1. Introduction

For decades, surgeons and Infectious Diseases physicians have added rifampin/rifampicin (RIFA) to the postoperative antibiotic treatment of staphylococcal implant infections if the material is retained or subjected to a one-stage exchange [1]. In these infections, the biofilm represents a major therapeutic problem. Antibiotics penetrate only poorly into bone, let alone into the biofilm of non-irrigated foreign bodies [2]. Most experts consider RIFA the best antimicrobial agent that could penetrate biofilms and kill the embedded bacteria. Therefore, RIFA is a very precious molecule, against which the staphylococci must never develop resistance [1,3]. RIFA-resistance can occur very rapidly (within a few days) in cases of RIFA monotherapy [4,5] or a high inoculum (i.e., bacteremia, lack of adequate debridement, or entry of new staphylococci via open wounds). Therefore, most experts advocate combining RIFA with another agent throughout the entire therapeutic course [3] which contradicts the premise of awaiting wound closure.

Hence, in daily clinical practice, the combined therapy with RIFA does not occur on Day 0, for many reasons such as strong nausea in the surgical aftermath and the presence of orthopedic wounds that are still discharging. The clinicians hesitate between a theoretical risk of future RIFA resistance, and the deprivation of the best regimen in the critical early phase of biofilm formation [6]. We believe that this is a very rare risk in clinical practice, which motivated us to investigate this widespread practice of awaiting wound closure. In contrast, we do not investigate the efficacy of combining RIFA with other agents for staphylococcal implant infections, for which a much broader literature is available [1].

