1. Introduction

About 20% of mild diabetic foot infections (DFIs) and up to 60% of severe cases present concomitant bone involvement [(1-2]. The outcome of osteomyelitis complicating a diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is usually worse than that of infected DFUs involving only skin and soft tissues (ST-DFIs) as Diabetes foot osteomyelitis (DFOs) are associated with higher (i) length of hospital stay, (ii) total duration of antibiotic therapy, (iii) time to wound healing after admission, (iv) total duration of the wound, and (v) risk of minor and major amputation of the foot [

3]. While suspicion of DFO is generally based on clinical and radiological elements, a diagnosis of certitude requires microbiological and histological criteria [

4]. Bone necrosis and difficulties in achieving high local concentrations of anti-infective agents in addition to peripheral artery disease and impaired leucocyte function generally associated with diabetes increase the risk of poor outcomes. Biofilm-related osteomyelitis represents another cause for the poor outcome of patients treated for a DFO. The presence of biofilm is one amongst many other barriers for antibiotics to achieve their antibacterial activity. Whether the presence of biofilms in infected bone tissues is a contraindication for the medical (i.e., with no bone resection) management of DFOs is a matter of debate. This raises the question of to what extent antibiotics with anti-biofilm activity add value to the medical management of DFOs.

The present work aims to summarize the current data on the structural particularities of DFO including biofilms and to discuss potential consequences regarding antibiotic use.

2. Microbiology

The microbiology of DFO is usually polymicrobial [5-8] and in almost all the reported series in Western countries,

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen cultured from bone samples while in warm climate countries, gram-negative bacilli dominate, especially

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

9]. Other gram-positive cocci frequently isolated from bone samples include

Staphylococcus epidermidis and other coagulase-negative staphylococci, beta-haemolytic streptococci, and diphtheroids. Among the Enterobacterales,

Escherichia coli,

Klebsiella pneumonia, and

Proteus spp. are the most common pathogens. Obligate anaerobes (e.g.

Finegoldia magna,

Clostridium spp., or

Bacteroides spp.) are generally less frequently cultured from bone samples but this depends on the method by which the bone fragments are taken and transported to the laboratory. A recent prospective study has reported that molecular techniques (16S rRNA sequencing) applied to the assessment of bone biopsies could identify more anaerobes and gram-positive bacilli compared to conventional techniques (86.9% vs. 23.1%, p = 0.001 and 78.3% vs. 3.8%, p < 0.001, respectively) [

10]. According to some recent studies using molecular techniques [

10,

11], the majority of DFOs are of polymicrobial origin with a high prevalence of strict anaerobes reinforcing the idea that the environment of bacteria involved in DFOs for most microorganisms and thus is likely to promote the organization of bacterial communities in biofilms [

12].

The poorer outcomes of DFOs compared to ST-DFIs seem to be related to the reduced activity of most antibiotics in the setting of a chronic bone infection. The main reasons are (i) the low diffusion of most antibiotics into the infected bone tissues especially if chronically infected and necrotic, (ii) the usual empirical antibiotic therapy of DFOs due to the difficulty encountered in organizing bone biopsy despite the low correlation between the culture results of bone versus non-bone samples reported in numerous studies, and (iii) the very specific environment of the bacteria involved in chronic osteomyelitis.

3. Histology

Bone and joint infections (BJIs) complicating a diabetic foot ulcer are the results of the extension to the infection that involves the skin and soft tissues overlying a bony prominence. There are almost no cases where the pathogens reach bone or joints from the bloodstream. While medullar bone or joint may be directly inoculated in the case of puncture wounds, the first osseous structure generally involved during DFO is the periosteum and cortical bone with secondary extension to the bone marrow (i.e., medullar bone). According to Hofmann et al. [

13], this kind of "centripetal" infection is defined as

osteitis rather than

osteomyelitis although the latter term is rarely used by authors.

Available data on the histological features of DFO are scarce. The usual histomorphological aspects reported in patients with DFO diagnosed on a clinical and imaging basis are varied including a typical aspect of osteomyelitis, bone necrosis, myelofibrosis, and normal bone as well [

14]. Of note, the histomorphology of unaffected foot bone appears mostly normal in diabetic patients with neuropathy and peripheral artery disease [

14]. According to Aragon-Sanchez et al., three different histomorphological abnormalities can be found in DFO: acute (destroyed bone, and infiltrations of polymorphonuclear granulocytes at cortical sites and inside the bone marrow usually associated with congestion or thrombosis of medullary or periosteal small vessels), chronic (destroyed bone and infiltrations of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and/or plasmatic cells at cortical sites and inside the bone marrow), and acute exacerbation of chronic osteomyelitis (a background of chronic osteomyelitis, upon which infiltration of polymorphonuclear granulocytes is present) [

15]. Areas of fibrosis and medullar oedema can be seen in all cases.

