1. Introduction

Titanium and its alloys are known for their exceptional combination of mechanical and bio-mechanical properties, such as high specific strength, remarkable corrosion resistance, hardness, fatigue resistance, and high-temperature resistance [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], accompanied by the notable biocompatibility [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] These impressive qualities make them suitable for high-performance applications like aerospace components, the automotive sector, the chemical industries, and biomedical implants [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Ti-6Al-4V is a well-known alpha-beta titanium alloy [

16]. Among all titanium alloys, it has become the most extensively used [

17], accounting for approximately 50% of the total global production of titanium and its alloys [

18]. It is primarily valued for its high strength, low density, corrosion resistance [

19], and biocompatibility, making it suitable for biomedical applications [

20,

21,

22] such as orthopedic [

23] and dental implants [

24,

25]. Additionally, its low thermal conductivity and high melting point make it ideal for the aerospace sector [

26,

27], including critical structural components, jet engine parts [

28], and landing gear elements [

29]. The stability of the above-mentioned properties and applications is due to its remarkable microstructure, which consists of an α+β dual phase [

30].

In recent decades, improving mechanical properties has become a significant focus of metallurgical research. Microstructural characteristics, like grain size, dislocation density, and phase composition, play a crucial role in enhancing mechanical properties [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Over the past few years, studies have increasingly centered on innovative methods for producing ultrafine grains (UFG) to enhance these mechanical traits [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. These UFG structures resulted in improved mechanical properties and corrosion resistance [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Several processing techniques have been incorporated into producing UFG in Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Sergueeva et al. [

46] performed high-pressure torsion (HPT) to develop UFG in Ti-6Al-4V alloy to achieve high-strain-rate superplasticity. Zherebtsov et al. [

47] demonstrated an increase in mechanical strength (25-40%) and fatigue resistance, along with a reduction in ductility, through the production of UFG in Ti-6Al-4V using the warm “abc” deformation method. Semenova et al. [

48], Saitova et al. [

49], Semenova et al. [

50], Ko et al. [

51] and Fernandes et al. [

52] produced UFG through severe plastic deformation (SPD) with the help of equal channel angular pressing (ECAP) process, resulting in enhanced mechanical strength and fatigue properties, enhanced superplastic deformation behaviour and surface properties (for biomedical applications), respectively. Pazhanivel et al. [

53] developed an ultra-fine bimodal structure using heat treatment of laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) produced Ti-6Al-4V. Li et al. [

54] demonstrated the enhancement of corrosion resistance by creating a nanograined layer through rapid multiple rotation rolling on the surface of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. The grain size achieved through these processes ranges from 500 nm to 10 μm.

Hailiang et al. [

55] demonstrated that the refinement of grain size correlates with the improvement of the second phase and an increase in dislocation density, thus contributing to superior mechanical properties. Kaixuan et al. [

56] examined the effects of cryogenic treatment. They clarified a reduction in the quantity of the β phase due to the transformation of metastable β into stable α and β phases. Furthermore, rolling at cryogenic temperatures has become a prominent technique for grain refinement, thereby enhancing the mechanical properties of titanium and its alloys [

57].

Cryogenic treatment, particularly cryo-rolling, has recently drawn attention and emerged as a prominent technique for grain refinement. It refines the grains up to the level of UFG and nanograins. The rolling at sub-zero temperature helps in the suppression of dynamic recovery and recrystallization, which results in the rise in dislocation density and the formation of sub-grains. Enhancement of mechanical properties through grain refinement and enhanced dislocation density via cryo-rolling of Ti-6Al-4V sheets. With the help of multiple cryogenic treatments, Kang et al. [

58] demonstrated the reduction of the β phase in Ti-6Al-4V alloy, resulting in increased dislocation density and microstrain, which led to increased compressive strength, failure strain, and wear resistance of the alloy. Gu et al. [

59] reported an increment in elongation accompanied by the strengthening of Ti-6Al-4V alloy, resulting from the reduction in precipitate particles after cryogenic treatment.

Despite extensive research conducted in recent years on Ti-6Al-4V for enhancing its properties, such as mechanical, chemical, thermal, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility for applications like aerospace industries and biomedical implants, cryogenic treatment remains relatively uncommon. Although a few studies have been undertaken to understand the influence of cryogenic rolling processes on the material’s mechanical properties and crystal structure behaviour, however, a significant research gap persists with respect to the evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties. This study aims to deepen the understanding of advanced material processing techniques and their potential impact on improving the performance of Ti-6Al-4V. The current investigation systematically explores the effects of cryogenic rolling at varying deformation percentages on the process-structure-property relationship of Ti-6Al-4V. A detailed microstructural analysis was conducted to identify phase morphology, deformation features, phase identification, crystallite size, and dislocation density. Furthermore, mechanical properties of the material were investigated through tensile tests and Vickers hardness measurements. A detailed correlation between microstructure and mechanical properties was established. Additionally, some preliminary work was conducted to examine the effect of post-heat treatment on cryo-rolled samples.

2. Materials and Methods

In the present study, a 10 mm thick Ti-6Al-4V (grade 5) plate, with the chemical composition outlined in

Table 1, was utilized. Chemical analysis was conducted to accurately determine alloy composition and correlate it with the ASTM B 265–20a standard. The elemental composition was determined using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), while gas analysis was performed using Laboratory Equipment Corporation (LECO) techniques. Fine chips were produced using a drilling machine operating at low speed for ICP-OES analysis, whereas pins measuring 4 mm in diameter and 10 mm in length were fabricated using a manual lathe machine for LECO analysis.

Multiple specimens, each measuring 100 mm x 40 mm x 10 mm, were sectioned from the plate using a bandsaw. Selected specimens were immersed in a liquid nitrogen bath at -196°C for 30 minutes. Subsequently, specimens soaked in a liquid nitrogen bath were subjected to unidirectional multiple pass rolling, employing varying percentages of deformation, ranging from 5% to 37.5% thickness reduction. The samples were re-soaked in liquid nitrogen for 10 minutes after every four passes to maintain processing at ambient temperature.

Specimens cryo-rolled at 15% and 30% were subjected to heat treatment in a Carbolite Gero tubular furnace maintained at 900 °C for a soaking duration of 30 minutes, followed by air cooling. The purpose of heat treatment was to relieve stress and induce recrystallization.

Specimens in their cryo-rolled and heat-treated conditions were characterized using optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The plane selected for characterization across all conditions was bound by the rolling and transverse directions, commonly referred to as the rolling surface or plane. Optical microscopy of the surfaces of both as-received and cryo-rolled specimens, as well as post-heat-treated specimens, was performed using a Leica DM 2500 M optical microscope. This analysis aimed to observe the microstructural changes resulting from cryo-rolling at different deformation percentages. SEM was conducted on the same conditioned samples using a Zeiss EVO 18 scanning electron microscope. SEM aimed to observe microstructural variations in depth at higher magnifications resulting from cryo-rolling at various deformation percentages and post-heat-treatment. The elemental distribution resulting from the effects of cryo-rolling at different deformation percentages was analyzed using EDS on cryo-rolled specimens with a Zeiss EVO 18 scanning electron microscope. EBSD and TEM of the selected samples were performed using a Hitachi Ultra-High-Resolution Schottky Scanning Electron Microscope (SU7000), equipped with a field-emission gun (FEG), and a JEOL-2100F transmission electron microscope, respectively, to identify the deformation mechanism. EBSD analysis was done on TSL OIM software version 8.1. XRD analysis of as-received and cryo-rolled specimens was conducted using a Rigaku Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer with a cobalt source (wavelength λ = 1.79 Å). Analysis was performed using PDXL-2 software to identify phases and ascertain their lattice parameters.

Mechanical testing included tensile and hardness tests. Uniaxial tensile test specimens were fabricated with the help of wire electrical discharge machining (EDM) in accordance with the ASTM E8 international standard. Subsequently, tensile testing was performed under each condition using an Instron Model 8501 universal testing machine, operating at a constant strain rate of 0.2 mm/min. Vickers hardness tests were conducted on small specimens measuring 20 mm in length and 15 mm in width, with the longer dimensions aligned parallel to the rolling direction (RD). Hardness measurements were taken using a Vickers VH-50MD hardness-testing machine, with indentations spaced 5 mm apart and a load of 30 Kgf applied for each indentation. These tests on the cryo-rolled specimens aimed to examine variations in mechanical properties, including strength, percentage elongation, and hardness, across different rolling percentages at sub-zero temperatures.

3. Results and Discussion

Elemental composition of Ti-6Al-4V alloy is presented in

Table 1, which represents the concentration of alloying constituents in weight percentage (wt.%) and gaseous elements in parts per million (ppm). The measured compositional parameters of the as-received alloy comply with the acceptable range defined within the ASTM B265–20a standard specification.

3.1. Microstructure Analysis

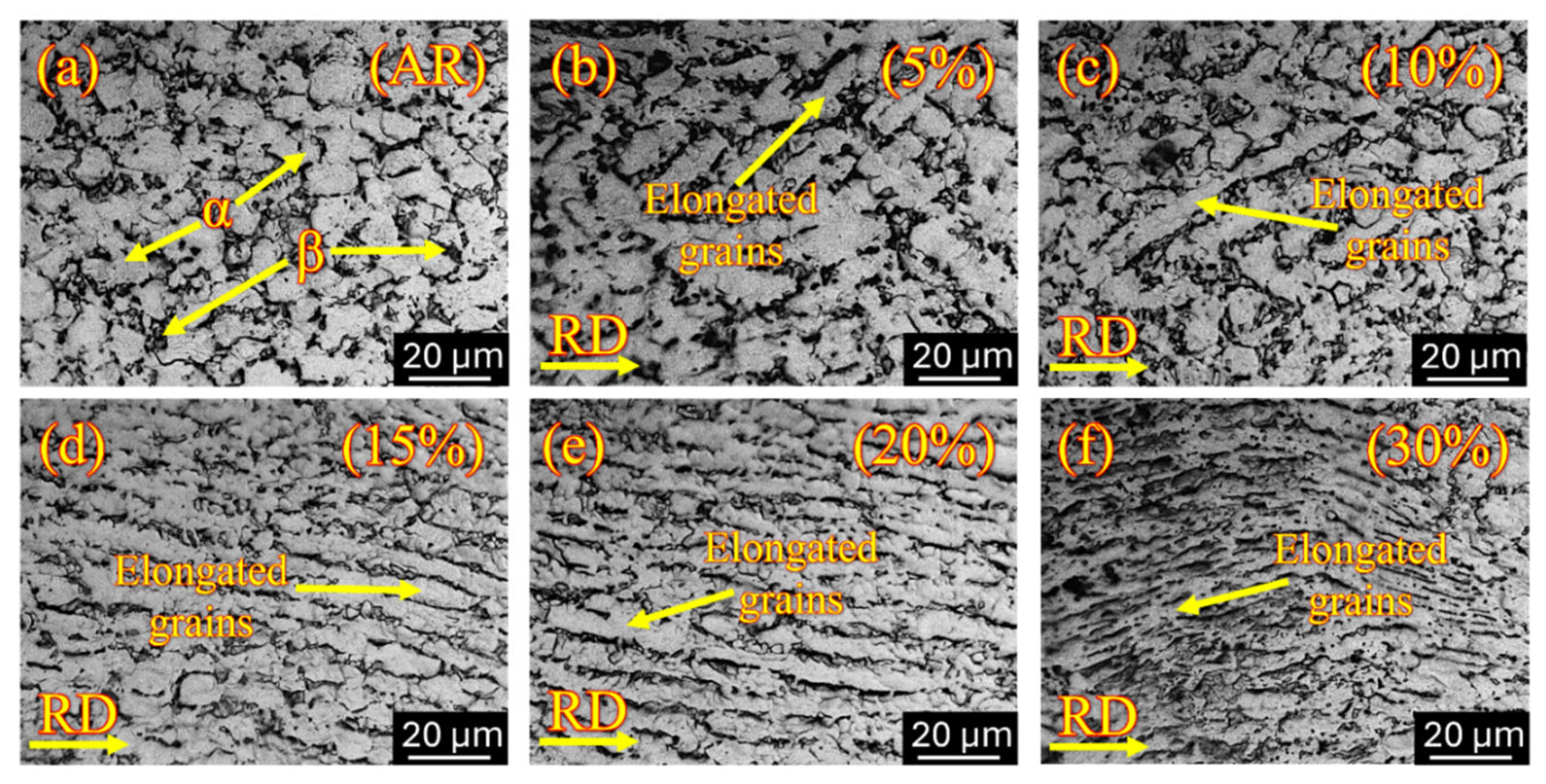

The microstructural evolution, along with the internal grain structural characteristics of cryo-rolled Ti-6Al-4V specimens subjected to various degrees of plastic deformation, was systematically examined using optical microscopy and SEM, as illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. As-received specimens exhibit a fine equiaxed structure of α-phase grains, characterized by an α+β dual-phase structure, as shown in

Figure 1a, with the β phase predominantly distributed along the grain boundaries of the α phase. This suggests that the specimen is initially in a mill-annealed condition [

60]. The measured grain size in as received condition is approximately 9.19 µm. In the optical micrographs and SEM images, α and β phases are distinguishable by their contrasting appearance. Bright and dark areas represent α and β phases, respectively, in optical microscopy, while the contrast is reversed in SEM images, where the β phase appears bright and the α phase appears dark. The initial microstructure of as-received specimen consists of prior α grains with an area fraction exceeding 95%, accompanied by a distribution of β phase at α grain boundaries, constituting a small fraction of less than 5%.

