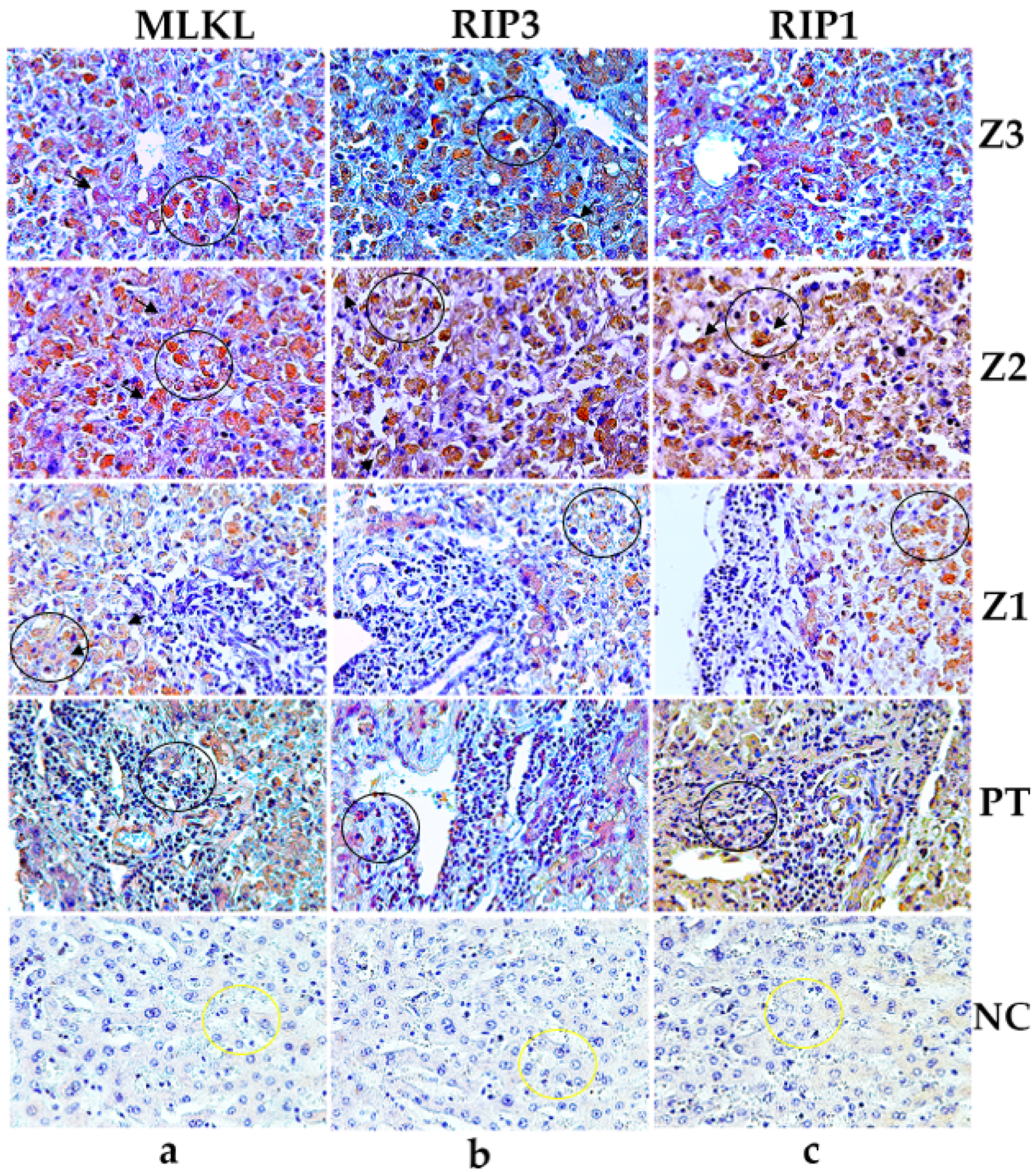

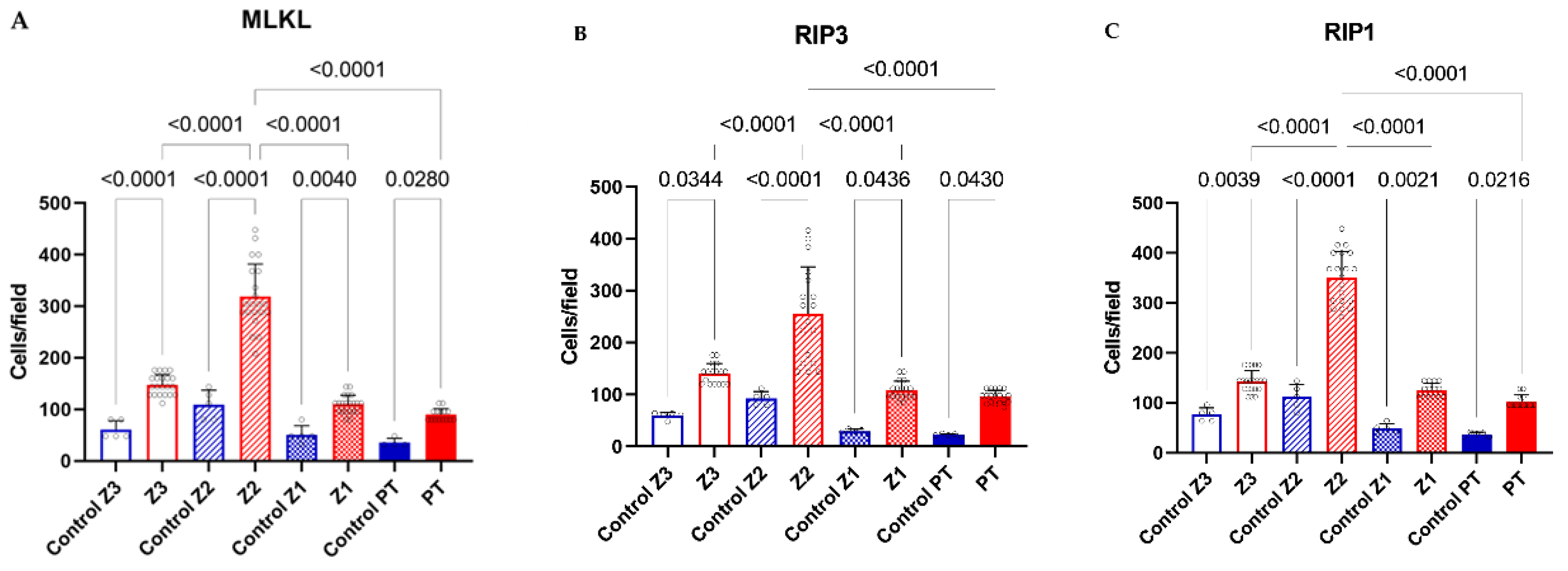

3.1. Expression of RIP1, RIP3 and MLKL in the Hepatic Parenchyma in Fatal Yellow Fever Cases

The expression level of RIP1, RIP3 and MLKL in samples from YF fatal cases showed significant differences compared to the respective controls (

Table 2) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). We found that the expressions of receptors were cleaved in response to necroptose activation and were significantly up-regulated compared to the control group. Furthermore, the YFV infection induced high levels of expressions of RIP1, RIP3 and MLKL in hepatocytes (

Table 2) (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

The current study provides crucial insights into the expression and correlation of necroptosis markers (MLKL, RIP1, and RIP3) in liver tissue from fatal Yellow Fever (YF) cases, shedding light on the underlying mechanisms of YF pathology. Immunostaining results confirmed the presence of MLKL, RIP1, and RIP3 in hepatocytes and inflammatory infiltr ates (

Table 2,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The preservation of hepatic parenchyma and minimal expression of these markers in control cases further support their specific involvement in YF pathology. The quantitative analysis revealed a significant upregulation of these markers in YF cases, particularly in the midzonal zone followed by pericental and periportal zones and inflammatory infiltrate in smaller expressions. (

Table 2,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). This spatial variation suggests the involvement of necroptosis in liver damage and hepatocyte loss as distinct roles in necroptosis induction and execution during YF infection.

