1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus remains among the most prevalent metabolic disease worldwide affecting 4.9 million people in the UK [

1]. Patients suffering from this condition have a lifetime risk of developing diabetic foot ulcer of up to 25% [

2]. The risk of major lower limb amputation in diabetic foot ulcer varies according to region and have been reported to be up to 52% [

3]. A study done in UK even reported 17% amputation within 1 year from initial presentation of an ulcer [

4]. This condition impose a significant burden to the healthcare system with a reported 5 years mortality rate of 50% in diabetic patients with foot ulcer and up to 80% in patients with diabetic related amputations [

5].

The development of ulceration in diabetic patients have been attributed to multifactorial complications of diabetes mellitus which includes peripheral neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, altered immune response, structural deformity and repetitive minor trauma. Despite the best efforts in managing such ulcers, the recurrence rate after ulcer healing is approximately 40% in a year and 60% in 3 years [

6]. This condition is made worse with the presence of infection in 50-60% of cases [

7]. Direct spread of infection through an ulcer to the underlying bone leads to osteomyelitis in up to 20%, severely complicating the management [

8].

The routine management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis involves radical debridement to remove infected tissue and necrotic bone which may include bone resection or partial amputation. This is followed by targeted systemic antibiotic therapy for a long duration and frequent dressings or additional surgeries for wound closure after eradication of infection. The recurrence of infection however was reported to be above 56% and amputation of 83% within 1 year in the presence of osteomyelitis [

9]. Bone and soft tissue void after debridement pose a significant challenge as it delays wound healing, increases risk of reinfection and produces structural vulnerability. The presence of multi-drug resistance microorganisms associated with diabetic foot osteomyelitis along with poor penetration of systemic antibiotics further hinder successful management [

10].

Improved management of bone void is crucial in order to achieve optimal outcomes in treating diabetic foot osteomyelitis. The use of antibiotic incorporated synthetic bone graft substitute which integrate ideal properties such as bioabsorbable, biocompatible and osteoconductive has been reported to be beneficial in the management of bony defects [

11]. Earlier experience in this centre with a new injectable antibiotic biocomposite has reported positive outcomes [

12]. This present study intends to evaluate the effectiveness of antibiotic loaded Calcium Sulphate ceramic (Cerament®, Bonesupport) in eradication of infection, wound healing, prevention of recurrence of infection and limb salvage for diabetic foot osteomyelitis. We further aim to assess patient factors which are associated with treatment outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study involving all patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis treated with antibiotic loaded calcium sulphate ceramic (Cerament G and V) in Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester University Foundation Trust from 2018 to 2023. After considering the inclusion and exclusion criterias, 113 patients were included in this study. Informed consent was obtained from the patients. Information on patient demographics, comorbidities, clinical features, infective status, investigations, surgical procedures, antibiotic treatment and outcomes were collected from the hospital electronic data base system.

Inclusion criterias were consecutive patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis treated with Cerament application. Exclusion criterias were patients without diabetes, lacking evidence of osteomyelitis and lost of follow up. Osteomyelitis in our study is defined clinically as having an ulcer over bony prominence, exposed bone or purulent discharge through a soft tissue sinus, supported by elevated infective markers including white blood cell count and C-reactive protein (CRP) with further confirmation by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, further three phase bone scans were utilized. Body mass index (BMI) were classified based on the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines which defines underweight as BMI less than 18.5, normal 18.5 to 24.9, overweight 25.0-29.9, obesity 30-39.9 and severe obesity more than 40 [

13]. HbA1c in our study is measured in mmol/mol and further divided into good diabetes control from 42 to 58 mmol/mol, suboptimal control 59-75mmol/mol and poor control when more than 75mmol/mol [

14]. Chronic kidney disease is diagnosed from estimate glomerular filtration rate according to NICE guidelines and defined in this study as less than 60 ml/min/1.73m2 (Grade 3a) [

15]. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in this study was defined in agreement to several guidelines by ankle brachial pressure index <0.9 [

16]. This is further confirmed by Duplex ultrasound in all our patients to identify the extent and level of disease.

All included patients underwent methodical debridement of bone and soft tissue for infection source control with multiple deep tissue and bone sampling for culture and sensitivity by foot and ankle consultants. Necrotic bone and infected tissue were removed followed by application of antibiotic carrying biocomposite (Cerament G or V). The Silo technique was often utilized for hindfoot involvement with delivery of biocomposite through pre drilled holes and forefoot involvement through retrograde intramedullary filling [

17]. The antibiotic biocomposite was preferentially applied to bone or as beads to soft tissue to manage post debridement void. The surgical wounds were closed primarily if possible or a vacuum assisted closure (VAC) was applied otherwise. Cerament G were more commonly utilized due to the broad spectrum nature of Gentamicin while Cerament V containing Vancomycin were preferred if previous cultures involved methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and excluded gram negative microorganism.

Patients were followed up by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) involving foot and ankle surgeons, podiatrists, infective disease specialists, diebetologists, plastic and vascular surgeons, diabetes specialist nurses and physiotherapists. The duration of antibiotics were decided during MDT meetings based on culture and sensitivity, patient clinical response and infective markers. In this study, we define eradication of infection as clinical improvement and resolution of infective markers and ulcer healing as complete re-epithelization of wound. Recurrence of ulcer is defined as development of new full thickness lesion at the site of previously healed wound within the study period. All the patients were closely followed up for a minimum of 1 year duration with clinical photographs of wounds, serial radiographs and infective parameters.

To ensure adequate sample size, we performed Cochran’s sample size formula for finite population. Niazi’s study was the previous largest study demonstrating good clinical outcome with the use of adjuvant antibiotic biocomposite in the management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis involving 70 patients [

12]. Setting the margin error value as 0.05, Z-score of 1.96 and drop out rate of 30%, it was recommended to have at least 77 patients to answer the research question. Our study included 113 participants, providing a sufficient sample size to achieve statistical power and effectively validate the observed clinical outcomes.