One of the key indicators of the cryo rolling process is ongoing grain refinement, which is proportional to the deformation percentage. Upon cryo-rolling, substantial grain refinement is observed, with slightly elongated grains aligned along the rolling direction, accompanied by deformation bands as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. These microstructural features become increasingly prominent as the rolling percentage increases, indicating a progressive accumulation of plastic strain. The shearing mechanism plays a crucial role in the elongation of α grains during cryogenic treatment by forming shear bands [

61]. At 5% cryo-rolling (Fig. 1b), the initiation of grain elongation takes place within the microstructure, complemented by the appearance of lamellar deformation bands. However, there is not much change in overall grain morphology. By increasing the percentage of deformation from 10% (Fig. 1c) to 15% (Fig. 1d), further elongation of grains occurs almost parallel to the rolling direction due to the presence of localized shearing [

62]. Further increasing the rolling percentage from 20% (Fig. 1e) to 30% (Fig. 1f) results in significantly elongated, well-defined grains, accompanied by densification of shear bands within the deformed structure. Due to the rolling in the cryogenic temperature regime, the recovery process is limited compared to that which occurs at ambient temperature [

63]. This results in the piling up of dislocations, which in turn helps with grain refinement. The combined effect of a reduction in dislocation mobility and limited annihilation of dislocations at cryogenic temperatures leads to a progressive increase in dislocation density [

64].

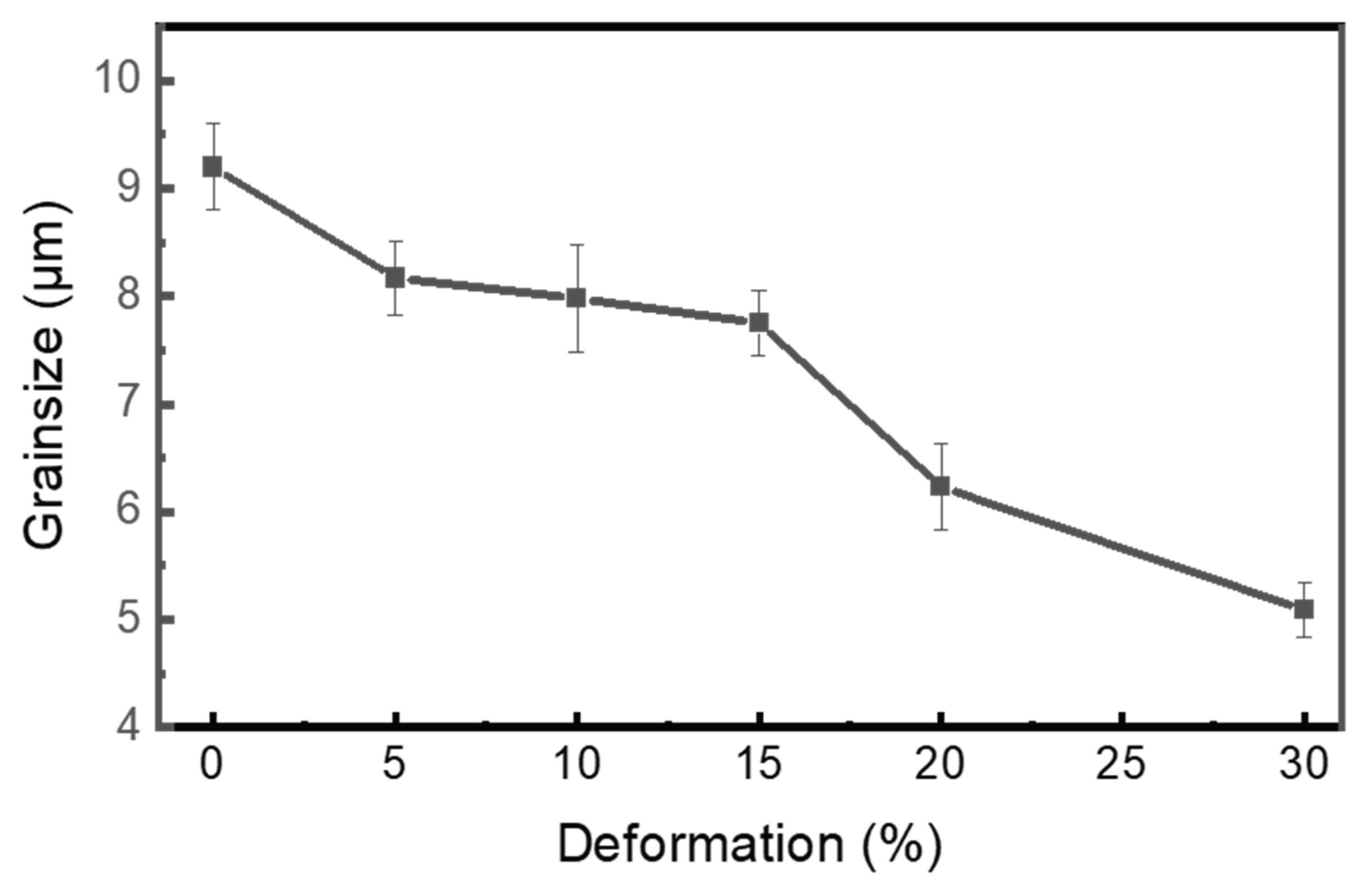

Figure 2 illustrates a quantitative analysis of grain size in relation to deformation percentage, showing a decreasing trend in grain size with increasing deformation percentage. The grain size decreases from approximately 9 µm in the as-received condition to around 5 µm at the 30% cryo-rolling condition, indicating progressive grain refinement with increasing thickness reduction. A continuous decrease in grain size results from strain accumulation caused by lattice defects during deformation at cryogenic temperatures, in the presence of liquid nitrogen, where the suppression of dynamic recovery and recrystallization occurs. Subsequently, dislocation accumulation takes place along with the formation of sub-grains, as shown in the highlighted zoomed section of

Figure 3(a, c, e, g, and i). Apart from dislocation accumulation, the formation of shear bands also plays a vital role in grain size reduction due to the rise in strain at high deformation percentages, which results from soft α and hard β phases present in the microstructure [

65]. A substantial reduction in grain size, achieved through cryo-rolling, is directly associated with improved mechanical performance.

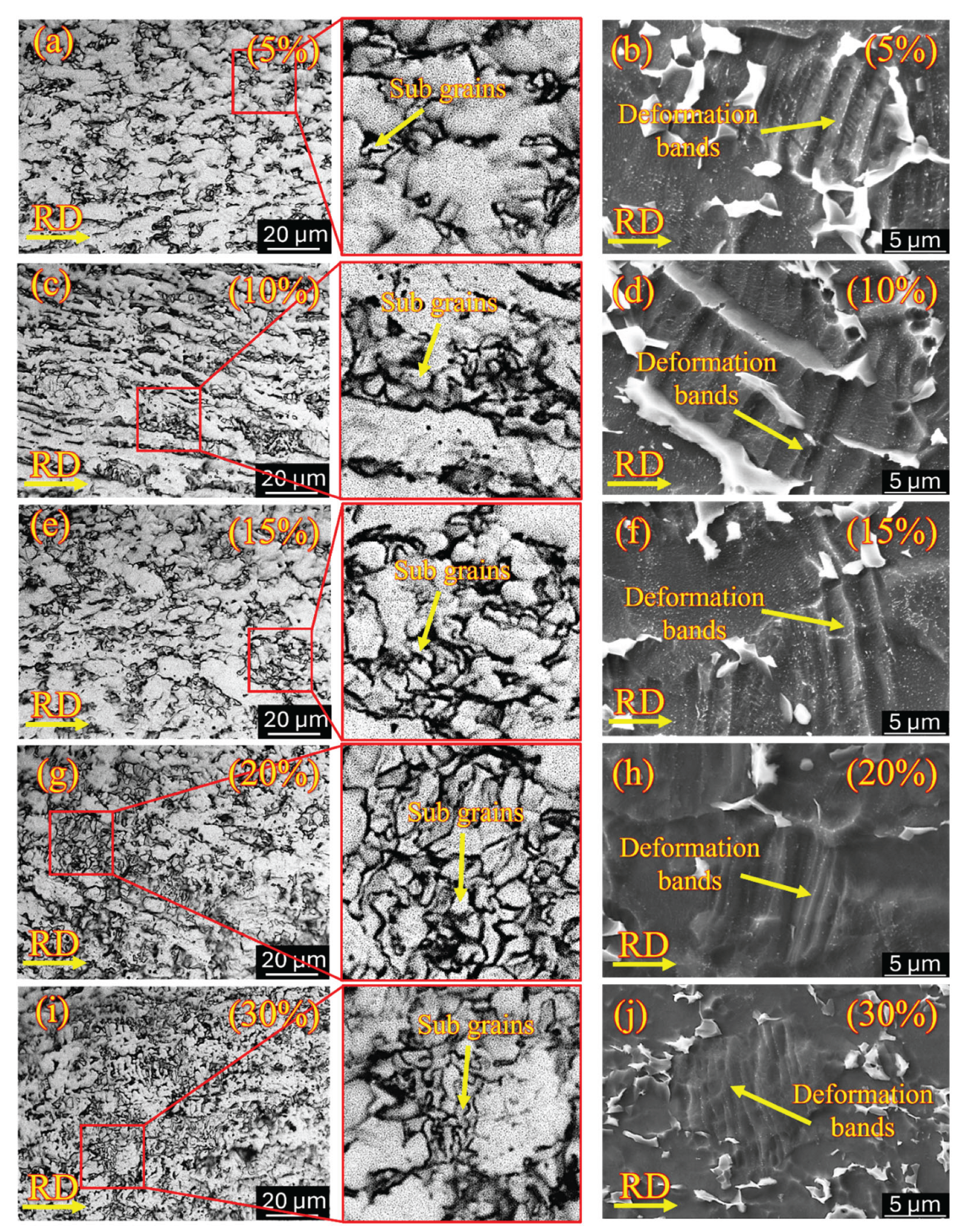

At deformation percentages from 5% (

Figure 3a-b) to 10% (

Figure 3c-d), the initiation of sub-grain formation takes place along with the development of localized deformation bands due to limited dislocation annihilation, which encourages dislocation reorganization into a lower energy configuration [

66,

67]. Increasing the percentage of deformation from 15% (

Figure 3e-f) to 20% (

Figure 3g-h), the progressive development of sub-grain structure takes place, resulting in the densification of deformation bands within the grains with high intensity. This densification of deformation bands is caused by the accumulation of plastic strain during an increase in thickness reduction [

68,

69]. These bands endorse the storage of dislocations, promoting the localized shearing mechanism [

70]. Finally, at 30% deformation (

Figure 3i-j), the microstructure tries to achieve an ultrafine grain morphology, promoting the formation of a highly dense sub-grain structure and an intricate network of deformation bands [

71]. The continuous recrystallization, along with the subsequent formation of sub-grain structure and densification of deformation bands with increasing rolling percentage, represents the correlation between microstructure evolution and strain accumulation during the cryo-rolling process of Ti-6Al-4V, which is essential for enhancing mechanical properties.

