Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 60E05; 60E10

1. Introduction

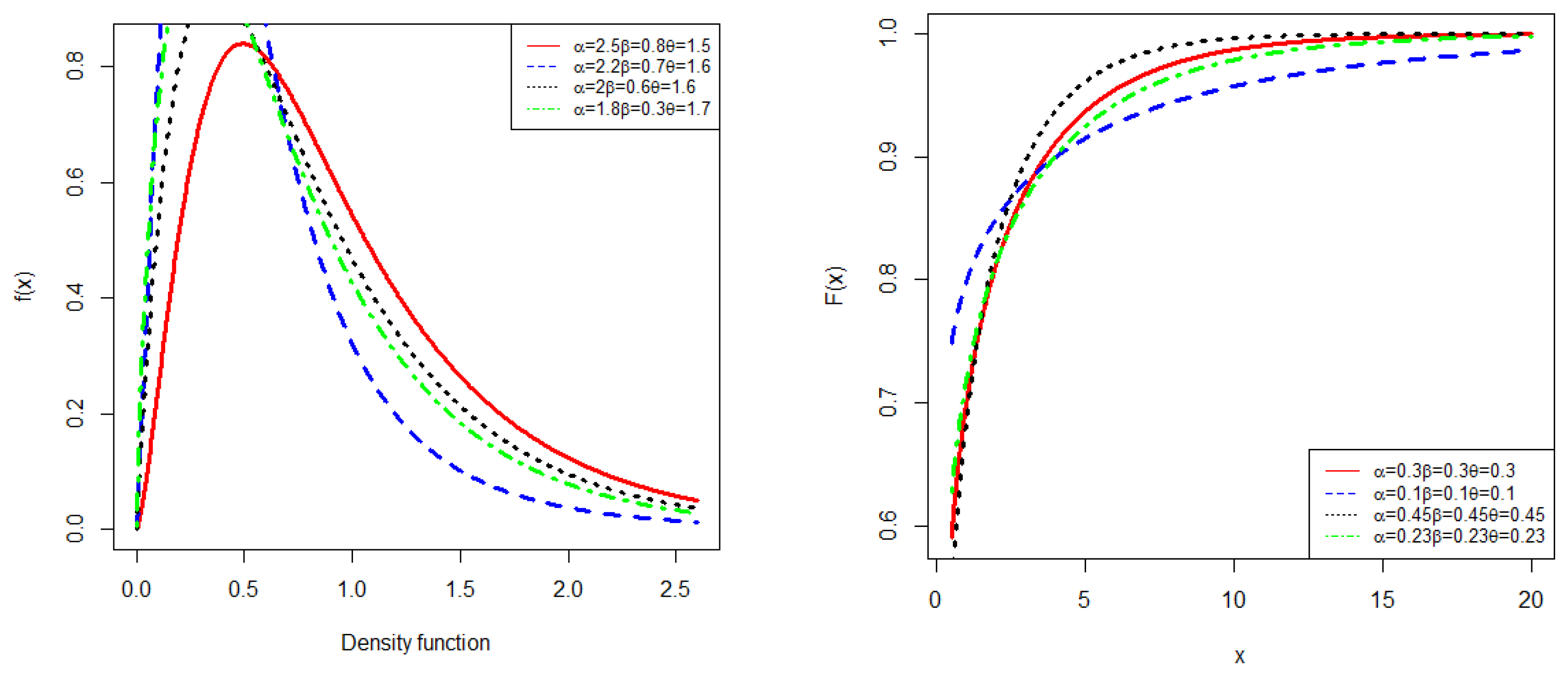

2. Exponent Beta Exponential (EBE) Distribution

2.1. Quantile Function

2.2. Mode

2.3. rth Raw Moment

2.4. Moment Generating Function

2.5. Order Statistics

2.6. Stress-Strength Parameter (SSP)

2.7. Parameter Estimations