Statistical analysis was performed to identify factors that affect clinical outcomes. Chi-sqaure and Fisher’s exact test were employed for categorical nature of datasets. Additionally survival analysis were conducted to evaluate patient outcomes over time, specifically assessing the survival rates of dependent variables and identifying potential factors influencing patient prognosis. Analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 26 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

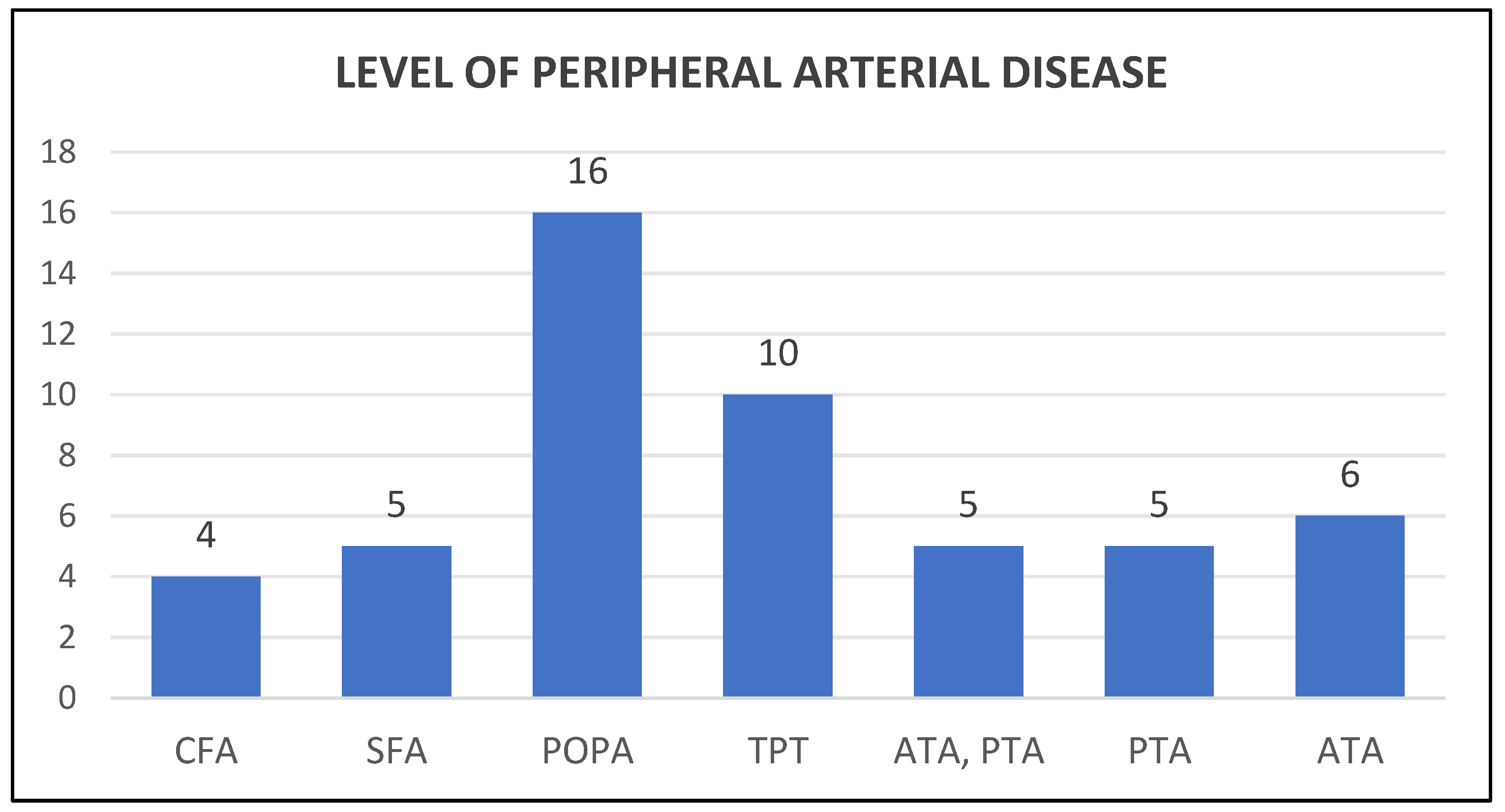

Our study involved 113 patients with mean age of 63.5 years (range 29 to 91 years) and consist of 85 (75%) males and 28 (25%) females. The body mass index (BMI) average was 33.1 (range 20.6 to 64) with 1 underweight, 25 normal, 31 overweight, 42 obese and 14 severely obese. 67 (59%) were non smokers and 46 (41%) were smokers. Hindfoot involvement was the commonest with 60 (54%) cases, followed by forefoot with 41 (37%) cases and midfoot 10 (9%) cases. 32 (29%) of patients suffered from associated Charcot arthropathy and 42 ( 37%) has chronic kidney disease. 51 (45%) of patients had peripheral vascular disease with involvement at the level of common femoral artery (CFA) in 4 cases, superficial femoral artery (SFA) in 5, popliteal artery (POPA) in 16, tibioperoneal trunk (TPT) in 10, both anterior tibial artery (ATA) and posterior tibial artery (PTA) in 5, ATA alone in 6 and PTA alone in 5 (

Figure 1). HbA1c levels averaged at 66.7 mmol/mol (range 30-135) with 33 (29%) well controlled, 35 (31%) suboptimal and 45 (40%) poorly controlled. The C-reactive protein level at time of surgery averaged at 114.49 (range 4 to 451). 88 (78%) of the cases involved Cerament G while 25 (22%) Cerament V.