2. Results

2.1. Staphylococcal Implant Infections

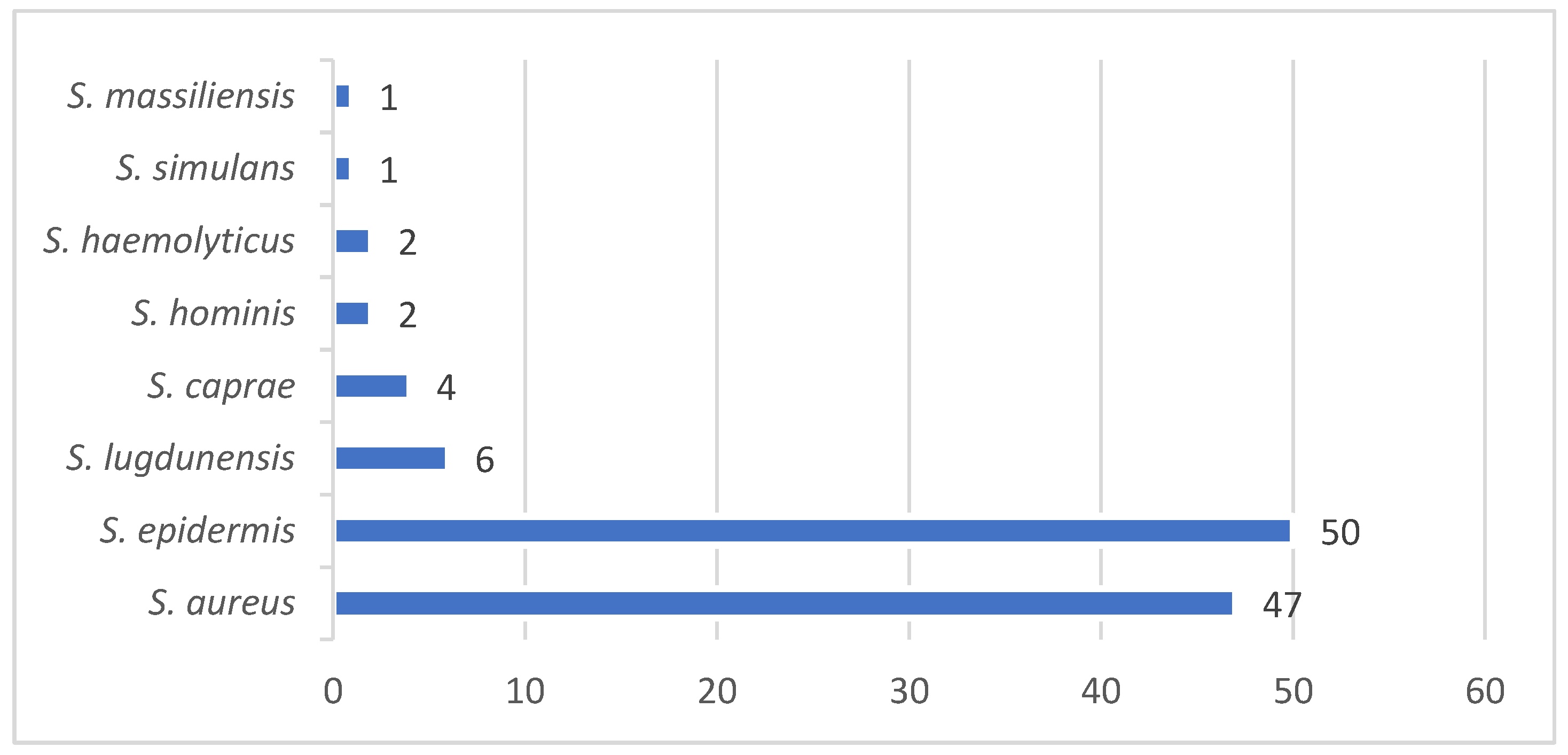

Among 242 independent infection episodes due to various staphylococci and orthopedic implants, 103 fulfilled our study criteria (43 % female patients). The infection sites included the knee (n=31; 30%), hip (24; 22%), spine (33; 32%), foot (7; 7%), shoulder (5; 5%), and hand (1; 1%). Implant types comprised total joint arthroplasties (n=54; 52%), plates (11; 11%), screws (2%), spondylodeses and cages (33; 32%), cerclages (1%), and pins (1%). We noted 26 distinct staphylococcal constellations, with

Staphylococcus aureus predominating in 47 cases (46%), including three healthcare-associated and one community-acquired MRSA (methicillin-resistant

S. aureus). The group of coagulase-negative staphylococci comprised 56 cases (54%;

Figure 1). In half of the episodes (49%), the pathogens were methicillin-resistant and in 19 (18%) polymicrobial. The median active follow-up (surgical control visits) lasted 1.9 years (interquartile range (IQR), 1.0-2.7 y) and the median passive follow-up 2.9 years (IQR, 2.3-3.9 y). We closed the database on 10 July 2025.

2.2. Surgical and Medical Therapy with Combined RIFA Use

The median number of surgical debridements per episode was 1 (IQR, 1-2 surgeries). We used 22 different initial empirical systemic antibiotic regimens, of which the three most frequent agents were co-amoxiclav (n=49), vancomycin (n=21) and cefazolin (n=5). We did not use local antibiotic-loaded cements or intraosseous local antibiotics for retained implants. The total median duration of the postoperative antibiotic treatment was 84 days (IQR, 42-84 d). The total median duration of oral RIFA use was 70 days (IQR, 39-80 d), resulting in a median RIFA-to-beta-lactam ratio of 0.92 for the antibiotic course (IQR, ratio 0.82-0.96). The median delay until the postoperative RIFA introduction was five days (IQR, 3-8 d). We prescribed RIFA in a median daily dose of 900 mg (450 mg bid), never rifampin or rifabutin. Overall, 19 patients (19/103; 18%) experienced a significant adverse event (AE) attributed by clinicians to RIFA use: appetite loss (n=8; 8%), emesis (5%), protracted nausea (3%), oral mycosis (2%), and probable skin rash (2%). The occurrence of RIFA-related AEs significantly reduced the duration of the RIFA part of therapy (median 73 days without vs. 41 days with adverse events; Wilcoxon-ranksum-test; p=0.01). Of note, the dose RIFA did not increase the risk for AE (median 900 mg vs. 900 mg; p=0.55).

2.3. Outcomes

We observed 27 episodes “Clinical Failures” after the first therapy: new infection (n=13), recurrent infection (7), persistent infection (3), invalidating back pain (2), material failure (1), bone instability (1), and hematoma requiring re-intervention (n=1). During and after treatment, the surgeons performed a revision in 42 cases (40%) for additional reasons other than Clinical Failures: implant removal for mechanical reasons (n=3), luxation of a temporary spacer (1), scar revisions (3), arthrofibrosis (1), second looks (15), and mechanical correction (n=4). The case-mix was broad.

