1. Introduction

Obesity is now recognized as one of the most critical global health concerns, strongly associated with the increasing rates of type 2 diabetes and other metabolic complications [

1]. While lifestyle interventions such as regular exercise and calorie restriction remain fundamental components of weight control [

2], their long-term success is often modest. Typically, individuals achieve weight reductions of around 5–10% through dietary adjustments, 5–20% with pharmacological approaches, and 20–30% or more with bariatric surgery [

3]. Yet, these methods alone seldom guarantee lasting outcomes. A recent meta-analysis revealed that nearly 50% of the weight lost is regained within two years, and close to 80% is regained after five years [

4].

The advent of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) has transformed obesity treatment, achieving weight losses of approximately 15–25% within 12–24 months without the need for surgery, while also markedly improving cardiometabolic health [

5]. However, stopping the therapy often results in rapid weight regain, highlighting the persistence of an “obesity memory” within adipose tissue [

6]. This phenomenon is marked by chronic low-grade inflammation, disrupted tissue remodeling, and enduring epigenetic alterations that predispose individuals to metabolic relapse and disproportionate fat accumulation compared to lean mass recovery [

7,

8]. Both clinical and experimental studies suggest that GLP-1–based treatments can negatively affect lean body mass, raising concerns about sarcopenia and vulnerability in older individuals [

9]. Similarly, in animal models, GLP-1–driven weight reduction has been linked to disproportionate losses in muscle tissue, while subsequent weight regain tends to occur through rapid fat deposition accompanied by impaired adipose tissue remodeling [

10,

11].

Another challenge is the limited adherence to GLP-1 therapy, as high costs and adverse effects lead to discontinuation rates approaching two-thirds within the first year, although nearly half of these patients may eventually restart treatment [

12]. Observational studies show that such cycles of stopping and resuming—commonly referred to as weight cycling—are linked to greater fat mass regain relative to lean mass restoration, which may heighten the likelihood of sarcopenic obesity [

13,

14,

15]. This syndrome, defined by excess fat alongside reduced muscle mass, affects 10–20% of older adults and is associated with frailty, diminished physical function, and increased morbidity [

16].

Collectively, these observations highlight the pressing need for supportive approaches that can ensure long-term weight maintenance and safeguard muscle health. Among such strategies, dietary protein intake has emerged as a critical factor. Although current guidelines largely focus on the amount of protein consumed, the influence of different protein sources—such as plant-based, dairy, or novel sustainable options—on adipose remodeling, epigenetic marks, and the risk of sarcopenic obesity is still not well clarified [

17,

18]. While many clinical trials confirm that higher protein consumption enhances satiety and aids weight stability, the specific mechanisms by which distinct protein types affect adipose tissue biology, inflammatory status, and epigenetic regulation remain insufficiently understood [

19,

20].

This review seeks to integrate recent evidence on how various protein sources affect adipose tissue flexibility, epigenetic regulation, and the maintenance of muscle mass, with particular emphasis on their contribution to sustaining weight loss and reducing the risk of sarcopenic obesity, particularly in the context of GLP-1–induced weight reduction.

2. Protein Quality and Body Composition

Protein functions not only as a key regulator of energy balance but also as a central factor in shaping body composition and overall metabolic health. Emerging evidence highlights that beyond the total amount consumed, protein quality—defined by its amino acid composition, digestibility, and bioavailability—plays a decisive role in influencing satiety, thermogenesis, the preservation of lean mass, and the maintenance of long-term weight stability [

19,

20]. Taken together, these insights suggest that dietary protein impacts health outcomes through more than quantity alone, with the unique biological characteristics of animal- and plant-based proteins emphasizing the need to distinguish their metabolic contributions.

