Introduction

Wounds of the distal limb present a clinical challenge in horses, as they heal slowly and sometimes incompletely, leading to persistent lameness, limb swelling, extensive scars, and subsequent loss of use or euthanasia of the horse. Amnion-derived materials have been studied in the horse, man and other species, and have shown promise in acceleration of wound healing with good cosmetic outcomes.[1−4] A processed, human-derived amnion material that may become commercially available could make amnion more widely available for use by practitioners and medical providers without the inconveniences of harvesting, processing and storing equine amnion. Previous research on this material in a porcine model showed accelerated healing times with no adverse effects.[

5]

The proposed effects of amnion as a wound dressing include acting as a scaffold and providing growth factors to accelerate healing. In the presence of amnion

in vitro, both fibroblasts and keratinocytes have improved cellular proliferation and migration.[

6] Amnion contains growth factors and cytokines essential for healing such as hepatocyte growth factor, keratinocyte growth factor, transforming growth factor β1, and others. Further processing of amnion membranes into a powdered form increased the availability of these growth factors.[

7,

8] Amnion membranes also have favorable antimicrobial effects, inhibiting the growth of some microorganisms in vitro including

Pseudomonas spp. [

9] Previous equine studies comparing amnion treated wounds to control have shown variable results. One study found that liquified amnion injection did not improve healing compared with control [

10]. While another study showed that amnion together with pinch grafting improved healing time compared with pinch graft alone [

2]. A third study showed that equine amnion membrane treatment of wounds accelerated granulation tissue formation [

11].

The primary purpose of this pilot study was to assess the safety of a processed human amnion material for distal limb wound healing in the horse. Secondary objectives for the study were to assess the impact of the human amnion material on rate of wound healing, contraction and epithelialization, the quality of healed skin and the cosmetic appearance of wounds treated with the amnion material. We hypothesized that the lyophilized human amnion would be safe for use on wounds of the distal limb in the horse. We also hypothesized that the amnion would accelerate contraction and epithelialization of experimentally created distal limb wounds.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design: A randomized, blinded, controlled research study was designed using an equine model of distal wound healing. Bilateral forelimbs of 4 healthy horses were used, with one limb randomly assigned as treatment, and the contralateral limb assigned as control. Limbs were assigned to the treatment or control group randomly via random number generator, with odd numbers receiving the treatment on the left forelimb and even numbers receiving the treatment on the right forelimb. All wounds on the treatment limb received the amnion-material treatment protocol and all wounds on the control limb received the control protocol. All assessments and data were blinded for analysis including photographs of wounds.

Animals: Four clinically healthy adult horses (3 Thoroughbred and 1 Paint Cross) with a median age of 11 years (ages 6, 10, 12 and 19 years) were obtained via donation. Inclusion criteria were distal forelimbs free from wounds or scars and horses with no known systemic or metabolic disease. Horses were evaluated for lameness evident at the walk and received physical examinations consisting of temperature, pulse rate, respiratory rate, as well as visual inspection and manual palpation of the limbs. All animal involvement was performed under the regulation and approval of the institution’s animal care and use committee (protocol 16-168).

Tested Material: A human-derived amnion material was used for amnion-treated wounds.5 Briefly, the amnion was washed with sterile saline, frozen, lyophilized, milled, gamma irradiated at 1 megarad and stored at -80°C. The material was prepared at Wake Forest Institute of Regenerative Medicine, frozen, and shipped in 70 mg doses to the testing center.

Wounding and Treatment Application: Wounds were created on Day 0. Each horse was administered 1g phenylbutazone per os pre-operatively, then once daily for 5 days post-operatively. The horses were sedated with detomidine (0.01mg/kg IV) and butorphanol (0.01mg/kg IV) and the distal forelimbs were clipped and aseptically prepared. Mepivacaine hydrochloride 2% (30mL/horse) was infiltrated subcutaneously as a circumferential ring block at the level of the proximal metacarpus. Additional local anesthetic was provided as a high palmar nerve block [

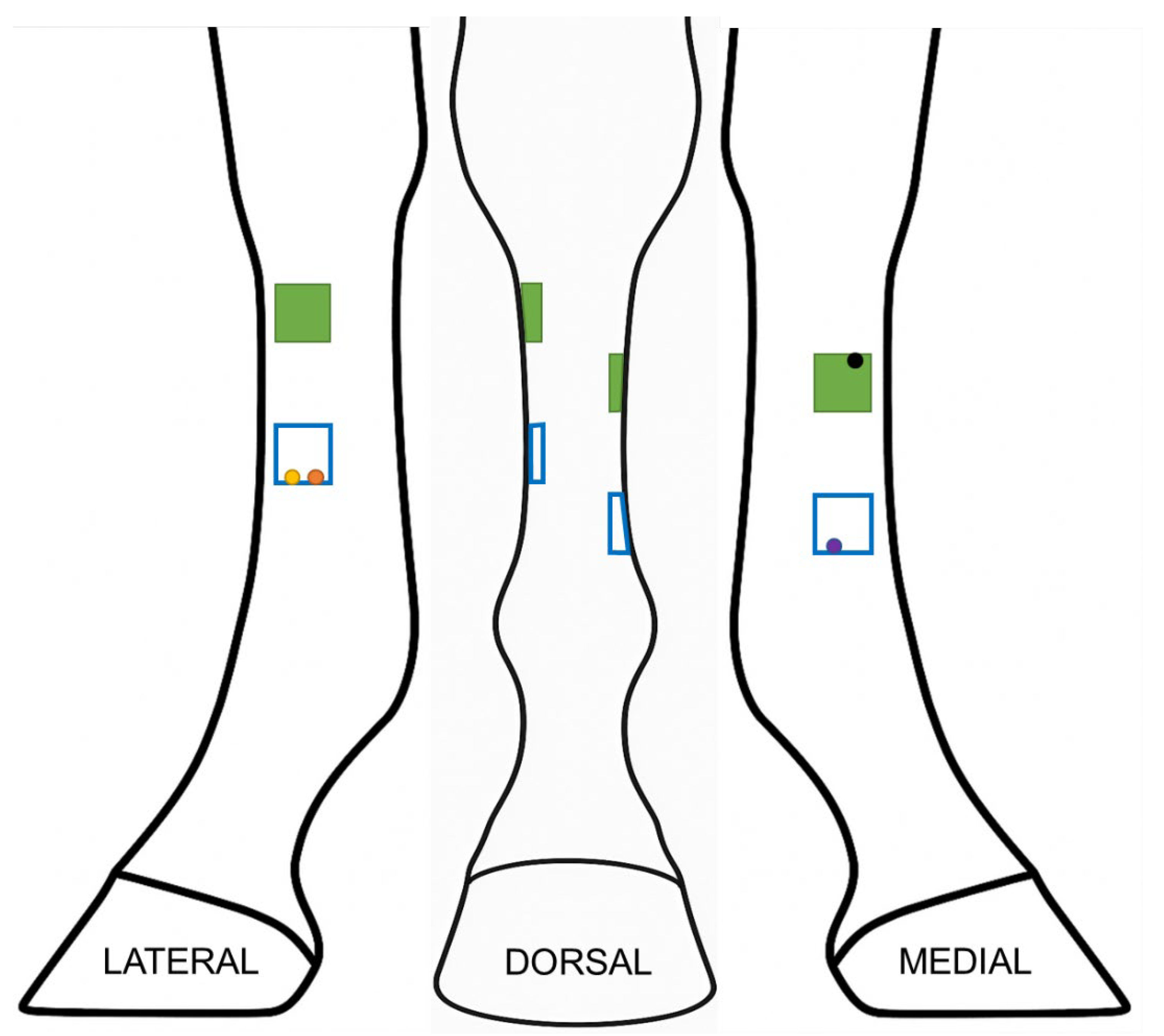

12] bilaterally in one horse that retained cutaneous sensation after the ring blocks. A sterile plastic template was used to create four evenly spaced, 2.5 cm x 2.5 cm, full-thickness skin wounds with a scalpel blade on each forelimb (

Figure 1). Each wound was a minimum of 3cm in any direction from the adjacent wounds. The excised skin was placed in 10% buffered formalin and retained as a normal control on histopathology.