4. Biofilm

Beyond the identification of the causative pathogens from bone samples, it is also important to characterize their phenotypic state which significantly influences the antibacterial effect of most antibiotics. In the majority of the cases of DFO, the infection presents as chronic because of the frequent association with the loss of sensation allowing the indolent progression of the infectious process. It is common to oppose planktonic to sessile microorganisms, the former being responsible for acute infections and the latter for chronic infections. Indeed, there are not only two sorts of these microorganisms but rather a continuum in the metabolic status leading to numerous different types of bacterial cells. Planktonic exhibit a high metabolic and dividing activity exposing them to the activity of most antibiotics. These microorganisms may be involved in the rare cases of acute DFO generally due to highly virulent bacteria with a high tropism for bone tissues such as

S. aureus. On the opposite, sessile bacteria do not express many targets to the antibacterial activity of most antibiotics which is the cause of adaptive resistance and present as “small colony variants” (SCVs) with significant phenotypic alterations in culture [

16]. Some of these bacteria can enter a dormant state called

“persister cells” [

16]. These bacterial cells do not respond to the antibacterial activity of most antibiotic agents and are suspected to be at the origin of latent and recurrent infections. A bacterial phenotype switch to SCVs is facilitated in some specific conditions such as a biofilm environment, internalization in host cells including osteoblasts, and in the presence of antibiotics [

17].

The chronic process of BJIs facilitates the development of biofilms in bone tissues as reported in two independent studies. Baudoux et al. found that about two third of bone samples contained biofilm assessed by both crystal violet staining and electronic microscopy [

18]. Eight years later, Johani et al., using electronic microscopy, identified biofilm structures in 80% of the bone specimens [

11]. The authors found biofilm structures to be mainly localized at the surface of the periosteum and compact bone while were absent from compact bone interface. Malone et al. also demonstrated the presence of biofilms within bone samples taken at the bone margins in diabetic patients who underwent bone resections and amputation of the foot [

19]. Infected and proximal bone samples from 14 patients who had undergone bone resection or amputation for the treatment of a DFO were examined by electronic microscopy. In half of the cases, microorganisms including planktonic bacterial cells and aggregates embedded in biofilm structures were detected in both infected bone samples and the corresponding proximal bone margin [

19].

5. Anti-Biofilm Effect of Antibiotics

The term “biofilm” does not refer to a single entity as its structure may significantly differ according to the pathogens involved in its constitution and the level of its maturity. Older (mature) biofilms have more complex structures and are more resistant to antibiotic activity [

16]. The cut-off in the age of the biofilms beyond which no antibiotic effect can be expected is unknown but the clinical experience in prosthetic joint infections suggests a value of around 3-to-4 weeks [

20,

21]. It is uneasy to separate antibiotics with and without anti-biofilm activity. Some antibiotics, especially those that recently appeared on the market, have been shown to have an anti-biofilm activity but this was, for most of them, only based on

in vitro models using young biofilms [

22]. Of note, clinical efficacy in biofilm-related infections (e.g., prosthetic joint infections) has been established only for rifampicin and fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) [23-25].

Anti-biofilm antibiotics should (i) achieve concentrations above the minimal inhibitory concentration of the targeted pathogens, and (ii) exhibit maintained antimicrobial effects in the biofilm environment characterized by high protein concentrations, a low local oxygen pressure, a reduced pH, and high bacterial inoculum with an intense exchange between bacterial cells of nucleic material including antimicrobial resistance genes, (iii) maintain their activity against bacteria in the stationary phase with reduced metabolism, and (iv) act on adhering bacteria. A bactericidal effect is likely to be beneficial given the local immunosuppression within the biofilm due to the difficulty of some components of innate immunity to penetrate the biofilm structures [

16]. All these requirements may explain the lack of correlation between the bactericidal activity and the anti-biofilm activity in comparison with other types of infection where bacteria are in the exponential growth phase. This is the case for vancomycin, a bactericidal agent with activity against most staphylococcal strains, which has no effect on staphylococcal biofilms assessed in the animal tissue-cage model [

26]. Given the ability of some bacteria to invade and survive in a wild range of host cells intracellular concentration and activity may be of interest to combat biofilm-related bone and joint infections [

27]. The intra-osteoblastic bactericidal effect has been reported with fosfomycin, linezolid, tigecycline, oxacillin, rifampicin, ofloxacin, and clindamycin, while ceftaroline and teicoplanin have only a bacteriostatic effect and vancomycin and daptomycin no significant effect on the intracellular bacterial growth [

27]. Of note, Daptomycin, the unique representant of the cyclic lipopeptide family exhibits a maintained activity

in vitro against bacteria in the stationary phase but is inactive in the tissue-cage model [

26,

28]. Amongst the new long-acting lipoglycopeptides, a satisfactory

in vitro anti-biofilm effect has been reported with both dalbavancin and oritavancin but without demonstration of any clinical efficiency so far [

29]. These data emphasize the important value of animal models which should be done to confirm any

in vitro model suggesting an anti-biofilm effect.

6. Antibiotic Therapy

Current Data

While the role of biofilms in the pathogenicity of chronicisation of DFUs has been extensively studied, this is not the case for DFOs. Systemic or topical administrations of antibiotics have not shown efficacy for the management of non-healing DFUs [

12]. The reasons are unclear but the difficulties in obtaining local satisfactory antibiotic concentrations and the large number of bacteria organized in complex pathogroups probably act negatively in addition to the usual limitations of the antibiotic activity in biofilms [

12].