3. Protein Source–Specific Mechanisms in Adipose Tissue

Protein sources differ in their impacts on adipose tissue biology, muscle maintenance, and overall metabolic regulation. Dairy proteins, with their high leucine levels and rapid digestion rates, are particularly effective in stimulating satiety pathways and muscle protein synthesis [

21]. In contrast, plant proteins contribute unique benefits through anti-inflammatory compounds and interactions with the gut microbiota that enhance metabolic health [

22]. Beyond these effects, plant-based proteins also provide advantages related to sustainability. Well-studied examples include soy and pea proteins, which are rich in isoflavones and ACE-inhibitory peptides that can lower inflammation, improve insulin sensitivity, and promote satiety hormone release [

23,

24]. Interest has also expanded to novel protein sources; for instance, banana peel protein shows promise in strengthening gut barrier function and supporting epigenetic adaptability, potentially counteracting the “obesity memory” associated with post-treatment weight regain [

25,

26,

27]. Collectively, these mechanisms highlight the capacity of protein quality to shape adipose tissue remodeling and muscle preservation, underscoring the critical role of protein source in promoting long-term metabolic resilience and healthy aging.

4. Epigenetic Remodeling and “Obesity Memory”

Weight regain after intentional weight loss is increasingly viewed not merely as a behavioral or metabolic issue, but as a process influenced by persistent epigenetic changes in adipose tissue. These alterations—such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and regulation by non-coding RNAs—create an “obesity memory” that sustains chronic low-grade inflammation, limits adipose tissue adaptability, and promotes excessive fat accumulation in relation to lean mass [

28,

29,

30].

Evidence from human studies supports this idea. Research on patients undergoing bariatric surgery or lifestyle interventions has shown extensive DNA methylation changes in adipose tissue, with some alterations persisting even after weight loss and remaining associated with metabolic outcomes [

27]. Moreover, Hoffstedt et al. [

31] tracked obese women for five years following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and found sustained improvements in adipose tissue characteristics—such as reduced adipocyte size, decreased lipolysis, and elevated adiponectin levels—even when partial weight regain occurred. Although specific epigenetic markers (e.g., DNA methylation or histone modifications) were not measured in this study, these long-term functional benefits reinforce the notion of a “metabolic memory” in adipose tissue that may parallel or be driven by lasting epigenetic changes [

32].

Preclinical findings add further support to this concept. In a recent mouse model of diet-induced obesity, Hinte et al. [

6] showed that obesity-associated epigenetic alterations in adipocytes—particularly changes in enhancer and promoter regions—remained even after weight loss. When the animals were re-exposed to a high-fat diet, they regained weight more rapidly than controls, offering direct evidence for an epigenetic “obesity memory” within adipose tissue.

Protein-derived signals can influence chromatin architecture, transcriptional activity, and metabolite supply, thereby either reinforcing or weakening obesity-related epigenetic marks, ultimately shaping metabolic resilience and altering the likelihood of relapse and sarcopenic obesity [

27]. Recent evidence suggests that protein quality may regulate epigenetic remodeling through multiple pathways. The amino acid profile—particularly methionine and branched-chain amino acids—can impact one-carbon metabolism and methyl donor availability, leading to changes in DNA methylation within adipose tissue [

3]. In addition, bioactive peptides released during protein digestion may directly affect histone-modifying enzymes, such as acetyltransferases and deacetylases, altering transcriptional accessibility. Plant-derived proteins also contribute indirectly through gut microbiota, which generate short-chain fatty acids like butyrate that act as powerful epigenetic modulators [

33,

34].

These mechanisms carry significant clinical relevance. During pharmacological weight loss with GLP-1 receptor agonists or dual incretin therapies, the persistence of obesity-related epigenetic alterations may predispose patients to rapid relapse once treatment ends [

34,

35]. Ensuring sufficient intake of high-quality protein throughout weight loss and maintenance phases could help counter this risk by preserving lean body mass and dampening pro-obesogenic epigenetic patterns [

36]. In older adults, sustaining skeletal muscle through protein intake is particularly crucial to prevent sarcopenic obesity—a condition strongly linked with reduced metabolic flexibility, frailty, and adverse cardiometabolic outcomes. Overall, these findings emphasize protein quality as a modifiable factor that integrates nutritional, epigenetic, and clinical aspects of obesity management [

36,

37].