3. Simulations Study

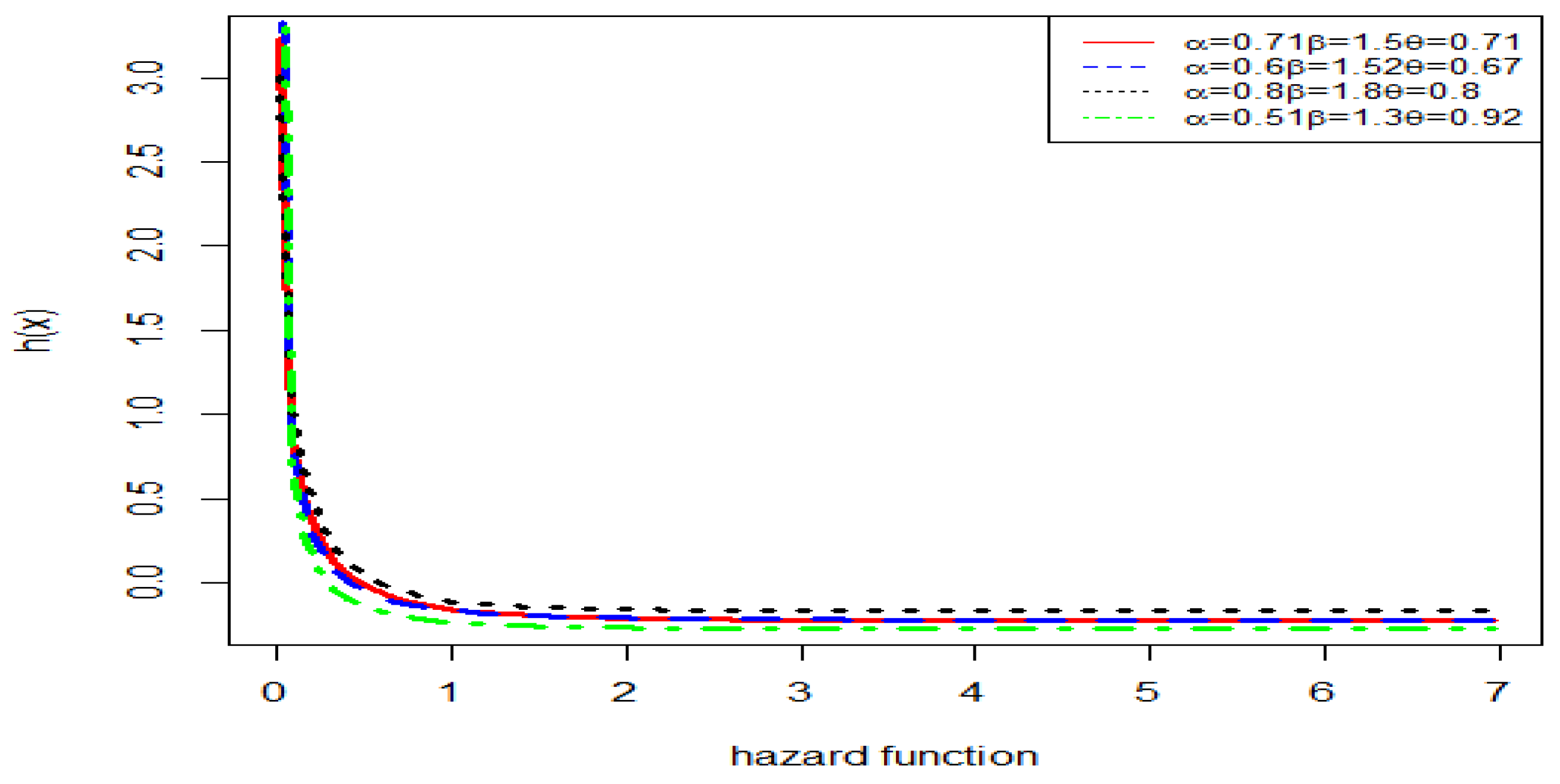

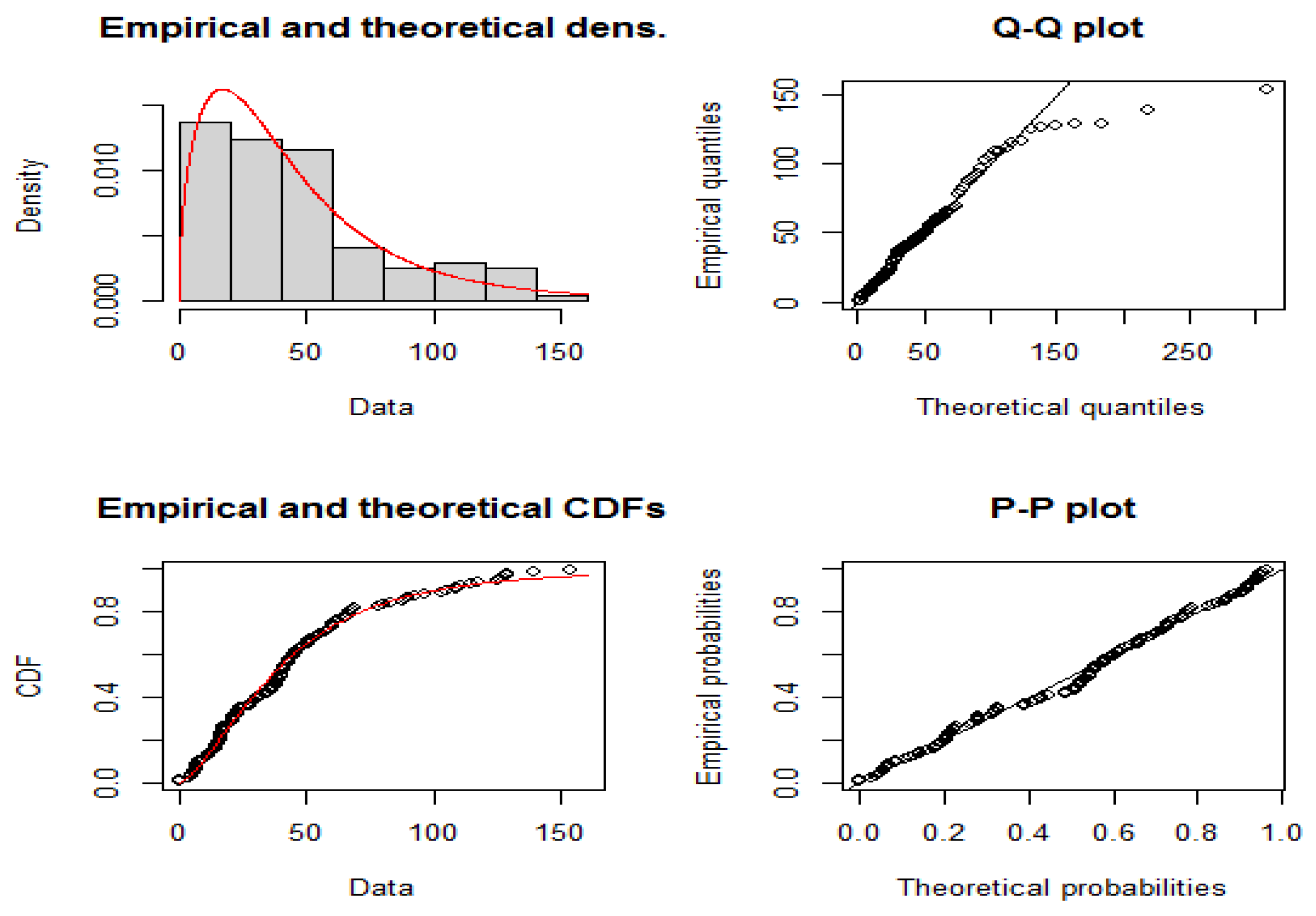

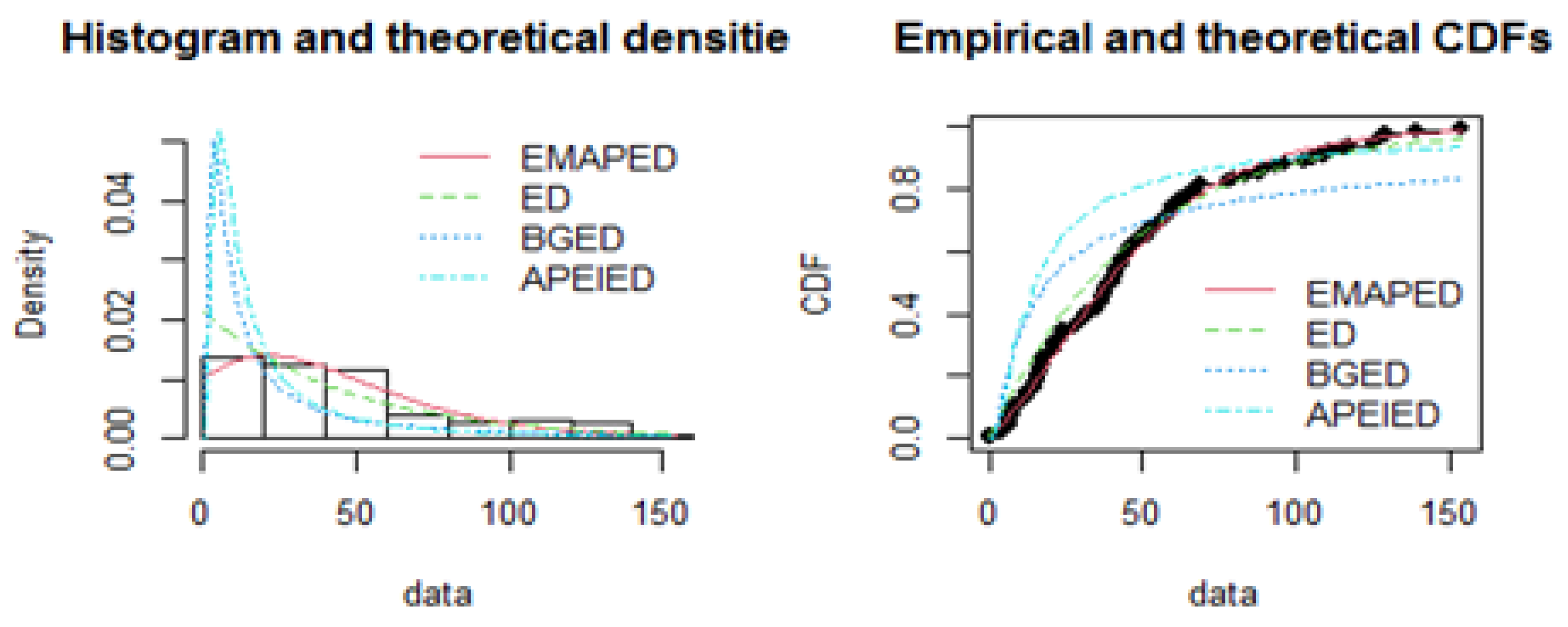

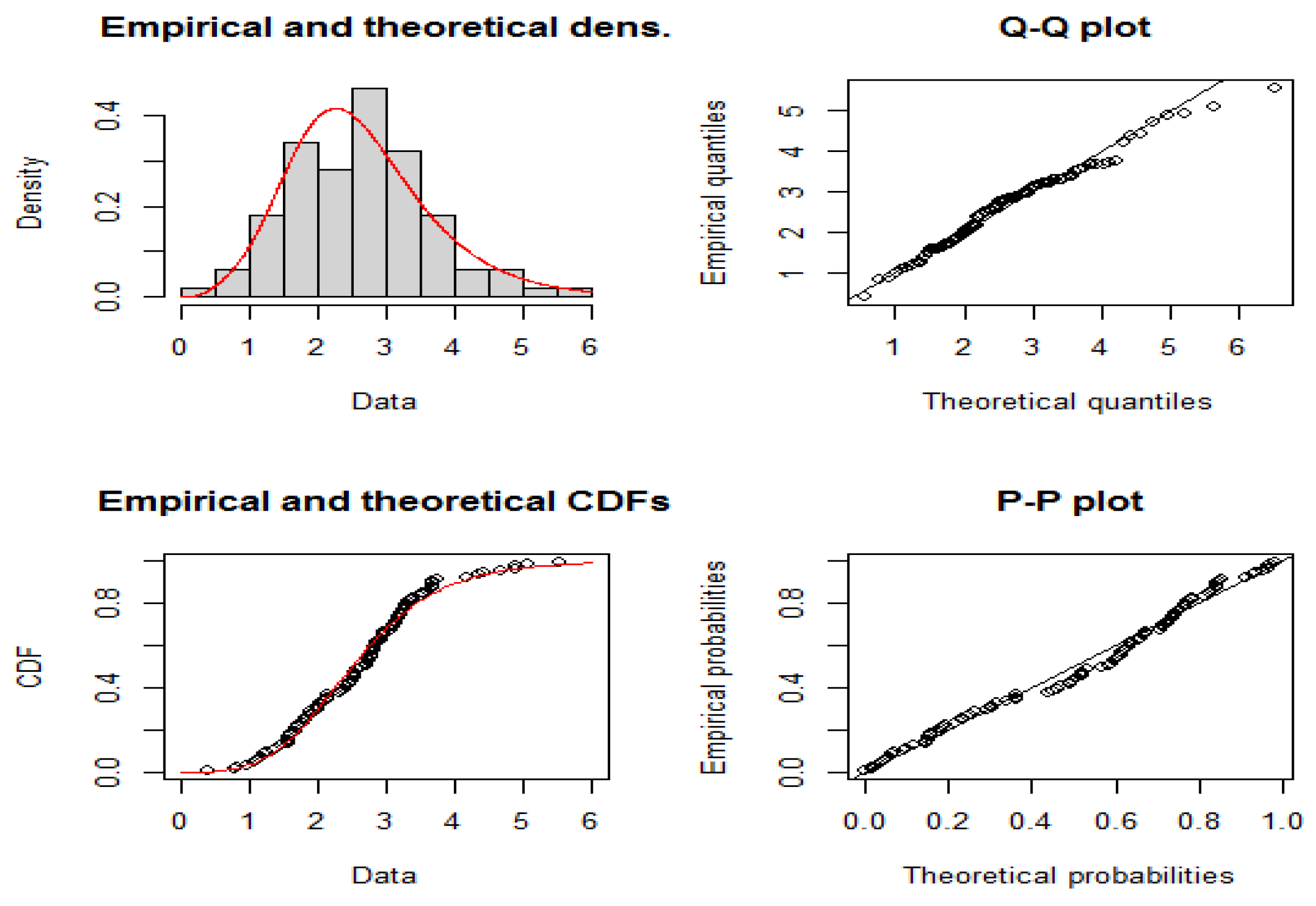

4. Real Data Application

- Exponential distribution (ED)

- BGE distribution

- APEIE distribution

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBE | Exponentiated Beta Exponential Distribution |

| ED | Exponential Distribution |

| BGED | Beta Generalized Exponential Distribution |

| APEIED | Alpha Power Exponentiated Inverse Exponential Distribution |

References

- Dey S, Sharma VK, Mesfioui M. A new extension of Weibull distribution with application to lifetime data.Annals of Data Science. 2017; 4(1):31–61. [CrossRef]

- Mudholkar G S, Srivastava DK. Exponentiated Weibull family for analyzing bathtub failure-rate data.IEEE transactions on reliability. 1993; 42(2):299–302. [CrossRef]

- Marshall AW, Olkin I. A new method for adding a parameter to a family of distributions with application to the exponential and Weibull families. Biometrika. 1997; 84(3):641–52. [CrossRef]

- Eugene N, Lee C, Famoye F. Beta-normal distribution and its applications. Communications in Statistics-Theory and methods. 2002; 31(4):497–512. [CrossRef]

- Jones M. C. Kumaraswamy’s distribution: A beta-type distribution with some tractability advantages.Statistical Methodology. 2009; 6(1):70–81. [CrossRef]