Either 70 mg of amnion material spread on 1mL of triple antibiotic ointment (treatment limb), or 1mL of triple antibiotic ointment alone (control limb) was applied to a non-adherent dressing on Day 0 using the sterile plastic template to ensure complete delivery of the treatment or control material to each wound. Investigators conducting assessments were not aware of which limb was treatment or control. The non-adherent dressing was secured to the limb over each wound using conforming gauze immediately after skin excision. The gauze was held in place with elastic adhesive tape (Elastikon) and a standard distal limb bandage applied using cotton combine bandages secured with elastic compression wraps. The top and bottom of each bandage was sealed with elastic adhesive tape to prevent entry of dirt or debris. The treatment material was applied only on Day 0.

Figure 1.

Schematic of distribution of wounds on the distal limb. Four 2.5 by 2.5 cm wounds (represented by squares) were created at the proximomedial, proximolateral, distomedial and distolateral aspect of the metacarpus. Each wound was at least 3 cm from the other wounds. Green squares indicate the wounds (proximolateral and proximomedial) that were used for wound measurements. Circles represent location of 6mm biopsy punches at each time point: yellow on day 7, orange on day 21, purple on day 35, and black on day 84.

Figure 1.

Schematic of distribution of wounds on the distal limb. Four 2.5 by 2.5 cm wounds (represented by squares) were created at the proximomedial, proximolateral, distomedial and distolateral aspect of the metacarpus. Each wound was at least 3 cm from the other wounds. Green squares indicate the wounds (proximolateral and proximomedial) that were used for wound measurements. Circles represent location of 6mm biopsy punches at each time point: yellow on day 7, orange on day 21, purple on day 35, and black on day 84.

Monitoring: Horses were stall rested for 7 days prior to allowing confinement in a small paddock for the remainder of the study. Horses were examined daily for temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, presence of swelling in the forelimbs and lameness at the walk for the first 7 days. Bandages were changed on all horses every 2-4 days throughout a 99-day study period. Triple antibiotic ointment was re-applied to all treatment and control wounds at each bandage change until day 9, then the wounds were bandaged without topical medication. The inner layer of the bandage was discontinued when the wounds were grossly epithelialized, and standing wraps were used for the remainder of the study period to protect the newly formed epithelium. The wounds were photographed and inspected for discharge, exuberant granulation tissue, edema and progression of healing (contraction and epithelialization).

Digital photographs (using Nikon Coolpix L340 20MP digital camera) were taken of each wound at each bandage change. A 5mm grid ruler was labeled with patient information, date and limb identifier but blinded to treatment group, then placed immediately adjacent to each wound for photographic documentation and future blinded measurement from stored images. Three photographs were taken of each wound, centered and perpendicular to the wound, at a standardized distance of 20cm from the limb using the flash setting.

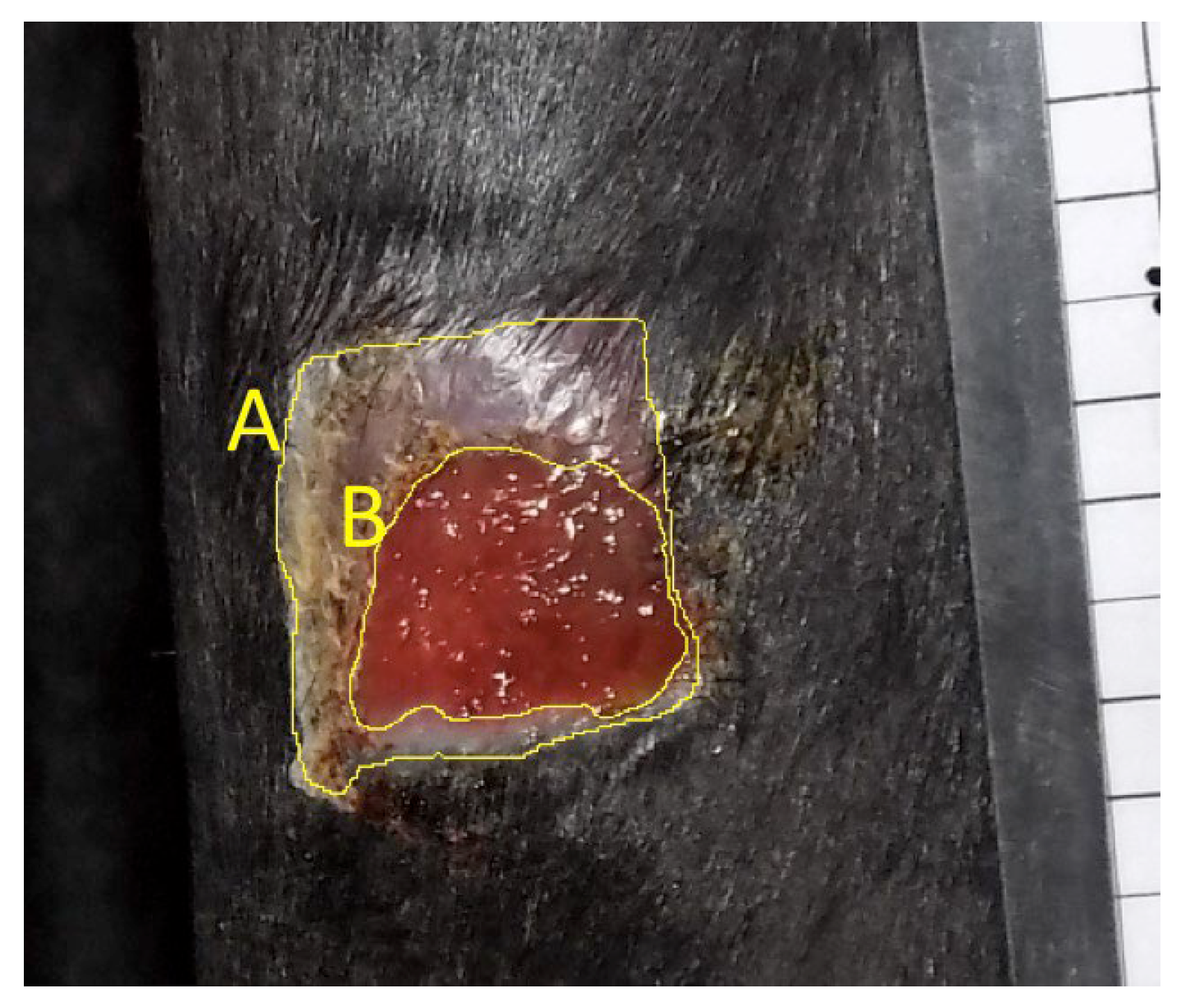

Wound Measurements: Two-dimensional digital planimetry was performed to calculate wound area and epithelialized area from the digital images using ImageJ software. The highest-quality photograph from each wound on each day was selected for measurement. The digital photograph was imported to ImageJ and magnified to 50%. A 20mm bar was measured on the photographed ruler and “set scale” software function used to standardize subsequent measurements for each photograph. The freehand selection tool was then used to measure the interface of normal skin with neoepidermis (“Outer - epidermal margin,” line A,

Figure 2) as well as the junction of neoepidermis with non-epithelialized tissue (“Inner - wound margin,” line B,

Figure 2). Each measurement was repeated in triplicate and the mean used for subsequent analysis. A single, blinded observer performed all measurements. Only measurements of proximal wounds were retained for statistical analysis to avoid confounding impact of biopsy procedures, which were performed on the distal wounds (

Figure 1).