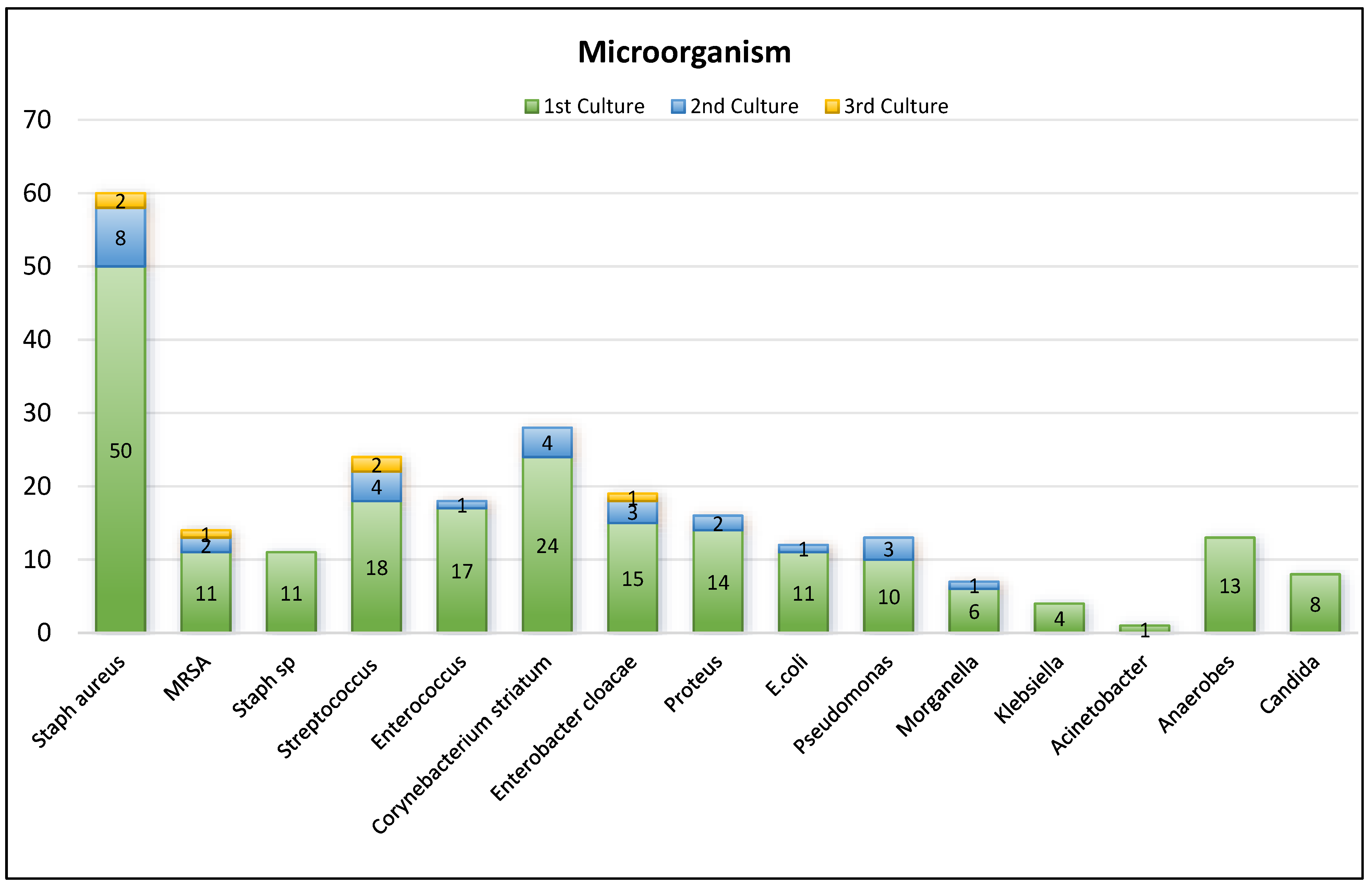

Cultures demonstrated 85 (75%) cases of polymicrobial involvement, 27 (24%) monomicrobial and 1 case where no growth was obtained. Among them, 58 cases (52%) involved gram positive microorganism, 19 (17%) gram negative and 35 (31%) both. Based on cultures, the most common microorganism involved is Staph. aureus and the distribution is demonstrated. (

Figure 2) The duration of antibiotics mean in weeks was 6.86 (range 2-20 weeks) with duration of up to 4 weeks in 29 cases, 4.1-8 weeks in 65, 8.1-12 weeks in 13 and more than 12 weeks in 6 cases.

Eradication of infection was achieved in 108 (96%) cases at a mean duration of 8.84 weeks (range 2-24 weeks). PAD was statistically significant in relation to eradication of infection while BMI and PAD were found to be significantly related to duration of eradication of infection (p-values < 0.05). Healing of ulcer was attained in 105 (93%) cases with mean duration of 16.3 weeks (range 4-54 weeks). PAD and HbA1c were significantly associated with ulcer healing status while HbA1c levels and age were significantly affiliated with duration of ulcer healing (p-values <0.05). Recurrence of ulcer occurred in 23 cases (20%) with all 23 of the cases underwent a second debridement while 6 of them required a third debridement. Recurrence of ulcer has statistical association with PAD, HbA1c and initial CRP levels (p-value <0.05). (

Table 1)