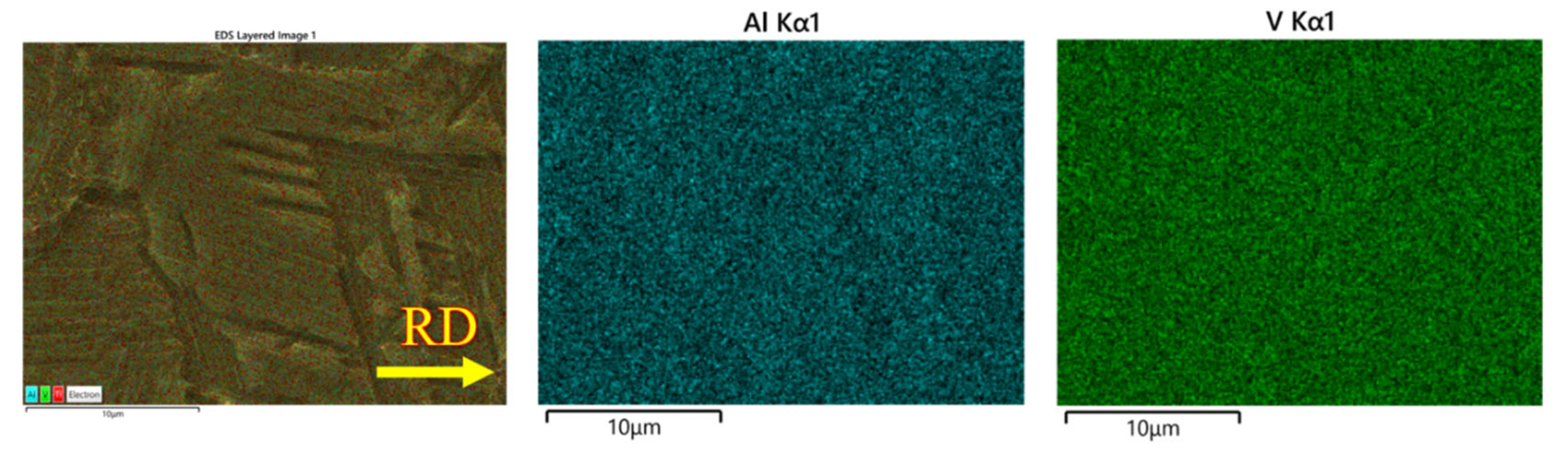

Elemental distribution across the specimen's surface, along with the phase composition of aluminium and vanadium, was analyzed using EDS on samples that were cryo-rolled as shown in

Figure 4(a-c).

Figure 4(d) represents a plot of elemental concentrations, indicating no significant changes in bulk elemental percentages resulting from cryo-rolling deformation. The retention of elemental consistency occurs because, during cryo-rolling, deformation is propagated through defect-induced mechanisms rather than diffusion-driven elemental redistribution. A notable increase in dislocation density, discussed in a later section, limits the elongation of β particles during deformation, leading to grain refinement and fragmentation of the β phase particles under cryo-rolled conditions.

3.2. Deformation Mechanism

To identify the deformation mechanism during the cryo rolling of Ti-6Al-4V, EBSD and TEM analyses were performed on samples with three different deformation percentages. The selection of the samples is based on low (10%), medium (20%), and high (30%) thickness reductions. The strain accumulation increases with the rolling percentage due to the cryogenic conditions. Rolling at such low temperature limits strain relief, as no heat is generated during deformation. Consequently, this restricts dislocation movement, leading to dislocation accumulation, grain refinement, fragmentation of β grains, and the formation of sub-grains. In Ti-6Al-4V, both twinning and dislocation slip contribute to deformation at cryogenic temperatures. Initial deformation at lower strains occurs primarily through twinning, which is dominant due to the limited number of slip systems. In comparison, dislocation slip becomes more significant at higher strains with the reduction in grain size. During the cryo rolling process, grain refinement is significantly achieved by the deformation twinning. At the same time, grain size plays an essential role in the tendency for the formation of twinning, with an inverse relationship [

72,

73,

74]. The deformation mechanism shifts from twinning to dislocation activity with the increase in deformation percentage [

75,

76] due to the refinement of grains and the continuous generation and multiplication of dislocations. This causes an increase in dislocation density, which inhibits twin propagation, and the formation of new twins becomes more complex, leading to a reduction in twin fraction.

For analysis of the activated twinning system during cryo rolling, the misorientation angle and the rotation axis related to each twinning system are derived from the EBSD results, as shown in

Table 2. They are consistent with findings reported in previous studies [

77,

78,

79,

80]. The EBSD and TEM analyses of the samples were performed along the rolling surface and are shown in

Figure 5. EBSD data include inverse pole figure (IPF) maps and misorientation angle distribution graphs, which display twins and their corresponding misorientation angles. Meanwhile, bright-field TEM micrographs reveal dislocation features. The presence of both tensile and compressive primary twins, along with secondary twins, has been observed in the IPF and verified through misorientation distribution graphs, accompanied by a coincident-site lattice (CSL) boundary ∑13a (~30°). When identical or different types of twins occur in one or multiple variants in the grain, they are termed primary twins. On the other hand, when a twin nucleates inside another pre-existing twin, they are known as secondary or double twins. The peak around 30º along the c-axis with the rotation axis [0001] has also appeared in several previous deformation studies of hexagonal close-packed (HCP) metals over the past several years [

81,

82,

83,

84]. The observed interface for this peak is not characterized as a twin boundary or a boundary separating twin variants [

85], so the cause behind its occurrence remains uncertain [

83,

86].

The presence of deformation twins has been significantly observed at a low strain of 10% deformation (

Figure 5a), indicating that at this low strain, deformation occurs predominantly through twinning. The fraction of tensile twins {10

2} <10

> occurs at the misorienting angle of around 86.7°, which is higher than that of compressive twins. This shows that at low deformation percentages, deformation takes place through the combination of both tensile and compressive twins, with tensile twins dominating the compressive twins, as shown in

Figure 5b. It indicates that the proportion of grains suitable for compressive twinning is lower than for tensile twinning. Also, the presence of secondary twins takes place at 44.4º. These wins are resulting from the nucleation of {10

2} <10

> type tensile twins within the {11

2} <11

> type compressive twins. These twins correspond to the rotation axis <1

43> [

78]. Additionally, the bright-field TEM micrograph shows a low-density dislocation zone (

Figure 5c). When the thickness reduction increases to 20%, grain fragmentation occurs, which restricts the formation of new twins and leads to twinning saturation [

87]. This saturation effect is visible as a reduction in the fraction of {10

2} <10

> tensile twins take place, while the fraction of compressive twins is increasing slightly, as shown in

Figure 5d and

5e. This indicates that with the increase in deformation percentage, compressive twins become more favourable. At the same time, the non-indexed points shown in black in

Figure 5d also increase, representing the increase in structural defects. As the twinning fraction decreases, densification of dislocation features such as dislocation pile-up, dislocation array, and dislocation tangle takes place, as shown in

Figure 5f. Further increase in rolling percentage to 30% enhances heterogeneity within the microstructure due to the presence of some coarse grains, further growth of non-indexed points signifies higher structural defect density, as shown in

Figure 5g. Along with a reduction in the fraction of both compressive as well as tensile twins (

Figure 5h), formation of high-density dislocations takes place within the material (

Figure 5i). Deformation mechanism transformed from twinning-induced mechanism to dislocation slip mechanism happened as the twinning becomes less energetically favourable with an increasing strain [

88].

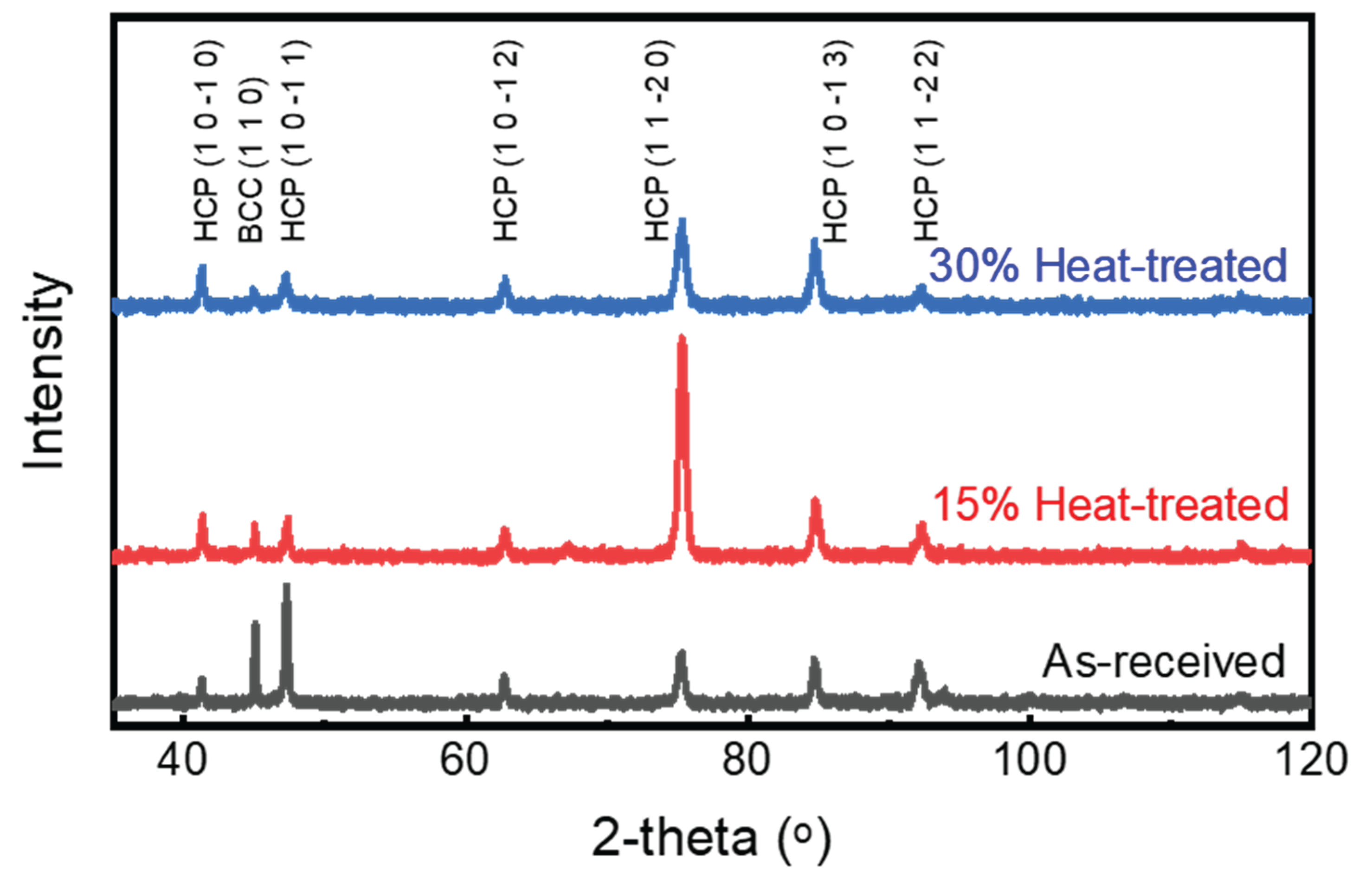

3.3. Phase Analysis After Cryo Rolling

The study of crystallographic evolution, lattice parameter changes, crystallite size, and dislocation density in Ti-6Al-4V subjected to cryo-rolling at different deformation percentages was performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The diffractograms for cryo-rolled samples are presented in

Figure 5. All peaks in these XRD patterns are exclusively indexed to the hexagonal close-packed (HCP) α and body-centered cubic (BCC) β phases of titanium, confirming the persistence of the alloy's dual-phase structure, showing the absence of any phase transformation induced in either condition. However, minute peak broadening and variations in relative peak intensity indicate that microstructural refinement and lattice strain accumulation have occurred due to cryo-rolling. This peak broadening mainly results from the combined effects of two interconnected mechanisms.

• A reduction in crystallite size, caused by the formation of dislocation cells, and

• An increase in microstrain, resulting from the increase in dislocation density, occurs during cryo-rolling processing.

These XRD results indicate an interlink between the piling up of dislocations and grain refinement resulting from cryo-rolling deformation, providing support for the enhancement in mechanical properties.