When examining the efficiency of antibiotic regimens for treating DFO, it is of utmost importance to consider whether the patients were treated with or without resection of the infected bone tissues. The main issue is for the medical and surgical management of DFOs, respectively, the persistence of chronically infected bone tissues and residual non-necrotic infected bone tissues. The task for the antibiotic treatment, therefore, depends on the type of infected bone tissues to treat. The presence of biofilm structures in the majority of chronically infected bones in patients diagnosed with DFO raises the question of the benefit of antibiotics with anti-biofilm activity in these settings. Recommendations on the choice of antibiotic regimens for the treatment of DFO are mostly based on expert opinions rather than evidence-based given the absence of randomized controlled studies that address this question [

30]. Some general rules used for the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis can, however, be applied to DFO including the use of antibiotics with high diffusion into bone (i.e. a bone/blood ratio >0.3) and good oral bioavailability (i.e. >90%) [

31]. Antibiotics that achieve the highest bone-to-serum concentration ratios (i.e. fluoroquinolones, sulfamides, cyclines, macrolides, rifampicin, fusidic acid, and oxazolidinones) are also those with the highest oral bioavailability making these agents good candidates for prolonged treatment of outpatients with osteomyelitis (

Table 1). One retrospective study suggested that patients treated preferentially with anti-biofilm antibiotic regimens selected based on transcutaneous bone biopsy for the medical treatment of respectively staphylococcal and gram-negative bacilli DFO had a better remission rate than the other patients treated conventionally (i.e. with standard antibiotics based on superficial samples results like swabs) [

32].

The question of the need for using anti-biofilm antibiotics for the treatment following bone resection or amputation for DFO is also a matter of debate. The identification of bacterial cells aggregated in biofilm structures advocates for using anti-biofilm antibiotics once the culture results are available. On the other hand, these bacterial aggregates seem to be associated with planktonic bacterial cells and to be located on the bone surface which suggests the immature rather than mature status of the biofilm structures visualized on the corresponding proximal bone margins [

33].

No data support any beneficial effect of anti-biofilm antibiotic regimens on the possibility to reduce the duration of DFO antibiotic treatment. Of note, most of the patients who were enrolled in a randomized multicentre study of patients with DFO treated medically that suggested the equivalence between 6 and 12-week duration were given rifampicin and/or fluoroquinolones (either levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin) [