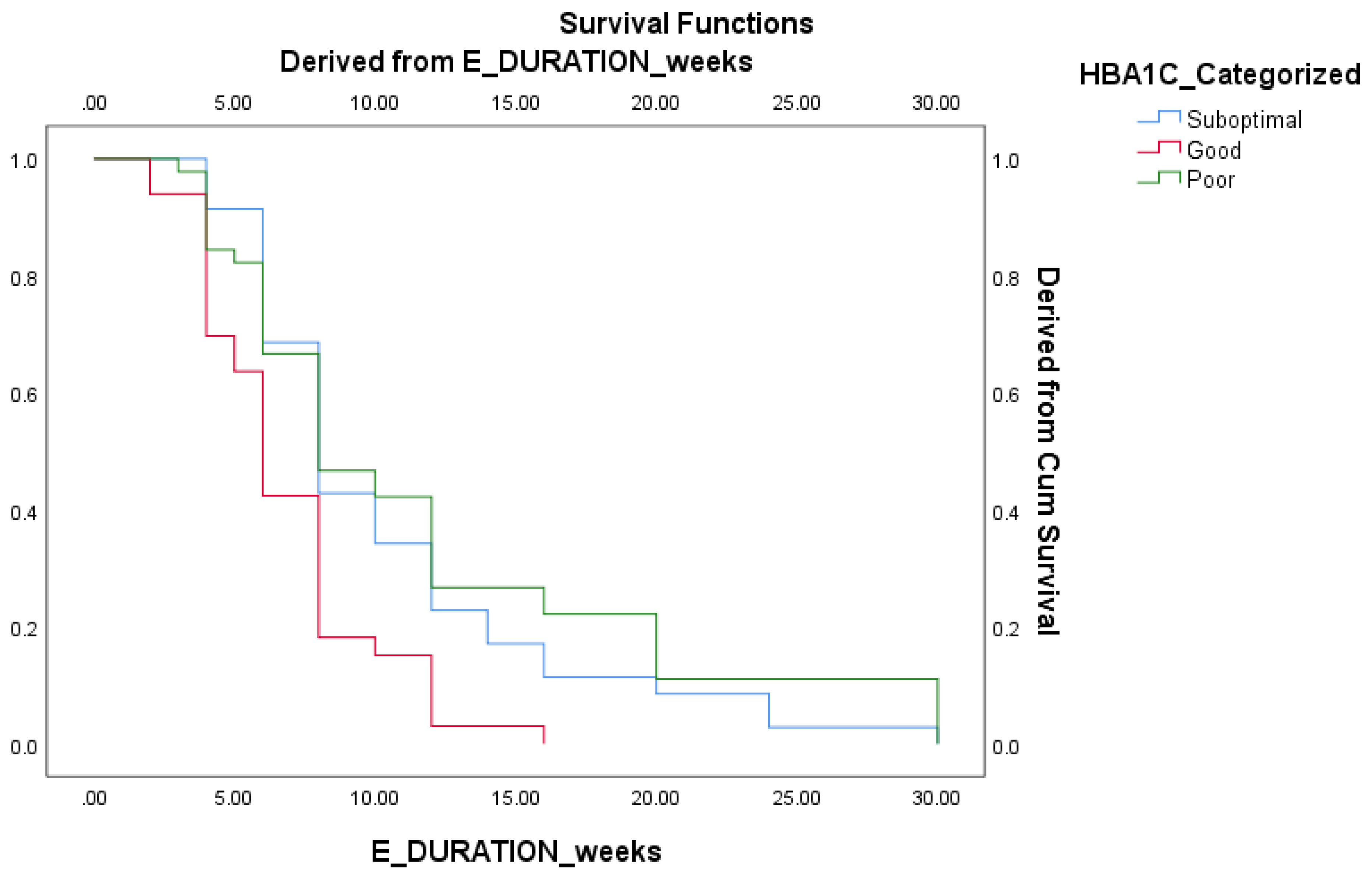

Survival analysis were further performed to determine prognostic indices of various factors to duration based outcomes. Good HbA1c control group demonstrated faster eradication of infection compared to suboptimal and poor control group. (

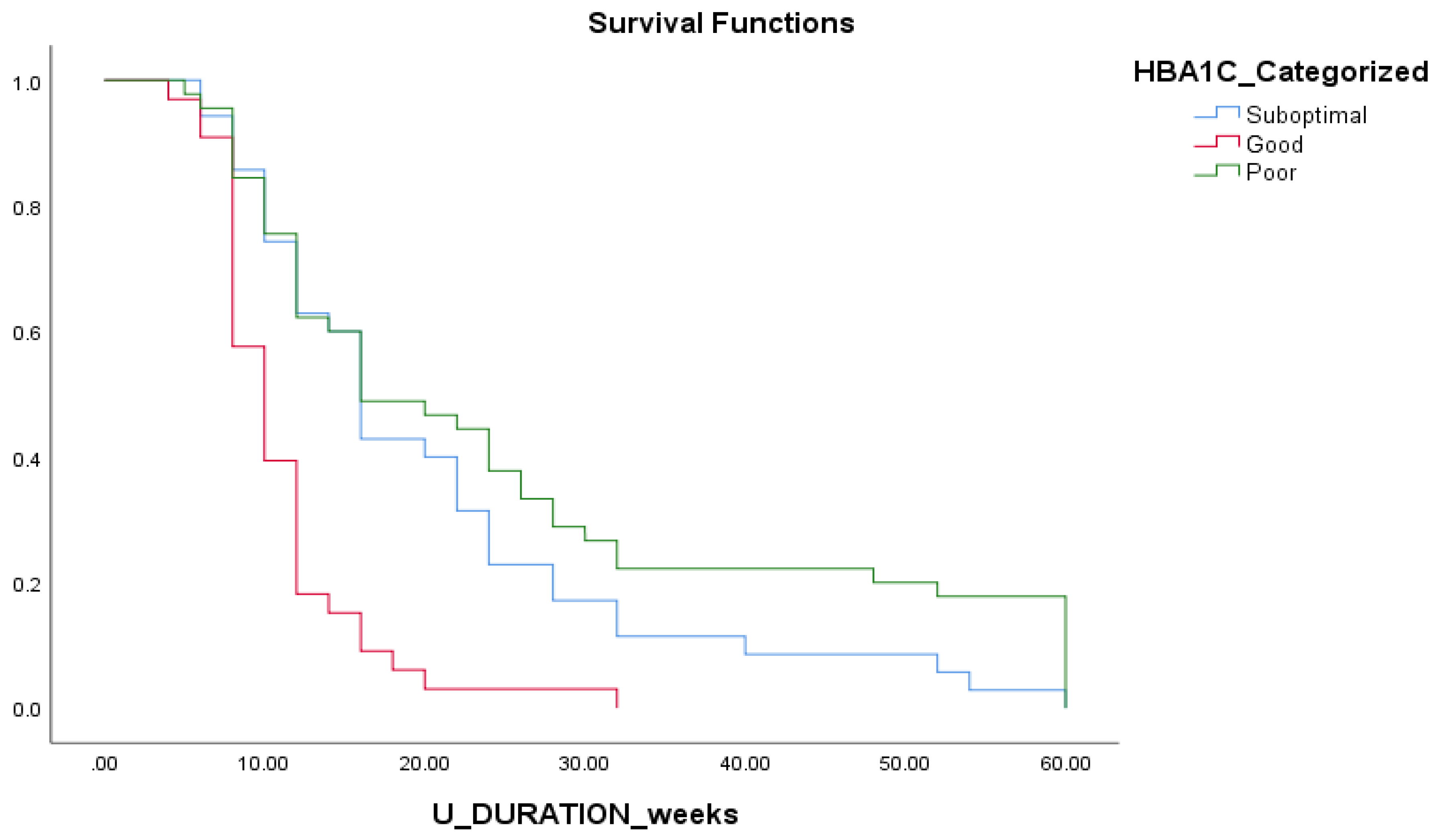

Figure 3) Shorter duration of ulcer healing were also significantly observed in good HbA1c control group compared to suboptimal and longest in the poor control group. (