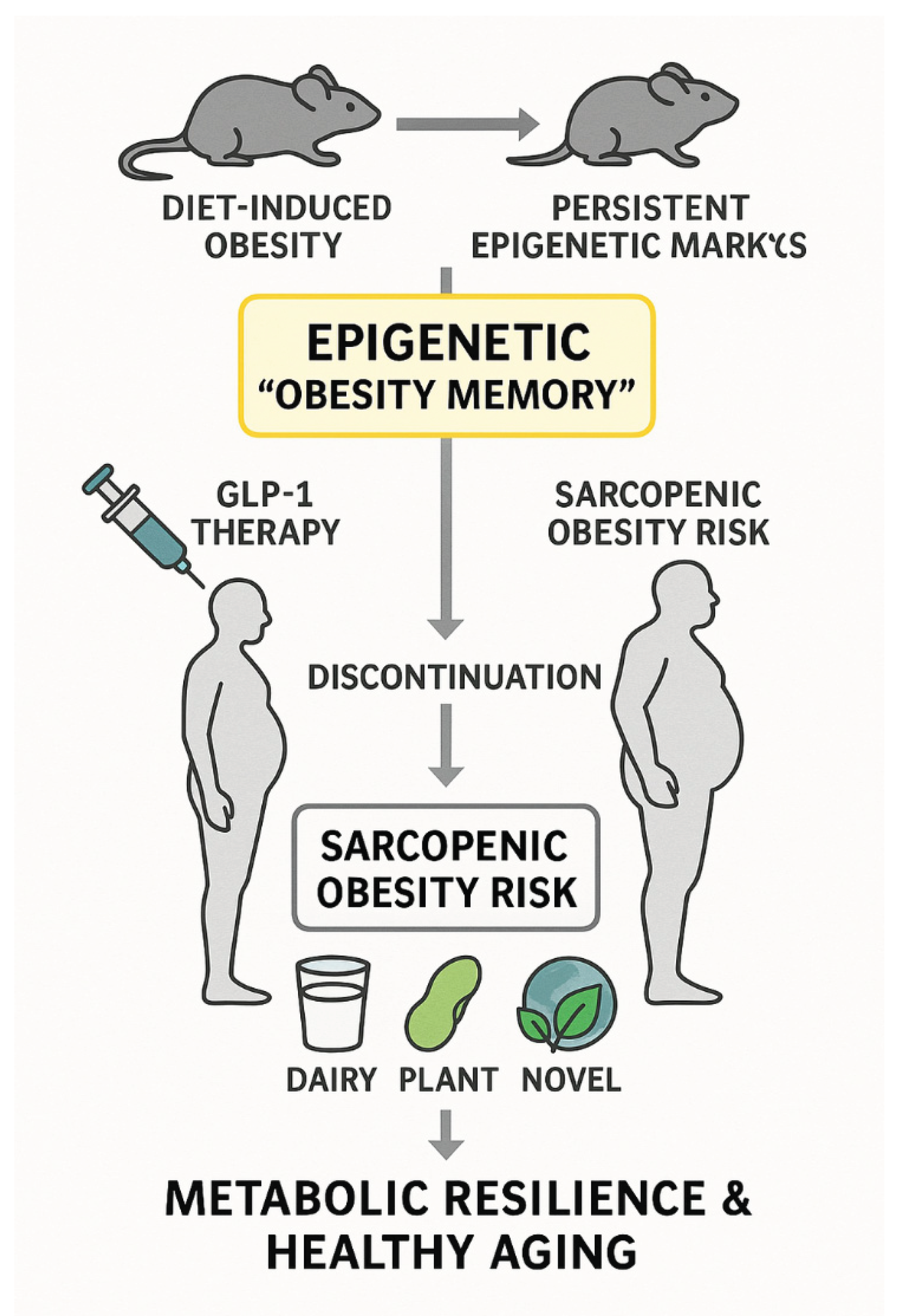

Figure 1 provides a conceptual overview of how persistent epigenetic “obesity memory” interacts with protein sources to influence long-term weight control and sarcopenic obesity risk.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of dietary protein sources and epigenetic “obesity memory. This schematic summarizes how protein source (dairy, plant-based, and novel sustainable proteins) may influence adipose tissue plasticity, epigenetic remodeling, and lean mass preservation, thereby modulating the risk of weight regain and sarcopenic obesity in the context of pharmacological weight loss.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of dietary protein sources and epigenetic “obesity memory. This schematic summarizes how protein source (dairy, plant-based, and novel sustainable proteins) may influence adipose tissue plasticity, epigenetic remodeling, and lean mass preservation, thereby modulating the risk of weight regain and sarcopenic obesity in the context of pharmacological weight loss.

5. Clinical Evidence: Protein Intake and Weight Maintenance

Clinical research consistently shows that higher protein intake facilitates weight loss maintenance and helps preserve lean body mass during periods of caloric restriction. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) indicate that diets providing 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day of protein are more effective than the standard dietary allowance of 0.8 g/kg/day in sustaining fat-free mass and metabolic rate during weight reduction [

20]. This protective effect of protein is particularly important for individuals using pharmacological weight loss therapies, where the risk of losing disproportionate amounts of lean tissue is increased.

Beyond total intake, the type of protein consumed is also significant. Dairy proteins, especially whey, have been widely studied for their impact on satiety, muscle protein synthesis, and body composition [

21,

37]. For instance, whey protein supplementation during energy restriction has been shown to reduce muscle loss and improve post-meal satiety compared with isocaloric carbohydrate or lower-quality protein alternatives [