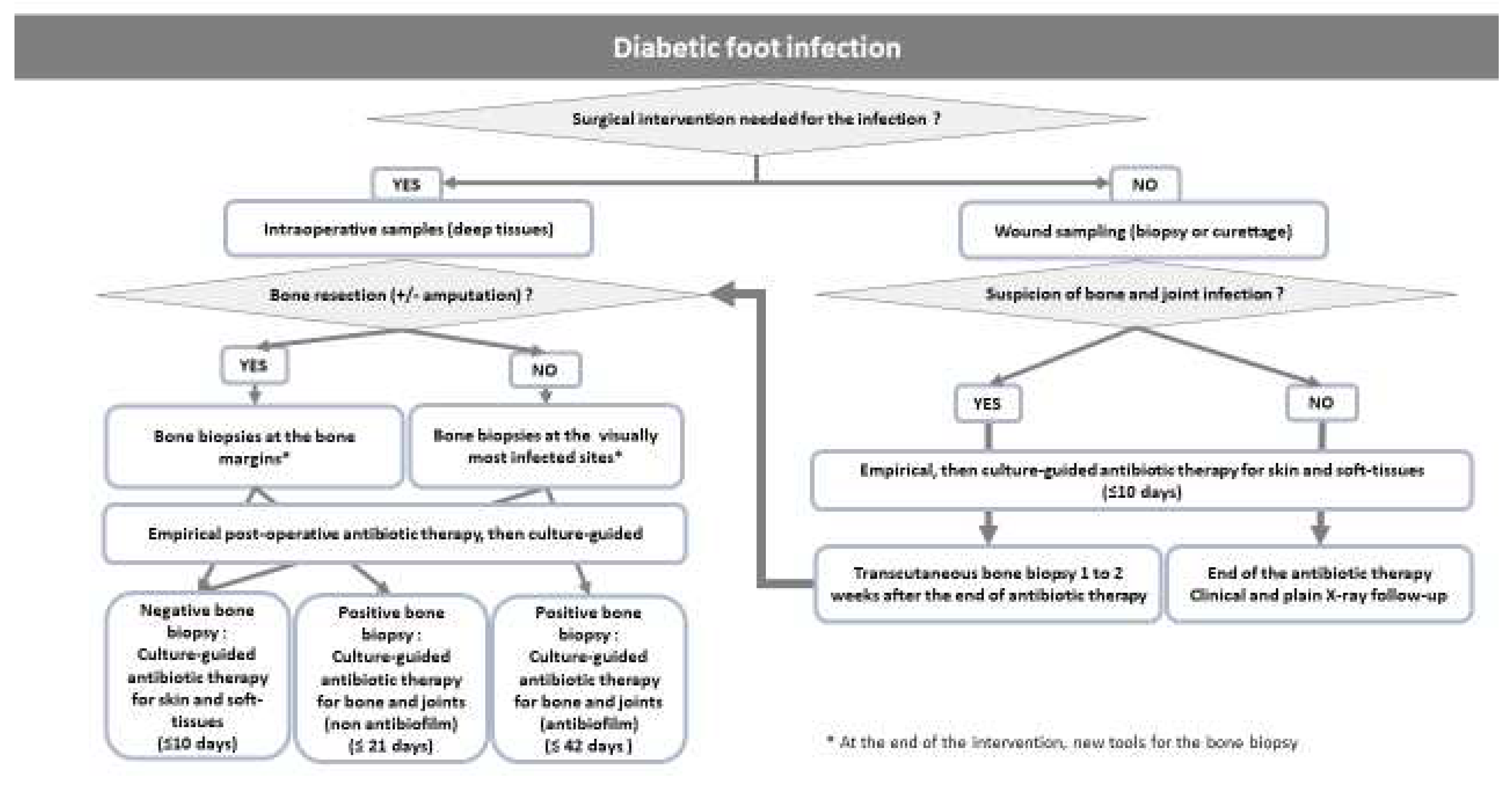

34]. Examples of clinical studies that addressed the outcome of patients with DFO treated medically are shown in

Table 2. A summary of the potential indications of anti-biofilm antibiotics and the duration of treatment according to the type of diabetic foot infections is presented in

Figure 1.

Rifampicin and Fluoroquinolones for the Treatment of DFO

No studies have compared the outcome of treatments of DFOs according to the presence or absence of biofilm. Cohort studies suggest a better outcome when rifampicin or fluoroquinolones are used, but no clear causal relationship has been established with the anti-biofilm effect of these molecules, which have other interesting characteristics in the treatment of bone infections. Nothing indicates that their effect is not only additive to the associated antibiotic and that the therapeutic success comes from the use of two molecules rather than one with interesting properties in the treatment of bone infections. Rifampicin is the only antibiotic for which significant activity against staphylococcal biofilms has been established

in vitro, in animal models, and in human infections. Rifampicin demonstrated potent activity against persister cells in biofilms that exceed that of any other currently available antibiotic [

39]. As such, rifampicin should not be considered as an "adjuvant" therapy but rather as the "effector" antibiotic when combined with a companion for the treatment of biofilm-related infections. One of the weaknesses of rifampicin is the risk of the emergence of resistant mutants in case of high bacterial inoculum especially when rifampicin is used as a monotherapy. There is no convincing data from clinical studies that may help prioritize the choice of the best appropriate companion to associate with rifampicin. The possible interaction with a companion metabolized by the liver is an important parameter to consider when choosing the rifampicin regimen. Rifampicin is, indeed, an inducer of cytochrome P-450 oxidative enzymes and the P-glycoprotein transport system [

40]. Therefore, the serum and tissue concentrations of antibiotics that are substrates of these enzymes are exposed to decreased values. This is the case for clindamycin, linezolid, moxifloxacin, and cotrimoxazole which are exposed to a reduction of 30%-40% of serum concentrations [41-43]. On the opposite, fluoroquinolones and beta-lactams are not exposed to this risk [44-46].

Among the fluoroquinolones, levofloxacin is the most frequently used antibiotic against susceptible strains in combination with rifampicin for the treatment of staphylococcal osteomyelitis with biofilms potentially involved due to low hepatic metabolism, one daily administration, and high tissue concentrations [

47,

48]. Data from in vitro and clinical studies suggest that fluoroquinolones are for gram-negative bacilli biofilms what rifamycins are for staphylococcal biofilms [

20]. Rifampicin combinations should not be debuted before the culture results are available (i.e., as empirical treatment) to avoid rifampicin monotherapy in situations where the staphylococcal strain is susceptible to rifampicin but resistant to the antibiotic associated with rifampicin. Rifampicin combination therapy should be continued until the completion of the treatment for staphylococcal osteomyelitis because the risk of the emergence of resistant mutants is particularly high with these bacteria [

49]. For gram-negative bone infections treated with fluoroquinolones, a combination treatment is only required during the first days of treatment, usually with cephalosporins, then the treatment can be completed with fluoroquinolone monotherapy.

The potential benefit of rifampicin combinations in the medical management of patients with DFO remains a matter of debate. Anti-biofilm antibiotic treatments using rifampicin in combination with a fluoroquinolone (ofloxacin) have already been assessed in patients treated medically for DFOs more than 20 years ago [

50]. Remission defined as the disappearance of all signs and symptoms of infection at the end of the treatment and the absence of relapse during an average follow-up of 22 months was achieved in 76.5% of the cases. More recently, a large US multicentre retrospective study has compared the outcomes of patients treated for a DFO with or without rifampicin for 6 weeks [

51]. Rifampicin had to be initiated within 6 weeks after the diagnosis of DFO and to be administered for at least 14 consecutive days. Half of the patients of both groups of patients underwent debridement without a clear description of what kind of procedure was done especially on the infected bone tissues. Of note, 1271 of 1277 (99.5%)

S. aureus isolates identified with available susceptibility results were rifampicin susceptible. The population included 130 patients treated with rifampicin and 6044 treated without rifampicin. Lower event rates (e.g., amputation after 90 days of diagnosis and deaths) were observed among the rifampicin group (35 of 130 [26.9%] vs 2250 of 6044 [37.2%];

P = .02). There were some significant differences in the profile of the patients such as younger age (mean [SD] age, 62.2 [9.4] vs 64.9 [9.6] years), fewer comorbidities (mean [SD] Charlson comorbidity index score, 3.5 [1.8] vs 4.0 [2.2]), more infectious disease specialty consultations (63 of 130 [48.5%] vs 1960 of 6044 [32.4%]), and more often had

S. aureus identified in cultures (55 of 130 [42.3%] vs 1755 of 6044 [29.0%]) in patients treated with rifampicin than without. The difference between the event rates remained significant after controlling for these and other covariates (odds ratio, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.43-0.96;

P = .04) [

51].