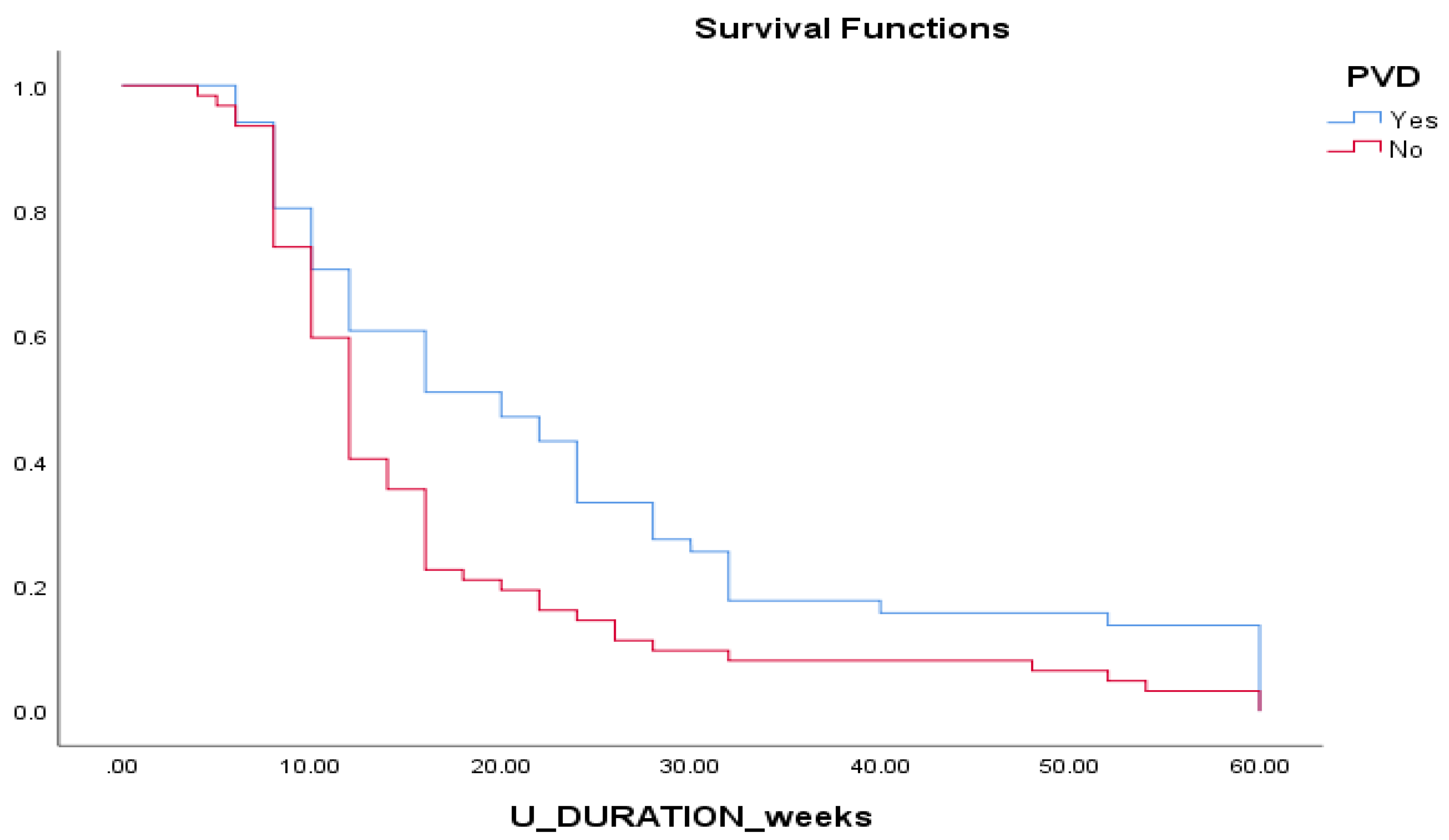

Figure 4) Patients with PAD demonstrated longer duration of ulcer healing compared to patients without. (

Figure 5)

