Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

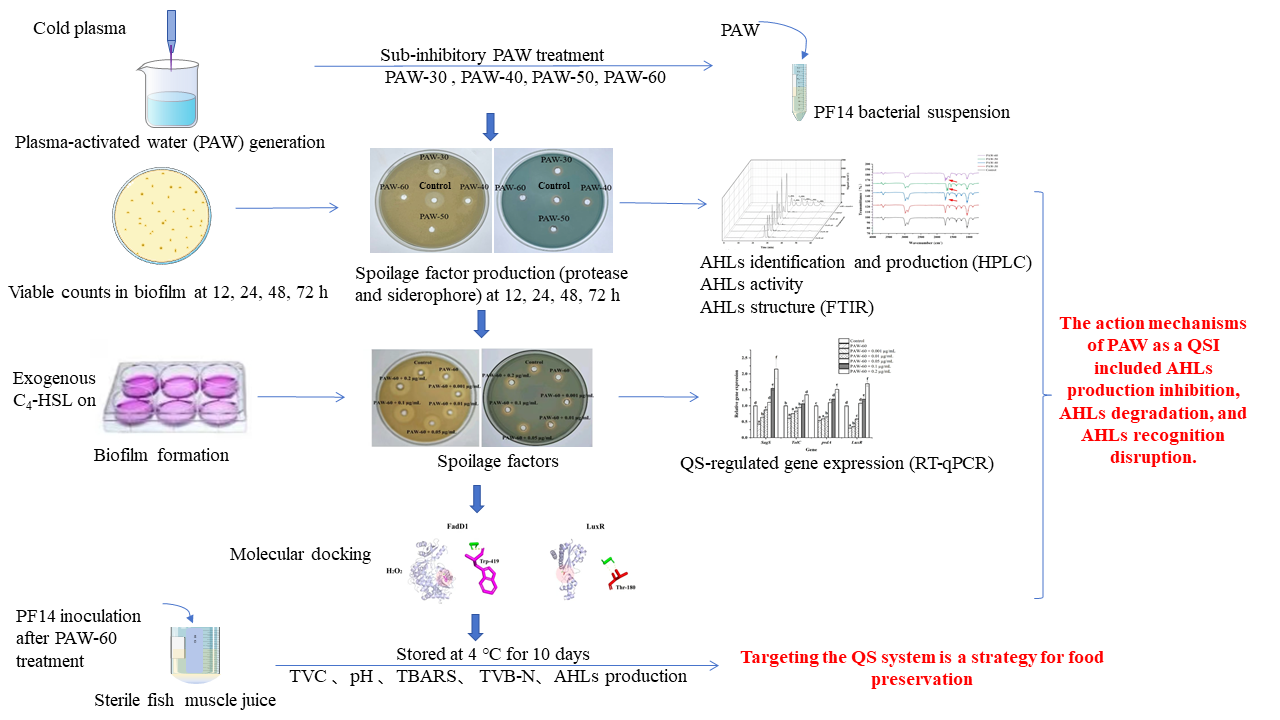

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Culture Preparation

2.2. PAW Generation Under Sub-Inhibitory Conditions

2.3. Enumeration of Bacterial Cells in Biofilm

2.4. Spoilage Factors Assay

2.5. AHLs Production Assay

2.6. AHLs Activity Assay

2.7. AHLs Structure Assay

2.8. Determination of Biofilm Formation with Exogenous C4-HSL

2.9. Determination of Spoilage Factors with Exogenous C4-HSL

2.10. Determination of Gene Expression with Exogenous C4-HSL

2.11. Molecular Docking

2.12. In Vivo Spoilage Potential of P. fluorescens in Fish Muscle Juice Assay

2.12.1. Fish Muscle Juice Contamination

2.12.2. TVC and pH Analysis

2.12.3. TBARS and TVB-N Analysis

2.12.4. AHLs Production Analysis

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

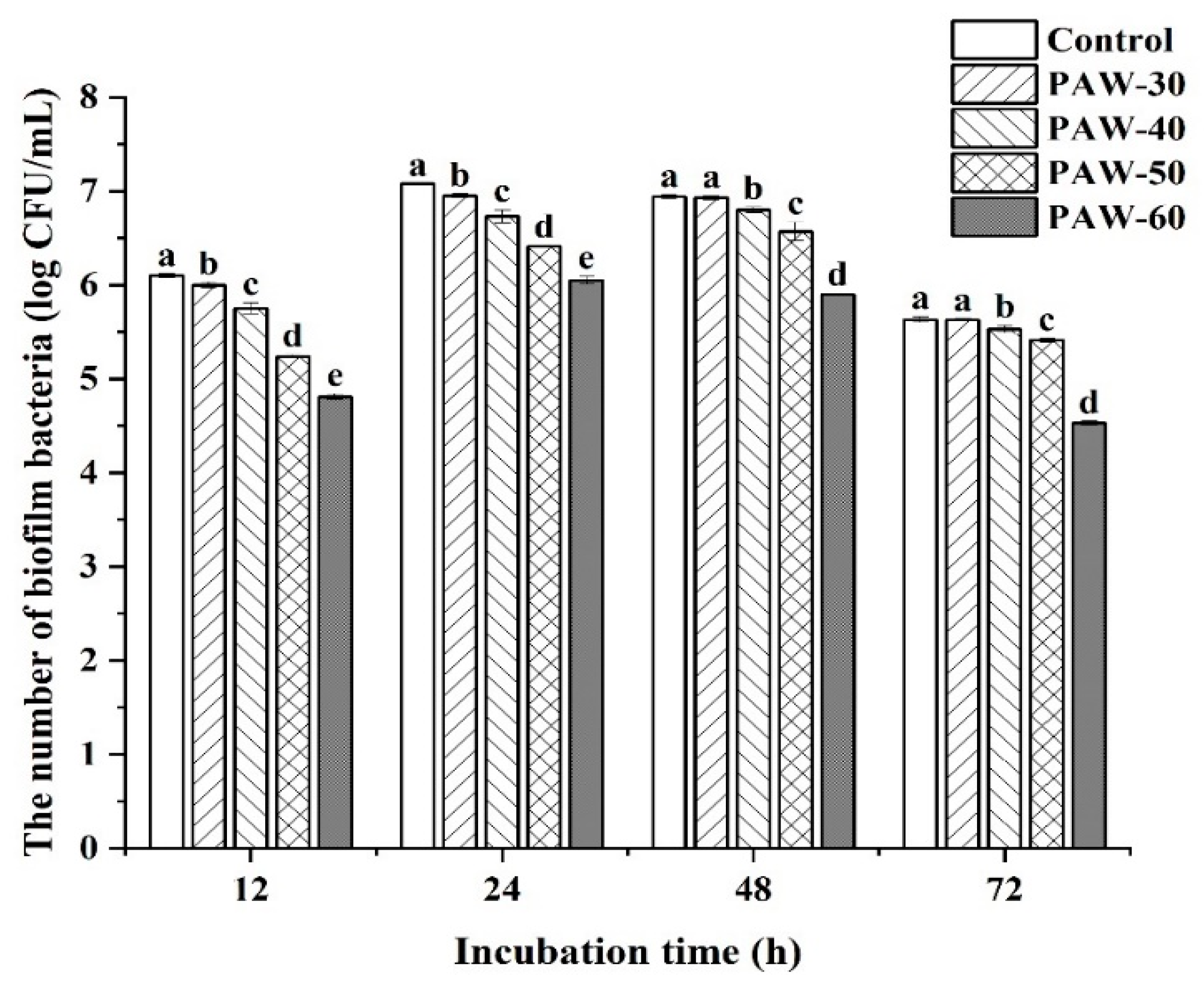

3.1. The Effect of PAW on Biofilm Biomass

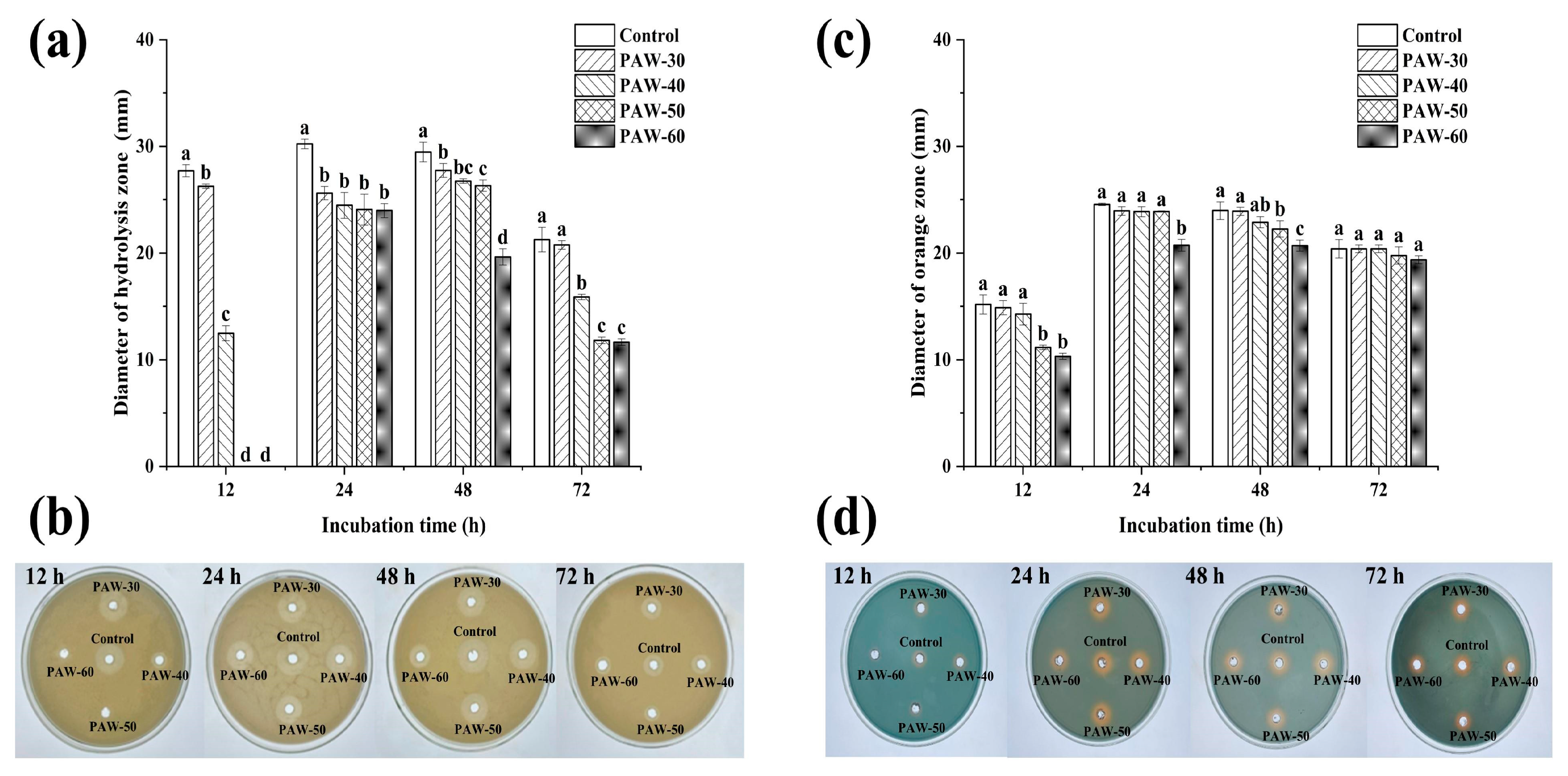

3.2. The Effect of PAW on Spoilage Factors

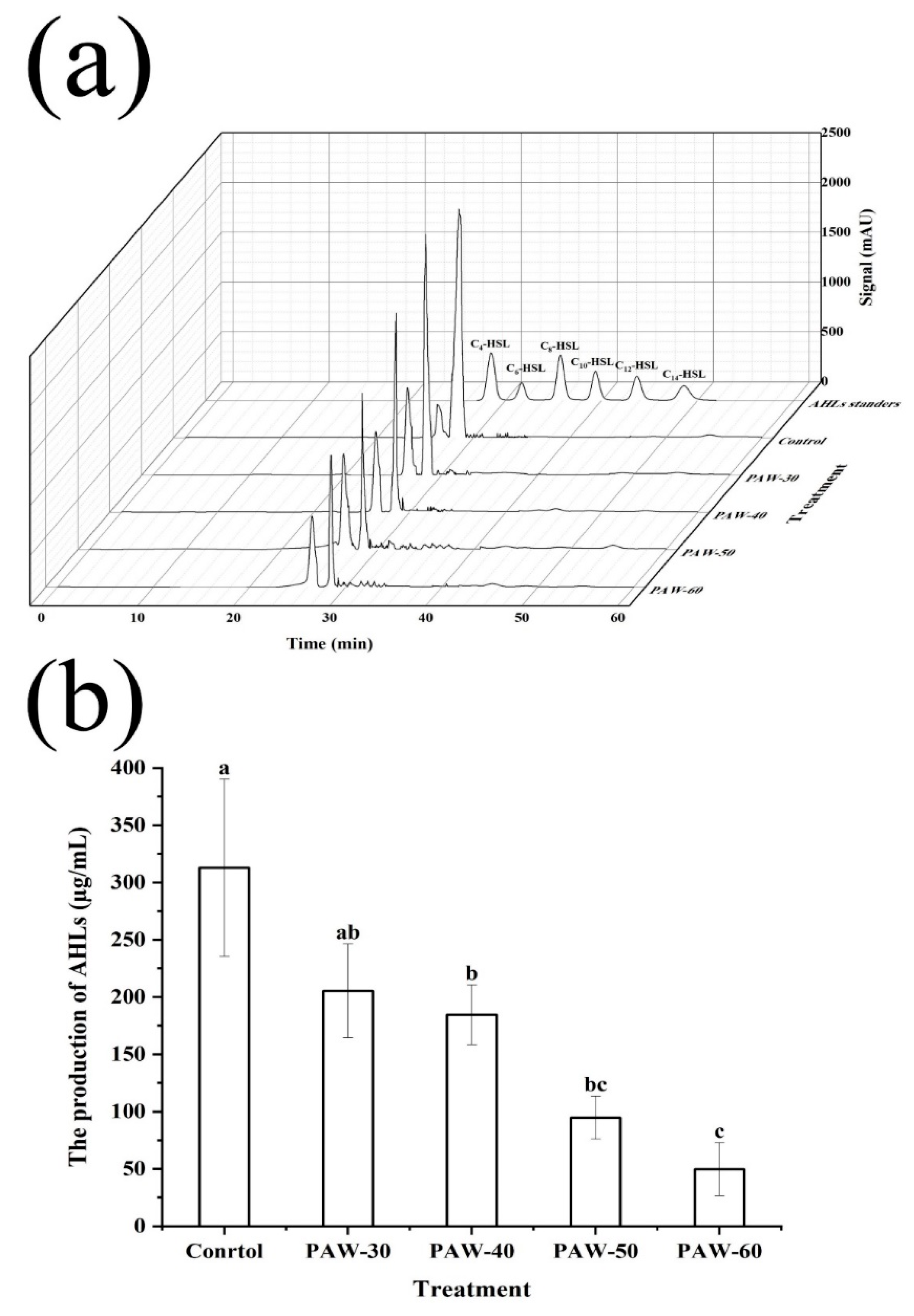

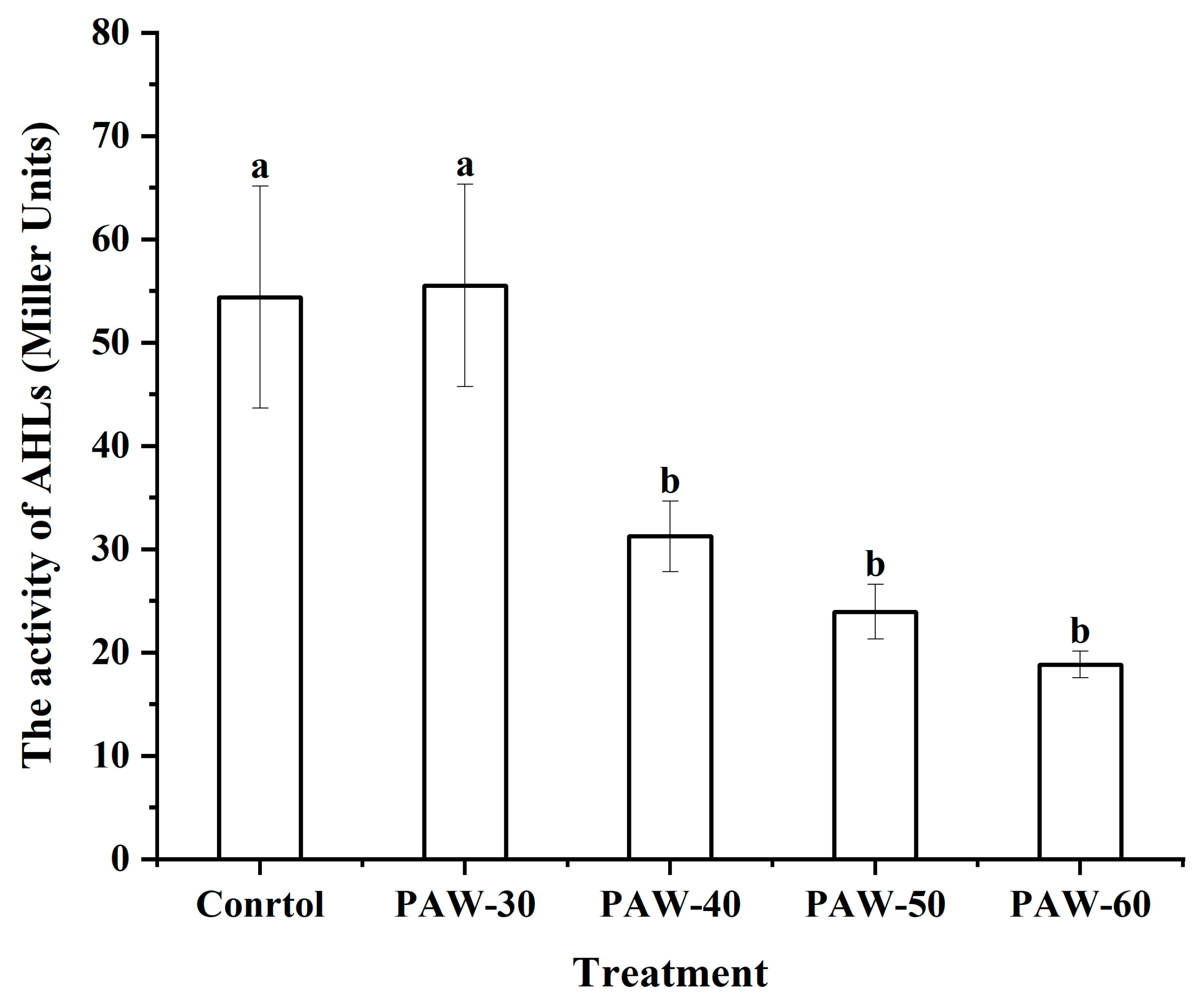

3.3. The Effect of PAW on AHLs Production of PF14

3.4. The Effect of PAW on AHLs Activity of PF14

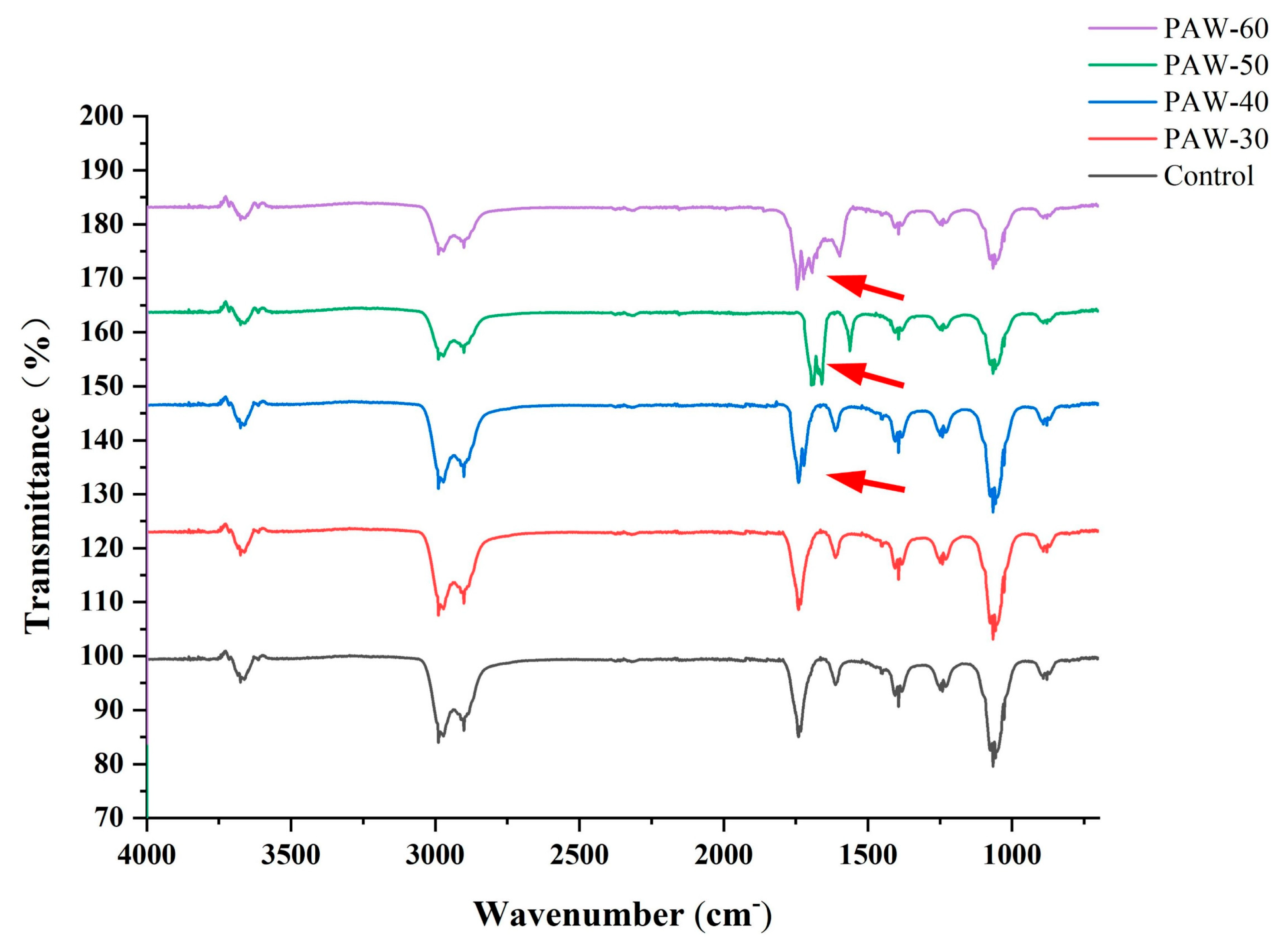

3.5. The Effect of PAW on C4-HSL Structure

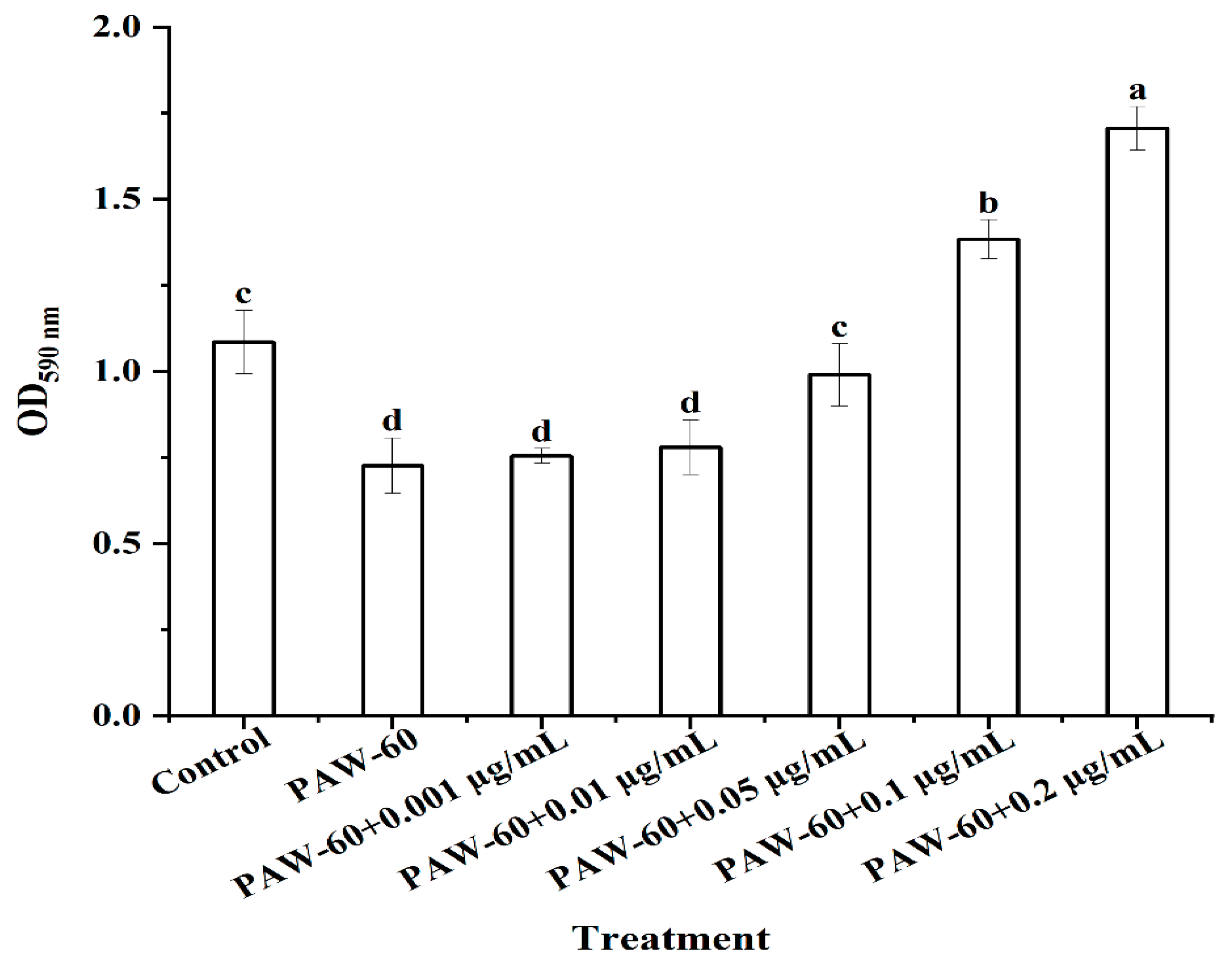

3.6. The Effect of Exogenous C4-HSL on the Biofilm Formation of PF14

3.7. The Effect of Exogenous C4-HSL on the Spoilage Factors of PF14

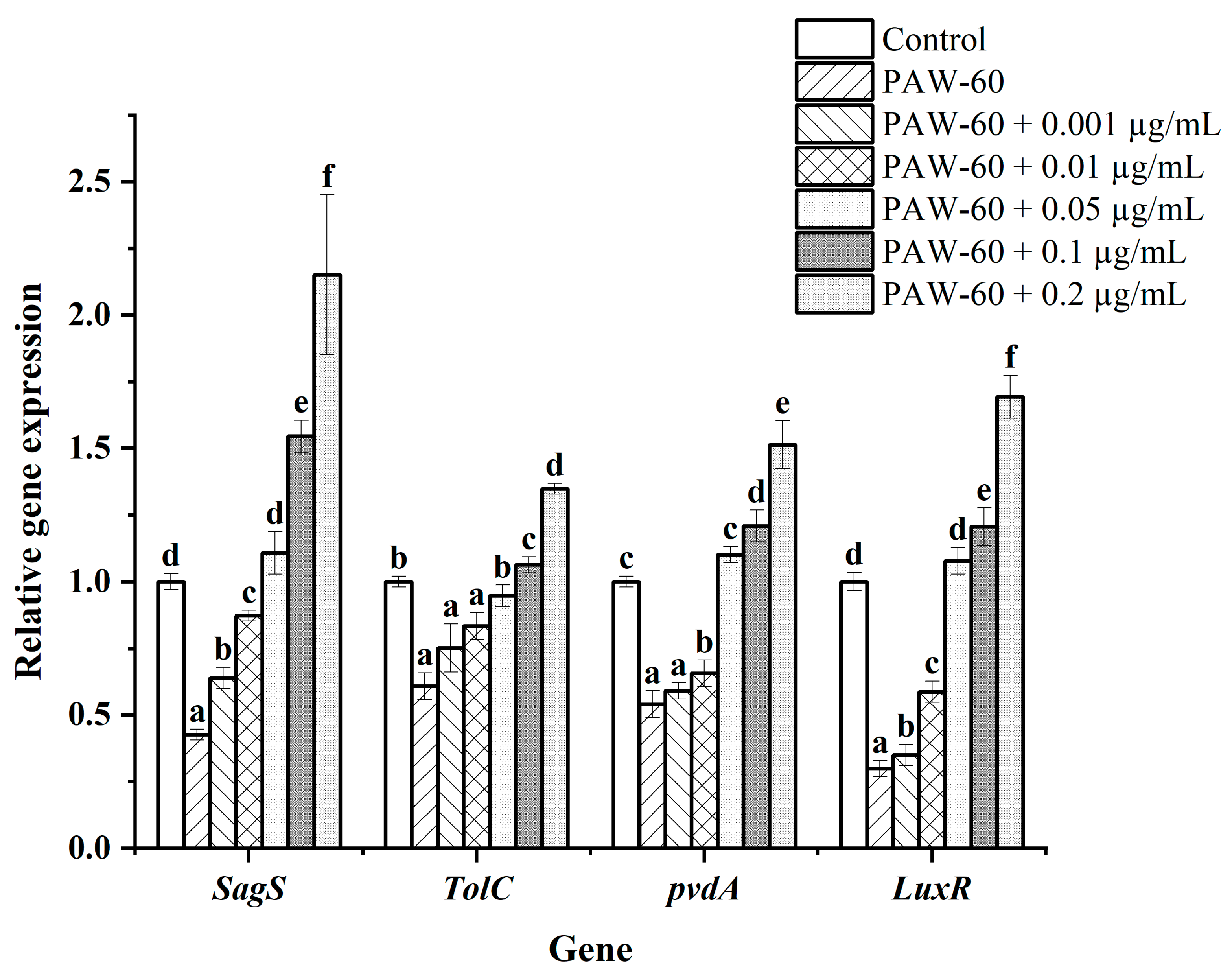

3.8. The Effect of Exogenous C4-HSL on the Gene Expression of PF14

3.9. Molecular Docking Analysis

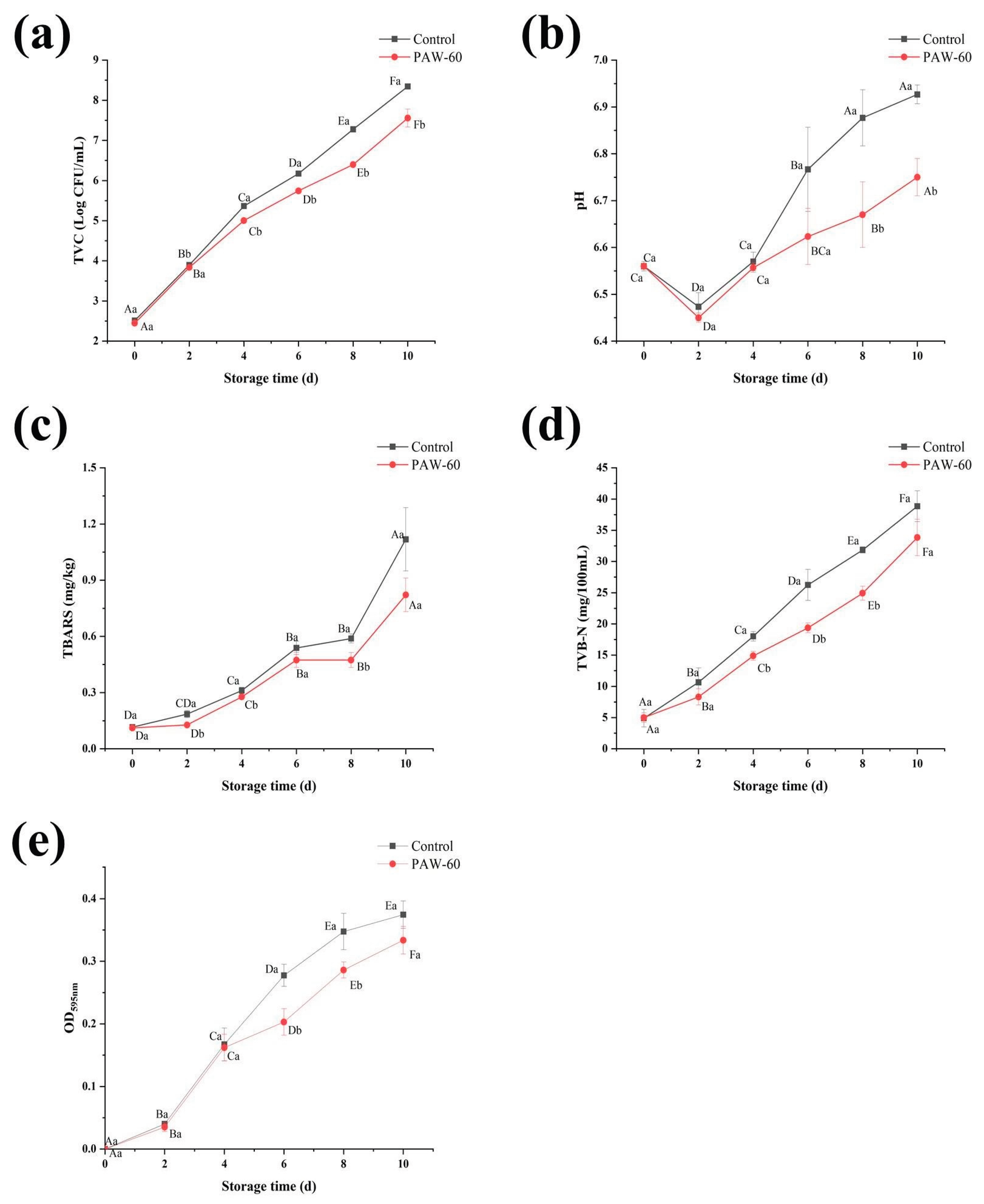

3.10. The Effect of PAW on the Spoilage Potential of PF14 in Fish Muscle Juice