38,

40]. Plant proteins, although sometimes limited in essential amino acids, provide benefits through unique mechanisms, such as anti-inflammatory bioactives and modulation of the gut microbiota [

23,

41]. Studies involving soy protein supplementation demonstrate enhanced insulin sensitivity, reduced LDL-cholesterol, and modest preservation of lean mass under hypocaloric diets [

23,

42].

Older adults represent a particularly high-risk group. Due to age-related anabolic resistance, they require larger protein doses per meal to maximize muscle protein synthesis. Evidence suggests that distributing protein evenly across meals and prioritizing leucine-rich sources helps maintain muscle mass and improve functional outcomes in this population [

43]. In this regard, dairy proteins offer advantages because of their high leucine content and rapid digestibility, while plant proteins may need fortification or combination strategies to achieve similar anabolic effects.

GLP-1–based treatments introduce additional complexity. Findings from the STEP trials indicate that semaglutide-induced weight loss is associated with substantial reductions in lean mass, accounting for as much as one-third of the total weight lost, which raises concerns about sarcopenic obesity once therapy is discontinued [

4,

5]. Although direct interventional studies remain limited, observational evidence suggests that maintaining sufficient protein intake during GLP-1 therapy may help preserve muscle mass and support metabolic resilience. Combining protein supplementation with resistance training has been recommended as a strategy to offset drug-related sarcopenia [

43].

Taken together, these clinical insights highlight that not only the amount but also the type and distribution of protein intake are critical for maintaining long-term weight reduction, preserving lean tissue, and preventing sarcopenic obesity. Future research should specifically examine how different protein sources interact with pharmacological weight loss interventions. This is especially important in older adults, where the overlap of obesity relapse and sarcopenic obesity significantly increases health risks and mortality.