- Alzaatreh A, Lee C, Famoye F. A new method for generating families of continuous distributions.Metron. 2013; 71(1):63–79. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Famoye F, Alzaatreh AY. Methods for generating families of univariate continuous distributionsin the recent decades. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics. 2013; 5(3):219–38. [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi A, Kundu D. A new method for generating distributions with an application to exponential distribution.Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods. 2017; 46(13):6543–57. [CrossRef]

- Nassar M, Alzaatreh A, Mead M, Abo-Kasem O. Alpha power Weibull distribution: Properties and applications.Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods. 2017 18; 46(20):10236–52. [CrossRef]

- Dey S, Alzaatreh A, Zhang C, Kumar D. A new extension of generalized exponential distribution with application to Ozone data. Ozone: Science & Engineering. 2017; 39(4):273–85. [CrossRef]

- Dey S, Ghosh I, Kumar D. Alpha-Power Transformed Lindley Distribution: Properties and Associated Inference with Application to Earthquake Data. Annals of Data Science. 2018:1–28. [CrossRef]

- Hassan AS, Mohamd RE, Elgarhy M, Fayomi A. Alpha power transformed extended exponential distribution: properties and applications. Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Applications. 2018; 12(4), 62–67. [CrossRef]

- Dey S, Nassar M, Kumar D. Alpha power transformed inverse Lindley distribution: A distribution with an upside-down bathtub-shaped hazard function. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics.2019; 348:130–45. [CrossRef]

- Lee S, Kim J H. Exponentiated generalized Pareto distribution: Properties and applications towards extreme value theory. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods. 2018; 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Brazauskas V, Serfling R. Favorable estimators for fitting Pareto models: A study using goodness-of-fit measures with actual data. ASTIN Bulletin: The Journal of the IAA. 2003; 33(2):365–81. [CrossRef]

- Farshchian M, Posner F L. The Pareto distribution for low grazing angle and high resolution X-band sea clutter. Naval Research Lab Washington DC; 2010. [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz M, Altun E, Yousof H, Afify A, Nadarajah S. The Burr X Pareto Distribution: Properties, Applications and VaR Estimation. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2018; 11(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Philbrick S W. A practical guide to the single parameter Pareto distribution. PCAS LXXII. 1985; 44–85.

- Levy M, Levy H. Investment talent and the Pareto wealth distribution: Theoretical and experimentalanalysis. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2003; 85(3):709–25. [CrossRef]

- Castillo E, Hadi AS. Fitting the generalized Pareto distribution to data. Journal of the American StatisticalAssociation. 1997; 92(440):1609–20. [CrossRef]

- Johnson N. L., and Kotz S., Balakrishnan N. Continuous Univariate Distributions-I. New York: JohnWiley; 1994.

- Pickands J III. Statistical inference using extreme order statistics. The Annals of Statistics. 1975;3(1):119–31.

- Gupta RC, Gupta PL, Gupta RD. Modeling failure time data by Lehman alternatives. Communicationsin Statistics-Theory and methods. 1998; 27(4):887–904. [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah S. Exponentiated Pareto distributions. Statistics. 2005; 39(3):255–60. [CrossRef]

- Akinsete A, Famoye F, Lee C. The beta-Pareto distribution. Statistics. 2008; 42(6):547–63. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi E. The beta generalized Pareto distribution with application to lifetime data. Mathematicsand computers in Simulation. 2011; 81(11):2414–30. [CrossRef]

- Alzaatreh A, Famoye F, Lee C. Weibull-Pareto distribution and its applications. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods. 2013; 42(9):1673–91. [CrossRef]

- Tahir M H, Cordeiro GM, Alzaatreh A, Mansoor M, Zubair M. A new Weibull–Pareto distribution: propertiesand applications. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation. 2016; 45(10):3548–67. [CrossRef]

- Pereira MB, Silva RB, Zea LM, Cordeiro GM. The kumaraswamy Pareto distribution. arXiv preprintarXiv:1204.1389. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah S, Eljabri S. The kumaraswamy gp distribution. Journal of Data Science. 2013; 11(4):739–66.