Histopathology: Pre-selected wounds were biopsied on days 7, 21, 35 and 84 (

Figure 1). The distolateral wounds were sampled on day 7 (distal abaxial margin) and 21 (distal axial margin), distomedial wounds on day 35 (distal axial margin), and proximolateral wounds on day 84 (proximal margin). The proximal wounds were left undisturbed until the final time point at day 84, so that influence of biopsy site did not confound wound measurements. To perform the biopsy, the adjacent skin was aseptically prepared with chlorhexidine and rinsed with sterile saline. Horses were administered 1g phenylbutazone per os and sedated with xylazine (0.3-0.4mg/kg IV) and detomidine (0.006-0.01 mg/kg IV) with or without butorphanol (0.01mg/kg IV) depending on temperament. For biopsy, local anesthesia was provided for each wound with subcutaneous infiltration of mepivacaine (5mL/wound) as an inverted “L” block adjacent to the wound to be sampled. A 6mm biopsy punch was used to obtain a sample of the wound margin, including ~2mm of adjacent skin. The samples were immediately placed in 10% buffered formalin for histopathology. The tissue samples were shipped to a secondary institution (WFIRM) and paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained. Staining was performed with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome. All prepared slides were evaluated and scored by a board-certified pathologist.

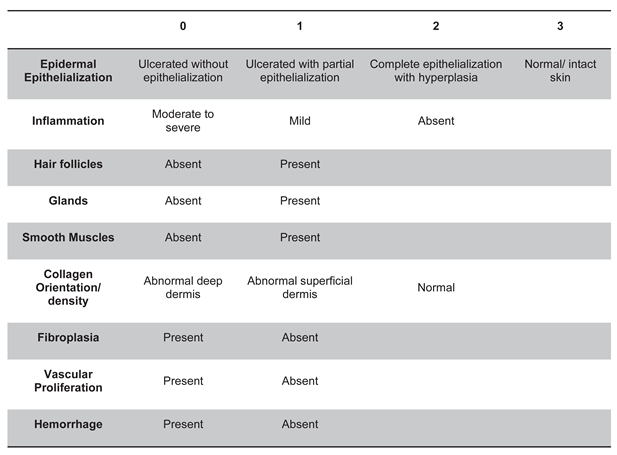

All biopsied wounds and day 0 controls were scored according to a pre-determined scale for presence or degree of epidermal epithelialization (0-3), inflammatory cellular infiltrate (0-2), hair follicles (0-1), glands (0-1), smooth muscle (0-1), collagen orientation/density (0-2), fibroplasia (0-1), vascular proliferation (0-1), and hemorrhage (0-1), resulting in a maximum score of 13 representing normal skin (

Table 1). Only the wounded tissue in the biopsy sample was evaluated for scoring. Glands refer to the

presence of either apocrine or sebaceous glands. Hemorrhage was defined as any evidence of chronic hemorrhage associated with the original wound or healing process including evidence of erythrophagocytosis, hemosiderosis, perivascular hemorrhage, or significantly more hemorrhage than in the day 0 control samples. Extravasated red blood cells without these changes were interpreted as acute hemorrhage associated with the biopsy procedure and were not counted in the scoring rubric.

Follow-up: Since this was a non-terminal study of research horses retained at the center, after the conclusion of the study on day 84, limbs were photographed and/or biopsied if horses remained available. Assessments remained blinded.

Statistical Analysis: Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 18 and R (v4.3.0). Because each horse contributed both a treatment and contralateral control wound, analyses were blocked for Horse to account for pairing and repeated measures. Mixed-effects models were specified with fixed effects for treatment (Control vs. Treatment), day, and their interaction, with Horse included as a random intercept. Time to complete healing, contraction, and epithelialization were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models (REML estimation). The overall model tested for treatment, day, and interaction effects, and planned within-day contrasts compared Treatment vs. Control at each time point.

Total histopathology scores (0–13) were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model with a negative binomial distribution and log link to accommodate the skewed, count-like data. Ordinal histology categories (epithelialization, inflammation, collagen orientation) were analyzed using cumulative link mixed models with a logit link. Binary categories (hair follicles, glands, smooth muscle, fibroplasia, vascular proliferation, hemorrhage) were analyzed with binomial mixed models; when sparse data precluded model fitting, McNemar’s exact test was applied. All tests were two-sided with significance defined as p < 0.05; values of 0.05–0.10 were considered trends.

3. Results

Safety and Complications: No horses had serious adverse reactions to the wound model, nor to the treatment. One horse had a complication – cellulitis in one limb - develop on day 2 of the study. It was determined after unblinding at the conclusion of this cohort of horses that the cellulitis occurred in the treatment limb, and the control limb had no cellulitis. During creation of the first wound on day 0, this horse retained sensation and underwent repeated injection of local anesthesia in both forelimbs followed by bilateral high palmar nerve blocks until desensitization was achieved. On day 2, the horse was reluctant to bend one forelimb and had hot, painful edema from the carpus distal. He was sound at the walk. The horse was treated systemically with trimethoprim sulfa (22mg/kg per os q12h) for 10 days and phenylbutazone (1g per os q12h) for 10 days. The heat and edema resolved by day 7 of the study and this horse had no further adverse events.