Table 1 reveals the key results of our adjustment with Cox regression; with an emphasis on RIFA-related variables.

The incidence of “Microbiological Recurrences” with the same Staphylococcus was 9.7% (10/103 episodes). A group comparison or a multivariate analysis was not possible due to the small numbers (n=10) of this variable. During the long study follow-up, six patients died from causes unrelated to orthopedic infections or their RIFA use. The median length of hospital stay in our acute surgical wards was 12 days (IQR, 8-17 d).

2.4. Rifampicin Resistance

The median delay between the first debridement and the “last Staphylococcus” (sampled for any indication) was 322 days (IQR, 42-425 d). The staphylococcal species between the index pathogen and the “last Staphylococcus” differed in seven cases (7%). In sixteen episodes (16%), the initial pathogen and the later control belonged to the same species but were different in their susceptibility testing according to at least three antibiotic classes. Among the 103 implant infections, two therapies were started with a RIFA-resistant strain. Both lost their resistance, replacing the initial stain with a RIFA-susceptible strain.

In only one case of a periprosthetic knee joint infection due to a methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis (1/103; 1%), the same initial RIFA-susceptible S. epidermidis became RIFA-resistant “after” 68 days of RIFA treatment. For this case, the initial delay of RIFA introduction was 8 days, which was longer, but not significantly different from the other 102 cases (median 5 days). For this case, the RIFA duration lasted 34 days (compared to a median of 84 days among the controls; p=0.19) and its daily oral dose was 450 mg bid (p=1.00). The accompanying agent for 42 days of total therapy was co-amoxiclav.

2.5. Literature Review

The first and the last authors performed a narrative literature review focusing on timing of RIFA intiation. We resume its key findings in the Supplemantary Appendix 1.

3. Discussion

According to our experience, the incidence of a (future) RIFA-resistant strain after long-term RIFA-combined antibiotic treatment was low (1%), regardless of the delay in RIFA introduction, the daily dose, and the total duration of its administration. Our findings are in line with our clinical experience, the sparse literature regarding RIFA resistance [7] and clinical failure rates of staphylococcal orthopedic infections [8,9,10]. Usually, RIFA-resistance is related to a spontaneous chromosomal mutation in the rpoB gene [11,12]. RIFA-resistance is more likely linked to the acquisition of specific strains with an individual genetic background, staphylococcal cassettes, and clonality [13,14], that replace the former ones. Indeed, we saw two infected patients starting with a RIFA-resistance strain that later switched to susceptible strains; and only one genuine resistance development.

The epidemiology of RIFA resistance among staphylococci is complex and heterogenous across geography and time [11]. In Italy and Southern Germany, RIFA-resistance has been increasing up to 16% among multidrug-resistant MRSA isolates, compared to the rest of Europe (5.7%) [14,15], but not ubiquitously. To cite a positive example, Grünwald et al. investigated 212 patients with prosthetic joint infections and RIFA treatment. Only 0.9% after the first stage and 1.4% at follow-up developed resistance [6]. They concluded that therefore, RIFA administration could be started on the second postoperative day when sufficient concentrations of the accompanying antibiotics can be expected [6]. RIFA-resistance might disappear over time [7], for example when facing competition. In animals infected with equal numbers of RIFA-resistant and RIFA-susceptible bacteria, only RIFA-susceptible strains were recovered after four weeks, indicating the out-competition of RIFA-resistant by RIFA-susceptible isolates [13]. Moreover, selected RIFA resistance may not persist in initially RIFA-susceptible infections following the discontinuation of RIFA. They simply may not have competitive fitness [7,13]. Unsurprisingly, even if RIFA-resistance occurs, a RIFA-based combination therapy may remain active in implant-infections following the initial selection of RIFA-resistance after prior RIFA monotherapy [7].