Data Expected in the Next Future

Given the retrospective nature of Wilson’s study, a prospective, randomized, double-blind US multicentre study is currently recruiting intending to confirm the results of the previous report [

52]. In the rifampicin arm, a 6-week rifampicin treatment is "added" to any other antibiotic chosen based on the results of the bone biopsy culture. The primary objective is amputation-free survival in each group. The inclusion criterion is a diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis, as defined by the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot rather than on exclusively bone biopsy results. As for Wilson’s study, the benefit of Rifampicin combinations in patients treated medically might not be established given the fact that patients included can undergo debridement without any precision on to what extent this included bone resection. In addition, using rifampicin as an “adjuvant” for gram-negative DFOs as planned in this study is not supported by the amount of data currently available in the literature on this subject. Finally, the choice of a unique rifampicin daily dosage of 600 mg may lead to low tissue concentrations in obese patients. The results of this important study are awaited in 2024.

Limitations of Rifampicin-Fluoroquinolones for the Treatment of DFO

Rifampicin or fluoroquinolone treatment may lead to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance due to the selection of pre-existing resistant mutants in the bacterial population present in the infected site. The most critical period is therefore the initiation of the treatment when the bacterial inoculum is still high. It seems prudent to consider the initiation of rifampicin treatment after surgery if required (since surgery can result in a rapid and drastic reduction of the bacterial load in the infected tissues). In patients with inflammatory signs of the foot without indication for surgery, rifampicin should be best started after an initial phase of bactericidal and low risk for selection of antimicrobial resistance antibiotic therapy such as beta-lactams and/or glyco(lipo) peptides. For the same reasons, the choice of the rifampicin companion should be based on bone culture results given the low correlation between bone and non-bone culture results [

4,

7]. Routine use of rifampicin combinations is also limited by the frequency of adverse events dominated by nausea, vomiting, hepatic toxicity leading to withdrawing rifampicin (in up to 39% in the Lesens study), and the risk of drug interactions with medications metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, including warfarin, corticosteroids, thyroid hormones, and some antidiabetic agents. The use of rifabutin, a weaker inducer with potent biofilm activity

in vitro in place of rifampicin may be of clinical interest [

54]. It seems prudent to avoid using rifampicin in patients with a suspicion of active tuberculosis due to the risk of the emergence of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis rifampicin-resistant mutants. The high oral bioavailability of rifampicin and fluoroquinolones allow starting the treatment orally as suggested in a recent RCT [

55]. It is, however, important to respect rifampicin taking on an empty stomach and to avoid concomitant use of aluminium- and magnesium-containing antacids and sucralfate, as well as with other metal cations such as calcium and iron with fluoroquinolones [

56].

7. Conclusions

DFO is a frequent complication associated with diabetic foot infections. Gram-positive cocci, especially S. aureus dominate in Western countries while gram-negative, especially Pseudomonas spp. are more prevalent in warm-climate countries. The optimal antibiotic regimens to be used in patients presenting with a DFO have not yet been established in well-designed studies. The majority of patients presenting with a DFO have chronic bone and joint infection and most of the infected bone tissues contain biofilm structures. The choice of antibiotics depends on the therapeutic option, eg., medical versus surgical. The use of antibiotic regimens with anti-biofilm activity especially rifampicin for staphylococcal infections and fluoroquinolones from gram-negative in patients treated medically is supported by a solid background issued from in vitro, animal models, and clinical studies as well but not in patients with DFOs except a couple of retrospective studies. The VA Intrepid study should provide useful data about the place of rifampicin combinations in these settings.

Author Contributions

ES and OR wrote the manuscript, BG and NB revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

ES has received honoraria for consultant activity and speaker bureau from AdvanzPharma, Menarini, and Sanofi. OR, BG and NB declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lavery, L.A.; Armstrong, D.G.; Wunderlich, R.P. , Mohler, M.J.; Wendel, C.S.; Lipsky, B.A. Risk factors for foot infections in individuals with diabetes. Diab. Care. 2006, 29, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prompers, L.; Huijberts, M.; Apelqvist, J.; Jude, E.; Piaggesi, A.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Holstein, P.; Jirkovska, A.; Mauricio, D.; Ragnarson Tennvall, G.; Reike, H.; Spraul, M.; Uccioli, L.; Urbancic, V.; Van Acker, K.; van Baal, J.; van Merode, F.; Schaper, N. High prevalence of ischaemia, infection and serious comorbidity in patients with diabetic foot disease in Europe. Baseline results from the Eurodiale study. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutluoglu, M.; Sivrioglu, A.K.; Eroglu, M.; Uzun, G.; Turhan, V.; Ay, H.; Lipsky, B.A. The implications of the presence of osteomyelitis on outcomes of infected diabetic foot wounds. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 45, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senneville, E.M.; Lipsky, B.A.; van Asten, S.A.V.; Peters, E.J. Diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Diabetes Metab. Res. Revi. End. 2020, 36 Suppl 1; e3250.