6. Conclusions and Perspective

This mini-review emphasizes that protein quality is a critical factor in sustaining long-term weight management, with effects extending beyond overall intake to include source-specific influences on adipose remodeling, epigenetic regulation, and muscle preservation. Dairy proteins, particularly whey, provide a leucine-rich signal that stimulates muscle protein synthesis, while plant-based proteins supply anti-inflammatory compounds and microbiota-derived metabolites with epigenetic activity. Emerging options such as banana peel protein present sustainable alternatives with potential benefits for adipose tissue flexibility, although evidence in humans remains limited.

Weight regain is now increasingly understood as a biologically driven process maintained by persistent epigenetic “obesity memory” within adipose tissue. Protein-derived signals may help weaken or reinforce these epigenetic imprints, thereby shaping metabolic resilience. This issue is especially relevant in the context of GLP-1–based pharmacotherapy, where lean mass loss combined with rapid fat recovery raises the risk of sarcopenic obesity.

From a translational standpoint, older adults should be a primary focus, as they are particularly susceptible to anabolic resistance, frailty, and sarcopenic obesity. In such populations, protein interventions could provide dual benefits—preserving lean mass while reducing pro-obesogenic epigenetic marks. Clinical evidence supports protein intakes of 1.2–1.6 g/kg/day during calorie restriction for maintaining lean tissue, yet direct comparisons of different protein sources in older individuals undergoing GLP-1 therapy remain scarce. Future work should integrate dietary strategies with exercise and pharmacological approaches, testing high-leucine dairy proteins, fortified plant blends, and novel sustainable proteins in aging populations. Such translational approaches are essential to lower relapse risk, foster healthy aging, and address the growing challenge of sarcopenic obesity.

References

- Rubino, F.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.D.; Blüher, M.; Tschöp, M.H.; DiMarchi, R.D. Anti-obesity drug discovery: Advances and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, M.L.; Arterburn, D.E.; Van Scoyoc, L.; Smith, V.A.; Yancy WSJr Weidenbacher, H.J.; et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016, 151, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Davies, M.; et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: The STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022, 24, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S; et al. ; STEP 1 Study Group. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinte, L.C.; Castellano-Castillo, D.; Ghosh, A.; et al. Adipose tissue retains an epigenetic memory of obesity after weight loss. Nature. 2024, 636, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; et al. Epigenetic regulation of adipose tissue plasticity and weight regain. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Gavrilova, O.; Pack, S.; Jou, W.; Mullen, S.; Sumner, A.E.; et al. Hypertrophy and hyperplasia of adipocytes underlying obesity and its metabolic consequences. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasawa, T.; et al. GLP-1 analogues, lean mass reduction and sarcopenic obesity. Obesity. 2025, 33, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernecker, M.; et al. Weight cycling promotes hyperphagia and accelerates body weight regain in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2025, 17, eaax1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastaitis, J.W.; et al. Dual blockade of GDF8 and ActA during GLP-1RA-induced weight loss in obese mice preserves lean mass while also increasing fat loss. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.J.; et al. Discontinuation and reinitiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists among US adults with overweight or obesity. Diabetes Care. 2025, 48, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; et al. The impact of weight cycling on health and obesity. Front Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 13342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.P.; et al. Weight cycling as a risk factor for low muscle mass and strength and a greater likelihood of developing sarcopenic obesity. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, M.; Giani, A.; Fantin, F.; Rossi, A.P.; Mazzali, G.; Zoico, E. Weight cycling and its effects on muscle mass, sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Eglseer, D.; et al. Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenic obesity among older adults. Clin Nutr. 2025, 44, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzbashian, E.; et al. Plant proteins, gut microbiota, and obesity risk. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussar, S.; et al. Dairy proteins and metabolic health. Obesity. 2025, 33, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Lemmens, S.G.; Westerterp, K.R. Dietary protein—Its role in satiety, energetics, weight loss and health. Br J Nutr. 2012, 108, S105–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidy, H.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Astrup, A.; Wycherley, T.P.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Woods, S.C.; Mattes, R.D. The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015, 101, 1320S–1329S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.E.; Moore, D.R.; Kujbida, G.W.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Phillips, S.M. Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: Effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and after resistance exercise in young men. J Appl Physiol. 2009, 107, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.; Blanco Mejia, S.; Lytvyn, L.; Stewart, S.E.; Viguiliouk, E.; Ha, V.; Kendall, C.W.; Jenkins, D.J.; Leiter, L.A.; de Souza, R.J.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Effect of plant protein on blood lipids: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M. Soy and health update: Evaluation of the clinical and epidemiologic literature. Nutrients. 2016, 8, 754. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.P.; Vij, S. Inactive to bioactive: The transformation of peptides derived from dietary proteins to bioactive peptides. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018, 58, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho, F.G.; Ovidio, P.P.; Padovan, G.J.; Jordão Junior, A.A.; Marchini, J.S.; NavarroAM. Banana peel flour: Characterization and application in whole wheat cookies. J Food Sci Technol. 2017, 54, 2632–2639. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, M.; Wani, M.S.; Gani, A. Banana peel as a functional ingredient and its food applications: A review. Nutr Food Sci. 2021, 51, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Milagro, F.I.; Mansego, M.L.; De Miguel, C.; Martínez, J.A. Dietary factors, epigenetic modifications and obesity outcomes: Progresses in animal and human studies. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2013, 10, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Barja-Fernández, S.; et al. Epigenetics of weight regain after obesity treatment. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 30, 719–731. [Google Scholar]