With the help of XRD diffractograms, the lattice parameters of both α and β phases of Ti-6Al-4V have been calculated using Bragg’s law (eq. 1) along with the crystallographic relationships between lattice parameters and interplanar spacing for HCP (eq. 2) and cubic (eq. 3) systems. The HCP α-phase exhibits a c/a ratio of about 1.59, while the BCC β-phase features a lattice constant of approximately a = 3.32 Å. Throughout the cryo-rolling process, no significant changes are observed, indicating that the chemical composition and phase stability of the alloy remain stable during processing. This consistency in the lattice parameter indicates the absence of solid solution redistribution and elemental partitioning during processing, suggesting that the microstructural evolution and enhancement in mechanical properties are driven by defect-induced mechanisms rather than changes in elemental concentration.

|

(Bragg’s Law) |

(eq. 1) |

|

(for HCP) |

(eq. 2) |

|

(for Cubic) |

(eq. 3) |

where, dhkl is the interplanar spacing (Å), 2θ is the Bragg’s diffraction angle (in degrees), λ is the wavelength used, and (a, b, c) and (h, k, l) are the lattice parameters and Miller indices, respectively.

3.3.1. Crystallite Size

Crystallite size was calculated with the help of Williamson–Hall (W–H) method (eq. 4), which deconvolutes peak broadening into contributions from crystallite size and microstrain using the following equation [

89,

90,

91,

92]:

where, β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) in radians, θ is the Bragg angle, k is the shape factor (typically 0.9), λ is the X-ray wavelength (1.79 Å for Co-Kα), D is the crystallite size, and ε is the lattice strain.

A reduction of around 28% in crystallite size is observed as the deformation percentage increases, as shown in

Figure 6. The average crystallite size is about 57 nm in the as-received condition, and it gradually decreases with an increase in rolling percentages, reaching approximately 40 nm at 30% cryo-rolling. This reduction results from the suppression of dynamic recovery at cryogenic temperatures, which leads to the annihilation of dislocation rearrangements [

93]. Consequently, dislocations accumulate or pile up within the grains, forming smaller coherent domains that decrease the crystallite size.

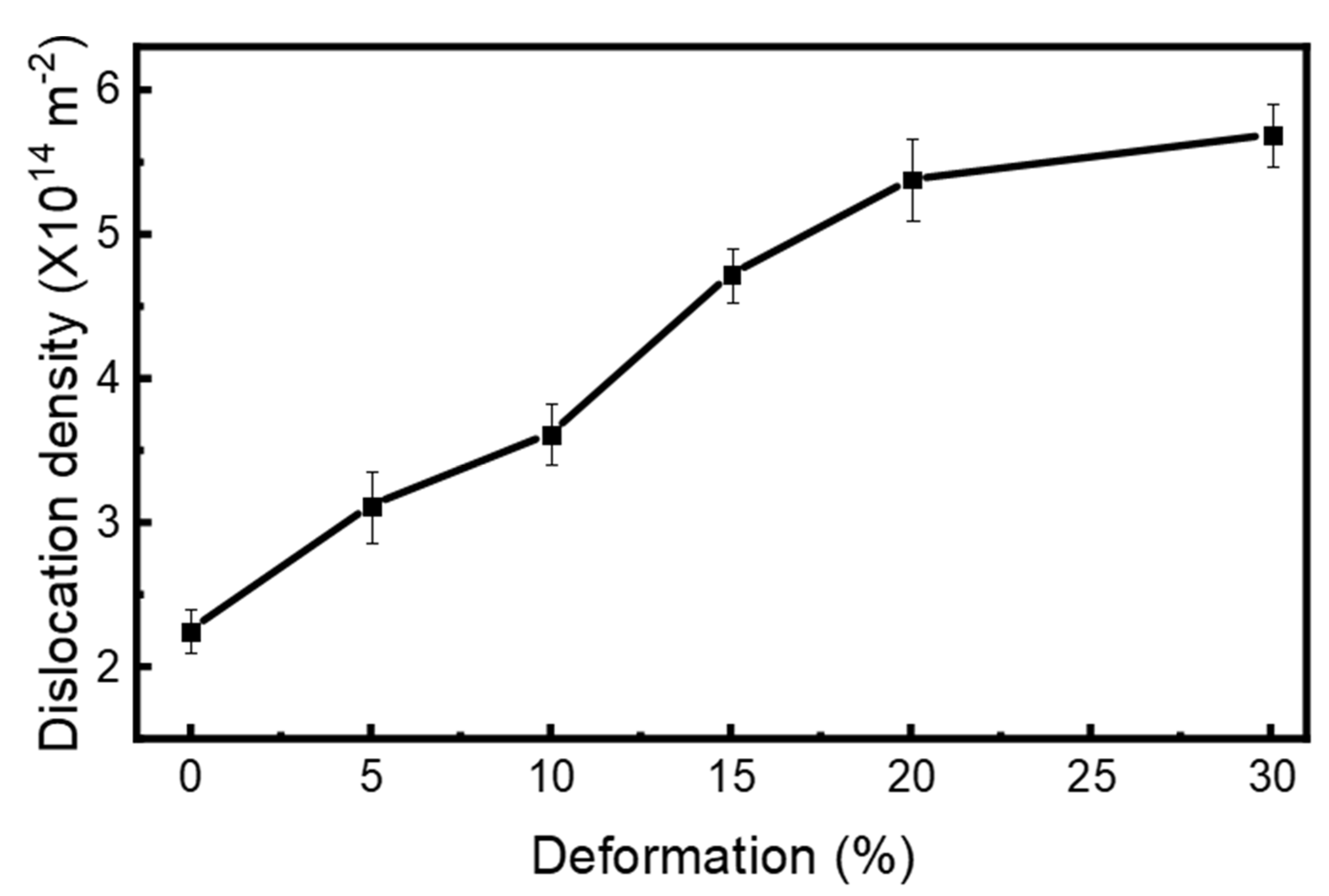

3.3.2. Dislocation Density

Dislocation density (

) was estimated for the total dislocations in a crystalline material by examining diffraction peak broadening. This approach relies on analysing the line broadening of XRD peaks, caused by the reduction in crystallite size and lattice strain that occurs during plastic deformation. The dislocation density (ρ) is subsequently calculated using the lattice strain (ε) and crystallite size (D) through the following equation [

94,

95].

where,

is the dislocation density (m⁻²), ε is the lattice strain (dimensionless), b is the Burgers vector (m), and D is the crystallite size (m).

With an increase in the percentage of deformation, a trend of increasing dislocation density is observed, as shown in

Figure 7. Dislocation density approximately increases from 2.26x1014 m-2 in the as-received condition to 5.69x1014 m-2 at the 30% cryo-rolling condition, representing nearly 152% enhancement in dislocation density. During plastic deformation at -196 °C, dislocation climb or cross-slip is restricted due to insufficient thermal energy, leading to the inhibition of dynamic recovery. Consequently, continuous generation and accumulation of dislocations occur rather than their annihilation. The observed increase in dislocation density directly contributes to strength enhancement [

96], which is also consistent with the Taylor hardening mechanism [

97].

3.4. Mechanical Properties Measurement

To examine the mechanical properties and elongation behaviour of Ti-6Al-4V alloy undergone different levels of cryo-rolling, uniaxial tensile and Vickers hardness tests were conducted on both as-received and cryo-rolled specimens at room temperature. This investigation aimed to evaluate the influence of cryo-rolling on the material's strength, ductility, and hardness. The outcomes of these tests are presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 and summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively.

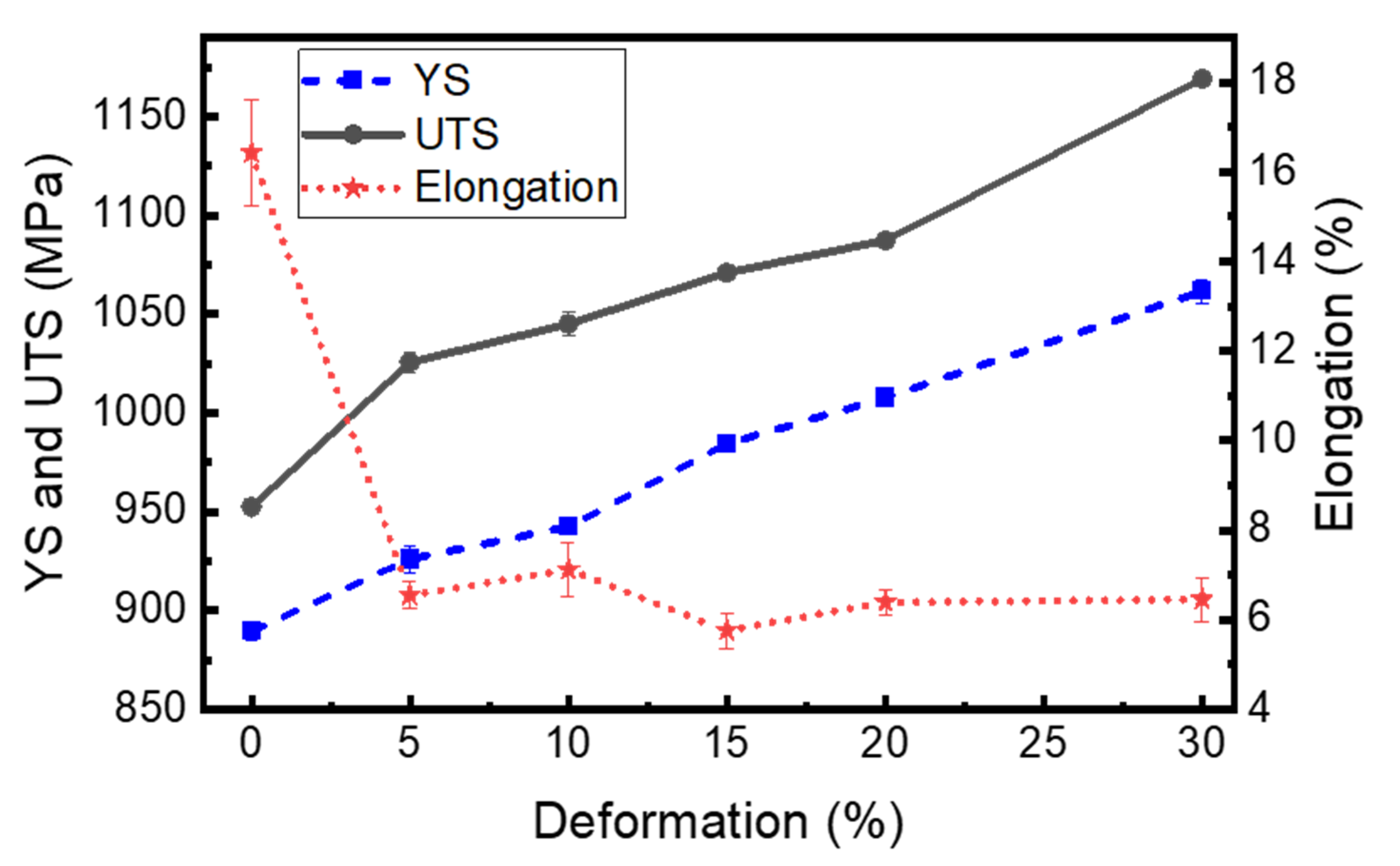

3.4.1. Tensile Properties

During the rolling process, the relationship between strength and ductility remains one of the most critical material aspects. Cryo rolling is a well-known method used to achieve ultrafine grains, resulting in high strength at the expense of ductility, as the plastic deformation process is governed by dislocation slip [

98].

Figure 8 quantitatively illustrates the relationship between yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), and percentage elongation for Ti-6Al-4V under various cryo-rolling deformation percentages, with corresponding numerical values listed in

Table 2. As-received sample exhibits a YS of 889.63 MPa, UTS of 952.65 MPa, and 16.43% ductility, confirming its mill-annealed condition for Ti-6Al-4V.

An increase in deformation percentage leads to significant strain hardening, as shown in

Figure 8, resulting in a corresponding increase in strength. In contrast, there is no appreciable change in the elongation percentage for cryo-rolled specimens. With rolling progress, a reduction in thickness occurs, accompanied by an increase in dislocation density, along with grain refinement and a decrease in crystallite size, resulting in the gradual increase in YS and UTS with decreasing thickness, reaching a maximum YS of 1061.66 MPa and a maximum UTS of 1169.10 MPa at 30% cryo-rolled deformation. Although there is a sudden drop in percentage elongation under cryo-rolling conditions, the effect on elongation percentage of cryo-rolled specimens is less consistent, as it shows a wavy nature, but remains more or less constant. Zhaoxin et al. [

99] and Xu et al. [

100] also observed a similar trend of ductility in their studies, with a constant increase in strength. This strength growth results from multiple factors contributing to deformation-induced strengthening mechanisms [

101,

102,

103,

104,

105].