RIFA combinations are established in modern day infectiology for staphylococcal biofilm infections. Undoubtfully, in animal cage models, everyone is impressed by the rapid curves of the RIFA combinations, but clinicians cannot reproduce the in vitro results [1] and are rather marked by the high prevalence of RIFA-related AEs [16,17]. The landmark study of Prof. Zimmerli in the early 1990’ties showed that a combination of ciprofloxacin and RIFA was superior to ciprofloxacin alone for the treatment of staphylococcal implant-related biofilms [18]. This prospective-randomized trial was halted only after the inclusion of 33 episodes because of a significant advantage of the combination. The success study could never be repeated, partly because today, no ID physician would use ciprofloxacin in monotherapy (an anti-Gram-negative agent) for complicated staphylococcal infections, even if the oral bioavailability and bone penetration of oral ciprofloxacin are good [19]. Subsequent trials regularly failed to show this initial impressive benefit with combining RIFA-ciprofloxacin [20] or combining with other antibiotic agents [20]. The researchers mostly detect a superiority of RIFA combinations in selected groups such as MRSA infections [10,21], or in selected surgical approaches such as the implant retention procedures [22,23,24]. Kruse et al. recently reached the opposite conclusion in their Canadian meta-analysis of clinical studies [25]. They found that the protective effect of RIFA was maintained in studies which included exchange arthroplasty, but not in studies using an implant retention strategy [25]. Several meta-analyses confirmed that RIFA combinations revealed higher cure rates than monotherapies in cohort studies, but not in randomized-controlled trials [22,23,26,27]. The certainty and quality of evidence were low [22,23]. The future will be marked by discussion about which patients benefit from RIFA combinations [3].

The optimal timing of RIFA remains an unresolved controversy with sparse literature. In a very large multicenter study in the Rhône-Alpes region of France, involving six centers with infected hip and knee total joint arthroplasties, the authors failed to observe a significant difference between success and failure in overall RIFA use, dose and, importantly, the delay of RIFA introduction [24]. Only the duration of RIFA therapy was associated with failure. Kaplan-Meier estimates of failure were higher in patients receiving less than 14 days of RIFA in comparison with those receiving more than 14 days [24]. We are aware of only one paper advocating that delaying RIFA would be better: albeit in a particular study setting. Darwich et al. retrospectively [15] compared the risk of RIFA-resistance between patients with prosthetic joint infections treated with regimens involving either immediate or delayed RIFA administration. The first group received additional RIFA only after pathogen detection, the second group directly postoperatively. RIFA resistance increased significantly from 12% in the first group to 19% in the second, whereas the treatment failure rate remained the same (16% versus 16%; respectively) [15]. Of note, in their setting, the patients received RIFA even before knowing if it was susceptible or not, and starting from a 16% general RIFA prevalence, which is very different from Switzerland. In recent times, many ID physicians and orthopedic surgeons are prone to abandoning this artificial delay and slowly change daily practices [6]. One of the larger prospective-randomized trials, the Roadmap Trial

™, investigating (staphylococcal) prosthetic joint infections, will not delay RIFA therapy

https://www.roadmaptrial.com/. The most recent US recommendations on cardiovascular implantable device infections do not even mention delaying RIFA during bacteremia [28]. The latest French recommendations recommend “when surgical treatment is needed, RIFA should be introduced only after the surgical reduction of the bacterial inoculum”. No words about an ideal timing or the presence of discharging wounds [12], for which literature is equally very sparse. Of note and interestingly, basic researchers have no difficulties when testing local RIFA powder,

nota bene specifically for its anti-biofilm properties, for traumatic contaminated wounds [29]. These research groups screen for RIFA resistance and don’t find any [29]. Likewise, topical RIFA as monotherapy is equally used for open neural tube defects to prevent ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection without reported resistance problems [30]. Similarly, clinicians may use RIFA, with or without antibiotic combinations, for the eradication of

S. aureus skin carriage from healthy and sick populations [31]. In an extensive microbiological review of RIFA use in human medicine [3], there is no mention of delaying the prescription because of a high inoculum or ulcerations for orthopedic surgery, nor for ulcerative mycobacteria [32], or regarding therapeutic recommendations for tuberculosis.