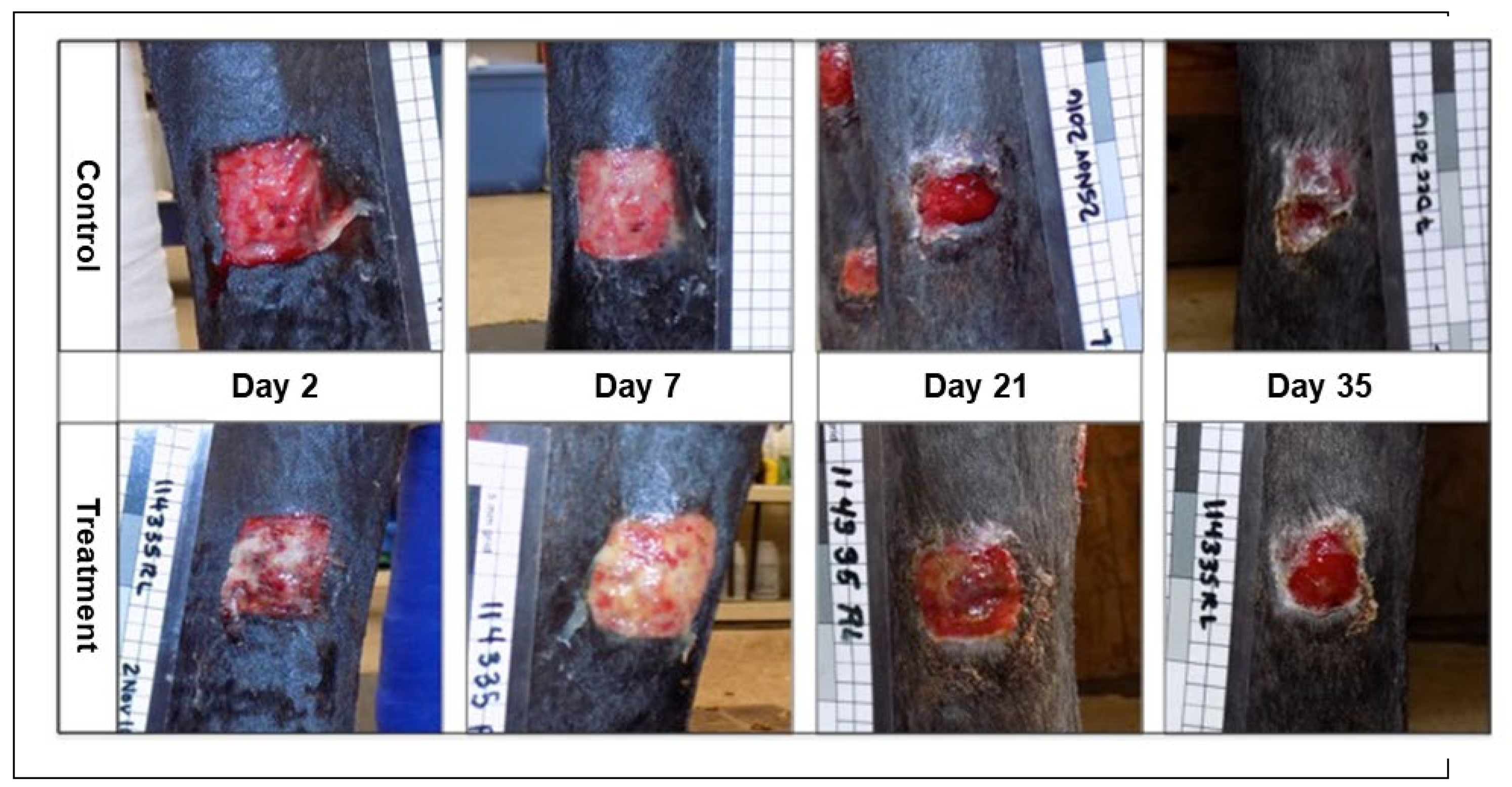

Gross Appearance of Wounds: Subjectively, the wounds on the treatment limbs had a visible difference in gross appearance throughout the study period which was assessed blinded to treatment. This effect was most marked in the early stages of wound healing (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). In general, the wounds on the control limbs were flat, red in color, with minimal serous discharge. In contrast, wounds on the treatment limbs had mild to severe local edema with a roughened or irregular, cobblestone surface, were tan in color, with varying degrees of increased serous or fibrinous exudate.

Time to Epithelialization: Amnion-treated wounds took significantly longer to heal compared with contralateral control wounds; treatment delayed healing by an average of 5.0 days (95% CI: 1.1–8.9 days, p = 0.011).