• Twinning induced strengthening occurs at the early stages of deformation, followed by dislocation strengthening as dislocation density increases with an increasing percentage of cryogenic deformation.

• Grain boundary strengthening occurs through the Hall-Petch effect, which results from microstructural refinement and elongation of α grains, and

• Low processing temperature during cryo-rolling hinders dynamic recovery by causing high strain energy retention and stabilizing deformation structures.

Although twinning aids in refining grains and increasing strength, grain fragmentation causes twins to saturate in the early stages of deformation. As dislocation density rises, it suppresses the growth of twins, making it progressively more challenging to form new ones [

106]. During the initial stage of thickness reduction, the development of high-intensity twins contributes to the material's brittleness, resulting in a sudden decrease in percentage elongation. The percentage elongation reduced from 16.43% for the as-received specimen to nearly 6.5% under cryo-rolling conditions, with a thickness reduction from 5% to 30%. This indicates restricted dislocation mobility, grain refinement, and work hardening resulting from strain-induced deformation and the accumulation of internal stresses, which suppress further plastic deformation [

107,

108]. This effect is intensified by shear localization and deformation banding, as observed in SEM analysis, where concentrated stress into a narrow region promotes early failure and decreases uniform plastic deformation.

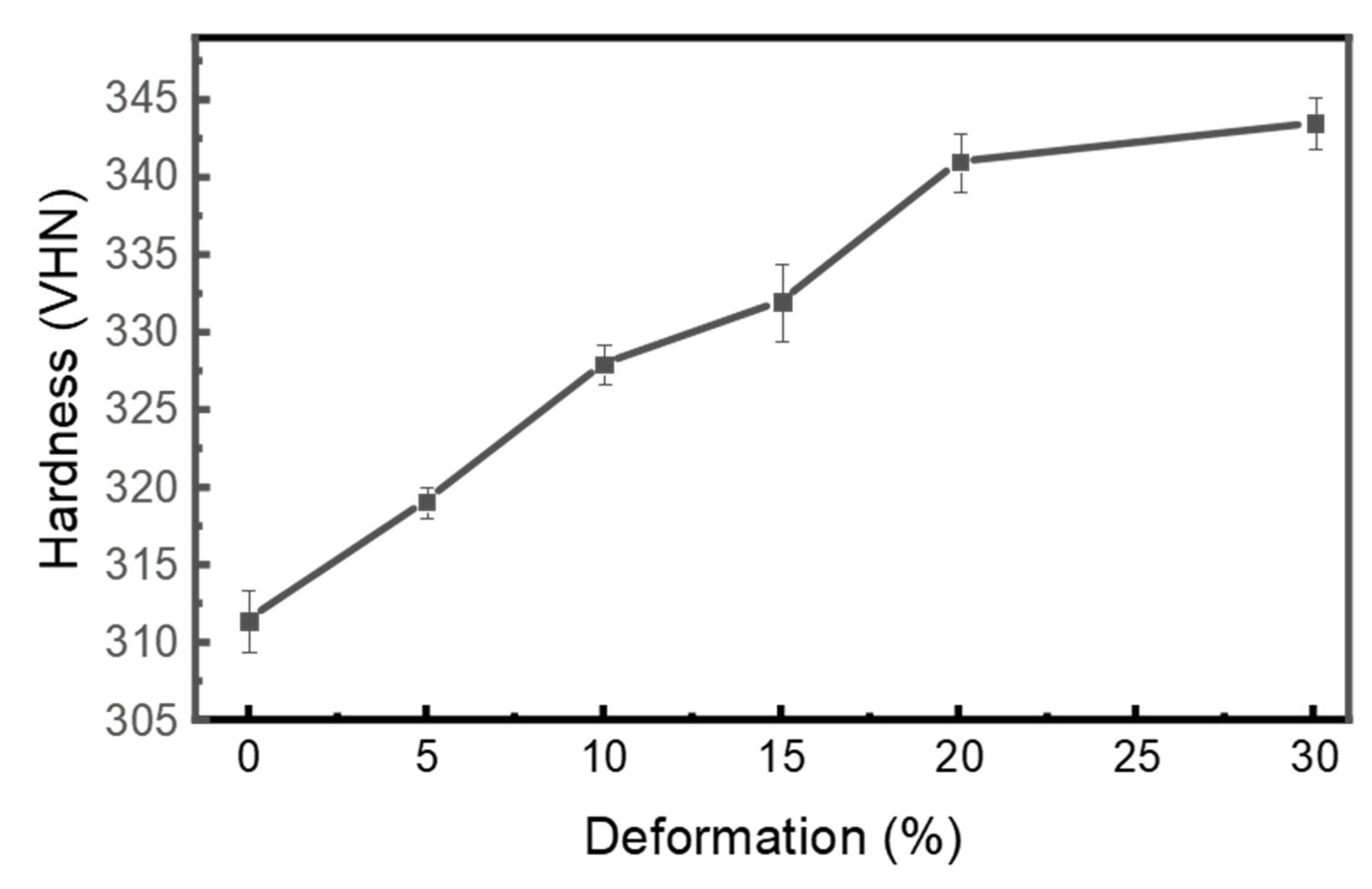

3.4.2. Hardness Behaviour

As shown in

Figure 9 and

Table 3, the Vickers hardness results exhibit a consistent increase in hardness with higher rolling percentages, from 311.5 vickers hardness number (VHN) in the as-received condition to 343.5 VHN after 30% cryo-rolled deformation, which aligns with the strength trend observed in the tensile test, resulting from dislocation pileup and grain refinement. It confirms that the enhancement of both localized and bulk plastic deformation takes place due to cryo-rolling [

109]. Fragmentation of the β-phase also plays a crucial role in the increasing trend of hardness with respect to the rise in deformation percentage [

110], as the finer β-phase promotes the pinning effect of dislocations, resulting in the tangling of dislocations, which restricts further deformation [

111]. The maximum hardness at 30% deformation is attributed to a fine crystallite size and high dislocation density, as indicated by XRD analysis.

Table 4.

Hardness of as-received (AR), cryo-rolled and heat-treated (HT) specimens.

Table 4.

Hardness of as-received (AR), cryo-rolled and heat-treated (HT) specimens.

| Hardness |

AR |

5% |

10% |

15% |

20% |

30% |

| VHN |

311.5

±2 |

319.17

±1 |

328

±1.3 |

332

±2.5 |

341

±1.9 |

343.5

±1.7 |

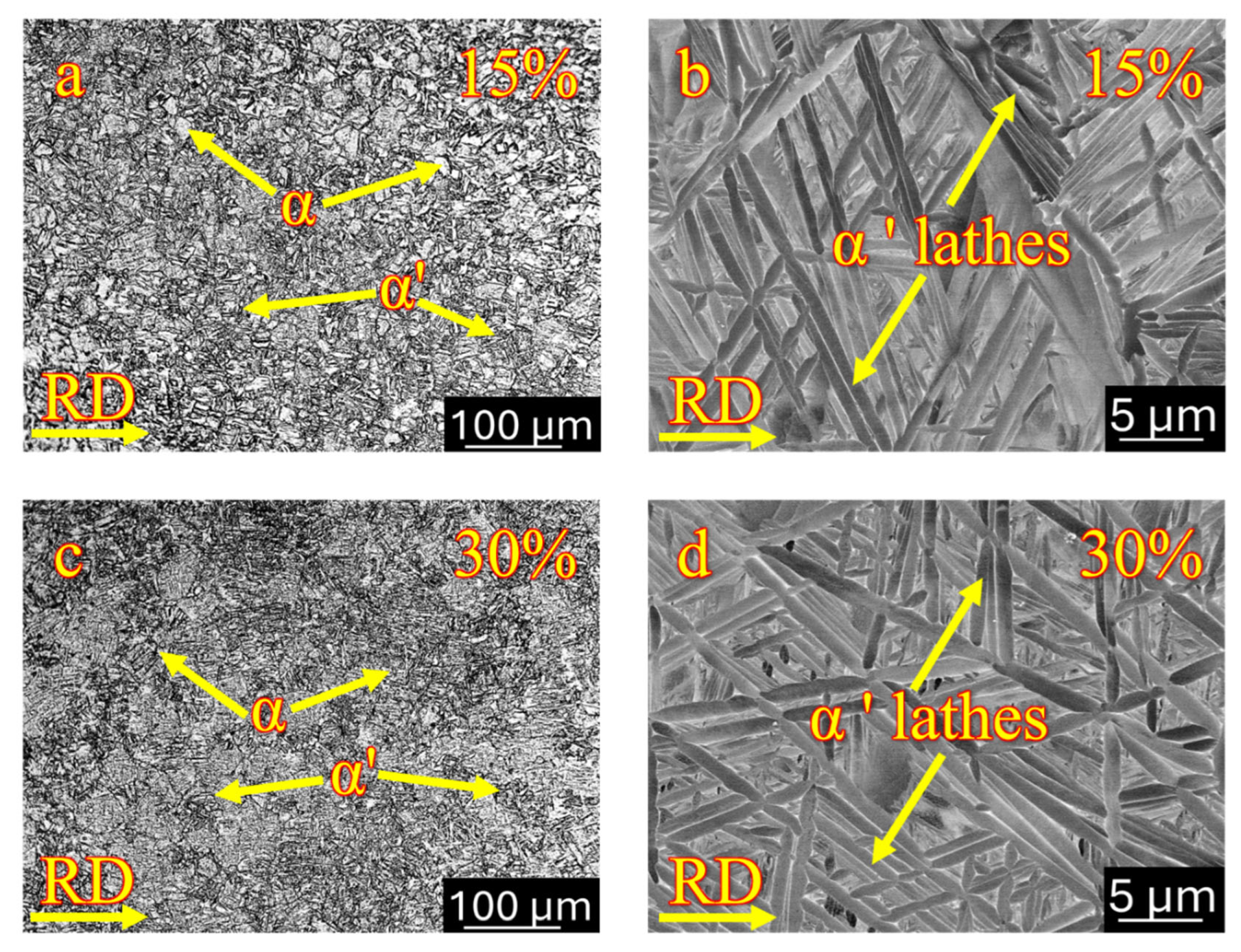

3.5. Effect of Post-Heat Treatment on Cryo Rolling

Two specimens were selected for the post-heat-treatment process based on the medium (15%) and the highest (30%) deformation percentages. Cryo-rolled samples, followed by heat treatments at 15% and 30% thickness reduction, display a duplex microstructure as shown in

Figure 10a (15% cryo-rolled followed by heat treatment) and 10c (30% cryo-rolled followed by heat treatment). The formation of a duplex microstructure takes place due to partial recovery and recrystallisation resulting from post-deformation thermal exposure. A slight difference is observed between heat-treated and as-received samples, with heat-treated samples exhibiting marginally coarser grains than non-heat-treated ones. The average grain size is approximately 8 µm and 7 µm at the equivalent deformation percentages of 15% and 30% post-heat-treated conditions, respectively. Along with the grain coarsening, partial recovery and recrystallisation aid in eliminating deformation bands and rolling-induced grain elongation. This occurs due to the initiation of static recrystallization and grain growth during heat treatment. The elimination of the fragmented structure occurs through the nucleation of strain-free grains. A significant reduction in internal stresses and defects occurs during the soaking period at elevated temperatures, due to the stabilization of microstructures caused by partial recovery and recrystallization. The evolution of the final microstructure is strongly influenced by the cooling rate employed during the heat treatment, which plays a crucial role in the phase transformation mechanism. Cooling at room temperature provides sufficient time for the secondary α (α') to nucleate and grow within the β matrix, resulting in the formation of a bimodal structure [

112]. Nucleation of the secondary α begins preferentially at the grain boundary, with growth progressing into the β matrix in the form of a lamellar structure, as shown in

Figure 10b (15% cryo-rolled followed by heat treatment) and 10d (30% cryo-rolled followed by heat treatment).

Elemental distribution across the specimen’s surface for the post-heat-treated condition exhibits no signature of any phase segregation, as shown in

Figure 11, attributed to recrystallization. Deformation-induced microstructural heterogeneity is effectively counteracted by the recrystallization process, resulting in homogeneity in microstructure by ensuring a uniform distribution of both α and β phases throughout the microstructure, a finding confirmed by optical and SEM microscopy analysis. Along with the surface and subsurface characteristics, bulk analysis was performed using XRD for phase identification during post-heat-treatment processing. The diffractograms for 15% and 30% post-heat-treated samples are shown in

Figure 12, along with the as-received condition. These results are similar to those obtained under cryo-rolled conditions, indicating no change in the chemical composition or phase stability. This demonstrates that the processing did not induce elemental partitioning or the redistribution of solid solutions.