In terms of RIFA dosing in infected arthroplasties, two French trials showed that lower doses are as efficient and safe as the recommended high-dose regimen in France that exceed the internationally accepted 600 mg to 900 mg per day [8,24]. We cannot agree more.

Our study has limitations: Firstly, it is a retrospective single-center study, which limits the generalizability of the results on a global scale. Even in Switzerland, there are many centers that do not withhold RIFA beyond 1 to 2 days following surgical debridement. Secondly, we might not be aware of control samples outside of our hospital, notably from superficial swabs in the outpatient setting or in the General Practitioner’s office. Similarly, we ignore whether the patients actually took their RIFA medication as prescribed, especially in the outpatient setting. RIFA is the antibiotic with the most frequent AE in orthopedic infections (e.g., nausea, emesis, red urine coloration and/or hepatitis) and regularly interacts with other essential medications [3], including with antibiotic agents [12,27,33] and nutritional interventions. The incidence of important AEs (with consequent halting of RIFA therapy or by modifying it) largely varies in the literature, ranging from 10% [16] and 13% [26] to 18% [34], 21% [25], 24% [8] and probably up to 71% when we include light events [17]. Unsurprisingly, and according to a survey from Germany, the proportion of patients who discontinued RIFA (without replacement) due to attributed adverse events was 19% [35]. In evaluations conducted in France and Switzerland, a full treatment course with RIFA could only be achieved in 75%-82% of cases [8,9]. In this optic, biosensors and analytical methods to optimize the individual RIFA dose are gaining momentum [38]. Thirdly, our resistance was based on standard semi-automatized susceptibility testing; and not on clinical grounds, the detection of heterogeneity in a research laboratory or the routine determination of minimal inhibitory concentrations [10]. Lastly, we computed the delay of RIFA introduction with the number of objective days that may serve as an arguable surrogate for wound problems, which, in turn, can only be assessed in prospective trials.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Setting and Study Criteria

The Balgrist University Hospital is a tertiary, referral orthopedic center in Zurich, Switzerland. It maintains a prospective cohort of all documented infections and performs multiple retrospective and prospective trials of orthopedic infections since July 2018. This is a study of orthopedic infections with an emphasis on RIFA-related clinical and microbiological variables. Additional inclusion criteria are documentation of antibiotic treatment and AE, and an active follow-up at least one year. Exclusion criteria are mixed infections with a predominance of non-staphylococcal pathogens, a lack of detailed information and a lack of a Balgrist-specific signed General Consent.

4.2. Study Definitions and Microbiological Cultures

We diagnosed a bacterial infection on clinical, radiological and microbiological criteria according to international guidance and basically consisting of the presence of local inflammation/pus that is microbiologically confirmed by the presence of the same staphylococcus in at least two deep intraoperative tissue samples; and approved by our infection specialists. We defined “Clinical Failures” as the need for surgical revision, or any new therapy, in the former infection site for any reason, including for infection relapses. A relapse with the same pathogen (according to its antibiotic susceptibility testing) as in the index infection was labeled as a “Microbiological Recurrence”. The “Institute for Medical Microbiology” at the University of Zurich performed all bacteriological examinations. We considered two staphylococci as identical if they belonged to the same species and revealed the same susceptibility testing results (with slight differences). Conversely, we arbitrarily taxed two identical species as different if they differed in at least three antibiotic classes according to the routine susceptibility testing. We renounced on typisation and on Therapeutic Drug Monitoring for antimicrobials, including for RIFA [39].