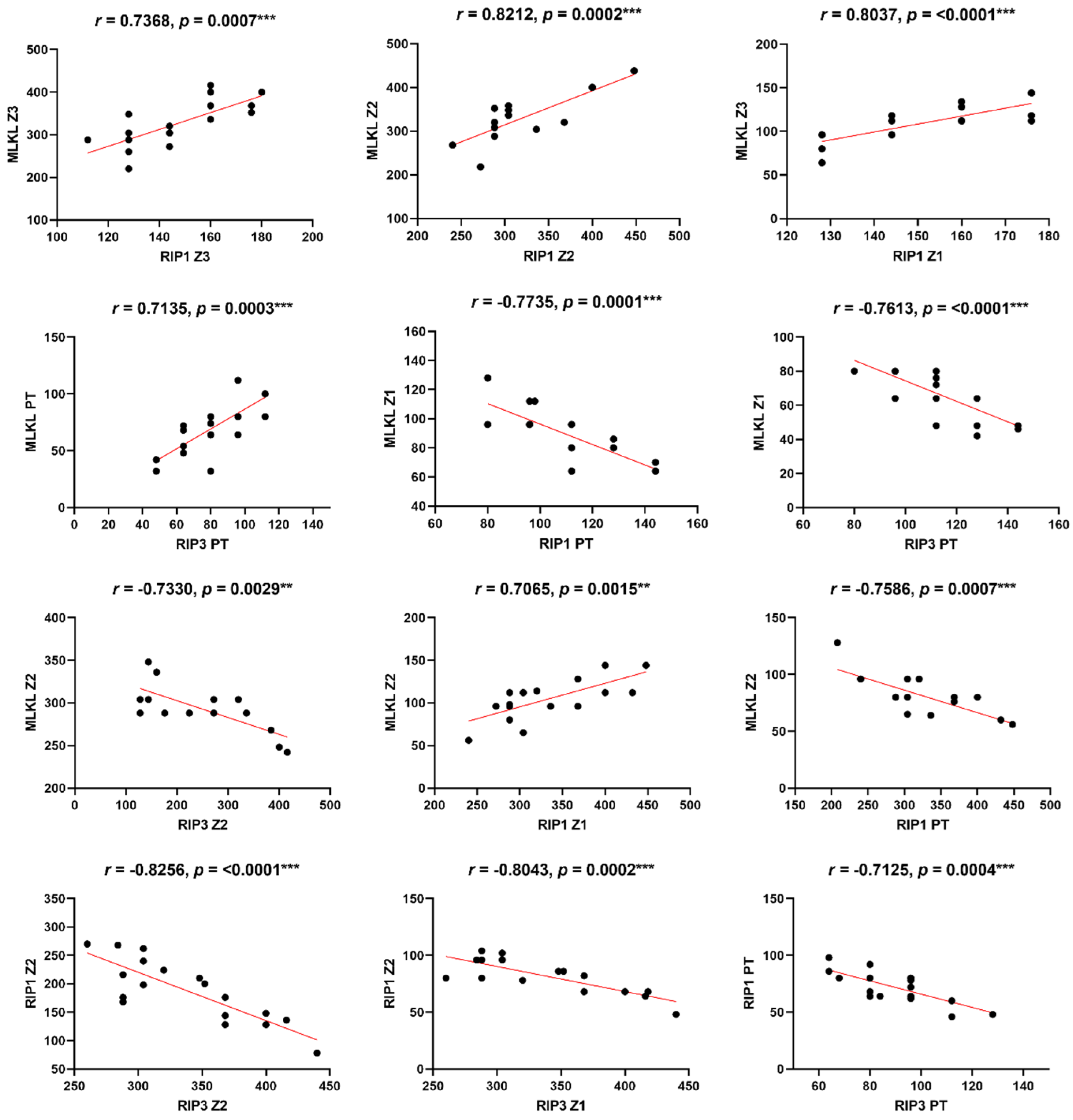

The Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant correlations between MLKL, RIP1, and RIP3 in YF cases (