Figure 13.

XRD plot of as-received and post-heat-treated (HT) specimens represents the α and β phases in Ti-6Al-4V.

Figure 13.

XRD plot of as-received and post-heat-treated (HT) specimens represents the α and β phases in Ti-6Al-4V.

In post-heat-treated conditions, hardness decreases for both 15% (317.5 VHN) and 30% deformation (319.5 VHN) with respect to their respective non-heat-treated conditions. This reduction is attributed to the recovery and recrystallization process, which promotes dislocation rearrangement and annihilation, thereby releasing stored strain energy and contributing to material softening by lowering lattice strain. Although the hardness decreases, it remains higher than in the as-received condition (311.5 VHN), indicating that partial retention of strain-hardened microstructures persists within the material.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the impact of cryogenic rolling on the microstructure evolution of Ti-6al-4v, including its deformation mechanism and mechanical properties. These analysis results in the following conclusions:

Rolling at liquid nitrogen temperature suppressed dynamic recovery, enhancing dislocation density and subsequently grain refinement takes place. The results obtained from the optical microscopy, SEM and EDS analysis show an intensification in elongated grains, reduction in grain size, sub-grain formation, densification of deformation bands and fragmentation of β grains with the increase in rolling percentage.

Due to the limitations of slip systems, at lower strain, initiation of deformation takes place via twinning. As the strain increases with an increase in thickness reduction, twinning becomes less favourable, and the formation of new twins becomes increasingly difficult. Twinning-induced deformation transforms into deformation via dislocation slip, with the formation of high-density dislocations.

The presence of α (HCP) and β (BCC) phases has been verified through XRD. There is no phase transformation or formation of any metastable phases that take place during cryo-rolling. With increasing strain, a slight peak broadening and intensity changes have been identified due to the microstructural refinement. William-Hall analysis is used to quantify the reduction in crystallite size and enhancement in dislocation density due to strain hardening with increasing rolling percentage.

Enhancement of the mechanical properties like YS, UTS and hardness has been observed via tensile and hardness tests, respectively, with increasing deformation percentage, while the ductility corresponding to all the cryo-rolled samples remains relatively stable, resulting from limited dislocation movement and higher internal strain energy.

During heat treatment following cryo-rolling, partial recovery and recrystallization facilitate the formation of a duplex microstructure and the removal of internal stains, leading to grain coarsening, homogeneous distribution of α and β phases throughout the microstructure and a reduction in the material's hardness.

The relationship between microstructure evolution, deformation mechanisms, and mechanical properties demonstrates the effect of cryo-rolling on modifying grain boundaries and dislocations in Ti-6Al-4V. These findings resemble a strong bond between the structure, property and performance, signifying the role of deformation mechanisms in the enhancement of mechanical properties during cryo rolling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G. and B.RK.; methodology, V.G. and B.RK.; formal analysis, V.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.G.; writing—review and editing, B.K.S, R.D, B.RK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Distinguished Professor Ma Qian, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Australia, for giving his valuable guidance and support in the analysis of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UFG |

Ultrafine grains |

| HPT |

High-pressure torsion |

| SPD |

Severe plastic deformation |

| ECAP |

Equal channel angular pressing |

| LPBF |

Laser powder bed fusion |

| ICP-OES |

Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry |

| LECO |

Laboratory Equipment Corporation |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDS |

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| EBSD |

Electron backscattered diffraction |

| TEM |

Transmission electron microscopy |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| FEG |

Field-emission gun |

| EDM |

Electrical discharge machining |

| RD |

Rolling direction |

| PPM |

Parts per million |

| AR |

As received |

| HT |

Heat-treated |

| IPF |

Inverse pole figure |

| CSL |

Coincident-site lattice |

| HCP |

Hexagonal close-packed |

| BCC |

Body-centered cubic |

| WH |

Williamson hall |

| FWHM |

Full width at half maximum |

| YS |

Yield strength |

| UTS |

Ultimate tensile strength |

| VHN |

Vickers hardness number |

References

- A. Gloria, R. Montanari, M. Richetta, A. Varone, Alloys for aeronautic applications: State of the art and perspectives, Metals 9(6) (2019) 662. [CrossRef]

- P. Traverso, E. Canepa, A review of studies on corrosion of metals and alloys in deep-sea environment, Ocean Engineering 87 (2014) 10-15. [CrossRef]

- K.O. Babaremu, J. Tien-Chien, P.O. Oladijo, E.T. Akinlabi, Mechanical, corrosion resistance properties and various applications of titanium and its alloys: a review, Revue des Composites et des Matériaux Avancés 32(1) (2022) 11. [CrossRef]

- H.Y. Ma, J. Wang, P. Qin, Y. Liu, L. Chen, L. Wang, L. Zhang, Advances in additively manufactured titanium alloys by powder bed fusion and directed energy deposition: Microstructure, defects, and mechanical behavior, Journal of Materials Science & Technology 183 (2024) 32-62. [CrossRef]

- G. Welsch, R. Boyer, E. Collings, Materials properties handbook: titanium alloys, ASM international1993.

- T.R. Rautray, R. Narayanan, K.-H. Kim, Ion implantation of titanium based biomaterials, Progress in Materials Science 56(8) (2011) 1137-1177. [CrossRef]

- L.C. Zhang, L.Y. Chen, A review on biomedical titanium alloys: recent progress and prospect, Advanced engineering materials 21(4) (2019) 1801215. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kirmanidou, M. Sidira, M.-E. Drosou, V. Bennani, A. Bakopoulou, A. Tsouknidas, N. Michailidis, K. Michalakis, New Ti-alloys and surface modifications to improve the mechanical properties and the biological response to orthopedic and dental implants: A review, BioMed research international 2016(1) (2016) 2908570. [CrossRef]

- M. Niinomi, Mechanical biocompatibilities of titanium alloys for biomedical applications, Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials 1(1) (2008) 30-42. [CrossRef]

- M. Kaur, K. Singh, Review on titanium and titanium based alloys as biomaterials for orthopaedic applications, Materials Science and Engineering: C 102 (2019) 844-862. [CrossRef]

- Y. Murakami, Metal fatigue: effects of small defects and nonmetallic inclusions, Academic Press2019.

- W. Sha, S. Malinov, Titanium alloys: modelling of microstructure, properties and applications, Elsevier2009.

- P. Majumdar, S. Singh, M. Chakraborty, Wear response of heat-treated Ti–13Zr–13Nb alloy in dry condition and simulated body fluid, Wear 264(11-12) (2008) 1015-1025.

- H. Wu, X. Chen, L. Kong, P. Liu, Mechanical and Biological Properties of Titanium and Its Alloys for Oral Implant with Preparation Techniques: A Review, Materials 16(21) (2023) 6860. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Khorasani, M. Goldberg, E.H. Doeven, G. Littlefair, Titanium in biomedical applications—properties and fabrication: a review, Journal of biomaterials and tissue engineering 5(8) (2015) 593-619. [CrossRef]

- F. Froes, Titanium: physical metallurgy, processing, and applications, ASM international2015.

- G. Lütjering, J.C. Williams, Titanium matrix composites, Titanium, Springer2007, pp. 313-328.

- E. Collings, The physical metallurgy of titanium alloys, Metals Park Ohio 3 (1984).

- P. Pushp, S. Dasharath, C. Arati, Classification and applications of titanium and its alloys, Materials Today: Proceedings 54 (2022) 537-542. [CrossRef]

- C. Veiga, J.P. Davim, A. Loureiro, Properties and applications of titanium alloys: a brief review, Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci 32(2) (2012) 133-148.

- H.-D. Jung, Titanium and its alloys for biomedical applications, MDPI, 2021, p. 1945.

- E. Marin, A. Lanzutti, Biomedical applications of titanium alloys: a comprehensive review, Materials 17(1) (2023) 114. [CrossRef]

- W. Abd-Elaziem, M.A. Darwish, A. Hamada, W.M. Daoush, Titanium-Based alloys and composites for orthopedic implants Applications: A comprehensive review, Materials & Design 241 (2024) 112850. [CrossRef]

- C. Oldani, A. Dominguez, Titanium as a Biomaterial for Implants, Recent advances in arthroplasty 218 (2012) 149-162.

- H.A. Alaraby, M. Lswalhia, T. Ahmed, A study of mechanical properties of titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V used as dental implant material, International Journal of Scientific Reports 3(11) (2017) 288-291. [CrossRef]

- R. Pederson, Microstructure and phase transformation of Ti-6Al-4V, Luleå tekniska universitet, 2002.

- M. Peters, J. Kumpfert, C.H. Ward, C. Leyens, Titanium alloys for aerospace applications, Advanced Engineering Materials 5(6) (2003) 419-427. [CrossRef]

- R. Ritchie, B. Boyce, J. Campbell, O. Roder, A. Thompson, W. Milligan, Thresholds for high-cycle fatigue in a turbine engine Ti–6Al–4V alloy, International Journal of Fatigue 21(7) (1999) 653-662.

- J.A. Francis, Titanium, Materials Science and Technology 35(3) (2019) 247-247.

- M.J. Donachie, Titanium: a technical guide, ASM international2000.

- X.-n. Peng, H.-z. Guo, Z.-f. Shi, C. Qin, Z.-l. Zhao, Microstructure characterization and mechanical properties of TC4-DT titanium alloy after thermomechanical treatment, Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 24(3) (2014) 682-689. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, M. Li, Nanocrystallization mechanism of beta phase in Ti-6Al-4V subjected to severe plastic deformation, Materials Science and Engineering: A 669 (2016) 7-13. [CrossRef]

- L. Niu, S. Wang, C. Chen, S.F. Qian, R. Liu, H. Li, B. Liao, Z.H. Zhong, P. Lu, M.P. Wang, P. Li, Y.C. Wu, L.F. Cao, Mechanical behavior and deformation mechanism of commercial pure titanium foils, Materials Science and Engineering: A 707 (2017) 435-442. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, Y. Sun, E.J. Lavernia, A. Shan, Mechanical Behavior of Ultrafine-Grained Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Produced by Severe Warm Rolling: The Influence of Starting Microstructure and Reduction Ratio, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 46(11) (2015) 5047-5057. [CrossRef]

- L. Saitova, H. Höppel, M. Göken, I. Semenova, G. Raab, R. Valiev, Fatigue behavior of ultrafine-grained Ti–6Al–4V ‘ELI’alloy for medical applications, Materials Science and Engineering: A 503(1-2) (2009) 145-147.

- I.P. Semenova, K.S. Selivanov, R.R. Valiev, I.M. Modina, M.K. Smyslova, A.V. Polyakov, T.G. Langdon, Enhanced Creep Resistance of an Ultrafine-Grained Ti–6Al–4V Alloy with Modified Surface by Ion Implantation and (Ti+ V) N Coating, Advanced Engineering Materials 22(10) (2020) 1901219.