- Afify AZ, Yousof HM, Hamedani GG, Aryal G. The exponentiated Weibull-Pareto distribution with application.J. Stat. Theory Appl. 2016; 15:328–46. [CrossRef]

- Shaked M, Shanthikumar Jeyaveerasingam G. Stochastic Orders. Series: Springer Series in Statistics.New York: Springer; 2007.

- Hogg R. and Klugman S.A. Loss Distributions. New York: Wiley; 1984.

- Mead ME, Afify AZ, Hamedani GG, Ghosh I. The beta exponential Fre’chet distribution with applications.Austrian Journal of Statistics. 2017; 46(1):41–63.

- Johnson N. L., and Kotz S. Continuous Univariate Distributions-2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1970.

- Guo L, Gui W. Bayesian and Classical Estimation of the Inverse Pareto Distribution and Its Application to Strength-Stress Models. American Journal of Mathematical and Management Sciences. 2018; 37(1):80–92. [CrossRef]

- Brodin E, Rootze’n H. Univariate and bivariate GPD methods for predicting extreme wind storm losses.Insurance: Mathematics and Economics. 2009; 44(3):345–56. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.W.A., Cordeiro, G.M., Marinho, P.R.D., Dias, C.R.B. and Hamedani, G.G.(2013). The Zografos-Balakrishnan log-logistic distribution: Properties andapplications. Journal of Statistical Theory and Applications, 12, 225-244. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | N | MSE0 | MSE1 | MSE2 | BIAS0 | BIAS1 | BIAS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

60 | 0.25942 | 9.90072 | 7.8970 | 0.03388 | -0.83549 | 1.49541 |

| 150 | 0.08497 | 4.96927 | 3.9120 | 0.03255 | -0.41015 | 0.75848 | |

| 230 | 0.05041 | 3.70697 | 2.9987 | 0.00723 | -0.08396 | 0.50724 | |

|

|

40 | 0.22716 | 15.6961 | 7.0710 | 0.11502 | -0.66054 | 1.48416 |

| 130 | 0.08807 | 8.56222 | 4.6855 | 0.02997 | -0.05309 | 0.81565 | |

| 210 | 0.03797 | 3.81034 | 2.4992 | -0.02088 | -0.04777 | 0.44718 | |

|

|

120 | 0.07721 | 5.25017 | 4.3567 | 0.10494 | -0.79556 | 1.18455 |

| 220 | 0.03589 | 2.01053 | 2.0358 | 0.03613 | -0.07332 | 0.38506 | |

| 380 | 0.03043 | 2.32888 | 2.0092 | -0.0011 | -0.02987 | 0.37981 |

| Distribution | MLE | AIC | CAIC | BIC | HQIC | P-value | ||

| EBE | 1.454518 | 0.205884 | 0.025538 | 1166.945 | 1167.15 | 1175.333 | 1170.352 | 0.3501 |

| ED | 0.021593 | 1172.256 | 1172.28 | 1175.051 | 1173.391 | 0.05971 | ||

| BGED | 0.560161 | 6.3926366 | 1332.248 | 1332.35 | 1337.84 | 1334.519 | 1.141e-08 | |

| APEIED | 3.587380 | 24.433696 | 1.533854 | 1264.878 | 1265.083 | 1273.266 | 1268.285 | 2.2e-16 |

| Distribution | MLE | AIC | CAIC | BIC | HQIC | P-value | ||

| EBE | 4.724535 | -3.409094 | 1.244129 | 291.6781 | 291.9281 | 299.4936 | 294.8412 | 0.4091 |

| ED | 0.3814557 | 394.7417 | 394.7825 | 397.3469 | 395.7961 | 2.369e-09 | ||

| BGED | 9.060031 | 6.196268 | 306.4821 | 306.6058 | 311.6924 | 308.5908 | 0.06698 | |

| APEIED | 1.057584 | 2.023400 | 402.7912 | 402.9149 | 408.0015 | 404.8999 | 2.315e-11 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).