4.3. Statistical Analyses Plan

A prospective-randomized trial cannot answer our study question and would not be ethical. Embedded in a retrospective case-control study design, we therefore linked RIFA-related antibiotic variables to the occurrence of RIFA-resistant strains and to the general therapeutic success of infection. As we expect very few new RIFA-resistant strains and “Microbiological Recurrences”, the analyses are mainly descriptive. However, the case-mix is expected to be large, which we adjust performing a multivariate Cox regression analysis with the outcome “Clinical Failure”. For the Cox regression, the infection episodes are censored at the date of death, occurrence of therapeutic failures, or at the latest visit to our hospital. The number of variables in the final model is limited to the ratio of 1 variable to 5 to 8 outcome events [40], which also excludes a multivariate model for the potential outcomes of “Microbiological Recurrence” or RIFA-resistance due to paucity of events. Practically, we choose the following variables into the final model: delay of RIFA introduction, total duration of RIFA administration, and the daily RIFA doses. We computed “delay of RIFA” as a continuous and as categorized variables (≤3 days, 4-7 days, and >8 days). We use STATA™ software (Version 19; College Station, Texas, USA) and consider p-values ≤0.05 (two-tailed) as significant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: resumes our narrative literature review on our study topic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.U., V.D., D.A., and S.M.; methodology, I.U., S.M., V.D., M.M..; validation, I.U., T.H., and S.M..; formal analysis, V.D:, S.M., M.M., D.A., and I.U..; investigation, V.A., D.A., S.M., and M.M.; resources, I.U., and M.F.; data curation; V.D., D.A., and I.U., narrative literature review, V.D., and I.U.; writing—original draft preparation, V.D., and I.U.; writing—review and editing, V.D., T.H., and I.U.; visualization, I.U.; supervision, I.U., and M.F.; project administration, I.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Ethics Committee of Canton Zurich (BASEC 022-01377, approved on 26 August 2022), and supported by our Medical Direction (Wissenschaftsnummer W963).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. It corresponded to the General Consent of Balgrist University Hospital.