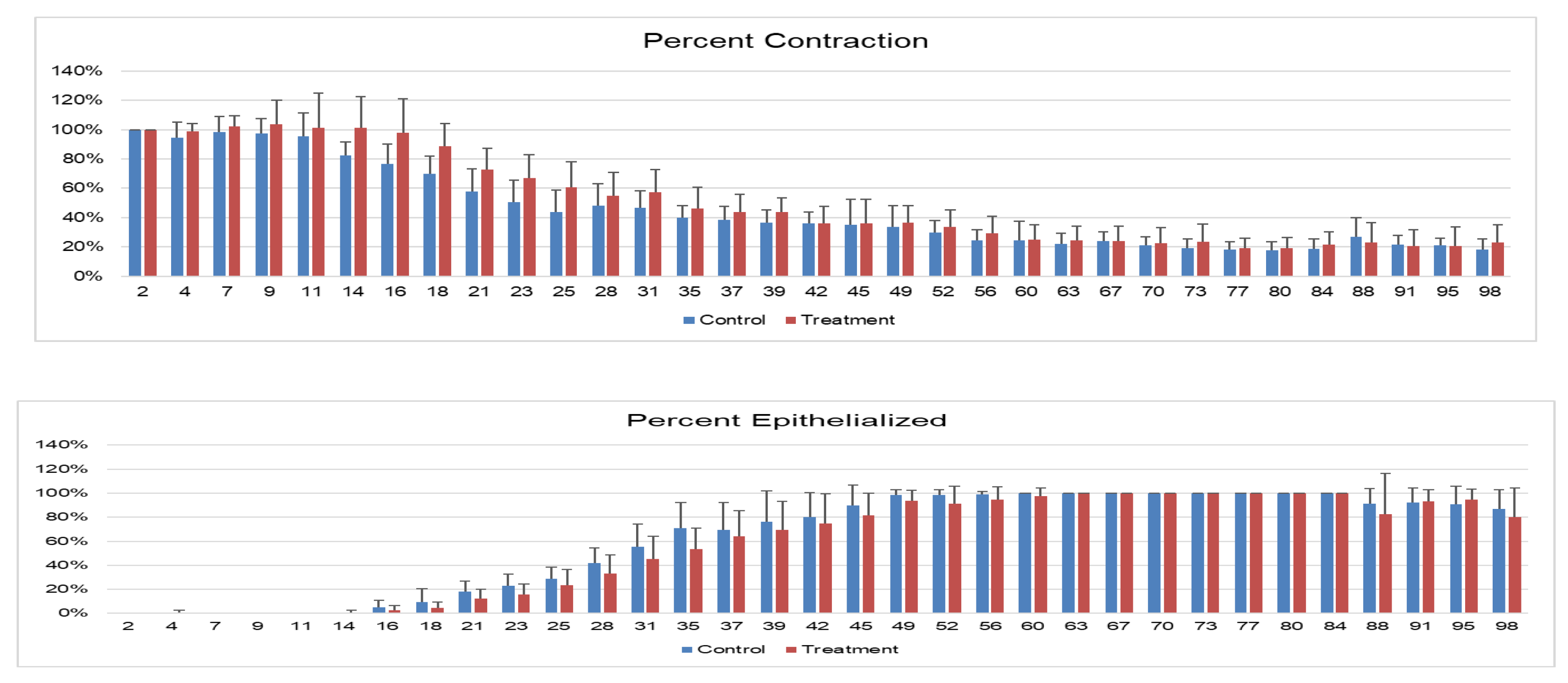

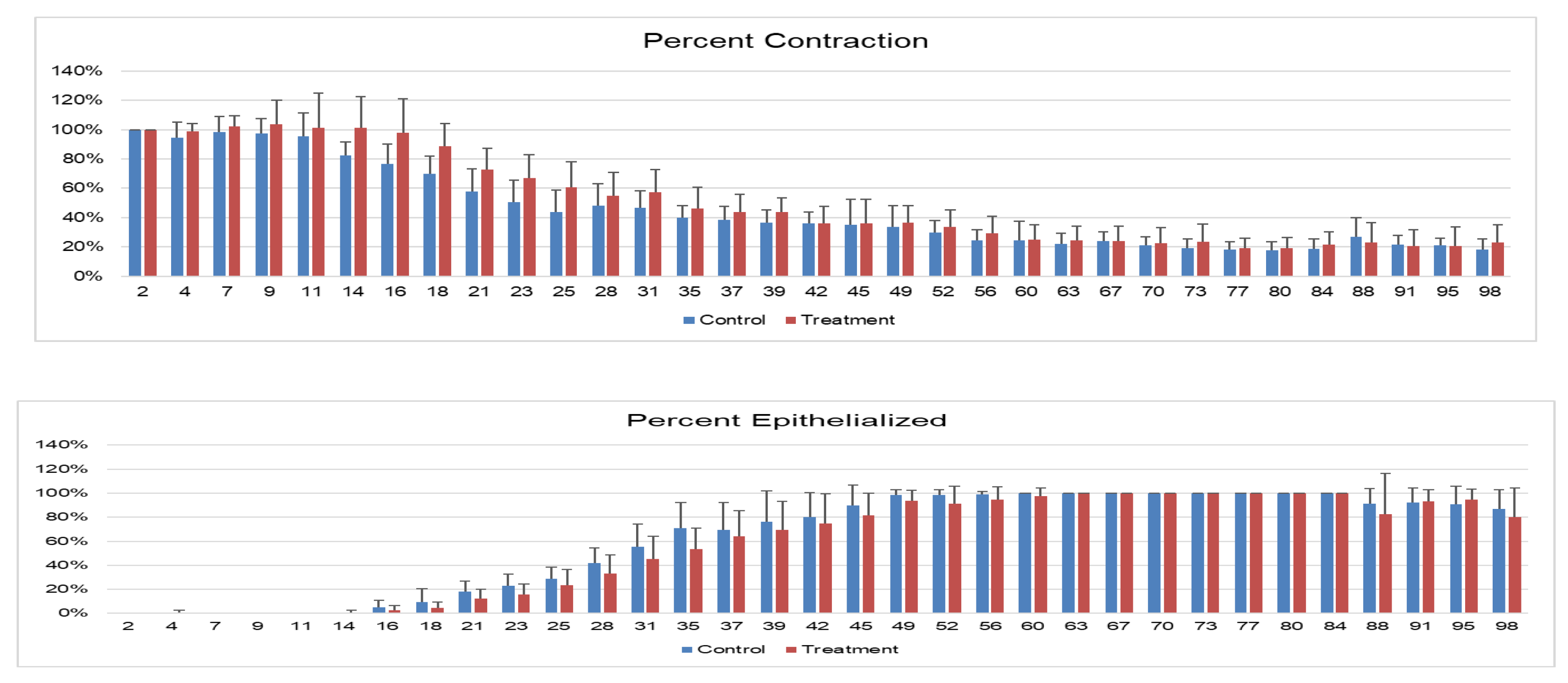

Wound Contraction and Epithelialization: Wound contraction, as measured by the area included in the outline of the outer limits of each wound, was significantly lower in treated versus control wounds at all time points, with a significant difference on days 23 and 39, with trends toward significance on days 18 and 35 (

Figure 5A). Wounds on the treated limbs had significantly lower epithelialization (

p=0.0106), and post hoc Tukey’s tests demonstrated significant differences on days 21, 31, 35, and 45, with statistical trends on days 28,42 and 49 (

Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Wound healing over time. A. Contraction of wounds – the percentage size of exterior measurement of wound compared with baseline size at wound creation (%). B. Percentage of wound with new epithelialization over time. An * denotes a significant difference (p < 0.05) between treatment and control wounds, † denotes a statistical trend with p values: 0.1 > p > 0.05 between treatment and control wounds.Histopathology: Two samples (one treatment and one control on day 21) were excluded from analysis due to sectioning error. All other wounds were evaluated using H&E at all time points (

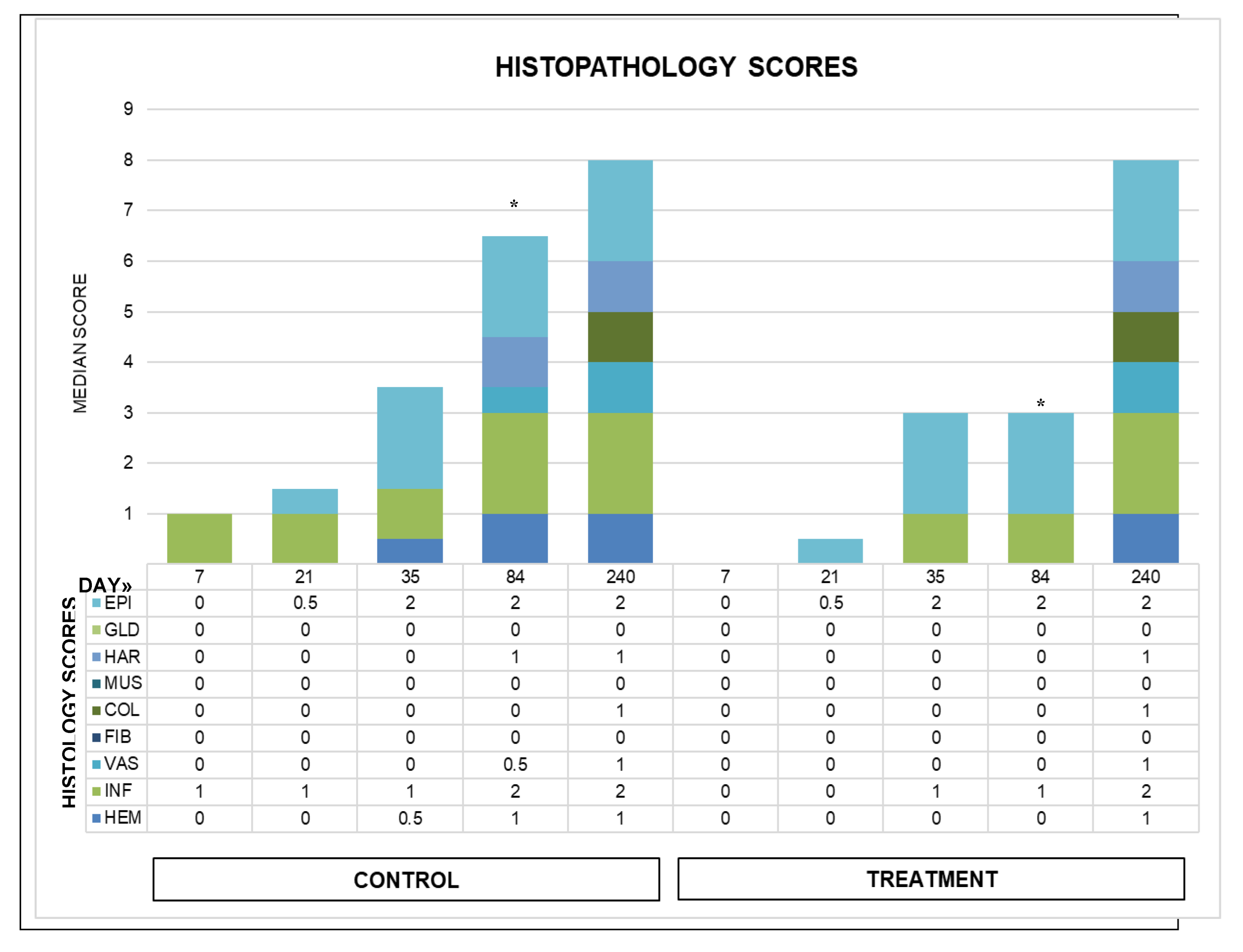

Figure 6) and Masson’s Trichrome on days 0-35. Masson’s Trichrome was not available for day 84 samples due to poor staining. Overall treatment effects were significantly different for total histology scores at day 84 (

p = 0.039), with a trend for day 21 (

p = 0.083) (

Figure 7). Overall treatment effects of individual categories were only significant for inflammation (

p = 0.0077); however, post hoc tests resulted in

p = 0.125 for day 7, 21 and 84 and

p = 0.32 for day 35. Epithelialization, collagen, vascularization, hemorrhage, and other categories improved over time without significant group differences.

Figure 5.

Wound healing over time. A. Contraction of wounds – the percentage size of exterior measurement of wound compared with baseline size at wound creation (%). B. Percentage of wound with new epithelialization over time. An * denotes a significant difference (p < 0.05) between treatment and control wounds, † denotes a statistical trend with p values: 0.1 > p > 0.05 between treatment and control wounds.Histopathology: Two samples (one treatment and one control on day 21) were excluded from analysis due to sectioning error. All other wounds were evaluated using H&E at all time points (

Figure 6) and Masson’s Trichrome on days 0-35. Masson’s Trichrome was not available for day 84 samples due to poor staining. Overall treatment effects were significantly different for total histology scores at day 84 (

p = 0.039), with a trend for day 21 (

p = 0.083) (

Figure 7). Overall treatment effects of individual categories were only significant for inflammation (

p = 0.0077); however, post hoc tests resulted in

p = 0.125 for day 7, 21 and 84 and

p = 0.32 for day 35. Epithelialization, collagen, vascularization, hemorrhage, and other categories improved over time without significant group differences.