- Lavery, L.A.; Sariaya, M.; Ashry, H.; Harkless, L.B. Microbiology of osteomyelitis in diabetic foot infections. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1995, 34, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheat, J. Diagnostic strategies in osteomyelitis. Am. J. Med. 1985, 78, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senneville, E.; Melliez, H.; Beltrand, E.; Legout, L.; Valette, M.; Cazaubiel, M.; Cordonnier, M.; Caillaux, M.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Mouton, Y. Culture of percutaneous bone biopsy specimens for diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: concordance with ulcer swab cultures. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesens, O.; Desbiez, F.; Vidal, M.; Robin, F.; Descamps, S.; Beytout, J.; Laurichesse, H.; Tauveron, I. Culture of per-wound bone specimens: a simplified approach for the medical management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widatalla, A.H.; Mahadi, S.E.; Shawer, M.A.; Mahmoud, S.M.; Abdelmageed, A.E.; Ahmed, M.E. Diabetic foot infections with osteomyelitis: efficacy of combined surgical and medical treatment. Diabet.. Foot Ankle. 2012, 3, 10–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Asten, S.A.; La Fontaine, J.; Peters, E.J.; Bhavan, K.; Kim, P.J.; Lavery, L.A. The microbiome of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 35, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johani, K.; Fritz, B.; G.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Lipsky, B.A.; Jensen, S.O.; Yang, M.; Dean, A.; Hu, H.; Vickery, K.; Malone, M. Understanding the microbiome of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: insights from molecular and microscopic approaches. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25(3), 332-339.

- Pouget, C.; Dunyach-Remy, C. , Magnan, C.; Pantel, A.: Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.P. Polymicrobial Biofilm Organization of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Chronic Wound Environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(18), 10761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, G.; Gonschorek, O.; Hofmann, G.O.; Bührenn, V. Stabilisierungsverfahren bei Osteomyelitis. Osteosyn. Intern. 1997, 5, 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Chantelau, E.; Wolf, A.; Ozdemir, S.; Hachmöller, A.; Ramp, U. Bone histomorphology may be unremarkable in diabetes mellitus. Med. Klin. (Munich). 2007, 102(6), 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragón-Sánchez, F.J.; Cabrera-Galván, J.J.; Quintana-Marrero, Y.; Hernández-Herrero, M.J.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.L.; García-Morales, E.; Beneit-Montesinos, J.V.; Armstrong, D.G. Outcomes of surgical treatment of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: a series of 185 patients with histopathological confirmation of bone involvement. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1962–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebeaux, D.; Chauhan, A.; Rendueles, O.; Beloin, C. From in vitro to in vivo models of bacterial biofilm-related infections. Pathogens 2013, 2(2), 288–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuchscherr, L.; Medina, E.; Hussain, M.; Volker, W.; Heitmann, V.; Niemann, S.; Holzinger, D.; Roth, J.; Proctor, R.A.; Becker, K.; Peters, G.; Loffler, B. Staphylococcus aureus phenotype switching: an effective bacterial strategy to escape host immune response and establish a chronic infection. EMBO. Mol. Med. 2011, 3, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudoux, F.; Neut, C.; Beltrand, E.; Lancelevee, J.; Lebrun, C.; Lemoux, O.; Vambergue, A.; Dubreuil, L.,; Fontaine, P.; Senneville, E. O44 Facteurs de pathogénicité dans l’ostéite du pied diabétique : étude de la charge bactérienne et de la capacité à former un biofilm. Diabetes & Metabolism. 2012, 38 Suppl 2, 11.

- Malone, M.; Fritz, B.G.; Vickery, K.; Schwarzer, S.; Sharma, V.; Biggs, N.; Radzieta, M.; Jeffries, T.T.; Dickson, H.G.; Jensen, S.O.; Bjarnsholt, T. Analysis of proximal bone margins in diabetic foot osteomyelitis by conventional culture, DNA sequencing, and microscopy. APMIS. 2019, 127(10), 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerli, W.; Sendi, P. Orthopaedic biofilm infections. APMIS. 2017, 125(4), 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Espíndola, R.; Vella, V.; Benito, N.; Mur, I.; Tedeschi, S.; Zamparini, E.; Hendriks, J.G.E.; Sorlí, L.; Murillo; O.; Soldevila, L.; Scarborough, M.; Scarborough, C.; Kluytmans, J; Ferrari, M.C.; Pletz, M.W.; McNamara, I.; Escudero-Sanchez, R.; Arvieux, C.; Batailler, C.; Dauchy, F.A.; Liu, W.Y.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Praena, J.; Ustianowski, A.; Cinconze, E.; Pellegrini, M.; Bagnoli, F.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Del Toro, M.D.; ARTHR-IS Group. Rates and Predictors of Treatment Failure in Staphylococcus aureus Prosthetic Joint Infections According to Different Management Strategies: A Multinational Cohort Study-The ARTHR-IS Study Group. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11(6), 2177-2203.