- H. Shahmir, F. Naghdi, P.H.R. Pereira, Y. Huang, T.G. Langdon, Factors influencing superplasticity in the Ti-6Al-4V alloy processed by high-pressure torsion, Materials Science and Engineering: A 718 (2018) 198-206. [CrossRef]

- H. Shahmir, T.G. Langdon, Using heat treatments, high-pressure torsion and post-deformation annealing to optimize the properties of Ti-6Al-4V alloys, Acta Materialia 141 (2017) 419-426. [CrossRef]

- A.V. Sergueeva, V.V. Stolyarov, R.Z. Valiev, A.K. Mukherjee, Advanced mechanical properties of pure titanium with ultrafine grained structure, Scripta Materialia 45(7) (2001) 747-752. [CrossRef]

- Y. Iwahashi, Z. Horita, M. Nemoto, T.G. Langdon, The process of grain refinement in equal-channel angular pressing, Acta Materialia 46(9) (1998) 3317-3331. [CrossRef]

- K. Nakashima, Z. Horita, M. Nemoto, T.G. Langdon, Influence of channel angle on the development of ultrafine grains in equal-channel angular pressing, Acta Materialia 46(5) (1998) 1589-1599.s. [CrossRef]

- [V.V. Stolyarov, Y.T. Zhu, T.C. Lowe, R.Z. Valiev, Microstructure and properties of pure Ti processed by ECAP and cold extrusion, Materials Science and Engineering: A 303(1) (2001) 82-89. [CrossRef]

- R.Z. Valiev, R.K. Islamgaliev, I.V. Alexandrov, Bulk nanostructured materials from severe plastic deformation, Progress in Materials Science 45(2) (2000) 103-189. [CrossRef]

- V.V. Stolyarov, Y.T. Zhu, T.C. Lowe, R.Z. Valiev, Microstructures and properties of ultrafine-grained pure titanium processed by equal-channel angular pressing and cold deformation, Journal of nanoscience and nanotechnology 1(2) (2001) 237-242. [CrossRef]

- V.V. Stolyarov, Y.T. Zhu, I.V. Alexandrov, T.C. Lowe, R.Z. Valiev, Grain refinement and properties of pure Ti processed by warm ECAP and cold rolling, Materials Science and Engineering: A 343(1) (2003) 43-50. [CrossRef]

- A.V. Sergueeva, V.V. Stolyarov, R.Z. Valiev, A.K. Mukherjee, Enhanced superplasticity in a Ti-6Al-4V alloy processed by severe plastic deformation, Scripta Materialia 43(9) (2000) 819-824. [CrossRef]

- S.V. Zherebtsov, S. Kostjuchenko, E.A. Kudryavtsev, S. Malysheva, M.A. Murzinova, G.A. Salishchev, Mechanical Properties of Ultrafine Grained Two-Phase Titanium Alloy Produced by “abc” Deformation, Materials Science Forum, Trans Tech Publ, 2012, pp. 1859-1863. [CrossRef]

- Semenova, R. Valiev, E. Yakushina, G. Salimgareeva, T. Lowe, Strength and fatigue properties enhancement in ultrafine-grained Ti produced by severe plastic deformation, Journal of Materials Science 43(23) (2008) 7354-7359. [CrossRef]

- L. Saitova, I. Semenova, H. Höppel, R. Valiev, M. Göken, Enhanced superplastic deformation behavior of ultrafine-grained Ti-6Al-4V alloy, Materialwissenschaft und Werkstofftechnik: Entwicklung, Fertigung, Prüfung, Eigenschaften und Anwendungen technischer Werkstoffe 39(4-5) (2008) 367-370.

- Semenova, G. Raab, L. Saitova, R. Valiev, The effect of equal-channel angular pressing on the structure and mechanical behavior of Ti–6Al–4V alloy, Materials Science and Engineering: A 387 (2004) 805-808. [CrossRef]

- Y.G. Ko, W.S. Jung, D.H. Shin, C.S. Lee, Effects of temperature and initial microstructure on the equal channel angular pressing of Ti–6Al–4V alloy, Scripta Materialia 48(2) (2003) 197-202. [CrossRef]

- D.J. Fernandes, C.N. Elias, R.Z. Valiev, Properties and performance of ultrafine grained titanium for biomedical applications, Materials Research 18(6) (2015) 1163-1175. [CrossRef]

- B. Pazhanivel, P. Sathiya, G. Sozhan, Ultra-fine bimodal (α+ β) microstructure induced mechanical strength and corrosion resistance of Ti-6Al-4V alloy produced via laser powder bed fusion process, Optics & Laser Technology 125 (2020) 106017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, K. Sun, P. Liu, Y. Liu, P. Chui, Surface nanocrystallization induced by fast multiple rotation rolling on Ti-6Al-4V and its effect on microstructure and properties, Vacuum 101 (2014) 102-106. [CrossRef]

- H. Yu, M. Yan, J. Li, A. Godbole, C. Lu, K. Tieu, H. Li, C. Kong, Mechanical properties and microstructure of a Ti-6Al-4V alloy subjected to cold rolling, asymmetric rolling and asymmetric cryorolling, Materials Science and Engineering: A 710 (2018) 10-16. [CrossRef]

- K. Gu, H. Zhang, B. Zhao, J. Wang, Y. Zhou, Z. Li, Effect of cryogenic treatment and aging treatment on the tensile properties and microstructure of Ti–6Al–4V alloy, Materials Science and Engineering: A 584 (2013) 170-176. [CrossRef]

- H.L. Yu, C. Lu, A.K. Tieu, H.J. Li, A. Godbole, S.H. Zhang, Special rolling techniques for improvement of mechanical properties of ultrafine-grained metal sheets: a review, Advanced Engineering Materials 18(5) (2016) 754-769. [CrossRef]

- H.-H. Kang, S.-C. Han, M.-K. Ji, J.-R. Lee, T.-S. Jun, Achieving synergistic improvement of wear and mechanical properties in Ti–6Al–4V alloy by multiple cryogenic treatment, Journal of Materials Research and Technology 29 (2024) 5118-5125. [CrossRef]

- K.X. Gu, Z.Q. Li, J.J. Wang, Y. Zhou, H. Zhang, B. Zhao, W. Ji, The effect of cryogenic treatment on the microstructure and properties of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy, Materials science forum, Trans Tech Publ, 2013, pp. 899-903. [CrossRef]

- V. Gaur, R. Gupta, V.A. Kumar, Electron Beam Welding and Gas Tungsten Arc Welding Studies on Commercially Pure Titanium Sheets, International Conference on Advances in Materials Processing: Challenges and Opportunities, Springer, 2022, pp. 89-94.

- R. Ramdan, I. Jauhari, S. Izman, M.A. Kadir, B. Prawara, E. Hamzah, H. Nur, K. Gu, Z. Li, J. Wang, Shear mechanisms during cryogenic treatment of Ti6Al4V, 12th International Conference On QiR (Quality in Research), 2011, pp. 1390-1396.

- X. Zheng, W. Xie, L. Zeng, H. Wei, X. Zhang, H. Wang, Achieving high strength and ductility in a heterogeneous-grain-structured CrCoNi alloy processed by cryorolling and subsequent short-annealing, Materials Science and Engineering: A 821 (2021) 141610. [CrossRef]

- X. Song, J. Luo, J. Zhang, L. Zhuang, H. Cui, Y. Qiao, Twinning behavior of commercial-purity titanium subjected to cryorolling, Jom 71(11) (2019) 4071-4078. [CrossRef]

- W. He, X. Chen, N. Liu, B. Luan, G. Yuan, Q. Liu, Cryo-rolling enhanced inhomogeneous deformation and recrystallization grain growth of a zirconium alloy, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 699 (2017) 160-169. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xue, M.A. Meyers, V.F. Nesterenko, Self-organization of shear bands in titanium and Ti–6Al–4V alloy, Acta Materialia 50(3) (2002) 575-596.

- S.V. Zherebtsov, G.S. Dyakonov, A.A. Salem, S.P. Malysheva, G.A. Salishchev, S.L. Semiatin, Evolution of grain and subgrain structure during cold rolling of commercial-purity titanium, Materials Science and Engineering: A 528(9) (2011) 3474-3479. [CrossRef]

- S. Zherebtsov, E. Kudryavtsev, S. Kostjuchenko, S. Malysheva, G. Salishchev, Strength and ductility-related properties of ultrafine grained two-phase titanium alloy produced by warm multiaxial forging, Materials Science and Engineering: A 536 (2012) 190-196. [CrossRef]

- R. Ding, Z. Guo, A. Wilson, Microstructural evolution of a Ti–6Al–4V alloy during thermomechanical processing, Materials Science and Engineering: A 327(2) (2002) 233-245.

- D.B. Trivedi, M.D. Atrey, S.S. Joshi, Microstructural Analysis and Integrity of Drilling Surfaces on Titanium Alloy (Ti–6Al–4V) Using Heat-Sink-Based Cryogenic Cooling, Metallography, Microstructure, and Analysis 12(5) (2023) 814-833. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, S. Zhao, B. Wang, S. Cui, R. Chen, R.Z. Valiev, M.A. Meyers, The effects of ultra-fine-grained structure and cryogenic temperature on adiabatic shear localization in titanium, Acta Materialia 181 (2019) 408-422. [CrossRef]

- D. Ryu, Y. Kim, S. Nahm, L. Kang, Recent developments in plastic deformation behavior of titanium and its alloys during the rolling process: a review, Materials 17(24) (2024) 6060. [CrossRef]

- M. Philippe, C. Esling, B. Hocheid, Role of twinning in texture development and in plastic deformation of hexagonal materials, Texture, Stress, and Microstructure 7(4) (1988) 265-301. [CrossRef]

- A. Salinas-Rodriguez, Grain size effects on the texture evolution of α-Zr, Acta metallurgica et materialia 43(2) (1995) 485-498. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Christian, S. Mahajan, Deformation twinning, Progress in materials science 39(1-2) (1995) 1-157.

- B. Bishoyi, R. Sabat, J. Sahu, S. Sahoo, Effect of temperature on microstructure and texture evolution during uniaxial tension of commercially pure titanium, Materials Science and Engineering: A 703 (2017) 399-412. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, Y. Duan, G. Xu, X. Peng, C. Dai, L. Zhang, Z. Li, EBSD characterization of twinning in cold-rolled CP-Ti, Materials characterization 84 (2013) 41-47. [CrossRef]

- S. Cai, Z. Li, Y. Xia, Evolution equations of deformation twins in metals—Evolution of deformation twins in pure titanium, Physica B: Condensed Matter 403(10-11) (2008) 1660-1665. [CrossRef]

- N. Bozzolo, L. Chan, A.D. Rollett, Misorientations induced by deformation twinning in titanium, Applied Crystallography 43(3) (2010) 596-602. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hu, V. Randle, An electron backscatter diffraction analysis of misorientation distributions in titanium alloys, Scripta materialia 56(12) (2007) 1051-1054. [CrossRef]

- N. Bozzolo, N. Dewobroto, H. Wenk, F. Wagner, Microstructure and microtexture of highly cold-rolled commercially pure titanium, Journal of materials science 42(7) (2007) 2405-2416. [CrossRef]

- Y.B. Chun, S.-H. Yu, S. Semiatin, S.-K. Hwang, Effect of deformation twinning on microstructure and texture evolution during cold rolling of CP-titanium, Materials Science and Engineering: A 398(1-2) (2005) 209-219. [CrossRef]

- S. Zherebtsov, W. Lojkowski, A. Mazur, G. Salishchev, Structure and properties of hydrostatically extruded commercially pure titanium, Materials Science and Engineering: A 527(21-22) (2010) 5596-5603. [CrossRef]

- S.Y. Mironov, M. Myshlyaev, Evolution of dislocation boundaries during cold deformation of microcrystalline titanium, Physics of the Solid State 49(5) (2007) 858-864. [CrossRef]

- M. Eddahbi, J. Del Valle, M.T. Pérez-Prado, O.A. Ruano, Comparison of the microstructure and thermal stability of an AZ31 alloy processed by ECAP and large strain hot rolling, Materials Science and Engineering: A 410 (2005) 308-311. [CrossRef]

- N. Stanford, U. Carlson, M. Barnett, Deformation twinning and the Hall–Petch relation in commercial purity Ti, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 39(4) (2008) 934-944. [CrossRef]

- A. Ostapovets, P. Šedá, A. Jäger, P. Lejček, Characteristics of coincident site lattice grain boundaries developed during equal channel angular pressing of magnesium single crystals, Scripta Materialia 64(5) (2011) 470-473. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhong, F. Yin, K. Nagai, Role of deformation twin on texture evolution in cold-rolled commercial-purity Ti, Journal of Materials Research 23(11) (2008) 2954-2966. [CrossRef]

- V. Randle, A methodology for grain boundary plane assessment by single-section trace analysis, Scripta materialia 44(12) (2001) 2789-2794. [CrossRef]

- E. Salahi, A. Rajabi, Fabrication and characterisation of copper–alumina nanocomposites prepared by high-energy fast milling, Materials Science and Technology 32(12) (2016) 1212-1217. [CrossRef]

- N.S. De Vincentis, A. Kliauga, M. Ferrante, M. Avalos, H.-G. Brokmeier, R.E. Bolmaro, Evaluation of microstructure anisotropy on room and medium temperature ECAP deformed F138 steel, Materials Characterization 107 (2015) 98-111. [CrossRef]

- G. Williamson, W. Hall, X-ray line broadening from filed aluminium and wolfram, Acta metallurgica 1(1) (1953) 22-31.

- D.H. Manh, T.T. Ngoc Nha, L.T. Hong Phong, P.H. Nam, T.D. Thanh, P.T. Phong, Determination of the crystalline size of hexagonal La1−xSrxMnO3 (x = 0.3) nanoparticles from X-ray diffraction – a comparative study, RSC Advances 13(36) (2023) 25007-25017.