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alonso, V. P. P., M. M. Furtado, C. H. T. Iwase, J. Z. Brondi-Mendes, and M. d. S. Nascimento. 2024. Microbial resistance to sanitizers in the food industry. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 64, 3: 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, N., M. Zarei, M. Kargar, and F. Kafilzadeh. 2023. Effect of plasma-activated water on the biofilm-forming ability of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis and expression of the related genes. International journal of food microbiology 406, 110419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassler, B. L. 1999. How bacteria talk to each other: regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing. Current opinion in microbiology 2, 6: 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z., W. Zhang, G. Liao, C. Huang, J. Wang, and J. Zhang. 2025. Inhibiting mechanism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation-An innovational reagent of plasma-activated lactic acid. Journal of Water Process Engineering 69, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanioti, S., M. Giannoglou, P. Stergiou, and et al. 2023. Plasma-activated water for disinfection and quality retention of sea bream fillets: Kinetic evaluation and process optimization. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 85, 103334. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Z. Sun, and J. Jin. 2023. Role of siderophore in Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilm formation and spoilage potential function. Food microbiology 109, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, P. K., N. Keshavan, H. Q. Nguyen, J. A. Peterson, J. E. González, and D. C. Haines. 2007. Bacillus megaterium CYP102A1 oxidation of acyl homoserine lactones and acyl homoserines. Biochemistry 46, 50: 14429–14437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F., Q. Wang, J. Liu, D. Wang, J. Li, and T. Li. 2023. Effects of deletion of siderophore biosynthesis gene in Pseudomonas fragi on quorum sensing and spoilage ability. International journal of food microbiology 396, 110196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H., H. Li, M. A. Abdel-Samie, D. Surendhiran, and L. Lin. 2021. Anti-Listeria monocytogenes biofilm mechanism of cold nitrogen plasma. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 67, 102571. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard, P. 1995. Qualitative and quantitative characterization of spoilage bacteria from packed fish. International journal of food microbiology 26, 3: 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, T., T. Li, Z. Wang, and J. Li. 2017. Curcumin liposomes interfere with quorum sensing system of Aeromonas sobria and in silico analysis. Scientific reports 7, 1: 8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidaleo, M., A. Zuorro, and R. Lavecchia. 2013. Enhanced antibacterial and anti-quorum sensing activities of triclosan by complexation with modified β-cyclodextrins. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 29, 9: 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, P. B., A. Busetti, E. Wielogorska, and et al. 2016. Non-thermal Plasma Exposure Rapidly Attenuates Bacterial AHL-Dependent Quorum Sensing and Virulence. Sci Rep 6, 1: 26320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R. L., L. He, Y. Cui, and et al. 2010. Reaction of N-acylhomoserine lactones with hydroxyl radicals: rates, products, and effects on signaling activity. Environmental science & technology 44, 19: 7465–7469. [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua, C., and E. P. Greenberg. 2002. Listening in on bacteria: acyl-homoserine lactone signalling. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 3, 9: 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J., M. Mukaddas, Y. Tao, H. Liu, K. Ye, and G. Zhou. 2024. High-voltage electrostatic field with 35 kV-15 min could reduce Pseudomonas spp. to maintain the quality of pork during− 1° C storage. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 94, 103700. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z., X. Du, and J. Liu. 2024. Benzyl isothiocyanate suppresses biofilms and virulence factors as a quorum sensing inhibitor in Pseudomonas fluorescens. LWT 204, 116387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M., R. Wu, L. Liu, S. Wang, L. Zhang, and P. Li. 2017. Effects of quorum quenching by AHL lactonase on AHLs, protease, motility and proteome patterns in Aeromonas veronii LP-11. International journal of food microbiology 252, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, N., X. Bai, Y. Shen, and T. Zhang. 2023. Target-based screening for natural products against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 63, 14: 2216–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Pacheco, M. M., A. T. Bernal-Mercado, F. J. Vazquez-Armenta, and et al. 2019. Quorum sensing interruption as a tool to control virulence of plant pathogenic bacteria. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 106, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahid, I. K., M. F. R. Mizan, A. J. Ha, and S.-D. Ha. 2015. Effect of salinity and incubation time of planktonic cells on biofilm formation, motility, exoprotease production, and quorum sensing of Aeromonas hydrophila. Food microbiology 49, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V. C. 2013. Quorum sensing inhibitors: an overview. Biotechnology advances 31, 2: 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, X., W. Lan, S. Liu, and X. Sun. 2025. Quorum sensing inhibitory of plant extracts on specific spoilage organisms and the potential utilization on the preservation of aquatic products. Chemical Engineering Journal 506, 160259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P., J. Mei, and J. Xie. 2022. Carbon dioxide can inhibit biofilms formation and cellular properties of Shewanella putrefaciens at both 30° C and 4° C. Food Research International 161, 111781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T., X. Sun, and H. Chen. 2020. Methyl anthranilate: a novel quorum