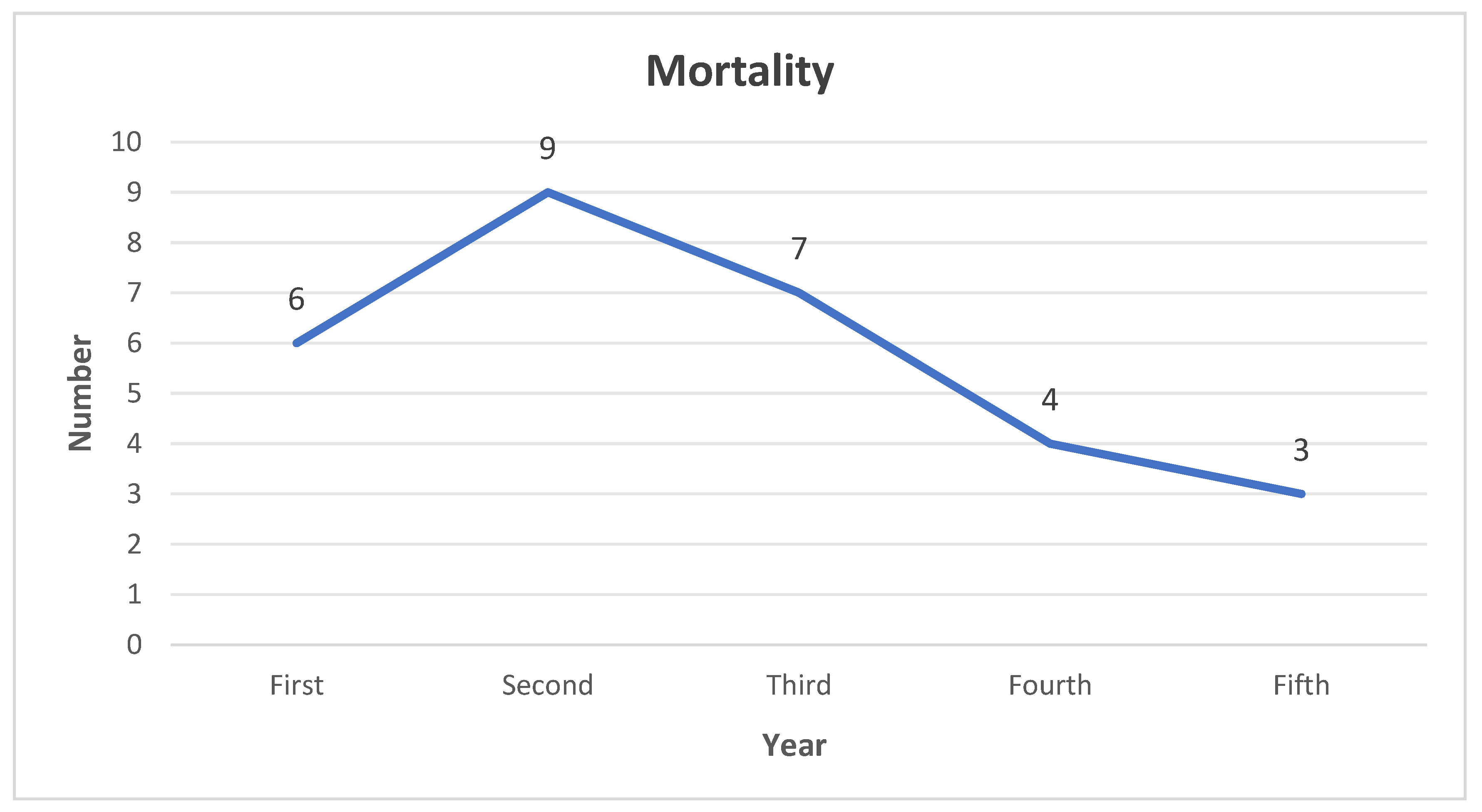

Limb salvage was obtained in 107 (95%) patients while 6 (5%) patients underwent below knee amputation. PAD was found to be statistically significant in relation to limb salvage (p-value <0.05). At the end of this study, 84 (74%) of patients were still alive while 29 (26%) were deceased. 6 patients succumbed within the first year of diagnosis, 9 at second, 7 at third, 4 at fourth and 3 at the fifth year. (

Figure 6) The 1 year mortality rate for this study is 5.30% and 5 years is 25.6%. CKD and CRP levels were found to be significantly associated with patient mortality (p-values < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The presence of osteomyelitis in diabetic foot infections is complicated and often requires meticulous debridement with longer duration of antibiotics. Debridement is usually radical involving osteotomies and resection to achieve successful eradication. This leads to potential dead space with altered structure and load bearing properties of the foot. The presence of biofilms along with defective immune system makes eradication of infection challenging. Biofilms which are aggregates of bacterial colonies encapsulated in self produced extracellular polymeric substances with quorum sensing capability protects bacterial cells from host immune response, antimicrobials and oxidation processes [

18]. A study involving Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in diabetic foot infections revealed most antibiotics tested required much higher doses to achieve minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) and minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) in relation to minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). They further report resistance of biofilms to concentration of antibiotics were 10 to 1000 times compared to concentration required to eliminate free living bacteria [

19].

Antibiotics in diabetes patients is aggravated by various factors such as poor oral absorption, reduced compliance and drug interactions. Hyperglycemia is reported to adversely affect intestinal motility, gastric emptying time and overall mean absorption time [

20]. A systemic review analysed bone penetration in various groups of antibiotics revealed bone concentration were much lower than serum concentration and reported inadequate bone penetration for penicillin and cephalosporin group. The efficacy of systemic antibiotics is further aggravated by the presence of bone defect and vascular pathologies including PAD which results in low concentration of antibiotics locally. Studies involving PAD patients revealed 33-50% of subjects did not achieve satisfactory antibiotics bactericidal activity based on tissue concentration for at least 50% of the time [

21].

The introduction of local antibiotic delivery system has the potential to overcome the limitations of systemic antibiotics. The ability to deliver higher concentration of antibiotics will be effective in dealing with biofilm producing microorganisms without the systemic side effects. The capability to act as dead space filler while providing structural support would be ideal in the management of this condition. In this study, we utilize the advantages of injectable composite, Cerament G and V in the management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. This injectable bioceramic material consist of 60% calcium sulphate and 40% hydroxyapatite which provides compressive strength similar to cancellous bone, thus contributing to sufficient mechanical stability in addition to possessing osteoinductive properties [

22]. The use of Cerament in osteoporotic vertebral fractures has reported good tolerance to motion load stresses and resorption of the product at an equal rate with new bone formation [

23].

Our present study demonstrate eradication of infection of 96% with the use of Cerament G and V in the management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. There is a significant improvement compared to our previously published multicentre study with success rate of 90% [

12]. The success of eradication may be attributed to antibiotic elution from Cerament G and V achieving high initial peak of more than 1000 μg/ml with up to 150 times higher than the minimal inhibitory concentration for up to 3 months, potentially eradicating biofilm as well [

24]. This study further report successful healing of ulcer of 93%, which is higher than our previous study published with 80% [

12]. The calcium sulphate and hydroxyapatite components provide a supportive scaffold for blood vessel in-growth and new bone formation ensuing healthy wound bed for ulcer healing.

This study reported 20% recurrence of ulcer rate which is substantially lower than other studies with the rate of 37 to 58% treated with conventional debridement and systemic antibiotics [

25,

26]. We achieved limb salvage in 95% of our patients with 6 patients (5%) underwent lower extremity amputation. Various studies has demonstrated higher amputation rate of 10.0 to 58.8% in the presence of diabetic foot ulcer with reported odds ratio of 3.7 in the presence of osteomyelitis [

27]. This study also reported mortality rate of 5.4% at 1 year and 25.6% at 5 years. This is significantly lower than other studies demonstrating mortality rate of up to 13.2% at 1 year and 50% at 5 years [

28,

29]. This could be associated with the eradication of infection and wound healing rate, thereby preventing amputation which is a significant contributing factor to mortality rate.

Diabetic foot osteomyelitis is particularly difficult to manage due to the systemic effects of hyperglycemic status in diabetis mellitus affecting all components of proper wound healing namely neuropathy, vasculopathy and immunopathy [

30]. The presence of other conditions such as PAD, metabolic syndrome, CKD and Charcot neuropathy may further complicate the treatment outcome. Age was found not to directly impair wound healing but the higher prevalence of comorbidities, alteration in aging skin and altered wound healing process at molecular level during hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and tissue remodeling phases may lead to delay in healing [

31]. Our study report statistically significant association between increase in age to prolonged duration of wound healing, similar to other studies involving much larger patient cohort [

32]. There was however no association between age to eradication of infection duration, limb salvage or recurrence of ulcer.