- Oliva, A.; Stefani, S.; Venditti, M.; Di Domenico, E.G. Biofilm-Related Infections in Gram-Positive Bacteria and the Potential Role of the Long-Acting Agent Dalbavancin. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 749685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senneville, E.; Joulie, D.; Legout, L.; Valette, M.; Dezèque, H.; Beltrand, E.; Roselé, B.; d'Escrivan, T.; Loïez, C.; Caillaux, M.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Maynou, C.; Migaud, H. Outcome and predictors of treatment failure in total hip/knee prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora-Tamayo, J.; Murillo, O.; Iribarren, J. A.; Soriano, A.; Sánchez-Somolinos, M.; Baraia-Etxaburu, J.M.; Rico, A.; Palomino, J.; Rodríguez-Pardo, D.; Horcajada, J.P.; Benito, N.; Bahamonde, A.; Granados, A.; del Toro, M.D.; Cobo, J.; Riera, M.; Ramos, A.; Jover-Sáenz, A.; Ariza, J. ; REIPI Group for the Study of Prosthetic Infection A large multicenter study of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections managed with implant retention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pardo, D.; Pigrau, C.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Soriano, A.; del Toro, M.D.; Cobo, J.; Palomino, J.; Euba, G.; Riera, M.; Sánchez-Somolinos, M.; Benito, N.; Fernández-Sampedro, M.; Sorli, L.; Guio, L.; Iribarren, J.A.; Baraia-Etxaburu, J.M.; Ramos, A.; Bahamonde, A.; Flores-Sánchez, X.; Corona, P.S.; REIPI Group for the Study of Prosthetic Infection Gram-negative prosthetic joint infection: outcome of a debridement, antibiotics and implant retention approach. A large multicentre study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014, 20(11), O911–O919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, A. K.; Baldoni, D.; Haschke, M.; Rentsch, K.; Schaerli, P.; Zimmerli, W.; Trampuz, A. Efficacy of daptomycin in implant-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: importance of combination with rifampin. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2009, 53(7), 2719–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valour, F.; Trouillet-Assant, S.; Riffard, N.; Tasse, J.; Flammier, S.; Rasigade, J.P.; Chidiac, C.; Vandenesch, F.; Ferry, T.; Laurent, F. Antimicrobial activity against intraosteoblastic Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59(4), 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Ruiz, J.; Bravo-Molina, A.; Pena-Monje, A.; Hernandez-Quero, J. Activity of linezolid and high-dose Daptomycin, alone or in combination, in an in vitro model of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2682–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeker, D. G.; Beenken, K.E.; Mills, W.B.; Loughran, A.J.; Spencer, H.J.; Lynn, W.B.; Smeltzer, M.S. Evaluation of Antibiotics Active against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Based on Activity in an Established Biofilm. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60(10), 5688–5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, E.J.; Lipsky, B.A.; Berendt, A.R.; Embil, J.M.; Lavery, L.A.; Senneville, E.; Urbančič-Rovan, V.; Bakker, K.; Jeffcoate, W.J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions in the management of infection in the diabetic foot. Diab. Metabol. Res. Rev. 2012, 28 Suppl 1, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landersdorfer, C.B.; Bulitta, J.B.; Kinzig, M.; Holzgrabe, U.; Sörgel, F. Penetration of antibacterials into bone: pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and bioanalytical considerations. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2009, 48(2), 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senneville, E.; Lombart, A.; Beltrand, E.; Valette, M.; Legout, L.; Cazaubiel, M.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Fontaine, P. Outcome of diabetic foot osteomyelitis treated nonsurgically: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2008, 31, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, M.; Fritz, B.G.; Vickery, K.; Schwarzer, S.; Sharma, V.; Biggs, N.; Radzieta, M.; Jeffries, T.T.; Dickson, H.G..; Jensen, S.O.; Bjarnsholt, T. Analysis of proximal bone margins in diabetic foot osteomyelitis by conventional culture, DNA sequencing, and microscopy. APMIS. 2019, 127(10), 660-670.

- Tone, A.; Nguyen, S.; Devemy, F.; Topolinski, H.; Valette, M.; Cazaubiel, M.; Fayard, A.; Beltrand, É.; Lemaire, C.; Senneville, É. Six-week versus twelve-week antibiotic therapy for nonsurgically treated diabetic foot osteomyelitis: a multicenter open-label controlled randomized study. Diabetes Care 2015, 38(2); 302-307.