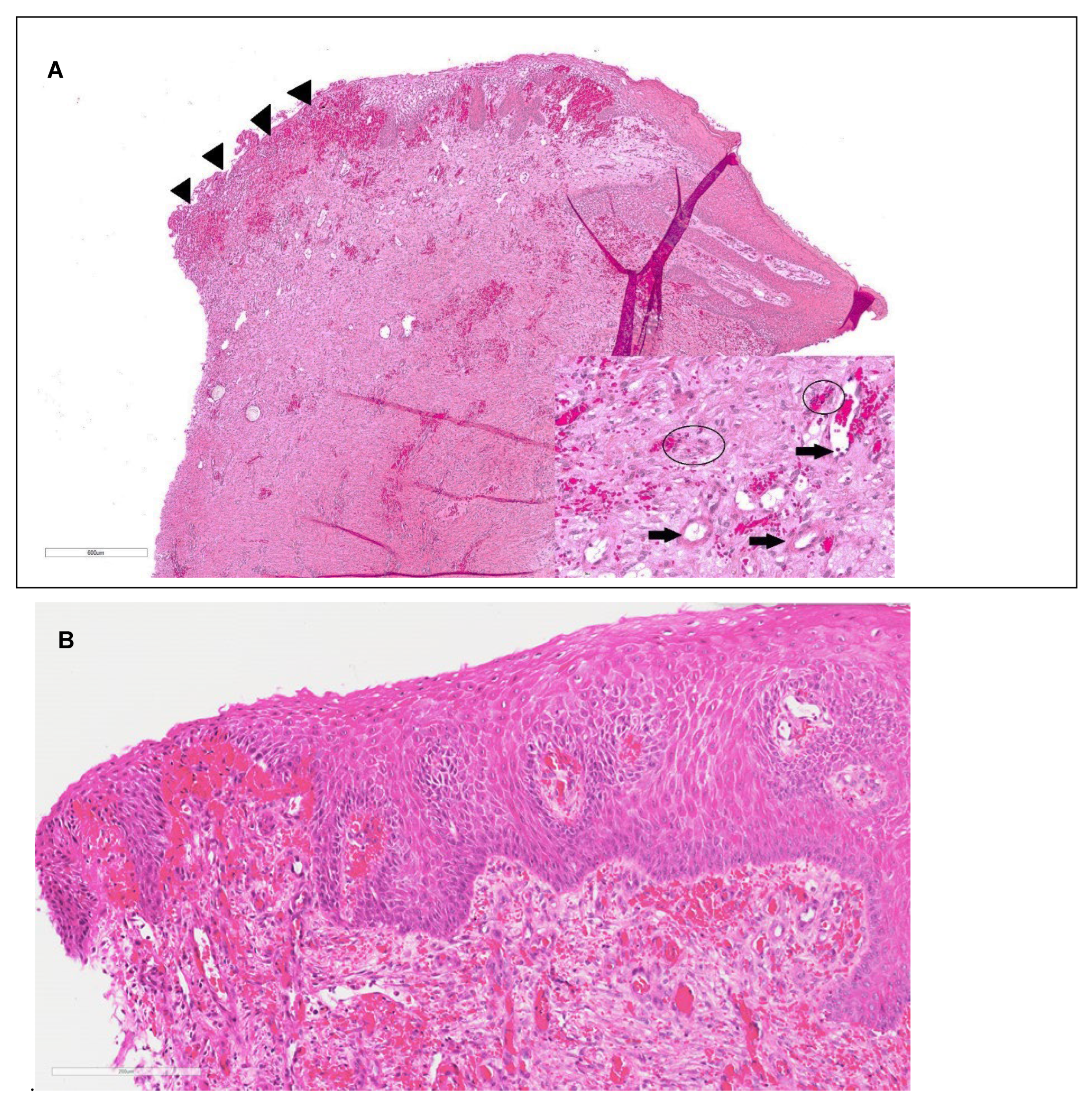

Figure 6.

A. Day 35 Treatment limb histopathology, H and E staining. Re-epithelialization of the wound is incomplete and there is a focally extensive area of ulceration with granulation tissue and hemorrhage (arrow heads). There is fibrosis, vascular proliferation and hemorrhage within the dermis. Hair follicles, adnexal structures, and smooth muscle are absent. H&E stain; bar= 600µm. Inset: Photomicrograph of superficial dermis demonstrating mild neutrophilic and lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (circled), fibrosis, vascular proliferation (arrows) and hemorrhage. B. Control limb biopsy from day 35 showing new epithelialization with mild inflammation, vascularization and hemorrhage. bar= 600µm

Figure 6.

A. Day 35 Treatment limb histopathology, H and E staining. Re-epithelialization of the wound is incomplete and there is a focally extensive area of ulceration with granulation tissue and hemorrhage (arrow heads). There is fibrosis, vascular proliferation and hemorrhage within the dermis. Hair follicles, adnexal structures, and smooth muscle are absent. H&E stain; bar= 600µm. Inset: Photomicrograph of superficial dermis demonstrating mild neutrophilic and lymphoplasmacytic inflammation (circled), fibrosis, vascular proliferation (arrows) and hemorrhage. B. Control limb biopsy from day 35 showing new epithelialization with mild inflammation, vascularization and hemorrhage. bar= 600µm

Figure 7.

Median histopathology scores for wounds over time. From bottom to top of chart and graph: hemorrhage (HEM), inflammation (INF) in green, vascularity (VAS), fibroplasia (FIB), collagen (COL), smooth muscle (MUS), then hair follicles (HAR), glands (GLN), and light blue epithelialization (EPI). Total scores increased with time in both groups. Day 84 total scores were significantly different between groups. The day 240 biopsies were from a single horse, and data are included for general information.

Figure 7.

Median histopathology scores for wounds over time. From bottom to top of chart and graph: hemorrhage (HEM), inflammation (INF) in green, vascularity (VAS), fibroplasia (FIB), collagen (COL), smooth muscle (MUS), then hair follicles (HAR), glands (GLN), and light blue epithelialization (EPI). Total scores increased with time in both groups. Day 84 total scores were significantly different between groups. The day 240 biopsies were from a single horse, and data are included for general information.

Follow-Up:

Histopathology: Additionally, post-mortem tissue was available on day 240 for one horse euthanized for reasons unrelated to the study. Subjectively, there was no difference in histologic appearance of the treatment and control wounds in the post-mortem samples (histologic score of 6 for all wounds). All post-mortem wounds were completely epithelialized with evidence of persistent small nodules of lymphoplasmacytic inflammation in the superficial dermis and free hair shafts surrounded by granulomatous inflammation (furunculosis). Wounds had low numbers of hair follicles and sebaceous glands and very rare apocrine glands. The adnexae that were present were haphazardly oriented with abnormal shape (dysplastic).