Table 3,

Figure 3). The positive correlations between MLKL and RIP1, as well as MLKL and RIP3, indicate their cooperative role in necroptosis signaling. Moreover, the negative correlations observed between MLKL, RIP1, and RIP3 in certain liver zones and portal tracts imply the existence of complex regulatory mechanisms that vary across different tissue microenvironments (

Table 3,

Figure 3).

Supporting these findings, Vandenabeele et al. (21) demonstrated the crucial role of RIP1 and RIP3 in necroptosis signaling pathways. The study identified RIP1 and RIP3 as key players in the formation of the necrosome complex, which leads to the execution of necroptosis. In our study, we observed significantly higher expression levels of RIP1 and RIP3 markers in liver tissue from fatal YF cases compared to controls. This finding supports the involvement of necroptosis in YF pathogenesis, suggesting that RIP1 and RIP3 may contribute to hepatocellular necroptosis and tissue damage.

Furthermore, Wu et al. (15) highlighted the significance of MLKL in mediating necroptosis-associated inflammation. MLKL is a downstream effector molecule activated by RIP3, leading to plasma membrane disruption and release of intracellular contents, triggering inflammation. During necroptosis, the formation of RIPK1/3 heterodimers gives rise to a complex that triggers the NF-kB-mediated pro-inflammatory response, facilitating the release of cytokines/chemokines [

22,

23,

24]. Additionally, the secretion of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as ATP and HMGB1, is notably heightened during necroptosis [

25,

26]. As a consequence of these signaling cascades, distinct morphological changes from apoptosis become apparent in necroptosis, including organelle swelling and cellular lysis [

27]. As a consequence of these signaling cascades, morphological changes distinct from apoptosis become evident in necroptosis, including organelle swelling and cellular lysis. This specific morphology is discernible in

Figure 2 (black arrows), indicating the occurrence of necroptosis in severe yellow fever infection. This is further supported by elevated levels of MLKL expression in the hepatic tissue of fatal yellow fever cases (

Table 2,

Figure 1), as well as by the positive correlation between MLKL and RIP1/3 expression levels (

Table 3,

Figure 3).

Review work by Verburg et al. [

28] discussed the contribution of RIP3 and MLKL to immunopathology in viral hepatitis. The study demonstrated that the activation of RIP3 and MLKL promotes liver inflammation and tissue damage. Our results are consistent with these findings, as we observed upregulated expression levels of RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL in liver tissue from fatal YF cases. The positive correlations observed between these markers suggest their involvement in promoting hepatocellular necroptosis and inflammation in YF.

Kim et al. [

29] discussed the relationship between pyroptosis-induced necroptosis and autophagy-mediated secretion of HMGB1 in inflammatory arthritis. While our study focused on YF, this research provides insights into the crosstalk between different forms of regulated cell death. Necroptosis and pyroptosis share common signaling pathways and may contribute to tissue damage and inflammation [

30]. Although our study did not investigate pyroptosis specifically, the findings highlight the complexity of cell death mechanisms in viral infections and their potential impact on disease progression.

Overall, the literature supports our results, indicating the involvement of necroptosis and the upregulation of MLKL, RIP1, and RIP3 markers in liver tissue from fatal YF cases. The positive correlations observed between these markers further reinforce their interplay and potential contribution to hepatocellular necroptosis and tissue damage. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of necroptosis and its association with YF pathogenesis may pave the way for the development of targeted therapies to mitigate liver injury and improve patient outcomes in YF cases.