Obesity has been reported to impact wound healing mainly due to prolonged inflammatory state with elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines resulting in impaired immune response during healing phases [

33]. With higher prevalence of other medical comorbidities, obesity has been demonstrated to complicate diabetic ulcer healing with higher risk of lower extremity amputations [

34]. This study report a significant association between BMI and eradication of infection duration but not to ulcer healing, recurrence of infection or amputation. PAD directly impairs blood supply and has been reported to have poorer prognosis, delayed wound healing, higher recurrence of infection and higher risk of amputations [

35]. The pattern of PAD in diabetes patients are also known to be more complicated due to defective arterial remodeling leading to diffuse involvement with failure of compensatory vessel lumen enlargement; and with a more distal predominance [

36]. Our study demonstrate a significant association of PAD with success of eradication of infection, duration of eradication, ulcer healing, recurrence of ulcer and limb salvage.

HbA1c is the commonest tool in diagnosing and monitoring control of diabetes mellitus. Hyperglycemic state has been reported to impair wound healing directly by alteration in keratinocyte migration and reactive oxygen species causing oxidative stress [

37]. Higher HbA1c levels were reported to be associated with longer duration of wound healing, increased non healing ulcers and higher risk of amputation [

38,

39]. The present study report a significant association of HbA1c levels with success of wound healing, duration of wound healing and recurrence of ulcer. Chronic kidney disease is known to influence wound healing due to a uraemic state adversely affecting fibroblast proliferation, collagen production and platelet function leading to delayed granulation and cell proliferation [

40]. At later stages of the disease, acid-base disorders, electrolyte imbalance, edema and secondary hyperparathyroidism may further impair healing. CKD has also been reported to be associated with higher mortality risk and lower extremity amputations [

41]. Our study demonstrate similar association only in terms of mortality.

CRP is a valuable infective marker for diagnosis and monitoring of diabetic foot infections by estimating the infective burden and extent of disease. In terms of outcomes, initial CRP value was reported to be associated with treatment failure namely persistence of infection and amputation risk [

42]. In this study, initial CRP was demonstrated to have significant association with recurrence of ulcer and mortality. Other parameters such as gender, BMI, smoking status, part of foot, charcot arthropathy, microorganism factors and duration of antibiotics do not have any bearing on the final treatment outcomes. These parameters should not serve a barrier to limb salvage surgery as predictable good results can be achieved regardlessly with the use of antibiotic loaded calcium sulphate ceramic.

We acknowledge that there are several limitations to our study. This is a retrospective study describing the use of a single technique of local antibiotic therapy. A comparative study would be more significant in reflecting clinical outcomes and identifying factors affecting the outcomes. Longer follow-up duration would improve the assessment of long-term outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This is the largest single centre study involving Cerament G and V in the management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis and the first to evaluate factors associated to the outcome goals. The addition of antibiotic loaded calcium sulphate ceramic demonstrated excellent clinical outcomes with regards to eradication of infection, healing of ulcer, recurrence of ulcer, limb salvage and mortality rate. Based on the results, HbA1c and PAD were the only modifiable factors which could promote better outcomes, highlighting the importance of diabetic control and treatment of underlying PAD. All other parameters have no impact on treatment outcomes and predictable good results can be obtained irrespectively. Further studies namely randomized controlled trials may further improve our treatment decisions and potentially reducing the use of systemic antibiotics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation A.P; Data collection: K.T., J.M. and S.M; Writing, literature review and editing: K.T.; Supervision: A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been approved by Department of Clinical Audit with ID 910512024. Discussion with the hospital trust Research & Innovation Department, and using the NHS Health Research Authority’s online tool, the project was deemed to be a service evaluation. Further ethical approval was not required as patients’ management was not affected in any way and treatment had already been provided.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No data is provided due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all patients and the staffs at the Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) who contributed to the management of patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Results. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- Boulton, A.J.M.; Armstrong, D.G.; Albert, S.F.; Frykberg, R.G.; Hellman, R.; Kirkman, M.S.; Lavery, L.A.; LeMaster, J.W.; Mills, J.L.; Mueller, M.J.; Sheehan, P.; Wukich, D.K. Comprehensive Foot Examination and Risk Assessment: A Report of the Task Force of the Foot Care Interest Group of the American Diabetes Association, with Endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1679–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edo, A.; Edo, G.; Ezeani, I. Risk Factors, Ulcer Grade and Management Outcome of Diabetic Foot Ulcers in a Tropical Tertiary Care Hospital. Nigerian Medical Journal 2013, 54, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, J.F.; Fuller, G.W.; Vowden, P. Diabetic Foot Ulcer Management in Clinical Practice in the UK: Costs and Outcomes. International Wound Journal 2017, 15, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Wrobel, J.; Robbins, J.M. Guest Editorial: Are Diabetes-Related Wounds and Amputations Worse than Cancer? International Wound Journal 2007, 4, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Boulton, A.J.M.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 376, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prompers, L.; Huijberts, M.; Apelqvist, J.; Jude, E.; Piaggesi, A.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Holstein, P.; Jirkovska, A.; Mauricio, D.; Ragnarson Tennvall, G.; Reike, H.; Spraul, M.; Uccioli, L.; Urbancic, V.; Van Acker, K.; van Baal, J.; van Merode, F.; Schaper, N. High Prevalence of Ischaemia, Infection and Serious Comorbidity in Patients with Diabetic Foot Disease in Europe. Baseline Results from the Eurodiale Study. Diabetologia 2006, 50, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, L.A.; Peters, E.J.G.; Armstrong, D.G.; Wendel, C.S.; Murdoch, D.P.; Lipsky, B.A. Risk Factors for Developing Osteomyelitis in Patients with Diabetic Foot Wounds. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2009, 83, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, L.A.; Ryan, E.C.; Ahn, J.; Crisologo, P.A.; Oz, O.K.; La Fontaine, J.; Wukich, D.K. The Infected Diabetic Foot: Re-Evaluating the IDSA Diabetic Foot Infection Classification. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabit, A.K.; Fatani, D.F.; Bamakhrama, M.S.; Barnawi, O.A.; Basudan, L.O.; Alhejaili, S.F. Antibiotic Penetration into Bone and Joints: An Updated Review. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2019, 81, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Athanasou, N.; Diefenbeck, M.; McNally, M. Radiographic and Histological Analysis of a Synthetic Bone Graft Substitute Eluting Gentamicin in the Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis. Journal of Bone and Joint Infection 2019, 4, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, N.S.; Drampalos, E.; Morrissey, N.; Jahangir, N.; Wee, A.; Pillai, A. Adjuvant Antibiotic Loaded Bio Composite in the Management of Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis — a Multicentre Study. The Foot 2019, 39, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Overview | Overweight and Obesity Management | Guidance | NICE. Nice.org.uk. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng246.