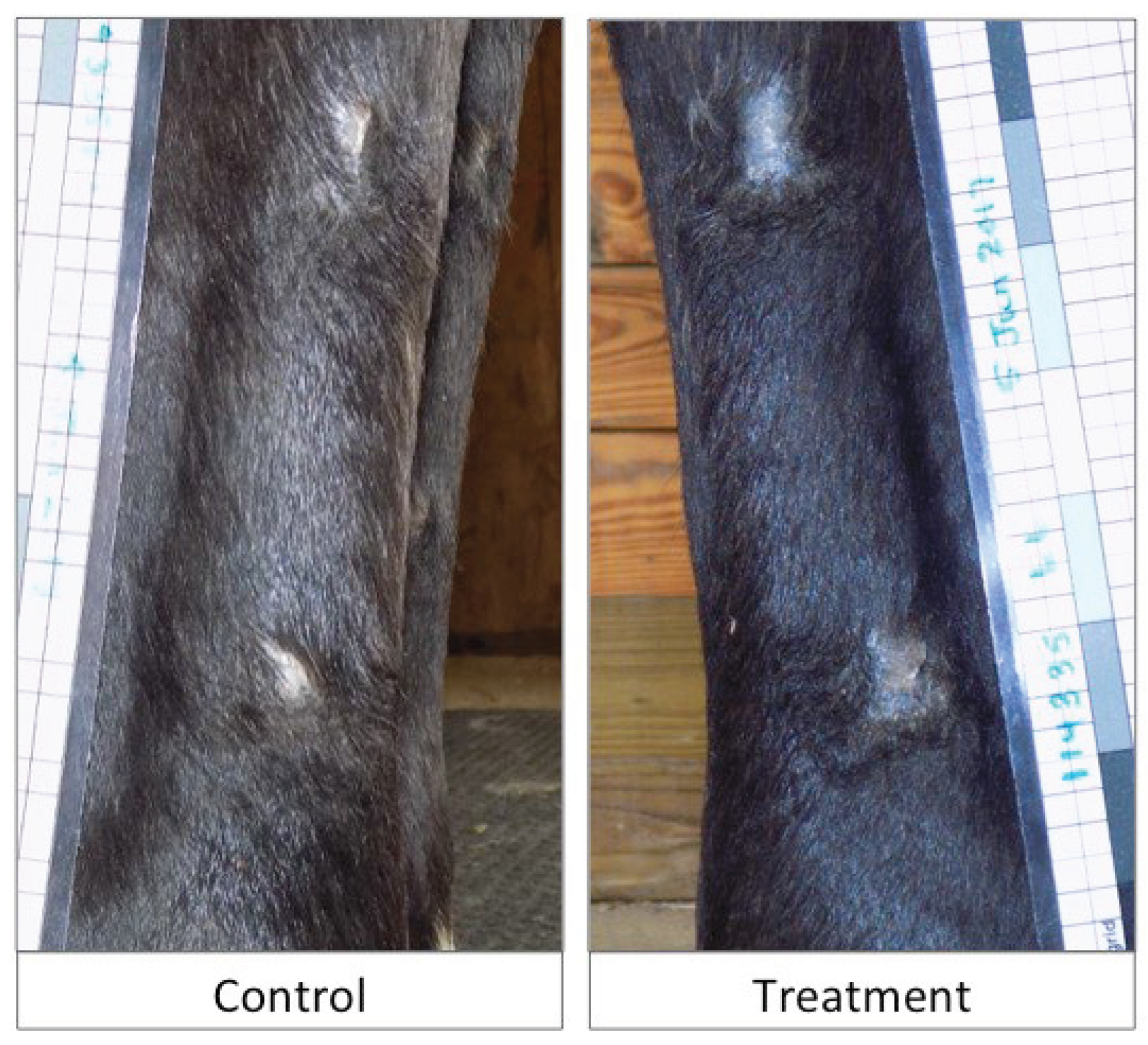

Long Term Outcomes: Wounds were grossly evaluated for each horse in the study at a range of 7-16 months. Two horses were euthanized for reasons unrelated to this study at 7 months and 16 months. One horse was lost to follow-up at 9 months due to adoption, and one horse remained in the institution’s herd and photographic examination was performed 16 months after wounding. During the 99-day study period, both treatment (n=3 wounds, 2 horses) and control (n=5 wounds, 4 horses) wounds were subject to reinjury, with the neoepithelium becoming traumatized and re-wounded. No additional treatment intervention was required. The long-term cosmetic outcome at the time of follow up was similar between treatment and control wounds as assessed through blinded photographic images (

Figure 8).

4. Discussion

The xenogeneic amnion material investigated in this pilot study resulted in slower healing, poorer histological scores, overall increased inflammation histologically, and subjectively excessive inflammation visually in all treated wounds, leading to delayed time to wound closure in this equine distal wound model. This was an unexpected result based on studies using this material in other animal species (porcine and rodent models) [

4]. While this material may be appropriate for non-equine species pending further investigation, it cannot be recommended for use in equine wounds. As a consequence, we terminated the study after this first cohort of 4 horses rather than continuing to study this wound treatment in a second cohort. The results of this pilot study may sway others to avoid use of human-derived tissues in the future, and to carefully assess any xenogeneic tissues commercialized for equine wound treatment.

Previous literature indicates that 2.5cm

2 wounds in the horse’s distal limb wound be expected to heal at a mean of 42-60 days, but one study reports healing times of 83 days or longer [1,2,13−15]. Amnion-treated wounds in equids are expected to heal at a similar [

15] or more rapid [

1,

2] time point compared to control. Variations in results of other equine amnion studies could be related to study design, source or preparation of the amnion, or inadequate sample size. A perfectly designed study of wound healing is not always practical. For example, multiple wounds on the same limb can interfere with healing of other wounds, and applying different treatments to different wounds on the same limb can affect each other and confound results [

11]. We sought to limit confounding factors by using one entire limb as control, treating each limb the same throughout the experiment (except for the presence of amnion), and maintaining at least 3cm distance from the other wounds. Previous equine studies comparing amnion-treated wounds to control have shown variable results. One study found that liquified amnion injection did not improve healing compared with control [

10].

While another study showed that amnion together with pinch grafting improved healing time compared with pinch graft alone [

2]. A third study showed that equine amnion membrane treatment of wounds accelerated granulation tissue formation [

11].

Bandaging has been documented to increase the incidence of exuberant granulation tissue formation, but in this study, exuberant granulation tissue was not encountered. [

16] This could be attributed to the small sample size. Or, exuberant granulation tissue may have been avoided despite bandaging due to the use of triple antibiotic ointment in the inflammatory phase, as triple antibiotic ointment has been shown to decrease the development of exuberant granulation tissue when equine distal limb wounds are bandaged. [

14] In order to avoid the need to trim excess granulation tissue which has occurred in several previous equine distal wound model studies, and to avoid exuberant granulation tissue confounding the results of the study, triple antibiotic ointment was used in both treatment and control wounds. The triple antibiotics ointment also better enabled application of the amnion treatment, and assisted in maintaining blinding of the investigators. That being said, altering the timing of treatment application, comparing to unbandaged wounds, or repeating treatment application at multiple bandage changes may have altered these results.

The tested material caused subjectively substantial edema in the treatment wounds, indicated by focal swelling surrounding the wounds and edema within the granulation tissue on gross visual evaluation by the blinded investigator. This was supported by histologic analysis, revealing overall increased inflammation scores in the treatment wounds. A potential cause for increased inflammation in treatment wounds could be graft rejection of the xenogeneic material. Th1 lymphocytes, for example, promote cytotoxic killing and are prominent in graft rejection reactions [

17]. Further investigation and analysis of leukocyte infiltration of amnion-treated wounds may have determined the source of the increased inflammation, but this was outside the scope of this study. The wounds were not submitted for bacterial culture or bacterial quantification, so bacterial contamination cannot be ruled out as the cause of increased inflammation in treated wounds compared with control.

One horse had a complication (cellulitis) in the treatment limb after wound creation and treatment application. It cannot be definitively determined that the cellulitis in this horse was due to the amnion-derived material, but this must be considered. The horse also required additional local anesthesia to complete the wounding procedure, which may increase risk of cellulitis due to repeated needle penetrations of the skin, but this was needed bilaterally and the control limb (which was the second limb) did not develop cellulitis [

18].

It is not known if the investigated material would produce a similar inflammatory reaction in humans. Previous research on this material in a porcine model showed no inflammatory reaction and resulted in accelerated healing times [

5]. An equine model was chosen for this study due to the poor healing of wounds on the equine distal limb and the propensity for horses to produce unwanted exuberant granulation tissue, which has similarities to keloid formation in humans [

14,

16,

19,

20].