Data Availability Statement

We may provide anonymized key data upon reasonable scientific request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all colleagues of the Institute for Medical Microbiology (University of Zurich). We are indebted to the research assistants Ms. Stefani Dossi and Ms. Nathalie Kühne.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zimmerli, W.; Sendi, P. Role of Rifampin against Staphylococcal Biofilm Infections In Vitro, in Animal Models, and in Orthopedic-Device-Related Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçkay, I.; Pittet, D.; Vaudaux, P.; Sax, H.; Lew, D.; Waldvogel, F. Foreign body infections due toStaphylococcus epidermidis. Ann. Med. 2009, 41, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupaibool, J. The Role of Rifampin in Prosthetic Joint Infections: Efficacy, Challenges, and Clinical Evidence. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, G.L.; Johnston, J.L.; Vazquez, G.J.; Haywood, H.B. Efficacy of Antibiotic Combinations Including Rifampin Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1983, 5, S538–S542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M.E.; Khamas, A.B.; Østergaard, L.J.; Jørgensen, N.P.; Meyer, R.L. Combination therapy delays antimicrobial resistance after adaptive laboratory evolution of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0148324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grünwald, L.; Blersch, B.P.; Fink, B. Early Administration of Rifampicin Does Not Induce Increased Resistance in Septic Two-Stage Revision Knee and Hip Arthroplasty. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, C.L.; Schmidt-Malan, S.M.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Patel, R. Rifampin-Based Combination Therapy Is Active in Foreign-Body Osteomyelitis after Prior Rifampin Monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnelier, M.; Bouras, A.; Joseph, C.; El Samad, Y.; Brunschweiler, B.; Schmit, J.-L.; Mabille, C.; Lanoix, J.-P. Impact of rifampicin dose in bone and joint prosthetic device infections due to Staphylococcus spp: a retrospective single-center study in France. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, A.F.; Gaechter, A.; Ochsner, P.E.; Zimmerli, W. Antimicrobial Treatment of Orthopedic Implant-related Infections with Rifampin Combinations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1992, 14, 1251–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, T.; Uçkay, I.; Vaudaux, P.; François, P.; Schrenzel, J.; Harbarth, S.; Laurent, F.; Bernard, L.; Vandenesch, F.; Etienne, J.; et al. Risk factors for treatment failure in orthopedic device-related methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009, 29, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Eom, Y.; Kim, E.; Chang, E.; Bae, S.; Jung, J.; Kim, M.J.; Chong, Y.P.; Kim, S.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; et al. Molecular Characteristics and Prevalence of Rifampin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Patients with Bacteremia in South Korea. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiffier, G.; Albert, J.-D.; Arvieux, C.; Guggenbuhl, P. Optimizing combination rifampin therapy for staphylococcal osteoarticular infections. Jt. Bone Spine 2013, 80, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, C.L.; Tyner, H.L.; Schmidt-Malan, S.M.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Patel, R. Causes and Implications of the Disappearance of Rifampin Resistance in a Rat Model of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Foreign Body Osteomyelitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4481–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, D.; Mongelli, G.; Stefani, S.; Campanile, F. Burden of Rifampicin- and Methicillin-ResistantStaphylococcus aureusin Italy. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwich, A.; Dally, F.-J.; Bdeir, M.; Kehr, K.; Miethke, T.; Hetjens, S.; Gravius, S.; Assaf, E.; Mohs, E. Delayed Rifampin Administration in the Antibiotic Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infections Significantly Reduces the Emergence of Rifampin Resistance. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekaj, J.; Dinh, A.; Moldovan, A.; Vaudaux, P.; Gras, G.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Lew, D.; Bernard, L.; Uçkay, I. Efficacy of a combined oral clindamycin–rifampicin regimen for therapy of staphylococcal osteoarticular infections. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 43, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinecke, P.; Morovic, P.; Niemann, M.; Renz, N.; Perka, C.; Trampuz, A.; Meller, S. Adverse Events Associated with Prolonged Antibiotic Therapy for Periprosthetic Joint Infections—A Prospective Study with a Special Focus on Rifampin. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerli, W.; Widmer, A.F.; Blatter, M.; Frei, R.; Ochsner, P.E. Role of Rifampin for Treatment of Orthopedic Implant–Related Staphylococcal Infections A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 1998, 279, 1537–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landersdorfer, C.B.; Kinzig, M.; Höhl, R.; Kempf, P.; Nation, R.L.; Sörgel, F. Physiologically Based Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling Approach for Ciprofloxacin in Bone of Patients Undergoing Orthopedic Surgery. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 3, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlroth, J.; Kuo, M.; Tan, J.; Bayer, A.S.; Miller, L.G. Adjunctive Use of Rifampin for the Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Infections: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora-Tamayo, J.; Murillo, O.; Iribarren, J.A.; Soriano, A.; Sánchez-Somolinos, M.; Baraia-Etxaburu, J.M.; Rico, A.; Palomino, J.; Rodríguez-Pardo, D.; Horcajada, J.P.; et al. A Large Multicenter Study of Methicillin–Susceptible and Methicillin–Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Prosthetic Joint Infections Managed With Implant Retention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 56, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, N.; Matsushita, K.; Kamono, E.; Matsumoto, H.; Saka, N.; Uchiyama, K.; Suzuki, K.; Akiyama, Y.; Onuma, H.; Yamada, K. Effectiveness of rifampicin combination therapy for orthopaedic implant-related infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, E.; Bramer, W.; Anas, A.A. Clinical outcomes of rifampicin combination therapy in implant-associated infections due to staphylococci and streptococci: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 63, 107015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, A.; Kreitmann, L.; Triffaut-Fillit, C.; Valour, F.; Mabrut, E.; Forestier, E.; Lesens, O.; Cazorla, C.; Descamps, S.; Boyer, B.; et al. Duration of rifampin therapy is a key determinant of improved outcomes in early-onset acute prosthetic joint infection due to Staphylococcus treated with a debridement, antibiotics and implant retention (DAIR): a retrospective multicenter study in France. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2020, 5, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, C.C.; Ekhtiari, S.; Oral, I.; Selznick, A.; Mundi, R.; Chaudhry, H.; Pincus, D.; Wolfstadt, J.; Kandel, C.E. The Use of Rifampin in Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Comparative Studies. J. Arthroplast. 2022, 37, 1650–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, Ø.E.; Borgen, P.; Bragnes, B.; Figved, W.; Grøgaard, B.; Rydinge, J.; Sandberg, L.; Snorrason, F.; Wangen, H.; Witsøe, E.; et al. Rifampin combination therapy in staphylococcal prosthetic joint infections: a randomized controlled trial. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkin, R.; Iglesias-Ussel, M.D.; Keedy, K.; MacLauchlin, C.; Mould, D.R.; Berkowitz, R.; Kreuzer, S.; Darouiche, R.; Oldach, D.; Fernandes, P. A Randomized Study Evaluating Oral Fusidic Acid (CEM-102) in Combination With Oral Rifampin Compared With Standard-of-Care Antibiotics for Treatment of Prosthetic Joint Infections: A Newly Identified Drug–Drug Interaction. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 1599–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddour, L.M. ; Esquer Garrigos, Z-; Rizwan Sohail, M. ; Havers-Borgersen, E.; Krahn, A.D.; Chu, V.H.; Radke, C.S.; Avari-Silva, J.; El-Chami, M.F.; Miro, J.M.; DeSimone, D.C. Update on Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infections and Their Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association: Endorsed by the International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases. Circulation. 2024, 149, 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Shiels, S.M.; Tennent, D.J.; Wenke, J.C. Topical rifampin powder for orthopedic trauma part I: Rifampin powder reduces recalcitrant infection in a delayed treatment musculoskeletal trauma model. J. Orthop. Res. 2018, 36, 3136–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deger, I.; Başaranoğlu, M.; Demir, N.; Aycan, A.; Tuncer, O. Efficiency of topical rifampin on infection in open neural tube defects: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021, 131, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Bliziotis, I.A.; Fragoulis, K.N. Oral rifampin for eradication of Staphylococcus aureus carriage from healthy and sick populations: A systematic review of the evidence from comparative trials. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2007, 35, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O Phillips, R.; Robert, J.; Abass, K.M.; Thompson, W.; Sarfo, F.S.; Wilson, T.; Sarpong, G.; Gateau, T.; Chauty, A.; Omollo, R.; et al. Rifampicin and clarithromycin (extended release) versus rifampicin and streptomycin for limited Buruli ulcer lesions: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzoni, C.; Uçkay, I.; Belaieff, W.; Breilh, D.; Suvà, D.; Huggler, E.; Lew, D.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Bernard, L. In vivo interactions of continuous flucloxacillin infusion and high-dose oral rifampicin in the serum of 15 patients with bone and soft tissue infections due to Staphylococcus aureus - a methodological and pilot study. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, M.; Bernard, L.; Belaieff, W.; Gamulin, A.; Racloz, G.; Emonet, S.; Lew, D.; Hoffmeyer, P.; Uçkay, I. Epidemiology of adverse events and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea during long-term antibiotic therapy for osteoarticular infections. J. Infect. 2013, 67, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugelman, D.N.; Leal, J.B.; Shah, S.B.; Wrenn, R.; Mackowiak, A.P.; Ryan, S.P.; Jiranek, W.A.; Seyler, T.M.; Seidelman, J. How Often Is Rifampin Therapy Initiated and Completed in Patients With Periprosthetic Joint Infections? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2025, 483, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, O.; Ergen, P.; Ozturan, B.; Ozkan, K.; Arslan, F.; Vahaboglu, H. Rifampin-accompanied antibiotic regimens in the treatment of prosthetic joint infections: a frequentist and Bayesian meta-analysis of current evidence. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 40, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgärtner, T.; Bdeir, M.; Dally, F.-J.; Gravius, S.; El Hai, A.A.; Assaf, E.; Hetjens, S.; Miethke, T.; Darwich, A. Rifampin-resistant periprosthetic joint infections are associated with worse functional outcome in both acute and chronic infection types. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 110, 116447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; David, I.G.; Jinga, M.L.; Popa, D.E.; Buleandra, M.; Iorgulescu, E.E.; Ciobanu, A.M. State of the Art on Developments of (Bio)Sensors and Analytical Methods for Rifamycin Antibiotics Determination. Sensors 2023, 23, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiuma, M.; Colaneri, M.; Cattaneo, D.; Fusi, M.; Civati, A.; Galimberti, M.; Cossu, M.; Gervasoni, C.; Dolci, A.; Riva, A.; et al. Rifampicin drug monitoring in TB patients: new evidence for increased dosage? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2025, 29, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittinghoff, E.; McCulloch, C.E. Relaxing the Rule of Ten Events per Variable in Logistic and Cox Regression. Am. J. Epidemiology 2006, 165, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).