- Braatvedt, G.D.; Cundy, T.; Crooke, M.; Florkowski, C.; Mann, J.I.; Lunt, H.; Jackson, R.; Orr-Walker, B.; Kenealy, T.; Drury, P.L. Understanding the New HbA1c Units for the Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes. The New Zealand Medical Journal 2012, 125, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Overview | Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management | Guidance | NICE. Nice.org.uk. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182.

- Meijer, W.T.; Hoes, A.W.; Rutgers, D.; Bots, M.L.; Hofman, A.; Grobbee, D.E. Peripheral Arterial Disease in the Elderly. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 1998, 18, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drampalos, E.; Mohammad, H.R.; Kosmidis, C.; Balal, M.; Wong, J.; Pillai, A. Single Stage Treatment of Diabetic Calcaneal Osteomyelitis with an Absorbable Gentamicin-Loaded Calcium Sulphate/Hydroxyapatite Biocomposite: The Silo Technique. The Foot 2018, 34, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyofuku, M.; Inaba, T.; Kiyokawa, T.; Obana, N.; Yawata, Y.; Nomura, N. Environmental Factors That Shape Biofilm Formation. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2015, 80, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottola, C.; Matias, C.S.; Mendes, J.J.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Tavares, L.; Cavaco-Silva, P.; Oliveira, M. Susceptibility Patterns of Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms in Diabetic Foot Infections. BMC Microbiology 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adithan, C.; Sriram, G.; Swaminathan, R.P.; Shashindran, C.H.; Bapna, J.S.; Krishnan, M.; Chandrasekar, S. Differential Effect of Type I and Type II Diabetes Mellitus on Serum Ampicillin Levels. International journal of clinical pharmacology, therapy, and toxicology 1989, 27, 493–498. [Google Scholar]

- Vladimíra Fejfarová; Radka Jarošíková; Antalová, S.; Jitka Husáková; Wosková, V.; Pavol Beca; Jakub Mrázek; Petr Tůma; Polák, J.; Dubský, M.; Dominika Sojáková; Věra Lánská; Petrlík, M. Does PAD and Microcirculation Status Impact the Tissue Availability of Intravenously Administered Antibiotics in Patients with Infected Diabetic Foot? Results of the DFIATIM Substudy. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Wang, J.-S.; Wielanek, L.; Tanner, K.E.; Lidgren, L. Biodegradation and Biocompatability of a Calcium Sulphate-Hydroxyapatite Bone Substitute. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - British Volume 2004, 86-B, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masala, S.; Nano, G.; Marcia, S.; Muto, M.; Paolo, F.; Simonetti, G. Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures Augmentation by Injectable Partly Resorbable Ceramic Bone Substitute (CeramentTM|SPINE SUPPORT): A Prospective Nonrandomized Study. Neuroradiology 2011, 54, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatten, H.P.; Voor, M.J. Bone Healing Using a Bi-Phasic Ceramic Bone Substitute Demonstrated in Human Vertebroplasty and with Histology in a Rabbit Cancellous Bone Defect Model. Interventional Neuroradiology 2012, 18, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Ying, G.; Jing, O.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, M.; Long, S. Influencing Factors for the Recurrence of Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Meta-Analysis. International Wound Journal 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubský, M.; Jirkovská, A.; Bem, R.; Fejfarová, V.; Skibová, J.; Schaper, N.C.; Lipsky, B.A. Risk Factors for Recurrence of Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Prospective Follow-up Analysis in the Eurodiale Subgroup. International Wound Journal 2012, 10, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Liu, J.; Sun, H. Risk Factors for Lower Extremity Amputation in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0239236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.; Scatena, A.; Tacconi, D.; Ventoruzzo, G.; Liistro, F.; Bolognese, L.; Monami, M.; Mannucci, E. All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in a Consecutive Series of Patients with Diabetic Foot Osteomyelitis. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2017, 131, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, S.; Gao, Y.; Ran, X. Global Mortality of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G. New Insights into the Pathophysiology of Diabetic Nephropathy: From Haemodynamics to Molecular Pathology. European Journal of Clinical Investigation 2004, 34, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgonc, R.; Gruber, J. Age-Related Aspects of Cutaneous Wound Healing: A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2013, 59, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fife, C.E.; Horn, S.D.; Smout, R.J.; Barrett, R.S.; Thomson, B. A Predictive Model for Diabetic Foot Ulcer Outcome: The Wound Healing Index. Advances in Wound Care 2016, 5, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterell, A.; Griffin, M.; Downer, M.A.; Parker, J.B.; Wan, D.; Longaker, M.T. Understanding Wound Healing in Obesity. World Journal of Experimental Medicine 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikntaa, K.S.; Monisha, G. A Comparative Study of Diabetic Foot Outcome between Normal vs. High BMI Individuals-Is Obesity Paradox a Fallacy in Ulcer Healing. Clinics in Surgery 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faglia, E.; Favales, F.; Quarantiello, A.; Calia, P.; Clelia, P.; Brambilla, G.; Rampoldi, A.; Morabito, A. Angiographic Evaluation of Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease and Its Role as a Prognostic Determinant for Major Amputation in Diabetic Subjects with Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 1998, 21, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Der, V.; Neijens, F. S.; S. D. J. M. Kanters; Th., P.; Stolk, R. P.; Banga, J. D. Angiographic Distribution of Lower Extremity Atherosclerosis in Patients with and without Diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 2002, 19, 366–370. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; DiPietro, L.A. Factors Affecting Wound Healing. Journal of Dental Research 2010, 89, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, L.; Gatt, A.; Formosa, C. Does Baseline Hemoglobin A1c Level Predict Diabetic Foot Ulcer Outcome or Wound Healing Time? Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 2017, 107, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.I.; Boyko, E.J.; Ahroni, J.H.; Smith, D.G. Lower-Extremity Amputation in Diabetes. The Independent Effects of Peripheral Vascular Disease, Sensory Neuropathy, and Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroz, N.; Simman, R. Wound Healing in Patients with Impaired Kidney Function. Journal of the American College of Clinical Wound Specialists 2013, 5, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, S.; Gao, Y.; Ran, X. Global Mortality of Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Kim, W.H.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, M.S.S. Risk Factors of Treatment Failure in Diabetic Foot Ulcer Patients. Archives of Plastic Surgery 2013, 40, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).