The limitations of this study include the small number of horses used, the use of local anesthesia for wound creation and biopsies, using one wound location for two biopsies, the use of triple antibiotic ointment and bandaging in both control and treated limbs, and the inclusion of a horse that had cellulitis. The small number of horses was due to the investigators’ opting to terminate the study due to the strong suspicion that the treatment may not be beneficial. This suspicion was due to one limb appearing more inflamed in every horse, without the actual knowledge of which was treatment and which was control. It also subjectively seemed that the degree of inflammation was higher in one leg in each horse than these surgeons would expect for a similar naturally occurring wound.

Based on this suspicion, data analysis and unblinding was performed. The discovery that the treated limbs did not show significant improvement over control, and showed significantly slower wound closure at some time points compared with control resulted in termination of the study. The horse with cellulitis in the amnion-treated limb was included due to the concern it was related to the treatment. Previous studies on equine distal limb wound healing have used between 1 and 18 horses, with a range of 1 to 6 wounds per limb [10,13,16,21−23]. While this study was limited to only 4 horses, there were statistically significant differences that suggested human amnion may not be beneficial, and may actually hinder healing.

General anesthesia was avoided due to potential complications and increased cost for the study. Additionally, performing a bilateral model was thought to avoid interference of local anesthetic, triple antibiotic use and bandaging on results. The investigators could have performed fewer biopsies to avoid using the same wound twice for day 7 and day 21 biopsy. Using each wound for a single biopsy would avoid the potential of interference on healing. It is possible that the day 7 biopsy would interfere with healing, and this could affect the histology results for the day 21 biopsies. Since there were no significant differences in biopsy scores on day 7 or 35, this may not be relevant. The long-term outcome of the research horses (follow-up) was included to allow future investigators using this model to know the impact of this non-terminal study on our research herd.

The safety of this human amnion material for use in the horse is challenged by the findings of this study. Increased inflammation of the wounds during healing, slower closure of the wounds and development of cellulitis on the treated limb in one horse all suggest that this amnion preparation is not an appropriate treatment for equine wounds. Due to these adverse effects, and the potential that horses are more sensitive to xenogeneic materials on wounds, the authors suggest conducting similar studies to this for any xenogeneic material being marketed for use in horses, even as a medical device. There are currently porcine and bovine tissues being marketed for use in horses. There remains ample evidence in the literature of the positive effects of equine (allogeneic) amniotic membrane for use in equine wound healing. Further investigation of allogeneic, equine-derived amniotic membrane processed in a similar manner would be ideal.

5. Conclusions

The xenogeneic amnion material investigated in this pilot study is not recommended for use on equine wounds. The material subjectively appeared to induce an inflammatory response, resulting in edema in the wounds and reduced wound closure, which was significant at a number of time points. In addition, one horse had an adverse response that may be attributed to the material resulting in cellulitis of the treated limb. The effects of topical application of this material in other species cannot be determined with this study. Careful study of any other xenogeneic materials for wound healing in horses is recommended.

Author Contributions

JB and SM contributed to conception of the study; CM and JB contributed design of the study. CM and JB carried out the study and data collection. CM and JB performed the statistical analysis. EE performed histopathologic analysis, interpretation and wrote associated sections of the manuscript. CM wrote the remainder of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Wake Forest Institute of Regenerative Medicine/Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine Center for One Health Regenerative Medicine Research Program.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Drs. Nathaniel White and Christopher Byron for review of this topic as master’s thesis committee members, and Elaine Meilahn for assistance with horse care and procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

IACUC Approval

All procedures and care of the horses used in this study were approved, monitored, and regulated by the Virginia Tech Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All horses were donated to Virginia Tech with owner informed consent.

References

- Bigbie RB, Schumacher J, Swaim SF, et al: Effects of amnion and live yeast cell derivative on second-intention healing in horses. Am J Vet Res 52:1376-1382, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Goodrich LR, Moll HD, Crisman MV, et al: Comparison of equine amnion and a nonadherent wound dressing material for bandaging pinch-grafted wounds in ponies. Am J Vet Res 61:326-329, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Favaron PO, Carvalho RC, Borghesi J, et al: The Amniotic Membrane: Development and Potential Applications - A Review. Reprod Domest Anim 50:881-892, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kakabadze Z, Mardaleishvili K, Loladze G, et al: Clinical application of decellularized and lyophilized human amnion/chorion membrane grafts for closing post-laryngectomy pharyngocutaneous fistulas. J Surg Oncol 113:538-543, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Murphy SV: 2017 TERMIS - Americas Conference & Exhibition Charlotte, NC December 3-6, 2017, Proceedings, Tissue Eng Part A, Dec, 2017 (available from.

- McQuilling JP, Vines JB, Mowry KC: In vitro assessment of a novel, hypothermically stored amniotic membrane for use in a chronic wound environment. Int Wound J 14:993-1005, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ares MT, Lopez-Valladares MJ, Tourino R, et al: Effects of lyophilization on human amniotic membrane. Acta Ophthalmol 87:396-403, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Russo A, Bonci P, Bonci P: The effects of different preservation processes on the total protein and growth factor content in a new biological product developed from human amniotic membrane. Cell Tissue Bank 13:353-361, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Tehrani FA, Ahmadiani A, Niknejad H: The effects of preservation procedures on antibacterial property of amniotic membrane. Cryobiology 67:293-298, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Duddy HR, Schoonover MJ, Williams MR, et al: Healing time of experimentally induced distal limb wounds in horses is not reduced by local injection of equine-origin liquid amnion allograft. Am J Vet Res 83, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fowler AW, Gilbertie JM, Watson VE, et al: Effects of acellular equine amniotic allografts on the healing of experimentally induced full-thickness distal limb wounds in horses. Vet Surg 48:1416-1428, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Moyer W, Moyer W: Equine joint injection and regional anesthesia (ed 5th). Chadds Ford, PA, Academic Veterinary Solutions, LLC, 2011.

- Kelleher ME, Kilcoyne I, Dechant JE, et al: A preliminary study of silver sodium zirconium phosphate polyurethane foam wound dressing on wounds of the distal aspect of the forelimb in horses. Vet Surg 44:359-365, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Harmon CCG, Hawkins JF, Li J, et al: Effects of topical application of silver sulfadiazine cream, triple antimicrobial ointment, or hyperosmolar nanoemulsion on wound healing, bacterial load, and exuberant granulation tissue formation in bandaged full-thickness equine skin wounds. Am J Vet Res 78:638-646, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Howard RD, Stashak TS, Baxter GM: Evaluation of occlusive dressings for management of full-thickness excisional wounds on the distal portion of the limbs of horses. Am J Vet Res 54:2150-2154, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Berry DB, 2nd, Sullins KE: Effects of topical application of antimicrobials and bandaging on healing and granulation tissue formation in wounds of the distal aspect of the limbs in horses. Am J Vet Res 64:88-92, 2003.

- Badylak SF, Gilbert TW: Immune response to biologic scaffold materials. Semin Immunol 20:109-116, 2008.

- Auer JA, Stick JA: Equine surgery (ed 4th). St. Louis, Mo., Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

- Jorgensen E, Bay L, Bjarnsholt T, et al: The occurrence of biofilm in an equine experimental wound model of healing by secondary intention. Vet Microbiol 204:90-95, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Wilmink JM, Stolk PW, van Weeren PR, et al: Differences in second-intention wound healing between horses and ponies: macroscopic aspects. Equine Vet J 31:53-60, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Carter CA, Jolly DG, Worden CE, Sr., et al: Platelet-rich plasma gel promotes differentiation and regeneration during equine wound healing. Exp Mol Pathol 74:244-255, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Labens R, Raidal S, Borgen-Nielsen C, et al: Wound healing of experimental equine skin wounds and concurrent microbiota in wound dressings following topical propylene glycol gel treatment. Front Vet Sci 10:1294021, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Charlotte CP, Benoit B, Olivier ML: The effects of a synthetic epidermis spray on secondary intention wound healing in adult horses. PLoS One 19:e0299990, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).