5. Conclusion

Our study provides quantitative evidence for the upregulation of necroptosis markers MLKL, RIP1, and RIP3 in human liver tissue from fatal YFV cases. The differential expression patterns of these markers in different liver zones and portal tracts suggest a spatially regulated involvement of necroptosis in the pathogenesis of yellow fever. Furthermore, the observed correlations among MLKL, RIP1, and RIP3 expression levels in YFV cases support their cooperative role in necroptosis induction during YFV infection. Further research is needed to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms and the potential therapeutic implications of targeting necroptosis in yellow fever.

Author Contributions

V.d.S.C.M., J.R.d.S, J.A.S.Q., and P.F.d.C.V. designed the study; M.L.G.C., J.R.d.S., J.d.C.L., C.C.H.M., F.A.O., C.A.M.d.S., L.C.d.S., F.S.d.S.V., R.d.S.d.S.A., A.C.R.C., V.C.A.G., M.I.S.D., and L.C.M. performed lab tests; M.I.S.D., J.A.S.Q., and P.F.C.V. furnished reagents; L.F.M.F., J.R.d.S., M.I.S.D., J.A.S.Q., and P.F.d.C.V. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final draft and agree to submit.

Funding

This study was supported by the Brazilian Council for the Scientific and Technologic Development Agency (CNPq) for financial support to PFCV (grants 457664/2013-4 and 303999/2016-0).

References

- Gardner, C.L.; Ryman, K.D. Yellow Fever: A Reemerging Threat. Clin. Lab. Med. 2010, 30, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, P.F.; Bryant, J.E.; da Rosa, A.P.T.; Tesh, R.B.; Rodrigues, S.G.; Barrett, A.D. Genetic Divergence and Dispersal of Yellow Fever Virus, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, W.; Carroll, J. Yellow Fever : 100 Years of Discovery The Etiology of Yellow Fever : An Additional Note. JAMA Class. 2008, 36, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Mutebi, J.-P.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Bryant, J.E.; Barrett, A.D.T. Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Relationships among Yellow Fever Virus Isolates in Africa. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 6999–7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto-Lima, D.; Madec, Y.; Bersot, M.I.; Campos, S.S.; Motta, M.d.A.; dos Santos, F.B.; Vazeille, M.; Vasconcelos, P.F.d.C.; Lourenço-De-Oliveira, R.; Failloux, A.-B. Potential risk of re-emergence of urban transmission of Yellow Fever virus in Brazil facilitated by competent Aedes populations. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VASCONCELOS, P. F. C. (2003) ‘Febre amarela: a doença e a vacina, uma história inacabada; Yellow fever: the disease and the vaccine, an unfinished history’, Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 36(2), pp. 275–293.