sensing inhibitor and anti-biofilm agent against Aeromonas sobria. Food microbiology 86, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T., D. Wang, and N. Liu. 2018. Inhibition of quorum sensing-controlled virulence factors and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens by cinnamaldehyde. International journal of food microbiology 269, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. T., F. C. Cui, F. L. Bai, G. H. Zhao, and J. R. Li. 2016. Involvement of Acylated Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) of Aeromonas sobria in Spoilage of Refrigerated Turbot Scophthalmus maximus. SENSORS 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., J. Pan, D. Wu, Y. Tian, J. Zhang, and J. Fang. 2019. Regulation of Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation and quorum sensing related virulence factors with ultra-low dose reactive species produced by plasma activated water. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing 39, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X., Y. Su, and D. Liu. 2018. Application of atmospheric cold plasma-activated water (PAW) ice for preservation of shrimps (Metapenaeus ensis). Food Control 94, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L., P. Zhang, and X. Chen. 2023. Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms by poly-L-aspartic acid nanoparticles loaded with Litsea cubeba essential oil. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 242, 124904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Y. Wang, P. Yang, and et al. 2025. Quality decline of prepared dishes stored at 4° C: Microbial regulation of nitrite and biogenic amine formation. Food microbiology 128, 104730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., J. Li, M. Tu, and et al. 2024. Complete genome sequence provides information on quorum sensing related spoilage and virulence of Aeromonas salmonicida GMT3 isolated from spoiled sturgeon. Food Research International 196, 115039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L., M. E. Hume, and S. D. Pillai. 