- Rönn, T.; Volkov, P.; Davegårdh, C.; et al. A six months exercise intervention influences the genome-wide DNA methylation pattern in human adipose tissue. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D.; et al. Histone modifications in adipocytes and obesity. Curr Pharm Des. 2014, 20, 1646–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffstedt, J.; Andersson, D.P.; Eriksson Hogling, D.; Theorell, J.; Näslund, E.; Thorell, A.; Ehrlund, A.; Rydén, M.; Arner, P. Long-term protective changes in adipose tissue after gastric bypass. Diabetes Care. 2017, 40, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M. Food Proteins and Bioactive Peptides: New and Novel Sources, Characterisation Strategies and Applications. Foods. 2018, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; McKenzie, C.; Potamitis, M.; Thorburn, A.N.; Mackay, C.R.; Macia, L. The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Adv Immunol. 2014, 121, 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rubino, D.M.; Greenway, F.L.; Khalid, U.; O’Neil, P.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Sørrig, R.; et al. Effect of continued weekly subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo on weight loss maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: The STEP 4 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021, 325, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenholm, S.; Harris, T.B.; Rantanen, T.; Visser, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Ferrucci, L. Sarcopenic obesity: Definition, cause and consequences. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008, 11, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.B.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Macdonald, M.J.; Macdonald, J.R.; Armstrong, D.; Phillips, S.M. Consumption of fluid skim milk promotes greater muscle protein accretion after resistance exercise than soy protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007, 85, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frestedt, J.L.; Zenk, J.L.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Ward, L.S.; Bastian, E.D. A whey-protein supplement increases fat loss and spares lean muscle in obese subjects: A randomized human clinical study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Radavelli-Bagatini, S.; Hagger, M.; Ellis, V. Comparative effects of whey and casein proteins on satiety and food intake in overweight and obese individuals. Br J Nutr. 2014, 111, 659–667. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, J.; Noakes, M.; Trenerry, C.; Clifton, P.M. Energy intake, ghrelin, and cholecystokinin after different carbohydrate and protein preloads in overweight men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 91, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med. 2017, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.W.; Johnstone, B.M.; Cook-Newell, M.E. Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids. N Engl J Med. 1995, 333, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Biolo, G.; Cederholm, T.; Cesari, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Morley, J.E.; et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: A position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013, 14, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondanelli, M.; Nichetti, M.; Peroni, G.; Faliva, M.A.; Gasparri, C.; Infantino, V.; et al. Where to start? Muscle loss in obesity and the role of nutrition and exercise. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 2670. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).