- Embil, J.M.; Rose, G.; Trepman, E.; Math, M.C.; Duerksen, F.; Simonsen, J.N.; Nicolle, L.E. Oral antimicrobial therapy for diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Foot. Ankle Int. 2006, 27, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valabhji, J.; Oliver, N.; Samarasinghe, D.; Mali, T.; Gibbs, R.G.; Gedroyc, W.M. Conservative management of diabetic forefoot ulceration complicated by underlying osteomyelitis: The benefits of magnetic resonance imaging. Diabet. Med. 2009, 26, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S.; Soliman, M.; Egun, A.; Rajbhandari, S.M. Conservative management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 101, e18–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro-Martinez, J.L.; Aragon-Sanchez, J.; Garcia-Morales, E. Antibiotics versus conservative surgery for treating diabetic foot osteomyelitis: A randomized comparative trial. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlon, B.P.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Fleck, L.E.; LaFleur, M.D.; Isabella, V.M.; Coleman, K.; Leonard, S.N.; Smith, R.D.; Adkins, J.N.; Lewis, K. Activated ClpP kills persisters and eradicates a chronic biofilm infection. Nature 2013, 503(7476), 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baciewicz, A.M.; Chrisman, C.R.; Finch, C.K.; Self, T.H. Update on rifampin and rifabutin drug interactions. Am. Med. Sci. 2008, 335, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera, E.; Pou, L.; Fernandez-Sola, A.; Campos, F.; Lopez, R.M.; Ocaña, I.; Ruiz, I.; Pahissa, A. Rifampin reduces concentrations of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole in serum in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 3238–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeller, V.; Dzeing-Ella, A.; Kitzis, M.D.; Ziza, J.M.; Mamoudy, P.; Desplaces, N. Continuous clindamycin infusion, an innovative approach to treating bone and joint infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandelman, K.; Zhu, T.; Fahmi, O.A.; Glue, P.; Lian, K.; Obach, R.S.; Damle, B. Unexpected effect of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of linezolid: in silico and in vitro approaches to explain its mechanism. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 51, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillaume, M.; Garraffo, R.; Bensalem, M.; Janssen, C.; Bland, S.; Gaillat, J.; Bru, J.P. Pharmacokinetic and dynamic study of levofloxacin and rifampicin in bone and joint infections. Med. Mal. Infect. 2012, 42, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, M.E.; Nahata, M.C. Interaction between ciprofloxacin and rifampicin. Ann. Pharmacother. 1999, 33, 868–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornero, E.; Morata, L.; Martínez-Pastor, J.C.; Angulo, S.; Combalia, A.; Bori, G.; García-Ramiro, S.; Bosch, J.; Mensa, J.; Soriano, A. Importance of selection and duration of antibiotic regimen in prosthetic joint infections treated with debridement and implant retention. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71(5), 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerli, W.; Widmer, A.F.; Blatter, M.; Frei, R.; Ochsner, P.E. Role of rifampin for treatment of orthopedic implant-related staphylococcal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Foreign-Body Infection(FBI) Study Group. JAMA. 1998, 279, 1537–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhto, A.P.; Puhto, T.; Niinimäki; T. ; Ohtonen, P.; Leppilahti, J.; Syrjälä, H. Predictors of treatment outcome in prosthetic joint infections treated with prosthesis retention. Int. Orthop. 2015, 39(9), 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, K.S.; Fraimow, H.S.; Abrutyn, E. Pathogens resistant to antimicrobial agents: epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and clinical management. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 18, 467–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senneville, E.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Cazaubiel, M.; Cordonnier, M.; Valette, M.; Beltrand, E.; Khazarjian, A.; Maulin, L.; Alfandari, S.; Caillaux, M.; Dubreuil, L.; Mouton, Y. Rifampicin-ofloxacin oral regimen for the treatment of mild to moderate diabetic foot osteomyelitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 48, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.M.; Bessesen, M.T.; Doros, G.; Brown, S.T.; Saade, E.; Hermos, J.; Perez, F.; Skalweit, M. , Spellberg, B.; Bonomo, R.A. Adjunctive Rifampin Therapy For Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019, 1, 2(11), e1916003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessesen, M.T.; Doros, G.; Henrie, A.M.; Harrington, K.M.; Hermos, J.A.; Bonomo, R.A.; Ferguson, R.E.; Huang, G.D. Brown ST. A multicenter randomized placebo controlled trial of rifampin to reduce pedal amputations for osteomyelitis in veterans with diabetes (VA INTREPID). BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 8, 20(1), 23.

- Berendt, A.R.; Peters, E.J.; Bakker, K.; Embil, J.M.; Eneroth, M.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Jeffcoate, W.J.; Lipsky, B.A.; Senneville, E.; Teh, J.; Valk, G.D. Diabetic foot osteomyelitis: a progress report on diagnosis and a systematic review of treatment. Diabetes. Metab. Res. Rev. 2008, 24 Suppl 1, S145–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thill, P.; Robineau, O., Roosen, G.; Patoz, P.; Gachet, B.; Lafon-Desmurs, B.; Tetart, M., Nadji, S.: Senneville, E. ; Blondiaux, N. Rifabutin versus rifampicin bactericidal and anti-biofilm activities against clinical strains of Staphylococcus spp. Isolated from bone and joint infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77(4), 1036-1040.

- Li, H.K.; Rombach, I.; Zambellas, R.; Walker, A.S.; McNally, M.A.; Atkins, B.L.; Lipsky, B.A.; Hughes, H.C.; Bose, D.; Kümin, M.; Scarborough, C.; Matthews, P.C.; Brent, A.J.; Lomas, J.; Gundle, R.; Rogers, M.; Taylor, A.; Angus, B.; Byren, I.; Berendt, A.R. ; … OVIVA Trial Collaborators Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for bone and joint infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380(5), 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitman, S.K.; Hoang, U.T.P.; Wi, C.H.; Alsheikh, M.; Hiner, D.A.; Percival, K.M. Revisiting Oral

Fluoroquinolone and Multivalent Cation Drug‐Drug Interactions: Are They Still Relevant? Antibiotics

(Basel) 2019, 8(3), 108.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).