2005. Autoinducer-2–like activity on vegetable produce and its potential involvement in bacterial biofilm formation on tomatoes. Foodbourne Pathogens & Disease 2, 3: 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, I., L. R. Silva, E. D. Giaouris, L. F. Melo, and M. Simões. 2020. Quorum sensing in food spoilage and natural-based strategies for its inhibition. Food Research International 127, 108754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. B., and B. L. Bassler. 2001. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annual Reviews in Microbiology 55, 1: 165–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, D., M. Suar, and S. K. Panda. 2025. Nanotechnological interventions in bacteriocin formulations–advances, and scope for challenging food spoilage bacteria and drug-resistant foodborne pathogens. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 65, 6: 1126–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. R. R., P. Pohokar, and A. Das. 2025. Chalcone derivative enhance poultry meat preservation through quorum sensing inhibition against Salmonella (Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi) contamination. Food Control 171, 111155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., F. Cui, D. Wang, T. Li, and J. Li. 2021. Quorum quenching enzyme (pf-1240) capable to degrade ahls as a candidate for inhibiting quorum sensing in food spoilage bacterium Hafnia alvei. Foods 10, 11: 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R., J. Zhu, L. Feng, J. Li, and X. Liu. 2019. Characterization of LuxI/LuxR and their regulation involved in biofilm formation and stress resistance in fish spoilers Pseudomonas fluorescens. International journal of food microbiology 297, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., F. Cui, L. Ren, J. Li, and T. Li. 2023. Quorum-quenching enzymes: Promising bioresources and their opportunities and challenges as alternative bacteriostatic agents in food industry. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 22, 2: 1104–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Y. Wang, J. Chen, and et al. 2021. Screening and preservation application of quorum sensing inhibitors of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Shewanella baltica in seafood products. LWT 149, 111749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., L. Ni, and C. Du. 2024. Decoding Microcystis aeruginosa quorum sensing through AHL-mediated transcriptomic molecular regulation mechanisms. Science of the Total Environment 926, 172101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., S. Liu, and X. Liu. 2025. Novel quorum-sensing inhibitor peptide SF derived from Penaeus vannamei myosin inhibits biofilm formation and virulence factors in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. LWT, 117542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., W. Lan, and X. Sun. 2024. Effects of chlorogenic acid-grafted-chitosan on biofilms, oxidative stress, quorum sensing and c-di-GMP in Pseudomonas fluorescens. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 273, 133029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L., Y. Zhang, F. Azi, and et al. 2022. Inhibition of biofilm formation and quorum sensing by soy isoflavones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Food Control 133, 108629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., J. Kong, F. Huang, and et al. 2018. Hexanal as a QS inhibitor of extracellular enzyme activity of Erwinia carotovora and Pseudomonas fluorescens and its application in vegetables. Food Chem 255, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y., H. Yu, Y. Xie, Y. Guo, Y. Cheng, and W. Yao. 2023. Inhibitory effects of hexanal on acylated homoserine lactones (AHLs) production to disrupt biofilm formation and enzymes activity in Erwinia carotovora and Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Food Sci Technol 60, 1: 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D., Y. Ding, W. Chen, J. Hu, and X. Zhou. 2021. AHLs Based Quorum Sensing in Aeromonas veronii bv.veronii and Its Interruption from Garlic Extract. Journal of Chinese Institute Of Food Science and Technology 21, 2: 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.-M., M. de Alba, D.-W. Sun, and B. Tiwari. 2019. Principles and recent applications of novel non-thermal processing technologies for the fish industry—A review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 59, 5: 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.-M., L. Zhang, Y. Bao, and et al. 2025. The inhibitory mechanisms of plasma-activated water on biofilm formation of Pseudomonas fluorescens by disrupting quorum sensing. In Food Research International. p. 117436. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. M., S. Ojha, C. Burgess, D. W. Sun, and B. Tiwari. 2020a. Inactivation efficacy and mechanisms of plasma activated water on bacteria in planktonic state. Journal of applied microbiology 129, 5: 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. M., A. Patange, D. W. Sun, and B. Tiwari. 2020b. Plasma-activated water: Physicochemical properties, microbial inactivation mechanisms, factors influencing antimicrobial effectiveness, and applications in the food industry. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 19, 6: 3951–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | 16S rRNA-F | GGAATCTGCCTGGTAGTGGG |

| 16S rRNA-R | CAGTTACGGATCGTCGCCTT | |

| SagS | sagS-F | GCTGAACTCGCTCAGGAACT |

| sagS-R | TGGCGCCAAACAGAAAATCG | |

| TolC | TolC-F | AACCGATTTGGTCAGCGTCT |

| TolC-R | CTTGTTCGTTGACGGCTTCG | |

| pvdA | pvdA-F | CCTGGTGACCCAGAGTGAAC |

| pvdA-R | GAGATCACACGCAACGCTTC | |

| LuxR | LuxR-F | GTGCCAACGCTATGCTGAAC |

| LuxR-R | TGCGATCCAAACAATGGCAC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).