- Z. Li, H. Gu, K. Luo, C. Kong, H. Yu, Achieving High Strength and Tensile Ductility in Pure Nickel by Cryorolling with Subsequent Low-Temperature Short-Time Annealing, Engineering 33 (2024) 190-203. [CrossRef]

- P. Susila, D. Sturm, M. Heilmaier, B. Murty, V. Subramanya Sarma, Microstructural studies on nanocrystalline oxide dispersion strengthened austenitic (Fe–18Cr–8Ni–2W–0.25 Y 2 O 3) alloy synthesized by high energy ball milling and vacuum hot pressing, Journal of Materials Science 45 (2010) 4858-4865.

- A. Muiruri, M. Maringa, W. du Preez, Evaluation of Dislocation Densities in Various Microstructures of Additively Manufactured Ti6Al4V (Eli) by the Method of X-ray Diffraction, Materials 13(23) (2020) 5355. [CrossRef]

- Z.-Y. Hu, X.-W. Cheng, Z.-H. Zhang, H. Wang, S.-L. Li, G.F. Korznikova, D.V. Gunderov, F.-C. Wang, The influence of defect structures on the mechanical properties of Ti-6Al-4V alloys deformed by high-pressure torsion at ambient temperature, Materials Science and Engineering: A 684 (2017) 1-13. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Meyers, K.K. Chawla, Mechanical behavior of materials, Cambridge university press2008.

- F. Yu, Y. Zhang, C. Kong, H. Yu, Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti–6Al–4V alloy sheets via room-temperature rolling and cryorolling, Materials Science and Engineering: A 834 (2022) 142600. [CrossRef]

- Z. Du, Q. He, R. Chen, F. Liu, J. Zhang, F. Yang, X. Zhao, X. Cui, J. Cheng, Rolling reduction-dependent deformation mechanisms and tensile properties in a β titanium alloy, Journal of Materials Science & Technology 104 (2022) 183-193. [CrossRef]

- T. Xu, S. Wang, X. Li, M. Wu, W. Wang, N. Mitsuzaki, Z. Chen, Effects of strain rate on the formation and the tensile behaviors of multimodal grain structure titanium, Materials Science and Engineering: A 770 (2020) 138574. [CrossRef]

- T. Shanmugasundaram, B. Murty, V.S. Sarma, Development of ultrafine grained high strength Al–Cu alloy by cryorolling, Scripta Materialia 54(12) (2006) 2013-2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Zherebtsov, G. Dyakonov, A. Salem, V. Sokolenko, G. Salishchev, S. Semiatin, Formation of nanostructures in commercial-purity titanium via cryorolling, Acta materialia 61(4) (2013) 1167-1178. [CrossRef]

- D. Yang, P. Cizek, D. Fabijanic, J. Wang, P. Hodgson, Work hardening in ultrafine-grained titanium: Multilayering and grading, Acta materialia 61(8) (2013) 2840-2852. [CrossRef]

- G.V.S. Kumar, K. Mangipudi, G. Sastry, L.K. Singh, S. Dhanasekaran, K. Sivaprasad, Excellent Combination of Tensile ductility and strength due to nanotwinning and a biamodal structure in cryorolled austenitic stainless steel, Scientific Reports 10(1) (2020) 354. [CrossRef]

- S.V.S.N. Murty, N. Nayan, P. Kumar, P.R. Narayanan, S.C. Sharma, K.M. George, Microstructure–texture–mechanical properties relationship in multi-pass warm rolled Ti–6Al–4V Alloy, Materials Science and Engineering: A 589 (2014) 174-181.

- F. Xu, X. Zhang, H. Ni, Y. Cheng, Y. Zhu, Q. Liu, Effect of twinning on microstructure and texture evolutions of pure Ti during dynamic plastic deformation, Materials Science and Engineering: A 564 (2013) 22-33. [CrossRef]

- F. Yu, Y. Zhang, C. Kong, H. Yu, High strength and toughness of Ti–6Al–4V sheets via cryorolling and short-period annealing, Materials Science and Engineering: A 854 (2022) 143766.

- J.W. Won, J.H. Lee, J.S. Jeong, S.-W. Choi, D.J. Lee, J.K. Hong, Y.-T. Hyun, High strength and ductility of pure titanium via twin-structure control using cryogenic deformation, Scripta Materialia 178 (2020) 94-98. [CrossRef]

- R. Singh, D. Sachan, R. Verma, S. Goel, R. Jayaganthan, A. Kumar, Mechanical behavior of 304 Austenitic stainless steel processed by cryogenic rolling, Materials Today: Proceedings 5(9, Part 1) (2018) 16880-16886.

- S. Bahl, L. Xiong, L.F. Allard, R.A. Michi, J.D. Poplawsky, A.C. Chuang, D. Singh, T.R. Watkins, D. Shin, J.A. Haynes, A. Shyam, Aging behavior and strengthening mechanisms of coarsening resistant metastable θ' precipitates in an Al–Cu alloy, Materials & Design 198 (2021) 109378. [CrossRef]

- M. Hussain, P.N. Rao, D. Singh, R. Jayaganthan, S. Goel, K.K. Saxena, Insight to the evolution of nano precipitates by cryo rolling plus warm rolling and their effect on mechanical properties in Al 6061 alloy, Materials Science and Engineering: A 811 (2021) 141072. [CrossRef]

- G. Lütjering, J. Williams, A. Gysler, Microstructure and mechanical properties of titanium alloys, Microstructure And Properties Of Materials: (Volume 2)2000, pp. 1-77.

Figure 1.

Optical micrography along the rolling direction (RD) of (a) as-received specimen shows equiaxed microstructure containing α grains in the matrix and β at the grain boundaries, and cryo-rolled specimens show grain elongations in (b) 5 % deformation, (c) 10 % deformation, (d) 15 % deformation, (e) 20 % deformation and (f) 30 % deformation.

Figure 1.

Optical micrography along the rolling direction (RD) of (a) as-received specimen shows equiaxed microstructure containing α grains in the matrix and β at the grain boundaries, and cryo-rolled specimens show grain elongations in (b) 5 % deformation, (c) 10 % deformation, (d) 15 % deformation, (e) 20 % deformation and (f) 30 % deformation.

Figure 2.

The graph represents the decreasing trend of grain size of as-received (AR), cryo-rolled and heat-treated (HT) specimens with respect to the increase in deformation percentages.

Figure 2.

The graph represents the decreasing trend of grain size of as-received (AR), cryo-rolled and heat-treated (HT) specimens with respect to the increase in deformation percentages.

Figure 3.

Optical micrography and SEM of cryo-rolled specimens: (a) and (b) 5 % deformation, (c) and (d) 10 % deformation, (e) and (f) 15 % deformation, (g) and (h) 20 % deformation and (i) and (j) 30 % deformation showing formation of sub-grain structure and deformation bands respectively.

Figure 3.

Optical micrography and SEM of cryo-rolled specimens: (a) and (b) 5 % deformation, (c) and (d) 10 % deformation, (e) and (f) 15 % deformation, (g) and (h) 20 % deformation and (i) and (j) 30 % deformation showing formation of sub-grain structure and deformation bands respectively.

Figure 4.

EDS map shows the fragmentation of β grains in cryo-rolled specimens in (a) 10 % deformation, (b) 20 % deformation, and (c) 30 % deformation, along with (d) spectra of elements in cryo-rolled Ti-6Al-4V.

Figure 4.

EDS map shows the fragmentation of β grains in cryo-rolled specimens in (a) 10 % deformation, (b) 20 % deformation, and (c) 30 % deformation, along with (d) spectra of elements in cryo-rolled Ti-6Al-4V.

Figure 5.

Inverse pole figure (IPF) maps, misorientation angle distribution graphs, and bright-field TEM micrographs of cryo-rolled Ti-6Al-4V samples deformed by (a-c) 10 %, (d-f) 20 %, and (g-i) 30 %, respectively. The IPF maps reveal the presence of deformation twins, which become less prominent with increasing deformation. Bright-field TEM micrographs show the densification of dislocation features with the same.

Figure 5.

Inverse pole figure (IPF) maps, misorientation angle distribution graphs, and bright-field TEM micrographs of cryo-rolled Ti-6Al-4V samples deformed by (a-c) 10 %, (d-f) 20 %, and (g-i) 30 %, respectively. The IPF maps reveal the presence of deformation twins, which become less prominent with increasing deformation. Bright-field TEM micrographs show the densification of dislocation features with the same.

Figure 6.

XRD plot of as-received and cryo-rolled specimens represents the α and β phases in Ti-6Al-4V.

Figure 6.

XRD plot of as-received and cryo-rolled specimens represents the α and β phases in Ti-6Al-4V.

Figure 7.

The graph represents the decreasing trend of crystallite size of as-received (AR) and cryo-rolled specimens with respect to the increase in deformation percentages.

Figure 7.

The graph represents the decreasing trend of crystallite size of as-received (AR) and cryo-rolled specimens with respect to the increase in deformation percentages.

Figure 8.

The graph represents the increasing trend of dislocation density of as-received (AR) and cryo-rolled specimens with respect to the increase in deformation percentages.

Figure 8.

The graph represents the increasing trend of dislocation density of as-received (AR) and cryo-rolled specimens with respect to the increase in deformation percentages.

Figure 9.

The graph represents the engineering Stress-Strain graph for as-received (AR) and cryo-rolled specimens at different percentages of deformation from 5% to 37.5% corresponding to an increasing trend of yield strength (YS) and ultimate tensile strength (UTS), while a drop in elongation trend.

Figure 9.

The graph represents the engineering Stress-Strain graph for as-received (AR) and cryo-rolled specimens at different percentages of deformation from 5% to 37.5% corresponding to an increasing trend of yield strength (YS) and ultimate tensile strength (UTS), while a drop in elongation trend.

Figure 10.

The graph represents the increasing trend of hardness of as-received (AR), cryo-rolled and heat-treated (HT) specimens with respect to the increase in deformation percentages.

Figure 10.

The graph represents the increasing trend of hardness of as-received (AR), cryo-rolled and heat-treated (HT) specimens with respect to the increase in deformation percentages.

Figure 11.

Optical micrography and SEM show duplex microstructure containing primary α (α) and secondary α (α') in lathe morphology in cryo-rolled specimens resulting from post-heat treatment (a and b) 15 % deformation and (c and d) 30 % deformation.

Figure 11.

Optical micrography and SEM show duplex microstructure containing primary α (α) and secondary α (α') in lathe morphology in cryo-rolled specimens resulting from post-heat treatment (a and b) 15 % deformation and (c and d) 30 % deformation.

Figure 12.

EDS map of the post-heat-treated specimen shows the absence of phase segregation.

Figure 12.

EDS map of the post-heat-treated specimen shows the absence of phase segregation.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of as-received Ti-6Al-4V plate.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of as-received Ti-6Al-4V plate.

| Elements |

Al

(wt.%) |

V

(wt.%) |

Fe

(wt.%) |

C

(wt.%) |

N

(ppm) |

O

(ppm) |

H

(ppm) |

Ti

(wt.%) |

| Composition |

6.2 |

3.8 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

4 |

50 |

62.7 |

Balance |

Table 2.

Deformation twinning system.

Table 2.

Deformation twinning system.

| Twinning type |

Twinning system |

Rotation axis |

Misorientation angle (ᵒ) |

| Tensile |

> |

> |

44.4 |

| Compressive |

> |

0> |

64.6 |

| Compressive |

> |

0> |

74.5 |

| Tensile |

> |

0> |

86.7 |

Table 3.

Tensile properties of as-received (AR) and cryo-rolled specimens at different percentages of deformation from 5% to 37.5%.

Table 3.

Tensile properties of as-received (AR) and cryo-rolled specimens at different percentages of deformation from 5% to 37.5%.

| Specimen |

AR |

5% |

10% |

15% |

20% |

30% |

YS

(MPa)

|

889.63

±5 |

925.91

±7 |

942.56

±3 |

984.34

±3 |

1007.93

±4 |

1061.66

±6 |

UTS

(MPa)

|

952.65

±2 |

1025.59

±5 |

1045.07

±6 |

1071.09

±3 |

1087.42

±4 |

1169.10

±4 |

Elongation

(%)

|

16.43

±1.2 |

6.55

±0.3 |

7.12

±0.6 |

5.76

±0.4 |

6.39

±0.3 |

6.45

±0.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).