- Lopes, R.L.; Pinto, J.R.; Junior, G.B.d.S.; Santos, A.K.T.; Souza, M.T.O.; Daher, E.D.F. Kidney involvement in yellow fever: a review. Rev. do Inst. de Med. Trop. de Sao Paulo 2019, 61, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, G.M.M.; Ferreira, R.M. Yellow Fever and Cardiovascular Disease: An Intersection of Epidemics. Arq. Bras. de Cardiol. 2018, 110, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhong, C.-Q.; Zhang, D.-W. Programmed necrosis: backup to and competitor with apoptosis in the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kusakabe, S.; Tokunaga, M.; Hirano, J.; Miyata, Y.; Matsuura, Y. Regulation of Apoptosis during Flavivirus Infection. Viruses 2017, 9, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.; Barros, V.L.; Pagliari, C.; Fernandes, E.R.; Guedes, F.; Takakura, C.F.; Andrade, H.F., Jr.; Vasconcelos, P.F.; Duarte, M.I. Revisiting the liver in human yellow fever: Virus-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes associated with TGF-β, TNF-α and NK cells activity. Virology 2006, 345, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallach, D.; Kang, T.-B.; Dillon, C.P.; Green, D.R. Programmed necrosis in inflammation: Toward identification of the effector molecules. Science 2016, 352, aaf2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.-N.; Yang, Z.-H.; Wang, X.-K.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, X.; Shao, J.; Han, J. Distinct roles of RIP1–RIP3 hetero- and RIP3–RIP3 homo-interaction in mediating necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, K.; Roelandt, R.; Bruggeman, I.; Estornes, Y.; Vandenabeele, P. Nuclear RIPK3 and MLKL contribute to cytosolic necrosome formation and necroptosis. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Cao, X.; Yang, Q.; Norton, V.; Adini, A.; Maiti, A.K.; Adini, I.; Wu, H. RIP1/RIP3/MLKL Mediates Myocardial Function Through Necroptosis in Experimental Autoimmune Myocarditis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olímpio, F.A.; Falcão, L.F.M.; Carvalho, M.L.G.; Lopes, J.d.C.; Mendes, C.C.H.; Filho, A.J.M.; da Silva, C.A.M.; Miranda, V.D.S.C.; dos Santos, L.C.; Vilacoert, F.S.d.S.; et al. Endothelium Activation during Severe Yellow Fever Triggers an Intense Cytokine-Mediated Inflammatory Response in the Liver Parenchyma. Pathogens 2022, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.S.; Barros, V.L.R.S.; Fernandes, E.R.; Pagliari, C.; Takakura, C.; Vasconcelos, P.F.d.C.; de Andrade, H.F.; Duarte, M.I.S. Reconsideration of histopathology and ultrastructural aspects of the human liver in yellow fever. Acta Trop. 2005, 94, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.; Barros, V.L.; Pagliari, C.; Fernandes, E.R.; Andrade, H.F.; Vasconcelos, P.F.; Duarte, M.I. Hepatocyte lesions and cellular immune response in yellow fever infection. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 101, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, J.A.; Duarte, M.I.; Vasconcelos, P.F. Midzonal lesions in yellow fever: A specific pattern of liver injury caused by direct virus action and in situ inflammatory response. Med Hypotheses 2006, 67, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.M.; Raine, L.; Fanger, H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1981, 29, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, K. Architectural cohesin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 607–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conos, S.A.; Chen, K.W.; De Nardo, D.; Hara, H.; Whitehead, L.; Nunez, G.; Masters, S.L.; Murphy, J.M.; Schroder, K.; Vaux, D.L.; et al. Active MLKL triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome in a cell-intrinsic manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E961–E969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhuriya, Y.K.; Sharma, D. Necroptosis: a regulated inflammatory mode of cell death. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, P.; Florez, M.; Najafov, A.; Pan, H.; Geng, J.; Ofengeim, D.; Dziedzic, S.A.; Wang, H.; Barrett, V.J.; Ito, Y.; et al. Regulation of a distinct activated RIPK1 intermediate bridging complex I and complex II in TNFα-mediated apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5944–E5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaffidi, P.; Misteli, T.; Bianchi, M.E. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 2010, 418, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.S.; Pulskens, W.P.; Sadler, J.J.; Butter, L.M.; Teske, G.J.; Ulland, T.K.; Eisenbarth, S.C.; Florquin, S.; Flavell, R.A.; Leemans, J.C.; et al. Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 20388–20393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rello, S.; Stockert, J.C.; Moreno, V.; Pacheco, M.; Juarranz, A.; Villanueva, A.; Gámez, A.; Cañete, M. Morphological criteria to distinguish cell death induced by apoptotic and necrotic treatments. Apoptosis 2005, 10, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, S.G.; Lelievre, R.M.; Westerveld, M.J.; Inkol, J.M.; Sun, Y.L.; Workenhe, S.T. Viral-mediated activation and inhibition of programmed cell death. PLOS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Hong J, Jeon YM, et al. Pyroptosis-induced necroptosis is driven by autophagy-mediated secretion of HMGB1 in inflammatory arthritis. Cells. 2021 Jun 4;10(6):1204. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Chan, F.K.-M.; Kroemer, G. Necroptosis: Mechanisms and Relevance to Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2017, 12, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).